Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention

Changes from August 24, 2018 to March 21, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Background

- The War in Yemen: Latest Developments

- The Battle for Hudaydah

- Houthis Threaten Commercial Shipping in the Red Sea

- International Involvement in the Conflict

- Yemen at the United Nations

- Iranian Support to the Houthis

- Saudi Arabia and U.S. Support for the Coalition

- Coalition Air Strikes and Civilian Casualties

- Restrictions on the Flow of Commercial Goods and Humanitarian Aid

- The United Arab Emirates: Southern Yemen and Combatting Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

- UAE and Southern Separatists

- UAE and Countering AQAP

- The Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen

- U.S. Foreign Aid to Yemen

- U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Yemen

- Where is the Yemen Conflict Heading?

Figures

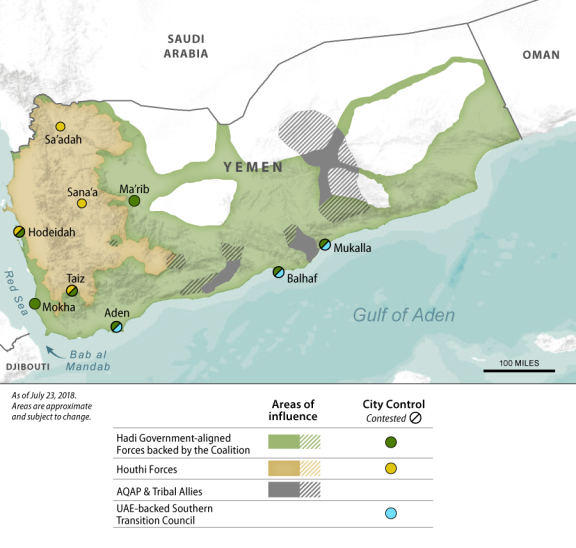

- Figure 1. Lines of Control in Yemen

- Figure 2. Map of Hudaydah

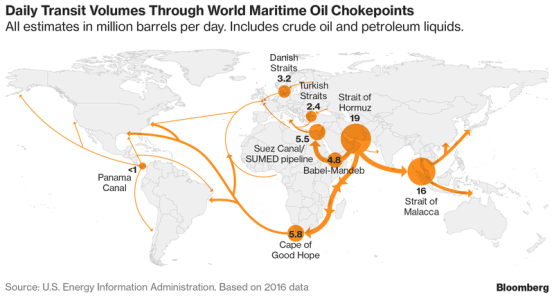

- Figure 3. Oil Transiting through Maritime Chokepoints

- Figure 4. Martin Griffiths, New U.N. Special Envoy for Yemen

- Figure 5. Houthi-Saleh Forces Display the "Burkan-2" Missile

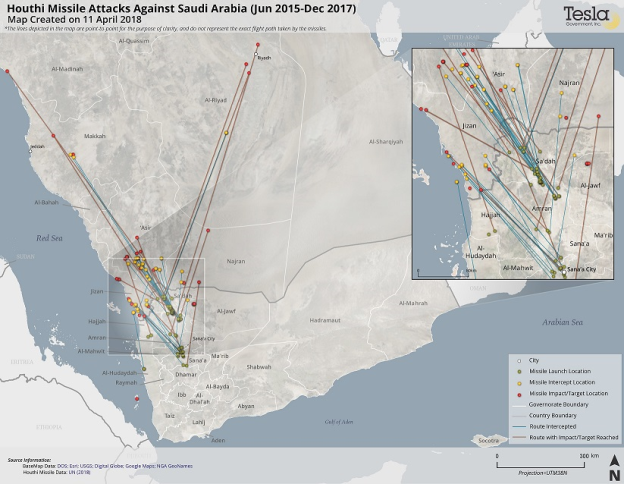

- Figure 6. Houthi Missile Attacks against Saudi Arabia: 2015-2017

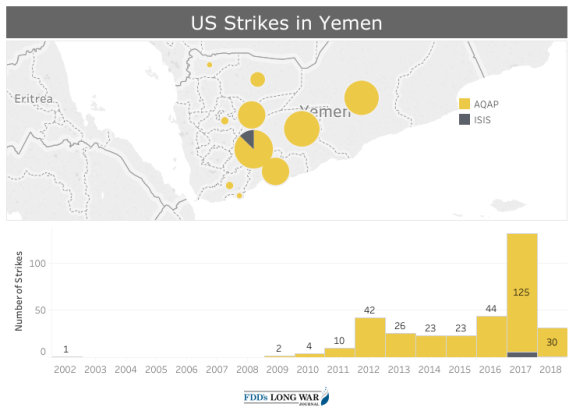

- Figure 7. U.S. Air Strikes in Yemen

Tables

- Table 1. Pledges for U.N. 2018 Humanitarian Appeal for Yemen

- Table 2. U.S. Humanitarian Response to the Complex Crisis in Yemen: FY2015-FY2018

- Table 3. U.S. Bilateral Aid to Yemen: FY2016-FY2017

- Recent U.S. Policy

- Iranian Support to the Houthis

- Saudi Arabia and U.S. Support for the Coalition

- U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Yemen

- Yemen's Humanitarian Crisis

- Humanitarian Conditions and Assistance

- Food Insecurity and the Depreciation of Yemen's Currency

- Restrictions on the Flow of Commercial Goods and Humanitarian Aid

- Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH)

- Where is the Yemen Conflict Heading?

- Table 1. Yemen Timeline

- Table 2. U.S. Humanitarian Response to the Complex Crisis in Yemen: FY2015-FY2018

Figures

Tables

Summary

This report provides information on the ongoing crisis in Yemen. Now in its fourthfifth year, the war in Yemen shows no signs of abating. On June 12, 2018, the Saudi-led coalition, a multinational grouping of armed forces led primarily by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), launched Operation Golden Victory, with the aim of retaking the Red Sea port city of Hudaydah. The coalition also has continued to conduct air strikes inside Yemen. The war has killed thousands of Yemenis, including combatants as well as civilians, and has significantly damaged the country's infrastructure. According to the United Nations (U.N.) High Commissioner for Human Rights, from the start of the conflict in March 2015 through August 9, 2018, the United Nations documented "a total of 17,062 civilian casualties—6,592 dead and 10,470 injured." This figure may vastly underestimate the war's death toll.

Although both the Obama and Trump Administrations have called for a political solution to the conflict, the war's combatants still appear determined to pursue military victory. The two sides alsoThe war has killed thousands of Yemenis, including combatants as well as civilians, and has significantly damaged the country's infrastructure. The difficulty of accessing certain areas of Yemen has made it problematic for governments and aid agencies to count the war's casualties. One U.S. and European-funded organization, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), estimates that 60,000 Yemenis have been killed since January 2016.

Though fighting continues along several fronts, on December 13, 2018, Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General for Yemen Martin Griffiths brokered a cease-fire centered on the besieged Red Sea port city of Hudaydah, Yemen's largest port. As part of the deal, the coalition and the Houthis agreed to redeploy their forces outside Hudaydah city and port. The United Nations agreed to chair a Redeployment Coordination Committee (RCC) to monitor the cease-fire and redeployment. On January 16, the United Nations Security Council (UNSCR) passed UNSCR 2452, which authorized (for a six-month period) the creation of the United Nations Mission to support the Hudaydah Agreement (UNMHA), of which the RCC is a significant component. As of late March 2019, the Stockholm Agreement remains unfulfilled, although U.N. officials claim that the parties have made "significant progress towards an agreement to implement phase one of the redeployments of the Hudayda agreement."

