Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and Select U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Changes from January 6, 2020 to March 29, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and Select U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Contents

- Introduction

- Federal Interagency Activities

- Select Department and Agency Roles and Responsibilities

- Department of Commerce

- Department of Defense (DOD)

- Air Force

- Army

- Navy

- Department of Energy (DOE)

- Office of Cyber Security, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER)

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC)

- National Laboratories

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

- Science and Technology Directorate (S&T)

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

- Department of the Interior (DOI)

- Department of State (DOS)

- Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (OES)

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

- Federal Agency Spending on Space Weather Activities

- Legislation in the 116th Congress

- The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92)

- The Space Weather Research and Forecasting Act (S. 881) and Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow (PROSWIFT) Act (H.R. 5260)

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

- Table 2. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Defense Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

- Table 3. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Energy Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

- Table 4. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Homeland Security Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

- Table 5. Responsibilities of the Secretary of the Interior Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

- Table 6. Responsibilities of the Secretary of State Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

- Table 7. Summary of Requirements in Section 1740 of the 2020 NDAA

Summary

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and

March 29, 2022

Select U.S. Government Roles and

Eva Lipiec

Responsibilities

Analyst in Natural Resources Policy

Space weather refers to conditions on the sun, in the solar wind, and within the extreme reaches

of Earth'’s upper atmosphere. In certain circumstances, space weather may pose hazards to space-

Brian E. Humphreys

borne and ground-based critical infrastructure systems and assets that are vulnerable to

Analyst in Science and

geomagnetically induced current, electromagnetic interference, or radiation exposure. Hazardous

Technology Policy

space weather events are rare, but may affect broad areas of the globe. Effects may include

physical damage to satellites or orbital degradation, accelerated corrosion of gas pipelines, disruption of radio communications, damage to undersea cable systems or interference with data

transmission, permanent damage to large power transformers essential to electric grid operations, and radiation hazards to astronauts in orbit.

In 2010, Congress

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2010 (2010 NASA Authorization Act; P.L. 111-267) directed the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to improve national preparedness for space weather events and to coordinate related federal space weather efforts (P.L. 111-267). OSTP established the Space Weather Operations, Research, and Mitigation (SWORM) Working Group, which released several strategic and implementation plans, including the 2019 National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan. The White House provided further policy guidance through two executive orders (E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865) regarding space weather and electromagnetic pulses (EMPs), respectively.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Weather Service are(NOAA) is the primary civilian agenciesagency responsible for space weather forecasting. forecasting. The National Laboratories (administered by the Department of Energy) national laboratories, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the National Science Foundation (NSF) support forecasting activities with scientific research. Likewise, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) provides data on the earth'Earth’s variable magnetic field to inform understanding of the solar-terrestrial interface. The Department of Homeland Security disseminates warnings, forecasts, and long-term risk assessments to government and industry stakeholders as appropriate. The Department of Energy is responsible for coordinating recovery in case of damage or disruption to the electric grid. The Department of State is responsible for engagement with international partners to mitigate hazards of space weather. The Department of Defense (DOD) supports military operations with its own space weather forecasting capabilities, sharing expertise and data with other federal agencies as appropriate.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that federal agencies participating in the SWORM Working Group "allocated a combined total of nearly $350 million to activities related to space weather"

The 116th Congress enacted legislation that further defines agency missions and interagency relationships regarding space weather. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (FY2020 NDAA; P.L. 116-92) included a series of homeland security-related provisions that parallel the E.O. 13865 framework for critical infrastructure resilience and emergency response. The FY2020 NDAA also repealed a section of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-91), which authorized a “Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse Attacks and Similar Events.” In October 2020, Congress enacted the Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow Act (PROSWIFT Act; P.L. 116-181), which directed multiple federal entities, including OSTP, NOAA, NASA, NSF, USGS, and parts of DOD, to improve space weather research, monitoring, forecasting, and preparedness in certain ways.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that federal agencies participating in the SWORM Interagency Working Group “allocated a combined total of nearly $350 million to activities related to space weather” in FY2019. NASA allocated the majority ($264 million) of the $350 million total.

Congress enacted S. 1790 in December 2019 as the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (2020 NDAA). The 2020 NDAA amended Sections 320 and 707 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296) to enact a series of homeland security-related provisions that parallel the E.O. 13865 framework for critical infrastructure resilience and emergency response. The 2020 NDAA also repealed Section 1691 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-91), which authorized a "Commission to Assess the Threat to the United States from Electromagnetic Pulse Attacks and Similar Events." Other provisions in the 2020 NDAA require the National Guard to clarify relevant "roles and missions, structure, capabilities, and training," and report to Congress no later than September 30, 2020, on its readiness to respond to electromagnetic pulse events affecting multiple states. Separately, some Members of Congress have introduced the Space Weather Research and Forecasting Act (S. 881), which would define certain federal agency roles and responsibilities, among other provisions.

Introduction

Space weather refers to the dynamic conditions in Earth' The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 (P.L. 117-103) continues support for maintenance and modernization of satellites used for space-weather forecasting. In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA; P.L. 117-58) provides authorizations and appropriations that may support space weather resilience, among other purposes.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 33 link to page 33 link to page 6 link to page 10 link to page 30 link to page 11 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 18 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Federal Interagency Activities and Major Legislation .................................................................... 2

Space Weather Federal Coordination ........................................................................................ 3

Space Weather-Related Legislation Enacted in the 116th and 117th Congresses .............................. 7

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92) ........................... 7 The Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the

Forecasting of Tomorrow (PROSWIFT) Act (P.L. 116-181) ................................................. 9

Legislation in the 117th Congress ............................................................................................ 10

Select Department and Agency Roles and Responsibilities .......................................................... 10

Department of Commerce ........................................................................................................ 11

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) .......................................... 12

Department of Defense (DOD) ............................................................................................... 13

Air Force ........................................................................................................................... 15 Army ................................................................................................................................. 15 Navy .................................................................................................................................. 16

Department of Energy (DOE) ................................................................................................. 16

Office of Cyber Security, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER) ............. 17 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)............................................................. 18 North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) ............................................... 18 National Laboratories........................................................................................................ 18

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) .............................................................................. 19

Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) ..................................................................... 20 Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) .............................................. 21 Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) .......................................................... 21

Department of the Interior (DOI) ............................................................................................ 22 Department of State (DOS) ..................................................................................................... 23 National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) ...................................................... 25 National Science Foundation (NSF) ....................................................................................... 27

Federal Agency Spending on Space Weather Activities ................................................................ 29 Additional Considerations ............................................................................................................. 29

