DHS Border Barrier Funding Through FY2021

Changes from August 27, 2019 to September 6, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Historical Context

- Establishment and Policing of the U.S.-Mexico Border

- Emergence of Barriers as Deterrence

- From INS (in Department of Justice) to CBP (in Homeland Security)

- DHS Border Barriers: Legislative Era (2005-2016)

- Enacted Authorizations and Appropriations

- Identifying Border Barrier Funding

- DHS Border Barriers: Executive Era (2017-Present)

- Enacted Appropriations

- Comparing DHS Border Barrier Funding Across Eras

- Questions Relevant to Future DHS Border Barrier Funding

Figures

- Figure 1. BSFIT Appropriations Request and Enacted Level, FY2008-FY2016

- Figure 2. CBP-Reported Data on Border Barrier Funding, FY2007-FY2016

- Figure 3. DHS Funding Available for Border Barrier Construction, FY2007-FY2019

- Figure A-1. Annual and Cumulative Miles of Primary Barriers and Year Constructed, Southwest Border, 1990-2018

Tables

Summary

Congress and the Administration are debating enhancing and expanding border barriers on the southwest border in the context of border security.

The purpose of barriers on the U.S.-Mexico border has evolved over time. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, fencing at the border was more for demarcation, or discouraging livestock from wandering over the border, rather than deterring smugglers or illegal migration.

Physical barriers to deter migrants are a relatively new part of the border landscape, first being built in the 1990s in conjunction with counterdrug efforts. This phase of construction, extending into the 2000s, was largely driven by legislative initiatives. Specific authorization for border barriers was provided in 1996 in the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), and again in 2006 in the Secure Fence Act. These authorities were superseded by legislation included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which rewrote key provisions of IIRIRA and replaced most of the Secure Fence Act. The result of these initiatives was construction of more than 650 miles of barriers along the nearly 2,000-mile border.

A second phase of construction is marked by barrier construction being an explicit part of the White House agenda. On January 25, 2017, the Trump Administration issued Executive Order 13767, "Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements." Section 2(a) of the E.O. indicates that it is the policy of the executive branch to "secure the southern border of the United States through the immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border, monitored and supported by adequate personnel so as to prevent illegal immigration, drug and human trafficking, and acts of terrorism."

As debate over funding for, and construction of, a "border wall system" in this phase continues, putting border barrier funding in its historical context has been of interest to some in Congress.

There has not been an authoritative compilation of data over time on the level of federal investment in border barriers. This is in part due to the evolving structure of the appropriations for agencies charged with protecting the border—account structures have shifted, initiatives have come and gone, and appropriations typically have not specified a precise level of funding for barriers as opposed to other technologies that secure the border. Funding was not specifically designated for border barrier construction until FY2006.

The more than $3 billion in appropriations provided by Congress for border barrier planning and construction since the signing of the EO exceeds the amount provided for those purposes from FY2007-FY2016 by more than $618 million. Almost all of this funding has been provided for improvements to the existing barriers at the border; a portion of the funds are available for new construction. CBP announced on August 8, 2019, a contract award for building 11 miles of levee wall system (steel bollard on top of a concrete wall) in areas where no barriers currently exist in the Rio Grande Valley Sector.

The Administration has taken steps to secure funding beyond the levels approved by Congress for border barriers, including transferring roughly $601 million from the Treasury Forfeiture Fund to CBP; using $2.5 billion in Department of Defense funds transferred to the Department's counterdrug programs to construct border barriers; and potentially reallocating up to $3.6 billion from other military construction projects using authorities under the declaration of a national emergency.

This report provides an overview of the funding appropriated for border barriers, based on data from CBP and congressional documents, and a primer on the Trump Administration's efforts to enhance the funding for border barriers, with a brief discussion of the legislative and historical context of construction of barriers at the U.S-Mexico border. It concludes with a number of unanswered questions Congress may wish to explore as this debate continues. An appendix tracks barrier construction mileage on the U.S.-Mexico border by year.

Introduction

Congress and the Donald J. Trump Administration are debating enhancing and expanding barriers on the southwest border. The extent of these barriers, and how construction of these barriers will be funded has become a central part of the interactions between Congress and the Trump Administration on border security and funding legislation for the broader federal government.

An authoritative compilation of data on the details of federal investment in border barriers is missing from the debate. This is in part due to the evolving structure of the appropriations for agencies charged with protecting the border—account structures have shifted, initiatives have come and gone, and appropriations prior to FY2017 typically did not specify a precise level of funding for barriers as opposed to other technologies that secure the border. As the Trump Administration has continued to advocate for funding for a "border wall system," putting border barrier funding in its historical context has been of interest to some in Congress. This report briefly contextualizes the history of U.S. enforcement of the U.S.-Mexico border, before turning to funding for border barriers within the contemporary period, accounting for changing appropriations structures.

Historical Context

Establishment and Policing of the U.S.-Mexico Border

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, with the cession of land to the United States, ended the Mexican-American War and set forth an agreed-upon boundary line between the United States and Mexico. The physical demarcation of the boundary was essentially set by the Gadsden Purchase, finalized in 1854, with some minor adjustments since then.1

Securing U.S. borders has primarily been the mission of the U.S. Border Patrol, which was established by Congress by an appropriations act in 1924.2 Initially a relatively small force of 450 officers patrolled both the northern and southern borders between inspection stations, guarding against the smuggling of contraband and unauthorized migrants.3

The Immigration Act of 19244 established immigration quotas for most countries, with the exception of those in the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico. (While some specific limitations existed, per-country quotas for Western Hemisphere countries did not exist until 1976.)5) Earlier policies had set categorical exclusions to entry (e.g., for Chinese and other Asian immigrants) that were exceptions to an otherwise open immigration policy. Between 1942 and 1964, the Bracero Program brought in nearly five5 million Mexican agricultural workers to fill the labor gap caused by World War II. Both employers and employees became used to the seasonal work, and when the program ended, many continued this employment arrangement without legal authorization.6 Debates about enhancing enforcement of immigration laws ensued in the late 1970s and 1980s, largely in concert with counter-drug smuggling efforts7 and interest in curbing the post-Bracero rise in unauthorized flows of migrant workers.