Although both the Obama and Trump Administrations have called for a political solution to the conflict, the two sides in Yemen appear to fundamentally disagree over the framework for a potential political solution. The Saudi-led coalition demands that the Houthi militia disarm, relinquish its heavy weaponry (ballistic missiles and rockets), and return control of the capital, Sanaa, to the internationally recognized government of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who is in exile in Saudi Arabia. The coalition citesasserts that there remains international consensus for these demands, insisting that the conditions laid out in United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2216 (April 2015) should form the basis for a solution to the conflict. The Houthis reject UNSCR 2216 and seem determined to outlast their opponents while consolidating their control over northern Yemen. Since the December 2017 Houthi killing of former presidentPresident Ali Abdullah Saleh, a former Houthi ally, there is no apparent single Yemeni rival to challenge Houthi rule in northern Yemen.

The prospects for returning to a unified Yemen remain dim. According to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen, "The authority of the legitimate Government of Yemen has now eroded to the point that it is doubtful whether it will ever be able to reunite Yemen as a single country." While the country's unity is a relatively recent historical phenomenon (dating to 1990), the international community had widely supported the reform of Yemen's political system under a unified government just a few years ago. In 2013, Yemenis from across the political spectrum convened a National Dialogue Conference aimed at reaching broad national consensus on a new political order. However, in January 2014 it ended without agreement, and the Houthis launched a war.

The situation in Yemen is considered one of the world's worst humanitarian disasters. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), out of a total population of nearly 30 million people, 22.2 million Yemenis are in need of humanitarian assistance. Since March 2015, the United States has been the largest contributor of humanitarian aid to Yemen.

According to the United Nations, Yemen's humanitarian crisis is the worst in the world, with close to 80% of Yemen's population of nearly 30 million needing some form of assistance. Two-thirds of the population is considered food insecure; one-third is suffering from extreme levels of hunger; and the United Nations estimates that 230 out of Yemen's 333 districts are at risk of famine. In sum, the United Nations notes that humanitarian assistance is "increasingly becoming the only lifeline for millions of Yemenis."

For additional information on Yemen, including a summary of relevant legislation, please see CRS Report R45046, The War in Yemen: A Compilation of Legislation in the 115th Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]Congress and the War in Yemen: Oversight and Legislation 2015-2019, by Jeremy M. Sharp and Christopher M. Blanchard.

Background

Central governance in Yemen, embodied by the decades-long rule of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, began to unravel in 2011, when political unrest broke out throughout the Arab world. Popular youth protests in Yemen were gradually supplanted by political elites jockeying to replace then-President Saleh. Ultimately, infighting among various centers of Yemeni political power broke out in the capital, and government authority throughout the country eroded. Soon, militias associated with Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) seized territory in one southern province. Concerned that the political unrest and resulting security vacuum were strengthening terrorist elements, the United States, Saudi Arabia, and other members of the international community attempted to broker a political compromise. A transition plan was brokered, and in 2012 former Vice President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi became president.

With the support of the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the United Nations Security Council, President Hadi attempted to reform Yemen's political system. Throughout 2013, key players convened a National Dialogue Conference aimed at reaching broad national consensus on a new political order. However, in January 2014 it ended without agreement.

One antigovernment group in particular, the northern Yemeni Houthi movement, sought to use military force to reshape the political order. Within weeks of the National Dialogue Conference concluding, it launched a military offensive against various tribal allies of President Hadi. The Houthi were joined by the forces still loyal to former President Saleh, creating an alliance of convenience that was a formidable opponent to President Hadi and his allies.

|

Who are the Houthis? The Houthi movement (also known as Ansar Allah or Partisans of God) is a predominantly Zaydi Shiite revivalist political and insurgent movement. Yemen's Zaydis take their name from their fifth Imam, Zayd ibn Ali, grandson of Husayn. Zayd revolted against the Umayyad Caliphate in 740, believing it to be corrupt, and to this day, Zaydis believe that their imam (ruler of the community) should be both a descendent of Ali (the cousin and son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad) and one who makes it his religious duty to rebel against unjust rulers and corruption. A Zaydi state (or Imamate) was founded in northern Yemen in 893 and lasted in various forms until the republican revolution of 1962. Yemen's modern imams kept their state in the Yemeni highlands in extreme isolation, as foreign visitors required the ruler's permission to enter the kingdom. Although Zaydism is an offshoot of Shia Islam, its legal traditions and religious practices are similar to Sunni Islam. |

In 2014, Houthi militants took over the capital of Sanaa (also spelled Sana'a) and violated several power-sharing arrangements. In 2015, Houthi forces advanced southward from the capital all the way to Aden on the Arabian Sea. In March 2015, after President Hadi, who had fled to Saudi Arabia, appealed for international intervention, Saudi Arabia and a hastily assembled international coalition launched a military offensive aimed at restoring Hadi's rule and evicting Houthi fighters from the capital and other major cities.

In early December 2017, the Houthi-Saleh alliance unraveled, culminating in the killing of former President Saleh on December 4, 2017. Since Saleh's death, the coalition has made military gains. Nevertheless, Houthi forces remain ensconced in northern Yemen and, despite multiple attempts by the United Nations to broker a peace agreement, all sides have remained deadlocked.

The War in Yemen: Latest Developments

The Battle for Hudaydah

Now in its fourth year, the war in Yemen has reached a critical juncture. On June 12, 2018, the Saudi-led coalition, a multinational grouping of armed forces led primarily by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched Operation Golden Victory, with the aim of retaking the Red Sea port city of Hudaydah (alt. sp. Hodeidah, Al Hudaydah). The northern Yemeni armed militia and political movement known as the Houthis (Ansar Allah in Arabic) hold the city and the port, which is crucial for the importation of commercial goods and humanitarian aid into Yemen.1

As various regional groups within Yemen vie for territory, the question of who controls Hudaydah is vital for several reasons. Hudaydah (Yemen's second-largest port after Aden) provides the mostly land-locked northern Houthi-controlled areas with access to the Red Sea. Control of Hudaydah is key to resupplying the Houthi-controlled national capital of Sanaa. The port also is north of the Bab al Mandab strait (alt. sp. Bab al Mandeb, Bab el Mendeb), one of the world's maritime chokepoints.2 Hudaydah also generates revenue for the Houthis, who "tax" imports and control the distribution of food and fuel leaving the port.

Operation Golden Victory, which is spearheaded by the United Arab Emirates, arguably represents the coalition's most concerted effort to change the balance of power on the ground and regain leverage in any future political settlement of the Yemen conflict. For the coalition, retaking Hudaydah could turn the tide of the war in their favor and perhaps even facilitate their gradual disengagement from direct involvement in the conflict.

To date, the coalition has advanced to the outskirts of the city and taken most of Hudaydah airport. However, on June 23 the coalition "paused" its ground advance on the city in order to allow Martin Griffiths, the Special Envoy of the United Nations (U.N.) Secretary-General for Yemen, to negotiate a cease-fire. Hundreds of thousands of civilians remain in Hudaydah, and any urban conflict risks not only incurring high numbers of civilian casualties, but also destroying the port and thus exacerbating food shortages throughout northern Yemen. International humanitarian and aid organizations have been united in calling on the coalition to refrain from attacking Hudaydah and to keep the port open for continued shipments of food and fuel into Yemen. In early August, dozens of Yemenis died in strikes against a fish market and hospital inside Hudaydah city. The coalition has denied conducting these strikes, claiming that dozens of civilians were killed from Houthi mortar fire.3

As of late August 2018, fighting has shifted to districts surrounding the city, such as the Durahmi district and the historic area of Zabid (the town itself is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site). Zabid rests south of Houthi-controlled Hudaydah and north of the coalition-controlled coastal town of Mocha. It is situated on an inland highway (N3) just west of the northern highlands. The coalition has conducted several air strikes near Zabid.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), as of late August, humanitarian organizations have assisted 50,100 displaced households (over 200,000 individuals) from Hudaydah Governorate.4 Approximately 350,000 citizens remain in the city. Hudaydah port has remained open during the fighting, though supplies of electricity and water for residents have been disrupted. Several health facilities have closed, and USAID has provided support to the World Health Organization to increase hospital capacity within Hudaydah.5 Aid agencies also have warned that a cholera outbreak, which is affecting other parts of the country, could occur in Hudaydah as well (if sanitation and water infrastructure are crippled by the fighting.

|

|

Source: Middle East Eye, June 25, 2018. |

Although the coalition has advanced relatively easily northward along the western Yemeni coastal plain toward Hudaydah, most observers believe that an assault on the city itself will be far more problematic. The Houthis have laid landmines on access highways leading into the city and have dug trenches, erected barricades on main roads, and taken positions overlooking the city from the highlands to the east.