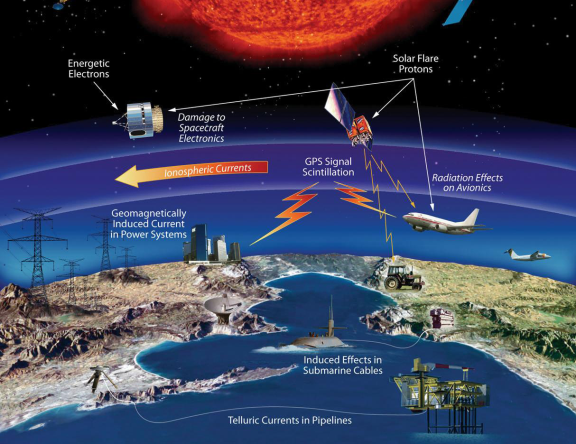

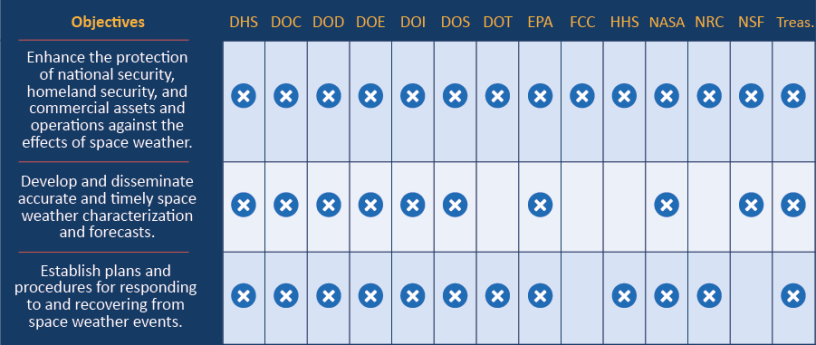

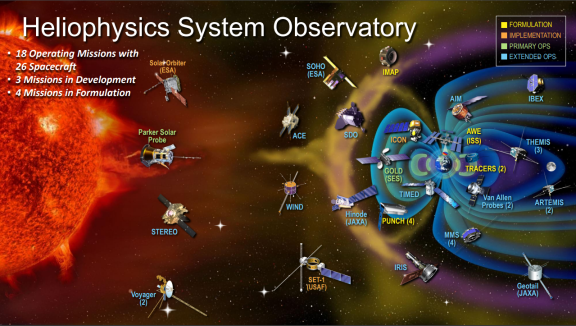

Figures Figure 1. Examples of Potential Effects of Space Weather ............................................................. 2 Figure 2. 2019 National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan Objectives by Agency ............. 6 Figure 3. NASA Heliophysics Satellites as of January 2022......................................................... 26

Tables Table 1. Summary of Space Weather or EMP-Related Requirements in FY2020 NDAA .............. 7 Table 2. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Commerce Under E.O. 13744 and E.O.

13865 ........................................................................................................................................... 11

Table 3. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Defense Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865 ........... 14

Congressional Research Service

link to page 20 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 28 link to page 34 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Table 4. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Energy Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865 ............ 16 Table 5. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Homeland Security Under E.O. 13744 and

E.O. 13865.................................................................................................................................. 19

Table 6. Responsibilities of the Secretary of the Interior Under E.O. 13744 and E.O.

13865 .......................................................................................................................................... 22

Table 7. Responsibilities of the Secretary of State Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865 ................ 24

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 30

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Introduction Space weather refers to the dynamic conditions in Earth’s outer space environment. This includes conditions on the Sunsun, in the solar wind, and in Earth'’s upper atmosphere.11 Space weather phenomena include

- solar flares or periodic intense bursts of radiation from the sun caused by the sudden release of magnetic energy,

- coronal mass ejections composed of clouds of solar plasma and electromagnetic radiation, ejected into space from the sun,

- high-speed solar wind streams emitted from low density regions of the sun, and

- solar energetic particles or

highly-high-energy charged particles formed at the front of solar flares and coronal mass ejections.2

2

Hazardous space weather events are rare, but may cause geomagnetic disturbances (GMDs) that affect broad areas of the globe. Such events may pose hazards to space-borne and ground-based CIcritical infrastructure (CI) systems and assets that are vulnerable to geomagnetically induced current, electromagnetic interference, or radiation exposure (seesee Figure 1).3

Several notable events illustrate space weather hazards, and how their potential impacthow the impact of space weather hazards has broadened over time with technological advances. The 1859 "“Carrington event,"” named for the British solar astronomer who first observed it, caused auroras as far south as Central America and disrupted telegraph communications. In 1972, a GMD knocked out long-distance telephone service in Illinois. In 1989, another GMD caused a nine-hour blackout in Quebec, and melted some power transformers in New Jersey. In 2005, X-rays from a solar storm disrupted GPS signals for a short time.4 In February 2022, at least 40 of 49 broadband internet satellites launched to low earth orbit by a Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) rocket were lost when a geomagnetic storm changed conditions in the upper atmosphere, causing orbital degeneration of the satellites.5

time.4

This report provides an overview of federal government policy developed under the existing legislative framework, and describes the specific roles and responsibilities of select federal departments and agencies responsible for the study and mitigation of space weather hazards.

Federal Interagency Activities

Over the past several decades, the federal government'’s interest in space weather and its effects has grown. Congress has required individual federal agencies to conduct certain space weather-related activities related to agency missions. However, federal interagency work began in earnest with the establishment of the interagency National Space Weather Program (NSWP) in 1995 by the Department of Commerce'’s Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology.5 The program was directed by the NSWP Council that6 The NSWP Council included representatives from interested federal agencies. The NWSPNSWP Council

6 Michael F. Bonadonna, “The National Space Weather Program: Two Decades of Interagency Partnership and Accomplishments,” 2016, at https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016SW001523. Hereinafter Bonadonna 2016.

Congressional Research Service

2

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Council coordinated federal space weather strategy development between 1995 and 2015 in partnership with federal agencies, industry, and the academic community.6

In 2010, Congress directed the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to improve national preparedness for space weather events and to coordinate federal space weather activities of the NSWP Council.7 This marked the beginning of a period during which the White House assumed leadership of federal space weather policy. OSTP's National Science and Technology Council established the Space Weather Operations, Research7

Space Weather Federal Coordination In 2010, the Obama Administration released its “National Space Policy of the United States of America,” which included a goal related to improving space-based Earth and solar observation capabilities to forecast terrestrial and near-Earth space weather and directed the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to work on space weather forecasting, among other goals.8 Under the 2010 NASA Authorization Act, Congress directed the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to improve national preparedness for space weather events and to coordinate federal space weather activities of the NSWP Council.9

OSTP’s National Science and Technology Council established the Space Weather Operations, Research, and Mitigation (SWORM) Working Group in 2014 to lead federal strategy and policy development.10 Thedevelopment.8 The NSWP Council was deactivated the following year, when SWORM published a national strategy for space weather preparedness strategy, titled the "“National Space Weather Strategy" (the 2015 Plan).9

” (2015 Strategy), effectively deactivating the NSWP Council.11 In 2016, President Obama signed Executive Order (E.O.) 13744, "“Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events",” directing federal space weather preparedness activities to be carried out "“in conjunction"” with those activities already identified in the 2015 Plan.10 Strategy.12

The SWORM Interagency Working Group released an updated national space weather strategy in 2019, titled "“The National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan"” (the 2019 Plan).11 13 The same year, President Trump signed E.O. 13865, "“Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,"” directing the federal government to "“foster sustainable, efficient, and cost-effective approaches"approaches” to improve national resilience to the effects of electromagnetic pulses.12

1995–2019 Chronology of Space Weather Federal Coordination

|

1995 |

14

7 The NSWP Council was composed of representatives from the Departments of Defense, Energy, Homeland Security, the Interior, State, and Transportation; National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA); National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); National Science Foundation (NSF); Office of Science and Technology (OSTP); and Office of Management and Budget (OMB). See Bonadonna 2016.

