Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

Changes from June 4, 2019 to March 3, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- WTO Commitments May Influence Policy Choices

- Agreement on Agriculture (AoA)

- Domestic Support Categorization

- Domestic Support Notification

- Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM)

- WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU)

- Questions for Evaluating WTO Compliance of Domestic Farm Spending

- Question 1: Can This Measure Be Placed in the Green Box?

- Question 2: Can This Measure Be Placed in the Blue Box?

- Question 3: If Amber, Will Support Exceed 5% of Production Value?

- Question 4: Does Total Annual AMS Now Exceed $19.1 Billion?

- Question 5: Does Domestic Support Result in Significant Market Distortion in International Markets?

- Conclusion

Summary

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on

March 3, 2021

U.S. Domestic Support

Randy Schnepf

Omnibus U.S. farm legislation—referred to as the farm bill—has typically been renewed every

Specialist in Agricultural

five or six years. Farm revenue support programs have been a part of U.S. farm bills since the

Policy

1930s. Each successive farm bill usually involves some modification or replacement of existing

farm programs. A key question likely to be asked of every new farm proposal or program is how

it will affect U.S. commitments under the World Trade Organization'’s (WTO'’s) Agreement on

Agriculture (AoA) and its Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM).

The United States is currently committed, under the AoA, to spend no more than $19.1 billion annually on those domestic farm support programs most likely to distort trade—referred to as amber box programs and measured by the Aggregate Measure of Support (AMS). The AoA spells out the rules for countries to determine whether their policies—for any given year—are potentially trade distorting and how to calculate the costs.

The most recent U.S. notification to the WTO of domestic support outlays (made on October 31, 2018July 24, 2019) is for the 2016 crop 2017 marketing year. To date, the United States has never exceeded its $19.1 billion amber box spending limit. However, this has been achieved in some years (1999, 2000, and 2001) through judicious use of the de minimis exclusion described below.

An additional consideration for WTO compliance—the SCM rules governing adverse market effects resulting from a farm program—comes into play when a domestic farm policy effect spills over into international markets . The SCM details rules

for determining when a subsidy is "prohibited"“prohibited” (e.g., certain export- and import-substitution subsidies) and when it is "actionable"“actionable” (e.g., certain domestic support policies that incentivize overproduction and result in significant market distortion—whether as lower market prices or altered trade patterns). Because the United States is a major producer, consumer, exporter, and/or importer of most major agricultural commodities, the SCM is relevant for most major U.S. agricultural products. As a result, if a particular U.S. farm program is deemed to result in market distortion that adversely affects other WTO members —even if it is within agreed-upon AoA spending limits—then that program may be subject to challenge under the WTO dispute settlement procedures.

Designing farm programs that comply with WTO rules can avoid potential trade disputes. Based on AoA and SCM rules, U.S. domestic agricultural support can be evaluated against five specific successive questions to determine how it is classified under the WTO rules, whether total support is within WTO limits, and whether a specific program fully complies with WTO rules:

-

Can a program

'’s support outlays be excluded from the AMS total by being placed in the green box ofminimally distorting programs? -

minimally distorting programs?

Can a program

'’s support outlays be excluded from the AMS total by being placed in the blue box of production-limiting programs? -

If amber, will

- Does the total, remaining annual AMS exceed the $19.1 billion amber box limit?

- Even if a program is found to be fully compliant with the AoA rules and limits, does its support result in

price or trade distortion in international markets? If so, then it may be subject to challenge under SCM rules.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 11 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 15 Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 WTO Commitments May Influence Policy Choices.............................................................. 1

Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) ................................................................................. 2

Domestic Support Categorization............................................................................ 2 Domestic Support Notification ............................................................................... 3

Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM).......................................... 3 WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) ............................................................. 5

Questions for Evaluating WTO Compliance of Domestic Farm Spending ................................ 5

Question 1: Can This Measure Be Placed in the Green Box? ............................................ 6 Question 2: Can This Measure Be Placed in the Blue Box? .............................................. 8

Question 3: If Amber, Will Support Exceed 5% of Production Value? ................................ 9 Question 4: Does Total Annual AMS Now Exceed $19.1 Billion? ..................................... 9 Question 5: Does Domestic Support Result in Significant Market Distortion in

International Markets? ........................................................................................... 10

Conclusion................................................................................................................... 10