Forces under the command of the UAE are leading the operation to retake Hudaydah, although actual UAE soldiers are in an advise- and-assist role. Several Yemeni militias of former soldiers and irregulars are on the front lines, including (1) Republican Guards at the command of Tariq Saleh, the nephew of the late Ali Abdullah Saleh, the longtime president of Yemen who was killed by the Houthis in 2017; (2) the Giants Brigade, a group of southern Yemenis and former Yemeni soldiers; and (3) the Tihama Resistance Forces, a local militia comprised of recent recruits. According to Jane's, these forces may be equipped with "Mine-Resistant Ambush-Protected Vehicles (MRAPs), Leclerc main battle tanks, and UAVs for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), provided by the UAE."6

As of August 2018, U.N. Special Envoy Martin Griffiths continues to try and broker a cease-fire and stave off a coalition assault against Hudaydah. The U.N. envoy plans on hosting consultations in Geneva on September 6 in order to move all sides toward a cease-fire.

Both the coalition and the Houthis remain deadlocked over the issue of the continued Houthi military presence in major urban areas such as Hudaydah and Sanaa. The coalition continues to insist that the Houthis abide by United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 22167 (April 2015), which, among other things, demanded that the Houthis withdraw from all areas seized during the current conflict. The Houthis insist on remaining in seized territory, but have expressed a willingness to allow the United Nations to operate the port of Hudaydah. Houthi leader Abdel Malik al Houthi said, "We told the UN envoy, Martin Griffiths, that we are not rejecting the role of supervision and logistics that the UN wants to hold in the port, but on the condition that the aggression against Hudaydah stops."8

To date, the United States government has supported the mediation efforts of Special Envoy Griffiths while reportedly refusing to increase support to assist Operation Golden Victory.9 As the coalition prepared to launch its initial assault on the outskirts of Hudaydah, U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo issued a press statement noting "I have spoken with Emirati leaders and made clear our desire to address their security concerns while preserving the free flow of humanitarian aid and life-saving commercial imports. We expect all parties to honor their commitments to work with the UN Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary General for Yemen on this issue, support a political process to resolve this conflict, ensure humanitarian access to the Yemeni people, and map a stable political future for Yemen."10

Administration officials reportedly did not respond positively to coalition requests for additional U.S. military aid in support of Operation Golden Victory (for more on U.S. involvement with and support for coalition efforts, see "Saudi Arabia and U.S. Support for the Coalition" below). According to the Wall Street Journal, U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis "has privately expressed reservations about the looming operation…. and has voiced concerns that a protracted assault on the port could worsen the humanitarian crisis and undercut American counterterrorism operations in Yemen."11 In early June 2018, an unnamed White House National Security Council staffer told Reuters that "The United States has been clear and consistent that we will not support actions that destroy key infrastructure or that are likely to exacerbate the dire humanitarian situation that has expanded in this stalemated conflict…. We expect all parties to abide by the Law of Armed Conflict and avoid targeting civilians or commercial infrastructure."12

The United States has thus far rejected requests by the UAE for logistics, intelligence, and mine-sweeping operations. According to Pentagon spokesman Marine Major Adrian Rankine Galloway, "'We are not directly supporting the coalition offensive on the port of Hodeida…. The United States does not command, accompany or participate in counter-Houthi operations or any hostilities other than those authorized' against al-Qaida and Islamic State militants in Yemen."13 In its semiannual War Powers letter to Congress, the Administration explained its actions as being restricted to counterterrorism operations and noncombat support to the coalition:

A small number of United States military personnel are deployed to Yemen to conduct operations against al-Qa'ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and ISIS-Yemen. The United States military continues to work closely with the Government of Yemen and regional partner forces to dismantle and ultimately eliminate the terrorist threat posed by those groups. Since the last periodic update report, United States Armed Forces conducted a number of airstrikes against AQAP operatives and facilities in Yemen, and supported the United Arab Emirates- and Yemen-led operations to clear AQAP from Shabwah Governorate. United States Armed Forces also conducted airstrikes against ISIS targets in Yemen. United States Armed Forces, in a non-combat role, have continued to provide military advice and limited information, logistics, and other support to regional forces combatting the Houthi insurgency in Yemen. United States forces are present in Saudi Arabia for this purpose.14

Some Members of Congress have expressed concern over the possibility of a siege of Hudaydah. On June 12, nine Senators wrote a letter to Secretary of State Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mattis saying "We are concerned that pending military operations by the UAE and its Yemeni partners will exacerbate the humanitarian crisis by interrupting delivery of humanitarian aid and damaging critical infrastructure. We are also deeply concerned that these operations jeopardize prospects for a near-term political resolution to the conflict."15 Several weeks later, Senator Robert Menendez, the ranking member on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, placed a hold on a potential U.S. sale of precision guided munitions to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In a June 28 letter to Secretary of State Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mattis, Senator Menendez said, "I am not confident that these weapons sales will be utilized strategically as effective leverage to push back on Iran's actions in Yemen, assist our partners in their own self-defense, or drive the parties toward a political settlement that saves lives and mitigates humanitarian suffering…. Even worse, I am concerned that our policies are enabling perpetuation of a conflict that has resulted in the world's worst humanitarian crisis."16 In August 2018, other Members have written letters to U.S. officials seeking updates on the situation in Hudaydah.17

Houthis Threaten Commercial Shipping in the Red Sea

Since 2016, the Houthis have periodically targeted commercial and military vessels transiting and patrolling the Red Sea using naval mines, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, anti-ship missiles, and waterborne improvised explosive devices (WBIEDs). Some of the weapons used reportedly have been supplied by Iran, including sea-skimming coastal defense cruise missiles.18 As the Saudi-led coalition has advanced along the Red Sea coast toward Hudaydah, the Houthis have repeatedly threatened to increase the frequency of their attacks against commercial shipping vessels in the Red Sea.19

On July 24, 2018, the Houthis targeted two Saudi oil tankers in the Red Sea, damaging one of them. A day later, Saudi Aramco (the national oil company) suspended all oil shipments through the Bab al Mandab Strait, causing shipment delays and a modest, temporary spike in oil prices.20 Days later, the Houthis announced that they would unilaterally halt maritime operations for "a limited time period." Soon thereafter, Saudi Aramco resumed shipments through the Bab al Mandab, though it is unclear what provoked the Houthis to halt additional anti-ship strikes. On August 7, Iran's state-owned media outlet reported that one Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) general said "We (IRGC) told Yemenis [Houthi rebels] to strike two Saudi oil tankers, and they did it."21 Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned that "If Iran will try to block the straits of Bab al-Mandeb, I am certain that it will find itself confronting an international coalition that will be determined to prevent this, and this coalition will also include all of Israel's military branches."22

