U.S. Farm Income Outlook for 2018

Changes from September 21, 2018 to December 11, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- USDA's 2018 Farm Income Forecast

- Selected Highlights

- U.S. Agriculture Outlook: 2018 Overview

- Large Corn and Soybean Crop Prospects Dominate Markets

EarlyLivestock Outlook for 2018- USDA Trade aid Package

- Gross Cash Income Highlights

- Crop Receipts

- Livestock Receipts

- Government Payments

- Production Expenses

- Cash Rental Rates

- Agricultural Trade Outlook

- Key U.S. Agricultural Trade Highlights

- U.S. Farm and Manufactured Agricultural Product Export Shares

- Farm Asset Values and Debt

- Average Farm Household Income

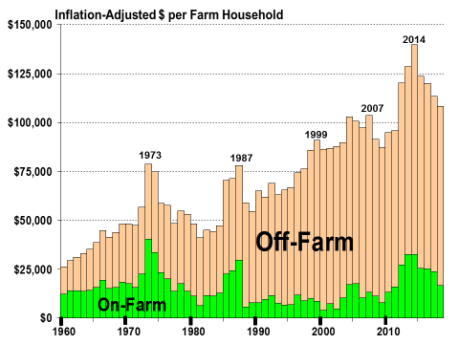

- On-Farm vs. Off-Farm Income Shares

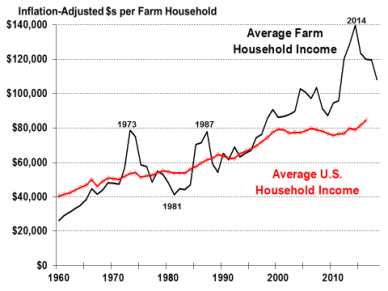

- U.S. Total vs. Farm Household Average Income

Figures

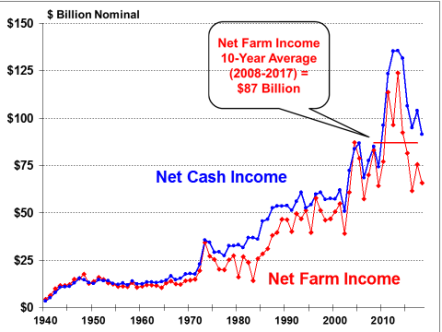

- Figure 1. Annual U.S. Farm Sector Nominal Income, 1940-2018

- Figure 2. Annual U.S. Farm Sector Inflation-Adjusted Income, 1940-2018

- Figure 3. Dry Conditions Across South

,and North-Central Heading into 2018 - Figure 4.

Dry Conditions Across Southern Plains, Parts of Corn BeltUSDA Topsoil Moisture Measurements Affirm Surplus Conditions

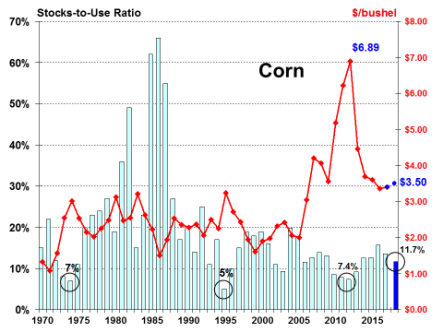

- Figure 5. U.S. Corn Stocks-to-Use Ratio Down, Price Up Slightly in 2018

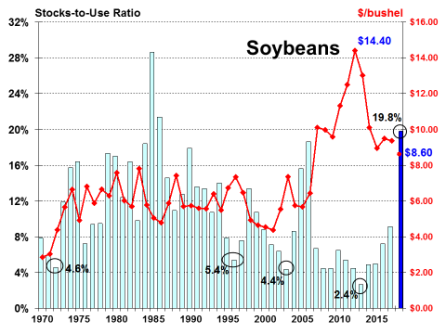

- Figure 6. U.S. Soybean Stocks-to-Use Ratio Up Sharply, Price Down in 2018

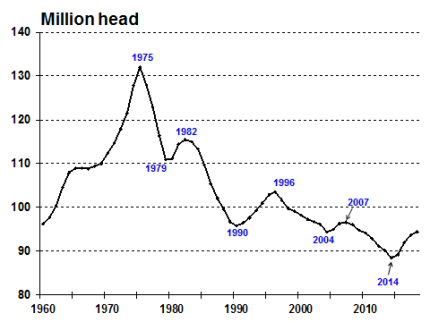

- Figure 7. The U.S. Beef Cattle Inventory (Including Calves) Since 1960

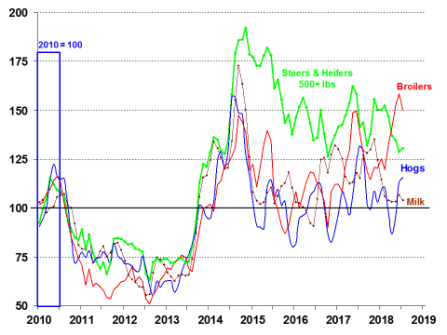

- Figure 8. Indexed Farm-Price-to-Feed Ratios for Cattle, Broilers, Milk, and Hogs

