The Army’s Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Changes from October 10, 2019 to February 14, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Why Is This Issue Important to Congress?

- The Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) Becomes the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV)

- Report Focus on OMFV

- Preliminary OMFV Requirements

- Background

- The Army's Current Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV)

- M-2 Limitations and the Need for a Replacement

- Past Attempts to Replace the M-2 Bradley IFV

- Why the FCS and GCV Programs Were Cancelled

- FCS

- GCV

- After the Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV): The Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) Program

- Army Futures Command (AFC) and Cross-Functional Teams (CFTs)

- Army Futures Command

- Cross-Functional Teams (CFTs)

- Army's Original OMFV Acquisition Approach

- Original OMFV Acquisition Plan

- Secretary of the Army Accelerates the Program

- Army Issues OMFV Request for Proposal (RFP)

- Potential OMFV Candidates

- BAE Systems

- BAE Decides Not to Compete for the OMFV Contract

- General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS)

- Raytheon/Rheinmetall

- Army Disqualifies Raytheon/Rheinmetall Lynx Prototype

- Robotic Combat Vehicles (RCVs) and the OMFV

- Robotic Combat Vehicle–Light (RCV–L)

- Robotic Combat Vehicle–Medium (RCV–M)

- Robotic Combat Vehicle–Heavy (RCV–H)

- RCV Acquisition Approach

- OMFV, RCV, and Section 804 Middle Tier Acquisition Authority

- Concerns with Section 804 Authority

- FY2020 OMFV and RCV Budget Request

- FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act

- H.R. 2500

- Related Report Language

- S. 1790

- Related Report Language

- Department of Defense Appropriation Bill FY2020

- H.R. 2968

- S.2474

- Potential Issues for Congress

- Concerns with a Single Competitor in the OMFV EMD Phase

- The Relationship Between the OMFV and RCVs

- Section 804 Authority and the OMFV

- Army Cancels OMFV Program

- Army Restarts OMFV Program

- FY2021 OMFV Budget Request

- Potential Issues for Congress

- The Army's New OMFV Acquisition Strategy

- OMFV Program Decisionmaking Authority

Summary

In June 2018, in part due to congressional concerns, the Army announced a new modernization strategy and designated the Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) as the program to replace the M-2 Bradley. In October 2018, Army leadership decided to redesignate the NGCV as the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) and to add additional vehicle programs to what would be called the NGCV Program.

The M-2 Bradley, which has been in service since 1981, is an Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV) used to transport infantry on the battlefield and provide fire support to dismounted troops and suppress or destroy enemy fighting vehicles. Updated numerous times since its introduction, the M-2 Bradley is widely considered to have reached the technological limits of its capacity to accommodate new electronics, armor, and defense systems. Two past efforts to replace the M-2 Bradley—the Future Combat System (FCS) Program and the Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV) Program—were cancelled for programmatic and cost-associated reasons.

In late 2018, the Army established Army Futures Command (AFC), intended to establish unity of command and effort while consolidating the Army's modernization process under one roof. AFC is intended to play a significant role in OMFV development and acquisition. Hoping to field the OMFV in FY2026, the Army plans to employ Section 804 Middle Tier Acquisition Authority for rapid prototyping. The Army plans to develop, in parallel, three complementary classes of Robotic Combat Vehicles (RCVs) intended to accompany the OMFV into combat both to protect the OMFV and provide additional fire support. For RCVs to be successfully developed, technical challenges with autonomous ground navigation may need to be resolved and artificial intelligence likely must evolve to permit the RCVs to function as intended. The Army has stated that a new congressionally granted acquisition authority—referred to as Section 804 authority—might also be used in RCV development.

The Army requested $219 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funding for the OMFV program and $160 million in RDT&E funding for the RCV in its FY2020 Budget Request.

FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2500) authorizes an additional $ 6 million for OMFV RDT&E. H.R. 2500 also authorizes an additional $10 million for RCV RDT&E. FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1790) authorizes an additional $15 million for OMFV RDT&E. S. 1790 also authorizes an additional $25 million for RCV RDT&E.

The Department of Defense Appropriation Act, 2020 (H.R. 2968), appropriates an additional $32 million for OMFV RDT&E. H.R. 2968 appropriates an additional $55 million for RCV RDT&E. S. 2474 appropriates an additional $26 million for OMFV RDT&E. S. 2474 decreases the RCV RDT&E funding by $46.621 million.

Potential issues for Congress include the following:

- Concerns with a Single Competitor in the OMFV Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) Phase.

- What is the relationship between the OMFV and RCVs?

- What are some of the benefits and concerns regarding Section 804 authority and the OMFV?

On March 29, 2019, the Army issued a Request for Proposal (RFP) to industry for the OMFV. The Army characterized its requirements as "aggressive" and noted industry might not be able to meet all requirements.

On January 16, 2020, the Army canceled the current OMFV program, intending to restart the program following an analysis and revision of program requirements. According to Army officials, "a combination of requirements and schedule overwhelmed industry's ability to respond within the Army's timeline."

On February 7, 2020, the Army reopened the OMFV competition by releasing a new market survey with a minimally prescriptive wish list and an acquisition strategy that shifted most of the initial cost burden to the Army.

The Army requested $327.732 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funding for the OMFV program in its FY2021 budget request.

Potential issues for Congress include the Army's new OMFV Acquisition Strategy and OMFV program decisionmaking authority.

Why Is This Issue Important to Congress?

The Army's Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) is the Army's third attempt to replace the M-2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV) which has been in service since the early 1980s. Despite numerous upgrades since its introduction, the Army contends the M-2 is near the end of its useful life and can no longer accommodate the types of upgrades needed for it to be effective on the modern battlefield.

Because the OMFV would be an important weapon system in the Army's Armored Brigade Combat Teams (ABCTs), Congress may be concerned with how the OMFV would impact the effectiveness of ground forces over the full spectrum of military operations. Moreover, Congress might also be concerned with how much more capable the OMFV is projected to be over the M-2 Bradley to ensure that it is not just a costly marginal improvement over the current system. A number of past unsuccessful Army acquisition programs have served to heighten congressional oversight of Army programs, and the OMFV may be subject to a high degree of congressional interest. In addition to these primary concerns, how the Army plans to use the new congressionally granted Section 804 Middle Tier Acquisition Authority as well as overall program affordability could be potential oversight issues for Congress.

The Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) Becomes the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV)

In June 2018, the Army established the Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) program to replace the M-2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV), which has been in service since the early 1980s. In October 2018, Army leadership reportedly decided to redesignate the NGCV as the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) and add additional vehicle programs to what would be called the NGCV Program.1 Under the new NGCV Program, the following systems are planned for development:

- The Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV): the M-2 Bradley IFV replacement.

- The Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV):2 the M-113 vehicle replacement.

- Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF):3 a light tank for Infantry Brigade Combat Teams (IBCTs).

- Robotic Combat Vehicles (RCVs): three versions, Light, Medium, and Heavy.

- The Decisive Lethality Platform (DLP): the M-1 Abrams tank replacement.