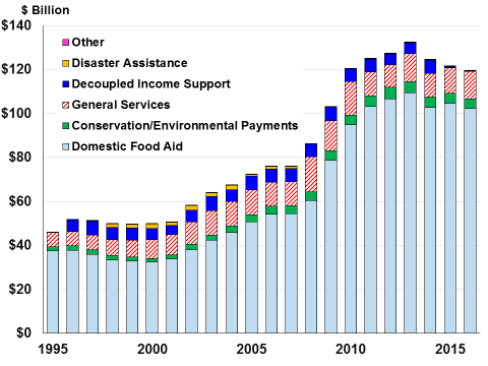

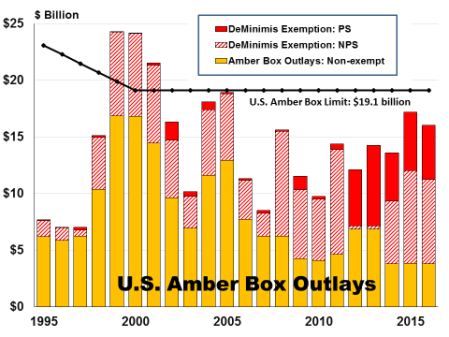

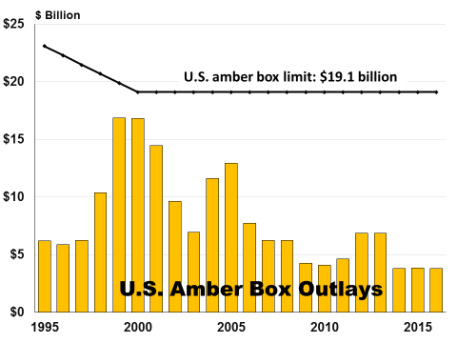

Figures Figure 1. U.S. Annual Green Box Notifications by Category .................................................. 8 Figure 2. U.S. Amber Box Outlays Subject to AMS Spending Limit ..................................... 11 Figure 3. U.S. Amber Box Outlays Including Exemptions ................................................... 11

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 12

Congressional Research Service

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

Introduction

rules.

Introduction

Trade plays a critical role in the U.S. agricultural sector. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that exports account for about 20% of total U.S. agricultural production.1 1 Furthermore, given the substantial volume of its agricultural exports, the United States plays a a significant role in many international agricultural markets. As a result, U.S. farm policy is often subject to intense scrutiny both for compliance with current World Trade Organization (WTO)

rules and for its potential to diminish the breadth or impede the success of future multilateral negotiations. In part, this is because a farm bill bil locks in U.S. policy behavior for an extended period of time during which the United States would be unable to accept any new restrictions on

its domestic support programs.

Farm revenue support programs have been a part of U.S. farm legislation since the 1930s. Today, these support programs are authorized as part of omnibus U.S. farm legislation—referred to as the farm billbil —which has typicallytypical y been renewed every five or six years. Each successive farm bill usuallybil usual y involves some modification or replacement of existing farm programs. The current

omnibus farm billbil , the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334; the 2018 farm billbil ), was signed into law on December 20, 2018.22 The 2018 farm bill bil largely maintains the farm safety net of the previous 2014 farm bill (bil (P.L. 113-79).3).3 The commodity programs of the 2018 farm bill bil became operational with the 2018 crop year. They are scheduled to expire on September 30, 2023, or with the 2023 crop year. Ultimately, the current farm bill will bil wil either be (1) replaced with

new legislation, (2) temporarily extended, or (3) allowedal owed to lapse and replaced with "“permanent law"law”—a set of essentially mothballedessential y mothbal ed provisions for the farm commodity programs that date from

the 1930s and 1940s.4

4 WTO Commitments May Influence Policy Choices

A potential major constraint affecting U.S. agricultural policy choices is the set of commitments made as part of membership in the WTO.55 The WTO has three basic functions: (1) administering

existing agreements, including those governing agriculture and trade;66 (2) serving as a negotiating forum for new trade liberalization; and (3) providing a mechanism to settle trade disputes among members.77 With respect to disciplines governing domestic agricultural support, two WTO agreements are paramount—the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA)88 and the Agreement on

Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM).9

9

1 USDA, Economic Research Service (ERS), U.S. Agricultural T rade, “U.S. Export Share of Production,” https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/international-markets-us-trade/us-agricultural-trade/.

2 See CRS Report R45730, Farm Commodity Provisions in the 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115 -334). 3 See CRS Report R43448, Farm Commodity Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113 -79). 4 For example, see CRS Report R42442, Expiration and Extension of the 2008 Farm Bill. 5 T he WT O is a global rules-based, member-driven organization dealing with the rules of trade between nations. As of March 7, 2019, the WT O included 164 members. See CRS In Focus IF10002, The World Trade Organization.

6 For a complete list of WT O agreements and their text, see WT O, The Legal Texts (Cambridge University Press and World T rade Organization, 1999), https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/legal_e.htm. 7 See CRS In Focus IF10645, Dispute Settlement in the WTO and U.S. Trade Agreements. 8 See CRS Report RL32916, Agriculture in the WTO: Policy Commitments Made Under the Agreement on Agriculture. 9 See CRS Report RS22522, Potential Challenges to U.S. Farm Subsidies in the WTO: A Brief Overview.

