Canada-U.S. Relations

Changes from June 14, 2018 to February 10, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Political Situation

- 2015 Parliamentary Elections

- Trudeau Government

- Foreign and Security Policy

- NATO Commitments

- Participation in Coalition to Combat the Islamic State

- U.S.-Canada Defense Relations

- NORAD

- Ballistic Missile Defense

- F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program

- Border Security

- Cybersecurity

- Economic and Trade Policy

- Budget Policy

- Monetary Policy

- U.S.-Canada Trade Relations

- NAFTA Renegotiation

- Softwood Lumber

- Steel and Aluminum Tariffs

- Commercial Aircraft

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

- Wine Exports

- Energy

- Keystone XL Pipeline

- Trans-Mountain Pipeline

- Environmental and Transboundary Issues

- Climate Change

- Paris Agreement Commitments

- Pan-Canadian Framework (PCF)

- U.S.-Canada GHG Emissions Cooperation

- Columbia River Treaty

- Great Lakes

Figures

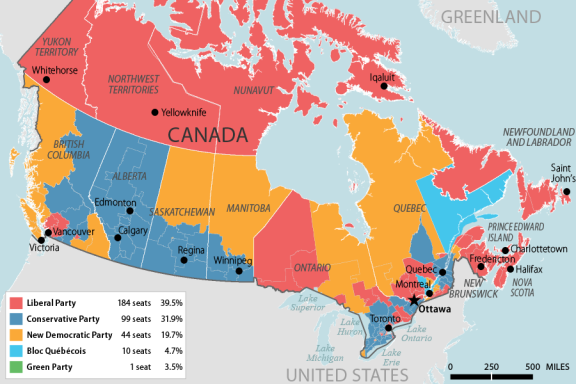

- Figure 1. Map of Canada's 2015 General Election Results

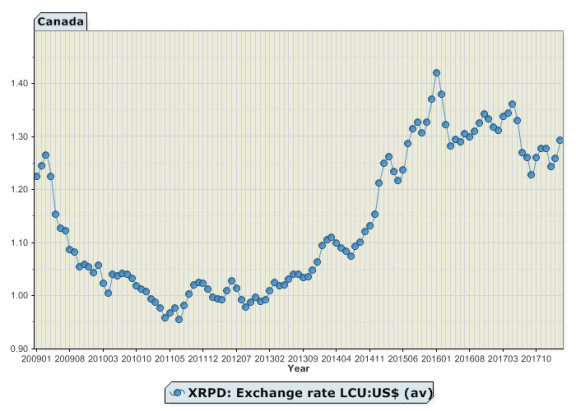

- Figure 2. United States and Canada Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP): 2008-2017

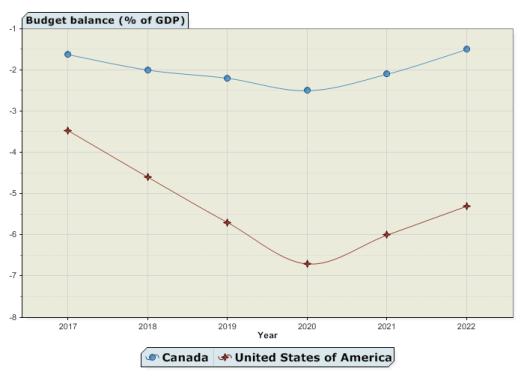

- Figure 3. Projected Budget Deficits: United States and Canada: 2017-2022

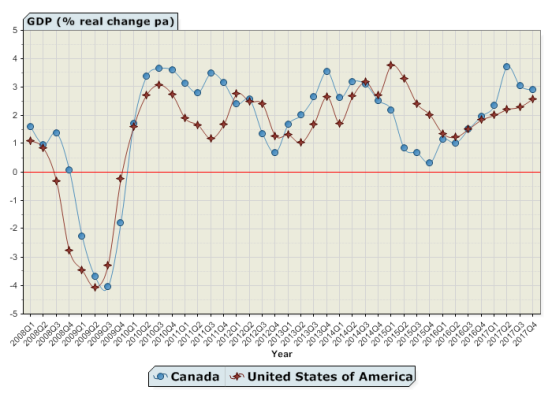

- Figure 4. Exchange Rates: 2009-2018, Quarter 1

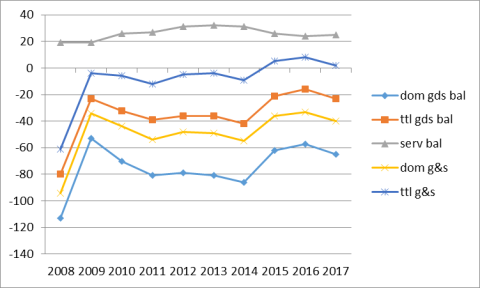

- Figure 5. U.S. Trade Balance with Canada: 2008-2017

Summary

Relations between the United States and Canada traditionally have been close, bound together by a common 5,500-mile border—"the longest undefended border in the world"—as well as by shared history and values. The countries have long-standing mutual security commitments under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), and continue to work together to address international security challenges, such as the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq and Syria. Canada and the United States also maintain close intelligence and law enforcement ties and have engaged in a variety of initiatives to strengthen border security and cybersecurity in recent years.

Although Canada's foreign and defense policies are usually in harmony with those of the United States, disagreements arise from time to time. Canada's Liberal Party government, led by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has prioritized multilateral efforts to renew and strengthen the rules-based international order since coming to power in November 2015. It has expressed disappointment with President Donald Trump's decisions to withdraw from international accords, such as the Paris Agreement on climate change, and has questioned whether the United States is abandoning its global leadership role. Such concerns have been heightened by the discord witnessed at the G-7 summit held at Charlevoix, Quebec, in June 2018.

The United States and Canada maintain extensive commercial ties, with total two-way cross-border goods and services trade amounting to over $1.6 billion per day in 2017. Bilateral trade relations have grown increasingly strained, however, as old irritants, such as softwood lumber trade, have reemerged, and the countries' differing trade policy objectives have given rise to new disputes. Efforts to renegotiate the 1994 North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Trump Administration's imposition of tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum have proven particularly contentious.

Many Members of Congress follow U.S.-Canada issues that affect their states and districts, such as Great Lakes restoration efforts and ongoing negotiations over the Columbia River Treaty. Since Canada and the United States are similar in many ways, lawmakers in both countries also study solutions proposed across the border on such issues as federal fiscal policy and federal-provincial power sharing. U.S. and Canadian domestic policies have diverged on a variety of matters over the past year and a half, including taxation and environmental protection.

This report presents an overview of Canada's political situation, foreign and security policy, and economic and trade policy, focusing particularly on issues that may be relevant to U.S. policymakers.

Introduction

Canada-U.S. Relations

February 10, 2021

The United States and Canada typically enjoy close relations. The two countries are bound together by a common 5,525-mile border—“the longest undefended border in the world”—as

Peter J. Meyer

well as by shared history and values. They have extensive trade and investment ties and long-

Specialist in Latin

standing mutual security commitments under NATO and North American Aerospace Defense

American and Canadian

Command (NORAD). Canada and the United States also cooperate closely on intelligence and

Affairs

law enforcement matters, placing a particular focus on border security and cybersecurity

initiatives in recent years.

Ian F. Fergusson Specialist in International

Although Canada’s foreign and defense policies usually are aligned with those of the United

Trade and Finance

States, disagreements arise from time to time. Canada’s Liberal Party government, led by Prime

Minister Justin Trudeau, has prioritized multilateral efforts to renew and strengthen the rules -based international order since coming to power in November 2015. It expressed disappointment

with former President Donald Trump’s decisions to withdraw from international organizations and accords, and it questioned whether the United States was abandoning its global leadership role. Cooperation on international issues may improve under President Joe Biden, who spoke with Prime Minister Trudeau in his first call to a foreign leader and expressed interest in working with Canada to address climate change and other global challenges.