8 Executive Office of the President, National Space Policy of the United States of America, June 28, 2010, pp. 4 and 12. 9 P.L. 111-267; 42 U.S.C. §18388. 10 SWORM is referred to as a working group or task force, depending on the document (see Bonadonna 2016 and National Science and Technology Council, National Space Weather Strategy, Washington, DC, October 2015). The SWORM Working Group is composed of representatives from the Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Federal Communications Commission, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Federal Railroad Administration, NASA, NOAA, NSF, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Navy, U.S. Postal Service, National Security Council, OMB, OSTP, and White House Military Office (SWORM, “About SWORM,” at https://www.sworm.gov/about.htm).

11 National Science and Technology Council, National Space Weather Strategy, Washington, DC, October 2015. 12 E.O. 13744, “Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events,” 81 Federal Register 71573-71577, October 18, 2016.

13 National Science and Technology Council, National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan, Washington, DC, March 2019.

14 E.O. 13865, “Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,” 84 Federal Register 12041-12046, March 29, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 33 link to page 10 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Additionally, it defined GMDs as a subset of EMP—a definition with potential policy implications (see “Additional Considerations”).

In 2020, President Trump released “The National Space Policy,” superseding the 2010 version and reemphasizing other space-related guidance.15 Among other topics, the policy expanded NASA and NOAA’s space weather responsibilities from the 2010 policy, and reiterated OSTP’s role in implementing the 2019 Plan.

1995–2020 Chronology of Space Weather Federal Coordination

1995

NSWP is established under Department of Commerce auspices, and directed by the NSWP Council.

2010

|

|

2010 |

Congress directs OSTP to improve national preparedness for space weather events. |

|

2014 |

2010 President Obama releases the “National Space Policy of the United States of America.” 2014 NSTC establishes the Space Weather Operations, Research, and Mitigation (SWORM) Working Group. |

|

2015 |

2015

The SWORM Interagency Working Group publishes the |

|

The NSWP Council is deactivated.13 |

|

|

2016 |

President Obama signs Executive Order (E.O.) 13744, |

|

2019 |

|

, “The National Space Weather Strategy and Action Plan.”

President Trump signs |

”

2020

President Trump releases “The National Space Policy.”

Congress directs federal agencies to work together in certain ways, including instructing NSTC to establish the Space Weather Interagency Working Group.

Taken together, the 2019 Plan and E.O. 13865 prioritize investment in CI resilience initiatives over scientific research and forecasting, and represent a shift in policy from that of the previous what the Obama Administration set forth in the 2015 PlanStrategy and E.O 13744.1417 The 2019 Plan focuses on three objectives related to protection of assets, space weather forecasting, and planning for space weather events, and identifies the agencies and departments with responsibilities under each objectiveobjective (Figure 2). E.O. 13865 also directs relevant federal agencies to identify regulatory and cost-recovery mechanisms that the government may use to compel private-sector investments in resilience.1518 This approach differs from most other federal infrastructure resilience initiatives, which generally rely upon voluntary industry adoption of resilience measures.16

E.O. 13865 applies both to space weather and manmade electromagnetic hazards (such as a nuclear attack) and refers to both types of hazard as electromagnetic pulse (EMP). This may create ambiguity in cases where a given provision could apply either to manmade or natural electromagnetic hazards. For example, E.O. 13865 directs the Secretary of Homeland Security to "incorporate events that include EMPs as a factor in preparedness scenarios and exercises," without specifying whether a space weather event or nuclear attack scenario should be exercised, or which should be prioritized.17 The fact that E.O. 13865 does not formally supersede E.O. 13744 (which refers solely to space weather) may create further ambiguity in cases where policies of the previous and current Administrations are not in direct alignment, or else reflect differing priorities. Federal agencies typically regard—and refer to—manmade EMP and naturally-occurring GMDs as related, but distinct phenomena.

Select Department and Agency Roles and Responsibilities

CRS-6

link to page 11 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Space Weather-Related Legislation Enacted in the 116th and 117th Congresses The 116th Congress considered and passed two bills related to space weather research, forecasting, preparedness, response, and recovery. Both bills direct multiple federal departments and agencies to support new and existing space weather-related activities. Some of the provisions enacted certain parts of existing executive orders, which may lead to questions on agency implementation when those directives are potentially unclear or overlap (see “Additional Considerations”).

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92) In December 2019, Congress enacted the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (FY2020 NDAA; P.L. 116-92). The FY2020 NDAA amended the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296) and contains a series of homeland security-related requirements that parallel the E.O. 13865 framework for critical infrastructure resilience and emergency response. Table 1 contains this information.21

Table 1. Summary of Space Weather or EMP-Related Requirements in FY2020

NDAA

Department or Agency

Requirement

Deadline

Status

Agencies

Update operational plans to

March 20, 2020

DOE stated that its updated

supporting

protect against and mitigate

“response plans, programs, and

National Essential

effects of EMP/GMD

procedures and operational

Functionsa

plans all account for the effects of EMP and GMD.”b

DHS (relevant

Submit R&D Action Plan to

March 26, 2020

Pending.

sector-specific

Congress

agencies)

DHS, DOD,

Brief Quadrennial Risk

March 26, 2020

Delayed to end of FY2021.

DOE, DOC

Assessment to Congress

DHS

Provide information on

June 19, 2020

Ongoing through existing

EMP/GMD to federal, state, local,

programs and activities.

and private sector stakeholders

21 Agency-provided information to CRS is current as of March 8, 2021. CRS research librarians Rachael Roan and Alexandra Kosmidis searched public sources on March 29, 2022, to update agency-provided information where possible. CRS has not independently verified this information. Terms searched: electromagnetic pulse, EMP, geomagnetic disturbance, GMD, space weather, Quadrennial Risk Assessment, R&D Action Plan, emergency notification systems, technological capabilities, and technological gaps. Sources searched: press releases and annual reports for DHS, DOC, DOD, DOE, DOT, FCC, FEMA, FERC, CISA, and Los Alamos National Laboratory; Congressional Record and Committee Reports on Congress.gov; Inside Defense: https://insidedefense.com/; Google searches across .gov and .mil domains.

Congressional Research Service

7

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Department or Agency

Requirement

Deadline

Status

FEMA (CISA,

Develop EMP/GMD response and June 19, 2020

Ongoing compliance via existing

DOE, FERC)

recovery plans and procedures

plans and procedures.

DHS (S&T, CISA,

Pilot test of engineering

September 22, 2020 Under contract with Los

FEMA, DOD,

approaches to mitigate

Alamos National Laboratory

DOE)

EMP/GMD effects

(LANL) for completion by July 2021.

DOD (DHS,

Pilot test of engineering

September 22, 2020 Interagency pilot project in San

DOE)

approaches to harden defense

Antonio, TX, ongoing.

installations and associated

Additional work pending

infrastructure

completion of LANL pilot test of engineering approaches.

FEMA (CISA,

Conduct EMP/GMD national

December 21, 2020

Completed in December 2020.

DOE, FERC)

exercise

DHS (FEMA,

Report to Congress on effects of

December 21, 2020

Vulnerability assessment of

CISA, DOD,

EMP/GMD on communications

priority infrastructure ongoing

DOC, FCC, DOT) infrastructure with

(scheduled completion July

recommendations for changes to

2021). Report expected January

operational response plans

2022.

FEMA

Brief Congress on state of

December 21, 2020

Complied via briefing to House

emergency notification systems

Energy and Commerce Committee on November 2, 2020.

DHS (DOD,

Report on technological

December 21, 2020

Report draft complete. Agency

DOE)

capabilities and gaps

review ongoing.

