Drought Contingency Plans for the Colorado River Basin

Changes from October 19, 2018 to February 15, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

INSIGHTi

Drought Contingency Plans for the Colorado

River Basin

Updated February 15, 2019

The Colorado River Basin is a critical source of water and power supplies for seven western states and

Mexico. The basin is in the midst of a long-term drought, and water levels at its. Water levels at the basin’s two largest

reservoirs, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, could reach critically low levels. Building on several prior agreements,

the basin states and the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) recently announced Drought Contingency Plansdrought contingency

plans (DCPs) that aim to decrease the likelihood of major water and power supply curtailments for users.

Colorado River Basin in Context

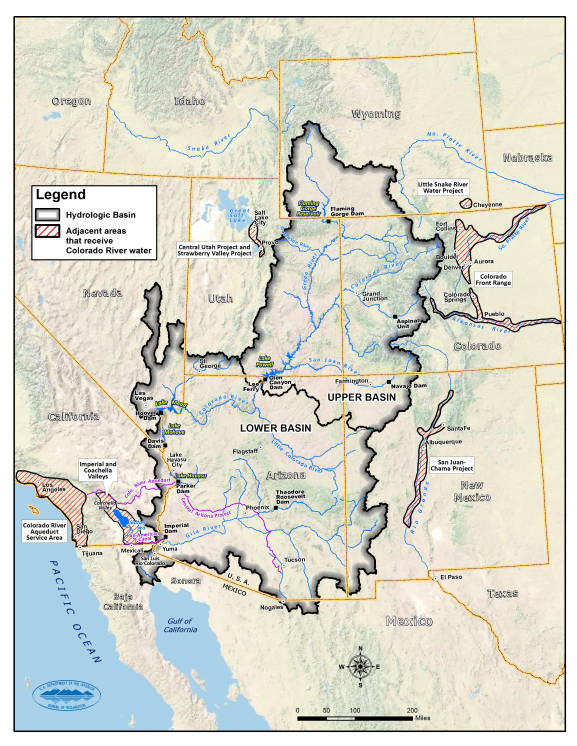

The Colorado River Basin (Figure 1) covers approximately 246,000 square miles, 97% of which are in

the United States. It includes the Colorado River and its tributaries, which cross the U.S. border into

Mexico before discharging into the Gulf of California. Pursuant to federal law, multiple federal facilities

(e.g., Hoover Dam and Glen Canyon Dam) store and convey water from the river and its tributaries and generate hydropower for

the southwestern United States. The primary federal agency with jurisdiction over the river is

Reclamation, an agency within the Department of the Interior (DOI).

|

|

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

IN10984

CRS INSIGHT

Prepared for Members and

Committees of Congress

Congressional Research Service

Figure 1. Colorado River Basin and Major Facilities

Source: Bureau of Reclamation |

.

Based on observed data, average natural Colorado River flows in the 20th centuryflows in the 20th century were about 15 million

acre-feet (maf) annually. Flows have dipped during an ongoing, long-term drought dating from 2000;

Reclamation estimated that from 2008 to 2018, flows averaged 12.9 maf.

2

Congressional Research Service

acre-feet (maf) annually, while paleoclimate reconstructions estimated that mean annual flows were lower (ranging from 13-14.7 maf). Flows have dipped during the ongoing drought; Reclamation estimated that from 2000 to 2016, flows averaged 12.4 maf. These lower flows appear to parallel historic droughts on the river, some of which lasted for decades.

Colorado River Compact

Colorado River Compact

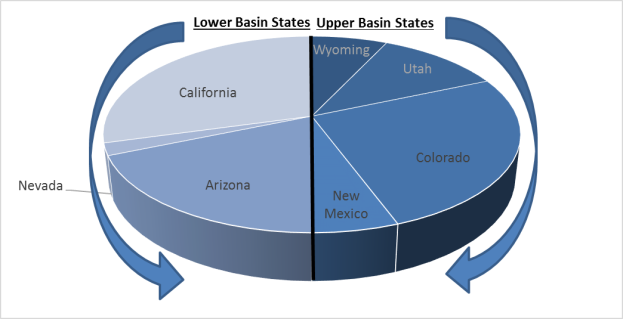

The Colorado River Compact of 1922, negotiated, agreed to by the basin states and the federal government, is the

foundation of the "“Law of the River,"” which governs Colorado River operationswater management. Under the compact, the states established a framework to apportion the water supplieswater

supplies are divided equally between the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin, with the dividing line at Lee'

Lee’s Ferry, AZ (near the Utah Border). Each basin was apportioned 7.5 maf annually. Congress

approved the compact in the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928. Multiple other compacts, federal laws,

court decisions, and regulatory guidelines have since been added to the Law of the River. State-level

apportionments were established by documents approved subsequent to the Colorado River Compact of 1922 (Figure 2). .