The United States and Canada have a deep economic partnership, with approximately $1.4 billion of goods crossing the border each day in 2020. Bilateral trade relations have been somewhat strained in recent years, however, due to the countries’ differing trade policy objectives. Canadian officials expressed particular frustration with the Trump Administration’s insistence on renegotiating the 1994 North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which resulted in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), and its imposition of tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum. The Biden Administration may take a less confrontational approach to trade relations with Canada. Nevertheless, some long-standing issues, such as cross-border oil pipelines, softwood lumber, and Buy American policies , likely will remain contentious.

Because Canada and the United States are similar in many ways, lawmakers in both countries often study policies and solutions proposed across the border. U.S. and Canadian domestic policies diverged on various matters over the past four years, as the Trudeau government implemented a carbon pricing system to address climate change, legalized the recreational cannabis market, increased refugee resettlement, and expanded Canada’s social safety net. The U.S. and Canadian governments also diverged in their responses to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic with respect to the role of the federal government and fiscal policies to mitigate the economic impact on individuals and businesses.

The 116th Congress enacted several measures related to U.S.-Canada relations. Perhaps most significantly, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Implementation Act (P.L. 116-113) was signed into law in January 2020, paving the way for the

agreement’s entry into force. Congress also continued to support Great Lakes restoration efforts, appropriating $320 million for such purposes in FY2020 (P.L. 116-94) and $330 million in FY2021 (P.L. 116-260). In 2019, both houses adopted resolutions (S.Res. 96 and H.Res. 521) commending Canada for upholding the rule of law and its international legal commitments following the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, an executive at the Chinese technology company Huawei, to comply with an extradition request from the United States. U.S.-Canada cooperation on trade, environmental protection, foreign affairs, and various other issues may remain of interest to the 117th Congress.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 19 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 24 link to page 26 link to page 27 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 32 link to page 32 link to page 34 link to page 35 link to page 36 link to page 38 link to page 39 link to page 39 link to page 40 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 42 link to page 43 link to page 44 link to page 45 link to page 45 link to page 46 link to page 48 link to page 50 link to page 8 link to page 9 link to page 22 Canada-U.S. Relations

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Politics and Governance ................................................................................................... 2

Liberal Majority Government: 2015-2019 ..................................................................... 3 2019 Election............................................................................................................ 3 Minority Government and Pandemic Response .............................................................. 4

Foreign and Defense Policy .............................................................................................. 7

NATO Commitments ................................................................................................. 9 Relations with China ................................................................................................ 10 U.S.-Canada Security Cooperation ............................................................................. 12

North American Aerospace Defense Command ....................................................... 12

Border Security .................................................................................................. 13 Cybersecurity .................................................................................................... 15

Economic and Trade Policy ............................................................................................ 17

Budget Policy ......................................................................................................... 18 Monetary Policy ...................................................................................................... 20 Investment.............................................................................................................. 22 U.S.-Canada Trade Relations ..................................................................................... 23

United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement .............................................................. 25 Canada’s Network of Free Trade Agreements ......................................................... 27

Disputes............................................................................................................ 28

Softwood Lumber ......................................................................................... 28 Dairy .......................................................................................................... 30 Intel ectual Property Rights ............................................................................ 31 Government Procurement............................................................................... 32

Steel and Aluminum Tariffs ............................................................................ 34

Energy......................................................................................................................... 35

Keystone XL Pipeline .............................................................................................. 35

Trans-Mountain Pipeline........................................................................................... 36

Environmental and Transboundary Issues ......................................................................... 37

Climate Change....................................................................................................... 37

Paris Agreement Commitments ............................................................................ 38

Climate Strategy ................................................................................................ 39

COVID-19 Climate Mitigation Activities.......................................................... 40 Healthy Environment and Healthy Economy Plan .............................................. 41

U.S.-Canada Cooperation to Reduce Greenhouse-Gas Emissions............................... 41

The Arctic .............................................................................................................. 42

Great Lakes ............................................................................................................ 44

Outlook ....................................................................................................................... 46

Figures Figure 1. Map of Canada’s 2019 Federal Election Results ..................................................... 4 Figure 2. Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 in Canada............................................................. 5 Figure 3. Recorded and Projected Real GDP, United States and Canada: 2017-2022 ................ 18

Congressional Research Service

link to page 23 link to page 25 link to page 25 link to page 26 link to page 21 link to page 28 link to page 39 link to page 41 link to page 41 link to page 50 Canada-U.S. Relations

Figure 4. Recorded and Projected Budget Deficits, United States and Canada: 2017-2025 ........ 19 Figure 5. Recorded and Projected Policy Interest Rates, United States and Canada: 2004-

2025......................................................................................................................... 21

Figure 6. Exchange Rates: 2005-2020 .............................................................................. 22

Tables Table 1. United States and Canada: Selected Comparative Economic Statistics, 2019 .............. 17 Table 2. Composition of Trade with Canada 2020: Top 15 Commodities................................ 24 Table 3. U.S. Crude Oil Imports from Canada: 2016-2020 ................................................... 35 Table 4. Selected Greenhouse-Gas (GHG) Emissions Indicators in Canada and the United

States ....................................................................................................................... 37

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 46

Congressional Research Service

Canada-U.S. Relations

Introduction History, proximity, commerce, and shared values underpin the relationship between the United States and Canada. Americans and Canadians fought side by side in both World Wars, Korea, and

Afghanistan, and the United States and Canada continue to collaborate on various international political and security matters, such as the campaign against the Islamic State. The countries also share mutual security commitments under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO),NATO; cooperate on continental defense through the binational North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD),; maintain a close intelligence partnership through the "Five Eyes"intel igence partnership as members of the “Five Eyes” group of nations,; and coordinate frequently on law enforcement efforts, with a particular

focus on securing their shared 5,500525-mile border.

Bilateral 1

Bilateral economic ties, which were already considerable, have deepened markedly over the past three decades as trade relations have been governed . Trade and investment relations during this period were governed first by the 1989

by the 1989 U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement and, since 1994, subsequently by the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Canada is the second; the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) has guided the economic partnership since its entry into force on July 1, 2020.2 Canada is the third-largest goods -largest trading partner of the United States, with total two-way cross-border goods and services trade amounting to over $1.6 billion per day in 2017.more than $525 bil ion in 2020.3 The United States is also the largest investor in Canada, whileand Canada is an important source of foreign direct investment in the United States. The

countries have a highly integrated energy market, withand Canada beingis the largest supplier of U.S.

energy imports.

Unlike many countriesenergy imports and the largest recipient of U.S. energy exports.

Unlike with many countries, whose bilateral relations are conducted solely through foreign ministries, the governments of the United States and Canada have deep relationships, often extending far down the bureaucracy, to address matters of common interest. For more than 60 years, the U.S. Congress has engaged directly with the Canadian Parliament through the Canada-United States Inter-Parliamentary Group (see textbox below). Initiatives between the states and provinces also are common, such as California and Quebec’s linked greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions trading

market under the Western Climate Initiative and various other initiatives to manage

transboundary environmental and water issues.

Canada-United States Inter-Parliamentary Group

Since 1959, the U.S. Congress and the Canadian Parliament have maintained an Inter-Parliamentary Group (IPG) to foster mutual understanding and discuss bilateral and multilateral matters of concern to both countries. The IPG includes bipartisan representatives of the U.S. House and Senate and multiparty representatives of the Canadian House of Commons and Senate. Members historical y have met annual y, with the location alternating between the United States and Canada; however, more than 2½ years have passed since the last annual meeting (the 56th), held in Ottawa in June 2018.

Notes: For more on the IPG, see P.L. 86-42, at https://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/86/42.pdf; H. Rept 86-215; and Parliament of Canada, “Canada-United States Inter-Parliamentary Group,” at https://www.parl.ca/diplomacy/en/associations/ceus.

