Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

Changes from December 13, 2018 to July 13, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—

A Discussion for Policymakers

Contents

- Public Perception of the Police

- Federalism and Congressional Control over State and Local Law Enforcement Policy

- Overview of Federalism

- Federalism and State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies

- Federal Efforts to Collect Data on Law Enforcement Officers' Use of Force

- Uniform Crime Reports

- The Federal Bureau of Investigation's Use of Force Data Collection

- Contacts between the Police and the Public

- Death in Custody Reporting Program

- Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Authority for DOJ to Investigate Law Enforcement Misconduct

- What Role Might the Department of Justice Play in Improving Police-Community Relations?

- DOJ as Law Enforcer

- DOJ as Policy Leader

- DOJ as Convener

- DOJ as Funder

- Policy Options for Congress

- Conditions on Federal Funding

- Expanding Efforts to Collect Data on Police Use of Force

- Promoting the Use of Body-Worn Cameras

- Facilitating the Investigation and Prosecution of Excessive Force

- Promoting Community Policing

- Non-legislative Measures

Summary

Several high-profile incidents where the police have apparently used excessive force against citizens have generated interest in July 13, 2020

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

R43904

SUMMARY

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—

A Discussion for Policymakers

Several high-profile incidents where there have been complaints of the use of excessive force

against individuals and subsequent backlash in the form of civil unrest have generated interest in

what role Congress could play in facilitating efforts to build trust between the police and the

people they serve. This report provides a briefan overview of the federal government'’s role in local

police-community relations.

Public

According to polling conducted by Gallup, public confidence in the police declined in 2014 and

2015 after several high-profile incidents in which men of color were killed during confrontations

with the police. Confidence in the police has rebounded in recent years and is now back to the historical average. However, certain groups, such as Hispanics, blacks, people under the age of 35, and individuals with liberal political leanings rebounded back to the historical average in 2017 before

declining again in 2018 and 2019. (Gallup data are not yet available for 2020). However, certain

groups, such as people of color, people age 34 or younger, and individuals who identify as liberal

say they have less confidence in the police than whites, people over the age of 35, and people

with conservative political leanings.

If Congress concludes that low public opinion

Some observers believe that a decline in public trust of the police is at least partially attributable to police policies and practices, it may decide to address state and local law enforcement policies and practices it believes erode public trust in the police. Federalism limits the amount of influence Congress can have over state and local law enforcement policy. Regardless, the federal government might choose to address issues related to promoting better police-community

to state and local police policies and practices. Federalism limits the amount of influence

Congress can have over state and local law enforcement policy. General policing powers are the

purview of states, but Congress can try to influence state and local policing policies by attaching

conditions to grant funds.

R43904

July 13, 2020

Nathan James,

Coordinator

Analyst in Crime Policy

Kristin Finklea

Specialist in Domestic

Security

Whitney K. Novak

Legislative Attorney

Joanna R. Lampe

Legislative Attorney

April J. Anderson

Legislative Attorney

Kavya Sekar

Analyst in Health Policy

The federal government might also choose to address issues related to police-community

relations and accountability through (1) federal efforts to collect and disseminate data on the use

of force by police, (2) statutes that allow the federal government to investigate instances of

alleged police misconduct, and (3) the influence the Department of Justice (DOJ) has on state and

local policing through its role as a public interest law enforcer, policy leader, convener, and funder of state and local law enforcement agencies.

and convener of representatives from law

enforcement agencies and local communities to discuss policing issues.

There are several options policymakers might consider should they choose to play a role in facilitating better police- community relations, including the following:

-

placing conditions on federal funding to encourage law enforcement agencies to adopt policies that

expanding promoting efforts to collectcomprehensivedata on the use of force by law enforcementofficers;- , including evaluating potential

overlap between DOJ programs that currently collect the data;

providing grants to law enforcement agencies so they

couldcan purchase body-worn cameras for their officers; -

funding Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) grants so law enforcement agencies can hire more

officers to engage in community policing activities; and

using the influence of congressional authority to affect the direction of national criminal justice p olicy.

taking steps to facilitate investigations and prosecutions of excessive force by amending 18 U.S.C. Section

prosecutionsprosecution, enhance DOJ civil enforcement under 34 U.S.C. Section 12601, or place conditions on federal funds to promote the use of special prosecutors at thestate level; - funding Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) hiring grants so law enforcement agencies could hire more officers to engage in community policing activities; and

- using the influence of congressional authority to affect the direction of national criminal justice policy.

Several high-profile incidents where police officers have been involved in the deaths of citizens1

individuals have reinvigorated a discussion about how the police use force against

minorities and the tension that exists between police officers2 1 and minority communities.

The national debate about how police use force and police-community relations might generate

interest among policymakers about what role Congress could play in facilitating efforts to build

trust between the police and the people they serve, as well as police accountability for any

excessive use of force.

S

The report starts with an overview of data on public opinion of the police. It then provides a brief

discussion of federalism and why Congress does not have the authority to directly change state

and local law enforcement practices. Next, the report reviews federal efforts to collect data on law

enforcement agencies'’ use of force and federal authority to investigate instances of police

misconduct. This is followed by a review of what role DOJ might be able to play in facilitating

improvements in police-community relations or making changes in state and local law

enforcement agencies'’ policies. The report concludes with policy options for Congress to consider

should policymakers decide to exert some influence on state and local law enforcement agencies' policy.

’ policy. The Parameters of This Report

This report provides a brief overview of police-community relations and how policymakers might be able to |

Public Perception of the Police

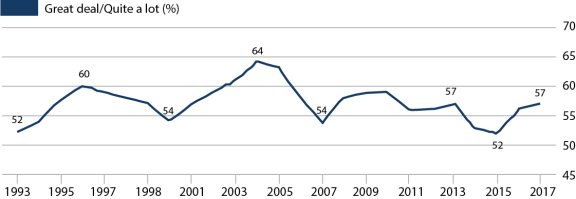

Gallup, whose polling tracks confidence in a variety of institutions, found that the public's level of confidence in police is back to its historical norm after a decrease in 2014 and 201553% of Americans

said they had a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the police in 2019 (see Figure 1).3 In 2017, 57% of Americans said they had a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police, which matched the 25-year average for Gallup polling. Fifty-seven percent of Americans reported that they had a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police in 2013, but confidence decreased to 53% in 2014, and decreased again to 52% in 2015, which was a historical low in Gallup polling. Even at its nadir in 2015, people still had more confidence in the police than many other institutions.4 Only the military (72%) and small business (70%) had higher percentages of respondents voicing confidence in the respective institutions than the police.5

Confidence in the police varies by race/ethnicity, political ideology, and age (see Table 1). Whites were more likely to say that they have a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police than Hispanics and blacks. In addition, whites' confidence in the police has increased while that of Hispanics and blacks has decreased. Variability in confidence is also evidenced among people who identify as conservative, moderate, and liberal. Conservatives are more likely than liberals and moderates to have confidence in the police, and their confidence has increased in recent years while that of moderates and liberals has decreased. In addition, a smaller proportion of people age 18-34 said they were confident in the police compared to people age 35-54 and people 55 and older, with the 55 and older group having the greatest proportion of people saying that they had a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police.

of confidence in the police. Table 1. Confidence in the Police, by Demographic Group

, 2019

Percentage who have a "report a “great deal"” or "“quite a lot"” of confidence in the police

Demographic Group

Race

White

59%

Non-white

40%

Gender

Male

56%

Female

49%

Political Ideology

Liberal

33%

Moderate

46%

Conservative

75%

Congressional Research Service

2

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

Demographic Group

Age

18-34

39%

35-54

53%

55 or older

63%

Education

High school grad or less

48%

Some college

54%

College grad

55%

Source: CRS presentation of data from Justin McCarthy, “U.S. Confidence in Organized Religion Remains Low,”

Gallup, July 8, 2019; full data are linked in the article at https://news.gallup.com/file/poll/260033/

190708ConfidenceInstitutions.pdf.

