Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Changes from October 8, 2019 to November 18, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- The Budget and Homeland Security

- The U.S. Intelligence Community

- Homeland Security Research and Development

- National Strategy for Counterterrorism

- Energy Infrastructure Security

- U.S. Secret Service Protection of Persons and Facilities

- Protection of Executive Branch Officials

- Drug Trafficking at the Southwest Border

- Border Security Between Ports of Entry

- National Preparedness Policy

- Disaster Housing Assistance

- The Disaster Recovery Reform Act

- The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)

- National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Reauthorization and Reform

- Community Disaster Loans

- Firefighter Assistance Grants

- Emergency Communications

- U.S. National Health Security

- Cybersecurity

- Department of Homeland Security Human Resources Management

- DHS Unity of Effort

Summary

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th

Congress

Updated November 18, 2019

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

R45701

SUMMARY

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th

Congress

In 2001, in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, "“homeland security"” went from

being a concept discussed among a relatively small cadre of policymakers and strategic thinkers

to one broadly discussed among policymakers, including a broad swath of those in Congress.

Debates over how to implement coordinated homeland security policy led to the passage of the

Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296), the establishment of the Department of

Homeland Security (DHS), and extensive legislative activity in the ensuing years.

R45701

November 18, 2019

William L. Painter,

Coordinator

Specialist in Homeland

Security and

Appropriations

Initially, homeland security was largely seen as counterterrorism activities. Today, homeland

security is a broad and complex network of interrelated issues, in policymaking terms. For example, in its executive

summary, the Quadrennial Homeland Security Review issued in 2014 delineated the missions of the homeland security

enterprise as follows: prevent terrorism and enhance security; secure and manage the borders; enforce and administer

immigration laws; safeguard and secure cyberspace; and strengthen national preparedness and resilience.

This report compiles a series of Insights by CRS experts across an array of homeland security issues that may come before

the 116ththe 116th Congress. Several homeland security topics are also covered in CRS Report R45500, Transportation Security:

Issues for the 116th Congress.

.

The information contained in the Insights only scratches the surface of these selected issues. Congressional clients may

obtain more detailed information on these topic and others by contacting the relevant CRS expert listed in CRS Report

R45684, Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress: CRS Experts.

The Budget and Homeland Security

.

Congressional Research Service

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Contents

The Budget and Homeland Security................................................................................................ 1

The U.S. Intelligence Community ................................................................................................... 2

Homeland Security Research and Development ............................................................................. 4

National Strategy for Counterterrorism ........................................................................................... 6

Energy Infrastructure Security......................................................................................................... 8

U.S. Secret Service Protection of Persons and Facilities .............................................................. 10

Protection of Executive Branch Officials ....................................................................................... 11

Drug Trafficking at the Southwest Border .................................................................................... 13

Border Security Between Ports of Entry ....................................................................................... 14

National Preparedness Policy ........................................................................................................ 16

Disaster Housing Assistance.......................................................................................................... 17

The Disaster Recovery Reform Act ............................................................................................... 19

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) ............................................................................ 21

National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Reauthorization and Reform ..................................... 23

Community Disaster Loans ........................................................................................................... 25

Firefighter Assistance Grants ........................................................................................................ 27

Emergency Communications......................................................................................................... 28

U.S. National Health Security ....................................................................................................... 30

Cybersecurity................................................................................................................................. 32

Department of Homeland Security Human Resources Management ............................................ 34

DHS Unity of Effort ...................................................................................................................... 36

Figures

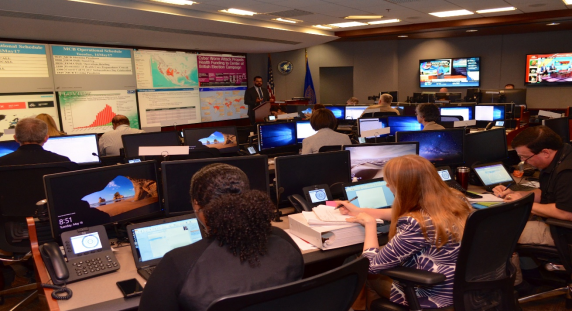

Figure 1. HHS Secretary’s Operations Center (SOC), Activated for the Wannacry

Ransomware Attack, May 2017 ................................................................................................. 31

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of Trump and Obama Counterterrorism Strategies ....................................... 7

Contacts

Author Information........................................................................................................................ 39

Congressional Research Service

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

The Budget and Homeland Security

(William L. Painter; February 28, 2019)

(William L. Painter; February 28, 2019)

Congress at times has sought to ascertain how much the government spends on securing the

homeland, either in current terms or historically. Several factors compromise the authoritativeness

of any answer to this question. One such complication is the lack of a consensus definition of

what constitutes homeland security, and another is that homeland security activities are carried

out across the federal government, in partnership with other public and private sector entities.

This insight examines those two complicating factors, and presents what information is available

on historical homeland security budget authority and current DHS appropriations.

Defining Homeland Security

No statutory definition of homeland security reflects the breadth of the current enterprise. The

Department of Homeland Security is not solely dedicated to homeland security missions, nor is it

the only part of the federal government with homeland security responsibilities.

The concept of homeland security in U.S. policy evolved over the last two decades. Homeland

security as a policy concept was discussed before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Entities like the Gilmore Commission and the Hart-Rudman Commission discussed the need to

evolve national security thinking in response to the increasing relative risks posed by nonstate

actors, including terrorist groups. After 9/11, policymakers concluded that a new approach was

needed to address these risks. A presidential council and department were established, and a series

of presidential directives were issued in the name of "“homeland security."” These efforts defined

homeland security as a response to terrorism. Later, multilevel government responses to disasters

such as Hurricane Katrina expanded the concept of homeland security to include disasters, public

health emergencies, and other events that threaten the United States, its economy, the rule of law,

and government operations. Some criminal justice elements could arguably be included in a broad

definition of homeland security. This evolution of the concept of homeland security made it

distinct from other federal government security operations such as homeland defense.

Homeland defense is primarily a Department of Defense (DOD) activity and is defined by DOD

as "“... the protection of U.S. sovereignty, territory, domestic population, and critical defense

infrastructure against external threats and aggression, or other threats as directed by the

President."” Homeland security, on the other hand, is a more broadly coordinated effort, involving

not only military activities, but the operations of civilian agencies at all levels of government.

The Federal Homeland Security Enterprise

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

The department was assembled from components pulled from 22 different government agencies

and began official operations on March 1, 2003. Since then, DHS has undergone a series of

restructurings and reorganizations to improve its effectiveness.

Although DHS does include many of the homeland security functions of the federal government,

several of these functions or parts of these functions remain at their original executive branch

agencies and departments, including the Departments of Justice, State, Defense, and

Transportation. Not all of the missions of DHS are officially "“homeland security"” missions. Some

DHS components have legacy missions that do not directly relate to conventional homeland

security definitions, such as the Coast Guard, and Congress has in the past debated whether

FEMA and its disaster relief and recovery missions belong in the department.

