Health Insurance Exchanges and Qualified Health Plans: Overview and Policy Updates

Changes from June 20, 2018 to February 16, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Types of Exchanges

- Individual and SHOP Exchanges

- State-Based and Federally Facilitated Exchanges

- Facilitating Purchase of Coverage

- Individual Exchanges

- Eligibility and Enrollment Process

- Enrollment Periods and Enrollment Estimates

- Premium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Reductions

- SHOP Exchanges

- Eligibility and Enrollment Process

- Changes in SHOP Exchange Web Portal Functionality

- Enrollment Periods and Enrollment Estimates

- Small Business Health Care Tax Credit

- Individual and SHOP Exchange Enrollment Assistance

- Administering the Exchanges

- Qualified Health Plans

- Types of QHPs and Other Plans Offered Through Exchanges

- Exchange Funding

- Further Reading

Tables

Summary

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) requires health insurance exchanges to be established in every state. Exchanges are marketplaces in which consumers and small businesses can shop for and purchase private health insurance coverage. In general, states must have two types of exchanges: an individual exchange and a small business health options program (SHOP) exchange.

Exchanges may be established either by the state itself as a state-based exchange (SBE) or by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) as a federally facilitated exchange (FFE). Some states have SBE-FPs: they have SBEs but use the federal information technology platform, including the federal exchange website www.Healthcare.gov. In states with FFEs, the exchange may be operated by the federal government alone or in conjunction with the state. States may have different structures for their individual and SHOP exchanges.

Consumers who obtain coverage through the individual exchange may be eligible for financial assistance from the federal government. Financial assistance in the individual exchanges is available in two forms: Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

February 16, 2021

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) required health insurance exchanges to be established in every state. Exchanges are

Vanessa C. Forsberg

virtual marketplaces in which consumers and smal business owners and employees can

Analyst in Health Care

shop for and purchase private health insurance coverage and, where applicable, be

Financing

connected to public health insurance programs (e.g., Medicaid). In general, states must

have two types of exchanges: an individual exchange and a small business health

options program (SHOP) exchange. Exchanges may be established either by the state itself as a state-based exchange (SBE) or by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) as a federally facilitated exchange (FFE). Some states have SBE-FPs: they have SBEs but use the federal information

technology platform (FP), including the federal exchange website www.HealthCare.gov.

A primary function of the exchanges is to facilitate enrollment. This general y includes operating a web portal that

al ows for the comparison and purchase of coverage; making determinations of eligibility for coverage and financial assistance; and offering different forms of enrollment assistance, including Navigators and a cal center. Exchanges also are responsible for several administrative functions, including certifying the plans that wil be

offered in their marketplaces.

The ACA general y requires that the private health insurance plans offered through an exchange are qualified health plans (QHPs). To be a certified as a QHP, a plan must be offered by a state-licensed health insurance issuer and must meet specified requirements, including covering the essential health benefits (EHB). QHPs sold in the individual and SHOP exchanges must comply with the same state and federal requirements that apply to QHPs

and other health plans offered outside of the exchanges in the individual and smal -group markets, respectively. Additional requirements apply only to QHPs sold in the exchanges. Exchanges also may offer variations of QHPs,

such as child-only or catastrophic plans, and non-QHP dental-only plans.

Individuals and smal businesses must meet certain eligibility criteria to purchase coverage through the individual and SHOP exchanges, respectively. There is an annual open enrollment period during which any eligible consumer may purchase coverage via the individual exchanges; otherwise, consumers may purchase coverage only if they qualify for a special enrollment period. In general, smal businesses may enroll at any time during the year. There are plans available in al individual exchanges, and, as of February 2020, about 10.7 mil ion people

obtained health insurance through the individual exchanges. (2021 open enrollment data for al states are expected in spring 2021.) Nationwide SHOP exchange enrollment estimates are not regularly released; in addition, there are

no SHOP exchange plans available in more than half of states in 2021.

Plans sold through the exchanges, like private health insurance plans sold off the exchanges, have premiums and out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. Consumers who obtain coverage through the individual exchange may be eligible for federal financial assistance with premiums and OOP costs in the form of premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions. Small reductions. Smal businesses that use the SHOP exchange may be eligible for small business health insurance tax credits. The tax credits assist small businesses

credits that assist with the cost of providing health insurance coverage to employees.

The ACA generally requires that health insurance plans offered through an exchange are qualified health plans (QHPs). To be a certified as a QHP, a plan must be offered by a state-licensed issuer and must meet specified requirements, including covering the essential health benefits (EHB). QHPs sold in

The federal government spent an estimated $1.8 bil ion on the operation of exchanges in FY2020, and it projected $1.2 bil ion in spending for FY2021. Much of the federal spending on the exchanges is funded by user fees paid by the insurers who participate in FFE and SBE-FP exchanges. States with SBEs finance their own exchange

administration; states with SBE-FPs also finance certain costs (e.g., consumer outreach and assistance programs,

including Navigator programs).

This report provides an overview of the various components of the health insurance exchanges. It begins with summary information about the types of exchanges and their administration. Sections on the individual and SHOP exchanges discuss eligibility and enrollment, plan costs and financial assistance available to eligible consumers and smal businesses, insurer participation, and other topics. The final sections address types of enrollment assistance available to exchange consumers and federal funding for the exchanges.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 21 link to page 23 link to page 23 link to page 24 link to page 24 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 30 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 31 link to page 33 link to page 33 link to page 9 link to page 21 link to page 32 link to page 32 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 2

Types and Administration of Exchanges ........................................................................ 2

Individual and SHOP Exchanges ............................................................................ 2 State-Based and Federal y Facilitated Exchanges ...................................................... 3 Exchange Administration....................................................................................... 5

Qualified Health Plans................................................................................................ 6

Individual Exchanges ...................................................................................................... 7

Eligibility and Enrollment ........................................................................................... 7

Interaction with Medicaid, CHIP, and Medicare ........................................................ 8

Open and Special Enrollment Periods ...................................................................... 8 Special Enrollment Periods and COVID-19 ............................................................ 10 Enrollment Estimates .......................................................................................... 11

Premiums and Cost Sharing ...................................................................................... 12

Premium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Reductions ................................................. 14

Insurer Participation................................................................................................. 17

SHOP Exchanges .......................................................................................................... 19

Eligibility and Enrollment ......................................................................................... 19

Enrollment Periods ............................................................................................. 20

Online Enrollment versus Direct Enrollment........................................................... 20 Enrollment Estimates .......................................................................................... 22 Congressional Member and Staff Enrollment via the D.C. SHOP Exchange ................ 22

Premiums and Cost Sharing ...................................................................................... 22

Smal Business Health Care Tax Credit .................................................................. 23

Insurer Participation................................................................................................. 24

Exchange Enrollment Assistance ..................................................................................... 24

Navigators and Other Exchange-Based Enrollment Assistance........................................ 24

Brokers, Agents, and Other Third-Party Assistance Entities ............................................ 26

Exchange Spending and Funding ..................................................................................... 26

Initial Grants for Exchange Planning and Establishment ................................................ 26 Ongoing Federal Spending on Exchange Operation....................................................... 27

Funding Sources for Federal Exchange Spending ......................................................... 27

User Fees Collected from Participating Insurers ...................................................... 27 Other Federal Funding Sources............................................................................. 29

State Financing of the Exchanges ............................................................................... 29

