The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership Program

Changes from August 10, 2018 to September 9, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Overview

- Background

- Evolution of the Program

- Statutory Mission and Activities

- MEP Organization and Structure

- NIST MEP

- MEP Advisory Board

- MEP Centers

- Center Selection

- Criteria

- System-Wide Center Recompetition

- Review Prior to Continued Center Funding

- Center Cost-Share and Term of Eligibility

- Current Status of Cost-Sharing and Term of Eligibility

- Historical Background on Cost-Sharing and Term of Eligibility

- Cost-Sharing

- Term of Eligibility for Funding

- Other MEP-Related Activities

- Business-to-Business Networks

- Competitive Awards Program

- Additional Cooperative Agreements Awarded Competitively

- Embedding MEP Center Staff in Manufacturing USA Institutes

- Other Competitive Awards

- MEP-Assisted Technology and Technical Resource (MATTR) Program

- Value and Utility of Skill Credentials to Manufacturers and Workers

- Completed MEP-Related Activities

- Business-to-Business Networks

- Make it in America Challenge

- Advanced Manufacturing Jobs and Innovation Accelerator Challenge

- Manufacturing Technology Acceleration Centers

AdditionalOther Grants- MEP Strategic Plan

- Annual Report to Congress

- External Reviews and Recommendations

- MEP Advisory Board

- Government Accountability Office

- Congressional Budget Office

- National Academy of Public Administration

- Appropriations and Related Issues

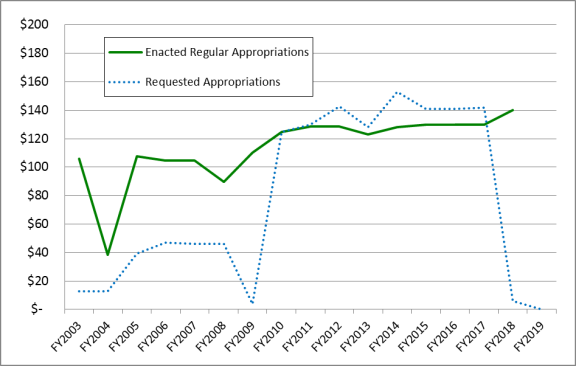

FY2018FY2019 AppropriationsStatus and FY2019and the FY2020 Request- Appropriations and Requests FY2003-

FY2019FY2020

- Use of MEP Appropriations for Center Awards

- Appropriate Role of the Federal Government

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Manufacturing Extension Partnership Program Appropriations, FY2018-FY2019

- Table 2. Requested and Enacted Appropriations for the MEP Program

- Table A-1. Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership Centers

- Table B-1.

First-Year Center Funding Awarded in Round One - Table B-2. First-Year Center Funding Awarded in Round Two

- Table B-3. First-Year Center Funding Awarded in Round Three

- Table B-4. First-Year Center Funding Awarded in Round Four

- Table B-5. Centers Not Competed in Rounds 1-4

Summary

The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) program is a national network of centers established by the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act (P.L. 100-418). MEP centers provide custom services to small and medium-sized manufacturers (SMMs) to improve production processes, upgrade technological capabilities, and facilitate product innovation. Operating under the auspices of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the MEP system includes centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico.

NIST provides funding to support MEP center operations, with matching funds provided by nonfederal sources (e.g., state governments, fees for services). Initially established with a goal of transferring technology developed in federal laboratories to SMMs, MEP shifted its focus in the early 1990s to responding to needs identified by SMMs, including off-the-shelf technologies and business advice. As MEP evolved, its focus shifted to reducing manufacturing costs through lean production, quality, and other programs targeting plant efficiencies and to increasing profitability through growth. Current MEP efforts focus on innovation and growth strategies, cybersecurity, commercialization, lean production, process improvements, workforce training, supply chain optimization, and exporting.

In 2017, NIST completed a system-wide revamp of MEP to better align center funding levels with the national distribution of manufacturing activity and to result in a single center in each state and Puerto Rico. Other objectives included aligning center activities to the NIST MEP strategic plan; aligning center activities with state and local strategies; providing opportunities for new partnering arrangements; and restructuring and reinvigorating the boards of local centers.

As originally conceived, the centers were intended to become self-supporting after six years. The original legislation provided for a 50% federal cost-share for the first three years of operation, followed by declining levels of federal support for the final three years; federal funding after a center's sixth year of operation was prohibited. In 1998, Congress eliminated the prohibition on federal funding after year six. In 2017, Congress authorized NIST to provide up to 50% of the capital and annual operating and maintenance funds required to establish and support a center. Previously, the federal cost-share was limited to 50% for a center's first three years of operation, 40% in year four, and one-third in fifth and subsequent years.

The MEP program has, at times, been included in discussions surrounding termination of federal programs that provide direct support for industry. Invoking the intent of the original legislation, President George W. Bush proposed in his FY2009 budget to eliminate federal funding for MEP and to provide for "the orderly change of MEP centers to a self-supporting basis." Nevertheless, Congress appropriated $110 million for the program. Proponents assert that SMMs play a central role in the U.S. economy and that the MEP system provides assistance not otherwise available to SMMs. Some opponents have asserted that such services are available from other sources and that MEP inappropriately shifts a portion of the costs of these services to taxpayers.

Continued federal support for MEP centers remains a point of contention. In his FY2018 budget, FY2019, and FY2020 budgets, President Trump has sought to eliminate federal support for the MEP program. Congress appropriated $140.0 million for MEP for FY2018 and FY2019. For FY2020, the House-passed appropriations bill included $154.0 million for MEP; the Senate has not yet acted. MEP centers, requesting $6.0 million for the program's "orderly wind down." The House committee-reported appropriations bill included $100 million for MEP, while the Senate committee-reported bill included $130.0 million. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), provides $140.0 million for MEP for FY2018. President Trump has again proposed the elimination of MEP in his FY2019 budget.

As Congress makes appropriation decisions, it may continue to discuss support for MEP in the context of the federal government's role in bolstering innovation and competitiveness, and in the context of the appropriate federal role in such activities.

Overview

The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), a program of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST),1 is a national network of centers that provide custom services to small and medium-sized manufacturers (SMMs)2 to improve production processes, upgrade technological capabilities, and facilitate product innovation.

The MEP mission is "to enhance the productivity and technological performance of U.S. manufacturing." The MEP program executes this mission through "state and regional centers [that] facilitate and accelerate the transfer of manufacturing technology in partnership with industry, universities and educational institutions, state governments, and NIST and other federal research laboratories and agencies."3 Funding for the MEP centers is provided on a cost-shared basis between the federal government and nonfederal sources, including state and local governments, and fees charged to SMMs for center services.4

The MEP program received $140.0 million for FY2018, $10.0 million (7.7%) more than in FY2016 and FY2017. In his FY2019FY2019, equal to its FY2018 funding level. In his FY2020 budget, President Trump has requested no funding for MEP centers. In contrast, both the House and Senate committee-reported appropriations bills (H.R. 5952 and S. 3072, respectivelyFor FY2020, the House-passed bill (H.R. 3055) would provide $140154.0 million for MEP in FY2019.

The MEP has a staff of 50 employees; the Senate has not yet acted.

The MEP employed approximately 51 full time equivalent federal staff at NIST in FY2018, and the centers have just over 1,300 field staff with technical and business expertise.5 MEP recentlyIn FY2017, MEP completed a system-wide competition that awarded one center to each state and Puerto Rico; previously some states hadhad more than one MEP center.

