Trends in the Timing and Size of DHS Appropriations: In Brief

Changes from April 4, 2019 to December 6, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Trends in the Timing and Size of DHS Appropriations: In Brief

Introduction

This report examines trends in the timing and size of homeland security appropriations measures.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was officially established on January 24, 2003. Just over a week later, on February 3, 2003, the Administration made its first annual appropriations request for the new department.1 Transfers of most of the department's personnel and resources from their existing agencies to DHS occurred March 1, 2003, and on April 16, the department received its first supplemental appropriations.

March 1, 2003, fell in the middle of fiscal year 2003 (FY2003). It was not the end of a fiscal quarter. It was not even the end of a pay period for the employees transferred to the department. Despite these administrative complications, resources and employees were transferred to the control of the department and their work continued without interruption in the face of the perceived terror threat against the United States. While the department did receive appropriations and operateoperated in FY2003, tracking the size and timing of annual appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security begins with its first annual appropriations cycle, covering FY2004.

DHS Appropriations Trends: Timing

Annual Appropriations

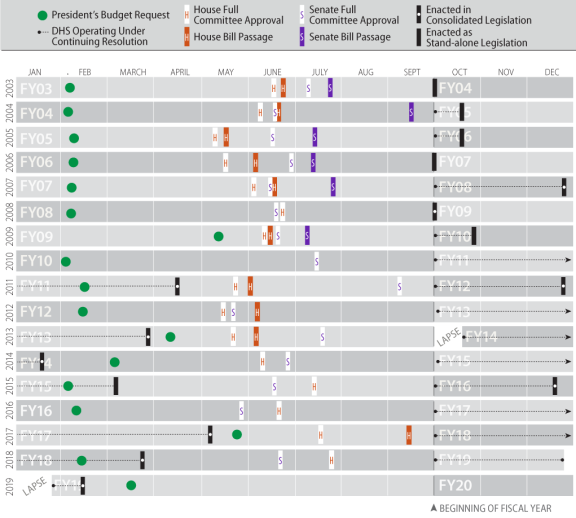

Figure 1 shows the history of the timing of the annual DHS appropriations bills as they have moved through various stages of the legislative process. Initially, DHS appropriations were enacted relatively promptly, as stand-alone legislation. However, over time, the DHS appropriations bill has been subject to the consolidation and delayed timing that has affected other annual appropriations legislation.

As Figure 1 shows, the first four annual appropriations for DHS, covering FY2004 through FY2007, were enacted as stand-alone legislation. Since FY2008, that has only occurred twice.

When annual appropriations for part of the government are not enacted prior to the beginning of the fiscal year, a continuing resolution is usually enacted to provide stopgap funding and allow operations to continue. This was avoided three times in DHS's first six annual appropriations cycles, but it has occurred every fiscal year since FY2010. The FY2017 appropriations cycle, which concluded with enactment of DHS appropriation on May 5 of that fiscal year, was the latest finalization of DHS annual appropriations levels in the history of the DHS Appropriations Act.

At the beginning of FY2014, for the first time in the history of the department, neither annual appropriations nor a continuing resolution had been enacted by the start of the fiscal year. Annual appropriations lapsed, leading to a partial shutdown of government operations, including DHS.2 In FY2019, a lapse in appropriations and partial shutdown (including DHS) occurred when a continuing resolution expired without extension or annual appropriations being enacted. That lapse ran from December 22, 2018, until January 25, 2019—the longest such shutdown in the history of the modern appropriations process.3

|

Figure 1. DHS Appropriations Legislative Timing, FY2004-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: Analysis of presidential budget request release dates and legislative action from Notes: Final action on the annual appropriations for DHS for FY2011, FY2013, FY2014, FY2015, FY2017, FY2018, FY2019, and FY2020 |

Supplemental Appropriations

In contrast to the annual appropriations measures tracked in Figure 1, supplemental appropriations move on a more ad hoc basis, when an unanticipated need for additional funding arises. Therefore, they are not reflected in the above calendar graphic.4