Nevertheless, with a population and economy one-tenth the size of the United States, Canada has sought to protect its autonomy and chart its own course in the world while maintaining its historical and political ties to the British Commonwealth. Some in Canada question whether U.S. investment, regulatory cooperation, border harmonization, or other public policy issues cede too

1 In addition to the United States and Canada, the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance includes Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

2 Often referred to as the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) in Canada. 3 U.S. Census Bureau, “U.S. International T rade in Goods and Services – December 2020,” February 5, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

1

Canada-U.S. Relations

much sovereignty to the United States, whereas others embrace a more North American approach

to Canada’s neighborly relationship.

Policy differences, such as Canada’Initiatives between the provinces and states are also common, such as the 2013 Pacific Coast Action Plan on Climate and Energy among California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, or various initiatives to manage transboundary environmental and water issues.

Nevertheless, bilateral relations have been strained from time to time by individual matters, such as Canada's decision not to participate in the Iraq war in 2003 and the

Obama Administration'’s rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline in 2015. Although the in 2015, have strained bilateral relations from time to time. The Canadian government welcomed the Trump Administration's March 2017 decision to revive President Trump’s revival of Keystone XL, but several other areas of contention have emergedemerged during his Administration. Canadian officials expressed particular frustration withofficials have been particularly frustrated by the Trump Administration's approach to renegotiating NAFTA and other trade disputes, such as the Administration's decision to impose tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum. U.S. policy shifts also have affected the opinions of Canadian citizens, 76% of whom disapproved of the "job performance of the leadership of the United States" in 2017.1 This could hinder efforts to conclude bilateral agreements or obtain Canadian support for U.S. initiatives moving forward.

|

"Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt." —Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, 1969. |

With a population and economy one-tenth the size of the United States, Canada has always been sensitive to being swallowed up by its southern neighbor. Whether by repulsing actual attacks from the United States during the War of 1812, or by resisting free trade with the United States for more than the first century of its history, it has sought to chart its own course in the world, yet maintain its historical and political ties to the British Commonwealth. Some in Canada question whether U.S. investment, regulatory cooperation, border harmonization, or other public policy issues cede too much sovereignty to the United States, while others embrace a more North American approach to its neighborly relationship.

Political Situation

Canada is a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as sovereign. In Canadian affairs, she is represented by a Governor-General (since October 2017, Julie Payette)’s trade policies, including its approach to USMCA negotiations and its decision to impose tariffs on Canadian steel and

aluminum on national security grounds. Canadian officials also expressed concerns about the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on climate change and its broader questioning of the multilateral institutions and rules that have helped to govern international relations since the end of World War II. The Trump Administration’s policies appear to have contributed to a significant shift in Canadian public opinion, as the percentage of Canadians holding favorable views of the United States declined by 30 percentage points between 2016 and

2020.4

President Joe Biden spoke with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during his first cal with a foreign

leader, highlighting the strategic importance of the U.S.-Canada relationship.5 Although both leaders cal ed for reinvigorating bilateral cooperation, they are likely to contend with policy differences on a range of issues. For example, Prime Minister Trudeau and other Canadian officials already have expressed disappointment with President Biden’s decision to revoke a presidential permit for the Keystone XL pipeline.6 The Biden Administration also may face

lingering doubts among Canadians regarding the United States’ reliability as a long-term partner.

This report presents an overview of Canada’s political situation, foreign and defense policies, and economic and trade policies, focusing particularly on issues that may be relevant to U.S.

policymakers. It also examines several environmental and transboundary issues that may be of

interest to Members of the 117th Congress.

Politics and Governance Canada is a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. Queen Elizabeth II is the head of state; she is represented in Canadian affairs by a governor-general, who is appointed on the advice of the prime minister. The Canadian government is a parliamentary democracy with a and carries out certain constitutional, ceremonial, and

representational duties. Canada’s bicameral Westminster-style Parliament that includes an elected, 338-seat House of Commons and an appointed, 105-seat Senate. Members of Parliament are elected from individual districts ("ridings"ridings) under a first-past-the-post system, which only requires a plurality of the vote to win a seat. The governor-general typical y cal s upon the party winning the most seats typically is called upon to form a government. A government lasts as long as it can command a parliamentary

majority for its policies, for a maximum of four years. Under Canada's 10 provinces and 3 territories are each’s federal system, the national government shares power and authority with 10 provinces and three territories, each of

which is governed by a unicameral assembly.

Justin Trudeau was sworn in as Canada's prime minister on November 4,

4 Richard Wike, Janell Fetterolf, and Mara Mordecai, “U.S. Image Plummets Internationally as Most Say Country Has Handled Coronavirus Badly,” Pew Research Center, September 15, 2020. 5 White House, “Readout of President Joe Biden Call with Prime Minister Justin T rudeau of Canada, ” January 22, 2021. 6 Justin T rudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, “Prime Minister Justin T rudeau Speaks with the President of the United States of America Joe Biden,” January 22, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 41 link to page 39 Canada-U.S. Relations

Liberal Majority Government: 2015-2019 Justin Trudeau has served as Canada’s prime minister since November 2015. His Liberal Party

2015. His Liberal Party won a majority in the House of Commons in October 2015 parliamentary elections, defeating Prime Minister Stephen Harper'’s Conservative Party, which had held power for nearly a decade. The Liberals'’ dominant position in the House of Commons has enabled them to implement much of their campaign platform, including measures intended to foster inclusive economic growth, address climate change, and reorient Canada's foreign policy. Nevertheless, Trudeau's approval rating has declined substantially since early 2017 and the Liberal Party is now polling slightly behind the Conservatives. The next federal election is due by October 2019.

2015 Parliamentary Elections

Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative Party entered the 2015 election campaign having governed Canada for nearly a decade. The party first came to power in 2006, just three years after it was established as a result of the unification of the Progressive Conservative party and the Canadian Alliance—a fiscally conservative, western Canadian faction dissatisfied with the eastern tilt of the traditional parties. The Conservatives formed a minority government after the 2006 election, and again after a snap election in 2008, but gained a majority in Parliament in the 2011 election. Harper and the Conservatives campaigned on their management of the economy following the 2008 financial crisis and their enactment of antiterrorism legislation following the 2014 Parliament Hill shootings.2 Many of Harper's initiatives were controversial outside of his political base, however, and the contraction of the Canadian economy during the first half of 2015 as a result of the decline in the price of oil further eroded support for the Conservatives.

Given fatigue with Harper and unease about the economy, many voters reportedly based their decision on which party had the best chance to defeat the Conservatives. The anti-Harper vote was divided primarily between Trudeau's Liberal Party and the New Democratic Party (NDP) led by Thomas Mulcair. The Liberal Party—long known as the "natural party of government" due to its dominance in the 20th century—had its worst showing ever in 2011, when it placed a distant third and was supplanted by the NDP as the main left-of-center party in Parliament. Some analysts even suggested the party could disappear as Canadian politics polarized between the Conservatives and the NDP.3 The election of Trudeau—son of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (1968-1979, 1980-1984)—as party leader helped the Liberals recover some support, but many Canadians perceived the then-43-year-old as lacking experience. Mulcair and the NDP, having served as the Official Opposition, started the campaign in a stronger position and held a slight lead in the polls through the first month of the 11-week campaign. Trudeau gained momentum with better-than-expected debate performances, and outflanked Mulcair on the left with his signature policy proposal to stimulate the economy with three years of deficit spending on new infrastructure and support for the middle class.

In the end, the Liberals won 184 seats in the House of Commons, up from 34 in 2011, the largest seat gain in Canadian history. In addition to sweeping all 32 seats in the Atlantic Provinces, the Liberal Party dominated in the Toronto metropolitan area, regained its footing in Quebec, won the most seats in British Colombia since 1968, and won two seats in the Conservative stronghold of Calgary (see Figure 1). The Conservatives won 99 seats, down from 166 in 2011, and now serve as the Official Opposition. The NDP won 44 seats, well above its historic average, but a significant decline from the 103 seats it won in 2011. The separatist Bloc Québécois won 10 seats and the Green Party retained a single seat.

