SBA Office of Advocacy: Overview, History, and Current Issues

Changes from January 9, 2020 to March 13, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

SBA Office of Advocacy:

Overview, History, and Current Issues

Contents

- Introduction

- Advocacy's Origins

- Office of Chief Counsel for Advocacy

- An "Independent" Office of Advocacy

- Advocacy's Regulatory Oversight Role Expanded

- Advocacy's Independent Status Enhanced

- Current Organizational Structure and Funding

- Advocacy and Federal Regulations

- The RFA

- Executive Order 13272

- Advocacy's Regulatory Activities

- Producing and Promoting Research on Small Businesses

- Advocacy's Research Activities

- Promoting Small Business Outreach

- Advocacy's Outreach Activities

- Current Congressional Issues

- Arguments for Expanding Advocacy's Regulatory Authority

- Arguments Against Expanding Advocacy's Regulatory Authority

- Concluding Observations

Summary

The Office of Advocacy (Advocacy) is an "independent" office within the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) that advances "the views and concerns of small businesses before Congress, the White House, federal agencies, the federal courts, and state and local policymakers as appropriate." The Chief Counsel for Advocacy (Chief Counsel) directs the office and is appointed by the President from civilian life with the advice and consent of the Senate.

Advocacy is a relatively small office with a relatively large mandate—to represent the interests of small business in the regulatory process, provide Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) compliance training to federal regulatory officials, produce and promote small business economic research to inform policymakers and other stakeholders concerning the impact of federal regulatory burdens on small businesses and the role of small businesses in the economy, and facilitate small business outreach across the federal government.

This report examines Advocacy's origins and the expansion of its responsibilities over time; describes its organizational structure, funding, functions, and current activities; and discusses recent legislative efforts to further enhance its authority. For example, during the 115th Congress, the House passed H.R. 5, the Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017 (Title III, Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act), which would have expanded Advocacy's responsibilities. It would have revised and enhanced requirements for federal agency notification of the Chief Counsel prior to the publication of any proposed rule; expanded the required use of small business advocacy review panels from three federal agencies to all federal agencies, including independent regulatory agencies; empowered the Chief Counsel to issue rules governing federal agency compliance with the RFA; specifically authorized the Chief Counsel to file comments on any notice of proposed rulemaking, not just when the RFA is concerned; and transferred size standard determinations for purposes other than the Small Business Act and the Small Business Investment Act of 1958 from the SBA's Administrator to the Chief Counsel. The House passed similar legislation during the 114th Congress (H.R. 527).

The analysis suggests that Advocacy faces several challenges.

- Advocacy, generally recognized as being an independent office, is housed within the much larger SBA which, given their statutorily overlapping missions as advocates for small businesses, makes it more difficult for stakeholders to recognize Advocacy as the definitive voice for small businesses.

- Chief Counsels tend to have relatively short tenures, creating continuity problems for Advocacy.

- The RFA does not define significant economic impact or substantial number of small entities, two key terms for triggering Advocacy's role under the RFA. The lack of clarity concerning these key terms makes it difficult for Advocacy to objectively determine agency compliance with the RFA and to train federal regulatory officials in how to come into compliance with the act.

- Advocacy often finds itself involved in ideological and partisan disputes concerning the outcome of federal regulatory policies for which it does not have the final say.

- Advocacy's ability to produce and promote economic research on small businesses and to engage in outreach activities, particularly outreach activities not directly related to its RFA role, is constrained by its relatively limited budgetary resources.

Introduction

The Office of Advocacy (Advocacy) is an "independent" office within the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) that is responsible for advancing "the views and concerns of small businesses before Congress, the White House, federal agencies, the federal courts, and state and local policymakers as appropriate."1 The Chief Counsel for Advocacy (Chief Counsel) directs the office and is appointed by the President from civilian life with the advice and consent of the Senate. The Chief Counsel and Advocacy support the development and growth of American small businesses by

- "intervening early in federal agencies' regulatory development processes on proposals that affect small entities and providing Regulatory Flexibility Act compliance training to federal agency policymakers and regulatory development officials;

- producing research to inform policymakers and other stakeholders on the impact of federal regulatory burdens on small businesses, to document the vital role of small businesses in the economy, and to explore and explain the wide variety of issues of concern to the small business community; and

- fostering a two-way communication between federal agencies and the small business community."2

Advocacy has 55 staff members and received an appropriation of $9.120 million for FY2020.3

Advocacy's responsibilities have expanded over time, and legislation has been introduced in recent Congresses to increase its authority still further. For example, during the 115th Congress, the House passed H.R. 5, the Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017 (Title III, Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act), by a vote of 238-183. The bill would have, among other provisions,

- revised and enhanced requirements for federal agency notification of the Chief Counsel prior to the publication of any proposed rule;

- expanded the required use of small business advocacy review panels from three federal agencies to all federal agencies, including independent regulatory agencies;

- empowered the Chief Counsel to issue rules governing federal agency compliance with the RFA;

- specifically authorized the Chief Counsel to file comments on any notice of proposed rulemaking, not just when the RFA is concerned; and

- transferred size standard determinations for purposes other than the Small Business Act and the Small Business Investment Act of 1958 from the SBA's Administrator to the Chief Counsel.4

During the 113th Congress, these provisions were included in H.R. 2542, the Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2013, and were later included in H.R. 2804, the Achieving Less Excess in Regulation and Requiring Transparency Act of 2014 (ALERRT Act of 2014), which the House passed on February 27, 2014, and in H.R. 4, the Jobs for America Act (of 2014), which the House passed on September 18, 2014. During the 114th Congress, these provisions were included in H.R. 527, the Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2015, which was passed by the House on February 5, 2015.

More recently, S. 83, the Advocacy Empowerment Act of 2019, would empower the Chief Counsel to issue rules governing federal agency compliance with the RFA.

