Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy

Changes from April 11, 2019 to June 13, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Brief History

- Governance

- Human Rights Issues

- Freedom of Expression

- Women's Rights

- Trafficking in Persons and Labor Issues

- Religious Freedom

- Foreign Policy

- Qatar and the Intra-GCC Dispute

- Iran

- Egypt

- Libya

- Yemen

- Syria, Iraq, and Anti-Islamic State Operations

- Lebanon

- Israeli-Palestinian Issues/Hamas

- Afghanistan/Taliban Office

- Other Qatari Relationships and Mediation Efforts

- U.S.-Qatar Defense and Security Cooperation

- Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA)

- Al Udeid Expansion/Permanent U.S. Basing in Qatar?

- U.S. Arms Sales to Qatar

- Other Defense Partnerships

- France

- Turkey

- Russia

- Counterterrorism Cooperation

- Terrorism Financing Issues

- Countering Violent Extremism

- Economic Issues

- U.S.-Qatar Economic Relations

- U.S. Assistance

Figures

Summary

The State of Qatar has employed its ample financial resources to exert regional influence separate from and independent of Saudi Arabia, the de facto leader of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Oman), an alliance of six Gulf monarchies. Qatar has intervened in several regional conflicts, including in Syria and Libya, and has engaged both Sunni Islamist and Iran-backed Shiite groups in Lebanon, Sudan, the Gaza Strip, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Qatar has maintained consistent dialogue with Iran while also supporting U.S. and GCC efforts to limit Iran's regional influence.

Qatar's independent policies, which include supporting regional Muslim Brotherhood organizations and hosting a global media network often critical of Arab leaders called Al Jazeera, have caused a backlash against Qatar by Saudi Arabia and some other GCC members. A rift within the GCC opened on June 5, 2017, when Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain, joined by Egypt and a few other governments, severed relations with Qatar and imposed limits on the entry and transit of Qatari nationals and vessels in their territories, waters, and airspace. The Trump Administration has sought, unsuccessfully to date, to mediate a resolution of the dispute. The rift has hindered U.S. efforts to hold another U.S.-GCC summit that would formalize a new "Middle East Strategic Alliance" of the United States, the GCC, and other Sunni-led countries in the region to counter Iran and other regional threats. Qatar has countered the Saudi-led pressure with new arms buys and deepening relations with Turkey and Iran.

As do the other GCC leaders, Qatar's leaders have looked to the United States to guarantee their external security since the 1980s. Since 1992, the United States and Qatar have had a formal Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) that reportedly addresses a U.S. troop presence in Qatar, consideration of U.S. arms sales to Qatar, U.S. training, and other defense cooperation. Under the DCA, Qatar hosts aboutup to 13,000 U.S. forces and the regional headquarters for U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) at various military facilities, including the large Al Udeid Air Base. U.S. forces in Qatar participate in all U.S. operations in the region. Qatar is a significant buyer of U.S.-made weaponry, including combat aircraft. In January 2018, Qatar and the United States inaugurated a "Strategic Dialogue" to strengthen the U.S.-Qatar defense partnership, which Qatar says might include permanent U.S. basing there. The second iteration of the dialogue, in January 2019, resulted in a U.S.-Qatar memorandum of understanding to expand Al Udeid Air Base to improve and expand accommodation for U.S. military personnel. Qatar signed a broad memorandum of understanding with the United States in 2017 to cooperate against international terrorism. That MOU appeared intended to counter assertions that Qatar's ties to regional Islamist movements support terrorism – apparently at least in part to counter accusations that Qatar supports terrorist groups.

The voluntary relinquishing of power in 2013 by Qatar's former Amir (ruler), Shaykh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, departed from GCC patterns of governance in which leaders generally remain in power for life. However, Qatar is the only one of the smaller GCC states that has not yet held elections for a legislative body. U.S. and international reports criticize Qatar for failing to adhere to international standards of labor rights practices, but credit it for taking steps in 2018 to improve the conditions for expatriate workers.

As are the other GCC states, Qatar is wrestling with the fluctuations in global hydrocarbons prices since 2014, now compounded by the Saudi-led embargo. Qatar is positioned to weather these headwinds because of its small population and substantial financial reserves. But, Qatar shares with virtually all the other GCC states a lack of economic diversification and reliance on revenues from sales of hydrocarbon products. On December 3, 2018, Qatar announced it would withdraw from the OPEC oil cartel in order to focus on its natural gas export sector.

Brief History

Prior to 1867, Qatar was ruled by the family of the leaders of neighboring Bahrain, the Al Khalifa. That year, an uprisinguprising in the territory led the United Kingdom, then the main Western power in the Persian Gulf region, to install a leading Qatari family, the Al Thani, to rule over what is now Qatar. The Al Thani family claims descent from the central Arabian tribe of Banu Tamim, the tribe to which Shaykh Muhammad ibn Abd Al Wahhab, the founder of Wahhabism, belonged.1 Thus, Qatar officially subscribes to Wahhabism, a conservative Islamic tradition that it shares with Saudi Arabia.

In 1916, in the aftermath of World War I and the demise of the Ottoman Empire, Qatar and Britain signed an agreement under which Qatar formally became a British protectorate. In 1971, after Britain announced it would no longer exercise responsibility for Persian Gulf security, Qatar and Bahrain considered joining with the seven emirates (principalities) that were then called the "Trucial States" to form the United Arab Emirates. However, Qatar and Bahrain decided to become independent rather than join that union. The UAE was separately formed in late 1971. Qatar adopted its first written constitution in April 1970 and became fully independent on September 1, 1971. The United States opened an embassy in Doha in 1973. The last U.S. Ambassador to Qatar, Dana Shell Smith, resigned from that post in June 2017, reportedly over disagreements with the Trump Administration. Mary Catherine Phee has been nominated as a replacement.

|

Position |

Leader |

|

Amir (ruler) and Minister of Defense |

Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani |

|

Deputy Amir and Crown Prince (heir apparent) |

Abdullah bin Hamad Al Thani |

|

Prime Minister and Minister of Interior |

Abdullah bin Nasir bin Khalifa Al Thani |

|

Deputy Prime Minister |

Ahmad bin Abdallah al-Mahmud |

|

Minister of State for Defense Affairs |

Khalid bin Muhammad Al-Attiyah |

|

Minister of Foreign Affairs |

Muhammad bin Abd al-Rahman Al Thani |

|

Minister of Finance |

Ali Sharif al-Imadi |

|

Ambassador to the United States |

Mishal bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani |

Source: Central Intelligence Agency, "Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments."

|

|

Area |

11,586 sq km (slightly smaller than Connecticut) |

|

People |

Population: 2.3 million (July 2017 estimate), of which about 90% are expatriates Religions: Muslim 68%, of which about 90% are Sunni; Christian 14%; Hindu 14%; 3% Buddhist; and 1% other. Figures include expatriates. Ethnic Groups: Arab 40%; Pakistani 18%; Indian 18%; Iranian 10%; other 14%. Figures include expatriates. Virtually all citizens are Arab. |

|

Economy |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): $341 billion (2017) on purchasing power parity (ppp) basis GDP per capita: $125,000 (2017) on ppp basis Inflation: 1% (2017) GDP Growth Rate: 2.5% (2017) Export Partners: (In descending order) Japan, South Korea, India, China, Singapore, UAE Import Partners: (In descending order) United States, China, UAE, Germany, Japan, Britain, Italy, Saudi Arabia (pre-2017 GCC rift) |

|

Oil and Gas |

Oil Exports: Slightly more than 700,000 barrels per day. Negligible amounts to the United States. Producer of condensates (light oil) vital to S. Korean petrochemical industry. Natural Gas Exports: Almost 125 billion cubic meters in 2014 |

Sources: Graphic created by CRS. Map borders and cities generated by Hannah Fischer using data from Department of State, 2013; Esri, 2013; and Google Maps, 2013. At-a-glance information from CIA, The World Factbook.

Governance

Qatar's governing structure approximates that of the other GCC states. The country is led by a hereditary Amir (literally "prince," but interpreted as "ruler"), Shaykh2 Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. He became ruler in June 2013 when his father, Amir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, relinquished power voluntarily. The Amir governs through a prime minister, who is a member of the Al Thani family, and a cabinet, several of whom are members of the Al Thani family or of prominent allied families. Amir Tamim serves concurrently as Minister of Defense, although most of the defense policy functions are performed by the Minister of State for Defense, a position with less authority than that of full minister. In November 2014, Amir Tamim appointed a younger brother, Shaykh Abdullah bin Hamad, to be deputy Amir and the heir apparent. The Prime Minister, Shaykh Abdullah bin Nasir bin Khalifa Al Thani, also serves as Interior Minister.

