Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

Changes from January 2, 2020 to September 29, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction and Issues for Congress

- Domestic Politics

- Estonia

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Economic Issues

- Banking Sector Concerns

- Regional Relations with the United States

- Security Partnership and Assistance

- Economic Relations

- Regional Security Concerns and Responses

- Defense Spending and Capabilities

- U.S. European Deterrence Initiative

- NATO Enhanced Forward Presence

- NATO Air Policing Mission

- Potential Hybrid Threats

- Disinformation Campaigns and Ethnic Russians in Baltic States

- Cyberattacks

- Energy Security

- Conclusion

Figures

Summary

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, often referred to as the Baltic states, are close U.S. allies and considered among the most pro-U.S. countries in Europe Lithuania: Background and September 29, 2022

U.S.-Baltic Relations

Derek E. Mix

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, often referred to as the Baltic states, are democracies and close

Specialist in European

U.S. allies. Strong U.S. relations with these three states are rooted in history. The United States

Affairs

never recognized the Soviet Union'’s forcible incorporation of the Baltic states in 1940, and itU.S.

officials applauded the restoration of their independence in 1991. These policies were backed by Congress Congress backed these policies on a bipartisan basis. The United States supported the Baltic states'’ accession to NATOthe North

Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) in 2004.

Especially since Russia's 2014Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014, potential threats posed to the Baltic states by Russia have been a primary driver of increased U.S. and congressional interest in the region. Congressional interest in the Baltic states has focused largely on defense cooperation and security assistance for the purposes of deterring potential Russian aggression and countering hybrid threats, such as disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks. Energy security is another main area of U.S. and congressional interest in the Baltic region.

Regional Security Concerns

U.S., NATO, and Baltic leaders have viewed Russian military activity in the region with concern; such activity includes large-scale exercises, incursions into Baltic states' airspace, and a layered build-up of anti-access/area denial (A2AD) capabilities. Experts have concluded that defense of the Baltic states in a conventional military conflict with Russia likely would be difficult and problematic. The Baltic states fulfill NATO's target of spending 2% of gross domestic product (GDP) on defense, although as countries with relatively small populations, their armed forces remain relatively small and their military capabilities limited. Consequently, the Baltic states' defense planning relies heavily on their NATO membership.

Defense Cooperation and Security Assistance

The United States and the Baltic states cooperate closely on defense and security issues. New bilateral defense agreements signed in spring 2019 focus security cooperation on improving capabilities in areas such as maritime domain awareness, intelligence sharing, surveillance, and cybersecurity. The United States provides significant security assistance to the Baltic states; the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92) increased and extended U.S. assistance for building interoperability and capacity to deter and resist aggression. Under the U.S. European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), launched in 2014, the United States has bolstered its military presence in Central and Eastern Europe. As part of the associated Operation Atlantic Resolve, rotational U.S. forces have conducted various training activities and exercises in the Baltic states.

NATO has also helped to bolster the Baltic states' security. At the 2016 NATO summit, the allies agreed to deploy multinational battalions to each of the Baltic states and Poland. The United Kingdom leads the battalion deployed in Estonia, Canada leads in Latvia, and Germany leads in Lithuania. Rotational deployments of aircraft from NATO member countries have patrolled the Baltic states' airspace since 2004; deployments have increased in size since 2014.

Potential Hybrid Threats

Since 2014, when the EU adopted sanctions targeting Russia due to the Ukraine conflict, tensions between Russia and the Baltic states have grown. These conditions have generated heightened concerns about possible hybrid threats and Russian tactics, such as disinformation campaigns and propaganda, to pressure the Baltic states and promote anti-U.S. or anti-NATO narratives. A large minority of the Estonian and Latvian populations consists of ethnic Russians; Russia frequently accuses Baltic state governments of violating the rights of Russian speakers. Many ethnic Russians in the Baltic states receive their news and information from Russian media sources, potentially making those communities a leading target for disinformation and propaganda. Some observers have expressed concerns that Russia could use the Baltic states' ethnic Russian minorities as a pretext to manufacture a crisis. Cyberattacks are another potential hybrid threat; addressing potential vulnerabilities with regard to cybersecurity is a top priority of the Baltic states.

Energy Security

The Baltic states have taken steps to decrease energy reliance on Russia, including through a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in Lithuania and projects to build pipeline and electricity interconnections with Poland, Finland, and Sweden.

Regional Security Concerns

Russia’s February 2022 renewed invasion of Ukraine has intensified U.S. and NATO concerns about the potential threat of Russian military action against the Baltic states. The Baltic states have supported Ukraine, including by providing military assistance and imposing sanctions against Russia that go beyond those adopted by the EU. Baltic states have been seeking to build up their military capabilities, but their armed forces remain relatively small and their capabilities limited. Consequently, the Baltic states’ defense planning relies heavily on their NATO membership. The Baltic states fulfill NATO’s target for member states to spend at least 2% of gross domestic product on defense.

Defense Cooperation and Security Assistance

The United States and the Baltic states cooperate closely on defense and security issues for the purposes of building capacity to deter and resist potential Russian aggression. In FY2021 and FY2022 combined, Congress appropriated nearly $349 million in U.S. Department of Defense security assistance funding to the Baltic states through the Baltic Security Initiative.

Under the U.S. European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), launched in 2014, the United States has enhanced its military presence in Central and Eastern Europe, with rotational U.S. forces conducting training and exercises in the Baltic states. The United States has stationed additional personnel and capabilities in the Baltic states since February 2022. NATO also has helped to bolster the Baltic states’ security. In 2016, the allies agreed to deploy multinational Enhanced Forward Presence battlegroups to the Baltic states. NATO allies have deployed additional personnel to these battlegroups since February 2022. Baltic leaders have advocated for further enhancements to the U.S. and NATO deployments.

Potential Hybrid Threats

Some observers have expressed concerns that Russia could use the Baltic states’ ethnic Russian minorities as a pretext to manufacture a crisis. Many ethnic Russians in the Baltic states traditionally receive their news from Russian media sources, potentially making those communities a leading target for disinformation and propaganda. The Baltic states suspended many Russia-based television channels following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Cyberattacks are another potential hybrid threat; addressing potential vulnerabilities with regard to cybersecurity is a top priority of the Baltic states.

Energy Security

The Baltic states have taken steps to end energy reliance on Russia, including through a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in Lithuania and new pipeline interconnections with their European neighbors. Lithuania ended imports of Russian gas in April 2022, and Estonia and Latvia plan to do the same by the end of 2022.

Relations with China

A variety of factors have contributed to the Baltic states developing a skeptical view of China over the past several years. In 2021 (Lithuania) and 2022 (Estonia and Latvia), the Baltic states quit the 17+1, a forum China launched to deepen cooperation with countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Tensions between Lithuania and China are especially acute, with China recently launching a de facto trade embargo against Lithuania due to Lithuania’s expanded relations with Taiwan.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 4 link to page 16 link to page 14 link to page 21 Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

Contents

Introduction and Issues for Congress .............................................................................................. 1 Domestic Politics ............................................................................................................................. 2

Estonia ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Latvia ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Lithuania ................................................................................................................................... 4

Economic Issues .............................................................................................................................. 5 Response to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine ...................................................................................... 6 Regional Relations with the United States ...................................................................................... 7

Security Partnership and Assistance .......................................................................................... 8 Economic Relations .................................................................................................................. 9

Regional Security Concerns and Responses .................................................................................... 9

Defense Spending and Capabilities .......................................................................................... 11 U.S. and NATO Military Presence .......................................................................................... 12 Hybrid Threats ........................................................................................................................ 13

Disinformation Campaigns and Ethnic Russians in Baltic States ..................................... 13 Cyberattacks ...................................................................................................................... 14

Energy Security ............................................................................................................................. 15 Relations with China ..................................................................................................................... 16 Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 18