NIST served more than 26,313 SMMs in FY2017

For FY2018, NIST reported 27,707 interactions with 8,410 unique clients.6 In a survey performed by an independent third-party for NIST MEP covering FY2018, the companies served by MEP Centers reported $12.615.9 billion in new and retained sales (up 26.2% over FY2017), $1.7 billion in cost savings and investment savings, $3.5 (approximately the same as in FY2017), $4.0 billion in new client investment (up 14.3%), and , and the creation and retention of more than 100121,000 jobs in FY2017(up 20.5%).7

Background

In the mid-1980s, congressional debates on trade focused attention on the critical role of technological advance in the competitiveness of individual firms and long-term national economic growth and productivity. Reflecting these ideas, the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act (P.L. 100-418) established a public-private program, now known as the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership, to assist U.S.-based SMMs in identifying and adopting new technologies. The focus on SMMs derived from policymakers' perceptions of their contribution to job creation, innovation, and manufacturing. Research at that time indicated that SMMs produce 2.5 times more innovations per employee than large firms.8 Program advocates noted the efforts of other nations to provide technical and business assistance to their manufacturing communities through the establishment of manufacturing extension centers (see text box, "MEP-Like Programs of Other Countries").

|

MEP-Like Programs of Other Countries Several other countries also have national networks of centers that provide technical and business support to small and medium-sized manufacturers. For example:

Like the MEP, the Fraunhofer Institutes and at least some of the Kohsetsushi centers charge clients fees for their services; IRAP does not charge clients.

|

Research at that time indicated that SMMs produce 2.5 times more innovations per employee than large firms.8 Program advocates noted the efforts of other nations to provide technical and business assistance to their manufacturing communities through the establishment of manufacturing extension centers (see text box, "MEP-Like Programs of Other Countries").In 2015, there were 248246,000 SMMs in the United States (500 or fewer employees). These firms accounted for 98.5% of the nation's manufacturing enterprises and employed approximately 5.21 million people in 2015, approximately 44.4% of total U.S. manufacturing employment.9

The improved use of technology by SMMs is seen by policymakers and business analysts as important to the competitiveness of American manufacturing firms. How a product is designed and produced often determines costs, quality, and reliability. Lack of attention to process technologies and techniques may be the result of various factors, including company finances, insufficient information, equipment shortages, and undervaluation of the benefits of technology. A key purpose of the MEP program is to address these issues through outreach and the application of expertise, technologies, and knowledge.

NIST requires regular reporting by the centers, including the number and types of projects completed. According to NIST, from MEP's inception through FY2017FY2018, the program has worked with 94,033102,443 manufacturers, leading to $111127.3 billion in sales and $18.820.5 billion in cost savings, and has helped create more than 985,317and retain more than 1.1 million jobs.10

According to NIST MEP, for every dollar of federal investment in FY2018, the MEP generatesgenerated nearly $27.3031.00 in new client investment and $27.2029.50 in new sales growth for SMMs. NIST also asserts that MEP creates or retains one manufacturing job for every $1,291065 in federal investment.11

A 20182019 study performed by the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research using a constrained model (which assumes competition or displacement between firms), estimated that the services and activities of the MEP center added more than 219nearly 237,000 jobs to the U.S. economy and $22.024.9 billion to GDP, producing a return of investment of 14.4:1, based on survey 14.5:1 to the U.S. Treasury, based on data provided by MEP clients.12

Evolution of the Program

The MEP program was originally established in 1988 as the "Regional Centers for the Transfer of Manufacturing Technology."13 Over time, the program was referred to by a number of different names, including the Manufacturing Technology Centers program and the Manufacturing Extension Partnership program. The America COMPETES Reauthorization of 2010 codified the name of the program as the "Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership" and the centers as the "Hollings Manufacturing Extension Centers."14

From its inception through the mid-1990s, the MEP's principal emphasis was on

establishing the national network—making sure there was a center within reach of all the nation's manufacturers and linking those centers to one another so they could learn from and teach each other about how best to work with manufacturers.15

The first three centers were established in 1989. Four more were added in 1991 and 1992. In 1994, the number of MEP centers expanded substantially when NIST took over support of extension centers originally funded by the Department of Defense's Technology Reinvestment Project. This brought the number of centers to 44. NIST awarded additional centers in 1995-1996, increasing the total to 70 centers.16 Subsequent consolidation of centers in New York and Ohio brought the number of centers down to 60, including centers in each state and Puerto Rico.

While the focus on helping SMMs has remained constant, the methods and tools used by MEP have evolved since its creation. An intent of the legislation that created the manufacturing extension effort was to provide cutting-edge technology developed by NIST and other federal laboratories to SMMs. Royalties and licensing fees paid to the centers by the SMMs for the use of these technologies were expected to make the centers self-sufficient after the initial six years of operation. Advanced, federally funded technology, however, did not prove to be what most SMMs needed. Rather, their needs proved to be much more basic, including off-the-shelf technologies and business advice on topics such as management information technology, financial management systems, and business processes. A 1991 assessment of the program by the General Accounting Office (GAO, now the Government Accountability Office) concluded that

While legislation establishing the Manufacturing Technology Centers Program emphasized the transfer of advanced technologies being developed at federal laboratories, the centers have found that their clients primarily need proven technologies. Thus, a key mandate of this program is not realistically aligned with the basic needs of most small manufacturers [emphasis added]... [A]ccording to officials from professional and trade associations representing small manufacturers and the results of key studies on U.S. manufacturing competitiveness, such advanced, laboratory-based technologies are not practical for most small manufacturers because these technologies generally are expensive, untested, and too complex.17

In recognition of this situation, the program was reoriented to offer more basic technologies that helped SMMs to improve their productivity and competitive position. By the mid-1990s, MEP was providing "a wide range of business services, including helping companies (1) solve individual manufacturing problems, (2) obtain training for their workers, (3) create marketing plans, and (4) upgrade their equipment and computers."18 As articulated in the NIST Manufacturing Innovation blog,

The initial services were focused on solving immediate and short-term problems—point solutions. The philosophy was an engineering one: 'You have a problem. We can fix it.'19

Over time, the MEP's focus moved from point solutions to more strategic, integrated services. In 2010, the "overarching strategy" for the MEP program was to reduce manufacturing costs through "lean, quality, and other programs targeting plant efficiencies" and to increase profitability "through business growth services resulting in new sales, new markets, and new products."20

Current MEP efforts focus on innovation strategies, commercialization, lean production, process improvements, workforce training, supply chain optimization, and exporting. One of the key areas of the MEP strategy is technology acceleration.21 MEP defines technology acceleration as

integrating technology into the products, processes, services and business models of manufacturers to solve manufacturing problems or pursue opportunities and facilitate competitiveness and enhance manufacturing growth. Technology acceleration spans the innovation continuum and can include aspects of technology transfer, technology transition, technology diffusion, technology deployment and manufacturing implementation.22

Technology acceleration encompasses MEP efforts to assist SMMs in the improvement of existing products, the development of new products, and the development and improvement of manufacturing processes. MEP assists SMMs in this regard through a variety of approaches including technology scouting and transfer; supplier scouting; business-to-business network pilots; lean product development; technology-driven market intelligence; access to capital; cooperative research and development activities with NIST laboratories; and use of other federal programs such as the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program,23 the Advanced Manufacturing Technology (AmTech) Consortia program, and the National Network for Manufacturing Innovation (NNMI, also known as Manufacturing USA).24