Two programs—AMPV and MPF—are in Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) and Prototype Development, respectively. Reportedly, the AMPV and MPF programs, which were overseen by Program Executive Office (PEO) Ground Combat Systems, will continue to be overseen by PEO Ground Combat Systems, but the NGCV Cross Functional Team (CFT) will determine their respective operational requirements and acquisition schedule.4

Report Focus on OMFV

Because AMPV and MPF are discussed in earlier CRS reports and the OMFV is in the early stages of development, the remainder of this report focuses on the OMFV and associated RCVs. Because the DLP is intended to replace the Army's second major ground combat system—the M-1 Abrams Tank—it will be addressed in a separate CRS report in the future.

Preliminary OMFV Requirements5

4

The Army's preliminary basic operational requirements for the OMFV includeincluded the following:

- Optionally manned. It must have the ability to conduct remotely controlled operations while the crew is off-platform.

65

- Capacity. It should eventually operate with no more than two crewmen and possess sufficient volume under armor to carry at least six soldiers.

- Transportability. Two OMFVs should be transportable by one C-17 and be ready for combat within 15 minutes.

- Dense urban terrain operations and mobility. Platforms should include the ability to super elevate weapons and simultaneously engage threats using main gun and an independent weapons system.

- Protection. It must possess requisite protection to survive on the contemporary and future battlefield.

- Growth. It should possess sufficient size, weight, architecture, power, and cooling for automotive and electrical purposes to meet all platform needs and allow for preplanned product improvements.

- Lethality. It should apply immediate, precise, and decisively lethal extended range medium-caliber, directed energy, and missile fires in day/night/all-weather conditions, while moving and/or stationary against moving and/or stationary targets. The platform should allow for mounted, dismounted, and unmanned system target handover.

- Embedded platform training. It should have embedded training systems that have interoperability with the Synthetic Training Environment.

- Sustainability. Industry should demonstrate innovations that achieve breakthroughs in power generation and management to obtain increased operational range and fuel efficiency, increased silent watch, part and component reliability, and significantly reduced sustainment burden.

Additional requirements includeincluded the capacity to accommodate7

- 6reactive armor,

- an Active Protection System (APS),

- artificial intelligence,

87 and Directeddirected-energy weapons98 and advanced target sensors.

Background

The Army's Current Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV)

The M-2 Bradley is an Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV) used to transport infantry on the battlefield and provide fire support to dismounted troops and suppress or destroy enemy fighting vehicles. The M-2 has a crew of three—commander, gunner, and driver—and carries seven fully equipped infantry soldiers. M-2 Bradley IFVs are primarily found in the Army's Armored Brigade Combat Teams (ABCT). The first M-2 prototypes were delivered to the Army in December 1978, and the first delivery of M-2s to units started in May 1981. The M-2 Bradley has been upgraded often since 1981, and the Army reportedly plans to undertake an upgrade to the M-2A4 version.10.9

M-2 Limitations and the Need for a Replacement

Despite numerous upgrades over its lifetime, the M-2 Bradley has what some consider a notable limitation. Although the M-2 Bradley can accommodate seven fully equipped infantry soldiers, infantry squads consist of nine soldiers. As a result, "each mechanized [ABCT] infantry platoon has to divide three squads between four Bradleys, meaning that all the members of a squad are not able to ride in the same vehicle."1110 This limitation raises both command and control and employment challenges for Bradley-mounted infantry squads and platoons.

The M-2 Bradley first saw combat in 1991 in Operation Desert Storm, where its crews were generally satisfied with its performance.1211 The M-2's service in 2003's Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) was also considered satisfactory. However, reports of vehicle and crew losses attributed to mines, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and anti-tank rockets—despite the addition of reactive armor1312 to the M-2—raised concerns about the survivability of the Bradley.1413

Furthermore, the M-2 Bradley is reportedly reaching the technological limits of its capacity to accommodate new electronics, armor, and defense systems.1514 By some accounts, M-2 Bradleys during OIF routinely had to turn off certain electronic systems to gain enough power for anti-roadside-bomb jammers. Moreover, current efforts to mount active protection systems (APS)16Active Protection Systems (APS)15 on M-2 Bradleys to destroy incoming anti-tank rockets and missiles are proving difficult.1716 Given its almost four decades of service, operational limitations, demonstrated combat vulnerabilities, and difficulties in upgrading current models, many argue the M-2 Bradley is a candidate for replacement.

Past Attempts to Replace the M-2 Bradley IFV

The Army has twice attempted to replace the M-2 Bradley IFV—first as part of the Future Combat System (FCS) Program,1817 which was cancelled by the Secretary of Defense in 2009, and second with the Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV) Program,1918 cancelled by the Secretary of Defense in 2014. These cancellations, along with a series of high-profile studies, such as the 2011 Decker-Wagner Army Acquisition Review, have led many to call into question the Army's ability to develop and field ground combat systems.

Why the FCS and GCV Programs Were Cancelled

FCS

Introduced in 1999 by Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki, FCS was envisioned as a family of networked, manned and unmanned vehicles, and aircraft for the future battlefield. The Army believed that advanced sensor technology would result in total battlefield awareness, permitting the development of lesser-armored combat vehicles and the ability to engage and destroy targets beyond the line-of-sight. However, a variety of factors led to the program's cancellation, including a complicated, industry-led management approach; the failure of a number of critical technologies to perform as envisioned; and frequently changing requirements from Army leadership—all of which resulted in program costs increasing by 25%.2019 After $21.4 billion already spent2120 and the program only in the preproduction phase, then Secretary Gates restructured the program in 2009, effectively cancelling it.22

GCV23

22

Recognizing the need to replace the M-2 Bradley, as part of the FCS "restructuring," the Army was directed by the Secretary of Defense in 2009 to develop a ground combat vehicle (GCV) that would be relevant across the entire spectrum of Army operations, incorporating combat lessons learned in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2010, the Army, in conjunction with the Pentagon's acquisition office, conducted a review of the GCV program to "review GCV core elements including acquisition strategy, vehicle capabilities, operational needs, program schedule, cost performance, and technological specifications." This review found that the GCV relied on too many immature technologies, had too many performance requirements, and was required by Army leadership to have too many capabilities to make it affordable. In February 2014, the Army recommended terminating the GCV program and redirecting the funds toward developing a next-generation platform.2423 The cost of GCV cancellation was estimated at $1.5 billion.2524

After the Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV): The Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) Program

In the aftermath of the GCV program, the Army embarked on a Future Fighting Vehicle (FFV) effort in 2015. Army officials—described as "cautious" and "in no hurry to initiate an infantry fighting vehicle program"—instead initiated industry studies to "understand the trade space before leaping into a new program."2625 In general, Army combat vehicle modernization efforts post-FCS have beenwere characterized as upgrading existing platforms as opposed to developing new systems. This was due in part to reluctance of senior Army leadership, but also to significant budgetary restrictions imposed on the Army during this period. Some in Congress, however, were not pleased with the pace of Army modernization, reportedly noting the Army was "woefully behind on modernization" and was "essentially organized and equipped as it was in the 1980s."2726 In June 2018, in part due to congressional concerns, the Army announced a new modernization strategy and designated NGCVsthe NGCV as the second of its six modernization priorities.2827 Originally, the NGCV was considered the program to replace the M-2 Bradley. Development of the NGCV would be managed by the Program Executive Officer (PEO) Ground Combat Systems, under the Assistant Secretary of the Army (ASA), Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology (ALT).