- Figure 9. The MPP Margin Has Fallen Below $8/cwt. in Early 2018

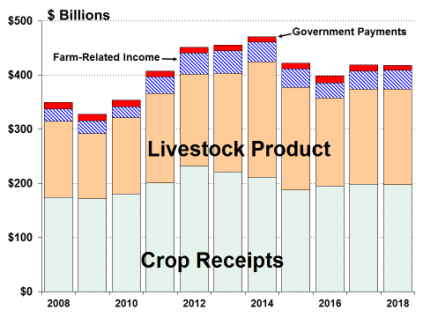

- Figure 10. Farm Cash Receipts by Source, 2008-2018

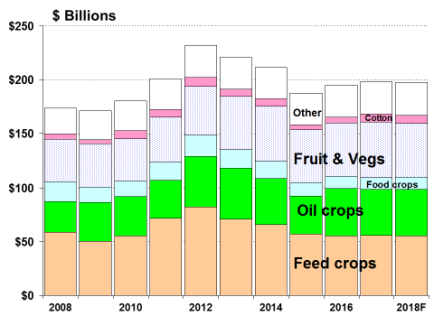

- Figure 11. Crop Cash Receipts by Source, 2008-2018

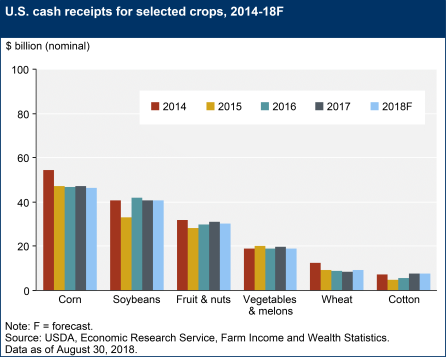

- Figure 12. Cash Receipts for Selected Crops, 2014-2018

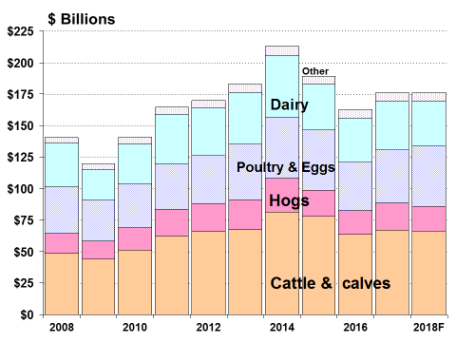

- Figure 13. U.S. Livestock Product Cash Receipts by Source, 2008-2018

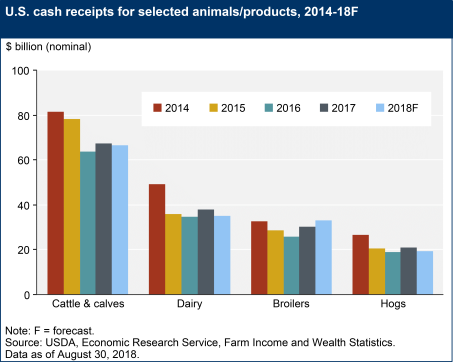

- Figure 14. Cash Receipts for Selected Animal Products, 2014-2018

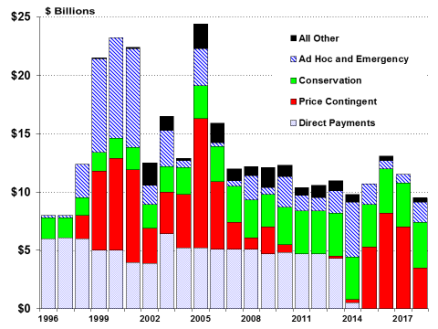

- Figure 15. U.S. Government Farm Support, Direct Outlays, 1996-

20182018F

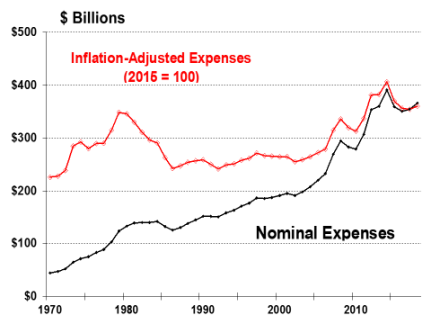

- Figure 16. Total Annual Farm Production Expenses, 1970-2018

- Figure 17. Index of Monthly Prices Received versus Prices Paid, 2006-2018

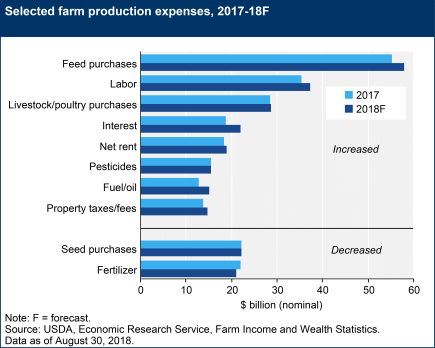

- Figure 18. Farm Production Expenses for Selected Items, 2017 and 2018

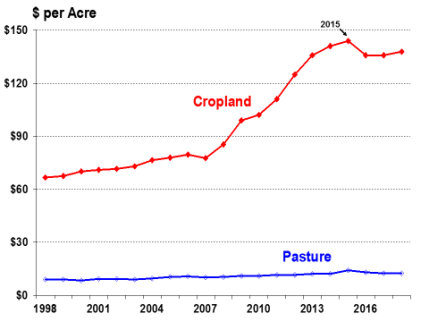

- Figure 19. U.S. Average Farm Land Cash Rental Rates Since 1998

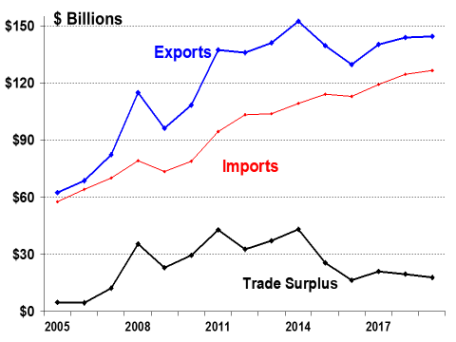

- Figure 20. U.S. Agricultural Trade Since 2005, Nominal Values

- Figure 21. U.S. Agricultural Exports Have Leveled Off Since FY2011

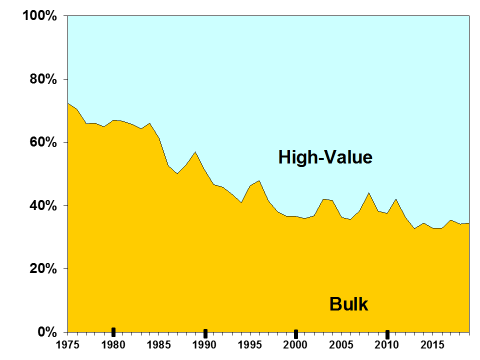

- Figure 22. U.S. Agricultural Trade: Bulk vs. High-Value Shares

- Figure 23. U.S. Export Share of Farm and Manufactured Agricultural Production

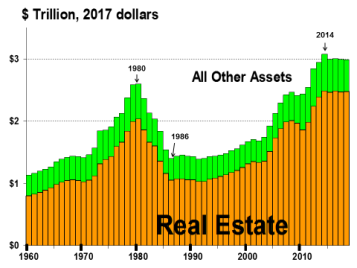

- Figure 24. Real Estate Assets Comprise 81% of Total Farm Sector Assets in 2018

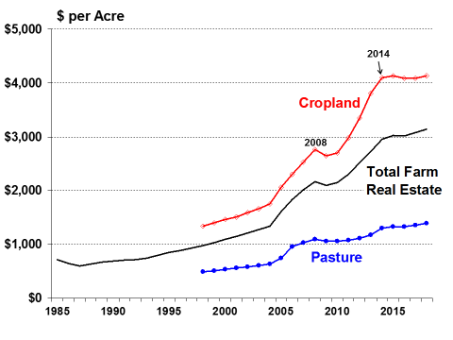

- Figure 25. U.S. Average Farm Land Values, 1985-2018

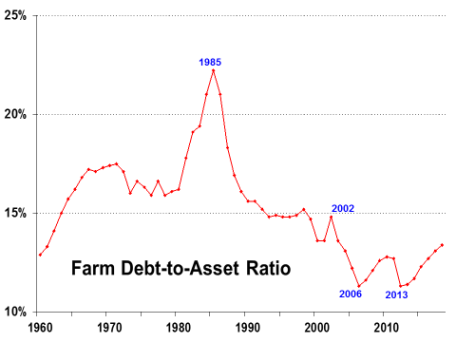

- Figure 26. U.S. Farm Debt-to-Asset Ratio, 1960-2018

- Figure 27. U.S. Average Farm Household Income, by Source, 1960-2018

- Figure 28. Farm Household Income Has Been Above U.S. Average, 1960-2018

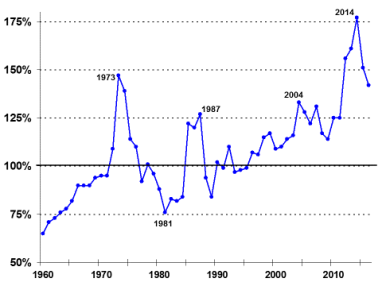

- Figure 29. Ratio of Average U.S. Farm to National Household Income

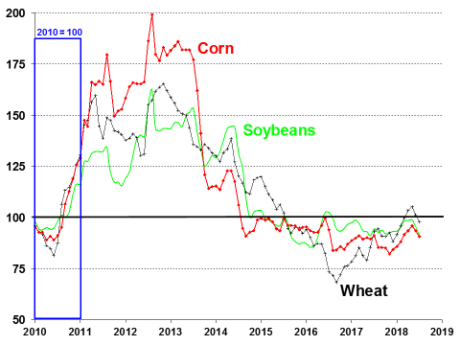

- Figure A-1. Monthly Farm Prices for Corn, Soybeans, and Wheat, Indexed Dollars

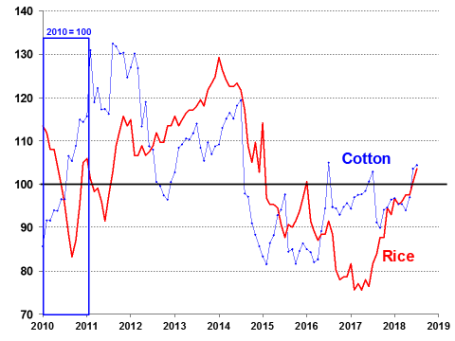

- Figure A-2. Monthly Farm Prices for Cotton and Rice, Indexed Dollars

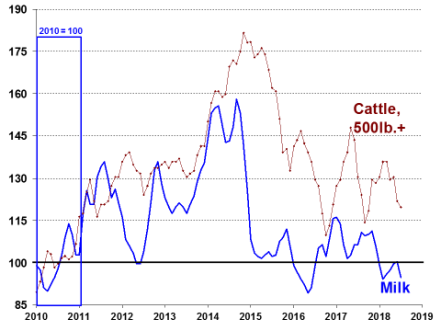

- Figure A-3. Monthly Farm Prices for All-Milk and Cattle (500+ lbs.), Indexed Dollars

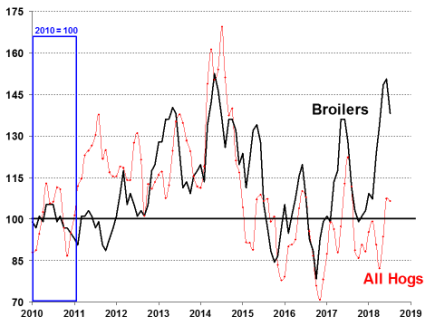

- Figure A-4. Monthly Farm Prices for All Hogs and Broilers, Indexed Dollars

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

According to USDA's Economic Research Service (ERS), national net farm income—a key indicator of U.S. farm well-being—is forecast at $65.7 billion in 2018, down 13% from last year. This forecast does not include any payments under the trade aid package announced by USDA in July 2018. The forecast decline in 2018 net farm income is the result of lower cash returns—from both production activities (-0.1%) and government program payments (-17.4%)—and higher production expenses (up 3.366.3 billion in 2018, down over $9 billion (-12%) from last year. The forecast decline in 2018 net farm income is the result of a small increase in gross returns (up $5.8 billion or +1.3%)—including the initial tranche of payments under the trade aid package announced by USDA in July 2018—offset by higher production expenses (up $14.9 billion or +4.2%). Net farm income is calculated on an accrual basis. Net cash income (calculated on a cash-flow basis) is also projected lower in 2018 (-128%) to $91.593.4 billion.

