Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Changes from October 10, 2019 to May 12, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Contents

- Introduction

- Apportionment Process

- Federal Requirements/Guidelines for Reapportionment: History and Current Policy

- Reapportionment Method and Timeline

- Redistricting Process

- Federal Requirements/Guidelines for Redistricting: History and Current Policy

- Population Equality

- Racial/Language Minority Protections

- Other Redistricting Considerations

- Compactness and Contiguity

- Preserving Political Subdivisions

- Preserving Communities of Interest

- Promoting Political Competition; Considering Existing District or Incumbent

- State Processes for Redistricting

- Congressional Options Regarding Redistricting

- Concluding Observations

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Loss or Gain of U.S. House Seats in States Following 2010 Census

- Table 2. Scope of Apportionment Changes, 1910-2010

- Table 3. Summary of Average U.S. House District Population Sizes, 1910-2010

- Table 4. Selected Congressional Redistricting Criteria Specified by Certain States

- Table A-1. Hamilton/Vinton Method—Sample Apportionment

- Table A-2. Jefferson Method—Sample Apportionment

- Table A-3. Webster Method—Sample Apportionment

- Table A-4. Huntington-Hill Method—Sample Apportionment

- Table A-5. Sample Priority Values and Resulting Priority List for Selected Values

Summary

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for

May 12, 2021

the U.S. House of Representatives

Sarah J. Eckman

The census, apportionment, and redistricting are interrelated activities that affect representation

Analyst in American

in the U.S. House of Representatives. Congressional apportionment (or reapportionment) is the

National Government

process of dividing seats for the House among the 50 states following the decennial census.

Redistricting refers to the process that follows, in which states create new congressional districts or redraw existing district boundaries to adjust for population changes and/or changes in the

number of House seats for the state. At times, Congress has passed or considered legislation addressing apportionment and redistricting processes under its broad authority to make law affecting House electionselectio ns under Article I, Section 4, of the U.S. Constitution. These processes are all rooted in provisions in Article I, Section 2 (as amended amen ded by Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment).

Seats for the House of Representatives are constitutionally required to be divided among the states, based on the population size of each state. To determine how many Representatives each state is entitled to, the Constitution requires the national population to be counted every 10 years, which is done through the census. The ConstitutionCon stitution also limits the number of Representatives to no more than one for every 30,000 persons, provided that each state receives at least one Representative. Additional parameters for the census and for apportionment have been established through federal statutes, including timelines for these processes; the number of seats in the House; and the method by which House seats are divided among states. Congress began creating more permanent legislation by the early 20th20th century to provide recurring procedures for the census and apportionment, rather than passing measures each decade to address an upcoming reapportionment cycle. Federal law related to the census process is found in Title 13 of the U.S. Code, and two key statutes affecting apportionment today are the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 and the Apportionment Act of 1941.

April 1 of a year ending in "0"“0” marks the decennial census date and the start of the apportionment population counting process; the Secretary of Commerce mustis to report the apportionment population of each state to the President by the end of that year. Within the first week of the first regular session of the next Congress, the President transmitsis to transmit a statement to the House relaying state population information and the number ofo f Representatives each state is entitled to. For a discussion of recent changes to this timeline, see CRS Insight IN11360, Apportionment and Redistricting Following the 2020 Census. Each Each state receives one Representative, as required by the Constitutionconstitutionally required, and the remaining seats are distributed using a mathematical approach known as the method of equal proportions, as established by the Apportionment Act of 1941. Essentially, a ranked "

“priority list"” is created that indicatesindicating which states will receive the 51st-435th51st-435th House seats, based on a calculation involving the population size of each stateeach state’s population size and the number of additional seats a state has received. The U.S. apportionment population from the 20102020 census was 309,183,463331,108,434, reflecting a 9.97.1% increase since 20002010, and 127 House seats were reapportioned among 1813 states.

After a census and apportionment are completed, state officials receive updated population information from the U.S. Census

Bureau and the state'’s allocation of House seats from the Clerk of the House. Single-member House districts are required by 2 U.S.C. §2c, and certain other redistricting standards, largely related to the composition of districts, have been established by federal statute and various legal decisions. Current federal parameters related to redistricting criteria generally address population equality and protections against discrimination for racial and language minority groups under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), as amended. Previous federal apportionment statutes have, at times, included other district criteria, such as geographic compactness or contiguity, and these standards have sometimes been referred to in U.S. Supreme Court cases, but they are not included in the current federal statutes that address the apportionment process. These redistricting principles and others, such as considering existing political boundaries, preserving communities of interest, and promoting political competition, have been commonly used across states, and many are reflected in state laws today.

The procedural elements of redistricting are generally governed by state laws, and state redistricting practices can vary regarding the methods used for drawing districts, timeline for redistricting, and which actors (e.g., elected officials, designated redistricting commissioners, and/or members of the public) are involved in the process. Mapmakers must often make trade-offs between one redistricting consideration and others, and making these trade-offs can add an additional challenge to an already complicated task of ensuring "fair"“fair” representation for district residents. Despite technological advances that make it easier to design districts with increasing geographic and demographic precision, the overall task of redistricting remains complex and, in many instances, can be controversial. A majority of states, for example, faced legal challenges to congressional district maps drawn following the 2010 census, and several cases remained pending in 2019—less than a year before the next decennial census date.

Introduction

these legal challenges can take multiple years to resolve.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 5 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 19 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 23 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Apportionment Process .................................................................................................... 1

Federal Requirements/Guidelines for Reapportionment: History and Current Policy ............ 4 Reapportionment Method and Timeline......................................................................... 5

Redistricting Process ....................................................................................................... 7

Federal Requirements/Guidelines for Redistricting: History and Current Policy .................. 8

Population Equality .............................................................................................. 9 Racial/Language Minority Protections ................................................................... 11

Other Redistricting Considerations ............................................................................. 11

Compactness and Contiguity ................................................................................ 13

Preserving Political Subdivisions .......................................................................... 13 Preserving Communities of Interest....................................................................... 14 Promoting Political Competition; Considering Existing District or Incumbent ............. 14

State Processes for Redistricting ................................................................................ 14 Congressional Options Regarding Redistricting............................................................ 17

Concluding Observations ............................................................................................... 17

Figures Figure 1. Typical Timeline of Census, Apportionment, and Redistricting Process ...................... 1 Figure 2. Changes to Average District Apportionment Population Sizes and House Seats

Over Last Four Apportionment Cycles, 1990-2020 ............................................................ 4

Figure 3. State Redistricting Methods............................................................................... 15

Tables Table 1. Loss or Gain of U.S. House Seats in States Following 2020 Census ............................ 3 Table 2. Scope of Apportionment Changes, 1910-2020 ......................................................... 3 Table 3. Summary of Average U.S. House District Population Sizes, 1910-2020 ..................... 10 Table 4. Selected Congressional Redistricting Criteria Specified by Certain States .................. 11

Table A-1. Hamilton/Vinton Method—Sample Apportionment ............................................. 21 Table A-2. Jefferson Method—Sample Apportionment........................................................ 22 Table A-3. Webster Method—Sample Apportionment ......................................................... 23 Table A-4. Huntington-Hill Method—Sample Apportionment .............................................. 24 Table A-5. Sample Priority Values and Resulting Priority List for Selected Values................... 25

