Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Changes from October 24, 2019 to April 13, 2023

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Safety of Dams in the United States

- Dams by the Numbers

- Dam Failures and Incidents

- Hazard Potential

- Condition Assessment

- Mitigating Risk

- Rehabilitation and Repair

- Preparedness

- Federal Role and Resources for Dam Safety

- National Dam Safety Program

- Advisory Bodies of the National Dam Safety Program

- Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs

- Progress of the National Dam Safety Program

- Federally Owned Dams

- Inspections, Rehabilitation, and Repair

- Federal Oversight of Nonfederal Dams

- Regulation of Hydropower Dams

- Regulation of Dams Related to Mining

- Regulation of Dams Related to Nuclear Facilities and Materials

- Federal Support for Nonfederal Dams

- FEMA High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program

- NRCS Small Watershed Rehabilitation Program

- USACE Rehabilitation and Inspection Program

- Issues for Congress

- Federal Role

- Federal Funding

- Risk Awareness

Figures

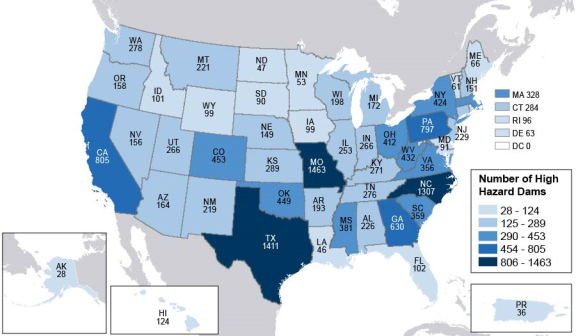

- Figure 1. Model of an Earthen Dam

- Figure 2. National Dam Statistics

- Figure 3. Selected Potential Failure Modes of Dams

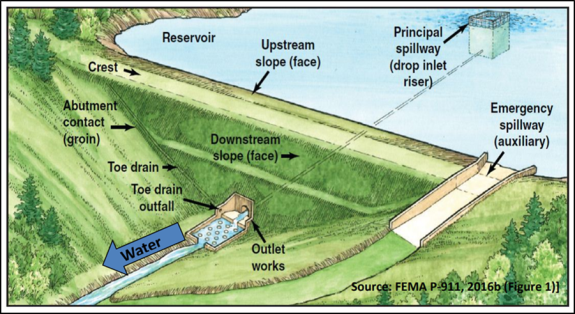

- Figure 4. High Hazard Dams in States and Territories

- Figure 5. Illustration of a Potential Inundation Map Due to Failure of Lake Oroville's Main Dam

- Figure 6. Authorization Levels and Appropriations for the National Dam Safety Program

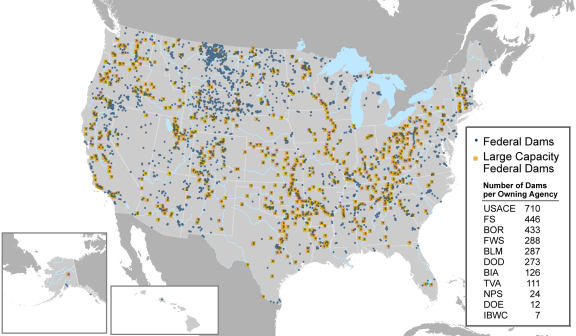

- Figure 7. Location of Federal Dams and Number of Dams Owned per Agency

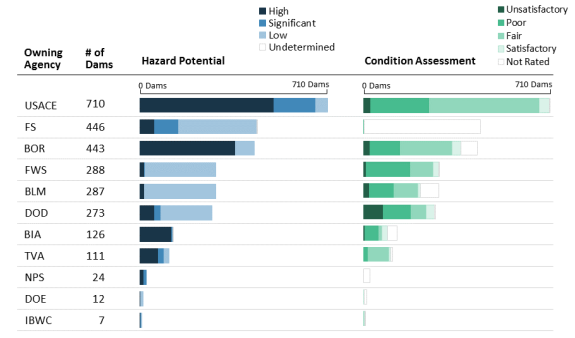

- Figure 8. Hazard Potential and Condition Assessment of Federally Owned Dams

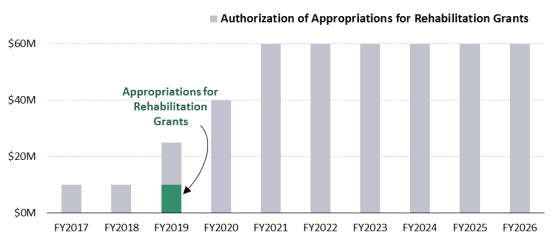

- Figure 9. Authorization and Appropriations for FEMA's High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program

Summary

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

April 13, 2023

Dams provide various services, including flood control, hydroelectric power, recreation, navigation, and water supply, but they require maintenance, and sometimes rehabilitation and

Anna E. Normand

repair, to ensure public and economic safety. Dam failure or incidents can endanger lives and

Analyst in Natural

property, as well as result in loss of services provided by the dam. Federal government agencies

Resources Policy

reported owning 3% of the more than 9091,000 dams listed in the National Inventory of Dams

(NID), including some of the largest dams in the United States. (Thousands more dams fall outside the definition for NID inclusion.) The majority of NID-listed dams are owned by private

entities, nonfederal governments, and public utilities. Although states have regulatory authority for over 6971% of NID-listed dams, the federal government plays a key role in dam safety policies for both federal and nonfederal dams.

Congress has expressed interest in dam safety over several decades, often prompted by critical events such as the 2017 near failure of Oroville Dam'’s spillway in California and the 2020 failure of two hydropower dams in Michigan. Dam failures in the 1970s that resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars of property damage spurred Congress and the executive branch to establish the NID, the National Dam Safety Program (NDSP), and other federal activities regarding dams. These programs and activities have increased safety inspections, emergency planning, and dam rehabilitation, and repair. Since the late 1990s, some federal agencyand state dam safety programs have shifted from a standards-based approach to a risk-management approach. A risk-management approach seeks to mitigate failure of dams and related structures through inspection programs,by conducting comprehensive inspections, enacting risk reduction measures, and prioritizing rehabilitation and repair, and it prioritizes of structures whose failure would pose the greatest threat to life and property.

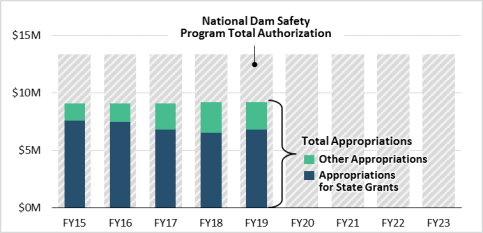

Responsibility for dam safety is distributed among federal agencies, nonfederal agencies, and private dam owners. The Federal Emergency Management Agency'’s (FEMA'’s) NDSP facilitates collaboration among these stakeholders. The National Dam Safety Program Act, as amended (Section 215 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996; P.L. 104-303; 33 U.S.C. §§467f33 U.S.C. §§467 et seq.), authorizes the NDSP at $13.4 million annually. In FY2019, Congress appropriated $9.2 million for the program, which provided training and $6.8 million in state grants, among other activities.

through FY2023. The federal government is directly responsible for maintaining the safety of federally owned dams. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the Department of the Interior'sand the Bureau of Reclamation own 42% of federal dams, including many large dams. The remaining federal dams are owned by the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of Defense, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Tennessee Valley Authority, Department of Energy, and International Boundary and Water Commission, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Congress has provided various authorities for these agencies to conduct dam safety activities, rehabilitation, and repair.

Congress also has enacted legislation authorizing the federal government to regulate or rehabilitate and repair certain nonfederal dams. A number ofOther federal agencies regulate dams associated with hydropower projects, mining activities, and nuclear facilities and materials. Selected nonfederal dams may be eligible for rehabilitation and repair assistance from the Natural Resources Conservation Service, USACE, and FEMA. For example, in 2016, the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322) authorized FEMA to administer a high hazard dam rehabilitation grant program to provide funding assistance for the repair, removal, or rehabilitation of certain nonfederal dams.

