Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Changes from January 3, 2019 to May 12, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

StatutoryStatutory Inspectors General in the Federal

May 12, 2022

Government: A Primer

Ben Wilhelm

Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Contents

- Establishment of Statutory IGs

- Brief History of Statutory IGs Until 1978

- Inspector General Act of 1978

- Central Tenets of the IG Act

- Evolution of the IG Act

- Structure of the IG Community

- Types of IGs

- Composition of Statutory IGs

- Distribution of IGs Across Federal Entities

- Multiple IGs Operating for a Single Federal Entity

- Single IG Operating for Multiple Federal Entities

- Types of IG Reviews

- Quality Standards

- Type of Analysis

- Scope of Analysis

- IG Statutory Authorities and Requirements

- Oversight Jurisdiction

- Appointment Method

- Removal Method

- Term Limits

- Transparency of Budget Formulation and Proposals

- Appropriations

- Reporting Requirements

- Transparency of IG Reports and Recommendations

- Oversight.gov

- Coordination and Oversight of Statutory IGs

- CIGIE

- Other Coordinative Bodies

- Issues for Congress

- Independence

- Appointment and Removal Methods

- Audit Follow-Up and Oversight of IG Recommendations

- Workforce Composition and Skills

- IG Effectiveness

- CIGIE Structure and Functions

Tables

- Table 1. Distinguishing Characteristics of Statutory IG Types

- Table 2. Multiple Statutory IGs Affiliated with a Single Federal Entity

- Table 3. Examples of a Single Statutory IG Affiliated with Multiple Federal Entities

- Table 4. Key Differences Among Common Types of IG Reviews

- Table 5. Appointment Methods for Statutory IGs

- Table A-1. Establishment IGs

- Table A-2. Designated Federal Entity (DFE) IGs

- Table A-3. Other Permanent IGs

- Table A-4. Special IGs

- Table B-1. Comparison of Selected Statutory Authorities and Requirements for IGs

Summary

This report provides an overview of statutory inspectors general (IGs) in the federal government, This report provides an overview of statutory inspectors general (IGs) in the federal government,

Analyst in Government

including their structure, functions, and related issues for Congress.

Report Roadmap

|

Statutory IGs—established by law rather than administrative directive—are intended to be independent, nonpartisan officials who aim to prevent and detect waste, fraud, and abuse in the federal government. To execute their missions, IGs lead offices of inspector general (OIGs) that conduct various reviews of agency programs and operations—including audits, investigations, inspections, and evaluations—and provide findings and recommendations to improve them. IGs possess several authorities to carry out their respective missions, such as the ability to independently hire staff, access relevant agency records and information, and report findings and recommendations directly to Congress.

A total of 74 statutory IGs currently operate across the federal government. Statutory IGs can be grouped into four

Non-IG

types: (1) establishment, (2) designated federal entity (DFE),

IG Act (64)

Act (10)

(3) other permanent, and (4) special. Establishment (33 of 74) and DFE ( |

|

Statutory IGs play a key role in government oversight, and Congress plays a key role in establishing the structures and authorities to enable that oversight. The structure and placement of IGs in government agencies allows OIG personnel to develop the expertise necessary to conduct in-depth assessments of agency programs. Further, IGs'’ dual reporting structure—to both agency heads and Congress—positions them to advise agencies on how to improve their programs and policies and to advise Congress on how to monitor and facilitate such improvement. Congress, therefore, may have an interest in ensuring that statutory IGs possess the resources and authorities necessary to fulfill their oversight roles.

As the federal government continues to evolve, so too does the role of IGs in government oversight. Agency programs and operations have increased in terms of breadth, complexity, and interconnectedness. Consequently, IGs may face increasing demand to complete statutorily mandated reviews of programs and operations that require (1) a broader focus on program performance and effectiveness in addition to waste, fraud, and abuse; (2) analysis of specialty or technical programs, possibly in emerging policy areas; and (3) use of more complex analytical methods and tools. Congress may wish to consider several options regarding IG structures, functions, and coordination as the role of IGs in government oversight evolves.

Issues for Congress

|

T

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 33 link to page 10 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Contents

Establishment of Statutory IGs ........................................................................................................ 1

Brief History of Statutory IGs Until 1978 ................................................................................. 1 Inspector General Act of 1978 .................................................................................................. 2

Central Tenets of the IG Act ............................................................................................... 2 Evolution of the IG Act ....................................................................................................... 3

Structure of the IG Community ....................................................................................................... 4

Types of IGs .............................................................................................................................. 4 Composition of Statutory IGs ................................................................................................... 4 Distribution of IGs Across Federal Entities .............................................................................. 5

Multiple IGs Operating for a Single Federal Entity ............................................................ 5 Single IG Operating for Multiple Federal Entities .............................................................. 6

Types of IG Reviews ....................................................................................................................... 7

Quality Standards ...................................................................................................................... 8 Type of Analysis ........................................................................................................................ 9 Scope of Analysis ...................................................................................................................... 9

IG Statutory Authorities and Requirements................................................................................... 10

Oversight Jurisdiction .............................................................................................................. 11 Appointment Method .............................................................................................................. 12 Removal Method ..................................................................................................................... 13 Term Limits ............................................................................................................................. 14 Transparency of Budget Formulation and Proposals .............................................................. 15 Appropriations......................................................................................................................... 16 Reporting Requirements .......................................................................................................... 16

Semiannual Report ............................................................................................................ 16 Seven-Day Letter .............................................................................................................. 17 Top Management and Performance Challenges ................................................................ 18

Transparency of IG Reports and Recommendations ............................................................... 18 Oversight.gov .......................................................................................................................... 20

Coordination and Oversight of Statutory IGs ................................................................................ 20

Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency ............................................... 20 Other Coordinating Bodies ..................................................................................................... 21

Issues for Congress ........................................................................................................................ 22

Independence .................................................................................................................... 23 Appointment and Removal Methods ................................................................................ 24 Audit Follow-Up and Oversight of IG Recommendations ............................................... 26 Workforce Composition and Skills ................................................................................... 27 IG Effectiveness ................................................................................................................ 27 CIGIE Structure and Functions ......................................................................................... 28

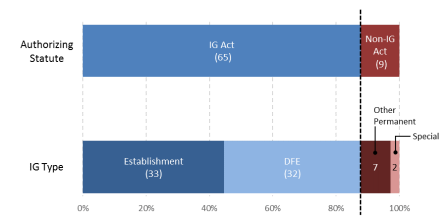

Figures Figure 1. Statutory IGs by Type and Authorizing Statute ............................................................... 5

Congressional Research Service

link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 13 link to page 18 link to page 34 link to page 36 link to page 37 link to page 37 link to page 39 link to page 34 link to page 38 link to page 44 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Tables Table 1. Distinguishing Characteristics of Statutory IG Types ....................................................... 4 Table 2. Multiple Statutory IGs Affiliated with a Single Federal Entity ......................................... 6 Table 3. Examples of a Single Statutory IG Affiliated with Multiple Federal Entities ................... 7 Table 4. Key Differences Among Common Types of IG Reviews .................................................. 8 Table 5. Appointment Methods for Statutory IGs ......................................................................... 13

Table A-1. Establishment IGs ........................................................................................................ 29 Table A-2. Designated Federal Entity (DFE) IGs .......................................................................... 31 Table A-3. Other Permanent IGs ................................................................................................... 32 Table A-4. Special IGs ................................................................................................................... 32 Table B-1. Comparison of Selected Statutory Authorities and Requirements for IGs .................. 34

Appendixes Appendix A. Statutory Inspectors General by Type ...................................................................... 29 Appendix B. Selected IG Statutory Authorities and Requirements ............................................... 33

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 39

Congressional Research Service

link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 12 link to page 15 link to page 25 link to page 27 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

his report provides an overview of statutory inspectors general (IGs) in the federal government, including their structure, functions, and related issues for Congress.