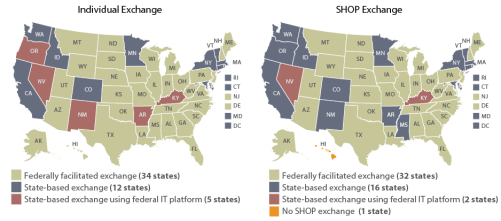

Figures Figure 1. Individual and SHOP Exchange Types by State, Plan Year 2021................................ 5 Figure 2. Plan Year 2021 Insurer Participation in the Individual Exchanges, by County............ 17 Figure 3. Federal User Fee for Insurers Participating in Specified Types of Individual

Exchanges, by Plan Year.............................................................................................. 28

Congressional Research Service

link to page 42 link to page 42 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 20 link to page 35 link to page 39 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 34 link to page 39 link to page 41 link to page 44 link to page 46 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Figure C-1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services “Health Insurance Exchanges

Transparency Table,” FY2021 ...................................................................................... 38

Tables Table 1. Open Enrollment Periods for Individual Exchanges on the Federal Platform, by

Plan Year .................................................................................................................... 9

Table 2. Nationwide Individual Exchange Enrollment Estimates, by Plan Year ....................... 12 Table 3. Annual Out-of-Pocket Limits, by Plan Year ........................................................... 14 Table 4. Data on Premiums, Advance Premium Tax Credits, and Cost-Sharing Reductions

Nationwide, by Plan Year ............................................................................................ 16

Table A-1. Exchange Types and Key Details by State, Plan Year 2021 ................................... 31 Table B-1. Types of Plans Offered Through the Exchanges .................................................. 35 Table C-1. CMS Federal Exchange Funding Sources for Specified Fiscal Years ...................... 39 Table D-1. HHS “Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters,” Final Rule by Year................. 40

Appendixes Appendix A. Exchange Information by State ..................................................................... 30 Appendix B. Types of Plans Offered Through the Exchanges ............................................... 35 Appendix C. Exchange Spending and Funding Details from CMS Budget Justifications .......... 37 Appendix D. Additional Resources .................................................................................. 40

Contacts

Author Information ....................................................................................................... 42

Congressional Research Service

link to page 16 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Introduction The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; exchanges must comply with the same state and federal requirements that apply to QHPs and other health plans offered outside of the exchanges in the individual and small-group markets, respectively. Exchanges also may offer variations of QHPs, such as child-only or catastrophic plans, and non-QHP dental-only plans.

This report provides an overview of the various components of the health insurance exchanges. It begins with summary information about how exchanges are structured and then discusses both individual and SHOP exchanges in terms of eligibility and enrollment, financial assistance for certain exchange consumers and small businesses, and enrollment assistance entities. The report also describes exchanges' role in certifying plans as qualified to be sold in their marketplaces and outlines the range of plans offered through exchanges. Finally, the report briefly addresses funding for the exchanges. Where applicable, the report references other CRS reports that have more information on various topics.

Introduction

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) requires required health insurance exchanges (also known as marketplaces) to be established in every state. ACA The ACA

exchanges are virtual marketplaces in which consumers and small smal businesses can shop for and purchase private health insurance coverage and, where applicable, be connected to public health insurance programs (e.g., Medicaid).1 1 Certain consumers and small employers are eligible for financial assistance for private health insurance purchased (only) through the exchanges. Exchanges are intended to simplify the experience of obtaining health insurance. They are not intended to supplant the private market outside of the exchanges but rather to provide an

additional source of private health insurance coverage options.

This report provides an overview of key aspects of the health insurance exchanges. The report includes summary information about the major functions of exchanges and how they are structured. It describes individual and small business eligibility and enrollment processes, provides enrollment estimates, explains the financial assistance available to certain consumers and small businesses, and discusses consumer enrollment assistance options. The report also reviews the role of exchanges in certifying participating plans and outlines the range of plans offered through exchanges. It briefly addresses funding for the exchanges. It provides a high-level description of these exchange-related topics while referencing other CRS reports with further information on specific topics, including on topics related to market stabilization policy considerations.

Types of Exchanges

The exchanges may be administered by state governments and/or the federal government.

Regardless, the major functions of the exchanges are (1) to facilitate consumers’ and smal businesses’ purchase of coverage (by operating a web portal, making determinations of eligibility for coverage and any financial assistance, and offering different forms of enrollment assistance) and (2) to certify, recertify, and otherwise monitor the plans that are offered in those

marketplaces.

Although a relatively smal proportion of people in the U.S. obtain their coverage through the exchanges,2 the administration and functioning of these marketplaces are ongoing topics of interest to congressional audiences and other stakeholders. An understanding of the exchanges

can provide context for current health policy discussions and proposals related to health care coverage and costs, the roles of the public and private sectors in the provision of health coverage,

and more.

This report provides an overview of key aspects of the health insurance exchanges. It begins with summary information about types and administration of exchanges and the plans sold in them. Sections on the individual and smal business exchanges discuss eligibility and enrollment, plan costs and financial assistance available to eligible consumers and smal businesses, insurer participation, and other topics. The final sections describe types of enrollment assistance available

to exchange consumers and provide information on federal funding for the exchanges.

Appendixes offer further details, including exchange types by state.

1 In this report, the terms consumers and individuals generally are used interchangeably, as are small businesses and sm all em ployers.

2 For example, as of February 2020, about 10.7 million people obtained health insurance through the individual exchanges. T his figure is approximately 3% of the current U.S. population of 330 million people. See Table 2 regarding exchange enrollment estimates and sources. For current U.S. population, see U.S. Census, “U.S. and World Population Clock,” accessed September 2, 2020, at https://www.census.gov/popclock/.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 18 link to page 27 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Overview

Types and Administration of Exchanges

Individual and SHOP Exchanges

The ACA Individual and SHOP Exchanges

The ACA required health insurance exchanges to be established in all al states and the District of Columbia (DC).Columbia.3 In general, the health insurance exchanges began operating in October 2013 to allow al ow

consumers to shop for health insurance plans that began as soon as January 1, 2014.

Most states have

There are two types of exchanges—an individual exchangeexchanges and a small business health options program (SHOP) exchange.2exchanges.4 These exchanges are part of the individual (also cal ed non-group) and smal -group segments of the private health insurance market, respectively.5 In an individual exchange, eligible consumers can compare and purchase non-group insurance for themselves and

their families and can apply for premium tax credits (PTCs) and cost-sharing reductions.3subsidies (see “Premium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Reductions,” below). In a SHOP exchange, small smal businesses can compare and purchase smallsmal -group insurance and can apply for small smal business health insurance tax credits (“Smal Business Health Care Tax Credit,” below); in addition, employees of small smal businesses can enroll in plans offered by their employers on a SHOP exchange.4 Besides facilitating consumers' and small businesses' purchase of coverage (by operating a web portal, making determinations of eligibility for coverage and any financial assistance, and offering different forms of enrollment assistance), the other major function of the exchanges is to certify, recertify, and otherwise monitor the plans that participate in those marketplaces. Individual and SHOP exchanges can be operated by either the state or the federal government, as described below.

exchange.

Each exchange covers a whole state.6 Within a given exchange, private insurers may offer plans that cover the whole state or only certain areas within the state (e.g., one or more counties). Plans

sold within a given exchange may cover services offered by providers located in more than one

state.