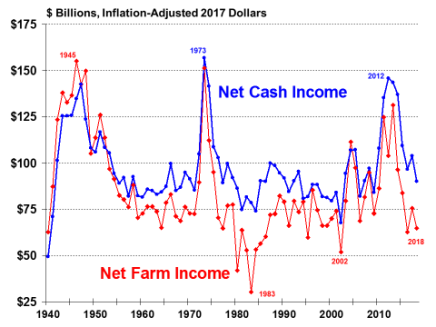

The 2018 net farm income forecast is substantially below the 10-year average of $87 billion (in nominal dollars). It would be the lowest since 2016 in nominal and inflation-adjusted 2017 dollars. This is primarily the result of the outlook for continued weak prices for most major crops. U.S. farm income experienced a golden period during 2011 through 2014 due to strong commodity prices and robust agricultural exports. Most crops and livestock product prices remain significantly below the average for 2011-2014, when prices for many major commodities attained record or near-record highs. Net farm income is projected down 47% since its record high of $123.7 billion in 2013. Net cash income is projected down 32% from its 2013 high of $135.6 billion. Farm-sector production expenses have risen 1.6% over that same period, thus contributing to lower aggregate income totals.

Government payments are projected down 17% from 2017 at $9.3 billion—due largely to projected lower payments in 2018 under the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) revenue support programs for major field crops (projected at $3.5 billion, down 50% from $7.0 billion in 2017).

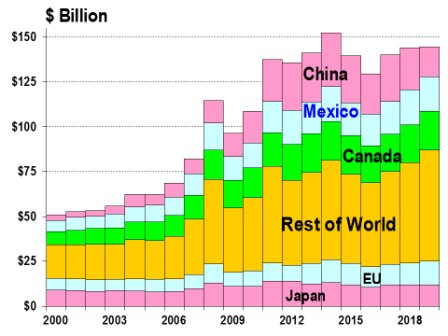

Since 2008, U.S. agricultural exports have accounted for a 20% share of U.S. farm and manufactured or processed agricultural sales. In 2018 agricultural exports are forecast to be flat, at $144.5 billion, due largely to abundant supplies in international markets and strong competition from major foreign competitors. The ongoing U.S.-China trade dispute is expected to shift trade patterns, but the aggregate value of U.S. exports is expected to hold steady.

In spite of the lower farm income outlook, farm wealth is projected up 1.2% from 2017 to $3.0 trillion. Farm asset values reflect farm investors' and lenders' expectations about long-term profitability of farm sector investments. Farmland values are projected up 1.9% in 2018 following a 2.3% rise in 2017. Because they comprise such a significant portion of the U.S. farm sector's asset base (81%), change in farmland values is a critical barometer of the farm sector's financial performance. At the farm household level, average farm household incomes have been well above average U.S. household incomes since the late 1990s. In 2016 (the last year with comparable data), the average farm household income (including off-farm income sources) of $117,918 was about 42% higher than the average U.S. household income of $83,143.

The outlook for lower net farm income and relatively weak prices for most major program crops signals the likelihood of continued relatively lean times ahead. With record soybean and near-record corn crops predicted by USDA, the U.S. agricultural sector's well-being remains dependent on continued growth in domestic and foreign demand to sustain prices at current modest levels. In addition to commodity prices, the financial picture for the agricultural sector as a whole heading into 2019 will hinge on both domestic and international macroeconomic factors, including interest rates, economic growth, and consumer demand. This report incorporates USDA's August 30, 2018, farm income projections and its August 29, 2017, U.S. agricultural trade outlook update.

According to USDA's Economic Research Service (ERS), national net farm income—a key indicator of U.S. farm well-being—is forecast at $65.7 billion in 2018, down 13% from last year. This forecast does not include any payments under the trade aid package announced by USDA in July 2018. The forecast decline in 2018 net farm income is the result of lower cash returns—from both production activities (-0.1%) and government program payments (-17.4%)—and higher production expenses (up 3.3%). Net farm income is calculated on an accrual basis. Net cash income (calculated on a cash-flow basis) is also projected lower in 2018 (-12%) to $91.5 billion.

The 2018 net farm income forecast is substantially below the 10-year average of $87 billion (in nominal dollars). It would be the lowest since 2016 in nominal and inflation-adjusted 2017 dollars. This is primarily the result of the outlook for continued weak prices for most major crops86.9 billion (in nominal dollars)—primarily the result of the outlook for continued weak prices for most major crops. Commodity prices are under pressure from a record soybean and near-record corn harvest and from diminished export prospects due to an ongoing trade dispute with China. U.S. farm income experienced a golden period during 2011 through 2014 due to strong commodity prices and robust agricultural exports. Most crops and livestock product prices remain significantly below the average for 2011-2014, when prices for many major commodities attained record or near-record highs. Net farm income is projected down 4746% since its record high of $123.7 billion in 2013. Net cash income is projected down 3231% from its 2013 high of $135.6 billion. Farm-sector production expenses have risen 1.62.5% over that same period, thus contributing to lower aggregate income totals.

Government payments are projected down 17% from 2017 at $9.3 billion—due largely to projected lower payments in 2018 under the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) revenue support programs for major field crops (projected at $3.5 billion, down 50% from $7.0 billion in 2017).

Since 2008, U.S. agricultural exports have accounted for a 20% share of U.S. farm and manufactured or processed agricultural sales. In 2018 total agricultural exports are forecast to be flat, at $144.5 billion, due largely toup 2% at $143.4 billion. However, abundant supplies in international markets and, strong competition from major foreign competitors. The, and the ongoing U.S.-China trade dispute isare expected to shift trade patterns, but the aggregate value of U.S. exports is expected to hold steady and diminish U.S. export prospects in 2019.

In spite of the lower farm income outlook, farm wealth is projected up 1.24% from 2017 to $3.0 trillion. Farm asset values reflect farm investors' and lenders' expectations about long-term profitability of farm sector investments. Farmland values are projected up 1.9% in 2018 following a 2.3% rise in 2017. Because they comprise such a significant portion of the U.S. farm sector's asset base (81%), change in farmland values is a critical barometer of the farm sector's financial performance. At the farm household level, average farm household incomes have been well above average U.S. household incomes since the late 1990s. In 2016 (the last year with comparable data)However, that advantage has narrowed in recent years. In 2014, the average farm household income (including off-farm income sources) of $117,918 was about 4277% higher than the average U.S. household income of $83,143. In 2017 (the last year with comparable data), that advantage is expected to decline to 27%.

The outlook for lower net farm income and relatively weak prices for most major program crops signals the likelihood of continued relatively lean times ahead. With record soybean and near-record corn crops predicted by USDA, theThe U.S. agricultural sector's well-being remains dependent on continued growth in domestic and foreign demand to sustain prices at current modest levels. In addition to commodity prices, the financial picture for the agricultural sector as a whole heading into 2019 will hinge on both domestic and international macroeconomic factors, including interest rates, economic growth, and consumer demand. This report incorporates USDA's AugustNovember 30, 2018, farm income projections and its August 29, 2017November 29, 2018, U.S. agricultural trade outlook update.

Introduction

The U.S. farm sector is vast and varied. It encompasses production activities related to traditional field crops (such as corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton) and livestock and poultry products (including meat, dairy, and eggs), as well as fruits, tree nuts, and vegetables. In addition, U.S. agricultural output includes greenhouse and nursery products, forest products, custom work, machine hire, and other farm-related activities. The intensity and economic importance of each of these activities, as well as their underlying market structure and production processes, vary regionally based on the agro-climatic setting, market conditions, and other factors. As a result, farm income and rural economic conditions may vary substantially across the United States.

Annual U.S. net farm income is the single most watched indicator of farm sector well-being, as it captures and reflects the entirety of economic activity across the range of production processes, input expenses, and marketing conditions that have prevailed during a specific time period. When national net farm income is reported together with a measure of the national farm debt-to-asset ratio, the two summary statistics provide a quick and widely referenced indicator of the economic well-being of the national farm economy.

|

Measuring Farm Profitability Two different indicators measure farm profitability: net cash income and net farm income. Net cash income compares cash receipts to cash expenses. As such, it is a cash flow measure representing the funds that are available to farm operators to meet family living expenses and make debt payments. For example, crops that are produced and harvested but kept in on-farm storage are not counted in net cash income. Farm output must be sold before it is counted as part of the household's cash flow. Net farm income is a more comprehensive measure of farm profitability. It measures value of production, indicating the farm operator's share of the net value added to the national economy within a calendar year independent of whether it is received in cash or noncash form. As a result, net farm income includes the value of home consumption, changes in inventories, capital replacement, and implicit rent and expenses related to the farm operator's dwelling that are not reflected in cash transactions. Thus, once a crop is grown and harvested, it is included in the farm's net income calculation, even if it remains in on-farm storage. Key Concepts

National versus State-Level Farm Household Data This report focuses singularly on aggregate national net farm income projections for 2018 as reported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) Economic Research Service (ERS).1 Aggregate data often hide or understate the tremendous diversity and regional variation that occurs across America's agricultural landscape. For insights into the differences in American agriculture, visit the ERS websites on "Farm Structure and Organization" and "Farm Household Well-being."2 |

USDA's 2018 Farm Income Forecast

According to ERS, U.S. net farm income is forecast at $65.766.3 billion in 2018, down 1312% from last year (Table A-1).3 This forecast does not include anyincludes the first round of payments under the trade aid package announced by USDA in July 2018.4 Under the initial phase of the trade aid package, USDA expects to provide about $4.7 billion in direct payments to qualifying agricultural producers.