On August 9, 2018, then-Commander of United States Central Command (CENTCOM) General Votel stated that

the Bab-el-Mandeb is open for business, as far as we're concerned. And I would say it's a major -- it's a major waterway, not just for the United States, but for many countries in terms of moving through that particular area. So one of our key missions here is to ensure freedom of navigation, freedom of commerce, and we will continue to exercise that through the region.23

|

|

|

Source: Bloomberg News. |

International Involvement in the Conflict

Yemen at the United Nations

In March 2018, Martin Griffiths of the United Kingdom assumed the role of Special Envoy of the United Nations (U.N.) Secretary-General for Yemen, replacing Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, who was unable to make headway toward a peace deal, despite multiple attempts. Ahmed ultimately blamed the Houthis for obstructing peace, declaring that their inability to make concessions on security arrangements was the key stumbling block in negotiations.24 On March 15, the U.N. Security Council issued a presidential statement on Yemen, which, among other things, welcomed Griffiths's appointment while calling "upon all parties to the conflict to abandon pre-conditions and engage in good faith with the UN-led process."25

|

|

|

In January 2018, the United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen concluded that Iran was in noncompliance with UNSCR 2216 for failing to prevent the transfer to Houthi forces of Iranian-made short-range ballistic missiles.26 On February 26, 2018, Russia vetoed a draft U.N. Security Council resolution that would have expressed U.N. concern that Iran is in noncompliance with the international arms embargo created by UNSCR 2216. The Security Council did pass a new resolution (UNSCR 2402) that renewed for a year U.N. sanctions first imposed by UNSCR 2140 (2014), such as a travel ban and asset freeze on designated Houthi leaders and the former (and now deceased) President Ali Abdullah Saleh. UNSCR 2402 also renewed the arms embargo against Yemen, first imposed by UNSCR 2216.

Iranian Support to the Houthis

Although Houthi militia forces most likely do not depend on Iran for all of their armaments, financing, and manpower, many observers agree that Iran27 and its Lebanese ally Hezbollah have aided Houthi forces with advice, training, and arms shipments.28 In 2016, one unnamed Hezbollah commander interviewed about his group's support for the Houthis remarked "After we are done with Syria, we will start with Yemen, Hezbollah is already there.... Who do you think fires Tochka missiles into Saudi Arabia? It's not the Houthis in their sandals, it's us."29 In repeated public statements by high-level Saudi officials, Saudi Arabia has cited Iran's illicit support for the Houthis as proof that Iran is to blame for the Yemen conflict. Reports and allegations of Iranian involvement in Yemen have become more frequent as the war has continued, and from Iran's perspective, aiding the Houthis would seem to be a relatively low-cost way of keeping Saudi Arabia mired in the Yemen conflict. However, Iran had few institutionalized links to the Houthis before the civil conflict broke out in 2015, and questions remain about the degree to which Iran and its allies can control or influence Houthi behavior. Iranian aid to the Houthis does not match the scale of its commitments to proxies in other parts of the Middle East, such as in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq.

|

|

|

Source: An image released by the pro Houthi-Saleh SABA News Agency on February 6, 2017, Jane's Defence Weekly, February 8, 2017. |

Prior to the 2015 conflict, the central government in Yemen had acquired variants of Scud-B missiles from the Soviet Union and North Korea. The Houthis took control of these missiles as part of their seizure of the capital. Since 2016, the Houthis have been firing what they call the "Burkan" short-range ballistic missile (claimed range of 500-620 miles) into Saudi Arabia (the latest version is the Burkan-2H). In November 2017, after the Houthis fired a Burkan-2H deep into Saudi Arabian territory, the Saudi-led coalition and U.S. officials said that the Burkan-2H is an Iran-manufactured Qaim missile.30 In a hearing before the House Armed Services Committee, Commander of United States Central Command (CENTCOM) General Votel remarked as follows:

Certainly, as we've seen with Ambassador Haley and her demonstration, most recently, with some of the items recovered from Saudi Arabia, these weapons pose the threat of widening the conflict out of ... Yemen and, frankly, put our forces, our embassy in Riyadh, our forces in the United Arab Emirates at risk, as well as our partners'.... As we look at places like the Bab-el-Mandeb, where we see the introduction of coastal defense cruise missiles, some that have been modified, we know these are not capabilities that the Houthis had. So they have been provided to them by someone. That someone is Iran.31

In the summer of 2018, the United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen provided a confidential report to the United Nations Security Council suggesting that Iran may be continuing to violate the international arms embargo by supplying the Houthis with advanced weaponry. After the U.N. experts visited Saudi Arabia and inspected debris from missiles fired by the Houthis, their report noted that these weapons showed "characteristics similar to weapons systems known to be produced in the Islamic Republic of Iran" and that there was a "high probability" that the missiles were manufactured outside of Yemen, shipped in sections to the country, and reassembled by the Houthis.32

In May 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated five Iranian individuals who have "provided ballistic missile-related technical expertise to Yemen's Houthis, and who have transferred weapons not seen in Yemen prior to the current conflict, on behalf of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF)."33

Saudi Arabia and U.S. Support for the Coalition

For Saudi Arabia, according to one prominent analyst, the Houthis embody what Iran seeks to achieve across the Arab world: that is, the cultivation of an armed nonstate, non-Sunni actor who can pressure Iran's adversaries both politically and militarily (akin to Hezbollah in Lebanon).34 Well before the current conflict began in 2015, Saudi Arabia supported the central government of Yemen in various military campaigns against a Houthi insurgency which began in 2004.35

In 2014, when Houthi militants took over the capital and violated several power-sharing arrangements, Saudi leaders expressed increasing alarm about Houthi advances. In March 2015, after President Hadi, who had fled to Saudi Arabia, appealed for international intervention, Saudi Arabia quickly assembled an international coalition and launched a military offensive aimed at restoring Hadi's rule and evicting Houthi fighters from the capital and other major cities.36 Saudi-led coalition forces began conducting air strikes against Houthi-Saleh forces and imposed strict limits on sea and air traffic to Yemen.

From the outset, Saudi leaders sought material and military support from the United States for the campaign, and in March 2015, President Obama authorized "the provision of logistical and intelligence support to GCC-led military operations," and the Obama Administration announced that the United States would establish "a Joint Planning Cell with Saudi Arabia to coordinate U.S. military and intelligence support." U.S. CENTCOM personnel were deployed to provide related support, and U.S. mid-air refueling of coalition aircraft began in April 2015.37

In the three years since, the Saudi military and its coalition partners have provided advice and military support to a range of pro-Hadi forces inside Yemen, while waging a persistent air campaign against the Houthis and their allies. Saudi ground forces and Special Forces have conducted limited cross-border operations, and Saudi naval forces limit the entry and exit of vessels from Yemen's ports (see "Restrictions on the Flow of Commercial Goods and Humanitarian Aid" below). Separately, a United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM) has operated since May 2016 to assist in validating commercial sea and air traffic in support of the arms embargo imposed by Resolution 2216.

|

The War in Yemen: Have U.S. Forces Been Introduced into Hostilities? There is disagreement as to whether U.S. forces assisting the Saudi-led coalition have been introduced into active or imminent hostilities for purposes of the War Powers Resolution (50 U.S.C Ch. 33). Some Members have claimed that by providing support to the Saudi-led coalition, U.S. forces have been introduced into a "situation where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated" based on the criteria of the War Powers Resolution. The Trump Administration disagrees. The U.S. Defense Department has maintained that "the limited military and intelligence support that the United States is providing to the KSA-led coalition does not involve any introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities for purposes of the War Powers Resolution." On March 20, 2018, the Senate voted to table a motion to discharge the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from further consideration of S.J.Res. 54, a joint resolution that would direct the President to remove U.S. forces from "hostilities in or affecting" Yemen (except for those U.S. forces engaged in counterterrorism operations directed at al Qaeda or associated forces). Two months later, the New York Times reported that in 2017, a small team of Green Berets were deployed to Saudi Arabia's border with Yemen in order to train Saudi ground troops on border security and work with U.S. intelligence to locate Houthi missile sites within Yemen.38 In light of this report, some Members have sought additional clarification on U.S. support for the coalition.39 |