In general, consumers and smal businesses may obtain coverage within their state’s individual or SHOP exchange, respectively, or they may shop in the individual or smal -group health insurance markets outside of the exchanges, which existed prior to the ACA and continue to exist.7 Outside of the ACA exchanges, consumers can purchase coverage through agents or brokers, or they can purchase it directly from insurers. In addition, there were and stil are privately operated websites that al ow the comparison and purchase of coverage sold by different insurers, broadly similar in

concept to the ACA exchanges.8

3 T he Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) also gave the territories the option of establishing exchanges, but none elected to do so, by th e statutory deadline of October 1, 2013. See 42 U.S.C. §18043. 4 T he term individual exchange is used for purposes of this report. It is not defined in exchange-related statute or regulations.

5 T he private health insurance market includes both the group market (largely made up of employer-sponsored insurance) and the individual m arket (which includes plans directly purchased from an insurer). T he group market is divided into small- and large-group market segments; a sm all group is typically defined as a group of up to 50 individuals (e.g., employees), and a large group is typically defined as one with 51 or more individuals.

6 T here is an option for states to coordinate in administering regional exchanges or for a single state to establish subsidiary exchanges that serve geographically distinct areas (see 45 C.F.R. §155.410) , but none have done so. 7 However, plans are not available in all small business health options program (SHOP) exchanges in 2021. 8 An example of a privately owned website that allows for comparison and purchase of coverage from different insurers is ehealthinsurance.com. Note that some types of coverage sold outside of the federal and state exchanges, potentially including some types of coverage available on private sites like t his one, are not subject to some or all federal health insurance requirements. For more information, see CRS Report R46003, Applicability of Federal Requirem ents to Selected Health Coverage Arrangem ents.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 28 link to page 28 link to page 44 link to page 24 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

State-Based and Federally Facilitated Exchanges

State-Based and Federally Facilitated Exchanges

A state can choose to establish its own state-based exchange (SBE). If a state opts not to administer its own exchange, or if the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determines that the state is not in a position to do so, then HHS is required to establish and administer

the exchange in the state as a federally facilitated exchange (FFE). States also

There is one variation on the SBE approach: a state may have a state-based exchange using a federal platform (SBE-FP), which means they have an SBE but use the federally the state oversees the exchange but uses the federal y

facilitated information technology (IT) platform, or federal platform (FP) (i.e., HealthCare.gov).

There is also a variation on the FFE approach: a state may have a state partnership FFE, which al ows the state to manage certain aspects of its exchange while HHS manages the remaining aspects and has authority over the exchange. In early guidance on this option, HHS indicated a

state could elect to perform some plan management and/or certain consumer assistance functions, and HHS would perform other functions, including facilitating enrollment through the federal HealthCare.gov platform and funding Navigator entities in the state.9 In federal and private resources that track exchange data, this variation may not be reported on separately but rather

may be included in overal counts of FFEs, which is the model this report general y follows.10

In rulemaking finalized January 19, 2021 (the 2022 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters, or “Payment Notice”11), HHS and the Department of the Treasury established new “direct enrollment” variations of the exchange types: FFE-DE, SBE-DE, and SBE-FP-DE.12 States

electing these options would “adopt a private sector-based enrollment approach as an alternative to the consumer-facing enrollment website operated by the Exchange (for example, HealthCare.gov for the FFEs).” In other words, consumers would enroll in exchange plans via private agents or brokers, rather than on an exchange website like HealthCare.gov. The exchange would stil have to “make available a website listing basic [qualified health plan] QHP

information for comparison,” but this website would direct consumers to “approved partner websites for consumer shopping, plan selection, and enrollment activities.” Per the final rule, this wil be an option for SBEs as of plan year (PY) 2022, and for FFEs and SBE-FPs as of PY2023. The final rule was published but did not take effect before the presidential transition, and as such,

may be reconsidered by the Biden Administration.13

9 See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight (CCIIO), “General Guidance on Federally-facilitated Exchanges,” May 16, 2012, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/Downloads/ffe-guidance-05-16-2012.pdf. Also see CMS, CCIIO, “ Guidance on State Partnership Exchange,” January 3, 2013, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/Downloads/partnership-guidance-01-03-2013.pdf. For more information about Navigators, see “ Navigators and Other Exchange-Based Enrollment Assistance” in this report.

10 T his report focuses on the three types of exchanges that are commonly discussed in CMS resources, but other entities may also track states with variations of state partnership FFEs. For example, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) notes FFEs in which the state conducts plan management activities at “ State Health Insurance Marketplace T ypes, 2021,” at https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-health-insurance-marketplace-types/. 11 See 2022 Payment Notice, starting page 6143, regarding information in this paragraph. T he Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters, or Payment Notice, is an annually published rule that includes updates and policy changes related to the exchanges and private health insurance. See Table D-1 for Payment Notice citations.

12 For additional discussion of direct enrollment, see “ Online Enrollment versus Direct Enrollment” in the SHOP section of this report.

13 See Office of Management and Budget, “Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies,” 86 Federal Register 7424, January 28, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 9 link to page 35 link to page 35 link to page 24 link to page 28 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

For PY2021, 30 states have FFEs, 15 states have SBEs, and 6 states have SBE-FPs.14 A few states have changed approaches one or more times (e.g., initial y worked to create an SBE but then switched to an SBE-FP or FFE model). Changes in the first few years varied in terms of whether the state moved toward more or less federal involvement, but in several cases, a state transitioned from a fully state-based approach to an SBE-FP (i.e., transitioned toward more federal involvement). Recent and ongoing transitions are general y in the direction of less federal

involvement. As of the publication of this report, five states are transitioning or considering

transitions for PY2022 or beyond.15

SHOP exchanges may be federal y facilitated (FF-SHOP) or state-based (SB-SHOP).16 For PY2021, there are 32 FF-SHOPs and 18 SB-SHOPs. However, in more than half of these states, no insurers are offering medical plans in the SHOP exchange, meaning there is effectively no SHOP exchange there.17facilitated information technology (IT) platform (i.e., HealthCare.gov).

For the 2018 plan year, 34 states have FFEs, 12 states have SBEs, and 5 states have SBE-FPs.5 In addition, state involvement in the FFEs may vary. In many states with FFEs, the exchange is wholly operated and administered by HHS. But in some cases, states partner with HHS to perform some functions, such as plan management or consumer assistance.6

Like the individual exchanges, SHOP exchanges may be federally facilitated (FF-SHOP; 32 states), state-based (SB-SHOP; 16 states), or state-based using the federal IT platform (SB-FP-SHOP; 2 states).7 One state is exempted from operating a SHOP exchange.8 For the 2018 One state is exempted from operating a SHOP exchange.18 For the 2021 plan year, most states'’ individual and SHOP exchanges are administered in the same way (i.e., both state-based or both federallyfederal y facilitated). However, a handful of states have different

approaches for their individual and SHOP exchanges.

See Figure 1 andSome resources refer to this as a bifurcated

approach.

See Figure 1 for individual and SHOP exchange types by state in PY2021, and see Table A-1 for

additional information, including on state transitions to different exchange types.

14 See Table A-1 for details and citations for this paragraph. In tallies throughout this report, the District of Columbia is counted as a state.

15 One of these states, Georgia, received approval through the Section 1332 state innovation waiver process shift to its own Georgia Access Model, essentially a direct enrollment approach, beginning in PY2023. T his 1332 process allows states to waive specified ACA provisions, including provisions related to the establishment of health insurance exchanges and related activities. See CRS Report R44760, State Innovation Waivers: Frequently Asked Questions for more information.