Congressional Research Service

1

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

The AoA sets country-specific aggregate spending limits on the most market-distorting policies. It also defines very general rules covering trade among member countries. In general, domestic policies or programs found to be in violation of WTO rules may be subject to challengechal enge by another WTO member under the WTO dispute settlement process. If a WTO challengechal enge is successful, the WTO remedy would likely imply the elimination, alteration, or amendment by Congress of the program in question to bring it into compliance. Since most governing provisions

over U.S. farm programs are statutory, new legislation could be required to implement even minor changes to achieve compliance.1010 As a result, designing farm programs that comply with

WTO rules can avoid potential trade disputes.

This report provides a brief overview of the WTO commitments that are most relevant for U.S. domestic farm policy. A key question that many policymakers ask of virtuallyvirtual y every new farm proposal is how it will wil affect U.S. commitments under the WTO. The answer depends not only on

cost but also on the proposal'’s design and objectives, as described below.

Agreement on Agriculture (AoA)

Under the AoA, WTO member countries agreed to general rules regarding disciplines on

domestic subsidies (as well wel as on export subsidies and market access). The AoA'’s goal was to provide a framework for the leading members of the WTO to make changes in their domestic

farm policies to facilitate more open trade.

Domestic Support Categorization

The WTO'’s AoA categorizes and restricts agricultural domestic support programs according to

their potential to distort commercial markets. Whenever a program payment influences a producer'producer’s behavior, it has the potential to distort markets (i.e., to alter the supply of a commodity) from the equilibrium that would otherwise exist in the absence of the program's ’s influence. Those outlays that have the greatest potential to distort agricultural markets—referred to as amber box subsidies—are subject to spending limits.1111 In contrast, more benign outlays (i.e., those that cause less or minimal market distortion) are exempted from spending limits under

green box, blue box, de minimis, or special and differential treatment exemptions.12

12

The AoA contains detailed rules and procedures to guide countries in determining how to classify

their programs in terms of which are most likely to distort production and trade; in calculating their annual cost, measured by the Aggregate Measure of Support (AMS) index;1313 and in reporting the total cost to the WTO. SpecificallySpecifical y, the WTO uses a traffic light analogy to group programs:

-

programs:

Green box programs are

minimallyminimal y or non-trade distorting and not subject to any spending limits. Blue10 For example, see CRS Report R43336, The WTO Brazil-U.S. Cotton Case. 11 T hese spending and subsidy commitments are detailed in each member’s country schedule. For more information, see CRS Report RL32916, Agriculture in the WTO: Policy Com m itm ents Made Under the Agreem ent on Agriculture . 12 WT O special and differential treatment exemptions are reserved for “develop ing” countries and are thus not relevant for evaluating U.S. domestic farm policy. 13 T he AoA, Part I, Article 1(a), defines AMS as the annual level of support, expressed in monetary terms, provided for an agricultural product in favor of the producers of t he basic agricultural product or non-product -specific support provided in favor of agricultural producers in general other than support provided under programs that qualify for exempt ion as described in the remainder of this report. Congressional Research Service 2 link to page 8 link to page 8 Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support Blue box programs are described as production-limiting. They have paymentsboxprograms are described as production-limiting. They have paymentsthat are based on either a fixed area or yield or a fixed number of livestock and are made on less than 85% of base production. As such, blue box programs are also not subject to any payment limits.-

Amber box programs are the most market-distorting programs and are subject to

a strict aggregate, annual spending limit. The United States is subject to a spending limit

billionbil ion in amber box outlays subject to certain de minimisexemptions.14 - exemptions.14

De minimis exemptions are domestic support spending that is sufficiently

smallsmal —relative to either the value of a specific product or total production—to be deemed benign. De minimis exemptions are limited by 5% of the value of production—either total or product-specific.15 - 15

Prohibited (i.e., red box) programs include certain types of export and import

subsidies and nontariff trade barriers that are not explicitly included in a

country'country’s WTO schedule or identified in the WTO legal texts.16

16

This report describes the AoA classifications in more detail below in the section titled "Questions “Questions

for Evaluating WTO Compliance of Domestic Farm Spending."

” Domestic Support Notification

To provide for monitoring and compliance of WTO policy commitments, each WTO member country is expected to routinely submit notification reports on the implementation of its various

commitments. The WTO'’s Committee on Agriculture has the duty of reviewing progress in the implementation of individual member commitments based on member notifications. Furthermore, the WTO posts the notifications on its official website for all al members to review.1717 The most recent U.S. notification to the WTO of domestic support outlays (made on October 31, 2018) is for the 2016 crop year.

July 24, 2020) is for the 2017 marketing year.18 Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM)

To the extent that domestic farm policy effects spill spil over into international markets, U.S. farm

programs are also subject to certain rules under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM).18 The SCM details rules for determining when a subsidy is "prohibited" (as in the case of certain export- and import-substitution subsidies) and when it is "actionable" (as in the 14 For developed member countries, the AMS was to be reduced from a 1986-1988 base period average by 20% in six equal annual installments during 1995-2000. For the United States, the initial 1986 -88 AMS base was $23.879 billion. T his was lowered to $19.103 billion by 2000, where it has been fixed ever since. 15 General domestic support (not specific to any one commodity, such as rural infrastructure or extension) that is below 5% of the value of total agricultural production is deemed sufficiently benign that it does not have to be included in the amber box. Similarly, support for a specific commodity (such as marketing assistance loan benefits, commodity storage payments, crop insurance premium subsidies, etc.) that is below 5% of that commodity’s value of production is deemed sufficiently benign that it does not have to be included in the amber box.

