U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network: Overview and Issues for Congress

Changes from April 18, 2019 to March 2, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network: Overview and Issues for Congress

Contents

- Introduction

- What Is a Streamgage?

- Streamgage Uses

- Examples of Streamgage Uses

- Network Structure

- Cooperative Matching Funds Program

- Federal Priority Streamgages

- Network Funding

- USGS Funding Trends

- Issues for Congress

- Funding Considerations

- Addressing the Size of the Network

- Restoration of Streamgages

- Modernizing the USGS Streamgaging Network

- Balancing Policy Options

- Pursuing Both the FPS Mandate and the NextGen System

- Amending the SECURE Water Act of 2009

- Replacing the FPS Network with NextGen System

Figures

- Figure 1. USGS Streamgaging Network Structure and Number of Streamgages

- Figure 2. Diagram of a Streamgage Measuring Stream Stage Height

- Figure 3. Discharge Graph Capturing Streamflow during Hurricane Florence

- Figure 4. Number of National Streamflow Network Streamgages in U.S. States and Territories in 2018

- Figure 5. Number of USGS Streamgages and Policy Changes over Time

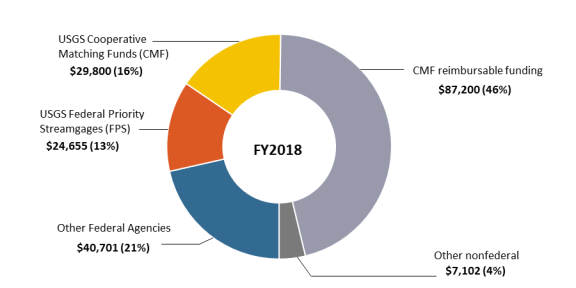

- Figure 6. FY2018 Funding for the USGS Streamgaging Network

- Figure 7. USGS Funding for the Streamgaging Network

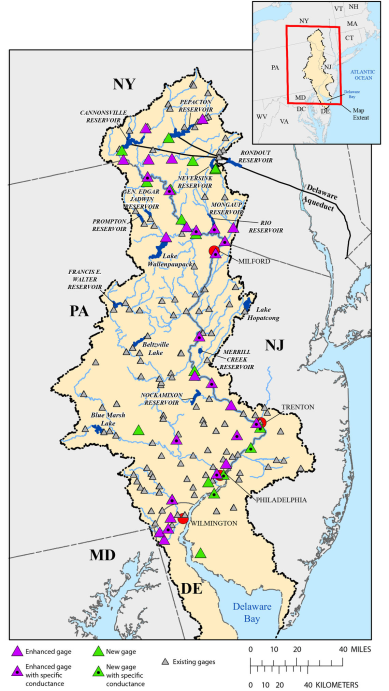

- Figure 8. Map of the Planned Next Generation Integrated Water Observing System (NextGen) Pilot in the Delaware River Basin

Summary

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging

March 2, 2021

Network: Overview and Issues for Congress

Anna E. Normand

Streamgages are fixed structures at streams, rivers, lakes, and reservoirs that measure water level

Analyst in Natural

and related streamflow—the amount of water flowing through a water body over time. The U.S.

Resources Policy

Geological Survey (USGS) in the Department of the Interior operates streamgages in every state,

the District of Columbia, and the territories of Puerto Rico and Guam. The USGS Streamgaging Network encompasses 10,30011,340 streamgages, which record water levels or streamflow for at least a

portion of the year. Approximately 8,200460 of these streamgages measure streamflow year round as part of the National Streamflow Network. The USGS also deploys temporary rapid deployment gages to measure water levels le vels during storm events, and select streamgages measure water quality.

Streamgages provide foundational information for diverse applications that affect a variety of constituents. The USGS disseminates streamgage data free to the public and responds to over 670887 million requests on streamflows annually. Direct users of streamgage data include a variety of agencies at all levels of government, private companies, scientific institutions, and recreationists. Data from streamgages inform real-time decisionmaking and long-term planning on issues such as water management and energy development, infrastructure design, water compacts, water science research, flood mapping and forecasting, water quality, ecosystem management, and recreational safety.

Congress has provided the USGS with authority and appropriations to conduct surveys of streamflow since establishing the first hydrological survey in 1889. Many streamgages are operated cooperatively with nonfederal partners, whowhich approach the USGS and sign joint-funding agreements to share the cost of streamgages and data collection. The USGS Cooperative Matching Funds (CMF) Program provides up to a 50% federal match with tribal, regional, state, and local partners, as authorized by 43 U.S.C. §50. The average nonfederal cost-share contribution has increased from approximately 50% in the early 1990s to 63% in FY2018. approximately 69% in FY2020. In the early 2000s, the USGS designated federal priority streamgage (FPS) locations based on five identified national needs. The SECURE Water Act of 2009 (Title IX, Subtitle F, of o f P.L. 111-11) ) directed the USGS to operate by FY2019 no less no fewer than 4,700 federally funded streamgages by FY2019. In FY2020, 3,470. In FY2018, 3,640 of the 4,760 FPSs designated by the USGS were operational, with 52% of their funding from the USGS.

35% of FPSs funded solely by the USGS FPS program funds and the rest funded by a combination of federal and nonfederal funds.

Congressional appropriations and agreements with 1,400 nonfederal partners funded USGS streamgages at $189.5194.9 million in FY2018. FY2020. The USGS share included $24.7 million for FPSs and $29.84 million for cooperative streamgages through CMF. A dozen other federal agencies provided $40.738.0 million. Nonfederal partners, mostly affiliated with CMF, provided $94.3 102.8 million. In FY2019, FY2021, Congress appropriated level fundingthe same amount of funding as in FY2020 for FPS and CMF streamgages. Congress apropropriated $24.5 million in FY2021 for the Next Generation Congress directed an additional $8.5 million to pilot a Next Generation Integrated Water Observing System (NextGen), establishing dense networks of streamgagesNGWOS), an effort to establish dense water monitoring networks in representative watersheds in order to model streamflow in analogous watersheds.

watersheds. The President's budget request for FY2020 does not include NextGen system funding and would reduce CMF for streamgages by $250,000.

The USGS uses appropriated funding to develop and maintain the USGS Streamgaging Network. The USGS and numerous stakeholders have raised funding considerations including user needs, priorities of partners, federal coverage, infrastructure repair, disaster response, inflation, and technological advances. Some stakeholders advocate for maintaining or expanding the network. Others may argue that Congress should consider reducing the network in order to prioritizeprio ritize other activities and that other entities operate streamgages tailored to localized needs. Congress might also consider whether to invest in streamgage restoration and new technologies.

Congress may consider outlining the future direction for the USGS Streamgaging Network through oversight or legislation. As the USGS facesThe USGS failed to meet a deadline set by the SECURE Water Act of 2009 to operate no lessfewer than 4,700 FPSs by FY2019, Congress directed. Congress has provided level funding for FPSs while directing the USGS through appropriations legislation to invest in the NextGen systemincrease investment in the NGWOS. Congress may consider such policy options as pursuing both the FPS mandate and the NextGen system NGWOS simultaneously, amending the SECURE Water Act of 2009, and determining the relative emphasis of the NextGen system.