Report Roadmap

|

Establishment of Statutory IGs

Statutory inspectors general (IGs) are intended to be independent, nonpartisan officials who prevent and detect waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement within federal departments and agencies. To execute their missions, IGs lead offices of inspector general (OIGs) that conduct audits, investigations, and other evaluations of agency programs and operations and produce recommendations to improve them. Statutory IGs exist in more than 70 federal entities, including departments, agencies, boards, commissions, and government-sponsored enterprises.

Brief History of Statutory IGs Until 1978

The origins of the modern-day IGs can be traced back to the late 1950s, with the statutory establishment of an "“IG and Comptroller"” for the Department of State in 1959 and administrative creation of. Soon after, in 1962, the Kennedy Administration created an IG for the Department of Agriculture.11 Prior to the establishment of IGs in the federal government, agencies often employed internal audit and investigative units to combat waste, fraud, and abuse.2

2

Congress established the first statutory IG that resembles the modern-day model in 1976 for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW; now the Department of Health and Human Services).33 Congressional investigations had uncovered widespread inefficiencies and mismanagement of the department'’s programs and operations, as well as weaknesses within the department'department’s audit and investigative units.44 The House Committee on Government Operations investigative report recommended, among other things, that the Secretary of HEW place all audit 1 Congress established the Department of State “Inspector General and Comptroller” in 1959 (P.L. 86-108), and the Secretary of Agriculture administratively created an IG in 1962. These two IGs have been described as early prototypes for modern-day IGs. For more information on the history of IGs, see Paul Light, Monitoring Government, Inspectors General and the Search for Accountability (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1993), pp. 23-43.

2 See, for example, U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Operations, Subcommittee on Intergovernmental Relations and Human Resources, Establishment of Offices of Inspectors General, hearings on H.R. 2819 and H.R. 4184, 95th Cong., 1st sess., May 17, 24; June 1, 7, 13, 21, 29; and July 25, 27 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1977), pp. 478-728.

3 P.L. 94-505, §401(h). 4 See, for example, U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Operations, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (Prevention and Detection of Fraud and Program Abuse), Tenth Report, 94th Congress, 2nd sess., January 26, 1976, H.Rept. 94-786 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1976).

Congressional Research Service

1

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

investigative report recommended, among other things, that the Secretary of HEW place all audit and investigation units "“under the direction of a single official who reports directly to the Secretary and has no program operating responsibilities" who.”5 This official would be responsible for identifying "“serious problems"” and "“lack of progress in correcting such problems."5”6 Congress ultimately established the HEW IG under this model.6 Congress also establishedmodel7 as well as an IG for the Department of Energy IG under a similar model in 1977.7

8 Inspector General Act of 1978

The establishment of the HEW and Department of Energy IGs laid the groundwork for Congress to create additional statutory IGs through the Inspector General Act of 1978 (hereinafter IG Act).8 9 According to the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs report that accompanied the bill that became lawlegislation, the committee believed that extending the IG concept to more agencies would ultimately improve government programs and operations.910 The committee further identified IG independence from agency management as a key characteristic in fostering such improvements.10

11 Central Tenets of the IG Act

The IG Act initially created 12 IGs for federal "establishments"“establishments” and provided a blueprint for IG authorities and responsibilities.1112 The act laid out three primary purposes for IGs:

1.1. conduct audits and investigations of programs and operations of their affiliated federal entities;122.13 2. recommend policies that promote the efficiency, economy, and effectiveness of agency programs and operations, as well as preventing and detecting waste, fraud, and abuse; and3.3. keep the affiliated entity head and Congress"“fully and currently informed"” of fraud and"“other serious problems, abuses, and deficiencies"” in such programs and operations, as well as progress in implementing related corrective actions.13

14

5 Ibid., p. 11. 6 Ibid. 7 U.S. Congress, House Committee on Government Operations, report to accompany H.R. 15390, 94th Congress, 2nd sess., H.Rept. 94-1573 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1976).

8 P.L. 95-91, §208. 9 P.L. 95-452; The IG Act, as amended, is listed in 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), which is accessible at http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title5/title5a/node20&edition=prelim.

10 U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, report to accompany H.R. 8588, 95th Congress, 2nd sess., August 8, 1978, S.Rept. 95-1071 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1978), pp. 6-8.

11 Ibid. 12 Federal “establishments” consist of cabinet-level departments and larger agencies in the executive branch. Establishment IGs are appointed by the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.

13 Affiliated federal entity refers to an entity within the scope of an IG’s jurisdiction. For example, the Department of Homeland Security and its components are considered an “affiliated federal entity” of the department’s IG. 14 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §2.

Congressional Research Service

2

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Evolution of the IG Act

Evolution of the IG Act

Congress has substantially amended the IG Act three times since its enactment, as described below.1415 The amendments generally aimed to expand the number of statutory IGs and enhance their independence, transparency, and accountability.

-

The Inspector General Act Amendments of 1988 (P.L. 100-504) expanded the

total number of statutory IGs, particularly by authorizing additional establishment IGs and creating a new category of IGs for

"“designated federalentities"entities” (DFEs).1516 The act also established a uniform salary rate and separate appropriations accounts for each establishment IG. Further, the act added several new semiannual reporting requirements for IGs, such as a requirement for IGs to provide a list of each audit report issued during the reporting period. Finally, the law required external peer reviews of OIGs, during which a federal"“audit entity"” reviews each OIG'’s internal controls and compliance with audit standards. -

The Inspector General Reform Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-409) established a new

Council of Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE) to coordinate and oversee the IG community, including an Integrity Committee to investigate alleged IG wrongdoing. The law

alsoincreased the uniform salary rate for establishment IGs and established a salary formula for DFE IGs. The act also provided additional authorities and protections to enhance the independence of IGs, such as budget protections, access to independent legal counsel, and advanced congressional notification for the removal or transfer of IGs. Finally, the act further amended IG semiannual reporting obligations and required OIG websites to include all completed audits and reports. -

The Inspector General Empowerment Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-317) aimed to

enhance IG access to and use of agency records. The act exempted IGs from the Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act (CMPPA),

1617 which is intended to allow IGs to conduct computerized data comparisons across different agency automated record systems withoutrestrictions in the law.17the restrictions created by the CMPPA.18 The act also directed CIGIE to resolve jurisdictional disputes between IGs and altered the membership structure and investigatory procedures of the CIGIE Integrity Committee. Regarding transparency and accountability, the act required IGs to submit any documents containing recommendations for corrective action to agency heads and congressional committees of jurisdiction, as well as any Member of Congress or other individuals upon request. 15 In addition, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 vested certain OIGs with law enforcement authorities, including the power to (1) carry a firearm; (2) make arrests without a warrant; and (3) seek and execute warrants for arrest, search of premises, or seizure of evidence. See P.L. 107-296, §812; listed in 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §6(f). 16 DFEs consist primarily of smaller entities, such as commissions, boards, and government-sponsored enterprises (e.g., National Science Foundation and Legal Services Corporation). DFE IGs are appointed by the affiliated entity heads. 17 The CMPPA is codified at 5 U.S.C. §552a. 18 See 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §6(j). Congressional Research Service 3 link to page 9 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A PrimerMember of Congress or other individuals upon request.