DHS (sector-

Review test data on EMP/GMD

December 21, 2020

No information provided.

specific agencies,

effects on critical infrastructure

DOD, DOE)

Source: FY2020 NDAA (P.L. 116-92), Section 1740 and email correspondence on March 8, 2021, with James Platt, Strategic Defense Initiatives, EMP/PNT/GMD Space Weather/Space Risks, National Risk Management Center, CISA, and CRS search of public sources. Note: Parentheses in the first column denote a coordination requirement for the lead department or agency (in bold). CISA = Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (a part of DHS); DHS = Department of Homeland Security; DOC = Department of Commerce; DOD = Department of Defense; DOE = Department of Energy; DOT = Department of Transportation; EMP = electromagnetic pulse; FCC = Federal Communications Commission; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency (a part of DHS); FERC = Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (an independent regulatory commission within DOE); GMD = geomagnetic disturbance; R&D = research and development; S&T = Science and Technology Directorate (a part of DHS). a. National Essential Functions are defined in the bil as “the overarching responsibilities of the Federal

Government to lead and sustain the Nation before, during, and in the aftermath of a catastrophic emergency, such as an EMP or GMD that adversely affects the performance of the Federal Government.”

b. U.S. Department of Energy, Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2020, DOE/CF-0170, November 2020, pp.

11-12, at https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/11/f80/fy-2020-doe-agency-financial-report.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

8

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

The Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow (PROSWIFT) Act (P.L. 116-181) In October 2020, Congress enacted the Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow Act (PROSWIFT Act; P.L. 116-181; 51 U.S.C. §§60601-60608), which directed multiple federal entities, including OSTP, NOAA, NASA, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and parts of the Department of Defense (DOD), to improve space weather forecasts and predictions. The act repealed the space weather-related provision in P.L. 111-267; replacing it with similar language directing OSTP to coordinate federal activities to “improve the ability of the United States to prepare for, avoid, mitigate, respond to, and recover from potentially devastating impacts of space weather.” OSTP is also directed, in collaboration with the interagency working group described below and NOAA-administered advisory group described below, to develop and periodically update a strategy for coordinated observations of space weather by the working group federal agencies.22 The PROSWIFT Act builds on E.O. 13744, using similar language that enacts several of the executive order’s key provisions as well as elements of the 2019 Plan that have provided policy guidance for federal agencies.

In addition to agency-specific requirements, the PROSWIFT Act directs the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) to establish a space weather interagency working group to include representatives from NOAA, NASA, NSF, DOD, the Department of the Interior, and “such other federal agencies as the Director of [OSTP] deems appropriate.”23 The PROSWIFT Act directs the group to “coordinate executive branch actions that improve the understanding and prediction of and preparation for space weather phenomena, and coordinate [f]ederal space weather activities.”24 Other provisions direct the working group to (1) develop, submit to certain congressional committees, and make public a plan to implement the OSTP-coordinated strategy,25 (2) craft formal mechanisms to ensure transition of research to operations and communicate operational needs to research,26 and (3) review and update NSTC’s space weather benchmarks.27 After enactment, NOAA determined that the existing SWORM Interagency Working Group fulfills the act’s requirement to establish an interagency working group.28

The PROSWIFT Act also lists individual and shared requirements for certain agencies. (See each department/agency section below for summary of agency-specific provisions.)

As enacted, the PROSWIFT Act did not include provisions from earlier versions of the legislation that would have directed the National Security Council to “assess the vulnerability of the national security community to space weather events” and to develop national security mechanisms to

22 51 U.S.C. 60602(a)(b), and (e). 23 51 U.S.C. §60601(c). 24 51 U.S.C. §60601(c). In March 2022, NTSC published an interagency framework to support space weather-related research-to-operations and operations-to-research processes in partial fulfilment of the statutory mandate and certain executive branch directives, including E.O. 13744. See NSTC (SWORM), Space Weather Research-to-Operations and Operations-to-Research Framework, Washington, DC, March 2022, https://www.sbir.gov/node/2120223.

25 51 U.S.C. §60602(d). 26 51 U.S.C. §60604(d). 27 51 U.S.C. §60608. 28 Email communication with NOAA Office of Legislative and Intergovernmental Affairs (OLIA), September 14, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

9

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

protect national security assets from space weather threats.29 In a signing statement, President Trump wrote that some provisions of the PROSWIFT Act were “unobjectionable,” but that the act did not address “the resilience of national security assets or critical infrastructure to the effects of space weather” and unduly limited his authority to conduct foreign affairs.30

Legislation in the 117th Congress The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 (P.L. 117-103) continues support for maintenance and modernization of satellites used for space-weather forecasting. In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA; P.L. 117-58) authorizes $50 million for creation of an “advanced energy security program” to support modeling of risks posed by natural and human-made threats and hazards, including electromagnetic pulse and geomagnetic disturbance. Other eligible activities include grid resilience exercises and assessments, research on grid hardening solutions, mitigation and recovery, and “technical assistance to States and other entities for standards and risk analysis.”31 IIJA also appropriates $157.5 million in research and development funding to the Science and Technology Directorate of DHS for a variety of purposes, including “electromagnetic pulse and geomagnetic disturbance resilience capabilities.”32 DHS is required to submit a detailed spend plan for research and development appropriations made under this provision within 90 days of enactment.

Select Department and Agency Roles and Responsibilities This section provides an overview of federal roles and responsibilities for space weather-related research and emergency preparedness. under current legislation and executive branch policy guidance. Legislative or executive branch directives applicable only to human-made EMP threats, such as high-altitude nuclear detonations, are excluded from this overview.

Federal agency roles and responsibilities fall into fourfive major categories: early warning and forecasting; research and development (R&D); basic scientific research; risk assessment and mitigation, including modeling and information sharing; and response and recovery. Some agencies have roles and responsibilities in more than one category. This section only includes only entities that relevant legislation, executive orders, or national or strategies have designated as the federal lead for a specific objective or requirement. This does not includeTherefore, agencies whose role is confined to participation in working groups, harmonizing internal policies with national strategy or directives, contributing refinements to analytical products or models produced by other agencies, or ensuring their own continuity-of-operations in case of a space weather event.

Each sub-section are not included.

Each subsection includes a summary of the department or agency mission and the relevant authorities under which it operates.33 If applicable, the agency-specific provisions of the two executive orders currently in force—E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865—are listed in a table, followed by information about implementing programs and activities. Provisions applicable only to manmade EMP threats, such as high-altitude nuclear detonations, are excluded.

The 2019 Plan is referenced in cases where the executive orders do not provide specific or complete guidance to given federal entities. Departments and agencies are ordered alphabetically for ease of reference.

Department of Commerce18

In 1988, Congress authorized the Secretary of Commerce to " 29 S. 881 introduced in the Senate, March 26, 2019. 30 The White House, “Signing Statement from President Donald J. Trump on S. 881,” release, October 21, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/signing-statement-president-donald-j-trump-s-881/.

31 See P.L. 117-58, Sec. 40125(d)(2). 32 See P.L. 117-58, Division J, Title V. 33 Departments and agencies are ordered alphabetically for ease of reference.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 15 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

In addition, each subsection lists agency-specific requirements of the FY2020 NDAA and the PROSWIFT Act that affect previously existing program authorities for a given department or agency.

