Social Security: The Trust Funds

Changes from July 10, 2018 to May 8, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Social Security: The Trust Funds

Contents

- Introduction

- How the Social Security Program Is Financed

- The Social Security Trust Funds as Designated Accounts

- Social Security Trust Fund Revenues

- Social Security Trust Fund Costs

- Social Security Trust Fund Operations

- Investment of the Social Security Trust Funds

- Off-Budget Status of the Social Security Trust Funds

- The Social Security Trust Funds as Accumulated Holdings

- The Social Security Trust Funds and the Level of Federal Debt

- The Social Security Trust Funds and Benefit Payments

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Operations of the Social Security Trust Funds, Historical Period 1957-

20172018

- Table 2. Projected Operations of the Social Security Trust Funds,

2018-20332019-2034

- Table 3.

20172018

- Table 4. Projected Accumulated Holdings of the Social Security Trust Funds,

2018-20332019-2034

- Table A-1.Key Dates Projected for the Social Security Trust Funds as Shown Under the Intermediate Assumptions in Trustees Reports from 1983 to 2018

Appendixes

Summary

The Social Security program pays monthly cash benefits to retired or disabled workers and their family members and to the family members of deceased workers. Program income and outgo are accounted for in two separate trust funds authorized under Title II of the Social Security Act: the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and the Federal Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund. Projections show that the OASI fund will remain solvent until 2034, whereas the DI fund will remain solvent until 20322052, meaning that each trust fund is projected to be able topayto pay benefits scheduled under current law in full and on time up to that point. Following the depletion of trust fund reserves (20322052 for DI and 2034 for OASI), continuing income to each fund is projected to cover 9691% of DI scheduled benefits and 77% of OASI scheduled benefits. The two trust funds are legally distinct and do not have authority to borrow from each other. However, Congress has authorized the shifting of funds between OASI and DI in the past to address shortfalls in a particular fund. Therefore, this CRS report discusses the operations of the OASI and DI trust funds on a combined basis, referring to them collectively as the Social Security trust funds. On a combined basis, the trust funds are projected to remain solvent until 20342035. Following depletion of combined trust fund reserves at that point, continuing income is projected to cover 7980% of scheduled benefits.

Social Security is financed by payroll taxes paid by covered workers and their employers, federal income taxes paid by some beneficiaries on a portion of their benefits, and interest income from the Social Security trust fund investments. Social Security tax revenues are invested in U.S. government securities (special issues) held by the trust funds, and these securities earn interest. The tax revenues exchanged for the U.S. government securities are deposited into the General Fund of the Treasury and are indistinguishable from revenues in the General Fund that come from other sources. Because the assets held by the trust funds are U.S. government securities, the trust fund balance represents the amount of money owed to the Social Security trust funds by the General Fund of the Treasury. Funds needed to pay Social Security benefits and administrative expenses come from the redemption or sale of U.S. government securities held by the trust funds.

The Social Security trust funds represent funds dedicated to pay current and future Social Security benefits. However, it is useful to view the trust funds in two ways: (1) as an internal federal accounting concept and (2) as the accumulated holdings of the Social Security program.

By law, Social Security tax revenues must be invested in U.S. government obligations (debt instruments of the U.S. government). The accumulated holdings of U.S. government obligations are often viewed as being similar to assets held by any other trust on behalf of the beneficiaries. However, the holdings of the Social Security trust funds differ from those of private trusts because (1) the types of investments the trust funds may hold are limited and (2) the U.S. government is both the buyer and seller of the investments.

This report covers how the Social Security program is financed and how the Social Security trust funds work.

Introduction

The Social Security program pays benefits to retired or disabled workers and their family members and to the family members of deceased workers.1 As of April 2018March 2019, there were 6263.3 million Social Security beneficiaries. Approximately 6970% of those beneficiaries were retired workers and 1413% were disabled workers. The remaining beneficiaries were the survivors of deceased insured workers or the spouses and children of retired or disabled workers.2

Social Security is financed primarily by payroll taxes paid by covered workers and their employers. The program is also credited with federal income taxes paid by some beneficiaries on a portion of their benefits, reimbursements from the General Fund of the Treasury for various purposes, and interest income from investments held by the Social Security trust funds. Social Security tax revenues are invested in U.S. government securities (special issues) held by the trust funds, and these securities earn interest. The tax revenues exchanged for the U.S. government securities are deposited into the General Fund of the Treasury and are indistinguishable from revenues in the General Fund that come from other sources. Because the assets held by the trust funds are U.S. government securities, the trust fund balance represents the amount of money owed to the Social Security trust funds by the General Fund of the Treasury. Funds needed to pay Social Security benefits and administrative expenses come from the redemption or sale of U.S. government securities held by the trust funds.3

The Secretary of the Treasury (the Managing Trustee of the Social Security trust funds) is required by law to invest Social Security revenues in securities backed by the U.S. government.4 The purchase of U.S. government securities allows any surplus Social Security revenues to be used by the federal government for other (non-Social Security) spending needs at the time. This trust fund financing mechanism allows the General Fund of the Treasury to borrow from the Social Security trust funds. In turn, the General Fund pays back the trust funds (with interest) when the trust funds redeem the securities. The process of investing Social Security revenues in securities and redeeming the securities as needed to pay benefits is ongoing.

The Social Security trust funds are both designated accounts within the U.S. TreasuryTreasury and the accumulated holdings of special U.S. government obligations. Both represent the funds designated to pay current and future Social Security benefits.