Structure of the IG Community

Types of IGs

Statutory IGs may be grouped into four types: (1) establishment, (2) DFEdesignated federal entity (DFE), (3) other permanent, and (4) special.1819 Federal laws explicitly define only the first two types of IGs but not the latter two types, though stakeholders sometimes describe IGs in this waydivide IGs into these four types. Consequently, this report groups IGs into the four types based on criteria that are commonly used to distinguish between IGs, including authorizing statute, appointment method, affiliated federal entity and the branch of government in which it is located, oversight jurisdiction, and oversight durationduration. Table 1 describes each IG type according to these criteria.

Table 1. Distinguishing Characteristics of Statutory IG Types

Other

Feature

Establishment IG

DFE IG

Permanent IG

Special IG

Authorizing

IG Act

Individual statutes outside of the IG Act

statute

Appointment

President, with the

Agency head

President, with the

President, with the

method

advice and consent

advice and consent

advice and consent

of the Senate

of Senate

of Senate

or

or

agency head

President alone

Affiliated federal Cabinet

Smaller entities (e.g.,

Certain legislative

Some affiliated with

entity

departments,

boards, commissions,

branch agencies

specified federal

cabinet-level

and government-

Certain intelligence

entities; others not

agencies, and larger

sponsored enterprises)

agencies outside of

expressly affiliated

agencies in the

Certain intelligence

DOD

with a particular

executive branch

agencies within DOD

entity

Oversight

Authority to oversee the programs and

Authority to

jurisdiction

Table 1. Distinguishing Characteristics of Statutory IG Types

|

Feature |

Establishment IG |

DFE IG |

Other Permanent IG |

Special IG |

|

Authorizing statute |

IG Act |

Individual statutes outside of the IG Act |

||

|

Appointment method |

President, with the advice and consent of the Senate |

Agency head |

President, with the advice and consent of Senate or agency head |

President, with the advice and consent of Senate or President alone |

|

Affiliated federal entity |

Cabinet departments, cabinet-level agencies, and larger agencies in the executive branch |

Smaller entities (e.g., boards, commissions, and government-sponsored enterprises) Certain intelligence agencies within DOD |

Certain legislative branch agencies Certain intelligence agencies outside of DOD |

N/A. Not expressly affiliated with a particular federal entity |

|

Oversight jurisdiction |

|

| ||

|

Oversight duration |

Permanent (no sunset date) |

Temporary (allowed to sunset) |

||

Source: CRS analysis of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, and authorizing statutes for other IGs.

Notes: IGs can be grouped into types other than those listed based on a different set of criteria.

Composition of Statutory IGs

As of January 2019March 2022, 74 statutory IGs operated in the federal government.1920 The IG Act governs 65 64 IGs, including 33 establishment and 3231 DFE IGs. The remaining nine10 IGs are governed by

19 The types do not include statutory IGs for certain U.S. Armed Forces—the Army, Air Force, and Navy. (The Department of Homeland Security IG oversees the U.S. Coast Guard.) Further, the categories do not include nonstatutory IGs. For example, the House of Representatives IG is authorized pursuant to House Rule II, clause 8. See CRS In Focus IF11024, Office of the House of Representatives Inspector General, by Jacob R. Straus.

20 This number does not reflect statutory IGs that have been abolished.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 34 link to page 11

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

IGs are governed by individual statutes outside the IG Act, including seven other permanent and two3 special IGs (Figure 1Error! Reference source not found.). Five out of seven other permanent IGs operate for legislative branch agencies—the Architect of the Capitol (AOC), Government Publishing Office (GPO), Government Accountability Office (GAO), Library of Congress (LOC), and U.S. Capitol Police (USCP). The remaining two operate for executive branch intelligence agencies—the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Intelligence Community (IC). The twothree special IGs include those are the IGs for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) and, the Troubled Asset Relief Program (SIGTARP).20, and Pandemic Recovery (SIGPR).21 Appendix A lists current statutory IGs by type.

Distribution of IGs Across Federal Entities

The majority of IGs oversee the activities of a single affiliated federal entity and its components. For example, the IG for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is responsible for evaluating programs and operations of the entire department and its components, such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency. In some cases, however, multiple IGs operate for a single entity. In other cases, one IG operates for multiple entities.

Multiple IGs Operating for a Single Federal Entity

Two cabinet-level departments are affiliated with more than one IG: the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Department of the Treasury. Both departments have a department-wide IG and one or more separate IGs for certain components or programs (Table 2).

21 SIGTARP (P.L. 110-343, §121) is listed in 12 U.S.C. §5231, SIGAR (P.L. 110-181, §1229) is listed in 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G note, and SIGPR (P.L. 116-136, §4018) is listed in 15 U.S.C. §9053.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 12 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Table 2. Multiple Statutory IGs Affiliated with a Single Federal Entity

Department of Defense (DOD) IGs |

Department of the Treasury (DOT) IGs

DOD (department-wide)

DOT (department-wide)

Defense Intelligence Agency

Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration

National Geospatial Intelligence Agency

(Internal Revenue Service)

National Security Agency

Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery

National Reconnaissance Office

(Certain CARES Act programs)

|

|

DOD (department-wide) Defense Intelligence Agency National Geospatial Intelligence Agency National Security Agency National Reconnaissance Office |

DOT (department-wide) Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (Internal Revenue Service) |

Source: CRS analysis of the Inspector General Act of 1978 and other statutes governing the listed IGs.

Notes: The table does not include IGs for U.S. Armed Forces within the DOD—the Air Force, Army, and Navy. While these military IGs exist in statute, their structure and authorities differ significantly from other statutory IGs and are beyond the scope of this report. In addition, the table does not include the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) or the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (SIGTARP). Although SIGAR and SIGTARP might evaluate, respectively, DOD and DOT programs, they are not housed in or affiliated with the departments.

While the Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery (SIGPR) is similar in authority and function to SIGAR and SIGTARP, it is organized within DOT under 15 U.S.C. §9053(a). Single IG Operating for Multiple Federal Entities

Congress has authorized some IGs to oversee the programs, operations, and activities of more than one entity either on a permanent or temporary basis. The expansion of an IG'’s jurisdiction to include multiple entities has generally stemmed from agency reorganizations or congressional concern regarding oversight of a particular agency or program.

22

Table 3 provides examples of IGs who have permanent expanded jurisdiction. In the past, Congress has also temporarily expanded IG jurisdiction to include operations of unaffiliated agencies. For example, Congress directed the GAO IG to serve concurrently as the IG for the Commission on Civil Rights for FY2012 and FY2013.2123 The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014, authorized the DOT IG to oversee the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA), a nonfederal entity.24

22 A recent example of legislation that established such an arrangement is the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-108; H.R. 3076), which abolished the OIG for the Postal Regulatory Commission and reorganized its functions into the OIG for the United States Postal Service. See CRS Insight IN11685, Changes to Postal Regulatory Commission Administration in the Postal Service Reform Act of 2022, by Ben Wilhelm.

23 P.L. 112-55, Division B, Title IV, 125 Stat. 628; P.L. 113-6, Division B, Title IV, 128 Stat. 266; GAO, OIG, Semiannual Report, April 1, 2014-September 30, 2014, October 2014, p. 5, https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/667257.pdf.

24 P.L. 113-76, Division L, Title I; 128 Stat. 600. It is unclear whether the IG has overseen MWAA beyond FY2015.

Congressional Research Service

6

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Table 3. Examples of a Single Statutory IG Affiliated with Multiple Federal Entities

Office of

Inspector

Affiliated federal

Authorizing statute

General

entities

Description

and U.S. Code citation

Intelligence

IC elements (defined

The IC IG is explicitly authorized to

P.L. 111-259, §405

Community

in 50 U.S.C. §3003)

oversee the programs and activities under

Codified in 50 U.S.C.