Supplemental funding was provided more often prior to passage of the Budget Control Act in 2011,5 when the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) often would require supplemental appropriations for the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) after a disaster struck to ensure resources would be available for initial recovery efforts. The Budget Control Act created a special exemption from the limits on discretionary spending for funding the federal costs of response to major disasters. This limited exemption has allowed FEMA to operate with a more robust balance in the DRF and thus be more prepared to respond after a major disaster without immediate replenishment by a supplemental appropriations bill. This appears to have resulted in a reduction in the frequency of supplemental appropriations legislation, and a longer timeline for its production, as there is a perception that immediate emergency needs can be met by redirecting FEMA's existing resources.

From FY2003, when DHS received its first supplemental appropriations, through 2011, the DRF received additional budget authority through supplemental appropriations bills 13 times—an average of slightly more than 1.4 times per year. From FY2012, the first year the new adjustment was in effect, the DRF has only received supplemental appropriations five times—an average of slightly more than 0.6 times per year.6

This shift in timing can be seen by comparing the Hurricane Katrina supplemental appropriations in 2005 to the Hurricane Sandy supplemental appropriations in 2012-2013. At the time Hurricane Sandy made landfall, FEMA had over $7 billion available in the DRF,7 almost three times more than was on hand when Hurricane Katrina came ashore.8

After Hurricane Katrina, the first in a series of supplemental appropriations requests was made three days from the date of disaster declaration and were enacted a day after that. After the first bill provided $10 billion for the DRF, six days later another $50 billion in appropriations was provided for the DRF—along with $2 billion for the Department of Defense, including the Army Corps of Engineers. Three and a half months later, more than $23.4 billion of that DRF funding would be rescinded and appropriated for use by other programs in a third supplemental appropriations act.

In contrast, after Hurricane Sandy, a more detailed supplemental appropriations request was submitted to Congress 38 days after the declaration and responding appropriations were enacted three months from the date of declaration.9 Funding was provided to a range of specific programs, and the $11.5 billion appropriated for the DRF only represented 19% of the request and 23% of the appropriations provided in P.L. 113-2. Unlike the case of the post-Katrina supplemental appropriations, no large-scale rescissions and reappropriations were conducted.

The legislative response to the hurricanes and wildfires of late 2017 moved more quickly than the "Sandy supplemental," as the storm struck shortly before the end of the fiscal year, and the DRF carried an unobligated balance of roughly $3.5 billion.10 The Administration made its initial request for additional resources on September 1, 2017, a week after Hurricane Harvey was declared a major disaster, and the first of three supplemental appropriations bills was enacted on September 8, 2017. As time elapsed from the storms, a second request for supplemental appropriations was made a month later, and a third, much more specific request was made about six weeks after that. The second supplemental appropriation was enacted three weeks after the request, and the third was enacted seven weeks after the request. In all, nearly $50 billion would be appropriated to the DRF in supplemental appropriations after the 2017 disaster season.11

Disaster activity has been a common driver of supplemental appropriations measures in recent decades. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), a component of DHS, is the federal government's lead agency in responding to these events, and as such, it has been a frequent recipient of supplemental appropriations. Only five bills with supplemental appropriations for DHS did not include supplemental FEMA funding.5

Supplemental funding was provided more often prior to passage of the Budget Control Act (BCA) in 2011.6 Before the BCA, FEMA often would require supplemental appropriations for the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) after a disaster struck to ensure resources would be available for initial recovery efforts.7 The BCA created a special limited exemption from statutory limits on discretionary spending, which allowed Congress to increase the annual funding level for the DRF. This resulted in a more robust balance in the DRF, which has allowed FEMA to be prepared to respond and support the initial phases of recovery after a major disaster without immediate replenishment by a supplemental appropriations bill. From FY2004 through the enactment of the BCA (FY2011), the DRF received additional budget authority through supplemental appropriations bills 13 times—an average of slightly more than 1.4 times per year. From the first year the new adjustment was in effect until now (FY2012-FY2019), the DRF has only received supplemental appropriations five times—less than half as frequently on an annual basis.8