There is dissent within the Al Thani family—mostly from those of lineages linked to ousted former Qatari rulers—but no significant challenge to Tamim's rule is evident. There were no significant protests in Qatar during the "Arab Spring" uprising of 2011 or since. Political parties are banned, and unlike in Kuwait and Bahrain, there are no well-defined "political societies" that act as the equivalent of parties. Political disagreements in Qatar are aired mainly in private as part of a process of consensus building in which the leadership tries to balance the interests of the various families and other constituencies.3

Then-Amir Hamad put a revised constitution to a public referendum on April 29, 2003, achieving a 98% vote in favor. Nevertheless, it left in place significant limitations: for example, it affirms that Qatar is a hereditary emirate. Some Western experts also criticize Qatar's constitution for specifying Islamic law as the main source of legislation.4 The constitution stipulates that elections will be held for 30 of the 45 seats of the country's Advisory Council (Majlis Ash-Shura), a national legislative body, but elections have been repeatedly delayed. The elected Council is also to have broader powers, including the ability to remove ministers (two-thirds majority vote), to approve a national budget, and to draft and vote on proposed legislation that can become law (two-thirds majority vote and concurrence by the Amir). In 2008, it was agreed that naturalized Qataris who have been citizens for at least 10 years will be eligible to vote, and those whose fathers were born in Qatar will be eligible to run. Qatar is the only GCC state other than Saudi Arabia not to have held elections for any seats in a legislative body.

The country holds elections for a 29-seat Central Municipal Council. Elections for the fourthfifth Council (each serving a four-year term) were held on May 13, 2015in April 2019. The Central Municipal Council advises the Minister of Municipality and Urban Affairs on local public services. Voter registration and turnout—21,735 voters registered out of an estimate 150,000 eligible voters, and 15,171 of those voted—were lower than expected,5 suggesting that citizens viewed the Council as lacking influence. The State Department stated that "observers considered [the municipal council elections] free and fair."6

Human Rights Issues7

Recent State Department reports identify the most significant human rights problems in the country as limits on the ability of citizens to choose their government in free and fair elections; restrictions on freedoms of assembly and association, including prohibitions on political parties and labor unions; restrictions on the rights of expatriate workers; and criminalization of consensual same-sex sexual activity.

A nominally independent, government-funded National Human Rights Committee (NHRC) investigates allegations of human rights abuses in the country. It is under the authority of the Qatar Foundation that was founded and is still run by the Amir's mother, Shaykha Moza. The NHRC also monitors the situation of about 1,000-2,000 stateless residents ("bidoons"),8 who are able to register for public services but cannot own property or travel freely to other GCC countries. Although the constitution provides for an independent judiciary, the Amir, based on recommended selections from the Supreme Judicial Council, appoints all judges, who hold their positions at his discretion.9

Freedom of Expression

As have the other GCC states, Qatar has, since the 2011 "Arab Spring" uprisings, issued new laws that restrict freedom of expression and increase penalties for criticizing the ruling establishment. In 2014, the government approved a new cybercrimes law that provides for up to three years in prison for anyone convicted of threatening Qatar's security or of spreading "false news." A November 2015 law increased penalties for removing or expressing contempt at the national flag or the GCC flag. In July 2017, the country held a national conference on freedom of expression at which, according to the State Department, members of international human rights organizations were able to criticize the country's human rights record.10

Al Jazeera. The government owns and continues to partially fund the Al Jazeera satellite television network, which has evolved into a global media conglomerate that features debates on controversial issues, as well as criticism of some Arab leaders. The State Department quotes "some observers and former Al Jazeera employees" as alleging that the government "influences" Al Jazeera content. Some Members of Congress have asserted that Al Jazeera is an arm of the Qatar government and that its U.S. bureau should be required to register under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).

|

Qatari Leadership

Shaykh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani Shaykh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani was born on June 3, 1980. He is the fourth son of the former Amir, Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, and the ninth Al Thani ruler in Qatar. He was appointed heir apparent in August 2003 when his elder brother, Shaykh Jasim, renounced his claim, reportedly based on his father's lack of confidence in Shaykh Jasim's ability to lead. Shaykh Tamim became Amir on June 25, 2014, when Amir Hamad stepped down voluntarily to pave the way for the accession of a new generation of leadership. Amir Tamim was educated at Great Britain's Sherbourne School and graduated from its Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst in 1998, from which his father graduated in 1971. Concurrently, Amir Tamim heads the Qatari Investment Authority, which has billions of dollars of investments in Europe, including in Harrod's department store in London, the United States, and elsewhere. He is reportedly highly popular for resisting Saudi-led pressure in the intra-GCC crisis.

Shaykh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani Amir Tamim's father, Shaykh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, took power in June 1995, when his father, Amir Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani, was in Europe. In 1972, after finishing his education in Britain and assuming command of some Qatari military units, Hamad had helped his father depose his grandfather in a bloodless seizure of power while then-Amir Ahmad bin Ali Al Thani was on a hunting trip in Iran. While Shaykh Hamad is no longer Qatar's ruler, he, his wife, and several of their other children remain key figures in the ruling establishment. Qatari media refer to Shaykh Hamad as "The Father Amir" and acknowledge that he has some continuing role in many aspects of policy. His favored wife (of three), Shaykha Moza al-Misnad Al Thani, continues to chair the powerful Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development (QF). The QF runs Doha's Education City, where several Western universities have established branches and which is a large investor in the United States and Europe. One daughter (and full sister of the current Amir), Shaykha Mayassa, chairs the Qatar Museums, a major buyer of global artwork. Another daughter, Shaykha Hind, is vice chairman of the QF. Both daughters graduated from Duke University. Another relative, Hamad bin Jasim Al Thani, remains active in Qatar's investment activities and international circles. During Amir Hamad's rule, Shaykh Hamad bin Jasim was Foreign Minister, Prime Minister, and architect of Qatar's relatively independent foreign policy. Shaykh Hamad's father, former Amir Khalifa bin Hamad, died in October 2016. Sources: http://www.mofa.gov, author conversations with Qatari and U.S. officials. |

Women's Rights

According to the State Department, social and legal discrimination against women continues, despite the constitutional assertion of equality. No specific law criminalizes domestic violence, and a national housing law discriminates against women married to noncitizen men and divorced women. The laws criminalizes rape. Court testimony by women carries half the weight of that of a man. On the other hand, women in Qatar drive and own property, and constitute about 15% of business owners and more than a third of the overall workforce, including in professional positions.

Women serve in public office, such as minister of public health, chair of the Qatar Foundation, head of the General Authority for Museums, permanent representative to the United Nations, and ambassadors to Croatia and the Holy See. In November 2017, the Amir appointed four women to the national consultative council for the first time in the legislative body's history. However, most of the other small GCC states have more than one female minister.

Trafficking in Persons and Labor Issues11

The State Department's Trafficking in Persons report for 2018 upgraded Qatar's ranking to Tier 2 from Tier 2: Watch List, on the basis that the government has made significant efforts to comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking over the past year. Qatar enacted a Domestic Worker Law to better protect domestic workers and, in recent years, it also established a coordinating body to oversee and facilitate anti-trafficking initiatives and enacting a law that reforms the sponsorship system to significantly reduce vulnerability to forced labor.

But Qatar remains a destination country for men and women subjected to forced labor and, to a much lesser extent, forced prostitution. Female domestic workers are particularly vulnerable to trafficking due to their isolation in private residences and lack of protection under Qatari labor laws. In the course of the January 2018 U.S.-Qatar "Strategic Dialogue," the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding to create a framework to combat trafficking in persons.