(IC)

(MWAA), a nonfederal entity.22

|

Office of Inspector General |

Affiliated federal entities |

Description |

Authorizing statute and U.S. Code citation |

|

Intelligence Community (IC) |

IC elements (defined in 50 U.S.C. §3003) |

|

P.L. 111-259, §405 Codified in 50 U.S.C. §3033 |

|

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB) |

(1) FRB (2) Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) |

|

P.L. 111-203, §§1011 and 1081 Listed in 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act) §8G(a)(2). |

|

Department of Transportation (DOT) |

(1) DOT (2) National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) |

|

P.L. 106-424, §12 Codified in 49 U.S.C. §1137 |

|

Department of State (DOS) |

(1) DOS (2) Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) |

The DOS IG's jurisdiction was expanded to include BBG upon the agency's removal from the DOS and establishment as an independent agency in 1998 under the Foreign Affairs and Restructuring Act. |

P.L. 105-277, Division G, Title XIII, Chapter 3, §1322 Listed in 22 U.S.C. §6209a |

|

U.S. Aid for International Development (USAID) |

(1) USAID (2) Overseas Private Investment Corporation |

The USAID IG has explicit authority to "conduct reviews, investigations, and inspections of all phases of the Corporation's activities and activities." |

P.L. 87-195, §239(e) Listed in 22 U.S.C. §2199(e) |

Source: CRS analysis of statutes authorizing or expanding the oversight jurisdiction of each listed IG.

Source: CRS analysis of statutes authorizing or expanding the oversight jurisdiction of each listed IG.

Types of IG Reviews Types of IG Reviews

IGs conduct reviews of government programs and operations. The genesis and frequency of such reviews can vary. An IG generally conducts a review in response to a statutory mandate, at the request of Congress or other stakeholders (e.g., the President), or upon self-initiation. Reviews can occur once or periodically. IG reviews can be grouped into three broad categories: (1)

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

performance audits,25performance audits,23 (2) inspections or evaluations, and (3) investigations.2426 Table 4 and the sections below discuss certain differences between the review types in terms of three characteristics: quality standards, scope of analysis, and type of analysis.

Table 4. Key Differences Among Common Types of IG Reviews

Characteristic

Performance Audita

Inspection or Evaluation

Investigation

Quality

Generally Accepted

Quality Standards for Inspection

Quality Standards for

standards

Government Auditing

and Evaluation (also known as

Investigationsc,e

Standards (GAGAS, also

the Blue Book)c,d

known as the Yellow Book)b,c

Type of analysis

Programmatic (compliance, efficiency and effectiveness,

Nonprogrammatic (individual

internal control, prospective analysis)f

misconduct)

Scope of

Entire agency program or

Specific aspect of a program

Actions of a government

analysis

operation

or operation or a specific

employee, contractor, or

agency facility

grantee

Table 4. Key Differences Among Common Types of IG Reviews

|

Characteristic |

|

Inspection or Evaluation |

Investigation |

|

Quality standards |

|

|

|

|

Type of analysis |

|

Nonprogrammatic (individual misconduct) |

|

|

Scope of analysis |

Entire agency program or operation |

Specific aspect of a program or operation or a specific agency facility |

Actions of a government employee, contractor, or grantee |

Source: CRS analysis of laws, regulations, and administrative directives governing statutory IGs.

Source: CRS analysis of laws, regulations, and administrative directives governing statutory IGs. Notes: The table does not reflect all differences among audits, inspections or evaluations, and investigations. In addition, differences in the "“scope of analysis"” between a performance audit and inspection or evaluation vary and depend on the issue being evaluated. In some cases, the scope of analysis might be similar.

a. In addition to performance audits, IGs must conduct, or hire an independent external auditor to conduct,

audits of agency financial statements (commonly referred to as a financial audit). See 31 U.S.C. §3521(e). Financial audits are beyond the scope of this report.

b.

b. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issues a publication containing the GAGAS, which is

accessible at https://www.gao.gov/yellowbook/overview.

c. overview.

c. The Council of Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE) issues Quality Standards for Federal

Offices of Inspectors General, known as the Silver Book, which apply to all IG reviews. The standards are accessible at https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/Silver%20Book%20Revision%20-%208-20-12r.pdf.

d.

d. These CIGIE-issued standards are accessible at https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/iestds12.pdf.

e.

QualityStandardsforInspectionandEvaluation-2020.pdf.

e. These CIGIE-issued standards are accessible at https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/

invprg1211appi.pdf. Criminal investigations conducted by OIGs with statutory law enforcement authority are also governed by guidelines established by the Attorney General. See U.S. Department of Justice, Guidelines for OIGs With Statutory Law Enforcement Authority, December 2003, https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/agleguidelines.pdf.

f. GAO'.

f.

GAO’s Yellow Book identifies and defines four categories of performance audit objectives: (1) program effectiveness and results, (2) internal control, (3) compliance, and (4) prospective analysis. See GAO, Government Auditing Standards, 2018 Revision, GAO-18-568G, pp. 10-14, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/693136.pdf.

Quality Standards

IG reviews are governed by different quality standards. IG audits are subject to the generally accepted government auditing standards (GAGAS) developed by GAO.25 Inspections or 27 Inspections or

25 OIG audits can be divided into two subcategories: performance and financial. Financial audits are beyond the scope of this report.

26 OIG investigations can be divided into two subcategories: criminal and administrative. IGs also perform other types of reviews outside of these three categories. For example, the U.S. Postal Service IG periodically issues white papers on certain topics, which are accessible at https://www.uspsoig.gov/document-type/white-papers.

27 See GAO, “The Yellow Book,” at https://www.gao.gov/yellowbook/overview.

Congressional Research Service

8

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

evaluations and investigations, by contrast, are governed by separate standards developed by the CIGIE.2628 While several standards are identical or similar across the three review types, the requirements to meet those standards differ by type. For example, one GAO report noted that IG audits are "“subject to more depth in the requirements for levels of evidence and documentation supporting findings"” than IG inspections.27

29

IG Audits vs. Inspections or Evaluations:

Both IG audits and inspections or evaluations must adhere to a IG audit: GAO 30 IG inspection or evaluation: CIGIE |

Type of Analysis

IG audits and inspections or evaluations include programmatic analysis, which may involve analyses related to the compliance, internal control, or efficiency and effectiveness of agency programs and operations.3032 They also often include recommendations to improve such programs and operations. IG investigations, by contrast, typically include nonprogrammatic analysis and instead focus primarily on alleged misuse or mismanagement of an agency'’s programs, operations, or resources by an individual government employee, contractor, or grantee. Unlike audits and inspections or evaluations, IG investigations can directly result in disciplinary actions that are criminal (e.g., convictions and indictmentsindictments and prosecutions) or administrative (e.g., monetary payments, suspension/debarment, or termination of employment).

Scope of Analysis

Performance audits may be broader in scope compared to inspections or evaluations and investigations. A performance audit may assess the agency-wide implementation of a program across multiple agency components and facilities. An inspection or evaluation, by contrast, may sometimes focus on a specific aspect of a program or the operations of a particular agency facility

28 CIGIE’s Quality Standards for Inspection and Evaluation are outlined in the Blue Book and are accessible at https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/QualityStandardsforInspectionandEvaluation-2020.pdf. CIGIE’s Quality Standards for Investigations are accessible at https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/files/invprg1211appi.pdf.

29 GAO, Inspectors General, Activities of the Department of State Office of the Inspector General, GAO-07-138, March 2007, p. 19, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/260/258069.pdf.

30 GAO, Government Auditing Standards 2018 Revision, July 2018, GAO-18-568G, pp. 89-91, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/files.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-568g.pdf.