How the Social Security Program Is Financed

The Social Security program is financed primarily by revenues from Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes and Self-Employment Contributions Act (SECA) taxes. FICA taxes are paid by both employers and employees, but it is employers who remit the taxes to the U.S. Treasury. Employers remit FICA taxes on a regular basis throughout the year (e.g., weekly, monthly, quarterly or annually), depending on the employer's level of total employment taxes (including FICA and federal personal income tax withholding). The FICA tax rate of 7.65% each for employers and employees has two components: 6.2% for Social Security and 1.45% for Medicare Hospital Insurance. The SECA tax rate is 15.3% for self-employed individuals, with 12.4% for Social Security and 2.9% for Medicare Hospital Insurance. The respective Social Security contribution rates are levied on covered wages and net self-employment income up to $128,400 in 2018132,900 in 2019.5 Self-employed individualsindividuals may deduct one-half of the SECA taxes for federal income tax purposes.6 SECA taxes are normally paid once a year as part of filing an annual individual income tax return. In 20172018, Social Security payroll taxes totaled $873.6885.1 billion and accounted for 87.788.2% of the program's total income.7

In addition to payroll taxes, the Social Security program receives income from other sources. First, certain Social Security beneficiaries must include a portion of their Social Security benefits in taxable income for the federal income tax, and the Social Security program receives a portion of those taxes.8 In 20172018, revenue from the taxation of benefits totaled $37.935.0 billion, accounting for 3.85% of the program's total income. Second, the program receives reimbursements from the General Fund of the Treasury for a variety of purposes.9 General Fund reimbursements totaled $0.12 billion, accounting for less than 0.1% of the program's total income.10 Finally, the Social Security program receives interest income from the U.S. Treasury on its investments in special U.S. government obligations. Interest income totaled $85.183.3 billion, accounting for 8.53% of the program's total income.11

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) processes the tax returns and tax payments for federal employment taxes and federal individual income taxes. All of the tax payments are deposited in the U.S. Treasury along with all other receipts from the public for the federal government.

The Social Security Trust Funds as Designated Accounts

Within the U.S. Treasury, there are numerous accounts established for internal accounting purposes. Although all of the monies within the U.S. Treasury are federal monies, the designation of an account as a trust fund allows the government to track revenues dedicated for specific purposes (as well as expenditures). In addition, the government can affect the level of revenues and expenditures associated with a trust fund through changes in the law.12

Social Security program income and outgo are accounted for in two separate trust funds authorized under Title II of the Social Security Act: (1) the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and (2) the Federal Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund.13 Under current law, the two trust funds are legally distinct and do not have authority to borrow from each other. This is important given projections showing that the asset reserves held by the OASI fund will be depleted in 2034, whereas the asset reserves held by the DI fund will be depleted in 20282052. Following the depletion of trust fund reserves (20322052 for DI and 2034 for OASI), continuing income is projected to cover 9691% of DI scheduled benefits and 77% of OASI scheduled benefits. In the past, Congress has authorized temporary interfund borrowing and payroll tax reallocations between OASI and DI to address funding imbalances. This CRS report discusses the operations of the OASI and DI trust funds on a combined basis, referring to them collectively as the Social Security trust funds. On a combined basis, the trust funds are projected to remain solvent until 20342035, at which point continuing income is projected to cover 7980% of program costs. (For a discussion of the status of the DI trust fund, see CRS Report R43318, The Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund: Background and Current Status.)

Social Security Trust Fund Revenues

The Social Security trust funds receive a credit equal to the Social Security payroll taxes deposited in the U.S. Treasury by the IRS.14 The payroll taxes are allocated between the OASI and DI trust funds based on a proportion specified by law.15 A provision included in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) temporarily directs a larger share of total payroll tax revenues to the DI fund. For 2016 to 2018, the 12.4% payroll tax rate is allocated as follows: 10.03% for the OASI fund and 2.37% for the DI fund. Beginning in 2019, the allocation reverts back to 10.6% for the OASI fund and 1.8% for the DI fund.16

Social Security Trust Fund Costs

The U.S. Treasury makes Social Security benefit payments to individuals on a monthly basis, as directed by the Social Security Administration (SSA) as to whom to pay and the amount of the payment. When benefit payments are made by the U.S. Treasury, the Social Security trust funds are debited for the payments. Periodically, the Social Security trust funds are also debited for the administrative costs of the Social Security program. These administrative costs are incurred by several government agencies, including SSA, the U.S. Treasury, and the IRS.

Social Security Trust Fund Operations

The annual revenues to the Social Security trust funds are used to pay current Social Security benefits and administrative expenses. If, in any year, revenues are greater than costs, the surplus Social Security revenues in the U.S. Treasury are available for spending by the federal government on other (non-Social Security) spending needs at the time. If, in any year, costs are greater than revenues, the cash flow deficit is offset by selling some of the accumulated holdings of the trust funds (U.S. government securities) to help pay benefits and administrative expenses.

There are two measures of Social Security trust fund operations: the annual cash flow operations and the accumulated holdings (or trust fund balance).17 The annual cash flow operations of the Social Security trust funds are a measure of current revenues and current costs. The cash flow operations are positive when current revenues exceed costs (a cash flow surplus) and negative when current costs exceed revenues (a cash flow deficit). In years with cash flow deficits, the Social Security program (unlike other federal programs that operate without a trust fund) may use the accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds from prior years to help pay benefits and administrative expenses.18

Although Social Security is a pay-as-you-go system, meaning that current revenues are used to pay current costs, changes made to the Social Security program in 1983 began a sustained period of annual cash flow surpluses through 2009.19 Since 2010, however, Social Security has had annual cash flow deficits (program costs have exceeded tax revenues). The 20182019 Annual Report of the Social Security Board of Trustees projects that, under their intermediate assumptions, annual cash flow deficits will continue throughout the 75-year projection period (2018-20922019-2093).20

At the end of 20172018, the Social Security trust funds had accumulated holdings (asset reserves) of more than $2.9 trillion. The 20182019 Annual Report projects that the trust funds will have asset reserves (a positive balance) until 20342035, meaning that Social Security benefits scheduled under current law can be paid in full and on time until then. This is the same year projected in last year's report.