Emergence of Barriers as Deterrence

A significant effort to construct barriers on the southern border to explicitly serve as a deterrent to illegal entry by migrants or smugglers into the United States began in the early 1990s. In 1991, U.S. Navy engineers built a ten-foot-high corrugated steel barrier between San Diego and Tijuana made of surplus aircraft landing mats, an upgrade to the previous chain-link fencing.8

In 1994, the Border Patrol (then part of the Department of Justice under the Immigration and Naturalization Service, INS) released a strategic plan for enforcing immigration laws along the U.S. border, as a part of a series of immigration reform initiatives.9 The plan, developed by Chief Patrol Agents, Border Patrol headquarters staff, and planning experts from the Department of Defense Center for Low Intensity Conflict, described their approach to improving control of the border through a strategy of "prevention through deterrence," under which resources were concentrated in major entry corridors to establish control of those areas and force traffic to more difficult crossing areas.

The Border Patrol will increase the number of agents on the line and make effective use of technology, raising the risk of apprehension high enough to be an effective deterrent. Because the deterrent effect of apprehensions does not become effective in stopping the flow until apprehensions approach 100 percent of those attempting entry, the strategic objective is to maximize the apprehension rate. Although a 100 percent apprehension rate is an unrealistic goal, we believe we can achieve a rate of apprehensions sufficiently high to raise the risk of apprehension to the point that many will consider it futile to continue to attempt illegal entry.10

Prior to 1996, federal statute neither explicitly authorized nor required barrier construction along international borders.11 In 1996, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) was enacted, and Section 102(a) specifically directing the Attorney General12 to "install additional physical barriers and roads ... in the vicinity of the United States border to deter illegal crossings in areas of high illegal entry into the United States."13

From INS (in Department of Justice) to CBP (in Homeland Security)

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. government changed its approach to homeland security issues, including control of the border. As a part of the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003, INS was dismantled, and the Border Patrol and its responsibility for border security were moved from the Department of Justice to DHS as a part of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).14 DHS and CBP stood up in 2003, and received their first annual appropriations in FY2004.

DHS Border Barriers: Legislative Era (2005-2016)

During the 109th and the first session of the 110th Congresses (2005-2007), comprehensive immigration reform legislation and narrower border security measures were debated. One result was that Congress explicitly authorized and funded new construction of border barriers, significantly increasing their presence.

Enacted Authorizations and Appropriations

In the 109th Congress, two bills were enacted that amended Section 102 of IIRIRA, easing the construction of additional border barriers. Section 102 of the REAL ID Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-13, Div. B) included broad waiver authority that allowed for expedited construction of border barriers.15 The Secure Fence Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-367) directed the Secretary of Homeland Security to "achieve and maintain operational control over the entire international land and maritime borders of the United States," mandated the construction of certain border barriers and technology on the border with Mexico by the end of 2008, and required annual reports on progress on border control. Unlike the initial legislative packages that included border barriers as a part of a suite of remedies across government to the border security problem in the context of immigration policy, the act provided authorization for DHS alone to achieve "operational control" of the border through barriers, tactical infrastructure, and surveillance while largely not addressing the broader set of immigration policies that could contribute to improved border security.16 The Secure Fence Act substantially revised IIRIRA Section 102(b) to include five specific border areas to be covered by the installation of fencing, additional barriers, and technology.

The FY2006 DHS Appropriations Act (P.L. 109-90) provided the first appropriations specifically designated for the Border Patrol, after being reorganized as a part of CBP under DHS, to construct border barriers.17 The act specified $35 million for CBP's San Diego sector fencing.18 This funding was part of a surge in CBP construction spending from $91.7 million in FY2005—and $93.4 million in the FY2006 request—to $270.0 million for FY2006 enacted appropriations. This direction also represented the first specific statutory direction provided to CBP on the use of its construction funds.

Toward the end of 2007, in the first session of the 110th Congress, Section 564 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008 amended Section 102 of IIRIRA again, requiring the construction of reinforced fencing along at least 700 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border, where it would be "most practical and effective."19 It also included flexibility in implementing this requirement, stating that:

nothing in this paragraph shall require the Secretary of Homeland Security to install fencing, physical barriers, roads, lighting, cameras, and sensors in a particular location along an international border of the United States, if the Secretary determines that the use or placement of such resources is not the most appropriate means to achieve and maintain operational control over the international border at such location.20

The "BSFIT" Appropriation

Starting in FY2007 and continuing through FY2016, border barrier funding in CBP's budget was included in the "Border Security Fencing, Infrastructure, and Technology" (BSFIT) appropriation. When BSFIT was established in the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2007 (P.L. 109-295), it consolidated border technology and tactical infrastructure funding from other accounts, including CBP's Construction appropriation and Salaries and Expenses appropriation.21

According to the FY2007 DHS appropriations conference report, Congress provided a total of $1,512,565,000 for BSFIT activities for FY2007: $1,187,565,000 from annual appropriations in P.L. 109-295, and $325,000,000 in prior enacted supplemental appropriations from P.L. 109-234 and other legislation. Congress directed portions of that initial appropriation to two specific border security projects, and withheld $950 million until a spending plan for a border barrier was provided. Starting in FY2008, a PPA22 for "Development and Deployment" of technology and tactical infrastructure was included at congressional direction.23

The BSFIT Development and Deployment PPA is, over the tenure of CBP, the most consistently structured year-to-year direction from Congress to CBP regarding putting border security technology and infrastructure in the field, covering FY2008-FY2016.