31 CIGIE, Quality Standards for Inspection and Evaluation, January 2012, p. 8. 32 GAO’s Yellow Book identifies and defines four categories of performance audit objectives: (1) program effectiveness and results, (2) internal control, (3) compliance, and (4) prospective analysis. The Yellow Book further states that these objectives can be pursued simultaneously within a single audit. See GAO, Government Auditing Standards, 2018 Revision, GAO-18-568G, pp. 10-14, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/files.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-568g.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

9

link to page 38 link to page 38 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

sometimes focus on a specific aspect of a program or the operations of a particular agency facility or geographic region containing agency facilities. Investigations typically focus on the actions of a specific agency employee, grantee, or contractor for alleged misconduct or wrongdoing.

Example of Differences in Units of Analysis Among an IG Performance Audit, Inspection or Evaluation, and Investigation The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) IG conducted several reviews of veteran wait times and access to care that varied in scope and analysis, such as

|

35 IG Statutory Authorities and Requirements

IGs possess many authorities and responsibilities to carry out their respective missions, many of which aim to establish and protect IG independence from undue influence. For example, the IG Act grants covered IGs with broad authority to

- conduct audits and investigations, which cannot be prohibited or prevented by the affiliated entity head (except, in some cases, for national security reasons);

-

access directly the records and information related to the affiliated entity

's’s programs and operations; - request assistance from other federal, state, and local government agencies;

- subpoena information and documents;

- administer oaths when conducting interviews;

- independently hire staff and manage their own resources; and

- receive and respond to complaints of waste, fraud, and abuse from agency

employees, whose identity is to be protected.

34

36

The subsections below and Appendix B compare selected statutory authorities and requirements by IG type: establishment, DFE, other permanent, and special. However, the manner in which each IG interprets and implements these authorities and responsibilities can vary widely, thus potentially resulting in substantially different structures, operations, and activities across IGs.

The discussion in this section focuses on IG authorities and requirements that are expressly mandated in the applicable authorizing statute.3537 Although special IGs and other permanent IGs in 33 VA OIG, Veterans Health Administration, Audit of Veteran Wait Time Data, Choice Access, and Consult Management in VISN 6, March 2, 2017, at https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/vaoig-16-02618-424.pdf.

34 VA OIG, Healthcare Inspection, Scheduling, Staffing, and Quality of Care Concerns at the Alaska VA Healthcare System, Anchorage, Alaska, July 7, 2015, at https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-14-04077-405.pdf.

35 VA OIG, Administrative Summary of Investigation by the VA Office of the Inspector General in Response to Allegations Regarding Patient Wait Times, VA Medical Center in Salisbury, North Carolina, October 4, 2016, at https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/admin-reports/wait-times-14-02890-255.pdf.

36 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§3(a), 6(a), 6(e), and 7. Authorities and requirements may differ for IGs not explicitly covered by the IG Act. For more information on selected IG authorities and requirements, see Appendix B.

37 Where possible, the subsections provide examples of instances in which IGs have elected to comply with a

Congressional Research Service

10

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Although special IGs and other permanent IGs in the legislative branch are not created under the IG Act, their authorizing statutes incorporate—and therefore make applicable—certain provisions of the IG Act. These "“incorporation by reference" ” provisions are subject to some interpretation. Even when the authorizing statute for a special IG or other permanent IG in the legislative branch clearly and unequivocally incorporates a specific provision of the IG Act, interpretation may vary regarding whether subsequent amendments to that incorporated provision apply to the IGs if they occurred after the enactment of the IG's ’s authorizing statute.36

38 Oversight Jurisdiction

As mentioned previously, establishment, DFE, and other permanent IGs generally do not have cross-agency jurisdiction and therefore evaluate only the programs, operations, and activities of their respective affiliated agencies. For example, the DHS IG must annually evaluate the department'department’s information security programs and practices, but it does not evaluate such programs and practices for another department.3739 Oversight jurisdiction, however, can extend to nonfederal third parties, such as contractors and grantees. For example, the IG for the National Archives and Records Administration audited the agency'’s management of grant fund use by certain grantees.38

Special40

Some special IGs, by comparison, possess express cross-agency jurisdiction:. They are authorized to evaluate a specific program, operation, or activity irrespective of the agencies implementing them. For instance, SIGAR oversees all federal funding for programs and operations related to Afghanistan reconstruction, which involves multiple agencies. SIGAR, therefore, may examine government-wide efforts to train, advise, and assist the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces.3941 The DOD IG, by contrast, may examine only reconstruction activities under DOD's ’s purview, such as the military'’s efforts to train, advise, and assist the Afghan Air Force.40

42

SIGPR and Pandemic Oversight

In March 2020, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Recovery, and Economic Security (CARES) Act,43 which provided funding to a number of federal agencies and programs in response to the pressures created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The CARES Act also established a variety of oversight mechanisms to monitor how these

nonmandatory provision.

38 Although an argument can be made that the incorporation by reference includes subsequent amendments to the referenced statute, it would also appear that traditional canons of statutory interpretation may suggest that the proper construction of the authorizing statutes is that they incorporate only the text of the referenced provisions as they existed at the time the applicable authorizing statute was adopted. See Hassett v. Welch, 303 U.S. 303, 314 (1938), wherein the court stated, “Where one statute adopts the particular provisions of another by a specific and descriptive reference to the statute or provisions adopted, the effect is the same as though the statute or provisions adopted had been incorporated bodily into the adopting statute…. Such adoption takes the statute as it exists at the time of adoption and does not include subsequent additions or modifications of the statute so taken unless it does so by express intent.” Legal interpretation of the treatment of provisions incorporated by reference are beyond the scope of this report.

39 This assessment is required by the Federal Information Security Modernization Act. See 44 U.S.C. §3555. 40 National Archives and Records Administration OIG, Audit of NARA’s Oversight of Selected Grantees’ Use of Grant Funds, February 16, 2011, at https://www.archives.gov/files/oig/pdf/2011/audit-report-11-03.pdf.

41 See, for example, SIGAR, Reconstructing the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces: Lessons Learned from the U.S. Experience in Afghanistan, September 2017, at https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/lessonslearned/SIGAR-17-62-LL.pdf.

42 DOD OIG, Progress of U.S. and Coalition Efforts to Train, Advise, and Assist the Afghan Air Force, January 4, 2018, at https://media.defense.gov/2018/Jan/29/2001870851/-1/-1/1/DODIG-2018-058-REDACTED.PDF.

43 P.L. 116-136

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 18 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

funds were used. This included the creation of the Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery (SIGPR) to provide oversight of Department of Treasury (DOT) programs included in Title IV of the CARES Act.44 Unlike the other two special IGs (the SIGAR and SIGTARP), SIGPR’s jurisdiction is limited to certain activities of the DOT under the CARES Act and does not extend to other agencies. In addition, there has been disagreement within DOT regarding the extent of SIGPR’s jurisdiction. SIGPR has argued that its jurisdiction extends to all DOT programs under the CARES Act, while other DOT officials have argued that its jurisdiction is limited to Title IV programs. In April 2021, the Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel issued an opinion concluding that the SIGPR’s jurisdiction was limited to CARES Act Title IV programs.45 SIGPR has asked Congress to consider expanding its jurisdiction.46

Appointment Method Most statutory IGs (72 of 74) Appointment Method

Most (72 of 74) statutory IGs must be appointed "“without regard to political affiliation"” and "“on the basis of integrity and demonstrated ability in accounting, auditing, financial analysis, law, management analysis, public administration, or investigations."41”47 Statutory IGs are appointed under one of three different methods:

1.1. by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate;2.2. by the President alone; or3.3. by the head of the affiliated federal entity.

