El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from August 14, 2019 to July 1, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

- Introduction

- Politics and Governance

- Postconflict Era of ARENA and FMLN Rule

- Bukele Administration

- Security Conditions

- Criminal Justice System

- Secure El Salvador Plan; "Extraordinary Measures" in Prisons

- Bukele's Security Plan

- Military Involvement in Public Security Efforts

- Economic and Social Conditions

- Human Rights

- Recent Human Rights Violations

- Confronting Past Human Rights Violations

- U.S. Relations

- U.S. Foreign Assistance

- FY2019 Appropriations Legislation

- Suspension of Assistance and FY2020 Appropriations

- Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Investment Compact

- Department of Defense Assistance

- Migration Issues

- Recent Migration Flows

- Human Trafficking and Alien Smuggling

- Removals, Temporary Protected Status, and Deferred Action for Child Arrivals

- Security Cooperation

- Counternarcotics

- Gangs

- Trade Relations

- Human Rights Cases: Former Salvadoran Officials Tried in the United States

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

July 1, 2020

Congress has had significant interest in El Salvador, a small smal Central American nation that has had a large percentage of its population living in the United States since the country'

Clare Ribando Seelke

country’s civil conflict (1980-1992). During the 1980s, the U.S. government spent billions

Specialist in Latin

bil ions of dollars supporting the Salvadoran government'’s counterinsurgency efforts

American Affairs

against the leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). The United

States later supported a 1992 peace accord that ended the conflict and transformed the

FMLN into a political party. Despite periodic tensions, the United States worked with two consecutive FMLN administrations (2009-2019), but. As bilateral efforts werehave been unable to prevent significant outflows of migrants from the country.

irregular emigration from El Salvador, the Trump Administration has focused relations with President Nayib Bukele on

migration-related issues.

Domestic Situation

Domestic Situation

On June 1, 2019, Nayib Bukele, a 37-year-old businessman and former mayor of San Salvador, took office for a five-year presidential term. Bukele won 53% of the vote in the February 2019 election, standing for the Grand Alliance Al iance for National Unity (GANA) party. Elected on an anticorruption platform, Bukele is the first president in 30 years to be elected without the backing of the conservative National Republic Alliance Al iance (ARENA) or the FMLN parties. Bukele succeeded Salvador Sánchez Cerén (FMLN), who presided over a period of moderate economic

growth (averaging 2.3%), ongoing security challengeschal enges, and political polarization.

President Bukele has promised to reduce crime and attract investment, but his lack of support in the National Assembly (GANA has 11 of 84 seats) has led to several executive-legislative clashes. Homicides continued to

trend downward during his first year in office (to a rate of 36 per 100,000), but extortion rates rose. El Salvador’s economy grew 2.4% in 2019 but is expected to decline by 5.4% this year due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Bukele has remained popular, but his government’s refusal to abide by legislative and

Supreme Court decisions and his harsh COVID-19 quarantine have received significant international criticism.

U.S. Policy

Since FY2016, Congress has appropriated nearly $3.1 bil ion, at least $411 mil ion of which has been al ocated to El Salvador, through the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America to address the underlying drivers of migration. In March 2019, the Administration suspended most foreign aid to El Salvador (and to Guatemala and

Honduras) after criticizing the government’s failure to address irregular migration. After signing several migration-related agreements with the Bukele government in 2019, the Administration informed Congress that it intends to release some suspended assistance and provide smal amounts of new targeted aid for El Salvador. U.S. funds aim to deter migration, support President Bukele’s security strategy, and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The FY2021 budget does not specify a funding amount for El Salvador but asks for $377 mil ion for

the Central American region.

In addition to scaled-back U.S. assistance, shifts in U.S. immigration policies have tested bilateral relations. The Administration’Assembly (GANA has 11 of 84 seats) could present challenges. Bukele has proposed infrastructure projects that could help the country take better advantage of the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR); critics question how these projects will be financed. Bukele has criticized repressive governments in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Honduras. During a July 2019 visit with Secretary of State Michael Pompeo, President Bukele vowed to improve relations with the United States by working bilaterally to address gangs, drugs, and immigration and seeking investment rather than U.S. assistance.

U.S. Policy

U.S. policy in El Salvador has focused on promoting economic prosperity, improving security, and strengthening governance under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America. Congress has appropriated nearly $2.6 billion for the strategy since FY2016, at least $410 million of which has been allocated to El Salvador. The Trump Administration has requested $445 million for the strategy in FY2020, including at least $45.7 million for El Salvador, and an unspecified amount allocated for the country under the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI).

Future U.S. engagement in El Salvador is uncertain, however, as the Administration announced in March 2019 that it intended to end foreign assistance programs in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras due to continued unauthorized U.S.-bound migration. In June 2019, the Administration identified FY2017 and FY2018 bilateral and regional funds subject to withholding or reprogramming. It is unclear how funds appropriated for FY2019 in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) and FY2020 funds may be affected. Bilateral relations also have been tested by shifts in U.S. immigration policies, including the Trump Administration's decision to rescind the temporary protected status (TPS) designation that has shielded up to s decision to rescind the temporary protected status (TPS) designation that has shielded up to

250,000 Salvadorans from removal since 2001 is a major concern for the Bukele government. A House-passed bill,

bil , H.R. 6, would allowal ow certain TPS designees to apply for permanent resident status.

The 116th Congress could influence the future of U.S. policy toward El Salvador. Legislative initiatives that have been introduced—including House-passed H.R. 2615, as well as S. 1445, and H.R. 2836/S. 1781—would authorize foreign assistance for certain activities in Central America. Congress may consider initiatives to prevent the Administration from reprogramming FY2019 funds as it considers the Administration's FY2020 budget request. The House-passed FY2020 minibus, H.R. 2740, would appropriate $540.9 million for the Central America strategy, including at least $45.7 million for El Salvador and additional funding for the country under CARSI.

See also CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress, by Peter J. Meyer.

Introduction

A small

The 116th Congress has considered various measures affecting U.S. policy toward El Salvador. In December 2019,

Congress enacted the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94), which provides $519.9 mil ion for Central America, including at least $73 mil ion for El Salvador. Several other measures Congress may consider would expand in-country refugee processing in the Northern Triangle (H.R. 2347 and H.R. 3731) and authorize foreign assistance for certain activities in Central America (H.R. 2615, H.R. 2836, H.R. 3524, S. 1445,

and S. 1781).

See also CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress, by

Peter J. Meyer.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 33 link to page 6 link to page 10 link to page 26 link to page 22 link to page 34 El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Politics and Governance ................................................................................................... 1

Postconflict Era of ARENA and FMLN Rule ................................................................. 1 Bukele Administration................................................................................................ 3

Security Conditions ......................................................................................................... 5

Criminal Justice System ............................................................................................. 7 Bukele’s Security Plan ............................................................................................... 9 Economic and Social Conditions................................................................................ 10

Human Rights .............................................................................................................. 14

Recent Human Rights Violations................................................................................ 14 Confronting Past Human Rights Violations .................................................................. 15

U.S. Relations .............................................................................................................. 17

U.S. Foreign Assistance ............................................................................................ 17

Suspension of Assistance ..................................................................................... 19 FY2020 Appropriations and FY2021 Budget Request .............................................. 20 COVID-19 Assistance and Humanitarian Aid for Tropical Storm Amanda................... 20 Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Investment Compact ............................... 21

Migration Issues ...................................................................................................... 21

Recent Migration Flows ...................................................................................... 21 Human Trafficking and Alien Smuggling ............................................................... 22 Removals, Temporary Protected Status, and Deferred Action for Child Arrivals ........... 23 Asylum Processing Capacity in El Salvador and the U.S.-El Salvador Asylum