In addition, during the 114th Congress, S. 2847, the Prove It Act of 2016, which was reported by the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, would have authorized the Chief Counsel to request the Office of Management and Budget's (OMB's) Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) to review any federal agency certification that a proposed rule, if promulgated, will not have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities and, as a result, is not required to submit a regulatory flexibility analysis of the rule. If it is determined that the proposed rule would, if promulgated, have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities, the federal agency would then be required to perform both an initial and a final regulatory flexibility analysis for the rule. The bill was reintroduced during the 115th Congress (S. 2014, the Prove It Act of 2017).

This report examines Advocacy's origins and the expansion of its responsibilities over time; describes its organizational structure, funding, functions, and current activities; and discusses recent legislative efforts to further enhance its authority.

Advocacy's Origins

The Small Business Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-163, as amended) authorized the SBA and directed the agency to "aid, counsel, assist, and protect, insofar as is possible, the interests of small-business concerns." The SBA provided this advocacy function primarily through its administration of small business loan guaranty programs, contracting assistance programs, and management and training programs. The SBA Administrator serves as the lead advocate for small businesses within the federal government.

Office of Chief Counsel for Advocacy

During the early 1970s, several small business organizations indicated at congressional hearings that they were not wholly satisfied with the SBA's advocacy efforts, especially in achieving regulatory relief for small businesses. Congress responded to these concerns by approving legislation (P.L. 93-386, the Small Business Amendments of 1974) authorizing the SBA Administrator to create an Office of Chief Counsel for Advocacy and to appoint a Chief Counsel for Advocacy. The Chief Counsel was to serve as a focal point for the agency's advocacy efforts.5

P.L. 93-386 provided the Chief Counsel five duties:

- 1. serve as a focal point for the receipt of complaints, criticisms, and suggestions concerning the

policiespolicies and activities of the Administration and any other federal agency that affects small businesses; - 2. counsel small businesses on how to resolve questions and problems concerning the relationship of the small business to the federal government;

- 3. develop proposals for changes in the policies and activities of any agency of the federal government that will better fulfill the purposes of the Small Business Act and communicate such proposals to the appropriate federal agencies;

- 4. represent the views and interests of small businesses before other federal agencies whose policies and activities may affect small businesses; and

- 5. enlist the cooperation and assistance of public and private agencies, businesses, and other organizations in disseminating information about the programs and services provided by the federal government, which are of benefit to small businesses, and information on how small businesses can participate in or make use of such programs and services.6

The SBA created the Office of Chief Counsel for Advocacy in October 1974, and designated each of the SBA's regional, district, and branch office directors as the advocacy director for their area.7 The Office of Chief Counsel was placed under the Office of Advocacy, Planning and Research, which was headed by an Assistant Administrator.8 Anthony Stasio, a long-time, career manager within the SBA, was named the first Chief Counsel. Three deputy advocate positions were subsequently created and staffed: deputy advocate for Advisory Councils, deputy advocate for Government Relations, and deputy advocate for Small Business Organizations. The SBA's Office of Chief Counsel for Advocacy was fully operational as of March 1, 1975.9

An "Independent" Office of Advocacy

As the Office of Advocacy began operations, several small business organizations lobbied Congress to provide the Chief Counsel greater independence from the SBA's Administrator. They argued that the SBA's Administrator reports to the White House and is subject to the OMB Director's influence. In their view, OMB, at that time, was more attuned to promoting the interests of large businesses than it was to promoting the interests of small businesses.10

Congress responded to these concerns by passing P.L. 94-305, to amend the Small Business Act and Small Business Investment Act of 1958. Enacted on June 4, 1976, Title II of the act enhanced the Chief Counsel's authority by requiring the Office of Advocacy to be established as a separate, stand-alone office within the SBA and by requiring the Chief Counsel to be appointed from civilian life by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.11

P.L. 94-305 also

- retained Advocacy's five duties as identified in P.L. 93-386;

- specified that one of Advocacy's primary functions was to examine the role of small business in the American economy and the problems faced by small businesses and to recommend specific measures to address those problems;

- empowered the Chief Counsel, after consultation with and subject to the approval of the SBA Administrator, to employ and fix the compensation of necessary staff, without going through the normal competitive procedures directed by federal law and the Office of Personnel Management;12

- specified that the Chief Counsel could obtain expert advice and other services, and hold hearings;

- directed each federal department, agency, and instrumentality to furnish the Chief Counsel with reports and information deemed by the Chief Counsel as necessary to carry out his or her functions;

- ordered the Chief Counsel to provide Congress, the President, and the SBA with information concerning his or her activities; and

- authorized to be appropriated $1 million for Advocacy, with any appropriated funds remaining available until expended.13

It was at this time that the word independent began to be used to describe the Chief Counsel and the Office of Advocacy. However, Advocacy remained a part of the SBA and subject to the sitting Administration's influence. For example, at that time, Advocacy's budget was provided through the SBA's salaries and expenses account, which was approved by the SBA Administrator; Advocacy's annual staffing allotment was subject to the SBA Administrator's approval; and some senior staff within Advocacy were vetted by the White House personnel office prior to hiring.14

Advocacy's Regulatory Oversight Role Expanded

Advocacy's duties were further expanded following enactment of P.L. 96-354, the Regulatory Flexibility Act of 1980 (RFA, as amended).15 The RFA

establishes in law the principle that government agencies must analyze the effects of their regulatory actions on small entities−small businesses, small nonprofits, and small governments−and consider alternatives that would be effective in achieving their regulatory objectives without unduly burdening these small entities. Advocacy has the responsibility of overseeing and facilitating federal agency compliance.16

The RFA's sponsors argued that federal agencies should be required to examine the impact of regulations on small businesses because federal regulations tend to be "uniform in design, permit little discretion in their implementation, and place a disproportionate burden upon small businesses, small organizations and small governmental bodies."17 As Alfred Dougherty Jr., director of the Federal Trade Commission's Bureau of Competition, testified at a congressional hearing:

First, even if actual regulatory costs are equal between competing large and small firms, small firms have fewer units of output over which to spread such costs and must include in the price of each unit a larger component of regulatory cost. Second, where small firms have smaller actual regulatory costs than large firms (as is generally the case), small firms remain at a competitive disadvantage because they are unable to take advantage of the "economies of scale" of regulatory compliance. Large firms generally already have extensive "in-house" data compilation and reporting systems and specialized staff accountants, lawyers and managers whose primary function is regulatory compliance. Small firms, by comparison, must either hire additional personnel or purchase expensive consulting services in order to acquire the necessary regulatory expertise.18

Economist Milton Kafoglis, a member of the President Jimmy Carter's Council on Wage and Price Stability, testified that

There seem to be clear economies of scale imposed by most regulatory endeavors. Uniform application of regulatory requirements thus seems to increase the size [of the] firm that can effectively compete. The cost curve of the firm is shifted upward … [with] the small firms' cost curve shifting more than that of the dominant firms [thus] the share of the dominant firm will increase while that of small firms will decrease. As a result, industrial concentration will have increased. This … suggests that the "small business" [regulatory] problem goes beyond mere sympathy for the small businessman, but strikes at the heart of the established national policy of maintaining competition and mitigating monopoly.19

As discussed below, the RFA requires federal agencies to assess the impact of their forthcoming regulations on small entities, which the act defines as small businesses, small governmental jurisdictions, and certain small not-for-profit organizations.20 The Chief Counsel is responsible for monitoring and reporting agencies' compliance with the act's provisions. The Chief Counsel also reviews and comments on proposed regulations and may appear as amicus curiae (i.e., friend of the court) in any court action to review a rule.

Advocacy's Independent Status Enhanced

P.L. 111-240, the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010, further enhanced Advocacy's independence by ending the practice of including Advocacy's budget in the SBA's Salaries and Expenses' Executive Direction account. Instead, the President is required to provide a separate statement of the amount of appropriations requested for Advocacy, "which shall be designated in a separate account in the General Fund of the Treasury." The Small Business Jobs Act also requires the SBA Administrator to provide Advocacy with "appropriate and adequate office space at central and field office locations, together with such equipment, operating budget, and communications facilities and services as may be necessary, and shall provide necessary maintenance services for such offices and the equipment and facilities located in such offices."

In recognition of its enhanced independence and separate appropriations account, Advocacy, for the first time, issued its own congressional budget justification document and annual performance report as part of the Obama Administration's FY2013 budget request. That document was presented in a new appendix accompanying the SBA's congressional budget justification document and annual performance report. Advocacy has continued to issue its own budget justification document in each of the Administration's subsequent budget requests.21

Current Organizational Structure and Funding

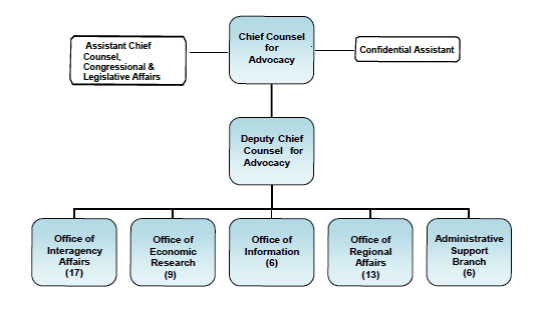

As mentioned previously, Advocacy currently has 55 staff positions (typically with three to six vacancies at any given time): 4, including the Chief Counsel (currently vacant), in the Office of the Chief Counsel; 17 in the Office of Interagency Affairs (regulatory staff); 9 in the Office of Economic Research; 6 in the Office of Information; 13 in the Office of Regional Affairs (regional advocates); and 6 in the Administrative Support Branch. The Office of Advocacy's organizational chart is presented below, with its anticipated staffing level.

|

Figure 1. SBA Office of Advocacy Organizational Chart (anticipated staffing level, FY2020) |

|

|

Source: U.S. Small Business Administration, "SBA Plan for Operating in the Event of a Lapse in Appropriations," effective February 14, 2019, p. 22, at https://www.sba.gov/document/ |

Advocacy received an appropriation of $9.120 million for FY2020. Staff salaries and benefits account for about 95% of Advocacy's budget, with the remainder used for economic research grants and direct expenses, such as subscriptions, travel, training, and office supplies.22

Advocacy and Federal Regulations

Advocacy is responsible for monitoring and reporting on federal agency compliance with the RFA (5 U.S.C. §§601-612) and Executive Order 13272, Proper Consideration of Small Entities in Agency Rulemaking (August 13, 2002). Advocacy also comments on proposed rules and participates in small business advocacy review panels, among other activities.

The RFA

As mentioned previously, the RFA (as amended) requires federal agencies to assess the impact of their forthcoming regulations on small entities, which the act defines as including small businesses, small governmental jurisdictions, and certain small not-for-profit organizations. According to Advocacy, the RFA

does not seek preferential treatment for small entities, require agencies to adopt regulations that impose the least burden on small entities, or mandate exemptions for small entities. Rather, it requires agencies to examine public policy issues using an analytical process that identifies, among other things, barriers to small business competitiveness and seeks a level playing field for small entities, not an unfair advantage.23

Under the RFA, Cabinet departments and independent agencies as well as independent regulatory agencies must prepare a regulatory flexibility analysis at the time certain proposed and final rules are issued.24 The analysis must describe, among other things, (1) the reasons why the regulatory action is being considered; (2) the small entities to which the proposed rule will apply and, where feasible, an estimate of their number; (3) the projected reporting, recordkeeping, and other compliance requirements of the proposed rule; and (4) any significant alternatives to the rule that would accomplish the statutory objectives while minimizing the impact on small entities.25