The forecast decline in 2018 net farm income represents continued agriculture-sector economic weakness since 2013's record high of $123.8 billion. Abundant domestic and international supplies of grains and oilseeds suggest a fourth straight year of relatively weak commodity prices in 2018 (Figure A-1 through Figure A-4, and Table A-4).

Selected Highlights

- The net farm income forecast for 2018 is substantially below the 10-year average of $

8786.9 billion (Figure 1). In both nominal and inflation-adjusted dollars, the 2018 forecast is the lowest since 2016 (Figure 2). - Net cash income is also projected lower in 2018 at $

91.593.4 billion (-128%).%).Since the record highs of 2012 and 2013, net cash income and net farm income have fallen by3231% and4746%, respectively (Figure 1), thus continuing a general downward trend in farm income since 2013—primarily the result of a significant decline in most farm commodity prices since the 2013-2014period (Figure A-1toFigure A-4). - Cash receipts for most major field crops (feed grains, hay, and wheat), oilseeds (Figure

1211), and animal products (beef, pork, broilers, eggs, and milk; Figure1413) have declined since 2013-2014 as U.S. and global grain and oilseed stocks and animal herds have rebuilt(Table A-4). - Government payments in 2018 are projected

down (-17.4up (+18%) from 2017 at $9.513.6 billion (Figure 15). Under the Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) program, several years of low farm prices have reduced the historical revenue guarantee and resulting payments, while Price Loss Coverage (PLC) program payments are projected lower due to slightly stronger farm prices compared with 2017. Total production expenses for 2018 (Figure 16), at $365.9 billion, are projected up from 2017 (+3.3—highest since 2006. Payments under the Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs are projected lower due to record corn and soybean yields and slightly stronger farm prices compared with 2017. However, USDA's trade aid program—market facilitation program—is expected to provide $4.7 billion in direct payments that more than offset declines in other program payments. Ad hoc disaster assistance and crop insurance indemnity payments were also larger in 2018. Total production expenses for 2018 (Figure 16), at $369.1 billion, are projected up from 2017 (+4.2%), driven largely by feed, fuel, labor, and interest costs.- Global demand for U.S. agricultural exports (Figure 20) is

expected to surpass 2017's relatively strong value of $144 billion in 2018 by $0.5 billion—still below the record of $152.3 billion set in 2014projected at $141.5 billion in 2019, down 1% from 2018, due largely to a decline in sales to China under the U.S.-China trade dispute.5 - Farm asset values and debt levels are projected to

be up slightlyreach record levels in 2018—asset values at $3.0 trillion (+1.24%) and farm debt at $407410 billion (+3.54.2%)—pushing the projected debt-to-asset ratio up to 13.45%, the highest level since 2003 (Figure 26).

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

|

Figure 2. Annual U.S. Farm Sector Inflation-Adjusted Income, 1940-2018 |

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

U.S. Agriculture Outlook: 2018 Overview

In January 2018, USDA reported 2017 fall winter wheat plantings (which would grow outbe harvested as part of the 2018 wheat crop) at 32.7 million acres—the lowest level since 1909.6 The low winter wheat planted acres reflected poor profitability when compared with soybeans. U.S. soybean plantings have been steadily expanding out of the traditional Corn Belt—the fertile agricultural zone stretching from Ohio westward through Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, southern Minnesota, and northern Missouri to the eastern half of Nebraska and Kansas—and into the Central and Northern Plains.

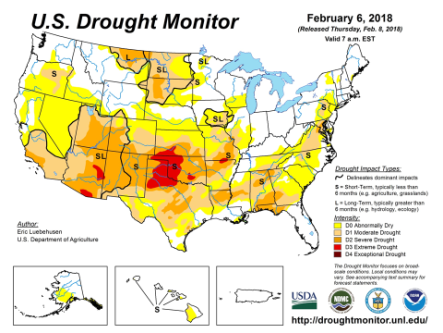

Heading into the 2018 spring planting period, USDA weather reports in early February indicated increasingly dry conditions across the southern tier of the United States and the northern plains (Figure 3). Those dry conditions persisted through much of the early growing season (Figure 4). Such dry conditions generated considerable concerns for producers with no or little access to irrigation. They arewere also of significant concern to the U.S. cattle sector, which depends on spring and early summer grazing across the Northern and Southern Plains and on cheap and abundant feed grains through the remainder of the year. In contrast to the Plains states, the major growing zones of the Corn Belt and Southeast received favorable weather through the growing season, contributing to USDA's forecast for large harvests of corn, soybeans, rice, and cotton in 2018.

Figure 3. Dry Conditions Across South and North-Central Heading into 2018

Source: USDA, Office of the Chief Economist, Current U.S. Drought Monitor, February 6, 2018, http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/data/jpg/current/current_usdm.jpg.

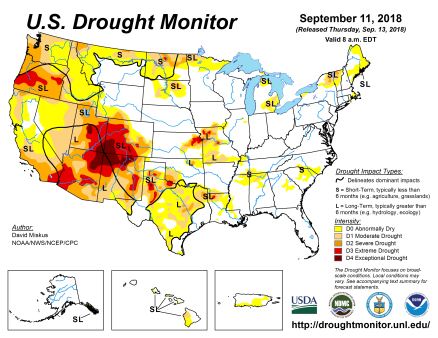

Through the summer months, abundant rainfall occurred throughout the primary temperate crop growing zone stretching from the Dakotas and Kansas eastward to Ohio. By harvest time in September and October, many major crop-producing states found themselves with surplus moisture and wet conditions that delayed harvest (Figure 4).

Figure 4. USDA Topsoil Moisture Measurements Affirm Surplus Conditions

Source: NASS and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin, vol. 105, no. 45 (November 6, 2018).

Large Corn and Soybean Crop Prospects Dominate Markets

Source: NASS and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin, vol. 105, no. 45 (November 6, 2018).

Corn and soybeans are the two largest U.S. commercial crops in terms of both value and quantity. For the past several years, U.S. corn and soybean crops have experienced remarkable growth in both productivity and output, thus helping to build stockpiles at the end of the marketing year. This has been particularly true for soybeans, which hashave seen rapid growth in yield, acres planted, and stocks (Figure 6). This pattern continued into 2018 when, for the first time in history, U.S. soybean plantings (at 89.6145 million acres) narrowly exceeded corn plantings (89.1140 million acres). The record soybean plantings, coupled with record yield (52.81 bushels/acres) is, are expected to produce a record U.S. soybean harvest of 4.76 billion bushels and record ending stocks in 2018.7 The record harvest isand abundant supply are expected to pressure soybean farm prices lower (-8%) to a projected $8.60 per bushel for the 2018/192019 marketing year (Figure 5)—the lowest farm price since 2006.8

For corn, USDA forecasts a record national average yield of 181.3178.9 bushels/acre (up 2.71.3% from the previous year's record yield). As a result, the United States sis expected to produce the second -largest corn harvest on record at 14.86 billion bushels. Despite the near-record production, USDA predicts that record large domestic usage (including for livestock feed, ethanol production, other industrial processing, and seed) plus continued strong exports (third-largest on record at 2.4record exports (2.45 billion bushels) will result in a reduction in corn ending stocks, a decline in the ending stocks-to-use ratio to 11.5% (down from 14.5%), and a slightly higher season average farm price of $3.50/bushel (up 2.9% year-over-year).

|

|

|

|

|

|

The corn and soybean crops provide important inputs for the domestic livestock, poultry, and biofuels sectors. In addition, the United States is traditionally one of the world's leading exporters of corn, soybeans, and soybean products—vegetable oil and meal. During the recent five-year period from 2013/2014 to 2017/2018, the United States exported 49% of its soybean production and 15% of its corn crop. As a result, the outlook for these two crops is critical to both farm sector profitability and regional economic activity across large swaths of the United States as well as in international markets. However, a tariff-related trade dispute between the United States and several major trading partners (in particular, China) has cast considerable uncertainty over the corn and soybean markets.9

The trade dispute has resulted in sharply lower purchases of U.S. agricultural products by China in 2018,10 with continued diminished prospects for 2019. China was the top export market for U.S. agricultural products in 2017 with $25.9 billion in purchases. With the realization of diminished Chinese purchases, USDA has revised downward its expected export value to China for 2018 to $20.5 billion and for 2019 to $13.6 billion.11 Similarly, USDA has lowered its U.S. soybean export forecast from its initial estimate of 2.3 billion bushels in May 2018 to 1.9 billion bushels in its December 2018 WASDE report. The marketing year extends through August 2019. Thus, these forecasts depend on whether the trade dispute continues unabated or how the terms of any resolution (if one were to occur) would impact trade in the first eight months of 2019.