Pursuant to a 1944 treaty with Mexico, an additional 1.5 maf per year was reserved for flows south of the border.

When the Colorado River Compact of 1922 was approved, average annual flows on the river were assumed to be 16.4 maf per year. However, actual mean flows are considerably less than this amount and may decrease further. A 2012 Reclamation study projected a long-term imbalance in basin supply and demand. It noted the basin has thus far avoided serious impacts on supplies due to the significant storage within the system (60 maf), coupled with the fact that Upper Basin states have not fully used their entitlement. Additional supply constraints may result from tribal water rights. Tribes have diversion rights to 2.9 maf of Colorado River water, and several other reserved water rights claims for basin tribes have not been settled. These rights have the potential to take away from other apportionments.

Drought Contingency Plans

After several years of negotiations, in October 2018 Reclamation and the basin states announced draft drought contingency plans (DCPs) for the Upper and Lower Basins. The DCPs aim to decrease the likelihood of major supply curtailments and other basin impacts. The plans build on a series of agreements dating to 2003 that have attempted to relieve pressure on basin water supplies and stabilize storage levels. Selected prior agreements most relevant to the DCPs include

2003Quantification Settlement Agreement(QSA).The QSA aimed to have California(QSA). California agreed to reduce water use to adhere to its Colorado River water allocation, while also committing the stateand committed to a path for(a related water bodyin Southern California).- .

2007 Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and

the CoordinatedOperationsCoordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead.. These guidelines included"balancing"“balancing” releases from Lakes Mead and Powelldetermined by "trigger levels" at both reservoirs, a schedule of Lower Basin curtailments, and a mechanism for storing and delivering conserved water in Lake Mead. 2014and a mechanism for storing conserved water in Lake Mead. They also included a schedule of Lower Basin curtailments in Arizona and Nevada if Lake Mead drops to an elevation of 1,075 feet or less (i.e., a “shortage condition”). As of January 2019, there was a 69% chance of a shortage condition beginning in 2020. 2014 Pilot System Conservation Program.Pilot System Conservation Program.This DOI-led effort provided cost-shared-

2017 Minute 323

Agreementagreement with Mexico.. This agreement extended and replaced theand, among other things,with Mexico. It included increased U.S. storageBinational Water Scarcity Planbinational plan that would commit Mexico totiered cutbacksnew delivery curtailments parallel to those in the Lower Basin DCP(see below).

.

The Upper Basin DCP would establish a Demand Management Program for the Upper Basin by

authorizing storage of conserved water in Lake Powell. It also would establish 3,525 feet as the target

operational level for Lake Powell. Together, these efforts would decrease the risk of Lake Powell's ’s

elevation falling below 3,490 feet, at which point reduced hydropower generation and cutbacks to water

users are possible.

The Lower Basin DCP would require that when Lake Mead reaches predetermined elevations, Lower

Basin states would forgo deliveries beyond previously agreed-upon levels. It also wouldwould further incentivize

voluntary conservation of water to be stored in Lake Mead and commit DOI to conserving 100,000 acre-feetacrefeet of water that will be left in the system. The agreement's aim is aims to avoid Lake Mead elevations falling

below 1,020 feet.

DCP implementation requires approval by basin states and stakeholders of the DCPs and a number of

related intrastate agreements. Federal actions in the DCPs also require authorization by Congress. On

February 1, 2019, Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman announced that basin states had not

completed all of the required steps to approve the DCPs by a previously established January 31 deadline.

Thus, the bureau published a Federal Register notice requesting input from basin state governors

regarding how DOI might reduce the risk of drought in the basin. If the DCPs are completed by March

19, the notice would be rescinded and the DCPs could be finalized with congressional authorization. If

they are not completed, DOI may use its authority to make unilateral water delivery cutbacks in the basin.

Congressional Research Service

5

Author Information

Charles V. Stern

Specialist in Natural Resources Policy

Disclaimer

This document was prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). CRS serves as nonpartisan shared staff

to congressional committees and Members of Congress. It operates solely at the behest of and under the direction of

Congress. Information in a CRS Report should not be relied upon for purposes other than public understanding of

information that has been provided by CRS to Members of Congress in connection with CRS’s institutional role.

CRS Reports, as a work of the United States Government, are not subject to copyright protection in the United

States. Any CRS Report may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without permission from CRS. However,

as a CRS Report may include copyrighted images or material from a third party, you may need to obtain the

permission of the copyright holder if you wish to copy or otherwise use copyrighted material.

IN10984 · VERSION 7 · UPDATED

below 1,020 feet.

Implementation of the DCPs would require approval of multiple state agencies and contractors, as well as authorization by Congress. It is unclear what, if any, other federal commitments also might be required to implement the DCPs.