As shown in Table 5, a total of 37total of 38 out of 74 statutory IGs are appointed by the President, 3637 of which—establishment IGs (33), other permanent IGs in the executive branch (2), the SIGTARP, and SIGPRand SIGTARP—require Senate confirmation. The IG for SIGAR is the only statutory IG appointed by the President alone without Senate confirmation. In addition, 3736 out of 74 IGs are appointed by the heads of their affiliated federal entities: DFE (32designated federal entity (DFE) (31) and other permanent IGs in the legislative branch (5). Unlike other IGs, the USCP and AOCUnited States Capitol Police and Architect of the Capitol IGs must be appointed by their affiliated entity heads in consultation with other permanent IGs in the legislative branch.48

44 CARES Act §4018(c)(1); 15 U.S.C. §9053(c)(1). 45 See “Authority of the Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery to Oversee Programs Established Under the CARES Act,” Memorandum Opinion for the Acting General Counsel Department of the Treasury, and the Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery, April 29, 2021, at https://www.justice.gov/olc/file/1390936/download.

46 See, for example, Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress: April to June 2021, July 30, 2021, p. 20, at https://www.sigpr.gov/sites/sigpr/files/2021-07/SIGPR-Quarterly-Report-June-2021-Final.pdf.

47 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §3(a) and §8G(c) (establishment and DFE IGs); 2 U.S.C. §1808(c)(1)(a) (AOC IG); 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(1) (USCP IG); 2 U.S.C. §185(c)(1)(a) (LOC IG); 41 U.S.C. §3902(a) (GPO IG); 31 U.S.C. §705(b)(1) (GAO IG). Special IGs are not explicitly required to be appointed “without regard to political affiliation.” 48 2 U.S.C. §1808(c)(1)(A) (AOC IG); 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(1) (USCP IG). For a summary of appointment methods for the five legislative branch IGs, see CRS Insight IN11763, Appointment Methods for Legislative Branch Inspectors General, by Ben Wilhelm.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 18 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Table 5. Appointment Methods for Statutory IGs

President Nominates,

Agency or Entity

President

Authorizing Statutes

Senate Confirms

Head Appoints

Appoints

Total

Inspector General Act of

33a

31b

0

64

1978, as amended

Other statutes

4c

5d

1e

10

Total

37

36

1

74

permanent IGs in the legislative branch.42

|

Authorizing Statutes |

President Nominates, Senate Confirms |

Agency or Entity Head Appoints |

President Appoints |

Total |

|

Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended |

|

|

0 |

65 |

|

Other statutes |

|

|

|

9 |

|

Total |

36 |

36 |

1 |

74 |

Source: CRS analysis of authorizing statutes for the listed IGs. The table does not include statutory IGs that have been abolished.

a. Includes all establishment IGs. See 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§3 and 12(2).

b. Includes all DFE IGs. See 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G(c).

c. Includes the IGs for the Central Intelligence Agency, the Intelligence Community, and the Special IG for the

Troubled Asset Relief Program, and the Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery. See, respectively, 50 U.S.C. §3517(b)(1), 50 U.S.C. §3033(c)(1), and 12 U.S.C. §5231(b)(1).

d. , and 15 U.S.C. §9053(b)(1).

d. Includes the IGs for the Architect of the Capitol, Government Accountability Office, Government

Publishing Office, Library of Congress, and the U.S. Capitol Police. See, respectively, 2 U.S.C. §1808(c)(1)(A), 31 U.S.C. §705(b)(1), 44 U.S.C. §3902(a), 2 U.S.C. §185(c)(1)(A), and 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(1).

e.

e. Includes the Special IG for Afghanistan Reconstruction. See 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G note.

Removal Method

IGs can be removed or transferred to another position under one of two different methods: (1) by the President, or (2) by the head of the affiliated federal entity. Establishment, special, and other permanent IGs in the executive branch are removable or transferrable by the President.4349 In contrast, DFE IGs and other permanent IGs in the legislative branch are removable or transferrable by the heads of their affiliated entities.4450 Additional procedures are required to remove or transfer certain IGs as follows:

-

DFE IG headed by a board, committee, or commission. Removal or transfer

upon written concurrence of a two-thirds majority of the members of the board, committee, or commission.

45 - 51

U.S. Postal Service (USPS) IG. Removal upon written concurrence of at least

seven out of nine postal governors and only

"“for cause"” (e.g., malfeasance or neglect of duty).46 - 52

USCP IG. Removal upon a

"“unanimous vote"” of all voting members on the Capitol Police Board.47

53

In most cases, Congress must receive advanced notice of an IG'’s removal or transfer. The removal authority must communicate to both houses of Congress, in writing, the reasons for the IG'

49 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§3(b) (establishment IGs); 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G note (SIGAR); 12 U.S.C. §5231(b)(4) (SIGTARP); 50 U.S.C. §3033(c)(4) (IC IG); 50 U.S.C. §3517(b)(6) (CIA IG).

50 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G(e) (DFE IGs); 2 U.S.C. §1808(c)(2) (AOC IG); 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(3) (USCP IG); 31 U.S.C. §705(b)(2) (GAO IG); 44 U.S.C. §3902(b) (GPO IG); 2 U.S.C. §185(c)(2) (LOC IG).

51 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G(e)(1). 52 39 U.S.C. §202(e). 53 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(3).

Congressional Research Service

13

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

IG’s removal or transfer 30 days in advance for establishment, DFE, and special IGs—representing 6768 out of 74 IGs.48

54

Advanced notice requirements for removal vary across other permanent IGs. Authorizing statutes for other permanent IGs in the executive branch require the same 30-day advanced written notice of removal but only to the congressional intelligence committees. Authorizing statutes for the other permanent IGs in the legislative branch do not explicitly require advanced notice and instead require written communication to Congress explaining the reason for removal.49 55 Advanced notice to Congress is not explicitly required for transfers of other permanent IGs.

Term Limits

What Constitutes Sufficient Notice?

The Inspector General Reform Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-409) established the requirement that, prior to the removal or transfer of an establishment or designated federal entity IG, the President or head of the affiliated federal entity must “communicate in writing the reasons for any such removal or transfer to both Houses of Congress not later than 30 days before the removal or transfer” (P.L. 110-409 §3; 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§3(b) and 8G(e)(2)). While the timing and formal elements of the provision are clear, there has been disagreement regarding the level of detail the President’s notice must provide to meet the requirement for providing “reasons” for the removal or transfer of an IG. Presidents have availed themselves of this authority three times. In 2009, President Barack Obama removed the IG for the Corporation for National and Community Service, Gerald Walpin. In 2020, President Donald Trump removed the IG for the Intelligence Community, Michael Atkinson, and the IG for the Department of State, Steve Linick. In each of these instances, Presidents Obama and Trump asserted that they had met the statutory notice requirement by issuing letters to Congress indicating that they were removing the IGs due to a “lack of confidence” and placing each IG on administrative leave during the 30-day notice period.56 Some Members of Congress and others have questioned the usefulness and sufficiency of these notifications, and Walpin challenged his removal in court based on these statutory requirements. However, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia found in that case that President Obama met the minimum requirements of Section 3(b) of the IG Act (Walpin v. Corporation for National and Community Service, 630 F.3d 184 (2011)). For further information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10476, Presidential Removal of IGs Under the Inspector General Act, by Todd Garvey.