Cooperation Agreement .................................................................................... 25

Security Cooperation................................................................................................ 26

Counternarcotics ................................................................................................ 26 Gangs and Citizen Security .................................................................................. 27

Trade Relations ....................................................................................................... 28

Human Rights Cases: Former Salvadoran Officials Tried in the United States ................... 28 Outlook.................................................................................................................. 29

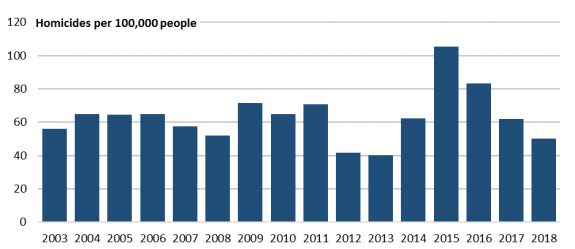

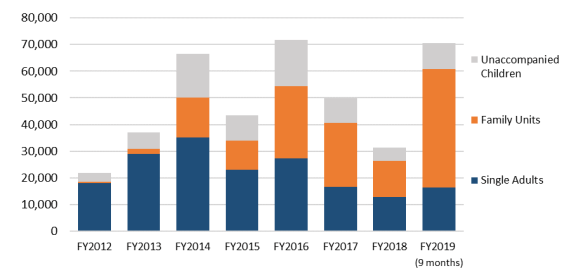

Figures Figure 1. Map of El Salvador and Key Country Data ............................................................ 2 Figure 2. Homicide Rate in El Salvador: 2004-2019 ............................................................. 6 Figure 3. U.S. Apprehensions of Salvadoran Nationals: FY2009-FY2020 (May)..................... 22

Tables Table 1. U.S. Assistance to El Salvador: FY2016-FY2021 ................................................... 18

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 30

Congressional Research Service

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 link to page 21 El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Introduction A smal , densely populated Central American country that has deep historical, familial, and economic ties to the United States, El Salvador has been a focus of sustained congressional interest (seesee Figure 1 for a map andand key country data).11 After a troubled history of authoritarian rule and a civil war (1980-1992), El Salvador has established a multiparty democracy, albeit with significant challengeschal enges, particularly related to insecurity.22 A 1992 peace accord ended the war and

assimilated the leftist Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) guerrillaguerril a movement into the political process as a political party. The conservative Nationalist Republican Alliance Al iance (ARENA) ruled until 2009, before ceding power to two consecutive FMLN administrations. With both the FMLN and ARENA tarnished by revelations of corruption by former presidents,

Salvadorans elected Nayib Bukele, an outsider who took office on June 1, 2019.3

3

President Bukele, a businessman and former mayor of San Salvador, left the FMLN and captured a first-round victory standing for the Grand AllianceAl iance for National Unity (GANA) party in February 2019 presidential elections.44 Born in 1981, Bukele is the first president of El Salvador

from a generation that did not come of age politically political y during the civil conflict in which more than 70,000 Salvadorans died.5 Bukele has battled with the legislature (where GANA holds 11 of 84 seats) and the Supreme Court over funds he sought for his security plan and his aggressive enforcement of a Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) quarantine. Although he remains popular, Bukele’s critics are concerned about his authoritarian tendencies and lack of respect for

other branches of government.670,000 Salvadorans died.5 Buoyed by popular support, Bukele has a strong mandate to address the serious governance, security, and economic challenges that have fueled emigration from El Salvador.6 In contrast to the FMLN, President Bukele has adopted a pro-

United States agenda and pledged to stop irregular migration (see “United States agenda, which he highlighted during a July 21, 2019, visit with U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo (see "U.S. Relations,"U.S. Relations,” below).

below).7 Bukele's power is likely to be constrained, however, by GANA's limited representation (11 of 84 seats) in the legislature.

This report examines political, economic, security, and human rights conditions in El Salvador. It then analyzes selected issues in U.S.-Salvadoran relations that have been of particular interest to Congress, including foreign assistance, migration, security cooperation in addressing gangs and counternarcotics issues, human rights, and trade.

Politics and Governance

Postconflict Era of ARENA and FMLN Rule

Polarization between the FMLN, a party formed by former guerillasgueril as, and ARENA, a party aligned with the military, has been the primary dynamic in Salvadoran politics since the civil conflict. From 1994 to 2008, successive ARENA governments sought to rebuild democracy and

1 For historical background on El Salvador, see Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, El Salvador: A Country Study, ed. Richard Haggerty (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1990). 2 Priscilla B. Hayner, Unspeakable Truths: Facing the Challenge of Truth Commissions (New York, NY: Routledge, 2002); Diana Villiers Negroponte, Seeking Peace in El Salvador: The Struggle to Reconstruct a Nation at the End of the Cold War (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

3 Nelson Renteria and Noe T orres, “Outsider wins El Salvador Presidency, Breaking two-party System,” Reuters, February 3, 2019. 4 Charles T . Call, The Significance of Nayib Bukele’s Surprising Election as President of El Salvador, Brookings Institution, February 5, 2019.

5 United Nations Commission on the T ruth for El Salvador, From Madness to Hope: The 12-Year War in El Salvador: Report of the Com m ission on the Truth for El Salvador, 1993.

6 “Hungry House: Nayib Bukele’s Power Grab in El Salvador,” The Economist, May 6, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

1

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

From 1994 to 2008, successive ARENA governments sought to rebuild democracy and implement market-friendly economic reforms. ARENA proved to be a reliable U.S. allyal y but did not effectively address inequality, violence, andor corruption. Development indicators generally general y improved, but natural disasters, including earthquakes in 2001 and periodic hurricanes, hindered progress. Moreover, despite ARENA'’s probusiness policies, economic growth averaged 2.4%

over the postwar years in which it governed.8

7 Figure 1. Map of El Salvador and Key Country Data |

|

|

Geography |

Geography

Area: 8,008 sq. mi. Capital: San Salvador |

|

Health |

People

Population: 6.5 mil ion (CEPAL, 2020) Life Expectancy: CEPAL, 2020) Infant Poverty: 29.2% (WB, 2017) |

|

Economy |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): $26.0 billion (IMF, 2018) GDP Composition by Sector: agriculture, 12%; industry, 27.7%; services, 60.3% (CIA, 2017) Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita: $3,790 (IMF, 2017) Key Export Partners: United States (44%), Honduras (15%), Guatemala (14%) (GTA, 2018)

|

SourceTDM, 2019)

Sources: Graphic created by CRS using data from the World Bank (WBU.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Global Trade Atlas (GTA), and the CIA World Fact Book (CIA).

and El Salvador’s Central Bank data downloaded from Trade Data Monitor (TDM).

The attorney general'’s office has brought cases against the two most recent ARENA presidents. Francisco Flores (1999-2004) passed away in January 2016 while awaiting trial for allegedly al egedly embezzling donations from Taiwan destined for earthquake relief. In August 2018, former

president Anthony ("Tony"“Tony”) Saca (2004-2009) pled guilty to charges of money laundering and

7 International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019.

Congressional Research Service

2

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

embezzlement of some $300 mil ionembezzlement of some $300 million. Saca, who started the GANA party in 2010 after being expelled

expel ed from ARENA, is now serving a 10-year prison sentence.

From 2009 to 2014, Mauricio Funes

Mauricio Funes (2009-2014), a former journalist, served as El Salvador'’s first FMLN president.