Appendixes Appendix. Determining an Apportionment Method ............................................................ 19

Congressional Research Service

link to page 29 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 25

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Introduction Every 10 years, the U.S. population is counted through the national census, and districts for the U.S. House of Representatives are readjusted to reflect the new population level and its distribution across states through the federal apportionment and state redistricting processes. The requirement to have proportional representation in the House is found in the U.S. Constitution, and constitutional provisions also underlie other elements of the census, apportionment, and

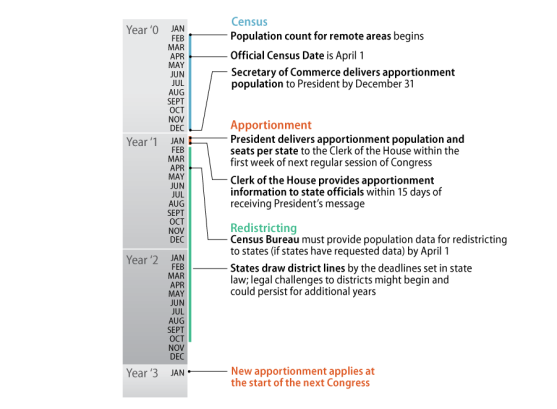

redistricting practices. Figure 1 provides a generalized timeline for how these three interrelated processes occur, and the sections of the report that follow provide additional information on apportionment and redistricting. For additional a discussion of how the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affected the timing of the most recent census and apportionment, see CRS Insight IN11360, Apportionment and Redistricting Following the 2020 Census. For additional

information on the census process, see CRS Report R44788, The Decennial Census: Issues for

2020, and CRS In Focus IF11015, The 2020 Decennial Census: Overview and Issues.

Apportionment Process

Apportionment (or reapportionment) refers to the process of dividing seats in the U.S. House of Representatives among the states. Article 1, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution, as amended by Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment, requires that seats for Representatives are divided among states, based on the population size of each state. House seats today are reallocatedreal ocated due to

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 14 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

due to changes in state populations, since the number of U.S. states (50) has remained constant since 1959; in earlier eras, the addition of new states would also affect the reapportionment process, as

each state is constitutionallyconstitutional y required to receive at least one House seat.

The 2010

The 2020 census reported a 9.9% overall 7.1% overal increase in the U.S. apportionment population since the 20002010 census, to 309,183,463 individuals.1331,108,434 individuals.1 The ideal (or average) district population size increased across allmost states following the 2010 census, even thoughfol owing the 2020 census, and some states experienced larger growth levels than others.2 Three states experienced decreases in average district population size following the 2020 census.3 The average congressional district population for the United States following the

2020 census was 761,169 individuals.4 Seventhan others.2 The average congressional district population for the United States following the 2010 census was 710,767 individuals.3

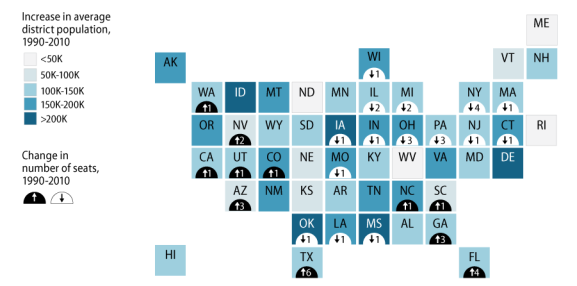

The map in Figure 2 illustrates changes in states' ideal district size and changes in the number of House seats allocated to each state between the 1990 and 2010 apportionments. Twelve U.S. House seats shifted across states following the 20102020 census; 10seven states lost seats and 8six states gained seats, distributed as shown inin Table 1. Table 2 provides additional historical data on the number of states and number of seats affected

by each apportionment since 1910.

The map in Figure 2 il ustrates changes in states’ ideal district size and changes in the number of House seats al ocated to each state between the 1990 and 2020 apportionments. Regional patterns of population change observed following previous censuses continued in 20102020, as the percentage of House seats distributed across the Northeast and Midwest regions decreased, and the

percentage of House seats distributed across the South and West regions increased.45 California had the largest House delegation following the 20102020 census, with 5352 seats; Alaska, Delaware, Montana,

North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming each had a single House seat.5

6

1 T he apportionment population reflects the total resident population in each of the 50 states, including minors, noncitizens, Armed Forces personnel/dependents living overseas, and federal civilian employees/dependents living overseas; for more information see U.S. Census Bureau, “ Congressional Apportionment: Frequently Asked Questions,” January 8, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/topics/public-sector/congressional-apport ionment/about/faqs.html. For 2020 census results, see U.S. Census Bureau, “T able A. Apportionment Population, Resident Population, and Overseas Population: 2020 Census and 2010 Census,” 2020 Census Apportionment Results, April 26, 2021, at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/apportionment/apportionment-2020-tableA.xlsx

2 Colorado had the smallest increase in average district population size after the 2020 census, increasing by 2,067 individuals on average per district when compared to the 2010 census. West Virginia had the largest increase in average district population size after the 2020 census, increasing by 277,585 individuals on average per district when compared to the 2010 census. CRS calculations based on information provided in U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Apportionm ent Data (1910-2020), April 26, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/apportionment -data-text.html. 3 Montana’s average district population size decreased by 451,712 individuals, Oregon’s average district population size decreased by 62,804 individuals, and Mississippi’s average district population size decreased by 3,581 individuals after the 2020 census. CRS calculations based on information provided in U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Apportionm ent Data (1910-2020), April 26, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/apportionment -data-text.html.

4 U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Apportionment Data (1910-2020), at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/apportionment-data-text.html. See Table 3 for further information on average congressional district sizes since 1910. 5 See U.S. Census, “Presentation: 2020 Census Apportionment News Conference,” 2020 Census Apportionment Counts Press Kit, April 26, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/newsroom/press-kits/2021/20210426-apportionment -presentation.pdf; see also Paul Mackun and Steven Wilson, Population Distribution and Change: 2000:2010, U.S. Census Bureau, Report Number C2010BR-01, Washington, DC, March 2011, at https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-01.pdf; and Kristen D. Burnett, Congressional Apportionm ent: 2010 Census Briefs, U.S. Census Bureau, Report Number C2010BR-08, Washington, DC, November 2011, pp. 4 -5, at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-08.pdf. Historical information dating back to 1910 on state seat gains and losses, as well as the average number of people per representative in each state, is available from U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Apportionm ent Data (1910-2020), April 26, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/apportionment -data-text.html. 6 U.S. Census Bureau, “T able 1. Apportionment Population and Number of Representatives by State: 2020 Census,”

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 8 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Table 1. Loss or Gain of U.S. House Seats in States Following 2020 Census

Lost U.S. House Seats

Gained |

Gained U.S. House Seats |

||

|

State |

Seat Change |

State |

Seat Change |

|

Illinois |

-1 |

Arizona |

+1 |

|

Iowa |

-1 |

Florida |

+2 |

|

Louisiana |

-1 |

Georgia |

+1 |

|

Massachusetts |

-1 |

Nevada |

+1 |

|

Michigan |

-1 |

South Carolina |

+1 |

|

Missouri |

-1 |

Texas |

+4 |

|

New Jersey |

-1 |

Utah |

+1 |

|

New York |

-2 |

Washington |

+1 |

|

Ohio |

-2 |

||

|

Pennsylvania |

-1 |

||

Source: Kristen D. Burnett, Congressional Apportionment: 2010 Census Briefs, U.S. Census Bureau, Report Number C2010BR-08, Washington, DC, November 2011, at https://wwwU.S. House Seats

State

Seat Change

State

Seat Change

California

-1

Colorado

+1

Il inois

-1

Florida

+1

Michigan

-1

Montana

+1

New York

-1

North Carolina

+1

Ohio

-1

Oregon

+1

Pennsylvania

-1

Texas

+2

West Virginia

-1

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “Table D1. Number of Seats Gained and Lost in U.S. House of Representatives by State: 2020 Census,” 2020 Census Apportionment Results, April 26, 2021, at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/apportionment/apportionment-2020-tableD.xlsx.