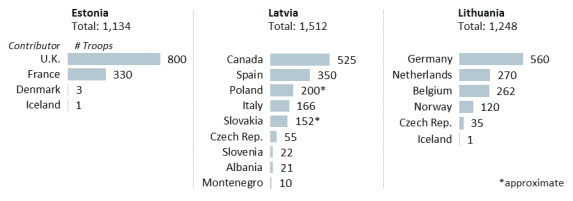

Figures Figure 1. Map of the Baltic Region ................................................................................................. 1 Figure 2. Allied Forces in the Baltic States ................................................................................... 13

Tables Table 1. Baltic States Defense Information .................................................................................... 11

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 18

Congressional Research Service

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

Introduction and Issues for Congress Introduction and Issues for Congress

Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress consider Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, often referred to collectively as the Baltic states, to be valued U.S. allies and among the most pro-U.S. countries in Europe. Strong ties between the United States and the Baltic states have deep historical roots. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia gained their independence in 1918, after the collapse of the Russian Empire. In 1940, they were forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union, but the United States never recognized their annexation.11 The United States strongly supported the restoration of the three countries'countries’ independence in 1991, and it was a leading advocate of their accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)to NATO and the European Union (EU) in 2004.

Figure 1. Map of the Baltic Region

Source: Created by CRS using data from the Department of State and ESRI.

The United States and the Baltic states work closely together in their respective bilateral relationships and within NATO, as well as in the context of U.S.-EU relations. The U.S.-Baltic partnership encompasses diplomatic cooperation in pursuit of shared foreign policy objectives, extensive cooperation on security and defense, and a mutually beneficial economic relationship.2 The United States provides considerable security assistance to the Baltic states, including financing assistance and defense sales, intended to strengthen theirthe military capabilities.

capabilities of the Baltic states.

Since 2014, U.S. focus on the Baltic region has increased, driven by concerns about potential threats posed by Russia. Developments related toSuch concerns have intensified in the context of Russia’s renewed

1 U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, “Press Release Issued by the Department of State on July 23, 1940,” at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1940v01/d412. Also see U.S. Department of State, “Message on the 80th Anniversary of the Welles Declaration,” July 22, 2020, at https://2017-2021.state.gov/message-on-the-80th-anniversary-of-the-welles-declaration/index.html.

Congressional Research Service

1

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

aggression against Ukraine in 2022, leading the United States and NATO to increase their military deployments to the Baltic states.

Developments related to security concerns about Russia and the implications for U.S. policy and NATO likely will have continuing relevance for Congress. Estonia, Latvia, and LithuaniaThe Baltic states are central interlocutors and partners in examiningassessing and responding to these challenges.

As indicated by annual security assistance appropriations, as well as resolutions and bills and the Baltic Security Initiative created in 2021 (see Security Partnership and Assistance below), as well as numerous congressional delegations to the region and congressional resolutions adopted or introduced in recent years, Congress broadly supports the maintenance of close relations and security cooperation with the Baltic states. Increased attention to the Baltic states in the 117th Congress, especially since Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine in 2022, has led to the introduction of bipartisan legislation that would expand and increase the U.S. commitment to providing the Baltic states with security assistance.

The House Baltic Caucus, a bipartisan group of 7071 Members of the House of Representatives, and the Senate Baltic Freedom Caucus, a bipartisan group of 1114 Senators, seek to maintain and strengthen the U.S.-Baltic relationship and engage in issues of mutual interest.3

Domestic Politics

Although outside2

Domestic Politics Given the three countries’ many similarities, observers typically view Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as a group. The countries cooperate extensively with one another and hold comparable views on foreign and security policy (particularly with regard to the threat posed by Russia). Lithuania as a group, citizens of the three countries tend to point out that alongside the three countries' many similarities are notable differences in national history, language, and culture.4 Cooperation and convergence among the Baltic states remains the central trend, but each country has its own unique domestic political dynamics and the viewpoints and priorities of the three countries are not always completely aligned.

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania stand out as the leaders of democracy among post-Soviet states and are the only post-Soviet statesstates formerly part of the Soviet Union that have joined NATO and the EU.5 Since the restoration of their independence nearly 30 years ago, the three countries'’ governments have tended to consist of multiparty coalitions, which have maintained broadly pro-market, pro-U.S./pro-U.S., pro-NATO, and pro-EU orientations.

At the same time, citizens of the three countries tend to point out that alongside the similarities are notable differences in national history, language, and culture. Each country has its own unique domestic political dynamics, and the viewpoints and priorities of the three countries are not always perfectly aligned.3

Estonia Prime Minister Kaja Kallas of the center-right Reform Party leads the government of Estonia. The Reform Party formed a new governing coalition with the conservative Isamaa (Fatherland) party and the center-left Social Democratic Party in July 2022.4 The coalition is Estonia’s fourth government since the country’s 2019 parliamentary election. The Reform Party came in first place in the 2019 election with 28.9% of the vote (34 seats in Estonia’NATO, and pro-EU orientations.

|

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using data from the Department of State and ESRI. |

Estonia

The government of Estonia is led by the center-left Center Party in a coalition with the far-right, anti-immigration Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE) and the conservative Pro Patria (Fatherland) party. Juri Ratas of the Center Party is Estonia's prime minister.

The Center Party came in second in Estonia's March 2019 general election with 23.1% of the vote (26 seats in Estonia's 101-seat unicameral parliament, the Riigikogu);, but it was able to form a government after it unexpectedly reversed its campaign pledge not to work with the far-right EKRE.6 EKRE came in third in the election with 17.8% of the vote, more than doubling its share of the vote from the 2015 election and winning 19 seats (a gain of 12 seats).7 The center-right Reform Party, which led a series of coalition governments from 2005 to 2016, came in first place in the 2019 election, winning 28.9% of the vote (34 seats). However, it was unable to secure enough support from potential coalition partners to form a government.

Estonia at a Glance Population: 1.319 million Ethnicity: 69% Estonian, 25% Russian Languages: Estonian is the official language and first language of 68.5% of the population; Russian is the first language of 30% of the population. Religion: 54% listed as none, 16.7% as unspecified, 16.2% Orthodox, 10% Lutheran Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 2018 (Current Prices): $30.761 billion; per capita GDP approximately $23,330 Currency: euro(€), €1 is approximately $1.10 Political Leaders: President: Kersti Kaljulaid; Prime Minister: Juri Ratas; Foreign Minister: Urmas Reinsalu; Defense Minister: Juri Luik Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), "World Economic Outlook Database," October 2019; Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), World Factbook. |

The Center Party, whose support comes largely from Estonia's Russian-speaking population (about 30% of the population), previously led a coalition government with Pro Patria and the center-left Social Democratic Party from November 2016 until the 2019 election. In late 2016, a changeover in the party's leadership reoriented the Center Party away from a Russian-leaning outlook to a clear pro-Western stance in support of Estonia's membership in NATO and the EU.

During the 2019 campaign, the Center Party advocated for a progressive tax system, higher social spending, a simplified path to citizenship for noncitizen residents, and maintenance of the country's dual Estonian- and Russian-language education system.8 The Reform Party, by contrast, advocated maintenance of a flat tax, tight fiscal policy, and Estonian language exams for obtaining citizenship. The Reform Party also called for rolling back Russian-language education in the country's school system.

Observers assert that EKRE benefitted in the 2019 election from antiestablishment sentiment among voters and gained support by appealing to rural Estonians who feel economically left behind.9 In addition to opposing immigration, EKRE is adamantly nationalist, skeptical of the EU, and anti-Russia. Some analysts suggest there is a potential for friction between the Center Party and EKRE on issues such as citizenship, immigration, and abortion policy.10

In 2016, Estonia's parliament unanimously elected Kersti Kaljulaid as president. Kaljulaid is the country's youngest president (aged 46 at the time of her election) and its first female president. A political outsider with a background as an accountant at the European Court of Auditors, she was put forward as a surprise unity candidate after Estonia's political parties were unable to agree on the first round of candidates. The president serves a five-year term and has largely ceremonial duties but plays a role in defining Estonia's international image and reflecting the country's values.