In addition, the 20182019 Annual Report shows the 75-year actuarial deficit for the Social Security trust funds. The actuarial deficit is the difference between the present discounted value of scheduled benefits and the present discounted value of future taxes plus asset reserves held by the trust funds. It can be viewed as the amount by which the payroll tax rate would have to be increased to support the level of benefits scheduled under current law throughout the 75-year projection period (or, roughly the amount by which the payroll tax rate would have to be increased for the trust funds to remain fully solvent throughout the 75-year period). The 20182019 Annual Report projects that the 75-year actuarial deficit for the trust funds is equal to 2.8478% of taxable payroll.21 With respect to the change in the projected 75-year actuarial deficit, the trustees state,

A 0.0605 percentage point increase in the OASDI actuarial deficit would have been expected if nothing had changed other than the one-year shift in the valuation period from 20172018 through 2091 to 20182092 to 2019 through 20922093. The effects of updated demographic, economic, and programmatic data, and improved methodologies, collectively reduced the actuarial deficit by 0.0411 percent of taxable payroll, offsetting most of the effect of changing the valuation period.22

As noted above, on a combined basis, the Social Security trust funds are projected to have asset reserves sufficient to pay full scheduled benefits until 20342035. Considered separately, the OASI Trust Fund is projected to have sufficient asset reserves until 2034 (last year's report also projected 20352034 as the depletion year) and the DI Trust Fund is projected to have sufficient asset reserves until 2032 (four2052 (20 years later than projected in last year's report). The trustees note,

In last year's report, the projected reserve depletion years were 2028 for DI and 2035 for OASIyear was the same for OASI and 20 years earlier (2032) for DI. The change in the reserve depletion date for DI is largely due to continuing favorable experience for DI applications and benefit awards. In addition, average benefit levels for disabled-worker beneficiaries were lower than expected in 2017, and are expected to be lower in the future. Disability applications have been declining steadily since 2010, and the total number of disabled-worker beneficiaries in the current payment status has been falling since 2014. The Trustees assume that the recent favorable experience with DI applications and awards is temporary, and that by 2027 DI incidence rates will return to levels projected in last year's report. Accordingly, the projected 75-year actuarial deficit (0.21 percent of taxable payroll) for DI is little changed from last year (0.24 percent)Relative to last year's Trustees Report, disability incidence rates are lower in 2018. They are also assumed to rise more gradually from current levels to reach ultimate levels at the end of 10 years that are slightly lower. Accordingly, the projected Trust Fund depletion date is 20 years later and the 75-year actuarial deficit (0.12 percent of taxable payroll) is 0.09 percentage points lower than was projected last year.23

Table 1 shows the annual cash flow operations of the Social Security trust funds (noninterest income, cost, and cash flow surplus/deficit) for the historical period 1957 to 20172018.24 From 1957 to 1983, the last time Congress enacted major amendments to the program, the Social Security trust funds operated with cash flow deficits (cost exceeded noninterest income) in 1920 of the 2728 years. Since 1984, the trust funds have operated with cash flow deficits in eightnine of the past 3435 years (2010 to 20172018).

Table 1. Operations of the Social Security Trust Funds, Historical Period 1957-2017

($ in billions)

|

Year |

Noninterest Incomea |

Cost |

Cash Flow |

||

|

1957 |

$7.5 |

$7.6 |

|

||

|

1958 |

8.5 |

8.9 |

|

||

|

1959 |

8.9 |

10.8 |

|

||

|

1960 |

11.8 |

11.8 |

|

||

|

1961 |

12.3 |

13.4 |

|

||

|

1962 |

13.1 |

15.2 |

|

||

|

1963 |

15.6 |

16.2 |

|

||

|

1964 |

16.9 |

17.0 |

|

||

|

1965 |

17.2 |

19.2 |

|

||

|

1966 |

22.7 |

20.9 |

|

||

|

1967 |

25.5 |

22.5 |

|

||

|

1968 |

27.5 |

26.0 |

|

||

|

1969 |

32.0 |

27.9 |

|

||

|

1970 |

35.2 |

33.1 |

|

||

|

1971 |

38.9 |

38.5 |

|

||

|

1972 |

43.4 |

43.3 |

|

||

|

1973 |

52.4 |

53.1 |

|

||

|

1974 |

59.4 |

60.6 |

|

||

|

1975 |

64.7 |

69.2 |

|

||

|

1976 |

72.3 |

78.2 |

|

||

|

1977 |

79.5 |

87.3 |

|

||

|

1978 |

89.6 |

96.0 |

|

||

|

1979 |

103.7 |

107.3 |

|

||

|

1980 |

117.4 |

123.5 |

|

||

|

1981 |

140.2 |

144.4 |

|

||

|

1982 |

146.5 |

160.1 |

|

||

|

1983 |

163.0 |

171.2 |

|

||

|

1984 |

183.2 |

180.4 |

|

||

|

1985 |

200.8 |

190.6 |

|

||

|

1986 |

212.9 |

201.5 |

|

||

|

1987 |

225.7 |

209.1 |

|

||

|

1988 |

255.3 |

222.5 |

|

||

|

1989 |

276.7 |

236.2 |

|

||

|

1990 |

298.2 |

253.1 |

|

||

|

1991 |

307.8 |

274.2 |

|

||

|

1992 |

317.2 |

291.9 |

|

||

|

1993 |

327.7 |

308.8 |

|

||

|

1994 |

350.0 |

323.0 |

|

||

|

1995 |

364.5 |

339.8 |

|

||

|

1996 |

385.8 |

353.6 |

|

||

|

1997 |

413.9 |

369.1 |

|

||

|

1998 |

439.9 |

382.3 |

|

||

|

1999 |

471.1 |

392.9 |

|

||

|

2000 |

503.9 |

415.1 |

|

||

|

2001 |

529.1 |

438.9 |

|

||

|

2002 |

546.7 |

461.7 |

|

||

|

2003 |

547.0 |

479.1 |

|

||

|

2004 |

568.7 |

501.6 |

|

||

|

2005 |

607.5 |

529.9 |

|

||

|

2006 |

642.5 |

555.4 |

|

||

|

2007 |

674.7 |

594.5 |

|

||

|

2008 |

689.0 |

625.1 |

|

||

|

2009 |

689.2 |

685.8 |

|

||

|

2010 |

663.6 |

712.5 |

|

||

|

2011 |

690.7 |

736.1 |

|

||

|

2012 |

731.1 |

785.8 |

|

||

|

2013 |

752.2 |

822.9 |

|

||

|

2014 |

786.1 |

859.2 |

|

||

|

2015 |

826.9 |

897.1 |

|

||

|

2016 |

869.1 |

922.3 |

|

||

|

2017 |

911.5 |

952.5 |

|

2018 |

920.1 |

1,000.2 |

| (80 | .1) |

Source: Table prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) from data provided in the 20182019 Annual Report, Table VI.A3, pp. 160-161159-160, at https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2018/tr20182019/tr2019.pdf.

a. Noninterest income is equal to total income minus net interest. Stated another way, noninterest income includes net payroll tax contributions, reimbursements from the General Fund of the Treasury to the Social Security trust funds, and federal income tax revenues from the taxation of Social Security benefits.