Table 2. Scope of Apportionment Changes, 1910-2020

Total States

House Seats

States Losing

States Gaining

Affected By

Affected by

Census Year

Seats

Seats

Apportionment

Apportionment

2020

7 (14.0%)

6 (12.0%)

13 (26.0%)

7 (1.6%)

2010

.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-08.pdf.

|

Census Year |

States Losing Seats |

States Gaining Seats |

Total States Affected By Apportionment |

House Seats Affected by Apportionment |

|

2010 |

10 (20.0%) |

10 (20.0%)

8 (16.0%)

|

18 (36.0%) |

18 (36.0%)

12 (2.8%)

2000

|

|

2000 |

10 (20.0%) |

10 (20.0%)

8 (16.0%)

|

18 (36.0%) |

18 (36.0%)

12 (2.8%)

1990

|

|

1990 |

13 (26.0%) |

13 (26.0%)

8 (16.0%)

|

21 (42.0%) |

21 (42.0%)

19 (4.4%)

1980

|

|

1980 |

10 (20.0%) |

10 (20.0%)

11 (22.0%)

|

21 (42.0%) |

21 (42.0%)

17 (3.9%)

1970

|

|

1970 |

9 (18.0%) |

9 (18.0%)

5 (10.0%)

|

14 (28.0%) |

14 (28.0%)

11 (2.5%)

1960a

|

|

16 (32.0%) |

16 (32.0%)

10 (20.0%)

|

26 (52.0%) |

26 (52.0%)

21 (4.8%)

1950b

|

|

9 (18.8%) |

9 (18.8%)

7 (14.6%)

|

16 (33.3%) |

16 (33.3%)

14 (3.2%)

1940b

|

|

9 (18.8%) |

9 (18.8%)

7 (14.6%)

|

16 (33.3%) |

16 (33.3%)

9 (2.1%)

1930b

|

|

21 (43.8%) |

21 (43.8%)

13 (27.1%)

|

34 (70.8%) |

34 (70.8%)

27 (6.2%)

1920c

—

—

—

—

1910d

|

|

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%)

25 (54.3%)

|

25 (54.3%) |

25 (54.3%)

47 (10.9%)

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census: Apportionment Data MapHistorical Apportionment Data Map, April 26, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/2010census/data/apportionment-data-map.html.

a. The 1960 apportionment was the first to include Hawaii and Alaska, which became states in 1959.

b. Apportionments between 1930 and 1950 occurred with 48 states.

c. No apportionment occurred after the 1920 census.

d. library/visualizations/interactive/historical-apportionment-data-map.html.

2020 Census Apportionm ent Results, April 26, 2021 at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/data/apportionment/apportionment-2020-table01.xlsx.

Congressional Research Service

3

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

a. The 1960 apportionment was the first to include Hawai and Alaska, which became states in 1959 . b. Apportionments between 1930 and 1950 occurred with 48 states. c. No apportionment occurred after the 1920 census. d. The 1910 apportionment occurred with a House size of 433 and 46 states. Two seats were added to the

House once Arizona and New Mexico became states in 1912.

Figure 2. Changes to Average District Apportionment Population Sizes and House Seats Over Last Four Apportionment Cycles, 1990-2020 Source: CRS compilation of apportionment population data for 1990 and 2020 from the U.S. Census Bureau. Graphic created by Amber Hope Wilhelm, CRS Visual Information Specialist. Federal Requirements/Guidelines for Reapportionment: History and Current Policy

The constitutional requirements for representation in the House based on state population size are provided in Article I, Section 2, as amended by Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment.67 Article

I, Section 2, specified the first apportionment of seats for the House of Representatives,78 and it also includes some standards for subsequent reapportionments. Article I, Section 2, requires that the national population be counted at least once every 10 years in order to distribute House seats across states. Broad parameters for the number of House Members are also contained in Article I, 7 Article I, Section 2, clause 3, originally stated, “Representatives and direct T axes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding t o the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a T erm of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.” Following the abolition of slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment, Section 2, states, “ Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. ” For more information, see Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives, “ Propo rtional Representation,” at https://history.house.gov/Institution/Origins-Development/Proportional-Representation/.

8 Article 1, Section 2, provides that a first census would be taken within three years of the first meeting of Congress, and until the population was formally enumerated by a census, there would be 65 House Members, allocated among New Hampshire (3), Massachusetts (8), Rhode Island (1), Connecticut (5), New York (6), New Jersey (4), Pennsylvania (8), Delaware (1), Maryland (6), Virginia (10), North Carolina (5), South Carolina (5), and Georgia (3).

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 5 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

across states. Broad parameters for the number of House Members are also contained in Article I, Section 2: there can be no more than one Representative for every 30,000 persons, provided that

each state receives at least one Representative.

Federal statute establishes a number of other elements of the apportionment process, including

how to count the population every 10 years via the decennial census; how many seats are in the House; how those House seats are divided across states; and certain related administrative details. In the 19th19th century, Congress often passed measures each decade to address those factors, specifically specifical y for the next upcoming census and reapportionment. By the early 20th20th century, however, Congress began to create legislation to standardize the process and apply it to all al

subsequent censuses and reapportionments, unless modified by later acts.8

9

One example of such legislation was the permanent authorization of the U.S. Census Bureau in 1902,910 which helped establish a recurring decennial census process and timeline. Other legislation

legislation established the current number of 435 House seats;1011 this number was first used following the 1910 census and subsequently became fixed under the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929.1112 Congress also created a more general reapportionment formula and process to redistribute seats across states. The timeline for congressional reapportionment and current method for allocatingal ocating seats among states were contained in the Apportionment Act of 1941,

which would then apply to every reapportionment cycle, beginning with the one following the 1950 census.1213 The size of the House, method for reapportionment, and timeline for reapportionment are codified in 2 U.S.C. §2a and are further detailed in the section below,

alongside the relevant census procedures codified in Title 13 of the U.S. Code.

Reapportionment Method and Timeline

The apportionment steps detailed below are also summarized by the timeline in in Figure 1. Under federal law, April 1 in any year ending in "0" This information is representative of the typical census, apportionment, and redistricting processes, but

the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affected 2020 census field operations and delivery of apportionment figures; for further discussion of these changes and delays, see CRS In Focus IF11486, 2020 Census Fieldwork Delayed by COVID-19 and CRS Insight IN11360,

Apportionment and Redistricting Following the 2020 Census.