Latvia

Latvia at a Glance Population: 1.929 million Ethnicity: 62% Latvian, 25.4% Russian Languages: Latvian is the official language and first language of 56.3% of the population; Russian is the first language of 33.8% of the population. Religion: 63.7% listed as unspecified, 19.6% Lutheran, 15.3% Orthodox GDP, 2018 (Current Prices): $34.882 billion; per capita GDP approximately $18,033 Currency: euro(€), €1 is approximately $1.10 Political Leaders: President: Egils Levits; Prime Minister: Krišjānis Kariņš; Foreign Minister: Edgars Rinkēvičs; Defense Minister: Artis Pabriks Sources: IMF, "World Economic Outlook Database," October 2019; CIA, World Factbook. |

Latvia's Octoberunable to secure enough support from potential coalition partners to form a government.5 Instead, the populist center-left Center Party, which came in second place with 23.1% of the vote (26 seats), formed a government after it reversed its campaign pledge to not work with the far-right Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE), 2 In the 117th Congress, the cochairs of the House Baltic Caucus are Rep. Don Bacon and Rep. Ruben Gallego. The cochairs of the Senate Baltic Freedom Caucus are Sen. Richard Durbin and Sen. Charles Grassley.

3 See, for example, Rein Taagepera, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia: 100 Years of Similarities and Disparities, International Center for Defence and Security (Estonia), February 16, 2018, at https://icds.ee/lithuania-latvia-and-estonia-100-years-of-similarities-and-disparities/.

4 Estonian Public Broadcasting, “Estonia’s New Government Takes Office,” July 18, 2022. 5 See full election results at https://rk2019.valimised.ee/en/election-result/election-result.html.

Congressional Research Service

2

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

which came in third place. The three-party coalition government of the Center Party, EKRE, and Isamaa collapsed in January 2021, when Prime Minister Juri Ratas of the Center Party resigned due to a corruption scandal involving members of his party.

The Reform Party subsequently took over leadership of the government after reaching a

Estonia: Basic Facts

coalition agreement with the Center Party, with

Population: 1.33 million

Kaja Kallas becoming the country’s first female

Ethnicity: 68.7% Estonian, 24.8% Russian

prime minister. The coalition comprised two

Languages: Estonian is the official language and first

parties with a history of differing ideologies and

language of 68.5% of the population; Russian is the

opposing policies.6 The arrangement collapsed

first language of 29.6% of the population.

in June 2021 due to differences over education

Religion: 70.8% listed as none or unspecified, 16.2%

reform and social welfare spending.7 Prime

Orthodox, 9.9% Lutheran

Minister Kallas briefly led a minority

Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 2021

government before forming the new coalition

(Current Prices): $36.287 billion; per capita GDP

the following month.

approximately $27,282 Currency: euro (€)

The Reform Party previously led a series of

Political Leaders: President: Alar Karis; Prime

coalition governments from 2005 to 2016. The

Minister: Kaja Kallas; Foreign Minister: Urmas Reinsalu;

Center Party, whose support comes largely from

Defense Minister: Hanno Pevkur

Estonia’s Russian-speaking population, led the

government from 2016 to 2019. In 2016, a

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), World

change in the party’s leadership reoriented the

Economic Outlook Database, April 2022; Central

Center Party away from a pro-Russia outlook to

Intelligence Agency (CIA), World Factbook.

one more aligned with NATO and the EU.

The next election is due in March 2023.

In August 2021, Estonia’s parliament elected Alar Keris as President of Estonia. Keris formerly served as Auditor General of Estonia and director of the Estonian National Museum.8 The president is elected indirectly by the Riigikogu and regional electoral colleges and serves a five-year term. The president has largely ceremonial duties but plays a role in defining Estonia’s international image and expressing the country’s values.

Latvia Prime Minister Krisjanis Karins of the center-right New Unity Party (JV) leads a four-party coalition government in Latvia.9 Latvia’s 2018 general election produced a fragmented result, with seven parties winning seats in the country'’s 100-seat unicameral parliament (Saeima).10 JV s 100-seat unicameral parliament (Saeima).11 After three months of negotiations and deadlock, a five-party coalition government took office in January 2019. Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš of the center-right New Unity Party (JV) leads the government.12

JV leveraged its experience as a member of the previous governing coalition to put together and lead the new government despite being the smallest party in the Saeima, with eight seats. The other coalition members are the conservative, nationalist National Alliance (NA) and three new parties: the antiestablishment Who Owns the State? (KPV LV); the New Conservative Party (JKP), which campaigned on an anti-corruption platform; and the liberal Development/For! alliance. The coalition partners hold a combined 61 seats in the Saeima and appear likely to maintain the broadly center-right, fiscally conservative, and pro-European policies followed by recent Latvian governments.

At the same time, the strong showings in the election by KPV LV and JKP (each won 16 seats) appeared to reflect deepening public dissatisfaction with corruption and the political establishment following high-profile bribery and money-laundering scandals in 2018.13 The three parties of the previous coalition government, the centrist Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS), the Unity Party (rebranded New Unity in 2018), and the NA, lost nearly half their total seats, dropping from a combined 61 seats to 32 seats.14

The center-left Harmony Social Democratic Party (SDPS), which draws its support largely from the country's ethnic Russian population, remained the largest party in parliament, with 23 seats. With five of the seven parties in the coalition government, the SDPS and ZZS are the parliamentary opposition. The next general election is scheduled to take place in 2022.

On May 29, 2019, the Saeima elected Egils Levits to be Latvia's next president. A former judge at the European Court of Justice, Levits formally took office on July 8, 2019. Outgoing President Raimonds Vejonis of the ZZS declined to run for a second term. The president performs a mostly ceremonial role as head of state but also acts as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and has the power to propose and block legislation.15

Lithuania

Lithuania at a Glance Population: 2.784 million Ethnicity: 84% Lithuanian, 6.6% Polish, 5.8% Russian Languages: Lithuanian is the official language and first language of 82% of the population; Russian is the first language of 8% of the population; Polish is the first language of 5.6% of the population. Religion: 77.2% Roman Catholic, 4.1% Russian Orthodox, 10.1% listed as unspecified GDP, 2018 (Current Prices): $53.302 billion; per capita GDP approximately $18,994 Currency: euro(€), €1 is approximately $1.10 Political Leaders: President: Gitanas Nausėda; Prime Minister: Saulius Skvernelis; Foreign Minister: Linas Linkevičius; Defense Minister: Raimundas Karoblis

|

Lithuania has a centrist coalition government composed of four political parties and led by the center-right Lithuanian Peasants and Greens Union (LVŽS). The LVŽS emerged as the surprise winner of the country's October 2016 parliamentary election, winning 54 of the 141 seats in the Lithuanian parliament (Seimas) after winning one seat in the 2012 election.16

The prime minister of Lithuania is Saulius Skvernelis, a politically independent former interior minister and police chief who was selected for the position by the LVŽS (while remaining independent, Skvernelis campaigned for the LVŽS). A major factor in the 2016 election outcome was the perception that Skvernelis and the LVŽS remained untainted by a series of corruption scandals that negatively affected support for most of Lithuania's other political parties.17

The LVŽS initially formed a coalition government with the center-left Social Democratic Party of Lithuania (LSDP), which led the previous coalition government following the 2012 election.18 In September 2017, the LSDP left the coalition amid tensions over the slow pace of tax and pension reforms intended to reduce economic inequality. Prime Minister Skvernelis subsequently led a minority government of the LVŽS and the Social Democratic Labour Party of Lithuania (LSDDP), a new party that splintered off from the LSDP.