16 T he term red box is not actually used by the WT O but is included here to complete the traffic light analogy. 17 WT O, “WT O Documents Online,” https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S003.aspx. 18 A marketing year is the 12-month period that begins after a crop is harvested. It represents the 12 months prior to the next harvest, during which a harvested crop is either sold into domestic or international markets or kept on the farm to be used as feedstuffs or stored for future sale or use. Crops with different planting and harvesting schedules have different marketing years. For example, the marketing year for the U.S. wheat, barley, and oat crops starts on June 1; the marketing year for cotton and rice starts on August 1; and the marketing year for corn, soybeans, and sorghum starts on September 1. USDA, in notifying total program outlays for a marketing year, aggregates payment data from slightly different marketing-year periods across the different program crops.

Congressional Research Service

3

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

Measures (SCM).19 The SCM details rules for determining when a subsidy is “prohibited” (as in the case of certain export- and import-substitution subsidies) and when it is “actionable” (as in the case of certain domestic support policies that incentivize overproduction and result in significant

case of certain domestic support policies that incentivize overproduction and result in significant market distortion—whether as lower market prices or altered trade patterns).19

20

The key aspect of SCM commitments is the degree to which a domestic support program engenders market distortion. Based on precedent from past WTO decisions, several criteria are

important in establishing whether a subsidy could result in significant market distortions:

- The subsidy constitutes a substantial share of farmer returns or covers a substantial share of production costs.

- The subsidized commodity is important to world markets because it forms a large share of either world production or world trade.

-

A causal relationship exists between the subsidy and adverse effects in the

relevant market.

The SCM evaluates the "“market distortion"” of a program or policy in terms of its measurable

market effects on the international trade and/or market price for the affected commodity:

-

Did the subsidy displace or impede the import of a like product into the

subsidizing member

'’s domestic market? - Did the subsidy displace or impede the exports of a like product by another WTO member country other than the subsidizing member?

-

Did the subsidy (via overproduction and resultant export of the surplus) result in

significant price suppression, price undercutting, or lost sales in the relevant

commodity'commodity’s international market? -

Did the subsidy result in an increase in the world market share of the subsidizing

member?

member?

For any farm program challengedchal enged under the SCM, a WTO dispute settlement panel reviewsreview s the relevant trade and market data and makes a determination of whether the particular program challenged

chal enged resulted in a significant market distortion.20

21

Under WTO rules, challengedchal enged subsidies that are found to be prohibited by a WTO dispute settlement panel must be stopped or withdrawn "“without delay"” in accordance with a timetable laid out by the panel. Otherwise the member nation bringing the challengechal enge may take appropriate

countermeasures. Similarly, actionable subsidies, if successfully challengedchal enged, must be withdrawn or altered so as to minimize or eliminate the distorting aspect of the subsidy, again as according to

a timetable laid out by a WTO panel or as negotiated between the two disputing parties.

19 For details, see CRS Report RS22522, Potential Challenges to U.S. Farm Subsidies in the WTO: A Brief Overview. 20 Part II: Prohibited Subsidies, Articles 3-4, and Part III: Actionable Subsidies, Articles 5-7, ASCM, WTO Legal Texts, http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/legal_e.htm.

21 T he final interpretation of significant is left to a WT O panel. However, two notable trade economists suggest that economic and statistical modeling can be used to show causal linkages between specific agricultural support policies and prejudicial market effects as measured by market share, quantity displacement, or price suppression. Richard H. Steinberg and T imothy E. Josling, “ When the Peace Ends: T he Vulnerability of EC and US Agricultural Subsidies to WT O Legal Challenge,” Journal of International Economic Law, vol. 6, no. 2 (July 2003), pp. 369-417.

Congressional Research Service

4

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU)

The WTO Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU)

provides a means for WTO members to resolve disputes arising under WTO agreements. WTO members must first attempt to settle their dispute through consultations, but if these fail, the member initiating the dispute may request that a panel examine and report on its complaint. The DSU provides for Appellate Body Appel ate Body review of panel reports, panels to determine if a defending member has complied with an adverse WTO decision by the established deadline in a case, and

possible retaliation if the defending member has failed to do so.

Since the WTO was established in 1995, 575598 complaints have been filed under the DSU, with nearly one-half (276280) involving the United States as a complainant or defendant.2122 The Office of

the United States Trade Representative represents the United States in WTO disputes.22

23 Questions for Evaluating WTO Compliance of Domestic Farm Spending

The United States is currently committed, under the AoA, to spend no more than $19.1 billionbil ion per year on amber box trade-distorting support. The WTO'’s AoA procedures for classifying and counting trade-distorting support are somewhat complex. However, four questions might be asked to determine whether a particular farm measure will wil cause total U.S. domestic support to be above or below the $19.1 billion bil ion annual AMS limit. A subsequent fifth question may be asked to

ascertain whether AoA-compliant outlays are also SCM-compliant.