The BSFIT Development and Deployment structure remained unchanged until the implementation of the Common Appropriations Structure (CAS) for DHS in the FY2017 appropriations cycle, which redistributed BSFIT funding to the Operations and Support (OS) appropriation and the Procurement, Construction, and Improvements (PC&I) appropriation.24 Border barrier design and construction funding, other than ports of entry, is now included in the Border Security Assets and Infrastructure PPA along with several other activities.

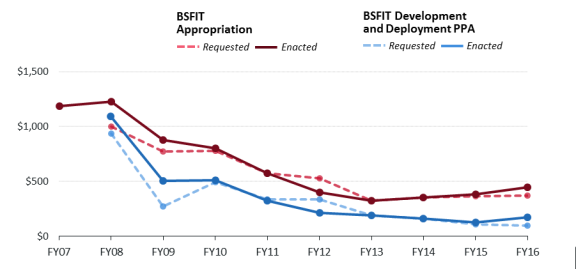

Figure 1 shows the requested and enacted levels for the BSFIT appropriation and the Development and Deployment PPA from FY2008 through FY2016.

Identifying Border Barrier Funding

Despite the new structure of appropriations in the legislative era, an explicit total for border barrier funding cannot be developed from congressional sources alone, as funding measures did not consistently include this level of detail. Both the BSFIT appropriation and the Development and Deployment PPA include more than funding for border barriers. To gain a more precise understanding of spending levels on border barriers in this period, CBP's information is required. CBP has provided a breakdown of its spending on border barriers beginning with FY2007 to the Congressional Research Service.25 The primary program that funded barrier construction in this period was the Tactical Infrastructure (TI) Program.26

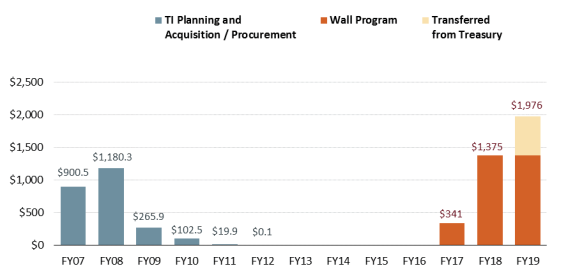

Figure 2 and Table 1 present funding data provided by CBP for border barriers under the TI program. The funding provided in FY2007 to FY2009 resulted in increased border barrier construction (which extended for a few years into the early 2010s). As the funds for construction were expended, CBP transitioned its border barrier activities to primarily maintenance and minor repairs, until FY2017.

|

Figure 2. CBP-Reported Data on Border Barrier Funding, FY2007-FY2016 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Summary of Historical Spending for TI and Wall Programs," email attachment sent to CRS November 26, 2018. Notes: Data provided in Table 1. |

Table 1. CBP-Reported Data on Border Barrier Funding, FY2007-FY2016

Millions of Nominal Dollars of Budget Authority

|

Tactical Infrastructure (TI) Program Total |

TI Acquisition / Procurement, Construction, and Improvements |

TI Operations and Support |

TI Planning |

|||||

|

FY2007 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2008 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2009 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2010 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2011 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2012 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2013 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2014 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2015 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2016 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Summary of Historical Spending for TI and Wall Programs," email attachment sent to CRS November 26, 2018.

Notes: Table presents nominal dollars, rounded to the nearest million. Tactical infrastructure includes roads, pedestrian and vehicle fencing, lighting, low-water crossings, bridges, drainage structures, marine ramps, and other supporting structures. It does not include ports of entry.

CBP indicated in follow-up communications that no further historical data are available, as barrier construction was conducted by several entities within CBP, and not centrally tracked. In addition, the definitions of tactical infrastructure may allow for inclusion of some elements only peripherally related to border barriers. Taking these factors into account, given the limited mileage constructed prior to FY2007 (see Appendix for details), the above data present the best available understanding of appropriations and spending on border barriers in this era.

DHS Border Barriers: Executive Era (2017-Present)

On January 25, 2017, the Trump Administration issued Executive Order 13767, "Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements." Section 2(a) of the EO indicates that it is the policy of the executive branch to "secure the southern border of the United States through the immediate construction of a physical wall on the southern border, monitored and supported by adequate personnel so as to prevent illegal immigration, drug and human trafficking, and acts of terrorism." The EO goes on to define "wall" as "a contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and impassable physical barrier."27

Enacted Appropriations

Changes in Structure

For FY2017, changes were made both in the structure of how funds were appropriated, and how CBP organized those funds among its authorized activities. This complicates efforts to make detailed comparisons in funding levels between the present and time periods prior to FY2016.28

Appropriations

When DHS was established in 2003, components of other agencies were brought together over a matter of months, in the midst of ongoing budget cycles. Rather than developing a new structure of appropriations for the entire department, Congress and the Executive continued to provide resources through existing account structures when possible. CBP's budget structure evolved over the DHS's early years, including the institution of the BSFIT account in FY2007.