In July 2019, the LVŽS and the LSDDP reached an agreement to form a new coalition government with the addition of the nationalist-conservative Order and Justice Party and the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania-Christian Families Alliance. The four parties in the current coalition control a parliamentary majority, with a combined 76 out of 141 seats in the Seimas. The coalition's domestic agenda focuses primarily on boosting social programs, including greater spending on social insurance and increased benefits for families, students, and the elderly.19 The opposition parties are the center-right Homeland Union-Lithuanian Christian Democrats, which came in second place in the 2016 election with 31 seats; the LSDP; and the center-right Liberal Movement. The next general election is scheduled to take place in October 2020.

Gitanas Nausėda, a pro-European, politically independent centrist and former banker, won Lithuania's May 2019 presidential election.20 He replaces Dalia Grybauskaitė, who served as president from 2009 to 2019 and was consistently regarded as Lithuania's most popular politician. The powers of the Lithuanian presidency, the only presidency in the Baltic states to be directly elected, are weaker than those of the U.S. presidency. However, the Lithuanian president plays an important role in shaping foreign and national security .

17% in September 2021 to 10%, likely owing to the party’s past ties with the United Russia party of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In 2019, the Saeima elected Egils Levits, a former judge at the European Court of Justice, to be Latvia’s president. The president serves a four-year term and performs a mostly ceremonial role as head of state but also acts as commander-in-chief of the armed forces and can propose and block legislation.14

Lithuania Prime Minister Ingrida Simonyte of the center-right Homeland Union-Lithuanian Christian Democrats (TS-LKD) leads the government of Lithuania. TS-LKD came in first place in Lithuania’s October 2020 election, winning 50 out of 141 seats in the unicameral Lithuanian parliament (Seimas).15 Analysts observed that the main issues in the election included the previous government’s handling of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and

11 John O’Donnell and Gederts Gelzis, “Corruption Scandal Casts Long Shadow over Latvia,” Reuters, April 12, 2019. 12 See Central Election Commission, https://sv2018.cvk.lv/pub/ElectionResults. 13 Politico Europe, “Latvia—National Parliament Voting Intention,” June 8, 2022. 14 Corinne Deloy, Egils Levits, Candidate Supported by the Government Coalition Parties, Should Become the Next President of the Republic of Latvia, Robert Schumann Foundation, May 27, 2019.

15 Seimas, Results of the 2020-2024 Parliament Elections.

Congressional Research Service

4

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

competing plans on how to reduce economic disparities between urban and rural areas.16 The government is a three-party coalition that also includes the center-right Liberal Movement and the center-left Freedom Party; the coalition controls a narrow parliamentary majority with a combined 74 seats.

The main opposition parties are the centrist

Lithuania: Basic Facts

Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (LVZS),

Population: 2.79 million

which led the government from 2016 to 2020,

Ethnicity: 84.1% Lithuanian, 6.6% Polish, 5.8%

the center-left Social Democratic Party of

Russian

Lithuania (LSDP), which led the government

Languages: Lithuanian is the official language and

from 2012 to 2016, and the new Union of

first language of 82% of the population; Russian is the

Democrats “For Lithuania.”

first language of 8% of the population; Polish is the first language of 6% of the population.

The next parliamentary election is due in 2024.

Religion: 77.2% Roman Catholic, 4.1% Orthodox,

Lithuania’s president is Gitanas Nauseda, a pro-

10.1% listed as unspecified

European, politically independent centrist and

GDP, 2021 (Current Prices): $65.479 billion; per

former banker who was elected in 2019.

capita GDP approximately $23,473

17 The

president is elected directly for a five-year term.

Currency: euro(€)

The Lithuanian president plays an important

Political Leaders: President: Gitanas Nauseda; Prime Minister: Ingrida Simonyte; Foreign Minister: Gabrielius

role in shaping foreign and national security

Landsbergis; Defense Minister: Arvydas Anusauskas

policy, is commander-in-chief of the armed

policy, is commander-in-chief of the armed forces, appoints government officials, and has the power to veto legislation.

Efforts to combat corruption remain a focus of Lithuania's government. Following a series of bribery scandals involving leading politicians and one of the country's largest companies, the Seimas adopted a new law in 2018 appointing special prosecutors to investigate cases of political corruption.21

|

Russian Speakers in the Baltic States The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 left millions of ethnic Russians living outside Russia's borders. Russian speakers make up about 30% of Estonia's total population, and 90% of the population in some of its eastern regions. About 34% of Latvia's population speaks Russian as their first language; many of Latvia's ethnic Russians are concentrated in urban areas such as Riga and Daugavpils, the country's second-largest city. Lithuania has a much smaller percentage of Russian-speakers, approximately 8%. Researchers caution against implicit assumptions that the Baltic states' Russian-speaking communities monolithically support Russia or pro-Russian narratives; surveys indicate a diversity of attitudes within these communities with regard to viewpoints toward Russia and Russia-related questions. Nevertheless, the Baltic states' Russian-speaking populations remain a significant factor in both Russian policy toward the region and assessments of the potential security threat posed by Russia (see "Potential Hybrid Threats" section, below). Sources: Paul Goble, "Experts: Estonia Has Successfully Integrated Nearly 90% of its Ethnic Russians," Estonian World, March 1, 2018; Mārtinš Hiršs, The Extent of Russia's Influence in Latvia, National Defence Academy of Latvia, Center for Security and Strategic Research, November 2016; CIA, World Factbook. |

Economic Issues

The 2008-2009 global economic crisis hit the Baltic states especially hard; each of the three countries experienced an economic contraction of more than 14% in 2009. The social costs of the recession and the resulting budget austerity included increased poverty rates and income inequality and considerable emigration to wealthier parts of the EU. The Baltic economies have since rebounded, however, benefitting from strong domestic consumption, external demand for exports, and investment growth (including from EU funding):22

- Estonia's gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 5.8% in 2017 and 4.8% in 2018. It is forecast to grow by 3.2% in 2019 and 2.9% in 2020. Unemployment declined from 16.7% in 2010 to 5.4% in 2018.

- Latvia's GDP grew by 4.6% in 2017 and 4.8% in 2018; it is forecast to grow by 2.8% in 2019 and 2.8% in 2020. Unemployment declined from 19.5% in 2010 to 7.4% in 2018.

- Lithuania's GDP grew by 4.1% in 2017 and 3.5% in 2018; it is forecast to grow by 3.4% in 2019 and 2.7% in 2020. Unemployment declined from 17.8% in 2010 to 6.1% in 2018.

Baltic States Trade at a Glance Estonia Top Trading Partners: Finland, Russia, Germany, Sweden, Latvia, China, Lithuania Leading Exports: electronic equipment, including computers; mineral fuels; wood and wood products Latvia Top Trading Partners: Lithuania, Estonia, Germany, Russia, Poland, Sweden Leading Exports: wood and wood products; electronic equipment, including computers; machinery and mechanical appliances Lithuania Top Trading Partners: Russia, Germany, Poland, Latvia, United States, Italy Leading Exports: mineral fuels; machinery and mechanical appliances; furniture Source: World Bank, "World Integrated Trade Solution Database." |

Despite the crisis and aftermath, each of the Baltic states fulfilled a primary economic goal when each adopted the euro as its currency (Estonia in 2011, Latvia in 2014, and Lithuania in 2015).