Funes remained popular throughout his term, asand his government reduced poverty and inequality (see "Economic and Social Conditions"). The government expanded crime prevention programs and community policing, but it also supported and then later disavowed a failed gang truce as it struggled to reduce gang-related violence (see "Security Conditions," below).9 gang truce.8 In 2016, the attorney general'’s office began investigating Funes for al egedlyfor allegedly embezzling more than $350 million mil ion in public funds. He received political asylum in Nicaragua in 2016

Nicaragua, but Salvadoran officials have since sought to have him extradited.10

sought his extradition.9

Salvador Sánchez Cerén (2014-2019), a former guerrillaguerril a commander, failed to implement most of his his inaugural pledges to boost social and infrastructure spending due, in part, to El Salvador'’s severe fiscal constraints and his party'’s lack of a congressional majority. Many observers maintain that Sánchez Cerén, who faced health challenges, did not demonstrate strong leadership. During his term, El Salvador

continued to contend with difficult security conditions despite reductions in homicides since 2015, low investment, and polarization between the executive and the ARENA-led National Assembly.10 Aggressive anti-gangAssembly.11 Aggressive antigang efforts led to extrajudicial killings kil ings by security forces.1211 The

FMLN performed poorly in March 2018 legislative elections. In May 2019, only 15% of Salvadorans polled said that Sanchez Cerén had governed well.13

Under Sánchez Cerén, El Salvador continued to strengthen its ties with Cuba and Venezuela and abandoned long-standing ties with Taiwan to establish diplomatic relations with China. Illicit Il icit funds reportedly flowed from Venezuela'’s state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA) to its Salvadoran subsidiary (Alba Petróleos) and some FMLN politicians, which raised U.S. concerns and

resulted in U.S. sanctions on the company.1412 The Trump Administration criticized the Salvadoran government'government’s August 2018 decision to abandon relations with Taiwan in favor of China,

particularly for the "“non-transparent"” way in which the decision took place.15

13

Bukele Administration On February 3, 2019, Nayib Bukele, standing for the GANA party, won 53% of the vote, wel ahead of Carlos Cal eja (ARENA-led coalition), with 31.8%, and Hugo Mártinez (FMLN), with 14.4%. Bukele’s first-round victory occurred amid relatively low voter turnout (44.7%) during an

electoral process observed by the Organization of American States (OAS) and deemed free and

fair.14 The scale of Bukele’s victory demonstrated voters’ dissatisfaction with both major parties.

Bukele led the presidential race from start to finish, despite releasing few specific policy

proposals until late in the campaign and opting not to attend debates. In 2017, the FMLN expel ed

8 “T raducing El Salvador’s T ruce,” The Economist, August 26, 2017. 9 Nelson Renteria, “El Salvador’s top Court Approves Extradition Request for ex-President Funes,” Reuters, March 21, 2019. In October 2018, the attorney general’s office issued another arrest warrant for Funes on charges of involvement in a massive corruption scheme involving contractors, his family, and the former attorney general .

10 According to the State Department, investors “ generally perceived [the Sánchez Cerén government] as unsuccessful at improving the investment climate.” U.S. Department of State, 2019 Investment Clim ate Statem ents: El Salvador, July 11, 2019.

11 Anna-Catherine Brigida, “El Salvador’s T ough Policing Isn’t What it Looks Like,” Foreign Policy, July 6, 2019. 12 Douglas Farah and Caitlyn Yates, Maduro’s Last Stand, National Defense University and IBI Consultants, May 2019; Per U.S. T reasury Department guidance, sanctions on Venezuela’s stat e oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.(PdVSA), announced in January 2019 also apply to any subsidiaries in which the company (PdVSA) has a 50% or greater interest. See https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Documents/licensing_guidance.pdf. Héctor Silva Ávalos, “ PDVSA Subsidiaries in Central America Slapped With Sanctions,” InSight Crime, March 13, 2019. 13 T he White House, “Statement by t he Press Secretary on El Salvador,” August 23, 2018. 14 Organization of American States (OAS), “OAS Electoral Observation Mission Celebrates Peaceful Election in El Salvador,” February 4, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

3

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Bukele Administration

Born in San Salvador in 1981, Nayib Bukele is the son of the late Armando Bukele Kattán, a prominent businessperson of Palestinian descent who backed the FMLN financially beginning in the early 1990s. Bukele graduated high school in the late 1990s and began working in family businesses started by his father, including a public relations firm that represented the FMLN. Bukele was elected mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán (2012-2015) and San Salvador (2015-2018) for the FMLN. As mayor, he revitalized the historic center of San Salvador and engaged at-risk youth in violence-prevention programs. |

On February 3, 2019, Nayib Bukele, standing for the GANA party, won 53% of the vote, well ahead of Carlos Calleja, a business executive running for an ARENA-led coalition, with 31.8%, and Hugo Mártinez, a former foreign minister of the FMLN, with 14.4%. Bukele's first-round victory occurred amid relatively low voter turnout (44.7%) during a peaceful electoral process observed by the Organization of American States and deemed free and fair.16 The scale of Bukele's victory demonstrated voters' dissatisfaction with both major parties.

Bukele led the presidential race from start to finish, despite releasing few specific policy proposals until late in the campaign and opting not to attend debates. In 2017, the FMLN expelled Bukele from the party for criticizing its leadership. Bukele tried to create his own political party, but El Salvador'’s electoral court did not approve the new party'’s registration in time to appear on the ballot

the bal ot for the 2019 election. He then became GANA'’s presidential candidate.

As a candidate, Bukele communicated directly with potential voters using social media rather than relying on a party apparatus. He focused on addressing voters'’ concerns about corruption, unemployment, and crime. Bukele pledged to use his experience as a businessman and as a mayor

to attract investment, address the underlying causes of the gang phenomenon, and give Salvadorans hope so that they could envision a future in their country rather than emigratingunauthorized emigration would decline. Despite GANA'’s reputation for corruption, Bukele ran on an anticorruption campaign and calledcal ed for the establishment of an international international anticorruption commission in El Salvador similar to the U.N.-sponsored International Commission Against

Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG).15 His

Nayib Bukele

opposition to efforts by the National

Born in San Salvador in 1981, Nayib Bukele is the son of the

Assembly to shield civil conflict-era

late Armando Bukele Kattán, a prominent businessperson of

human rights abusers from prosecution

Palestinian descent who backed the FMLN financial y

won domestic and international praise

beginning in the early 1990s. Bukele graduated high school in

from human rights groups.16

the late 1990s and began working in family businesses started by his father, including a public relations firm that represented

Upon taking office, Bukele appointed a

the FMLN. Bukele was elected mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán

cabinet composed of individuals from a

(2012-2015) and San Salvador (2015-2018) for the FMLN. As

variety of parties. Vice President Felix

mayor, he revitalized the historic center of San Salvador and engaged at-risk youth in violence-prevention programs.