Introduction

NGWOS in the

agency’s streamgaging enterprise.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 22 link to page 29 link to page 29 link to page 20 link to page 32 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 What Is a Streamgage?..................................................................................................... 2 Streamgage Uses............................................................................................................. 5

Examples of Streamgage Uses ..................................................................................... 6

Network Structure ........................................................................................................... 9

Cooperative Matching Funds Program ........................................................................ 10 Federal Priority Streamgages ..................................................................................... 12 Next Generation Water Observing System ................................................................... 14

Network Funding .......................................................................................................... 15

USGS Funding Trends.............................................................................................. 17

Issues for Congress ....................................................................................................... 19

Funding Considerations ............................................................................................ 19

Addressing the Size of the Network ...................................................................... 19 Restoration of Streamgages.................................................................................. 22 Modernizing the USGS Streamgaging Network ...................................................... 23

Balancing Policy Options.......................................................................................... 26

Pursuing Both the FPS Mandate and the NGWOS ................................................... 26 Amending the SECURE Water Act of 2009 ............................................................ 27 Replacing the FPS Network with the NGWOS........................................................ 27

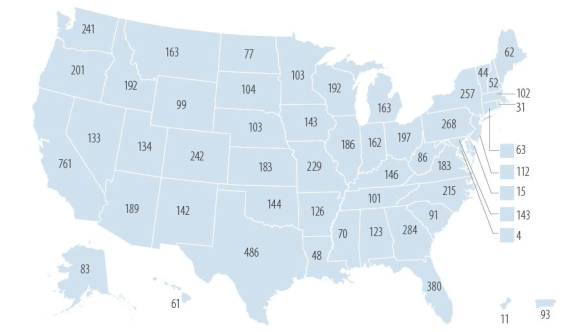

Figures Figure 1. USGS Streamgaging Network Structure and Number of Streamgages ........................ 1 Figure 2. Diagram of a Streamgage Measuring Stream Stage Height ....................................... 3 Figure 3. Discharge Graph Capturing Streamflow During Hurricane Isaias .............................. 4 Figure 4. USGS Streamgage Informing Recreational Activities .............................................. 9 Figure 5. Number of National Streamflow Network Streamgages in U.S. States and

Territories in 2020 ...................................................................................................... 10

Figure 6. Number of USGS Streamgages and Policy Changes over Time ............................... 12 Figure 7. FY2020 Funding for the USGS Streamgaging Network ......................................... 15 Figure 8. USGS Funding for the Streamgaging Network ..................................................... 18 Figure 9. Map of the Next Generation Water Observing System (NGWOS) in the

Delaware River Basin ................................................................................................. 25

Tables Table 1. FY2020 Funding and Streamgages Supported by Other Federal Agencies .................. 16

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 28

Congressional Research Service

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network: Overview and Issues for Congre

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 16 link to page 16

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Introduction Streamgages measure water level and related streamflow at streams, rivers, lakes, and reservoirs across the country. Streamgages provide foundational information for diverse applications that

affect a variety of constituents. Congress has supported a national streamgage program for over 130 years.11 These streamgages operate in every state, the District of Columbia, and the territories of Puerto Rico and Guam; therefore, national streamgage. The widespread use of national streamgages and their operations garner interest from many Members of Congress. Data fromfrom streamgages informs real-time decisionmaking and long-term planning on issues such as hazard preparations and response, infrastructure design, water use allocationsal ocations, ecosystem management, and recreation.22 Direct users

of streamgage data include a variety of agencies from all al levels of government, utility companies,

consulting firms, scientific institutions, and recreationists.3

Streamgages are operated across the globe with national programs in North America,

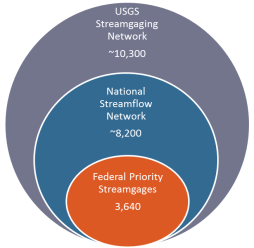

Figure 1. USGS Streamgaging Network

Europe, Australia, and Brazil, consulting firms, scientific institutions, and recreationists.3

Streamgages are operated across the globe with national programs in North America, Europe, Australia, and Brazil, among others.4 among others.4

Structure and Number of Streamgages

In the United States, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Department of the Interior'Interior’s (DOI'’s) lead scientific agency,

manages the USGS Streamgaging Network (Figure 1). The network encompasses 10,300approximately 11,340 streamgages that record water height or streamflow for at least a portion of the year. Approximately 8,200460 of

these streamgages measure streamflow year-round and are part of the National Streamflow Network. This subnetwork includes 3,640 470 Federal Priority Streamgages (FPSs), which Congress and the USGS designated as

national priorities (see section on "“Federal Priority Streamgages”"). Some entities, such as

state governments, operate their own

Source: CRS with data from USGS Groundwater

streamgages separate from the USGS

and Streamflow Information Program.

Streamgaging Network.5

Notes: The National Streamflow Network is a subset of the USGS Streamgaging Network, and

Congressional appropriations and agreements

Federal Priority Streamgages are a subset of the

with approximately 1,400 nonfederal partners

National Streamflow Network.

1 Congress has provided the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) with the authority and appropriations to conduct surveys of streamflow since establishing the first hydrological survey in 1889. 28 Stat. 910 funded the first irrigation survey to be conducted by the USGS.

2 National Hydrologic Warning Council (NHWC), Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program , 2006, at https://water.usgs.gov/osw/pubs/nhwc_report.pdf. Hereinafter NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program. 3 T he Coalition Supporting the USGS National Water Monitoring Network, for example, which represents an array of stakeholders (local agencies, river compact commissions, environmental nonprofits, professional societies, and recreational groups), frequently advocates for USGS streamgage funding.

4 Albert Ruhi, Mathis L. Messager, and Julian D. Olden, “T racking the Pulse of the Earth’s Fresh Waters,” Nature Sustainability, vol. 1, no. 4 (2018), p. 199. Hereinafter Ruhi, Earth’s Fresh Waters.

5 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 14 link to page 7 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

funded the USGS Streamgaging Network at $194.9 mil ion in FY2020.6state governments, operate their own streamgages separate from the USGS Streamgaging Network.5

Congressional appropriations and agreements with approximately 1,400 nonfederal partners funded the USGS Streamgaging Network at $189.5 million in FY2018.6 Some streamgages are funded solely through congressional appropriations for the USGS and other federal agencies, such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), and Department of Defense (DOD). Much of the USGS Streamgaging Network is funded cooperatively. Interested parties sign funding agreements with the USGS to share the cost of streamgages and data collection.77 The USGS Cooperative Matching Funds Program (CMF)

provides up to a 50% match with tribal, regional, state, and local partners (see section on "“Cooperative Matching Funds Program").8”).8 Other federal agencies, nonfederal governments, and nongovernmental entities may provide reimbursable funding for streamgages in the USGS

Streamgaging Network without contributed funds from the USGS.9

9

Evolving federal policies and user needs from diverse stakeholders have shaped the size, organization, and function of the USGS streamgage program. This report provides an overview of federal streamgages by describing the function of a streamgage, the data available from streamgage measurements, and the uses of streamgage information. The report also outlines the

structure and funding of the USGS Streamgaging Network and discusses potential issues for

Congress, such as funding priorities and the future structure of the nation'’s streamgage network.

What Is a Streamgage?

A streamgage'’s primary purpose is to collect data on water levels and streamflow (the amount of water flowing through a river or stream over time).1010 Streamgages estimate streamflow based on

(1) continuous measurements of stage height (the height of the water surface) and (2) periodic measurements of streamflow, or discharge, in the channel and floodplains.1111 USGS measurements are used to create rating curves, in order to convert continuously measured stage heights into estimates of streamflow.1212 Selected streamgages may provide additional measurements, such as

measurements of water quality (see box on "Supergages").

“Supergages”).

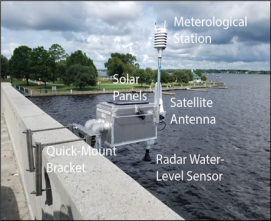

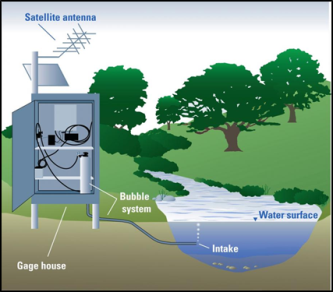

Streamgages house instruments to measure, store, and transmit stream stage height (Figure 2).13 13 Stage height is usuallyusual y transmitted every hour, or more frequently at 5 to 15 minute intervals for

6 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020. T he appropriations bill for Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies funds the USGS share of the USGS Streamgaging Network under the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program.