Table 2 shows projected cash flow operations of the Social Security trust funds (noninterest income, cost, and cash flow deficits) for the 2018 to 20332019 to 2034 period, as projected by the trustees in the 20182019 Annual Report (under the intermediate assumptions).

Table 2. Projected Operations of the Social Security Trust Funds, 2018-2033

($ in billions)

|

Yeara |

Noninterest Incomeb |

Cost |

Cash Flow Deficit |

|

2018 |

|

1, |

( |

|

2019 |

|

1, |

( |

|

2020 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2021 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2022 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2023 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2024 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2025 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2026 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2027 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2028 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2029 |

1, |

1, |

( |

|

2030 |

1, |

2, |

( |

|

2031 |

1, |

2, |

( |

|

2032 |

1, |

2, |

( |

|

2033 |

1, |

2, |

( |

Source: Table prepared by CRS from data provided in Table VI.G8 (intermediate assumptions), Supplemental Single-Year Tables Consistent with the 20182019 Annual Report, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/tr/20182019/lr6g8.html.

a. Projections for years after 20332034 are not shown because the asset reserves held by the Social Security trust funds are projected to be depleted in 20342035 under the intermediate assumptions.

b. Noninterest income is equal to total income minus interest income.

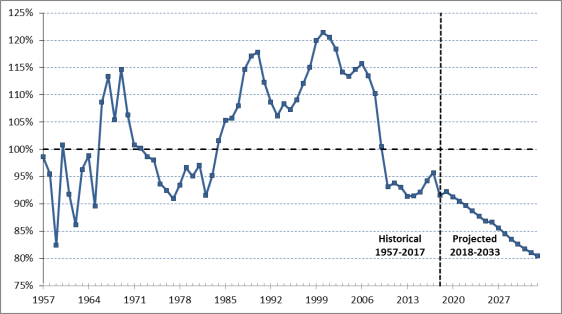

One way to measure the cash flow operations of the trust funds is to take the ratio of noninterest income to cost for each year. A ratio greater than 100% indicates positive cash flow (a cash flow surplus); a ratio less than 100% indicates negative cash flow (a cash flow deficit). Figure 1 shows the ratio of current noninterest income to current cost for the Social Security trust funds each year over the historical period 1957 to 20172018 and over the 2018 to 20332019 to 2034 period, as projected by the trustees in the 20182019 Annual Report (under the intermediate assumptions).25

As shown in the figure, in 2009, noninterest income of $689.2 billion divided by a cost of $685.8 billion results in a ratio just over 100% (100.5%), indicating a cash flow surplus for the Social Security trust funds that year. By comparison, in 20172018, noninterest income of $911.5920.1 billion divided by a cost of $952.51,000.2 billion results in a ratio of 95.6%, indicating a cash flow deficit. In the 2018 Annual Report, the Social Security trustees project that the ratio of current noninterest income to current cost will remain below 100% for the 75-year projection period (2018-2092), with the gap between noninterest income and cost increasing over time (under the intermediate assumptions).

|

Figure 1. Ratio of Current Noninterest Income to Cost for the Social Security Trust Funds, 1957- |

|

|

Source: Figure prepared by CRS from data provided in the Notes: Noninterest income excludes interest on accumulated holdings of U.S. government obligations. A ratio above 100% indicates a cash flow surplus for the year. A ratio below 100% indicates a cash flow deficit. |

In the 2019 Annual Report, the Social Security trustees project that the ratio of current noninterest income to current cost will remain below 100% for the 75-year projection period (2019-2093), with the gap between noninterest income and cost increasing over time (under the intermediate assumptions).

Investment of the Social Security Trust Funds

The Secretary of the Treasury is required by law to invest Social Security revenues in securities backed by the U.S. government.26 In addition, the Social Security trust funds receive interest on its holdings of special U.S. government obligations. Each U.S. government security issued by the U.S. Treasury for purchase by the Social Security trust funds must be a paper instrument in the form of a bond, note, or certificate of indebtedness.27 Specifically, Section 201(d) of the Social Security Act states,

Each obligation issued for purchase by the Trust Funds under this subsection shall be evidenced by a paper instrument in the form of a bond, note, or certificate of indebtedness issued by the Secretary of the Treasury setting forth the principal amount, date of maturity, and interest rate of the obligation, and stating on its face that the obligation shall be incontestable in the hands of the Trust Fund to which it is issued, that the obligation is supported by the full faith and credit of the United States, and that the United States is pledged to the payment of the obligation with respect to both principal and interest. The Managing Trustee may purchase other interest-bearing obligations of the United States or obligations guaranteed as to both principal and interest by the United States, on original issue or at the market price, only where he determines that the purchase of such other obligations is in the public interest.

Any interest or proceeds from the sale of U.S. government securities held by the Social Security trust funds must be paid in the form of paper checks from the General Fund of the Treasury to the Social Security trust funds.28 The interest rates paid on the securities issued to the Social Security trust funds are tied to market rates.

For internal federal accounting purposes, when special U.S. government obligations are purchased by the Social Security trust funds, the U.S. Treasury is shifting surplus Social Security revenues from one government account (the Social Security trust funds) to another government account (the General Fund). The special U.S. government obligations are physical documents held by SSA, not the U.S. Treasury. The securities held by the Social Security trust funds are redeemed on a regular basis. These special U.S. government obligations, however, are not resources for the federal government because they represent both an asset and a liability for the government.29

Off-Budget Status of the Social Security Trust Funds

For federal budget purposes, on-budget status generally refers to programs that are included in the annual congressional budget process, whereas off-budget status generally refers to programs that are not included in the annual congressional budget process.