Trudeau Government

The Liberal Party has advanced much of its policy agenda since taking office in November 2015. The Liberals had campaigned on a pledge to improve economic security for the middle class and quickly enacted a fiscal reform that raised taxes on the wealthiest Canadians while reducing them for middle income families. They also created a new child benefit that provides monthly payments to families to help them with the cost of raising children and negotiated with the provinces to gradually increase contributions to the Canada Pension Plan and thereby boost Canadians' pension benefits from one-quarter to one-third of their eligible earnings.4 The Trudeau government's 2018 budget proposal would increase paid parental leave benefits in an attempt to provide more flexibility to families and foster greater gender equality.5

Trudeau and the Liberals also campaigned on a series of political reforms. Most prominently, they pledged that the 2015 election would be the last to be conducted under the first-past-the-post electoral system. Although Trudeau established an all-party committee to examine the issue, he abandoned the electoral reform effort in early 2017.6 The Liberals have followed through on other changes to the political system, including the establishment of a nonpartisan, merit-based process to advise the prime minister on appointments to the Canadian Senate. The change was intended to transform the upper house, which had faced a series of ethics scandals, into a more reputable and collaborative body. Some observers have warned, however, that the growing independence of the unelected Senate could thwart the democratic process.7

On a number of other issues, the Liberals' attempts to balance competing policy priorities appear to have taken a toll on the party's support. For example, Trudeau has worked with Canada's provinces and territories to develop a national climate change plan that imposes a price on carbon emissions while also supporting the construction of new pipelines intended to link Canada's oil sands to overseas markets (see "Climate Change" and "Energy"). The Liberals' approach has drawn criticism from Canadian energy producers and other businesses as well as environmentalists and indigenous groups.8 In the coming months, the Liberals are expected to enact measures to legalize cannabis consumption and amend Canada's antiterrorism legal framework to clarify and expand agencies' authorities, increase transparency and oversight, and enhance civil liberties protections. Although the Liberals have carried out extensive consultations regarding the proposed changes, the tradeoffs involved could disappoint some Canadians who supported the party in the last election.

Trudeau enjoyed high levels of public support during his first year in office, but his approval rating has declined substantially since early 2017, averaging about 41% in recent polls.9 In addition to the policy disagreements discussed above, a series of Liberal Party ethics scandals appear to have tarnished Trudeau's image as someone who would bring a fresh approach to politics.10 In December 2017, for example, Canada's Ethics Commissioner ruled that Trudeau had contravened the country's Conflict of Interest Act by accepting two paid family vacations from a wealthy philanthropist whose foundation had received funding from the Canadian government.11 Trudeau also has begun to face more scrutiny from the political opposition. The Conservative Party elected Andrew Scheer, a 39-year-old Member of Parliament from Saskatchewan, as its new leader in May 2017, and the NDP elected Jagmeet Singh, a 39-year-old former Member of Ontario's Provincial Parliament, as its new leader in October 2017. According to an average of recent polls, 37.2% of Canadians support the Conservatives while 34.8% support the Liberals, 17.4% support the NDP, 6.1% support the Green Party, and 3.4% support the Bloc Québécois.12

Foreign and Security Policy

Canada views a rules-based international order as essential for enabled them to implement much of their campaign platform. During its first four years in office, the Liberal government enacted a tax cut for middle-income families, created a new child benefit to help with the cost of raising children, and increased

pension and parental leave benefits. The Liberal government also legalized cannabis consumption and worked with Canada’s provinces and territories to develop a national climate change plan that

imposed a price on carbon emissions.

Although Prime Minister Trudeau and the Liberals initial y enjoyed high levels of public support, their approval ratings gradual y declined as they abandoned some campaign pledges, such as electoral reform, and sought to balance competing policy priorities. For example, the Liberals enacted a carbon tax to reduce GHG emissions but also supported several pipeline projects to transport Canadian oil sands to overseas markets (see “Climate Change” and “Energy,” below);

those efforts to reconcile Canada’s Paris Agreement commitments with its role as a major fossil

fuel producer drew criticism from energy producers and environmentalists.

A series of ethics scandals further eroded public support for the Liberal government. In December

2017, Canada’s conflict of interest and ethics commissioner ruled that Prime Minister Trudeau had contravened the country’s Conflict of Interest Act by accepting two paid family vacations from a wealthy philanthropist whose foundation had received funding from the Canadian government.7 Prime Minister Trudeau was found to have contravened the act again in August 2019 for attempting to influence a decision of the attorney general of Canada regarding a

potential criminal prosecution of the Montreal-based engineering company SNC-Lavalin.8

2019 Election The Liberals entered the 2019 election campaign facing increased public scrutiny and polling neck and neck with the opposition Conservatives. With unemployment near a 40-year low, the Liberal Party highlighted its legislative accomplishments and argued the election was about whether or not Canada would “keep moving forward.”9 Many Canadians remained concerned about cost-of-living issues, however, and Conservative Party leader Andrew Scheer pledged to

help Canadians “get ahead.”10 He argued the Liberal government’s carbon tax had made necessities more expensive and claimed four years of deficit spending had failed to improve Canadians’ lives. The Liberal Party also faced pressure from its left, with the New Democratic Party (NDP) and the Green Party seeking to win over progressive voters disenchanted with Prime Minister Trudeau’s ethics violations and the Liberal Party’s lack of follow-through on some of its

more far-reaching 2015 campaign pledges.

In the end, the Liberals won 157 ridings, leaving the party 13 seats shy of a majority. The Liberal Party’s vote share declined in every province and territory compared with 2015. It lost 29 seats

7 Mary Dawson, Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, Trudeau Report, December 2017. 8 Mario Dion, Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, Trudeau II Report, August 2019. 9 Jason Kirby, “Election 2019 Primer: Jobs, the Economy and the Deficit,” Macleans, September 12, 2019; and Liberal Party of Canada, Forward: A Real Plan for the Middle Class, September 2019. 10 Bruce Anderson and David Coletto, “Election 2019 Is a Battle to Define the Agenda,” Abacus Data, July 15, 2019; and Conservative Party of Canada, “Andrew Scheer Launches Campaign to Help You Get Ahead,” September 11, 2019.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 8

Canada-U.S. Relations

across the country, including the party’s only footholds in the oil-producing provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Conservative Party won a plurality of al votes cast nationwide but failed to make significant gains in Quebec and Ontario, which hold nearly 60% of the seats in the House of Commons (see Figure 1). As a result, the Conservatives remain the Official Opposition, with 121 seats. The Bloc Québécois, which promotes Quebec sovereignty, surged to a third-place finish by winning 32 seats in the province. The Bloc’s gains came largely at the expense of the

NDP, which won 24 seats. The Green Party won three seats, and Prime Minister Trudeau’s former attorney general, who resigned after accusing the prime minister of inappropriate intervention in

the SNC-Lavalin case, won reelection to parliament as an independent.

Figure 1. Map of Canada’s 2019 Federal Election Results

Source: CRS. Data from Elections Canada, “Official Voting Results: Forty-Third General Election,” 2019.

Minority Government and Pandemic Response Prime Minister Trudeau has presided over a minority government since the start of the 43rd Parliament in December 2019. As the new term began, it appeared the government’s primary chal enge would be to develop policies that would further reduce Canada’s GHG emissions while

maintaining economic growth and addressing an increasing sense of political alienation in the country’s western oil-producing provinces.11 The Liberals’ other stated policy priorities included a new tax cut for middle-income families, more stringent gun controls, an expansion of Canada’s

11 Grant Wyeth, “How Climate Change Could T ear Canada Apart,” World Politics Review, February 13, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 9

Canada-U.S. Relations

universal health care system to cover prescription drugs, and reconciliation with indigenous

peoples.12

Many of those issues were set aside, however, with the onset of the Coronavirus Disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic. The Canadian government confirmed the first documented infection in the country on January 27, 2020, and recorded the first death from the disease on March 9, 2020. By late March 2020, the Trudeau government had closed Canada’s borders to most nonresidents and imposed a mandatory 14-day quarantine for individuals returning to the country. The federal government also coordinated with provincial and territorial governments—which have

jurisdiction over health care—to secure personal protective equipment and other medical supplies and to scale up the country’s testing and contact-tracing capabilities. The provinces and territories have imposed (and lifted) containment measures in accordance with local conditions and the

federal government’s broad public health guidelines.