Congressional Research Service 1 Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress Analyzing Costs Across Government

Section 889 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 required the President'’s annual budget request

to include an analysis of homeland security funding across the federal government—not just

DHS. This requirement remained in effect through the FY2017 funding cycle. The resulting data

series, which included agency-reported data on spending in three categories—preventing and

disrupting terrorist attacks; protecting the American people, critical infrastructure, and key

resources; and responding to and recovering from incidents—provides a limited snapshot of the

scope of the federal government'’s investment in homeland security.

According to these data, from FY2003 through FY2017, the entire U.S. government directed

roughly $878 billion (in nominal dollars of budget authority) to those three mission sets. Annual

budget authority rose from roughly $41 billion in FY2003 to a peak in FY2009 of almost $74

billion. After that peak, reported annual homeland security budget authority hovered between $66

billion and $73 billion. Thirty different agencies reported having some amount of homeland

security budget authority.

One can compare this growth in homeland security budget authority to the budget authority

provided to DHS. The enacted budget for DHS rose from an Administration-projected $31.2

billion in FY2003, to almost $68.4 billion in FY2017.

FY2019 DHS Appropriations

For FY2019, the Trump Administration initially requested almost $75 billion in budget authority

for DHS, including over $47 billion in adjusted net discretionary budget authority through the

appropriations process. This included almost $7 billion to pay for the costs of major disasters

under the Stafford Act. The Administration requested additional Overseas Contingency

Operations (OCO) funding for the Coast Guard as a transfer from the U.S. Navy. Neither the

Senate nor the House bill reported out of their respective appropriations committees in response

to that request received floor consideration.

Continuing appropriations expired on December 21, 2018, leading to a 35-day partial shutdown

of federal government components without enacted annual appropriations—including DHS. This

was the longest such shutdown in the history of the U.S. government. On February 15, the

President signed into law P.L. 116-5, which included the FY2019 DHS annual appropriations act.

The act included almost $56 billion in adjusted net discretionary budget authority, including $12

billion for the costs of major disasters, and $165 million for Coast Guard OCO funding.

The current budget environment may present challenges to homeland security programs and DHS

going forward. The funding demands of ongoing capital investment efforts, such as the proposed

border wall and ongoing recapitalization efforts, and staffing needs for cybersecurity, border

security, and immigration enforcement, may compete with one another for limited funding across

the government and within DHS.

The U.S. Intelligence Community

(Michael E. DeVine; February 1, 2019)

Intelligence support of homeland security is a primary mission of the entire Intelligence

Community (IC). In fulfilling this mission, changes to IC organization and process, since 9/11,

have enabled more integrated and effective support than witnessed or envisioned since its

inception. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 revealed how barriers between intelligence and law

Congressional Research Service

2

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

enforcement, which originally had been created to protect civil liberties, had become too rigid,

thus preventing efficient, effective coordination against threats. In its final report, the

Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (the 9/11 Commission) identified how

these barriers contributed to degrading U.S. national security. The findings resulted in Congress

and the executive branch enacting legislation and providing policies and regulations designed to

enhance information sharing across the U.S. government.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296) gave the Department of Homeland Security

(DHS) responsibility for integrating law enforcement and intelligence information relating to

terrorist threats to the homeland. Provisions in the Intelligence Reform and Terrorist Prevention

Act (IRTPA) of 2004 (P.L. 108-458) established the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) as

the coordinator at the federal level for terrorism information and assessment and created the

position of Director of National Intelligence (DNI) to provide strategic management across the 17

organizational elements of the IC. New legal authorities accompanied these organizational

changes. At the federal, state, and local levels, initiatives to improve collaboration across the

federal government include the FBI-led Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs) and, more recently,

the DHS National Network of Fusion Centers (NNFC).

Within the IC, the FBI Intelligence Branch (FBI/IB), and DHS'’s Office of Intelligence and

Analysis (OIA), and the Coast Guard Intelligence (CG-2) enterprise, are most closely associated

with homeland security. OIA combines information collected by DHS components as part of their

operational activities (i.e., those conducted at airports, seaports, and the border) with foreign

intelligence from the IC; law enforcement information from federal, state, local, territorial and

tribal sources; and private sector data about critical infrastructure and strategic resources. OIA

analytical products focus on a wide range of threats to the homeland to include foreign and

domestic terrorism, border security, human trafficking, and public health. OIA'’s customers range

from the U.S. President to border patrol agents, Coast Guard personnel, airport screeners, and

local first responders. Much of the information sharing is done through the NNFC—with OIA

providing personnel, systems, and training.

The Coast Guard Intelligence (CG-2) enterprise is the intelligence component of the United

States Coast Guard (USCG). It serves as the primary USCG interface with the IC on intelligence

policy, planning, budgeting and oversight matters related to maritime security and border

protection. CG-2 has a component Counterintelligence Service, a Cryptologic Group, and an

Intelligence Coordination Center to provide analysis and supporting products on maritime border

security. CG-2 also receives support from field operational intelligence components including the

Atlantic and Pacific Area Intelligence Divisions, Maritime Intelligence Fusion Centers for the

Atlantic and Pacific, and intelligence staffs supporting Coast Guard districts and sectors.

FBI/IB includes four component organizations:

-

The Directorate of Intelligence has responsibility for all FBI intelligence

-

The Office of Partner Engagement develops and maintains intelligence sharing

-

The Office of Private Sector conducts outreach to businesses impacted by threats

-

Finally, the Bureau Intelligence Council provides internal to the FBI a forum for

Congressional Research Service

3

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

While the intelligence organizations of FBI and DHS are the only IC elements solely dedicated to

intelligence support of homeland security, all IC elements, to varying degrees, have some level of

responsibility for the overarching mission of homeland security. For example, in addition to

NCTC, the Office of the DNI (ODNI) includes the Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center

(CTIIC). It was established in 2015 and is responsible at the federal level for providing all-source analysisall-source

analysis of intelligence relating to cyber threats to the United States. Much like NCTC for

terrorism, CTIIC provides outreach to other intelligence organizations across the federal

government and at the state, and local levels to facilitate intelligence sharing and provide an

integrated effort for assessing and providing warning of cyber threats to the homeland.

IC organizational developments since 9/11 underscore the importance of adhering to privacy and

civil liberties protections that many feared might be compromised by the more integrated

approach to intelligence and law enforcement. This is particularly true considering the changing

nature of the threat: The focus of intelligence support of homeland security has evolved from

state-centric to increasingly focusing on nonstate actors, often individuals acting alone or as part

of a group not associated with any state. Collecting against these threats, therefore, requires strict

adherence to intelligence oversight rules and regulations, and annual training by the IC workforce

for the protection of privacy and civil liberties.

Homeland Security Research and Development

(Daniel Morgan; September 23November 18, 2019)

Overview

, 2019)

Overview

In the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Directorate of Science and Technology

(S&T) has primary responsibility for establishing, administering, and coordinating research and

development (R&D) activities. The Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office (CWMDO)

is responsible for R&D relating to detection of nuclear and radiological threats. Several other

DHS components, such as the Coast Guard, also fund R&D and R&D-related activities associated

with their missions. The Common Appropriations Structure that DHS introduced in its FY2017

budget includes an account titled Research and Development in seven different DHS components.