7 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, April 9, 2019.

8 43 U.S.C. §50. “ T he share of the United States Geological Survey in any topographic mapping or water resources data collection and investigations carried on in cooperatio n with any State or municipality shall not exceed 50 per centum of the cost thereof.” 9 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 15, 2018.

10 T his section describes the basics of streamgaging specific to the USGS operations of continuously measuring streamflow. Over 2,000 streamgages in the USGS Streamgaging Network only record water level or operate less than year-round. 11 Stephen Blanchard, Recent Improvements to the U.S. Geological Survey from the National Streamflow Information Program , USGS, FS 2007-3080, 2007, at http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3080/index.html.

12 Rating curves are relationships between stage height and streamflow. T he USGS develops rating curves using streamflow measurements over range of stage heights.

13 Vernon Sauer and Phil T urnipseed, Stage Measurement at Gaging Stations, U.S. Geological Survey T echniques and Methods Book 3, Chapter A7, 2010, at https://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/tm3-a7/.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 8

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

transmitted every hour, or more frequently at 5 to 15 minute intervals for emergency or priority streamgages.1414 Most streamgages transmit data by satellitesatel ite to USGS computers; the data then are provided online to the public. 15 15 Numerous streamgages also have

cameras that capture and transmit photos of streamflow conditions.16

16 Figure 2. Diagram of a Streamgage Measuring Stream Stage Height |

|

Source: Dee Lurry, . Notes: This figure depicts a streamgage |

Periodic streamflow measurements require USGS personnel to measure discharge at various sections across the stream.1717 Streamflow measurements are made every six to eight weeks to capture a range of stage heights and streamflows, especiallyespecial y at high and low stage heights.

Repeated measurements allowal ow scientists to capture changes to the channel from vegetation growth, sedimentation, or erosion, which can affect the relationship between stage height and streamflow.

streamflow.

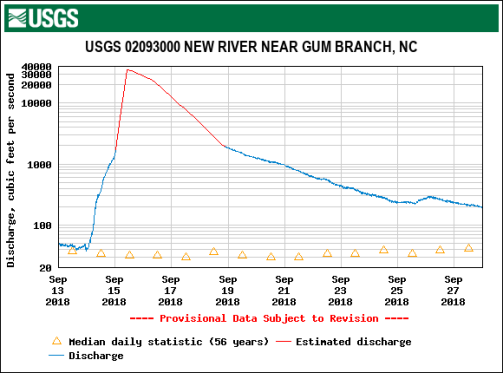

The USGS National Water Information System (NWIS) receives and converts all stream height data from USGS streamgages into streamflow estimates.1818 An example of streamgage data from NWIS is shown inin Figure 3 for a site capturing peak streamflow during a hurricane event. The free and

14 J. Michael Norris, From the River to You: USGS Real-Time Streamflow Information, USGS, FS 2007-3043, 2007, at https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3043/.

15 Streamgages are increasingly employing cellular and radio telemetry as an additional way to transmit and serve data online. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, February 19, 2019.

16 An example of a streamgage camera can be accessed at https://ca.water.usgs.gov/webcams/. 17 Phil T urnipseed and Vernon Sauer, Discharge Measurements at Gaging Stations, U.S. Geological Survey T echniques and Methods Book 3, Chapter A8, 2010, at https://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/tm3-a8/.

18 T he USGS Surface-Water Data for the Nation, National Water Information System: Web Interface houses streamgage data at https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis. Users may select various USGS monitoring sites across the United States to access streamflow and other field measurements using USGS National Water Information System: Mapper at https://maps.waterdata.usgs.gov.

Congressional Research Service

3

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

for a site capturing peak streamflow during a hurricane event. The free and publicly accessible data are frequently accessed online or by request to users.1919 For example, the agency responded to over 670 millionin FY2020, there were 52.3 mil ion visits to the NWIS website and NWIS responded to over 887 mil ion human and automated requests for streamflow and water level information in 2018.20.20 The NWIS website is the main repository for current and historical streamflow data, in addition to other water information. Tools such as WaterWatch summarize the current conditions of the nation's ’s streams and watersheds through maps, graphs, and tables by comparing real-time streamflow

conditions to historic streamflow from streamgages with records of 30 years or more.21

21

Figure 3. Discharge Graph Capturing Streamflow |

|

Notes: The discharge graph is derived from one of 18 streamgages recording new peak streamflows during Hurricane Florence. Because stage height measurements were record-breaking, previous rating curves could not provide accurate discharge from September 15 to September 19, 2018; thus, discharge was estimated in red. |

https://waterdata.usgs.gov/md/nwis. Notes: The discharge graph is derived from a streamgage capturing a spike in streamflow during Hurricane Isaias. The USGS may sometimes measure discharge onsight by hand (red shape) during such events to validate streamgage data and improve rating curves that estimate discharge based on stage height. The vertical axis showing discharge is a logarithmic scale.

19 Users can send an email or text to receive instant information about a specific streamgage with USGS WaterNow (accessible at https://water.usgs.gov/waternow), or they can sign up to receive alerts about stream conditions with USGS WaterAlert (accessible at https://maps.waterdata.usgs.gov/mapper/wateralert/). Other partnership applications using Geographic Information System (GIS) interfaces include StreamStats (accessible at https://streamstats.usgs.gov), and T X Water on the Go and T X Water Dashboard (accessible at https://waterdata.usgs.gov/tx/nwis/rt).

20 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

21 USGS WaterWatch is accessible at https://waterwatch.usgs.gov.

Congressional Research Service

4

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Streamgage Uses Streamgage Uses

The USGS Streamgaging Network provides streamflow information to assist during natural and man-made disasters, such as flooding and drought, and to inform economic and statutory water management decisions, such as the allocational ocation of water supplies for irrigation. Individual streamgages in the network also can serve multiple uses. For example, a streamgage intentionally intentional y established for the purpose of reservoir management may provide data to inform water quality

standards, habitat assessments, and recreational activities.22 Additionally, 22 Additional y, the value of a single streamgage is enhanced by the operation of the entire network, particularly for research,

modeling, and forecasting.

Streamgages were first established in the United States to inform water use and infrastructure planning—applications that benefit from continuous, long-term hydrologic records (see box on "“Evolution of Streamgage Uses").23”).23 Long and continuous periods of data are used to construct baselines for water conditions and to identify deviations in the amount and timing of streamflow caused by changes in land use, water use, and climate.2424 Some stakeholders contend that the value

of streamflow records increases over time, with at least 20 years of continuous coverage needed

for many applications.25

25 Evolution of Streamgage Uses

A decade after the establishment of the U.S. Geological By 1900, there were

|

Technological advances allowingal owing access to streamflow information in real time have expanded the uses of streamgages. Real-time forecasting and operational decisionmaking are used in many applications of streamflow data.2626 Web and phone applications also have facilitated increased

public use of water information.27

27 Examples of Streamgage Uses

Streamgage data is used for a wide range of applications, including supporting activities of federal agencies. There are also a variety of streamgages tailored for specific purposes. The following is a noncomprehensive selection of streamgage uses to illustrateil ustrate the scope of

applications.

Water Management and Energy Development the scope of applications.

Water Management and Energy Development. USACE, Reclamation, and various state and

local water management agencies use streamgages to inform the design and operation of thousands of water management projects across the nation.2828 Timely streamflow information helps water managers make daily operational decisions as they balance water requirements for municipal, industrial, and agricultural uses. Energy production and mineral extraction operations also rely on continuous streamflow measurements to comply with environmental, water quality, or temperature requirements.2929 For example, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)

requires hydropower companies to support USGS streamflow and water-level monitoring as part of their

FERC licensing process.30

30

Infrastructure Design. Transportation agencies use streamflow data to develop regional flow frequency curves for the design of bridges and culverts, stream stability measuresmeasurements, and analysis of bridge scour—the leading cause of bridge failure.3131 Without adequate information, some observers contend that engineers may overdesign structures, resulting in greater costs, or

may not make proper allowancesal owances for floods, compromising public safety.32

32

Interstate and International Water RightsRights. Federal streamgages are used to collectcol ect streamflow information at U.S. borders and between states.3333 Streamgage data informs interstate compacts, Supreme Court decrees, and international treaties (e.g., treaties under the purview of the

International Boundary and Water Commission and the International Joint Commission).