Figure 2. Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 in Canada

(new cases by date reported [March 15, 2020-February 9, 2021])

Source: CRS, Data from Public Health Agency of Canada, “Public Health Infobase - Data on COVID-19 in Canada,” February 10, 2021.

Analysts credited those coordinated efforts for initial y slowing the spread of the virus (see Figure 2). Although provincial health services reportedly experienced some supply shortages, they had sufficient capacity to handle the first wave of infections.13 As conditions improved,

provincial and territorial governments implemented phased reopening plans that al owed children

12 Government of Canada, “Moving Forward T ogether: Speech from the T hrone to Open the First Session of the 43 rd Parliament of Canada,” September 5, 2019. 13 Marieke Walsh and Nathan Vanderklippe, “Provinces Compete for Critical Medical Supplies,” Globe and Mail, April 7, 2020; and Allen S. Detsky and Isaac I. Bogoch, “COVID-19 in Canada: Experience and Response,” Journal of the Am erican Medical Association (JAMA), vol. 324, no. 8 (August 25, 2020), pp. 743 -744.

Congressional Research Service

5

Canada-U.S. Relations

to return to school and loosened restrictions on many business and recreational activities. A second, larger wave of infections swept through Canada in late 2020, however, leading provinces to reimpose restrictions. As of February 9, 2021, Canada had registered nearly 811,000 cases and 21,000 deaths from COVID-19.14 The country’s COVID-19 daily case rate (9.4 new cases per 100,000 residents) was less than one-third of that of the United States (33 new cases per 100,000

residents).15

The Trudeau government has worked with Parliament to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic and public health measures. Among other programs, the government created the

Canada Emergency Response Benefit, which provided C$2,000 (approximately $1,538) every four weeks to workers who lost their incomes due to COVID-19, and the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy, which covered 75% of employees’ wages, up to C$847 (approximately $652) per week, for businesses that have lost a certain amount of revenue.16 The emergency response benefit original y was to provide up to 16 weeks of assistance, but the Canadian government extended the program to 28 weeks. In September 2020, beneficiaries began transitioning into a

newly expanded employment insurance system; self-employed and gig workers who do not qualify for employment insurance are eligible for a new C$500 (approximately $385) per week Canada Recovery Benefit until September 2021. The Canadian government also extended the

wage subsidy program, original y scheduled to expire in June 2020, through June 2021.17

Prime Minister Trudeau laid out a revised vision for his second term in September 2020, which was fleshed out in the government’s Fall Economic Statement 2020. The Liberal government’s top priorities are combatting the pandemic and helping Canadians through the crisis. Among other measures, Prime Minister Trudeau pledged to help provinces increase testing, ensure Canadians

have access to vaccines and therapeutics, and provide continued financial support to individuals and businesses affected by the pandemic and government containment measures. The Canadian government has signed agreements with seven vaccine suppliers for enough doses to vaccinate the Canadian population nearly six times over. Production delays have slowed distribution, however, and only 2.7% of the Canadian population had received at least one vaccine dose as of

early February (compared with 10.2% of the U.S. population).18

Following the immediate crisis, the Liberals argue Canada should take advantage of low interest rates to finance economic stimulus measures and address longer-term concerns, such as climate

change and gaps in Canada’s social assistance systems.19 The prime minister wil need to secure the support of opposition parties to enact his agenda. Although Erin O’Toole, the newly elected leader of the Conservative Party, has dismissed many of Prime Minister Trudeau’s proposals,

14 Government of Canada, Public Health Infobase, “Interactive Data Visualizations of COVID-19,” February 10, 2021. Data are updated regularly at https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/. 15 “COVID World Map: T racking the Global Outbreak,” New York Times, February 10, 2021. Data are updated regularly at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/coronavirus-maps.html.

16 Currency conversions throughout this report are based on the average exchange rate from September 14, 2020, to January 15, 2021, of C$1.3/U.S.$1. Data from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, “ Foreign Exchange Rates,” January 19, 2021. 17 Department of Finance Canada, “Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan,” September 28, 2020; and Canada Revenue Agency, “Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS),” November 23, 2020. 18 Government of Canada, “Procuring Vacines for COVID-19,” February 9, 2021; and “Canada Politics: Quick View – Vaccine Shortages Slow Rollout,” Economist Intelligence Unit, February 4, 2021. 19 Government of Canada, “A Stronger and More Resilient Canada: Speech from the T hrone to Open the Second Session of the 43rd Parliament of Canada,” September 23, 2020; and Department of Finance Canada, Supporting Canadians and Fighting COVID-19: Fall Econom ic Statem ent 2020, November 30, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 16 Canada-U.S. Relations

NDP leader Jagmeet Singh has indicated his party is prepared to provide political support to the

Liberal government as long as the government supports NDP priorities, such as paid sick leave.20

The Liberals wil need to maintain the NDP’s support or offset it with support from the Bloc

Québécois or the Conservative Party to avoid a snap election; recent minority governments have lasted just over two years, on average.21 Popular support for the Liberal Party initial y increased during the pandemic but declined somewhat after Canada’s conflict of interest and ethics commissioner launched an investigation in July 2020 into the government’s decision to award a contract to a charity with ties to the prime minister’s family.22 As of February 8, 2021, polls

suggested 35% of Canadians would support the Liberals in a new election, 30% would support the Conservatives, 18% would support the NDP, nearly 7% would support the Bloc Québécois,

and 6% would support the Green Party.23

Foreign and Defense Policy Canada views the rules-based international order that it helped establish with the United States and other al ies in the aftermath of World War II as essential to its physical security and economic

prosperity. According to Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland, who served as minister of foreign affairs from 2017 to 2019, “As a middle power living next to the world’s only super power, Canada has a huge interest in an international order based on rules. One in which might is not always right. One in which more powerful countries are constrained in their treatment of smal er ones by standards that are international y respected, enforced and

upheld.”24

Historical y, Canada has sought to increase its influence over the shape of the international order through multilateral diplomacy and contributions to collective security al iances. its physical security and economic prosperity. Historically, the country has sought to promote international peace and stability by leveraging its influence through alliance commitments and multilateral diplomacy.13 Although the Although the

Harper government broke with its predecessors to a certain extent, demonstratingexpressing more skepticism toward the United Nations and other international organizations, Prime Ministertoward multilateral institutions and a greater willingness to engage in unilateral actions, Trudeau has Trudeau has

restored Canada'’s traditional approach to foreign affairs.25

Over the past four years, much of Prime Minister Trudeau’s time and attention has focused on managing relations with the United States. Maintaining smooth bilateral relations is typical y a top priority for Canadian governments, since Canada depends on access to the U.S. market and benefits from U.S. investments in continental defense (see “U.S.-Canada Security Cooperation”). That task grew more difficult during the Trump Administration, however, which chal enged many

long-standing pil ars of the U.S.-Canada relationship. In addition to renegotiating NAFTA, President Trump raised doubts about the U.S. commitment to NATO and withdrew from multilateral institutions and agreements that both countries previously supported. Prime Minister Trudeau general y sought to avoid direct confrontations with the Trump Administration, but tensions boiled over on a few occasions. In June 2018, for example, President Trump and

20 Althia Raj, “Jagmeet Singh: NDP Could Prop Up Liberal Government for Another 3 Years,” HuffPost Canada, September 26, 2020.