1.1. Can the measure be classified as a"“green box"” policy—one presumed to have the least potential for distorting production and trade and therefore not counted as part of the AMS?2.2. Can it be classified as a"“blue box"” policy—that is, a production-limiting program that receives a special exemption and therefore is also not counted as part of the AMS?3.3. If it is apotentiallypotential y trade-distorting"“amber box"” policy, can supportstill bestil be excluded from the AMS calculation under the so-calledcal ed 5% de minimis- the value of total annual production if the support is non-product-

specific, or

- the value of annual production of a particular commodity if the support is specific to that commodity?

4.4. If such support exceeds the de minimis 5% threshold (and thus cannot be exempted), when it is added toallal other forms of non-exempt amber box support is total U.S. AMSstillstil beneath the $19.1billion limit?5.bil ion limit? 5. If a program is fully compliant with the AoAchallengechal enge under SCM rules. 22 WT O dispute settlement data as of December 31, 2020, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/dispu_e.htm. 23 See CRS In Focus IF10436, Dispute Settlement in the World Trade Organization: Key Legal Concepts. Congressional Research Service 5 link to page 11 Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Supportunder SCM rules.

Question 1: Can This Measure Be Placed in the Green Box?

No limits are placed on green box spending, since it is considered to be minimallyminimal y or non-trade

distorting (Figure 1). To qualify for exemption in the green box, a program must meet two general criteria, as well wel as a set of policy-specific criteria relative to the different types of

agriculture-related programs.2324 The two general criteria are the following:

1.1. It must be a publicly funded government program (defined to include either outlays or forgone revenue) that does not involve transfers from consumers.2.2. It must not have the effect of providing price support to producers.

In addition, every green-box-qualifying program must comply with at least one of the following criteria and conditions specific to the program itself:

A" A “general service"” benefitting the agricultural or rural community in general cannot involve direct payments to producers or processors. Such programs can include research; pest and disease control; training, extension, or advisory services; inspection services, including for health, safety, grading, or standardization; marketing and promotion services, including information advice and promotion (but not spending for unspecified purposes thatsellerssel ers could use to provide price discounts or other economic benefits to purchasers); andgenerallygeneral y available-

Public acquisition (at current market prices) and stockholding of products for

food security must be integral to a

nationallynational y legislated food security program and be financial y transparent. and be financially transparent. - Domestic food aid is to be based upon clearly defined eligibility

financiallyfinancial y transparent, and involve government food purchases at current market prices. "Decoupled" “Decoupled” income support is to use clearly defined eligibility-

Government financial participation in an income insurance or income safety

net program

shallshal define eligibilitycalledcal ed Olympic average), with such payment compensating for less than 70% of the income loss in year of eligibilityproducer'producer’s total loss. -

Payments (whether direct or through government crop insurance) for natural

disaster relief are to use eligibility

'’s total loss. -

Structural adjustment through producer retirement

shallshal tie eligibilitytoclearly defined criteria in programs to facilitate producers' "’ “total and permanent"” retirement from agricultural production or their movement into nonagricultural activities. -

Structural adjustment through resource retirement

shallshal be determined through clearly defined programs designed to remove land, livestock, or other resources from marketable production with payments (a) conditioned on land being retired for at least three years and on livestock being permanently disposed, (b) not contingent upon any alternative specified use of such resources involving marketing agricultural production, and (c) not related to production type/quantity or to prices of products using remaining productive resources. -

Structural adjustment provided through investment aids must be determined

by clearly defined criteria for programs assisting financial or physical restructuring of a producer

'’s operations in response to objectively demonstrated structural disadvantages (and may also be based on a clearly defined program for"“re-privatization"” of agricultural land). The amount of payments (a) cannot be tied to type/volume of production or to prices in any year after the base period, (b) shal(b) shallbe provided only for a time period needed for realization of the investment in respect of which they are provided, (c) cannot be contingent on the required production of designated products (except to require participants not to produce a designated product), and (d) must be limited to the amount required to compensate for the structural disadvantage. - Environmental program payments must have eligibility determined as part of a clearly defined government environmental or conservation program and must be dependent upon meeting specific program conditions, including conditions related to production methods or inputs. Payments must be limited to the extra costs (or loss of income) involved with program compliance.

-

Regional assistance program payments

shallshal be limited to producers in a clearly designated, contiguous geographic region with definable economic and administrative identity that are considered to be disadvantaged based on objective, clearly defined criteria in the law or regulation that indicate that theregion'region’s difficulties are more than temporary. Such payments in any year (a)shallshal not be related to or based on type/volume of production in any year after the base period (other than to reduce production) or to prices after the base period; (b) where related to production factors, must be made at a degressive rate above a threshold level of the factor concerned; and (c) must be limited to the extra costs or income loss involved in agriculture in the prescribed area.