Social Security is a federal government program that, like the Postal Service, has had its receipts and (most) outlays designated by law as off budget. The off-budget designation, however, has no practical effect on program funding, spending, or operations. The annual congressional budget resolution, in its legislative language, separates the off-budget totals (receipts and outlays) from the on-budget totals (receipts and outlays). The report language accompanying the congressional budget resolution usually shows the unified budget totals (which combine the on- and off-budget amounts) as well as the separate on- and off-budget totals. The President's budget tends to use the unified budget measures in discussing the budget totals. The President's budget documents also include the totals for the on- and off-budget components, as required by law. The Congressional Budget Office uses the unified budget numbers in its analyses of the budget; it generally does not include on- and off-budget data in its regular annual reports.

The unified budget framework is important because it includes all federal receipts and outlays, providing a more comprehensive picture of the size of the federal government, as well as the impact of and the federal budget's impact on the economy. In the unified budget, the Social Security program is a large source of both federal receipts (35.2% in FY2017FY2018) and federal outlays (25.1% in FY2017FY2018).30 For purposes of the unified budget, the annual Social Security cash flow surplus or deficit is counted in determining the overall federal budget surplus or deficit.31

The Social Security Trust Funds as Accumulated Holdings

The Social Security trust funds can be viewed as trust funds, similar to any private trust funds, that are to be used for paying current and future benefits (and administrative expenses). By law, the Social Security revenues credited to the trust funds (within the U.S. Treasury) are invested in non-marketable U.S. government obligations. These obligations are physical (paper) documents issued to the trust funds and held by SSA. When the obligations are redeemed, the U.S. Treasury must issue a check (a physical document) to the Social Security trust funds for the interest earned on the obligations.32

Unlike a private trust that may hold a variety of assets and obligations of different borrowers, the Social Security trust funds can hold only U.S. government obligations. The sale of these obligations by the U.S. government to the Social Security trust funds is federal government borrowing (from itself) and counts against the federal debt limit. The requirement that the Social Security trust funds purchase U.S. government obligations serves several purposes, such as

- offering a mechanism for the Social Security program to recoup the surplus revenues loaned to the rest of the government;

- paying interest so that the loan of the surplus revenues does not lose value over time;

- ensuring that the Social Security trust funds (and not other government accounts) receives credit for the interest earnings;

- ensuring a level of return (interest) to the Social Security trust funds; and

- providing a means outside of the securities market for the U.S. government to borrow funds.

The accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds represent the sum of annual surplus Social Security revenues (for all past years) that were invested in U.S. government obligations, plus the interest earned on those obligations. As a result of surplus Social Security revenues from 1984 to 2009 and the interest income credited to the Social Security trust funds, the accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds totaled about $2.9 trillion at the end of calendar year 20172018.33 It is the accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds (or the trust fund balance) that many people refer to when discussing the Social Security trust funds. Table 3 shows the accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds for the historical period 1957 to 20172018. Table 4 shows the projected accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds for the 2018 to 20332019 to 2034 period, as projected by the Social Security trustees in the 20182019 Annual Report (under the intermediate assumptions). The Social Security trustees project that in 20182020 the program's total cost will exceed its total income. Under intermediate assumptions, this relationship is projected to continue until the trust funds are depleted in 2034.

The Social Security trustees project that, on average over the next 75 years (2018 to 20922019 to 2093), program costs will exceed income by an amount equal to 2.8478% of taxable payroll (on average, costs are projected to exceed income by at least 20%).34 The gap between income and costs, however, is projected to increase over the 75-year period. For example, in 20342035, the cost of the program is projected to exceed income by an amount equal to 3.8715% of taxable payroll (costs are projected to exceed income by about 2319%). By 20912093, the cost of the program is projected to exceed income by an amount equal to 4.3211% of taxable payroll (costs are projected to exceed income by about 2524%).35

For illustration purposes, the trustees project that the Social Security trust funds would remain solvent throughout the 75-year projection period if, for example,

- revenues were increased by an amount equivalent to an immediate and permanent payroll tax rate increase of 2.

7870 percentage points (from 12.40% to 15.1810%; a relative increase of2221.8%);36 or

- benefits scheduled under current law were reduced by an amount equivalent to an immediate and permanent reduction of (1) about 17% if applied to all current and future beneficiaries, or (2) about

2120% if applied only to those who become eligible for benefits in20182019 or later; or - some combination of these approaches were adopted.37

Table 3. Accumulated Holdings of the

Social Security Trust Funds, Historical Period 1957-2017

($ in billions)

|

Year |

Accumulated |

Year |

Accumulated |

|

1957 |

$23.0 |

1988 |

109.8 |

|

1958 |

23.2 |

1989 |

163.0 |

|

1959 |

22.0 |

1990 |

225.3 |

|

1960 |

22.6 |

1991 |

280.7 |

|

1961 |

22.2 |

1992 |

331.5 |

|

1962 |

20.7 |

1993 |

378.3 |

|

1963 |

20.7 |

1994 |

436.4 |

|

1964 |

21.2 |

1995 |

496.1 |

|

1965 |

19.8 |

1996 |

567.0 |

|

1966 |

22.3 |

1997 |

655.5 |

|

1967 |

26.3 |

1998 |

762.5 |

|

1968 |

28.7 |

1999 |

896.1 |

|

1969 |

34.2 |

2000 |

1,049.4 |

|

1970 |

38.1 |

2001 |

1,212.5 |

|

1971 |

40.4 |

2002 |

1,378.0 |

|

1972 |

42.8 |

2003 |

1,530.8 |

|

1973 |

44.4 |

2004 |

1,686.8 |

|

1974 |

45.9 |

2005 |

1,858.7 |

|

1975 |

44.3 |

2006 |

2,048.1 |

|

1976 |

41.1 |

2007 |

2,238.5 |

|

1977 |

35.9 |

2008 |

2,418.7 |

|

1978 |

31.7 |

2009 |

2,540.3 |

|

1979 |

30.3 |

2010 |

2,609.0 |

|

1980 |

26.5 |

2011 |

2,677.9 |

|

1981 |

24.5 |

2012 |

2,732.3 |

|

1982 |

24.8 |

2013 |

2,764.4 |

|

1983 |

24.9 |

2014 |

2,789.5 |

|

1984 |

31.1 |

2015 |

2,812.5 |

|

1985 |

42.2 |

2016 |

2,847.7 |

|

1986 |

46.9 |

2017 |

2,891 .7 |

|

1987 |

68.8 |

2018 |

2,894.9 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS from data provided in the 20182019 Annual Report, Table VI.A3, pp. 160-161159-160, at https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2018/tr20182019/tr2019.pdf. Accumulated holdings are end-of-year totals.

a. The accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds are also referred to as the trust fund balance.