Water Science ResearchResearch. Many federal agencies depend on consistent, long-term data from streamgages to conduct water research and modeling (e.g., USACE, National Oceanic and 26 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program. 27 USGS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2017 , J - Water Resources. 28 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program. 29 Wahl, USGS Circular 1123. 30 T he Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) licenses the construction and operation of nonfederal hydropower project pursuant to the Federal Power Act of 1935, 16 U.S.C. §797(a)(c). 31 Bridge scour is the removal of sediment from the base of bridge structures. NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program, p. 8.

32 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program, p. 8. 33 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program, p. 12.

Congressional Research Service

6

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

streamgages to conduct water research and modeling (e.g., USACE, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], DOI, U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], and National Aeronautic and Space Administration [NASA]).3434 To monitor climate trends and ecological patterns, the USGS distinguishes a subset of streamgages that are largely unaffected by development to serve as benchmarks for natural conditions.35

conditions.35 National Water Model

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric |

Flood; Brian A. Cosgrove, NOAA, NOAA’s National Water Model: From V2.1 Operations to Future Enhancements in V3.0, American Geophysical Union, 2020 Fal Conference.

Flood Mapping. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) uses floodplain maps to establish flood risk zones and requires flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) for properties with a 1% annual chance of flooding.3836 Long-term streamflow records are used to determine 1% annual chance flood flows and to develop water surface profiles to map areas at risk of flooding. The USGS often works with FEMA to produce new inundation

maps after streamgages record new streamflow peaks from weather events such as hurricanes.39

Emergency Forecasting37

Emergency Forecasting and Response. Streamgages inform flood forecasting and emergency

response to protect lives and property.4038 Real-time data from more than 3,600 streamgages allow NOAA's National 6,780 streamgages al ow NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) river forecasters to model watershed response, project future streamflows, forecast monthly to seasonal water availability, and issue appropriate flood watches and warnings (see box on "“National Water Model").41”).39 Flood warnings provide lead time

34 Advances in satellite observations also depend on streamgages to calibrate stream discharge models. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), Future Water Priorities for the Nation: Directions for the U.S. Geological Survey Water Mission Area , Washington, DC, 2018, pp. 8 and 66, at https://doi.org/10.17226/25134. Hereinafter NASEM, Future Water Priorities for the Nation.

35 T hese are referred to as sentinel basins, according to the National Research Council (NRC), Assessing the National Stream flow Inform ation Program , pp. 57-59, at https://doi.org/10.17226/10967. Hereinafter NRC, Assessing the NSIP.

36 41 U.S.C. §§4011 et seq. See CRS Report R44593, Introduction to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), by Diane P. Horn and Baird Webel. Because the 1% annual exceedance probability flood has a 1 in 100 chance of being equaled or exceeded in any one year and an average recurrence interval of 100 years, it often is referred to as the 100-year flood. Robert R. Holmes, “ T he 100-Year Flood - It’s All About Chance,” USGS, at https://water.usgs.gov/edu/100yearflood-basic.html. 37 Kara Watson et al., Characterization of Peak Streamflows and Flood Inundation of Selected Areas in Southeastern T exas and Southwestern Louisiana from the August and September 2017 Flood Resulting from Hurricane Harvey, USGS, Scientific Investigations Report 2018–5070, 2018, at https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20185070.

38 William J. Carswell and Vicki Lukas, The 3D Elevation Program – Flood Risk Management, USGS, FS 2017-3081, 2018, at https://doi.org/10.3133/fs20173081. 39 T he Secretary of Commerce is charged with flood warning and reporting on river conditions pursuant to the National

Congressional Research Service

7

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Flood warnings provide lead time for emergency response agencies, such as FEMA, to take effective action in advance of rising waters.4240 In addition, the USDA National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) uses streamgages to forecast flows for water supply, drought management and response, hydroelectric

production, irrigation, and navigation in western states.43

41 Rapid Deployment Gages

Rapid deployment gages (RDGs) are temporarily Dorian in 2019. Source: USGS, Rapid FEV.

Notes: This fixed design can also be used for permanent streamgages.

Water Quality. Streamflow data is important for measuring water quality and developing water quality standards for sediments, pathogens, metals, nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus), and organic compounds (e.g., pesticides). At select streamgages, the USGS also operates instruments recording water quality data (see box on “Supergages”). Section 303(d) of the Clean

Supergages

Water Act requires states to develop total

Supergages are a smal subset of streamgages (just over

maximum daily load (TMDL) management

510) that col ect chemical data in addition to

plans for water bodies determined to be water

streamflow |

|

|

Water Quality. Streamflow data is important for measuring water quality and developing water quality standards for sediments, pathogens, metals, nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus), and organic compounds (e.g., pesticides). At select streamgages, the USGS also operates instruments recording water quality data (see box on "Supergages"). Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act requires states to develop total maximum daily load (TMDL) management plans for water bodies determined to be water quality impaired by one or more pollutants.44 When determining TMDL levels for specific pollutants, agencies may consider historic streamflow data, along with other factors, in their evaluations. Agencies may use current flow conditions when determining the proper release of wastewater to ensure compliance with TMDL standards and National Discharge Elimination System permitting.45

Ecosystem Management and Species. Some water users and resource agencies use streamflow data to meet the flow requirements needed to protect endangered or threatened fish and wildlife under the Endangered Species Act (16 U.S.C. §1531 et seq.). Natural resource agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), collect streamflow data to understand how threatened and endangered species respond to flow variations.4644 The USGS operates streamgages to monitor

ecosystem restoration progress, such as restoration of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.45

Recreation. Real-time streamgage data can help individuals and tourism businesses assess stream conditions for recreational outings.46 USGS data can be used to decide if conditions are suitable

for recreational activities such as fishing, boating, and rafting (see Figure 4). The USGS also partners with the National Park Service (NPS) to provide water science and data to help manage

parks and to enhance interpretive programs.

Figure 4. USGS Streamgage Informing Recreational Activities

Source: Photo by Edward Gertler. Notes: The streamgage (https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/uv?site_no=01619500) in the left-facing part of the photo helps inform recreational paddling, among other uses, in Antietam Creek, which flows through Antietam National Battleground.

Network Structure The USGS Streamgaging Network is part of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program under the USGS Water Resources mission area.47 The primary operators of streamgages

44 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program, p. 10. 45 Scott Phillips et al., U.S. Geological Survey Chesapeake Science Strategy, 2015 -2025—Informing Ecosystem Management of America’s Largest Estuary, USGS, Open-File Report 2015–1162, 2015, at https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151162.

46 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program, p. 14. 47 USGS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information: Fiscal Year 2019 , pp. 79-93, at https://prd-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/atoms/files/

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 14

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

ecosystem restoration progress, such as restoration of the Chesapeake Bay watershed.47

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has initiated a Next Generation Integrated Water Observing System (NextGen) "to provide high-fidelity, real-time data on water quantity and quality necessary to support modern water prediction and decision support systems for water emergencies and daily water operations." The USGS plans to develop dense networks of streamgages in medium-sized watersheds (each approximately 15,000 square miles) representative of larger water-resource regions. The USGS would also make modest enhancements to the existing streamgage network. Fully implemented, the NextGen system would provide quantitative information on streamflow, snowpack, loss of water to the atmosphere, soil moisture, water quality, groundwater, and water usage. The USGS contends that a suite of highly monitored watersheds, in combination with an enhanced streamgage network and other relevant data sets, can better inform advanced models (e.g., the National Water Model) and water information and forecasts. In an effort to assess this approach, the USGS started a multiyear NextGen system pilot project in the Delaware River Basin in FY2018. The USGS plans to install 17 new streamgages and modernize 28 streamgages in the basin; the streamgages will be equipped with two-way communication for remote operation and troubleshooting, cell and satellite transmission redundancy, real-time water temperature monitoring, and webcams and water quality sensors at select sites. The USGS anticipates expanding the concept to approximately a dozen representative basins.

|

Recreation. Real-time streamgage data can help individuals and tourism businesses assess stream conditions for recreational outings.48 USGS data can be used to decide if conditions are suitable for recreational activities such as fishing, boating, and rafting. The USGS also partners with the National Park Service (NPS) to provide water science and data to help manage parks and to enhance interpretive programs.