Under federal law, April 1 in any year ending in “0” marks the official decennial census date and the beginning of the population counting process.13 The U.S. Census Bureau calculates the 14 The U.S. Census Bureau calculates the

9 For one overview of provisions contained in various apportionment acts, see Emanuel Celler, “Congressional Apportionment—Past, Present, and Future,” Law and Contem porary Problem s, vol. 17, no. 2 (Spring 1952), pp. 268 -275, at https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/lcp/vol17/iss2/3/. Copies of past apportionment acts (1790 -1941) are available from the U.S. Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/apportionment .

10 13 U.S.C. §2 note. 11 T his excludes the nonvoting House seats held by Delegates and the Resident Commissioner; Article I, Section 2, and resulting apportionment practices, only address Representatives from U.S. states. 12 T he 1910 apportionment act (P.L. 62-5, August 8, 1911, 37 Stat. 13, Ch. 5) set the House size at 433, but provided for the addition of one seat each to New Mexico and Arizona, if they became states before the next apportionment, which they did. T he next enacted apportionment bill was the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 (P.L. 71-13, June 18, 1929, 26 Stat. 21, Ch. 28), which preserved the methods of the preceding apportionment for subsequent apportionments. The enabling acts for Alaska and Hawaii statehood provided temporary increases in the size of the House to provide seats for the new states until the next regular reapportionment, and as a result, the House had 437 seats between 1959 and 1962. See P.L. 85 -508, July 7, 1958; P.L. 86-3, March 18, 1959, 73 Stat. 4.

13 P.L. 77-291, November 15, 1941, 55 Stat. 761, Ch. 470. Similar provisions were contained in the Permanent Reapportionment Act of 1929. 14 13 U.S.C. §141(a). For additional information on the census process, see CRS Report R44788, The Decennial

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 23 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

apportionment population for the United States from the information it collects in the decennial census and certain administrative records.1415 The apportionment population reflects the total resident population in each of the 50 states, including minors and noncitizens, plus Armed Forces personnel/dependents living overseas and federal civilian employees/dependents living overseas.1516 The Secretary of Commerce must report the apportionment population to the President within nine months of the census date (by December 31 of the year ending in "0").16“0”).17 In past years,

the Census Bureau has released apportionment counts to the public at about the same time they

are presented to the President.17

18

Under requirements in the Constitution, each state must receive at least one House Representative, and under statute, the current House size is set at 435 seats.1819 To determine how the 51st through 435ththe 51st through 435th seats are distributed across the 50 states, a mathematical approach known as the method of equal proportions is used, which is specified in statute.19 Essentially20 Essential y, under this method, the "next"“next” House seat available is apportioned to the state ranked highest on a priority list. The priority list rankings are calculated by taking each state'’s apportionment population from

the most recent census, and multiplying it by a series of values. The multipliers used are the reciprocals of the geometric means between every pair of consecutive whole numbers, with those whole numbers representing House seats to be apportioned.2021 The resulting priority values are ordered from largest to smallestsmal est, and with the House size set at 435, the states with the top 385 priority values receive the available seats. See thethe Appendix for additional information on the

method of equal proportions and other methods proposed or used in previous apportionments.

The President then transmits a statement to Congress showing (1) "“the whole number of persons in each State,"” as determined by the decennial census and certain administrative records; and (2)

the resulting number of Representatives each state would be entitled to under an apportionment, given the existing number of Representatives and using the method of equal proportions. The President submits this statement to Congress within the first week of the first regular session of Census: Issues for 2020; and CRS In Focus IF11015, The 2020 Decennial Census: Overview and Issues.

15 13 U.S.C. §141(b). 16 For further discussion of who is included in apportionment population counts, see U.S. Census Bureau, “Congressional Apportionment: Frequently Asked Questions,” August 26, 2015, at https://www.census.gov/topics/public-sector/congressional-apportionment/about/faqs.html.

17 13 U.S.C. §141(b). 18 For example, see U.S. Census Bureau, “U.S. Census Bureau Announces 2010 Census Population Counts Apportionment Counts Delivered to President,” press release, December 21, 2010, at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb10-cn93.html.

19 Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, P.L. 71-13, June 18, 1929, 26 Stat. 21, Ch. 28. 20 P.L. 77-291, November 15, 1941, 55 Stat. 761, Ch. 470. T he method of equal proportions is sometimes referred to as the Huntington-Hill m ethod. Prior to the 1941 act, other apportionment methods could be used; one such alternative used in several reapportionments was the Webster m ethod. Generally, these apportionment methods vary in how they approach fractional seat entitlements and what rounding points should be used in order to distribute those fractions of seats across states. For a discussion of alternate mathematical approaches, see U.S. Census Bureau, “ Methods of Apportionment,” July 18, 2017, at https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/apportionment/methods_of_apportionment.html; and Laurence F. Schmeckebier, “ T he Method of Equal Proportions,” Law and Contem porary Problem s, vol. 17, no. 2 (Spring 1952), pp. 302 -313.

21 A geometric mean is the square root of the product of two successive numbers multiplied by each other; the reciprocal of a geometric mean is 1 divided by the geometric mean. T o find the “multiplier” for each state’s second seat, for example, the geometric mean of 1 and 2 would be used; 1 multiplied by 2 equals 2, and the square root of 2 is 1.41452. T he reciprocal of this geometric mean would be 1 divided by 1.41452, or 0.70711. For discussion on the method of equal proportions, and tables with multipliers and priority values for previous ap portionments, see U.S. Census Bureau, “Computing Apportionment,” Congressional Apportionment, February 4, 2013, at https://www.census.gov/population/apportionment/about /computing.html.

Congressional Research Service

6

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

the next Congress (typical yPresident submits this statement to Congress within the first week of the first regular session of the next Congress (typically, early January of a year ending in "1").21“1”).22 Within 15 calendar days of receiving the President'’s statement, the Clerk of the House sends each state governor a certificate indicating the number of Representatives the state is entitled to. Each state receives the number of Representatives noted in the President'’s statement for its House delegation, beginning at the start

of the next session of Congress (typicallytypical y, early January of a year ending in "3").

“3”).

States may then engage in their own redistricting processes, which vary based on state laws. Federal law contains requirements for how apportionment changes will wil apply to states in the event that any congressional elections occur between a reapportionment and the completion of a state'

state’s redistricting process. In these instances, states with the same number of House seats would use the existing congressional districts to elect Representatives; states with more seats than districts would elect a Representative for the "new"“new” seat through an at-large election and use existing districts for the other seats; and states with fewer seats than districts would elect all al

Representatives through an at-large election.22

Redistricting Process23

23

Redistricting Process24 Congressional redistricting involves creating or redrawing geographic boundaries for U.S. House districts within a state. Redistricting procedures are largely determined by state law and vary across states, but states must comply with certain parameters established by federal statute and court decisions. In general, there is variation among states regarding the practice of drawing districts and which decisionmakers are involved in the process. Across states, there are some

common standards and criteria for districts, some of which reflect values that are commonly thought of as traditional districting practices. Districting criteria may result either from shared expectations and precedent regarding what districts should be like, or they may result from certain standards established by current federal statute and court decisions. These criteria typicallytypical y reflect a goal of enabling "fair"“fair” representation for all al residents, rather than allowing al owing

arbitrary, or discriminatory, map lines.24

25

Redistricting efforts intended to unfairly favor one group'’s interests over another'’s are commonly referred to as gerrymandering.2526 Packing and cracking are two common terms that describe such

districts, but there are various ways in which district boundaries might be designed to advantage or disadvantage certain groups of voters. Packing describes district boundaries that are drawn to concentrate individuals who are thought to share similar voting behaviors into certain districts. Concentrating prospective voters with shared preferences can result in a large number of "“wasted votes" for these districts, as their Representatives will

22 P.L. 77-291, November 15, 1941, 55 Stat. 761, Ch. 470. T he statute is written to apply to the first regular session of the 82nd Congress “ and of each fifth Congress thereafter.”