21 Geoff Norquay, “Is Canada Headed T oward Another Minority Government?,” Policy Options, September 19, 2019. 22 “T he WE Charity Controversy Explained,” CBC News, July 28, 2020. 23 T hese vote projections are from a model that averages all publicly available opinion polls, weighted by age, sample size, and past performance of the polling firm. Éric Grenier, “ Poll T racker,” CBC News, February 8, 2021.

24 Global Affairs Canada, “Address by Minister Freeland on Canada’s Foreign Policy Priorities,” June 6, 2017. 25 John Ibbitson, The Big Break: The Conservative Transformation of Canada’s Foreign Policy, Centre for International Governance Innovation, CIGI Papers No. 29, April 2014.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 38 link to page 31 link to page 14 link to page 13 Canada-U.S. Relations

Administration officials made disparaging remarks about Trudeau after the prime minister announced his intention to impose retaliatory tariffs on U.S. goods in response to the Trump Administration’s decision to impose national security tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum (see

“Steel and Aluminum Tariffs,” below).26

U.S.-Canada relations have improved since the conclusion of USMCA negotiations, but many Canadians question whether the United States remains a reliable partner.27 The Trudeau government has sought to reduce Canada’s dependence on the U.S. market by concluding free trade agreements (FTAs) with the European Union and 10 countries in the Asia-Pacific region

(see “Canada’s Network of Free Trade Agreements,” below). Although the Trudeau government also explored a potential FTA with China, talks were suspended due to a sharp deterioration in

relations (see “Relations with China,” below).

Amid perceptions that the United States seeks to “shrug off the burden of global leadership,” the Trudeau government has sought to work with like-minded countries to uphold the rules-based international order.28 In 2019, for example, Canada joined a coalition of countries led by France and Germany to launch the Al iance for Multilateralism—an informal network that seeks to protect and preserve international norms, agreements, and institutions; address new chal enges

that require collective action; and reform multilateral institutions and agreements to ensure they deliver tangible results to citizens. Canada also is leading a smal coalition of World Trade Organization (WTO) members, known as the Ottawa Group, to reform the multilateral trading

system.

As part of its broader efforts to uphold the rules-based order, the Trudeau government has reaffirmed Canada’s commitment to collective security efforts. It unveiled a new defense policy in 2017, which asserts that defending Canada and Canadian interests “not only demands robust domestic defense but also requires active engagement abroad.”29 Among other deployments,

Canada is contributing to the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq and to NATO’s deterrence operations in Eastern Europe (see “NATO Commitments”). Although Prime Minister Trudeau pledged to increase Canada’s support for U.N. peacekeeping missions, his government’s contributions have been fairly limited, with the exception of a 13-month deployment of a 250-member air task force to Mali.30 Some analysts have linked Canada’s failed bid for a temporary seat on the U.N. Security Council for the 2021-2022 term, in part, to the country’s comparatively smal

contributions to global peacekeeping and development efforts.31

26 Michael D. Shear and Catherine Porter, “Trump Refuses to Sign G-7 Statement and Calls T rudeau ‘Weak,’” New York Tim es, June 9, 2018; and Patrick T emple-West, “ White House Ratchets Up T rade War with ‘Special Place in Hell’ Slug at T rudeau,” Politico, June 10, 2018. 27 Jamie Gillies and Shaun Narine, “T he T rudeau Government and the Case for Multilateralism in an Uncertain World,” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, vol. 26, no. 3 (2020), pp. 257-275; Richard Nimijean and David Carment, “Rethinking the Canada-U.S. Relationship After the Pandemic,” Policy Options, May 7, 2020; and Steven Chase, “More Canadians Hold an Unfavourable View of the U.S. T han at Any Point Since Sentiment Was First T racked, Poll Indicates,” Globe and Mail, October 15, 2020.

28 Global Affairs Canada, “Address by Minister Freeland on Canada’s Foreign Policy Priorities,” June 6, 2017. 29 Department of National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy, June 2017, p. 14. 30 Department of National Defence, “Canadian Armed Forces Conclude Peacekeeping Mission in Mali,” press release, August 31, 2019; and Mike Blanchfield, “Canada’s Peacekeeping Contribution at Lowest Level in More T han 60 Years,” Globe and Mail, May 23, 2020. 31 Bruno Charbonneau and Christian Leuprecht, “When Will Canada Hear the Message the UN Keeps Sending Us?,” Globe and Mail, June 19, 2020; and “ Canada Loses Out on UN Security Council Seat Bid,” Econom ist Intelligence Unit, June 30, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

8

Canada-U.S. Relations

NATO Commitments s traditional approach to foreign affairs.14 His government quickly reemphasized multilateral engagement by ratifying the Paris Agreement on climate change and announcing Canada's bid for a temporary seat on the U.N. Security Council for the 2021-2022 term. In June 2017, Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland asserted that Canada must set its "own clear and sovereign course" to renew and strengthen the international order given that the United States appeared to be withdrawing from its global leadership role.15 President Trump's actions at the June 2018 Group of Seven (G-7) meeting have reinforced Canadian concerns about the U.S. government's commitment to the rules-based, multilateral system (see text box below).

The Trudeau government also has reaffirmed Canada's support for international security efforts. It unveiled a new defense policy in June 2017, which asserts that as a result of changes in global security dynamics, defending Canada and Canadian interests "not only demands robust domestic defense but also requires active engagement abroad."16 Under the new policy, Canada will increase defense spending by 73% in nominal terms over the next decade from C$18.9 billion (about $14.6 billion) in 2016-17 to C$32.7 billion (about $25.2 billion) in 2026-2027. The additional resources will be used to acquire new aircraft, ships, and other equipment; expand the Canadian Armed Forces by 3,500 personnel; and invest in new capabilities.17

The annual G-7 summit of leading industrial democracies (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) this year was held in Charlevoix, Quebec, on June 7-8, 2018. Usually placid affairs where leaders reaffirm their commitment to the western alliance, free trade, and international institutions, at this year's summit President Trump criticized the trade policies of the other six nations, as well as their levels of defense spending. The other six nations responded in kind with criticism of the Administration's steel and aluminum tariffs, potential additional tariffs on vehicles, and, implicitly, U.S. climate change policy. As host, Prime Minister Trudeau sought to devote the summit to issues such as promoting inclusive economic growth, combating extreme nationalism, fostering gender equity, and protecting the environment. While initially agreeing on the final communiqué, President Trump withdrew U.S. support after leaving the summit, calling Trudeau "weak and dishonest" after the Prime Minister called U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs "insulting" and vowed reciprocal tariffs. Some of the disagreements included the following:

|

NATO Commitments

Canada, like the United States, was a founding member of NATO in 1949. It maintained a Canada, like the United States, was a founding member of NATO in 1949. It maintained a

military presence in Western Europe throughout the Cold War in support of the collective defense pact. Since the 1990s, Canada has supported efforts to restructure NATONATO’s adaptation and has been an active participant in a number ofnumerous NATO operations, including the 1992 intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the 1999 bombing campaign in Serbia, and the 2011 intervention in Libya. Canada also contributed the fifth-largest national contingent to the NATO-led International Security

Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, before withdrawing in 2014.