The public finances of the Baltic states remain well within guidelines set by the EU (which require member states to have an annual budget deficit of less than 3% of GDP and maintain government debt below 60% of GDP). Both Estonia and Latvia recorded a budget deficit below 1% of GDP in 2018, and Lithuania had a small budget surplus. Gross government debt in 2018 was approximately 8.3% of GDP for Estonia (making it the EU's least-indebted member state), 35.9% of GDP for Latvia, and 34.2% of GDP for Lithuania.23

According to a study by the European Commission, foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Baltic states remains below precrisis levels.24 With considerable investment in the financial services sector, Sweden is the largest foreign investor in the region, followed by Finland and the Netherlands. Estonia has been the most successful of the three Baltic countries in attracting FDI, with FDI equivalent to approximately 100% of gross value added in 2015, compared to approximately 63% for Latvia and 40% for Lithuania.25

Banking Sector Concerns

U.S. and European authorities have expressed concerns about the practices of banks in the region that cater to nonresidents, largely serving account holders based in Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union. In 2018, two scandals in particular brought attention to money-laundering challenges in the region.

In February 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated ABLV Bank, then the third-largest bank in Latvia, as a financial institution of primary money laundering concern. Treasury accused it of money laundering, bribery, and facilitating transactions violating United Nations sanctions against North Korea.26 Following a run on deposits and a decision by the European Central Bank not to intervene, ABLV initiated a process of self-liquidation.27 The Latvian government subsequently made reforming the banking sector and strengthening anti-money-laundering (AML) practices top policy priorities.

A September 2018 report commissioned by Danske Bank, Denmark's largest bank, indicated that between 2007 and 2015, some €200 billion (approximately $220 billion) worth of suspicious transactions may have flowed through a segment of its Estonian branch catering to nonresidents, primarily Russians.28 The activity continued despite critical reports by regulatory authorities and whistleblower accounts highlighting numerous failures in applying AML practices. In February 2019, the Estonian Financial Supervision Authority ordered Danske Bank to cease operations in Estonia; Danske Bank subsequently decided to cease its activities in Latvia and Lithuania (and Russia), as well.29

forces, appoints government officials, and has

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook Database,

the power to veto legislation.

April 2022; CIA, World Factbook.

Economic Issues The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the Baltic states’ economies, but less so than it did the economies of most other EU countries (the EU economy as a whole contracted by more than 6% in 2020).

Estonia’s gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by 3% in 2020 before

rebounding to 8.3% growth in 2021. Growth is forecast to be 0.2% in 2022. Unemployment is 7.2%.18

Latvia’s GDP contracted by 3.8% in 2020 before growing 4.7% in 2021. Growth

is forecast to be 1.0% in 2022. Unemployment is 8.1%.

Lithuania’s GDP contracted by 0.1% in 2020 before growing 4.9% in 2021.

Growth is forecast to be 1.8% in 2022. Unemployment is 7.3%.

The Baltic states each use the euro as their currency (Estonia adopted the euro in 2011, Latvia in 2014, and Lithuania in 2015).

As in many other countries, high inflation and rising energy and commodity costs pose challenges to the Baltic states’ economies. As of June 2022, the Baltic states had the three highest increases in annual inflation among the 19 countries using the euro; year-on-year inflation was 22% in

16 Euronews, “Lithuania Votes: Centre-Right Opposition Wins Second Round of Legislative Elections,” October 26, 2020.

17 Andrius Sytas, “Lithuania’s Nauseda Wins Presidential Election,” Reuters, May 26, 2019. 18 Economic statistics from International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2022. Figures rounded to the nearest tenth of a percent.

Congressional Research Service

5

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

Estonia, 20.5% in Lithuania, and 19% in Latvia, compared with the euro area average of 8.6%.19 Additionally, sectors reliant on trade with Russia, including importers of steel, wood, and fertilizer, are affected negatively by EU sanctions on Russia.

With considerable investment in the financial services sector, Sweden is the largest foreign investor in the region, followed by Finland and the Netherlands.20 Major regional trading partners include Finland, Germany, Poland, Russia, and Sweden.21

Response to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine The Baltic states have been outspoken in condemning Russia’s 2022 war against Ukraine and expressing their view that Russia’s aggressive ambitions may well go beyond Ukraine. The Baltic states have committed substantial military and financial support to Ukraine. According to the nongovernmental Kiel Institute, which tracks international aid to Ukraine, the Baltic states provided an estimated €613 million (approximately $597 million) in bilateral military assistance and €692 million (approximately $673 million) in total bilateral assistance (military plus financial and humanitarian assistance) to Ukraine between January 24 and August 3, 2022.22 Over the same time period, in terms of total bilateral assistance to Ukraine as a percentage of GDP, Estonia ranked as the top country in the world (0.83%), Latvia ranked second (0.8%), and Lithuania ranked fifth (0.32%), according to the Kiel Institute.23 Military assistance to Ukraine from the Baltic states has included Javelin anti-tank missiles, Stinger anti-aircraft missiles, other air defense and anti-tank weapons, howitzers, armored vehicles, small arms, grenades, communications equipment, night vision equipment, ammunition, helmets, medical equipment, fuel, and food. As of August 30, 2022, more than 134,000 Ukrainian refugees had registered for temporary protection in the Baltic states (approximately 63,300 in Lithuania, 38,400 in Latvia, and 32,600 in Estonia), equivalent to nearly 2% of the three countries’ combined population.24

The Baltic states have advocated the strongest possible EU sanctions against Russia and have implemented measures beyond those adopted by the EU. The three countries have stopped issuing tourist visas to Russian citizens, for example, and have called for all EU countries to do the same. The Baltic states also have barred entry to Russian tourists seeking to travel to other destinations in Europe.25 Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted the three countries to remove Soviet monuments and World War II memorials as a “risk to public order” and an unwanted reminder of Russia’s former occupation of their territories.26 The parliaments of the Baltic states have adopted resolutions describing Russia’s actions in Ukraine as genocide, and the parliaments of Lithuania and Latvia have declared Russia a “terrorist state” and a “state sponsor of terrorism,”

19 Eurostat, “Euro Area Annual Inflation up to 8.6%,” July 1, 2022. 20 Jorge Durán, FDI & Investment Uncertainty in the Baltics, European Commission, March 2019. 21 World Bank, World Integrated Trade Solution Database. 22 Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Ukraine Support Tracker, accessed June 19, 2022. Hereinafter, Kiel Institute. 23 Kiel Institute. Poland, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States rank third, fourth, sixth, and seventh, respectively.

24 European Council and Council of the European Union, “Refugees from Ukraine in the EU,” infographic, September 5, 2022.

25 Andrew Higgins, “The Baltic States Agree to Bar Land Crossings by Russian Tourists,” New York Times, September 7, 2022.

26 Euronews, “Estonia to Remove Soviet-Era Monuments to ‘Ensure Public Order,’” August 17, 2022.

Congressional Research Service

6

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

respectively.27 Latvia suspended all Russia-based television channels in June 2022;28 Estonia and Lithuania also have banned numerous Russian television channels from broadcasting or retransmission. EU sanctions block access to state-owned Russian media (Sputnik and Russia Today) in all member countries.29

Since the invasion, the Baltic states have made additional plans to increase their defense spending and acquire new military capabilities. They also have advocated for a substantial increase in the U.S. and NATO forces stationed on their territory (see Regional Security Concerns and Responses below).

Regional Relations with the United States Regional Relations with the United States

The U.S. State Department describes Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania as strong, effective, reliable, and valuedand reliable allies that have helped to promote security, stability, democracy, and prosperity in Europe and beyond.3030 Many citizens of the Baltic states remain grateful to the United States for consistently supporting their independence throughout the Cold War and playing a key role in promoting the restoration of their independence in 1991. Most policymakers in the Baltic states tend to see their countries'countries’ relationship with the United States as the ultimate guarantor of their security against pressure or possible threats from Russia. All three Baltic states joined NATO and the EU in 2004 with the full backing of the United States. Successive U.S. Administrations have maintained strong bilateral partnerships with the Baltic states and have expressed a continued U.S. commitment to ensuring the security of the Baltic region.31

with strong U.S. support.

