Bolivia’s October 2020 General Elections

Changes from January 7, 2020 to March 24, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

On November 10, 2019, Bolivia's Evo Morales of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party resigned his presidency and sought asylum in Mexico. He ultimately received refugee status in Argentina. Bolivia's military suggested Morales consider resigning to prevent violence after weeks of protests alleging fraud in the October 20, 2019, election. Three individuals in line to succeed Morales (the vice president and the presidents of the senate and the chamber of deputies) also resigned. Opposition Senator Jeanine Añez, formerly second vice president of the senate, declared herself senate president and then interim president on November 12. Bolivia's constitutional court recognized her succession. Following protests and state violence, the MAS-led Congress unanimously approved an electoral law to annul the October elections and select a new electoral tribunal. On January 3, 2020, the tribunal announced those elections are scheduled for May 3, 2020.

The Trump Administration and Congress have expressed concerns regarding irregularities and manipulation in Bolivia's election and violence following the election and Morales's resignation. They support efforts to ensure the May March 22, 2020, Bolivia's Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) suspended preparations for national elections scheduled for May 3 following Interim President Jeanette Añez's declaration of a two-week national quarantine to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Bolivia remains extremely polarized following annulled October 2019 elections alleged to be marred by fraud and the November resignation of President Evo Morales of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party. Morales's former finance minister Luis Arce had been leading the polls. According to the TSE, the MAS-led Congress may need to enact legislation to select a new election date.

The United States remains concerned about the political volatility in Bolivia. The Trump Administration and Congress have supported efforts to ensure the elections are free and fair.

October Elections Annulled

Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, transformed Bolivia, but observers criticized his effort to remain in office beyond constitutionally mandated term limits (he won elections in 2006, 2009, and 2014). In 2017, Bolivia's Constitutional Tribunal removed limits on reelection established in the 2009 constitution, effectively overruling a 2016 referendum in which voters rejected a constitutional change to allow Morales to serverun for another term.

|

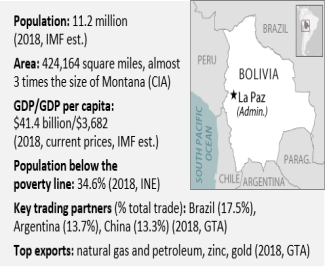

Figure 1. Bolivia at a Glance |

|

|

Sources: CRS Graphics, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE), Global Trade Atlas (GTA). |

In January 2019, Morales began campaigning for a fourth term. Opposition candidates included former President Carlos Mesa (2003-2005), Senator Oscar Ortiz, and evangelical minister Chi Hyun Chung.

Allegations of Allegations of fraud marred Bolivia's October 2019 election. Morales needed to win by aelection. The TSE said Morales exceeded the 10-point margin he needed to avoid a runoff over former president Carlos Mesa, but Mesa rejected that result. Some protesters called for a new election; others demanded Morales's resignation.

On November 10, 2019, the Organization of American States (OAS) issued preliminary findings suggestingto avoid a runoff. The country's electoral agency said Morales won narrowly over Mesa, but Mesa rejected that result. Observers from the Organization of American States (OAS) described irregularities in the process. Mesa called for protesters to demand a new election, while Luis Camacho, head of a civic committee from Santa Cruz, led national protests for Morales's resignation. On October 30, the Morales government agreed to have the OAS audit the election results and to convene a runoff election if recommended. Nevertheless, protests continued.

On November 10, 2019, the OAS issued preliminary findings suggesting serious manipulation of results and found enough irregularities to merit a new election. Morales agreed to hold new elections, but the opposition rejected his offer. Morales resigned after police refused to stop protesters, ministers resigned, and civic organizations, unions, and the military urged him to step down. The aforementioned November 23, 2019, electoral law annulled the October 20 presidential (and legislative) elections and reimposed term limits. The final OAS election audit report found "serious irregularities" and "intentional manipulation" that made the results impossible to validate.

Interim Government and 2020 Elections

According to Bolivia's constitution, the interim government has a mandate to convene new elections. Some observers have criticized Interim President Añez, formerly a little-known opposition senator, for exceeding that mandate. Añez's past anti-indigenous political rhetoric and conservative cabinet, with only one indigenous member,He sought asylum in Mexico and then Argentina. On November 23, 2019, the Congress unanimously passed an electoral law to annul the October elections and select a new electoral tribunal. In December 2019, the final OAS audit report of the October election found "intentional manipulation" of the results.