Issues for DHS R&D in the 116th Congress may include coordination, organization, and impact.

Coordination of R&D

The Under Secretary for S&T, who leads the S&T Directorate, has statutory responsibility for

coordinating homeland security R&D both within DHS and across the federal government (6

U.S.C. §182). The CWMDO also has an interagency coordination role with respect to nuclear

detection R&D (6 U.S.C. §592). Both internal and external coordination are long-standing

congressional interests.

Regarding internal coordination, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded in a

2012 report that because so many components of the department are involved, it is difficult for

DHS to oversee R&D department-wide. In January 2014, the joint explanatory statement for the

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 (P.L. 113-76) directed DHS to implement and report on

new policies for R&D prioritization. It also directed DHS to review and implement policies and

guidance for defining and overseeing R&D department-wide. In July 2014, GAO reported that

DHS had updated its guidance to include a definition of R&D and was conducting R&D portfolio

reviews across the department, but that it had not yet developed policy guidance for DHS-wide

R&D oversight, coordination, and tracking. In December 2015, the joint explanatory statement

Congressional Research Service

4

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

for the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) stated that DHS "“lacks a

mechanism for capturing and understanding research and development (R&D) activities

conducted across DHS, as well as coordinating R&D to reflect departmental priorities."” In March

2019, GAO reported that the S&T Directorate had "“strengthened its R&D coordination efforts

across DHS, but some challenges remain,"” including that not all DHS components participate

fully in the coordination mechanism that S&T has established. In September 2019, the DHS

Office of Inspector General found that the S&T Directorate was still not effectively coordinating

and integrating DHS-wide R&D.

, and the Senate Committee on Appropriations recommended that

“S&T should be the central component for departmental R&D, including R&D for other

components. Ensuring that S&T is the principal R&D component will contribute to the goal of

Departmental unity of effort.”

A challenge for external coordination is that the majority of homeland security-related R&D is

conducted by other agencies, most notably the Department of Defense and the Department of

Health and Human Services. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 directs the Under Secretary for

S&T, "“in consultation with other appropriate executive agencies,"” to develop a government-wide

national policy and strategic plan for homeland security R&D (6 U.S.C. §182), but no such plan

has ever been issued. Instead, the S&T Directorate has developed R&D plans with selected

individual agencies, and the National Science and Technology Council (a coordinating entity in

the Executive Office of the President) has issued government-wide R&D strategies in selected

topical areas, such as biosurveillance.

Organization for R&D

DHS has reorganized its R&D-related activities several times. It established CWMDO in

December 2017, consolidating the former Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO), most

functions of the former Office of Health Affairs (OHA), and some other elements. DNDO and

OHA were themselves both created, more than a decade ago, largely by reorganizing elements of

the S&T Directorate. The Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-387) )

expressly authorized the establishment and activities of CWMDO. The 116th Congress may

examine the implementation of that act.

The organization of DHS laboratory facilities may also be a focus of attention in the 116th

Congress. At its establishment, the S&T Directorate acquired laboratories from other

departments, including the Plum Island Animal Disease Center (from the Department of

Agriculture, USDA) and the National Urban Security Technology Laboratory, then known as the

Environmental Measurements Laboratory (from the Department of Energy). It subsequently

absorbed some laboratory facilities from other DHS components (such as the Transportation

Security Laboratory from the Transportation Security Administration), but other DHS

components retained their own laboratories (such as the U.S. Coast Guard Research and

Development Center). During the 115th Congress, the Federal Bureau of Investigation agreed to

assume some of the operational costs of the S&T Directorate'’s National Biodefense Analysis and

Countermeasures Center, and DHS proposed to transfer operational responsibility for the

National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF)—a biocontainment laboratory currently being

built by the S&T Directorate in Manhattan, Kansas—to USDA. In June 2019, DHS and USDA

signed a memorandum of agreement outlining their plans for the NBAF transfer, and USDA

released a strategic vision for the future of the facility.

Congressional Research Service

5

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Impact of R&D Results

Impact of R&D Results

In testimony at a Senate hearing in 2018, the Administration'’s nominee to be Under Secretary for

S&T described the S&T Directorate'’s mission as "“to deliver results"” and referred to "timely “timely

delivery and solid return on investment."” Members of Congress and other stakeholders have

sometimes questioned the impact of DHS R&D programs and whether enough of their results are

ultimately implemented in products actually used in the U.S. homeland security enterprise. Part of

the debate has been about finding the right balance between near-term and long-term goals. In

testimony at House hearing in 2017, a former Under Secretary for S&T stated that the directorate "

“has worked hard to focus on being highly relevant—shifting from the past focus on long-term

basic research to near-term operational impact."” Yet testimony from an industry witness at the

same House hearing stated that "“there is a perception among some in the industry that S&T

programs only infrequently significantly impact the operational or procurement activities of the

DHS components."” The 116th Congress may continue to examine the effectiveness and impact of

DHS R&D.

National Strategy for Counterterrorism

(John W. Rollins, January 29, 2019)

On October 4, 2018, President Trump released his Administration'’s first National Strategy for

Counterterrorism. The overarching goal of the strategy is to "“defeat the terrorists who threaten America'

America’s safety, prevent future attacks, and protect our national interests."” In describing the

need for this strategy, National Security Advisor John Bolton stated that the terrorist "“landscape is

more fluid and complex than ever"” and that the strategy will not "“focus on a single organization

but will counter all terrorists with the ability and intent to harm the United States, its citizens and

our interests."” The strategy states that a "“new approach"” will be implemented containing six

primary thematic areas of focus: (1) pursuing terrorists to their source; (2) isolating terrorists from

their sources of support; (3) modernizing and integrating the United States'’ counterterrorism

authorities and tools; (4) protecting American infrastructure and enhancing resilience; (5)

countering terrorist radicalization and recruitment; and (6) strengthening the counterterrorism

abilities of U.S. international partners. In announcing the strategy, President Trump stated, "When “When

it comes to terrorism, we will do whatever is necessary to protect our Nation."

”

In contrast, former President Obama'’s final National Strategy for Counterterrorism, published on

June 28, 2011, primarily focused on global terrorist threats emanating from Al Qaeda and

associated entities. The overarching goal of this strategy was to "“disrupt, dismantle, and

eventually defeat Al Qaeda and its affiliates and adherents to ensure the security of our citizens

and interests."” This strategy stated that the "“preeminent security threat to the United States

continues to be from Al Qaeda and its affiliates and adherents."” The strategy focused on the

threats posed by geographic dispersal of Al Qaeda, its affiliates, and adherents, and identified

principles that would guide United States counterterrorism efforts: Adhering to Core Values,

Building Security Partnerships, Applying Tools and Capabilities Appropriately, and Building a

Culture of Resilience. In announcing the release of this strategy, President Obama included a

quote from the speech he gave announcing the killing of Osama Bin Laden, "“As a country, we

will never tolerate our security being threatened, nor stand idly by when our people have been

killed. We will be relentless in defense of our citizens and our friends and allies. We will be true

to the values that make us who we are. And on nights like this one, we can say to those families

who have lost loved ones to Al Qaeda'’s terror: Justice has been done."