Department of Commerce34 In 1988, Congress authorized the Secretary of Commerce to “prepare and issue predictions of electromagnetic wave propagation conditions and warnings of disturbances in such conditions."19 ”35 The Secretary of Commerce delegated those responsibilities to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Secretary of Commerce also directed NOAA to fulfill the department'’s space weather responsibilities in 2016 under E.O. 13744 and in 2019 under E.O. 13865 (Table 1).

E.O. 13744

|

E.O. 13865 |

|

"(i) provide timely and accurate operational observations, analyses, forecasts, and other products for natural EMPs, and (ii) use the capabilities of the Department of Commerce, the private sector, academia, and nongovernmental organizations to continuously improve operational forecasting services and develop standards for commercial EMP technology." |

Source: Executive Order 13744, "Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events,"” 81 Federal Register 71573, October 18, 2016, and Executive Order 13865, "“Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,"” 84 Federal Register 12043, March 29, 2019.

Both executive orders direct the Secretary to improve services and partnercollaborate with relevant stakeholders. The 2016 order refers to the hazard of concern as space weather, while the 2019 order refers to it as natural EMPs.

NOAA'The FY2020 NDAA does not include directives for the Department of Commerce; PROSWIFT Act provisions are described below. The Department of Commerce’s space weather programs and activities are concentrated in NOAA. The National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), another agency within the Department of Commerce, indicated that it has supported “important calibrations that enable systems to operate in space and meet important performance criteria for other agencies.”36

34 For more information, contact Eva Lipiec, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy. 35 P.L. 100-418, Title V; 15 U.S.C. §1532. 36 Email correspondence between CRS and NIST Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs, January 26 and 28, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

11

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

NOAA’s space weather work falls primarily under two line offices: National Weather Service (NWS) and National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS).2037 NWS operates and maintains observing systems to support forecasting of space weather, including the National Solar Observatory Global Oscillation Network Group, a series of ground-based observatories.2138 NWS also operates the Space Weather Prediction Center, which provides real-time monitoring and forecasting of solar events and disturbances and develops models to improve understanding and predict future events.2239 NESDIS maintains NOAA'’s space weather data through the National Centers for Environmental Information.2340 It also develops and manages several satellite programs, which collect solar and space weather-related observations, including the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES) and the Space Weather Follow-on program.41

The PROSWIFT Act requires the NOAA Administrator to establish a space weather advisory group (SWAG) of stakeholders from the academic, commercial space weather, and space weather end user communities.42 NOAA established SWAG in 2021; the group held its first meeting in December 2021.43

The act allows interagency working group members to enter into agreements with one another and requires NOAA to enter into agreements with NASA to develop “space weather spacecraft, instruments, and technologies,” while maintaining existing capabilities in the interim. 44 NOAA also is required to develop a contingency plan for space weather forecasting in the event that existing space-based assets fail prior to replacement and brief Congress on its plan, and “should” develop space-based capabilities beyond the baseline capabilities, with the potential to work with commercial and academic communities.45 NOAA has indicated it has entered into interagency agreements with NASA and DOD, continues to maintain existing back-up capabilities and plan for those of the future, and is exploring partnerships with NASA, NSF, DOD, and the international space agency and research communities to support research and ensure back-up and space-based observational capabilities.46

37 NOAA, “Budget Estimates, Fiscal Year 2021,” at https://www.commerce.gov/sites/default/files/2020-02/fy2021_noaa_congressional_budget_justification.pdf.

38 National Solar Observatory, “Global Oscillation Network Group,” at https://gong.nso.edu/. 39 NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center, “Space Weather Conditions,” at https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/. 40 NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, “Space Weather,” at https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/stp/spaceweather.html.

41 NOAA, “Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites—R Series,” at https://www.goes-r.gov/ and NOAA Office of Projects, Planning and Analysis, “Space Weather Follow-On,” at https://www.nesdis.noaa.gov/OPPA/swfo.php.

42 51 U.S.C. §60601(d). For more information about the PROSWIFT Act, see the section entitled “The Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow (PROSWIFT) Act.”

43 NOAA, “Establishment of the Space Weather Advisory Group and Solicitation of Nominations for Membership,” 86 Federal Register 24390, May 6, 2021, and NOAA, National Weather Service, “Space Weather Advisory Group (SWAG),” at https://www.weather.gov/swag. 44 51 U.S.C. §60601(c)(2), 51 U.S.C. §60603(b)(3), and 51 U.S.C. §60603(c). 45 51 U.S.C. §60603(d), 51 U.S.C. §60603(e), 51 U.S.C. §60603(i), and 51 U.S.C. §60604(b)(3). 46 Email communication with NOAA OLIA, August 6, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 18 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

The PROSWIFT Act also directs NOAA to support review of the integrated strategy and associated research and development goals,47 and to provide for broad-based information sharing with key stakeholders.48 As of August 2021, NOAA continues to work to inform the strategy and expects to enter into an agreement with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) to review the strategy in 2023.49 NOAA indicated that it provides near real-time space weather-related data freely and that it has entered into an agreement with NASEM to establish the Government-University-Commercial Roundtable on Space Weather.50 The act also requires NOAA to establish and administer a pilot program to obtain commercial sector space weather data.51 NOAA solicited commercial space weather data in September 2020, but according to NOAA, none of the responses met NOAA’s mission needs; 52 in November 2021 the agency released another request for information on existing and planned commercial space-based space weather data and related capabilities.53 The FY2020 NDAA does not contain specific provisions addressing the roles and responsibilities of NOAA regarding EMPs/GMDs.

Department of Defense (DOD)54 E.O. 13744 directed DOD to provide space weather forecasts and related products to support military operations of the United States and its partners (Table 3).

47 51 U.S.C. §60602(c). 48 51 U.S.C. §60605(b) and 51 U.S.C. §60606. 49 Email communication with NOAA OLIA, August 6, 2021. 50 Email communication with NOAA OLIA, August 6, 2021. 51 51 U.S.C. §60607. 52 Email communication with NOAA OLIA, August 6, 2021. 53 NOAA, Office of Space Commerce, “NOAA Commercial Space Weather Data RFI,” at https://www.space.commerce.gov/noaa-commercial-space-weather-data-rfi/.

54 For more information, contact Stephen McCall, Analyst in Military Space, Missile Defense, and Defense Innovation.

Congressional Research Service

13

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Table 3. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Defense Under E.O. 13744 and

E.O. 13865

E.O. 13744

E.O. 13865

“(a) The Secretary of Defense shall ensure the timely

“on program.24

Department of Defense (DOD)25

E.O. 13744 directed DOD to provide space weather forecasts and related products to support military operations of the United States and its partners (Table 2).

|

E.O. 13744 |

E.O. 13865 |

|

"(a) The Secretary of Defense shall ensure the timely provision of operational space weather observations, analyses, forecasts, and other products to support the mission of the Department of Defense and coalition partners, including the provision of alerts and warnings for space weather phenomena that may affect weapons systems, military operations, or the defense of the United States." |

(iv) review and update existing EMP-related standards for Department of Defense systems and infrastructure, as appropriate; (v) share technical expertise and data regarding EMPs

and their potential effects with other agencies and with the private sector, as appropriate. |

”

Source: Executive Order 13744, "“Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events,"” 81 Federal Register 71573, October 18, 2016,; and Executive Order 13865, "“Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,"” 84 Federal Register 12042-12043, March 29, 2019.

The FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (FY2018 NDAA; P.L. 115-91) ) codified the language in E.O. 13744. According to the FY2018 NDAA

It is the sense of Congress that the [Secretary of Defense] should ensure the timely provision of operational space weather observations, analyses, forecasts, and other

It is the sense of Congress that the [Secretary of Defense] should ensure the timely provision of operational space weather observations, analyses, forecasts, and other products to support the mission of the DOD including the provision of alerts and warnings for space weather phenomena that may affect weapons systems, military operations, or the defense of the United States.

E.O. 13865 reiterates the E.O. 13744 requirement verbatim, except that it substitutes the phrase "“naturally occurring EMPs"” for "“space weather phenomena."” E.O. 13865 also directs DOD to take further steps related to EMP characterization, warning systems, effects, and protection of DOD systems and infrastructure and the United States from EMPs.

Air Force

The FY2020 NDAA requires DOD to provide quadrennial EMP and GMD risk assessment briefings to Congress, pilot test engineering approaches to harden defense installations and

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 11 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

associated infrastructure from the effects of EMPs and GMDs by September 22, 2020,55 and coordinate with other departments and agencies on related activities (Table 1).

DOD is also a member of the interagency working group created by the PROSWIFT Act. The act directs DOD, among other departments and agencies, to continue to carry out basic research on heliophysics, geospace science, and space weather, as well as support competitive proposals for research, modeling, and monitoring of space weather.56 NASA, NSF, and USGS are also required to transition “space weather research findings, models, and capabilities” to DOD and NOAA, subject to consultation with a designated stakeholder advisory group.57 Also under the PROSWIFT Act, the Secretaries of the Air Force and Navy are requires to maintain and improve ground-based observations of the sun to meet user needs and to continue to provide space weather data through ground-based facilities.58

Air Force

The U.S. Air Force is the lead for all DOD and Intelligence Community (IC) space weather information.2659 Air Force weather personnel provide space environmental information, products, and services required to support DOD operations as required.2760 Air Force space weather operations and capabilities are to support all elements of the DOD and its decisionmakers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the Department of Defense, primarily the Air Force, allocated $24 million to space weather activities in FY2019.28

The 557th61

The 557th Weather Wing, located at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, conducts most of DOD's ’s space weather-related activities. (The 557th Weather Wing remains under the U.S. Air Force rather than the U.S. Space Force). It uses ground-based and space-based observing systems, including the Solar Electro-optical Observing Network (SEON), a network of ground-based observing sites providing 24-hour coverage of solar phenomena; ground-based ionosondes and other sensors providing data in the ionosphere; and space-based observations from the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program.29

Army

62

Army

The Army has two full-time meteorologists to coordinate space weather support within the Army and with other DOD and federal agencies.

Navy

The Naval Research Laboratory's (NRL'

55 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(E)(ii) and P.L. 116-92, Section 1740(f). 56 51 U.S.C. 60604(a). 57 51 U.S.C. 60604(d). 58 51 U.S.C. 60603(f). 59 Department of Defense Joint Publication 3-14, Space Operations, April 10, 2018, at https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_14.pdf.

60 Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research, The Federal Plan for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research—Fiscal Year 2017, FCM-P1-2016, at http://www.ofcm.gov/publications/fedplan/FCM-p1-2017.pdf.

61 Email communication between CRS and Robert Reese, Congressional Budget Office, on October 1, 2019. 62 Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research, The Federal Plan for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research—Fiscal Year 2017, pp. 2-174 to 2-175.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 20 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Navy

The Naval Research Laboratory’s (NRL’s) Remote Sensing and Space Science Divisions and the Naval Center for Space Technology also contribute to the DOD'’s space weather activities.3063 For example, the Wide-field Imager for Solar Probe Plus (WISPR), launched in August 2018, was designed and developed for NASA by NRL'’s Space Design Division. WISPR determines the fine-scale electron density and velocity structure of the solar corona and the source of shocks that produce solar energetic particles.31

64

Department of Energy (DOE)32

65 DOE is responsible for monitoring and assessing the potential disruptions to energy infrastructure from space weather, and for coordinating electricity restoration under authorities granted to it by the White House and Congress.33

E.O. 13744

|

E.O. 13865 |

|

(i) |

”

Source: Executive Order 13744, "“Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events,"” 81 Federal Register 71573, October 18, 2016, and Executive Order 13865, "“Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,"” 84 Federal Register 12043, March 29, 2019.

E.O. 13744 directs DOE to protect and restore the electric power grid in the event of a presidentially declared grid emergency associated with a geomagnetic disturbance. E.O. 13865 assigns additional roles and responsibilities to DOE specific to R&D and coordination with the private sector to better understand electromagnetic threats and hazards, and their possible effects on the electric power grid (Table 3).

4). The FY2020 NDAA directs the Secretary of Energy to provide quadrennial EMP and GMD risk assessment briefings to Congress,67 as well as to coordinate with other departments and agencies on related activities. The Secretary of Energy may also develop or update benchmarks that describe the physical characteristics of EMPs to be shared with CI owners and operators.68 DOE stated that it “made progress on a number of

63 U.S. Navy, “NRL Sensor Provides Critical Space Weather Observations,” at http://www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=49408; and U.S. Navy, “NRP Brings New Hyperspectral Atmospheric and Ocean Science to ISS,” at http://www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=48197. 64 U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, “Headlines and Areas of Research,” at https://www.nrl.navy.mil/ssd/overview/areas-of-research.

65 For more information, contact Richard J. Campbell, Specialist in Energy Policy. 66 The White House, “Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience,” Presidential Policy Directive 21, February 12, 2013. P.L. 114-94 enacted into law the designation of DOE as the sector-specific agency for the energy sector (6 U.S.C. §121 note).

67 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(E)(ii). 68 6 U.S.C. 195f note.

Congressional Research Service

16

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

actions” under E.O. 13865 and the FY2020 NDAA, but did not specify which DOE agencies and offices had led the efforts.69 The PROSWIFT Act does not contain specific energy infrastructure protection requirements or explicitly name DOE as a member of the interagency working group; however, DOE is a part of the existing SWORM Interagency Working Group.70

Relevant programs and activities for energy infrastructure protection and threat mitigation are led by the DOE'’s Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER) (under the Office of Electricity), and, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), and DOE'’s national laboratories.

Office of Cyber Security, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER)

In February 2018, DOE announced the creation of CESER, a new office created from the Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability (OE)..71 CESER has two main divisions: Infrastructure Security and Energy ResponseRestoration (ISER), and Cybersecurity for Energy Delivery Systems. ISER'’s mission is "“to secure U.S. energy infrastructure against all hazards, reduce the impact of disruptive events, and respond to and facilitate recovery from energy disruptions, in collaboration with the private sector and state and local governments."34

The ”72

DOE has produced a number of reports on GMDs and EMPs. In compliance with the National Space Weather Action plan, ISER produced a 2019 report on geomagnetic disturbances and the impact on the electricity grid.3573 This report was designed to provide a better understanding of GMD events in order to protect the U.S. electricity grid.