Network Structure

The USGS Streamgaging Network is part of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program under the USGS Water Resources mission area.49 The President's budget request for FY2020 proposes a restructuring of the mission area to create a Water Observing Systems Program that would combine the USGS Streamgaging Network and other water observation programs.50 The primary operators of streamgages are the regional and state USGS Water Science Centers, which maintain hydrologic data are the regional and state USGS Water Science Centers, which maintain hydrologic data

collection and conduct water research in the region.51

48

Approximately 8,200460 of the 10,30011,340 USGS streamgages measure year-round streamflow (National

Streamflow Network; seesee Figure 45), with the rest only measuring stage height or measuring streamflow on a seasonal basis.49 USGS streamgages are also differentiated based on cooperative funding (CMF)

and federal interest (FPSs).

Cooperative Matching Funds Program

Much of the streamgaging program has been cooperative in nature as interested parties sign funding agreements to share the cost of streamgages and data collection.5250 Through CMF, the

FY2019%20USGS%20Budget%20Justification%20%28Greenbook%29.pdf . 48 A list of USGS Water Science Centers can be found at https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/about/water-resources-mission-area-science-centers-and-regions.

49 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

50 U.S. Government Accountability Office, Environmental Information, Status of Federal Data Programs that Support Ecological Indicators, 05-376, 2005, pp. 164-174, https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d05376.pdf. Hereinafter GAO, Federal Data Programs.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 16 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Through CMF, the USGS funds up to a 50% match with tribal, regional, state, and local partners.53 In 201851 In FY2020, CMF

partial y , CMF supported 5,345273 streamgages (5246% of the gages in the USGS Streamgaging Network).

52

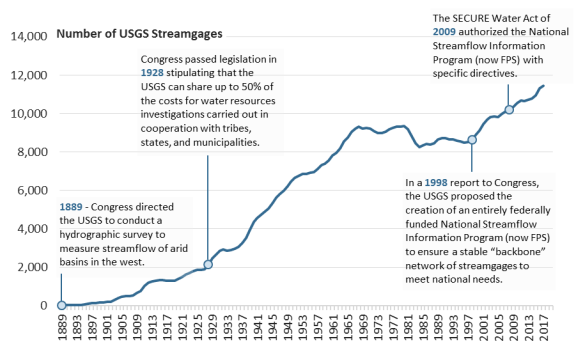

The first cooperative agreement began in 1895 with the Kansas Board of Irrigation Survey and

Experiment (now known as the Division of Water Resources of the Kansas Department of Agriculture).5453 Funds from cooperative entities steadily increased in the early 20th century.55 20th century.54 Congress passed legislation in 1928 stipulating that the USGS can share up to 50% of the costs for water resources investigations carried out in cooperation with tribes, states, and municipalities (see(see Figure 5).566).55 In 2016, this Federal-State Cooperative Water Program was renamed the

Cooperative Matching Funds Program (CMF), which provides cooperative funding for programs

across the USGS Water Mission Area.57

56

To participate in the CMF, potential partners approach the USGS to discuss the need for a specific

streamgage. The USGS determines its feasibility based on available funds and program priorities. If the USGS deems establishing the streamgage is feasible, the USGS and cooperator sign a joint funding agreement (JFA), which is a standard agreement that specifies how much each party will wil contribute to funding the streamgage and the payment schedule for the cooperator.5857 These agreements span five years or less. During the agreement, the cost-share generallygeneral y remains the

same, but there is flexibility to alter the cost-share on an annual basis for multi-year agreements. Once a streamgage is operating, if a partner can no longer contribute funds, the USGS seeks to work with other partners that use the streamgage to augment funding. The USGS provides a website identifying streamgages that are in danger of being discontinued or converted to a reduced level of service due to lack of funding.5958 The website also identifies streamgages that

have been discontinued or are being supported by a new funding source.

Approximately 3,700900 of the 10,30011,340 USGS streamgages (3635%) are funded by nonfederal and federal partners without matching funds from the USGS (i.e., not with CMF).59 Nonfederal

partners sign JFAs, and federal partners share interagency agreements with the USGS (except USACE USACE which uses a military interdepartmental purchase request).6060 These gages are part of the USGS Streamgaging Network and are operated in accordance with the quality control and public

51 43 U.S.C. §50. “ T he share of the United States Geological Survey in any topographic mapping or water resources data collection and investigations carried on in cooperation with any State or municipality shall not exceed 50 per centum of the cost thereof.” 52 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020. 53 Wahl, USGS Circular 1123. 54 Mary Rabbitt, A Brief History of the U.S. Geological Survey, USGS, DOI 10.3133/70039204, Washington, DC, 1975.

55 P.L. 70-100. 56 USGS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2016, J - Water Resources, https://prd-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/atoms/files/FY2016%20USGS%20Budget%20Justification%20%28Greenbook%29.pdf . Hereinafter USGS, FY2016 Budget.

57 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Informat ion Program, USGS, April 9, 2019. 58 Discontinued, threatened, or revived streamgages can be explored through an interactive map at https://water.usgs.gov/networks/fundingstability.

59 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

60 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, April 9, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

11

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

USGS Streamgaging Network and are operated in accordance with the quality control and public access standards created by the USGS, with the agency assuming liability responsibility for the

streamgages.

Public and private entities may also elect to own and operate streamgages tailored to their specific

needs and not affiliated with the USGS. These independent streamgages may differ in various ways compared to streamgages in the USGS Streamgaging Network (e.g., capital and operating

costs, operating periods, measurement capabilities, and data standards and platforms).61

Federal Priority Streamgages

The SECURE Water Act of 2009 (Title IX, Subtitle F of P.L. 111-11) directs) directed the USGS to operate a reliable set of federallyfederal y funded streamgages. The law requiresrequired the USGS to fund no fewer than 4,700 sites complete with flood-hardened infrastructure, water quality sensors, and modernized telemetry by FY2019. Originally Original y titled the National Streamflow Information Program (NSIP), the USGS now designates these streamgages as FPSs.6262 Out of the 4,760 FPS locations

61 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, December 17, 2018.

62 USGS, FY2016 Budget.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 16 link to page 16 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Out of the 4,760 FPS locations identified by the USGS, 3,640470 sites (73%) were operational in 2018.63 In FY2018FY2020.63 In FY2020, the USGS

share of funding was $24.7 millionmil ion for FPSs.

The idea of a federallyfederal y sustained set of streamgages arose in the late 20th20th century when audits

revealed the number of streamgages declining after peaking in the 1970s (see decrease inin Figure 56).64 In a 1998 report to Congress, the USGS stated that the streamgage program was in decline because of an absolute loss of streamgages, especiallyespecial y those with a long record, and asserted that the loss was due to partners discontinuing funding. Partners also had developed different needs for streamflow information.65 ThePartner needs for streamflow information also had evolved.65 In 1999, the USGS proposed the creation of an entirely federallyfederal y funded NSIP to

ensure a stable "backbone"backbone network of streamgages to meet national needs.6666 The USGS used five national

national needs to determine the number and location of these streamgage sites:67

1.67 1. Meeting legal2.2. Forecasting flow for NWS and NRCS.3.3. Measuring river basin outflows to calculate regional water balances.4.4. Monitoring benchmark watersheds for long-term trends in natural flows.5.5. Measuring flow for water quality needs.