Congress may consider how to address the structural integrity of dam infrastructure and mitigate the risk of dam safety incidents, either within a broader infrastructure investment effort or as an exclusive area of interest. Congress may reexamine the federal role for dam safety, while considering that most of the nation's dams are nonfederal. Congress may reevaluate the level and allocation of appropriations to federal dam safety programs, rehabilitation and repair for federal dams, and financial assistance for nonfederal dam safety programs and dams. In addition, Congress may maintain or amend policies for disclosure of dam safety information when considering the federal role in both providing dam safety risk and response information to the public while also maintaining security of these structures.

Introduction

Dams may provide flood control, hydroelectric power, recreation, navigation, and water supply. Dams also entail financial costs for construction, operation and maintenance (O&M), rehabilitation (i.e., bringing a dam up to current safety standards), and repair, and they often result in environmental change (e.g., alteration of riverine habitat).1 Federal government agencies reported owning 3% of the more than 90certain agency programs which are described further in the CRS Report R47383, Federal Assistance for Nonfederal Dam Safety.

Congress may consider oversight and legislation relating to dam safety in the larger framework of infrastructure improvements and risk management, or as an exclusive area of interest. Some of these issues are related to many of the nation’s dams and the federal agencies involved in their dam safety activities, while others are focused on specific dams or specific federal agencies. Selected issues include the following:

Federal agency effectiveness in addressing dam safety for federal and nonfederal dams, including implementing appropriations (e.g., recent influx of funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act [P.L. 117-58]) and determining the sufficient amount of future appropriations to provide for dam safety activities Whether, and if so how, to incentivize and support federal and nonfederal agencies and dam owners to incorporate risk (e.g., risk-informed decisionmaking) in their dam safety practices and how effective these agency practices are at addressing the risk for communities surrounding and downstream of dams Oversight of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s mandate to update probable maximum precipitation study methods to incorporate future climate conditions and of how federal and state agencies may use these methods to inform dam regulations and design Tradeoffs between disclosing dam risk information for public awareness versus preventing individuals or groups seeking to compromise dams and their operating infrastructure for malicious purposes, including through cybersecurity attacks, from gaining this knowledge, and how to reduce the vulnerability of dams and their operating infrastructure from such potential attacks that could compromise dam safety.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 33 link to page 34 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 37 link to page 38 link to page 40 link to page 42 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 13 link to page 17 link to page 24 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 34 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Safety of Dams in the United States ................................................................................................ 2

Dams by the Numbers ............................................................................................................... 2 Dam Failures and Incidents ....................................................................................................... 5 Hazard Potential ........................................................................................................................ 7 Risk Management...................................................................................................................... 9

Rehabilitation and Repair ................................................................................................. 12 Preparedness ..................................................................................................................... 12

Federal Role and Resources for Dam Safety ................................................................................. 14

National Dam Safety Program ................................................................................................ 16

Advisory Bodies of the National Dam Safety Program .................................................... 17 Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs ........................................................................ 17 National Dam Safety Program Reporting ......................................................................... 18

Federally Owned Dams ........................................................................................................... 18 Federal Oversight of Nonfederal Dams .................................................................................. 24

Regulation of Hydropower Dams ..................................................................................... 25 Regulation of Dams Related to Mining ............................................................................ 27 Regulation of Dams Related to Nuclear Facilities and Materials ..................................... 28

Federal Support for Nonfederal Dams .................................................................................... 29

Issues for Congress ........................................................................................................................ 30

Federal Role and Funding for Dam Safety Activities ............................................................. 30

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act ............................................................................. 31

Adoption of Risk-Informed Decisionmaking .......................................................................... 33

Incorporating Future Conditions for Risk Management ................................................... 34

Dam Public Awareness and Security Issues ............................................................................ 36

Efforts to Address Cybersecurity Risks ............................................................................ 38

Figures Figure 1. Illustration of an Earthen Dam ......................................................................................... 3 Figure 2. National Dam Statistics .................................................................................................... 4 Figure 3. Selected Potential Failure Modes of Dams ...................................................................... 5 Figure 4. High Hazard Dams in States and Territories .................................................................... 9 Figure 5. USACE Potential Flood Inundation Map for Isabella Dam ........................................... 13 Figure 6. Location of Federal Dams and Number of Dams Owned per Agency ........................... 20

Tables Table 1. Hazard Potential of Dams in the United States.................................................................. 8 Table 2. Condition Assessment of Nonfederal Dams in the United States .................................... 10 Table 3. Summary of Dam Safety Rating Systems for USACE (DSAC) and Bureau of

Reclamation (DSPR) ................................................................................................................... 11

Table 4.Selected Federal Programs That May Support Nonfederal Dam Safety Projects ............. 30

Congressional Research Service

link to page 36 link to page 44 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Table 5.Selected IIJA Funding for Dam Safety Activities ............................................................. 32

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 40

Congressional Research Service

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Introduction Dams may be used to provide flood control, navigation, drinking water, hydroelectric power, irrigation, recreation, fish and wildlife management, and/or waste management benefits. Construction of dams often causes environmental change (e.g., alteration of riverine habitat). Owning a dam also may require financial expenditures for operation and maintenance, rehabilitation (i.e., bringing a dam up to current safety standards), and repair. Federal agencies reported owning 3% of the more than 91,000 dams in the National Inventory of Dams (NID), including some of the country'’s largest dams (e.g., the Bureau of Reclamation'’s Hoover Dam in Nevada is 730 feet tall with storage capacity of over 30 million acre-feet of water).21 Most dams in the United States are owned by private entities, state or local governments, or public utilities.

Dams may pose a potential safety threat to populations living downstream of dams and populations surrounding associated reservoirs. As dams age, they can deteriorate, which also may pose a potential safety threat. The risks of dam deterioration may be amplified by lack of maintenance, misoperation, development in surrounding areas, natural hazards (e.g., weather and seismic activity), and security threats. Structural failure of dams

Dam failure and incidents—episodes that, without intervention, likely would have resulted in dam failure—may threaten public safety, local and regional economies, and the environment, as well as cause; they also may result in the loss of services provided by a dam.

In recent years, several dam safety incidents have highlighted the public safety risks posed by the failure of dams and related facilities. From 2015 to 2018, over 100 dams breached in North Carolina and South Carolina due to record flooding.3 In 2017, the near failure of Oroville Dam's spillway in California resulted in a precautionary evacuation of approximately 200,000 people and more than $1.1 billion in emergency response and repair.4 In 2018, California began to expedite inspections of dams and associated spillway structures.5

2 Dams can deteriorate as they age, which may increase the risk of failures and incidents and thereby may increase the potential safety threat.3 Lack of maintenance and misoperation may amplify dam deterioration. Development in areas surrounding dams and their reservoirs may amplify the risks associated with dam deterioration. Security threats, such as cybersecurity attacks that could alter dam operations, are also a concern for dam safety. Seismic events, floods, and wildfire and associated debris flows also may impact dams. In recent years, several dam safety incidents have highlighted the public safety risks posed by the failure of dams and related facilities.

Congress has expressed an interest in dam safety over several decades, often prompted by destructive events. Dam failures in the 1970s resultingthat resulted in the loss of life and billions of dollars in property damage prompted Congress and the executive branch to establish the NID, the National Dam Safety Program (NDSP), and other federal activities related to dam safety.6 4 Following terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the federal government focused on dam security and the potential for acts of terrorism at major dam sites.75 As dams age and the population density near many dams increases, attention has turned to mitigating dam the risk of dam

1 Federal agencies self-report dam ownership to the National Inventory of Dams (NID). NID data in this report were assessed on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023. Federal agencies reported owning 2,825 dams with some dams owned by multiple federal agencies. One acre-foot of water is the amount of water that will cover an acre of land to a depth of one foot, or approximately 326,000 gallons.

2 Dam incidents may include overtopping, spillway malfunction or failure, and piping (i.e., internal erosion caused by seepage), among others. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), The National Dam Safety Program, Biennial Report to the United States Congress, Fiscal Years 2018-2019, FEMA P-2189, November 2022, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_ndsp-report-congress-fy18-fy19.pdf.