Army Futures Command (AFC) and Cross-Functional Teams (CFTs)

Army Futures Command29

28

In November 2017, the Army established a Modernization Task Force to examine the options for establishing an Army Futures Command (AFC) that would establish unity of command and effort as the Army consolidated its modernization process under one roof. Formerly, Army modernization activities were primarily spread among Forces Command (FORSCOM), Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), Army Materiel Command (AMC), Army Test and Evaluation Command (ATEC), and the Army Deputy Chief of Staff G-8.3029 Intended to be a 4-star headquarters largely drawn from existing Army commands, AFC was planned to be established in an urban environment with ready access to academic, technological, and industrial expertise. On July 13, 2018, the Army announced that AFC would be headquartered in Austin, TX, and that it had achieved initial operating capability on July 1, 2018. AFC reached full operational capability on July 31, 2019.31 30 Sub-organizations, many of which currently resideresided within FORSCOM, TRADOC, and AMC, are to transition to AFC, but there are no plans to physically move units or personnel from these commands at the present timewere transitioned to AFC.

Cross-Functional Teams (CFTs)

Army Futures Command intends to use what it calls Cross-Functional Teams (CFT) as part of its mission, which includes the development of NGCV. As a means to "increase the efficiency of its requirements and technology development efforts, the Army established cross-functional team pilots for modernization" in October 2017.3231 These CFTs are intended to

- leverage expertise from industry and academia;

- identify ways to use experimentation, prototyping, and demonstrations; and

- identify opportunities to improve the efficiency of requirements development and the overall defense systems acquisition process.

33

32The eight CFTs are

- Long Range Precision Fires at Ft. Sill, OK;

- Next Generation Combat Vehicle at Detroit Arsenal, MI;

- Future Vertical Lift at Redstone Arsenal, AL;

- Network Command, Control, Communication, and Intelligence at Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD;

- Assured Positioning, Navigation and Timing at Redstone Arsenal, AL;

- Air and Missile Defense at Ft. Sill, OK;

- Soldier Lethality at Ft. Benning, GA; and

- Synthetic Training Environment in Orlando, FL.

34

33CFTs are to be a part of AFC. Regarding the NGCV, program acquisition authority is derived from Assistant Secretary of the Army (ASA) for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology (ALT), who is also the senior Army Acquisition Executive (AAE), to whom the Program Executive Officers (PEOs) report. AFC is to be responsible for requirements and to support PEOs. The NGCV Program Manager (PM), who is subordinate to PEO Ground Combat Systems, is to remain under the control of ASA (ALT) but are to be teamed with CFTs under control of the AFC.3534 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) notes, however

Army Futures Command has not yet established policies and procedures detailing how it will execute its assigned mission, roles, and responsibilities. For example, we found that it is not yet clear how Army Futures Command will coordinate its responsibilities with existing acquisition organizations within the Army that do not directly report to it. One such organization is the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics and Technology [ASA (ALT)]—the civilian authority responsible for the overall supervision of acquisition matters for the Army—and the acquisition offices it oversees.3635

The Army's explanation of how the NGCV program is to be administered and managed, along with GAO's findings regarding AFC not yet having established policies and procedures, suggests a current degree of uncertainty as to how the NGCV program willwas to be managed.

Army's Original OMFV Acquisition Approach37

36

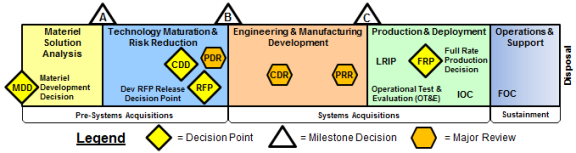

Figure 1 depicts the Department of Defense (DOD) Systems Acquisition Framework, which illustrates the various phases of systems development and acquisitions and is applicable to the procurement of Army ground combat systems.

|

|

Source: http://acqnotes.com/acqnote/acquisitions/acquisition-process-overview, accessed February 13, 2019. Notes: Each phase of the acquisition process has specific DOD regulations and federal statutes that must be met. At the end of each phase, there is a Milestone Review (A, B, C) to determine if the acquisition program has met these required regulations and statues to continue on into the next phase. Critical Development Document (CDD): The CDD specifies the operational requirements for the system that will deliver the capability that meets operational performance criteria specified in the Initial Capabilities Document (ICD). Preliminary Design Review (PDR): The PDR is a technical assessment that establishes the Allocated Baseline of a system to ensure a system is operationally effective. Request for Proposal (RFP): A RFP is a document that solicits proposal, often made through a bidding process, by an agency or company interested in procurement of a commodity, service, or valuable asset, to potential suppliers to submit business proposals. Critical Design Review (CDR): A CDR is a multi-disciplined technical review to ensure that a system can proceed into fabrication, demonstration, and test and can meet stated performance requirements within cost, schedule, and risk. Production Readiness Review (PRR): The PRR assesses a program to determine if the design is ready for production. |

Original OMFV Acquisition Plan

Reportedly, the original OMFV plan called for five years of Technology Development, starting in FY2019, and leading up to a FY2024 Milestone B decision to move the program into the Engineering and Manufacturing Development phase.3837 If the Engineering and Manufacturing Development phase proved successful, the Army planned for a Milestone C decision to move the program into the Production and Deployment phase in FY2028, with the intent of equipping the first unit by FY2032.39

Secretary of the Army Accelerates the Program

In April 2018, then-Secretary of the Army Mark Esper, noting that industry could deliver OMFV prototypes by FY2021, reportedly stated he wanted to accelerate the OMFV timeline.4039 After examining a number of possible courses of action, the Army reportedly settled on a timeline that would result in an FY2026 fielding of the OMFV.4140 This being the case, the Army reportedly willwould pursue a "heavily modified off-the-shelf model meaning a mature chassis and turret integrated with new sensors."4241 Reportedly, some Army officials suggested they would likehave liked to see a 50 mm cannon on industry-proposed vehicles.4342 Under this new acquisition approach, the Army plansplanned to

- award up to two vendors three-year Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) contracts in the first quarter of FY2020;

- if EMD is successful, make a Milestone C decision to move the program into the Production and Development phase in the third quarter of FY2023; and

- equip first units in the first quarter of FY2026.

44

43Army Issues OMFV Request for Proposal (RFP)45

44

On March 29, 2019, the Army issued a Request for Proposal (RFP)4645 to industry for the OMFV. The Army has characterized its requirements as "aggressive" and notesnoted industry might not be able to meet all requirements. Major requirements call forincluded the ability to transport two OMFVs in a C-17 aircraft which will likely require the vehicle to have the ability to accommodate add-on armor; a threshold (minimum) requirement for a 30 mm cannon and a second generation forward-looking infra-red radar (FLIR); and objective (desired) requirements for a 50 mm cannon and a third generation FLIR. By October 1, 2019, industry is to bewas required to submit prototype vehicles to the Army for consideration and in the second quarter of FY2020, the Army planned to select two vendors to build 14 prototypes for further evaluation.