DHS Appropriations Trends: Size

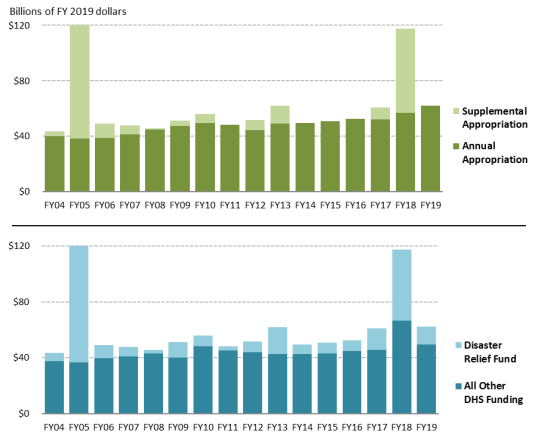

The tables and figure below present information on DHS discretionary appropriations, as enacted, for FY2004 through FY2019.129 Table 1 provides data in nominal dollars, while Table 2 provides data in constant FY2019 dollars to allow for comparisons over time. Totals include annual appropriations as well as supplemental appropriations. Figure 2 represents Table 2's data in a visual format.

Making comparisons over time of the department's appropriations as a whole is complicated by a variety of factors, the two most significant of which are the frequency of supplemental appropriations for the department, and the impact of disaster assistance funding.

Supplemental funding, which frequently addresses congressional priorities, such as disaster assistance and border security, varies widely from year to year and as a result distorts year-to-year comparisons of total appropriations for DHS. The department received over $5 billion in supplemental funding in its initial fiscal year of operations, in addition to all the resources transferred with the department's components. Twenty-one separate supplemental appropriations acts have provided appropriations to the department since it was established.1310 Gross supplemental appropriations provided to the department in those acts exceed $120 billion.

Table 1 and Table 2, in their second and third columns, provide amounts of new discretionary budget authority provided to DHS from FY2004 through FY2019, and a total for each fiscal year in the fourth column.

Disaster assistance funding is another key part of DHS appropriations. FEMA is one of DHS's larger component budgets, and funding for the DRF, which funds a large portion of the costs incurred by the federal government in the wake of disasters, is a significant driver of that budget. Of the billions of dollars provided to the DRF each year, only a single-digit percentage of this funding goes to pay for FEMA personnel and administrative costs tied to disasters; the remainder is provided as assistance to states, communities, and individuals. The gross level of funding provided to the DRF has varied widely since the establishment of DHS depending on the occurrence and size of disasters, from more than $68 billion in FY2005 to less than $3 billion in FY2008. Table 1 and Table 2, in their fifth columns, provide the amount of new budget authority provided to the DRF, and in the sixth column, show the total new budget authority provided to DHS without counting the DRF. Figure 2 presents two perspectives on the overall total in constant FY2019 dollars:

- the top graph shows the split between annual and supplemental appropriations for DHS,

- the second chart breaks out the DRF from the rest of DHS discretionary appropriations.

In nominal and constant dollars, FY2018 appropriations (excluding the DRF) represented the highest funding level for the department, surpassing the mark set in FY2017 for nominal dollars and FY2010 for constant dollars. This "high-water mark" is further elevated in these calculations due to the inclusion in the FY2018 total of $16 billion in debt cancellation for the National Flood Insurance Program, which was provided through the first FY2018 disaster supplemental appropriations act (P.L. 115-72, Div. A.). It is worth noting, however, that this FY2018 funding level would exceed the previous years' levels even if the debt cancellation were not included.

In constant dollars, FY2005 appropriations (excluding the DRF) represented the lowest level of appropriations for the DHS budget. In FY2013, sequestration reduced constant-dollar non-DRF funding levels for the department by $1.3 billion—to their lowest level since FY2009.