Canada was an advocate for NATO enlargement,

Canada commanded NATO Mission Iraq from its October 2018 inception until November 2020. The mission aims to strengthen Iraqi security institutions and forces by providing noncombat

advisory, training, and capacity-building support to Iraqi defense officials and military personnel. Those efforts complemented Canada’s broader contributions to the U.S.-led coalition to defeat the Islamic State. Although Prime Minister Trudeau withdrew Canada’s fighter aircraft from Iraq shortly after taking office, he has deployed up to 850 troops to the Middle East to support coalition air operations; provide intel igence support; and train, advise, and assist Iraqi security

forces.32 Canada and other NATO and coalition partners have repositioned many personnel outside of Iraq since early 2020 due to a deterioration in the security situation and the COVID-19 pandemic.33 Although some troops may return to the Middle East once conditions improve,

Canada intends to reduce its overal presence in the region.34

Canada has been an advocate for NATO enlargement and has deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel to Central and Eastern Europe in support of the newest members of the allianceal iance. In June 2017, Canada took command of a 1,000-strong NATO battle group deployed to Latvia to enhance the alliance's forward presence as part of the al iance’s Enhanced Forward Presence in Eastern Europe. The 1,500-strong battle group includes 450

540 members of the Canadian Armed Forces, as well wel as troops from Albania, Italythe Czech Republic, Italy, Montenegro, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. The United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany are commandingcommand similar forces in Poland, Estonia, and Lithuania, respectively, as part of a broader effort to reassure the alliance'al iance’s eastern members and bolster deterrence in the aftermath of Russia's annexation of Crimea and incursion into Ukraine. Canada also has deployed a maritime task force of one frigate to the Eastern Mediterranean to support NATO activities.18

Under the Trudeau government's new defense policy, Canada's total defense spending would reach 1.4%’s annexation of Crimea. Canada also commands a standing NATO maritime

group that operates in Western and Northern European waters.35

Under the Trudeau government’s defense policy, Canada is to increase defense spending by 73% in nominal terms over 10 years to reach C$32.7 bil ion (approximately $25.2 bil ion) in 2026-

2027. Canada intends to use the additional resources to acquire new aircraft, ships, and other equipment; expand the Canadian Armed Forces by 3,500 personnel; and invest in new capabilities.36 If implemented, Canada’s total defense spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) would reach 1.4% in 2024-2025, which would fall fal wel short of NATO's recommended level of at least 2% of GDP. Nevertheless, Canada would exceed NATO'’s

32 Department of National Defence, “Operation IMPACT ,” December 15, 2020; and NAT O, “NAT O Mission Iraq,” October 29, 2020.

33 NAT O and other coalition operations were suspended temporarily in January 2020 following the U.S. killing of Qasem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, and subsequent Iranian missile attacks against Iraqi bases hosting U.S. and coalition forces. Following the U.S. strike against Soleimani, Iran shot down a civilian aircraft, killing all 176 people aboard, including 55 citizens and 30 permanent residents of Canada. 34 Lee Berthiaume, “Canadian Military Shrinks Middle East Footprint as ISIL Fight Enters New Phase,” Canadian Press, July 29, 2020.

35 Department of National Defence, “Operation REASSURANCE,” January 18, 2021; and NAT O, “NAT O’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” fact sheet, October 2019. 36 Department of National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy, June 2017, p. 13.

Congressional Research Service

9

Canada-U.S. Relations

recommended level of at least 2% of GDP. Nevertheless, Canada would exceed NATO’s target of investing 20% of defense expenditure in major equipment; such investments would reach 32% of

defense spending in 2024-2025.19 Although successive U.S. Administrations have pushed Canada to meet the 2% of GDP target, Canada has long maintained that defense expenditure as a percentage of GDP is not a good measure for determining actual military capabilities or contributions to the NATO alliance.

Participation in Coalition to Combat the Islamic State20

Canada has supported the U.S.-led military campaign against the Islamic State since September 2014. Prime Minister Trudeau followed through on a campaign pledge to "end Canada's combat mission" by withdrawing six CF-18s, which had conducted 251 airstrikes in Iraq and Syria.21 Nevertheless, Canada has continued to support coalition air operations with its refueling and tactical airlift aircraft. Canada is also training, advising, and assisting Iraqi security forces, providing intelligence support to identify Islamic State targets and protect coalition forces, and operating a medical facility that serves as a hub for coalition forces in northern Iraq.22 In June 2017, the Trudeau government announced that Canada would continue to support coalition operations through March 2019, and authorized the deployment of up to 850 Canadian Armed Forces personnel.23

The Trudeau government has sought to complement Canada's military operations with political and humanitarian efforts in the region. It has pledged to provide C$1.6 billion (about $1.2 billion) in security, stabilization, humanitarian, and development assistance over three years to address the crises in Iraq and Syria as well as their impact on Jordan and Lebanon.24 The Trudeau government also has sought to assist those who have been displaced by the conflict, resettling nearly 53,000 Syrian refugees between November 2015 and March 2018.25 Nearly 1,000 Yazidis and other survivors of Islamic State violence were resettled in Canada in 2017.26

U.S.-Canada Defense Relations

According to the U.S. State Department, "U.S. defense arrangements with Canada are more extensive than with any other country."27 There reportedly are more than 800 agreements in place that govern the day-to-day defense relationship.28 The Permanent Joint Board on Defense, established in 1940 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Mackenzie King, is the highest-level bilateral defense forum between the United States and Canada. It is composed of senior military and civilian leaders from both countries and provides policy-level consultation and advice on continental defense matters.

NORAD

NORAD is a cornerstone of U.S.-Canadian defense relations. Established in 1958, NORAD originally was intended to monitor and defend North America against Soviet long-range bombers. The NORAD agreement has been reviewed and revised several times, however, to respond to changes in the international security environment. Today, NORAD's mission consists of

- Aerospace Warning: processing, assessing, and disseminating intelligence related to the aerospace domain and detecting, validating, and warning of attacks against North America whether by aircraft, missiles, or space vehicles;

- Aerospace Control: providing surveillance and exercising operational control over U.S. and Canadian airspace; and

- Maritime Warning: processing, assessing, and disseminating intelligence related to the maritime areas and internal waterways of the United States and Canada, and warning of maritime threats to North America to enable response by national commands.

NORAD uses a network of satellites, ground-based radars, and aircraft to fulfill this mission.

NORAD is the only binational command in the world. The U.S. Commander and the Canadian Deputy Commander of NORAD are appointed by, and responsible to, both the U.S. President and the Canadian Prime Minister. Likewise, NORAD headquarters at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado is composed of integrated staff from both countries. About 300 Canadian Armed Forces personnel are stationed in the United States in support of the NORAD mission, including nearly 150 at NORAD headquarters.29 This binational structure allows the United States and Canada to pool resources, avoiding duplication of some efforts and increasing North America's overall defense capabilities. Nevertheless, since the U.S. and Canadian governments want to maintain their abilities to take unilateral action, some NORAD responsibilities and authorities overlap with those of U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM) and Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC).

The Permanent Joint Board on Defense reportedly has tasked NORAD with conducting a study on the evolution of North American defense. The study will reportedly examine the air, maritime, cyber, aerospace, outer space, and land threats to North America and the capabilities, command structures, and processes necessary to defeat them.30 Some officials within NORAD reportedly think that NORAD's mission should be expanded to include additional domains, and that NORAD, NORTHCOM, and CJOC should be integrated into a single binational command charged with the defense of the United States and Canada. They maintain that the creation of a unified command and control structure would improve the efficiency and effectiveness of North American defense efforts. Others are opposed to such changes, citing sovereignty concerns and coordination and interoperability challenges.31 During their February 2017 meeting at the White House, President Trump and Prime Minister Trudeau agreed to modernize and broaden the NORAD partnership in the air, maritime, cyber, and space domains.32

Ballistic Missile Defense

Canada has long debated whether it should participate in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system. Facing domestic political opposition and concerns that the system could trigger a new arms race or lead to the militarization of space, Canada opted not to participate in 2005. Some analysts argue that Canada should reconsider its position. They note that Canada has embraced ballistic missile defense as a means of protecting allied countries by signing off on NATO's 2010 Strategic Concept, which endorsed a territorial ballistic missile defense system in Europe. They also note that, contrary to the assumption that the United States would defend Canada in the event of a ballistic missile attack, current U.S. policy is not to use the U.S. ballistic missile defense system on Canada's behalf. Others argue that Canadian participation in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system should be assigned a relatively low priority within Canada's limited defense budget given the need to carry out several large-scale acquisitions to replace core Canadian Armed Forces equipment and systems in the coming years.33

The Trudeau government reexamined Canadian participation in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system as part of its defense policy review, but opted not to pursue a change in policy.34 Although Canada does not participate in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system directly, Canadian personnel, through their participation in NORAD, are involved in the detection of ballistic missiles, and a 2004 agreement permits NORAD to share information with NORTHCOM, which is responsible for the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.35

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Program36

Canada is one of nine countries that have participated in the U.S.-led F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program since 1997.37 The Canadian government reportedly has invested more than $400 million in the program, and Canadian industry has secured more than $1 billion in contracts as a result of Canada's participation.38 In 2010, the Harper government announced that Canada would acquire 65 Lockheed Martin F-35s to replace the country's aging fleet of 76 CF-18s, which have been flying since the 1980s. The plans became politically controversial, however, amid accusations that the government had misled the public about the cost and performance of the aircraft. In 2012, the Harper government put the procurement process on hold to review the plans and explore alternatives.