Potential OMFV Candidates

Reportedly, the Army planned eventuallyoriginally planned to award a production contract for up to 3,590 OMFVs to a single vendor.4746 Although the Army reportedly expected five to seven vendors to compete for the OMFV EMD contract, three vendors showcased prospective platforms in the fall of 2018.48

BAE Systems

BAE Systems was proposinghad proposed its fifth-generation CV-90. The CV-90 was first fielded in Europe in the 1990s. The latest version mountsmounted a 35 mm cannon provided by Northrop Grumman that can accommodate 50 mm munitions. The CV-90 also featuresfeatured the Israeli IMI Systems Iron Fist active protection system (APS), which is currently being tested on the M-2 BradleyActive Protection System (APS). The CV-90 cancould accommodate a three-person crew and five infantry soldiers.

|

|

Source: https://www.baesystems.com/en-us/product/cv90, accessed January 31, 2019. |

BAE Decides Not to Compete for the OMFV Contract49

48

On June 10, 2019, BAE reportedly announced it would not compete for the OMFV contract suggesting the requirements and acquisition schedule "did not align with our current focus or developmental; priorities."50 Reportedly, BAE does plan to participate in the Army's Robotic Combat Vehicle Program (RCV) (see next section).

General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS)

GDLS is proposingproposed its Griffin III technology demonstrator, which usesused the British Ajax scout vehicle chassis. The Griffin III mountsmounted a 50 mm cannon and cancould accommodate an APS and host unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The Griffin II cancould accommodate a two-person crew and six infantry soldiers.

|

|

Source: Sydney J. Freedberg, "General Dynamics Land Systems Griffin III for U.S. Army's Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV)," October 8, 2018. |

Raytheon/Rheinmetall

Raytheon/Rheinmetall was proposingproposed its Lynx vehicle. It cancould mount a 50 mm cannon and thermal sights, and cancould accommodate both APS and UAVs. Raytheon states that the Lynx can accommodate a nine-soldier infantry squad.5150

Army Disqualifies Raytheon/Rheinmetall Lynx Prototype52

51

Reportedly, the Army disqualified the Raytheon/Rheinmetall bid because it failed to deliver a single OMFV prototype by October 1, 2019, as stipulated in the RFP, meaning only a single vendor—General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS)—iswas left to compete for the EMD contract. Supposedly, Rheinmetall was unable to ship its Lynx prototype from Germany (although Rheinmetall shipped it to the United States in 2018) and asked the Army for a four-week extension so it could ship the vehicle to Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland or, if that was not acceptable, arrange for the Army to take possession of the vehicle in Germany instead. Both requests by Rheinmetall were reportedly denied by the Army. Reportedly, the Army Acquisition Authority —the ASA (ALT)—was willing to grant a four-week extension, but Army Futures Command (AFC) insisted the Army adhere to the October 1, 2019, deadline.53

Reportedly, a number of companies were interested in competing and submitting bids for the OMFV EMD contract but expressed concerns to the Army that meeting its requirements and timelines was not possible, askingwould not be possible and asked for extensions so they could submit bids. Some in industry reportedly had expressed their concerns to Army leadership that it would be difficult to meet approximately 100 mandatory vehicle requirements with a nondevelopmental vehicle prototype in the 15 months allotted.5453

|

|

Source: https://www.rheinmetall-defence.com/en/rheinmetall_defence/systems_and_products/vehicle_systems/armoured_tracked_vehicles/lynx/index.php, accessed January 31, 2019. |

Robotic Combat Vehicles (RCVs) and the OMFV

As part of the revised NGCV Program, the Army plans to develop three RCV variants: Light, Medium, and Heavy. The Army reportedly envisions employing RCVs as "scouts" and "escorts" for manned OMFVs.55 RCVs could precede OMFVs into battle to deter ambushes and could be used to guard the flanks of OMFV formations.56 Initially, RCVs would be controlled by operators riding in NGCVs, but the Army hopes that improved ground navigation technology and artificial intelligence will permit a single operator to control multiple RCVs.57 The following sections provide a brief overview of each variant.58

Robotic Combat Vehicle–Light (RCV–L)

|

|

Source: The Army's Robotic Combat Vehicle Campaign Plan, January 16, 2019. |

The RCV–L is to be less than 10 tons, with a single vehicle capable of being transported by rotary wing assets. It should be able to accommodate an anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) or a recoilless weapon. It is also expected to have a robust sensor package and be capable of integration with UAVs. The RCV–L is considered to be "expendable."

Robotic Combat Vehicle–Medium (RCV–M)

|

|

Source: The Army's Robotic Combat Vehicle Campaign Plan, January 16, 2019. |

The RCV–M is to be between 10 to 20 tons, with a single vehicle capable of being transported by a C-130 aircraft. It should be able to accommodate multiple ATGMs, a medium cannon, or a large recoilless cannon. It is also expected to have a robust sensor package and be capable of integration with UAVs. The RCV–M is considered to be a "durable" system and more survivable than the RCV–L.

Robotic Combat Vehicle–Heavy (RCV–H)

|

|

Source: The Army's Robotic Combat Vehicle Campaign Plan, January 16, 2019. |

The RC–H is to be between 20 to 30 tons, with two vehicles capable of being transported by a C-17 aircraft. It is also expected to be able to accommodate an onboard weapon system capable of destroying enemy IFVs and tanks. It should also have a robust sensor package and be capable of integration with UAVs. The RCV–H is considered to be a "nonexpendable" system and more survivable than the other RCVs.

RCV Acquisition Approach

Reportedly, the Army does not have a formal acquisition approach for the RCV, but it plans to experiment from FY2020 to FY2023 with human interface devices and reconnaissance and lethality technologies.59 Reportedly, the Army plans to issue prototype contracts in November 2019.60 Depending on the outcome of experimentation with prototypes, the Army expects a procurement decision in FY2023.61 Reportedly, the Army plans to request white papers and prototype proposals for the RCV-L in June 2019, evaluate the white papers and select highly qualified offerors to participate in a second stage where RFPs are issued.62

OMFV, RCV, and Section 804 Middle Tier Acquisition Authority

Section 804 of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2016 (P.L. 114-92) provides authority63 to the Department of Defense (DOD) to rapidly prototype and/or rapidly field capabilities outside the traditional acquisition system. Referred to as "804 Authority," it is intended to deliver a prototype capability in two to five years under two distinct pathways: Rapid Prototyping or Rapid Fielding. One of the potential benefits of using 804 Authority is that the services can bypass the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) and the Joint Capabilities Integration Development Systems (JCIDS), two oversight bodies that, according to some critics, slow the acquisition process.64 Under Rapid Prototyping, the objectives are to

- field a prototype that can be demonstrated in an operational environment, and

- Provide for residual operational capability within five years of an approved requirement.

Under Rapid Fielding, the objectives are to

- begin production within six months, and

- Complete fielding within five years of an approved requirement.