Interim Government

Interim President Añez, formerly a little-known opposition senator from Beni, became president following the resignation of three MAS officials ahead of her in the line of succession. Añez's past anti-indigenous rhetoric and conservative cabinet raised concerns among some of Bolivia's indigenous population, which became empowered under Morales. Añez also reversed several MAS foreign policy stances. She expelled Cuban officials, recognized Interim Venezuelan President Juan Guaidó, and got into a diplomatic row with Spain and Mexico regarding their diplomatic protection of former MAS officials.

The MAS-led Congress initially refused to accept Añez's government, and many MAS supporters protested. Añez issued a decree giving the military authority to participate in crowd-control efforts and immunity from certain prosecutionsprosecution while doing so, as long as it respected human rights. The Inter-American Commission of Human Rights issued a report documentingdocumented 36 deaths and 400 injuries that occurred from November 8 to November 27,in mid-November 2019, including two massacres involving state forces. The interim government rejected those findings, accusing "subversives" of orchestrating the protests. Protests died down after passage of the electoral law and Añez's November 24 revocation of the military decree, but they could escalate again, as prosecutors have issued an arrest warrant for Morales on charges of terrorism and sedition.

According to Bolivia's constitution, the interim government has a mandate to convene new elections. Some observers have criticized Añez for exceeding that mandate. Among other policy changes, Interim President Añez reversed many MAS foreign policy positions. Añez expelled Cuban officials, recognized Interim Venezuelan President Juan Guaidó, and got into a diplomatic row with Spain and Mexico regarding their diplomatic protection of former MAS officials. Under Añez, prosecutors have issued an arrest warrant for Morales on charges of terrorism and sedition and reportedly have pursued politically motivated cases against former MAS officials. The interim government is now attempting to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak. While Bolivia ranks in the middle for the region in terms of health security preparedness, the government reportedly lacks intensive care beds and ventilators. As of March 23, Bolivia had 27 confirmed cases of the virus. After the Bolivian Congress passed an election law in November 2019, legislators appointed a new electoral tribunal. In January, that tribunal announced the first round election would occur on May 3, with a second-round presidential runoff, if needed, to occur on June 14. Bolivia's Leading Presidential Candidates Luis Arce: economist, former minister of the economy from 2006 to 2019, who was generally praised by the International Monetary Fund Jeanette Añez: former senator and current interim president who abandoned an earlier pledge not to run Luis Camacho: lawyer and Catholic civic leader from the eastern state of Santa Cruz who led nationwide protests urging Morales's resignation Carlos Mesa: former journalist who served as president from 2003 to 2005 who has opposed the MAS, but has more moderate positions than Añez and Camacho Source: Paola Nagovitch, "Explainer: Presidential Candidates in Bolivia's 2020 Special Elections," Americas Society/Council of the Americas, February 6, 2020. Observers praised the November election law as a step toward new elections. A new electoral tribunal has been appointed and announced that the first round election will occur on May 3. A second-round presidential contest would occur, if needed, on June 14. Añez and Morales are prohibited from running. Candidates include Carlos Mesa and Luis Camacho. The MAS candidate will be named soon. Bolivia's interim government has requested significant election-related assistancegovernment rejected those findings.

May 2020 Elections: Candidates and Postponement

U.S. Concerns

The United States remains concerned about the political volatility in Bolivia, but its role in supporting a return to democracy may be limited. Bolivia-U.S. relations were tense following the 2008 ousting of the U.S. ambassador, and bilateral assistance to the country ended in 2013.

U.S. statements have sometimes mirrored those of the OAS General Secretariat and the European Union (the main donor in Bolivia) but also have praised the Añez government, which the U.S. recognizes, for expelling Cuban officials and recognizing Venezuela's Guaidó government. The State Department supported the OAS election observation and audit efforts. The United States and 25 other OAS countries issued a November statement rejecting violence and calling for new elections as soon as possible. A December 9 statement by Secretary of State Pompeo also called for a focus on convening new elections. Regional consensusWithin the Western Hemisphere, consensus on Bolivia has eroded over the Añez government's crackdown on protesters and efforts to punish Morales and his allies. On December 18, 2019, the OAS Permanent Council narrowly approved a resolution rejecting "racist violence" in Bolivia.

The situation in Bolivia has generated some concern in Congress. S.Res. 447, reported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in December 2019agreed to in the Senate in January 2020, supports the prompt convening of new elections.