However, these analytical requirements are not triggered if the head of the issuing agency certifies that the proposed rule would not have a "significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities." The RFA does not define significant economic impact or substantial number of small entities. As a result, federal agencies have substantial discretion regarding when the act's analytical requirements are initiated. In addition, the RFA's analytical requirements do not apply to final rules for which the agency does not publish a proposed rule.26

The RFA also requires federal agencies to

- publish a "regulatory flexibility agenda" each April and October in the Federal Register, listing regulations that the agency expects to propose or promulgate which are likely to have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities;

- provide their regulatory flexibility agenda to the Chief Counsel and to small businesses or their representatives;

- retrospectively review rules that have or will have a significant impact within 10 years of their promulgation to determine whether they should be continued without change or should be amended or rescinded to minimize their impact on small entities; and

- ensure that small entities have an opportunity to participate in the rulemaking process.27

In addition, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) are required to convene a small business advocacy review panel (sometimes referred to as SBREFA panels)28 whenever they are developing a rule that is anticipated to have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities. These panels consist of a representative or representatives from the rulemaking agency, OMB's Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), and the Chief Counsel. Information and advice from small entity representatives are solicited to assist the panel in understanding the ramifications of the proposed rule. The panel must be convened and complete its report, with recommendations, within a 60-day period.29 Finally, the RFA encourages the issuing agency to modify the proposed rule or initial regulatory flexibility analysis as appropriate, based on the information received from the panel.

The RFA also requires the Chief Counsel to monitor and report at least annually on agencies' compliance with the act. The Chief Counsel accomplishes this primarily by reviewing and commenting on proposed regulations and by participating in small business advocacy review panels. In addition, the Chief Counsel may appear as amicus curiae (i.e., friend of the court) in any court action to review a rule.

Executive Order 13272

Executive Order 13272, Proper Consideration of Small Entities in Agency Rulemaking (August 13, 2002), requires federal agencies to make information publicly available concerning how they will comply with the RFA's statutory mandates.30 It also requires federal agencies to send to Advocacy copies of any draft regulations that may have an impact on a substantial number of small entities. Agencies must send these draft regulations to Advocacy at the same time the draft rules are sent to OIRA for review, or at a reasonable time prior to their publication in the Federal Register. Agencies must consider Advocacy's comments on the proposed rule and must address these comments in the final rule published in the Federal Register.31

Executive Order 13272 requires Advocacy to

- notify federal agencies concerning how to comply with the RFA, which is accomplished primarily through Advocacy's periodic publication of A Guide for Government Agencies: How to Comply with the Regulatory Flexibility Act and through Advocacy's compliance training program;

- report annually on federal agency compliance with the executive order, which is accomplished primarily through Advocacy's annual publication of Report on the Regulatory Flexibility Act; and

- train federal regulatory agencies in how to comply with the RFA, which is accomplished through Advocacy's compliance training program.32

Advocacy's Regulatory Activities

Advocacy provided 1722 official public comment letters to 2014 federal agencies on a variety of proposed rules in FY2018FY2019.33 It also hosted 2317 roundtable discussions in 16 states on(12 in Washington, DC, and 5 outside of DC) on various topics, including proposed rules and regulatory topicsissues.34 These roundtable discussions provided stakeholders an opportunity to share their views concerning the impact of proposed rules. Advocacy also provided training on RFA compliance to 132111 federal officials at 6 rule-writing agencies.35

Each year, Advocacy provides an estimate of the regulatory cost savings its activities provide to small businesses in the form "of foregone capital or annual compliance costs that otherwise would have been required in the first year of a rule's implementation."36 These estimates are based primarily on estimates from the federal agencies promulgating the rules, and, in some instances, from industry estimates.

Estimating the costs and benefits of federal regulations is methodologically challenging.37 For example, researchers must determine the baseline for measurement (i.e., what effects would have occurred in the absence of the regulation) and many regulatory cost estimates are based on aggregating the results of regulatory studies conducted years earlier. These studies often use different methods and vary in quality, making conclusions drawn from them problematic. Some observers, including OMB, doubt whether an accurate measure of total regulatory costs and benefits is possible. Moreover, in the case of Advocacy, estimating regulatory cost savings from its activities is even more challenging because it is nearly impossible to determine what changes to these regulations would have been made during the review and comment period if Advocacy did not exist.

Advocacy reported that its intervention in rules that were made final resulted in regulatory cost savings on behalf of small businesses of $255.3773 million in FY2018FY2019.38

Producing and Promoting Research on Small Businesses

Advocacy's Office of Economic Research "assembles and uses data and other information from many different sources to develop data products that are as timely and actionable as possible."39 These products typically relate "to the role that small businesses "play in the nation's economy, including the availability of credit, the effects of regulations and taxation, the role of firms owned by women, minority and veteran entrepreneurs, factors that influence entrepreneurship, innovation and other issues of concern to small businessesinnovation, and factors that encourage or inhibit small business start-up, development and growth."40

In addition to sponsoring and conducting research on small business, Advocacy maintains web pages with links to

- state economic profiles, which are compiled annually by Office of Advocacy staff and provide information concerning small businesses in the state, such as number of small businesses in the state, the number of people employed by those small businesses in the state, and various demographic information concerning the small business owners in the state;41

- firm size economic data, which are compiled by Advocacy staff from the U.S. Bureau of the Census and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and provide information concerning various owner and business characteristics, such as the number of firms, number of establishments, employment, and annual payroll by the employment size of the business and by location and industry;42

- quarterly economic bulletins, which are authored by Advocacy staff to examine trends in small business employment and lending;43

- research projects which have been authored by Office of Advocacy staff, either by choice or by congressional mandate, and by others sponsored by Advocacy;44

- fact sheets, which are authored by Office of Advocacy staff, covering various topics, such as gender differences in financing, the availability of health insurance among small businesses, and credit card financing;45

- issue briefs, which are authored by Advocacy staff, covering various topics, such as veteran business owners and access to capital for women- and minority-owned businesses;46 and

- major sources of data collected by the federal government concerning small business.47