23 2 U.S.C. §2a(c). 24 T his report is not intended to be a legal analysis. For additional information on redistricting law, see CRS Report R44199, Congressional Redistricting: Legal and Constitutional Issues; and CRS Report R44798, Congressional Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings. 25 For further discussion, see Jeanne C. Fromer, “An Exercise in Line-Drawing: Deriving and Measuring Fairness in Redistricting,” Georgetown Law Journal, vol. 93 (2004-2005), pp. 1547-1623. 26 Michael Wines, “What Is Gerrymandering? What If the Supreme Court Bans It?” New York Times, March 26, 2019, at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/26/us/what -is-gerrymandering.html; John O’Loughlin, “ T he Identification and Evaluation of Racial Gerrymandering,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 72, no. 2 (June 1982), pp. 165-184; John N. Friedman and Richard T . Holden, “ T he Rising Incumbent Reelection Rate: What’s Gerrymandering Got to Do With It?” Journal of Politics, vol. 71, no. 2 (April 2009), pp. 593-611; CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10164, Partisan Gerrym andering: Suprem e Court Provides Guidance on Standing and Maintains Legal Status Quo.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 link to page 7 link to page 7 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

votes” for these districts, as their Representatives wil often be elected by a supermajority that far exceeds the number of votes required for a candidate to win. Cracking may be thought of as the opposite of packing, and occurs when individuals who are thought to share similar voting preferences are deliberately dispersed across a number of districts. This approach dilutes the voting strength of a group and can prevent its preferred candidates from receiving a majority of

the vote in any district.

For some states, redistricting following an apportionment may be necessary to account for House seats gained or lost based on the most recent census population count.26 Generally27 General y, however,

states with multiple congressional districts engage in redistricting following an apportionment in order to ensure that the population size of each district remains approximately equal under the equality standard or "“one person, one vote"” principle (discussed under "Population Equality" “Population Equality” below). Some states might make additional changes to district boundaries in the years following an initial redistricting; in some instances, such changes are required by legal decisions finding

that the initial districts were improperly drawn.27

28 Federal Requirements/Guidelines for Redistricting: History and Current Policy

From time to time, Congress considers legislation that would affect apportionment and redistricting processes. The Constitution requires the apportionment of House seats across states based on population size, but it does not specify how those seats are to be distributed within each state. Most redistricting practices are determined by state constitutions or statutes, although some

parts of the redistricting process are affected by federal statute or judicial interpretations.28

29

The current system of single-member districts (rather than a general ticket system, where voters

could select a slate of Representatives for an entire state) is provided by 2 U.S.C. §2c.2930 In addition to requiring single-member districts, Congress has, at times, passed legislation addressing House district characteristics. For example, in the 1800s and early 1900s, some federal apportionment statutes included other standards for congressional districts, such as population equality or geographic compactness.3031 None of these criteria is expressly contained in the current

statute addressing federal apportionment.31

32

27 Table 1 provides information on which states gained and lost seats following the 2020 census, and Table 2 provides additional historical data on the number of states and House seats affected by each apportionment since 1910. 28 CRS Report R44798, Congressional Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings. 29 Ibid. 30 P.L. 90-196, December 14, 1967, 81 Stat. 581. The requirement for single-member districts had previously appeared in the Apportionment Act of 1842 (June 25, 1842, 5 Stat. 491). For additional history, see Erik J. Engstrom, “T he Origins of Single-Member Districts,” ch. 3 in Partisan Gerrym andering and the Construction of Am erican Dem ocracy (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2013), pp. 43 -55. 31 Examples include a requirement for equal population size “as nearly as practicable” ( “An Act for the Apportionment of Representatives to Congress among the several States according to the ninth Census,” February 2, 1872, 17 Stat. 28); and districts of “ contiguous and compact territory” (“An Act Making an apportionment of Representatives in Congress among the several States under the T welfth Census,” January 16, 1901, 31 Stat. 733; “ An Act for the apportionment of Representatives in Congress among the several States under the T hirteenth Census, ” P.L. 62-5, August 8, 1911, 37 Stat. 13, Ch. 5). Some of these provisions appeared in several subsequent apportionment bills.

32 P.L. 77-291, November 15, 1941, 55 Stat. 761, Ch. 470.

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 14 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Many of the other federal parameters for congressional redistricting have resulted from judicial decisions.3233 It is not uncommon for states to face legal challengeschal enges regarding elements of their redistricting plans.3334 One analysis of the 2010 redistricting cycle, for example, found that redistricting lawsuits had been filed in 38 states,3435 and legal challengeschal enges to congressional districts in several states continued into 2019.35for a number of years.36 This report is not intended to be a legal analysis. For additional information on redistricting law, see CRS Report R44199, Congressional

Redistricting: Legal and Constitutional Issues, and CRS Report R44798, Congressional

Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings.

Population Equality

One area of redistricting addressed by federal standards is population equality across districts. Legislative Legislative provisions, requiring that congressional districts "“[contain] as nearly as practicable an

equal number of inhabitants,"” were found in federal apportionment acts between 1872 and 1911.36 37 The U.S. Supreme Court has also addressed population size variance among congressional districts within a state, or malapportionment. Under what is known as the "“equality standard"” or "“one person, one vote"” principle, the Court has found congressional districts within a state should be drawn to approximately equal population sizes.37 Mathematically38 Mathematical y, there are several ways in

which the population difference across districts (or deviation from an ideal district size) may be expressed.38

expressed.39

These equal population standards apply only to districts within a state, not to districts across

states. To illustrateil ustrate how district population sizes can vary across states, Table 3 provides Census Bureau estimates from 1910 to 20102020 for the average district population size nationwide, as well wel as estimates for which states had the largest and smallestsmal est average district population sizes. Wide variations in state populations and the U.S. Constitution'’s requirement of at least one House seat per state make it difficult to ensure equal district sizes across states, particularly if the size of the House is fixed.39 The expectation that districts in a state will

33 See CRS Report R44798, Congressional Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings, for additional information. 34 Adam Mueller, “T he Implications of Legislative Power: State Constitutions, State Legislatures, and Mid-Decade Redistricting,” Boston College Law Review, vol. 48 (2007), p. 1344. 35 “Redistricting Lawsuits Relating to the 2010 Census,” Ballotpedia, updated September 2015, at https://ballotpedia.org/Redistricting_lawsuits_relating_to_the_2010_Census.