For the OMFV program, the Army reportedly plans to use Rapid Prototyping under Section 804 to permit the program to enter at the EMD Phase, thereby avoiding a two- to three-year Technical Maturation Phase.65 Regarding the RCV program, the Army's Robotic Campaign Plan indicates that Section 804 authority is an "option" for RCV development.66

Concerns with Section 804 Authority

While many in DOD have embraced the use of Section 804 authority, some have expressed concerns. Supporters of Section 804 authority contend that provides "an alternative path for systems that can be fielded within five years or use proven technologies to upgrade existing systems while bypassing typical oversight bodies that are said to slow the acquisition process."67 Critics, however, argue that "new rapid prototyping authorities won't eliminate the complexities of technology development."68 One former Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, Frank Kendall, reportedly warns

What determines how long a development program takes is the product. Complexity and technical difficulty drive schedule. That can't be wished away. Requirements set by operators drive both complexity and technical difficulty. You have to begin there. It is possible to build some kinds of prototypes quickly if requirements are reduced and designs are simplified. Whether an operator will want that product is another question. It's also possible to set totally unrealistic schedules and get industry to bid on them. There is a great deal of history that teaches us that this is a really bad idea.69

Others contend that for this authority to work as intended, "maintaining visibility of 804 prototyping would be vital to ensure the authority is properly used" and that "developing a data collection and analytical process will enable DOD to have insight into how these projects are being managed and executed."70 In this regard, congressional oversight of programs employing Section 804 authority could prove essential to ensuring a proper and prudent use of this congressionally authorized authority.

FY2020 OMFV and RCV Budget Request71

The Army requested $219.047 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funding for the OMFV program and $160.035 million in RDT&E funding for the RCV in its FY2020 budget request. In terms of the OMFV, funding is planned to be used for, among other things, maturing technological upgrades for integration into the vehicle, including nondevelopmental active protection systems (APS), the XM 913 50 mm cannon, and the 3rd Generation Forward Looking Infrared Radar (FLIR). FY2020 funding for RCVs is planned for finishing building prototypes of surrogate platforms and conducting manned-unmanned teaming evaluations.

FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act

H.R. 250072

H.R. 2500 would authorize an additional $ 6 million for OMFV RDT&E for structural thermoplastics.73 H.R. 2500 also would authorize an additional $10 million for RCV RDT&E for hydrogen fuel cells.74

Related Report Language

TOW 2B Missile System75

The committee is aware that the Army is developing the next version of its TOW 2B tactical missile system that will serve as the primary anti-armor weapon for the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) program. The committee also understands that the Army wants to accelerate development and fielding of the OMFV, but it is not clear that the development and fielding schedule for the new TOW 2B missile is aligned with the schedule for OMFV.

Accordingly, the committee directs the Secretary of the Army to provide a briefing to the House Committee on Armed Services by February 3, 2020, on the current plans for development and fielding of the TOW 2B missile, including how the Army will synchronize the availability of a new TOW 2B missile with fielding of the OMFV.

Briefing on Secure Communications with Remote-Piloted and Unmanned Ground Vehicles76

The committee is aware that the Army is developing new ground combat vehicles that can be operated remotely or unmanned. At the same time, potential adversaries continue to develop capabilities that may compromise control of these remotely operated systems, as well as other components of the Army's communications networks.

The committee notes the Army is researching technologies that will protect and harden communication networks in contested environments, but is concerned about the integration of these systems relative to the maturity of remotely piloted vehicles like the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle and the Robotic Combat Vehicle.

Therefore, the committee directs the Secretary of the Army to provide a briefing to the House Committee on Armed Services by September 30, 2019, on the Army's efforts to develop technologies that will protect control of remotely piloted or unmanned vehicles, as well as other communications technologies, while operating in contested environments.

Carbon Fiber Wheels and Graphitic Foam for Army Vehicles77

The committee notes the evolution of the Army's testing and evaluation of Lightweight Metal Matrix Composite Technology as outlined in the report by the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology submitted to the congressional defense committees in accordance with the committee report accompanying the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (S.Rept. 115-262).

The Army's report makes clear that its interest with respect to new materials for lightweight wheels and associated brake systems has transitioned to a more viable dual-use carbon fiber and graphite byproduct suitable for brake pads and liners throughout the tactical wheeled vehicle fleet.

The committee encourages the Army to continue to develop, prototype, and test affordable mesophase pitch carbon fiber and graphitic carbon foam components for the Next Generation Combat Vehicle and the tactical wheeled vehicle fleet to confirm their potential to reduce vehicle weight and improve fuel consumption and payload capacity over standard aluminum and steel designs. Accordingly, the committee directs the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology to provide a briefing to the House Committee on Armed Services not later than November 29, 2019, on the progress of the Army's development and testing efforts related to mesophase pitch carbon fiber and graphitic carbon foam vehicle components.

Modeling and Simulation for Ground Vehicle Development78

The committee notes that modeling and simulation (M&S) has demonstrated its utility as a tool for vehicle technology development by providing program managers with necessary information related to reliability and performance challenges in advance of making significant investment decisions for future development. The committee also notes that M&S is particularly relevant in the development of unmanned vehicle systems that could use artificial intelligence.

As the Army continues to modernize its ground combat and tactical vehicle systems, the committee encourages maximization of M&S to realize potential savings in experimentation and prototyping, predict and control program costs and, where possible, accelerate the speed of development and fielding of new ground vehicle capabilities.

Therefore, the committee directs the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology to provide a briefing to the House Committee on Armed Services no later than December 1, 2019 on how M&S is being incorporated into the development of next generation combat vehicles to include the Optionally-Manned Fighting Vehicle and Robotic Combat Vehicle programs, as well as identify any barriers and challenges that may exist regarding the full utilization of M&S for ground combat and tactical vehicle development.

Section 237—Quarterly Updates on the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle Program79

This section would require the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology to provide quarterly briefings, beginning October 1, 2019, to the congressional defense committees on the status and progress of the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle program.

S. 179080

S. 1790 would authorize an additional $15 million for OMFV RDT&E to support operational energy development and testing. S. 1790 also would authorize an additional $25 million for RCV RDT&E with $ 5 million for ground vehicle sustainment research and $20 million for hydrogen fuel cell propulsion and autonomous driving controls.

Related Report Language

Carbon Fiber Wheels and Graphitic foam for Next Generation Combat Vehicle81

The committee recognizes the recent effort related to Metal Matrix Composite (MMC) technologies and is encouraged by the U.S. Army Ground Vehicle Systems Center's (GVSC) decision to transition into lower-cost, wider application carbon fiber composite wheels and graphitic carbon foam research to support the Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV). Carbon fiber wheels may re- duce vehicle weight, reduce fuel consumption, increase payload capacity, and extend service life for the NGCV. Graphitic Carbon Foam may also reduce vehicle heat signatures and improve heat dissipation from engine and electronics compartments and protect against blast energy, directed energy weapons, and electromagnetic pulse threats. Finally, these products lend themselves to be produced at remote locations with additive manufacturing processes in support of NGCV operation and maintenance.

The Defense Logistics Agency has designated both graphite and carbon fiber as strategic materials. The committee notes that the GVSC has identified low-cost mesophase pitch as a United States- based source of graphite that can be used to produce carbon fiber, graphitic carbon foam, and battery technologies for the NGCV. The committee acknowledges the versatility and broad application that carbon fiber technology provides for the armed services by reducing the weight of parts by over 50% as compared to traditional steel components.

The committee recommends that the GVSC continue to develop, test, and field low-cost mesophase pitch carbon fiber and graphitic carbon foam components that can reduce vehicle weight, reduce fuel consumption, increase payload capacity, extend service life, improve survivability, and utilize additive manufacturing technology for the NGCV program.