The State Department assesses Qatar's labor rights as not adequately protecting the rights of workers to form and join independent unions, conduct legal strikes, or bargain collectively. Qatari law does not prohibit antiunion discrimination or provide for reinstatement of workers fired for union activity. The single permitted trade union, the General Union of Workers of Qatar, is assessed as "not functioning." International scrutiny of Qatar's labor practices has increased as Qatar makes preparations to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup soccer tournament; additional engineers, construction workers, and other laborers have been hired to work in Qatar. Some workers report not being paid for work and a lack of dispute resolution, causing salary delays or nonpayment.12 Some human rights groups have criticized Qatar for allowing outdoor work (primarily construction) in very hot weather.13

An investigation by German journalists found continuing violations of labor rights and poor conditions among workers preparing for the 2022 tournament in Qatar, including the deaths of over 100 expatriate workers from Nepal in 2019.14Yet, the State Department credits the country with taking steps to protect labor rights, including for expatriate workers. In December 2016, a labor reform went into effect that offers greater protections for foreign workers by changing the "kafala" system (sponsorship requirement for foreign workers) to enable employees to switch employers at the end of their labor contracts rather than having to leave Qatar when their contracts end. In 2018, the government established and is funding several housing sites to replace unsafe temporary housing for expatriate workers. The government also has stepped up arrests and prosecutions of individuals for suspected labor law violations, and has increased its cooperation with the ILOInternational Labor Organization (ILO) to take in worker complaints and better inform expatriate workers of their rights.

Religious Freedom14

15

Qatar's constitution stipulates that Islam is the state religion and Islamic law is "a main source of legislation," but Qatari laws incorporate secular legal traditions as well as Islamic law. The law recognizes only Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. The overwhelming majority (as much as 95%) of Qatari citizens are Sunni Muslims, possibly explaining why there have been no signs of sectarian schisms within the citizenry. The government permits eight registered Christian denominations to worship publicly at the Mesaymir Religious Complex (commonly referred to as "Church City"), and it has allowed the Evangelical Churches Alliance of Qatar to build a church.

Jews and adherents of unrecognized religions—such as Hindus, Buddhists, and Baha'is—are allowed to worship privately but do not have authorized facilities in which to practice their religions. Qatari officials state that they are open to considering the creation of dedicated worship spaces for Hindus, Jews, and Buddhists and that any organized, non-Muslim religious group could use the same process as Christians to apply for official registration. Members of at least one group reportedly filed for land in previous years to build their own complex but received no response from the government.

Foreign Policy

Qatar uses its financial resources to implement a foreign policy that engages a wide range of regional actors, including those that are at odds with each other. Qatari officials periodically meet with Israeli officials while at the same hosting leaders of the Palestinian militant group, Hamas. Qatar maintains consistent ties to Iran while at the same time hosting U.S. forces that contain Iran's military power. Qatar hosts an office of the Afghan Taliban movement that facilitates U.S.-Taliban talks. Its policies have enabled Qatar to mediate some regional conflicts and to obtain the freedom of captives held by regional armed groups. Yet, Qatar often backs regional actors at odds with those backed by de facto GCC leader Saudi Arabia and other GCC states, causing Saudi Arabia and its close allies in the GCC to accuse Qatar of undermining the other GCC countriescontributing to a rift within the GCC. As have some of the other GCC states, Qatar has shown an increasing willingness to use its own military forces to try to shape the outcome of regional conflicts.

Qatar and the Intra-GCC Dispute

A consistent source of friction within the GCC has been Qatar's embrace of Muslim Brotherhood movements as representing, which Qatar argues is a moderate political Islamist movement that can foster regional stability. Qatar hosts Islamists who adhere to the Brotherhood's traditions, including the aging, outspoken Egyptian cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi. In 2013-2014, differences over this and other issues widened to the point where Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors from Doha in March 2014, accusing Qatar of supporting "terrorism."1516 The Ambassadors returned in November 2014 in exchange for a reported pledge by Qatar to fully implement a November 2013 "Riyadh Agreement" that committed Qatar to noninterference in the affairs of other GCC states and to refrain from supporting Muslim Brotherhood-linked organizations.1617

These differences erupted again following the May 20-22, 2017, visit of President Donald Trump to Saudi Arabia, during which expressed substantial support for Saudi leaders. On June 5, 2017, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Bahrain, joined by Egypt and a few other Muslim countries, severed diplomatic relations with Qatar, expelled Qatar's diplomats, recalled their ambassadors, and imposed limits on the entry and transit of Qatari nationals and vessels in their territories, waters, and airspace. They also accused Qatar of supporting terrorist groups and Iran.

On June 22, 2017, the Saudi-led group presented Qatar with 13 demands,1718 including closing Al Jazeera, severing relations with the Muslim Brotherhood, scaling back relations with Iran, closing a Turkish military base in Qatar, and paying reparations for its actions. Amir Tamim expressed openness to negotiations but said it would not "surrender" its sovereignty. The Saudi-led group subsequently reframed its demands as six "principles," among which were for Qatar to "combat extremism and terrorism" and prevent their financing, suspend "all acts of provocation," fully comply with the commitments Qatar made in 2013 and 2014 (see above), and refrain "from interfering in the internal affairs of states."18

President Trump initially responded to the crisis by echoing the Saudi-led criticism of Qatar's policies, but later sought to settle the rift.1920 Then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, working with Kuwait, took the lead within the Trump Administration to mediating the dispute, including by conducting "shuttle diplomacy" in the region during July 10-13, 2017. President Trump facilitated a phone call between Amir Tamim and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman on September 9, 2017,2021 but the direct dialogue faltered over a dispute about which leader had initiated the talks. No subsequent meetings between President Trump and the leaders of the parties to the dispute, or subsequent actions or proposals, have produced any significant progress toward resolution of the rift. Secretary of State Pompeo's visit to the Gulf states in January 2019 produced no evident movement, and the U.S. envoy who was assigned to work on this issue, General Anthony Zinni (retired), resigned as envoy in early in August 2017, General (retired) Anthony Zinni, resigned in January 2019.

Yet, there are signs that Saudi Arabia and the UAE, facing criticism over the Kashoggi issue and their involvement in Yemen, might want to de-escalate might welcome resolution of the dispute. Qatari forces and commanders have been participating in GCC "Gulf Shield" military exercises and command meetings in Saudi Arabia and other GCC states. Amir Tamim was invited by Saudi Arabia to the annual GCC summit in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, during December 7-9, 2018, but he did not attend.

Qatar asserts that the blockading countries are seeking to change Qatar's leadership and might take military action to force Qatar to accept their demands. In December 2017, Saudi Arabia "permanently" closed its Salwa border crossing into Qatar, and some press reports say that Saudi Arabia is contemplating building a canal that would physically separate its territory from that of Qatar. Qatari officials assert that the country's ample wealth is enabling it to limit the economic effects of the Saudi-led move, but that the blockade has separated families and caused other social disruptions. Qataris reportedly have rallied around their leadership to resist Saudi-led demands.Qatar's Prime Minister attended the GCC and Arab League summit meetings in Saudi Arabia on May 30, which were arranged to discuss U.S.-Iran and Iran-GCC tensions and other regional issues.22

The dispute has to date thwarted U.S. efforts to assemble the a new "Middle East Strategic Alliance" to counter Iran and regional terrorist groups. This alliance – to consist of the United States, the GCC countries, and other Sunni-led states, is reportedly to be formally unveiled at U.S.-GCC summit that has been repeatedly postponed since early 2018 and is not scheduled. The MESA has also been hampered by the global criticism of Saudi de facto leader Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman for his possible involvement in the October 2018 killing of U.S.-based Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, and by Egypt's April 2019 decision to refrain from joining the Alliance.

Qatar's disputes with other GCC countries have come despite the resolution in 2011 of a long-standing territorial dispute between Qatar and Bahrain, dating back to the 18th century, when the ruling families of both countries controlled parts of the Arabian peninsula. Qatar and Bahrain referred the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 1991 after clashes in 1986 in which Qatar landed military personnel on a disputed man-made reef (Fasht al-Dibal). In March 2001, the ICJ sided with Bahrain on the central dispute over the Hawar Islands, but with Qatar on ownership of the Fasht al-Dibal reef and the town of Zubara on the Qatari mainland, where some members of the ruling Al Khalifa family of Bahrain are buried. Two smaller islands, Janan and Hadd Janan, were awarded to Qatar. Qatar accepted the ruling as binding.

Iran

Even though the Saudi-led bloc asserts that Qatar had close's relations with Iran are close, Qatar has long helped counter Iran strategically. Qatar enforced international sanctions against Iran during 2010-2016, and no Qatar-based entity has been designated by the United States as an Iran sanctions violator. Amir Tamim attended both U.S.-GCC summits (May 2015 at Camp David and April 2016 in Saudi Arabia) that addressed GCC concerns about the July 2015 U.S.-led multilateral agreement on Iran's nuclear program (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA).21 Qatar withdrew its Ambassador from Tehran in January 2016 in solidarity with Saudi Arabia over the Saudi execution of a dissident Shiite cleric, and Qatar joined the February 2016 GCC declaration that Lebanese Hezbollah is a terrorist group.