3 Many dams are built for an intended operational lifespan of 50 years. Dams may continue to operate for their purpose after the 50-year period and may benefit from rehabilitation to expand their operational lifespan and address current safety standards.

4 Failure of a private mine tailings dam at Buffalo Creek, WV, in 1972, flooded a 16-mile valley and killed 125 people; Bureau of Reclamation’s Teton Dam, ID, failed in 1976, killing 11 people and causing $1 billion in property damage; and the private Kelley Barnes Dam, GA, failed in 1977, killing 39 people and causing $2.8 million in damage. FEMA, The National Dam Safety Program, Biennial Report to the United States Congress, Fiscal Years 2016-2017, May 2019, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/national-dam-safety_biennial-report-2016-2017.pdf. Hereinafter FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017.

5 FEMA, Dam Safety and Security in the United States: A Progress Report on the National Dam Safety Program in Fiscal Years 2002 and 2003, December 2003, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/2002-2003-progress-report_dam-safety.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 11 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

failure through dam inspection programs, rehabilitation, and repair, in addition to preventing and preparing for emergencies.8

6

This report provides an overview of dam safety and associated activities in the United States, highlighting the federal role in dam safety. The primary federal agencies involved in these activities include the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The report also discusses potential issues for Congress, such as the federal role in and funding for dam safety activities; adoption of risk-informed decisionmaking for dam safety; and the federal role for nonfederal dam safety; federal funding for dam safety programs, rehabilitation, and repair; and public awareness of dam safety risks and security issues. The report does not discuss in detail emergency response fromto a dam incident, dam building and removal policies, or state dam safety programs.

Safety of Dams in the United States

Dam safety generally focuses on preventing dam failure and incidents—episodes that, without intervention, likely would have resulted in dam failure. Challenges to . Challenges to maintaining dam safety include aging and inadequately constructed dams, frequent or severe floods (for instance, due to climate change), misoperation of dams, and dam security.97 The risks associated with dam misoperation and failure also may increase as populations and development encroach on the areas upstream and downstream of some dams.108 Safe operation and proper maintenance of dams and associated structures is fundamental for dam safety. In addition, routine inspections by dam owners and regulators determine a dam'’s hazard potential (see "“Hazard Potential" below), condition (see "Condition Assessment",” below), and possible needs for rehabilitation and repair.11

9 Dams by the Numbers

The USACE maintains the NID, a database of dams in the United States, is maintained by USACE.12 For the purposes of inclusion in the NID, a dam is defined as any.10 For a dam to be included in the NID, it must be an artificial barrier that has the ability to impound water, wastewater, or any liquid-borne material, for the purpose of storage or control of water that (1) is at least 25 feet in height with a storage capacity of more than 15 acre-feet, (2) is greater than 6 feet in height with a storage capacity of at least 50 acre-feet, or (3) poses a significant threat to human life or property should it fail (i.e., high or significant hazard dams).1311 Thousands of dams do not meet these criteria; therefore, they are not included in the NID.

6 FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017; National Research Council (NRC), Dam and Levee Safety and Community Resilience: A Vision for Future Practice, 2012, at https://doi.org/10.17226/13393. Hereinafter National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety.

7 Michelle Ho et al., “The Future Role of Dams in the United States of America,” Water Resources Research, vol. 53, no. 2 (2017), at https://doi.org/10.1002/2016WR019905.

8 FEMA, Risk Exposure and Residual Risk Related to Dams, 2017, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/ta2-risk_exposure_residual_risk_related_dams.pdf. Hereinafter FEMA, Risk Exposure.

9 Hazard potential reflects the amount and type of damage that a failure would cause. FEMA, Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety Risk Management, FEMA P-1025, 2015, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_dam-safety_risk-management_P-1025.pdf.

10 Online NID data are used throughout this report unless otherwise specified. State and federal agencies self-report dam information to the NID. In this report, the number of dams owned by federal agencies are based on federal agency reporting to the NID. State agencies also reported additional dams owned by the federal government, though CRS could not confirm ownership of these dams. The NID can be accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil. Hereinafter NID, assessed on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023.

11 33 U.S.C. §467.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 7

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

National Inventory of Dams

After several dam failures in the early 1970s, Congress authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to inventory the nation |

.

The most common type of dam is an earthen dam (seesee Figure 1), which is made from natural soil or rock or from , rock, or mining waste materials. Other damsdam types include concrete dams, tailings dams (i.e., dams that store mining byproducts), overflow dams (i.e., dams regulating downstream flow), and dikes (i.e., dams constructed at a low point of a reservoir of water).1412 This report does not cover levees, which are manmade structures designed to control water movement along a landscape.

Figure 1. |

|

Source: FEMA, Pocket Safety Guide for Dams and Impoundments, 2016, at

|

The nation's dams were

12 The United States Society on Dams, “Types of Dams,” at https://www.ussdams.org/dam-levee-education/overview/types-of-dams/.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 8

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

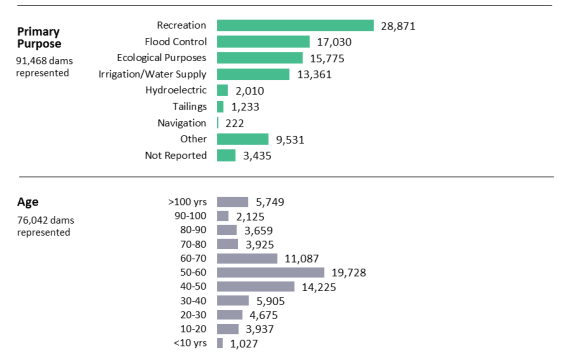

The nation’s dams have been constructed for various purposes: recreation, flood control, ecological management (e.g., fisheries management), irrigation and water supply, hydroelectrichydroelectricity, mining, navigation, and others (see Figure 2). A dam. Dams may serve multiple purposes. Although some dams were built before 1900s (e.g., ~2,300 of the dams in the NID), nearly half of dams in the NID were built between 1950 and 1980 (over 43,000 NID dams).13 After this period, construction of new dams slowed (e.g., the NID lists a little over 4,700 dams built since 2000). Dams are built to the engineering and construction standards and regulations that apply at the time of their construction. As a result, some damspurposes. Dams were built to engineering and construction standards and regulations corresponding to the time of their construction. Over half of the dams with age reported in the NID were built over fifty years ago.15 Some dams, including older dams, may not meet current dam safety standards, which have evolved over time as scientific data and engineering have improved over time.16

|

|

improved.14 These dams may not operate properly or may even fail from certain flooding and seismic events that are now known to be possible at the site based on improved understanding of weather and flood data, such as probable maximum flood, and seismic data.

Figure 2. National Dam Statistics

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) with

|

Dam Failures and Incidents

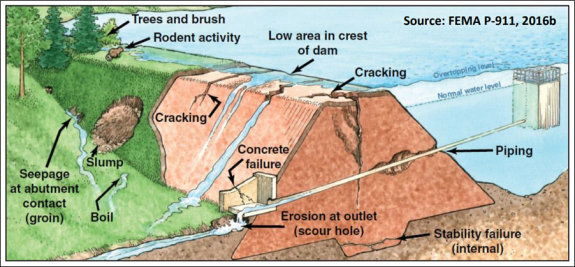

Dam failures and incidents—episodes that, without intervention, likely would have resulted in dam failure—may occur for various reasons. Potential causes include floods that may exceed design capacity; faulty design or construction; misoperation or inadequate operation plans; overtopping, with water spilling over the top of the dam; foundation defects, including settlement and slope instability; cracking caused by movements, including seismic activity; inadequate maintenance and upkeep; and piping, when seepage through a dam forms holes in the dam (seesee Figure 3).15

Figure 3).17

Figure 3. Selected Potential Failure Modes of Dams |

|

Source: FEMA, Pocket Safety Guide for Dams and Impoundments, 2016, at https://www.fema.gov/ sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_911_pocket_safety_guide_dams_impoundments_2016.pdf. Notes: The figure is of an earthen dam; other dams may have different potential modes of failure. Some potential failure modes are not |

Engineers and organizations have documented dam failure in an ad hoc manner for decades.18 16 Some report over 1,600 dam failures resulting in approximately 3,500 casualties in the United States since the middle of the 19th19th century, although these numbers are difficult to confirm.1917 Between 2000 and 2020, states reported 270 failures and 581 non-failure dam safety incidents.18

A number of more recent dam incident and failure events have led to increased attention on the condition of dams and the federal role in dam safety. Many failures are of spillways and small dams, which may result in limited flooding and downstream impact compared to large dam failures. Flooding that occurs when a dam is breached may not result in life safety consequences 15 National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety. 16 Personal correspondence between CRS and ASDSO, June 13, 2019. National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety.