While continuing to offer its services to all SMMs, MEP is emphasizing targeted outreach toward growth-oriented SMMs and small entrepreneurial startups.25

Statutory Mission and Activities

The statutory objective of the MEP centers is to enhance productivity and technological performance in U.S. manufacturing through the following:

- the transfer of manufacturing technology and techniques developed at NIST to centers and, through them, to manufacturing companies throughout the United States;

- the participation of individuals from industry, universities, state governments, other federal agencies, and, when appropriate, NIST in cooperative technology transfer activities;

- efforts to make new manufacturing technology and processes usable by U.S.-based small- and medium-sized companies;

- the active dissemination of scientific, engineering, technical, and management information about manufacturing to industrial firms, including small- and medium-sized manufacturing companies;

- the utilization, when appropriate, of the expertise and capability that exists in federal agencies and federally sponsored laboratories;

- the provision to community colleges and area career and technical education schools of information about the job skills needed in manufacturing companies, including small and medium-sized manufacturing businesses in the regions they serve;

- promoting and expanding certification systems offered through industry, associations, and local colleges when appropriate, including efforts such as facilitating training, supporting new or existing apprenticeships, and providing access to information and experts, to address workforce needs and skills gaps in order to assist small- and medium-sized manufacturing businesses; and

- the growth in employment and wages at United States-based small and medium-sized companies.26

No direct financial support is available for companies through the centers. The program offers only technical and managerial assistance, and the cost of that is dependent on thean MEP Centercenter's expenses.27

The statutorily authorized activities of centers include the following:

- the establishment of automated manufacturing systems and other advanced production technologies, based on NIST-supported research, for the purpose of demonstrations and technology transfer;

- the active transfer and dissemination of research findings and center expertise to a wide range of companies and enterprises, particularly small and medium-sized manufacturers; and

- the facilitation of collaborations and partnerships between small and medium-sized manufacturing companies, community colleges, and area career and technical education schools, to help those entities better understand the specific needs of manufacturers and to help manufacturers better understand the skill sets that students learn in the programs offered by such colleges and schools.28

MEP Organization and Structure

The MEP program includes an MEP program office located at NIST (NIST MEP), an MEP Advisory Board, and the 51 MEP centers and their Oversight Boards. In FY2017FY2019, NIST MEP had 47 employees and received appropriations to support 80 FTE.29 The NIST FY2018FY2020 budget justification, which seeks to end federal support for MEP, requested authorization for zerono FTE for MEP.30

NIST MEP

According to NIST, the MEP program office was reorganized in FY2017 "to streamline its activities for better efficiency and to allow for better cross communication and collaboration as well as to align with the NIST structure."31

The NIST MEP program office is led by a Director and a Deputy Director, and has four Divisions with Groups and/or Teams:

- Financial Management and Center Operations Division is responsible for providing all financial oversight for federal funding awarded to support the MEP mission.

- Center Operations and Financial Management Group is responsible for center financial compliance; providing cooperative agreement and operational assistance and guidance to MEP centers; and supporting the MEP system of centers in partnership with NIST MEP's Regional Managers for Strategic Transitions and NIST Grants Management Division.

- Finance/Budget Team is responsible for overall MEP budget and finance operations, contracts, travel, and similar functions.

- Extension Services Division is responsible for developing and maintaining partnerships and creating and launching programs to improve the services offered by MEP centers.

- Three teams—Team Applied Development, Team Partnerships, and Team System Development—work together to help identify and develop new opportunities with and for centers to help their clients, and help identify, develop, and maintain partnerships of national significance.

- External Affairs, Performance, and Support Division is responsible for providing internal and external stakeholder relations and customer service.

- Marketing and Communications Group provides messaging and outreach efforts, publicly positions the MEP program as a resource for manufacturers, works with the local MEP centers on branding and marketing efforts, and coordinates the efforts of the MEP Advisory Board.

- Manufacturing Research and Program Evaluation Group conducts evaluations for the MEP center system, conducts economic research and studies, is responsible for the statutory peer panel review process, and facilitates the collection and reporting of MEP performance data.

- Administrative Team provides overall management of administrative functions and assistance to support the MEP Director and staff.

- IT Team provides information technology support and security, and property management necessary for effective and efficient operations.

- System Learning and Management Division is responsible for assisting MEP centers serving manufacturers by working directly with the 51 MEP centers.

- Regional Management Group regularly interacts with the MEP centers within their portfolio; conducts center reviews; ensures programmatic compliance for the overall health and sustainability of the national network; and works with MEP center, state, local, and other entities as well as with industry leaders to support the development of partnerships focused on local manufacturing ecosystems.

- System Learning Team is reconstituting a learning organization for the national network to facilitate information sharing via a manufacturing knowledgebase system.32

A Director and Deputy Director lead the NIST MEP program office. The office is composed of five divisions (see Figure 1), some with one or more groups. Here are the some of the activities and areas of responsibility for each: - The Director's Office works to provide a strong nationwide network of Manufacturing Extension Partnership centers and supports partnerships across the federal government and within industry that respond to the needs of state- and local-based extension services and supports their integration as a nationwide delivery system to strengthen the global competitiveness of small and medium-sized U.S. manufacturers.

- The External Affairs Performance and Support Division is responsible for executing the mission and vision of the organization for short-term and long-term strategic planning, communication, and program performance.

- The Marketing and Communications Group is responsible for promoting awareness of the MEP National Network to small and medium-sized manufacturers as well as external and internal MEP stakeholders; is responsible for all meetings and summits; and handles communications and programmatic planning related to the MEP National Advisory Board.

- The Program Evaluation and Economic Research Group carries out performance evaluations of the MEP centers and the overall network; monitors performance progress; manages center data reporting and client survey processes; and coordinates among the centers and NIST MEP on reporting, performance, and evaluation policy and issues.

- The Finance Management and Center Operations Division prepares annual budgets and operating outcome plans; tracks program expenditures against multiple fiscal year plans; and manages all aspects of budget and finance.

- The Center Operations Group conducts oversight of all MEP cooperative agreements; executes division business plans related to cooperative agreements; coordinates efforts among MEP and grants and procurement offices; monitors centers regarding all financial and compliance aspects; and takes corrective action with respect to centers that are inefficiently or ineffectively providing services to manufacturing firms.

- The Regional and State Partnerships Division engages in partnership development with internal (i.e., NIST and other Department of Commerce offices and agencies) and external organizations to identify, develop, and assign resources; establishes and maintains strategic alliances with state and local government agencies and legislatures, other federal agencies, and manufacturing-related research organizations; and develops strategic alliances and partnerships with original equipment manufacturers and trade associations. The division also coaches and mentors new centers' directors.

- The Extension Services Division provides guidance and leadership to the MEP National Network regarding the extension services offered by MEP centers; identifies and develops new focus areas, approaches, tools, and techniques for transforming SMMs into high performing enterprises; and establishes and maintains national-level, strategic manufacturing technology alliances with NIST laboratories, other federal agencies, manufacturing research organizations, industry associations, and professional associations that support U.S. SMMs.

- The Network Learning and Strategic Competitions Division manages communities of practice and working groups; identifies manufacturing trends related to SME needs and barriers to adoption; is responsible for the competition processes used for MEP cooperative agreements; and conducts industry analyses and analyzes emerging markets and supply chain technologies to identify products and services to help SMMs be competitive in the global market.31

Figure 1. MEP Organizational Chart

Source: CRS, based on information provided by NIST on September 4, 2019. Structure as of August 2019.