Table 4. Projected Accumulated Holdings of the

Social Security Trust Funds, 2018-2033

($ in billions)

|

Yeara |

Accumulated |

Yeara |

Accumulated |

|

2018 |

$2, |

2026 |

$2, |

|

2019 |

2, |

2027 |

2, |

|

2020 |

2, |

2028 |

1, |

|

2021 |

2, |

2029 |

1, |

|

2022 |

2, |

2030 |

1, |

|

2023 |

2, |

2031 |

1, |

|

2024 |

2, |

2032 |

777.3 |

|

2025 |

2, |

2033 |

348.5 |

Source: Table prepared by CRS from data provided in Table VI.G8 (intermediate assumptions), Supplemental Single-Year Tables Consistent with the 20182019 Annual Report, at https://www.ssa.gov/oact/tr/20182019/lr6g8.html.

a. Projections for years after 20332034 are not shown because the asset reserves held by the Social Security trust funds are projected to be depleted in 20342035 under the intermediate assumptions.

b. The accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds are also referred to as the trust fund balance.

The Social Security Trust Funds and the Level of Federal Debt

As part of the annual congressional budget process, the level of federal debt (the federal debt limit) is established for the budget by Congress. The federal debt limit includes debt held by the public, as well as the internal debt of the U.S. government (i.e., debt held by government accounts). Borrowing from the public and the investment of the Social Security trust funds in special U.S. government obligations both fall under the restrictions of the federal debt limit. This means that the balance of the Social Security trust funds has implications for the federal debt limit.38

The Social Security Trust Funds and Benefit Payments

The accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds represent funds designated to pay current and future benefits. When current Social Security tax revenues fall below the level needed to pay benefits, however, these funds become available only as the federal government raises the resources needed to redeem the securities held by the trust funds. The securities are a promise by the federal government to raise the necessary funds.39 In past years, when Social Security was operating with annual cash flow surpluses, Social Security's surplus revenues were invested in U.S. government securities and used at the time to pay for other federal government activities. Social Security's past surplus revenues, therefore, are not available to finance benefits directly when Social Security is operating with annual cash flow deficits, as it does today.40 The securities held by the trust funds must be redeemed for Social Security benefits to be paid.

Stated another way, when Social Security is operating with a cash flow deficit, the program relies in part on the accumulated holdings of the trust funds to pay benefits and administrative expenses. Because the trust funds hold U.S. government securities that are redeemed with general revenues, there is increased reliance on the General Fund of the Treasury. With respect to reliance on the General Fund when Social Security is operating with a cash flow deficit, it is important to note that Social Security does not have authority to borrow from the General Fund. Social Security cannot simply draw upon general revenues to make up for any current funding shortfall. Rather, Social Security relies on revenues that were collected for the program in previous years and used by the federal government at the time for other (non-Social Security) spending needs, plus the interest earned on its trust fund investments. Social Security draws on its own previously collected tax revenues and interest income (accumulated trust fund holdings) when current Social Security tax revenues fall below current program expenditures.

As the trustees point out, over the program's history, Social Security has collected approximately $2021.9 trillion and paid out $1819.0 trillion, leaving asset reserves of $2.9 trillion at the end of 20172018.41 The accumulated trust fund holdings of $2.9 trillion represent the amount of money that the General Fund of the Treasury owes to the Social Security trust funds. The General Fund could be said to have fully paid back the Social Security trust funds if the trust fund balance were to reach zero (i.e., if all of the trust funds' asset reserves were depleted).

The trustees project that the asset reserves held by the Social Security trust funds will be depleted in 20342035. At that point, the program will continue to operate with incoming receipts to the trust funds. Incoming receipts are projected to be sufficient to pay about three-fourths80% of scheduled benefits through the end of the projection period in 20922093 (under the intermediate assumptions of the 20182019 Annual Report).42 Title II of the Social Security Act, which governs the program, does not specify what would happen to the payment of benefits in the event that the trust funds' asset reserves are depleted and incoming receipts to the trust funds are not sufficient to pay scheduled benefits in full and on time. Two possible scenarios are (1) the payment of full monthly benefits on a delayed basis or (2) the payment of partial monthly benefits on time.

Appendix. Projected Trust Fund Dates, 1983-2018

2019

The following table shows the key dates projected for the Social Security trust funds by the Social Security Board of Trustees (based on their intermediate set of assumptions) in each of their annual reports from 1983 to 20182019.

Table A-1.Key Dates Projected for the Social Security Trust Funds as Shown Under the Intermediate Assumptions in Trustees Reports from 1983 to 2018