Next Generation Combat Vehicle Technology82

The budget request included $219.0 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E), Army, for PE 62145A Next Generation Combat Vehicle Technology.

The Department of Defense faces growing challenges in providing increasingly efficient operational energy, when and where it is needed to meet the demands of the National Defense Strategy. The committee understands that the Energy Storage and Power Systems incorporate composite flywheel-based technology and may address several energy objectives for the Army, such as: (1) Increased power efficiencies; (2) Maximized use of renewables; (3) Reduced system energy consumption with improved size, weight, and power; (4) Extended operational duration, reducing the need for energy resupply; and (5) Enhanced environmental characteristics.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $15.0 million in RDT&E, Army, for PE 62145A.

Ground Vehicle Sustainment Research83

The budget request included $160.0 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E), Army, for PE 63462A Next Generation Combat Vehicle Advanced Technology Development. The committee notes the potential for using emerging additive manufacturing techniques for on-demand production of replacement parts, in both depot repair and deployed environments.

The committee notes that more work remains to be done to improve these manufacturing techniques, understand the materials being produced by these techniques, and ensure that the materials meet all safety and reliability standards.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $5.0 million in RDT&E, Army, for PE 63462A for ground vehicle sustainment research on the use of additive manufacturing for advanced technology development.

Next Generation Combat Vehicle Advanced Technology for Fuel Cell Propulsion and Autonomous Driving Control84

The budget request included $160.0 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E), Army, for PE 63462A Next Generation Combat Vehicle Advanced Technology.

The committee notes the importance of hydrogen fuel cell propulsion and autonomous driving control and encourages the Department of Defense to continue research in this area to maintain a military advantage.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $20.0 million in RDT&E, Army, for PE 63462A for advanced technology development in fuel cell propulsion and autonomous driving control.

Next Generation Combat Vehicle 50mm Gun85

The budget request included $378.4 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E), Army, for PE 65625A Manned Ground Vehicle.

The Army also identified a shortfall in funding of $40.0 million in RDT&E, Army, for PE 65625A on the unfunded priority list for the procurement of 15 XM–913 weapon systems (50mm gun, ammunition handling system, and fire control hardware).

The committee acknowledges the need to improve lethality for the Next Generation Combat Vehicle to retain overmatch in support of the National Defense Strategy and the need to field weapon systems that improve standoff and survivability.

Therefore, the committee recommends an increase of $40.0 million in RDT&E, Army, for PE 65625A for 50mm gun upgrades.

Department of Defense Appropriation Bill FY2020

H.R. 296886

H.R. 2968 would appropriate an additional $32 million for OMFV RDT&E allocated as follows:

- A decrease of $2 million for program under execution.

- Additional $10 million for prototyping energy smart autonomous ground systems.

- Additional $5 million for high performance polymers.

- Additional $5 million for highly electrified vehicles.

- Additional $5 million for composite flywheel technology.

- Additional $3 million for additive metals manufacturing.

- Additional $3 million for Rocket Propelled Grenade (RPG) and Improvised Explosive Device (IED) protection.

- Additional $3 million for modeling and simulation.

H.R. 2968 would appropriate an additional $55 million for RCV RDT&E allocated as follows:

- Additional $20 million for additive manufacturing for jointless hull.

- Additional $10 million for carbon fiber and graphite foam technology.

- Additional $10 million for hydrogen fuel cells.

- Additional $5 million for ATE5.2 engine development.

- Additional $5 million for additive manufacturing of critical components.

- Additional $5 million for advanced water harvesting technology.

S. 247487

S. 2474 would appropriate an additional $26 million for OMFV RDT&E as follows:

- Additional $ 6 million for thermoplastics.

- Additional $10 million for advanced materials development for survivability.

- Additional $10 million for autonomous vehicle mobility.

S. 2474 decreases RCV RDT&E funding by $46.621 million as follows:

- A decrease of $15.780 million for RCV Phase 2 due to excess growth.

- A decrease of $3.726 million for RCV Phase 2 due to test funding ahead of need.

- A decrease of $27.115 million for RCV Phase 3 due to funding ahead of need.

Potential Issues for Congress

Concerns with a Single Competitor in the OMFV EMD Phase

With General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS) the only vendor to submit a prototype to the Army by October 1, 2019, as required, it appears they may be awarded the Army's (EMD) contract by default. While this might be legal under the provisions of the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS),88 there are potential associated issues that policymakers might examine. While the Army reportedly notes companies that did not participate in EMD can submit bids for the production contract scheduled to be awarded in 2023, these companies will be required to develop their candidate vehicles at their own expense and would not receive the feedback that GDLS will get from the Army as their prototype proceeds through EMD.89

As previously noted, some in industry interested in participating in the OMFV EMD competition felt the number of Army requirements for a nondevelopmental vehicle and the Army's aggressive timeline were unrealistic. It has been suggested by some defense analysts that this could limit innovation, possibly resulting in only a marginal improvement over the current Bradley fighting vehicle.90 One potential course of action to avoid this possibility could be to review industry concerns to see if an adjustment in program timelines might result in additional EMD candidates.

Another possible issue are the OMFV program management roles of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (ASA) for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology (ALT)—the senior Army Acquisition Executive (AAE)—and the Army Futures Command (AFC). Reportedly, AFC's desire to adhere to the program schedule prevailed over the Army acquisition communities' desire to grant a four-week extension to Raytheon/Rheinmetall to ship its prototype to the United States for evaluation.91 In this regard, policymakers might request a clarification of the roles that the Assistant Secretary of Army (ASA) for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology (ALT) and Army Futures Command (AFC) are expected to play in OFMV program management—particularly in terms of program decision authority.

The Relationship Between the OMFV and RCVs

As previously noted, the Army envisions employing RCVs as "scouts" and "escorts" for manned OMFVs. In addition to enhancing OMFV survivability, RCVs could potentially increase the overall lethality of ABCTs. Army leadership has stated that the Army's first priority is replacing the Bradley with the OMFV, that the RCV will mature on a longer timeline than the OMFV, and that the OMFV will later be joined by the RCV.92

Given technological challenges, particularly autonomous ground navigation and artificial intelligence improvement,93 the Army's vision for RCV may not be achievable by the planned FY2026 fielding date or for many years thereafter. The Army describes the OMFV and RCV as "complementary" systems,94 but a more nuanced description of both the systematic and operational relationship between the two could be beneficial. While the OMFV appears to offer a significant improvement over the M-2 Bradley—given weapon systems technological advances by potential adversaries—operating alone without accompanying RCVs, the OMFV may offer little or marginal operational improvement over the M-2 Bradley. Recognizing the risks associated with a scenario where RCV fielding is significantly delayed or postponed due to technological challenges—along with a better understanding of the systematic and operational relationship between the OMFV and the RCV—could prove useful for policymakers. Another potential oversight question for Congress could be what is the role of Army Futures Command (AFC) in integrating requirements between OMFV and RCVs?