The original design included 4,300 active, previously discontinued, or proposed streamgage locations.6868 The proposed program was to be fully federallyfederal y funded, conduct intense data collection during floods and droughts, provide regional and national assessments of streamflow

characteristics, enhance information delivery, and conduct methods development and research.69

69

The SECURE Water Act of 2009 authorized the NSIP to conform to the USGS plan as reviewed by the National Research Council.7070 The law required the program to fund no fewer than 4,700 sites by FY2019. The law also directed the program to determine the relationship between long-

term streamflow dynamics and climate change, to incorporate principals of adaptive management to assess program objectives, and to integrate data collection activities of other federal agencies (i.e., NOAA'’s National Integrated Drought Information System) and appropriate state water

resource agencies.

63 When the USGS proposed FPS locations in the early 2000s, many sites were already operational. NRC, Assessing the NSIP, p. 1. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

64 For example, see Wahl, USGS Circular 1123. In 1998, the House Committee on Appropriations stated in report language accompanying H.R. 4193 from the 105th Congress: “ the Committee has noted the steady decline in the number of streamgaging stations in the past decade, while the need for streamflow data for flood forecasting and long-term water management uses continues to grow.” 65 USGS, A New Evaluation of the USGS Streamgaging Network: A Report to Congress, 1998, at https://water.usgs.gov/streamgaging/report.pdf. 66 USGS, Streamflow Information for the Next Century - A Plan for the National Streamflow Information Program of the U.S. Geological Survey, 1999, OFR 99 -456, at https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1999/ofr99456/.

67 Federal Priority Streamgages designated by specific national priorities may be visualized with an interactive map at https://water.usgs.gov/networks/fps/. 68 T he number of FPS locations changes over time based on network analyses. In 2020, 4,760 locations met the criteria for FPS designation. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

69 NRC, Assessing the NSIP, p. 2. 70 SECURE Water Act of 2009 (T itle IX, Subtitle F of the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 [P.L. 111-11]). NRC, Assessing the NSIP.

Congressional Research Service

13

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Next Generation Water Observing System In 2018, the USGS initiated a Next Generation Water Observing System (NGWOS) “to provide

high-fidelity, real-time data on water quantity, quality and use necessary to support more accurate national modern water prediction and decision support systems and rapid and informed hazards response.”71 The USGS plans to develop dense networks of streamgages and other monitoring systems in up to 10 medium-sized watersheds (each approximately 15,000 square miles), each one representative of a larger water-resource region. Existing monitoring networks, such as the

FPS, are at fixed locations to address specific critical needs, as authorized by the Secure Water Act. Within NGWOS watersheds, new and enhanced monitoring stations are to include some streamgages at additional fixed locations to fil critical gaps in the basins selected. They also are to include mobile monitoring stations, including remote sensing, which would al ow for more flexibility in gathering information to improve understanding and predictions of water availability at local, regional, and national scales.72 According to some stakeholders, the NGWOS also serves

as an innovation incubator for water-observing instrumentation and methods to improve the efficiency, accuracy, and spatial and temporal scales of data collection.73 Success of new monitoring technology in these basins may lead to their incorporation into the routine operation

of USGS monitoring networks.

If fully implemented, the NGWOS would provide quantitative information on streamflow, snowpack, loss of water to the atmosphere, soil moisture, water quality, groundwater, and water usage. The USGS contends that a suite of highly monitored watersheds, in combination with an enhanced streamgage network and other relevant data sets, can better inform complex models

(e.g., the National Water Model) and streamflow information and forecasts. To assess this approach, the USGS started a multiyear NGWOS pilot in the Delaware River Basin in FY2018. Since then, the USGS has selected two additional basins for NGWOS implementation: the Upper Colorado River Basin was selected in FY2020,74 and the Il inois River Basin was selected in FY2021.75 The USGS plans to instal new or updated streamgages and other monitoring stations

in these basins. Many of these streamgages are to be equipped with two-way communication for remote operation and troubleshooting, cel and satel ite transmission redundancy, webcams, and

water-quality sensors.

71 USGS, Next Generation Water Observing System: Delaware River Basin, 2018, at https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/next -generation-water-observing-system-delaware-river-basin. 72 T he USGS states that the Next Generation Water Observing System (NGWOS) is not a replacement for existing networks, such as the FPS; rather, the NGWOS relies and builds upon the strength of existing m onitoring networks. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program , USGS, November 30, 2020.

73 T echnologies of interest include radar and image velocimetry for remotely sensing surface-water velocities, drone-mounted ground-penetrating radar for measuring bathymetry for improving flow estimates, new sensors for monitoring continuous water-quality and suspended sediment, and others. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020. 74 USGS, Next Generation Water Observing System: Upper Colorado River Basin , 2019, at https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/next -generation-water-observing-system-upper-colorado-river?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt -science_center_objects.

75 USGS, Next Generation Water Observing System: Illinois River Basin, 2020, at https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/next -generation-water-observing-system-illinois-river-basin?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt -science_center_objects.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 19 link to page 20

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Network Funding In FY2020, congressional appropriations and nonfederal partners provided $194.9 mil ion for the USGS Streamgaging Network (Figure 7).76 The USGS share included $24.7 mil ion for FPSs and $29.4 mil ion for CMF. Other federal agencies provided $38.0 mil ion (Table 1). Nonfederal

partners, mostly affiliated with the CMF program, provided $102.8 mil ion in FY2020.

Figure 7. FY2020 Funding for the USGS Streamgaging Network

(in thousands of dol ars)

Source: CRS, with data from the USGS Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program. Notes: Other nonfederal funding includes commercial businesses, nonprofit organizations, or power companies requiring streamflow data as part of their FERC licensing process.

76 T otal funding for the USGS Streamgaging Network is determined at the end of the fiscal year after accounting for contributions from cooperative partners. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner ofresource agencies.

Network Funding

In FY2018, congressional appropriations and nonfederal partners provided $189.5 million for the USGS Streamgaging Network (Figure 6).71 The USGS share included $24.7 million for FPSs and $29.8 million for CMF. Other federal agencies provided $40.7 million (Table 1). Nonfederal partners, mostly affiliated with the CMF program, provided $94.3 million.

|

Approximate Cost of USGS Streamgages Capitol cost for equipment and installation: $25,000 - $40,000 for a standard streamgage depending on the site conditions. $35,000 - $110,000 for a supergage depending on sensors and the site conditions. $15,000 for RDGs. Annual costs for operation and maintenance: $16,500 - $30,000 for continuous streamflow measurements with a standard streamgage depending on site conditions. Costs decrease by half if measuring stream stage height only and proportionally if measuring seasonally. $25,100 and $134,000 for supergages depending on site conditions and the type and number of sensors. $3,500 per event for RDGs. |

The appropriations bill for the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies funds the USGS share of the USGS Streamgaging Network. Funding for streamgages is included in the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program under the USGS Water Resources Mission Area. The line item includes funding for the streamgage network and groundwater monitoring activities, as well as other activities. Congress provided $74.2 million in FY2018 and $82.7 million in FY2019 for the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program. While maintaining level funding for FPS and CMF streamgages in FY2019, Congress directed increased funding of $8.5 million for the deployment and operation of NextGen water observing equipment.72

The President's budget request for FY2020 proposes creating a new Water Observing Systems Program combining the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 20 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

The appropriations bil for the Interior,

Approximate Cost of

Environment, and Related Agencies funds the

USGS Streamgages

USGS share of the USGS Streamgaging Network. Funding for streamgages is included

Capital costs for equipment and instal ation:

in the Groundwater and Streamflow

$25,000 - $40,000 for a standard streamgage

Information Program under the USGS Water

depending on the site conditions.