Early Livestock Outlook for 2018

USDA's January 2018 Cattle report reported that U.S. cattle herd expansion, which has been growing since 2015, has slowed markedly but is still projected to grow through 2018.912 Similarly, U.S. hog and poultry flocks have been growing and are expected to continue to expand in 2018.1013

Record profitability among cow-calf producers in 2014 coupled with then-improved forage conditions helped to set off the beef cow herd expansion (Figure 7).1114 The continued cattle expansion through 2018—despite weakening profitability—is primarily the result of a substantial lag in the biological response to the strong market price signals of late 2014. Unfortunately, drought-like conditions have persisted throughout the spring and summer months in the Southern Plains where much of U.S. cattle production occurs (Figure 4). Dry pasture and range conditions tend to limit feeding choices and raise costs for ranchers in affected areas.

During the 2007-2014 period, high feed and forage prices plus widespread drought in the Southern Plains—the largest U.S. cattle production region—had resulted in an 8% contraction of the U.S. cattle inventory (Figure 7). Reduced beef supplies led to higher producer and consumer prices, which in turn triggered the slow rebuilding phase in the cattle cycle that started in 2014 (see the price-to-feed ratio for steers and heifers, Figure 8). The resulting continued expansion of beef supplies pressured market prices lower in 2016. The lower price outlook is expected to persist through 2019, despite strong domestic and international demand across all meat categories—beef, pork, and poultry (Table A-4).

For 2018, increases in production of beef (+3.52.8%), pork (+4.3%),122.9%), broilers (+2.34%), and eggs (+1.72.2%) are projected to expand relatively robustly. Production is projected to continue to grow at strong rates in 2019: beef (+3.3%), pork (+5.3%), broilers (+1.7%), and eggs (+1.5%). Fortunately for producers, USDA projects that combined domestic and export demand will continue to grow for red meat (+4.42%) and poultry (+2.21.8%), thus helping to support prices and profit margins in 2018. Production is projected to grow in 2019 but at slightly lower rates: beef (+2.3%), pork (+4.5%), broilers (+1.9%), and eggs (+1.9%)into 2019.

The changing conditions for the U.S. livestock sector may be tracked by the evolution of the ratios of livestock output prices to feed costs (Figure 8). A higher ratio suggests greater profitability for producers.1315 The cattle-, hog-, and broiler-to-feed margins all moved upwardsupward in during 2014 but have exhibited substantial volatility during the 2015-2018 period.1416 The hog, cattle, and broiler sectors remain profitable. However, continued production growth of between 2% and 3% for red meat and poultry suggests that prices are vulnerable to weakness in demand. Milk prices and the milk-to-feed ratio fell sharply during 2018, suggesting eroding profitability. While this result varies widely across the United States, many small or marginally profitable producers face continued financial difficulties. In addition, both U.S. and global milk production are projected to continue growing in 2018. As a result, milk prices could come under further pressure in 2019;, although USDA is currently projecting milk prices up slightly in 2019.15

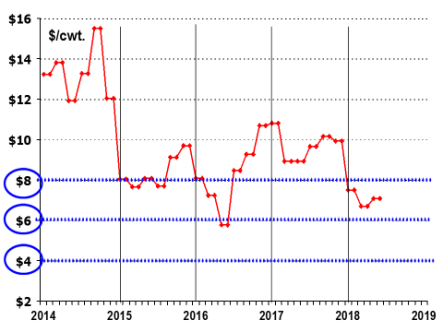

With respect to the federal milk margin protection program (MPP) instituted by the 2014 farm bill (Agricultural Act of 2014, P.L. 113-79), the formula-based milk-to-feed margin used to determine government payments has fallenfell below the $8.00 per hundredweight (cwt.) threshold needed to trigger payments in early 2018. However, in September the margin moved back above $8.00 (Figure 9).18 (Figure 9).16 The MPP margin differs from the USDA-reported milk-to-feed ratio shown in Figure 8 but reflects the same market forces.

|

Figure 9. The MPP Margin Has Fallen Below $8/cwt. in Early 2018 (National average farm price of milk less average feed costs per 100 lbs.) |

|

|

Source: NASS, Agricultural Prices, Note: The margin equals the All Milk price minus a composite feed price based on the formula used by the MPP of the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79). See CRS Report R43465, Dairy Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). |

USDA Trade aid Package

The corn and soybean crops provide important inputs for the domestic livestock, poultry, and biofuels sectors. In addition, the United States is traditionally one of the world's leading exporters of corn, soybeans, and soybean products—vegetable oil and meal. During the recent five-year period from 2013/2014 to 2017/2018, the United States exported 49% of its soybean production and 15% of its corn crop. As a result, the outlook for these two crops is critical to both farm sector profitability and regional economic activity across large swaths of the United States as well as in international markets. However, a tariff-related trade dispute between the United States and several major trading partners has cast considerable uncertainty over the corn and soybean markets.17

As a result of the trade dispute, in July 2018, USDA announced a trade aid package including up to $12 billion in financial support designed to partially offset the negative price and income effects of lost commodity sales to major markets.18 In August 2018, Secretary Perdue announced details of the trade aid package that included initial direct payments of $4.7 billion to qualifying producers of seven agricultural commodities: soybeans, corn, cotton, sorghum, wheat, hogs, and dairy. The August trade aid package also included $1.2 billion in government purchases of excess food supplies and $200 million in trade promotion. The USDA trade aid announcement came too late to be included in USDA's August 30 farm income forecast shown in this report. However, their effect would be to increase net farm income for 2018 by an equivalent amount to $70.4 billion assuming that the entire $4.7 billion is distributed in 2018.

Gross Cash Income Highlights

Total farm sector gross cash income for 2018 is projected to be down (-0.1%) to $418.2 billion, driven by a decline (-0.1%) in the value of agricultural sector production (Figure 10), including a small decline in the value of crop output (-0.3%) partially offset by a slight rise in livestock output (0.1%). An increase in projected farm-related income (+5.6%) is offset by sharply lower government payments (-17.4%)Gross Cash Income Highlights

Total farm sector gross cash income for 2018 is projected to be up (+1.5%) to $423.0 billion, driven by increases in government payments (+17.9%) and farm-related income (+5.2) (Figure 10). Cash receipts from crop and livestock production are up slightly (+0.7%) at $374.9 billion (Table A-1).

Projected farm-sector revenue sources and revenue shares include crop revenues (47% of sector revenues), livestock receipts (42%), government payments (23%), and other farm-related income, including crop insurance indemnities, machine hire, and custom work (8%).

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," August 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts. Notes: Receipts from crop and livestock product sales, and government payments, are described in "Gross Cash Income Highlights |

Crop Receipts

Total crop sales peaked in 2012 at $231.6 billion when a nationwide drought pushed commodity prices to record or near-record levels. In 2018, crop sales are projected at $197.8199.2 billion, down slightly from 2017 (Figure 11). The crop sector includes 2018 projections (and percentage changes from 2017) for the following commodity groups:

- Feed crops—corn, barley, oats, sorghum, and hay: $

55.257.82 billion (-0.6+4.8%); - Oil crops—soybeans, peanuts, and other oilseeds: $

43.242.8 billion (+0.43.8%); - Food grains—wheat and rice: $11.

56 billion (+4.43.5%); - Fruits and nuts: $30.

46 billion (-2.21.7%); - Vegetables and melons: $

19.118.0 billion (-3.88.5%); - Cotton: $7.9 billion (

+-1.0%); and - All other crops—including tobacco, sugar, greenhouse, and nursery crops: $29.

23 billion (+1.8%).

2.7%).

Figure 11. Crop Cash Receipts by Source, 2008-2018

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," August 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts.

Figure 12. Cash Receipts for Selected Crops, 2014-2018

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," November 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts.

Livestock Receipts

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," August 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts.

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," November 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts.

The livestock sector includes cattle, hogs, sheep, poultry and eggs, dairy, and other minor activities. Cash receipts for the livestock sector grew steadily from 2009 to 2014, when it peaked at a record $212.8 billion. However, the sector turned downward in 2015 (-11.0%) and again in 2016 (-14.1%), driven largely by projected year-over-year price declines across major livestock categories (Table A-4 and Figure 13). In 2017, livestock sector cash receipts recovered with year-to-year growth of 8.1% to $176.0 billion. In 2018, strong cash receipts for the poultry and egg sector are projected to partially offset declines in cattle, hog, and dairy sales, keeping overallminimizing the livestock cash receipts flat at $176.2receipt decline to $175.6 billion (+0.1-0.2%). Highlights include 2018 projections (and percentage changes from 2017) for the following livestock groups:

- Cattle and calf sales: $66.

64 billion (-1.14%), - Hog sales: $

19.420.0 billion (-7.75.2%), - Poultry and egg sales: $

47.846.7 billion (+12.19.5%), - Dairy sales, valued at $35.

13 billion (-7.41%), and - Miscellaneous livestock,19 valued at $7.2 billion (+3.

1%).

|

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," August 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts. |

|

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," August 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts. |

4%).

|

Figure 13. U.S. Livestock Product Cash Receipts by Source, 2008-2018 |

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

|

Figure 14. Cash Receipts for Selected Animal Products, 2014-2018 |

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

Government Payments

Government payments in 2018 are projected down 18.6up 17.9% from 2017 at $9.5 billion due largely to projected lower payments under the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) revenue support programs for major field crops—down to $3.5 billion from $7.0 billion in 2017 (See "Price Contingent" in Figure 15).20

Government payments of $9.5 billion would represent a relatively small share (2%) of projected gross cash income of $418.2 billion in 2018. In contrast, government payments are expected to represent 14% of the projected net farm income of $65.7 billion. However, the importance of government payments as a percent of net farm income varies nationally by crop and livestock sector and by region.