Since President Trump'”

Congressional Research Service

6

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Since President Trump’s Counterterrorism Strategy was published, many security observers have

pointed to the similarities and differences between the two Administration'’s approaches to

counterterrorism. Table 1, below, presents the language contained in each strategy identifying

major thematic aspects of the two counterterrorism strategies.

|

Focus Area |

Trump 2018 Strategy |

Obama 2011 Strategy |

|

Threat Actors |

Focus Area

Trump 2018 Strategy

Obama 2011 Strategy

Threat Actors

Numerous radical Islamists, |

Al Qaeda and its affiliates and |

|

Geographic Focus |

Global (including the United States) | Global (including the United States) |

Primary Entities Responsible for |

U.S. military, law enforcement, |

U.S. Intelligence Community, |

Core Principles Pursued to |

Pursue terrorists at their source; |

Adhering to U.S. values, building |

Balancing Terrorism-Related |

By sharing identity information and | By ensuring that counterterrorism |

|

Desired End State |

The terrorist threat to the United |

To defeat Al Qaeda, we must define |

Source: Comparison offered by CRS.

Congressional Research Service 7 Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress Energy Infrastructure Security

(Paul Parfomak; March 1, 2019)

Ongoing threats against the nation'’s natural gas, oil, and refined product pipelines have

heightened concerns about the security risks to these pipelines, their linkage to the electric power

sector, and federal programs to protect them. In a December 2018 study, the Government

Accountability Office (GAO) stated that, since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, "new “new

threats to the nation'’s pipeline systems have evolved to include sabotage by environmental

activists and cyber attack or intrusion by nations."” In a 2018 Federal Register notice, the

Transportation Security Administration stated that it expects pipeline companies will report

approximately 32 "“security incidents"” annually—both physical and cyber. The Pipeline and LNG

Facility Cybersecurity Preparedness Act (H.R. 370, , S. 300) would require the Secretary of Energy

to enhance coordination among government agencies and the energy sector in pipeline security;

coordinate incident response and recovery; support the development of pipeline cybersecurity

applications, technologies, demonstration projects, and training curricula; and provide technical

tools for pipeline security.

Pipeline Physical Security

Congress and federal agencies have raised concerns since at least 2010 about the physical security

of energy pipelines, especially cross-border oil pipelines. These security concerns were

heightened in 2016 after environmentalists in the United States disrupted five pipelines

transporting oil from Canada. In 2018, the Transportation Security Administration'’s Surface

Security Plan identified improvised explosive devices as key risks to energy pipelines, which "are “are

vulnerable to terrorist attacks largely due to their stationary nature, the volatility of transported

products, and [their] dispersed nature."” Among these risks, according to some analysts, are the

possibility of multiple, coordinated attacks with explosives on the natural gas pipeline system,

which potentially could "“create unprecedented challenges for restoring gas flows."

Pipeline Cybersecurity

”

Pipeline Cybersecurity

As with any internet-enabled technology, the computer systems used to operate much of the

pipeline system are vulnerable to outside manipulation. An attacker can exploit a pipeline control

system in a number of ways to disrupt or damage pipelines. Such cybersecurity risks came to the

fore in 2012 after reports of a series of cyber intrusions among U.S. natural gas pipeline

operators. In April 2018, new cyberattacks reportedly caused the shutdown of the customer

communications systems (separate from operation systems) at four of the nation'’s largest natural

gas pipeline companies. Most recently, in January 2019, congressional testimony by the Director

of National Intelligence singled out gas pipelines as critical infrastructure vulnerable to

cyberattacks which could cause disruption "“for days to weeks."

” Pipeline and Electric Power Interdependency

Pipeline cybersecurity concerns are exacerbated by growing interdependency between the

pipeline and electric power sectors. A 2017 Department of Energy (DOE) staff report highlighted

the electric power sector'’s growing reliance upon natural gas-fired generation and, as a result,

security vulnerabilities associated with pipeline gas supplies. These concerns were echoed in a

June 2018 op-ed by two commissioners on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

who wrote, "“as … natural gas has become a major part of the fuel mix, the cybersecurity threats

Congressional Research Service

8

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

to that supply have taken on new urgency."” A November 2018 report by the PJM regional

transmission organization concluded that "“while there is no imminent threat,"” the security of

generation fuel supplies, especially natural gas and fuel oil, "“has become an increasing area of

focus."” In a February 2019 congressional hearing on electric grid security, the head of the North

American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) testified that pipeline and electric grid

interdependency "“is fundamental"” to security.

The Federal Pipeline Security Program

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) within the Department of Homeland Security

(DHS) administers the federal program for pipeline security. The Aviation and Transportation

Security Act of 2001 (P.L. 107-71), which established TSA, authorized the agency "“to issue,

rescind, and revise such regulations as are necessary"” to carry out its functions (§101). The

Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-53) directs TSA

to promulgate pipeline security regulations and carry out necessary inspection and enforcement if

the agency determines that regulations are appropriate (§1557(d)). However, to date, TSA has not

issued such regulations, relying instead upon industry compliance with voluntary guidelines for

pipeline physical and cybersecurity. The pipeline industry maintains that regulations are

unnecessary because pipeline operators have voluntarily implemented effective physical and

cybersecurity programs. The 2018 GAO study identified a number of weaknesses in the TSA

program, including inadequate staffing, outdated risk assessments, and uncertainty about the

content and effectiveness of its security standards.

In fulfilling its responsibilities, TSA cooperates with the Department of Transportation'’s (DOT)

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA)—the federal regulator of

pipeline safety—under the terms of a 2004 memorandum of understanding (MOU) and a 2006

annex to facilitate transportation security collaboration. TSA also cooperates with DOE'’s recently

established Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER), whose

mission includes "“emergency preparedness and coordinated response to disruptions to the energy

sector, including physical and cyber-attacks."” TSA also collaborates with the Office of Energy

Infrastructure Security at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission—the agency which

regulates the reliability and security of the bulk power electric grid.

Issues for Congress

Over the last few years, most debate about the federal pipeline security program has revolved

around four principal issues. Some in Congress have suggested that TSA'’s current pipeline

security authority and voluntary standards approach may be appropriate, but that the agency may

require greater resources to more effectively carry out its mission. Others stakeholders have

debated whether security standards in the pipeline sector should be mandatory—as they are in the

electric power sector—especially given their growing interdependency. Still others have

questioned whether any of TSA'’s regulatory authority over pipeline security should move to

another agency, such as the DOE, DOT, or FERC, which they believe could be better positioned

to execute it. Concern about the quality, specificity, and sharing of information about pipeline

threats also has been an issue.