A poll conducted by National Public Radio, the Public Broadcasting Service, and the Maris t

Institute for Public Opinion from June 2 to June 3, 2020 (which was after George Floyd’s death in

Minneapolis) found that 63% of respondents have a great deal or a fair amount of confidence that

the police treat blacks and whites equally. 4 In comparison, 71% of respondents had a great deal or

fair amount of confidence that the police treat blacks and whites equally when they were asked a

similar question in December 2014. Perceptions of how the police treat blacks and whites varies

by race/ethnicity. In the June 2020 poll, 70% of white respondents had a great deal or fair amount

of confidence that the police treat blacks and whites equally while 31% of African Americans and

63% of Latinos had the same amount of confidence that the police treat blacks and whites

similarly.

Federalism and Congressional Influence over State

and Local Law Enforcement Policy

Policymakers may have an interest in legislation that aims to help increase trust between state and

local police and certain communities. However, federalism principles limit the influence

Congress has of confidence in the police

|

Demographic Group |

2012-2014 |

2015-2017 |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

||

|

Hispanic |

59% |

45% |

|

Black |

35% |

30% |

|

White |

58% |

61% |

|

Political Ideology |

||

|

Liberal |

51% |

39% |

|

Moderate |

56% |

53% |

|

Conservative |

59% |

67% |

|

Age |

||

|

18-34 |

56% |

44% |

|

35-54 |

53% |

54% |

|

55 or older |

58% |

63% |

Source: CRS presentation of data from Jim Norman, "Confidence in Police Back at Historical Average," Gallup, July 10, 2017.

Federalism and Congressional Control over State and Local Law Enforcement Policy

Policymakers may have an interest in trying to help increase trust between the police and certain communities, particularly in urban areas. Policymakers may seek to increase law enforcement agencies' accountability for any excessive use of force and address state and local law enforcement policies they believe contribute to the lack of public trust in police. However, the United States' federalized system of government places limits on the influence Congress can have over state and local law enforcement policies.

over state and local law enforcement policies. Overview of Federalism

Federalism describes the intergovernmental relationships between and among federal, state, and

local governments, with the federal government having primary authority in some areas and state

and local governments having primary authority in other areas. 5 The Constitution establishes a

“system of dual sovereignty between the States and the Federal Government.”6 Under the Tenth

Amendment, “[t]he powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited

4

Polling data available at http://maristpoll.marist.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/NPR_PBS-NewsHour_Marist Poll_USA-NOS-and-T ables_2006041039.pdf.

5

James Q. Wilson and John J. Dilulio, Jr, American Government Institutions and Policies (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath

and Company, 1995), p. A-49.

6

Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452, 457 (1991).

Congressional Research Service

3

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”7 Thus, a state

generally has broad authority to enact legislation, including to regulate the state’s and its

localities’ law enforcement approaches.8 In contrast, Congress may only enact legislation under a

specific power that is enumerated in the Constitution and cannot use its power to intrude

impermissibly on the sovereign powers of the states. 9 In this vein, the Supreme Court has

recognized that there are certain subjects that are largely of a local concern where states

“historically have been sovereign,” such as issues related to the family, crime, and education. 10

Because of these principles, the Supreme Court has recognized various limitations on Congress’s

power to legislate in areas that fall within a state’s purview, observing that congressional power is

“subject to outer limits,” and that Congress must take care not to “effectually obliterate the

distinction between what is national and what is local.”11 In addition, under the anticommandeering doctrine, Congress is prohibited from passing laws requiring states or localities

to adopt or enforce federal policies. 12 Although these principles constrain Congress’s power, it

can rely on its enumerated powers to regulate in areas it could not otherwise reach. 13 The

spending power and Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment are two of the most relevant

authorities that Congress has used in the past to address local law enforcement issues.

Spending Power and Regulating Law Enforcement Activities

The Spending Clause empowers Congress to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises,

to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United

States.”14 The Supreme Court has held that incident to the spending power, Congress may further

its policy objectives by attaching conditions on the receipt of federal funds. 15 These conditions

often involve compliance with statutory or administrative directives and can apply to any entity

receiving federal funds, including states and localities. In South Dakota v. Dole, for example, the

Supreme Court upheld as a valid exercise of Congress’s spending power a statute that conditioned

the grant of federal highway funds to any state upon that state prohibiting the legal purchase or

possession of alcohol by individuals less than 21 years old. 16

There are, however, four limitations on Congress’s authority to attach conditions to federal

funds. 17 First, a funding condition must be “in pursuit of the general welfare.”18 However, courts

afford Congress substantial deference in determining what expenditures are “intended to serve

7

U.S. CONST. amend. X.

8

See Bond v. United States, 572 U.S. 844, 854 (2014).

Murphy v. Nat'l Collegiate Athletic Ass'n, 138 S.Ct. 1461, 1467 (2018) (“The Constitution confers on Congress not

plenary legislative power but only certain enumerated powers.”); United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598, 607 (2000)

(“Every law enacted by Congress must be based on one or more of its powers enumerated in the Constitution.”).

10 United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549, 564 (1995).

9

11

Ibid. at 557.

12

New York v. United States, 505 U.S. 144, 188 (1992).

South Dakota v. Dole, 483 U.S. 203, 207 (1987) (“[O] bjectives not thought to be within Article I’s enumerated

legislative fields ... may nevertheless be attained through the use of the spending power and the conditional grant of

federal funds.”) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

13

14

U.S. CONST. art. I, §8, cl. 1.

15

Dole, 483 U.S. at 206.

Ibid. at 211-212.

16

17

See CRS Report R45323, Federalism -Based Limitations on Congressional Power: An Overview, pp. 28-35.

18

Dole, 483 U.S. at 207.

Congressional Research Service

4

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

general public purposes.”19 Second, if Congress intends to place conditions on federal funds, it

must do so “unambiguously” so that states can knowingly choose whether or not to accept the

funds. 20 Third, conditions on federal funding must be related or “germane” to “the federal interest

in particular national projects or programs.”21 Fourth, other constitutional provisions may bar the

conditions placed on the grant of federal funds. For instance, Congress may not condition a

monetary grant on “discriminatory state action or the infliction of cruel and unusual

punishment.”22 Relatedly, conditions on federal funding are unconstitutional when they become

coercive to the point that “pressure turns into compulsion” or commandeering. 23 For example, in

National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court held that a

provision in the Affordable Care Act that withheld all Medicaid grants from any state that refused

to accept expanded Medicaid funding was unconstitutionally coercive because it threatened to

terminate “significant independent grants” that were already provided to the states. 24

Courts have rarely used these spending power limitations to invalidate conditions placed on the

receipt of federal funds. 25 NFIB remains the only instance in the modern era of the Supreme Court

invalidating an exercise of the congressional spending power. 26 Post-NFIB Spending Clause

challenges have largely been unsuccessful in the lower courts.27 As a result, in practice Congress

has faced relatively few limitations on its use of the spending power to impose conditions on

federal funds to further its policy objectives.