Section 804 Authority and the OMFV

Reportedly, on January 16, 2020, the Army canceled the current OMFV program, with the intent to restart the program following an analysis and revision of program requirements. According to Army officials, "a combination of requirements and schedule overwhelmed industry's ability to respond within the Army's timeline."55 Others suggest that after the Army released its final RFP, several companies raised concerns with the Army about the requirement for vendors to produce a nondevelopmental prototype within 15 months, as previously noted, as well as the requirement to fit two OMFVs inside a C-17 aircraft.56 At the time of the cancellation, Army officials reportedly would not commit to a timeline for a revised program or if it would affect the original fielding date of FY2026. Army officials characterized the program cancellation as positive, noting it would save $9 billion by cancelling the program early and that the decision to cancel demonstrated the value of AFC.57 Reportedly, on February 7, 2020, the Army reopened the OMFV competition by releasing a new market survey with a minimally prescriptive wish list and an acquisition strategy that shifted most of the initial cost burden to the Army, in what was described as "a bid to regain industry's trust after a faulty start."59 As part of the new acquisition strategy, the Army asked potential vendors to first submit a "rough digital prototype" and stated that the Army would not initially seek a target fielding date of FY2026. Also, the Army suggested the requirement to fit two OMFVs on a C-17 aircraft was not part of this new "wish list." Reportedly, it is hoped this new acquisition approach will bring companies who initially bowed out of the previous competition back into the new competition. The Army requested $327.732 million in Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) funding for the OMFV program in its FY2021 budget request. Funding is planned to be used for, among other things, funding up to five vendors so they can prepare for their digital design submissions. While there is not a great deal of public detail regarding the Army's new OMFV acquisition strategy, in an interview the ASA (ALT) Dr. Bruce Jette briefly outlined the Army's current plans as follows:61 While this tentative plan is useful, it can be argued that for a potentially $45 billion program,65 a more detailed plan, including estimated timelines, is necessary for oversight—particularly in light of this initial program misstep by the Army. In this regard, Congress might decide to require the Army to submit a more detailed plan.To some, the use of Section 804 authority offers great promise in developing and fielding qualifying weapon systems quickly and cost-effectively. Others note that rapid prototyping authorities under Section 804 will not eliminate the complexities of technology development and that operational requirements also drive the complexity and technical difficulty of a project. In acknowledging the potential benefits that Section 804 authority could bring to the Army's third attempt to replace the M-2 Bradley, as well as the risks associated with its use over a more traditional acquisition approach, policymakers might decide to examine the potential costs, benefits, and risks associated with using Section 804 authority for the OMFV programRecent Program Activities

Army Cancels OMFV Program54

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Ashley Tressel, "MPF, AMPV Now Part of NGCV Family of Vehicles," InsideDefense.com, October 12, 2018. |

||||||||

| 2. |

For additional information on the AMPV, see CRS Report R43240, The Army's Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV): Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert. |

||||||||

| 3. |

For additional information on MPF, see CRS Report R44968, Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT) Mobility, Reconnaissance, and Firepower Programs, by Andrew Feickert. |

||||||||

| 4. |

| ||||||||

| 5. |

|

||||||||

|

For additional information on autonomous systems, see CRS Report R45392, U.S. Ground Forces Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) and Artificial Intelligence (AI): Considerations for Congress, coordinated by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

Project Manager NGCV, NGCV OMFV Industry Day Briefing, August 6, 2018, and David Vergun, "Next Generation Combat Vehicle Must be Effective in Mega Cities, FORSCOM Commander Says," Army News, November 30, 2017. |

|||||||||

|

For additional information on Army artificial intelligence efforts, see CRS Report R45392, U.S. Ground Forces Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) and Artificial Intelligence (AI): Considerations for Congress, coordinated by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

For information on Army directed energy efforts, see CRS Report R45098, U.S. Army Weapons-Related Directed Energy (DE) Programs: Background and Potential Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

Sebastien Roblin, "The Army's Plan for a Super Bradley Fighting Vehicle are Dead," The National Interest, February 10, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), "Operation Desert Storm: Early Performance Assessment of Bradley and Abrams," GAO/NSIAD-92-94, January 1992. |

|||||||||

|

Reactive armor typically consists of a layer of high explosive between two metallic armor plates. When a penetrating weapon strikes the armor, the explosive detonates, thereby damaging the penetrator or disrupting the resulting plasma jet generated by the penetrator. |

|||||||||

|

Sebastien Roblin, "The Army's M-2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle is Old. What Replaces it Could be Revolutionary," The National Interest, October 27, 2018. |

|||||||||

|

Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., "Army Pushes Bradley Replacement; Cautious on Armed Robots," Breaking Defense, June 27, 2018. |

|||||||||

|

For additional information on active protection systems, see CRS Report R44598, Army and Marine Corps Active Protection System (APS) Efforts, by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

For additional historical information on the Future Combat System, see CRS Report RL32888, Army Future Combat System (FCS) "Spin-Outs" and Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV): Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert and Nathan J. Lucas. |

|||||||||

|

For additional historical information on the Ground Combat Vehicle, see CRS Report R41597, The Army's Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

Stephen Rodriguez, "Top Ten Failed Defense Programs of the RMA Era," War on the Rocks, December 2, 2014. |

|||||||||

|

United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), Army Modernization: Steps Needed to Ensure Army Futures Command Fully Applies Leading Practices, GAO-19-132, January 2019, p. 3. |

|||||||||

|

Stephen Rodriguez, "Top Ten Failed Defense Programs of the RMA Era," War on the Rocks, December 2, 2014. |

|||||||||

|

Information in this section is taken directly from CRS Report R41597, The Army's Ground Combat Vehicle (GCV) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

Remarks by then-Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel FY2015 Budget Preview, Pentagon Press Briefing Room, Monday, February 24, 2014. |

|||||||||

|

United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), Army Modernization: Steps Needed to Ensure Army Futures Command Fully Applies Leading Practices, GAO-19-132, January 2019, p. 3. |

|||||||||

|

Sebastian Sprenger, "Army Bides its Time in Next Steps Toward Infantry Fighting Vehicle," InsideDefense.com, June 10, 2015. |

|||||||||

|

Association of the U.S. Army, "Milley: Readiness, with Needed Modernization, is a Top Priority," March 1, 2016. |

|||||||||

|

U.S. Army Modernization Strategy, June 6, 2018, https://www.army.mil/standto/2018-06-06. |

|||||||||

|

Information in this section is taken directly from CRS Insight IN10889, Army Futures Command (AFC), by Andrew Feickert. |

|||||||||

|

The Army G-8 is the Army's lead for matching available resources to the defense strategy and the Army plan. They accomplish this through participation in Office of the Secretary of Defense–led defense reviews and assessments, the programming of resources, material integration, analytical and modeling capabilities, and the management of the Department of the Army studies and analysis. http://www.g8.army.mil/, accessed February 21, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

Sean Kimmons, "In First Year, Futures Command Grows from 12 to 24,000 Personnel," Army News Service, July 19, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), Army Modernization: Steps Needed to Ensure Army Futures Command Fully Applies Leading Practices, GAO-19-132, January 2019, p. 7. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid., p. 8. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