Prior to the reorganization, DOE'’s OE collaborated with the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), a nonprofit organization that conducts research and develops projects focused on electricity. In 2016, the OE and EPRI together developed the Joint Electromagnetic Pulse Resilience Strategy, and subsequently the DOE Electromagnetic Pulse Resilience Action Plan in January 2017. E.O. 13865 refers to EMPs in two categories: human-made high-altitude (HEMP) and natural EMPs—often referred to as GMDs by government agencies. These DOE-EPRI documents focus specifically on human-made nuclear threats and categorize GMDs separately from EMPs.3674 However, the 2017 plan notes that "“many of the actions proposed herein ... are also relevant to geomagnetic disturbances (GMD), which are similar in system interaction and effects to the E3 portion of the nuclear EMP waveform."37

”75

69 Stated activities included “identifying critical equipment and systems; preparing unclassified waveforms for partner use; working so that DOE’s response plans, programs, and procedures and operational plans all account for the effects of EMP and GMD testing equipment to identify vulnerabilities; and implementing pilot programs” (U.S. Department of Energy, Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2020, DOE/CF-0170, November 2020, pp. 11-12, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/11/f80/fy-2020-doe-agency-financial-report.pdf). The FY2021 agency report does not make reference to these or any other related activities. (U.S. Department of Energy, Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2021, DOE/CF-0180, November 2021, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/fy-2021-doe-agency-financial-report_0.pdf)

70 SWORM, “About SWORM,” at https://www.sworm.gov/about.htm. 71 DOE, “The CESER Blueprint,” at https://www.energy.gov/ceser/ceser-blueprint. 72 U.S. Department of Energy, “Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security and Emergency Response,” at https://www.energy.gov/ceser/ceser-mission.

73 U.S. Department of Energy, Geomagnetic Disturbance Monitoring Approach and Implementation Strategies, January 2019.

74 U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Energy Electromagnetic Pulse Resilience Action Plan, January 2017. Hereinafter U.S. Department of Energy 2017.

75 U.S. Department of Energy 2017, p. 3.

Congressional Research Service

17

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

FERC is an independent government agency officially organized as part of DOE.3876 The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct05; P.L. 109-58) authorized FERC to oversee the reliability of the bulk-power system.3977 FERC'’s jurisdiction is limited to the wholesale power market and the transmission of electricity in interstate commerce.

EPAct05 authorized the creation of an electric reliability organization (ERO) to establish and enforce national reliability standards subject to FERC oversight.4078 FERC certified NERC as the ERO in 2006. The ERO authors the standards for critical infrastructure protection. These standards, which FERC can approve or remand back, are mandatory and enforceable (with fines potentially over $1 million/day for noncompliance).4179 In November 2018, FERC issued a final rule on reliability and transmission system performance standards for GMDs directing NERC to develop "“corrective action plans"” to mitigate GMD vulnerabilities, and to authorize time extensions to implement "“corrective action plans"” on a case-by-case basis.4280 Additionally, the final rule accepts the ERO'’s submitted research plan on GMDs.

North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC)

In 2006 FERC certified NERC as the ERO for the United States. NERC works closely with the public and private electric utilities to develop and enforce FERC-approved standards.4381 Part of NERC'NERC’s role includes reducing risks and vulnerabilities to the bulk-power system. In April 2019, NERC created a task force in response to E.O. 13865 to examine potential vulnerabilities associated with EMPs and to develop possible areas for improvement, focusing on nuclear EMP threats.82

National Laboratories

The 17 DOE threats.44

National Laboratories

DOE oversees 17 national laboratories that advance science and technology advance research and development to support DOE'’s mission. TheFor example, Los Alamos National Laboratory is currently working on ahas funded work on an ongoing study of EMP and GMD physical characteristics and effects on critical infrastructure, to be carried out in four phases.45

.83

76 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, “History of FERC,” at https://www.ferc.gov/students/ferc/history.asp?csrt=4360715013901212967.

77 Defined by NERC as “(A) facilities and control systems necessary for operating an interconnected electric energy transmission network (or any portion thereof); and (B) electric energy from generation facilities needed to maintain transmission system reliability. The term does not include facilities used in the local distribution of electric energy.” NERC, Glossary of Terms Used in NERC Reliability Standards, May 13, 2019, at https://www.nerc.com/files/glossary_of_terms.pdf.

78 North American Electric Reliability Corporation, “History of NERC,” at https://www.nerc.com/news/Documents/HistoryofNERC01JUL19.pdf.

79 For more information on FERC, see CRS Report R45312, Electric Grid Cybersecurity, by Richard J. Campbell. 80 Geomagnetic Disturbance Reliability Standard; Reliability Standard for Transmission System Planned Performance for Geomagnetic Disturbance Events, Order no. 851, 165 FERC ¶ 61,124 (2018).

81 NERC is required to submit an assessment of its performance to FERC three years from the date of certification as the ERO and every five years thereafter. North American Electric Reliability Corporation, “ERO Performance Assessment,” at https://www.nerc.com/gov/Pages/Three-Year-Performance.aspx. 82 NERC, “Electromagnetic Pulses Task Force, Background,” at https://www.nerc.com/pa/Stand/Pages/EMPTaskForce.aspx.

83 See Michael Rivera, Scott Backhaus, and Jesse Woodroffe, et al., EMP/GMD Phase 0 Report, A Review of EMP Hazard Environments, Los Alamos National Laboratory, LA-UR-16-28380, Los Alamos, NM, October 24, 2016, at https://permalink.lanl.gov/object/tr?what=info:lanl-repo/lareport/LA-UR-16-28380. The last update on the research was

Congressional Research Service

18

link to page 23 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

Department of Homeland Security (DHS)84 Department of Homeland Security (DHS)46

Under Presidential Policy Directive 21 (PPD-21), DHS is the lead U.S. agency for critical infrastructure protection and disaster preparedness.4785 E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865 assign several roles and responsibilities to DHS specific to space weather and EMPs (Table 4).

5).

Table 45. Responsibilities of the Secretary of Homeland Security

Under E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865

E.O. 13744

|

E.O. 13865 |

(ii) coordinate response and recovery from the effects of space weather events on critical infrastructure and the broader community" |

(iv) incorporate events that include EMPs as a factor in preparedness scenarios and exercises; (v) in coordination with the heads of relevant SSAs, conduct R&D to better understand and more effectively model the effects of EMPs on national critical functions and associated critical infrastructure—excluding Department of Defense systems and infrastructure—and develop technologies and guidelines to enhance these functions and better protect this infrastructure; and (vi) maintain survivable means to provide necessary emergency information to the public during and after |

EMPs”

Source: Executive Order 13744, "“Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events,"” 81 Federal Register 71574, October 18, 2016, and Executive Order 13865, "“Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,"” 84 Federal Register 12043, March 29, 2019.

Both executive orders assign responsibility to DHS for early warning, response, and recovery functions related to space weather preparedness. However, E.O. 13865 also requires DHS to incorporate EMP scenarios into preparedness exercises, to conduct extensive R&D initiatives to better model EMP hazards and develop mitigation technologies, and to enhance critical infrastructure resilience against EMP hazards in coordination with other relevant federal agencies.

Relevant programs and activities are managed by the Department's Science and Technology Directorate, as well as two DHS operational components: the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency dated September 10, 2018; see “Update on LANL GMD Research Tasks,” at https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1469512-update-lanl-gmd-research-tasks.

84 For more information, contact Brian Humphreys, Analyst in Science and Technology Policy. 85 See PPD-21, “Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience.”