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment and Regulating Law

Enforcement Activities

The Fourteenth Amendment, in relevant part, provides that no state shall “deprive any person of

life, liberty, or property, without due process of law ” or “deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.”28 The Supreme Court has interpreted the substantive component

of the Due Process Clause as incorporating against state actors nearly all the rights found in the

19

Ibid.

20

Ibid.

21

Ibid.

Ibid. at 210.

22

23

Ibid. at 211.

24

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519, 580 (2012).

Aziz Z. Huq, Tiers of Scrutiny in Enumerated Powers Jurisprudence, 80 U. CHI. L. REV. 575, 599 (2013) (observing

that the Supreme Court has generally “declined to enforce ‘direct’ limits on the Spending Power”); see also Jonathan H.

Adler and Nathaniel Stewart , Is the Clean Air Act Unconstitutional? Coercion, Cooperative Federalism and

Conditional Spending After NFIB v. Sebelius, 43 ECOLOGY L.Q. 671, 700 (2016); (arguing that the “ NFIB plurality did

not open a new line of attack against spending power statutes.”).

25

26

Andrew B. Coan, Judicial Capacity and the Conditional Spending Paradox, 2013 W IS. L. REV. 339, 346 (2013)

(“Prior to NFIB, Butler was the only time the Supreme Court ever invalidated an exercise of the congressional spending

power.”).

27

See, for example, Miss. Comm'n on Envtl. Quality v. EPA, 790 F.3d 138, 175 (D.C. Cir. 2015) (rejecting the

plaintiff’s position that the “Clean Air Act’s sanctions for noncompliant states impose such a steep price that State

officials effectively have no choice but to comply”); T exas v. EPA, 726 F.3d 180, 197 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (rejecting the

argument that the challenged federal law was of the “same magnitude and nature as the Medicaid expansion provision

[at issue in NFIB] that would strip over 10 percent of a State’s overall budget”) (internal citations and quotations

omitted); T ennessee v. United States Dep’t of State, 329 F. Supp. 3d 597, 626 -29 (W.D. T enn. 2018) (rejecting the

argument that the threatened loss of federal Medicaid funding to coerce support of the federal re fugee program was

comparable to the program at issue in NFIB).

28

U.S. CONST. amend. XIV.

Congressional Research Service

5

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

Bill of Rights, including those that pertain to criminal procedure and regulate the conduct of the

police. 29 In turn, Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment grants Congress the power to enforce

the Amendment through “appropriate legislation.”30 Section 5’s “positive grant of legislative

power” authorizes Congress to both deter and remedy constitutional violations; and in doing so,

Congress may prohibit otherwise constitutional conduct that intrudes into “legislative spheres of

autonomy previously reserved to the States.”31 The Section 5 enforcement power (and the

enforcement powers found in the Thirteenth 32 and Fifteenth33 Amendments) has been used to, for

example, ban the use of literacy tests 34 in state and national elections and abolish “all badges and

incidents of slavery”35 by banning racial discrimination in the acquisition of real and personal

property. Congress has also used its Section 5 power 36 to provide remedies for the deprivation of

constitutional rights. For example, 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 provides a private cause of action for

individuals claiming that their constitutional rights were violated by state actors acting pursuant

to state law. And 18 U.S.C. Section 242—the current version of which is a product of Congress’s

Section 5 power 37 —imposes criminal liability on state actors who deprive individuals of their

constitutional rights.

While Congress’s Section 5 enforcement power is broad, it is not unlimited. 38 Section 5 allows

Congress to directly enforce constitutional rights through laws like Section 1983 and Section 242;

however, the power does not allow Congress to supplement those rights through prophylactic

legislation that regulates state and local matters without evidence of a history and pattern of past

constitutional violations by the state. 39 And, according to the Supreme Court, when Congress

exercises its Section 5 authority, its response must be congruent and proportional to a

demonstrated harm. 40 Congress may justify the need for Section 5 legislation by establishing a

legislative record that shows “evidence … of a constitutional wrong.”41 For example, in holding

that Congress exceeded its Section 5 authority in enacting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act

(RFRA)—which, in relevant part, supplanted normal First Amendment standards to impose a

heightened standard of review for state government actions that substantially burdened a person’s

religious exercise—the Supreme Court determined that Congress had failed to establish a

widespread pattern of religious discrimination by the states. 42 As a result, RFRA could not be

justified as a remedial measure designed to prevent unconstitutional conduct and was outside of

29

30

T imbs v. Indiana, 139 S.Ct. 682, 687 (2019).

U.S. CONST. amend. XIV, §8.

31

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 US 507, 517–18 (1997).

32

U.S. CONST. amend. XII, §2.

Ibid. amend. XV, §3.

33

34

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112, 118 (1970).

35

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 439 (1968).

36

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 171 (1961).

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 98 (1945).

37

38

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 519 (1997).

39

Northwest Austin Mun. Utility Dist. v. Holder, 557 US 193, 225 (2009).

City of Boerne, 521 U.S. at 510.

40

41

Allen v. Cooper, 140 S.Ct. 994, 1004 (2020).

42

City of Boerne, 521 U.S. at 532.

Congressional Research Service

6

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

Congress’s power over the states.43 Thus, the Court struck down the law in so far as it applied to

the states. 44

As a consequence of this case law, the scope of Congress’s Section 5 power hinges in part on the

scope of the constitutional right that a given law aims to protect. With respect to regulating state

and local police forces, one constitutional right that may be particularly relevant to Congress’s

use of its Section 5 power is the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and

seizures by the government. 45 The Fourth Amendment applies to many situations involving law

enforcement, including when police stop an individual on the street for questioning, 46 conduct

traffic stops,47 or make an arrest.48 Police violate the Fourth Amendment, for example, if they use

excessive force during an investigatory stop or arrest.49 According to the Supreme Court, the

force used by law enforcement during an investigatory stop or arrest violates the constitution

when it is unreasonable considering the facts and circumstances of the case. 50 This analysis

requires a careful balancing of “the nature and quality of the intrusion on the individual’s Fourth

Amendment interests against the importance of the governmental interests alleged to justify the

intrusion.”51 For example, the Supreme Court has held that police use of deadly force against a

fleeing suspect who poses no immediate safety threat is unreasonable in violation of the Fourth