Congressional Research Service

9

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

U.S. Secret Service Protection of Persons and Facilities

Facilities (Shawn Reese; March 6, 2019)

Congress has historically legislated and conducted oversight on the U.S. Secret Service (USSS)

because of USSS'’ public mission of protecting individuals such as the President and his family,

and the USSS mission of investigating financial crimes. Most recently, the 115th115th Congress

conducted oversight on challenges facing the Service and held hearings on legislation that

addressed costs associated with USSS protective detail operations and special agents'’ pay. These

two issues remain pertinent in the 116th116th Congress due to recent, but failed, attacks on USSS

protectees, and the media'’s and public'’s attention on the cost the USSS incurs while protecting

President Donald Trump and his family.

USSS Protection Operations and Security Breaches

In October 2018, attempted bombings targeted former President Barack Obama, former Vice

President Joe Biden, and former First Lady Hillary Clinton. Prior to these attempted attacks, the

media reported other USSS security breaches, including two intruders (March and October 2017)

climbing the White House fence, and the USSS losing a government laptop that contained

blueprints and security plans for the Trump Tower in New York City. Various security breaches

during President Obama'’s Administration resulted in several congressional committee hearings.

Presidential safety is and has been a concern throughout the nation'’s history. For example, fears

of kidnapping and assassination threats to Abraham Lincoln began with his journey to

Washington, DC, for the inauguration in 1861. Ten Presidents have been victims of direct assaults

by assassins, with four resulting in death. Since the USSS started protecting Presidents in 1906,

seven assaults have occurred, with one resulting in death (President John F. Kennedy). 18 U.S.C.

Section 3056(a) explicitly identifies the following individuals authorized for USSS protection:

- President, Vice President, President- and Vice President-elect;

- immediate families of those listed above;

- former Presidents, their spouses, and their children under the age of 16;

- former Vice Presidents, their spouses, and their children under the age of 16;

- visiting heads of foreign states or governments;

-

distinguished foreign visitors and official U.S. representatives on special

-

major presidential and vice presidential candidates within 120 days of the general

USSS Protection Costs

Regardless of the location of protectees or costs associated with protective detail operations, the

USSS is statutorily required to provide full-time security. Congress has reinforced this

requirement in the past. In 1976, Congress required the USSS to not only secure the White

House, but also the personal residences of the President and Vice President. However, the costs

incurred by the USSS during the Trump Administration have generated interest and scrutiny. This

includes the USSS leasing property from President Trump, and the frequency with which

President Trump and his family have traveled.

Congressional Research Service

10

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Reportedly, the USSS leased property in Trump Tower in New York City. The USSS informed

CRS that leasing property from a protectee is not a new requirement with the Trump

Administration, but the USSS would neither confirm nor deny leasing Trump Tower property.

The USSS stated that it has leased a structure in the past at former Vice President Joe Biden's ’s

personal home in Delaware to conduct security operations. The USSS will not confirm if it is still

leasing this property.

Another protection cost issue other than leasing property from protectees is the overall cost of

protective detail operations. One aspect of protective detail operations that has garnered attention

from the media and the public is President Trump'’s and his family'’s travel. Some question

whether the President and his family have traveled more than other Presidents and their families

and what, if any, impact that has on security costs. The security cost of this travel is difficult to

assess, because the USSS is required to provide only annual budget justification information on "

“Protection of Persons and Facilities."” The USSS does not provide specific costs related to

individual presidential, or immediate family travel. The USSS states that it does not provide

specific costs associated with protectee protection due to the information being a security

concern.

Conclusion

concern.

Conclusion

USSS security operations and the costs associated with these operations represent consistent

issues of congressional concern. USSS protectees have been—and may continue to be—targeted

by assassins. Congress may wish to consider USSS protection issues within this broader context

as it conducts oversight and considers funding for the ever-evolving threats to USSS protectees

and the rapidly changing technology used in USSS security operations.

Protection of Executive Branch Officials

(Shawn Reese; February 19, 2019)

Due to the October 2018 attempted bombing attacks on current and former government officials

(and others), there may be congressional interest in policy issues surrounding protective details

for government officials. Attacks against political leaders and other public figures have been a

consistent security issue in the United States. According to a 1998 U.S. Marshals Service (USMS)

report, data on assassinations and assassination attempts against federal officials suggest that elected

elected officials are more likely to be targeted than those holding senior appointedappointed positions.

Congress also may be interested due to media reports of costs or budgetary requests associated

with funding security details for the heads of some departments and agencies, including the

Department of Education, the Department of Labor, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

In a 2000 report, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) stated that it was able to identify

only one instance when a Cabinet Secretary was physically harmed as a result of an assassination

attempt. This occurred when one of the Lincoln assassination conspirators attacked then-SecretarythenSecretary of State William Seward in his home in 1865. Even with few attempted attacks against

appointed officials, GAO reported that federal law enforcement entities have provided personal

protection details (PPDs) to selected executive branch officials since at least the late 1960s. In

total, GAO reported that from FY1997 through FY1999, 42 officials at 31 executive branch

agencies received security protection. Personnel from 27 different agencies protected the 42

officials: personnel from their own agencies or departments protected 36 officials, and personnel

from other agencies or departments, such as the U.S. Secret Service (USSS) and the USMS,

protected the remaining 6 officials. This Insight provides a summary of the statutory authority for

Congressional Research Service

11

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

executive branch official security, a Trump Administration proposal to consolidate this security

under the USMS, and issues for congressional consideration.

Statutory Authority for Protection

The USSS and the State Department are the only two agencies that have specific statutory

authority to protect executive branch officials. The USSS is authorized to protect specific

individuals under 18 U.S.C. §3056(a); the State Department'’s Diplomatic Security Service

special agents are authorized to protect specific individuals under 22 U.S.C. §2709(a)(3).

In 2000, GAO reported that other agencies providing protective security details to executive

branch officials cited various other legal authorities. These authorities included the Inspector

General Act of 1978 (5 U.S.C., App. 3), a specific delegation of authority set forth in 7 C.F.R.

§2.33(a)(2), and a 1970 memorandum from the White House Counsel to Cabinet departments.

Trump Administration Proposal

The Trump Administration proposed consolidating protective details at certain civilian executive

branch agencies under the USMS to more effectively and efficiently monitor and respond to

potential threats. This proposal was made in an attempt to standardize executive branch official

protection in agencies that currently have USMS security details or have their own employees

deputized by the USMS. This proposal would not affect any law enforcement or military agencies

with explicit statutory authority to protect executive branch officials, such as the USSS or the

Department of State'’s Diplomatic Security Service.

Threat assessments would be conducted with support from the USSS. Specifically, the Trump

Administration proposed that the USMS be given the authority to manage protective security

details of specified executive branch officials. These officials include the Secretaries of

Education, Labor, Energy, Commerce, Veterans Affairs, Agriculture, Transportation, Housing and

Urban Development, and the Interior; the Deputy Attorney General; and the Administrator of the

Environmental Protection Agency. The Trump Administration proposed that Deputy U.S.

Marshals would protect all of these Cabinet officials.

Currently, the USMS provides Deputy U.S. Marshals only for the Secretary of Education and the

Deputy Attorney General'’s protective details. These two departments, however, do not have

explicit statutory authority for protective details.