17 National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety; personal correspondence between CRS and ASDSO, June 13, 2019. Although these sources provide information on dam failures and casualties, this information is self-reported.

18 A nonfailure incident is an incident at a dam that will not, by itself, lead to a failure but that requires investigation and notification of internal and/or external personnel. The failure and nonfailure incident estimate may be uncertain. Because reporting is voluntary, few private or local dams are included. Nonfailure events also may represent a drowning or injury not directly arising from a dam with structural deficiencies. ASDSO, “Roadmap to Reducing Dam Safety Risks,” at https://www.damsafety.org/Roadmap.

Congressional Research Service

5

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

failures. Flooding that occurs when a dam is breached may not result in life safety consequences or significant property damage.2019 Still, some dam failures have resulted in notable disasters in the United States.20 Some notable dam failures and incidents since 2000 include the following:

In May 2020, following several days of heavy rain, two dams failed in Michigan,

resulting in widespread flooding andUnited States.21

Between 2000 and 2019, states reported 294 failures and 537 nonfailure dam safety incidents.22 Recent events—including the evacuation of approximately 200,000 people in California in 2017 due to structural deficiencies of the spillway at Oroville Dam—have led to increased attention on the condition of dams and the federal role in dam safety.23 From 2015 to 2018, extreme storms (including Hurricane Matthew) and subsequent flooding resulted in over 100 dam breaches in North Carolina and South Carolina.24 Floods resulting from hurricanes in 2017 also 10,000 downstream residents.21

In March 2019, the latest dam failure fatality occurred when a hydropower dam

in Nebraska failed because of an icy flood. There was no formal emergency action plan, because the dam was not classified as a high hazard potential dam.22. High hazard potential means the loss of at least one life is probable from a dam failure.

In 2017, the near failure of Oroville Dam’s spillway in California resulted in a

precautionary evacuation of approximately 200,000 people and more than $1.1 billion in emergency response and repair.23

From 2015 to 2018, over 100 dams breached in North Carolina and South

Carolina due to record flooding.24

Floods resulting from hurricanes in 2017 filled reservoirs of dams to record

filled reservoirs of dams to record levels in some regions: —for example, USACE'’s Addicks and Barker Dams in the Houston, TX, area; the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority'’s Guajataca Dam in Puerto Rico; and USACE'’s Herbert Hoover Dike in Florida.25 25

The March 2006 failure of the private KalokoKa Loko Dam in Hawaii killed seven people, and the

people.26

The 2003 failure of the Upper Peninsula Power Company'’s Silver Lake Dam in

Michigan caused more than $100 million in damage.26

Oroville Dam, CA

dam incident inundation maps.

Sources: Independent Forensic Team Report, Oroville Dam Spillway Incident, 2018, at https://damsafety.org/ Notes: |

Hazard Potential

Federal guidelines set out a hazard potential rating to quantify the potential harm associated with a dam'’s failure or misoperation.2728 As described in Table 1, thethe three hazard ratings (low, significant, and high) do not indicate the likelihood of failure; instead, the ratings reflect the amount and type of damage that a failure would cause. Figure 4 depicts the number of dams

28 FEMA, Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety: Hazard Potential Classification System for Dams, 2004, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1516-20490-7951/fema-333.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

7

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

depicts the number of dams listed in the NID that are classified as high hazard in each state; 6560% of dams in the NID are classified as low hazard. From 2000 to 20182023, thousands of dams were reclassified, increasing the number of high hazard dams from 9,921 to 15,629.2814,934.29 According to FEMA, the primary factor increasing dams'’ hazard potential is hazard creep—development upstream and downstream of a dam, especially in the dam failure inundation zone (i.e., downstream areas that would be inundated by water from a possible dam failure).29, that increases the potential consequences of a dam failure.30 Reclassification from low hazard potential to high or significant hazard potential may trigger more stringent requirements by regulatory agencies, such as increased spillway capacity, structural improvements, more frequent inspections, and creating or updating an emergency action plan (EAP).3031 Some of these requirements may be process and procedure based, and others may require structural changes for existing facilities.

Table 1. Hazard Potential of Dams in the United States

Number

Percent of

of NID

NID Dams

Hazard Potential

Result of Failure or Misoperation

Dams

High Hazard

Loss of at least one life is probable

14,934

16%

Table 1. Hazard Potential of Dams in the United States

|

Hazard Potential |

Result of Failure or Misoperation |

Number of Dams |

Percent of NID Dams |

|

High Hazard |

|

15,629 |

17% |

|

Significant Hazard |

|

11,354 |

12% |

|

Low Hazard |

|

59,679 |

65% |

|

Undetermined |

|

4,806 |

5% |

Sources: FEMA, Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety: Hazard Potential Classification System for Dams, 2004, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1516-20490-7951/fema-333.pdf; and 2018 National Inventory of Dams (NID) data availableaccessed at https at http://nid.sec.usace.army.mil/.

on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023. Notes: Low hazard dams are not included in the NID if they are less than 25 feet in height with a storage capacity of 15 acre-feet or less, or are 6 feet or less in height with a storage capacity of less than 50 acre-feet.

Condition Assessment

The NID includes condition assessments—assessments of relative dam deficiencies determined from inspections—as reported by federal and . The NID still includes condition assessments as reported by state agencies (see Table 2).31 Of the 15,629 high hazard potential dams in the 2018 NID, 63 and some federal agencies.34 Of the 13,669 high hazard 32 FEMA, “Dam Operation and Maintenance,” at https://www.fema.gov/dam-operation-and-maintenance. 33 FEMA, Risk Reduction Measures for Dams, 2018, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fact-sheet_risk-reduction-measures-dams.pdf. Hereinafter FEMA, Risk Reduction.

34 Condition is an assessment of any potential dam deficiencies determined from inspections. States and federal agencies may have additional definitions and rating applications that are used to classify dams, which may vary from state to state as well as among federal agencies. ASCE, Infrastructure Report Card; FEMA, The National Dam Safety

Congressional Research Service

9

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

potential nonfederal dams in the NID as of January 2023, 61% had satisfactory or fair condition assessment, 15% had a poor or unsatisfactory condition assessment, and 2224% were not rated. 35 For dams rated as poor and unsatisfactory, federal agencies and state regulatory agencies may take actions to reduce risk, such as reservoir drawdowns, and may convey updated risk and response procedures to stakeholders.32

36

Table 2. Condition Assessment of Nonfederal Dams in the United States

High

Significant

Low

Undetermined

Condition

Hazard

Hazard

Hazard

Hazard

Ratings

Description of Condition Rating

Dams

Dams

Dams

Dams

Satisfactory

No existing or potential dam

4,515

2,428

4,308

334

safety deficiencies are recognized.

Acceptable performance is expected under all conditions in accordance with the minimum applicable regulatory criteria or tolerable risk guidelines.

Fair

No existing dam safety deficiencies

3,881

2,315

4,234

1,038

are recognized for normal operatingDams in the United States

|

Condition Ratings |

Description of Condition Rating |

High Hazard Dams |

Significant Hazard Dams |

Low Hazard Dams |

|

|

Satisfactory |

|

5,202 |

2,527 |

4,789 |

7 |

|

Fair |

|

4,645 |

2,451 |

4,304 |

10 |

|

Poor |

|

2,126 |

1,435 |

3,437 |

13 |

|

Unsatisfactory |

|

258 |

119 |

323 |

2 |

|

Not Rated |

|

3,398 |

4,822 |

46,826 |

4,774 |

Source: 2018 NID data and FEMA, National Dam Safety Program.

has been inspected but not rated.

