Honduras: Background and U.S. Relations

Changes from July 30, 2018 to October 24, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Politics and Governance

- Disputed 2017 Election and Aftermath

- Anti-corruption Progress and Setbacks

- Economic and Social Conditions

- Security Conditions

- U.S.-Honduran Relations

- Foreign Assistance

- Conditions on Assistance

- FY2019 Request

- Migration Issues

- Recent Migration Flows

- Deportations and Temporary Protected Status

- Security Cooperation

- Citizen Safety

- Counternarcotics

- Human Rights Concerns

- U.S. Initiatives

- Human Rights Restrictions on Foreign Assistance

- Commercial Ties

- Trade and Investment

- Labor Rights

- Outlook

Figures

Summary

Honduras, a Central American nation of 9 million people, has had close ties with the United States for many years. The country served as a base for U.S. operations designed to counter Soviet influence in Central America during the 1980s, and it continues to host a U.S. military presence and cooperate on antidrug efforts today. Trade and investment linkages are also long-standing and have grown stronger since the implementation of the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) in 2006. In recent years, instability in Honduras—including a 2009 coup and significant outflows of migrants and asylum-seekers since 2014—has led U.S. policymakers to focus greater attention on conditions in the country and their implications for the United States.

Domestic Situation

President Juan Orlando Hernández of the conservative National Party was inaugurated to a second four-year term in January 2018. He lacks legitimacy among many Hondurans, however, due to allegations that the November 2017 presidential election was marred by fraud. During Hernández's first term, Honduras made some progress in reducing violence and putting public finances on a more sustainable path. Anti-corruption efforts also made some headway, largely as a result of cooperation between the Honduran public prosecutor's office and the Organization of American States-backed Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras.

Nevertheless, considerable challenges remain. Honduras continues to be one of the poorest and most unequal countries in Latin America, with nearly 69% of Hondurans living below the poverty line. It also remains one of the most violent countries in the world and continues to suffer from persistent human rights abuses and widespread impunity. Moreover, the country's tentative progress in combating corruption has generated a fierce backlash, calling into question the sustainability of those efforts.

U.S. Policy

U.S. policy in Honduras is guided by the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, which is designed to promote economic prosperity, strengthen governance, and improve security in Honduras and the rest of the region. Congress appropriated an estimated $79.8 million in bilateral assistance for Honduras to advance those objectives in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). The Trump Administration has requested $65.8 million to continue U.S. efforts in Honduras in FY2019. The Senate Appropriations Committee's FY2019 foreign aid appropriations measure (S. 3108) would slightly exceed the request, providing $68.8 million for Honduras. The House Appropriations Committee's foreign aid appropriations bill (H.R. 6385) would not specify a funding level for Honduras.

Members of the 115th Congress have put forward several measures intended to incentivize policy changes in Honduras. P.L. 115-141 withholds 75% of assistance for the Honduran central government until Honduras addresses concerns such as border security, corruption, and human rights abuses. S. 3108 and H.R. 6385 would maintain similar conditions on aid, and the Berta Caceres Human Rights in Honduras Act (H.R. 1299) would suspend all security assistance until Honduras meets strict human rights conditions. A resolution adopted by the House, H.Res. 145, called on the Honduran government to support ongoing anti-corruption efforts, and a provision in the FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5515), as reported out of conference, would requireP.L. 115-232) requires the Secretary of State to name Honduran officials known to have engaged in, or facilitated, acts of grand corruption or narcotics trafficking.

Introduction

Honduras, a Central American nation of 9 million people, faces significant domestic challenges. Democratic institutions are fragile, current economic growth rates are insufficient to reduce widespread poverty, and the country continues to experience some of the highest violent crime rates in the world. These interrelated challenges have produced periodic instability in Honduras and have contributed to relatively high levels of displacement and emigration in recent years. Although the Honduran government has taken some steps intended to address these deep-seated issues, many analysts maintain that Honduras lacks the institutions and resources necessary to do so on its own.

U.S. policymakers have devoted more attention to Honduras and its Central American neighbors since 2014, when an unexpectedly large number of migrants and asylum-seekers from the region arrived at the U.S. border. In the aftermath of the crisis, the Obama Administration determined that it was "in the national security interests of the United States" to work with Central American governments to improve security, strengthen governance, and promote economic prosperity in the region.1 Accordingly, the Obama Administration launched a new, whole-of-government U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and requested significant increases in foreign assistance to support its implementation. Although the Trump Administration has maintained the strategy, it also has sought to scale back—and occasionally threatened to cut off—foreign assistance for Honduras and its neighbors.2 Congress has not accepted the majority of the Trump Administration's proposed cuts thus far. It has appropriated nearly $2.1 billion for Central America since FY2016, including at least $431 million for Honduras (see Table 1).

Many Members of the 115th Congress have been closely tracking the progress of U.S. efforts in Honduras and the rest of the region and likely will continue to shape U.S. policy in Central America as they consider the Trump Administration's FY2019 budget request and other legislationlegislative measures. This report analyzes political, economic, and security conditions in Honduras. It also examines issues in U.S.-Honduran relations that have been of particular interest to many in Congress, including foreign assistance, migration, security cooperation, human rights, and trade and investment.

|

|

Leadership |

President: Juan Orlando Hernández (National Party) President of the Honduran National Congress: Mauricio Oliva (National Party) |

|

Geography |

Area: 112,000 sq. km. (slightly larger than Virginia) |

|

People |

Population: 9 million (2018 est.) Racial/Ethnic Identification: 91.3% Mixed or European descent, 8.6% indigenous or African descent (2013) Religious Identification: 41.3% Evangelical, 38.4% Catholic, 17.8% none, 2.4% other (2018) Literacy Rate: 88.2% (2017) Life Expectancy: 74 (2015 est.) |

|

Economy |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): $23 billion (2017 est.) GDP per Capita: $2,766 (2017 est.) Top Exports: textiles and apparel, coffee, insulated wire, shrimp, palm oil, and bananas (2017) Poverty Rate: 68.8% (2017) Extreme Poverty Rate: 44.2% (2017) |

Sources: Population, ethnicity, literacy, and poverty data from Instituto Nacional de Estadística; religious identification data from Equipo de Reflexión, Investigación y Comunicación, Compañía de Jesús; export data from Global Trade Atlas; GDP estimates from International Monetary Fund; life expectancy estimate from U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Map created by CRS.

Notes: A number of studies have estimated that the indigenous and Afro-Honduran population is much larger than official statistics indicate. A 2007 census conducted by indigenous organizations, for example, found that Hondurans of indigenous and African descent accounted for 20% of the Honduran population.

Politics and Governance

Honduras has struggled with political instability and authoritarian governance for much of its history. The military traditionally has played an influential role in politics, most recently governing Honduras for most of the period between 1963 and 1982. The country's current constitution—its 16th since declaring independence from Spain in 1821—was adopted as Honduras transitioned back to civilian rule. It establishes a representative democracy with a separation of powers among an executive branch led by the president, a legislative branch consisting of a 128-seat unicameral national congress, and a judicial branch headed by the supreme court. In practice, however, the legislative process tends to be executive-driven and the judiciary is often subject to intimidation, corruption, and politicization.3

Honduras's traditional two-party political system, dominated by the Liberal (Partido Liberal, PL) and National (Partido Nacional, PN) Parties, has fractured over the past decade. Both traditional parties are considered to be ideologically center-right,4 and political competition between them generally has been focused more on using the public sector for patronage than on implementing programmatic agendas.5 The leadership of both parties supported a 2009 coup, in which the military, backed by the supreme court and congress, detained then-President Manuel Zelaya and flew him into forced exile. Zelaya had been elected as a moderate member of the PL but alienated many within the political and economic elite by governing in a populist manner and calling for a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution.6 Many rank-and-file members of the PL abandoned the party in the aftermath of the coup and joined Zelaya upon his return from exile to launch a new left-of-center Liberty and Re-foundation (Libertad y Refundación, LIBRE) party.

