Bolivia’s October 2020 General Elections

Changes from November 14, 2019 to December 19, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

On November 10, 2019, Bolivian PresidentBolivia's Evo Morales of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party resigned and subsequently received asylum in Mexico. Bolivia's military had recommended that Morales step down to prevent an escalation ofhis presidency and sought asylum in Mexico. He ultimately received refugee status in Argentina. Bolivia's military had suggested Morales consider resigning to prevent violence after weeks of protests alleging fraud in the October 20, 2019, presidential election. While Morales has described his ouster as a "coup," the opposition has described it as a "popular uprising" against an authoritarian leader. The threeelection. Three individuals in line to succeed Morales (the vice president and the presidents of the senate and the chamber of deputies) also resigned. Opposition Senator Jeanine Añez, formerly second vice president of the senate, declared herself senate president and then assumed the position of interim president on November 12, 2019; MAS legislators do not recognize her authority.

The U.S. Department of State supported the findings of an Organization of American States (OAS) audit that found enough irregularities in the October elections to recommend a new election. President Trump praised Morales's resignation. State Department officials have called for all parties to refrain from violence and issued a travel warning for Bolivia. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo applauded Añez for stepping up as interim president. Congressional concern about Bolivia has increased. S.Res. 35, approved in April 2019, expresses concern over Morales's efforts to circumvent term limits in Bolivia.

Morales Government (2006-2019)

Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous leader, had governed since 2006 as head of the MAS party. With two-thirds majorities in both legislative chambers, Morales and the MAS transformed Bolivia (see CRS In Focus IF11325, Bolivia: An Overview). They decriminalized coca cultivation, increased state control over the economy, and used natural gas revenue to expand social programs. Morales and the MAS enacted a new constitution (2009) that recognizes indigenous peoples' rights and autonomy and allows for land reform. Previously underrepresented groups, including the indigenous peoples who constitute 40% of the population, increased their representation in government. Traditional Bolivian elites opposed these changes and have become leaders of the recent protests.

The Trump Administration and Congress have expressed concerns regarding irregularities and manipulation in Bolivia's election, violence following the election and Morales's resignation, and the expectation for the interim government to convene free and fair elections as soon as possible. Although Bolivia's economic performance has been strong under Morales, there has been an erosion of some democratic institutions and relations with the United States have deteriorated. Under Morales, annual economic growth averaged some 4.5% from 2006 to 2018 and poverty rates fell from 60% in 2006 to 34.6% in 2018. Governance standards have remained weak, especially those involving accountability, transparency, and separation of powers. The Morales government launched judicial proceedings against opposition politicians, dismissed judges, and restricted press freedom. Morales aligned his country with Hugo Chávez of Venezuela vis-à-vis the United States, and Bolivia-U.S. relations have remained tense since he expelled the U.S. ambassador in 2008interim president on November 12, 2019. Bolivia's constitutional court recognized her succession. After a period of protests and state violence, the MAS-led Congress unanimously approved a law to annul the October elections, select a new electoral tribunal, and have that tribunal convene new elections.

October Elections Annulled

Morales, Bolivia's first indigenous president, transformed Bolivia, but many observers expressed concerns as he sought to remain in office beyond constitutionally mandated term limits (he won elections in 2006, 2009, and 2014). In 2017, Bolivia's Constitutional Tribunal removed limits on reelection established in the 2009 constitution. The decision overruled a 2016 referendum in which voters rejected a constitutional change to allow Morales to serve another term.

|

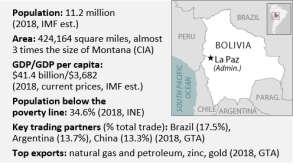

Figure 1. Bolivia at a Glance |

|

|

|

A Disputed Reelection

Many observers expressed concerns about democracy in Bolivia as Morales sought to remain in office beyond his third term (he won reelection in 2009 and 2014). In 2017, Bolivia's Constitutional Tribunal removed constitutional limits on reelection established in the 2009 constitution. The decision overruled a 2016 referendum in which voters rejected a constitutional change to allow Morales to serve another term. Since then, periodic protests have occurred.

In January 2019, Morales won the MAS primary and began campaigning for a fourth term. Opposition candidates included former President Carlos Mesa (2003-2005) of the Civic Community Party; Oscar Ortiz, a senator from the "Bolivia Says No" PartyIn January 2019, Morales began campaigning for a fourth term. Opposition candidates included former President Carlos Mesa (2003-2005); Senator Oscar Ortiz; and Chi Hyun Chung, an evangelical minister from the Christian Democratic Party. Morales needed to win by a 10-point margin in the first-round election round to avoid a second-round runoff.

Allegations of fraud marred Bolivia's first-round election in October 2019. The country's electoral agency said Morales won a narrow victory over Mesa, but Mesa rejected that result. Observers from the Organization of American States (OAS) described irregularities in the process. Mesa called for protesters to demand a new election, while Luis Camacho, head of a civic committee from Santa Cruz, led a nationwide to avoid a second-round runoff in mid-December against a potentially unified opposition.