In addition to maintaining a pro-NATO and pro-EU orientation, the Baltic states have sought to support U.S. foreign policy and security goals. For example, they have worked closely with the United States in Afghanistan, where the three Baltic states have contributed troops to NATO-led missions since 2002-2003.31for nearly two decades. The three countries also have been partner countries in the Global Coalition to Defeat the Islamic State, providing personnel, training, weapons, and funding for efforts to counter the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria since 2014.32

The Trump Administration and many Members of Congress have demonstrated support for strong U.S. relations with the Baltic states. In April 2018, President Donald Trump hosted the presidents of the three Baltic states for a quadrilateral U.S.-Baltic Summit intended to deepen security and defense cooperation and reaffirm the U.S. commitment to the region.33 The presidential summit was followed by a U.S.-Baltic Business Summit intended to expand commercial and economic ties.34

During the 115th Congress, the Senate adopted a resolution (S.Res. 432) congratulating Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania on the 100th anniversary of their independence; applauding the U.S.-Baltic partnership; commending the Baltic states' commitment to NATO, transatlantic security, democracy, and human rights; and reiterating the Senate's support for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) as a means of enhancing Baltic security (on EDI, see "U.S. European Deterrence Initiative," below).35

Security Partnership and Assistance

The United States provides significant security assistance to its Baltic partners. According to the State Department, as of July 2019, U.S. security assistance to the Baltic states has included

- more than $450 million in defense articles sold under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program and more than $350 million in defense articles authorized under the Direct Commercial Sales process since 2014;

- more than $150 million in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) since 2015, with the aim of strengthening the Baltic states' defensive capabilities in areas such as hybrid warfare, electronic warfare, border security, and air and maritime domain awareness and enhancing interoperability with NATO forces;

- approximately $1.2 million annually per country in International Military Education and Training (IMET) funds contributing to the professional education of military officers; and

- $290 million in funding from the Department of Defense under Title 10 train and equip programs since 2015, including approximately $173 million in FY2018.36

Since 1993, the Baltic states have participated in the U.S. National Guard State Partnership Program. Under the program, Estonia's armed forces partner with units from the Maryland National Guard, Latvia's armed forces partner with the Michigan National Guard, and Lithuania's armed forces partner with the Pennsylvania National Guard.37

In 2017, the United States signed separate bilateral defense cooperation agreements with each of the Baltic states. The agreements enhanced defense cooperation by building on the NATO Status of Forces Agreement to provide a more specific legal framework for the in-country presence and activities of U.S. military personnel.38

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018 (P.L. 115-91) authorized the Department of Defense to conduct or support a security assistance program to improve the Baltic states' interoperability and build their capacity to deter and resist aggression. The program was authorized through 2020 with a spending limit of $100 million.

In November 2018, the United States and the three Baltic states agreed to develop bilateral 32

During the 117th Congress, the Senate adopted a resolution (S.Res. 499) celebrating 100 years of diplomatic relations between the United States and the Baltic states and committing to continued economic and security cooperation. A similar resolution (H.Res. 1142) was introduced in the House of Representatives.

27 Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “Lithuania Adopts Resolution Calling Russia ‘Terrorist State,’ Accuses Moscow of ‘Genocide,’” May 10, 2022; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “Latvian Parliament Designates Russia a State Sponsor of Terrorism,” August 11, 2022. 28 Public Broadcasting of Latvia, “All Russia-Based TV Channels Banned in Latvia,” June 6, 2022. 29 Council of the European Union, EU Imposes Sanctions on State-Owned Outlets RT/Russia Today and Sputnik’s Broadcasting in the EU, March 2, 2022.

30 See U.S. Department of State, U.S. Relations with Estonia, December 3, 2020; U.S. Relations with Latvia, December 3, 2020; and U.S. Relations with Lithuania, August 5, 2020.

31 See White House, “Remarks by Vice President Harris, President Levits of Latvia, President Nausėda of Lithuania, and Prime Minister Kallas of Estonia Before Multilateral Meeting,” February 18, 2022; and “Readout of President Biden’s Meeting with Prime Minister Kaja Kallas of Estonia, President Egils Levits of Latvia, and President Gitanas Nauseda of Lithuania,” June 14, 2021. Also see White House, A Declaration to Celebrate 100 Years of Independence of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and Renewed Partnership, April 4, 2018.

32 See Global Coalition Against Daesh, https://theglobalcoalition.org/en/.

Congressional Research Service

7

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

Security Partnership and Assistance The United States provides significant security assistance to the Baltic states. Recent highlights include the following:

The Baltic Security Initiative (BSI) directs U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)

security cooperation funding to the Baltic states.33 Congress appropriated nearly $169 million for the BSI in FY2021 and $180 million in FY2022.34 Developing the Baltic states’ air defense systems has been a priority of DOD security assistance.

The Baltic Defense and Deterrence Act, introduced in the House of

Representatives (H.R. 7290) and the Senate (S. 3950) in March 2022, would codify the BSI, authorize $250 million in DOD funding for the BSI annually from FY2023 through FY2027, and establish a complementary Baltic Security and Economic Enhancement Initiative at the State Department.

From FY2018 to FY2021, the United States provided the Baltic states with $252

million in security assistance through the State Department’s Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program and approximately $18.3 million through the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program.35 The Administration’s FMF and IMET requests for the three countries total approximately $162.3 million for FY2022 and $165.3 million for FY2023.

Since FY2015, the State Department has notified Congress of approximately $2

billion in proposed sales of defense articles and services to the Baltic states under the Foreign Military Sales program.36

In 2019, the United States and the three Baltic states signed separate bilateral

defense cooperation strategic road maps focusing on specific areas of security cooperation for the period 2019-2024. In April 2019, the United States and Lithuania signed a road map agreeing to strengthen cooperation inAreas of emphasis include training, exercises, and multilateral operations; improveimproving maritime domain awareness in the Baltic Sea; improveimproving regional intelligence-sharing, surveillance, and early warning capabilities; and buildbuilding cybersecurity capabilities.

Since 1993, the Baltic states have participated in the U.S. National Guard State

Partnership Program. Under the program, Estonia’s armed forces partner with units from the Maryland National Guard, Latvia’s armed forces partner with the Michigan National Guard, and Lithuania’s armed forces partner with the Pennsylvania National Guard.

33 See CRS In Focus IF11677, Defense Primer: DOD “Title 10” Security Cooperation, by Christina L. Arabia. 34 Funding for the Baltic Security Initiative was included in the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2021, passed in December 2020 as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (P.L. 116-260), and the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2022, passed in March 2022 as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 (P.L. 117-103).

35 State Department Congressional Budget Justifications, FY2020-FY2023. Data may not account for all recent increases in appropriations for the Baltic states.

36 Defense Security Cooperation Agency, “Major Arms Sales,” at https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales.

Congressional Research Service

8

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

cybersecurity capabilities.39 In May 2019, the United States signed road map agreements with Latvia and Estonia outlining similar priorities for security cooperation.40

In the 116th Congress, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92) extended security assistance to the Baltic states for building interoperability and deterrence through 2021 and increased the total spending limit to $125 million. The act also requires the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of State to jointly conduct a comprehensive assessment of the military requirements necessary to deter and resist Russian aggression in the region.

The committee report (S.Rept. 116-103) for the Senate version of the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2020 (S. 2474), recommends allocating $400 million to the Defense Cooperation Security Agency to fund a Baltics regional air defense radar system.

A sense of Congress resolution introduced in the House of Representatives (H.Res. 416) would reaffirm U.S. support for the Baltic states' sovereignty and territorial integrity and encourage the Administration to further defense cooperation efforts. Partially reflected in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, the Baltic Reassurance Act (H.R. 3064) introduced in the House of Representatives would reiterate the U.S. commitment to the security of the Baltic states and require the Secretary of Defense to conduct a comprehensive regional defense assessment.