Potential Issues for Congress

The Administration'’s proposal appears to authorize the USMS to staff all protective details of

executive branch officials (excluding the USSS and the Departments of State and Defense)

deemed to need security, even protective security details that presently are staffed by agencies' ’

employees. Even though the USMS implements or oversees the protection of certain executive

branch officials, there appears to be no current study or research to assess the number of

additional U.S. Marshals that would be needed to expand protective details to identified executive

branch officials under this proposal. Additionally, the proposal does not address the funding that

may be needed for USMS protection of executive branch officials. The proposal, however, does

state that the Office of Management and Budget would coordinate with the Department of Justice

and affected agencies on the budgetary implications.

Congressional Research Service 12 Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress Drug Trafficking at the Southwest Border

(Kristin Finklea; January 31, 2019)

The United States sustains a multi-billion dollar illegal drug market. An estimated 28.6 million

Americans, or 10.6% of the population age 12 or older, had used illicit drugs at least once in the

past month in 2016. The 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment indicates that Mexican

transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) continue to dominate the U.S. drug market. They "

“remain the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other group is currently

positioned to challenge them."” The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) indicates that these

TCOs maintain and expand their influence by controlling lucrative smuggling corridors along the

Southwest border and by engaging in business alliances with other criminal networks,

transnational gangs, and U.S.-based gangs.

TCOs either transport or produce and transport illicit drugs north across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Traffickers move drugs through ports of entry, concealing them in passenger vehicles or

comingling them with licit goods on tractor trailers. Traffickers also rely on cross-border

subterranean tunnels and ultralight aircraft to smuggle drugs, as well as other transit methods

such as cargo trains, passenger busses, maritime vessels, or backpackers/"“mules."” While drugs

are the primary goods trafficked by TCOs, they also generate income from other illegal activities

such as the smuggling of humans and weapons, counterfeiting and piracy, kidnapping for ransom,

and extortion.

After being smuggled across the border, the drugs are distributed and sold within the United

States. The illicit proceeds may then be laundered or smuggled as bulk cash back across the

border. While the amount of bulk cash seized has declined over the past decade, it remains a

preferred method of moving illicit proceeds—along with money or value transfer systems and

trade-based money laundering. More recently, traffickers have relied on virtual currencies like

Bitcoin to move money more securely.

To facilitate the distribution and local sale of drugs in the United States, Mexican drug traffickers

have sometimes formed relationships with U.S. gangs. Trafficking and distribution of illicit drugs

is a primary source of revenue for these U.S.-based gangs and is among the most common of their

criminal activities. Gangs may work with a variety of drug trafficking organizations, and are often

involved in selling multiple types of drugs.

Current domestic drug threats, fueled in part by Mexican traffickers, include opioids such as

heroin, fentanyl, and diverted or counterfeit controlled prescription drugs; marijuana;

methamphetamine; cocaine; and synthetic psychoactive drugs. While marijuana remains the most

commonly used illicit drug, officials are increasingly concerned about the U.S. opioid epidemic.

As part of this, the most recent data show an elevated level of heroin use in the United States,

including elevated overdose deaths linked to heroin and other opioids, and there has been a

simultaneous increase in its availability, fueled by a number of factors including increased

production and trafficking of heroin by Mexican criminal networks. Increases in Mexican heroin

production and its availability in the United States have been coupled with increased heroin

seizures at the Southwest border. According to the DEA, the amount of heroin seized in the

United States, including at the Southwest border, has generally increased over the past decade;

nationwide heroin seizures reached 7,979 kg in 2017, with 3,090 kg (39%) seized at the

Southwest border, up from about 2,000 kg seized at the Southwest border a decade earlier.

In addition to heroin, officials have become increasingly concerned with the trafficking of

fentanyl, particularly nonpharmaceutical, illicit fentanyl. Fentanyl can be mixed with heroin

and/or other drugs, sometimes without the consumer'’s knowledge, and has been involved in an

Congressional Research Service

13

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

increasing number of opioid overdoses. Nonpharmaceutical fentanyl found in the United States is

manufactured in China and Mexico. It is trafficked into the United States across the Southwest

border or delivered through mail couriers directly from China, or from China through Canada.

Federal law enforcement has a number of enforcement initiatives aimed at countering drug

trafficking, both generally and at the Southwest border. For example, the Organized Crime Drug

Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF) program targets major drug trafficking and money

laundering organizations, with the intent to disrupt and dismantle them. The OCDETFs target

organizations that have been identified on the Consolidated Priority Organization Targets (CPOT)

List, the "“most wanted"” list of drug trafficking and money laundering organizations. In addition,

the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) program provides financial assistance to

federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies operating in regions of the United States

that have been deemed critical drug trafficking areas. There are 29 designated HIDTAs

throughout the United States and its territories, including a Southwest border HIDTA that is a

partnership of the New Mexico, West Texas, South Texas, Arizona, and San Diego-Imperial

HIDTAs.

Several existing strategies may also be leveraged to counter Southwest border drug trafficking.

For instance, the National Southwest Border Counternarcotics Strategy (NSBCS), first launched

in 2009, outlines domestic and transnational efforts to reduce the flow of illegal drugs, money,

and contraband across the Southwest border. In addition, the 2011 Strategy to Combat

Transnational Organized Crime provided the federal government'’s first broad conceptualization

of transnational organized crime, highlighting it as a national security concern and outlining

threats posed by TCOs—one being the expansion of drug trafficking.

The 116th

The 116th Congress may consider a number of options in attempting to reduce drug trafficking

from Mexico to the United States. For instance, Congress may question whether the Trump

Administration will continue or alter priorities set forth by existing strategies. Policymakers may

also be interested in examining various federal drug control agencies'’ roles in reducing Southwest

border trafficking. This could involve oversight of federal law enforcement and initiatives such as

the OCDETF program, as well as the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) and its

role in establishing a National Drug Control Strategy and Budget, among other efforts.

Border Security Between Ports of Entry

(Audrey Singer; February 11, 2019)

The United States'’ southern border with Mexico runs for approximately 2,000 miles over diverse

terrain, varied population densities, and discontinuous sections of public, private, and tribal land

ownership. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

is primarily responsible for border security, including the construction and maintenance of tactical

infrastructure, installation and monitoring of surveillance technology, and the deployment of

border patrol agents to prevent unlawful entries of people and contraband into the United States

(including unauthorized migrants, terrorists, firearms, narcotics, etc.). CBP'’s border management

and control responsibilities also include facilitating legitimate travel and commerce.

Existing statute pertaining to border security confers broad authority to DHS to construct barriers

along the U.S. border to deter unlawful crossings, and more specifically directs DHS to deploy

fencing along "“at least 700 miles"” of the southern border with Mexico. The primary statute is the

Illegal Immigration and Immigrant Responsibility ACT (IIRIRA) as amended by the REAL ID

Act of 2005, the Secure Fence Act of 2006, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008.

.