At the direction of Congress, in 2014 DHS began to work on a new Common Appropriations Structure (CAS), which would standardize the format of DHS appropriations across components.

After several years of negotiations with Congress, DHS made its first budget request in the CAS for FY2017, and implemented it while operating under the continuing resolutions funding the department in October 2016. This resulted in the BSFIT structure being eliminated, and the funding that had been provided under its appropriation being distributed to PPAs within the CBP Operations and Support (OS) and Procurement, Construction, and Improvements (PC&I) appropriations.

Execution of Funding

Aside from the appropriations structure, changes within CBP's internal account structure occurred during FY2017. The "Wall Program" was established at CBP during FY2017. The Wall Program is a lower-level PPA nested within the new Border Security Assets and Infrastructure activity, which in turn is a part of the CBP PC&I appropriation. According to CBP, the Wall Program oversees the execution of the FY2017 TI program funding and "will be responsible for all future wall construction."29 CBP first directed appropriations to the Wall Program in FY2018 ($1.375 billion).30

CBP's TI Program continues to manage the funding to maintain new and replacement border barriers, as it has since FY2007.

Table 2 shows appropriations for border barriers requested by the Administration and provided by Congress in the DHS appropriations acts. Each fiscal year is discussed in detail after Table 2.

|

Trump Administration Request |

Enacted |

|||

|

FY2017 |

|

|

||

|

FY2018 |

|

|

||

|

FY2019 |

|

|

||

|

FY2020 |

|

|

||

|

Total |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Summary of Historical Spending for TI and Wall Programs," email attachment sent to CRS November 26, 2018; CBP budget Justifications and appropriations conference reports for FY2019-FY2020.

Notes: Table 2 presents nominal dollars, rounded to the nearest million. Each fiscal year is discussed in detail below.

a. This represents the Trump Administration's supplemental appropriations request to begin planning, design, and construction of border barriers.

b. CBP reports that $341 million of FY2017 TI Acquisition / Procurement, Construction, and Improvements funding is for Wall Program requirements, but funding was provided to the TI program, because the Wall program had yet to be established when appropriations were provided.

c. The Trump Administration's original budget request for FY2019 included $1.6 billion for border barrier construction; this was raised during the course of budget negotiations to $5.7 billion.

FY2017

The Trump Administration submitted a supplemental appropriations request in March 2017 for a variety of priorities, including CBP staffing and border wall construction. The request for additional CBP PC&I funding included $1.38 billion, of which $999 million was for "planning, design, and construction of the first installment of the border wall."31

The FY2017 DHS Appropriations bill included a sixth title with the congressional response to the supplemental appropriations request. It included $341.2 million to replace approximately 40 miles of existing primary pedestrian and vehicle barriers along the southwest border "using previously deployed and operationally effective designs, such as currently deployed steel bollard designs, that prioritize agent safety" and to add gates to existing barriers.32

FY2018

The Administration requested $1.72 billion for the Border Security Assets and Infrastructure PPA, including $1.57 million for construction of border barriers. In the FY2018 appropriations measure, Congress provided $1.74 billion, which, according to a House Appropriations Committee summary, included funding for "over 90 miles of physical barrier construction along the southern border—including replacement, bollards, and levee improvements."33 Section 230 of the bill specified the following $1.375 billion in specific projects under the CBP PC&I appropriation:

- $445 million for 25 miles of primary pedestrian levee fencing in Rio Grande Valley (RGV) sector;

- $196 million for primary pedestrian fencing in RGV sector;

- $251 million for secondary replacement fencing in San Diego sector;

- $445 million for replacement of existing primary pedestrian fencing; and

- $38 million for border barrier planning and design.34

The section went on to note that the funding for primary fencing "shall only be available for operationally effective designs deployed as of [May 5, 2017], such as currently deployed steel bollard designs that prioritize agent safety."35

FY2019

The Administration initially requested $1.647 billion for the Border Security Assets and Infrastructure PPA. Budget justification documents noted that $1.6 billion was requested for the border wall.36 The Administration reportedly requested $5.0 billion for the wall from Republican congressional leadership;37 no publicly available modification of its request was presented to Congress until January 6, 2019. At that time, in the midst of a lapse in annual appropriations for various departments and agencies of the federal government due in part to conflict over border barrier funding, the acting head of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) submitted a letter seeking $7 billion in additional border related funding, including $4.1 billion more for "the wall" than the Administration originally requested.38 The letter indicated that the total request of $5.7 billion would pay for "approximately 234 miles of new physical barrier and fully fund the top 10 priorities in CBP's Border Security Improvement Plan."

P.L. 116-6, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019, included $1.375 billion for CBP "for the construction of primary pedestrian fencing, including levee pedestrian fencing, in the Rio Grande Valley Sector." Funding could only be used for "operationally effective designs deployed as of [May 5, 2017], such as currently deployed steel bollard designs that prioritize agent safety."39

Border Barrier Funding Outside the Appropriations Process

The same day that the President signed the FY2019 consolidated appropriations act into law, he declared a national emergency on the southern border of the United States. A fact sheet accompanying the declaration indicated the President's intent to make additional funding available for border barriers through three methods, sequentially. These methods and related actions are:

- 1. Drawing about $601 million from the Treasury Forfeiture Fund

- A letter from the Department of the Treasury on February 15, 2019, that accompanied the Strategic Support spending proposal for FY2019 indicated that those funds would be made available to DHS for "law enforcement border security efforts" ($242 million available March 2, and $359 million after additional forfeitures were received).