Yet Qatari leaders have always argued that dialogue with Iran is key to reducing regional tensions. Qatar and Iran have shared a large natural gas field in the Persian Gulf without incident, although some Iranian officials have occasionally accused Qatar of cheating on the arrangement.2223 In February 2010, as Crown Prince, Shaykh Tamim, visited Iran for talks with Iranian leaders, and as Amir, he has maintained direct contact with Iran's President Hassan Rouhani.2324

Apparently perceiving that the June 2017 intra-GCC rift provided an opportunity to drive a wedge within the GCC, Iran has supported Qatar in the dispute and has exported additional foodstuffs to Qatar to help it compensate for the cutoff of Saudi food exports. It has permitted Qatar Airways to overfly its airspace in light of the Saudi, UAE, and Bahraini denial of their airspace to that carrier. In August 2017, Qatar formally restored full diplomatic relations with Iran. Qatar did not directly support the May 8, 2018, U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, instead issuing a statement hoping that efforts to "denuclearize" the region will not lead to "escalation."24

Saudi official statements also cited Qatar's alleged support for pro-Iranian dissidents in Bahrain as part of the justification for isolating Qatar in June 2017. Contributing to that Saudi perception was Qatar's brokering in 2008 of the "Doha Agreement" to resolve a political crisis in Lebanon that led to clashes between Lebanon government forces and Hezbollah. Qatar's role as a mediator stemmed, at least in part, from Qatar's role in helping reconstruct Lebanon after the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war, and from then-Amir Hamad's postwar visit to Hezbollah strongholds in Lebanon. Further fueling Saudi and UAE suspicions was a 2017 Qatari payment to certain Iraqi Shiite militia factions of several hundred million dollars to release Qatari citizens, including royal family members, who were kidnapped in 2016 while falcon hunting in southern Iraq.25

Egypt

In Egypt, after the fall of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in 2011, a Muslim Brotherhood-linked figure, Muhammad Morsi, won presidential elections in 2012. Qatar contributed about $5 billion in aid,2629 aggravating a split between Qatar and the other GCC states over the Muslim Brotherhood. Saudi Arabia and the UAE backed Morsi's ouster by Egypt's military in 2013. Because of its support for Morsi, Qatar's relations with former military leader and now President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi have been strained, and Egypt joined the 2017 Saudi-led move against Qatar.

Libya

In Libya, Qatar joined the United States and several GCC and other partner countries in air operations to help oust Qadhafi in 2011. Subsequently, however, Qatar has supported Muslim Brotherhood-linked factions in Libya opposed by the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.27 This difference in approaches in Libya among the GCC states contributed to the intra-GCC rift. As of April 2019, it appears that the UAE and Egypt-backedthat support the U.N.-backed government in Tripoli. The UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia support ex-military commander Khalifa Hifter, who has consolidated his control of much of Libya over the past four years, is poised to reunite the country by force and is attempting to seize control of Tripoli too.30 This difference in approaches in Libya among the GCC states contributed to the intra-GCC rift.

Yemen

In 2015, Qatar joined the Saudi-led military coalition that is battling Iran-backed Zaidi Shiite Houthi rebels in Yemen, including conducting air strikes against Houthi and allied positions. This was a departure from Qatar's 2006-2007 failed efforts to mediate between the Houthis and the government of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who left office in 2012 following an "Arab Spring"-related uprising in Yemen. In September 2015, Qatar deployed about 1,000 military personnel, along with armor, to Yemen. Four Qatar soldiers were killed fighting there.The mission of the contingent was to guard the Saudi border from incursion attempts by the Houthis and their allies. Four Qatar soldiers were killed fighting there. The Qatari Air Force did not participate in the Saudi-led effort by flying air strikes against Houthi positions, according to the Qatar Embassy in Washington D.C.31 As a result of the intra-GCC rift, in mid-2017 Qatar withdrew from the Saudi-led military effort in Yemen.

Syria, Iraq, and Anti-Islamic State Operations

In Syria, Qatar provided funds and weaponry to rebels fighting the regime of President Bashar Al Asad,2832 including those, such as Ahrar Al Sham, that competed with and sometimes fought anti-Asad factions supported by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Qatar also built ties to Jabhat al Nusra (JAN), an Al Qaeda affiliate that was designated by the United States as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO),2933 although Qatari officials assert that their intent was to induce the group to sever its ties to Al Qaeda, which it formally did in July 2016. Qatari mediation also obtained the release of Lebanese and Western prisoners captured by that group. However, Asad regime recent gains in Syria likely render Qatar's involvement moot. Qatar has not, to date, followed Kuwait or Bahrain in reopening its embassy in Damascus; its Foreign Minister stated in January 2019 that Qatar saw "no reason" to do so.3034 According to the State Department, Qatar has allowed 20,000 Syrians fleeing the civil war there to retain residency in Qatar.

Qatar is a member of the U.S.-led coalition combating the Islamic State. In 2014, Qatar flew some airstrikes in Syria against Islamic State positions. However, after several weeks, the coalition ceased identifying Qatar as a participant in coalition strikes inside Syria. Neither Qatar nor any other GCC state participated in coalition air operations against the Islamic State inside Iraq. In April 2017, Qatar reportedly paid ransom to obtain the release of 26 Qatari ruling family members abducted Iraqi Shia militiamen while on a hunting trip in southern Iraq in 2015. The Iraqi government said in June 2017 that it, not Shia fighters, received the ransom.

Lebanon

Qatar has sought to exert some influence in Lebanon, possibly as a counterweight to that exerted by Saudi Arabia. In January 2019, Amir Tamim was one of the few regional leaders to attend an Arab League summit held in Beirut. In late January 2019, Qatar announced a $500 million investment in Lebanon government bonds to support that country's ailing economy.31

Israeli-Palestinian Issues/Hamas

Qatar has attempted to play a role in Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations by engaging all parties. In directly engaging Israel, in 1996, then-Amir Hamad hosted a visit by then-Prime Minister of Israel Shimon Peres and allowed Israel to open a formal trade office in Doha—going beyond the GCC's dropping in 1998 of the secondary Arab League boycott of Israel. In April 2008, then-Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni attended the government-sponsored Doha Forum and met with Amir Hamad.3236 Qatar ordered the Israeli offices in Doha closed in January 2009 at the height of an Israel-Hamas conflict and the offices have not formally reopened. Still, small levels of direct Israel-Qatar trade reportedly continue; Israeli exports to Qatar consist mostly of machinery and technology, and imports from Qatar are primarily plastics.3337 Amir Tamim regularly accuses Israel of abuses against the Palestinians and expresses consistent support for Palestinian efforts for full United Nations membership and recognition, while at the same time backing negotiations between the Palestinians and Israel.3438

Qatar has also engaged the Islamist group Hamas, a Muslim Brotherhood offshoot that has exercised de facto control of the Gaza Strip since 2007. Qatari officials assert that their engagement with Hamas can help broker reconciliation between Hamas and the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority (PA). U.S. officials have told Members of Congress that Qatar's leverage over Hamas can be helpful to reducing conflict between Hamas and Israel and that Qatar has pledged that none of its assistance to the Palestinians goes to Hamas.3539 Qatar reportedly asked former Hamas political bureau chief Khalid Meshal to leave Qatar after the intra-GCC rift erupted, apparently to accommodate the blockading states. Qatar's critics assert that Hamas leaders are too often featured on Al Jazeera and that Qatar's relations with Hamas constitute support for a terrorist organization. In the 115th Congress, the Palestinian International Terrorism Support Act of 2017 (H.R. 2712), which was ordered to be reported to the full House on November 15, 2017, appeared directed at Qatar by sanctioning foreign governments determined to be providing financial or other material support to Hamas or its leaders.

As have the other Gulf states, Qatar has sought to compensate for a curtailment of U.S. contributions to the U.N. Relief Works Agency (UNRWA). In April 2018, Qatar donated $50 million to that agency. In December 2018, Qatar reached a two-year agreement with UNRWA to donate to that agency's programs in education and health care.