The post-coup split among traditional supporters of the PL has benefitted the PN, which now has the largest political base in Honduras and has controlled the presidency and congress since 2010. Critics contend that the PN has gradually eroded checks and balances to consolidate its influence over other government institutions and entrench itself in power. For example, in 2012, the PN-controlled congress, led by Juan Orlando Hernández, replaced four supreme court justices who had struck down a pair of high-profile government initiatives. Although the Honduran minister of justice and human rights asserted that the move was illegal and violated the independence of the judiciary, it was never overturned.7 The justices who were installed in 2012 issued a ruling in 2015 that struck down the constitution's explicit ban on presidential reelection, allowing Hernández, who had been elected president in 2013, to seek a second term.8 The PN also has manipulated appointments to other nominally independent institutions such as the public prosecutor's office and the country's electoral oversight body, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo Electoral, TSE).9

Disputed 2017 Election and Aftermath

Honduras held general elections on November 26, 2017. On election night, with 57% of the vote counted, Salvador Nasralla, a television personality, sports commentator, and the presidential candidate of the LIBRE-led "Opposition Alliance Against the Dictatorship,"10 held a five-point lead over President Hernández. Hernández edged ahead of Nasralla on November 30, 2017, however, after the TSE belatedly processed the outstanding votes. The Opposition Alliance and the PL denounced the TSE's delays and lack of transparency and alleged that the results had been manipulated. Although some observers attributed the late swing toward Hernández to slow reporting from the PN's rural strongholds, statistical analyses of differing vote patterns between early- and late-reporting polling stations suggest there may have been fraud.11 The TSE agreed to conduct a partial recount of voting center tallies, which produced few changes, and then certified Hernández as the winner on December 17, 2017. According to the official results, Hernández won 42.95% of the vote, while Nasralla won 41.42% and Luis Zelaya of the PL won 14.74%.12

An electoral observation mission from the Organization of American States (OAS)13 labeled the 2017 presidential election "a low-quality electoral process" and asserted that "the abundance of irregularities and deficiencies is such as to preclude full certainty regarding the outcome."14 Among other problems, the mission observed containers of polling place results that had been unsealed prior to reaching the central tabulation center, ballots that showed no signs of having been handled by voters, and evidence of deliberate human intrusions into the electronic vote tabulation and dissemination system and the intentional elimination of digital traces. Given the extent of the irregularities and the narrow margin of victory, OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro called on Honduras to hold new elections.15

A separate observation mission from the European Union also documented some problems with the election, such as the use of state resources for PN campaign purposes, but it did not question the results.16 The mission noted that the TSE's electronic vote tabulation and dissemination system enables political parties to compare copies of the results given to party representatives at polling places against scanned images that are used to compile the official results published on the TSE's website. It also noted that while the Opposition Alliance and the PL were present at more than 90% of the polling places observed by the mission, the parties did not present a statistically significant number of polling place results that differed from those published by the TSE when challenging the official results.

In the days and weeks following the election, many Hondurans took to the streets to protest against the alleged electoral fraud. They carried out a series of large-scale demonstrations and road blocks, and some individuals engaged in vandalism and looting. President Hernández initially responded to the unrest by issuing a decree on December 1, 2017, that imposed a nightly curfew, suspended certain constitutional rights, and empowered the military to detain those who disobeyed the order to stay off the streets. The "state of emergency," which OAS Secretary General Almagro deemed a "disproportionate" response to the situation, expired on December 9, 2017.17 According to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Honduran security forces used excessive force to disperse protests both during and after the state of emergency, injuring at least 60 individuals and killing at least 16 others.18 Nearly 1,700 Hondurans reportedly were detained for violating the curfew, and local human rights groups assert that fiveLocal human rights groups assert that nearly 1,400 Hondurans were detained in the month following the election, and 13 "political prisoners" remain behind bars as a result of their protest activities.19 The OHCHR also documented numerous cases of Honduran security forces intimidating and harassing journalists, human rights defenders, and political and social activists.20

The United States was among the first countries to accept the legitimacy of the elections. On December 22, 2017, the U.S. State Department issued a statement that congratulated President Hernández on his reelection and asserted that "a significant long-term effort to heal the political divide in the country and enact much-needed electoral reforms should be undertaken."21 Much of the rest of the international community followed the U.S. government's lead and recognized the results before Hernández was inaugurated to his second four-year term on January 27, 2018.

Many Hondurans continue to view Hernández as an illegitimate president. According to a February 2018 poll, 56% of Hondurans think Nasralla won the presidential election, 62% think the elections were marred by fraud, and 78% think the elections weakened democracy in Honduras.22 The United Nations has sought to facilitate a national dialogue to promote societal reconciliation, but LIBRE refused to participate and the PL pulled out of the talks in late September 2018. Both major opposition parties argue that the PN has shown no interest in a genuine dialogue and that any accords reached during the talks would be blocked by the Honduran congress, in which the PN holds 61 of 128 seats, LIBRE holds 30 seats, the PL holds 26 seats, and five small parties that are largely allied with the PN hold 11 but it has yet to get off the ground as the major political parties have been unable to reach an agreement on the substance of the talks and whether the results will be binding. Opposition parties are concerned that any accords reached during the dialogue could be blocked by the Honduran congress in which the PN holds 61 of 128 seats, the Opposition Alliance holds 34 seats, the PL holds 26 seats, and four small parties that are largely allied with the PN hold seven seats.23

Anti-corruption Progress and Setbacks

Corruption is widespread in Honduras, though the country has made some progress since 2016 with the support of the OAS-backed Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Misión de Apoyo Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras, MACCIH). Honduran civil society had carried out a series of mass demonstrations demanding the establishment of an international anti-corruption organization after Honduran authorities discovered that at least $300 million was embezzled from the Honduran social security institute during the PN administration of President Porfirio Lobo (2010-2014) and some of the stolen funds were used to fund Hernández's 2013 election campaign. Hernández was reluctant to create an independent organization with far-reaching authorities like the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, which had helped bring down the Guatemalan president in 2015. Facing significant domestic and international pressure, however, he negotiated a more limited arrangement with the OAS. According to the agreement, signed in January 2016, the MACCIH is intended to support, strengthen, and collaborate with Honduran institutions to prevent, investigate, and punish acts of corruption.24

The MACCIH initially focused on strengthening Honduras's anti-corruption legal framework. It secured congressional approval for new laws to create anti-corruption courts with nationwide jurisdiction and to regulate the financing of political campaigns. The Honduran congress repeatedly delayed and weakened the MACCIH's proposed reforms, however, hindering the mission's anti-corruption efforts. For example, prior to enactment of the law to establish anti-corruption courts with nationwide jurisdiction, the Honduran congress modified the measure by stripping the new judges of the authority to order asset forfeitures, stipulating that the new judges can hear only cases involving three or more people, and removing certain crimes—including the embezzlement of public funds—from the jurisdiction of the new courts.25 Similarly, between the approval of the political financing law and its official publication, the law was changed to delay its entry into force and to remove a prohibition on campaign contributions from companies awarded public contracts.26 Other measures the MACCIH has proposed, such as an "effective collaboration" bill to encourage members of criminal networks to cooperate with officials in exchange for reduced sentences, have yet to be enacted. Such plea-bargaining laws have proven crucial to anti-corruption investigations in other countries, such as the ongoing "Car Wash" (Lava Jato) probe in Brazil.27

MACCIH officials are also working alongside a recently established anti-corruption unit within the public prosecutor's office to jointly investigate and prosecute high-level corruption cases. Cooperation on the Honduran social security institute case has produced at least 12 convictions, including the former director and two former vice directors. The MACCIH is also supporting investigations into alleged embezzlement and money laundering by former First Lady Rosa Elena Bonilla de Lobo (2010-2014), alleged high-level government collusion with the Cachiros drug trafficking organization, and possible corruption involving public contracts awarded for the controversial Agua Zarca hydroelectric project, which Berta Cáceres—a prominent indigenous and environmental activist—was protesting at the time of her murder (for more on these cases, see "Counternarcotics" and "Human Rights Concerns," below).