- Treasury Forfeiture Fund assets have been made available to support DHS missions in the past, although not on this scale—CBP does not require an emergency designation to receive or use these funds in support of its law enforcement missions.

- 2. Making up to $2.5 billion available through the Department of Defense's support for counterdrug activities (authorized under 10 U.S.C. §284)40

- $1 billion has been reprogrammed within the Department of Defense to its Drug Interdiction and Counter Drug Activities account, and that funding, in turn, was transferred for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to do certain DHS-requested work on border barriers.41

- On May 10, 2019, the Department of Defense announced an additional $1.5 billion reprogramming of funding that had been dedicated to a variety of initiatives, including training and equipping Afghan security forces, programs to dismantle chemical weapons, and other activity for which savings or program delays had been identified. The DOD announcement indicated that the funding would construct an additional 80 miles of border barriers.

- Use of both of these tranches of reprogrammed funds to pay for border barrier projects had been blocked by a court injunction until July 26, 2019, when the Supreme Court ruled that the government could proceed with the use of the funds while a lower court determines the legality of the transfer that made the funds available.42

- For additional information on the injunction, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10310, Supreme Court Stays Injunction That Had Blocked a Portion of the Administration's Border Wall Funding.

- 3. Reallocating up to $3.6 billion from various military construction projects under the authority invoked by the emergency declaration43

- No public information is available that indicates that this authority has been exercised as of August 27, 2019.

On September 3, 2019, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper issued a memorandum with the determination that "11 military construction projects … along the international border with Mexico, with an estimated total cost of $3.6 billion, are necessary to support the use of the armed forces in connection with the national emergency [at the southern border]."44

The memorandum indicates $1.8 billion in unobligated military construction funding for overseas projects would be made available immediately, while $1.8 billion in domestic military construction projects would be provided once it is needed.45 FY2020

In February 2019, The Administration requested $5 billion in border barrier funding for FY2020, to support the construction of approximately 206 miles of border wall system.44

The House Appropriations Committee has responded to this by providing no funding in its FY2020 bill for border barriers. In addition, the bill restricts the ability to transfer or reprogram funds for border barrier construction and proposes to rescind $601 million from funding appropriated for border barriers in FY2019.45

Comparing DHS Border Barrier Funding Across Eras

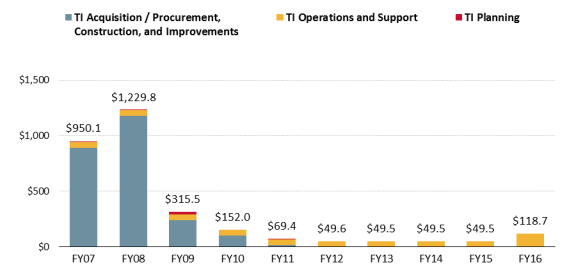

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the total funding made available in the first and second eras of DHS efforts to support planning and construction of barriers on the U.S.-Mexico border.

This comparison is made with two important caveats: the data sources and funding structures are different in the two eras. In the legislative era (FY2007-FY2016), detailed information was only available from CBP, and was tracked for "tactical infrastructure," which included funding for border roads and other TI. In the executive era (FY2017 to the present), data from CBP and appropriations measures (which has been more detailed with respect to barrier planning and construction) are generally consistent, but the Administration uses the specifically defined "border wall" program to track most of the funding. A small amount of funding for barrier replacement and supporting infrastructure was provided through the tactical infrastructure PPA in FY2018.46

Questions Relevant to Future DHS Border Barrier Funding

Section 4 of E.O. 13767, "Physical Security of the Southern Border of the United States," focuses almost entirely on the construction of "a physical wall" on the U.S.-Mexico border as a means of obtaining operational control of the nearly 2,000-mile border. CBP has indicated that it cannot provide authoritative historical data prior to FY2007 on the level of funding invested in border barrier planning and construction. However, as this report notes, the more than $3 billion in appropriations provided by Congress to CBP for border barrier planning and construction during the Trump Administration exceeds the amount provided for those purposes in the BSFIT account for the 10 years from FY2007 to FY2016 by $618 million. Almost all of FY2017 to FY2019 funding is for improvements to the more than 650 miles of existing barriers at the border, with a portion of the funds being available for new construction.

Despite the resources provided, the Administration has taken unprecedented steps—noted above—in an attempt to more than double the funding level appropriated to CBP by Congress for barriers in that three-year period.

Generally, the Administration, in its discussion about border barriers, relies on the U.S. Border Patrol Impedance and Denial Prioritization Strategy, which includes a list of projects for barrier construction. There are no known authoritative cost estimates for the total construction or operation and maintenance costs of these projects if they are all completed, or publicly available assessments of how completion of various projects might affect CBP's operational costs. Furthermore, GAO reported in 2016 that border barriers' contributions to CBP goals were not being adequately measured,4749 and in 2018 that CBP's methodology for prioritizing border barrier deployments did not use cost estimates that included data on topography, land ownership, and other factors that could impact the costs of individual barrier projects.48

Given that the Administration's stated intent is to expand the amount of border barriers on the southwest border, and that this issue will likely be part of debates on the budgets for the current and future fiscal years, Congress may wish to obtain the following information and explore the following questions in assessing border barrier funding proposals:

- 1. What are the projected operation and maintenance costs for the existing southwest border barriers? How will those change with additional replacements, upgrades, or new construction of barriers?