MEP Advisory Board

Source: CRS, based on information provided by NIST on September 4, 2019. Structure as of August 2019.

Congress established an MEP Advisory Board to provide the NIST Director with advice on MEP activities, plans, and policies; assessments of the soundness of MEP plans and strategies; and assessments of current performance against MEP program plans.3332 By statute, the MEP Advisory Board is to consist of at least 10 members broadly representative of stakeholders appointed by the NIST Director. The board is to include at least two members employed by or on an advisory board for a center, at least five members from U.S. small businesses in the manufacturing sector, and at least one member representing a community college. Federal employees may not serve as advisory board members. Members serve staggered terms of three years. A member may serve two consecutive terms. One year from the end of the second term, a member may be reappointed to the board.

The MEP Advisory Board is to act solely in an advisory capacity in accordance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act.3433 The board is required to meet at least twice a year and to report annually to Congress, through the Secretary of Commerce, on the status of the MEP program and programmatic planning. Copies of the MEP Advisory Board annual reports are available online at https://www.nist.gov/mep/about-mep/advisory-board/annual-advisory-board-reports.

MEP Centers

The MEP program is administered by NIST through partnerships with 51 centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, including approximately 400 service locations3534 and more than 1,300 field staff with technical and business expertise.3635 MEP seeks to have a center or other service location not more than two hours away from any potential client. AAppendix A provides a complete list of current MEP centers is provided in Appendix A.

Each center is operated by a state government, university, or other nonprofit organization. Center staff are employees of the center and its partners, not the federal government.

Center Selection

The following sections provide an overview of the criteria used by NIST MEP in awarding centers and the ongoing system-wide center competitionduring the center recompetitions.

Criteria

MEP centers arewere selected in response to open and competitive solicitations issued by NIST. Federal statute requires that center selections be based on merit using, at a minimum, the following criteria:

- the merits of the application, particularly those portions of the application regarding technology transfer, training and education, and adaptation of manufacturing technologies to the needs of particular industrial sectors;

- the quality of service to be provided;

- geographical diversity and extent of service area; and

- the percentage of funding and amount of in-kind commitment from other sources.

37

36Following the first MEP center awards in 1989, the number of centers grew to 70, including at least one center in each state and Puerto Rico, and two or more centers in a few states. Later consolidation reduced the number to 60, and under the recompetition to 51 (one in each state and Puerto Rico).

System-Wide Center Recompetition

In 2017, NIST completed a recompetition of all its centers. At the time the recompetition began in 2014, many of the existing centers had not been competed for more than 20 years. According to NIST, the system-wide competition was intended to result insought to align center funding levels more closely reflectingwith the national distribution of manufacturing activity and result in a single center in each state and Puerto Rico. Other objectives included aligning center activities to the NIST MEP strategic plan; aligning center activities with state and local strategies; providing opportunities for new partnering arrangements; and restructuring and reinvigorating local center boards.38

Review Prior to Continued Center Funding

Center awards are made as cooperative agreements with an initial performance period of five years. NIST may extend an award for an additional five years following an overall assessment of the center, including "programmatic, policy, financial, administrative, and responsibility assessments."3938 According to NIST, when an application for a multiyear award is approved, funding is usually provided for only the first year of the project; for subsequent years, recipients are required to submit detailed budgets and budget narratives prior to the award of any continued funding. The amount of funds awarded after the first year is provided on a noncompetitive basis and may be adjusted upward or downward. Center funding after the first year is contingent upon satisfactory performance, continued relevance to the mission and priorities of the program, and the availability of funds. Continuation of an award to extend the period of performance or to increase or decrease funding is at the sole discretion of NIST.40

Center Cost-Share and Term of Eligibility

The following sections provide current and historical information on center cost-sharing and term of eligibility for funding.

Current Status of Cost-Sharing and Term of Eligibility

Funding for the MEP centers is provided on a cost-share basis by the federal government and nonfederal sources. The federal government may provide up to 50% of the funds required to establish and support a center regardless of the year of operation of the center. A center must meet the required nonfederal cost-share to be eligible to receive federal funding.

Institutions eligible to compete for a center include nonprofit institutions, or consortia thereof; institutions of higher education; or states, United States territories, local governments, or tribal governments. There is no limit to the number of years a center may receive federal funding.

As discussed above, the recompetition sought to better align center funding levels with the number of SMMs and the cost of providing services to these firms in each center's service area. In this regard, NIST MEP set federal funding levels for each state center. These amounts are the maximum available for the federal cost-share, and a center must meet the required nonfederal cost-share to be eligible to receive full funding. (Appendix B provides annualfirst-year funding awarded centers in each state in the recompetition, as well as for those centers competed just prior to the recompetition.)

Historical Background on Cost-Sharing and Term of Eligibility

Cost-Sharing

The financial support system created for MEP by Congress in the original legislation was based on matching financing between the federal government and state, local, and/or private nonprofit entities. The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation report to accompany the Technology Competitiveness Act of 1987 (S. 907, 100th Congress) directed that "the percentage of funding offered by particular applicants be considered in deciding which applications be selected."4140 Cost-sharing strengthens the ties between the organizations involved in the cooperative arrangement and as such, the committee stated that "special attention will be given to innovative ways in which Federal laboratories, State agencies, and business and professional groups can work together."4241 The matching provisions were seen as a means to ensure that the centers reflect the actual needs of the manufacturing companies in the area they serve.

The act establishing the Regional Centers for the Transfer of Manufacturing Technology (later the Manufacturing Extension Partnership program) required applicants to provide more than 50% of the capital and annual operating and maintenance costs in years three through six, but did not specify the share to be paid. Instead, the act directed the Secretary of Commerce to determine the maximum cost share and to publish it in the Federal Register.

Prior to enactment of the American Competitiveness and Innovation Act (P.L. 114-329) in January 2017, NIST was authorized to provide no more than 50% of center costs during the first three years of an award, no more than 40% in the fourth year, and no more than one-third in year five and beyond.43

Following the economic downturn of 2007-2009, there were calls for Congress to raise the federal cost-share to 50% from one-third for centers in their fourth or subsequent year of operation. At that time, some commentators argued that during the difficult economic situation, state and local financial support for the program may be curtailed. At the same time, client fees for service decreased 13.4% between FY2008 and FY2009, the first significant decline since FY1996.4442 Advocates of increasing the federal share noted that such action would permit continued outreach to small manufacturers without pricing the services out of reach for the very small manufacturers. Opponents of this approach argued that the one-third federal contribution was sufficient and that the successful operation of the program was dependent on the financial participation of state and local government as well as the companies utilizing the centers.

The America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-358) mandated that the GAO explore and report on the cost-share provisions of the MEP program. In response, GAO issued a report on April 4, 2011, that noted the following:

We were unable to provide recommendations on how best to structure the cost-share requirement to provide for the long-term sustainability of the program because we could not identify criteria or a basis for determining the optimal cost-share structure for this program. Instead, we have identified a number of factors that could be taken into account in considering modifications to the current cost-share structure. Among other things, past GAO work has found that cost-share structures should promote equity by assigning costs to those who both use and benefit from the services. As it applies to the MEP program, manufacturers, state and local governments, and the nation may all benefit from the program to varying degrees, requiring an evaluation of the relative benefits and aligning cost-shares to reflect who receives the benefits.45

In this regard, GAO noted that NIST's study of the cost-share provision of the MEP program

recommended that the cost-share requirements should be consistent with those of other economic development programs—which it noted, in Commerce, had 1:1 or lower cost-sharing—and should provide flexibility to alter the cost-share requirement in response to economic conditions.46

However, GAO also noted that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) had identified the MEP program for potential elimination from discretionary spending, stating that the program's enhancement of U.S. productivity is questionable. According to CBO, the legislative agency "regularly issues a compendium of budget options to help inform federal lawmakers about the implications of possible policy choices."4745 Elimination of MEP was one more than 100 options CBO proposed in 2011 for changes to federal spending and revenues.