Amendment. 52 Determining whether an act of force is excessive in violation of the Constitution,

however, requires a fact-specific analysis—a certain act may be reasonable under some facts,

while in a different case the same act may amount to excessive force. For example, some courts

have ruled that police use of a chokehold is objectively unreasonable when used against

individuals who are already under restraint and not a danger to others. 53 In other circumstances,

courts have upheld police use of a chokehold as reasonable in instances where an individual was

unrestrained and continued to pose a threat of serious harm. 54

Notwithstanding the limits on how much influence the federal government can have on state and

local law enforcement policy, the federal government does have various tools that might be used

to promote better police-community relations and accountability. These include (1) federal efforts

to collect and disseminate data on the use of force by law enforcement officers; (2) statutes that

allow the federal government to investigate instances of police misconduct; and (3) the influence

DOJ has on state and local law enforcement policies through its role as a public interest law

enforcer, policy leader, and convenerand local governments having primary authority in other areas.6 Scholars have variously described these relationships as being primarily "dual," "cooperative," "creative," "coercive," or, more recently, "fragmented" federalism. Early characterizations of the American system described a dual federalism in which the federal and state governments were equal partners with relatively separate and distinct areas of authority. Scholars argue that American federalism is presently "more chaotic, complex, and contentious than ever before."7 This has led to a fragmented federalism in which states and the federal government simultaneously pursue their own policy priorities, and policy implementation often occurs in a piecemeal, disjointed fashion.8

Federalism and State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies

Under the authority of the Spending Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress may choose to impose conditions on federal grant awards to state and local governments as a way to influence state and local policy.9 As one scholar noted, congressional conditioning of federal grants related to state and local policing under the authority of the Spending Clause has been questioned:

Law enforcement historically has been considered one of these attributes of state sovereignty upon which the federal government cannot easily infringe. Thus, Congress is greatly restricted in the degree to which it can regulate a state's administration of its local law enforcement agencies. Because of this limited power over the states, particularly in areas such as law enforcement, Congress cannot "commandee[r] the legislative processes of the States by directly compelling them to enact and enforce a federal regulatory program. Furthermore, even if Congress has the authority to regulate or prohibit certain acts if it chooses to do so, it cannot force the states "to require or prohibit those acts."10

In contrast, another scholar has suggested that federal grants to law enforcement agencies are a way to encourage police accountability and argued that "federal funds issued to states ... should be conditioned upon the enactment and implementation of police accountability measures aimed at institutional reform."11

That same scholar also suggested that the use of federal grants to state and local law enforcement agencies can encourage a cooperative federalism relationship that entails federal-state collaboration and allows states some flexibility in implementing federal standards while preserving state and local abilities to enhance police accountability.12 Another federalism scholar noted that cooperative federalism was "a pragmatic middle ground between reform and reaction that would not destroy the states but would still lower their salience from constitutionally coordinate polities to more congenial laboratories of democracy and administrators of national policy."13

While there is limited research on the evolving nature of federalism within law enforcement policy, the congressional use of federal grants to state and local law enforcement agencies, and the cooperative federalism that generally exists through their use, suggest that the federalism relationship in this area may be less fragmented than in other policy areas. It is unclear how changes in federal interaction with state and local law enforcement agencies might affect the nature of federalism outside this specific policy area.

Even though there are limits on how much influence Congress and the federal government can have on state and local law enforcement policy, the federal government does currently have some tools that might be used to promote better police-community relations and accountability. These include (1) federal efforts to collect and disseminate data on the use of force by law enforcement officers; (2) statutes that allow the federal government to investigate instances of police misconduct; and (3) the influence DOJ has on state and local law enforcement policies through its role as a public interest law enforcer, policy leader, convener, and funder of law enforcement agencies.

Federal Efforts to Collect Data on Law Enforcement Officers' of law enforcement agencies.

43

Ibid.

44

Ibid. at 536.

U.S. CONST. amend. IV.

45

46

T erry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 9 (1968).

47

Rodriguez v. United States, 575 U.S. 348, 354 (2015).

48

United States v. Watson, 423 U.S. 411, 417 (1976).

Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 394 (1989).

49

50

Ibid. at 396.

51

T ennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1, 7–8 (1985).

Ibid. at 11.

52

53

Coley v. Lucas County, Ohio, 799 F. 3d 530, 540 (6 th Cir. 2015).

54

Williams v. City of Cleveland, Miss., 736 F. 3d 684, 688 (4 th Cir. 2013).

Congressional Research Service

7

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

Federal Efforts to Collect Data on Law Enforcement

Officers’ Use of Force

Use of Force

The high-profile deaths of several members of the public at the hands of police officers has

generated questions about why the federal government does not collect and publish data on the

use of force by law enforcement officers. Former Philadelphia Police Chief Charles Ramsey, one

of the co-chairs of the Obama Administration’s Task Force on 21st21st Century Policing, stated "

“personally, I think [how data on civilian and law enforcement officers'’ deaths are collected]

ought to be pretty much the same. If you don'’t have the data, people think you are hiding

something.... This is something that comes under the header of establishing trust."14”55 It may be that

the lack of reliable data on how often police use force and who is the subject of the use of force

fuels the public'’s mistrust of the police. Without more comprehensive data to provide context in

this area, the public is left to rely on media accounts of excessive force cases for information. The

lack of comprehensive federal data on police-involved deaths led the Washington Post to in 2015 to

start its own database of people who have been shot and killed by the police.15

nationally. 56

The federal government currently has several different programs that collect some data on police-involved shootings and the use of force. However, none of these programs collects data on every use of force incident in the United States.

Uniform Crime Reports

Currently, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), through the Uniform Crime Report (UCR), collects data on justifiable homicides by law enforcement officers.16 It does not collect data on shootings that do not result in a death, nor does it capture data in instances where an officer shoots at a suspect but does not hit him or her. Also, law enforcement agencies participate in the UCR program voluntarily, which means that justifiable homicides by law enforcement agencies may be undercounted.17 One DOJ statistician has stated that "the FBI's justifiable homicides [data] ... [has] significant limitations in terms of coverage and reliability that [are] primarily due to agency participation and measurement issues."18

The Federal Bureau of Investigation'has several data collection efforts that could be used to provide insight

into how the police use force, but these programs are limited by either not collecting data on all

instances where police use force, or by still being in their infancy. The FBI has undertaken an

effort to collect and report more comprehensive data on the use of force by law enforcement

officers through its Use of Force Data Collection program. The Bureau of Justice Assistance

(BJA)57 also started requiring states to submit data to them that is required by the Death in

Custody Reporting Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-242). The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) continues

to periodically collect and report data on non-fatal contacts between the police and the public

through its Police Public Contact Survey, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) collects data on violent deaths due to legal interventions through its National Vital

Statistics and National Violent Death Reporting Systems.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Use of Force Data Collection

The FBI launched its Use of Force Data Collection program on January 1, 2019. The bureau

notes,

Law enforcement use of force has long been a topic of national discussion, but a number

of high-profile cases involving law enforcement use of force have heightened awareness

of these incidents in recent years. However, s Use of Force Data Collection

The FBI notes that "the opportunity to analyze information related

to use-of-force incidents and to have an informed dialogue is hindered by the lack of

nationwide statistics. To address the topic, representatives from major law enforcement

Kevin Johnson, “Panel to Consider T racking of Civilians Killed by Police,” USA Today, December 12, 2014.