Advocacy also provides funding to the Census Bureau to support the generation of business data by firm size; publishes "The Small Business Advocate," a newsletter summarizing Advocacy's research endeavors, which has more than 36,000 online subscribers; and publishes "The Small Business Economy," an annual report on the status of small businesses and their role in the national economy.48

Advocacy's Research Activities

Advocacy published 20 contract and internal research and data reports in FY2018FY2019.49 These reports covered a variety of issues, including crowdfunding, the regulatory development process, nonemployer businesses, and state rankings by small business economic indicatorssmall business GDP, growth accelerators, nonemployer statistics, and Small Business Profiles for the Congressional Districts. Advocacy also released seven new fact sheets on various small business topics, such as the status of bank credit, as well as spotlights on community bank lending and minority-, women-, and veteran-owned employer firms.50

In addition, Advocacy's economic research staff sponsored sixfive "Small Business Economic Research Forums." These forums provide economists and researchers an opportunity "to discuss a key economic topic" and help "to keep Advocacy's staff up-to-date on the latest data and research from other agencies and researchers."51

Promoting Small Business Outreach

As mentioned previously, Advocacy engages in outreach activities related to its role with the RFA. For example, in FY2016, Advocacy participated in seven small business advocacy review panels in FY2016 (one with OSHA, two with the CFPB, and four with the EPA), one panel in FY2018 (with OHSA), and none in FY2019 (one with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, two with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and four with the Environmental Protection Agency) and one in FY2018 (with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration).52 In each case, Advocacy provided outreach to small business owners interested in sharing their views concerning the agency's proposed rule.

Advocacy also regularly sponsors roundtable discussions, conferences, and symposia to provide small business owners an opportunity to share their views on issues of concerns to them. For example, Advocacy's regional advocates regularly "interact directly with small businesses, small business trade associations, governors and state legislatures to educate them about the benefits of regulatory flexibility and testify at state-level legislation hearings on small business issues when requested to do so."53 Regional advocates also "work closely with the ten Regional Fairness Boards in their respective regions to develop information for the SBA's National Ombudsman, as provided for by the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act and alert businesses in their respective regions about regulatory proposals that could affect them."54

The Chief Counsel also meets regularly with business organizations and trade associations, and participates in Advocacy roundtable discussions, conferences, and symposia. Advocacy's economists provide economic presentations at academic conferences, trade association meetings, think tank events, and other government-sponsored events.55

Advocacy's Outreach Activities

Advocacy's regional advocates participated in 523852 outreach events in FY2018FY2019.56 Advocacy's economists also made 1822 presentations to academic, media, or other small business policy-related audiences.57

Current Congressional Issues

As has been discussed, Advocacy's responsibilities have expanded over time. During the 115th Congress, the House passed H.R. 5, the Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017 (Title III, Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act), which would have increased Advocacy's authority still further. Specifically, H.R. 5 would have

- revised and enhanced requirements for federal agency notification of the Chief Counsel prior to the publication of any proposed rule;

- expanded the required use of small business advocacy review panels from three federal agencies to all federal agencies, including independent regulatory agencies;

- empowered the Chief Counsel to issue rules governing federal agency compliance with the RFA;

- specifically authorized the Chief Counsel to file comments on any notice of proposed rulemaking, not just when the RFA is concerned; and

- transferred size standard determinations for purposes other than the Small Business Act and the Small Business Investment Act of 1958 from the SBA's Administrator to the Chief Counsel.

In the 116th Congress, the House also passed H.RR. 128, the Small Business Advocacy Improvements Act of 2019, on January 8, 2019, by voice vote. The bill would expand the list of Advocacy's primary functions and duties by specifying that Advocacy shall (1) examine the role of small businesses in the international economy and (2) represent the views and interests of small businesses before foreign governments and international entities to contribute to regulatory and trade initiatives that may affect small businesses.

In addition, S. 83, the Advocacy Empowerment Act of 2019, would, among other provisions, authorize Advocacy to issue, modify, or amend rules governing federal agency compliance with the RFA.58

Arguments for Expanding Advocacy's Regulatory Authority

Advocates of expanding Advocacy's authority and role under the RFA argue that legislation is necessary to "close loopholes [in the RFA] and more effectively reduce the disproportionate burden that over-regulation places on small entities, thereby enhancing job creation and hastening economic recovery."59 They argue that

recent regulatory expansions and the future threat of further excessive federal regulation—such as under the waves of regulation occurring to implement the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act—have created immense regulatory burdens and uncertainty for the economy, chilling job creation, investment and economic growth and suppressing America's economic freedom and standing among the world's economies. These effects are particularly burdensome on small businesses—and since start-up firms are the source of net job creation in the U.S. economy it is only logical that the impact of these effects on small businesses contributes substantially to the economy's inability to create sufficient levels of new jobs.60

Advocates of expanding the Office of Advocacy's authority also note that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that the lack of a uniform definition for the terms significant economic impact, and substantial number of small entities contributes to inconsistent compliance with the RFA across federal agencies. They argue that GAO's findings are further evidence that the RFA needs to be amended.61

Arguments Against Expanding Advocacy's Regulatory Authority

Opponents of expanding Advocacy's authority and role under the RFA argue that the provisions being advocated are part of an "ongoing attack on federal regulation," presented under the guise of "pro-small business rhetoric, which will erect significant barriers to rulemaking that will hinder the promulgation of critical public health and safety protections."62 They argue that these provisions are

(1) based on the false premise that regulatory costs stifle economic growth and job creation; (2) threatens public health and safety by severely undermining federal agency rulemaking; (3) imposes additional duties on agencies while failing to provide for any additional resources to meet such burdens, and (4) allows more opportunities for industry to delay or defeat proposed rulemakings.63

Opponents also argue that these provisions

do nothing to alleviate the purported burden on small entities of complying with federal regulations. In fact, it includes no provision that offers assistance to small entities, whether through subsidies, government guaranteed loans, preferential tax treatment for small firms, or fully funded compliance assistance offices. Instead, the bill merely aggrandizes the power of the SBA's Office of Advocacy and of the professional lobbying class in Washington.64

Concluding Observations

The SBA's Office of Advocacy is a relatively small office with a relatively large mandate—to represent the interests of small business in the regulatory process, produce and promote small business economic research, and facilitate small business outreach across the federal government. It faces several challenges.