In 2014, two bills were introduced with provisions that would have allowed federal support for MEP centers of up to 50% of annual costs incurred, without regard to how long the cooperative agreement has been in effect.4846 The NIST Reauthorization Act of 2014 (H.R. 5035, 113th Congress) passed the House but did not advance in the Senate. The America COMPETES Reauthorization Act of 2014 (S. 2757, 113th Congress) was introduced in the Senate but did not advance out of committee.

Also in 2014, the MEP Advisory Board recommended that MEP readjust the cost-share structure in order to optimize the federal investment and provide for the long-term sustainability of the program. Specifically, the board recommended requiring to a 1:1 match (50% federal cost share) and allowing the nonfederal cost-share to include in-kind contributions of up to one-half of the center's portion of the cost-share.49

In 2015, the Senate Committee on Appropriations expressed concerns about the federal cost-share structure (as it existed prior to the recent system-wide competition) and directed NIST to provide a report to the committee and to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation "detailing quantifiable metrics on total MEP center funding, including a breakdown of the type of contribution source across centers that have transitioned from the 50 percent Federal, 50 percent non-Federal cost-share to a lower cost-share held by the Federal Government."50

In 2017, Congress enacted the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act (P.L. 114-329), which, among other things, allowed the Secretary of Commerce to provide up to 50% of center costs regardless of the year of operation of a center.49

Term of Eligibility for Funding

The legislation that established the MEP program initially prohibited centers from receiving federal financing beyond their sixth year of operation.5150 However, federal support beyond the sixth year later became considered necessary in lieu of increasing service charges paid by SMMs. While analysts considered service charges to the SMMs to be important to the effectiveness of the MEP program,5251 some also expressed concerns that an increase in charges commensurate with making the centers self-supporting might make the services too expensive for many SMMs. This perspective was articulated in a 1998 NIST-sponsored study:

Analysis indicates that to offset lost public revenue centers would need to take on much larger projects at much higher billing rates and focus on repeat business. As a result, many small manufacturers would not be able to afford these services. Given this conclusion, the best way to ensure high-caliber nationwide assistance to smaller manufacturers is to commit to a stable amount of renewable federal funding for those centers which receive successful evaluations.53

The prohibition on funding after the sixth year was temporarily suspended by provisions in the FY1997 and FY1998 appropriations acts,5453 then eliminated by the Technology Administration Act of 1998 (Section 2, P.L. 105-309). Under the provisions of the act, centers were eligible to receive federal funding of up to one-third of center costs after their sixth year of operation, subject to positive, independent evaluations to be conducted at least every two years.

Other MEP-Related Activities

The MEP program has provided additional funding opportunities for a number of activities that support the program's overarching mission. The Competitive Awards Program (CAP), awards to support the embedding of MEP staff in Manufacturing USA institutes (also referred to as the Embedding Program), the MEP-Assisted Technology and Technical Resource (MATTR) program, and workforce credentials project are examples of such activities. The MEP program has provided additional funding opportunities for a number of activities that support the program's overarching mission. Some of these activities were supported solely by NIST, while others were supported by multiple federal agencies. Current activities of this type include business-to-business networks and additional cooperative agreements. A number of other efforts have been completed, including As discussed above, in 2017, the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act (P.L. 114-329) allows the Secretary to provide up to 50% of center funding, regardless of its year of operation.

Other MEP-Related Activities

Business-to-Business Networks

In December 2014, NIST MEP awarded $2.5 million to 10 MEP centers for the establishment of pilot projects to develop, deploy, and maintain business-to-business (B2B) networks.55 These networks were intended to help match buyers and sellers of technologies or products and services in support of SMMs. The two-year projects were designed to be scalable and interoperable to help determine whether they could be expanded into a national network or a series of regional ones.56

Competitive Awards Program

NIST has used a rolling Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) to solicit funding applications for cooperative awards of $50,000 to $1.0 million each.58 Only NIST-funded MEP centers with specified performance ratings are eligible to apply. Centers can apply individually or in partnership with other centers and collaborating entities such as local economic development organizations, universities, community colleges, and other organizations.59 Proposals are to be evaluated on the basis of their likelihood of achieving one or more of the following objectives:According to NIST, additional work on the B2B networks will be conducted under MEP's Competitive Awards Program, which was established in 2017 by the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act.57 The statutory purpose of the program is "development of projects to solve new or emerging manufacturing problems." Awards are to be made on a peer-reviewed and competitive basis for a period of up to three years; no matching funds are required. Proposals are to be evaluated based on likelihood to improve the competitiveness of industries in the region in which the center or centers are located; create jobs or train newly hired employees; promoteThese activities, current and completed, are discussed below.

Current MEP-Related Activities

Competitive Awards Program

In 2017, Congress established the CAP program for "the development of projects to solve new or emerging manufacturing problems."54 Awards are to be made on a peer-reviewed and competitive basis55 and may span a period of up to three years.56 No matching funds are required under CAP.57

and recruit

recruiting a diverse manufacturing workforce, including through outreach to underrepresented populations. In addition, the statute encourages the ;

58

Additional Cooperative Agreements Awarded Competitively

Embedding MEP Center Staff in Manufacturing USA Institutes

Further, the statute provides for the NIST director to "identify [one] or more themes for a competition carried out under this section, which may vary from year to year, as the Director considers appropriate after assessing the needs of manufacturers and the success of previous competitions." Themes identified by the NIST director—developed in consultation with the MEP Advisory Board and other federal agencies, and specified in the NOFO—are new manufacturing technologies of relevance to small and mid-size manufacturers, particularly those related to Industry/Manufacturing 4.0;63 supply chain management technologies and practices; and workforce intermediary and business services.64 Service area thrusts for CAP awards under these themes include Food Industry Services/Food Manufacturing, Toyota Kata, and Cybersecurity for Manufacturing. In September 2017, NIST announced seven CAP awards to add capabilities to the MEP national network. In September 2018, NIST announced CAP awards of $7 million to eight centers to add capabilities to the MEP national network. In 2016 and 2017, NIST made 14 awards of approximately $1.2 million each in three rounds of competitions to establish partnerships between MEP and the 14 operating Manufacturing USA institutes (also known as the National Network for Manufacturing Innovation or NNMI).66 The awards required no cost-share and had a two-year period of performance; most projects were granted no-cost extensions by NIST to continue working up to an additional year. This effort is sometimes referred to as the Embedding Project. Some projects have ended; others will operate into 2020.67NIST made 14 two-year awards of approximately $1.2 million in three rounds of competitions to place MEP staff in Manufacturing USA (also known as the National Network for Manufacturing Innovation or NNMI) institutes.59 The purpose of these awards, according to NIST, is to further transition of technologies developed at the NNMI institutes to small and medium-size manufacturers.60 Specifically, embedded staff will62

Embedding of MEP Staff in Manufacturing USA Institutes

develop innovate approaches for transferring technology from the Manufacturing USA institutes to small U.S. manufacturers; create approaches for engaging small manufacturers in the work of the institutes through hands-on assistance and services; develop and test business models by which MEP centers and institutes may effectively serve the needs of small U.S. manufacturers in the technology areas of the institutes, and facilitate knowledge and best practice sharing; and cultivate an enhanced nationwide network of partnerships among the institutes and MEP centers.61

The awards were made to the following centers:

- California MEP center, to partner with the Clean Energy Smart Manufacturing Innovation Institute.