Ul oa isImpunity in Guatemala (CICIG).17 His opposition to efforts by the National Assembly to shield civil conflict-era human rights abusers from prosecution won praise from some domestic and international civil society groups.18

Upon taking office, Bukele appointed a cabinet composed of individuals from a variety of parties that is equally balanced by gender. Vice President Felix Ulloa, a lawyer who has worked with many international institutions on rule-of-law and election issues, has taken the lead on international issues, including efforts to implement an international anticorruption commission.19. Foreign Minister Alexandra Hill Hil formerly worked at the Organization of American StatesOAS. Bukele appointed a navy captain as defense minister and promoted six colonels to run the army while

pushing several army generals into retirement.2017 Bukele'’s minister of justice and security is a close political ally, andal y; his police chief is a career officer who most recently oversaw specialized units, including one implicated in extrajudicial killings kil ings of gang suspects.21 He18 Bukele kept the same finance minister as the previous government and selectedand chose an economy minister who used to work with the Inter-American Development Bank. Analysts predict these selections signal continuity for investors and a desire to seek support from multilateral institutions.22

Since taking office, Other ministers (agricultural and head of the ports) are lifelong friends of Bukele who reportedly

lack experience.19 Critics maintain Bukele has largely relied on his brothers for advice.20

President Bukele has governed much as he campaigned, including using social media to make policy declarations and to pressure legislators to back his policy proposals. Although he has outlined and secured some legislative support for his security plans, he has yet to present his economic proposals.23 Bukele is seeking private investment to fund many infrastructure projects, including a new airport and railway line, included in his national development plan, Plan Cuscatlán.24 He is also seeking support from the Organization of American States and the United Nations to fulfill his pledge to create a commission against corruption despite skepticism from the private sector about what it sees as "international interventionism without control or supervision."25

Bukele also purged the government of employees related to former FMLN presidents and accused senior members of that party of paying gangs to carry out attacks on police, an assertion the party has strongly denied.26 Bukele's supporters have praised these aggressive moves, many of which have been announced over social media. Critics fear that Bukele appears to have some authoritarian tendencies and have expressed concerns about statements he has made against journalists critical of his policies.27 Still others predict that Bukele may struggle to finance his initiatives to increase security, infrastructure, and education spending unless he is able to broker agreements with ARENA, which has 37 seats in the National Assembly.28

President Bukele has shifted El Salvador'declarations, purge government officials, attack his opponents, and pressure legislators to back his

policies.21 Bukele’s supporters have praised these moves, viewing them as needed steps to remove corruption and nepotism. Critics have expressed concerns about statements he has made and actions he has taken to discredit and block access to journalists and human rights groups

15 Melissa Vida, “Why T ackling Corruption Could Also Reduce Violence in El Salvador,” World Politics Review, June 19, 2019; Charles T . Call, International Anti-Im punity Missions in Guatem ala and Honduras: What Lessons for El Salavdor? American University, June 2019. 16 Due Process of Law Foundation, Three Years After the Annulment of the Amnesty Law, July 8, 2019. 17 “El Salvador: Changing of the Guard,” Latin America Weekly Report, June 20, 2019. 18 Héctor Silva Ávalos, “El Salvador Flirts with ‘Mano Dura’ Security Policies Again,” Insight Crime, June 21, 2019. 19 “Hungry House: Nayib Bukele’s Power Grab in El Salvador,” The Economist, May 6, 2020. 20 Ibid. 21 Patrick J. McDonnell, Alexander Renderos, “ Is El Salvador’s Millennial President a Reformer or an Autocrat?” Los Angeles Tim es, February 28, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 10 El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

critical of his actions.22 His use of the military to intimidate the legislature in February 2020 and to detain reported violators of a strict COVID-19 quarantine have prompted rebukes by El Salvador’s Supreme Court and international condemnation.23 Although Bukele may struggle to secure legislative support for his security plan and infrastructure proposals (discussed below) this year, some predict his popularity (92.5% in May 2020) wil help GANA pick up seats in the

February 2021 legislative elections.24

President Bukele has shifted El Salvador’s foreign policy into closer alignment with the United States and asked the United States for "“investments and great relations"” rather than just foreign assistance.29

assistance.25 He has criticized repression in Venezuela and Nicaragua, a significant departure from the prior government'’s position, while also condemning the erosion of democracy in Honduras. Bukele took responsibility for the June 2019 deaths of two Salvadoran migrants who drowned while trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border rather than criticizing U.S. immigration policies.30

During the campaign he had pledged to reassess the Sánchez Cerén government's August 201826 Bukele’s decision to abandon relations with Taiwan in favor of China. He recently announced, however, that for now, El Salvador's relations with China are "confirmed and fully established."31

maintain relations with China established by his predecessor was likely

driven by a need for foreign investment, but it remains a concern for U.S. policymakers.27

Security Conditions Security Conditions

El Salvador has been dealing with escalating homicides and generalized crime committed by gangs, drug traffickers, and other criminal groups for more than a decadetwo decades. In 2015, El Salvador posted a homicide rate of 104 per 100,000 people—the highest in the world. Although the homicide rate has decreased by almost 5065% since then to 5036 per 100,000, it remains high by global

standards (seesee Figure 2).3228 In contrast to other Central Americanneighboring countries, El Salvador'’s municipalities with

high levels of violence have varied significantly over time and are located all al over the country.29

22 Committee to Protect Journalists, “El Salvador Bans 2 Investigative Outlets from Press Conferences at Presidential Residence,” September 11, 2019; U.S. Department of State, Memorandum of Justification Regarding Ce rtification Under Section 7045 (a) of the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2020 (Div. G, P.L. 116-94), May 18, 2020. Hereinafter: U.S. Department of State, May 18, 2020.

23 U.S. Department of State, May 18, 2020. 24 Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Country Report: El Salvador, generated June 23, 2020; Edwin Segura, “Bukele Cierre su Primer Año con Alta Aprobación,” La Prensa Gráfica, May 20, 2020. 25 Nayib Bukele, “Nayib Bukele: El Salvador Doesn’t Want to Lose More People to the U.S.,” Washington Post, July 23, 2019.

26 Kirk Semple, “‘It Is Our Fault’: El Salvador’s President T akes Blame for Migrant Deaths in Rio Grande,’ New York Tim es, July 1, 2019. 27 Ernesto Londoño, “To Influence El Salvador, China Dangled Money. T he U.S. Made T hreats.” New York Times, September 21, 2019.

28 U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), over the country.33

In recent years, those homicides have included targeted killingskil ings of security forces by gangs, extrajudicial killings kil ings of gang suspects by police, and among the world'’s highest rates of femicide (killing (kil ing of a woman or girl, often committed by a man, because of her gender).34 In addition to the more than 3,300 homicides committed in 2018, the attorney general's office received more than 3,000 reports of disappeared persons from January through October 2018. Many of the disappeared are never found but are suspected dead.35

30 The 2018 kil ing of a prominent journalist, Karla Turcios, by her partner prompted the declaration of a national

emergency and captured international attention.31 In recent years, deportees have become targets

of violence, with at least 70 deportees murdered between 2013 and 2018.32

El Salvador has the highest concentration of gang members per capita in Central America. As a result, gangs arehave been responsible for a higher percentage of homicides there than in neighboring countries.33 Although President Bukele has attributed declining homicides to his military-led security policies, some analysts posit that gangs have deliberately decided to reduce violence in the territories they control to facilitate extortion and drug distribution (their primary sources of revenue).34 Gangs general y have not had a major role in transnational drug

trafficking.35 They have carried out periodic violence to demonstrate their power to the government, including attacks in April 2020 that resulted in more than 60 deaths in four days.36 Some fear that Bukele’s response to that violence, which included authorizing the use of lethal

30 International Crisis Group, El Salvador’s Politics of Perpetual Violence, Report No. 64, December 2017; Anna-Catherine Brigida, “El Salvador’s T ough Policing Isn’t What it Looks Like,” Foreign Policy, July 6, 2019. 31 Anastasia Moloney, “High-Profile El Salvador Femicide Case Exposes Deadly Gender Violence,” Reuters, January 21, 2020.

32 Anna-Catherine Brigida, “Kicked Out of the U.S., Salvadoran Deportees Are Struggling Simply to Stay Alive,” World Politics Review, Oct ober 9, 2018.

33 International Crisis Group, Life Under Gang Rule in El Salvador, November 26, 2018. 34 Asmann and O’Reilly, January 2020; T he Global Initiative Against T ransnational Organized Crime/InSight Crime, A Crim inal Culture: Extortion in Central Am erica, May 2019.