Afghanistan/Taliban Office

Qatari forces did not join any U.S.-led operations inside Afghanistan, but its facilities and forces support U.S. operations there, and Qatar has brokered talks between the United States and Taliban representatives. Unlike Saudi Arabia and UAE, Qatar did not recognize the Taliban as the legitimate government of Kabul when the movement ruled during 1996-2001. In June 2013, the Taliban opened a representative office in Qatar, but it violated U.S.-Qatar-Taliban understandings by raising a flag of the former Taliban regime on the building and Qatar, at U.S. request, immediately closed the office. Taliban officials remained in Qatar, and revived U.S.-Taliban talks led to the May 31, 2014, exchange of captured U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl for five Taliban figures held by the United States at the prison facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The five were banned from traveling outside Qatar until there is an agreed solution that would ensure that they could not rejoin the Taliban insurgency. In November 2018, the five joined the Taliban representative office in Doha.

Qatar permitted the Taliban office in Qatar to formally reopen in 2015.36 Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia Alice Wells met with Taliban figures from the office in Doha in July 2018 for discussions about a future peace settlement in Afghanistan.3740 Since mid-2018, furtherU.S.-Taliban talks, with increasing levels of intensity, have taken place in Doha between Taliban negotiators and the U.S. special envoy for Afghanistan, Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad.

Qatar might also have some contacts with the Haqqani Network, a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) that is allied with the Taliban. In January 2016, Qatari mediation reportedly caused the Haqqani Network to release a Canadian hostage, Colin Rutherford.38 The mediation did not, as Qatar had hoped, lead to the freedom of the Coleman family, also held by that group, who were rescued from the group by a U.S. and Pakistani operation in October 2016.

In January 2018, Qatar's air force completed the first two flights of its C-17 (Globemaster) cargo aircraft to Afghanistan and back. According to then-Defense Secretary Mattis, the flights provided logistical support to the NATO "counterterrorism" campaign there.

Other Qatari Relationships and Mediation Efforts39

42

Somewhat outside the traditional Middle East:

- Qatar has played an active role in mediating conflict over Sudan's Darfur region. In 2010, Qatar, including through grants and promises of investment, helped broker a series of agreements, collectively known as the Doha Agreements, between the government and various rebel factions. In March 2018, Qatar and Sudan signed an agreement to jointly invest $4 billion to develop the Red Sea port of Suakin off Sudan's coast.

- Qatar has forged relationships with several countries in Central Asia

, possibly in an effort to shape energy routes in the region.40.43 Amir Tamim has exchanged leadership visits with the President of Turkmenistan, Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov in 2016 and 2017. The two countries are major world gas suppliers. The leader of Tajikistan, Imamali Rahmonov, visited Doha in February 2017 to reportedly discuss Qatari investment and other joint projects. Qatar funded a large portion of a $100 million mosque in Dushanbe, which purports to be the largest mosque in Central Asia.

U.S.-Qatar Defense and Security Cooperation

U.S.-Qatar defense and security relations are long-standing and extensive—a characterization emphasized by senior U.S. officials in the course of the two U.S.-Qatar "Strategic Dialogue" sessions—in Washington, DC, in January 2018, and in Doha in January 2019. Senior U.S. officials have praised Qatar as "a longtime friend and military partner for peace and stability in the Middle East and a supporter of NATO's mission in Afghanistan."4144

The U.S-Qatar defense relationship emerged during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war. The six Gulf monarchies formed the GCC in late 1981 and collectively backed Iraq against the threat posed by Iran in that war, despite their political and ideological differences with Iraq's Saddam Hussein. In the latter stages of that war, Iran attacked international shipping in the Gulf and some Gulf state oil loading facilities, but none in Qatar.

After Iraq invaded GCC member Kuwait in August 1990, the GCC participated in the U.S.-led military coalition that expelled Iraq from Kuwait in February 1991. In January 1991, Qatari armored forces helped coalition troops defeat an Iraqi attack on the Saudi town of Khafji. The Qatari participation in that war ended U.S.-Qatar strains over Qatar's illicit procurement in the late 1980s of U.S.-made "Stinger" shoulder-held antiaircraft missiles.4245 U.S.-Qatar defense relations subsequently deepened and the two countries signed a formal defense cooperation agreement (DCA). U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Commander General Joseph Votel testified on February 27, 2018, that U.S. operations have not been affected by the intra-GCC rift.

Qatar, one of the wealthiest states in the world on a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) basis, receives virtually no U.S. military assistance. At times, small amounts of U.S. aid have been provided to help Qatar develop capabilities to prevent smuggling and the movement of terrorists or proliferation-related gear into Qatar or around its waterways.

Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA)

The United States and Qatar signed a formal defense cooperation agreement (DCA) on June 23, 1992. The DCA was renewed for 10 years, reportedly with some modifications, in December 2013. The text of the pact is classified, but it reportedly addresses U.S. military access to Qatari military facilities, prepositioning of U.S. armor and other military equipment, and U.S. training of Qatar's military forces.4346

Up to 13,000 U.S. troops are deployed at the various facilities in Qatar. Most are U.S. Air Force personnel based at the large Al Udeid air base southwest of Doha, working as part of the Coalition Forward Air Component Command (CFACC).4447 The U.S. personnel deployed to Qatar participate in U.S. operations such as Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) against the Islamic State organization and Operation Freedom's Sentinel in Afghanistan, and they provide a substantial capability against Iran.

The U.S. Army component of U.S. Central Command prepositions armor (enough to outfit one brigade) at Camp As Sayliyah outside Doha.4548 U.S. armor stationed in Qatar was deployed in Operation Iraqi Freedom that removed Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq in 2003.

The DCA also reportedly addresses U.S. training of Qatar's military. Qatar's force of about 12,000 is the smallest in the region except for Bahrain. Of that force, about 8,500 are ground forces, 1,800 are naval forces, and 1,500 are air forces. A 2014 law mandates four months (three months for students) of military training for males between the ages of 18 and 35, with a reserve commitment of 10 years (up to age 40). The-CENTCOM commander General Votel's February 2018 testimony, referenced above, stated that Qatar is seeking to expand its military both in size and capacity.

Al Udeid Expansion/Permanent U.S. Basing in Qatar?46

49

Since 2002, Qatar has contributed over $8 billion to support U.S. and coalition operations at Al Udeid. The air field, which also hosts the forward headquarters for CENTCOM, has been steadily expanded and enhanced not only with Qatari funding but also about $450 million in U.S. military construction funding since 2003.4750 In March 2018, the State Department approved the sale to Qatar of equipment, with an estimated value of about $200 million, to upgrade the Air Operation Center at Al Udeid.

The January 2018 Strategic Dialogue resulted in a number of U.S.-Qatar announcements of expanded defense and security cooperation, including Qatari offers to fund capital expenditures that offer the possibility of an "enduring" U.S. military presence in Qatar and to discuss the possibility of "permanent [U.S.] basing" there. To enable an enduring U.S. presence, Qatar is expanding and enhance Al Udeid over the next two decades—an effort that would facilitate an enduring U.S. presence there. On July 24, 2018, the U.S. and Qatari military attended a groundbreaking ceremony for the Al Udeid expansion, which will include over 200 housing units for families of officers and expansion of the base's ramps and cargo facilities. On January 24, 2019, in the course of the second U.S.-Qatar Strategic Dialogue, the Qatar Ministry of Defense and the U.S. Department of Defense signed a memorandum of understanding that DOD referred to as a "positive step towards the eventual formalization of Qatar's commitment to support sustainment costs and future infrastructure costs at [Al Udeid Air Base]."4851 Qatar has also extended the Hamad Port to be able to accommodate U.S. Navy operations were there a U.S. decision to base such operations in Qatar.4952

U.S. Arms Sales to Qatar

Qatar's forces continue to field mostly French-made equipment, such as the AMX-30 main battle tank, but Qatar is increasingly shifting its weaponry mix to U.S.-made equipment.5053 According to General Votel's February 27, 2018, testimony, Qatar is currently the second-largest U.S. Foreign Military Sales (FMS) customer, with $25 billion in new FMS cases. And, Qatar is "on track" to surpass $40 billion in the next five years with additional FMS purchases. The joint statement of the U.S.-Qatar Strategic Dialogue in January 2018 said that Qatari FMS purchases had resulted in over 110,000 American jobs and the sustainment of critical U.S. military capabilities.