36 For one listing of litigation across states for both congressional districts and state legislative districts, see Michael Li, T homas Wolf, and Annie Lo, “T he State of Redistricting Litigation,” Brennan Center for Justice, April 1, 2021, at https://www.brennancenter.org/blog/state-redistricting-litigation. See also “ Redistricting Lawsuits Relating to the 2010

Census,” Ballotpedia, updated September 2015, at https://ballotpedia.org/Redistricting_lawsuits_relating_to_the_2010_Census. T hese resources provide examples of some recent legal challenges but may not represent a comprehensive account of all cases.

37 Historical apportionment acts can be viewed at U.S. Census Bureau, “Apportionment Legislation 1840-1880,” History, at https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/apportionment/apportionment_legislation_1840_-_1880.html; U.S. Census Bureau, “ Apportionment Legislation 1890 -Present,” History, at https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/apportionment/apportionment_legislation_1890_-_present.html.

38 See CRS Report R44798, Congressional Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings.

For an overview of these, and related, Supreme Court cases, see National Conference of State Legislatures, “ Cases Relating to Population,” in Redistricting and the Supreme Court: The Most Significant Cases, July 19, 2018, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-and-the-supreme-court -the-most-significant-cases.aspx; also National Conference of State Legislatures, “ Equal Population,” in Redistricting Law 2010, December 1, 2009, ch. 3, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-law-2010.aspx.

39 See National Conference of State Legislatures, “Measuring Population Equality Among Districts,” in Redistricting Law 2010, December 1, 2009, pp. 23-25, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-law-2010.aspx.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 14 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

House is fixed.40 The expectation that districts in a state wil have equal population sizes reinforces the long-standing practice that states redraw district boundaries following each U.S. Census, in order to account for the sizable population shifts that can occur within a 10-year span.40

span.41

Table 3. Summary of Average U.S. House District Population Sizes, 1910-2020

Apportionment

Average District

Largest Average

Smallest Average

Year

Population Size

District Population

District Population

2020

761,169

990,837 (Delawarea)

542,704 (Montana)

2010

710,767

994,416 (Montanaa)

527,624 (Rhode Island)

2000

646,952

905,316 (Montanaa)

495,304 (Wyominga)

1990

572,466

803,655 (Montanaa)

455,975 (Wyominga)

1980

519,235

690,178 (South Dakotaa)

393,345 (Montana)

1970

469,088

624,181 (North Dakotaa) 304,067 (Alaskaa)

1960b

410,481

484,633 (Maine)

226,167 (Alaskaa)

1950c

344,587

395,948 (Rhode Island)

160,083 (Nevadaa)

1940c

301,164

359,231 (Vermonta)

110,247 (Nevadaa)

1930c

280,675

395,982 (New Mexicoa)

86,390 (Nevadaa)

1920d

—

—

—

1910e

210,328

228,027 (Washington)

80,293 (Nevadaa)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Apportionment Data (1910-2020), at Table 3. Summary of Average U.S. House District Population Sizes, 1910-2010

|

Apportionment Year |

Average District Population Size |

Largest Average District Population |

Smallest Average District Population |

|

2010 |

710,767 |

|

527,624 (Rhode Island) |

|

2000 |

646,952 |

|

|

|

1990 |

572,466 |

|

|

|

1980 |

519,235 |

|

393,345 (Montana) |

|

1970 |

469,088 |

|

|

|

410,481 |

484,633 (Maine) |

|

|

344,587 |

395,948 (Rhode Island) |

|

|

301,164 |

|

|

|

280,675 |

|

|

|

— |

— |

— |

|

210,328 |

228,027 (Washington) |

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census: Apportionment Data Map, at https://www.census.gov/2010census/data/https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/apportionment-data-maptext.html. a. .html.

a. State had a single House district during the noted apportionment year.

b. The 1960 apportionment was the first to include Hawaii Hawai and Alaska, which became states in 1959.

c. c. Apportionments between 1930 and 1950 occurred with 48 states.

d. d. No apportionment occurred after the 1920 Census.

e. e. The 1910 apportionment occurred with a House size of 433 and 46 states. Two seats were added to the

House once Arizona and New Mexico became states in 1912.

To assist states in drawing districts that have equal population sizes, the Census Bureau provides population tabulations for certain geographic areas identified by state officials, if requested, under the Census Redistricting Data Program, created by P.L. 94-171 in 1975. Under the program, the Census Bureau is required to provide total population counts for small smal geographic areas; in

practice, the Bureau also typicallytypical y provides additional demographic information, such as race,

ethnicity, and voting age population, to states.41

Racial/Language Minority Protections42

42

40 U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Apportionment Data (1910-20202), at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/apportionment -data-text.html. See also Drew Desilver, “ U.S. Population Keeps Growing, But House of Representatives Is Same Size As in T aft Era,” FactTank, Pew Research Center, May 31, 2018, at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/31/u-s-population-keeps-growing-but-house-of-representatives-is-same-size-as-in-taft-era/.

41 Adam Mueller, “T he Implications of Legislative Power: State Constitutions, State Legislatures, and Mid-Decade Redistricting,” Boston College Law Review, vol. 48 (2007), p. 1351. 42 P.L. 94-171, December 23, 1975, 89 Stat. 1023; 13 U.S.C. §141(c). See also U.S. Census Bureau, “Redistricting Data Program Management,” updated December 27, 2018, at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/rdo/program-management.html; and Catherine McCully, Designing P.L. 94-171 Redistricting Data for

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 15 link to page 17 link to page 17 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Racial/Language Minority Protections43

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) also affects how congressional districts are drawn. One key statutory requirement for congressional districts comes from Section 2 of the VRA, as amended, which prohibits states or their political subdivisions from imposing any voting qualification, practice, or procedure that results in denial or abridgement of the right to vote based on race,

color, or membership in a language minority.4344 Under the VRA, states cannot draw district maps

that have the effect of reducing, or diluting, minority voting strength.44

45 Other Redistricting Considerations

In addition to requirements of population equality and compliance with the VRA, several other redistricting criteria are common across many states today, including compactness, contiguity, and observing political boundaries.4546 Some of the common redistricting criteria specified by states are presented inin Table 4. These factors are sometimes referred to as traditional districting

principles and are often related to geography. The placement of district boundaries, for example, might reflect natural features of the state'’s land; how the population is distributed across a certain land area; and efforts to preserve existing subdivisions or communities (such as town boundaries or neighborhood areas). Redistricting laws in many states currently include such criteria, but they are not explicitly addressed in current federal statute. Previous federal apportionment statutes,

however, sometimes contained similar provisions.

Table 4. Selected Congressional Redistricting Criteria Specified by Certain States

f s o

g

ie

e

in

us

ns

iv

io

uo

air

is

unit

pact

al

m

petit

P

bents

m

ntig

re”

id

litic

m

m

o

tate

o

o

o

ubdiv

o

o

reserve

vo

S

C

C

P

S

C

Interest

C

P

“C

A

Incum

AL

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yesa

AZ

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

CA

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

CO

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

FL

Yes

Yes

Yes

GA

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yesa

the Year 2020 Census: The View from the States, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, December 2014, at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2014/rdo/pl94-171.html.