35 Steve Dudley and Héctor Silva, “ MS13 in the Americas: How the World’s Most Notorious Gang Defies Logic, Resists Destruction,” InSight Crim e and the Center for Latin American & Latino Studies at American University, February 2018.

36 Marcos Alemán, “ El Salvador’s Jail Crackdown on Gang Members Could Backfire,” AP, April 29, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

6

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

force against gangs and pushing gang inmates into crowded prisons with rival gangs, may prompt

more gang clashes with security forces and hurt the country’s international image.37

neighboring countries.36 A government-facilitated truce between the country's major gangs (the MS-13 or Mara Salvatrucha and the 18th Street gang) that unraveled in 2014 may have strengthened the gangs' internal cohesion.37 Gangs have been involved in a range of other criminal activities, including extortion, with individuals and businesses paying an amount equivalent to 1.7% of the country's gross domestic product (GDP) annually in extortion fees.38 Although gangs engage in local drug distribution, they generally do not have a major role in transnational drug trafficking or human smuggling.39 Deportees have become targets for extortion and violence, with at least 70 deportees murdered between 2013 and 2018.40

Where Did the Gangs in El Salvador Originate?

For additional information, |

Finklea.

Gang-related violence has fueled most internal displacement in El Salvador, but violence perpetrated by security forces (police and military) also has been a factor.38 In 2019internal displacement and irregular emigration. In August 2016, El Salvador's civil roundtable against forced displacement attributed more than 85% of internal displacement to gang activity. In 2018, El Salvador recorded 246,000 newly internally displaced persons454,000 new internal y displaced persons (IDPs) due to conflict, the most of any country in Latin America that experienced displacement linked to conflict and violence.39 In January 2020, the Bukele government enacted a law to deal with internal displacement that was praised by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other humanitarian organizations, but then

the government reportedly cut the 2020 budget for assistance to victims of violence.40

in Latin America that experienced displacement linked to conflict and violence.41 The government recently has acknowledged the phenomenon but struggled to address the needs of those fleeing violence. A 2018 study found that the probability that an individual intends to migrate is 10-15 percentage points higher for Salvadorans who have been victims of multiple crimes than for those who have not.42 (For more information on gang-related human rights abuses, as well as extrajudicial killings of gang suspects by security forces, see "Recent Human Rights Violations" section, below.)

Drug-trafficking organizations, including Mexican groups such as the Sinaloa criminal organization, have increased their illicit activities in El Salvador, albeit to a lesser extent than in Honduras and Guatemala.

Criminal Justice System

Criminal Justice System El Salvador has a long history of weak institutions and corruption, with successive presidents and legislatures allocatingal ocating insufficient funding to criminal justice institutions. With a majority of the national civilian policeNational Civilian Police (PNC) budget devoted to salaries, historicallyhistorical y there has been limited funding available for investing in training and equipment. The PNC has deficient wages, training, and infrastructure. It also has lacked a merit-based promotion system. Corruption, weak investigatory capacity, and an inability to prosecute officers accused of corruption and human rights abuses have hindered performance. A lack of confidence in the police has led many companies and

citizens to use private security firms and the government to deploy soldiers to perform public

37 Mary Beth Sheridan and Anna-Catherine Brigida, “Photos Show El Salvador’s Crackdown on Imprisoned Gang Members,” Washington Post, April 28, 2020. 38 Cristosal, Signs of a Crisis: Forced Internal Displacement as a Result of Violence in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, 2018, June 12, 2019.

39 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Global Report on Internal Displacement 2019, available at https://www.internal-displacement.org/database/displacement -data.

40 UNHCR, “UNHCR Welcomes new law in El Salvador to Help People Internally Displaced by Violence,” January 10, 2020; CRS interview with Cristosal, May 19, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

7

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

security functions. President Bukele has increased police salaries and sought, but did not receive,

legislative approval of a loan to provide new equipment for police and soldiers.41

The State Department maintained in 2019 that “impunity persisted despite government steps to

dismiss and prosecute” some officials who had committed abuses, partial y due to corruption in the judiciary.42 Whereas some judges and courts in El Salvador have issued significant decisions, particularly in opening civil-war era cases of human rights abuses, others have proven subject to corruption. From January to August 2019, the Supreme Court heard cases against 110 judges accused of various irregularities, including collusion with criminal groups.43 At President

Bukele’s direction, auditors have been examining the “reserved spending account” that Bukele’s

predecessors used to divert public funds for their own priorities.44

Observers praised the probity section of the Supreme Court’s efforts to identify public officials

who may have used their positions for il icit enrichment and the anti-corruption work of prosecutors under former Attorney General Douglas Meléndez (2016-2018).45citizens to use private security firms and the government to deploy soldiers to perform public security functions. President Bukele hopes to increase police salaries; he has redirected some funds to purchase new uniforms for the PNC and to support police (and military forces) carrying out his security strategy (see "Bukele's Security Plan," below).43

The State Department maintains that in 2018 "impunity persisted despite government steps to dismiss and prosecute" some officials who had committed abuses, partially due to "inefficiency and corruption" in the judiciary.44 As police and prosecutors often do not work well together to build cases, fewer than 10% of homicides have been prosecuted in recent years and fewer than 2% have resulted in a prison sentence.45 Despite these challenges, observers have praised the probity section of the Supreme Court's efforts to identify public officials who may have used their positions for illicit enrichment and the work of the attorney general's office.46 After a referral from the probity section, the Supreme Court voted in July 2019 to refer a case involving alleged illicit enrichment by Sigfrido Reyes, former president of the National Assembly, to civil court.47

Until the tenure of Attorney General Douglas Meléndez (2016-2018), a lack of political will and capacity to address corruption had fostered the embezzlement of state funds and corruption in public contracts. Under Meléndez, Salvadoran prosecutors, with U.S. support, brought corruption cases against the past three Salvadoran presidents and a former attorney general Luis Mártinez.48. Together, those presidents are estimated to have stolen

more than $750 mil ion.46 Meléndez faced death threats throughout his term.

Anti-corruption cases have continued, albeit slowly, under Attorney General Raul Melara, a lawyer unanimously selected by the National Assembly in December 2018 to replace Meléndez (who could have served a second term). Melara is a lawyer with ties to ARENA more than $750 million. After some early setbacks,49 the attorney general's office convicted police officers for aggravated homicides and for participating in a death squad, former president Saca for corruption, and a key gang truce mediator for extortion in 2018. Meléndez also issued new arrest warrants against former president Funes, former attorney general Mártinez, businessperson Enrique Raíz, and others for alleged involvement in a massive corruption scheme.50 Meléndez faced death threats throughout his term.

In December 2018, the National Assembly unanimously voted to replace Douglas Meléndez (who could have served a second term) with Raul Melara, a lawyer with ties to ARENA who had no who had no

experience in criminal prosecution. Under Melara, prosecutors have raided the offices of Alba Petróleos, a subsidiary of Venezuela'’s state oil company that is facing U.S. sanctions.51 In recent interviews, Melara has suggested that resolving cases involving forced disappearances will be one of his priorities and stated that although his office is open to receiving international assistance, prosecutors will continue their work with or without an international commission.52 He and President Bukele continue to seek Funes's extradition even though he has become a Nicaraguan citizen.53 Nevertheless, some are concerned that Melara's deputy attorney general has been accused of corruption by witnesses in the case against former attorney general Mártinez.54

While some judges and courts in El Salvador have issued significant decisions, particularly in opening civil-war era cases of human rights abuses, others have proven to be subject to corruption. From January to August 2018, the Supreme Court heard cases against 57 judges accused of various irregularities, including collusion with criminal groups.55 In November 2018, after months of wrangling, legislators agreed on replacements for five Supreme Court justices whose nine-year terms ended on July 15, 2018. Those justices replaced four of the five judges on the constitutional chamber, a body that has issued several significant decisions. Although some of the constitutional chamber's decisions have been controversial, others, including its 2016 decision to overturn the country's 1993 Amnesty Law, received international praise.