Coalition Air Strikes and Civilian Casualties

Since 2015, the conduct of the Saudi-led air campaign against the Houthis, and U.S. support for its continual operation, has drawn widespread international scrutiny for targeting civilian infrastructure and killing thousands of Yemeni noncombatants. Critics charge that Saudi Arabia in particular should be held accountable for violating international humanitarian law by continually failing to distinguish between combatant targets and innocent civilians. According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), since the conflict began in March 2015 through August 9, 2018, the United Nations has documented "a total of 17,062 civilian casualties—6,592 dead and 10,470 injured. According to (UNHCHR), the majority of these casualties—10,471—were as a result of airstrikes carried out by the Saudi-led Coalition."40

Since March 2015, some of the deadliest Saudi-led coalition air strikes include the following:

- September 2015: Saudi-led coalition air strike hit a wedding party, killing at least 81 civilians;

- March 2016: Saudi-led coalition air strikes hit a market in northwestern Yemen, killing at least 97 civilians and about 10 Houthi fighters;

- October 2016: Saudi-led coalition air strike hit a funeral hall in Sanaa, killing between 130 and 150 people;

- December 2017: In one day, a Saudi-led coalition air strike hit a market in Ta'izz province, killing 54 people, while a second strike killed 14 members of one family in Hudaydah province;

- April 2018: Saudi-led coalition air strike hit a wedding party in Hajjah province, killing more than 20 people;

- August 2018: Saudi-led coalition air strike hit a bus in a market near Dahyan, Yemen, in the northern Sa'dah governorate adjacent to the Saudi border, killing 51 people, 40 of whom were children. The coalition claimed that its air strike was a "legitimate military operation" conducted in response to a Houthi missile attack on the Saudi city of Jizan a day earlier that killed a Yemeni national in the kingdom.

Saudi officials acknowledge that some of their operations have inadvertently caused civilian casualties, while maintaining that their military campaign is an act of legitimate self-defense because of their Yemeni adversaries' repeated, deadly cross-border attacks, including ballistic missile attacks. Saudi strikes have focused on missile-related targets, suspected Houthi fighting units and locations, and senior Houthi leaders. At times, the coalition's Joint Incidents Assessment Team (JIAT) has reviewed air strikes in which civilian casualties were reported. According to one report, in September 2017, the JIAT had uncovered "mistakes in only three of 15 incidents it reviewed, and maintained that the coalition had acted in accordance with international humanitarian law."41 Critics have not accepted such justifications as sufficient. According to one former U.S. official who advised the Saudi government when it launched the JIAT, "It's not enough for them to identify problems. You have to make changes to operations."42

In response to concerns about civilian casualties resulting from Saudi air strikes, the Obama Administration withdrew U.S. personnel from the joint U.S.-Saudi planning cell in June 2016, and later announced that it would suspend planned sales of precision guided munitions to Saudi Arabia.43 In 2017, President Trump announced his intention to proceed with the suspended munitions sales and, after a policy review, directed his Administration "to focus on ending the war and avoiding a regional conflict, mitigating the humanitarian crisis, and defending Saudi Arabia's territorial integrity and commerce in the Red Sea."44 U.S. officials continue to speak in clear terms about what they view as the importance of avoiding civilian casualties and reaching a negotiated solution to the crisis. Still, the Administration's posture on Yemen appears to reflect, to some extent, its policy of placing maximum economic and regional pressure on Iran in order to roll back Iran's regional influence.

|

FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act Certification Requirement Section 1290 of the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA, H.R. 5515/.P.L. 115-232) restricts the use of U.S. funds for in-flight refueling of coalition aircraft until the Administration submits a specific certification regarding coalition operations or issues a waiver and reports to Congress on specified criteria. The restriction does not apply to certain types of operations, including coalition missions related to Al Qaeda and the Islamic State or "related to countering the transport, assembly, or employment of ballistic missiles or components in Yemen." According to the provision, the Administration must certify that the Saudi and Emirati governments are undertaking the following:

With specific regard to Saudi Arabia, the Administration also must certify that "the Government of Saudi Arabia is undertaking appropriate actions to reduce any unnecessary delays to shipments associated with secondary inspection and clearance processes other than UNVIM." The Administration may waive the certification requirement if certain explanatory submissions are made. The provision also includes reporting and strategy submission requirements. |

However, as coalition air strikes have continued to result in civilian casualties, there has been a growing chorus of criticism directed against the U.S. government for its facilitation of the coalition's air campaign. Some lawmakers have suggested that U.S. arms sales and military support to the coalition have enabled alleged violations of international humanitarian law, while others have argued that U.S. support to the coalition improves its effectiveness and thus helps minimize civilian casualties. In support of that latter position, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo has testified before Congress that "It is this administration's judgment that providing [precision guided munitions] actually decreases the risk to civilians."45 Congress has considered but has not enacted proposals to curtail or condition U.S. defense sales to Saudi Arabia, and has conditioned the use of some U.S. funds for some coalition support operations.46

In February 2018, the Acting Department of Defense General Counsel wrote to Senate leaders describing the extent of current U.S. support, and reported that "the United States provides the KSA-led coalition defense articles and services, including air-to-air refueling; certain intelligence support; and military advice, including advice regarding compliance with the law of armed conflict and best practices for reducing the risk of civilian casualties."47 In-flight refueling to the militaries of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is conducted pursuant to the terms of bilateral Acquisition and Cross Servicing Agreements (ACSAs) between the Department of Defense and the respective ministries of each country.48

In subsequent testimony before Congress, U.S. defense officials have noted that while the United States refuels Saudi aircraft and provides advice on targeting techniques, CENTCOM does not track coalition aircraft after they are refueled and does not provide advice on specific targets.49 U.S. refueling support may enable Saudi and coalition aircraft to remain over Yemeni airspace for prolonged periods of time. This may give coalition forces an opportunity to gather additional intelligence to improve the precision of strikes, but also may create opportunities to conduct so-called "dynamic" strikes against emergent, nonfixed targets for which detailed strike preparations and assessments have not been made.50 In an April 2018 Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing on Yemen, Robert S. Karem, Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, responded to questions on the U.S. role in the Saudi-led coalition's air campaign:

It's correct that we do not monitor and track all of the Saudi aircraft aloft over Yemen. We have limited personnel and assets in order to do that and CENTCOM's focus [sic] on our own operations in Afghanistan in Iraq and in Syria….I think the assessment of our Central Command is that the Saudi and Emirati targeting efforts have improved with the steps that they have taken. We do not have perfect understanding, because we're not using all of our assets to monitor their aircraft. But we do get reporting from the ground on what is taking place inside Yemen.51

That same month, when faced with similar questions on Saudi targeting practices in Yemen, General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the following:

I think mitigating the risk of civilian casualties with strikes is probably two issues. There's a cultural issue, and then there's a technical issue. And I think we've had a positive impact with the Saudis in both regards, by the advising and assisting we have been doing. We are co-located with them in their operations centers, to help them develop the techniques and tactics that will allow them to conduct strikes while mitigating civilian casualties. And I also think there's been a positive effect of the relationship that we've built with the Saudis over time, and the training, to effect the changes in the culture that would have them take that into account when conducting military operations. So it's a long, plodding process…. but I think it's paying dividends over time.52

In August 2018, in response to a media inquiry on U.S. support for the Saudi air campaign, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said the following:

We do not do dynamic targeting for them, where they're in the air and they come under fire with missiles being fired, that sort of thing, and they're turning on late-breaking intelligence. We try to assist them in how they protect certain locations, that sort of thing.53

Several Members of Congress have written to the Administration seeking additional information regarding U.S. operations in the wake of the August 2018 coalition strike at Dahyan.54 Several Senators also have submitted an amendment to the FY2019 Defense Department appropriations act (H.R. 6157) that would prohibit the use of funds made available by the act to support the Saudi-led coalition operations in Yemen until the Secretary of Defense certifies in writing to Congress that the coalition air campaign "does not violate the principles of distinction and proportionality within the rules for the protection of civilians." The provision would not apply to support for ongoing counterterrorism operations against Al Qaeda and the Islamic State in Yemen.