This tentative progress has generated fierce backlash. In January 2018, for example, the Honduran congress effectively blocked an investigation into legislators' mismanagement of public funds by enacting a law that prevents the public prosecutor's office from pursuing such cases for up to three years while the high court of auditors (Tribunal Superior de Cuentas, TSC) conducts an audit of public accounts. This "impunity pact," combined with other obstruction from the Honduran government and a perceived lack of support from the OAS, led the head of the MACCIH, Juan Jiménez, to resign in February 2018.28 The OAS Secretary General nominated Luiz Antonio Marrey, a Brazilian prosecutor, to succeed Jiménez, but Marrey was not sworn in until early July 2018 due to resistance from the Hernández Administration. In March 2018, lawyers representing members of congress accused of embezzling public funds challenged the constitutionality of the MACCIH's mandate. Although the supreme court ultimately ruled against the challenge, the judgment included provisions that some analysts think could restrict coordination between anti-corruption prosecutors and MACCIH officials.29

Nevertheless, the public prosecutor's office and the MACCIH have continued to push forward. In June 2018, they indicted 38 individuals, including members of congress and other government officials, for abuse of authority, fraud, embezzlement, money laundering, and falsification of public documents. Those involved in the so-called "Pandora" case allegedly funneled $12 million intended for agricultural development projects to PN and PL election campaigns.30

Public prosecutors and the MACCIH have attempted to recover some of the stolen funds by seizing PN and PL assets, including the parties' headquarters.The United States has provided the MACCIH with crucial financial and diplomatic support. The Obama Administration contributed $5.2 million in June 2016 to help the MACCIH get up and running, and Congress appropriated another $5 million for the MACCIH through the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31).31 U.S. officials also have repeatedly urged the Honduran government to cooperate with the MACCIH, which appears to have helped the mission withstand the backlash it has faced over the past year.32

The 115th Congress has taken a number of steps to support anti-corruption efforts in Honduras. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) included $31 million for the MACCIH and public prosecutors in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. It also conditioned the release of 50% of assistance for the Honduran central government on the government's cooperation with the MACCIH and regional human rights entities. The FY2019 foreign aid appropriations bills reported out of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees (H.R. 6385 and S. 3108) would both continue to tie assistance to anti-corruption efforts. The report accompanying the Senate Appropriations Committee's bill, S.Rept. 115-282, would also require the Secretary of State to submit a report on grand corruption in Honduras, including senior officials who are credibly alleged to have committed or facilitated such corruption. The FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 5515), as reported out of conference, includesP.L. 115-232), included a similar provision that would requirerequires the Secretary of State to submit a report that includes the names of senior government officials known to have facilitated acts of grand corruption, elected officials known to have received illicit campaign funds, and individuals known to have facilitated the illicit financing of political campaigns.

Economic and Social Conditions

The Honduran economy is one of the least developed in Latin America. Historically, the country's economic performance was closely tied to the prices of agricultural commodities, such as bananas and coffee. While those traditional agricultural exports remain important, the Honduran economy has diversified since the late 1980s as successive Honduran governments have privatized state-owned enterprises, lowered taxes and tariffs, and offered incentives to attract foreign investment. Those policy changes spurred growth in the maquila (offshore assembly for reexport) sector—particularly in the apparel, garment, and textile industries—and led to the development of nontraditional exports, such as seafood and palm oil.

Honduras has experienced modest economic growth since adopting more open economic policies, but it remains one of the poorest and most unequal countries in Latin America. The Honduran economy has grown by an average of 3.7% annually since 1990, with gross domestic product (GDP) reaching an estimated $23 billion in 2017. Per capita income has grown at a slower rate, however, and remains relatively low at an estimated $2,766.33 Employment is precarious for most Hondurans, with 63% of the economically active population either unemployed or underemployed.34 Consequently, nearly 69% of Hondurans live in poverty and 44% live in extreme poverty.35

President Hernández's top economic policy priority upon taking office in 2014 was to put the government's finances on a more sustainable path. The nonfinancial public sector deficit had grown to 7.5% of GDP in 2013 as a result of weak tax collection, increased expenditures, and losses at state-owned enterprises.36 As the Honduran government struggled to obtain financing for its obligations, public employees and contractors occasionally went unpaid and basic government services were interrupted. In 2014, Hernández negotiated an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), under which the Honduran government agreed to reduce the deficit to 2% of GDP by 2017 and carry out structural reforms related to the electricity and telecommunications sectors, pension funds, public-private partnerships, and tax administration in exchange for access to $189 million in financing.37 The Hernández Administration upheld its commitments to the IMF but has been criticized by some economic analysts for implementing deficit reduction policies—such as indirect tax increases and reductions in public investment—that negatively impact the poorest Hondurans.38

Hernández also has sought to make Honduras more attractive to foreign investment. He contracted a global consulting firm to develop the five-year "Honduras 20/20" plan, which seeks to attract $13 billion of investment and generate 600,000 jobs in four priority sectors: tourism, textiles, intermediate manufacturing, and business services.39 To achieve the plan's objectives, the Honduran government has adopted a new business-friendly tax code, increased investments in infrastructure, and entered into a customs union with Guatemala and El Salvador. The Hernández Administration also is moving forward with a controversial plan to establish "Employment and Economic Development Zones"—specially designated areas where foreign investors are granted administrative autonomy to enact their own laws, set up their own judicial systems, and carry out other duties usually reserved for governments. Supporters maintain that these zones will attract investment that otherwise would be deterred by corruption and instability, but critics assert that the zones would effectively privatize national territory and deprive Honduran communities of their democratic rights.40 Despite the Hernández Administration's efforts, annual foreign direct investment inflows to Honduras fell from $1.4 billion in 2014 to $1.2 billion in 2017.41

The Honduran economy grew by an average of nearly 3.9% during Hernández's first term.42 The Economist Intelligence Unit forecasts that growth will slow to 3.5% in 2018 and 2019 as political tension stemming from the disputed 2017 election takes a toll on consumer and investor confidence3.4% in 2019 due to a decline in consumer and investor confidence in the aftermath of the disputed 2017 election. Honduras's medium-term economic performance is expected to mirror the U.S. business cycle, as the United States remains the countryHonduras's top export market and primary source of investment, tourism, and remittances. To boost the country's long-term growth potential, analysts maintain Honduras will have to address entrenched social ills, such as widespread crime and corruption and high levels of poverty and inequality.43