Source: National Inventory of Dams (NID) data accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023; and USACE, National Inventory of Dams, Data Dictionary, August 2022, at https://nid.usace.army.mil/#/documents. Notes: A dam safety deficiency is an unacceptable dam condition that may affect the safety of the dam either in the near term or in the future.

Mitigating Risk

In the context of dam safety, risk is comprised of three parts:33

- the likelihood of a triggering event (e.g., flood or earthquake),

-

Program: Biennial Report to the United States Congress, Fiscal Years 2012-2013, 2014, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1467048771223-c5323440700a175565a2c0c9d604f9e3/DamSafetyUnitedStatesAug2014.pdf.

35 NID data accessed on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023. 36 National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 15 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Some federal agencies (e.g., Reclamation, USACE, FERC) have since transitioned from this solely standards-based approach for their dam safety programs to a portfolio-wide risk-informed decisionmaking (RIDM) management approach to dam safety. These and other federal agencies working toward adopting a RIDM management approach no longer report condition assessment to the NID. Instead, some of these agencies use rating systems, such as the ones in Table 3. According to FEMA, “a risk-management approach seeks to improve the resilience of dam infrastructure and mitigate failure of dams and related structures through inspection programs, risk reduction measures, and rehabilitation and repair.”37 In the context of dam safety, risk comprises three parts:38

the likelihood of a triggering event (e.g., flood or earthquake), the likelihood of a dam safety deficiency resulting in adverse structural response

the likelihood of a dam safety deficiency resulting in adverse structural response(e.g., dam failure or spillway damage), and -

the magnitude of potential consequences resulting from the adverse event (e.g.,

loss of life or economic damages).

Preventing dam failure involves proper location, design, and construction of structures, and regular technical inspections, O&M, and rehabilitation and repair of existing structures.34 Preparing and responding to dam safety concerns may involve community development planning, emergency preparation, and stakeholder awareness.35 Dam safety policies may address risk by focusing on preventing dam failure while preparing for the consequences if failure occurs.

Evaluating and reducing risk requires a framework that explicitly evaluates the level of risk if no action is taken, including for all modes of failure (e.g., seepage of water and sediment through a dam), and recognizes the monetary and nonmonetary costs and benefits of reducing risks when making decisions. The RIDM framework comprises risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication. The RIDM assessment process aims to inform better decisionmaking and to enable more effective use of limited resources. Some state dam safety agencies (e.g., Colorado) also are working to incorporating a risk management approach.39

Table 3. Summary of Dam Safety Rating Systems for USACE (DSAC) and Bureau of

Reclamation (DSPR)

USACE Dam Safety Action Classification

Reclamation Dam Safety Priority Ratings

Ratings (DSAC)

(DSPR)

1

Very High Urgency—almost certain to fail

Immediate Priority—active failure mode or

immediately to a few years under normal operations

extremely high likelihood of failure requiring

or the combination of consequences and failure

immediate actions to reduce risk.

probability is extremely high.

2

High Urgency—likelihood of failure during normal

Urgent Priority—potential failure modes are

operations or a consequence of an event is too high

judged to present various serious risks, which justify

to assure public safety or the combination of

urgency to reduce risk.

consequences and failure probability is very high.

3

Moderate Urgency—dam may have issues where

Moderate to High Priority—potential failure

the incremental risk is moderate and the level of life-

modes appear to be dam safety deficiencies that

risk is unacceptable except in unusual circumstances.

propose a significant risk of failure, and actions are needed to better define risks or to reduce risks.

4

Low Urgency—dam is inadequate but with low

Low to Medium Priority—potential failure modes

risk, such that the combination of consequences and

appear to indicate a potential concern but do not

failure probability is low. Dam may not meet all

indicate a pressing need for action.

USACE engineering guidelines.

37 FEMA, The National Dam Safety Program: Biennial Report to the United States Congress, Fiscal Years 2018-2019, November 2022, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_ndsp-report-congress-fy18-fy19.pdf.

38 Personal correspondence between CRS and FEMA, June 26, 2019. 39 State of Colorado, Department of Natural Resources, Guidelines for Comprehensive Dam Safety Evaluation (CDSE) Risk Assessments & Risk Informed Decision Making (RIDM), March 8, 2021, at https://dnrweblink.state.co.us/dwr/ElectronicFile.aspx?docid=3566811&dbid=0.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 17 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

USACE Dam Safety Action Classification

Reclamation Dam Safety Priority Ratings

Ratings (DSAC)

(DSPR)

5

Normal—considered safe, meeting all agency

Low Priority—potential failure modes do not

guidelines, with tolerable residual risk.

appear to present significant risk, and there are no apparent dam safety deficiencies.

Sources: Bureau of Reclamation, Dam Safety Public Protection Guidelines: A Risk Framework to Support Dam Safety Decision-Making, 2011, at https://www.usbr.gov/ssle/damsafety/documents/PPG201108.pdf. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Safety of Dams – Policy and Procedures, Engineering Regulation 1110-2-1156 at https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerRegulations/ER_1110-2-1156.pdf.

Rehabilitation and Repair

Rehabilitation and Repair

Rehabilitation typically consists of bringing a dam up to current safety standards (e.g., increasing spillway capacity, installing modern gates, addressing major structural deficiencies), and repair addresses damage to a structure. Rehabilitation and repair are different from day-to-day O&M. According to a 2019 study by ASDSO, the combined total cost to rehabilitate the nonfederal and federal dams in the NID would exceed $70 billion.36 The study projected that the cost to rehabilitate high hazard potential dams in the NID would be approximately $3 billion for federal dams and $19 billion for nonfederal dams.37In 2022, the Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimated that $75.7 billion was needed to rehabilitate nonfederal dams; of that amount, $24.0 billion was needed for high hazard potential nonfederal dams.40 Federal agencies report various funding estimates needed for rehabilitation and repair of dam that they manage. Some stakeholders project that funding requirements for dam safety rehabilitation and repair will continue to grow as infrastructure ages, risk awareness progresses, and design standards evolve.38

Preparedness

41

Preparedness

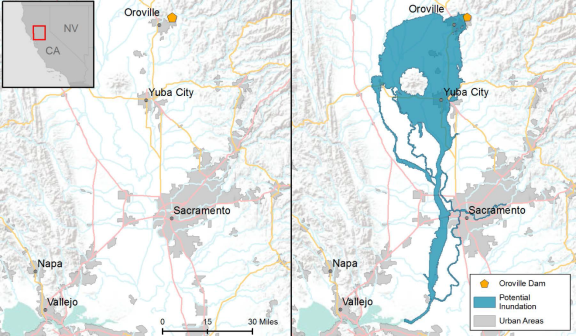

Dam safety processes and products—such as emergency action plans (EAPs)EAPs and inundation maps—may support informed decisionmaking to reduce the risk and consequences of dam failures and incidents.3942 An EAP is a formal document that identifies potential emergency conditions at a dam and specifies preplanned actions to minimize property damage and loss of life.4043 EAPs identify the actions and responsibilities of different parties in the event of an emergency, such as the procedures to issuefor issuing early warning and notification messages to emergency management authorities. EAPs also contain inundation maps to show emergency management authorities the critical areas for action in case of an emergency (see Figure 5 for a map illustration of potential inundation areas due to a hypothetical dam breach).44dam failure).41 Many agencies that are responsible for dam oversight require or encourage dam owners to develop EAPs and often oversee emergency response simulations (i.e., tabletop exercises) and field exercises.4245 Requirements for EAPs often focus on high hazard dams. In 2018, the percentage of high hazard potential dams in the United States with EAPs was 74% for federally owned dams and 80% for state-regulated dams.43

|

|

|

Some states, such as California, provide flood inundation map information on their own websites.

Federal agencies have developed tools to assist dam owners and regulators, along with emergency managers and communities, to prepare for, monitor, and respond to dam failures and incidents.