Bolivia's first-round election in October 2019 was marred by allegations of fraud in the vote tabulation. The country's electoral agency said Morales won a narrow first-round victory, but opposition candidate Mesa rejected that result and OAS election observers described irregularities in the process. Mesa and other opposition leaders called for protesters to demand a new election and then urged them to push for Morales's resignation. On October 30, the Morales government agreed to have the OAS audit the election results and to participate inconvene a runoff election if recommended by the audit. Nevertheless, protests turned increasingly violent, with at least three individuals killed and hundreds injuredcontinued.

On November 10, 2019, the OAS issued the preliminary findings of its electoral audit, which concludedsuggesting serious manipulation of results and found that enough irregularities occurred in the elections to merit a new election. Morales agreed to hold new elections, but his offer did not satisfy the opposition. After a police mutiny, clashes between Morales supporters and the opposition, and an army declaration urging him to step down, Morales resigned and sought asylum in Mexico.

A Constitutional Way Forward?

According to the Bolivian constitution, the national assembly of Bolivia must achieve a quorum to accept Morales's resignation and name an interim government. That interim government would then have 90 days to convene new elections. The MAS-dominated legislature has thus far boycotted legislative sessions. Although the MAS has rejected these developments, Añez declared herself senate president and then assumed the role of interim president. Bolivia's constitutional court declared those actions constitutional. She has named a Cabinet and received some diplomatic recognition. With protesters rejecting her government, the path forward remains unclear.

U.S. Concerns

The United States remains concerned about the political vacuum in Bolivia, but its role in supporting stability and a return to democracy likely will be limited. Bolivia-U.S. relations have remained tense following the 2008 ousting of the U.S. ambassador, and bilateral assistance to the country ended in 2013, after Bolivia expelled the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Following the election in Bolivia, U.S. statements have largely mirrored those of the OAS General Secretariat and the European Union (the main donor in Bolivia). On November 12, 2019, the United States and 14 other countries issued a statement rejecting violence, calling for a constitutional solution to the crisis, and urging the designation of a provisional president to call new elections as soon as possible. Regional consensus on Bolivia may erode over whether to recognize Añez as interim president.

Interim Government and 2020 Elections

According to the Bolivian constitution, the interim government has a mandate to convene new elections. Some observers have criticized Interim President Añez, formerly a little-known opposition senator, for exceeding that mandate. Añez's past anti-indigenous political rhetoric and conservative cabinet, which has only one indigenous member, raised concerns among some of Bolivia's indigenous population, which became empowered under Morales. Añez also reversed several MAS foreign policy stances; she expelled Cuban officials (including doctors), recognized Interim President Juan Guaidó of Venezuela, and sent an ambassador to the United States.

The MAS-led Congress initially refused to accept Añez's government, and many MAS supporters protested. Añez issued a decree giving the military permission to participate in crowd-control efforts and immunity from certain prosecutions for doing so, as long as it used only proportional force and respected human rights. The Inter-American Commission of Human Rights issued a report documenting 36 deaths and 400 injuries that occurred from November 8 to November 27, 2019, including two massacres involving state forces. The interim government rejected those findings, accusing "subversives" of orchestrating the protests. Protests died down after passage of the November 23 electoral law and Añez's November 24 revocation of the military decree, but they could escalate again, as prosecutors have issued an arrest warrant for Morales on charges of terrorism and sedition.

Observers praised the November election law as a step toward new elections. A new electoral tribunal is in the process of being appointed. The electoral body has 120 days to convene a first-round election, followed by a second round if necessary. Likely candidates include Carlos Mesa and Luis Camacho, but it remains unclear who will stand for the MAS. Bolivia's interim government has requested significant election-related assistance.

U.S. Concerns

The United States remains concerned about the political volatility in Bolivia, but its role in supporting a return to democracy may be limited. Bolivia-U.S. relations were tense following the 2008 ousting of the U.S. ambassador, and bilateral assistance to the country ended in 2013, after Bolivia expelled a U.S. Agency for International Development mission.

U.S. statements have sometimes mirrored those of the OAS General Secretariat and the European Union (the main donor in Bolivia) but also have praised the Añez government, which the U.S. recognizes, for expelling Cuban officials and recognizing Venezuela's Guaidó government. The Department of State supported the OAS election observation and audit efforts. The United States and 25 other countries issued a November statement to the OAS rejecting violence and calling for new elections as soon as possible. A December 9 statement by Secretary of State Pompeo also called for a focus on convening new elections. Regional consensus has eroded somewhat over the Añez government's crackdown on protesters and efforts to punish Morales and his allies. On December 18, 2019, the OAS Permanent Council narrowly approved a resolution rejecting "racist violence" in Bolivia.

The situation in Bolivia has generated some concern in Congress. S.Res. 447, reported by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in December 2019, supports the prompt convening of new elections.