In summary, the above measures are eligible for placement in the green box (i.e., exempted from AMS) so long as they (1) meet general criteria one and two above and (2) additionallyadditional y comply with any criteria specific to the type of measure itself. If these conditions are satisfied, no further steps are necessary—the measure is exempt. However, if not, then the next step is to determine

whether it qualifies for the blue box exemption.

Question 2: Can This Measure Be Placed in the Blue Box?

No limits are placed on blue box spending, in part because it contains safeguards to prevent program incentives from expanding production. To qualify for exemption in the blue box,2425 a

a program must be a direct payment under a production-limiting program25program26 and must also either

- be based on fixed areas and yields,

- be made on 85% or less of the base level of production, or

- if livestock payments, be made on a fixed number of head.

If these conditions are satisfied, the measure is exempt. However, if not, then it isit is considered to be an amber box policy, and the next step is to determine whether spending is above or below the

5% de minimis rate.

25 AoA, WTO Legal Texts, Article 6.5. 26 An example of a production-limiting program is the now-abandoned U.S. target-price, deficiency-payment program that linked payments to land set -aside requirements. T he target -price, deficiency-payment program was first established under the 1973 farm bill (the Agricultural and Consumer Protection Act of 1973; P.L. 93-86) and was terminated by the 1996 farm bill (T he Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 ; P.L. 104-127). As a result, the United States only notified blue box payments under this program for 1995. Congressional Research Service 8 link to page 14 link to page 14 Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support Question 3: If Amber, Will Support Exceed 5% of Production Value?

The AoA states that developed country members (including the United States), when calculating their total AMS, do not have to count the value of amber box programs whose total cost is small smal (or benign) relative to the value of either a specific commodity, if the program is commodity-specific, or the value of total production if the program is not commodity-specific.2627 In other

words, "“amber box"” (i.e., potentiallypotential y trade-distorting) policies may be excluded under the

following two de minimis exclusions:

-

Product-specific domestic support, whereby it does not exceed 5% of the

member's "member’s “total value of production of a basic agricultural product during the relevant year."” Support provided throughallal of the measures specific to a product—not just a single measure in question—istalliedtal ied to determine whether the 5% level is exceeded. For example, the value of the20162017 U.S. corn crop was$51.3 billion$49.568 bil ion, and 5% of that was $2.565 billion.27478 bil ion.28 This compares with corn- specific AMS outlays of $2.345 billion199 bil ion. Sinceit isoutlays were below the 5% product-specific de minimis threshold, the entire $2.345 billion199 bil ion was exempted from inclusion under the AMS limit20162017. In contrast, U.S. sugar support of $1.525 billion for 2016577 bil ion for 2017 easily exceeded its 5% product-specific de minimisof $117.8 millionof $124.1 mil ion (based on total sugar value of $2.4 billion)482 bil ion) and, therefore, was counted against the AMS limit. -

Non-product-specific domestic support, whereby it does not exceed 5% of the

"“value of the member'’s total agricultural production." All” Al non-product-specific support istalliedtal ied to determine whether the 5% level is exceeded. For example, the value of20162017 U.S. agricultural production was notified to the WTO as $355.5 billion.2817.8 billion.18.465 bil ion. The United States notified outlays of $7.4 billion3.442 bil ion for non-product-specific support in20162017. As a result, the entire $7.4 billion3.442 bil ion was exempted from inclusion under the AMS limit.

These provisions are known as the so-called cal ed de minimis clause. If the cost of any particular measure effectively boosts the total support above 5%, then all such support (not just the portion

of support in excess of 5%) must be counted toward the U.S. total annual AMS.

Question 4: Does Total Annual AMS Now Exceed $19.1 Billion?

Finally, all Final y, al support that does not qualify for an exemption is added for the year. If total U.S. AMS

does not exceed $19.1 billionbil ion, the WTO commitment is met (Figure 2). Through 20152017, the most recent year for which the United States has made notifications to the WTO, the United States has never exceeded its $19.1 billion bil ion amber box spending limit. The closest approach was in 1999, when the United States notified a total AMS of $16.862 billionbil ion. However, the de minimis exemptions have been instrumental in helping the United States avoid exceeding its amber box

limit in 1999, 2000, and 2001, when total AMS outlays prior to exemptions were $24.3 billion, $24.2 billion, and $21.5 billion, respectivelybil ion,

$24.2 bil ion, and $21.5 bil ion, respectively (Figure 3).

27 AoA, WTO Legal Texts, Article 6.4. 28 Data are from the U.S. notification to the WT O Committee on Agriculture, domestic support commitments (T able DS:1 and the relevant supporting tables) for the marketing year 2017, G/AG/N/USA/135, July 24, 2020. 29 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

9

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

(Figure 3).