- Tanks. Qatar's 30 main battle tanks are French-made AMX-30s. In 2015, Germany exported several "Leopard 2" tanks to Qatar. Qatar has not purchased U.S.-made tanks, to date.

- Combat Aircraft. Qatar currently has only 18 combat aircraft, of which 12 are French-made Mirage 2000s. To redress that deficiency, in 2013 Qatar

submitted a letter of request to purchaserequested to buy 72 U.S.-made F-15s. Aftera long delay reportedly linked toevaluating the potential sale against the U.S. commitment to Israel's "Qualitative Military Edge" (QME), on November 17, 2016, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) notified Congress of the potential sale, which has an estimated value of $21 billion.51 The FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (Section 1278 of P.L. 114-92) required a DoD briefing for Congress on the sale, including its effect on Israel's QME.54 On June 14, 2017, the United States and Qatar signed an agreement for a reported 36 of the F-15 fighters, which predated(and therefore were not covered by)then-Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Senator Bob Corker's June 26, 2017 announcement that he would not provide informal concurrence to arms sales to the GCC countries until the intra-GCC rift was resolved. Thatblankethold was dropped on February 8, 2018. In December 2017, the Defense Department announced that Qatar would buy the secondgrouptranche of 36 F-15s under the sale agreement. Deliveries of all aircraft are to be completed by the end of 2022. Qatar signed a $7 billion agreement in May 2015 to purchase 24 French-made Rafale aircraft,5255 and, in September 2017, a "Statement of Intent" with Britain to purchase 24 Typhoon combat aircraft. - Dassault began delivering on the Rafale order in February 2019.

Attack Helicopters. In 2012, the United States sold Qatar AH-64 Apache attack helicopters and related equipment; UH-60 M Blackhawk helicopters; and MH-60 Seahawk helicopters. The total potential value of the sales was estimated at about $6.6 billion

, of which about half consisted of the Apache sale. On April 9, 2018, DSCA announced that the State Department had approved a sale to Qatar of 5,000 Advanced Precision Kill Weapons Systems II Guidance Sections for use onits Apache fleetthe Apaches, with an estimatedsale value of $300 million. Short-Range Missile and Rocket Systems.Qatar is not known to have any extended-range missiles, but various suppliers have provided the country with short-range systems that can be used primarily invalue of $300 million. On May 9, 2019, DSCA notified Congress of a possible sale of another 24 AH-64E Apaches and related munitions and night vision gear. The justification is to help Qatar meet its requirements for close air support, armed reconnaissance, and anti-tank warfare missions, in part to help defend Qatar's oil and gas infrastructure platforms. The estimated cost of the potential sale is $3 billion. S.J.Res. 26 was introduced on May 14, 2019, to prohibit the sale. On June 12, the Administration issued a statement strongly opposing S.J.Res. 26 and stating that if it is adopted, the President's advisers would recommend a veto. Short-Range Missile and Rocket Systems. Various suppliers have provided the country with short-range missile and rocket systems suited primarily for ground operations. During 2012-2013, the United States sold Qatar Hellfire air-to-ground missiles, Javelin guided missiles, the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS), the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), and the M31A1 Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS). The total potential value of the sales was estimated at about $665 million. On April 22, 2016,the Defense Security Cooperation AgencyDSCA notified to Congress a potential sale to Qatar of 252 RIM-116C Rolling Airframe Tactical Missiles and 2 RIM 116C-2 Rolling Airframe Telemetry Missiles, plus associated equipment and support, with an estimated sale value of $260 million.5356 On May 26, 2016, DSCA notified to Congress an additional sale of 10 Javelin launch units and 50 Javelin missiles, with an estimated value of $20 million.5457 On November 27, 2018, DSCA notified Congress of a State Department approval of a commercial sale by Raytheon of 40 National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NADSAMS) at an estimated value of $215 million.- Ballistic Missiles. At its national day parade in Doha in

mid-December 2017, the Qatari military displayed its newly purchased SY 400-BP-12A ballistic missile, which has a 120-mile range and is considered suited to a surface attack mission. The display was widely viewed as an effort to demonstrate to the Saudi-led bloc Qatar's capabilities to resist concerted pressure.5558 - Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Systems. Qatar has purchased various U.S.-made BMD systems, consistent with U.S. efforts to promote a coordinated Gulf missile defense capability against Iran's missile arsenal. In 2012, the United States sold Qatar Patriot Configuration 3 (PAC-3, made by Raytheon) fire units and missiles at an estimated value of nearly $10 billion. Also that year, the United States agreed to sell Qatar the Terminal High Altitude Area Air Defense (THAAD), the most sophisticated ground-based missile defense system the United States has made available for sale.

5659 However, because of Qatar's budget difficulties and operational concerns, the THAAD sale has not been finalized.5760 In February 2017, Raytheon concluded an agreement to sell Qatar an early warning radar system to improve the capabilities of its existing missile defense systems, with an estimated value of $1.1 billion. In December 2017, the Defense Department awarded Raytheon a $150 million contract to provide Qatar with services and support for its PAC-3 system. - Naval Vessels. In August 2016, DSCA transmitted a proposed sale to Qatar of an unspecified number of U.S.-made Mk-V fast patrol boats, along with other equipment, with a total estimated value of about $124 million. In August 2017, Qatar finalized a purchase from Italy of four multirole corvette ships, two fast patrol missile ships, and an amphibious logistics ship, with an estimated value of over $5 billion.

5861

Other Defense Partnerships

Qatar has also developed relations with NATO under the "Istanbul Cooperation Initiative" (ICI). Qatar's Ambassador to Belgium serves as the interlocutor with NATO, the headquarters of which is based near Brussels. In June 2018, Qatar's Defense Minister said that his country's long-term strategic "ambition" is to join NATO.5962

France

As noted above, Qatar has historically bought most of its major combat systems from France. On March 28, 2019, French Prime Minister Edouard Phillipe visited Doha and signed with Qatar's Defense and Interior Minister five agreements to boost ties. The agreements focused on defense information exchange, cooperation to combat cybercrime, and culture and education agreements.6063

Turkey

Qatar's defense relationship with Turkey has become an element in Qatar's efforts to resist the Saudi-led pressure in the intra-GCC crisis. In 2014, Qatar allowed Turkey—a country that, like Qatar, often supports Muslim Brotherhood—to open a military base (Tariq bin Ziyad base) in Qatar,6164 an initiative that might have contributed to Turkey's support for Qatar in the June 2017 intra-GCC rift. One of the "13 demands" of the Saudi-led bloc has been that Qatar close the Turkish base in Qatar—a demand Qatari officials say will not be met. Turkey has demonstrated its support for Qatar by sending additional troops there and conducting joint exercises in August 2017 and by increasing food exports to replace those previously provided by Saudi Arabia. Turkey further added to its Qatar troop contingent in December 2017.

Russia

Qatar has broadened its relationship with Russia since early 2016 in conjunction with efforts to resolve the conflict in Syria and in recognition of Russia's heightened role in the region. One of Qatar's sovereign wealth funds has increased its investments in Russia, particularly in its large Rosneft energy firm. Amir Tamim has made several visits to Russia, the latest of which was in March 2018. During the visit, it was announced that Qatar Airways would buy a 25% stake in the Vnukovo International Airport, one of Moscow's airports.

Qatar is also reportedly considering buying the S-400 sophisticated air defense system. Qatar-Russia discussions about the purchase have apparently caused a degree of alarm among the Saudi-led states, with Saudi Arabia going so far as to threaten military action against Qatar if it buys the system. Saudi officials also reportedly asked French President Emmanuel Macron to persuade Qatar not to buy the weapon.62 Were Qatar to purchase the S-400, it might be subject to U.S. sanctions underHowever, U.S. opposition and the potential for U.S. sanctions for the sale has contributed to Qatar's lack of movement to complete the purchase. Section 231 of the Countering America's Adversaries through Sanctions Act (P.L. 115-44). That section sanctions persons or entities that conduct transactions with Russia's defense or intelligence sector. ItThe section mandates the imposition of several sanctions that might include restrictions on certain exports to Qatar, restrictions on Qatari banking activities in the United States, restrictions on Qatari acquisition of property in the United States, and a ban on U.S. investments in any Qatari sovereign debt.