|

Year of Report |

Year of Reserve Depletion |

First Year That Cost Exceeds Noninterest Income |

First Year That Cost Exceeds Total Income |

||||||

|

OASI |

DI |

OASDI |

OASI |

DI |

OASDI |

OASI |

DI |

OASDI |

|

|

Intermediate II-B Projectionsa |

|||||||||

|

1983 |

2021 |

2047 |

|||||||

|

1984 |

2050 |

2021 |

2012 |

2021 |

2045 |

2038 |

2044 |

||

|

1985 |

2050 |

2034 |

2049 |

2019 |

2010 |

2019 |

2032 |

2020 |

2032 |

|

1986 |

2054 |

2026 |

2051 |

2020 |

2009 |

2019 |

2035 |

2017 |

2033 |

|

1987 |

2055 |

2023 |

2051 |

2020 |

2008 |

2019 |

2036 |

2013 |

2033 |

|

1988 |

2050 |

2027 |

2048 |

2019 |

2009 |

2019 |

2033 |

2016 |

2032 |

|

1989 |

2049 |

2025 |

2046 |

2019 |

2009 |

2018 |

2032 |

2014 |

2030 |

|

1990 |

2046 |

2020 |

2043 |

2019 |

2008 |

2017 |

2030 |

2011 |

2028 |

|

Intermediate Projections |

|||||||||

|

1991 |

2045 |

2015 |

2041 |

2018 |

1998 |

2017 |

2030 |

2011 |

2028 |

|

1992 |

2042 |

1997 |

2036 |

2018 |

1992 |

2016 |

2028 |

1992 |

2024 |

|

1993 |

2044 |

1995 |

2036 |

2019 |

1993 |

2017 |

2030 |

1993 |

2025 |

|

1994 |

2036 |

1995 |

2029 |

2016 |

1994 |

2013 |

2024 |

1994 |

2019 |

|

1995 |

2031 |

2016 |

2030 |

2014 |

2003 |

2013 |

2021 |

2007 |

2020 |

|

1996 |

2031 |

2015 |

2029 |

2014 |

2003 |

2012 |

2021 |

2007 |

2019 |

|

1997 |

2031 |

2015 |

2029 |

2014 |

2004 |

2012 |

2021 |

2007 |

2019 |

|

1998 |

2034 |

2019 |

2032 |

2015 |

2006 |

2013 |

2023 |

2009 |

2021 |

|

1999 |

2036 |

2020 |

2034 |

2015 |

2006 |

2014 |

2024 |

2009 |

2022 |

|

2000 |

2039 |

2023 |

2037 |

2016 |

2007 |

2015 |

2026 |

2012 |

2025 |

|

2001 |

2040 |

2026 |

2038 |

2016 |

2008 |

2016 |

2027 |

2015 |

2027 |

|

2002 |

2043 |

2028 |

2041 |

2018 |

2009 |

2017 |

2028 |

2018 |

2027 |

|

2003 |

2044 |

2028 |

2042 |

2018 |

2008 |

2018 |

2030 |

2018 |

2028 |

|

2004 |

2044 |

2029 |

2042 |

2018 |

2008 |

2018 |

2029 |

2017 |

2028 |

|

2005 |

2043 |

2027 |

2041 |

2018 |

2005 |

2017 |

2028 |

2014 |

2027 |

|

2006 |

2042 |

2025 |

2040 |

2018 |

2005 |

2017 |

2028 |

2013 |

2027 |

|

2007 |

2042 |

2026 |

2041 |

2018 |

2005 |

2017 |

2028 |

2013 |

2027 |

|

2008 |

2042 |

2025 |

2041 |

2018 |

2005 |

2017 |

2028 |

2012 |

2027 |

|

2009 |

2039 |

2020 |

2037 |

2017 |

2005 |

2016 |

2025 |

2009 |

2024 |

|

2010 |

2040 |

2018 |

2037 |

2018 |

2005 |

2015 |

2026 |

2009 |

2025 |

|

2011 |

2038 |

2018 |

2036 |

2017 |

2005 |

2010 |

2025 |

2009 |

2023 |

|

2012 |

2035 |

2016 |

2033 |

2010 |

2005 |

2010 |

2023 |

2009 |

2021 |

|

2013 |

2035 |

2016 |

2033 |

2010 |

2005 |

2010 |

2022 |

2009 |

2021 |

|

2014 |

2034 |

2016 |

2033 |

2010 |

2005 |

2010 |

2022 |

2009 |

2020 |

|

2015 |

2035 |

2016 |

2034 |

2010 |

2005 |

2010 |

2022 |

2009 |

2020 |

|

2016 |

2035 |

2023 |

2034 |

2010 |

2019 |

2010 |

2022 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

2017 |

2035 |

2028 |

2034 |

2010 |

2019 |

2010 |

2022 |

2019 |

2022 |

|

2018 |

2034 |

2032 |

2034 |

2010 |

2019 |

2010 |

2018 |

2019 |

2018 |

|

2019 |

2034 |

2052 |

2035 |

2010 |

2036 |

2010 |

2020 |

2041 |

2020 |

Source: CRS, based on data from the 1983 to 20182019 Social Security trustees reports and information provided by SSA.

a. From 1983 to 1990, two intermediate forecasts were prepared (II-A and II-B). The intermediate II-B forecast corresponds more closely to the intermediate forecast in subsequent years.

b. Trust fund expected to remain solvent throughout the long-range projection period.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The original report was written by former CRS analyst [author name scrubbed]Christine Scott.

Footnotes

| 1. |

A person may receive retired-worker benefits and continue to have earnings from work. If a person is below the full retirement age and has earnings above a specified amount, benefits are withheld in part or in full under the Retirement Earnings Test. For more information, see Social Security Administration (SSA), Social Security: How Work Affects Your Benefits, Publication No. 05-10069, January 2018, at https://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-10069.pdf. |

| 2. |

SSA, Monthly Statistical Snapshot, |

| 3. |

SSA, Trust Fund FAQs, at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/ProgData/fundFAQ.html. |

| 4. |

Social Security Act, Title II, §201(d) |

| 5. |

The limit on wages and net self-employment income subject to the Social Security payroll tax (the taxable wage base) is adjusted annually based on average wage growth if a Social Security cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) is payable. For more information on the COLA, see CRS Report 94-803, Social Security: Cost-of-Living Adjustments. The Medicare Hospital Insurance component of the FICA/SECA tax is levied on total earnings. In addition, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) imposes an additional 0.9% tax on high-income workers with wages and self-employment income over $200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for joint filers effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2012. For more information on Medicare, see CRS Report R43122, Medicare Financial Status: In Brief. |

| 6. |

Self-employed individuals are required to pay Social Security payroll taxes if they have annual net earnings of $400 or more. Only 92.35% of net self-employment income (up to the annual limit) is taxable. |