Security Conditions

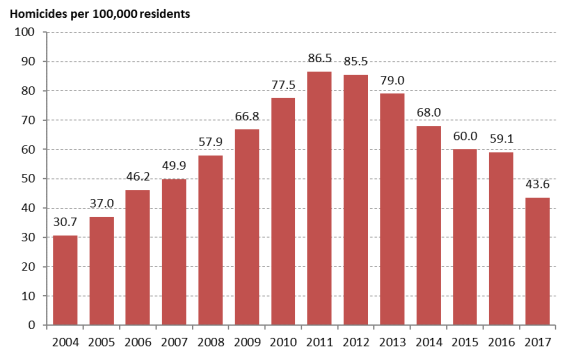

Security conditions in Honduras appear to have improved in recent years but the country continues to be among the most violent in the world. The homicide rate, which peaked at 86.5 murders per 100,000 residents in 2011, fell to 43.6 murders per 100,000 residents in 2017 (see Figure 2, below). Common crime remains widespread, however, with nearly 25% of Hondurans reporting that they or a family member has been the victim of a crime in the past year.44 The pervasive sense of insecurity has displaced many Hondurans and led some to leave the country. According to theThe Honduran government's national commissioner for human rights, documented nearly 1,100900 cases in which Hondurans were forced to abandon their homes in 2016 and 2017 as a result of death threats, extortion, forced gang recruitment, or other forms of criminal intimidation.45 High rates of crime and violence also take an economic toll on Honduras, deterring investment and forcing many small businesses to close.

|

|

Source: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, Instituto Universitario en Democracia, Paz y Seguridad, Observatorio de la Violencia, Boletín Nacional (Enero–Diciembre 2017), No. 48, March 2018. |

A number of interrelated factors have contributed to the poor security situation. Widespread poverty, fragmented families, and a lack of education and employment opportunities leave many Honduran youth susceptible to recruitment by gangs such as the Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18. These organizations engage in drug dealing and extortion, among other criminal activities, and appear to be responsible for a substantial portion of homicides and much of the crime that affects citizens on a day-to-day basis.46

Honduras also serves as a significant drug-trafficking corridor as a result of its location between cocaine-producing countries in South America and the major consumer market in the United States. Heavily armed and well-financed transnational criminal organizations have sought to secure control of Honduran territory by battling one another and local affiliates and seeking to intimidate and infiltrate Honduran institutions. Many of these groups have close ties to political and economic elites who rely upon illicit finances to fund their election campaigns and maintain or increase the market share of their businesses.47 Honduran security forces and justice-sector institutions historically have lacked the personnel, equipment, and training necessary to respond to these threats and have struggled with systemic corruption.

President Hernández campaigned on a hard-line security platform, repeatedly pledging to do whatever it takes to reduce crime and violence in Honduras. Upon taking office in 2014, he immediately ordered the military and the police into the streets to conduct intensive patrols of high-crime neighborhoods. Among the units involved in the ongoing operation are two hybrid forces that Hernández helped to establish while he was serving as the president of the Honduran congress: the military police force (Policía Militar de Orden Público, PMOP), which is under the control of the ministry of defense, and a military-trained police unit under the control of the Honduran national police known as the TIGRES (Tropa de Inteligencia y Grupos de Respuesta Especial de Seguridad). An interagency task force known as FUSINA (Fuerza de Seguridad Interinstitucional) is charged with coordinating the efforts of the various military and police forces, intelligence agencies, public prosecutors, and judges.

Hernández also has taken some steps to strengthen security and justice-sector institutions. He created a special commission on police reform commission in April 2016 after press reports indicated that high-ranking police commanders had colluded with drug traffickers to assassinate two top Honduran antidrug officials in 2009 and 2011 and the head of the anti-money laundering unit of the public prosecutor's office in 2013; other officials in the Honduran national police and security ministry reportedly covered up internal investigations of the crimes.48 Although previous attempts to reform the police force produced few results, the special commission has dismissed more than 4,4005,200 officers, including nearly half of the highest-ranking members.49 It also proposed and won congressional approval for measures to restructure the national police force, increase police salaries, and implement new training and evaluation protocols.49 Public perceptions of the national police have yet to improve substantially,50 however, and high-level officials—including the current chief of police—continue to face allegations of corruption and criminal activity.51

Honduras's investigative and prosecutorial capacity has improved in recent years, although impunity remains widespread. In 2015, the Honduran national police launched a new investigative division and the public prosecutor's office established a new criminal investigative agency. Both institutions have set up forensic laboratories and have begun to conduct more scientific investigations. The budget of the public prosecutor's office grew by nearly 70% in nominal terms between 2014 and 2017, allowing Attorney General Óscar Chinchilla to hire additional detectives, prosecutors, and other specialized personnel.52 Nevertheless, the public prosecutor's office accounted for less than 1.3% of the Honduran central government's expenditures in 2017 and remains understaffed and underfundedoverburdened.53

U.S.-Honduran Relations

The United States has had close relations with Honduras over many years. The bilateral relationship was especially close in the 1980s, when Honduras returned to civilian rule and became the lynchpin for U.S. policy in Central America. The country served as a staging area for U.S.-supported raids into Nicaragua by the Contra forces attempting to overthrow the leftist Sandinista government and an outpost for U.S. military forces supporting the Salvadoran government's efforts to combat the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front insurgency. A U.S. military presence known as Joint Task Force Bravo has been stationed in Honduras since 1983. Economic linkages also intensified in the 1980s after Honduras became a beneficiary of the Caribbean Basin Initiative, which allowed for duty-free importation of Honduran goods into the United States. Economic ties have deepened since the entrance into force of the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) in 2006.

Relations between the United States and Honduras were strained during the country's 2009 political crisis.54 The Obama Administration condemned the coup and, over the course of the following months, leveled a series of diplomatic and economic sanctions designed to pressure Honduran officials to restore Zelaya to power. The Administration limited contact with the Honduran government, suspended some foreign assistance, minimized cooperation with the Honduran military, and revoked the visas of members and supporters of the interim government headed by Roberto Micheletti. In November 2009, the Administration shifted the emphasis of U.S. policy from reversing Zelaya's removal to ensuring the legitimacy of previously scheduled elections. Although some analysts argued that the policy shift allowed those behind the coup to consolidate their hold on power, Administration officials maintained that elections had become the only realistic way to bring an end to the political crisis.55

Current U.S. policy in Honduras is focused on strengthening democratic governance, including the promotion of human rights and the rule of law, enhancing economic prosperity, and improving the long-term security situation in the country, thereby mitigating potential challenges for the United States such as irregular migration and organized crime.56 To advance these objectives, the United States provides Honduras with substantial foreign assistance, maintains significant security and commercial ties, and engages on issues such as migration and human rights.