FEMA' FEMA’s RiskMAP program provides flood maps, tools to assess the risk from flooding, and planning and outreach support to communities for flood risk mitigation.4448 A RiskMAP project may incorporate the potential risk of dam failure or incidents.FEMA'46 ASDSO, “Roadmap to Reducing Dam Safety Risks,” at https://www.damsafety.org/Roadmap. 47 NID data accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023. 48 FEMA, “Risk Mapping, Assessment and Planning (Risk MAP),” at https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/tools- Congressional Research Service 13 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role FEMA’s Decision Support System for Water Infrastructure Security (DSS- WISE) Lite allows states to conduct dam failure simulations and human consequence assessments.4549 Using DSS-WISE Lite, FEMA conducted emergency dam-break flood simulation and inundation mapping of 36 dams in Puerto Rico during the response to Hurricane Maria in 2017.DamWatch DamWatch is a web-based monitoring and informational tool for 11,800 nonfederal flood control dams built with assistance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.4650 When these dams experience a critical event (e.g., threatening storm systems), essential personnel are alerted via an electronic medium and can implement EAPs if necessary.-

The U.S. Geological Survey

'’s ShakeCast is a post-earthquake awareness application that notifies responsible parties of dams about the occurrence of a potentially damaging earthquake and its potential impact at dam locations.4751 The responsible parties may use the information to prioritize response, inspection, rehabilitation, and repair of potentially affected dams.

Federal Role and Resources for Dam Safety

In addition to owning dams, the federal government is involved in multiple areas of dam safety through legislative and executive actions. Following USACE'’s publication of the NID in 1975 as authorized by P.L. 92-367, the Interagency Committee on Dam Safety—established by President Jimmy Carter through Executive Order 12148—released safety guidelines for dams regulated by federal agencies in 1979.4852 In 1996, the National Dam Safety Program Act (Section 215 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996, as amended; ; P.L. 104-303) ; 33 U.S.C. §§467 et seq.) established the National Dam Safety Program (NDSP), the nation'’s principal dam safety program, under the direction of FEMA. Congress has reauthorized the NDSP four times and enacted other dam safety programs and activities related to federal and nonfederal dams.4953 A chronology of selected federal dam safety actions is provided in the box below.

resources/risk-map.

49 FEMA, DSS-WISETM HCOM: Human Consequences of Dam-Break Floods, at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1593524739829-955771e7e1eed3a8d6a36a5d1e79abf7/DSS-WISE_HCOM_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

50 U.S. Engineering Solutions, “DamWatch,” at https://www.usengineeringsolutions.com/dam-watch/. 51 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), “The USGS ShakeCast System,” at https://www.usgs.gov/news/usgs-shakecast-system.

52 Executive Order 12148, “Federal Emergency Management,” 44 Federal Register 43239, 1979, at https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12148.html. The federal guidelines for dam safety established a basic structure for agencies’ dam safety programs. The guidelines have been updated subsequently. FEMA, Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety, 2004, at https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_dam-safety_P-93.pdf. Hereinafter FEMA, Federal Guidelines.

53 Baecher et al., Review and Evaluation, University of Maryland.

Congressional Research Service

14

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Chronology of Selected Federal Administrative and

Legislative Actions for Dam Safety

1972 An Act to Authorize

dam safety actions is provided in the box below.

Chronology of Selected Federal Administrative and Legislative Actions for Dam Safety

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

10.17226/13393. National Dam Safety Program

The NDSP is a federal program established to facilitate collaboration among the various federal agencies, states, and owners with responsibility for dam safety.5054 The NDSP also provides dam safety information resources and training, conducts research and outreach, and supports state dam safety programs with grant assistance. The NDSP does not mandate uniform standards across dam safety programs.

54 The stated purpose of the NDSP was “to reduce the risks to life and property from dam failure in the United States through the establishment and maintenance of an effective national dam safety program to bring together the expertise and resources of the Federal and non-Federal communities in achieving national dam safety hazard reduction.” FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017. National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety. For information on the National Dam Safety Program (NDSP), see FEMA, “National Dam Safety Program,” at https://www.fema.gov/national-dam-safety-program.

Congressional Research Service

16

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

safety programs. Figure 6 shows authorization of appropriations levels for the NDSP and appropriations for the program, including grant funding distributed to states.

|

|

Source: CRS with funding levels provided from personal correspondence with FEMA on July 10, 2019.

|

Advisory Bodies of the National Dam Safety Program

Advisory Bodies of the National Dam Safety Program

The National Dam Safety Review Board (NDSRB) advises FEMA'’s director on dam safety issues, including the allocation of grants to state dam safety programs. The board consistsis to consist of five representatives appointed from federal agencies, five state dam safety officials, and one representative from the private sector.5155 The Interagency Committee on Dam Safety (ICODS) serves as a forum for coordination of federal efforts to promote dam safety. ICODS is chaired by FEMA and is to include representatives from FERC,FEMA and includes representatives from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC); the International Boundary and Water Commission;Commission, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC);, the Tennessee Valley Authority;, and the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, the Interior (DOI), and Labor (DOL).52

56

Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs

Every state (except Alabama) has established a regulatory program for dam safety, as has Puerto Rico.57 Collectively, these programs have regulatory authority for 71% of the NID dams.58 State dam safety programs typically include safety evaluations of existing dams, review of plans and specifications for dam construction and major repair work, periodic inspections of dams and construction work on new and existing dams, reviews and approval of EAPs required for certain dams,59 and engagement with local officials and dam owners on emergency preparedness activities.60 Funding levels and narrow state statutory authorities may limit the activities of some state dam safety programs.61 In 2021, 15 states had more than seven full-time employees in their dam safety program.62 In addition, some states—Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Vermont, and Wyoming—have not provided regulatory bodies with the authority to require dam owners of high hazard potential dams to develop EAPs.63 However, state budgets, and accordingly staffing 55 33 U.S.C. §467f(f). For more information, see FEMA, “Advisory Committees,” at https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/dam-safety/advisory-committees#review-board.

56 33 U.S.C. §467e. 57 FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017. 58 NID data accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023. States define their own regulatory jurisdiction (the height, volume, and type of dams to be regulated). According to ASDSO, most states follow the NID criteria, but regulatory statutes vary among states. Some states exempt categories of dams from inspection based on the purpose of the impoundment or the owner type. For example, Delaware law exempts dams owned by private individuals and entities; Missouri law exempts all agricultural purpose dams and dams less than 35 feet in height regardless of storage volume and potential hazard; and Texas law exempts privately owned significant hazard and low hazard potential dams storing less than a maximum of 500 acre-feet in counties with population less than 350,000, excluding dams within municipal corporate limits. Personal correspondence between CRS and ASDSO on August 30, 2019.

59 An emergency action plan (EAP) is a formal document that identifies potential emergency conditions at a dam and specifies preplanned actions to minimize property damage and loss of life. EAPs identify the actions and responsibilities of different parties in the event of an emergency, such as the procedures to issue early warning and notification messages to emergency management authorities. EAPs also contain inundation maps to show emergency management authorities the critical areas for action in case of an emergency.

60 FEMA, Model State Dam Safety Program, 2022, at https://damsafety-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/files/FEMA%20316_Model%20State%20Dam%20Safety%20Program_2022.pdf; FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017.

61 ASDSO, “State Performance and Current Issues,” at https://damsafety.org/state-performance. 62 Past recommendations were for one full-time employee for every 20 state-regulated dams. Updated draft guidance to states may provide broader recommendations for staffing needs based on the different types of programs, such as state agencies that perform most dam safety work in-house compared with states that outsource work or require dam owners to hire engineers to perform inspections. Personal correspondence between CRS and ASDSO on October 17, 2022.