43 T his report is not intended to be a legal analysis of these topics; for additional information on related redistricting law, see CRS Report R44199, Congressional Redistricting: Legal and Constitutional Issues; and CRS Report R44798, Congressional Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings. 44 52 U.S.C. §§10301, 10303(f)(2). 45 52 U.S.C. §10304; for further discussion, see CRS Report R44798, Congressional Redistricting Law: Background and Recent Court Rulings, pp. 6-12.

46 An overview of common districting principles, and a chart detailing current requirements across states, are available in National Conference of State Legislatures, “ Redistricting Criteria,” April 23, 2019, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-criteria.aspx. For an overview of how certain criteria have been applied over time, see Micah Altman, “T raditional Districting Principles: Judicial Myths vs. Reality,” Social Science History, vol. 22, no. 2 (Summer 1998), pp. 159-200.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

f s o

g

ie

e

in

us

ns

iv

io

uo

air

is

unit

pact

al

m

petit

P

bents

m

ntig

re”

id

litic

m

m

o

tate

o

o

o

ubdiv

o

o

reserve

vo

S

C

C

P

S

C

Interest

C

P

“C

A

Incum

HI

Yes

Yes

Yes

ID

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

IA

Yes

Yes

Yes

KS

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

KY

Yes

Yes

Yes

LA

Yes

Yes

Yes

ME

Yes

Yes

Yes

MI

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

MN

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

MS

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yesa

MO

Yes

Yes

MT

Yes

Yes

Yes

NE

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

NV

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

NM

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yesa

Yesa

NY

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

NC

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yesa

OH

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

OK

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

OR

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

PA

Yes

Yes

Yes

RI

Yes

Yes

Yes

SC

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

TX

Yes

Yes

UT

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

VA

Yes

Yes

Yes

WA

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

WV

Yes

Yes

Yes

WYb

Yes

Yes

Yes

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures, “Redistricting Systems: A 50-State Overview,” March 29, 2021, at https://www.ncsl.org/research/redistrict ing/redist ricting-systems-a-50-state-overview.aspx; and individual state pages linked from Bal otpedia, “State-by-State Redistricting Procedures,” at https://bal otpedia.org/State-by-state_redistricting_procedures. Additional information may be available from individual states. See the fol owing text sections for an explanation of the criteria Table 4. Selected Congressional Redistricting Criteria Specified by Certain States

|

State |

Compact |

Contiguous |

Political Subdivisions |

Communities of Interest |

Competitive |

Preserve "Core" |

Avoid Pairing Incumbents |

|

AL |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

AZ |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

CA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

CO |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

FL |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

GA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

HI |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

ID |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

IA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

KS |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

KY |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

LA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

ME |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

MI |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

MN |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

MS |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

MO |

Yes |

Yes |

|||||

|

NE |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

NV |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

NM |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

| |

|

NY |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

NC |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| |||

|

OH |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

OK |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

OR |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

PA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

RI |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

SC |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

TX |

Yes |

Yes |

|||||

|

UT |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

VA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

WA |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

WV |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

||||

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures, "Redistricting Criteria," April 23, 2019, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-criteria.aspx; and individual state pages linked from Ballotpedia, "State-by-State Redistricting Procedures," at https://ballotpedia.org/State-by-state_redistricting_procedures. Additional information may be available from individual states. See the following text sections for an explanation of the criteria used as column headings in this table.

used as column headings in this table.

Congressional Research Service

12

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

Notes: States excluded from this table do not specify any of these criteria for congressional redistricting. These states are Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Il inois, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wisconsin. Some of these states (Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont) currently have a single House seat.

a. Some states specify different criteria for state legislative districts. a. Factor is something that state may "allow"“al ow” for consideration.

b. b. State currently only has one congressional district.

district.

Compactness and Contiguity

As a districting criterion, compactness reflects the idea that a congressional district should represent a geographicallygeographical y consolidated area.4647 Compactness of congressional districts is a requirement in 3032 states, but often, state laws do not specify precise measures of compactness.47 Generally48

General y, a compact district would tend to have smoother boundaries and might resemble a standard geometric shape more than a less compact district. In some conceptualizations, a compact district would have an identifiable "center" “center” that seems reasonably equidistant from any

of its boundaries.48

49

Federal apportionment acts between 1842 and 1911 contained a provisionprovisions requiring that congressional districts be of "“contiguous territory,"49”50 and most states have included similar language in their current redistricting laws. For a district to be contiguous, it generallygeneral y must be possible to travel from any point in the district to any other place in the district without crossing

into a different district.50

51 Preserving Political Subdivisions

Most states require that redistricting practitioners take into account existing political boundaries, such as towns, cities, or counties. In many instances, districts may not be able to be drawn in ways that encompass entire political subdivisions, given other districting standards, like

population equality, that could take precedence. Maintaining political subdivisions can also help simplify election administration by ensuring that a local election jurisdiction is not split among multiple congressional districts. Some state laws direct redistricting authorities to preserve the "core"

47 For additional background on compactness as a redistricting principle, see William Bunge, “Gerrymandering, Geography, and Grouping,” Geographical Review, vol. 56, no. 2 (April 1966), pp. 256-263; Jacob S. Siegel, “Geographic Compactness vs. Race/Ethnic Compactness and Other Criteria in the Delineation of Legislative Districts,” Population Research and Policy Review, vol. 15, no. 2 (April 1996), pp. 147 -164; Richard G. Niemi et al., “ Measuring Compactness and the Role of a Compactness Standard in a T est for Partisan and Racial Gerrymandering,” Journal of Politics, vol. 52, no. 4 (November 1990), pp. 1155 -1181; and Daniel D. Polsby and Robert D. Popper, “ The T hird Criterion: Compactness as a Procedural Safeguard Against Partisan Gerrymandering,” Yale Law and Policy Review, vol. 9, no. 2 (Spring/Summer 1991), pp. 301 -353.

48 National Conference of State Legislatures, “Redistricting Criteria,” April 23, 2019, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-criteria.aspx; for further discussion, see Aaron Kaufman, Gary King, and Mayya Komisarchik, “How to Measure Legislative District Compactness If You On ly Know It When You See It,” working paper, updated February 24, 2019, at https://gking.harvard.edu/files/gking/files/compact.pdf, pp. 1-5.

49 See “Compactness” section from Justin Levitt, “Where Are the Lines Drawn?” All About Redistricting, Loyola Law School, 2020, at http://redistricting.lls.edu/where-state.php#contiguity. 50 Historical apportionment acts can be viewed at U.S. Census Bureau, “Apportionment Legislation 1840 -1880,” History, at https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/apportionment/apportionment_legislation_1840_-_1880.html; U.S. Census Bureau, “ Apportionment Legislation 1890 -Present,” History, at https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/apportionment/apportionment_legislation_1890_-_present.html.