Congressional Research Service

14

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

On January 25, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13767 " “Border Security and

Immigration Enforcement Improvements,"” which addresses, in part, the physical security of the

southern border and instructed the DHS Secretary to "“take all appropriate steps to immediately

plan, design, and construct a physical wall along the southern border, using appropriate materials

and technology to most effectively achieve complete operational control."” The order did not

identify the expected mileage of barriers to be constructed.

The three main dimensions of border security are tactical infrastructure, surveillance technology,

and personnel.

Tactical Infrastructure. Physical barriers between ports of entry (POE) on the southern border

vary in age, purpose, form, and location. GAO reports that at the end of FY2015, about one-third

of the southern border, or 654 miles, had a primary layer of fencing: approximately 350 miles

designed to keep out pedestrians, and 300 miles to prevent vehicles from entering. Approximately

90% of the 654 miles of primary fencing is located in the five contiguous Border Patrol sectors

located in California, Arizona, and New Mexico, while the remaining 10% is in the four eastern

sectors (largely in Texas) where the Rio Grande River delineates most of the border. About 82%

of primary pedestrian fencing and 75% of primary vehicle fencing are considered "modern" and “modern” and

were constructed between 2006 and 2011. Across 37 discontinuous miles, the primary layer is

backed by a secondary layer (pedestrian) as well as an additional 14 miles of tertiary fencing

(typically to delineate property lines). No new miles of primary fencing have been constructed

since the 654 miles were completed in 2015, but sections of legacy fencing and breached areas

have been replaced. Additional tactical infrastructure includes roads, gates, bridges, and lighting

designed to support border enforcement, and to disrupt and impede illicit activity.

Surveillance Technology. To assist in the detection, identification, and apprehension of

individuals illegally entering the United States between POEs, CBP also maintains border

surveillance technology. Ground technology includes sensors, cameras, and radar tailored to fit

specific terrain and population densities. Aerial and marine surveillance vessels, manned and

unmanned, patrol inaccessible regions.

Personnel. Approximately 19,500 Border Patrol agents were stationed nationwide, with most

(16,600) at the southern border in FY2017. Subject to available appropriations, Executive Order

13767 calls on CBP to take appropriate action to hire an additional 5,000 Border Patrol agents.

However, CBP continues to face challenges attaining statutorily established minimum staffing

levels for its Border Patrol positions despite increased recruitment and retention efforts.

Southern border security may be improved by changes to tactical infrastructure, surveillance

technology, and personnel. A challenge facing policymakers is in determining the optimal mix of

border security strategies given the difficulty of measuring the effectiveness of current efforts.

While the number of apprehensions of illegal entrants has long been used to measure U.S. Border

Patrol performance, it does not measure illegal border crossers who evade detection by the Border

Patrol. When apprehensions decline, whether it is due to fewer illegal entrants getting caught or

fewer attempting to enter illegally is not known. Other difficulties include measuring the

contribution of any single border security component in isolation from the others, assessing the

extent to which enforcement actions deter illegal crossing attempts, and evaluating ongoing

enforcement efforts outside of border-specific actions and their impact on border security.

Section 1092 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) directs the Secretary of

Homeland Security to provide annual metrics on border security that are intended to help address

some of the challenges of measuring the impact of border security efforts. DHS has produced

baseline estimates that go beyond apprehensions statistics to measure progress towards meeting

the goals contained in Executive Order 13767.

Congressional Research Service

15

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Congress, through CBP appropriations—and appropriations to its predecessor agency, the

Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)—has invested in tactical infrastructure,

surveillance technology, and personnel since the 1980s. Given the changing level of detail and

structure of appropriations for border infrastructure over time, it is not possible to develop a

consistent history of congressional appropriations specifically for border infrastructure. However,

CBP has provided the Congressional Research Service (CRS) with some historical information on

how it has allocated funding for border barrier planning, construction, and operations and support.

Between FY2007 and FY2018, CBP allocated just over $5.0 billion to these activities, including

almost $1.4 billion specifically for border barrier construction and improvement through a new "

“Wall Program"” activity in its FY2018 budget.

The 116th

The 116th Congress is considering a mix of tactical infrastructure, including fencing, surveillance

technologies, and personnel to enhance border security between U.S. POEs. Some experts have

warned that the northern border may need more resources and oversight than it is currently

receiving in light of potential national security risks. Other border security priorities that may be

considered during the 116th116th Congress include improvements to existing facilities and screening

and detection capacity at U.S. POEs.

National Preparedness Policy

(Shawn Reese; February 19, 2019)

The United States is threatened by a wide array of hazards, including natural disasters, acts of

terrorism, viral pandemics, and man-made disasters, such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The

way the nation strategically prioritizes and allocates resources to prepare for all hazards can

significantly influence the ultimate cost to society, both in the number of human casualties and

the scope and magnitude of economic damage. As authorized in part by the Post-Katrina

Emergency Reform Act of 2006 (PKEMRA; P.L. 109-295), the President, acting through the

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Administrator, is directed to create a "national “national

preparedness goal"” (NPG) and develop a "“national preparedness system"” (NPS) that will help "

“ensure the Nation'’s ability to prevent, respond to, recover from, and mitigate against natural

disasters, acts of terrorism, and other man-made disasters"” (6 U.S.C. §§743-744).

Currently, NPG and NPS implementation is guided by Presidential Policy Directive 8: National

Preparedness (PPD-8), issued by then-President Barack Obama on March 30, 2011. PPD-8

rescinded the existing Homeland Security Presidential Directive 8: National Preparedness

(HSPD-8), which was released and signed by then-President George W. Bush on December 17,

2003.

As directed by PPD-8, the NPS is supported by numerous strategic component policies, national

planning frameworks (e.g., the National Response Framework), and federal interagency

operational plans (e.g., the Protection Federal Interagency Operational Plan). In brief, the NPS

and its many component policies represent the federal government'’s strategic vision and

planning, with input from the whole community, as it relates to preparing the nation for all

hazards. The NPS also establishes methods for achieving the nation'’s desired level of

preparedness for both federal and nonfederal partners by identifying the core capabilities

necessary to achieve the NPG. A capability capability is defined in law as "“the ability to provide the means

to accomplish one or more tasks under specific conditions and to specific performance standards.

A capability may be achieved with any combination of properly planned, organized, equipped,

trained, and exercised personnel that achieves the intended outcome."” A core capability A core capability is defined

in PPD-8 as a capability that is "“necessary to prepare for the specific types of incidents that pose

the greatest risk to the security of the Nation."

”

Congressional Research Service

16

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

Furthermore, the NPS includes annual National Preparedness Reports that document progress

made toward achieving national preparedness objectives. The reports rely heavily on self-assessmentselfassessment processes, called the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA)

and Stakeholder Preparedness Review (SPR), to incorporate the perceived risks and capabilities

of the whole community into the NPS. In this respect, the NPS'’s influence may extend to federal,

state, and local budgetary decisions, the assignment of duties and responsibilities across the

nation, and the creation of long-term policy objectives for disaster preparedness.