T he Washington Post has collected and reported data on police-involved shootings that resulted in death by “culling

local news reports, law enforcement websites and social media, and by monitoring independent databases such as

Killed by Police and Fatal Encounters.” Data on police shooting deaths for the years 2015-2020 can be accessed at

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/investigations/police-shootings-database/. T he Washington Post describes

its methodology for collecting these data at https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/how-the-washington-post-isexamining-police-shootings-in-the-united-states/2016/07/07/d9c52238-43ad-11e6-8856-f26de2537a9d_story.html.

55

56

57

BJA, a bureau in the Office of Justice Programs of the U.S. Department of Justice, provides leadership and assistance

to local criminal justice programs that improve and reinforce the nation’s criminal justice system. BJA’s goals are to

reduce and prevent crime, violence, and drug abuse and t o improve the way in which the criminal justice system

functions.

Congressional Research Service

8

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

organizations are working in collaboration with the FBI to develop the National Use-ofForce Data Collection.58

nationwide statistics."19 The FBI reports that it is working with major law enforcement organizations to collect national use of force data. The stated goal of the program is "“is not to offer insight into single [use of force]use-of-force incidents but to

provide an aggregate view of the incidents reported and the circumstances, subjects, and officers

involved."20”59 Also, the data will not assess whether the officers involved in use of force incidents

acted lawfully or within the bounds of department policy.

The FBI plans to collect

The program collects data on use of force incidents that resultsresult in the death or serious bodily injury21

injury60 of a person or whenand incidents where a law enforcement officer discharges a firearm at or in

the direction of a person. For each incident, the FBI plans to collectcollects data on the circumstances

surrounding the incident (e.g., date and time, the number of officers who applied force, the reason for the initial contact between the officer and the subject), subject information, and officer information.22 Local law enforcement agencies would be responsible for submitting use of force data to the FBI and participation will be voluntary. The FBI reports that it plans to periodically release use of force statistics to the public and it will publish descriptive information on trends and characteristics of the data.

The FBI reported that it launched a six-month pilot study of its national use of force data collection program on July 1, 2017, which concluded at the end of the year. It provided a report on its findings from the pilot study to the Office of Management and Budget for review and approval. The FBI reported that upon approval it anticipates starting a nationwide data collection effort; however, the results of the pilot study have not been released and there have been no reports as to whether it has started collecting these data.

it (e.g., date and time, the reason for the initial contact between the officer and the

subject, the number of officers who applied force, type of force used), subject information (e.g.,

demographic information, injuries sustained, whether the subject was armed), and officer

information (e.g., demographic information, whether the officer discharged a firearm, whether the

officer was injured). 61 Local law enforcement agencies are responsible for submitting use of force

data to the FBI, though participation is voluntary. The FBI is working with major law

enforcement organizations and the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services’ Advisory Policy

Board to increase participation. 62

Some law enforcement agencies started submitting use-of-force data to the FBI at the beginning

of 2019 and the FBI indicated that data would be released “on a regular basis of no less than two

times a year.”63 The FBI has yet to release any use-of-force data. It has been reported that more

than 6,700 law enforcement agencies are participating in the program; these agencies account for

approximately 40% of all state and local law enforcement officers in the United States. 64 The FBI

is planning to release its first round of use-of-force data in the summer of 2020 through its online

crime data explorer. 65

Death in Custody Reporting Program

DOJ also collected data on arrest-related deaths pursuant to the Death in Custody Reporting Act

of 2000 (DCRA 2000, P.L. 106-297). The act required recipients of Violent Offender

Incarceration/Truth-in-Sentencing Incentive grants 66 to submit data to DOJ on the death of any

58

U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Use-of-Force Data Collection,

https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/use-of-force (hereinafter, “ FBI’s Use of Force Data website”).

59

Ibid.

T he FBI defines serious bodily injury as “bodily injury that involves a substantial risk of death, unconsciousness,

protracted and obvious disfigurement, or protracted loss or impairment of the function of a bodily member, organ, or

mental faculty.” Ibid.

61 More information on the specific data the FBI will collect on each use of force incident can be found on the FBI’s

Use of Force Data website.

60

62

T he Advisory Policy Board is responsible for reviewing policy, technical, and operational issues related to the

Criminal Justice Information Services Division programs. It is comprised of 35 representatives from criminal justice

agencies and national security agencies and organizations throughout the United States.

FBI’s Use of Force Data website.

Kimberly Adams, “FBI Says New Data on Police Use of Force is Coming T his Summer,” Marketplace, June 1,

2020, https://www.marketplace.org/2020/06/01/fbi-police-use-of-force-database/.

63

64

T he FBI’s crime data explorer is available online at https://crime-data-explorer.fr.cloud.gov/.

T he Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 ( P.L. 103-322) authorized funding for grants to states

for building or expanding correctional facilities. T o be eligible for funding under the program , a state had to

demonstrate it had increased the number of violent offenders who were arrested and sentenced to incarceration along

65

66

Congressional Research Service

9

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

person who is in the process of arrest; en route to be incarcerated; or incarcerated at a municipal

or county jail, state prison, or other local or state correctional facility (including juvenile

facilities). The provisions of the act expired in 2006. 67 Congress reauthorized the act by passing

the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013 (DCRA 2013, P.L. 113-242). This act requires states

to submit data to DOJ regarding the death of any person who is detained, under arrest, in the

process of being arrested, en route to be incarcerated, or incarcerated at a municipal or county

jail, a state prison, a state-run boot camp prison, a boot camp prison that is contracted out by the

state, any state or local contract facility, or any other local or state correctional facility (including

juvenile facilities). States face up to a 10% reduction in their funding under the Edward Byrne

Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program if they do not provide the data. 68 The act also

extends the reporting requirement to federal agencies.

BJS, DOJ’s primary statistical agency, established the Death in Custody Reporting Program

(DCRP) as a way to collect the data required by DCRA 2000, and it continued to collect data

even though the initial authorization expired in 2006. DCRP collected data on both deaths that

occurred in correctional institutions and arrest-related deaths, though BJS suspended collection of

arrest-related deaths in 2014. BJS acknowledged problems with arrest-related deaths data before

suspending the data collection effort. In a report on arrest-related deaths for 2003-2009, BJS

noted that “arrest-related deaths are under-reported” and that the data are “more representative of

the nature of arrest-related deaths than the volume at which they occur.”69

BJS has replaced the DCRP with the Mortality in Correctional Institutions (MCI) program, which

collects data on deaths that occur while inmates are in the custody of local jails, state prisons

(including private prisons), or the Bureau of Prisons. BJS notes that MCI collects “many, but not

all, of the elements outlined in the DCRA reauthorization (P.L. 113-242), but because MCI is

collected for statistical purposes only, it cannot be used for DCRA enforcement.”70

A 2018 review conducted by DOJ’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found several issues

with DOJ’s implementation of the requirements of DCRA 2013. 71 According to the OIG:

There were delays in implementing requirements to collect data on arrest-related

deaths as DOJ considered different methodologies to collect these data from

states and debated which agency in DOJ would be responsible for doing so. BJS

was testing a new methodology to collect data on arrest-related deaths (discussed

below) to implement the requirements of DCRA 2013, but DOJ eventually

decided to have BJA administer the program. This was done because determining

whether states are complying with the requirements of the act is a policy

decision, and “it would be inadvisable for BJS to collect state DCRA data on

with increasing the average length of violent offenders’ sentences, or that it had implemented truth-in-sentencing laws

that would require violent offenders to serve at least 85% of their sentences.