- 2. What are the projected land acquisition and construction costs of CBP's remaining top priority border barrier projects, based on unique topography, land ownership, and strategic intent of the projects? What steps is CBP taking to control the growth of those costs? Who within the Administration is providing oversight of how these funds are used, and are they reporting their findings to Congress?

- 3. Are existing barriers and completed improvements having measurable impacts on attempted illegal entry into the U.S. and smuggling of contraband? How are CBP and other stakeholders making their assessments? Is CBP getting its desired tactical or strategic outcomes?

- 4. Given the answers to the first three sets of questions, are the operational benefits worth the financial and operational costs, or are there more efficient ways to achieve the desired tactical or strategic outcomes?

- 5. How should Congress respond to the Administration's exercise of existing reprogramming and transfer authorities to fund certain border barrier work above the amount Congress provided to CBP for that purpose?

Appendix. Tracking Barrier Construction on the U.S.-Mexico Border

The United States' southern border with Mexico runs for nearly 2,000 miles over diverse terrain, through varied population densities, and across discontinuous sections of public, private, and tribal land ownership.4951 The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is primarily responsible for border security, including the construction and maintenance of tactical infrastructure, but also the installation and monitoring of surveillance technology, and the deployment of border patrol agents to impede unlawful entries of people and contraband into the United States (e.g., unauthorized migrants, terrorists, firearms, and narcotics).

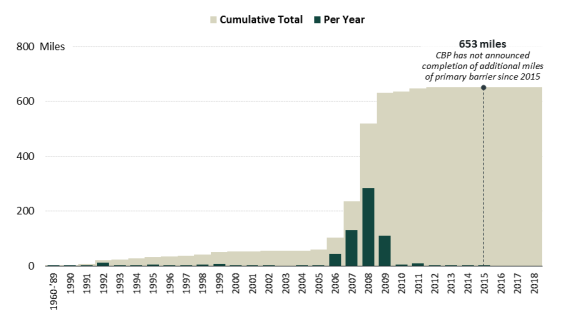

Built barriers, such as fencing, are a relatively new feature on the southern border. These structures vary in age, purpose, form, and location. At the end of FY2015, approximately 653 miles—roughly one-third of the international boundary—had a primary layer of barriers.5052 Approximately 300 miles of the "primary fence" is designed to prevent vehicles from entering, and approximately 350 additional miles is designed to block people on foot—"pedestrian fencing." CBP uses various materials for pedestrian fencing, including bollard, steel mesh, and chain link, and employs bollard and Normandy-style fencing for vehicle barriers.5153 Across 37 discontinuous miles, the primary layer is backed by a secondary layer of pedestrian fencing as well as an additional 14 miles of tertiary fencing (typically to delineate property lines).

About 82% of primary pedestrian fencing and 75% of primary vehicle fencing was constructed between 2006 and 2011—these barriers are considered "modern."5254 Approximately 90% of the primary fencing is located in the five contiguous Border Patrol sectors located in California, Arizona, and New Mexico, while the remaining 10% is in the four eastern sectors (largely in Texas) where the Rio Grande River delineates most of the border. CBP has not announced the completion of any additional miles of primary fencing since the 653 miles were completed in 2015, but sections of legacy fencing and breached areas have been replaced or repaired and other improvements have been made.

An interactive online project by inewsource (a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative newsroom in San Diego) and KPBS (a Public Broadcasting Service television and radio station in San Diego, California) used data obtained via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to Customs and Border Protection to account for every mile of existing border fencing by the year built.5355 The data are used in this appendix to produce Figure A-1 showing the number of miles of primary border barrier constructed for the period 1960-2018 (annual data shown in Table A-1).

Small areas of the border had fencing prior to 1990. By 1993, fencing in the San Diego area had been completed, covering the first 14 miles of the border east from the Pacific Ocean and a few other areas.5456 Under the provisions of IIRIRA, the Secretary of Homeland Security—and, prior to 2003, the Attorney General—has the discretion to determine the appropriate amount of additional barriers to build, as well as their location. Approximately 40 additional miles of primary fence were constructed on the southern border through 2005. The vast majority of the existing primary barriers—more than 525 miles—were constructed between 2007 and 2009 (see Table A-1 and Figure A-1). Since 2015, no additional miles of primary barriers have been constructed to date. The FY2017-FY2019 appropriated funds has primarily gone to repair, replace, or upgrade existing border barriers, rather than construction of additional miles of primary barrier. CBP announced on August 8, 2019, a contract award for building 11 miles of levee wall system (steel bollard on top of a concrete wall) in areas where no barriers currently exist in the Rio Grande Valley Sector.55

|

Figure A-1. Annual and Cumulative Miles of Primary Barriers and Year Constructed, Southwest Border, 1990-2018 |

|

|

Source: inewsource/KPBS, America's Wall, https://www.kpbs.org/news/2017/nov/13/americas-wall/. Notes: Construction data are in calendar years for fencing that existed as of the date of the project. Primary barriers include pedestrian and vehicle fencing combined. The data were provided by Customs and Border Protection via a Freedom of Information Act request to inewsource/KPBS to create the interactive, "America's Wall." The files provided to inewsource/KPBS included digital map files of sections of barriers, and information such as type of fencing, year construction was completed, and the location in which it was built. The length of each section of fencing was recorded in an "internal unit"—something other than feet or meters—which required inewsource/KPBS to use a mapping software to extract the length in feet for each section of wall. CRS could not verify years prior to 1990. For more information on the methodology used, see https://www.kpbs.org/news/2017/nov/13/americas-wall-how-we-crunched-numbers/. |

|

Year |

Primary Fencing |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

— |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

— |

|||

|

|

— |

|||

|

|

— |

|||

|

|

|

Source: inewsource/KPBS, "America's Wall," https://www.kpbs.org/news/2017/nov/13/americas-wall/.