13.6 billion—the highest total since 2006 and due largely to payments under the market facilitation program (MFP) by USDA of approximately $4.6 billion in response to the U.S.-China trade dispute.20 In July 2018, USDA announced a trade aid package including up to $12 billion in financial support designed to partially offset the negative price and income effects of lost commodity sales to major markets. In August 2018, Secretary Perdue announced details of the trade aid package that included initial direct payments of $4.7 billion to qualifying producers of seven agricultural commodities: soybeans, corn, cotton, sorghum, wheat, hogs, and dairy. The August trade aid package also included $1.2 billion in government purchases of excess food supplies and $200 million in trade promotion.

USDA ad hoc disaster assistance21 ($1.6 billion, +130%) and crop insurance indemnity payments ($6.0 billion, +15%) are also expected to be larger in 2018 (Table A-4). Without the MFP and ad hoc disaster assistance payments, net farm income would have been reduced by over 20% to about $60 billion in 2018. The MFP and ad hoc disaster assistance payments offset projected lower payments under the PLC and ARC revenue support programs for major field crops—down to $3.0 billion (-57%) from $7.0 billion in 2017 (see "Price Contingent" in Figure 15).22 No payments are forecast under the marketing loan program in 2018, compared with $11.9 million in 2017 and $206 million in 2016, as program crop prices are expected to remain above most program loan rates through 2018 (Table A-4). The MPP for dairy is expected to make $218188 million in MPP payments in 2018.

Conservation programs include all conservation programs operated by USDA's Farm Service Agency and the Natural Resources Conservation Service that provide direct payments to producers. Estimated conservation payments of $3.9 billion are forecast for 2018, up slightly from $3.8 billion in 2017. USDA forecasts supplemental and ad hoc disaster assistance payments at $1.655 billion in 2018, up from $679 million in 2017.21

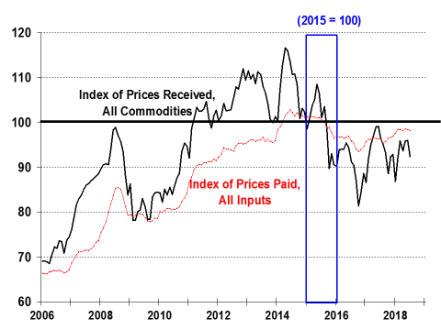

Production Expenses

Total production expenses for 2018 for the U.S. agricultural sector are projected to be up (+3.3%) from 2017 in nominal dollars at $365.9 billion (Figure 16). A comparison of the indexes of prices paid versus prices received reveals that the prices received index generally declined from 2014 through 2016, rebounded in 2017, then declined again in 2018 (Figure 17). Farm input prices (as reflected by the prices paid index) showed a similar pattern but with a much smaller decline from their 2014 peak, thus suggesting that farm sector profit margins have been squeezed since 2014.

Government payments of $13.6 billion still represent a relatively small share (3%) of projected gross cash income of $423.0 billion in 2018. In contrast, government payments are expected to represent 21% of the projected net farm income of $66.3 billion. However, the importance of government payments as a percentage of net farm income varies nationally by crop and livestock sector and by region.

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," November 30, 2018. All values are nominal. Values for 2018 are forecasts. Notes: Data are on a fiscal year basis and may not correspond exactly with the crop or calendar year. "Direct Payments" include production flexibility contract payments enacted under the 1996 farm bill and fixed direct payments of the 2002 and 2008 farm bills. "Price-Contingent" outlays include loan deficiency payments, marketing loan gains, CCP, ACRE, PLC, and ARC payments. "Conservation" outlays include Conservation Reserve Program payments along with other conservation program outlays. "Ad Hoc and Emergency" includes emergency supplemental crop and livestock disaster payments and market loss assistance payments for relief of low commodity prices. "All Other" outlays include market facilitation payments ($4.7 billion in 2018), crop insurance indemnities, cotton ginning cost-share, biomass crop assistance program, peanut quota buyout, milk income loss, tobacco transition, and other miscellaneous payments.

Production Expenses

Total production expenses for 2018 for the U.S. agricultural sector are projected to be up (+4.2%) from 2017 in nominal dollars at $369.1 billion (Figure 16). Production expenses will affect crop and livestock farms differently. The principal expenses for livestock farms are feed costs, purchases of feeder animals and poultry, and hired labor. Feed costs, replacement animal costs, interest costs, and hired labor are projected up in 2018 (Figure 18). Projected changes to the principal crop expenses in 2018 are mixed: fuel and land rent are projected up, while

fertilizersfertilizer costs are projected lower.

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

A comparison of the indexes of prices paid versus prices received reveals that the prices received index generally declined from 2014 through 2016, rebounded in 2017, then declined again in 2018 (Figure 17). Farm input prices (as reflected by the prices paid index) showed a similar pattern but with a much smaller decline from their 2014 peak, thus suggesting that farm sector profit margins have been squeezed since 2014.

|

Figure 18. Farm Production Expenses for Selected Items, 2017 and 2018 |

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

Cash Rental Rates

Renting or leasing land is a way for young or beginning farmers to enter agriculture without incurring debt associated with land purchases. It is also a means for existing farm operations to adjust production more quickly in response to changing market and production conditions while avoiding risks associated with land ownership. The share of rented farmland varies widely by region and production activity. However, for some farms it constitutes an important component of farm operating expenses. Since 2002, about 38% of agricultural land used in U.S. farming operations has been rented.2223

Some farmland is rented from other farm operations—nationally about 8% of all land in farms in 2012 (the most recent year for which data are available)—and thus constitutes a source of income for some operator landlords. However, the majority of rented land in farms is rented from nonoperating landlords. Nationally in 2012, 30% of all land in farms was rented from someone other than a farm operator. Total net rent to nonoperator landlords is projected to be up slightly (+1.3modestly (+2.4%) at $15.78 billion in 2018.

Average cash rental rates for 2018 are up slightly year-over-year ($138 per acre versus $136 in 2017). Although rental rates—which were set the preceding fall of 2017 or in early spring of 2018—dipped in 2016, they still reflect the high crop prices and large net returns of the preceding several years (especially the 2011-2014 period) and have yet to decline to pre-2011 levels (Figure 19). The national rental rate for crop land peaked at $144 per acre in 2015. It is estimated at $138 per acre in 2018.2324

|

Figure 19. U.S. Average Farm Land Cash Rental Rates Since 1998 |

|

|

Source: NASS, Agricultural Land Values, August 2, 2018. All values are nominal. |

Agricultural Trade Outlook

U.S. agricultural exports have been a major contributor to farm income, especially since 2005. As a result, the downturn in those exports that followed 2014's peak of $152.3 billion both coincided with and deepened the downturn in farm income that started in FY2015. In general, since reaching $137.4 billion in FY2011, U.S. agricultural exports have fluctuated between $130 billion and $152 billion (Figure 20).

Key U.S. Agricultural Trade Highlights

- USDA projects U.S. agricultural exports at $

140143.4 billion in FY2018 (unchangedup +2% from 2017's total) but lower in FY2019 at $141.5 billion (-1%). This includes processed and unprocessed agricultural product exports. - USDA also projects that U.S. agricultural imports will be

lower at $117.0up sharply at $127.6 billion (-2%)+7%) in FY2018, with a resulting agricultural trade surplus of $23.015.8 billion (+8%).

-25%). In FY2019, U.S. agricultural imports are projected nearly unchanged at $127.0 billion, but the resultant agricultural trade surplus of $14.5 billion would be the lowest since 2007.

|

Figure 20. U.S. Agricultural Trade Since 2005, Nominal Values |

|

|

Source: ERS, Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade, AES-105, |

- A substantial portion of the increase in U.S. agricultural exports since 2010 has been due to higher-priced grain and feed shipments, record oilseed exports to China, and growing animal product exports to East Asia.

- The top three markets for U.S. agricultural exports in FY2018 are Canada, China

are China, Canada, and Mexico in that order. Together, these three countries have accounted for 46% of total U.S. agricultural exports during the five-year period FY2014-FY2018 (Figure 21). However, their combined share is projected down to44% in FY201942% in FY2019 largely due to sharply lower exports to China. From FY2014 through FY2017, China imported an average of $26.2 billion of U.S. agricultural products. However, USDA forecasts China's imports of U.S. agricultural products to decline to $20.5 billion in FY2018 and to $13.6 billion in FY2019 as a result of the U.S.-China trade dispute. - The fourth- and fifth-largest U.S. export markets are the European Union and Japan, which have accounted for a combined 17% of U.S. agricultural exports during the FY2014-FY2018 period. This same share is projected to continue in FY2019 (Figure 21). Thus, these two markets have shown relatively limited growth in recent years when compared with the rest of the world.