During the 2015 electoral campaign, Trudeau vowed to pull out of the F-35 program, open a competitive procurement process for "more affordable" fighters, and invest the savings in the Royal Canadian Navy.39 Nevertheless, the Canadian government has continued to make the annual payments required to remain in the Joint Strike Fighter program and has not ruled out ultimately purchasing the F-35s. Canada's Department of National Defense reportedly expects to open a new competitive process in early 2019.40

Defense Minister Harjit Sajjan has warned that the delay in purchasing the new aircraft could lead to a growing "capability gap" between Canada's NORAD and NATO commitments and the number of fighters available for operations.41 The Trudeau government proposed purchasing 18 new Boeing F/A-18 Super Hornets to supplement the current fleet of CF-18s on an interim basis but reversed the procurement decision after Boeing successfully petitioned the U.S. Department of Commerce to impose antidumping and countervailing duty actions against Bombardier Aircraft of Canada for unfair trade practices in April 2017 (see "Commercial Aircraft"). Instead, Canada opted to purchase 18 used F/A-18s from Australia. Many defense analysts have questioned the decision, noting that the F/A-18s will require costly modifications and maintenance following delivery and lack the capabilities of more modern aircraft, potentially jeopardizing interoperability with the United States and other allies.42

Border Security

The United States and Canada maintain a close intelligence partnership and coordinate frequently on law enforcement efforts, with a particular focus on securing the border since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Under the Beyond the Border declaration, signed in 2011, both nations agreed to negotiate on information sharing and joint threat assessments to develop a common and early understanding of the threat environment; infrastructure investment to accommodate continued growth in legal commercial and passenger traffic; integrated cross-border law enforcement operations; and coordinated steps to strengthen and protect critical infrastructure.43 The declaration led to a 2016 accord to exchange 37

In 2020, partial y due to the sharp economic downturn, Canada’s estimated defense expenditures reached approximately 1.45% of GDP, with 17.4% of expenditures dedicated to equipment.38 Although the pandemic-driven economic downturn could put pressure on Canada’s defense budget, Defense Minister Harjit Saj an maintains that expenditures are moving forward as planned.39 Successive U.S. Administrations have pushed Canada to meet the NATO target, but

Canada has long argued that countries’ contributions to the al iance should be measured more by the capabilities and troops they provide than by their defense expenditures as a percentage of

GDP.

Relations with China Prime Minister Trudeau’s government came to office intending to strengthen ties with China. It argued that deeper commercial ties with China were necessary to increase Canada’s long-term economic growth and diversify the country’s trade relations. The United States is the destination

of about 73% of Canada’s global merchandise exports,40 and the Trump Administration’s trade policies reinforced long-standing concerns that Canada is overly dependent on the U.S. market. During Prime Minister Trudeau’s first years in office, Canada joined the China-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and al owed Chinese companies to acquire some Canadian businesses in sensitive sectors.41 Canada also increased its diplomatic engagement with China and

engaged in exploratory discussions regarding an extradition treaty and an FTA.42

Chinese-Canadian relations have deteriorated significantly since December 2018, when Canada arrested Meng Wanzhou, an executive at the Chinese technology company Huawei, to comply

with an extradition request from the United States. A trial to determine whether Meng is to be extradited to the United States has been underway since January 2020. The U.S. Department of Justice indicted Meng and Huawei for financial fraud involving violations of U.S. sanctions on Iran.43 In apparent retaliation for Meng’s arrest, China detained two Canadians, Michael Kovrig, a former diplomat, and Michael Spavor, in December 2018. China has held the men in state custody for over two years, charging them with espionage in June 2020.44 China also restricted

imports of certain Canadian agricultural products. Although Chinese officials maintain that Canada must ensure Meng’s safe return to China to avoid further damage to bilateral relations,

37 Department of National Defence, Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy, June 2017. p. 46. 38 NAT O, “Defence Expenditure of NAT O Countries (2013 -2020),” Communique PR/CP(2020)104, October 21, 2020. 39 Lee Berthiaume, “Hundreds of Billions of Planned Military Spending ‘Secure’ Despite COVID-19: Sajjan,” Canadian Press, September 15, 2020.

40 Statistics Canada data, as presented by Trade Data Monitor, accessed February 2021. 41 For more on the bank, see CRS In Focus IF10154, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, by Martin A. Weiss. 42 Preston Lim, “Sino-Canadian Relations in the Age of Justin T rudeau,” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, vol. 26, no. 1 (2020).

43 U.S. Department of Justice, “Chinese T elecommunications Conglomerate Huawei and Huawei CFO Wanzhou Meng Charged with Financial Fraud,” press release, January 28, 2019. 44 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s Regular Press Conference,” June 19, 2020; and Global Affairs Canada, “ T wo Years Since Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor Arbitrarily Detained in China,” December 9, 2020.

Congressional Research Service

10

Canada-U.S. Relations

Prime Minister Trudeau has criticized China’s “coercive diplomacy” and demanded the release of

the incarcerated Canadians.45

The Trump Administration praised Canada for honoring the extradition treaty and upholding the

rule of law and cal ed on China to end its “arbitrary detention of Canadian citizens.”46 The Senate and the House passed resolutions (S.Res. 96 and H.Res. 521, respectively, 116th Congress) expressing similar sentiments in 2019. Canadian officials expressed some frustrations, however,

that the Trump Administration did not push more forcefully for the Canadians’ release.47

Tensions have escalated as Canada has pressed China on human rights issues. In May 2020, Canada joined with the United States, the United Kingdom (UK), and Australia to express “deep concern” about China’s decision to impose a new national security law on Hong Kong.48 Since then, Canada has suspended its extradition treaty with Hong Kong, placed restrictions on

sensitive exports to Hong Kong, granted asylum to some Hong Kong democracy activists, and

created a new class of work permit for Hong Kong residents.

Canadian officials also have expressed concerns about China’s treatment of Uyghurs and other

ethnic minorities in northwest China’s Xinjiang region. In October 2020, the House of Commons Subcommittee on International Human Rights asserted that the situation amounts to genocide and cal ed on the Canadian government to impose sanctions on the Chinese officials responsible.49 The Trudeau government has opted not to impose sanctions thus far, but it announced a series of measures in January 2021 intended to prevent goods produced through forced labor in Xinjiang

from entering Canadian supply chains.50 The Chinese government has pushed back, urging Canada to “stop interfering in China’s internal affairs.”51 Human rights groups and Canadian officials maintain that Chinese government agents also have been directly and indirectly involved

in harassment and intimidation against pro-democracy and human rights activists in Canada.52

The deterioration in relations could influence the Trudeau government’s decision regarding whether to al ow Huawei to participate in Canada’s fifth-generation (5G) telecommunications network. The Trump Administration argued that using Huawei equipment would leave Canada’s network vulnerable to espionage and sabotage, since the company ultimately answers to the

Chinese government—a charge Huawei denies. Several of Canada’s top telecommunications companies use Huawei equipment in their existing networks and are concerned that excluding the