63 Regulations for high hazard potential dams vary by state, although FEMA has encouraged requiring EAPs for high hazard potential dams. Personal correspondence between CRS and ASDSO on October 17, 2022. ASDSO, Summary of

Congressional Research Service

17

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

levels, have increased over the past couple decades (e.g., 317 full-time employees in 1999 compared with nearly 455 full-time employees in 2022).64

The National Dam Safety Program Act authorizes state assistance programs under the NDSP. This assistance includes (1) grant assistance to state dam safety programs that are working toward or meeting minimal requirements as established by the National Dam Safety Program Act,65 (2) grants for rehabilitation of high hazard potential dams, and (3) trainings for state inspectors, among other assistance. For more information on NDSP assistance for states, see CRS Report R47383, Federal Assistance for Nonfederal Dam Safety.

Association of State Dam Safety

National Dam Safety Program

Officials

Reporting

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) comprises 3,000 state, federal, and local dam safety

At the end of each odd-numbered fiscal year,

professionals and private sector experts organized to

FEMA is to submit to Congress a report

improve dam safety through research, education, and

describing the NDSP’s status, federal

communication. After its establishment in 1983,

agencies’ progress at implementing the

ASDSO worked with the Federal Emergency

Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety, progress

Management Agency (FEMA) to publish the Model State Dam Safety Program to assist state officials in initiating

achieved in dam safety by states participating

or improving their state programs. The model outlines

in the program, and any recommendations for

the key components of a dam safety program and

legislation or other actions (33 U.S.C.

provides guidance on the development of state

§467h).66 Federal agencies and states provide

programs, including legislative authorities, to minimize

FEMA with annual program performance

risks created by unsafe dams. ASDSO continues to support various elements of the National Dam Safety

assessments on key metrics such as

Program, especial y through training initiatives and

inspections, rehabilitation and repair activities,

outreach to dam owners. The Model Dam Safety

EAPs, staffing, and budgets. USACE provides

Program was most recently updated in 2022. The

summaries and analysis of NID data (e.g.,

Model State Dam Safety Program may be accessed at https://damsafety-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/

inspections and EAPs) to FEMA. FEMA

files/

published The National Dam Safety Program

FEMA%20316_Model%20State%20Dam%20Safety%20Pr

Biennial Report to the United States Congress,

ogram_2022.pdf. For more information on ASDSO, see

Fiscal Years 2018–2019 on November 17,

https://damsafety.org/.

2022.67 As of March 2023, FEMA had not published a biennial report covering subsequent years.

Federally Owned Dams Federally owned dams are dams owned by the federal government that are managed by one or more federal agencies. The federal government is responsible for maintaining dam safety of federally owned dams by performing maintenance, inspections, rehabilitation, and repair work.

State Laws and Regulations on Dam Safety, May 2022, at https://damsafety-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/files/FINAL%20-%202020%20Update%20State%20Laws%20and%20Regulations%20Summary_0.pdf.

64 ASDSO, “Roadmap to Reducing Dam Safety Risks,” at https://www.damsafety.org/Roadmap. 65 The National Dam Safety Program Act, as amended, (Section 215 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996; P.L. 104-303) established 10 criteria that state dam safety programs must meet or be working toward meeting to be eligible for the grant assistance program (33 U.S.C. § 467f).

66 FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017. 67 FEMA, “Dam Safety in the United States: A Progress Report on the National Dam Safety Program,” at https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/dam-safety/progress-report.

Congressional Research Service

18

link to page 24 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs

Association of State Dam Safety Officials

|

Every state (except Alabama) has established a regulatory program for dam safety, as has Puerto Rico.53 Collectively, these programs have regulatory authority for 69% of the NID dams.54 State dam safety programs typically include safety evaluations of existing dams, review of plans and specifications for dam construction and major repair work, periodic inspections of construction work on new and existing dams, reviews and approval of EAPs, and activities with local officials and dam owners for emergency preparedness.55

Funding levels and a lack of state statutory authorities may limit the activities of some state dam safety programs.56 For example, the Model State Dam Safety Program, a guideline for developing state dam safety programs, recommends one full-time employee (FTE) for every 20 dams regulated by the agency. As of 2019, one state—California—meets this target, with 75 employees and 1,246 regulated dams.57 Most state dam safety programs reportedly have from two to seven FTEs.58 In addition, some states—Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Vermont, and Wyoming—do not have the authority to require dam owners of high hazard dams to develop EAPs.59

The National Dam Safety Program Act, as amended (Section 215 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996; P.L. 104-303; 33 U.S.C. §§467f et seq.), authorizes state assistance programs under the NDSP. Two such programs are discussed below (see "FEMA High Hazard Dam Rehabilitation Grant Program" for information about FEMA's dam rehabilitation program initiated in FY2019).

Grant Assistance to State Dam Safety Programs. States working toward or meeting minimal requirements as established by the National Dam Safety Program Act are eligible for assistance grants.60 The objective of these grants is to improve state programs using the Model State Dam Safety Program as a guide. Grant assistance is allocated to state programs via a formula: one-third of funds are distributed equally among states participating in the matching grant program and two-thirds of funds are distributed in proportion to the number of state-regulated dams in the NID for each participating state.61 Grant funding may be used for training, dam inspections, dam safety awareness workshops and outreach materials, identification of dams in need of repair or removal, development and testing of EAPs, permitting activities, and improved coordination with state emergency preparedness officials. For some state dam safety programs, the grant funds support the salaries of FTEs that conduct these activities.62 This money is not available for rehabilitation and repair activities.63 In FY2019, FEMA distributed $6.8 million in dam safety program grants to 49 states and Puerto Rico (ranging from $48,000 to $465,000 per state).64

Training for State Inspectors. At the request of states, FEMA provides technical training to dam safety inspectors.65 The training program is available to all states by request, regardless of state participation in the matching grant program.

Progress of the National Dam Safety Program

At the end of each odd-numbered fiscal year, FEMA is to submit to Congress a report describing the NDSP's status, federal agencies' progress at implementing the Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety, progress achieved in dam safety by states participating in the program, and any recommendations for legislation or other actions (33 U.S.C. § 467h).66 Federal agencies and states provide FEMA with annual program performance assessments on key metrics such as inspections, rehabilitation and repair activities, EAPs, staffing, and budgets. USACE provides summaries and analysis of NID data (e.g., inspections and EAPs) to FEMA.

Some of the metrics for the dam safety program, such as the percentage of state-regulated high hazard potential dams with EAPs and condition assessments, have shown improvement. The percentage of these dams with EAPs increased from 35% in 1999 to 80% in 2018, and condition assessments of these dams increased from 41% in 2009 to 85% in 2018.67 The percentage of state-regulated high hazard potential dams inspected has remained relatively stable during the same period—between 85% to 100% dams inspected based on inspection schedules.68

Federally Owned Dams

The major federal water resource management agencies, USACE and Reclamation, own 42% of federal dams, including many large dams (Figure 7).69 The remaining federal dams typically are smaller dams owned by other agencies, including land management agencies (e.g., Fish and Wildlife Service and the Forest Service), the Department of Defense, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, among others.70 The federal government is responsible for maintaining dam safety of federally owned dams by performing maintenance, inspections, rehabilitation, and repair work. No single agency regulates all federally owned dams; rather, each federal dam is regulated according to the policies and guidance of the individual federal agency that owns the dam.7168 The Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety provides basic guidance for federal agencies'’ dam safety programs.69

According to the NID, in January 2023, federal agencies reported managing 2,825 federal dams, with some dams managed by multiple federal agencies (Figure 6).70 Federally owned dams may be under the jurisdiction of three broad categories of federal agencies:

Agencies that primarily manage water resources—USACE and Reclamation—

manage 42% of federal dams in the NID, including many large dams. Dams managed by these agencies may be located on lands managed by other agencies.

Agencies that manage most federal lands, collectively known as the federal land

management agencies (i.e., the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Forest Service [FS], and National Park Service), manage 39% of federal dams in the NID, which are typically smaller dams.

Agencies that manage the remainder of federal dams, such as the Department of

Defense and the Tennessee Valley Authority.