Foreign Assistance

The U.S. government has provided significant amounts of foreign assistance to Honduras over the years as a result of the country's long-standing development challenges and close relations with the United States. Aid levels were particularly high during the 1980s and early 1990s, as Honduras served as a base for U.S. operations in Central America. U.S. assistance to Honduras began to wane as the regional conflicts subsided, however, and generally has remained at lower levels since then, with a few exceptions, such as a spike following Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and again after the Millennium Challenge Corporation awarded Honduras a $215 million economic growth compact in 2005.57

Current assistance to Honduras is guided by the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, which is designed to promote economic prosperity, strengthen governance, and improve security in the region.58 The Obama Administration introduced the new strategy and sought to significantly increase assistance for Honduras and its neighbors following a surge in migration from Central America in 2014. Congress has appropriated nearly $2.1 billion for the strategy through the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) since FY2016, including at least $431 million for Honduras (see Table 1).

|

Foreign Assistance Account |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

Bilateral Aid, Subtotal |

98.3 |

95.3 |

79.8 |

65.8 |

|

Development Assistance |

93.0 |

90.0 |

75.0 |

- |

|

Economic Support and Development Fund |

- |

- |

- |

65.0 |

|

International Military Education and Training |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Foreign Military Financing |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

- |

|

Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), Subtotala |

84.8 |

72.7 |

NA |

NA |

|

Economic Support Fund |

35.5 |

28.5 |

NA |

NA |

|

International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement |

49.3 |

44.2 |

NA |

NA |

|

Total |

183.1 |

168.0 |

79.8a |

65.8a |

Sources: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations, FY2018-FY2019; the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 115-141; USAID, "Congressional Notification: Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI)," CN #15, October 14, 2016; USAID, "Congressional Notification: Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI)," CN #134, June 22, 2018; U.S. Department of State, "Congressional Notification 16-282—State Western Hemisphere Regional: Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), Honduras," October 13, 2016; and U.S. Department of State, "Congressional Notification 18-117—State Western Hemisphere Regional: Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), Honduras," May 16, 2018.

Notes: Honduras receives some additional assistance from other U.S. agencies, such as the Inter-American Foundation and the Department of Defense. (See "Counternarcotics" for information on Department of Defense security cooperation).

a. CARSI funding levels are not yet available for FY2018 and FY2019.

Conditions on Assistance

Congress has placed strict conditions on assistance to Honduras in each of the foreign aid appropriations measures enacted since FY2016 in an attempt to bolster political will in the country and ensure the assistance is used as effectively as possible. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) requires 25% of assistance for the central government of Honduras to be withheld until the Secretary of State certifies that the Honduran government is informing its citizens of the dangers of the journey to the United States, combating human smuggling and trafficking, improving border security, and cooperating with the U.S. government on the repatriation of Honduran citizens who do not qualify for asylum. Another 50% of assistance for the central government must be withheld until the Secretary of State certifies that the Honduran government is addressing 12 other concerns, including combating corruption; countering gangs and organized crime; increasing government revenues; supporting programs to reduce poverty and promote equitable economic growth; and protecting the rights of journalists, political opposition parties, and human rights defenders to operate without interference. The State Department certified that Honduras met all of theboth sets of conditions in FY2016 and FY2017 but has yet to certify the country. It also certified that Honduras has met the first set of conditions for FY2018.

FY2019 Request

The Trump Administration's FY2019 foreign aid budget request includes nearly $66 million in bilateral assistance for Honduras, which would be $14 million (18%) less than Congress appropriated in FY2018. All of the aid, with the exception of $750,000 to train the Honduran military, would be provided through a new Economic Support and Development Fund foreign assistance account. About $24.4 million would be used to strengthen government institutions and basic service provision and encourage civil society engagement and oversight. Approximately $19 million would support food security, income generation, and natural resource management in rural communities. Another $13 million would be dedicated to education programs designed to improve the quality of basic education and increase access to formal schooling for at-risk youth. The remaining $8.5 million would be used to foster employment and income growth through competitive and inclusive markets. The Administration also requested $263.2 million for the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), though it is unclear how much of that assistance would be allocated to Honduras to support law enforcement operations, strengthen justice-sector institutions, and implement crime and violence prevention programs.59

The Senate and House Appropriations Committees reported their respective FY2019 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations measures (S. 3108 and H.R. 6385) on June 21 and July 16, 2018. According to S.Rept. 115-282, the Senate Appropriations Committee's bill would provide $68.8 million for Honduras and $254.7 million for CARSI. The assistance would be provided under the same terms and conditions as the assistance appropriated in FY2018. According to H.Rept. 115-829, the House Appropriations Committee's bill would provide up to $595 million for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and would provide the Secretary of State with the flexibility to allocate the funds among the nations of the region. The measure would require 50% of assistance for the central government of Honduras to be withheld until the Secretary of State certifies that the Honduran government has met conditions similar to those enacted in FY2018.

Migration Issues

Migration issues have played a central role in U.S.-Honduran relations in recent years. As of 2016, approximately 575,000 individuals born in Honduras resided in the United States and an estimated 350,000 (61%) of them were in the country without authorization.60 Migration from Honduras to the United States is driven primarilytraditionally has been driven by high levels of poverty and unemployment; however, the poor security situation in Honduras has increasingly played a role as well. According to a February 2018 poll, nearly 55% of Hondurans have had a family member emigrate in the past four years; 83% of those who had family members emigrate reported that their relatives left Honduras due to the lack of economic opportunity and 11% reported that their relatives left as a result of insecurity.61

Recent Migration Flows

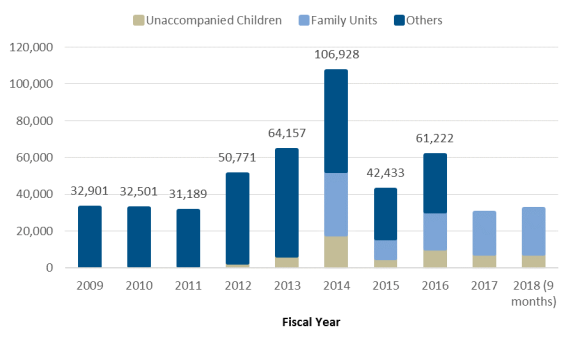

U.S.-Honduran migration ties have received renewed attention in recent yearssince 2014 as a result of a significant increase in the number of Honduran migrants and asylum seekers arriving at the U.S. border. U.S. apprehensions of Honduran nationals more than tripled from about 33,000 in FY2009 to nearly 107,000 in FY2014. Much of the increase was driven by unaccompanied children and families seeking humanitarian protection. Although mixed migrant flows from Honduras have declined since FY2014, the number of Honduran children and families attempting to enter the United States remains high compared to the recent past (see Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. U.S. Apprehensions of Honduran Nationals: FY2009-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Yearbooks of Immigration Statistics, at https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook; and U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions," press releases, at https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. Notes: Unaccompanied children = children under 18 years old without a parent or legal guardian at the time of apprehension. Family units = total number of individuals (children under 18 years old, parents, or legal guardians) apprehended with a family member. Family unit data is not available prior to FY2014. |

The Honduran government has taken a number of steps intended to deter migration to the United States since 2014. It has run public-awareness campaigns to inform Hondurans about the potential dangers of unauthorized migration and deployed security forces along the country's borders to combat human smuggling. The Honduran government also has improved its services for repatriated migrants to encourage returnees to remain in the country rather than seek reentry to the United States.62

The Honduran and U.S. governments are now focusing on addressing the root causes of emigration. President Hernández joined with his counterparts in El Salvador and Guatemala to launch the "Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle," which aims to foster economic growth, improve security conditions, strengthen government institutions, and increase opportunities for the citizens of the region. The U.S. government is supporting complementary efforts through the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America (see "Foreign Assistance").