Resources Mission Area. The line item

$35,000 - $110,000 for a supergage depending on sensors and the site conditions.

includes funding for the streamgage network and groundwater monitoring activities, as wel

$15,000 for RDGs.

as other activities.77 Congress provided $84.2

Annual costs for operation and maintenance:

mil ion in FY2020 and $100.7 mil ion in

$16,500 - $32,000 for continuous streamflow

FY2021 for the Groundwater and Streamflow

measurements with a standard streamgage depending on site conditions. Costs decrease by

Information Program.78 Congress directed $16

half if measuring stream stage height only and

mil ion of the $16.5 mil ion increase for

proportional y if measuring seasonal y.

FY2021 to the NGWOS.79 Funding for FPS

$26,000 and $135,000 for supergages depending

and cooperative streamgages remained level in

on site conditions and the type and number of

FY2021 compared with FY2020.

sensors.

Other federal agencies contribute to whole or

$4,000 per event for RDGs.

partial funding of streamgages for agency

purposesand Streamflow Information Program and elements of the National Water Quality program focused on observations of surface water and groundwater.73 The President's FY2020 budget requests $105.1 million for the proposed program, a decrease of $7.5 million compared to $112.5 million of FY2018 funding for a similar structure.74 The budget request would maintain funding for active FPS locations and provide no funding for the NextGen system. For CMF, the request proposes a decrease of $500,000 for Tribal Water, which would result in a loss of $250,000 for CMF streamgages, and a decrease of $717,000 for Urban Waters Federal Partnership, which would reduce water quality monitoring at select streamgages.75

Other federal agencies contribute to whole or partial funding of streamgages for agency purposes (Table 1). Since FY2012, funding from other federal agencies has nearly doubled from $19.9 mil ion to $38.0 mil ion$19.9 million to $40.7 million in nominal dollars. This increase may be due to meeting inflation and other streamgage cost increases;, to new needs for monitoring data with existing cooperators (e.g., USACE in the Savannah and JacksonvilleJacksonvil e Harbor expansion projects);, and to the

introduction of additional funding partners (e.g., the EPA) that are supporting new streamgages.76

80

Table 1. FY2018FY2020 Funding and Streamgages Supported by Other Federal Agencies

Funding

Agency

(millions)

Streamgages

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

$26.00

2,189

Bureau of Reclamation

$4.93

310

Department of Defense (not civil)

$1.38

75

Bureau of Land Management

$1.03

65

Department of State

$0.93

103

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

$0.73

31

77 T he President’s budget requests for FY2020 and FY2021 proposed creating a new Water Observing Systems Program combining the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program and elements of the National Water Quality program focused on observations of surface water and groundwater. Congress did not adopt this proposal in either fiscal year. USGS, Budget Justifications and Perform ance Inform ation: Fiscal Year 2020 , at https://prd-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/atoms/files/fy2020_usgs_budget_justification.pdf. USGS, Budget Justifications and Perform ance Inform ation: Fiscal Year 2021 , https://prd-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/atoms/files/fy2021-usgs-budget-justification.pdf. Explanatory statements accompanying Division D of P.L. 116-94 and Division G of P.L. 116-260.

78 Explanatory statements accompanying Division D of P.L. 116-94 and Division G of P.L. 116-260. 79 Division E of H.Rept. 116-9 accompanying P.L. 116-6. 80 T he Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is supporting ecosystem restoration initiatives in the Great Lakes, Chesapeake Bay, and the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers Delta (Bay -Delta) in California. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, February 19, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

16

link to page 22 link to page 22 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

Funding

Agency

(millions)

Streamgages

National Park Service

$0.72

39

Environmental Protection Agency

$0.66

87

Department of Energy

$0.62

39

Tennessee Val ey Authority

$0.47

33

U.S. Department of Agriculture

$0.35

21

(USDA)

Bureau of Indian Affairs

$0.13

13

Source: CRS, with data from the USGS Groundwater and Streamflow Funding and Streamgages Supported by Other Federal Agencies

|

Agency |

Funding |

Streamgages |

|

USACE |

$28,209,955 |

1,950 |

|

Reclamation |

$5,335,145 |

335 |

|

DOD (not civil) |

$1,315,357 |

83 |

|

EPA |

$1,198,073 |

97 |

|

Department of State |

$1,093,164 |

61 |

|

Bureau of Land Management |

$944,112 |

55 |

|

NPS |

$647,864 |

45 |

|

FWS |

$408,161 |

20 |

|

DOE |

$473,240 |

27 |

|

Tennessee Valley Authority |

$446,942 |

35 |

|

USDA |

$462,235 |

34 |

|

Bureau of Indian Affairs |

$123,811 |

10 |

Source: CRS, with data from USGS Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program.

Information Program. Notes: Department of State funding included 6086 streamgages for the International Joint Commission (Canadian border) and one streamgage 17 streamgages for the International Boundary and Water Commission Commission (Mexican border). USDA funding included streamgages from NRCS and the Forest Survey.

from National Resource Conservation Service and the U.S. Forest Service. FY2021 data are not yet available at the time of publication.

Nonfederal partners funded approximately half the costs of the USGS Streamgaging Network

from FY2012 to FY2018.77FY2020.81 Cooperative partners include tribal, regional, state, and local agencies related to natural resources, water management, environmental quality, transportation, and regional and city planning. Irrigation districts, riverkeeper partnerships, and utility agencies and companies also fund the program. Contributions by nongovernmental partners to streamgages are very limited (1% in FY20184.5% in FY2020) and are not eligible for cost-sharing through the USGS CMF program.78

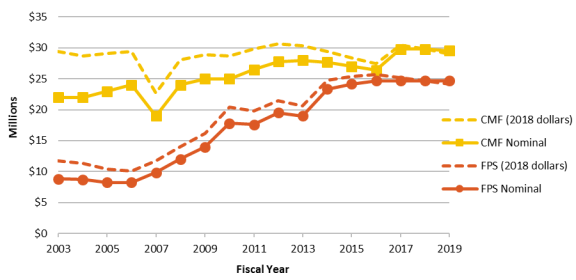

program.82 USGS Funding Trends

From FY2003 to FY2019FY2021, USGS funding for FPS streamgages increased from $11.7 million to $24.7 million (in 201812.0 mil ion to $26.2 mil ion (in 2019 dollars; Figure 7).79 However8).83 Funding for FPS remained level at $24.7 mil ion in nominal dollars from FY2016 through FY2021 (i.e., funding decreased when accounting for inflation). Accordingly, USGS funding has not met the SECURE Water Act of 2009 mandate for an entirely federally funded suite of notno fewer than 4,700 streamgage sites. In FY2018FY2020, 35% of

FPSs were funded solely by the USGS FPS program funds.8084 The USGS must relyrelies on other federal agencies or nonfederal partners to fund the rest of the FPSs: 27%in FY2020, 25% of gages were funded by a combination of FPS and non-FPS funds and 40% were funded entirely by non-FPS funds. Specific funding sources for the operation of FPS gages include FPS appropriated funds (about 42%), CMF funds (about 9%), federal agencies other than the USGS (about 23%), and

nonfederal partners (about 26%).

funded by a combination of USGS CMF and partner funds, 24% were funded by a combination of other federal agencies and nonfederal partners, and 14% were funded solely by other federal agencies (not the USGS).