U.S. Army Stand-To, Army Futures Command, March 28, 2018. |

|||||||||

|

United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), Army Modernization: Steps Needed to Ensure Army Futures Command Fully Applies Leading Practices, GAO-19-132, January 2019, p. 14. |

|||||||||

|

For additional information on defense acquisition, see CRS Report R44010, Defense Acquisitions: How and Where DOD Spends Its Contracting Dollars, by Moshe Schwartz, John F. Sargent Jr., and Christopher T. Mann. |

|||||||||

|

Ashley Tressel, "How the Army Secretary Accelerated Service's New Combat Vehicle Program," InsideDefense.com, November 20, 2018. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

Project Manager NGCV, NGCV OMFV Industry Day Briefing, August 6, 2018, p. 9. |

|||||||||

|

Information in this section is taken from Devon L. Suits, "Army Looking for Optionally-Manned Fighting Vehicle," Army News Service, March 28, 2019; Connie Lee, "Breaking: Army to Release Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle RFP," National Defense, March 27, 2019; Jen Judson, "Army Drops Request for Proposals to Build Next-Gen Combat Vehicle Prototypes," Defense News.com, March 26, 2019: and Ashley Roque, "U.S. Army Releases OMFV RFP, Focusing on What is Deemed Realistically Obtainable," Janes, Defemse Weekly, April 10, 2019, p. 11. |

|||||||||

|

A Request for Proposal (RFP) is a solicitation used in negotiated acquisition to communicate government requirements to prospective contractor and to solicit proposals. At a minimum, solicitations shall describe the Government's requirement, anticipated terms and conditions that will apply to the contract, information required in the offeror's proposal, and (for competitive acquisitions) the criteria that will be used to evaluate the proposal and their relative importance. See DOD Acquisition Notes: http://acqnotes.com/acqnote/tasks/request-for-proposalproposal-development, accessed June 13, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

Jason Sherman, "Army Tweaking NGCV Requirements, Requests for Proposals Following Recent Industry Parlay," InsideDefense.com, October 5, 2018. |

|||||||||

|

Information in this section is taken from Ashley Tressel, "Contractors Debut Possible Bradley Replacement Vehicles," InsideDefense.com, October 19, 2018. |

|||||||||

|

Ashley Tressel, "BAE Ducks Out of OMFV Competition," InsideDefense.com, June 10, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

https://www.raytheon.com/capabilities/products/lynx-infantry-fighting-vehicle, accessed January 31, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

Information in this section is taken from Jen Judson, "Lynx 41 Disqualified from Bradley Replacement Competition," DefenseNews.com, October 4, 2019, and Sydney J. Freedberg, Jr., "Bradley Replacement: Army Risks Third Failure in a Row," Breaking Defense, October 7, 2019. |

|||||||||

|

Judson, "Lynx 41 Disqualified from Bradley Replacement Competition." |

|||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

|

Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., "Army Pushes Bradley Replacement; Cautious on Armed Robots," Breaking Defense, June 27, 2018. |

|||||||||

| 56. |

Ibid. |

||||||||

| 57. |

Ibid. |

||||||||

| 58. |

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

Ashley Roque and Robin Hughes, "No Contest: Briefing: The U.S. Army's OMFV Competition," Jane's Defence Weekly, November 13, 2019, p. 27. 57.

|

Ashley Tressel, "Army Scarps OMFV Program to Start Competition Over |

Ashley Tressel, "RCV Prototype Award Scheduled for November," InsideDefense.com, February 14, 2019. |

||||||

| 61. |

Ashley Tressel, "Army's Robotic Combat Vehicle to Have Three Variants," InsideDefense.com, November 29, 2018. |

||||||||

| 62. |

John Liang, "Army Calling for RCV-L White Papers," InsideDefense.com, June 4, 2019. |

||||||||

| 63. |

Except as required by law. |

||||||||

| 64. |

Tony Bertuca, "DOD Turns to Rapid Prototyping for Big Tech Gains, but Accepting New Risks," InsideDefense.com, August 30, 2018. |

||||||||

| 65. |

|

||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 67. | Information in this section, unless otherwise noted, is taken from Ashley Tressel, "Army | ||||||||

| 68. |

|

||||||||

|

Ibid. |

|||||||||

| 70. |

Ibid. |

||||||||

|

Information in this section is taken from Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Budget Estimates, Army, Justification Book of Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation, Army RDT&E – Volume |

|||||||||

|

|

Ashley Tressel, "Army Reopens Competition for Bradley Replacement," InsideDefense.com, February 7, 2020. 62.

|

|

Ibid. 63.

|

|

Ibid. 64.

|

|

Middle Tier Acquisition (MTA) is a rapid acquisition interim approach that focuses on delivering capability in a period of two to five years. The interim approach was granted by Congress in the FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) Section 804 and is not be subject to the Joint Capabilities Integration Development System (JCIDS) and DOD Directive 5000.01 "Defense Acquisition System." The approach consists of utilizing two acquisition pathways: (1) Rapid Prototyping and (2) Rapid Fielding. It does this by streamlining the testing and deployment of prototypes or upgrading existing systems with already proven technology. See AcqNotes, http://acqnotes.com/acqnote/acquisitions/middle-tier-acquisitions, accessed February 14, 2020. 65.

|

Jason Sherman, "Army Estimates $45 Billion Total Price Tag – or $11 Million per Vehicle – for OMFV," InsideDefense.com, October 11 |

H.Rept. 116-120, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Report of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives on H.R. 2500, June 19, 2019. |

| 73. |

Ibid., p. 453. |

||||||||

| 74. |

Ibid., p. 454. |

||||||||

| 75. |

Ibid., p. 8. |

||||||||

| 76. |

Ibid., pp. 37-38. |

||||||||

| 77. |

Ibid., p. 38. |

||||||||

| 78. |

Ibid., pp. 43-44. |

||||||||

| 79. |

Ibid., p. 92. |

||||||||

| 80. |

S. 1790 (Report No. 116-48) National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, June 11, 2019, p. 934. |

||||||||

| 81. |

Ibid., p. 41. |

||||||||

| 82. |

Ibid., pp. 68-69. |

||||||||

| 83. |

Ibid. p. 71. |

||||||||

| 84. |

Ibid. |

||||||||

| 85. |

Ibid., p. 74. |

||||||||

| 86. |

H.Rept. 116-84, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2020, May 23, 2019, p. 235 and p. 237. |

||||||||

| 87. |

S.Rept. 116-103, Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2020, September 12, 2019, pp. 172 and 173. |

||||||||

| 88. |

The Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) to the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) is administered by the Department of Defense (DOD). The DFARS implements and supplements the FAR. The DFARS contains requirements of law, DOD-wide policies, delegations of FAR authorities, deviations from FAR requirements, and policies/procedures that have a significant effect on the public. |

||||||||

| 89. |

Freedberg, "Bradley Replacement: Army Risks Third Failure in a Row." |

||||||||

| 90. |

Ibid. |

||||||||

| 91. |

Judson, "Lynx 41 Disqualified from Bradley Replacement Competition." |

||||||||

| 92. |

Project Manager NGCV, NGCV OMFV Industry Day Briefing, August 6, 2018. |

||||||||

| 93. |

For additional information on autonomous ground navigation and artificial intelligence, see CRS Report R45392, U.S. Ground Forces Robotics and Autonomous Systems (RAS) and Artificial Intelligence (AI): Considerations for Congress, coordinated by Andrew Feickert. |

||||||||

| 94. |

|