67

H.Rept. 113-285.

68

For more information on the JAG program, see CRS In Focus IF10691, The Edward Byrne Memorial Justice

Assistance Grant (JAG) Program .

Andrea M. Burch, Arrest-Related Deaths, 2003-2009―Statistical Tables, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of

Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 235385, Washington, DC, November 2011, p. 1.

70 U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Mortality In Correctional

Institutions (MCI) (Formerly Deaths In Custody Reporting Program (DCRP)) , https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&

tid=19.

69

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of the Inspector General, Review of the Department of Justice’s Implementation of

the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013, December 2018, https://oig.justice.gov/reports/2018/e1901.pdf

(hereinafter, “OIG’s report on DOJ’s implementation of the Death in Custody Reporting Act ”).

71

Congressional Research Service

10

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

behalf of another entity that would perform the compliance assessment because

even such limited involvement could undermine BJS’s position as on objective

statistical collection agency and could cause survey respondents to withhold

future data.”72

Data collected by BJA is duplicative of data collected by BJS through the MCI

program. Both programs collect data on deaths in state and local correctional

institutions. BJS plans to continue to collect data through the MCI program

because the data “compliment BJS’s overall correctional research.”73 Data

collected by BJA are also potentially duplicative of data the FBI collects through

its Use of Force Data Collection program. Both programs collect data on

incidents where the use of force results in death, though the FBI is also collecting

data on other use of force incidents. The OIG notes that duplicative data

collection efforts can “confuse and fatigue data respondents, who in turn may

submit low-quality data.”74

There is concern that the data collection methodology employed by BJA does not

capture all deaths that should be reported pursuant to DCRA 2013. The OIG

noted that BJA’s methodology is similar to that used by BJS in the past to collect

data on arrest-related deaths, which BJS eventually discarded because deaths

were underreported. The OIG raised concerns that DOJ is not using a

methodology pilot tested by BJS where data on arrest-related deaths were

collected through open sources (e.g., media accounts) and served as a potential

universe of arrest-related deaths. BJS contacted law enforcement agencies to

confirm the deaths and collect data on any other arrest-related deaths. BJS also

surveyed a sample of law enforcement agencies where searches of open source

information did not reveal any reports of arrest-related deaths to confirm that

they did not have any reportable deaths. The methodology used by BJA requires

states to establish their own systems for collecting and reporting data required by

DCRA 2013. The OIG noted that these systems might not capture complete data

on arrest-related deaths because (1) state-level agencies are generally less aware

of and less knowledgeable about deaths that occurred in their states than are the

local jurisdictions where the deaths occurred and (2) many state governments

cannot compel subordinate levels of government to report crime data without

state laws that require it.

Starting with FY2019 JAG awards, states have been required to submit DCRA 2013 data to BJA.

States are responsible for establishing their own policies and procedures to ensure that they

collect and submit complete data. 75 DCRA 2013 does not require DOJ to publish data submitted

by states pursuant to the act, and BJA has noted that it will maintain the information internally,

though it may be subject to Freedom of Information Act requests.76

72

Ibid., p. 11.

73

Ibid., p. 14.

Ibid., p. 13.

74

75

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, Death in Custody Reporting

Act, Performance Measurement Tool, Frequently Asked Questions, February 2020, p. 2, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/

xyckuh186/files/media/document/DCRA-FAQ_508.pdf.

76

Ibid., p. 3.

Congressional Research Service

11

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

Contacts between the Police and the Public

Contacts between the Police and the Public

Section 210402 of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322) )

requires the Attorney General to "“acquire data about the use of excessive force by law

enforcement officers"” and to publish an annual summary of the data. DOJ has struggled to fulfill this mandate.23 In April 1996, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and the In April 1996, BJS and the

National Institute of Justice (NIJ) published a status report on their efforts to fulfill the

requirements of the act.24 77 This report summarized the results of studies that examined the issue of police use

of force. The report also highlighted difficulties in collecting use of force data, including defining

terms such as use of force, , use of excessive force, and excessive use of force; reluctance by police

agencies to provide reliable data; concerns about the misapplication of reported data; the lack of

attention to provocation in the incident leading to the use of force; and the degree of detail needed

to adequately describe individual incidents.

In November 1997, BJS released a second report about its efforts: Police Use of Force: Collection of National Data.. 78 This report described a pilot project,

project: a survey of approximately 6,400 people who in the past year had initiated an interaction

with a law enforcement officer. The survey asked respondents about the types of interactions they

had with law enforcement officers, both positive and negative. The pilot project eventually led to BJS'’s Police

Public Contact Survey (PPCS). The report also noted that both BJS and NIJ had funded a

National Police Use-of-Force Database Project. The project was administered by the International

Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), and it was developed as a pilot effort to collect incident-based use-of-incidentbased use of force information from local law enforcement agencies. The IACP published a report

in 2001 using the data it collected through its National Police Use-of-Force Database Project.25the project. 79 Critics of the study argue that because the

data were submitted voluntarily, the results are incomplete and inconclusive.26

80

Even though DOJ does not publish annual data on the use of excessive force by law enforcement

officers, it has attempted to implement the requirements of Section 210402 by collecting data on citizens'

citizens’ interactions with police―including whether the police threatened to use or have useddid use force,

and whether the respondent thought the force was excessive―every three years starting in 1996 through its PPCS.27 One . BJS collected PPCS data every three

years from 1996 to 2011 and then again in 2015, but BJS has not collected these data since. One

limitation of the PPCS is that it is a survey administered to a sample of law enforcement agencies, so while

it might be able to generate a reliable estimate of when citizens report law enforcement officers

using force against them, it is not a census of all such incidents.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDC, in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), compiles mortality data provided

voluntarily by all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories (jurisdictions). These data

are coded to include information about manner of death, including whether the death was caused

by legal intervention. Legal intervention is defined as “injuries inflicted by the police or other

law-enforcing agents, including military on duty [excluding operations of war], in the course of

arresting or attempting to arrest lawbreakers, suppressing disturbances, maintaining order, and

77

T om McEwen, National Data Collection on Police Use of Force, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice

Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 160113, Washington, DC, April 1996.

78 Lawrence A. Greenfield, Patrick A. Langan, and Steven K. Smith, Police Use of Force: Collection of National Data,

U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 156040, Washington, DC,

November 1997.

79

T he International Association of Chiefs of Police, Police Use of Force in America, 2001, https://www.theiacp.org/

sites/default/files/2018-08/2001useofforce.pdf.

Human Rights Watch, “ Shielded From Justice: Police Brutality and Accountability in the United States of America, ”

http://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports98/police/toc.htm.