Term Limits All but two statutory IGs may serve indefinitely. The USPS and USCP IGs, however, are subject to term limits. The USPS IG is appointed to a seven-year term and can be reappointed for an unlimited number of terms.57 The USCP IG is appointed to serve a five-year term for up to three terms (15 years total).50

58

54 The 68 IGs include establishment, DFE, and special IGs. 55 U.S.C. §1808(c)(2) (AOC IG); 31 U.S.C. §705(b)(2) (GAO IG); 44 U.S.C. §3902(b) (GPO IG); 2 U.S.C. §185(c)(2) (LOC IG); 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(3) (USCP IG).

56 See letter from Barack Obama, President of the United States, to Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the United States House or Representatives, June 11, 2009, at https://web.archive.org/web/20121010171826/http://a.abcnews.go.com/images/Politics/Obama_letter_%20to_Pelosi.pdf; letter from Donald Trump, President of the United States, to the Senate Committee on Intelligence, April 3, 2020, at https://web.archive.org/web/20211016003538/https://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000171-4308-d6b1-a3f1-c7d8ee3f0000; and letter from Donald Trump, President of the United States, to Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, May 15, 2020, at https://web.archive.org/web/20220131155450/https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Linick-Letter-Trump-May.pdf.

57 39 U.S.C. §202(e)(2)(a). 58 2 U.S.C. §1909(b)(2).

Congressional Research Service

14

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Transparency of Budget Formulation and Proposals Transparency of Budget Formulation and Proposals

Establishment, DFE, and other permanent IGs in the executive branch are required to develop annual budget estimates that are distinct from the budgets of their affiliated entities. Further, such budget estimates must include some transparency into the requested amounts before agency heads and the President can modify them.5159 The budget formulation and submission process for the aforementioned IG types includes the following key steps:

-

IG budget estimate to affiliated agency head. The IG submits an annual budget

estimate for its office to the affiliated entity head. The estimate must include (1) the aggregate amount for the IG

'’s total operations, (2) a subtotal amount for training needs, and (3) resources necessary to support CIGIE. - 60

Agency budget request to President. The affiliated entity head compiles and

submits an aggregated budget request for the IG to the President. The budget request includes any comments from the IG regarding

theythe entity head'’s proposal. -

President

'’s annual budget to Congress. The President submits an annual budget to Congress. The budget submission must include (1) the IG'’s original budget that was transmitted to the entity head, (2) the President'’s requested amount for the IG, (3) the amount requested by the President for training of IGs, and (4) any comments from the IG if the President'’s amount would"“substantiallyinhibit"inhibit” the IG from performing his or her duties.52

61

This process arguably provides a level ofIGs at least some budgetary independence from their affiliated entities, particularly by enabling Congress to perceive differences between the budgetary perspectives of IGs and affiliated agencies or the President. Governing statutory provisions outline the following submission process, although it is unclear whether every IG interprets the statute similarly. Notably, one congressional committee investigation questioned whether the President was consistently following the IG Act'’s requirements for transparency of IG budget formulation.53

62

Treatment of budget estimates for other permanent IGs in the legislative branch varies. The authorizing statues for the USCP, LOC, and GAO IGs do not explicitly require the IGs to develop budget estimates that are distinct from the affiliated entity'’s budget request.5463 The extent to which these budget estimate requirements apply to the special IGs and the GPO and AOC IGs is unclear.55 Some of these IGs have historically developed separate budget estimates.56 In FY2018 and FY2019, the House and Senate Committees on Appropriation have called for legislative branch agency budget requests to include separate sections for IG budget estimates.57

Appropriations

59 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§6(g) and 8G(g)(1) (establishment and DFE IGs); 50 U.S.C. §3033(n) (IC IG); and 50 U.S.C. §3517(f)(2) (CIA IG).

60 Congress has appropriated funds directly to CIGIE’s Inspector General Council Fund for specific purposes. For instance, Congress has provided funding in recent years to support the oversight.gov website. See, for example, Division D, Section 633 of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-6) appropriating $2 million to the Inspector General Council Fund.

61 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§6(g) and 8G(g)(1) (establishment and DFE IGs); 50 U.S.C. §3033(n) (IC IG); and 50 U.S.C. §3517(f)(2) (CIA IG).

62 U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Undermining Independent Oversight, minority staff report, no date [released August 15, 2018], p. 2, at https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/REPORT-Undermining%20Independent%20Oversight-The%20President's%20Fiscal%20Year%202019%20Budget%20Does%20Not%20Adequately%20Support%20Federal%20Inspectors%20General.pdf.

63 Authorizing statutes for the USCP, LOC, and GAO IGs do not incorporate the provision in Section 6 that contains these budgetary requirements, nor do they include language establishing similar requirements. See 2 U.S.C. §1909(d)(1) (USCP IG); 2 U.S.C. §185(d)(1) (LOC IG); and 31 U.S.C. §705 (GAO IG).

Congressional Research Service

15

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

these budget estimate requirements apply to the special IGs and the GPO and AOC IGs is unclear.64 Some of these IGs have historically developed separate budget estimates.65

Appropriations Federal laws explicitly provide establishment IGs and other permanent IGs in the executive branch a separate appropriations account for their respective offices.5866 This requirement provides an additional level of budgetary independence from the affiliated entity by preventing attempts to limit, reallocate, or otherwise reduce IG funding once it has been specified in law, except as provided through established transfer and reprogramming procedures and related interactions between agencies and the appropriations committees.59

67

Appropriations for DFE IGs and other permanent IGs in the legislative branch, in contrast, are part of the affiliated entity'’s appropriations account. Absent statutory separation of a budget account, the appropriations may be more susceptible to some reallocation of funds, although other protections may apply.6068 Authorizing statutes for special IGs do not explicitly require separate appropriations accounts, although in practice the President may propose, and Congress may fund, special IGs through separately listed accounts.61

69 Reporting Requirements

Statutory IGs have various reporting obligations to Congress, the Attorney General, agency heads, and the public. Some reporting requirements are periodic, while others are triggered by a specific event. The subsections below highlight some of the required reports for statutory IGs.62

70 Semiannual Report

The IG Act requires establishment and DFE IGs to issue semiannual reports that summarize the activities of their offices. For example, the reports must include a summary of each audit and inspection or evaluation report issued before the start of the reporting period that includes "“outstanding unimplemented recommendations"” and the aggregate potential cost savings of those recommendations.63

64 Authorizing statutes for special IGs and the AOC and GPO IGs incorporate portions of Section 6 of the IG Act. However, it is unclear whether this incorporation extends the requirements to those IGs. See 2 U.S.C. §1808(d)(1) (AOC IG) and 44 U.S.C. §3903(a) (GPO IG); 12 U.S.C. §5231(d)(1) (SIGTARP); and 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G note (SIGAR).

65 See, for example, the SIGTARP FY2022 budget justification at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/266/09.-SIGTARP-FY-2022-CJ.pdf and the LOC FY2021 budget justification at https://www.loc.gov/static/portals/about/reports-and-budgets/documents/budgets/fy2022.pdf#page=109.

66 31 U.S.C. §1105(a)(25); 50 U.S.C. §3517(f)(1) (CIA IG); 50 U.S.C. §3033(m) (IC IG). 67 For more information on reprogramming and transfers, see CRS Report R43098, Transfer and Reprogramming of Appropriations: An Overview of Authorities, Limitations, and Procedures, by Michelle D. Christensen.

68 For example, appropriations committees may choose to allocate funding to an IG in ways that would require advance notification of any attempt by an affiliated entity head to reprogram funds away from the IG to another purpose.

69 For example, the President’s FY2022 budget submission included a separate account for SIGTARP. See U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2022, Appendix, pp. 1025-26, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/tre_fy22.pdf.

70 Federal laws sometimes assign one-time or periodic reporting requirements on a specific policy area or subject. These requirements are beyond the scope of this report.