- The "Rest of World" (ROW) component of U.S. agricultural trade—South and Central America, the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia—has shown strong import growth in recent years. ROW is expected to account for

3941% of U.S. agricultural exports in FY2019.

- Over the past four decades, U.S. agricultural exports have experienced fairly steady growth in shipments of high-value products (Figure 22). As grain and oilseed prices decline, so will the bulk value share of U.S. exports.

- Bulk commodity shipments (primarily wheat, rice, feed grains, soybeans, cotton, and unmanufactured tobacco) are forecast at a

34.533.4% share of total U.S. agricultural exports in FY2019 at $49.947.2 billion. This compares with an average share of over 60% during the 1970s and 1980s. - In contrast, high-valued export products—including horticultural products, livestock, poultry, and dairy—are forecast at $94.

63 billion for a65.566.6% share of U.S. agricultural exports in FY2019.

|

Figure 22. U.S. Agricultural Trade: Bulk vs. High-Value Shares |

|

|

Source: ERS, Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade, AES-105, |

U.S. Farm and Manufactured Agricultural Product Export Shares

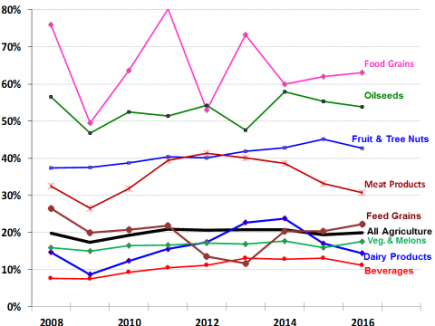

The share of agricultural production (based on value) sold outside the country indicates the level of U.S. agriculture's dependence on foreign markets, as well as the overall market for U.S. agricultural products.

|

The U.S. Export Share Measurement for Agriculture Because agricultural and food exports consist of farm commodities and their manufactured products, a substantial component of export value represents value-added from marketing and processing. This value-added must be accounted for in measuring the U.S. export share. With this in mind, ERS calculates the export value share for agriculture as follows. |

As a share of total farm and manufactured agricultural production, U.S. exports are estimated to account for 19.8% of the overall market for agricultural products from 2008 through 2016—the most recent data year for this calculation (Figure 23). The export share of agricultural production varies significantly by product category.

- At the upper end of the range for export shares, the bulk food grain export share has varied between 50% and 80% since 2008, while the oilseed export share has ranged between 47% and 58%.

MidThe mid-spectrum range of export sharesincludeincludes the export share for fruit and tree nuts, which has ranged from 37% to 45%, while meat products have ranged from 27% to 41%.- At the low end of the spectrum, the export share of vegetable and melon sales has ranged from 15% to 18%, the dairy products export share from 9% to 24%, and the agricultural-based beverage export share between 7% and 13%.

Farm Asset Values and Debt

The U.S. farm income and asset-value situation and outlook suggest a relatively stable financial position heading into 2018 for the agriculture sector as a whole—but with considerable uncertainty regarding the downward outlook for prices and market conditions for the sector and an increasing dependency on international markets to absorb domestic surpluses:

- Farm asset values—which reflect farm investors' and lenders' expectations about long-term profitability of farm sector investments—are projected to be up 1.

64% in 2018 to a nominal $3 trillion (Table A-3). In inflation-adjusted terms (using 2017 dollars), farm asset values peaked in 2014 (Figure 24). - Nominally higher farm asset values are expected in 2018 due to strength in real estate values (+2.1%)

as well as a slight increase, which offset a decrease in non-real estate values (+0.6-4.4%). Real estate traditionally accounts for the bulk of the total value of farm sector assets—nearly an 81% share. - Crop land values are closely linked to commodity prices. The leveling off of crop land values in 2017 reflects mixed forecasts for commodity prices (corn, soybeans, and cotton lower; wheat, rice, and livestock products higher) and the uncertainty associated with international commodity markets (Figure 25).

- Total farm debt is forecast to rise to $

406.9409.5 billion in 2018 (+3.54.8%) (Table A-3). - Farm equity (or net worth, defined as asset value minus debt) is projected to be up slightly (+

0.81.0%) at $2.6 trillion in 2018 (Table A-3). - The farm debt-to-asset ratio is forecast up in 2018 at 13.

45%, the highest level since 2003 but still relatively low by historical standards (Figure 26).

Figure 24. Real Estate Assets Comprise 81% of Total Farm Sector Assets in 2018

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," November 30, 2018. All values are adjusted for inflation using the chain-type GDP deflator, 2017 = 100, OMB, Historical Tables, Table 10.1; 2018 and 2019 are forecasts.

Note: Non-real estate assets include financial assets, inventories of agricultural products, and the value of machinery and motor vehicles.

|

Measuring Farm Wealth: The Debt-to-Asset Ratio A useful measure of the farm sector's financial wherewithal is farm sector net worth as measured by farm assets minus farm debt. A summary statistic that captures this relationship is the debt-to-asset ratio. Farm Farm The debt-to-asset ratio compares the farm sector's outstanding debt related to farm operations relative to the value of the sector's aggregate assets. Change in the debt-to-asset ratio is a critical barometer of the farm sector's financial performance, with lower values indicating greater financial resiliency. A lower debt-to-asset ratio suggests that the sector is better able to withstand short-term increases in debt related to interest rate fluctuations or changes in the revenue stream related to lower output prices, higher input prices, or production shortfalls. The largest single component in a typical farmer's investment portfolio is farmland. As a result, real estate values affect the financial well-being of agricultural producers and serve as the principal source of collateral for farm loans. |

|

|

Source: NASS, Land Values 2018 Summary, August 2018. Notes: Farm real estate value measures the value of all land and buildings on farms. Cropland and pasture values are available only since 1998. All values are nominal. |

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

Average Farm Household Income

Farm household wealth is derived from a variety of sources.2526 A farm can have both an on-farm and an off-farm component to its balance sheet of assets and debt. Thus, the well-being of farm operator households is not equivalent to the financial performance of the farm sector or of farm businesses because of the inclusion of other stakeholders in farming—including landlords and contractors—and because farm operator households often have nonfarm investments, jobs, and other links to the nonfarm economy.

On-Farm vs. Off-Farm Income Shares

Average farm household income (sum of on- and off-farm income) is projected at $109,786111,321 in 2018 (Table A-2), down 8.21.9% from 2017 and well below the record of $134,164 in 2014. About 16% ($17,11917% ($18,637) of total farm household income is from farm production activities, and the remaining 8483% ($92,667684) is earned off the farm (including financial investments). The share of farm income derived from off-farm sources had increased steadily for decades but peaked at about 95% in 2000 (Figure 27).

U.S. Total vs. Farm Household Average Income

- Since the late 1990s, farm household incomes have surged ahead of average U.S. household incomes (Figure 28 and Figure 29).

- In

20162017 (the last year for which comparable data were available), the average farm household income of $117,918113,495 was about4227% higher than the average U.S. household income of $83,14389,632 (Table A-2).

|

Figure 29. Ratio of Average U.S. Farm to National Household Income |

|

|

Source: ERS, "2018 Farm Income Forecast," |

Appendix. Supporting Charts and Tables

USDA Monthly Farm Prices Received Charts

The following set of four charts (Figure A-1 to Figure A-4) presents USDA data on monthly farm prices received for several major farm commodities—corn, soybeans, wheat, upland cotton, rice, milk, cattle, hogs, and chickens. The data isare presented in an indexed format where monthly price data for year 2010 = 100 to facilitate comparisons.

Three tables at the end of this report (Table A-1 to Table A-3) present aggregate farm income variables that summarize the financial situation of U.S. agriculture. In addition, Table A-4 presents the annual average farm price received for several major commodities, including the USDA forecast for the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 marketing yearsyear.

|

Item |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018a |

Change (%)a |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

1. Cash receipts |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Cropsb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Livestock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

2. Government paymentsc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Fixed direct paymentsd |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

CCP-PLC-ARCe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Marketing loan benefitsf |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Conservation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Ad hoc and emergencyg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

All otherh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

3. Farm-related incomei |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

4. Gross cash income (1+2+3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

5. Cash expensesj |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

6. NET CASH INCOME |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

7. Total gross revenuesk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

8. Total production expensesl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

9. NET FARM INCOME |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: ERS, Farm Income and Wealth Statistics; U.S. and State Farm Income and Wealth Statistics, updated as of AugustNovember 30, 2018. NA = not applicable.

a. Data for 2018 are USDA forecasts. Change represents year-to-year projected change between 2017 and 2018.

b. Includes Commodity Credit Corporation loans under the farm commodity support program.

c. Government payments reflect payments made directly to all recipients in the farm sector, including landlords. The nonoperator landlords' share is offset by its inclusion in rental expenses paid to these landlords and thus is not reflected in net farm income or net cash income.

d. Direct payments include production flexibility payments of the 1996 Farm Act through 2001 and fixed direct payments under the 2002 Farm Act since 2002.

e. CCP = counter-cyclical payments. PLC = Price Loss Coverage. ARC = Agricultural Risk Coverage.

f. Includes loan deficiency payments, marketing loan gains, and commodity certificate exchange gains.

g. Includes payments made under the ACRE program, which was eliminated by the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79).

h. CottonMarket facilitation payments, cotton ginning cost-share, biomass crop assistance program, milk income loss, tobacco transition, and other miscellaneous program payments.

i. Income from custom work, machine hire, agri-tourism, forest product sales, and other farm sources.

j. Excludes depreciation and perquisites to hired labor.

k. Gross cash income plus inventory adjustments, the value of home consumption, and the imputed rental value of operator dwellings.

l. Cash expenses plus depreciation and perquisites to hired labor.