Delays in the judicial process and massive arrests carried out during past antigang sweeps made facing U.S. sanctions in May 2019, but have yet to indict anyone from the company or anyone who received funds from it (a group that includes Bukele).47 Melara appears to have acquiesced to President Bukele’s limited vision for the International Commission Against Impunity in El Salvador (CICIES), a campaign promise

Bukele fulfil ed through an agreement with the OAS in September 2019.48 Thus far, CICIES has a very limited staff and budget, and its mandate has been limited to providing technical support to Salvadoran prosecutors. Civic organizations have complained that CICIES is not empowered, as CICIG in Guatemala was, to initiate investigations and prosecutions or push for legislative reforms.49 The attorney general’s office also has announced it wil investigate COVID-19

spending for irregularities.50

41 “El Salvador Standoff Deepens over Loan for Security Forces,” AP, February 9, 2020. 42 U.S. Department of State, Country Report on Human Rights Practice for 2019: El Salvador, March 2020. Hereinafter: U.S. Department of State, Hum an Rights, 2020.

43 U.S. Department of State, Human Rights, 2020. 44 U.S. Department of State, May 18, 2020. 45 Several high-profile cases prepared by the probidity section had yet to be approved to move forward by the Supreme Court. T hose included former FMLN and GANA legislators, as well as former Vice President Oscar Ortiz. U.S. Department of State, Hum an Rights, 2020.

46 Felipe Puerta, “El Salvador AG’s Office Escalates Efforts Against Corruption,” InSight Crime, October 17, 2018. 47 Héctor Silva Ávalos, “El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele T ainted by Money Laundering Allegations,” InSight Crime, September 24, 2019. CRS interview with Héctor Silva, June 19, 2020. 48 Due Process of Law Foundation, From Hope to Skepticism: The International Commission Against Impunity in El Salvador (CICIES), April 1, 2020.

49 Paola Nagovitch, “Nayib Bukele’s First Year in Office,” Americas Society/Council of the Americas, May 28, 2020. 50 “Fiscalía Investigará Compras y Contrataciones en Emergencia,” La Prensa Gráfica, June 28, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

Delays in the judicial process and massive arrests carried out during anti-gang sweeps made under mano dura (heavy-handed)under mano dura (heavy-handed)56 policing efforts have resulted in severe prison overcrowding. 51 According to the U.S. State Department, prison capacity has increased in recent years, but facilities remained 215% overcrowded as of August 2018.57at 141% of occupancy as of September 2019.52 In addition to building new facilities, the government has channeled more prisoners into rehabilitation and job training programs, some of which have received U.S. support. Nevertheless, many human rights groups

maintain that sanitation and access to medical services have worsened since the government adopted more restrictive

prison conditions for gang inmates began in 2016.

Bukele’s Security Plan In June 2019, President Bukele launched the first phase (Preparation) of what he said would be a seven-phase Territorial Control plan. A year later, he has publicly announced only three of those seven phases, and the enforcement of a strict national quarantine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has dominated government efforts and public attention.53 The Bukele government

disbanded the council that the prior government used to discuss security issues with civil society and the private sector, but its security plan otherwise appears to resemble the focused, municipal-

level efforts of the prior FMLN government’s Safe El Salvador Plan.54

The first phase of the plan involved deploying police and military forces into 17 high-crime communities and on public transportation and declaring a state of emergency in 28 prisons. The state of emergency tightened the “extraordinary measures” already implemented in the prisons to include preventing visitors, blocking communications networks in and around prisons, and transferring inmates to more secure facilities.55 The Inter-American Commission of Human

Rights has raised concerns about the measures’ impact on inmates’ rights and health.56

President Bukele received legislative approval of a $90 mil ion loan to implement the second

phase of his security plan, Opportunity. This phase has sought to unite the efforts of government agencies, nonprofits, and donors to provide opportunities for youth to work, study, and engage in cultural and sports activities as alternatives to gangs. It also includes programs aimed at reinserting youth who are former inmates into society through their participation in penitentiary

farms or public works projects.

For years, Salvadoran presidents have deployed thousands of military troops to support the police, but observers have been particularly concerned about President Bukele’s use of the military. Bukele has tasked thousands of members of the armed forces with supporting his 51 Mano dura approaches have involved incarcerating large numbers of youth (often with tattoos) for illicit association and increasing sentences for gang membership and gang-related crimes. A m ano dura law passed by El Salvador’s Congress in 2003 was subsequently declared unconstitutional but was followed by a super m ano dura package of reforms in July 2004. T hese reforms enhanced police power to search an d arrest suspected gang members and stiffened penalties for convicted gang members, although they provided some protections for minors. For background, see Sonja Wolf, Mano Dura: the Politics of Gang Control in El Salvador (Austin, T X: University of T exas Press, 2017).

52 U.S. Department of State, Human Rights, 2020. 53 Paola Nagovitch, “Explainer: Nayib Bukele’s T erritorial Control Plan,” Americas Quarterly, February 13, 2020. 54 Roberto Valencia, “La Fase 2 del Plan Control T erritorial es Parecida a lo que Planteaba el Plan El Salvador Seguro,” El Faro, November 1, 2019.

55 “Extraordinary measures,” which began as a temporary measure in 2016 but became permanent through legislation passed in 2018 enable the movement of gang leaders to maximum -security prisons, cutting off cell phone service around prisons and restricting visitors to those facilities.

56 Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), “IACHR Presents its Preliminary Observations Following its in loco Visit to El Salvador,” press release No. 335/19, December 27, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

9

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

security plan. In August 2019, Bukele announced phase three (Modernization) of his plan, which has not yet been implemented. In February 2020, the National Assembly refused to approve a $109 mil ion loan to equip the police and military, even after Bukele had those forces surround the legislative palace—a move the Supreme Court and international observers rebuked.57 Bukele has also defied a Supreme Court order to stop using security forces to detain those accused of

violating a national quarantine and force them to stay in “containment centers.”58

in 2016.

Secure El Salvador Plan; "Extraordinary Measures" in Prisons

With support from the U.S. government and the United Nations, the Sánchez Cerén government formed a National Council for Citizen Security, which designed an integrated security strategy known as Secure El Salvador (El Salvador Seguro).58 The implementation plan for the strategy, known as Plan Secure El Salvador (PESS), was applied in 50 of the country's most violent municipalities and coordinated with U.S. crime prevention and community policing efforts. According to figures from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), municipalities in which PESS and USAID programs operated saw a 61% reduction in homicides from 2015 to 2017 as compared to the 42% reduction in homicides recorded in other municipalities.59 Critics have questioned why PESS bolstered security forces that continued to commit abuses and suggested that the homicide reductions recorded may have been due to other factors, such as gangs achieving territorial control over some areas.60

In April 2016, the Sánchez Cerén government started implementing "extraordinary measures" focused on moving gang leaders to maximum-security prisons, cutting off cell phone service around prisons and restricting visitors to those facilities. In August 2018, the National Assembly made permanent the "extraordinary measures," which they had previously had authorized temporarily. Salvadoran officials and legislators maintain that the measures have helped reduce communications between inmates and the outside, including incidents of murders ordered from imprisoned gang leaders.61 However, U.N. officials and human rights groups have raised concerns about the measures' impact on inmates' rights and health.62