First, Advocacy is generally recognized as being an independent office, but it is housed within the SBA and remains subject to its influence through (1) its proximity to the agency and its organizational culture; (2) the budgetary process, which provides the SBA Administrator a role, albeit recently reduced, in determining Advocacy's budget; and (3) the sheer size of the SBA (more than 5,0003,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees and an annual budget of nearly $1 billion) relative to Advocacy which, given their statutorily overlapping missions as advocates for small businesses, makes it more difficult than would otherwise be the case for stakeholders to recognize Advocacy as the definitive voice for small businesses.

Second, Chief Counsels tend to have relatively short tenures (three years, eight years, one year, seven years, six years, four years, and one year). When they leave office, there have often been delays in naming a successor, creating continuity problems for Advocacy. For example, the position was filled on an interim basis by Claudia Rodgers, a long-time Advocacy senior staff member, from January 2015 (following Winslow Sargeant's departure) until Darryl L. DePriest's Senate confirmation on December 10, 2015. DePriest left office in January 2017. Major L. Clark, III, previously Assistant Chief Counsel for Procurement Policy for Advocacy, is currently filling the Chief Counsel's position on an interim basis.65 Chief Counsels leave office for various reasons, such as a change in Administration or for more lucrative positions in the private sector.

Third, one of Advocacy's primary functions is to monitor and report on federal agency compliance with the RFA, provide comments on proposed rules, and train federal regulatory officials to assist them in complying with the RFA's provisions. However, as GAO has noted, the RFA does not define significant economic impact or substantial number of small entities, two key terms for triggering Advocacy's role under the RFA. The lack of clarity concerning these key terms makes it difficult for Advocacy to objectively determine agency compliance with the RFA and also makes it more difficult for Advocacy to train federal regulatory officials in how to come into compliance with the act. GAO and others have recommended that Congress clarify the meaning of these terms. However, the RFA's original authors purposely decided not to provide a precise definition for these terms. They argued that the varying missions and constituencies served by federal agencies necessitated the provision of discretion to allow federal agencies to "determine what is significant to their programs and particular constituencies."66

Fourth, Advocacy is subject to criticism from those who believe that it should be more aggressive in preventing federal regulations (i.e., from those who generally oppose federal regulations, especially regulations related to environmental issues and health care reform) and from those who believe that it should be less aggressive in this regard (i.e., from those who generally view federal regulations favorably, especially in addressing environmental and workplace safety issues).67 Thus, Advocacy often finds itself involved in ideological and partisan disputes concerning the outcome of federal regulatory policies for which it does not have the final say.

Finally, Advocacy's relatively limited budget restricts its ability to produce and promote economic research on small businesses and to engage in outreach activities, particularly outreach activities not directly related to its RFA role. It could be argued that Advocacy does not need additional resources for these endeavors because the SBA engages in these same activities. Once again, this reflects the challenges the Office of Advocacy faces as an independent office operating within a much larger federal agency with an overlapping mission.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), "Office of Advocacy: About Us," at https://www.sba.gov/category/advocacy-navigation-structure/about-us-0; and SBA, Office of Advocacy, Fiscal Year |

|

| 2. |

SBA, |

|

| 3. |

SBA, "SBA Plan for Operating in the Event of a Lapse in Appropriations," effective February 14, 2019, p. 22, at https://www.sba.gov/document/report |

|

| 4. |

The size standard provision was in H.R. 585, the Small Business Size Standard Flexibility Act of 2011, which was introduced during the 112th Congress. The other provisions were in H.R. 527, the Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2011, which was introduced during the 112th Congress and passed by the House on December 1, 2011. For additional information concerning H.R. 2542 see H.Rept. 113-288, the Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2013, Part 1. For additional information concerning the SBA's size standards see CRS Report R40860, Small Business Size Standards: A Historical Analysis of Contemporary Issues, by Robert Jay Dilger. |

|

| 5. |

U.S. Congress, House Select Committee on Small Business, Small Business Amendment of 1974, report to accompany H.R. 15578, 93rd Cong., 2nd sess., July 3, 1974, H.Rept. 93-1178 (Washington: GPO, 1974), p. 8. |

|

| 6. |

P.L. 93-386, the Small Business Amendments of 1974. |

|

| 7. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Small Business, Problems Confronting Small Business, hearing on problems confronting small business, 94th Cong., 1st sess., February 24, 1975 (Washington: GPO, 1975), p. 22. |

|

| 8. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Small Business, Oversight of the Small Business Administration: The Office of the Chief Counsel for Advocacy and How It Can Be Strengthened, hearing on the Office of the Chief Counsel for Advocacy, 94th Cong., 2nd sess., March 29, 1976 (Washington: GPO, 1976), pp. 77-78. |

|

| 9. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Small Business, Problems Confronting Small Business, hearing on problems confronting small business, 94th Cong., 1st sess., February 24, 1975 (Washington: GPO, 1975), p. 22; and U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Small Business, Oversight of the Small Business Administration: The Office of the Chief Counsel for Advocacy and How It Can Be Strengthened, hearing on the Office of the Chief Counsel for Advocacy, 94th Cong., 2nd sess., March 29, 1976 (Washington: GPO, 1976), p. 2. |

|

| 10. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Small Business, Oversight of the Small Business Administration: The Office of the Chief Counsel for Advocacy and How It Can Be Strengthened, hearing on the Oversight of the Chief Counsel for Advocacy, 94th Cong., 2nd sess., March 29, 1976, (Washington: GPO, 1976), pp. 83, 94, 104, 109-111. |