Table 1. DHS New Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2004-FY2019

(billions of dollars of budget authority)

|

Fiscal Year |

Annual Appropriations |

Supplemental Appropriations |

Total |

Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) Funding |

Total Less DRF Funding |

|

FY2004 |

$29,809 |

$2,523 |

$32,333 |

$4,300 |

$28,033 |

|

FY2005 |

29,557 |

67,330 |

96,887 |

68,542 |

28,345 |

|

FY2006 |

30,995 |

8,217 |

39,212 |

7,770 |

31,442 |

|

FY2007 |

34,047 |

5,161 |

39,208 |

5,610 |

33,598 |

|

FY2008 |

37,809 |

897 |

38,706 |

2,297 |

36,409 |

|

FY2009 |

40,070 |

3,243 |

43,312 |

9,360 |

33,952 |

|

FY2010 |

42,817 |

5,570 |

48,387 |

6,700 |

41,687 |

|

FY2011 |

42,477 |

— |

42,477 |

2,650 |

39,827 |

|

FY2012 |

40,062 |

6,400 |

46,462 |

7,100 |

39,362 |

|

FY2013 |

46,555 |

12,072 |

58,627 |

18,495 |

40,132 |

|

FY2013 post-sequester |

44,971 |

11,468 |

56,439 |

17,566 |

38,873 |

|

FY2014 |

45,817 |

— |

45,817 |

6,221 |

39,596 |

|

FY2015 |

47,215 |

— |

47,215 |

7,033 |

40,182 |

|

FY2016 |

49,334 |

— |

49,334 |

7,375 |

41,959 |

|

FY2017 |

49,627 |

8,540 |

58,167 |

14,729 |

43,439 |

|

FY2018 |

55,740 |

59,324 |

115,064 |

50,071 |

64,994 |

|

FY2019 |

62,178 |

— |

62,178 |

12,556 |

49,622 |

Sources: See footnote 129.

Notes: Emergency funding, appropriations for overseas contingency operations, and funding for disaster relief under the Budget Control Act's allowable adjustment are included. Transfers from the Department of Defense and advance appropriations are not included. Emergency funding in regular appropriations bills is treated as regular appropriations. Numbers in italics do not reflect the impact of sequestration. Numbers are rounded to the nearest million, but as operations were performed with unrounded data, columns may not add to totals.

Table 2. DHS New Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2019 Dollars, FY2004-FY2018

(billions of dollars of budget authority, adjusted for inflation)

|

Fiscal Year |

Regular |

Supplemental |

Total |

Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) Funding |

Total Less DRF Funding |

|

FY2004 |

$40,030 |

$3,388 |

$43,419 |

$5,774 |

$37,644 |

|

FY2005 |

38,374 |

87,416 |

125,790 |

88,989 |

36,800 |

|

FY2006 |

38,896 |

10,312 |

49,207 |

9,751 |

39,457 |

|

FY2007 |

41,576 |

6,302 |

47,878 |

6,851 |

41,027 |

|

FY2008 |

44,625 |

1,059 |

45,683 |

2,711 |

42,972 |

|

FY2009 |

47,298 |

3,827 |

51,125 |

11,048 |

40,077 |

|

FY2010 |

49,655 |

6,460 |

56,114 |

7,770 |

48,344 |

|

FY2011 |

48,135 |

— |

48,135 |

3,003 |

45,132 |

|

FY2012 |

44,513 |

7,111 |

51,624 |

7,889 |

43,736 |

|

FY2013 |

51,003 |

13,225 |

64,228 |

20,262 |

43,996 |

|

FY2013 post-sequester |

49,268 |

12,564 |

831 |

19,244 |

42,587 |

|

FY2014 |

49,415 |

— |

49,415 |

6,709 |

42,705 |

|

FY2015 |

50,648 |

— |

50,648 |

7,545 |

43,103 |

|

FY2016 |

52,555 |

— |

52,555 |

7,856 |

44,699 |

|

FY2017 |

51,985 |

8,946 |

60,931 |

15,428 |

45,503 |

|

FY2018 |

56,965 |

60,628 |

117,594 |

51,171 |

66,422 |

|

FY2019 |

62,178 |

— |

62,178 |

12,556 |

49,622 |

Sources: See footnote 129.