16 As of June 2018, states can no longer select a state-based SHOP using the federal IT platform (SB-FP-SHOP) approach, except that the two states with that model at that time (Nevada and Kentucky) could maintain it. According to CMS, those states no longer use that model. For more information, see “ Online Enrollment versus Direct Enrollment in the SHOP section of this report.

17 See “Insurer Participation” in the SHOP Exchanges section of this report for more information. 18 Hawaii received a Section 1332 waiver exempting it from operating a SHOP exchange.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 35 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 28 link to page 10

Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Figure 1. Individual and SHOP Exchange Types by State, Plan Year 2021

Sources: Congressional Research Service (CRS) il ustration. See data sources in Table A-1. Notes: SHOP = smal for the exchange types by state.

|

|

|

Facilitating Purchase of Coverage

A primary function of the exchanges is to provide a way for consumers and small in this report regarding individual and SHOP exchanges, and federal and state administration of exchanges. In more than half of states, no insurers are offering medical plans in the SHOP exchange, meaning there is effectively no SHOP exchange there. These states have a circle symbol in the SHOP Exchange map above. See “Insurer Participation” in the SHOP Exchanges section of this report for more information. Hawai received a Section 1332 waiver exempting it from operating a SHOP exchange. For more information, see CRS Report R44760, State Innovation Waivers: Frequently Asked Questions.

Exchange Administration

Whether state-based or federal y facilitated, exchanges are required by law to fulfil certain minimum functions. ACA provisions related to the establishment and operation of the exchanges are codified at 42 U.S.C. §§18031 et seq. Other federal provisions also are relevant, for example

regarding the requirements for plans that may be sold through the exchanges.19

A primary function of the exchanges is to provide a way for consumers and smal businesses to compare and purchase health plan options offered by participating insurers.9

20 This general y includes operating a web portal that al ows for comparing and purchasing coverage, making

determinations of eligibility for coverage and financial assistance, and offering different forms of

enrollment assistance.

Exchanges also are responsible for several administrative functions, including certifying the plans that wil be offered in their marketplaces.21 This includes annual y certifying or recertifying plans to be sold in their exchanges as qualified health plans (QHPs, discussed below). QHP certification involves a review of various factors, including the plan’s benefits, cost-sharing structure, provider network, premiums, marketing practices, and quality improvement activities,

19 See “Qualified Health Plans” in this report. 20 42 U.S.C. §18031(b)(1)(A). 21 42 U.S.C. §18031(d)(4).

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 12 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

to ensure compliance with applicable federal and state standards.22 The QHP certification process is to be completed each year in time for insurers to market their plans and premiums during the

exchanges’ annual open enrollment period (see “Open and Special Enrollment Periods”).

Exchanges’ other administrative activities include collecting enrollment and other data, reporting data to and otherwise interacting with the Departments of HHS and the Treasury, and working

with state insurance departments and federal regulators to conduct ongoing oversight of plans.

Qualified Health Plans In general, health insurance plans offered through exchanges must be qualified health plans (QHPs).23 A QHP is a plan offered by a state-licensed insurer that is certified to be sold in that state’s exchange, covers the essential health benefits (EHB) package, and meets other specified

requirements.24 Covering the EHB package means covering 10 broad categories of benefits and services, complying with limits on consumer cost sharing on the EHB, and meeting certain

generosity requirements (in terms of actuarial value).25

QHPs are subject to the same state and federal requirements that apply to health plans offered outside of exchanges.26 Thus, a QHP offered through an individual exchange must comply with state and federal requirements applicable to individual market plans; a QHP offered through a SHOP exchange must comply with state and federal requirements applicable to smal -group market plans. For example, the requirement to cover the EHB applies to individual and smal -

group plans both in and out of the exchanges.

There are additional requirements that apply only to QHPs sold in the exchanges. For example, an insurer wanting to sel QHPs in an exchange must offer at least one silver-level and one gold-

level plan in al of the areas in which the insurer offers coverage within that exchange. In addition, QHPs must meet network adequacy standards, including maintaining provider networks that are “sufficient in number and types of providers” and include “essential community

providers.”27

A QHP is the only type of comprehensive health plan an exchange may offer, but QHPs may be offered outside of exchanges, as wel . Besides standard QHPs, other types of plans may be available in a given exchange, including child-only plans, catastrophic plans, consumer operated and oriented plans (CO-OPs), and multi-state plans (MSPs). Technical y, these are also QHPs.

22 42 U.S.C. §18031(c)(1); 42 U.S.C. §18031(e). For more information, see, for example, CMS, CCIIO, “ Final 2021 Letter to Issuers in the Federally-facilitated Exchanges,” May 7, 2020, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/Final-2021-Letter-to-Issuers-in-the-Federally-facilitated-Marketplaces.pdf. Hereinafter referred to as “CMS 2021 Letter to Issuers.” 23 42 U.S.C. §18031(d)(2)(B). 24 42 U.S.C. §18021(a)(1). 25 42 U.S.C. §18022. For brief explanation of actuarial value (AV) and cost -sharing limits, see “ Premiums and Cost Sharing” in this report. For more information on the essential health benefits, cost-sharing limits, and AV requirements, see CRS Report R45146, Federal Requirem ents on Private Health Insurance Plans. 26 For more information about federal requirements applicable to different types of plans, see CRS Report R45146, Federal Requirem ents on Private Health Insurance Plans. T his report also addresses states’ roles as the primary regulators of health insurance.

27 See, for example, 42 U.S.C. §§18021, 18023, and 18031; and 45 C.F.R. §§156.200 et seq. Also see the CMS 2021 Letter to Issuers. Network adequacy standards are at 45 C.F.R. §156.200. T he requirement regarding silver and gold plans is discussed in “ Premiums and Cost Sharing” in this report.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 9 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 28 link to page 28 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Stand-alone dental plans (SADPs) are the only non-QHPs offered in the exchanges. See Table B-

1 for more information.

Under federal law, insurers are not required to offer plans in the exchanges, just as they are not

required to offer plans in markets outside the exchanges. If an insurer does want to offer a plan in an exchange, it must meet applicable federal and state requirements, as discussed in this section and the prior one on “Exchange Administration.” Insurer participation in the individual and

SHOP exchanges is discussed in the sections below.

Individual Exchanges

Individual Exchanges

Eligibility and Enrollment Process

Consumers may purchase health insurance plans for themselves orand their families in their state's individual ’s individual exchange. Consumers may enroll as long as they (1) meet state residency requirements;1028 (2) are not incarcerated, except individuals in custody pending the disposition of charges; and (3) are U.S. citizens, U.S. nationals, or "“lawfully present"” residents.11 29

Undocumented individuals are prohibited from purchasing coverage through the exchanges, even

if they were to pay the entire premium without financial assistance.

Consumers can use their state'’s exchange website (Healthcare.gov or a state-run site) to compare and enroll in plans, and the exchange websites are required to display a calculator that estimates consumers' costs after any cost-sharing reductions or premium tax credits for which they are eligible (see "HealthCare.gov or a state-run site) to apply for

coverage and financial assistance and to compare and enroll in plans. The ACA requires exchanges to provide a “single, streamlined form” that consumers can use to apply for “al applicable State health subsidy programs within the State.”30 This means that through one form, consumers can be determined eligible for exchange financial assistance (see “Premium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Reductions"” in this report). Consumers may be linked to, as wel as Medicaid orand the State Children'

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment pages if they are eligible.