|

| 11. |

President Gerald Ford did not nominate a Chief Counsel for Advocacy. Mr. Stasio was named Acting Assistant Administrator for Advocacy and Public Communication and continued to administer the Office of Advocacy until Milton D. Stewart was confirmed as Chief Counsel in 1978. Milton D. Stewart (1978-1981) became the first of seven Chief Counsels, to date, to be nominated by the President (nominated by President Jimmy Carter on March 2, 1978) and confirmed by the Senate (on July 18, 1978). He was succeeded as Chief Counsel by Frank S. Swain (1981-1989, nominated by President Ronald Reagan), Thomas P. Kerester (1992-1993, nominated by President George Bush), Jere Walton Glover (1994-2001, nominated by President William Clinton), Thomas M. Sullivan (2002-2008, nominated by President George W. Bush), Winslow Lorenzo Sargeant (2010 recess appointment, Senate confirmation in 2011, left in January 2015, nominated by President Barack Obama), and Darryl L. DePriest (December 10, 2015-January 2017, nominated by President Barack Obama). |

|

| 12. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Independent Office of Advocacy Act of 2001, 107th Cong., 1st sess., March 21, 2001, S.Rept. 107-5 (Washington: GPO, 2001), p. 2. |

|

| 13. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Select Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Government Regulation and Small Business Advocacy, The Study of Small Business, hearing on The Study of Small Business, 95th Cong., 1st sess., June 29, 1977 (Washington: GPO, 1977), pp. 12-13. |

|

| 14. |

P.L. 94-305; and U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, Independent Office of Advocacy Act of 2001, 107th Cong., 1st sess., March 21, 2001, S.Rept. 107-5 (Washington: GPO, 2001), pp. 2-4. |

|

| 15. |

5 U.S.C. §601 et seq. Also see P.L. 104-121, the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (SBREFA); P.L. 111-203, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010; P.L. 111-240, the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010; and Executive Order 13272. For further information concerning the RFA, see CRS Report RL34355, The Regulatory Flexibility Act: Implementation Issues and Proposed Reforms, coordinated by Maeve P. Carey. |

|

| 16. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, Report on the Regulatory Flexibility Act FY2013, p. 1, at http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/13regflx.pdf. |

|

| 17. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, The Regulatory Flexibility Act, report to accompany S. 299, 96th Cong., 2nd sess., July 30, 1980, S.Rept. 96-878 (Washington: GPO, 1980), p. 3. |

|

| 18. |

| |

| 19. |

|

|

| 20. |

The RFA specifies that …(3) the term small business has the same meaning as the term small business concern under Section 3 of the Small Business Act, unless an agency, after consultation with the Office of Advocacy of the Small Business Administration and after opportunity for public comment, establishes one or more definitions of such term, which are appropriate to the activities of the agency and publishes such definition(s) in the Federal Register; (4) the term small organization means any not-for-profit enterprise, which is independently owned and operated and is not dominant in its field, unless an agency establishes, after opportunity for public comment, one or more definitions of such term, which are appropriate to the activities of the agency and publishes such definition(s) in the Federal Register; (5) the term small governmental jurisdiction means governments of cities, counties, towns, townships, villages, school districts, or special districts, with a population of less than fifty thousand, unless an agency establishes, after opportunity for public comment, one or more definitions of such term which are appropriate to the activities of the agency and which are based on such factors as location in rural or sparsely populated areas or limited revenues due to the population of such jurisdiction, and publishes such definition(s) in the Federal Register; (6) the term small entity shall have the same meaning as the terms small business, small organization and small governmental jurisdiction defined in paragraphs (3), (4), and (5) of this section. See 5 U.S.C. §601 (3)-(6). |

|

| 21. |

The Office of Advocacy's congressional budget documents can be accessed on the SBA's website at |

|

| 22. |

SBA, |

|

| 23. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "A Guide for Government Agencies: How to Comply with the Regulatory Flexibility Act," May 2012, p. 1, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/rfaguide_0512_0.pdf. |

|

| 24. |

The analysis for a proposed rule is referred to as an initial regulatory flexibility analysis (IRFA) and the analysis for a final rule is referred to as a final regulatory flexibility analysis (FRFA). |

|

| 25. |

See CRS Report RL34355, The Regulatory Flexibility Act: Implementation Issues and Proposed Reforms, coordinated by Maeve P. Carey. |

|

| 26. |

|

|

| 27. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Report on the Regulatory Flexibility Act, FY2014," January 2015, pp. 19-21, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/FY2014%20RFA%20Report.pdf. |

|

| 28. |

Small business advocacy review panels were created by P.L. 104-121, the Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996; Title III, the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (SBREFA). That act requires the Environmental Protection Agency and Occupational Safety and Health Administration to convene small business advocacy review panels. P.L. 111-203, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, added the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. |

|

| 29. |

The agency proposing the rule normally fixes the convening date after consulting with Advocacy and OMB's Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. The three agencies typically work together before convening to discuss regulatory alternatives. See SBA, Office of Advocacy, "A Guide for Government Agencies: How to Comply with the Regulatory Flexibility Act," May 2012, p. 52, at http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/rfaguide_0512_0.pdf. |

|

| 30. |

Executive Order 13272, "Proper Consideration of Small Entities in Agency Rulemaking," 67 Federal Register 53461-53462, August 13, 2002. |

|

| 31. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Report on the Regulatory Flexibility Act, FY2016," January 2017, p. 11, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/2016_RFA_Annual_Report.pdf (hereinafter cited as SBA, "Regulatory Flexibility Act Report, FY2016"). |

|

| 32. |

|

|

| 33. |

SBA, | |

| 34. |

|

|

| 35. |

|

|

| 36. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Report on the Regulatory Flexibility Act, FY2013," February 2014, p. 33, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/13regflx.pdf. |