- California MEP center, to partner with NextFlex, the Flexible Hybrid Electronics Manufacturing Innovation Institute.

- Delaware MEP center, to partner with the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL).

- Illinois MEP center, to partner with the Digital Manufacturing and Design Innovation Institute (DMDII).

- Massachusetts MEP center, to partner with the Advanced Functional Fabrics of America (AFFOA) Institute.

- Massachusetts MEP center, to partner with the Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute (ARMI).

- Michigan MEP center, to partner with Lightweight Innovations for Tomorrow (LIFT).

- New York MEP center, to partner with the Reducing Embodied-energy and Decreasing Emissions (REMADE) Institute.

- New York MEP center, to partner with the American Institute for Manufacturing Integrated Photonics (AIM Photonics).

- North Carolina MEP center, to partner with Power America.

- Oregon MEP center, to partner with the Rapid Advancement in Process Intensification Deployment (RAPID) Institute.

- Pennsylvania MEP center, to partner with America Makes, the National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute.

- Pennsylvania MEP center, to partner with the Advanced Robotics Manufacturing (ARM) Institute.

- Tennessee MEP center, to partner with the Institute for Advanced Composites Manufacturing Innovation (IACMI).

62

Other Competitive Awards

In September 2017, NIST announced seven awards to add capabilities to the MEP national network.

- Georgia MEP Center. Two awards were made to the Georgia MEP center:

- NIST made a three-year award of approximately $346,000 to the Georgia MEP center, working in collaboration with seven MEP centers, for a project to understand and develop support services for the Georgia machine shop industry to create new markets and implement new technology.

- NIST made a seven-month award of $35,000 to the Georgia MEP center, working in collaboration with seven MEP centers, to support a Department of Transportation-NIST Inter-Agency Agreement to promote and support execution of the Supplier Connectivity Forum in Atlanta to increase business connections and expand U.S. suppliers in the supply chain.

- New Jersey MEP Center. NIST made a two-year award of approximately $974,000 to the New Jersey MEP, working in collaboration with 10 MEP centers, to establish a program that will support Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) capacity building in MEP centers, and offer FSMA readiness assessments, implementation road maps, access to expert FSMA practitioners, and product launch supports.

- Virginia MEP Center. NIST made a two-year award of $1.0 million to the Virginia MEP center, working in collaboration with six MEP centers, to support a project to use the MEP national network to address a set of critical supply chain needs and improve the global competitiveness of small and medium-sized medical device and medical instrument and supply manufacturers nationwide.

- Nevada MEP Center. NIST made a two-year award of $1.0 million to the Nevada MEP center, working in collaboration with eight MEP centers, to promote MEP center staff as "trusted advisors" able to support SMMs to become globally competitive, with growth services, supply chain development, energy savings, strategic planning, and other initiatives.

- North Carolina MEP Center. NIST made a three-year award of approximately $1.0 million to the North Carolina MEP center, working in collaboration with two MEP centers, to support a project to address the needs of small, rural manufacturers seeking to innovate and expand but struggling to address the demands of modern digital supply chains.

- Michigan MEP Center. NIST made a one-year award of approximately $785,000 to the Michigan MEP center, working in collaboration with five MEP centers, to develop a Network Cybersecurity Program that seeks to save companies and jobs while upgrading the value of suppliers to their customers and the skills of their workforce.63

70According to NIST, initial survey responses from MEP centers indicate "significant new and retained revenue, operational cost savings, and new client investments."71

MEP-Assisted Technology and Technical Resource (MATTR) Program

The NIST MATTR program provides MEP SMM clients access to the laboratory's core scientific and engineering capabilities, in advanced manufacturing technology, collaborative robotics, additive manufacturing, materials design and characterization, nanotechnology, information and communications technology, quantum information, biosciences, industrial standards, cybersecurity, and other fields.

The MATTR program provides a mechanism for manufacturers with specific needs or questions concerning products or processes to be connected through the MEP centers to the technical expertise, laboratory facilities, and other resources of the NIST laboratories. It also allows NIST lab staff to inquire of the MEP National Network if there are needs in the manufacturing arena that NIST should address.72

NIST offers many kinds of technical assistance through the MATTR program at no cost. However, NIST may charge fees for certain services such as instrument calibrations and special measurements. NIST has rendered technical assistance to SMMs under MATTR on a number of issues, including nanotechnology and thin film measurement technology. NIST is also using MATTR to increase awareness among SMMs of the NIST library of patents and products available for licensing.73

Value and Utility of Skill Credentials to Manufacturers and Workers

The manufacturing workforce is a significant concern for SMMs, including the number of workers available with the knowledge and skills required for unfilled jobs. Some assert a mismatch between open positions in manufacturing firms and the skills of potential employees. One mechanism for addressing this mismatch is the use of skills credentials. In coordination with the NIST Standards Coordination Office (SCO), MEP awarded a competitive contract to Workcred, an affiliate of the American National Standards Institute, to examine the quality, market value, and effectiveness of manufacturing credentials, and the need for new or improved manufacturing credentials.74

In April 2018, Workcred published the results of its study in the report, Examining the Quality, Market Value, and Effectiveness of Manufacturing Credentials in the United States.75 According to NIST, 945 manufacturers participated in the study's surveys and in-depth focus groups. The report cites the following key findings:

- credentials have uneven use in the manufacturing industry and are not routinely required or used as a major factor in hiring or promotion decisions;

- many manufacturers do not know what credentials are available or how they are relevant to their workplace;

- facility size appears to influence credential use, with large manufacturing facilities more likely to prefer credentials than smaller facilities;

- many manufacturers do not view credentials as the most relevant tools to identify new skilled personnel or as incentives to improve the quality of their existing workforce;

- manufacturers often feel they need to train new employees regardless of whether or not they held a credential, and could not quantify whether credentials added value in terms of reduced cost or reduced training time; and

- manufacturers believe that credentials could serve as a critical resource if they were better understood and made more in line with skills needed in their facilities.76

In addition, the report recommended

- improving understanding about the content, use, and value of credentials;

- expanding the use of quality standards for credentials;

- strengthening relationships between employers, education and training providers, and credentialing organizations;

- adding an employability skills component to existing and new credentials;

- creating credentials that focus on performance and address new roles; and

- increasing the number of apprentices and expanding apprenticeships to more occupations.77

Completed MEP-Related Activities

Business-to-Business Networks

In December 2014, NIST MEP awarded $2.5 million to 10 MEP centers for the establishment of pilot projects to develop, deploy, and maintain business-to-business (B2B) networks.78 These networks were intended to help match buyers and sellers of technologies or products and services in support of SMMs. The two-year projects were designed to be scalable and interoperable to help determine whether they could be expanded into a national network or a series of regional ones.79 The B2B Network projects have been completed.

Make it in America Challenge

In December 2013, NIST MEP awarded grants to 10 winners in nine states as part of the multiagency Make it in America (MiiA) Challenge, an Obama Administration initiative to accelerate job creation and encourage business investment in the United States. Nine awards were to MEP centers. Two were to affiliates of the Ohio MEP center. Each received $125,000 per year for three years.6480 All MiiA projects have been completed.