Notes: Construction data are in calendar years for fencing that existed as of the date of the project. Primary barriers include pedestrian and vehicle fencing combined. The data were provided by Customs and Border Protection via a Freedom of Information Act request to inewsource/KPBS to create the interactive, "America's Wall." The files provided to inewsource/KPBS included digital map files of sections of barriers, and information such as type of fencing, year construction was completed, and the location in which it was built. The length of each section of fencing was recorded in an "internal unit"—something other than feet or meters—which required inewsource/KPBS to use a mapping software to extract the length in feet for each section of wall. CRS could not verify years prior to 1990. For more information on the methodology used, see https://www.kpbs.org/news/2017/nov/13/americas-wall-how-we-crunched-numbers/.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Office of the Historian, Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations, U.S. Department of State, Gadsden Purchase 1853-1854, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/gadsden-purchase and International Boundary; and Water Commission website, "Treaties Between the U.S. and Mexico," https://www.ibwc.gov/Treaties_Minutes/treaties.html, as downloaded on July 8, 2019. (22 U.S.C. |

|||

| 2. |

Act of May 28, 1924 (43 Stat. 240). |

|||

| 3. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Border Patrol History," https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/along-us-borders/history. |

|||

| 4. |

Immigration Act of May 26, 1924 (43 Stat. 153). |

|||

| 5. |

Meyers, Deborah Waller, "From Horseback to High-Tech: U.S. Border Enforcement," Migration Policy Institute, November 2005, p. 2, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/Insight-7-Meyers.pdf. |

|||

| 6. |

See Douglas S. Massey, Jorge Durand, and Nolan J. Malone, Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Migration in an Era of Economic Integration (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2003); and Kitty Calavita, Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the INS (1992) (New York: Routledge, 1992). |

|||

| 7. |

Meyers, pp. 2-4. |

|||

| 8. |

The barrier, originally seven miles long, was increased to 14 miles in 1993 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, extending it into the Pacific Ocean. Meyers, p. 5. |

|||

| 9. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, INS' Southwest Border Strategy: Resource and Impact Issues Remain After Seven Years, GAO-01-842, August 2, 2001, p. 1, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-01-842. |

|||

| 10. |

U.S. Border Patrol, Border Patrol Strategic Plan: 1994 and Beyond, July 1994, p. 6, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=721845. |

|||

| 11. |

CRS Report R43975, Barriers Along the U.S. Borders: Key Authorities and Requirements, by Michael John Garcia. |

|||

| 12. |

The authorities granted by this section now rest with the Secretary of DHS. See P.L. 107-296, §§102(a), 441, 1512(d), and 1517 (references to the Attorney General or Commissioner in statute and regulations are deemed to refer to the Secretary). |

|||

| 13. |

P.L. 104-208, Division C, §102(a) and (b); 8 U.S.C. §1103 note. |

|||

| 14. |

CBP was established pursuant to reorganization authority provided in Sec. 1502 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296). An initial reorganization plan, altering the structure outlined in P.L. 107-296, was submitted on November 25, 2002, and was then modified on January 30, 2003, after Bush Administration consultations with Secretary of Homeland Security-designate Tom Ridge. The reorganization as modified restructured the Customs Service and the Bureau of Border Security into the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection. Permanent statutory authorization was provided in P.L. 114-125 (130 Stat. 122), 6 U.S.C. §211. |

|||

| 15. |

119 Stat. 306. Also see, CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10111, District Court Decision May Help Pave the Way for Trump Administration's Border Wall Plans, by Adam Vann. |

|||

| 16. |

See Sen. Arlen Specter, Sen. Patrick Leahy, Sen. John Kerry, and Sen. John McCain, "Secure Fence Act of 2006—Resumed," remarks in the Senate, Congressional Record, vol. 152 (September 29, 2006), pp. S10609-S10613. |

|||

| 17. |

In its first two annual appropriations acts, CBP's construction account was dedicated to the Border Patrol, but little detailed information was provided regarding specific projects. The appropriations committees requested a detailed priority list of projects in the FY2004 conference report (H.Rept. 108-280, p. 31), and noted in FY2005 that it had not received it (H.Rept. 108-774, p. 43). The account received slightly more than $90 million in each of its first two years—funding the account at the requested level—with no special direction provided on border barriers. |

|||

| 18. |

H.Rept. 109-241. $35 million was also provided for unspecified tactical infrastructure in CBP's Tucson Sector. Information on Border Patrol sectors can be found at https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/along-us-borders/border-patrol-sectors, and a map is available in GAO-18-614 (https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-614), on p. 8. |

|||

| 19. |

121 Stat. 2090. |

|||

| 20. |

121 Stat. 2091. |

|||

| 21. |

H.Rept. 109-699, pp. 129-130. |

|||

| 22. |

PPAs—short for "Programs, Projects, or Activities"—are subdivisions of appropriations. |

|||

| 23. |

H.Rept. 109-699, p. 130. For a detailed discussion of how the 2008 Appropriations Act amended IIRIRA and modified fencing requirements, see CRS Report R43975, Barriers Along the U.S. Borders: Key Authorities and Requirements, by Michael John Garcia, beginning on p. 9 and Appendix A for current language. |

|||

| 24. |

For detailed information on the shift to the CAS, see CRS Report R44621, Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2017, coordinated by William L. Painter. |