Bukele's Security Plan

On June 20, 2019, President Bukele launched the first phase of what he has said will be a seven-phase security plan, with $31 million reassigned from other budgetary priorities by the National Assembly. The first phase of the plan has involved deploying police and military forces into 17 high-crime communities and on public transportation and declaring a state of emergency in the 28 prisons in the country. The state of emergency tightens the extraordinary measures already implemented in the prisons to include preventing all visitors, blocking communications networks in and around prisons, and transferring inmates to more secure facilities. As of July 12, 2019, the plan, which resembles the mano dura strategies that prior governments have implemented since 2003, had resulted in more than 4,600 arrests of reported "gang leaders and criminals."63

President Bukele has requested, but not yet received, $90 million to implement the second phase of his security plan. If funded, that phase intends to unite the efforts of many government agencies, nonprofits, and international donors to provide opportunities for youth to work, study, and engage in cultural and sports activities as alternatives to gangs. It also includes programs aimed at reinserting youth who are former inmates through participation in penitentiary farms or public works projects. In addition, Bukele has emphasized the plan's focus on targeting the financing of the gangs, including "extortion and money laundering networks."64

Military Involvement in Public Security Efforts

For many years, El Salvador has deployed thousands of military troops to support the police. In April 2014, the Salvadoran Supreme Court upheld former president Funes's 2009 decree that authorized the military to carry out police functions. Three battalions each made up of 200 police and elite members of the armed forces were deployed in 2015 to control gang violence. In April 2016, Sánchez Cerén deployed the El Salvador Special Reaction Force, a 1,000-member force made up of 400 police and 600 soldiers, into rural areas to which gang members had fled. In November 2016, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala launched a trinational antigang force, comprised of military and police officers, to target gangs on the borders. According to U.S. estimates, roughly 8,000 of El Salvador's 17,000 active-duty armed forces personnel are involved in public security at any given time.65 President Bukele has similarly tasked roughly 7,000 members of the armed forces with supporting his security plan.

Economic and Social Conditions

Although El Salvador facesEconomic and Social Conditions El Salvador has faced significant economic challenges, the country has made some progress in recent years at tackling weaknesses in its economy that may be exacerbated by the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (see the text box “COVID-19 in El Salvador”). According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), El Salvador posted an economic growth rate of 2.5% in 20182019. The IMF predictsinitial y predicted similar growth of about 2.5% this year but later revised its

forecast to a contraction of 5.4%, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.59

similar growth of about 2.5% this year.66 Record remittances, which were equivalent to 21% of GDP in 2018, low oil prices, and a growing U.S. economy have helped El Salvador's economic performance.67 Nevertheless, natural disasters, including flooding in 2017 and a drought in 2018, have hindered agricultural output.

Economists have identified a lack of public and private investment in the economy as a primary reason for El Salvador'’s moderate growth rates. According to El Salvador'’s Central Bank, net inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) stood at $849 millionmil ion in 2018, with a total stock of

$9.7 bil ion$9.7 billion. Experts maintain El Salvador needs to attract more than $1.2 billion annuallybil ion annual y in order to bolster growth.6860 Despite El Salvador'’s relatively low inflation and stable, dollarized economy, FDI in El Salvador has been lower than the average among Central American countries for several years. Low levels of FDI have been attributed to the country'’s political polarization,

complicated regulations and bureaucracy, security challenges (including violence and extortion), and ineffective justice system (discussed in "Criminal Justice System," above).69

Until 2017, El Salvador'chal enges, and ineffective justice system.61

El Salvador’s executive and legislature have often clashed over how to respond to the country's ’s social and infrastructure needs and significant financing gaps. The government has often swapped short-term debt for longer-term debt rather than implement unpopular fiscal reforms. The

legislature has been reluctant to approve multilateral financing requests from the executive branchbranch for social programs. In addition, long-standing government practices that preceded but continued under FMLN rule—including cash payments to officials,

and a shielded presidential spending account, and diversion of government funds——have exacerbated fiscal woes.

Since 2017, the IMF has credited the Salvadoran government with taking steps to improve the country'country’s fiscal situation and implementing "progrowth reforms."70“pro-growth reforms.”62 A 2017 pension reform helped ease the financial burden on that system by raising both employee and employer contributionscontributions; the IMF urges a complementary reform to raise the retirement age and better target benefits. The IMF also credits a fiscal responsibility law with helping rationalize public spending and reduce the country's public debt. Now that Bukele has taken public spending. After President Bukele took office, IMF officials are urgingurged him to secureback a broader fiscal

pact that could include excise taxes on luxury goods, better targeted social programs, a property tax, and/or a reduction in the size of some public sector agencies.71

In its most recent Ease of Doing Business reports, the World Bank has agencies.63 As part of a COVID-related emergency

57 WOLA, Political Crisis in El Salvador Should be Solved Through Dialogue, Not Through Power Plays and Military Deploym ents, February 10, 2020. 58 Marcos Aleman and Christopher Sherman, “El Salvador Quarantine Centers Become Points of Contagion,” AP, May 17, 2020.

59 IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019; World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020. 60 United Nations, 2019 World Investment Report. “El Salvador: Bukele’s Economic Challenge,” Latin News Caribbean & Central Am erica report, June 2019. 61 U.S. Department of State, Investment Climate Report for 2019. July 11, 2019. 62 IMF, El Salvador: 2018 Article IV Consultation, Country Report No. 18/151, June 2018. 63 IMF, El Salvador: Staff Report for the 2019 Article IV Consultation , May 7, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

10

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

program with the IMF (discussed below), the government has pledged to reduce its fiscal deficit

in 2021-2023, necessitating a balance of tax increases and austerity measures.64

In recent Ease of Doing Business reports, the World Bank has also credited El Salvador with

credited El Salvador with implementing reforms to ease the process for businesses to obtain permits for new construction and pay taxes online, to increase access to electricity, and to speed up border crossings. El Salvador moved up 22 spots to 73rd out of the Nevertheless, El Salvador fel from 73 of 190 countries ranked in 2018 to 85 in the 2019 report and 91 in the 2020 edition, as other countries reported more progress.65 The State Department has cited the country’s “190 countries ranked in 2018 before falling to 85th in the 2019 report (still the seventh-highest ranking received by a Latin American or Caribbean country).72 Nevertheless, the State Department cites the country's "discretionary application of laws/regulations, lengthy and unpredictable permitting procedures,

and customs delays," as continuing to hinder” as hindering the business environment.73 President Bukele has vowed to change that, arguing that an improved business climate should help him66 Upon taking office, President Bukele vowed to improve the business climate and create 100,000 jobs a year as compared to with the fewer than 10,000 a year created during the Sánchez Cerén governmentjobs created annual y during Sánchez Cerén’s term. Each year, the country needs

would need to create roughlysome 50,000 jobs just to keep up with the growing labor force.74

67

Insecurity and corruption are among the primary barriers to growth in El Salvador. A 2017 study by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) estimated the costs of crime and violence in El Salvador could reach 5.9% of GDP.7568 In the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report for 2019, El Salvador ranked last out of 140 countries evaluated in the World Economic Forum's 2018 estimates of business costs due to crime and violence.76 Crimes against small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which employ 55% of El Salvador'141 countries evaluated for estimates of business costs due to

organized crime and high homicide rates. Its overal ranking its overal ranking stood at 103rd.69 Crimes against smal - and medium-sized enterprises, which employ 55% of El Salvador’s labor

s labor force, are of particular concern. According to estimates by the National Council of Small Enterprises cited by the IMF, some 90% of SMEs were extorted in 2017.