Restrictions on the Flow of Commercial Goods and Humanitarian Aid

One of the key aspects of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2216 is that it authorizes member states to prevent the transfer or sale of arms to the Houthis and also allows Yemen's neighbors to inspect cargo suspected of carrying arms to Houthi fighters. In March 2015, the Saudi-led coalition imposed a naval and aerial blockade on Yemen, and ships seeking entry to Yemeni ports required coalition inspection, leading to delays in the off-loading of goods and increased insurance and related shipping costs. Since Yemen relies on foreign imports for as much as 90% of its food supply, disruptions to the importation of food exacerbate already strained humanitarian conditions resulting from war.

In order to expedite the importation of goods while adhering to the arms embargo, the European Union, Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States formed the U.N. Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM), a U.N.-led operation designed to inspect incoming sea cargo to Yemen for illicit weapons. UNVIM, which began operating in February 2016, can inspect cargo, while also ensuring that humanitarian aid is delivered in a timely manner.

However, Saudi officials argue that coalition-imposed restrictions and strict inspections of goods and vessels bound for Yemen are still required because of Iranian weapons smuggling to Houthi forces. Saudi officials similarly argue that the delivery of goods to ports and territory under Houthi control creates opportunities for Houthi forces to redirect or otherwise exploit shipments for their material or financial benefit.55

After a Houthi-fired missile with alleged Iranian origins landed deep inside Saudi Arabia in November 2017, the coalition instituted a full blockade of all of Yemen's ports, including the main port of Hudaydah, exacerbating the country's humanitarian crisis. The White House issued four press statements on the conflict between November 8 and December 8, including a statement on December 6 in which President Trump called on Saudi Arabia to "completely allow food, fuel, water, and medicine to reach the Yemeni people who desperately need it. This must be done for humanitarian reasons immediately."56

On December 20, 2017, the Saudi-led coalition announced that it would end its blockade of Hudaydah port for a 30-day period and permit the delivery of four U.S.-funded cranes to Yemen to increase the port's capability to off-load commercial and humanitarian goods.57 The next day, the White House issued a statement welcoming "Saudi Arabia's announcement of these humanitarian actions in the face of this major conflict."58

The United Arab Emirates: Southern Yemen and Combatting Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

As a key member of the Saudi-led coalition, the UAE has focused its intervention in Yemen on the southern and western Yemeni coasts, where UAE Special Forces have allied themselves with various local powerbrokers in order to retake territory seized either by the Houthis or Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Unlike Saudi Arabia, the UAE has sought relationships with southern separatist groups and has nominally distanced itself both from Yemen's main Sunni Islamist party (Al Islah) and from President Hadi himself. The UAE has lost more than 100 soldiers in the Yemen operation, to date.

UAE and Southern Separatists

In the southern port city of Aden, forces allied with President Hadi have repeatedly clashed with southern separatists who have received backing from the UAE. Hadi-UAE tensions are multifaceted, as the sides disagree over how closely to embrace Al Islah and how closely to work with southern separatists, who seek either greater southern autonomy or the restoration of an independent state in southern Yemen. In the spring of 2017, the UAE supported Yemeni General Aidarous al Zubaidi's formation of the Southern Transitional Council (STC) after Hadi dismissed him as Aden's governor.

Although President Hadi has temporarily relocated Yemen's internationally recognized government to the port city of Aden, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) effectively controls the city through the presence of its own troops or allied tribal militia (known as the Southern Belt or Al Hizam in Arabic). The UAE controls Aden's airport and seaport, and has invested in rebuilding infrastructure. President Hadi's only personally loyal military force in Aden is the Presidential Protection Force, which reportedly is relatively small compared to UAE-allied forces.59

Periodic clashes between pro-Hadi forces and UAE-backed forces have occurred, and in January 2018, the STC seized control of most of Aden from Hadi's troops in just three days. The UAE and Saudi Arabia intervened in order to ensure that the STC remains committed to the larger fight against the Houthis. After the fighting subsided, the STC declared that it would remain committed to the coalition's military operations against the Houthis and handed back military installations to Hadi's forces. Nevertheless, it appears that Hadi has a government in name only and that, on the ground, power resides in the hands of the STC.

Amnesty International has charged the UAE and Yemeni forces loyal to the Emirates with running clandestine prisons in the south where detainees have been tortured. Amnesty International also has documented cases of enforced disappearance.60 UAE officials have denied these allegations. Section 1274 of the FY2019 NDAA (H.R. 5515/P.L. 115-232) requires the Secretary of Defense to conduct a review of related allegations and report to the congressional defense committees within 120 days.

UAE and Countering AQAP

The United Arab Emirates also has played a key role in countering AQAP throughout southern Yemen through both direct military intervention and the buildup of local proxies to hold territory liberated from AQAP. In April 2016, U.S. Special Operations Forces in Yemen reportedly worked with the UAE to defeat AQAP fighters at the port of Mukalla. As part of that operation, the UAE formed a local militia known as the Hadrami Elite Forces, who continue to receive salaries from the Emirates in exchange for holding the coastal town. UAE personnel also have trained, equipped, and paid a 3,000-man provincial militia in Shabwa governorate called the Shabwani Elite Forces to combat local AQAP militants.61 The UAE claims that it has "trained and equipped some 60,000 Yemeni fighters, 30,000 of whom were directly involved in the fight against Al-Qaeda."62 However, according to one Associated Press report, the UAE also has paid fighters from Ansar al Sharia (designated by the State Department in 2012 as an alias for AQAP) to join UAE-backed Yemeni groups.63 In response to this report, one UAE general remarked, "You can't kill your way to victory against AQAP in Yemen with drones and SF [special forces] raids…. Ultimately, it's a competition for the people's support."64

The Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), out of a total population of nearly 30 million people, 22.2 million Yemenis are in need of humanitarian assistance. Although food is available to purchase in markets, the war has devastated the Yemeni economy. Government employees have gone unpaid, and the currency has depreciated significantly (losing 126% of its prewar value). Food prices have skyrocketed, with the World Food Program reporting in May 2018 that the national average retail prices of wheat flour, sugar, vegetable oil, and red beans were 60%, 42%, 39%, and 104% higher than in the prewar period, respectively.65 As a result of food becoming unaffordable for many Yemenis, UN OCHA reports that 17.8 million are food insecure and 8.4 million people are severely food insecure and at risk of starvation.66

Yemen also is experiencing the world's largest ongoing cholera outbreak. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that from late April 2017 to July 2018, there have been 1,115,378 suspected cholera cases and 2,310 associated deaths.67 Cholera is a diarrheal infection that is contracted by ingesting food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Yemen's water and sanitation infrastructure have been devastated by the war. Basic municipal services such as garbage collection have deteriorated and, as a result, waste has gone uncollected in many areas, polluting water supplies and contributing to the ongoing cholera outbreak. In addition, international human rights organizations have accused the Saudi-led coalition of conducting air strikes that have unlawfully targeted civilian infrastructure, such as water wells, bottling facilities, health facilities, and water treatment plants. UN OCHA reports that 16 million Yemenis currently lack access to safe water and sanitation. In August 2018, Yemeni authorities launched an oral cholera vaccination campaign, which has vaccinated 375,000 people since it began.