According to NIST, MiiA was intended to support the efforts of U.S. companies to keep, expand, or reshore manufacturing operations and jobs in the United States, and to encourage foreign companies to build facilities in the United States and make products domestically. The MEP's MiiA Challenge grants were intended to support greater connectivity in regional supply chains and to assist SMMs.

Advanced Manufacturing Jobs and Innovation Accelerator Challenge

NIST MEP centers participated in the Advanced Manufacturing Jobs and Innovation Accelerator Challenge (AMJIAC), a multiagency effort seeking to strengthen U.S. manufacturing.6581 A 2012 solicitation led to 10 three-year awards totaling $20 million. All AMJIAC projects have been completed.

According to NIST:

These grants support the creation and strengthening of regional partnerships capable of accelerating innovation and growing a region's capacity for advanced manufacturing. This funding has been used for activities such as worker training programs or connecting manufacturers to resources like national labs or universities. Ultimately, these grants present regions with an opportunity not only to expand their current activities, but also to fundamentally transform the way that the region supports its manufacturers.66

The role of the MEP center participation varied in the awards. In some cases, an MEP center had the primary management role. In other cases, an MEP center was engaged in a partnership with another organization to lead different project elements. In still other cases, an MEP center was part of a broad-based partnership with different organizations leading one or two project elements.

Manufacturing Technology Acceleration Centers

In July 2013, NIST announced a pilot program under MEP, the Manufacturing Technology Acceleration Centers (M-TACs). M-TACs were designed

to explore different approaches to providing manufacturers with the technology transition and commercialization assistance they need to compete successfully and grow their market share within manufacturing supply chains.67

All M-TAC projects have been completed.

AdditionalOther Grants

In October 2010, NIST announced $9.1 million in cooperative agreements for 22 projects "designed to enhance the productivity, technological performance and global competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers."6884 The funding was provided by MEP on a competitive basis to nonprofit organizations to work with the MEP centers and address one or more of these areas identified by NIST as critical to U.S. manufacturing:

- responding to evolving supply chains;

- accelerating the adoption of new technology to build business growth;

- implementing environmentally sustainable processes;

- establishing and enabling strong workforces for the future; and

- encouraging cultures of continuous improvement.

69

85According to NIST, "The funding will help encourage the creation and adoption of improved technologies and provide resources to develop new products that respond to changing market needs."86 In this regard, the awards differed from other MEP center activities which do not support research activities.

MEP Strategic Plan

In 2017, NIST MEP released its MEP National Network Strategic Plan. Among other things, the plan identified MEP strategic goals and objectives. The four goals of the plan are to

- empower U.S. manufacturers, by assisting them in adopting productivity-enhancing innovative manufacturing technologies, navigating advanced technology solutions, and recruiting and retaining a skilled and diverse workforce;

- champion manufacturing, by promoting the importance of a strong manufacturing base to the U.S. economy and protection of national security interests, creating awareness of innovations in manufacturing, creating enabling workforce development partnerships to build a stronger and diverse pipeline, and maximizing awareness of the MEP national network;

- leverage partnerships, by leveraging national, regional, state, and local partnerships to increase market penetration, identifying mission-complementary advocates to help expand the brand recognition of the MEP national network, and building an expanded service delivery model to support manufacturing technology advances; and

- transform the network, by maximizing the MEP's knowledge and experience to operate as an integrated national network, increasing efficiency and effectiveness by employing a learning organization platform, and by creating a resilient and adaptive MEP national network to support a resilient and adaptive U.S. manufacturing base.

70

87For additional information, including the strategic plan's strategic objectives, measures of success, and priorities, download the report at https://www.nist.gov/document/mepnationalnetworkplan2017to2022finalpdf.

Annual Report to Congress

NIST is required to annually produce and submit to Congress a three-year programmatic planning document, concurrent with the President's annual budget request. This report is to include an assessment of the NIST Director's governance of the MEP program.

The latest version of the plan, NIST Three-Year Programmatic Plan: 2017-2019, includes the following information about the MEP program: NIST's MEP provides technical and business assistance to smaller manufacturers through partnerships between Federal and state governments and non-profit organizations in all 50 states and Puerto Rico. Field agents and programs help manufacturers understand, adopt, and apply new technologies and business practices, increasing productivity, performance, cost savings, reducing waste and creating and retaining manufacturing jobs. MEP also is a strategic advisor to promote business growth and innovation and to connect manufacturers to public and private resources essential for expanding into new markets, developing efficient processes, and training an advanced workforce.88The latest version of the plan, NIST Three-Year Programmatic Plan: 2017-2019, can be accessed at https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/director/planning/3_year_plan_2017-19_web_ready2.pdf.

External Reviews and Recommendations

A number of organizations have reviewed and commented on the program's management and effectiveness, and some have offered recommendations for improving the program. The following sections discuss some of the findings and recommendations of these organizations.71

MEP Advisory Board

The FY2017FY2018 MEP Advisory Board annual report discussed a variety of MEP activities and noted the following, in particular:

- the Advisory Board's direct feedback on the "Presidential Memorandum Streamlining Permitting and Reducing Regulatory Burdens for Domestic Manufacturing,"

- the completion of the transition of the MEP centers from a "loose confederation of independent Centers to a formalized integrated organization known as the MEP National Network,"

- its approval of the 2017-2022 MEP National Network Strategic Plan, and

- the delivery of reports by its MEP Learning Organization subcommittee and the Connecting User Facilities and Labs with SMMs subcommittee.72

the board's activities, including- the board's participation in the Government Accountability Office's (GAO) report on the increase to the maximum level of federal cost-sharing in MEP centers to 50% under the 2017 American Innovation and Competitiveness Act;

- updates on progress to the MEP National Network Strategic Plan for 2017-2022, NIST MEP competitive awards, embedding MEP Center staff at Manufacturing USA Institutes projects, disaster assistance assessments for manufacturers, and the results of the independent study conducted by the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research on the MEP program's economic impacts; and

- progress reports on the board's working groups:

- Performance/Research Development, focused on the issue of performance measurement and management, evaluation, and research to support the MEP National Network;

- Supply Chain Development, focused on development of manufacturing supply chains, with an emphasis on defense suppliers to address Defense industrial base gaps; and

- Advisory Board Executive Committee, focused on future Advisory Board leadership and membership recruitment, cultivation of strong Board governance, and expansion of the Advisory Board's role with local MEP center boards.90

Government Accountability Office

The Government Accountability Office has reviewed aspects of the MEP program on several occasions since the early 1990s. This section provides highlights of those reviews in reverse chronological order.

In March 2019, GAO issued a congressionally mandated report on the implementation of the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act provision that allowed the federal government to provide up to 50% of center funding regardless of the center's year of operation; previously, centers in their fourth year could receive no more than 40%, and those in their fifth and later years could receive no more than one-third. The GAO report stated that MEP centers reported that the change improved their financial stability and helped them to better serve SMMs, especially very small and rural manufacturers. The report noted that the change in cost-sharing occurred concurrently with other factors (notably the recompetition of the centers), making it hard to determine the exact impact of the cost-share change.91

Government Accountability Office

The Government Accountability Office has reviewed aspects of the MEP program on several occasions since the early 1990s.