Deportations and Temporary Protected Status

Over the past five years, the U.S. and Honduran governments have sought to deter migration in various ways. Both governments have run public-awareness campaigns to inform Hondurans about the potential dangers of unauthorized migration and to correct possible misperceptions about U.S. immigration policies. The U.S. government reportedly is spending about $1.3 million on billboard, radio, and television advertisements across Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.63 Some analysts have questioned the effectiveness of such deterrence campaigns, however, with one recent study finding that Hondurans' "views of the dangers of migration to the United states, or the likelihood of deportation, do not seem to influence their emigration plans in any meaningful way."64 The U.S. and Honduran governments also have sought to combat human smuggling. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has worked with the Honduran national police to establish two Transnational Criminal Investigative Units. In the first seven months of 2018, the units initiated 32 human trafficking and smuggling investigations, made 20 arrests, and conducted biometric vetting of nearly 2,700 Honduran and third-country migrants. DHS has provided additional support to the Honduran national police's Special Tactical Operations Group, which conducts checkpoints along the Guatemalan border and specializes in detecting and interdicting human smuggling operations.65 Moreover, both countries have launched initiatives intended to address the root causes of emigration. President Hernández joined with his counterparts in El Salvador and Guatemala to establish the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle, which aims to foster economic growth, improve security conditions, strengthen government institutions, and increase opportunities for the region's citizens. The Honduran government reportedly has allocated $2.9 billion to advance those objectives over the past three years.66 As noted above (see "Foreign Assistance"), the U.S. government is supporting complementary efforts through the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America. These initiatives may take several years to bear fruit, as research suggests the relationship between development and migration is complex. Numerous studies have found that economic development may increase outward migration initially by removing the financial barriers faced by households in poverty. These findings suggest that foreign aid programs that provide financial support or skills training without simultaneously ensuring the existence of local opportunities for individuals to use those new assets may end up intensifying rather than alleviating migration flows.67 President Trump threatened to cut aid to Honduras in April and October 2018 in response to large caravans of Honduran migrants making their way toward the United States.68 Nevertheless, in August 2018, his Administration certified that the Honduran government was informing its citizens of the dangers of the journey to the southwest border of the United States; combatting human smuggling and trafficking; improving border security, including preventing illegal immigration, human smuggling and trafficking, and trafficking of illicit drugs and other contraband; and cooperating with U.S. government agencies and other governments in the region to facilitate the return, repatriation, and reintegration of illegal migrants arriving at the southwest border of the United States who do not qualify for asylum, consistent with international law. The certification allows the State Department to obligate 25% of aid for the Honduran government that otherwise would be withheld.69Nearly 22,400 Hondurans were removed (deported) from the United States in FY2017, making Honduras the third-largest recipient of deportees in the world behind Mexico and Guatemala.63or FY2018.

Honduran leaders also are concerned about the potential economic impact of deportations because the Honduran economy is heavily dependent on the remittances of migrant workers abroad. In 2017, Honduras received $4.3 billion (equivalent to 18.7% of GDP) in remittances.6471 Given that remittances are the primary source of income for more than one-third of the Honduran households that receive them, a sharp reduction in remittances could have a dramatic effect on socioeconomic conditions in the country.6572 According to the analysis of the Honduran Central Bank, however, remittance levels traditionally have been more associated with the performance of the U.S. economy than the number of deportations from the United States.66

Since 1999, the U.S. government has provided temporary protected status (TPS) to some 86,000 Hondurans, allowing individuals who could otherwise be deported to stay in the United States. The United States first provided TPS to Hondurans in the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch, which killed nearly 5,700 people, displaced 1.1 million others, and produced more than $5 billion in damages in 1998.6774 TPS for Honduras was extended 14 times before the Trump Administration announced the program's termination in May 2018. Current beneficiaries, who have an estimated 53,500 U.S.-born children,75 have until January 5, 2020 to seek an alternative lawful immigration status or depart from the United States.

Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen asserts that the termination was required since "the disruption of living conditions in Honduras from Hurricane Mitch that served as the basis for its TPS designation has ceased to a degree that it should no longer be regarded as substantial."6876 Some analysts disagree; they argue that the Secretary's decision ignores ongoing economic, security, and governance challenges in Honduras, and will ultimatelycould undermine U.S. and Honduran efforts to address the root causes of irregular migration.6977 In 2017, TPS beneficiaries sent an estimated $176 million in cash remittances to Honduras, which is roughly the same amount that the U.S. government provided to Honduras in foreign aid.78 A range of proposals related to TPS have been introduced in the 115th Congress, including measures that would extend it, limit it, adjust some TPS holders to lawful permanent resident status, or make TPS holders subject to expedited removal.70

Security Cooperation

The United States and Honduras have cooperated closely on security issues for many years. Honduras served as a base for U.S. operations designed to counter Soviet influence in Central America during the 1980s and has hosted a U.S. troop presence—Joint Task Force Bravo—ever since (see the text box, "Joint Task Force Bravo"). Current bilateral security efforts primarily focus on citizen safety and drug trafficking.

|

Joint Task Force Bravo The United States maintains a troop presence of about 500 military personnel known as Joint Task Force (JTF) Bravo at Soto Cano Air Base in Honduras. JTF Bravo was first established in 1983 with about 1,200 troops who were involved in military training exercises and supporting U.S. counterinsurgency and intelligence operations in the region. In the aftermath of Hurricane Mitch in 1998, U.S. troops provided extensive assistance in the relief and reconstruction effort. Today, U.S. troops in Honduras support activities throughout Central America, such as disaster relief, medical and humanitarian assistance, and counternarcotics operations. |

Citizen Safety

As noted previously, Honduras faces significant security challenges (see "Security Conditions"). Many citizens contend with criminal threats on a daily basis, ranging from petty theft to extortion and forced gang recruitment. The U.S. government has sought to assist Honduras in addressing these challenges, often using funds appropriated through CARSI.

USAID has used CARSI funds to implement a variety of crime- and violence-prevention programs. USAID interventions include primary prevention programs that work with communities to create safe spaces for families and young people, secondary prevention programs that identify the youth most at risk of engaging in violent behavior and provide them and their families with behavior-change counseling, and tertiary prevention programs that seek to reintegrate juvenile offenders into society. According to a 2014 impact evaluation, Honduran communities where USAID implemented crime- and violence-prevention programs reported 35% fewer robberies, 43% fewer murders, and 57% fewer extortion attempts than would have been expected based on trends in similar communities without a USAID presence.71

Other CARSI-funded efforts in Honduras are designed to support law enforcement and strengthen rule-of-law institutions. The State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) has established "model police precincts," which are designed to build local confidence in law enforcement by converting police forces into more community-based, service-oriented organizations. INL also has supported efforts to purge the Honduran national police of corrupt officers, helped establish a criminal investigative school, and helped stand up the criminal investigation and forensic medicine directorates within the public prosecutor's office. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) leads a Transnational Anti-Gang Unit designed to interrupt criminal gang activity, including kidnappings and extortion.

USAID and INL have begun to integrate their respective prevention and law enforcement interventions as part of a "place-based strategy" that seeks to concentrate U.S. efforts within the most dangerous communities in Honduras.

Counternarcotics

Honduras is a major transshipment point for illicit narcotics as a result of its location between cocaine producers in South America and consumers in the United States. In 2017, the State Department reported that 3-4 metric tons of cocaine transit through Honduras every month. The Caribbean coastal region of the country is a primary landing point for both maritime and aerial traffickers due to its remoteness, limited infrastructure, and lack of government presence.72

The U.S. government has sought to strengthen counternarcotics cooperation with Honduras to reduce illicit flows through the country. Although the United States has not provided the Honduran government with any assistance that would support aerial interdiction since Honduras enacted an aerial intercept law in 2014,7382 close bilateral cooperation has continued in several other areas. U.S. agencies, including the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), have used CARSI funds to establish and support specially vetted units and task forces designed to combat transnational criminal organizations. These units, which include U.S. advisers and selected members of the Honduran security forces, carry out complex investigations into drug trafficking, money laundering, and other transnational crime.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) provides additional counternarcotics assistance to Honduras. This support includes equipment intended to extend the reach of Honduran security forces and enable them to better control their national territories. It also includes specialized training. For example, U.S. Special Operations Forces have helped finance and train the TIGRES unit of the Honduran national police, which has been employed as a counterdrug SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) team.7483 DOD counternarcotics assistance to Honduras totaled nearly $12 million in FY2016 and $12.4 million in FY2017. DOD is planningplanned to provide Honduras with at least $5.7 million of assistance to support ground and maritime interdiction efforts in FY2018.75