51 See “Contiguity” section from Justin Levitt, “Where Are the Lines Drawn?” All About Redistricting, Loyola Law School, 2020, at https://redistricting.lls.edu/redistricting-101/where-are-the-lines-drawn/#contiguity.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 19 Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

“core” of existing congressional districts; other states prohibit drawing district boundaries that

of existing congressional districts; other states prohibit drawing district boundaries that would create electoral contests between incumbent House Members.51

52 Preserving Communities of Interest

Some states include the preservation of communities of interest as a criterion in their redistricting laws. People within a community of interest generallygeneral y have a shared background or common

interests that may be relevant to their legislative representation. These recognizedrec ognized similarities may be due to shared social, cultural, historical, racial, ethnic, partisan, or economic factors. In some instances, communities of interest may naturallynatural y be preserved by following other

redistricting criteria, such as compactness or preserving political subdivisions.52

53 Promoting Political Competition; Considering Existing District or Incumbent

Some states include measures providing that districts cannot be drawn to unduly favor a particular candidate or political party. The term gerrymander originated to describe districts drawn to favor a particular political party,5354 and it is often used in this context today. Redistricting has traditionally traditional y been viewed as an inherently political process, where authorities have used partisan considerations in drawing district boundaries. Districts generallygeneral y may be drawn in a way that is politically political y advantageous to certain candidates or political parties, unless prohibited by state law.54 55

Some states, for example, expressly allowal ow the use of party identification information in the redistricting process, whereas others prohibit it; similarly, some states may allowal ow for practices to protect an incumbent or maintain the "core"“core” of an existing district, whereas other states prohibit

any practices that would favor or disfavor an incumbent or candidate.55

56

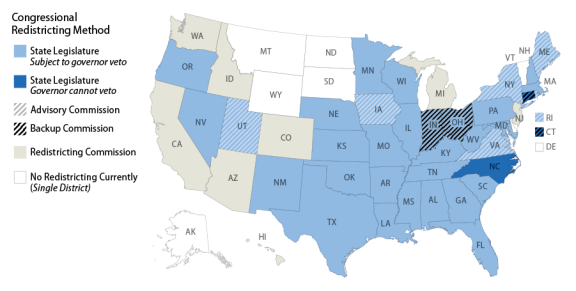

State Processes for Redistricting

Redistricting processes are fundamentallyfundamental y the responsibility of state governments under current

law and practice. Among the 4344 states with multiple House districts, a variety of approaches are taken, but generallygeneral y, states either allowal ow their state legislatures or a separate redistricting commission to determine congressional district boundaries. The map inin Figure 3 displays the

redistricting methods currently used across states.

Historically, and in the majority of states today, congressional district boundaries are primarily determined by state legislatures. Currently, 3736 states authorize their state legislatures to establish

congressional district boundaries. Most of these states enable the governor to veto a redistricting plan created by the legislature; Connecticut and North Carolina do not allowal ow a gubernatorial veto.56

Other states, in

veto.57

In recent years, other states have begun to use redistricting commissions, which may be more removed from state legislative politics.57 In eight58 In 10 states that currently have multiple congressional districts (Arizona, California, Colorado, HawaiiHawai , Idaho, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington), redistricting commissions are primarily responsible for redrawing congressional districts. In fourcongressional districts; Montana's state constitution provides for an independent redistricting commission to draw congressional district boundaries, if reapportionment results in multiple seats for the state. In five other states (Maine, New York, Rhode Island, Utah, and Virginiaand Utah), a

), a commission serves in an advisory capacity during the redistricting process. Commissions may also be used as a "backup"“backup” or alternate means of redistricting if the legislature'’s plan is not

enacted, such as in Connecticut, Indiana, and Ohio.

The composition of congressional redistricting commissions can also vary; many include members of the public selected by a method intended to be nonpartisan or bipartisan, whereas other commissions may include political appointees or elected officials, such as in Hawaii Hawai and New Jersey. A commission'’s membership, the authority granted to it, its relationship to other state government entities, and other features may affect whether a commission is perceived to be

undertaking an objective process or a more politicized one. Some proponents of redistricting commissions believe that using independent redistricting commissions can prevent opportunities

57 See “State-by-State Redistricting Procedures,” Ballotpedia, at https://ballotpedia.org//State-by-state_redistricting_procedures.

58 Wendy Underhill, “Redistricting Commissions: Congressional Plans,” National Conference of State Legislatures, April 18, 2019, at http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/redistricting-commissions-congressional-plans.aspx.

Congressional Research Service

15

Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives

for partisan gerrymandering and may create more competitive and representative districts.58 59 Others, however, believe that political considerations can remain in commission decisionmaking processes, and that the effect of redistricting methods on electoral competitiveness is overstated.59 60 For more information on redistricting commissions, see CRS Insight IN11053, Redistricting

Commissions for Congressional Districts.

The timeline for redistricting also varies across states, and can be affected by state or federal requirements regarding the redistricting process; the efficiency of the legislature, commission, or other entities involved in drawing a state'’s districts; and, potentiallypotential y, by legal or political challenges

chal enges made to a drafted or enacted redistricting plan.6061 In general, the redistricting process would usuallyusual y begin early in a year ending in "1,"“1,” once each state has learned how many seats it is entitled to under the apportionment following the decennial census.62 Many states complete the process within the next year. After the 2010 reapportionment, for example, Iowa was the first state to complete its initial congressional redistricting plan on March 31, 2011, and 31 other states completed their initial plans by the end of 2011. The remaining 11 states with multiple

congressional districts completed their initial redistricting plans by the middle of 2012, with Kansas becoming the final state to complete its initial plan on June 7, 2012.6163 Some states may redistrict multiple times between apportionments, if allowedal owed under state law or required by a legal challenge

chal enge to the preliminary redistricting.62

64

59 Katie Zezima and Emily Wax-T hibodeaux, “Voters Are Stripping Partisan Redistricting Power from Politicians in Anti-Gerrymandering Efforts,” Washington Post, November 7, 2018, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/voters-are-stripping-partisan-redistricting-power-from-politicians-in-anti-gerrymandering-efforts/2018/11/07/2a239a5e-e1d9-11e8-b759-3d88a5ce9e19_story.html; Lyle Denniston, “ Opinion Analysis: A Cure for Partisan Gerrymandering?” SCOTUSblog, June 29, 2015, at https://www.scotusblog.com/2015/06/opinion-analysis-a-cure-for-partisan-gerrymandering/. 60 For example, see Alan Abramowitz, Brad Alexander, and Matthew Gunning, “Don't Blame Redistricting for Uncompetitive Elections,” PS: Political Science and Politics, vol. 2839, no. 1 (January 2006), pp. 87-90. 61 For general historical background and an analysis of state redistricting timeline considerations, see Erik J. Engstrom, “T he Strategic T iming of Congressional Redistricting,” ch. 4 in Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of Am erican Dem ocracy (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2013), pp. 59 -79. A number of lawsuits related to redistricting following the 2010 census remain pending in 2019; see David A. Lieb, “Gerrymandering Lawsuits Are Pending in a Dozen St ates,” Associated Press, March 21, 2019, at https://apnews.com//0e7691a32c954975850de9e78b9b73cc. According to one count, lawsuits were filed in 38 states during the 2010 redistricting cycle; see “ Redistricting Lawsuits Related to the 2010 Census,” Ballotpedia, updated April 17, 2019, at https://ballotpedia.org//Redistricting_lawsuits_relating_t o_the_2010_Census.

62 T he Census Bureau announced that states will be receiving redistricting data based on the 2020 census by September 30, 2021. See James Whitehorne, “Timeline for Releasing Redistricting Data,” U.S. Census Bureau, February 12, 2021, at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2021/02/timeline-redistricting-data.html.