Counterterrorism Cooperation63

66

U.S.-Qatar's cooperation against groups that both countries agree are terrorist groups, such as the Islamic State organization, is extensive. However, some groups that the United States considers as terrorist organizations, such as Hamas, are considered by Qatar to be Arab movements pursuing legitimate goals. Perhaps in part as a means to attract U.S. support in the context of the intra-GCC rift, on July 10, 2017, Qatar's foreign minister and then-Secretary Tillerson signed in Doha a Memorandum of Understanding on broad U.S.-Qatar counterterrorism cooperation, including but going beyond just combatting terrorism financing.6467 The United States and Qatar held a Counterterrorism Dialogue on November 8, 2017, in which they reaffirmed progress on implementing the MoU. The joint statement of the January 2018 Strategic Dialogue noted "positive progress" under the July 2017 MoU, and thanked Qatar for its action to counter terrorism. The statement also noted the recent conclusion of a memorandum of understanding between the U.S. Attorney General and his Qatari counterpart on the fight against terrorism and its financing and combating cybercrime.

In an effort to implement the U.S.-Qatar MoU, and perhaps also as a gesture to the blockading states, on March 22, 2018, the Qatar Ministry of Interior issued list of 19 individuals and eight entities that it considers as "terrorists." The list includes 10 persons who are also are also named as terrorists by the blockading GCC states. On April 2-5, 2018, Qatar held a conference attended by international experts and security professionals from 42 countries.

Qatar participates in the State Department's Antiterrorism Assistance (ATA) program to boost domestic security capabilities, and it has continued to participate in and host Global Counterterrorism Forum events. Under the ATA program, participating countries are provided with U.S. training and advice on equipment and techniques to prevent terrorists from entering or moving across their borders. However, Qatari agencies such as the State Security Bureau and the Ministry of Interior have limited manpower and are reliant on nationals from third countries to fill law enforcement positions—a limitation Qatar has tried to address by employing U.S. and other Western-supplied high technology.6568

In the past, at least one high-ranking Qatari official provided support to Al Qaeda figures residing in or transiting Qatar, including suspected September 11, 2001, attacks mastermind Khalid Shaykh Mohammad.6669 None of the September 11 hijackers was a Qatari national.

Terrorism Financing Issues

U.S. officials have stated that Qatar is taking steps to prevent terrorism financing and the movement of suspected terrorists into or through Qatar. The country is a member of the Middle East North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENAFATF), a regional financial action task force that coordinates efforts combatting money laundering and terrorism financing. In 2014, the Amir approved Law Number 14, the "Cybercrime Prevention Law," which criminalized terrorism-linked cyber offenses, and clarified that it is illegal to use an information network to contact a terrorist organization or raise funds for terrorist groups, or to promote the ideology of terrorist organizations. In 2017, the country passed updated terrorism financing legislation.

In February 2017, Qatar hosted a meeting of the "Egmont Group" global working group consisting of 152 country Financial Intelligence Units. Qatar is also a member of the Terrorist Financing Targeting Center (TFTC), a U.S.-GCC initiative announced during President Trump's May 2017 visit to Saudi Arabia. In October 2017, and despite the intra-GCC rift, Qatar joined the United States and other TFTC countries in designating terrorists affiliated with Al Qaeda and ISIS. The State Department's 2017 report on international terrorism says that, in 2017, Qatar took sweeping measures to monitor and restrict the overseas activities of Qatari charities.

According to the State Department's report on international terrorism for 2015, entities and individuals within Qatar continue to serve as a source of financial support for terrorist and violent extremist groups, particularly regional Al Qa'ida affiliates such as the Nusrah Front."6770 The State Department report for 2017 stated: "While the Government of Qatar has made progress on countering the financing of terrorism, terrorist financiers within the country are still able to exploit Qatar's informal financial system." The United States has imposed sanctions on several persons living in Qatar, including Qatari nationals, for allegedly raising funds or making donations to both Al Qaeda and the Islamic State.6871

Countering Violent Extremism

Qatar has hosted workshops on developing plans to counter violent extremism and has participated in similar sessions hosted by the UAE's Hedayat Center that focuses on that issue. Also in 2015, Qatar pledged funding to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to help address violent extremism and radicalization among youth and vulnerable populations. However, some experts have noted that the government has violated a pledge to the United States not to allow Qatari preachers to conduct what some consider religious incitement in mosques in Education City, where several U.S. universities have branches.69 Education City was established by the Qatar Foundation, which is at the core of Qatar's strategy to counter violent extremism through investment in educationStill, reports persist of Qatari clerics giving sharply anti-Western sermons in mosques and of Qatari personalities appearing to support regional movements that use violence in appearances on Al Jazeera.

Economic Issues

Even before the June 2017 intra-GCC rift, Qatar had been wrestling with the economic effects of the fall in world energy prices since mid-2014—a development that has caused GCC economic growth to slow, their budgets to fall into deficit, and the balance of their ample sovereign wealth funds to decline. Oil and gas reserves have made Qatar the country with the world's highest per capita income. Qatar is a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), along with other GCC states Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and UAE and other countries. However, on December 3, 2018, Qatar announced it would withdraw from OPEC in early 2019 in order to focus on its more high-priority natural gas exports. Some observers attributed the decision, at least in part, to the ongoing intra-GCC rift, insofar as rival Saudi Arabia is considered the dominant actor within OPEC.

The economic impact on Qatar of the June 2017 intra-GCC rift is difficult to discern. About 40% of Qatar's food was imported from Saudi Arabia precrisis, and there were reports of runs on stocks of food when the blockade began. However, the government's ample financial resources enabled it to quickly arrange substitute sources of goods primarily from Turkey, Iran, and India. The effects on Qatar's growing international air carrier, Qatar Airways, have been significant because of the prohibition on its overflying the blockading states. In November 2017, Iran and Turkey signed a deal with Qatar to facilitate the mutual transiting of goods.

Qatar's main sovereign wealth fund, run by the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), as well as funds held by the Central Bank, total about $350 billion, according to Qatar's Central Bank governor in July 2017, giving the country a substantial cushion to weather its financial demands.7072 QIA's investments consist of real estate and other relatively illiquid holdings, such as interest in London's Canary Wharf project. In May 2016, Qatar offered $9 billion in bonds as a means of raising funds without drawing down its investment holdings.7173 In April 2018, the country raised $12 billion in another, larger, bond issue. Qatar also has cut some subsidies to address its budgetary shortfalls. In early October 2017, it was reported that QIA is considering divesting a large portion of its overseas assets and investing the funds locally—a move that is at least partly attributable to the economic pressures of the intra-GCC rift.7274

The intra-GCC rift has not harmed Qatar's ability to earn substantial funds from energy exports. Oil and gas still account for 92% of Qatar's export earnings, and 56% of government revenues.7375 Proven oil reserves of about 25 billion barrels are far less than those of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, but enough to enable Qatar to continue its current levels of oil production (about 700,000 barrels per day) for over 50 years. Its proven reserves of natural gas exceed 25 trillion cubic meters, about 13% of the world's total and third largest in the world. Along with Kuwait and UAE, in November 2016 Qatar agreed to a modest oil production cut (about 30,000 barrels per day) as part of an OPEC-wide production cut intended to raise world crude oil prices.

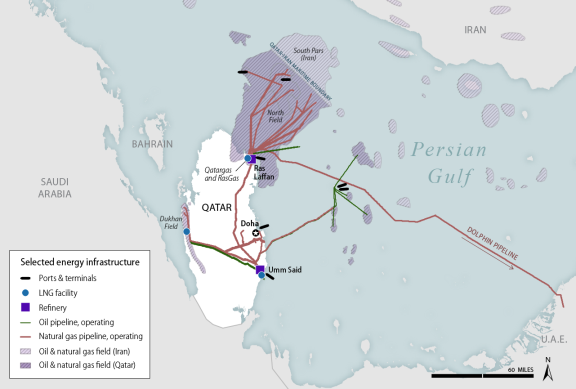

Qatar is the world's largest supplier of liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is exported from the large Ras Laffan processing site north of Doha. That facility has been built up with U.S.-made equipment, much of which was exported with the help of about $1 billion in Export-Import Bank loan guarantees. Qatar is a member and hosts the headquarters of the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF), which is a nascent natural gas cartel and includes Iran and Russia, among other countries. State-run Qatar Petroleum is a major investor in the emerging U.S. LNG export market, with a 70% stake (Exxon-Mobil and Conoco-Phillips are minority stakeholders) in an LNG terminal in Texas that is seeking U.S. government approval to expand the facility to the point where it can export over 15 million tons of LNG per year.7476 In June 2018, Qatar Petroleum bought a 30% state in an Exxon-Mobil-run development of an onshore shale natural gas basin in Argentina (Vaca Muerta).7577