The 2018 farm bill bil includes a provision, Section 1701 (7 U.S.C. §9091(c)), that serves as a safety trigger for USDA to adjust program outlays (subject to notification being given to both the House

and Senate agriculture committees) in such a way as to avoid breaching the AMS limit.

Question 5: Does Domestic Support Result in Significant Market Distortion in International Markets?

An additional consideration for WTO compliance—the SCM rules governing adverse market

effects resulting from a domestic farm support program—comes into play when a domestic farm policy effect spillsspil s over into international markets. This is particularly relevant for the United States because it is a major producer, consumer, exporter, and/or importer of most major agricultural commodities—but especiallyespecial y of temperate field crops (which are the main beneficiaries of U.S. farm program support). If a particular U.S. farm program is deemed to result in market distortion that adversely affects other WTO members—even if it is compliant with all al

AoA commitments and agreed-upon spending limits—then that program may be subject to challengechal enge under the WTO dispute settlement procedures. (Brazil'’s WTO case against U.S. cotton

programs is a prime example of this.)29

Conclusion

30

Conclusion The AoA'’s structure of varying spending limits across the amber, blue, and green boxes is

intentional. By leaving no constraint on spending in the green box while imposing limits on amber box spending, the WTO implicitly encourages countries to design their domestic farm

support programs to be green box compliant.30

31

Negotiations to further reform agricultural trade within the context of the WTO—referred to as the Doha Round of multilateral trade negotiations—began in 2001.3132 In 2009, negotiations hit an impasse but resumed in 2011 when ministers agreed to concentrate on topics where progress was

most likely to be made.3233 They are not expected to be completed in the near future.

As U.S. lawmakers consider policy options for agriculture, other countries will wil likely be evaluating not only whether, in their view, these options will wil comply with the U.S. commitments under the AoA but also how they reflect on the U.S. negotiating position in WTO multilateral talks. The U.S. objective, in the past, has been for the negotiations to result in substantial

reductions in trade-distorting support and for stronger rules that ensure that all al production-related support is subject to discipline (to avoid costly and time-consuming challengeschal enges via the WTO Dispute Settlement process)3334 while still stil preserving criteria-based "“green box"” policies that can support agriculture in ways that minimize trade distortions. At the same time, Congress might

seek domestic farm policy measures that it can justify as AoA- and SCM-compliant.

30 CRS Report R43336, The WTO Brazil-U.S. Cotton Case. 31 Carl Zulauf and David Orden, U.S. Farm Policy and Risk Assistance: The Competing Senate and House Agriculture Com m ittee Bills of July 2012, International Centre for T rade and Sustainable Development, http://www.ictsd.org.

32 For more information, see CRS Report RS22927, WTO Doha Round: Implications for U.S. Agriculture. 33 WT O, Agriculture Negotiations, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/agric_e/negoti_e.htm. 34 As exemplified by the recent U.S. challenge of China’s domestic support for agricultural producers. WT O, Dispute Settlement cases, DS511: China—Domestic Support for Agricultural Producers, first initiated by the United States on September 13, 2016, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds511_e.htm.

Congressional Research Service

10

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

Figure 2. U.S. Amber Box Outlays Subject to AMS Spending Limit

Source: WTO, annual notifications of the United States through 2017.

Figure 3. U.S. Amber Box Outlays Including Exemptions

Source: WTO, annual notifications of the United States through 2017. Note: In the initial WTO agreement, “developed” countries made AMS reduction commitments from a 1986-1988 base period average by 20% in six equal instal ments during 1995-2000. Amber box spending limits have been fixed since 2000 at $19.1 bil ion.

Congressional Research Service

11

Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on U.S. Domestic Support

Author Information

Randy Schnepf

Specialist in Agricultural Policy

Disclaimer

This document was prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). CRS serves as nonpartisan shared staff to congressional committees and Members of Congress. It operates solely at the behest of and under the direction of Congress. Information in a CRS Report should n ot be relied upon for purposes other than public understanding of information that has been provided by CRS to Members of Congress in

connection with CRS’s institutional role. CRS Reports, as a work of the United States Government, are not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Any CRS Report may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without permission from CRS. However, as a CRS Report may include copyrighted images or material from a third party, you may need to obtain the permission of the copyright holder if you wish to copy or otherwise use copyrighted material.