In addition to using the exchange websites, consumers can , as discussed below.31 The exchange website displays al exchange plans available to a consumer, with estimates of the consumer’s costs, including monthly premiums that reflect the application of any federal financial assistance for

which they are eligible.

In addition to using their exchange website, consumers can apply and enroll by phone, by mail, or in person, in person—including through an agent, broker, or plan issuer—as available by state. Enrollment assistance is available for those who want it (see "Individual and SHOP Exchange Enrollment Assistance" in this report).

Once the exchange receives and verifies consumers' eligibility and enrollment information, it may continue to serve as a conduit through which consumers pay their premiums to their issuers. Alternatively, consumers may pay premiums directly to their issuers.

Enrollment Periods and Enrollment Estimates

Consumers may enroll in coverage through the exchanges only during specified enrollment periods.

Anyone eligible for exchange plan coverage may enroll during an annual open enrollment period (OEP).12 The OEP typically takes place in fall e.g., through exchange Navigators or through agents or brokers; see “Exchange Enrollment

Assistance” in this report).

28 State residency may be established through a variety of means, including actual or planned residence in a state, actual or planned employment in a state, and other circumstances. See 45 C.F.R. §155.305.

29 U.S. citizens and U.S. nationals are eligible for coverage through the exchanges. Lawfully present immigrants are also eligible for coverage through the exchanges. Examples of lawfully present immigrants include those who have qualified non-citizen immigration status without a waiting period, humanitarian statuses or circumstances, valid non -immigrant visas, and legal status conferred by other laws. See 45 C.F.R. §155.305 and HealthCare.gov, “ Coverage for Lawfully Present Immigrants,” at https://www.healthcare.gov/immigrants/lawfully-present-immigrants/. 30 42 U.S.C. §18083, 45 C.F.R. §155.405. 31 Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that finances the delivery of primary and acute medical services, as well as long-term services and supports, to a diverse low-income population, including children, pregnant women, adults, individuals with disabilities, and people aged 65 and older. CHIP is a means-tested program that provides health coverage to targeted low-income children and pregnant women in families that have annual income above Me dicaid eligibility levels but have no health insurance. T he “applicable State health subsidy programs” also include the Basic Health Program, which is operational in two states: Minnesota and New York.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Interaction with Medicaid, CHIP, and Medicare

In conjunction with the streamlined application mentioned above, exchanges must have systems for coordinating with the Medicaid and CHIP programs on eligibility determinations and

enrollment into those programs, for eligible consumers. These systems may vary by state.32

Consumers who are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP may choose to buy exchange coverage instead, but they would not be eligible for financial assistance for exchange coverage (i.e., PTCs or cost-

sharing reduction subsidies).

There are some limitations on the sale of exchange plans to Medicare-eligible or Medicare-enrolled individuals.33 In short, it is general y il egal to sel an individual exchange plan to

someone enrolled in Medicare because it would duplicate coverage.

Open and Special Enrollment Periods

Consumers may enroll in coverage through the exchanges only during specified enrollment

periods.

Anyone eligible for exchange plan coverage may enroll during an annual open enrollment period (OEP).34 The OEP typical y takes place in fal of the year preceding the plan year (PY; the calendar year in the individual exchanges) during which the coverage is effectiveplan year. The OEP for calendar year 2018PY2021 coverage was November 1, 20172020, to December 15, 20172020, for FFE and SBE-FP states. States with SBEs may extend their OEPs, and many do. See Table 1, including table notes, for

details.

Before and during an OEP, consumers already enrolled in coverage through an exchange should receive notification from the exchange and from their insurer about the opportunity to make any

updates to their application data and/or coverage choices. Insurers must notify consumers of changes to their plans such as premiums, benefit coverage, or provider networks (such changes general y cannot be made during a plan year, only in preparation for, and as applicable to, a new

32 45 C.F.R. Part 155, Subpart D, including §155.302. Regarding FFE and SBE-FP states, also see “Medicaid & CHIP Eligibility” in Section 2.1 of CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollment Manual, June 26, 2018, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/General-Resources-Items/FFM-and-FF-SHOP-Enrollment -Manual. Information for consumers is at Medicare.gov, “ Medicare & the Marketplace,” at https://www.medicare.gov/about -us/medicare-the-marketplace. Hereinafter referred to as CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollm ent Manual. Regarding SBE states, also see Sara Rosenbaum et al., Stream lining Medicaid Enrollm ent: The Role of the Health Insurance Marketplaces and the Im pact of State Policies, Commonwealth Fund, March 30, 2016, at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/mar/streamlining-medicaid-enrollment -role-health-insurance. 33 Medicare is a federal health insurance program that pays for covered health care services for most people aged 65 and older and for certain permanently disabled individuals under the age of 65. T he prohibition on selling an individual exchange plan to someone enrolled in Medicare does not apply to employment -based coverage, including coverage sold in the SHOP exchanges. See CMS, “ Medicare and the Marketplace,” updated December 2019, at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-and-Enrollment/Medicare-and-the-Marketplace/Overview1.html. Also see Section 2.6.8 of CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollm ent Manual, June 26, 2018, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Health-Insurance-Marketplaces/General-Resources-Items/FFM-and-FF-SHOP-Enrollment -Manual. Information for consumers is at Medicare.gov, “ Medicare & the Marketplace,” at https://www.medicare.gov/about-us/medicare-the-marketplace. CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollm ent Manual.

34 45 C.F.R. §155.410.

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 7 link to page 12 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

plan year).35 If an existing exchange plan enrollee does not take any action during the OEP, they

general y wil be automatical y reenrolled in the same plan for the upcoming plan year.36

Table 1. Open Enrollment Periods for Individual Exchanges on the Federal Platform,

by Plan Year

Plan Year

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Oct. 1,

Nov. 15,

Nov. 1,

Nov. 1,

Nov. 1,

Nov. 1,

Nov. 1,

Nov. 1,

HealthCare.

2013-

2014-

2015-

2016-

2017-

2018-

2019-

2020-

gov OEP

Mar. 31,

Feb. 15,

Jan. 31,

Jan. 31,

Dec. 15,

Dec. 15,

Dec. 15,

Dec. 15,

2014

2015

2016

2017

2017

2018

2019

2020

Source: CRS analysis of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reports on enrol ment during annual open enrol ment periods. See the “Pre-effectuated Enrol ment Data” section of CRS Report R46638, Health Insurance Exchanges: Sources for Statistics for reports by year.

Notes: FFE = federal y facilitated exchange; OEP = open enrol ment period; PY = plan year; SBE = state-based exchange; SBE-FP = state-based exchange using the federal information technology platform; SEP = special enrol ment period. See “State-Based and Federal y Facilitated Exchanges” in this report for more information. The HealthCare.gov OEP applies to FFE and SBE-FP states. In some years, there also have been federal OEP extensions or SEPs for broadly applicable situations, such as in the 2018 OEP, due to natural disasters in 2017. See “Open and Special Enrol ment Periods” in this report for more information. The OEPs of SBEs may be longer in a given year. For PY2020, 9 of 13 SBEs extended their OEPs. See CMS, “2020 Marketplace Open Enrol ment Period Public Use Files” at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Marketplace-Products/2020-Marketplace-Open-Enrol ment-Period-Public-Use-Files.

Consumers also may be al owed, for FFE and SBE-FP states (see Table 1 for enrollment periods). States with SBEs may observe different OEPs. For 2018 coverage, all 12 SBEs' OEPs lasted longer than the federal OEP.13 The OEP for plan year 2019 is currently set as November 1, 2018, to December 15, 2018, for FFE and SBE-FP states.