As a result of this cooperation, U.S. and Honduran authorities have successfully apprehended numerous high-level drug traffickers and dismantled their criminal organizations. The Honduran government has extradited at least 18 Honduran narcotics traffickers to the United States since 2013. More than a dozen others facing potential extradition have turned themselves in directly to U.S. law enforcement authorities.7685 Many of those now in U.S. custody previously had been designated by the U.S. Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Asset Control as Specially Designated Narcotics Traffickers pursuant to the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (P.L. 106-120, as amended; 21 U.S.C. 1901 et seq.), freezing their assets and prohibiting U.S. citizens from conducting financial or commercial transactions with them.7786

Nevertheless, bilateral counternarcotics efforts face a number of challenges. Honduras's criminal underworld has begun to reorganize, with new leaders and groups emerging to fill the vacuum left behind by the dismantled organizations.7887 This reorganization could lead to an escalation in violence in Honduras as the new groups battle one another for control of the lucrative trafficking business.

Moreover, there are continued indications that organized crime has co-opted many Honduran officials. In September 2017, Fabio Lobo, the son of former President Porfirio Lobo (2010-2014), was sentenced to 24 years in prison for conspiring to import cocaine into the United States. According to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Fabio Lobo connected Honduran drug traffickers, including the Cachiros organization, to corrupt politicians and security forces who provided protection and government contracts in exchange for bribes.7988 DOJ has charged two Honduran members of congress with related offenses.8089 In U.S. federal court testimony, Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga, the former leader of the Cachiros, has implicated several other prominent Honduran politicians, including former President Lobo and Antonio Hernández—President Hernández's brother and a former member of congress. The Honduran public prosecutor's office and the MACCIH reportedly are investigating the allegations, which Lobo and Hernández have denied.81

U.S.-Honduran counternarcotics efforts also have generated controversy. In April 2012, the DEA and its vetted unit within the Honduran national police, with operational support from the State Department and CBP, initiated a 90-day pilot program known as Operation Anvil to disrupt drug transportation flights from South America to Honduras. Three joint interdiction missions carried out as part of the operation ended with suspects being killed, including a May 2012 incident in which the vetted unit opened fire on a river taxi, killing four people and injuring four others. In a January 2013 letter, 58 Members of Congress called on the State Department and DOJ to carry out a "thorough and credible investigation" into the killings.82

In May 2017, the State Department and DOJ Offices of Inspectors General released a joint report on the three deadly force incidents. The report found that

- DEA had not adequately planned for Operation Anvil, failing to establish a clear understanding between DEA and Honduran personnel regarding the use of deadly force and failing to ensure appropriate mechanisms were in place to respond to shooting incidents;

- DEA personnel maintained substantial control over the May 2012 interdiction mission and made critical decisions, such as directing a Honduran door gunner on a helicopter to open fire on the river taxi, despite DEA's insistence that the mission was Honduran-led;

- DEA's post incident review of the May 2012 mission was significantly flawed;

- DEA inappropriately and unjustifiably withheld information about the May 2012 incident from the U.S. ambassador to Honduras;

- INL failed to comply with, and undermined, the ambassador's chief of mission authority by refusing to cooperate with investigations into the May 2012 incident;

- DEA provided inaccurate and incomplete information to DOJ leadership and Congress regarding the May 2012 incident, including that there had been an exchange of gunfire between Honduran officers and the river taxi despite a lack of evidence that anyone on the passenger boat had fired at any time; and

- the State Department provided inaccurate and incomplete information to Congress and the public.

The report also raised serious questions about the security forces with which the U.S. government chooses to partner. According to the report, Honduran officers, who had been vetted by the DEA, filed inaccurate reports about the three deadly force incidents and planted a gun at one of the crime scenes. Although DEA officials were aware of the inaccurate reports and planted weapon, they took no action.83

In a July 2017 letter to then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Attorney General Jeff Sessions, four U.S. Senators expressed alarm that DEA and INL officials misled Members of Congress and congressional staff and that no official in either department has been subject to disciplinary action. The letter called on the State Department and DOJ to describe how they intend to discipline the U.S. personnel involved in the three deadly force incidents and their aftermath as well as how the agencies will encourage the Honduran government to hold accountable the Honduran officers who attempted to cover up the incidents.84

Human Rights Concerns

In recent years, human rights organizations have alleged a wide range of abuses by Honduran security forces acting in their official capacities or on behalf of private interests or criminal organizations. In perhaps the most high-profile case, Berta Cáceres, an indigenous and environmental activist, was killed in March 2016, apparently as a result of her efforts to prevent the construction of a hydroelectric damproject. To date, the Honduran government has arrested nine individuals tied to her murder, including an executive at the firm carrying out the project, a retired Honduran army lieutenant, and an active-duty army major who had served in the special forces and as chief of army intelligence.8594 The Honduran government also has arrested two police investigators who allegedly tried to cover up the crime.8695 A trial of eight of the accused began on October 20, 2018, but Cáceres's family and some outside observers have expressed concerns that prosecutors have not properly investigated the case.96 Numerous similar attacks have been carried out against journalists and other human rights defenders, including leaders of Afro-descendent, indigenous, land rights, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender), and workers' organizations. The extent to which Honduran security forces have been involved in those attacks is unclear since 97% of crimes committed against human rights defenders remain unresolved.87

The Honduran government often has attributed attacks against journalists, human rights defenders, and political and social activists to the country's high level of generalized violence and downplayed the possibility that the attacks may be related to the victims' work. Such attacks have persisted, however, even as annual homicides have fallen 46% from a peak of 7,172 in 2012 to 3,866 in 2017.8898 According to the Honduran government's national commissioner for human rights, 32 journalists and social communicators were killed from 2014-2017 while 33 were killed from 2010-2013.8999 Similarly, a coalition of domestic election observers documented 62 political killings during the 2017 electoral process, up from 48 in 2013.90

Human rights advocates also have criticized the Honduran government's "widespread practice of criminalizing human rights defenders for their human rights work, in particular in the context of exercising their right to protest and freedom of expression."91101 President Hernández and high-ranking members of his administration have repeatedly dismissed protests and sought to justify repressive actions by the Honduran security forces by characterizing members of the political opposition and social movements as criminals, drug traffickers, and gang members.92102 The Honduran government also has brought criminal charges, such as defamation and trespassing, against journalists and human rights defenders, subjecting them to lengthy proceedings "to intimidate them and subdue their human rights advocacy."93103

U.S. Initiatives

Human rights promotion has long been an objective of U.S. policy in Honduras, though some analysts argue that it has been subordinated to other U.S. interests, such as maintaining bilateral security cooperation. The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America has 13 sub-objectives, one of which is ensuring that Central American governments uphold democratic values and practices, including respect for human rights. The Trump Administration, like the Obama Administration before it, generally has refrained from publically criticizing the Honduran government over human rights abuses, but has sought to support Honduran efforts to improve the situation. For example, the U.S. and Honduran governments maintain a high-level bilateral human rights working group, which has met six times since it was launched in 2012. The most recent meeting, held in April 2018, focused on efforts to strengthen the Honduran government's human rights institutions, improve cooperation with international partners and civil society, foster citizen security, combat corruption and impunity, and address migration issues.94