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|||||||||

|

Average U.S. farm income by source |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

On-farm income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Off-farm income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Total farm income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Average U.S. household income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NA

|

NA |

||||||||

|

Farm household income as share of U.S. avg. household income (%) |

|

156% |

|

177% |

151% |

142% |

NA |

NA |

Source: ERS, Farm Household Income and Characteristics, principal farm operator household finances, data set updated as of AugustNovember 30, 2018, http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/farm-household-income-and-characteristics.aspx.

Note: NA = not available. Data for 2017 and 2018 are USDA forecasts.

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Farm assets |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Farm debt |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Farm equity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Debt-to-asset ratio (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: ERS, Farm Income and Wealth Statistics; U.S. and State Farm Income and Wealth Statistics, updated as of AugustNovember 30, 2018, http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/farm-income-and-wealth-statistics.aspx.

Note: Data for 2017 and 2018 are USDA forecasts.

Table A-4. U.S. Farm Prices and Support Rates for Selected Commodities Since 2013-2014 Marketing Year

|

Commoditya |

Unit |

Year |

2013-2014 |

2014-2015 |

2015-2016 |

2016-2017 |

2017-2018 |

2018-2019b |

% Chgc 2017 to 2018 |

2019-2020b |

% Chgd 2018 to 2019 |

Loan Ratee |

Refer-ence Price |

||||||||||||

|

Wheat |

$/bu |

Jun-May |

|

|

|

|

|

4. |

8.1% |

— |

— |

2.94 |

5.50 |

||||||||||||

|

Corn |

$/bu |

Sep-Aug |

|

|

|

|

|

3. |

|

— |

— |

1.95 |

3.70 |

||||||||||||

|

Sorghum |

$/bu |

Sep-Aug |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

— |

— |

1.95 |

3.95 |

||||||||||||

|

Barley |

$/bu |

Jun-May |

|

|

|

|

|

4. |

|

— |

— |

1.95 |

4.95 |

||||||||||||

|

Oats |

$/bu |

Jun-May |

|

|

|

|

|

2. |

|

— |

— |

1.39 |

2.40 |

||||||||||||

|

Rice |

$/cwt |

Aug-Jul |

|

|

|

|

|

11. |

- |

— |

— |

6.50 |

14.00 |

||||||||||||

|

Soybeans |

$/bu |

Sep-Aug |

|

|

|

|

|

7. |

- |

— |

— |

5.00 |

8.40 |

||||||||||||

|

Soybean Oil |

¢/lb |

Oct-Sep |

|

|

|

|

|

28.00-32.00 |

-0.1 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Soybean Meal |

$/st |

Oct-Sep |

|

|

|

|

|

290-330 |

-10. |

— |

— |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Cotton, Upland |

¢/lb |

Aug-Jul |

|

|

|

|

|

70-80 |

|

— |

— |

45-52 |

none |

||||||||||||

|

Choice Steers |

$/cwt |

Jan-Dec |

|

|

|

|

|

115-117 |

- |

|

1. |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Barrows/Gilts |

$/cwt |

Jan-Dec |

|

|

|

|

|

43-44 |

- |

39-42 |

- |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Broilers |

¢/lb |

Jan-Dec |

|

|

|

|

|

96-98 |

|

92- |

- |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Eggs |

¢/doz |

Jan-Dec |

|

|

|

|

|

140-142 |

39. |

119- |

-12. |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Milk |

$/cwt |

Jan-Dec |

|

|

|

|

|

16. |

-7. |

16.75-17.75 |

5. |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

Source: Various USDA agency sources as described in the notes below. bu = bushels, cwt = 100 pounds, lb = pound, st = short ton (2,000 pounds), doz = dozen.

a. Price for grains and oilseeds are from USDA, World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE), September 12November 8, 2018. Calendar year data are for the first year. For example, 2018-2019 = 2018.—= no value, and USDA's out-year 2019-2020 crop price forecasts will first appear in the May 2019 WASDE. Soybean and livestock product prices are from USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service: soybean oil—Decatur, IL, cash price, simple average crude; soybean meal—Decatur, IL, cash price, simple average 48% protein; choice steers—Nebraska, direct 1,100-1,300 lbs.; barrows/gilts—national base, live equivalent 51%-52% lean; broilers—wholesale, 12-city average; eggs—Grade A, New York, volume buyers; and milk—simple average of prices received by farmers for all milk.

b. Data for 2018-2019 are USDA forecasts. Data for 2019-2020 are USDA projections.

c. PercentPercentage change from 2016-20172017 to 2018, calculated using the difference from the midpoint of the range for 2017-20182018-2019 with the estimate for 2016-20172017-2018.

d. PercentPercentage change from 2017- to 2018, calculated using the difference from the midpoint of the range for 2018-2019 with the estimate for 2017-2018.

e. Loan rate and reference prices are for the 2017-2018 market year. See CRS Report R43076, The 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79): Summary and Side-by-Side.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For both national and state-level farm income, see ERS, "U.S. and State Farm Income and Wealth Statistics," http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/farm-income-and-wealth-statistics.aspx. |

||||||

| 2. |

ERS, "Farm Structure and Organization," http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-structure-and-organization.aspx; and "Farm Household Well-Being," http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being.aspx. |

||||||

| 3. |

The material presented in the report is drawn primarily from the 2018 Farm Sector Income Forecast of ERS at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-sector-income-finances/farm-sector-income-forecast/. |

||||||

| 4. |

CRS Report R45310, Farm Policy: USDA's Trade Aid Package, by |

||||||

| 5. |

ERS, Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade, AES- |

||||||

| 6. |

USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Winter Wheat and Canola Seedings¸ January 12, 2018. |

||||||

| 7. |

World Agricultural Outlook Board (WAOB), USDA, World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE), |

||||||

| 8. |

The marketing year varies slightly with each agricultural commodity, but it tends to begin at harvest and end before the next year's harvest. For example, the marketing year for corn planted and harvested in 2018 begins September 1, 2018, and ends August 31, 2019. |

||||||

| 9. |

CRS Insight IN10943, Escalating Tariffs: Timeline, coordinated by Brock R. Williams; and CRS Insight IN10880, China's Retaliatory Tariffs on Selected U.S. Agricultural Products, by Jenny Hopkinson.

CRS Report R45310, Farm Policy: USDA's Trade Aid Package, by Randy Schnepf et al. ERS, Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade, AES-106, November 29, 2018. NASS, Cattle, January 31, 2018. | ||||||

|

WAOB, USDA, WASDE, Table—U.S. Quarterly Animal Product Production, |

|||||||

|

J. Mintert, "Cattle Inventory Growth Slowing Down, but Beef Production Still Increasing," farmdoc daily, vol. 8, no. 18, February 5, 2018. |

|||||||

| 12. |

USDA's August 30, 2018, farm income projections do not consider the effects of Hurricane Florence on North Carolina hog and poultry production. |

||||||

|

Feed costs—at 30% to 80% of variable costs—are generally the largest cost component in livestock operations. |

|||||||

|

Broilers are chickens raised for meat and contrasts with layers, which are chickens retained for egg production. |

|||||||

|

WAOB, USDA, WASDE, Table—U.S. Quarterly Prices for Animal Products, |

|||||||

|

See CRS In Focus IF10195, U.S. Dairy Programs After the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79). |

|||||||

| 17. |

CRS Insight IN10943, Escalating Tariffs: Timeline and Potential Impact, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Insight IN10880, China's Retaliatory Tariffs on Selected U.S. Agricultural Products, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

| 18. |

CRS Report R45310, Farm Policy: USDA's Trade Aid Package, by [author name scrubbed] et al. |

||||||

| 19. |

Miscellaneous livestock includes aquaculture, sheep and lambs, honey, mohair, wool, pelts, and other animal products. |

||||||

| 20. |

|

||||||

| 21. |

Fiscal year payments generally involve outlay commitments incurred during the previous crop year. For example, FY2018 disaster assistance payments are primarily related to disasters for crops that were grown and harvested in 2017. See CRS Report RS21212, Agricultural Disaster Assistance, for information on available farm disaster programs. |

||||||

| 22. |

For details see CRS Report R43448, Farm Commodity Provisions in the 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79).

|

||||||

|

Local and regional land rental rates may vary substantially from the national average. |

|||||||

|

The methodology is described at ERS, "U.S. Export Share of Production," https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/international-markets-us-trade/us-agricultural-trade/. |

|||||||

|

ERS, "Farm Household Well-Being," http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-household-well-being.aspx. |