Consumers also may be allowed to enroll for coverage in an exchange if they qualify for a special enrollment periodspecial enrollment period (SEP). General y (SEP).14 Generally, consumers qualify for SEPs due to a change in personal circumstances—for example, a change in marital status or number of dependents—or loss of qualifying coverage.15 37 HHS also may choose to offer SEPs or extend an OEP for some or all consumers due to broadly applicable circumstances.16 In addition, consumers generally may enroll in Medicaid or CHIP whenever they qualify, regardless of their state's exchange OEP.

Annual individual exchange enrollment estimates to date are shown in Table 1. Given the exchange eligibility determination process as well as the OEPs and SEPs, data on exchange enrollment are releasedal

35 See Section 2.6 of CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollment Manual; the “Reenrollment Communications to Enrollees” section cites CMS guidance: Updated Federal Standard Renewal and Product Discontinuation Notices, September 2016, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/Final-Updated-Federal-Standard-Renewal-and-Product -Discontinuation-Notices-090216.pdf. T here, see “ Instructions for Attachment 2.” 36 For more information about plan renewal options and processes, including automatic renewals of enrollees in their existing plans or in alternate plans if their existing ones will no longer be available, see Section 2.6 of CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollm ent Manual. Although this manual describes processes for HealthCare.gov states, SBEs also have processes for automatic reenrollment.

37 Qualifying coverage generally means the types of minimum essential coverage (MEC) that are identified in the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 5000A and its implementing regulations. Most types of comprehensive coverage are considered MEC, including public coverage (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare), as well as private insurance (e.g., employer-sponsored insurance and non-group insurance). For other types of coverage losses that can trigger an exchange special enrollment period (SEP), see 45 C.F.R. §155.420. Also see 45 C.F.R. §147.104 regarding SEPs applicable to the individual and group markets overall.

Congressional Research Service

9

Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

consumers due to broadly applicable circumstances.38 Subject to statutory requirements, HHS

may make changes to SEPs.39

Federal SEPs apply to FFEs, SBE-FPs and general y to SBEs, but SBEs have flexibility regarding

implementation of some SEPs. SBEs also may create their own SEPs, subject to applicable federal and state laws. Federal SEPs for the individual exchanges may or may not apply to the

federal SHOP exchanges and/or to the individual market outside the exchanges.40

Eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP may be determined at any point during the calendar year and has

no connection to an applicant’s state’s exchange OEP.

Special Enrollment Periods and COVID-19

During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and related economic recession,

there have been questions about SEPs to al ow consumers to enroll in coverage via the exchanges.

In response to COVID-19, most SBEs created SEPs to al ow individuals to purchase coverage. These SEPs general y were open in spring 2020, with varied timing and durations. Some were

extended one or more times. In general, these SEPs were available to any uninsured individuals

eligible for exchange coverage.41

In 2020, HHS did not announce a COVID-related federal SEP for al uninsured individuals to

enroll in coverage in FFEs and SBE-FPs. However, an existing SEP al ows individuals to enroll if they lose their job-based coverage or other qualifying coverage. A June 2020 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) report on exchange enrollment during the pandemic further stated that “any consumers who qualified for a SEP but missed the deadline as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic—for example, if they were sick with COVID-19 or were caring for

someone who was sick with COVID-19—may also be eligible for another SEP.”42 This is similar to federal SEPs announced in relation to prior disasters. In addition, at least as of the second half of 2020, the federal exchange website HealthCare.gov indicated that losing qualifying coverage since the start of 2020 could qualify someone for an SEP, as opposed to the standard eligibility

criterion of losing qualifying coverage in the prior 60 days.43

38 For example, in 2014, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) established an SEP due to technical problems submitting insurance applications through the federal information technology platform (i.e., HealthCare.gov). In 2015, HHS established an SEP around tax season for individuals who had not enrolled in 2015 coverage and were subject to the 2014 individual mandate penalty. For 2018 coverage, HHS established an SEP for consumers in states that were affected by the 2017 hurricanes or other severe weather events. See, for example, HHS, HealthCare.gov, “Special Enrollment Periods for Complex Issues,” at https://www.healthcare.gov/sep-list/. 39 Statutory requirements for exchange SEPs are at 42 U.S.C. §18031(c)(6). Multiple examples and discussion of administrative changes made to SEPs are in the HHS final rule, “ Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Market Stabilization,” 82 Federal Register 18346, April 18, 2017, at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/04/18/2017-07712/patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act-market-stabilization. T he background of this rule also provides information on prior administrative actions related to SEPs.

40 For more information about SEPs, see Section 5 of CMS, FFE and FF-SHOP Enrollment Manual. 41 T he National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) has been tracking various state-level actions related to COVID-19 and insurance, including SEPs announced by SBEs. See NAIC, “ Coronavirus Resource Center,” “ Life and Health” spreadsheet, at https://content.naic.org/naic_coronavirus_info.htm. 42 CMS, Special Trends Report: Enrollment Data and Coverage Options for Consumers During the COVID-19 Public Health Em ergency, June 2020, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/Downloads/SEP-Report -June-2020.pdf.

43 HealthCare.gov page on special enrollment periods, at https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage-outside-open-enrollment/special-enrollment -period/.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 16 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

On January 28, 2021, HHS (via CMS) announced a new COVID-19-related SEP, in effect February 15-May 15, 2021, to al ow al exchange-eligible consumers to newly enroll or update their enrollment in an exchange plan.44 Per the announcement, CMS also wil conduct a consumer outreach campaign to promote the SEP. This SEP is available in al states using the HealthCare.gov enrollment platform (FFEs and SBE-FPs); states with SBEs are “strongly

encouraged” by CMS to take similar action.

For information about other coverage options following loss of job-based coverage, see CRS In

Focus IF11523, Health Insurance Options Following Loss of Employment.

Enrollment Estimates

Annual individual exchange enrollment estimates to date are shown in Table 2. Given the exchange eligibility determination process, as wel as the different time frames of OEPs and SEPs, CMS releases data on exchange enrollment in stages. Pre-effectuated enrollment is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enroll in an exchange plan

and have selected a plan. These individuals may or may not have submitted the first premium payment. In general, cumulative and final pre-effectuated enrollment estimates are released

during and soon after an annual open enrollment period.

Subsequently, effectuated enrollment is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enroll in an exchange plan, have selected a plan, and have submitted the first premium payment for an exchange plan. Effectuated enrollment estimates generallygeneral y are point-in-time and may change over the coverage year. For example, due to changes in life circumstances, an individual may disenroll (e.g., if later offered coverage through an employer) ,

or enroll (e.g., given eligibility for an SEP) in an exchange plan.

|

PY2014 |

PY2015 |

PY2016 |

PY2017 |

PY2018 |

|

|

Oct. 1, 2013-Mar. 31, 2014 |

Nov. 15, 2014-Feb. 15, 2015 |

Nov. 1, 2015-Jan. 31, 2016 |

Nov. 1, 2016-Jan. 31, 2017 |

Nov. 1, 2017-Dec. 15, 2017 |

|

8.0 million |

11.7 million |

12.7 million |

12.2 million |

|

|

6.3 million as of Dec. 2014 |

|

|

|

Not released as of this report |

Source: CRS analysis based on Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) annual reports of individual exchange enrollment in private health insurance plans. Some of these reports are available at HHS, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), "Historical Research," at https://aspe.hhs.gov/historical-research. Some are available at CMS, Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight (CCIIO), "Data Resources," at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/ Resources/Data-Resources/index.html; others are available elsewhere on the CMS site. The 2018 pre-effectuated estimates are available at CMS, "Health Insurance Exchanges 2018 Open Enrollment Period Final Report," April 3, 2018, at https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2018-Fact-sheets-items/2018-04-03.html. Contact report author for all sources.