In an April 2017 report on advanced manufacturing, GAO recommended that the Department of Commerce strengthen its collaboration with the other agencies participating in Manufacturing USA.7392 The Revitalize American Manufacturing and Innovation Act of 2014 (RAMI Act), which established a statutory basis for a Network of Manufacturing Innovation (now branded as "Manufacturing USA"), directed the Secretary of Commerce to ensure that MEP is incorporated in the Manufacturing USA institutes to ensure the research results reach SMMs. NIST has sought to accomplish this by placing MEP staff in the institutes through competitive grants to MEP centers. (See "Embedding MEP Centerof MEP Staff in Manufacturing USA Institutes.")

In a March 2014 report, GAO reported on its investigation into the extent to which the MEP program achieves administrative efficiencies. GAO found that 81.4% of MEP funding supported center awards with the balance devoted to contracts, staff, agency-wide overhead charges, and other items, some of which NIST considered direct support and some of which NIST considered administrative spending. In total, NIST estimated that more than 88.5% of federal MEP program spending in FY2013 was for direct support, and the remainder supported MEP administration.74

In 2010 Congress directed the GAO to report on the cost-share structure of the MEP program and provide recommendations for how best to structure the cost-share requirement to provide for the long-term sustainability of the program.7594 GAO concluded that it was unable to provide such recommendations, as it could not identify criteria or a basis for determining the optimal cost-share structure for this program.7695 However, GAO cited a number of factors that could be taken into account in modifying the existing cost-share structure including promoting equity by assigning costs to those who both use and benefit from the services. In this regard, GAO identified potential beneficiaries as manufacturers, state and local governments, and the nation and recommended an evaluation of the relative benefits and aligning cost-shares to reflect who receives the benefits.7796 (See "Cost-Sharing" for a further discussion of GAO's findings.)

In an August 1995 briefing paper, the GAO explored how small and medium-sized firms were served by various manufacturing extension efforts, including the MEP program.7897 GAO received 551 responses to 766 questionnaires distributed. Approximately 73% of responding firms stated that their relationships with an extension activity had a positive effect on the company's business performance. Fifteen percent indicated that there was no effect at all. Among the impacts identified were improved use of technology (63%), better product quality (61%), and expanded productivity (56%). According to GAO, this suggested that manufacturing extension activities "had some success in achieving their primary goal of helping manufacturers improve their operations through the use of appropriate technologies and through increases in product quality and worker productivity." The study also found that companies which used internal funding to implement recommendations offered by extension programs were the most likely to find an overall positive impact. "Significantly, approximately 97 percent of [these respondents] ... said that they believed that this investment had been worthwhile." Those who utilized these organizations noted that practical experience in the field contributed to the success of staff activities, as did the affordability of the assistance. Companies that did not utilize the resources provided by the MEP tended to be those that were unaware of the program and the opportunities associated with it.

Further refining this information in a March 1996 report, GAO also noted that company size and age were significant factors in business perceptions of the extension program. Smaller (under $1 million gross sales) and newer (established after 1985) firms "were most likely to report that their overall business performance was boosted by MEP assistance."7998 While there were no real differences in perception between extension services offered by NIST and those funded by other institutions, there was a difference in assessments of effectiveness based on whether or not payment was required. According to GAO, those firms that paid fees "were half as likely as those that paid no fees to credit the assistance for having an extremely positive impact, as opposed to a generally positive impact, on their business performance."

Congressional Budget Office

As discussed earlier, the CBO regularly issues a compendium of budget options to help inform federal lawmakers about the implications of possible policy choices. In 2009 and 2011, one of the options CBO proposed was elimination of the MEP program; more recent editions of CBO's Options for Reducing the Deficit have not included the MEP program among its options.

In its 2009 narrative, CBO asserted that proponents of elimination question the appropriateness and necessity of the type of technical assistance offered by MEP, stating that "many university professors of business, science, and engineering consult with private industry, and other ties between universities and business promote knowledge transfer," that many centers in the MEP system existed before the establishment of the MEP program, and that surveys indicated that about half of MEP's clients reported that the same services were available to them through other channels but at a higher price. Supporters of the MEP program, according to CBO, point to the importance of SMMs to the economy in terms of output and employment, and in providing supplies and intermediate goods for large companies. Proponents also argue that many SMMs "face barriers that can prevent them from obtaining the sort of information" that MEP provides.80

CBO also asserted that

The program's enhancement of U.S. productivity also is questionable. It can be argued that federal spending for [MEP] allows some inefficient companies to remain in business, tying up capital, labor, and other resources that could be used more productively elsewhere.81

National Academy of Public Administration

The National Academy of Public Administration also studied the MEP program and in a 2004 report stated that while "on balance ... the MEP Program performs capably and effectively and that the core premise ... remains viable as it is fulfilling its mission by leveraging both public and private resources to assist the nation's small manufacturers," there should be consideration of a "fundamental change in the mix of the types of services it provides as well as the structures for delivering them."82101 As such, a Next Generation Strategic Plan was developed by the MEP in 2006 to concentrate on not just the shop floor but on "the entire enterprise and its position in the marketplace." In addition to individual manufacturing firms, NIST concluded that MEP "must focus on industry/supply chain requirements as well as overall economic development trends."83102 Current MEP efforts include a focus on helping companies to participate in supply chains (e.g., by helping them become compliant with quality standards) and on supply chain optimization.

Appropriations and Related Issues

The following sections provide information on the status of FY2019 appropriations for MEP and a longer This section provides information on FY2019 appropriations for MEP, the status of FY2020 appropriations, and a longer-term perspective on MEP budget requests and appropriations from FY2003-FY2019 to FY2020.

FY2018FY2019 Appropriations Status and FY2019and the FY2020 Request

InAs with his FY2018 and FY2019 budget, President Trump sought to eliminate the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, requesting $6.0 million "for the orderly wind down" of the program. The House committee-reported Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2018 (H.R. 3267) would provide $100.0 million for the MEP program, down $30.0 million (23.1%) from the FY2017 enacted level and up $94.0 million from the request. The Senate committee-reported Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2018 (S. 1662) rejected the Trump Administration's proposed elimination of the MEP program and proposed funding at the FY2017 level of $130.0 million, $30.0 million more than the House committee-reported bill. On March 23, 2018, Congress enacted the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018, providing $140.0 million for MEP.

President Trump has again proposed to eliminate federal funding for the MEP centers in his FY2019 budget. Both the House committee-reported bill, H.R. 5952, and the Senate committee-reported bill, S. 3072, would provide $140.0 million for MEP, the same as the FY2018 levelproposes to eliminate federal support for MEP in the FY2020 budget request. In FY2018 and FY2019, Congress provided $140.0 million for MEP. The House-passed level (H.R. 3055) for MEP for FY2020 is $154.0 million. The Senate has not yet acted.

Table 1. Manufacturing Extension Partnership Program Appropriations, FY2018-FY2019

(budget authority, in millions of dollars)

|

|

|

|

FY2020 Senate |

|

|

|

Manufacturing Extension Partnership program |

$140.0 |

$0.0 |

$ |

$140.0 |

Source: H.R. 5952; S. 3072; Consolidated Appropriations Act, 20182019 (P.L. 115-141); and 116-6); National Institute of Standards and Technology Fiscal Year 2019/National Technical Information Service Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Submission to Congress, February 2018, http://www.osec.doc.gov/bmi/budget/FY19CBJ/NIST_and_NTIS_FY2019_President's_Budget_for_508_comp.pdfMarch 2019, https://www.commerce.gov/sites/default/files/2019-03/fy2020_nist_congressional_budget_justification.pdf, and H.R. 3055.

Appropriations and Requests FY2003-FY2019

FY2020