USGS funding for CMF has remained relatively level, ranging from $27.5 million to $30.7 million (in 201828.0 mil ion to $31.3 mil ion (in 2019 dollars) over 15 years (Figure 8).85 For the entire USGS Streamgaging Network,

81 Nonfederal partners have provided 50%-57% of funding for the USGS Streamgaging Network over the period of FY2012 to FY2020. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwat er and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

82 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020. 83 Ibid. 84 Ibid. 85 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

17

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

dollars) over 15 years, aside from a drop in FY2007 (Figure 7).81 For the entire USGS Streamgaging Network, the nonfederal cost-share contribution has increased from nearapproximately 50% in the early 1990s to an average of about 63% in FY2018.82approximately 69% in FY2020.86 With CMF appropriations remaining level, and demand for streamgages from stakeholders rising, the USGS cost-share availablepercentage of cost-sharing has declined. Cost-share commitments for long-term streamgages are generallygeneral y are renewed at consistent percentages, but JFAs for newer streamgages may include lessa lower contribution from the USGS.83 87 Increasingly, the USGS may opt to only has opted to provide matching funds for installationonly for instal ation and operation in

the first year, with thean agreement that the partner provides full funding in subsequent years.84

|

|

Source: CRS with data from the USGS Groundwater and Streamflow Notes: Adjusted for inflation using the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Gross |

The USGS initiated the NGWOS pilot project in the Deleware River Basin with $1.5 mil ion in FY2018. Congress increased this funding to $8.5 mil ion in FY2019 for the expansion and

operation of the NGWOS in the Delaware River Basin and for modernizing the NWIS, which stores and delivers the water observations. Congress provided the USGS $8.5 mil ion for the NGWOS in FY2020, which funded further expansion in the Delaware River Basin, investments for new monitoring in the Upper Colorado River basin, and additional modernization of the USGS NWIS.89 In November 2020, the USGS stated that the agency would need additional

appropriations to initiate the third NGWOS basin, the Il inois River Basin, and additional NGWOS basins.90 Overal , the USGS stated that NGWOS basins would require $7.8 mil ion per

86 Ibid. An anomaly to the trend was in FY2007, when Congress provided less funding. 87 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, December 17, 2018. 88 Ibid. 89 Explanatory statements accompanying Division D of P.L. 116-94. 90 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

18

link to page 9 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

basin in initial capital investment for new monitoring equipment and $4.5 mil ion per basin in subsequent years for operation and maintenance. Congress provided $24.5 mil ion for the NGWOS in FY2021, directing the USGS to partner, where appropriate, with state and local

government officials and with the academic research community when executing the NGWOS.91

Issues for Congress Issues for Congress

Congress may consider funding levels and policy priorities for the USGS Streamgaging Network.

Congressional appropriations mayto the USGS affect the size of the network and the design of streamgages. Congress may provide direction regarding thealso may consider providing direction on policy priorities when consideringrelated to the

the mandates of the SECURE Water Act of 2009 and initiating the NextGen system.

implementing the NGWOS. Funding Considerations

Congress determines the amount of federal funding for the USGS Streamgaging Network and may direct its allocationdistribution to FPS, CMF, and other initiatives. The USGS and numerous stakeholders have raised funding considerations including user needs, priorities of partners,

federal coverage, infrastructure repair, disaster response, inflation, and technological advances.8592 Congress may consider whether to maintain, decrease, or expand the network, and whether to

invest in streamgage restoration and modernization.

Addressing the Size of the Network

Netw ork

The USGS uses appropriated funding to develop and maintain the USGS Streamgaging Network.

While some stakeholders advocate for maintaining or expanding the network, others may argue

that Congress should consider reducing the network in order to prioritize other activities.

Maintaining the Network

Congress may provide funding to maintain existing streamgages. The Administration continues to request funding for the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, which funds the

USGS Streamgaging Network. The FY2020FY2021 budget request states that "

one of the highest goalspriorities of the USGS is to maintain long-term stability of a '‘Federal needs backbone network'’ for long-term tracking and forecasting/modeling of streamflow conditions."86 conditions…. Specifically, consistent and systematically-collected information is paramount to meet the full gamut of Federal water priorities and responsibilities over the long term.93

Some stakeholders may advocate to maintain the current network, as it provides hydrologic information for diverse applications (see section on "“Streamgage Uses").87 The FY2020 budget requests FPS funding at FY2019 enacted levels. If inflation increases costs, level funding may not fully”).94 Congress funded FPS

91 Explanatory statements accompanying Division G of P.L. 116-260. 92 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 15, 2018. NASEM, Future Water Priorities for the Nation, Questionnaire for USGS Water Science Centers; and Coalition Supporting the USGS National Water Monitoring Network.

93 T he President’s budget requested a decrease of $1.5 million for FPS funding, specifically to reduce spending on U.S.-Canada transboundary streamgages. USGS, Budget Justifications and Perform ance Inform ation: Fiscal Year 2021, at https://prd-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/atoms/files/fy2021-usgs-budget-justification.pdf.

94 NHWC, Benefits of USGS Streamgaging Program.

Congressional Research Service

19

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network

streamgages from FY2016 through FY2021 at $24.7 mil ion annual y in nominal dollars. With inflation, level funding in nominal dollars may not be sufficient to maintain the current operations of FPSs. For example, the USGS has stated that costs for network operations have increased by 1%-3% per year, forcing the agency to rely increasingly on partners to cover cost increases or to discontinue some FPS streamgages.95 of FPSs. In addition, 7172% of the overal network, including some FPSs, areis funded by other federal and nonfederal partners, which makes those streamgages potentially vulnerable for discontinuation

potential y vulnerable to discontinuation if partner priorities change. According to the Government Accountability Office, maintaining streamgages through partners can be a challenge due to both thechal enge

due to partners’ changing priorities and financial limitations of the partners.88

.96 Reducing the Network Size

Congress may consider reducing the network, either for FPSs, cooperative streamgages, or both.

The USGS has discontinued some streamgages because of other funding priorities or because cooperators decided to no longer fund them and alternative funding was not available for the operating costs. Closures may affect individual streamgages or a collection of streamgages.89 The97 The Trump Administration requested reductions for the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program in FY2018, FY2019, FY2020, and FY2021, compared with congressional

appropriations in previous fiscal years.98 For example, in FY2021, the requested decrease included $1.5 mil ion for U.S.-Canada transboundary streamgages, $2.4 mil ion in CMF funding,

and $3.0 mil ion for the NGWOS.

Reducing the USGS Streamgaging Network could al eviate federal spending on streamgages and al ow other entities to operate streamgages tailored to their needs. On the other hand, discontinuing currently operational streamgages may result loss of data acquisition, discontinuation of long-term datasets, and decreased coverage in some basins. Some stakeholders have proposed that entities with specific needs build and operate their own streamgages separate

from the USGS network.99 Some states, such as California and Oregon, already operate their own streamgaging networks.100 In 2019, the Montana state legislature created a Stream Gage

95 USGS, Update on USGS Integrated Water Monitoring Initiatives, at the 2020 Annual Meeting for the Interstate Water Policy Council, at https://icwp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Wagner_GWSIP_USGS.pdf, and personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 30, 2020.

96 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, November 15, 2018; NASEM, Future Water Priorities for the Nation, Questionnaire for USGS Water Science Centers; and GAO, Federal Data Programs, pp. 164 -174. 97 For example, in 2017 the Missouri Department of Natural Resources decided to eliminate funding for 49 streamgages cooperatively operated with the USGS. T he USGS continued six of these streamgages with new cooperators. After record-breaking floods across the southern half of Missouri, the state decided to continue the funding. Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, March 5, 2019; Will Schmitt, “ Officials agree to fund most of Missouri’s threatened stream gauges,” Springfield News-Leader, June 13, 2017, at https://www.news-leader.com/story/news/politics/2017/06/13/officials-agree-fund-most -missouris-threatened-stream-gauges/387602001/.

98 For FY2018 through FY2021, Congress did not follow T rump Administration-requested decreases to the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, and instead increased funding compared to previous fiscal years. USGS budget request information is available at https://www.usgs.gov/about/organization/science-support/budget/budget-fiscal-year.

99 Meeting of Water Science and T echnology Board, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, DC, November 29, 2018.

100 Personal correspondence between CRS and Chad Wagner of the Groundwater and Streamflow Information Program, USGS, December 17, 2018.

Congressional Research Service

20

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Streamgaging Network