Notes: PY = plan year; OEP = open enrollment period; SEP = special enrollment period. FFE = federally facilitated exchange; SBE = state-based exchange; SBE-FP = state-based exchange using the federal information technology platform. See "State-Based and Federally Facilitated Exchanges" in this report for more information.

a. The Healthcare.gov OEP applies to FFE and SBE-FP states. The OEPs of SBEs may be longer in a given year. In some years, there also have been federal OEP extensions or SEPs for broadly applicable situations, such as in the 2018 OEP, due to natural disasters in 2017. See "Enrollment Periods" and footnote 16 in this report.

b. Pre-effectuated enrollment is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enroll in an exchange plan and have selected a plan but may or may not have submitted the first premium payment. Final pre-effectuated enrollment estimates are typically released following an OEP and include any broadly applicable OEP extensions or longer SBE OEPs. See "Enrollment Periods" in this report for more information.

c. Effectuated enrollment is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enroll in an exchange plan, have selected a plan, and have submitted the first premium payment for an exchange plan. HHS may release effectuated enrollment estimates for different points in time over a plan year. See "Enrollment Periods" in this report for more information.

d. CMS initially (in June 2016) reported 11.1 million effectuated enrollment as of March 2016. In June 2017, CMS updated this number to 10.8 million as of March 2016 and 9.1 million as of December 2016.

e. As of the date this report was published, these are the latest effectuated data released for 2017.

, outside of an OEP.

CMS also releases average effectuated enrollment estimates over specified time periods (e.g., over the first half of an enrollment year or monthly for the previous enrollment year). See the

“Enrollment Statistics” section of CRS Report R46638, Health Insurance Exchanges: Sources for

Statistics, for HHS reports and resources detailing different enrollment estimates by year.

44 CMS, “ 2021 Special Enrollment Period in response to the COVID-19 Emergency,” January 28, 2021, at https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/2021-special-enrollment -period-response-covid-19-emergency.

Congressional Research Service

11

link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 12 link to page 12 link to page 7 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

Table 2. Nationwide Individual Exchange Enrollment Estimates, by Plan Year

Plan Year

Nationwide

Enrollment

Estimate

Type

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Pre-

Data

effectuateda

expected

final for PY

8.0M

11.7M

12.7M

12.2M

11.8M

11.4M

11.4M

spring

OEP

2021

Effectuated,

Early

early in the

2014

Data

plan year

10.2M,

11.1M,

10.3M,

10.6M,

10.6M,

10.7M,

expected

(point-in-time

estimate

Mar.

Mar.

Feb.

Feb.

Feb.

Feb.

summer

as of date

not

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

shown)b

found

Effectuated, late in the plan

Data

Data

year (point-in-

6.3M,

8.8M,

9.1M,

8.9M,

9.2M,

9.1M,

expected

expected

time or

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

Dec.

summer

summer

average for

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2021

2022

month shown)c

Source: CRS analysis based on Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) reports of individual exchange enrol ment. Data sources are in CRS Report R46638, Health Insurance Exchanges: Sources for Statistics, in report sections specified in table notes below. Notes: FFE = federal y facilitated exchange; OEP = open enrol ment period; PY = plan year; SBE = state-based exchange; SBE-FP = state-based exchange using the federal information technology platform. See “Open and Special Enrol ment Periods” and “State-Based and Federal y Facilitated Exchanges” in this report. a. Pre-effectuated enrol ment is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enrol in

an exchange plan and have selected a plan but may or may not have submitted the first premium payment. Final pre-effectuated enrol ment estimates typical y are released fol owing an OEP and include any broadly applicable OEP extensions or longer SBE OEPs. For these data sources by year, see the “Pre-effectuated Enrol ment Data” section of the report mentioned above.

b. Effectuated enrol ment is the number of unique individuals who have been determined eligible to enrol in an

exchange plan, have selected a plan, and have submitted the first premium payment for an exchange plan. HHS general y releases effectuated enrol ment estimates for a point i time early in the plan year and may release additional point-in-time estimates during the year. Data sources by year are in the “Point-in-Time Effectuated Enrol ment Data” section of the report mentioned above. For example, the 2020 data is from CMS, Early 2020 Effectuated Enrol ment Snapshot, July 2020.

c. See table note (b) regarding effectuated enrol ment and point-in-time estimates. Average estimates reflect

an average over a specified time period, in this case one month. For PY2014 and PY2015, quarterly point-in-time estimates were released, including those shown. Average monthly enrol ment data were not provided for those years. For PYs 2016 and on, average monthly enrol ment data are provided. Although point-in-time and average monthly estimates are not the same, they are provided here to show late-year enrol ment estimates across al plan years. Data sources by year are in the “Point-in-Time Effectuated Enrol ment Data” and “Average Monthly Effectuated Enrolment Data” sections of the report mentioned above. For example, the 2018 data is from the end of the report CMS, Early 2019 Effectuated Enrol ment Snapshot, August 2019.

Premiums and Cost Sharing Typical y, enrollees of private health insurance plans (in or out of the exchanges) pay monthly premiums. They also are general y responsible for out-of-pocket (OOP) costs, or cost sharing, as

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 9 link to page 18 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

they use services. In general, cost sharing includes deductibles, coinsurance, and co-payments, up

to an annual maximum amount of OOP spending.45

Premiums are set by health insurance issuers and are based on their expected medical claims costs

(i.e., the payments they expect to make for covered health benefits for a given group of enrollees, or a given risk pool), administrative expenses, taxes, fees, and profit. The premium-setting process is subject to federal and state requirements, as applicable to plans both in and out of the exchanges. For example, insurers cannot vary premiums based on health status.46 In addition, insurers that want to offer plans in the exchanges must submit their proposed premiums for

federal or state approval (depending on exchange type) each year.47 If consumers do not pay their premiums, insurers may terminate their coverage, subject to applicable federal and state

requirements.48

In addition to setting premiums, insurers set cost-sharing levels, or the share of the costs of covered benefits (or medical claims) for which the insurer and enrollee wil be responsible. Most health plans sold through the exchanges (and non-grandfathered plans sold in the individual and smal -group markets off-exchange49) are subject to minimum actuarial value (AV) standards and accordingly, are given a precious metal designation (platinum, gold, silver, or bronze).50 AV is a

summary measure of a plan’s generosity in terms of cost sharing, estimated for a standard population.51 Actuarial values by metal level are platinum (AV of 90%), gold (80%), silver (70%), and bronze (60%). For example, for a silver plan, the insurer expects to cover approximately 70% of cost sharing for the plan’s enrollees overal . The higher the AV percentage, the lower the cost sharing, on average, for the plan population. However, plans with higher AV also may have higher premiums, on average, to cover their increased share of their enrollees’ medical claims

costs (assuming other factors affecting premiums remain the same, such as administrative expenses). The AV standards, and the related metal levels, are meant, in part, to help consumers in

comparing the value of plans.