On April 3, 2018, the United Nations, Switzerland, and Sweden cohosted a high-level pledging conference in Geneva to fund the U.N.'s 2018 Humanitarian appeal, which aims to raise $2.96 billion. Donors pledged approximately $2 billon at the conference, $930 million of which came from the combined pledges of Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The United States pledged $87 million and urged "all parties to this conflict to allow unhindered access for all humanitarian and commercial goods through all points of entry into Yemen and throughout the country to reach the Yemenis in desperate need."68

|

Country |

Pledge |

|

Saudi Arabia |

$500.0 million |

|

United Arab Emirates |

$500.0 million |

|

Kuwait |

$250.0 million |

|

United Kingdom |

$239.7 million |

|

European Commission |

$132.7 million |

|

United States |

$87.00 million |

|

UN's Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) |

$50.00 million |

|

Germany |

$40.70 million |

|

Japan |

$38.80 million |

|

Others (31 pledges) |

$161.0 million |

Source: UN OCHA, April 3, 2018.

U.S. Foreign Aid to Yemen

Since March 2015, the United States has been the largest contributor of humanitarian aid to Yemen, with more than $1.46 billion in U.S. funding provided since FY2015 (Table 2). Funds were provided to international aid organizations from USAID's Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA), USAID's Food for Peace (FFP), and the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM). The United States has provided a total of $321 million in humanitarian assistance in FY2018.

Table 2. U.S. Humanitarian Response to the Complex Crisis in Yemen: FY2015-FY2018

(in millions of dollars)

|

Account |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

|

IDA (USAID/OFDA) |

76.844 |

81.528 |

227.996 |

105.769 |

|

FFP (UDAID/FFP) |

56.672 |

196.988 |

369.629 |

201.388 |

|

MRA (State/PRM) |

45.300 |

48.950 |

38.125 |

13.900 |

|

Total |

178.816 |

327.466 |

635.750 |

321.057 |

Source: Yemen, Complex Emergency—USAID Factsheets.

|

Account |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|

Economic Support Fund |

29.300 |

14.700 |

|

Development Assistance |

- |

25.000 |

|

Global Health |

5.000 |

- |

|

Total |

34.300 |

39.700 |

Source: USAID.

U.S. Counterterrorism Operations in Yemen

As the Saudi-led coalition's campaign against the Houthis continues and Yemen fragments, the United States not only has sustained counterterrorism operations against Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and various affiliates of the Islamic State, but also markedly increased the tempo of strikes in 2017, though 2018 has seen a relative slowdown. According to the Long War Journal and using data provided to it by CENTCOM, in 2018, U.S. strikes in Yemen have "decreased precipitously from last year's record high of 131, which was more than the previous four years combined. At the current rate, roughly half as many will be conducted this year. That said, with 31 strikes thus far in 2018, the United States is on pace to surpass the strike total for each previous year, except 2017."69

Some observers contend that AQAP's power inside Yemen has diminished considerably as a result of losses sustained from U.S. counterterrorism operations and of competing Yemeni factions vying for supremacy. According to Gregory D. Johnsen, resident scholar at the Arabia Foundation, "AQAP is weaker now than it has been at any point since it was formed in 2009."70

In August 2018, U.S. officials claimed that one of the most high-value targets in the AQAP organization, bombmaker Ibrahim al Asiri, had been killed in a U.S. air strike last year. Asiri was a Saudi national who was believed to have created the explosive devices used in the 2009 Christmas Day attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253, in a 2009 attack against former Saudi Arabian intelligence chief Mohammed bin Nayef, and in the October 2010 air cargo packages destined for Jewish sites in Chicago.

To date, two American soldiers have died in the ongoing U.S. counterterrorism campaign against AQAP and other terrorists inside Yemen. In January 2017, Ryan Owens, a Navy SEAL, died during a counterterrorism raid in which between 4 and 12 Yemeni civilians also were killed, including several children, one of whom was a U.S. citizen. The raid was the Trump Administration's first acknowledged counterterror operation. In August 2017, Emil Rivera-Lopez, a member of the elite 160th Special Operation Aviation Regiment, died when his Black Hawk helicopter crashed off the coast of Yemen during a training exercise.

|

|

|

Source: Long War Journal, Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. |

Where is the Yemen Conflict Heading?

The Saudi and Emirati offensive against Hudaydah would seem to represent the coalition's determination to deliver a decisive blow to the Houthis in order to allow for the Gulf monarchies to gradually wind down war operations. To date, the coalition is proceeding methodically, choosing a strategy of encirclement around the port city in order to bring maximum pressure to bear on Houthi forces remaining inside Hudaydah. At the same time, it also appears that the coalition is keenly aware of the international community's broad desire to keep the port itself functional in order to stave off further humanitarian suffering.

Whether the coalition can militarily isolate the Houthis in Hudaydah is unclear. Throughout the conflict, the Houthis have demonstrated a willingness to incur losses without compromising their goal to dominate northern Yemen. Nevertheless, the coalition appears to be positioning a range of land, air, and sea assets on the outskirts of the city, and if Martin Griffiths, the Special Envoy of the United Nations (U.N.) Secretary-General for Yemen, is unable to convene negotiations for a cease-fire, the likelihood of an all-out assault on Hudaydah could increase.

No end to the conflict appears imminent, either through total victory of one side or a compromise solution. The willingness of parties to the conflict, including U.S. partners, to potentially accept less than fully preferred outcomes is not publicly known. Iran, now involved in Yemen in new ways, may prove unwilling to sever ties that vex its Saudi adversaries. Political and military compromise between the coalition and the Houthis could bring fighting to an end, but might also entrench a hostile Houthi movement as a leading force in a new order in Yemen. Further intransigence and aggressive pursuit of maximalist goals by the parties might eventually tip the balance in favor of once side or the other, but would likely impose chronic costs on U.S. partners and lead to continued humanitarian suffering.

The United States has few good choices in Yemen. For the Trump Administration, U.S. officials have supported the continued defense of Saudi Arabia against Houthi missile and rocket strikes, while also openly calling on coalition members to use air power judiciously to minimize civilian casualties. The Administration has argued against congressional attempts to block arms sales or condition U.S. assistance, arguing that continued U.S. assistance is more likely to achieve the objective of limiting civilian casualties and maintaining strategic ties to Gulf partners than a punitive approach. So far, the United States has refrained from providing direct support to the coalition's offensive against Hudaydah. If, however, the coalition attacks inside the city, the Administration could find itself in the difficult position of having to choose between supporting the coalition's attempt to combat the Houthis, an Iranian ally, or being seen as complicit in the further humanitarian suffering of the Yemeni civilian population at the hands of both the Houthis and Saudi-led coalition forces.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

According to figures from the United Nations Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM), in early to mid-July 2018, 61% of all cargo discharged was through Hudaydah port. See United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA), Yemen Humanitarian Update, Covering 10 July-16 July 2018, Issue 21. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, "an estimated 4.8 million b/d of crude oil and refined petroleum products flowed through this waterway [Bab al Mandab] in 2016 toward Europe, the United States, and Asia, an increase from 3.3 million b/d in 2011. The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is 18 miles wide at its narrowest point, limiting tanker traffic to two 2-mile-wide channels for inbound and outbound shipments. Closure of the Bab el-Mandeb could keep tankers originating in the Persian Gulf from reaching the Suez Canal or the SUMED Pipeline." See EIA, "Three important oil trade chokepoints are located around the Arabian Peninsula," August 4, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