| 7. |

SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, Financial Data |

| 8. |

The taxes associated with including Social Security benefits in federal taxable income go to the Social Security trust funds and Medicare's Hospital Insurance trust fund. For more information, see CRS Report RL32552, Social Security: Calculation and History of Taxing Benefits. |

| 9. |

The Social Security trust funds receive reimbursements from the General Fund for (1) the cost of noncontributory wage credits for military service before 1957; (2) the cost in 1971-1982 of deemed wage credits for military service performed after 1956; (3) the cost of benefits to certain uninsured persons who attained the age of 72 before 1968; (4) the cost of payroll tax credits provided to employees in 1984 and self-employed persons in 1984-89 by P.L. 98-21; (5) the cost in 2009-2013 of excluding certain self-employment earnings from SECA taxes under P.L. 110-246; and (6) payroll tax revenue forgone under the provisions of P.L. 111-147, P.L. 111-312, P.L. 112-78, and P.L. 112-96. See SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, Trust Fund Data, at http://www.socialsecurity.gov/OACT/STATS/table4a3.html. |

| 10. |

The total also includes a small amount of gifts to the trust funds. |

| 11. |

SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, Financial Data For A Selected Time Period, at https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/ProgData/allOps.html. |

| 12. |

For more information, see CRS Report R41328, Federal Trust Funds and the Budget. |

| 13. |

Social Security Act, Title II, §201 |

| 14. |

In addition, a portion of the federal income taxes paid on Social Security benefits, reimbursements from the General Fund, and the interest income on Social Security trust fund investments are credited to the Social Security trust funds. |

| 15. |

Social Security Act, Title II, §201(b) |

| 16. |

Before the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, the share of the payroll tax allocated to the DI fund was last changed (to 1.8%) in 2000, under a reallocation schedule established under the Social Security Domestic Employment Reform Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-387). For more information on past legislative changes to the allocation of payroll taxes between the OASI and DI trust funds, see CRS Report R43318, The Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund: Background and Current Status. |

| 17. |

The accumulated holdings of the Social Security trust funds in U.S. government obligations are also referred to as the Social Security trust fund balance. |

| 18. |

Certain government projects may be given "budget authority until expended," which allows the authority to spend funds on the project to be carried over each year until all of the authority to spend funds has been exhausted. |

| 19. |

The Social Security Amendments of 1983 (P.L. 98-21) made a number of program changes, including the coverage of federal workers, an increase in the full retirement age, and the taxation of Social Security benefits. For more information on the 1983 amendments, see CRS Report RL30920, Social Security: Major Decisions in the House and Senate Since 1935. |

| 20. |

The Social Security Board of Trustees is composed of three officers of the President's Cabinet (the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Labor, and the Secretary of Health and Human Services); the Commissioner of Social Security; and two public representatives who are appointed by the President and subject to confirmation by the Senate. (The two public trustee positions are currently vacant.) The Board of Trustees issues an annual report to Congress on the financial status of the Social Security trust funds. The trustees make three sets of projections based on low-cost, intermediate, and high-cost assumptions reflecting the uncertainty surrounding projections for a 75-year period. The trust fund projections cited in this CRS report are based on the intermediate (or "best estimate") assumptions of the |

| 21. |

Taxable payroll refers to total earnings in the economy that are subject to Social Security payroll taxes (with some adjustments). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the trust funds will have asset reserves until 2031, and that the program's 75-year actuarial shortfall would be equal to 4.4% of taxable payroll. See CBO, The 2018 Long-Term Budget Outlook, June 26, 2018, pp. 17, at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/ |

| 22. |

Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees, Status of the Social Security and Medicare Programs: A Summary of the |

| 23. |

Ibid. |

| 24. |

The Social Security Amendments of 1956 established the DI Trust Fund on August 1, 1956, and DI became effective on January 1, 1957. The historical table begins with 1957, the first year for which operations of the combined OASDI Trust Fund can be shown. |

| 25. |

|

| 26. |

Social Security Act, Title II, §201(d) |

| 27. |

Social Security Act, Title II, §201(d) |

| 28. |

Social Security Act, Title II, §201(f) |

| 29. |

For SSA's perspective on the U.S. government securities held by the trust funds, see SSA, Trust Fund FAQs, at http://www.ssa.gov/oact/progdata/fundFAQ.html. |

| 30. |

Percentages based on data from: U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, Tables 2.2 and 4.2. |

| 31. |

For related information, see David Pattison, "Social Security Trust Fund Cash Flows and Reserves," Social Security Bulletin, vol. 75, no. 1 (February 2015), at https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v75n1/v75n1p1.html. |

| 32. |

The funds are then used to purchase additional U.S. government securities credited to the Social Security trust funds. |

| 33. |

The Social Security trust funds also receive reimbursements from the General Fund of the Treasury for a variety of purposes. In 2011 and 2012, the trust funds received relatively large reimbursements from the General Fund ($102.7 billion and $114.3 billion, respectively). In those years, general revenues were credited to the trust funds to make up for forgone payroll tax revenues under a temporary two-percentage-point reduction in the payroll tax rate for employees. |

| 34. |

Program costs and income are evaluated as a percentage of taxable payroll because Social Security payroll taxes are the primary source of funding for the program. |

| 35. |

The 75-year "open group unfunded obligation" for Social Security is $13. |

| 36. |

The Social Security trustees explain that the projected increase in the payroll tax rate needed for the trust funds to remain solvent throughout the 75-year projection period (2. |

| 37. |

Ibid. |

| 38. |

For a discussion of how reaching the debt limit potentially could affect Social Security trust fund investment practices and benefit payments, see CRS Report R41633, Reaching the Debt Limit: Background and Potential Effects on Government Operations. |

| 39. |

If there are no surplus governmental receipts, the U.S. government may raise the necessary funds by increasing taxes or other income, reducing non-Social Security spending, borrowing from the public (i.e., replacing bonds held by the trust funds with bonds held by the public), or a combination of these measures. |

| 40. |

Social Security has been operating with annual cash flow deficits since 2010, and the trustees project that cash flow deficits will continue each year throughout the 75-year projection period ( |

| 41. |

Summary of the |

| 42. |

Projections show that incoming receipts would be sufficient to pay |