45 A deductible is the amount an insured consumer pays for covered health care services before coverage begins (with exceptions). Coinsurance is the share of costs, figured in percentage form, an insured consumer pays for a covered health service. A co-paym ent is the fixed dollar amount an insured consumer pays for a covered health service. Once an insured consumer’s out-of-pocket spending has met an out-of-pocket limit or maximum in a plan year, the insurer will generally pay 100% of covered costs for the remainder of the plan year.

46 See CRS Report R45146, Federal Requirements on Private Health Insurance Plans, for more information about this and other requirements related to setting premiums.

47 See “Exchange Administration” in this report. 48 See 45 C.F.R. §156.270 regarding insurer termination of enrollee coverage, including for nonpayment of premiums. It also addresses the “grace period” of three consecutive months of premium nonpayment for enrollees who receive a premium tax credit (discussed in the “ Premium T ax Credits and Cost -Sharing Reductions” section of this report ).

49 Grandfathered plans are individual or group plans in which at least one individual was enrolled as of enactm ent of the ACA (March 23, 2010) and which continue to meet certain criteria. Plans that maintain their grandfathered status are exempt from some, but not all, federal requirements. T here are no grandfathered plans sold through the exchanges, but they may be available off the exchanges. For more information, see CRS Report R46003, Applicability of Federal Requirem ents to Selected Health Coverage Arrangem ents, as well as HHS, “ Grandfathered Health Insurance P lans,” at https://www.healthcare.gov/health-care-law-protections/grandfathered-plans/. 50 42 U.S.C. §18022(d). 51 Actuarial value (AV) is expressed as the percentage of medical expenses estimated to be paid by the insurer for a standard population and set of allowed charges. It is not a measure of plan generosity for an enroll ed individual or family, nor is it a measure of premiums or benefits packages. AV calculations are required to apply only to the plan’s covered essential health benefits (EHB) that are furnished by an in-network provider, unless otherwise addressed in federal or state law.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 39 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 44 link to page 16 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

With the exception of “catastrophic” plans and stand-alone dental plans (see Table B-1), plans must have at least 60% AV to be sold in the exchanges. Insurers sel ing a given plan in an exchange must offer at least a silver and gold version of the plan throughout each service area in

which the insurers offer coverage.52

Annual OOP limits also apply to al health plans sold in the exchanges (and to al non-grandfathered individual and group plans sold outside the exchanges).53 These limits are updated each year through HHS rulemaking (see Table 3). Plans may set their OOP limits lower than

these maximums. Additional data on premiums and cost sharing are in Table 4 at the end of the following section.

Table 3. Annual Out-of-Pocket Limits, by Plan Year

(federal y set maximums; insurers may set lower out-of-pocket limits)

Plan Year

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Self-only coverage

$6,350

$6,600

$6,850

$7,150

$7,350

$7,900

$8,150

$8,550

Coverage other

$12,700

$13,200

$13,700

$14,300

$14,700

$15,800

$16,300

$17,100

than self-only

Percentage increase

N/A

4%

4%

4%

3%

7%

3%

5%

over prior year

Source: CRS analysis of relevant federal rulemaking. These amounts are updated each year through an HHS rule cal ed the Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters, also known as the Payment Notice. For example, the PY2021 rates were finalized in the 2021 Payment Notice, p. 7127. Although a final 2022 Payment Notice was published in January 2021, it did not include these amounts for PY2022. Annual Payment Notices are cited in Table D-1. Notes: PY = plan year. Out-of-pocket (OOP) limits are related to an insured consumer’s cost sharing, or OOP spending (including deductibles, coinsurance, and co-payments; see “Premiums and Cost Sharing” in this report for more information). Once this OOP spending meets the plan’s OOP limit or maximum in a plan year, the insurer general y wil pay 100% of covered costs for the remainder of the plan year. An individual enrol ed in a plan by themselves has self-only coverage. An individual enrol ed in a plan with a spouse and/or dependents has coverage other than self-only, or family coverage.

Premium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Reductions

Premium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Reductions

Consumers purchasing coverage through the individual exchanges may be eligible to receive

financial assistance that effectively reduces their cost of that coverage. Eligibility for such assistance is based primarily on income and provided in the form of premium tax credits (PTCs)

and cost-sharing reductions.17

The premium tax credit is generally available to consumers (CSRs).54

The PTC general y is available to consumers with household incomes between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL), with some exceptions, and who do not have access to public coverage (e.g., Medicaid) or employment-based coverage that meets certain standards.18 The credit is designed to reduce an eligible individual' individual’s cost of purchasing health insurance coverage

52 45 C.F.R. §156.200(c)(1). 53 Like AV calculations, the annual out -of-pocket limit is only required to apply to the plan’s covered EHB that are furnished by an in-network provider, unless otherwise addressed in federal or state law.

54 For more information about these forms of consumer financial assistance, including applicable eligibility criteria and illustrative examples, see CRS Report R44425, Health Insurance Prem ium Tax Credits and Cost-Sharing Subsidies.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 20 link to page 20 Overview of Health Insurance Exchanges

s cost of purchasing health insurance coverage through the exchange. The amount of the premium tax creditPTC is based on a statutory formula and varies from person to person. It is designed to provide larger credit amounts to individuals with lower incomes compared to those with higher incomes.

The premium credit is refundable, so individuals may claim the full credit amount when filing their taxes, even if they have little or no federal income tax liability. The credit also is advanceable, so instead of waiting until they file taxes, individuals may choose to receive the credit on a monthly basisAlthough the amount of the PTC is based on the second-lowest-cost silver plan in a consumer’s local area, consumers may apply the credit to any

bronze- or higher-metal level plan available to them on their state’s exchange.

Individuals who receive PTCs also may be eligible for subsidies that reduce cost-sharing expenses.55 These cost-sharing subsidies (also cal ed CSRs) are applied in two ways. First, an insurer must reduce the annual OOP limit that otherwise would apply to an eligible individual’s

exchange plan. Second, the insurer must effectively raise the actuarial value of the eligible individual’s plan, for example by reducing other cost-sharing requirements beyond the lowered OOP cap. Among other eligibility requirements, CSRs general y are available to consumers who are eligible for PTCs and have incomes between 100% and 250% of the FPL. Although a PTC

can be applied to any metal level plan, CSRs are applicable only to silver plans.

Table 4 summarizes nationwide data on premiums, advance premium tax credit (APTC) 56, and CSRs by year, as available in relevant HHS reports on effectuated enrollment.57 The average premium and APTC amounts shown in the table may obscure wide variations in actual amounts

per consumer, depending on the plan and metal level an individual chooses and/or the factors by which an insurer is able to vary premiums, discussed below.58 Premium and cost-sharing data on al plans offered in the exchanges, as opposed to such data for plans selected, also are available,

including for PY2021.59

55 T he ACA requires the HHS Secretary to provide full reimbursements to insurers that provide these cost -sharing subsidies to their enrollees. However, the ACA did not appropriate funds for such payments. In October 2017, the T rump Administration halt ed these payments, effective immediately, until Congress appropriates funds. I nsurers still must provide the subsidies to eligible consumers, but insurers are not reimbursed. See HHS, “ Payments to Issuers for Cost-Sharing Reductions,” October 12, 2017, at https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/csr-payment -memo.pdf. 56 Consumers may choose to receive the credit on a monthly basis, in advance of filing taxes, to coincide with the payment of insurance premiums (technically, these advance payments go directly to issuersinsurers). Advance payments automatically reduce monthly premiums by the credit amount. T his option is called the advance premium tax credit, or APT C. Consumers may instead claim the full credit amount of the PT C when filing their taxes, even if they have little or no federal income tax liability.