Congressional Research Service

R45305 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED

12 seek domestic farm policy measures that it can justify as AoA- and SCM-compliant.

|

|

|

Source: WTO, annual notifications of the United States through 2016. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

See CRS Report R45730, Farm Commodity Provisions in the 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334). |

| 3. |

See CRS Report R43448, Farm Commodity Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). |

| 4. |

For example, see CRS Report R42442, Expiration and Extension of the 2008 Farm Bill. |

| 5. |

The WTO is a global rules-based, member-driven organization dealing with the rules of trade between nations. As of March 7, 2019, the WTO included 164 members. See CRS In Focus IF10002, The World Trade Organization. |

| 6. |

For a complete list of WTO agreements and their text, see WTO, The Legal Texts (Cambridge University Press and World Trade Organization, 1999), https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/legal_e.htm. |

| 7. |

See CRS In Focus IF10436, Dispute Settlement in the World Trade Organization: Key Legal Concepts. |

| 8. |

See CRS Report RL32916, Agriculture in the WTO: Policy Commitments Made Under the Agreement on Agriculture. |

| 9. |

See CRS Report RS22522, Potential Challenges to U.S. Farm Subsidies in the WTO: A Brief Overview. |

| 10. |

For example, see CRS Report R43336, The WTO Brazil-U.S. Cotton Case. |

| 11. |

These spending and subsidy commitments are detailed in each member's country schedule. For more information, see CRS Report RL32916, Agriculture in the WTO: Policy Commitments Made Under the Agreement on Agriculture. |

| 12. |

WTO special and differential treatment exemptions are reserved for "developing" countries and are thus not relevant for evaluating U.S. domestic farm policy. |

| 13. |

The AoA, Part I, Article 1(a), defines AMS as the annual level of support, expressed in monetary terms, provided for an agricultural product in favor of the producers of the basic agricultural product or non-product-specific support provided in favor of agricultural producers in general other than support provided under programs that qualify for exemption as described in the remainder of this report. |

| 14. |

For developed member countries, the AMS was to be reduced from a 1986-1988 base period average by 20% in six equal annual installments during 1995-2000. For the United States, the initial 1986-88 AMS base was $23.879 billion. This was lowered to $19.103 billion by 2000, where it has been fixed ever since. |

| 15. |

General domestic support (not specific to any one commodity, such as rural infrastructure or extension) that is below 5% of the value of total agricultural production is deemed sufficiently benign that it does not have to be included in the amber box. Similarly, support for a specific commodity (such as marketing assistance loan benefits, commodity storage payments, crop insurance premium subsidies, etc.) that is below 5% of that commodity's value of production is deemed sufficiently benign that it does not have to be included in the amber box. |

| 16. |

The term red box is not actually used by the WTO but is included here to complete the traffic light analogy. |

| 17. |

WTO, "WTO Documents Online," https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S003.aspx. |

| 18. |

For details, see CRS Report RS22522, Potential Challenges to U.S. Farm Subsidies in the WTO: A Brief Overview. |

| 19. |

Part II: Prohibited Subsidies, Articles 3-4, and Part III: Actionable Subsidies, Articles 5-7, ASCM, WTO Legal Texts, http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/legal_e.htm. |

| 20. |

The final interpretation of significant is left to a WTO panel. However, two notable trade economists suggest that economic and statistical modeling can be used to show causal linkages between specific agricultural support policies and prejudicial market effects as measured by market share, quantity displacement, or price suppression. Richard H. Steinberg and Timothy E. Josling, "When the Peace Ends: The Vulnerability of EC and US Agricultural Subsidies to WTO Legal Challenge," Journal of International Economic Law, vol. 6, no. 2 (July 2003), pp. 369-417. |

| 21. |

WTO dispute settlement data as of June 3, 2019, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/dispu_e.htm. |

| 22. |

See CRS In Focus IF10436, Dispute Settlement in the World Trade Organization: Key Legal Concepts, by Brandon J. Murrill. |

| 23. |

The so-called green box is actually Annex 2 of the AoA, WTO Legal Texts. |

| 24. |

AoA, WTO Legal Texts, Article 6.5. |

| 25. |

An example of a production-limiting program is the now-abandoned U.S. target-price, deficiency-payment program that linked payments to land set-aside requirements. The target-price, deficiency-payment program was first established under the 1973 farm bill (the Agricultural and Consumer Protection Act of 1973; P.L. 93-86) and was terminated by the 1996 farm bill (The Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996; P.L. 104-127). As a result, the United States only notified blue box payments under this program for 1995. |

| 26. |

AoA, WTO Legal Texts, Article 6.4. |

| 27. |

Data are from the U.S. notification to the WTO Committee on Agriculture, domestic support commitments (Table DS:1 and the relevant supporting tables) for the marketing year 2016, G/AG/N/USA/123, October 31, 2018. |

| 28. |

Ibid. |

| 29. |

CRS Report R43336, The WTO Brazil-U.S. Cotton Case. |

| 30. |

Carl Zulauf and David Orden, U.S. Farm Policy and Risk Assistance: The Competing Senate and House Agriculture Committee Bills of July 2012, International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, http://www.ictsd.org. |

| 31. |

For more information, see CRS Report RS22927, WTO Doha Round: Implications for U.S. Agriculture. |

| 32. |

WTO, Agriculture Negotiations, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/agric_e/negoti_e.htm. |

| 33. |

As exemplified by the recent U.S. challenge of China's domestic support for agricultural producers. WTO, Dispute Settlement cases, DS511: China—Domestic Support for Agricultural Producers, first initiated by the United States on September 13, 2016, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds511_e.htm. |