Qatar is the source of the gas supplies for the Dolphin Gas Project established by the UAE in 1999 and which became operational in 2007. The project involves production and processing of natural gas from Qatar's offshore North Field, which is connected to Iran's South Pars Field (see Figure 2), and transportation of the processed gas by subsea pipeline to the UAE and Oman.7678 Its gas industry gives Qatar some counter leverage against the Saudi-led group, but Qatar has said it will not reduce its gas supplies under existing agreements with other GCC states. Both the UAE and Qatar have filed complaints at the WTO over their boycotting each other's goods; the United States reportedly has backed the UAE's arguments that the WTO does not have the authority to adjudicate issues of national security.7779

Because prices of hydrocarbon exports have fallen dramatically since mid-2014, in 2016 Qatar ran its first budget deficit (about $13 billion). As have other GCC rulers, Qatari leaders assert publicly that the country needs to diversify its economy, that generous benefits and subsidies need to be reduced, and that government must operate more efficiently. At the same time, the leadership apparently seeks to minimize the effect of any cutbacks on Qatari citizens.7880 Still, if oil prices remain far below their 2014 levels and the intra-GCC rift continues much further, it is likely that many Qatari citizens will be required to seek employment in the private sector, which they generally have shunned in favor of less demanding jobs in the government.

The national development strategy from 2011 to 2016 focused on Qatar's housing, water, roads, airports, and shipping infrastructure in part to promote economic diversification, as well as to prepare to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup soccer tournament, investing as much as $200 billion. In Doha, the result has been a construction boom, which by some reports has outpaced the capacity of the government to manage, and perhaps fund. A metro transportation system is under construction in Doha.

U.S.-Qatar Economic Relations

In contrast to the two least wealthy GCC states (Bahrain and Oman), which have free trade agreements with the United States, Qatar and the United States have not negotiated an FTA. However, in April 2004, the United States and Qatar signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA). Qatar has used the benefits of the more limited agreement to undertake large investments in the United States, including the City Center project in Washington, DC. Also, several U.S. universities and other institutions, such as Cornell University, Carnegie Mellon University, Georgetown University, Brookings Institution, and Rand Corporation, have established branches and offices at the Qatar Foundation's Education City outside Doha. In 2005, Qatar donated $100 million to the victims of Hurricane Katrina. The joint statement of the January 2018 U.S.-Qatar Strategic Dialogue "recognized" QIA's commitment of $45 billion in future investments in U.S. companies and real estate.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau's "Foreign Trade Statistics" compilation, the United States exported $4.9 billion in goods to Qatar in 2016 (about $600 million higher than 2015), and imported $1.16 billion worth of Qatari goods in 2016, slightly less than in 2015. U.S. exports to Qatar for 2017 ran about 40% less than the 2016 level, but U.S. imports from Qatar were about the same as in 2016. U.S. exports to Qatar rebounded to $4.4 billion in 2018 and imports were about $1.57 billion. U.S. exports to Qatar consist mainly of aircraft, machinery, and information technology. U.S. imports from Qatar consist mainly of petroleum products, but U.S. imports of Qatar's crude oil or natural gas have declined to negligible levels in recent years, reflecting the significant increase in U.S. domestic production of those commodities.

Qatar's growing airline, Qatar Airways, is a major buyer of U.S. commercial aircraft. In October 2016, the airline agreed to purchase from Boeing up to another 100 passenger jets with an estimated value of $18 billion—likely about $10 billion if standard industry discounts are applied. However, some U.S. airlines challenged Qatar Airways' benefits under a U.S.-Qatar "open skies" agreement. The U.S. carriers asserted that the airline's privileges under that agreement should be revoked because the airline's aircraft purchases are subsidized by Qatar's government, giving it an unfair competitive advantage.7981 The Obama Administration did not reopen that agreement in response to the complaints, nor did the Trump Administration. However, the United States and Qatar reached a set of "understandings" on civil aviation on January 29, 2018, committing Qatar Airways to financial transparency and containing some limitations on the airline's ability to pick up passengers in Europe for flights to the United States. Some assert that Qatar Airway's 2018 purchase of Air Italy might represent a violation of those limitations.

U.S. Assistance

As one of the wealthiest countries per capita in the world, Qatar gets negligible amounts of U.S. assistance. In FY2016, the United States spent about $100,000 on programs in Qatar, about two-thirds of which was for counternarcotics programming. In FY2015, the United States spent $35,000 on programs in Qatar, of which two-thirds was for counternarcotics.

|

Figure 2. Map of Qatari Energy Resources and Select Infrastructure |

|

|

Source: U.S. Energy Information Agency, as adapted by CRS. |

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report acknowledges and adapts analysis and previous CRS reports on Qatar by Christopher M. Blanchard, Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Information in this section is taken from Bernard Haykel. "Qatar and Islamism." Policy Brief: Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre. February 2013. |

|||

| 2. |

Shaykh is an honorific term. |

|||

| 3. |

The Economist. "Qatar: Democracy? That's for Other Arabs." June 8, 2013. http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21579063-rumours-change-top-do-not-include-moves-democracy-democracy-thats. |

|||

| 4. |

Amy Hawthorne. "Qatar's New Constitution: Limited Reform from the Top." August 26, 2008. http://carnegieendowment.org/sada/?fa=21605. |

|||

| 5. |

Department of State. Human Rights Report for 2015: Qatar. p. 13. |

|||

| 6. | ||||

| 7. |

Much of the information in this section is based on: Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights for 2018: https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2018&dlid=289226#wrapper . |

|||

| 8. |

Bidoon is the Arabic word for "without," and refers to persons without documentation for their residency in country. The Bidoon population is much larger in Kuwait, where that issue has been unresolved for decades. |

|||

| 9. |

State Dept human rights report on Qatar for 2017, op. cit. |

|||

| 10. |

State Dept. human rights report on Qatar for 2017, op. cit. |

|||

| 11. |

This section is based on the State Department "Trafficking in Persons" report for 2018, https://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/2018/index.htm. |

|||

| 12. |

Business and Human Rights Resources Center. May 23, 2018. |

|||

| 13. |

Statement by Human Rights Watch, September 27, 2017. |

|||

14.

|

|

15.

Qatar 2022: FIFA admits violation of workers' standards. Deutsche Welle, June 6, 2019. https://www.dw.com/en/qatar-2022-fifa-admits-violation-of-workers-standards/a-49078052. |

This section is based on the State Department report on International Religious Freedom for 2017, https://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?year=2017&dlid=281002#wrapper. |

||

|

Author conversations with GCC officials. 2013-2015. |

||||

|

Cable News Network released the text of the November 2013 agreement, which was signed between Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar. The November 2014 agreement was among all the GCC states except Oman. |

||||

|

The list of demands can be found at https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/list-of-demands-on-qatar-by-saudi-arabia-other-arab-nations/2017/06/23/054913a6-57d0-11e7-840b-512026319da7_story.html?utm_term=.5bde2f68b6b1. |

||||

|

The text of the joint statement can be found at http://www.bna.bh/portal/en/news/792679. |

||||

|

White House Office of the Press Secretary. Readout of President Donald J. Trump's Call with Amir Sheikh Tameem Bin Hamad Al Thani of Qatar. June 7, 2017. |

||||

| 21. | The U.S.-GCC summits have resulted in new U.S. commitments to assist the GCC states against Iran and other regional threats, including through new arms sales, counterterrorism cooperation, countering cyberattacks, joint military exercises, and other measures. See White House Office of the Press Secretary. "Annex to U.S.-Gulf Cooperation Council Joint Statement." May 14, 2015. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/05/14/annex-us-gulf-cooperation-council-camp-david-joint-statement. "How the Gulf crisis played out at the Makkah summit." UAE The National. June 1, 2019. |

|||

|

"Iran, Qatar, Face Off Over North Field, South Pars. Oil and Gas News," June 6-12, 2016. http://www.oilandgasnewsworldwide.com/Article/35647/Iran,_Qatar_face_off_over_North_Field,_South_Pars. |

||||

|

Al Arabiya, "Iran, Qatar Seek Improved Relations |

||||

|