Economic Relations

Economic Relations U.S. economic ties with the three Baltic states remain relatively limited, although the State Department has statedasserts that there are "“growing commercial opportunities for U.S. businesses"” and "“room for growth" in the relationship.41

In 2018” in economic relations.37 In 2021, U.S. goods exports to Estonia were valued at $346.1449.8 million and goods imports from Estonia were valued at$953.5 million.42more than $1.9 billion.38 Main U.S. exports to Estonia are computer and electronic products,chemicals,machinery, and transportation equipment; Estonia'’s top exports to the United States are computer and electronic products, machineryproducts, petroleum products and chemicals, electrical equipment, andmedical instruments.43wood products. U.S. affiliates employ about 3,570000 people in Estonia, and U.S.FDIforeign direct investment (FDI) in Estonia wasabout $100$74 million in2017.44In 20182020.39 In 2021, U.S. goods exports to Latvia were valued at $510.4413.2 million and goods imports from Latvia were valued at $727.1 million.45686.3 million.40 Main U.S. exports to Latviaare transportation equipment and computer and electronic products;and top U.S. imports from Latviaareboth consist of transportation equipment, beverage products, and computer and electronic productsand transportation equipment. U.S. affiliates employ about 1,325700 people in Latvia, and U.S. FDI in Latvia was $7137 million in2017.46In 2018, U.S.2020.41 In 2021, U.S. goods exports to Lithuania were valued at$706.4 million and imports from Lithuania were valued at nearly $1.268 billion.47nearly $1.24 billion and goods imports from Lithuania were valued at more than $2 billion.42 Main U.S. exports to Lithuania are used machinery,chemicals, computer and electronic products, and transportation equipmentliquefied natural gas (LNG), transportation equipment, and chemicals; top U.S. imports from Lithuania are petroleum and coal products, chemicals, and furniture. U.S. affiliates employ about2,2505,100 people in Lithuania, and U.S. FDI in Lithuania was $182 million in 2020.43 Regional Security Concerns and Responses Over the past two decades, officials in the Baltic region increasingly have viewed Russia as a threat to their countries’ security. Baltic officials have expressed concern overpeople in Lithuania, and Lithuania has not attracted significant levels of U.S. FDI.48

Regional Security Concerns and Responses

Officials in the Baltic region have noted with concern what they view as increasing signs of Russian foreign policy assertiveness. These signs include a buildup of Russian forces in the region, large-scale military exercises, and incursions by Russian military aircraft into Baltic states'’ airspace.44

Russia’s 2022 war against Ukraine has significantly intensified NATO concerns that airspace.49

Unlike Georgia and Ukraine, the Baltic states (as well as Moldova and Georgia, which are not NATO members) could be targets for aggressive Russian ambitions beyond Ukraine. The presence of a large ethnic Russian population in the Baltic states, particularly in Latvia and Estonia, also is a factor in these concerns, given that

37 U.S. Department of State, U.S. Relations with Latvia, December 3, 2020; and U.S. Relations with Lithuania, August 5, 2020.

38 U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with Estonia.” 39 Daniel S. Hamilton and Joseph P. Quinlan, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, The Transatlantic Economy 2022, p. 156. Hereinafter, Hamilton and Quinlan, Transatlantic Economy.

40 U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with Latvia.” 41 Hamilton and Quinlan, Transatlantic Economy, p. 164. 42 U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with Lithuania.” 43 Hamilton and Quinlan, Transatlantic Economy, p. 165. 44 Jaroslaw Adamowski and Martin Banks, “Without a NATO-Wide Effort, the Skies Along the Northeastern Flank Could Be in Peril,” DefenseNews, June 16, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 4 Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

Russian claims of persecution against Russian communities were a large part of Russia’s pretext for its invasion of Ukraine. One of the central principles of Russian foreign policy is to act as the defender and guarantor of the “rights” of Russian-speaking people wherever they live.45

Scenarios for Russian action against the Baltic states include a full invasion after a military buildup, with the aim of capturing the region and closing it off from NATO reinforcements; an attempted land grab following a quick mobilization; and a limited incursion or “ambiguous invasion” similar to the tactics employed in Crimea in 2014.46 Some analysts view a full Russian invasion of the Baltic states as unlikely due to the risk of escalation Russia would face in an open confrontation with NATO; in a March 2022 visit to the region, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken declared that NATO would defend “every inch” of its territory.47 Despite the acute concerns caused by Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Baltic leaders maintain that they see no “immediate threat” of a full-scale Russian invasion against their own countries.48

NATO has increased its deterrent presence in the Baltic states since 2016, with a further increase in 2022, although Russia retains a large advantage in the number of forces in the region. The likely accession of Sweden and Finland into NATO also would substantially enhance the alliance’s ability to defend the Baltic states and prevent a scenario in which Russia might effectively close off the region. Such factors may make Russian action in the region “less likely, but that doesn’t mean it’s unlikely,” according to one Lithuanian analyst; in June 2022, a former Russian prime minister predicted that if Ukraine falls, “the Baltic states will be next.”49

Kaliningrad: Russia’states are members of NATO, and many observers contend the alliance's Article 5 collective defense guarantee limits potential Russian aggression in the Baltic region. Nevertheless, imposing various kinds of pressure on the Baltic states enables Russia to test NATO solidarity and credibility.50

Defense experts assert that Russian forces stationed near the Baltic region, including surface ships, submarines, and advanced S-400 air defense systems, could "allow [Russia] to effectively close off the Baltic Sea and skies to NATO reinforcements."51 According to a RAND report based on a series of war games staged in 2014 and 2015, a quick Russian strike could reach the capitals of Estonia and Latvia in 36-60 hours.52

Kaliningrad: Russia's Strategic Territory on the Baltic s Strategic Territory on the Baltic Sea

Kaliningrad, a 5,800-square-mile Russian exclave on the Baltic Sea located between Poland and Lithuania, is a key strategic territory for Russia, allowing the country to project military power into NATO

Sources: Maria Domańska et al., Fortress Kaliningrad: Ever Closer to Moscow, Centre for Eastern Studies (Warsaw), October 2019; LTG (Ret.) Ben Hodges, Janusz Bugajski, and Peter Doran, Securing the Suwałki Corridor, Center for European Policy Analysis, July 2018; Dominik Jankowski, Six Ways NATO Can Address the Russian Challenge, Atlantic Council, July 4, 2018; "Russia Deploys Iskander Nuclear-Capable Missiles to Kaliningrad," Reuters, February 5, 2018. |

Defense Spending and Capabilities

The breakup of the Soviet Union left the Baltic states with virtually no national militaries, and their forces remain small and limited (see Table 1). The Baltic states' defense planning consequently relies heavily on NATO membership, and these states have emphasized active participation in the alliance through measures such as contributing troops to NATO's ’s mission in Afghanistan. In the context ofPrompted by Russia's invasion of Ukraine and renewed concerns about Russia’s aggression against Ukraine since 2014, the Baltic states have significantly increased their defense budgets and sought to acquire new military capabilities.

acquired new capabilities. All three countries exceed NATO’s target for member states to allocate at least 2% of GDP for defense spending, and all three plan for defense spending to reach 2.5% of GDP either in 2022 (Lithuania and Estonia) or by 2025 (Latvia).

Lithuania has the largest military of the three Baltic states, with 19,85023,000 total active duty personnel in 2019.53and 7,100 reserves.50 According to NATO, Lithuania has increased its’s defense spending increased from $428 from $427 million in 2014 to an expected $1.084$1.318 billion in 20192021, equivalent to 1.98% of GDP (NATO recommends that member states allocate 2% of GDP for defense spending).54 The defense ministry has moved ahead with plans to acquire new self-propelled artillery systems and portable anti-aircraft missiles, as well as elements of a medium-range air defense system. After abolishing conscription in 2008, Lithuania reintroduced compulsory military service in 2015 due to concerns about Russia, a move that brings 3,000 personnel to the armed forces per year.