"Dozens of Dead in Yemen, and Blame Pointing in Both Directions," New York Times, August 6, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. |

UN OCHA, Yemen Humanitarian Update, Covering August 9-15, 2018, Issue 24. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. |

USAID, Yemen - Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #9, Fiscal Year (FY) 2018, July 13, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. |

"Fragmentation of Yemeni Conflict Hinders Peace Process," Jane's Intelligence Review, June 5, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. |

On April 14, 2015, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 2216, which imposed sanctions on individuals undermining the stability of Yemen and authorized an arms embargo against the Houthi-Saleh forces. It also demanded that the Houthis withdraw from all areas seized during the current conflict, relinquish arms seized from military and security institutions, cease all actions falling exclusively within the authority of the legitimate Government of Yemen, and fully implement previous council resolutions. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. |

"Yemen Rebel Leader willing to give UN Control of Key Port," Agence France Presse, July 17, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. |

After a meeting between Griffiths and U.S. Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo on July 19, the U.S. State Department noted that during the meeting, "the Secretary underscored his support for the Special Envoy's initiative and expressed the hope that all sides can work toward a comprehensive political agreement that brings peace, prosperity, and security to Yemen." See U.S. State Department, Secretary Pompeo's Meeting with UN Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen Martin Griffiths, Readout, Office of the Spokesperson, Washington, DC, July 19, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. |

U.S. Department of State, Statement by Secretary Pompeo on Developments in Hudaydah, Office of the Spokesperson, June 11, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. |

"U.S. Expands Its Role in Yemen Fighting," Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. |

"U.S. warns United Arab Emirates against Assault on Yemeni Port Hodeidah," Reuters, June 5, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. |

"UAE: US rejects Military Aid Request in Yemen Port Assault," Associated Press, June 14, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. |

Text of a Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, June 8, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. |

Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Ranking Member's Press, Menendez, Corker, Murphy, Young, Colleagues raise Concerns about Imminent Military Operations at Hudaydah, Yemen," June 12, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. |

Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Ranking Member's Press, Menendez Demands more Answers from Trump Admin before letting Arms Sales to United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia move forward," June 28, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. |

"Yemeni Houthis fire at ship with Iranian-supplied missile," Threat Matrix, Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, October 5th, 2016. See also, "This Could Be Why Rebel Missiles Keep Missing U.S. Warships," Esquire, October 13, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. |

"Houthi Threat to Target International Shipping indicates growing Marine Risks in southern Yemeni Red Sea," Jane's Country Risk Daily Report, January 12, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20. |

"Saudi Arabia halts Oil Exports in Red Sea Lane after Houthi Attacks," Reuters, July 25, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. |

IRGC Claims General Who Spilled The Beans Is A 'Retired' Officer," Radio Farda, August 8, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. |

"Israel warns Iran of Military Response if it closed key Red Sea Strait," Reuters, August 1, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23. |

U.S. Department of Defense, Media Availability with General Joseph L. Votel, Commander, U.S. Central Command, in the Pentagon, Department of Defense Documents, August 9, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24. |

"UN Yemen Envoy: Houthis Scrapped Peace Deal at last Minute," Middle East Eye, February 27, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. |

United Nations Security Council, 8205th Meeting, SC/13250, Amid Deteriorating Conditions in Yemen, Security Council Presidential Statement Calls for Humanitarian Access, Strict Adherence to Embargo, March 15, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. |

op.cit., United Nations Panel of Experts on Yemen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. |

According to the U.S. intelligence community, "Iran's support to the Houthis further escalates the conflict and poses a serious threat to US partners and interests in the region. Iran continues to provide support that enables Houthi attacks against shipping near the Bab al Mandeb Strait and land-based targets deep inside Saudi Arabia and the UAE." See Office of the Director for National Intelligence, Testimony Prepared for Hearings on Worldwide Threats, February 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28. |

For example, see the following: "Report: Bombs disguised as Rocks in Yemen show Iranian Aid," Associated Press, March 26, 2018; "Iran Steps up Support for Houthis in Yemen's War – Sources," Reuters, March 21, 2017; "Maritime Interdictions of Weapon Supplies to Somalia and Yemen: Deciphering a Link to Iran," Conflict Armament Research, November 2016; "U.S. Officials: Iran Supplying Weapons to Yemen's Houthi Rebels," NBC News, October 27, 2016; "Exclusive: Iran steps up Weapons Supply to Yemen's Houthis via Oman—Officials," Reuters, October 20, 2016; "Weapons Bound for Yemen Seized on Iran Boat: Coalition," Reuters, September 30, 2015; and "Elite Iranian guards training Yemen's Houthis: U.S. officials," Reuters, March 27, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29. |

"The Houthi Hezbollah: Iran's Train-and-Equip Program in Sanaa," Foreign Affairs, March 31, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30. |

United States Mission to the United Nations, Press Release: "Ambassador Haley on Weapons of Iranian Origin Used in Attack on Saudi Arabia," November 7, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31. |

House Armed Services Committee Hearing on Terrorism and Iran, Full Transcript, February 27, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32. |

"UN panel finds further Evidence of Iran Link to Yemen Missiles,"Agence France Presse, July 30, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury Targets Iranian Individuals Providing Ballistic Missile Support to Yemen's Huthis, May 22, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34. |

Bruce Riedel, "Who are the Houthis, and Why are we at War with them?" Brookings, MARKAZ, December 18, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35. |

During the Cold War, Saudi Arabia's leaders supported northern Yemeni Zaydis as a bulwark against nationalist and leftist rivals, and engaged in proxy war against Egypt-backed Yemeni nationalists during the 1960s. The revolutionary, anti-Saudi ideology of the Houthi movement, which emerged in the 1990s, presented new challenges. In 2009, Saudi Arabia launched a three month air and ground campaign in support of the Yemeni government's Operation Scorched Earth. Saudi Arabia dispatched troops along the border of its southernmost province of Jizan and Sa'dah in an attempt to repel reported Houthi infiltration of Saudi territory. It is estimated that Saudi Arabia lost 133 soldiers in its war against the Houthis. Saudi Arabia agreed to a ceasefire with the Houthis in late February 2010 after an exchange of prisoners and remains. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36. |

President Hadi correspondence with GCC governments printed in U.N. Document S/2015/217, "Identical letters dated 26 March 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Qatar to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of Security Council," March 27, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37. |

Refueling operations began April 7, 2015 according to Department of Defense spokesman Col. Steve Warren. See Andrew Tilghman, "U.S. launches aerial refueling mission in Yemen," Military Times, April 8, 2015. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38. |

"Army Special Forces Secretly Help Saudis Combat Threat From Yemen Rebels," New York Times, May 3, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39. |

See Rep. Khanna leads urgent, Bipartisan call to Sec. Mattis to Avert Famine-Triggering Attack on Yemen's Major Port and Disclose Full U.S. Role in Saudi-Led War, June 13, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40. |

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Press Briefing Notes on Yemen Civilian Casualties, August 10, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 41. |

"Saudi Coalition investigates own Air Strikes, clears itself," Reuters, September 12, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 42. |

"U.S. General urges Saudi Arabia to investigate Airstrike that killed Dozens of Children in Yemen," Washington Post, August 13, 2018. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 43. |

"U.S. withdraws staff from Saudi Arabia dedicated to Yemen planning," Reuters, August 19, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44. |