The U.S. government also has allocated foreign assistance to promote human rights in Honduras, though the total amount of funding dedicated to human rights activities is unclear. USAID is working with Honduran government institutions and human rights organizations on the implementation of a 2015 law that created a protection mechanism for journalists, human rights defenders, and justice sector officials. Among other activities, the program is supporting efforts to develop early warning systems, conduct risk analyses, and improve the processes for providing protective measures.95105 As of early May 2018, the Honduran government's protection mechanism had provided 810 protection measures to 211 individuals, including 125 human rights defenders, 37 journalists, 22 social communicators, and 14 justice sector officials. The protective measures have included self-protection trainings, technological and infrastructure measures, police escorts, and temporary relocations and evacuations. Many human rights defenders do not trust the protection mechanism, however, due to its heavy reliance on the national police, which continues to be viewed as one of the principal perpetrators of human rights violations in Honduras.96

The U.S. government also supports efforts to strengthen the rule-of-law and reduce impunity in Honduras. USAID is providing assistance to the Honduran government and civil society organizations to support the development of more effective, transparent, and accountable judicial institutions, with a particular focus on guaranteeing equal access to justice for women, youth, LGBT individuals, and other victims of human rights abuses.97107 INL also supports a variety rule-of-law initiatives, including two specialized task forces that investigate high-profile crimes: the Violent Crimes Task Force, which focuses on attacks against journalists and activists, and the Bajo Aguán Task Force, which focuses on homicides related to long-standing land disputes in the Bajo Aguán region. The task forces include vetted members of the Honduran national police, the public prosecutor's office, and U.S. advisers. According to the State Department, the Bajo Aguán Task Force has performed 20 exhumations, obtained 44 arrest warrants, made 23 arrests, and secured 11 homicide convictions since 2014.98108

Human Rights Restrictions on Foreign Assistance

The U.S. government has placed restrictions on some foreign assistance due to human rights concerns. Like all countries, Honduras is subject to legal provisions (codified at 22 U.S.C. 2378d and 10 U.S.C. 362) that require the State Department and the Department of Defense to vet foreign security forces and prohibit funding for any military or other security unit if there is credible evidence that it has committed "a gross violation of human rights."99109 In other cases, the U.S. government has chosen not to work with certain Honduran security forces as a matter of policy. For example, the United States has never provided any assistance to the military police force,100110 which was created in 2013 and has been implicated in numerous human rights abuses, including 13 of the 16 post-election killings documented by the OHCHR.101111 Some members of the Honduran military who have received U.S. training, however, have subsequently been assigned to the military police.102

Congress has placed additional restrictions on U.S. security assistance to Honduras over the past seven years. From FY2012-FY2015, annual foreign aid appropriations measures required the State Department to withhold between 20% and 35% of aid for Honduran security forces until the Secretary of State could certify that certain human rights conditions were met. Since FY2016, annual appropriations measures have required the State Department to withhold 50% of aid for the central government of Honduras until the Secretary of State can certify that the Honduran government is addressing 12 congressional concerns, including

- investigating and prosecuting in the civilian justice system government personnel, including military and police personnel, who are credibly alleged to have violated human rights, and ensuring that such personnel are cooperating in such cases;

- cooperating with commissions against corruption and impunity and with regional human rights entities; and

- protecting the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference.

103

113The State Department has certified that Honduras has met the conditions necessary to release assistance every year. Most recently, it issued a certification for assistance appropriated for FY2017 on November 28, 2017—two days after the disputed presidential election. In the memorandum of justification accompanying the certification, the State Department noted that Honduran public prosecutors had charged 73 members of the Honduran national police, seven members of the regular military, and six members of the military police force with human rights violations from January-April 2017. It also noted that the Honduran government had taken steps to comply with precautionary measures issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which obligate the government to provide protection for individuals at risk of serious human rights abuses. The memorandum highlighted President Hernández's decision to create a ministry of human rights, and the Honduran government's protection mechanism for journalists, human rights defenders, and justice sector officials.104114 Human rights defenders and some Members of Congress criticized the certification, with one Honduran union leader reportedly declaring, "They're practically giving carte blanche so they can violate human rights in this country under the umbrella of the United States."105115

The FY2019 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations measures (S. 3108 and H.R. 6385) reported out of the Senate and House Appropriations committees, would both maintain human rights conditions on 50% of assistance for the central government of Honduras. Another measure, the Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act (H.R. 1299), would expand on the current conditions by suspending all U.S. security assistance to Honduras and directing U.S. representatives at multilateral development banks to oppose all loans for the Honduran security forces until the State Department certifies that Honduras has met a number of strict conditions.

Commercial Ties

The United States and Honduras have maintained close commercial ties for many years. In 1984, Honduras became one of the first beneficiaries of the Caribbean Basin Initiative, a unilateral U.S. preferential trade arrangement providing duty-free importation for many goods from the region. In the late 1980s, Honduras benefitted from production-sharing arrangements with U.S. apparel companies for duty-free entry into the United States of certain apparel products assembled in Honduras. As a result, maquiladoras, or export-assembly companies, flourished. The passage of the Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act (P.L. 106-200) in 2000, which provided Caribbean Basin nations with North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)-like preferential tariff treatment, further boosted the maquila sector.

Commercial relations have expanded most recently as a result of the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), which significantly liberalized trade in goods and services after entering into force in 2006. CAFTA-DR has eliminated tariffs on all consumer and industrial goods and is scheduled to phase out tariffs on nearly all agricultural products by 2020.106116 Although U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has asserted that CAFTA-DR and other trade arrangements throughout Latin America "need to be modernized," the Trump Administration has not yet sought to renegotiate the agreement.107

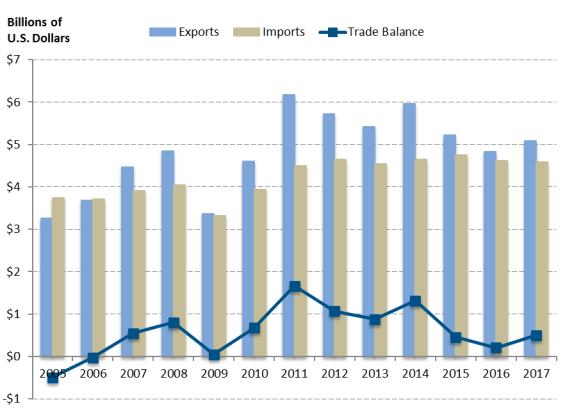

Trade and Investment

Despite a significant decline in bilateral trade in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, total merchandise trade between the United States and Honduras has increased 38% since 2005; U.S. exports to Honduras have grown by 56%, and U.S. imports from Honduras have grown by 22% (see Figure 4). Analysts had predicted that CAFTA-DR would lead to a relatively larger increase in U.S. exports because a large portion of imports from Honduras already entered the United States duty free prior to implementation of the agreement. The United States has run a trade surplus with Honduras since 2007.

Source: CRS presentation of U.S. Department of Commerce data obtained through Global Trade Atlas, July 2018.

Total two-way trade amounted to $9.7 billion in 2017, $5.1 billion in U.S. exports to Honduras and $4.6 billion in U.S. imports from Honduras. The United States was Honduras's largest trading partner and Honduras was the 47th-largest trading partner of the United States. Top U.S. exports to Honduras included textile and apparel inputs, such as yarns and fabrics, refined oil products, and electric and heavy machinery. Top U.S. imports from Honduras included apparel, insulated wire, fruit, and coffee.

108

|

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of U.S. Department of Commerce data obtained through Global Trade Atlas, July 2018. |