According to a study by El Salvador'’s INCAE business school, corruption increases has increased transaction costs and reduces the efficiency and reduced the effectiveness of the state.7770 As an example, prosecutors recently in 2019, prosecutors charged former president Funes with paying a company over $100 millionmil ion for a hydroelectric plant that it never completed in a region where access to water is vital.7871 In addition to raising the costs of public works projects, corruption has limitedreduced resources available to respond to natural

disasters and other challengeschal enges. As previously mentioned, Presidentformer president Francisco Flores

(ARENA, 1999-2004) allegedlyal egedly embezzled donations destined for earthquake relief.

Although progress in developing infrastructure, facilitating trade, and easing some regulations has occurred, another barrier to growth in El Salvador continues to be a lack of competitiveness in export sectors. El Salvador's labor force lacks

A lack of competitiveness in export sectors has continued to restrict growth. El Salvador’s labor

force has lacked adequate education and vocational training to align with labor force needs, including English-language skills.79skil s.72 In addition, the country has had logistical and physical infrastructure deficiencies, including no direct access to Caribbean ports. El Salvador's small ’s smal size and high levels of informality (percentage of businesses that do not pay taxes, provide benefits to

employees, or register with the government) have also reduced its competitiveness.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, Bukele had received loans and foreign cooperation (including through the Mil ennium Chal enge Cooperation) to fund infrastructure projects. Selected 64 “El Salvador: Bukele Announces More Coronavirus Stimulus Measures,” May 19, 2020. 65 World Bank, Ease of Doing Business: Reforming to Create Jobs, 2018; Ease of Doing Business: T raining for Reform, 2019; Doing Business 2020, at https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings.

66 U.S. Department of State, Investment Climate Report, July 11, 2019. 67 “El Salvador: Bukele’s Economic Challenge,” Latin News Caribbean & Central America report, June 2019. 68 Laura Jaitman, The Costs of Crime and Violence: New Evidence and Insights in Latin America and the Caribbean , International Development Bank, 2017.

69 World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report, 2019. 70 INCAE, Corrupcion en América Latina y sus Soluciones Potenciales, February 20, 2019. 71 David Marroquín and Xiomara Alfaro, “Fiscalía Presenta Nuevos Cargos Contra Expresidente Funes por Desviar Fondos para presa El Chaparral y Divulgar Información confidencial,” El Salvador.com, January 4, 2019.

72 U.S. Department of State, Country Strategy: El Salvador, August 2018.

Congressional Research Service

11

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

initiatives included a new Pacific railway line, a doubling in the capacity of the Acajutla port, and an upgrade of the cargo terminal at the international airport.73 Bukele has supported public-private partnerships. He has sought international investment for those infrastructure projects, as wel as a tourism hub cal ed “Surf City.”74 During a state visit to China in December 2019, Bukele received pledges that China would support several infrastructure projects (including a new stadium and

water treatment plant), but details of those pledges were not publicly announced.75

Social development indicators in El Salvador have beenemployees, or register with the government) are widely considered key factors in its reduced competitiveness.

In 2018, El Salvador took several steps that could affect its economic trajectory. In November 2018, El Salvador joined an existing customs union with Guatemala and Honduras and launched a ferry to Costa Rica to bypass instability in Nicaragua. Both moves could bolster intraregional trade. El Salvador's decision to abandon relations with Taiwan and seek trade and investment from China could have long-term economic implications; it has already resulted in the announcement of $150 million in Chinese investment.80

Social development indicators in El Salvador generally are better than in neighboring Honduras and Guatemala, yet challengeschal enges exist, particularly in rural regions. Under successive FMLN

Administrations, poverty dropped from 50.1% in 2009 to 44.5% in 2014 to 26.3% in 2018; extreme poverty dropped from 17.1% to 11.7% to 5.7%.8176 Income inequality has also declined

due to growth in the income of the poorest 20% of the population aided by remittances.82

77

According to World Bank data, most social development indicators in El Salvador improved from 2010 to 2017, but some health and education indicators worsened.8378 The mortality rate for children under the age of five fell fel from 19 per 1,000 live births in 2010 to 15 per 1,000 in 2017. By 2017, skilledskil ed health professionals attended nearly all al births in El Salvador and the percentage of children underweight for their age fell fel to 5%. Despite this progress, immunization rates for

children under the age of two fell fel to 85% (from 92% in 2010) and primary school completion rates declined to 85% (from 92% in 2010). Per-capita spending on social programs is has been higher in El Salvador than in neighboring Guatemala and Honduras, but still much but lower than the regional average for Latin America.8479 Gang-related intimidation and insecurity and teen pregnancies have contributed to poor youth attendance in school.80 El Salvador has had the highest percentage of youth aged 15-24 who are

not employed, in school, or in vocational training (28.4%) in Central America.81

According to the 2019 World Risk Index, El Salvador has been among the 20 countries in the world most at risk from natural disasters, due to frequent exposure and weak response capacity.82

The Central American Dry Corridor, which encompasses 58% of El Salvador, 38% of Guatemala, and 21% of Honduras, is extremely susceptible to irregular rainfal . and teen pregnancies are two primary reasons why only about half of eligible Salvadoran youth attend 7th-9th grades; of these, only half complete secondary school.85 According to data from the International Labour Organization (ILO), El Salvador has the highest percentage of youth aged 15-24 who are not employed, in school, or in vocational training (28.4%) of any country in Central America.86

Food insecurity, often caused by drought or other natural disasters (such as earthquakes and hurricanes), has become a major social issue and driver of emigration from El Salvador.87 Although family members who are left behind eventually may benefit from 83 As an example, the World Food Program estimated that more than 330,000 Salvadorans are facing food insecurity due to the combined impact of Tropical Storm Amanda and COVID-19.84 Although some families may benefit from

73 “How Is El Salvador Advancing Its Infrastructure Projects?” Bnamericas, October 7, 2019. 74 María Eugenia Brizuela de Ávila and Domingo Sadurní, Nayib Bukele’s First Six Months, Atlantic Council, August 2019. T he lack of roads and sewage treatment facilities in the coastal region of El Salvador are barriers to tourism that the government aims to address. 75 “El Salvador to Get Major Chinese Infra Investments,” Bnamericas, December 4, 2019. 76 Data are available at U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, https://estadisticas.cepal.org/cepalstat/WEB_CEPALST AT /estadisticasIndicadores.asp?idioma=i

77 T he World Bank, “El Salvador: Overview,” updated April 4, 2019. 78 T he data are available at http://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=SLV.

79 Bartenstein and McDonald, op. cit. 80 USAID El Salvador, “Education Fact Sheet,” at https://www.usaid.gov/el-salvador/education. 81 Data are from the International Labour Organization (ILO), ILOSTAT, accessed in June 2019. 82 Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft and the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV), World Risk Index, 2019.

83 Nina Lakhani, “Living Without Water: the Crisis Pushing People out of El Salvador,” The Guardian, July 30, 2019. 84 World Food Program, “ T ropical Storm Amanda Severely Impacts Food Security of 340,000 Salvadorans,” June 9,

Congressional Research Service

12

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations

remittances sent by relatives living abroad, they are often saddled with debts owed to smugglers, an increased work burden (especiallyespecial y in agriculture), and emotional trauma.88 Additionally, 85 Additional y, households that receive remittances from relatives in the United States are often better able to deal with food insecurity and natural disasters, but observers maintain that they have been targets for

extortion by gangs and corrupt police.89

Human Rights

Violence and human rights abuses have been prevalent for much of El Salvador's modern history. Salvadoran authorities are just beginning to investigate mass atrocities committed during the civil war (1980-1992), however, since the Supreme Court did not overturn a 1993 amnesty law until July 2016.90 Prior to Bukele'86

COVID-19 in El Salvador