Congressional Research Service

16

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

recommendations.71 The IG Act further requires DFE and establishment IGs to make semiannual reports available to the affiliated entity head, Congress, and the public, as follows:

-

The IG submits report to the affiliated entity head by April 30 and October 31

each year.

-

The affiliated entity head submits the report to the appropriate congressional

committees within 30 days of receiving it. The report must remain unaltered, but it may

it caninclude additional comments from the agency head. -

The affiliated entity head makes the report available to the public within 60 days

of receiving it.

64

72

Other permanent IGs must also issue semiannual reports, though required content can vary by IG.73IG.65 For example, the semiannual report for the IC IG must include comparatively less information on OIG activities than establishment and DFE IGs. Further, the IC IG has an additional reporting requirement to certify whether the IG has had "“full and direct access to all information"information” relevant to IG functions.6674 Special IGs are required to issue quarterly reports rather than semiannual reports, which must include a "“detailed statement"” of obligations, expenditures, and revenues associated with the programs, funds, and activities that they oversee.67

75 Seven-Day Letter

Establishment, DFE, and most other permanent IGs (five out of seven) are required to immediately report to their affiliated entity heads any "“particularly serious or flagrant problems, abuses or deficiencies relating to the administration of programs and operations"” at their affiliated entities. The affiliated entity head must transmit the report unaltered to Congress within seven calendar days.6876 This type of report is commonly referred to as the "“seven-day letter."” Authorizing statutes for the USCP and GAO IGs do not explicitly require issuance of seven-day letters, but they may do so in practice.6977 The extent to which such requirements apply to special IGs is unclear.70

78

71 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §5(a)(10). 72 Ibid., at §5(b). 73 Authorizing statutes for other permanent IGs in the legislative branch (except the GAO IG) incorporate portions of Section 5 of the IG Act, which require IGs to issue semiannual reports. However, it is unclear whether this incorporation extends all elements of the semiannual report required by the IG Act to these IGs. See 2 U.S.C. §1808(d)(1) (AOC IG); 2 U.S.C. §1909(c)(2) (USCP IG); 2 U.S.C. §185(d)(1) (LOC IG); and 44 U.S.C. §3903(a) (GPO IG). Authorizing statutes for the GAO IG and other permanent IGs in the executive branch do not incorporate Section 5 but establish separate semiannual reporting requirements. See 31 U.S.C. §705(e) (GAO IG); 50 U.S.C. §3033(k)(1) (IC IG); 50 U.S.C. §3517(d)(1) (CIA IG).

74 50 U.S.C. §3033(k)(1)(b)(v). A similar requirement applies to the CIA IG. See 50 U.S.C. §3517(d)(1)(D). 75 12 U.S.C. §5231(i)(1) (SIGTARP); 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G note (SIGAR); and 15 U.S.C. §9053(f)(1) (SIGPR).

76 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §§5(d) and 8G(g)(1) (establishment and DFE IGs); 50 U.S.C. §3033(k)(2) (IG IC); and 50 U.S.C. §3517(d)(2) (CIA IG). Authorizing statutes for the AOC, LOC, and GPO IGs clearly incorporate portions of Section 5 of the IG Act pertaining to the seven-day letter. See 2 U.S.C. §1808(d)(1) (AOC IG); 2 U.S.C. 185(d)(1) (LOC IG); and 44 U.S.C. §3903(a) (GPO IG).

77 Authorizing statutes for the USCP and GAO IGs do not incorporate portions of Section 5 of the IG Act requiring the seven-day letter, nor do they establish similar requirements. See 2 U.S.C. §1909 (USCP IG); 31 U.S.C. §705 (GAO IG).

78 Authorizing statutes for SIGAR, SIGTARP, and SIGPR do not explicitly incorporate Section 5 of the IG Act, nor do they establish similar requirements. However, their authorizing statutes state that the IGs “shall also have the

Congressional Research Service

17

Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A Primer

Top Management and Performance Challenges

Top Management and Performance Challenges

The Reports Consolidation Act of 2000 requires IGs for executive branch agencies to annually identify the "“most serious management and performance challenges"” facing their affiliated agencies and to track the agency'’s progress in addressing those challenges.7179 These are commonly referred to as top management and performance challenges (TMPCs). A covered IG must submit the statement to the affiliated entity head 30 days in advance of the entity head'’s submission of the Annual Financial Report (AFR) or Performance and Accountability Report (PAR). The agency head must include the statement unaltered (but with any comments) in the entity'’s AFR or PAR. IGs for government corporations in the executive branch, as well as special IGs and other permanent IGs in the legislative branch, are not explicitly required to identify TMPCs.72 80 However, some of these IGs have elected to do so.73 In April 2018, CIGIE released its first ever report on 81 CIGIE has periodically released reports on common TMPCs facing multiple agencies.74

82 Transparency of IG Reports and Recommendations

Federal laws require varied levels of transparency for IG reports and related recommendations for corrective action. The IG Act requires the following for establishment and DFE IGs:

-

Public availability of semiannual reports. Semiannual reports must be made

available to the public

"“upon request and at a reasonable cost."75 - ”83

Audits and inspection or evaluation reports on OIG websites. Audit,

inspection, and evaluation reports must be posted on the OIG

'’s website within three days of submitting final versions of the report to the affiliated entity head.76 - 84

Documents containing recommendations on OIG websites. Any

"“document making a recommendation for corrective action"” must be posted on the OIG's’s website within three days of submitting the final recommendation to the affiliated entity head.77

85 Application of these transparency requirements varies among other permanent IGs as follows:

-

Semiannual reports. Four out of five other permanent IGs in the legislative

branch are statutorily required to make semiannual reports available to the public in the same manner specified in the IG Act.

7886 The GAO IG and other permanent responsibilities and duties of inspectors general under the Inspector General Act of 1978,” which may include the seven-day letter. See 12 U.S.C. §5231(c)(3) (SIGTARP) and 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act), §8G note (SIGAR). 79 31 U.S.C. §3516(d). In this context, executive branch agency is defined as a “department, agency, or instrumentality in the executive branch of the United States Government,” but it excludes government corporations defined in 31 U.S.C. §9101. See 31 U.S.C. §102 and 31 U.S.C. §3501. 80 Ibid. 31 U.S.C. §9101 lists “Government corporations” that are exempt from issuing TMPCs. 81 For example, SIGTARP has identified TMPCs since at least Q4 of FY2017. The reports are accessible at https://www.sigtarp.gov/Pages/Reports-Testimony-Home.aspx. 82 CIGIE, Top Management and Performance Challenges Facing Multiple Federal Agencies, February 2021, at https://www.ignet.gov/sites/default/files/untracked/TMPC_report_02022021.pdf. 83 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act) §5(c). 84 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act) §8M(b). 85 5 U.S.C. Appendix (IG Act) §4(e)(1)(C). 86 Authorizing statutes for the AOC, GPO, LOC, and UCSP IGs clearly incorporate portions of Section 5 pertaining to public availability of semiannual reports. See 2 U.S.C. §1808(d)(1) (AOC IG); 44 U.S.C. §3903(a) (GPO IG); 2 U.S.C. §185(d)(1) (LOC IG); and 2 U.S.C. §1909(c) (USCP IG). Congressional Research Service 18 Statutory Inspectors General in the Federal Government: A PrimerThe GAO IG and other permanentIGs in the executive branch, by contrast, are not explicitly required to make the reports publicly available.79 - 87

Audits and inspections or evaluation reports on OIG websites. Authorizing

statutes for all seven other permanent IGs do not explicitly require the IGs to post individual audit, inspection, or evaluation reports on their respective OIG websites.

80 - 88