80

Congressional Research Service

12

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

other legal action.”81 These data are compiled as a part of two different CDC surveillance (i.e.,

data collection) systems: (1) the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) and (2) the National

Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). 82

NVSS mortality data are based solely on de-identified death certificate records submitted to CDC

by the jurisdictions. There are known issues with the completeness and accuracy of data in this

system, which are attributable to many factors, including jurisdictional differences in

requirements for death certification, training of individuals responsible for completing death

certificates, and availability of information at the time of death certification. 83 An analysis

compared vital statistics data and a news media-based dataset, finding that for 2015 the mediabased data reported more than twice as many law enforcement-related deaths as the vital statistics

data. 84

In part because of the aforementioned issues with NVSS violent death data, in 2002 CDC

launched NVDRS, a state-based surveillance system specifically for violent deaths, with six

initial grants to states. 85 As of FY2018, NVDRS is funded to operate in all 50 states, the District

of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. 86 Personnel in these jurisdictions gather and link records from law

enforcement sources, coroners and medical examiners, death records, and crime laboratories to

report violent deaths to NVDRS, providing better quality information about the causes of and

means to prevent violent deaths than is available from death certificates alone. 87 NVDRS data

have been used in research publications on the use of lethal force by law enforcement. 88

Currently, CDC data capture lethal uses of force by law enforcement, but the data do not capture

non-lethal uses of force. Other CDC violence-related data collection efforts focus on issues such

as interpersonal violence (e.g., intimate partner and sexual violence). 89 With new specified CDC

appropriations of $12.5 million for “Firearm Injury and Mortality Prevention Research” in

81

Based on World Health Organization (WHO), International Classification of Diseases, 10 th Revision (ICD-10),

Y35(.0-.4), Y35(.6-.7), and Y89.0, http://www.who.int/classifications/en/. CDC excludes legal executions from the

definition of legal intervention. Also, the term does not denote the lawfulness of the intervention.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “National Vital Statistics System,” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

nvss/index.htm and CDC, “National Violent Death Reporting System,” https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/nvdrs/

index.html.

82

83

National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics, Next Generation Vital Statistics: A Hearing on Current Status,

Issues, and Future Possibilities, May 2018, https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Summary-Report-NextGeneration-Vitals-Sept-2017-Hearing-Final.pdf.

JM Feldman et al., “Quantifying Underreporting of Law-Enforcement-Related Deaths in United States Vital

Statistics and News-Media-Based Data Sources: A Capture-Recapture Analysis, PLoS Med, vol. 14, October 10, 2017,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29016598.

85

Communication to Congressional Research Service from CDC Washington Office, May 9, 2014.

84

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System now includes

all 50 states,” press release, September 5, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0905-national-violentreporting-system.html.

87 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “National Violent Death Reporting System,”

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/nvdrs/index.html.

86

See, for example, Sarah DeGue and Katherine A Fowler, “ Deaths Due to Use of Lethal Force by Law Enforcement:

Findings From the National Violent Death Reporting System, 17 U.S. States, 2009 –2012,” American Journal of

Preventive Medicine, vol. 51, no. 5 (November 1, 2016). Authored by both CDC and non -CDC authors.

88

89

See, for example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), T he National Intimate Partner and Sexual

Violence Survey, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nisvs/materials.html.

Congressional Research Service

13

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

FY2020, 90 CDC issued a grant announcement for a new surveillance system on firearm injuries . 91

It is unclear at this time if this system will collect data on non-lethal firearm injuries attributable

to law enforcement, though the funding announcement specifies that “intent” of the firearm injury

should be captured in the system. 92

Authority for DOJ to Investigate Law Enforcement

Misconduct

The federal government has several legal tools at its disposal to ensure that state and local law

using force against them, it is not a census of all such incidents.

Death in Custody Reporting Program

DOJ also collected data on arrest-related deaths pursuant to the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000 (DCRA, P.L. 106-297). The act required recipients of Violent Offender Incarceration/Truth-in-Sentencing Incentive grants28 to submit data to DOJ on the death of any person who is in the process of arrest, en route to be incarcerated, or incarcerated at a municipal or county jail, state prison, or other local or state correctional facility (including juvenile facilities). The provisions of the act expired in 2006.29 Congress reauthorized the act by passing the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-242). The act requires states to submit data to DOJ regarding the death of any person who is detained, under arrest, in the process of being arrested, en route to be incarcerated, or incarcerated at a municipal or county jail, a state prison, a state-run boot camp prison, a boot camp prison that is contracted out by the state, any state or local contract facility, or any other local or state correctional facility (including juvenile facilities). States face up to a 10% reduction in their funding under the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program if they do not provide the data.30 The act also extends the reporting requirement to federal agencies.

BJS established the Death in Custody Reporting Program (DCRP) as a way to collect the data required by the Death in Custody Reporting Act of 2000, and it continued to collect data even though the initial authorization expired in 2006. DCRP collected data on both deaths that occurred in correctional institutions and arrest-related deaths, though BJS suspended collection of arrest-related deaths in 2014. BJS acknowledged problems with arrest-related deaths data before suspending the data collection effort. In a report on arrest-related deaths for 2003-2009, BJS notes that "arrest-related deaths are under-reported" and that the data are "more representative of the nature of arrest-related deaths than the volume at which they occur."31

BJS has replaced the DCRP with the Mortality in Correctional Institutions (MCI) program, which collects data on deaths that occur while inmates are in the custody of local jails, state prisons (including inmate housed in private prisons), or the Bureau of Prisons. BJS notes that MCI collects "many, but not all, of the elements outlined in the DCRA reauthorization (P.L. 113-242), but because MCI is collected for statistical purposes only, it cannot be used for DCRA enforcement." It is not clear how BJS will operationalize the other requirements of DCRA.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) receives and publishes death certificate data voluntarily provided to it by all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories.32 For publication of national data on violent deaths, CDC codes the intent or manner of death, such as suicide, homicide, legal intervention, or unintentional (among others). Legal intervention is defined as "injuries inflicted by the police or other law-enforcing agents, including military on duty [excluding operations of war], in the course of arresting or attempting to arrest lawbreakers, suppressing disturbances, maintaining order, and other legal action."33

There are few published studies of deaths attributed to legal intervention in the United States. A recent analysis compared vital statistics data (i.e., death certificates) and a news-media-based dataset, finding that, for 2015, the media-based data reported more than twice as many law-enforcement-related deaths as the vital statistics data.34

In 2002, CDC launched the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), a state-based surveillance system for violent deaths. As of FY2018, NVDRS is funded to operate in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.35 Personnel in these jurisdictions gather and link records from law enforcement sources, coroners and medical examiners, vital statistics, and crime laboratories to report violent deaths in NVDRS, providing better quality information about the causes of and means to prevent violent deaths than is available from death certificates alone.36

Authority for DOJ to Investigate Law Enforcement Misconduct

The federal government has several legal tools at its disposal to ensure that state and local law enforcement practices and procedures adhere to constitutional norms.37enforcement practices and procedures adhere to constitutional norms. 93 The first is criminal

The first is criminal enforcement brought directly against an offending officer under several federal civil rights statutes. Section 242 of Title 18 makes it a federal crime to willfully deprive a person of their constitutional rights while acting under color of law.38 Similarly, Section 241 of Title 18 outlaws conspiracies to deprive someone of their constitutional rights.39 These statutes, enacted during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, were primarily intended to safeguard rights newly bestowed on African Americans One

such statute, 18 U.S.C. Section 242, makes it a crime for a person acting “under color of any law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom” to willfully deprive another person of any “rights,

privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United

States[.]”94 Section 242 also prohibits a person acting under color of law from subjecting another

person to “different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or

by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens[.]”95 A related

provision, Section 241 of Title 18, makes it a crime for two or more persons to “conspire to

injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person … in the free exercise or enjoyment of any

right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States[.]”96 The modern

versions of Section 241 and Section 242 originate from the Reconstruction Era following the

Civil War, 97 when Congress sought to safeguard rights newly bestowed on African Americans

under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. 98

DOJ enforces Section 241 and Section 242 by bringing criminal charges against individuals

accused of violating those statutes. 99 A defendant may violate Section 242 either by depriving

90

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on the Departments of Labor, Health and

Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies, Division A-Department of Labor, Health and Human Services, and

Education, and Related Agencies, committee print, 116 th Cong., 2 nd sess., 2020, p. 42.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Firearm Injury Surveillance T hrough Emergency Rooms

(FAST ER), CDC-RFA-CE20-2005,” May 8, 2020, Grants.gov, https://www.grants.gov/web/grants/viewopportunity.html?oppId=325523.