68 FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017. 69 FEMA, Federal Guidelines. At times, some agencies have received criticism of their dam safety programs in carrying out the Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety. For example, in 2014, the Department of Defense (DOD) Inspector General found that DOD did not have a policy requiring installations to implement a dam safety inspection program consistent with the Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety. Office of the Inspector General, U.S. Department of Defense, DOD Needs Dam Safety Inspection Policy to Enable the Services to Detect Conditions that Could Lead to Dam Failure, U.S. Department of Defense, 2014, at https://media.defense.gov/2019/Aug/22/2002174057/-1/-1/1/DODIG-2015-062.PDF. Hereinafter Inspector General, DOD Needs Dam Safety Inspection Policy.

70 Federal agencies self-report dam management to the NID. Other federal agency documents may list more dams managed by their agencies that are not included in the NID. For this report, dam management data are from the NID unless otherwise noted. NID data accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023.

Congressional Research Service

19

Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

Figure 6. Location of Federal Dams and Number of Dams Owned per Agency

Source: CRS using National Inventory of Dams (NID) data accessed at https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil on January 24, 2023, with data last updated on January 18, 2023.

Notes: No federal dams are in Puerto Rico, and one is in Guamprograms.72

Inspections, Rehabilitation, and Repair

The Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety recommends that agencies formally inspect each dam that they own at least once every five years; however, some agencies require more frequent inspections and base the frequency of inspections on the dam's hazard potential.73 Inspections may result in an update of the dam's hazard potential and condition assessment (see Figure 8 for the status of hazard potential and condition assessments of federal dams). Inspections typically are funded through agency O&M budgets.74

The Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety recommend that agencies formally inspect each dam that they own at least once every five years; however, some agencies require more frequent inspections and base the frequency of inspections on the dam’s hazard potential or their risk-management approach.71 Inspections may result in an update of the dam’s hazard potential, among other categorical amendments. After identifying dam safety deficiencies, federal agencies may undertake risk reduction measures (e.g., nonstructural operation changes) or rehabilitation and repair activities. Agencies may not have funding available to immediately undertake all nonurgent rehabilitation and repair; rather, they generally prioritize their rehabilitation and repair investments based on various forms of assessment and schedule these activities in conjunction with the budget process.7572 At some agencies, dam rehabilitation and repair needs must compete

71 FEMA, Federal Guidelines; National Research Council, Dam and Levee Safety. 72 FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017; Michelle Ho et al., “The Future Role of Dams in the United States of America,” Water Resources Research, 2017, vol. 53, pp. 982-998.

Congressional Research Service

20

link to page 15 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

for funding with other construction projects (e.g., buildings and levees).73 The following sections briefly discuss dam safety activities at the three agencies managing the most federal dams.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers USACE implements a dam safety program consisting of inspections and risk analyses for USACE-operated dams, and performs risk reduction measures or project modifications to address dam safety risks.74 USACE uses a risk-informed approach for all dam safety program decisions and applies the Dam Safety Action Classification System (DSAC), which is based on the likelihood of failure in combination with loss of life, economic, or environmental consequences (see Table 3).75

Congress provides funding for USACE’s various dam safety activities through the Investigations, O&M, and Construction accounts.76 The Inventory of Dams line item in the Investigations account provides funding for the maintenance and publication of the NID. The O&M account provides funding for routine O&M of USACE dams and for NDSP activities, including assessments of USACE dams.

The Construction account provides funding for nonroutine dam safety activities (e.g., dam safety rehabilitation and repair modifications).77 The Dam Safety and Seepage/Stability Correction Program conducts nonroutine dam safety evaluations and studies of extremely high-risk or very high-risk dams (DSAC 1 and DSAC 2).78 Under the program, an issue evaluation study may evaluate high-risk dams, dam safety incidents, and unsatisfactory performance, and then provide determinations for modification or reclassification. If recommended, a dam safety modification study would further investigate dam deficiencies and propose alternatives to reduce risks to tolerable levels; a dam safety modification report is issued if USACE recommends a modification.79 USACE funds construction of dam safety modifications through project-specific

73 FEMA, National Dam Safety Program, 2016-2017. 74 The dam safety program is managed from headquarters, with the dam safety officer responsible for making all dam safety decisions and ensuring consistent prioritization decisions. USACE districts are responsible for executing the dam safety program, with oversight from their Dam Safety Production Centers (DSPCs). DSPCs are responsible for reviewing products and ensuring that all dam safety products meet policy requirements for the program. The Risk Management Center, which is available as a resource to all districts, provides expertise in dam safety disciplines and reviews dam safety products from a portfolio perspective. Personal correspondence between CRS and USACE, July 15, 2019. USACE prescribes flood and navigation operations for certain nonfederal dams under the authority of Section 7 of the Flood Control Act of 1944. However, USACE policy states that the nonfederal project owner of these dams “is responsible for the safety of the dam and appurtenant facilities and for regulation/operation of the project during surcharge storage…which results when the total storage space reserved for flood control is exceeded.” USACE, Water Control Manual, Chapter 4, 1110-2-240, May 30, 2016, at https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/portals/76/publications/engineerregulations/er_1110-2-240.pdf.

75 Incremental risk is the risk (e.g., the likelihood and consequences of inundation) to the reservoir area and downstream floodplain that can be attributed to the presence of the dam should the dam breach, overtop, or undergo malfunction or misoperation. For more information, see https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Dam-Safety-Program/Program-Activities/.

76 Personal correspondence between CRS and USACE, July 15, 2019. 77 Personal correspondence between CRS and USACE, July 15, 2019. 78 Sometimes USACE also evaluates Dam Safety Action Classification (DSAC) 3 dams under the Seepage/Stability Correction Program. Personal correspondence between CRS and USACE, July 15, 2019.

79 Interim risk-reduction measures for dam safety are developed, prepared, and implemented to reduce the probability and consequences of failure to the maximum extent that it is reasonably practicable while long-term remedial measures are pursued. USACE, Engineering and Design, Water Control Management, ER-1110-2-240, 2016, at https://www.publications.usace.army.mil/Portals/76/Publications/EngineerRegulations/ER_1110-2-240.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

21

link to page 15 Dam Safety Overview and the Federal Role

At some agencies, dam rehabilitation and repair needs must compete for funding with other construction projects (e.g., buildings and levees).76

|

Dam Rehabilitation and Repair on Native Lands The federal government is responsible for all dams on native lands in accordance with the Indian Dams Safety Act of 1994, as amended (P.L. 103-302; 25 U.S.C. 3801 et seq.). The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is in charge of 125 high or significant hazard dams listed in the NID. The BIA dams are on 43 reservations. The average age of the dams is 70 years, and one-third of the dams are classified as being in poor or unsatisfactory condition. In addition, there are over 700 additional low hazard potential or unclassified dams (not listed in the NID) on tribal lands. In April 2016, the BIA testified to the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs that $556 million was needed for deferred maintenance and repairs of BIA dams, with the backlog increasing by approximately 6% each year since 2010. Congress provided $38 million annually in FY2018 and FY2019 to the BIA for dam safety and maintenance. Low hazard dams receive less federal support and attention than high and significant hazard dams. The BIA reports that it is not aware of all low hazard dams under its jurisdiction. The Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN Act; P.L. 114-322) established two Indian dam safety funds for the BIA to address deferred maintenance needs at eligible dams. Eligible dams are those included in the BIA Safety of Dams Program established under the Indian Dams Safety Act of 1994 that are either dams owned by the federal government and managed by the BIA or dams that have deferred maintenance documented by the BIA. Over FY2017-FY2030, the WIIN Act, as amended by America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-270), authorized $22.75 million per year for the High Hazard Indian Dam Safety Deferred Maintenance Fund and $10 million per year for the Low Hazard Indian Dam Safety Deferred Maintenance Fund. As of FY2019, Congress has not provided appropriations to these funds to rehabilitate eligible dams. |

Federal agencies traditionally approached dam safety through a deterministic, standards-based approach by mainly considering structural integrity to withstand maximum probable floods and maximum credible earthquakes.77 Many agencies with large dam portfolios (e.g., Reclamation and USACE) have since moved from this solely standards-based approach for their dam safety programs to a portfolio risk management approach to dam safety, including evaluating all modes of failure (e.g., seepage of water and sediment through a dam) and prioritizing rehabilitation and repair efforts.78 The following sections provide more information on specific policies at these agencies.