|

| 37. |

For further information and analysis concerning the methodological challenges in estimating the costs and benefits of federal regulation see out-of-print CRS Report R41763, Analysis of an Estimate of the Total Costs of Federal Regulations, available to congressional clients upon request. |

|

| 38. |

SBA, |

|

| 39. |

SBA, | |

| 40. |

|

|

| 41. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "State Economic Profiles," at https://www.sba.gov/category/advocacy-navigation-structure/research-and-statistics/state-economic-profiles. |

|

| 42. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Firm Size Data," at https://www.sba.gov/advocacy/firm-size-data. |

|

| 43. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Quarterly Bulletins," at https://www.sba.gov/category/advocacy-navigation-structure/research-and-statistics/quarterly-indicators. |

|

| 44. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Research Reports," at https://advocacy.sba.gov/category/reports/. |

|

| 45. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Small Business Facts," at https://advocacy.sba.gov/?s=small+business+facts. |

|

| 46. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Issue Briefs," at https://advocacy.sba.gov/?s=issue+briefs. |

|

| 47. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Small Business Data Resources: U.S. Federal Government," at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/Small%20Business%20Data%20Resources%202013.pdf. |

|

| 48. |

SBA, |

|

| 49. |

SBA, |

|

| 50. |

| |

| 51. |

|

|

| 52. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Report on the Regulatory Flexibility Act, FY2016," January 2017, p. 17, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/2016_RFA_Annual_Report.pdf; |

|

| 53. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, Fiscal Year 2015 Congressional Budget Justification and Fiscal Year 2013 Annual Performance Report, p. 12, at http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/advocacy_CBJ_fy15.PDF | |

| 54. |

|

|

| 55. |

SBA, Office of Advocacy, Fiscal Year 2019 Congressional Budget Justification and Fiscal Year 2017 Annual Performance Report, p. 4, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/aboutsbaarticle/FY_2019_CBJ_Office_of_Advocacy.pdf. |

|

| 56. |

SBA, |

|

| 57. |

|

|

| 58. |

See U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship and the Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs and Federal Management, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Reauthorization of the SBA Office of Advocacy, joint hearing, 116th Cong., 1st sess., May 22, 2019, S. Hrg. 116-86 (Washington: GPO, 2019), p. 97. |

|

| 59. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2013, report to accompany H.R. 2542, 113th Cong., 1st sess., December 11, 2013, H.Rept. 113-288, Part 1 (Washington: GPO, 2013), p. 2. |

|

| 60. |

|

|

| 61. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2013, report to accompany H.R. 2542, 113th Cong., 1st sess., December 11, 2013, H.Rept. 113-288, Part 1 (Washington: GPO, 2013), p. 3; and U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2015, report to accompany H.R. 527, 114th Cong., 1st sess., February 2, 2015, H.Rept. 114-12, Part 1 (Washington: GPO, 2015), p. 3. See U.S. General Accounting (now Accountability) Office, Regulatory Flexibility Act: Key Terms Still Need to Be Clarified, GAO-01-669T, April 24, 2001, pp. 1-2, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/110/108793.pdf; U.S. General Accounting (now Accountability) Office, Regulatory Flexibility Act: Clarification of Key Terms Still Needed, GAO-02-491T, March 6, 2002, pp. 3-4, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/110/109134.pdf; U.S. General Accounting (now Accountability) Office, Regulatory Reform: Prior Reviews of Federal Regulatory Process Initiatives Revel Opportunities for Improvements, GAO-05-939T, July 27, 2005, pp. 5-7, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/120/112084.pdf; and U.S. General Accounting (now Accountability) Office, Regulatory Flexibility Act: Congress Should Revisit and Clarify Elements of the Act to Improve Its Effectiveness, GAO-06-998T, July 20, 2006, pp. 1, 4-10, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/120/114481.pdf. |

|

| 62. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2013, report to accompany H.R. 2542, 113th Cong., 1st sess., December 11, 2013, H.Rept. 113-288, Part 1 (Washington: GPO, 2013), p. 58. |

|

| 63. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2015, report to accompany H.R. 527, 114th Cong., 1st sess., February 2, 2015, H.Rept. 114-12, Part 1 (Washington: GPO, 2015), p. 57. |

|

| 64. |

|

|

| 65. |

President Trump nominated David C. Tryon to be the next Chief Counsel on September 29, 2017. The Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship held a hearing on his nomination on February 14, 2018. The hearing can be viewed at https://www.sbc.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/hearings?ID=C476277C-BE34-4FA6-B8D8-D445AB2EE120. |

|

| 66. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, The Regulatory Flexibility Act, report to accompany S. 1974, 95th Cong., 2nd sess., October 11, 1978, S.Rept. 95-1322 (Washington: GPO, 1978), p. 30. |

|

| 67. |

See SBA, Office of Advocacy, "Letter to The Honorable Olympia J. Snowe concerning the ability of small businesses to claim the new health care tax credit under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)," April 11, 2011, at https://www.sba.gov/content/response-letter-dated-041111-honorable-olympia-j-snowe-1; U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act of 2013, report to accompany H.R. 2542, 113th Cong., 1st sess., December 11, 2013, H.Rept. 113-288, Part 1 (Washington: GPO, 2013), pp. 49, 58-59; Sidney Shapiro and James Goodwin, "Distorting the Interests of Small Business: How the Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy's Politicization of Small Business Concerns Undermines Public Health and Safety," Center for Progressive Reform, Washington, DC, January 2013, at http://www.progressivereform.org/articles/SBA_Office_of_Advocacy_1302.pdf; and Randy Rabinowitz, Katie Greenhaw, and Katie Weatherford, "Small Businesses, Public Health, and Scientific Integrity: Whose Interests Does the Office of Advocacy at the Small Business Administration Serve?" The Center for Effective Government, Washington, DC, at http://www.foreffectivegov.org/office-of-advocacy-report. |