Congressional Research Service

19

Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

The FY2020 NDAA includes several provisions directing the Secretary of Homeland Security to complete activities related to EMPs and GMDs. For example, Congress directed the Secretary, in coordination with other partners and under certain deadlines, to

distribute EMP/GMD information to federal and nonfederal CI owners and

operators and brief Congress on the effectiveness of the distribution;86

conduct R&D to model the effects of EMPs/GMDs on CI, develop technologies

to enhance CI resilience, and submit an action plan to address modeling shortfalls and technology development;87

conduct a quadrennial EMP/GMD risk assessment, brief Congress on the results,

and improve CI resilience using said results;88

periodically report on technological options to improve CI resilience, identify

gaps in available technologies, and develop and implement an integrated cross-sector plan to address the identified gaps;89 and

submit a report to Congress assessing the effects of EMPs/GMDs on

communications CI and recommendations to operational plans to enhance response and recovery efforts after an EMP/GMD.90

The PROSWIFT Act does not contain specific critical infrastructure protection requirements or explicitly name DHS as a member of the interagency working group; however, DHS, and one of its agencies, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), are both a part of the existing SWORM Interagency Working Group.91

The DHS Science and Technology Directorate, along with DHS operational components (the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and FEMA), manage relevant programs and activities. DHS utilizes an all-hazards risk management approach. Therefore, programs are generally not hazard-specific, but rather may be used to support space weather resilience activities as needed.

. Rather, DHS components leverage program capabilities as appropriate to support space weather resilience activities. High-level guidance for these programs and activities is provided by the DHS strategy “Protecting and Preparing the Homeland Against Threats of Electromagnetic Pulse and Geomagnetic Disturbances,” published on October 9, 2018.92

Science and Technology Directorate (S&T)

Science and Technology Directorate (S&T)

S&T conducts R&D projects in partnership with federal agencies and the national laboratories, providing tools and analyses to help electric utilities better predict localized effects of space weather and enhance grid resilience.4893 For example, the Geomagnetic Field Calculator Tool, developed for this purpose by S&T in partnership with NASA, is in the online testing phase.49

86 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(A). 87 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(C). 88 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(E). 89 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(2). 90 P.L. 116-92, Sec. 1740 (g). 91 SWORM, “About SWORM,” at https://www.sworm.gov/about.htm. 92 Department of Homeland Security, Strategy for Protecting and Preparing the Homeland Against Threats of Electromagnetic Pulse and Geomagnetic Disturbances, Washington, DC, October 9, 2018, https://www.dhs.gov/publication/protecting-and-preparing-homeland-against-threats-electromagnetic-pulse-and-geomagnetic.

93 DHS Science and Technology Directorate, Solar Storm Mitigation, fact sheet, 2015, at https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Solar%20Storm%20Mitigation-508_0.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

20

link to page 11 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

developed for this purpose by S&T in partnership with NASA, is in the online testing phase.94 Under the FY2020 NDAA, the Under Secretary for S&T, in coordination with federal and nonfederal partners, is required to develop and implement a pilot test to evaluate available engineering approaches to mitigate EMP/GMD effects on CI, and to brief Congress on its findings.95 The pilot test was placed under contract with Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) and was scheduled for completion by July 2021 (Table 1).

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

CISA administers public-private partnership programs that provide training, technical assistance, and on-site risk assessments to relevant private- sector and federal partners. CISA, the Department of Energy, and interagency partners are producing technical guidance for electric utilities and other industry stakeholders on mitigation of electromagnetic hazards, which may include space weather. CISA provides long-term risk guidance and recommendations on EMP and other hazards to industry stakeholders through the National Risk Management Center.5096 CISA provides real-time space weather advisories to private sector owner-operators of vulnerable infrastructure on an as-needed basis.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)51

97

FEMA develops operations plans and annexes that coordinate use of national resources to address consequences of space weather events. Recent operational documents include the Federal Operating Concept for Impending Space Weather Events (Space Weather Concept of Operations (CONOP)) and the Power Outage Incident Annex and Nuclear/Radiological Incident Annex to the Response and Recovery Federal Interagency Operational Plans. FEMA also periodically incorporates space weather scenarios into all-hazard education, training, and exercise programs. In 2017, FEMA conducted operational and tabletop exercises with federal and state partners. In 2018, FEMA conducted a space weather exercise for senior federal officials.52

98

Under the FY2020 NDAA, Congress directed the Administrator of FEMA, in coordination with other agencies and by certain deadlines, to

coordinate the response to and recovery from the effects of EMPs/GMDs on CI;99 incorporate EMPs/GMDs into preparedness scenarios and exercises;100 conduct a national exercise to test the preparedness and response of the nation to

the effects of EMPs/GMDs;101 and

94 NASA, “Geomagnetic Field Time Series Source,” at https://kauai.ccmc.gsfc.nasa.gov/efieldtool/#about. 95 P.L. 116-92, Sec. 1740(e). 96 CISA, “National Risk Management,” at https://www.cisa.gov/national-risk-management. 97 Research for this section was contributed by CRS Analyst Elizabeth M. Webster, Analyst in Emergency Management and Disaster Recovery.

98 Based on CRS email communication with Kyle Thomas, FEMA Congressional Affairs Specialist. 99 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(B). 100 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(B). 101 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(B).

Congressional Research Service

21

link to page 11 link to page 28 Space Weather: An Overview of Policy and U.S. Government Roles and Responsibilities

maintain a network of systems capable of providing emergency information to

the public before, during, and after an EMP/GMD and brief Congress on such a system.102

These activities are in addition to the Secretary’s required tasks. According to FEMA, it conducted a national exercise in December 2020 and continues work on other FY2020 NDAA requirements as part of ongoing programs (See Table 1).

Department of the Interior (DOI)103 The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is a scientific agency in DOI and aims to provide unbiased scientific information to describe and understand the geological processes of the Earth; minimize loss of life and property from natural disasters; and support the management of water, biological, energy, and mineral resources. 104Department of the Interior (DOI)53

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is DOI's lead scientific agency and "provides research and integrated assessments of natural resources; supports the stewardship of public lands and waters; and delivers natural hazard science to protect public safety, health, and American economic prosperity."54 The Secretary of the Interior has delegated responsibilities from E.O. 13744 and E.O. 13865 to the USGS (Table 5).

E.O. 13744

|

E.O. 13865 |

|

"The Secretary of the Interior shall support the research, development, deployment, and operation of capabilities that enhance understanding of variations of Earth's magnetic field associated with EMPs." |

Source: Executive Order 13744, "Coordinating Efforts to Prepare the Nation for Space Weather Events,"” 81 Federal Register 71573, October 18, 2016, and Executive Order 13865, "“Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses,"” 84 Federal Register 12043, March 29, 2019.

E.O. 13865 requires the USGS to enhance understanding of the variations of the Earth'’s magnetic field associated with all EMPs, manmadehuman-made and space weather-related, whereas E.O. 13744 specifies only those resulting from solar-terrestrial interactions.

The USGS conducts space weather-related activities through the Geomagnetism program under the Natural Hazards Mission Area. The Geomagnetism program collects data about the Earth's ’s dynamic magnetic field at 1114 observatories.105 The USGS provides these data and resulting products to federal agencies, oil drilling services companies, geophysical surveying companies, the electric-power industry, and several international agencies, among others.55106 For example, NOAA'NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center and the Air Force use USGS observatory data in geomagnetic warnings and forecasts. Congress appropriated $1.94.0 million to the Geomagnetism

102 6 U.S.C. 195f(d)(1)(D). 103 For more information, contact Anna E. Normand, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy. 104 For more information on the USGS, see CRS In Focus IF11850, The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): FY2022 Budget Request and Background, by Anna E. Normand.