It is within the Administration'’s discretion to retain, revise, or replace the overarching guidance

of PPD-8, and the 116th116th Congress may provide oversight of the NPS. Congress may have interest

in overseeing a variety of factors related to the NPS, such as whether

-

the NPS conforms to the objectives of Congress, as outlined in the PKEMRA

-

the NPS is properly informed by quantitative and qualitative data and outcome

-

federal roles and responsibilities have, in Congress

'’s opinion, been properly -

nonfederal resources and stakeholders are efficiently incorporated into NPS

-

federal, state, and local government officials are allocating the appropriate

Ultimately, if the NPS is determined not to fulfill the objectives of the 116th116th Congress, Congress

could consider amending the PKEMRA statute to create new requirements, or revise existing

provisions, to manage the amount of discretion afforded to the President in NPS implementation.

This could mean, for example, the 116th116th Congress directly assigning certain preparedness

responsibilities to federal agencies through authorizing legislation different than those indicated

by national preparedness frameworks. As a hypothetical example, Congress could decide that

certain federal agencies, such as the Department of Commerce or Housing and Urban

Development, should take more or less of a role in the leadership of disaster recovery efforts

following major incidents than is prescribed by the National Disaster Recovery Framework.

Congress also may consider prioritizing the amount of budget authority provided to some core

capabilities relative to others. As a hypothetical example, Congress may prioritize resourcing

those federal programs needed to support the nation'’s core capability of "“Screening, Search, and Detection"

Detection” versus resourcing those federal programs needed to support "“Fatality Management

Services."

” Disaster Housing Assistance

(Elizabeth M. Webster; February 26, 2019)

After the President issues an emergency or major disaster declaration under the Robert T. Stafford

Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act, 42 U.S.C. §§5121 et seq.), the

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may provide various temporary housing

assistance programs to meet disaster survivors'’ needs. However, limitations on these programs

may make it difficult to transition disaster survivors into permanent housing. This Insight

Congressional Research Service

17

Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress

provides an overview of the primary housing assistance programs available under the Stafford

Act, and potential considerations for Congress.

Transitional Sheltering Assistance

FEMA-provided housing assistance may include short-term, emergency sheltering

accommodations under Section 403 of the Stafford Act (42 U.S.C. §5170b), including the

Transitional Sheltering Assistance (TSA) program, which received significant attention as it was

coming to an end for disaster survivors of Hurricane Maria from Puerto Rico. This transition

process highlighted challenges to helping individuals and families obtain interim and permanent

housing following a disaster.

TSA is intended to provide short-term hotel/motel accommodations to individuals and families

who are unable to return to their pre-disaster primary residence because a declared disaster

rendered it uninhabitable or inaccessible. The initial period of TSA assistance is 5-14 days, and it

can be extended in 14-day intervals for up to 6 months from the date of the disaster declaration.

However, some Hurricane Maria disaster survivors from Puerto Rico remained in the TSA

program for nearly one year due to extensions of the program (including by court order).

Hurricane Maria is not the only incident that has received multiple TSA program extensions;

disaster survivors of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Sandy also received extensions for nearly a

year. Research suggests that housing-instable individuals and families may have an "increased “increased

risk of adverse mental health outcomes,"” which may reveal a drawback to using an emergency

sheltering solution, such as TSA, to house individuals and families in hotels/motels for extended

periods of time.

Individuals and Households Program

Interim housing needs may be better met through FEMA'’s Individuals and Households Program

(IHP) under Section 408 of the Stafford Act (42 U.S.C. §5174). Financial (e.g., assistance to

reimburse temporary lodging expenses and rent alternate housing accommodations) and/or direct

(e.g., multi-family lease and repair and manufactured housing units (MHUs)) assistance may be

available to eligible individuals and households who, as a result of a disaster, have uninsured or

under-insured necessary expenses and serious needs that cannot be met through other means or

forms of assistance. IHP assistance is intended to be temporary, and is generally limited to a

period of 18 months from the date of the declaration, but may be extended by FEMA.

Although IHP provides various assistance options, eligibility and programmatic limitations exist

on their receipt and use. For example, disaster survivors whose primary residence is determined

to be habitable or who have access to adequate rent-free housing may be ineligible to receive

assistance, even if they are unable to return for other reasons (e.g., lack of employment).

Challenges to providing financial assistance, such as rental assistance, may include lack of

available, affordable housing stock. Additionally, regulations and policies may not permit FEMA

to immediately adjust rental payment rates to reflect the location where a disaster survivor has relocated.

relocated. So even if housing stock is available, the difference in cost may result in the inability

of some eligible applicants to secure a housing unit. Challenges to providing direct assistance,

such as MHUs, may include restrictions on the placement of MHUs. Additionally, FEMA'’s direct

lease assistance program is usually only offered if rental resources are scarce, and the area where

direct lease assistance is available may be limited. Further, following a catastrophic incident

additional challenges include the need to restore infrastructure, community services, and

employment opportunities, which may impact where disaster survivors decide to locate following

a disaster. This decision may impact the benefits for which they may be eligible.

Congressional Research Service 18 Selected Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress Disaster Housing Assistance Program

Following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Ike and Gustav, and Sandy, FEMA executed Interagency

Agreements with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to administer

the Disaster Housing Assistance Program (DHAP) in order to provide rental assistance and case

management services. Although DHAP fell under Section 408 of the Stafford Act and was funded

through the Disaster Relief Fund, it was not subject to some of the limitations of the IHP, and it

may have allowed families to receive more assistance for longer periods of time than they may

have received under IHP. Despite being identified as a promising interim housing strategy and

potential solution to the challenge of meeting long-term housing needs in the National Disaster

Housing Strategy, FEMA has not implemented DHAP following more recent disasters. Most

recently, in response to the Governor of Puerto Rico'’s request to authorize DHAP, FEMA stated

DHAP would not be implemented, because FEMA and HUD "“offered multiple housing solutions

that are better able to meet the current housing needs of impacted survivors."” FEMA also noted

that the Office of Inspector General (OIG) had raised concerns about DHAP'’s cost effectiveness;

the OIG recommended that, before FEMA activates DHAP again, it "“[c]onduct a cost-benefit

analysis.... "

” Potential Considerations for Congress

FEMA provides temporary housing assistance to meet short-term and interim disaster housing

needs; however, clearly defining the use of these programs and identifying a process to assist

some disaster survivors with attaining permanent housing may be needed to comprehensively

address disaster housing needs throughout all phases of recovery. Congress may request an

evaluation of FEMA'’s capacity to adequately and cost-effectively meet the needs of disaster

survivors. Congress may also evaluate the roles of government and private/nonprofit entities in

providing disaster housing assistance; require FEMA to collaborate with disaster housing partners

to identify and outline short, interim, and long-term disaster housing solutions; and require an

update to the National Disaster Housing Strategy to reflect the roles and responsibilities of

housing partners, current practices and solutions, and the findings of any such evaluations.

Congress may also pursue legislative solutions, including by consolidating, eliminating, or

revising existing authorities and programs, or creating new programs that address unmet needs.

The Disaster Recovery Reform Act

(Elizabeth M. Webster; February 26, 2019)