|||

| 25. |

Email to CRS from CBP Office of Congressional Affairs, November 26, 2018. |

|||

| 26. |

CBP, in contracting documents, includes a broad range of things in tactical infrastructure, such as roads, pedestrian and vehicle fencing, lighting, low-water crossings, bridges, drainage structures, marine ramps, and other supporting structures. It does not include ports of entry. |

|||

| 27. |

Executive Order 13767, "Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements," 82 Federal Register 8793-8797, January 30, 2017. |

|||

| 28. |

Data on FY2016 enacted appropriations transcribed into the new DHS budget structure were available in the detail table at the end of the explanatory statement accompanying the FY2017 Omnibus Appropriations Act, which included the Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2017 as Division F. See U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, committee print, 115th Cong., 1st sess., H.Prt. 115-25-289 (Washington: GPO, 2017), pp. 973-976 for CBP's appropriations in the CAS structure. |

|||

| 29. |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|||

| 30. |

CBP reports that $341 million of FY2017 TI Acquisition funding was for Wall Program requirements, but funding was provided to the TI program, because the Wall Program had yet to be established when appropriations were provided. |

|||

| 31. |

Letter from Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, to The Honorable Paul Ryan, Speaker of the House of Representatives, March 16, 2017, p. 3 of the enclosure, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/amendment_03_16_18.pdf. |

|||

| 32. |

P.L. 115-31, 131 Stat. 433-434. |

|||

| 33. |

House Committee on Appropriations, "Fiscal Year 2018 Homeland Security Bill," press release, March 21, 2018, https://appropriations.house.gov/uploadedfiles/03.21.18_fy18_omnibus_-_homeland_security_-_summary.pdf. |

|||

| 34. |

P.L. 115-141, Division F, Sec. 230(a)(1)-(5). |

|||

| 35. |

Ibid. |

|||

| 36. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection Budget Overview: Fiscal Year 2019 Congressional Justification, Washington, DC, p. CBP-16, https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2019. |

|||

| 37. |

Jennifer Shutt, "Trump, House GOP Dig In on Spending Bills, Border Wall," CQ News, November 27, 2018, https://plus.cq.com/doc/news-5420430?11. |

|||

| 38. |

Letter from Russell T. Vought, Acting Director, Office of Management and Budget, to Sen. Richard Shelby, Chairman, Committee on Appropriations, |

|||

| 39. | ||||

| 40. |

For additional information on this authority, see CRS Insight IN11052, The Defense Department and 10 U.S.C. 284: Legislative Origins and Funding Questions, by Liana W. Rosen. |

|||

| 41. |

Standard CBP practice for construction of border barriers is that the real estate and construction contracting has been handled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, with funding provided by CBP by transfer under the Economy Act. For more details, see CRS In Focus IF11224, Army Corps of Engineers and U.S. Southern Border Barriers, by Nicole T. Carter. |

|||

| 42. |

Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Plaintiffs' Motion for Preliminary Injunction at 8, Sierra Club v. Trump, Case No. 4:19-cv-00892-HSG (N.D. Cal. June 28, 2019), [ECF No. 185], https://www.crs.gov/products/Documents/8_Permanent_Injunction_Order/pdf. |

|||

| 43. |

CRS Insight IN11017, Military Construction Funding in the Event of a National Emergency, by Michael J. Vassalotti and Brendan W. McGarry. |

|||

| 44. |

Memorandum from Mark T. Esper, Secretary of Defense, to Acting Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer, "Military Construction Necessary to Support the Use of the Armed Forces in Addressing the National Emergency at the Southern Border," September 3, 2019.

Ibid. |

|||

|

H.R. 3931, Sec. 536. |

||||

|

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection Procurement, Construction and Improvements: Fiscal Year 2020 Congressional Justification, Washington, DC, p. CBP-PC&I-20, https://www.dhs.gov/publication/congressional-budget-justification-fy-2020. |

||||

|

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Better Assess Fencing's Contributions to Operations and Provide Guidance for Identifying Capability Gaps, GAO-17-331, February 17, 2017, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/682838.pdf. (Redacted version of original law enforcement-sensitive 2016 report.) |

||||

|

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Southwest Border Security: CBP Is Evaluating Designs and Locations for Border Barriers but Is Proceeding Without Key Information, GAO-18-614, July 30, 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-614. |

||||

|

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Better Assess Fencing's Contributions to Operations and Provide Guidance for Identifying Capability Gaps, 17-331, February 2017, Hereinafter, "GAO 2017." |

||||

|

The figure of 653 primary miles of fencing is derived from inewsource/KPBS's data source (described below) and differs minimally from GAO's 654 miles. See GAO 2017, p. 6. |

||||

|

GAO 2017; see pp. 11-12 for images of barrier types and materials for pedestrian/vehicle and modern/legacy fencing. |

||||

|

GAO refers to "any fencing designs used prior to CBP implementing requirements of the Secure Fence Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-367, 120 Stat. 2638) as 'legacy' fencing and any fencing deployed subsequently as 'modern' fencing designs." See GAO 2017, p. 4. |

||||

|

inewsource/KPBS, "America's Wall," https://www.kpbs.org/news/2017/nov/13/americas-wall/. |

||||

|

CRS Report R43975, Barriers Along the U.S. Borders: Key Authorities and Requirements, by Michael John Garcia, p. 4. |

||||

|

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Contract Awards for New Levee Wall and Border Wall Gates in the Rio Grande Valley," press release, August 8, 2019. |