According to NATO, Estonia's defense spending is expected to be 2.13% of GDP ($669 million) in 2019.55 The country's armed forces total 6,600 active personnel and 12,000 reserves, plus a volunteer territorial defense force with about 15,800 members.56 Estonia has taken steps to upgrade its air defense system and modernize a range of ground warfare equipment, including anti-tank weapons. Estonia has compulsory military service for men aged 18-27, with an eight-month basic term of conscripted service.

Latvia's armed forces total 6,210 active personnel.572.03% of GDP.51 In the past several years, the Lithuanian armed forces have acquired new self-propelled artillery, infantry fighting vehicles, and short- to medium-range air defense systems. Lithuania is in the process of acquiring new anti-tank weapons, including Javelin missiles.

Estonia’s defense spending was 2.16% of GDP ($771 million) in 2021.52 The country’s armed forces total 7,200 active personnel and 17,500 reserves.53 Acquisitions by the Estonian armed forces over the past several years include new self-propelled artillery, infantry fighting vehicles, and Javelin anti-tank missiles. Estonia is in the process of acquiring new rocket artillery systems, coastal defense systems, and short- to medium-range air defense systems.

Latvia’s armed forces total 8,750 active personnel and 11,200 reserves.54 According to NATO figures, Latvia has more than doubled its defense spending as a percentage of GDP over the past five years, from 0.94% of GDP in 2014 to 2.0116% of GDP ($724835 million) in 2021.55 Acquisition projects underway for the Latvian armed forces include armored personnel carriers, self-propelled artillery, and Black Hawk helicopters.

Table 1. Baltic States Defense Information

Active Armed

Armed Forces

2021 Defense

Defense Spending %

Forces Personnel

Reserves

Expenditure

of GDP

Estonia

7,200

17,500

$771 million

2.16

Latvia

8,750

11,200

$835 million

2.16

Lithuania

23,000

7,100

$1.318 billion

2.03

Sources: International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance 2022 million) in 2019.58 Acquisition priorities of the Latvian armed forces include self-propelled artillery, armored reconnaissance vehicles, multi-role helicopters, anti-aircraft missiles, and anti-tank missiles.

|

Active Armed Forces Personnel |

Reserves |

2019 Defense Budget |

Defense Spending % of GDP |

|

|

Estonia |

6,600 |

12,000 |

$669 million |

2.13 |

|

Latvia |

6,210 |

15,900 |

$724 million |

2.01 |

|

Lithuania |

19,850 |

6,700 |

$1.084 billion |

1.98 |

Sources: International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance 2019 and NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Defence Expenditures of NATO Countries (2012-20192014-2022), June 25, 2019.

U.S. European Deterrence Initiative

Under the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), which was launched in 2014 and originally called the European Reassurance Initiative, the United States has bolstered security cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe with enhanced U.S. military activities in five areas: (1) increased military presence in Europe, (2) additional exercises and training with allies and partners, (3) improved infrastructure to allow greater responsiveness, (4) enhanced prepositioning of U.S. equipment, and (5) intensified efforts to build partner capacity of newer NATO members and other partners.59 As of December 2019, there are approximately 6,000 U.S. military personnel involved in the associated Atlantic Resolve mission at any given time, with units typically operating in the region under a rotational nine-month deployment.60

The United States has not increased27, 2022.

50 International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance 2022, p. 124-125. Hereinafter, IISS, Military Balance.

51 NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Defence Expenditures of NATO Countries (2014-2022), June 27, 2022. Hereinafter, NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Defence Expenditures.

52 NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Defence Expenditures. 53 IISS, Military Balance, pp. 100-101. 54 IISS, Military Balance, pp. 122-123. 55 NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Defence Expenditures.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 16 Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania: Background and U.S.-Baltic Relations

U.S. and NATO Military Presence In 2014, the United States launched the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI, originally called the European Reassurance Initiative) in response to Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine. Under EDI, the United States has rotated about 7,300 U.S.-based military personnel into Central and Eastern Europe, typically under a nine-month deployment, while not increasing its permanent troop presence in Europe.56 The Atlantic Resolve mission, as this rotation is called, includes an Armored Brigade Combat Team and a Combat Aviation Brigade. The forces conduct training and exercises in more than a dozen European countries, including the Baltic states, and the U.S. Army V Corps forward headquarters located in Poznań, Poland is responsible for overseeing mission command of rotational units supporting Atlantic Resolve. EDI funding was $3.8 billion in FY2022, with $4.2 billion requested for FY2023.

Since February 2022, the United States has deployed more than 20,000 additional armed forces personnel to Europe to bolster deterrence and increase alliance defense capabilities, bringing the total number of U.S. military personnel in Europe to more than 100,000 by mid-year.57 Enhanced U.S. rotational deployments in the Baltic states include armored, aviation, air defense, and special operations forces.

At the 2016 NATO Summitpresence in Europe (about 67,000 troops, including two U.S. Army Brigade Combat Teams, or BCTs). Instead, it has focused on rotating additional forces into the region, including nine-month deployments of a third BCT based in the United States.61 The rotational BCT is based largely in Poland, with units also conducting training and exercises in the Baltic states and 14 other European countries.62 The Fourth Infantry Division Mission Command Element, based in Poznań, Poland, acts as the headquarters overseeing rotational units.

EDI funding increased substantially during the first years of the Trump Administration, from approximately $3.4 billion in FY2017 to approximately $4.8 billion in FY2018 and approximately $6.5 billion in FY2019.63 For FY2020, the Administration requested $5.9 billion in funding for the EDI; defense officials explained that the reduced request was due to the completion of construction and infrastructure projects.64 In September 2019, the Department of Defense announced plans to defer $3.6 billion of funding for 127 military construction projects in order to fund construction of the U.S.-Mexico border wall, with approximately $770 million of this money to come from EDI-related projects.65 Affected initiatives in the Baltic states reportedly include the planned construction of a special forces operations and training facility in Estonia.

NATO Enhanced Forward Presence

At the 2016 NATO Summit in Warsaw, the alliance agreed to deploy battalion-sized (approximately 1,100-1,500 troopspersonnel) multinational battle groupsbattlegroups to Poland and each of the three Baltic states (see Figure 2).66 These enhanced forward presence units are intended to deter Russian aggression and emphasize NATO's commitment to collective defense by acting as a tripwire. These Enhanced Forward Presence units are intended to deter Russian aggression by acting as a tripwire that ensures a response from the whole of theentire alliance in the event of a Russian attack. The United Kingdom leads the battlegroup in Estonia, Canada leads the battlegroup in Latvia, and Germany leads the battlegroup in Lithuania. (The United States leads the NATO battlegroup in Poland.)

Although several allies increased their deployments to the battlegroups (see Figure 2) following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Baltic officials have expressed the view that NATO’s tripwire forces are too small to deter Russian aggression.58 Baltic officials have called for NATO to shift to a forward defense strategy with forces sufficient to deny Russia territorial gains in the first place rather than maintaining what one leader called a strategy of “lose it and liberate afterwards.”59 Many officials in the Baltic states advocate establishing permanent U.S. or NATO bases on their territory and call for the alliance to deploy a permanent brigade-sized presence (approximately 3,000-5,000 personnel) in each country.60 NATO countries have discussed plans to form such combat-capable brigades in the Baltic states; initial efforts may include designating units outside the Baltic states that could be deployed rapidly for their defense.61

56 See U.S. Army Europe and Africa, Operation Atlantic Resolve, at https://www.europeafrica.army.mil/AtlanticResolve/.

57 U.S. Department of Defense, “U.S. Defense Contributions to Europe,” fact sheet, June 29, 2022. 58 Jacqueline Feldscher, “‘Obsolete’ NATO Force Presence in Baltics Needs Upgrade, Estonian Defense Leader Says,” DefenseOne, June 15, 2022.