91

92

Ibid.

93

In addition to legal enforcement by government actors, 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 provides a cause of action for private

actors to vindicate violations of constitutional rights such as police use of unreasonable force. See Graham v. Connor,

490 U.S. 386 (1989).

94 18 U.S.C. §242.

95

Ibid.

96

Ibid. §241.

See United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787, 801 (1966).

97

98

See Edward F. Malone, Legacy of Reconstruction: The Vagueness of the Criminal Civil Rights Statutes, 38 UCLA L.

Rev. 163, 164 (1990). Section 242 was first enacted before the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, and originally

protected a narrower class of statutory rights. Congress amended the provision in 1874 using its authority to enforce the

Fourteenth Amendment and expanded the scope of the statute to protect both constitutional and statutory rights. See

Price, 383 U.S. at 802-03.

99

T he statutes provide no private right of enforcement, meaning that victims of official misconduct cannot sue under

Section 241 or Section 242. A victim of conduct that violates Section 242 may be able to bring a separate civil suit

under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 or, for federal officers, under the Bivens doctrine. See Bivens v. Six Unknown Named

Agents, 403 U.S. 388 (1971). However, the doctrine of qualified immunity may limit officials’ liability. See CRS Legal

Congressional Research Service

14

Public Trust and Law Enforcement—A Discussion for Policymakers

another person of rights under federal law or the Constitution or by subjecting a person to

different punishments by reason of the victim’s race or other covered characteristics. In practice,

though, Section 242 charges generally allege constitutional violations. 100 In recent years, Section

241 and Section 242under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.40 In more recent years, these statutes have formed the basis of police excessive force criminal cases,41 and form 101 and

provided the legal justificationbasis for DOJ investigations into several recent police killings across the country.42

Arguably, the most contentious issue surrounding Section 242 has been its mens rea, or mental state, element. In the 1945 case Screws v. United States, the Supreme Court interpreted the predecessor of Section 242 to require that the officer have the specific intent of depriving the person of their civil rights.43 The lower courts have parsed Screws to require varying mens rea thresholds, with some instructing that the officer must act with "a bad purpose or evil motive,"44 while others require a less stringent "reckless disregard" standard.45 Some view the intent threshold as blocking too many meritorious cases and argue that it should be lowered to adequately protect civil rights.46

The second major legal tool is a federal statute that focuses on civil liability of law enforcement agencies as a whole, rather than on the wrongdoing of individual officers. Enacted as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, and codified at 34 U.S.C. Section 12601, this statute prohibits government authorities or agents acting on their behalf from engaging in a "pattern or practice of conduct by law enforcement officers ... that deprives persons of rights ... secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States."47 It authorizes the Attorney General to sue for equitable or declaratory relief when he or she has "reasonable cause to believe" that such a pattern of constitutional violation has occurred.

The scope of investigations under Section 12601, primarily conducted by the Special Litigation Section of DOJ's Civil Rights Division, has ranged from police use of force and unlawful stops and searches to racial and ethnic biases.48 Traditionally, these investigations are resolved by consent decree—a judicially enforceable settlement between DOJ and the local police department that outlines the various measures the local agency must take to remedy its unconstitutional police practices. For instance, after two years of extensive investigation into the New Orleans Police Department's policies and practices in which DOJ found numerous instances of unconstitutional conduct, DOJ entered into a consent decree with the City of New Orleans requiring the city to implement new policies and training to police killings across the country.102

Section 242 applies only to persons acting under color of law, meaning “under ‘pretense’ of

law.”103 Essentially, a person acts under color of law when he or she acts with either actual or

apparent federal, state, or local government authority. 104 Officers and employees of the

government generally fall within this category. 105 Government officials act under color of law if

they derive their perceived authority from state or local law, even if their conduct was not

actually authorized under state or local law—for example, because they abused their official

position. 106 Off-duty law enforcement officers may also be subject to Section 242 if they act or

claim to act in their official capacity. 107 Moreover, a person need not actually be a government

employee or official to act under color of law, as long as he or she participates in activity

“attributable to the State.”108 However, a person acting purely in a private capacity is not subject

to Section 242, even if the person is a government employee. 109

Section 242 applies only to violations that are committed willfully. The Supreme Court stringently

construed the willfulness standard in the 1945 case Screws v. United States. 110 In Screws, a

defendant convicted of violating the statute now codified as Section 242 argued that the law was

void for vagueness—that is, it violated the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause because it did

Sidebar LSB10492, Policing the Police: Qualified Immunity and Considerations for Congress, by Whitney K. Novak.

100

For discussion of the possible constitutional limits on using Section 242 to enforce statutory rights and the practical

hurdles that may impede prosecutions under the “punishments, pains, or penalties” provision of Section 242, see CRS

Legal Sidebar LSB10495, Federal Police Oversight: Criminal Civil Rights Violations Under 18 U.S.C. § 242 .

101

See, for example, United States v. Bradley, 196 F.3d 762, 764 (7 th Cir. 1999); United States v. Reese, 2 F.3d 870,

880 (9 th Cir. 1993).

102

Paul Lewis, Federal Officials May Use Little-Known Civil Rights Statute in Police Shooting Cases, The Guardian,

December 24, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2014/dec/24/federal-review-michael-brown-eric-garnercrawford-hamilton.

103

See Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91, 111 (1945). T he phrase under color of law originates from the

Reconstruction Era, and variations of it appear in multiple federal hate crime and civil rights statutes. See, for example,

18 U.S.C. §§245, 249; 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983.

104

Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Addressing Police Misconduct Laws Enforced by the Department of

Justice, https://www.justice.gov/crt/addressing-police-misconduct-laws-enforced-department-justice.

See Screws, 325 U.S. at 110 (holding that “officers of the State ... performing official duties,” including public

safety officers, act under color of law for purposes of Section 242).

106 For instance, in one leading case, a Georgia sheriff who arrested a black man on suspicion of theft and then beat him

to death argued that he did not act under color of state law because the killing was illegal under Georgia law. T he

Supreme Court rejected that argument, explaining that “[a]cts of officers who undertake to perform their official duties

are included whether they hew to the line of their authority or overstep it.” Screws, 325 U.S. at 111.

105

107