Notes: Emergency funding, appropriations for overseas contingency operations, and funding for disaster relief under the Budget Control Act's allowable adjustment are included. Transfers from the Department of Defense and advance appropriations are not included. Emergency funding in annual appropriations bills is treated as regular appropriations. Numbers in italics do not reflect the impact of sequestration. Numbers are rounded to the nearest million, but as operations were performed with unrounded data, columns may not add to totals.

|

Figure 2. DHS Appropriations, FY2004-FY2019, Showing Supplemental Appropriations and the DRF (in billions of constant FY2019 dollars) |

|

|

Sources: See Table 1. Notes: Emergency funding, appropriations for overseas contingency operations, and funding for disaster relief under the Budget Control Act's allowable adjustment are included. Transfers from the Department of Defense and advance appropriations are not included. Emergency funding in annual appropriations bills is treated as regular appropriations. FY2013 reflects the impact of sequestration. |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The Budget for Fiscal Year 2004, Department of Homeland Security, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BUDGET-2004-APP/pdf/BUDGET-2004-APP-1-11.pdf. |

||||||

| 2. |

For additional information, see CRS Report R43252, FY2014 Appropriations Lapse and the Department of Homeland Security: Impact and Legislation, by William L. Painter. |

||||||

| 3. |

In FY2018, two brief lapses in appropriations occurred with the expiration of continuing resolutions. The first occurred January 20, 2018, and was resolved on January 22 by the enactment of P.L. 115-120, which extended the continuing resolution through February 8, 2018. The second occurred February 9, 2018, when the extension provided by P.L. 115-120 expired, and lasted a matter of hours, until P.L. 115-123 was enacted, which included an extension of the continuing resolution through March 23, 2018, as Division B. The short duration of these lapses precludes their inclusion in the figure. |

||||||

| 4. |

There is no official definition of what qualifies as a "supplemental appropriation" or supplemental appropriations act. For convenience this report defines a supplemental appropriation as one that specifically states the amount provided is "additional," and defines a supplemental appropriations act as any act including supplemental appropriations. |

||||||

| 5. |

| ||||||

| 6. | The DRF has received funding in 18 of 24 measures carrying supplemental appropriations for DHS from FY2004 through FY2019. P.L. 111-5 and P.L. 116-26 included funding for FEMA but not the DRF. P.L. 115-31, which included annual and supplemental funding for DHS, carried annual appropriations for FEMA and the DRF, but supplemental appropriations for other components. Once to replenish the DRF in a supplemental appropriations act passed in a parallel process to the FY2012 annual appropriation for DHS (P.L. 112-77), once after Hurricane Sandy (P.L. 113-2), and three times in the wake of the 2017 hurricanes and wildfires (P.L. 115-56, P.L. 115-72, and P.L. 115-123). | ||||||

| 7. |

Abd Phillip, "After Sandy, FEMA Goes from Goat to Glory," ABC News, October 31, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/OTUS/superstorm-fema-disaster-response-praised/story?id=17599970#.UJE7V9WgWNM. |

||||||

| 8. |

Rep. Jerry Lewis, "Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act to Meet Immediate Needs Arising from the Consequences of Hurricane Katrina, 2005," House Debate, Congressional Record, vol. 151 (September 2, 2005), p. H7618. |

||||||

| 9. |

More comparative timeframes for pre-Budget Control Act supplemental appropriations are available in CRS Report R42352, An Examination of Federal Disaster Relief Under the Budget Control Act, by Bruce R. Lindsay, William L. Painter, and Francis X. McCarthy. Information on P.L. 113-2 can be found in CRS Report R44937, Congressional Action on the FY2013 Disaster Supplemental. |

||||||

| 10. |

Phone conversation with FEMA legislative affairs staff, August 28, 2017. |

||||||

| 11. |

For more information, see CRS Report R45084, 2017 Disaster Supplemental Appropriations: Overview. |

||||||

|

Underlying data for Table 1, |

|||||||

|

This includes the supplemental appropriations provided for disaster relief. |