The Current State of Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform and Management

Changes from June 8, 2018 to July 10, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The Current State of Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform and Management

Contents

- Introduction

- FITARA Overview

- Applicability of FITARA

- FITARA Implementation

- The Impact of FITARA on Federal IT Management

- The Data Center Optimization Initiative

- May 2018 GAO DCOI Report

- The Cloud First Initiative

- IT Dashboard

- Portfolio Review

- TechStat

- PortfolioStat

- Oversight of Federal CIO Initiatives

- Congressional Oversight,

115116th Congress - Legislation

- Hearings

- Government Accountability Office Reports and Testimony,

2016-20172019

- Recent Activity: FITARA Scorecard

68.0- CIO Responsibilities

- CIO IT Acquisition Review

- Consolidating Data Centers

.0 - Consolidating Data Centers

- CIO Responsibilities

- IT Contract Approval

- Managing Software Licenses

- Improving the Security of Federal IT Systems

Figures

- Figure 1.

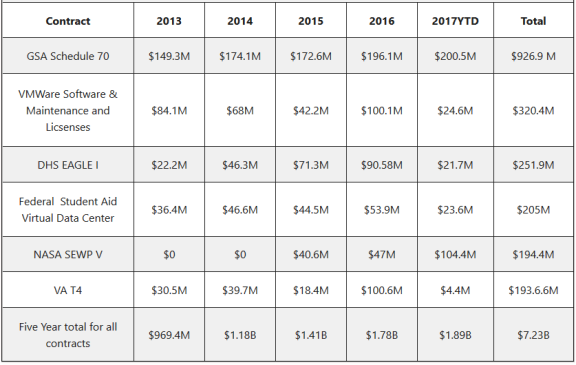

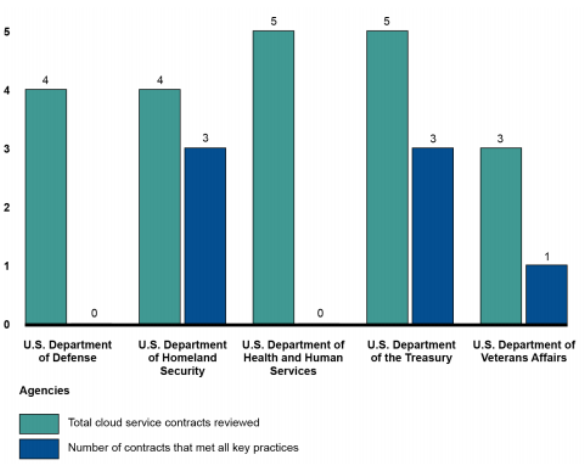

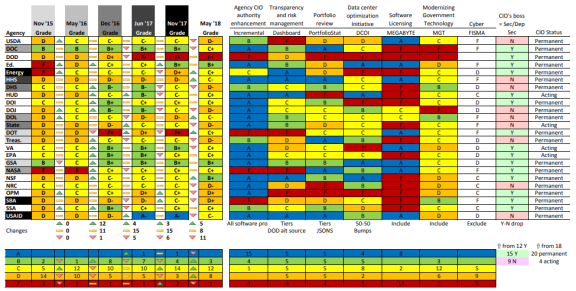

Agency Cloud Spending, FY2013-FY2017 Figure 2. Number of Cloud Service Contracts That Met All 10 Key Practices atPractices that Selected Agencies Used to Effectively Implement Key Provisions of FITARA- Figure 2. FITARA 8.0 Scorecard, June 2019

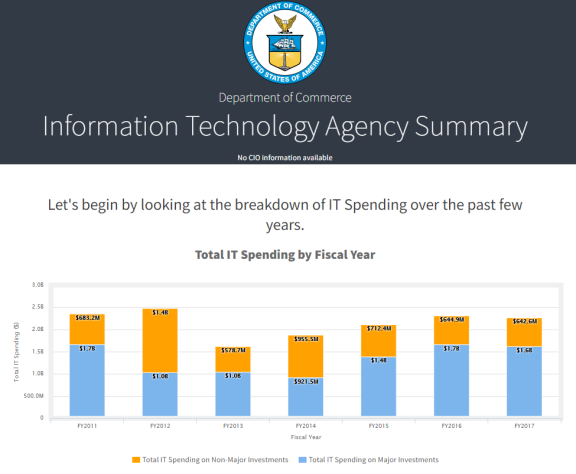

Selected Agencies- Figure 3. Example of an Agency Portfolio Page on OMB's IT Dashboard

- Figure 4. FITARA 6.0 Scorecard, May 2018

Summary

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported that the federal government budgets more than $80 billion each year on information technology (IT) investments and in FY2017, GAO estimates that this investment will increase to more than $89 billion. Historically, the projects supported by these investments have often incurred "multi-million dollar cost overruns and years-long schedule delays." In addition, GAO has reported that these projects may contribute little to mission-related outcomes and, in some cases, may fail altogether. These undesirable results, according to GAO, "can be traced to a lack of disciplined and effective management and inadequate executive-level oversight."

The Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) was enacted on December 19, 2014, to establish a long-term framework through which federal IT investments could be tracked, assessed, and managed, to significantly reduce wasteful spending and improve project outcomes. These requirements of FITARA are carried out by the Federal Chief Information Officer (CIO). The position of the Federal CIO was created by the E-Government Act of 2002 as the "Administrator, Office of Electronic Government."

Congress and GAO have actively monitored the activities of the Federal CIO and the initiatives carried out by the office. Both have been especially attentive to the topics of data center use and cloud deployment as they relate to achieving the goals of FITARA.

Two pairs of companion bills related to FITARA have been signed into law in the 115th Congress, the Modernizing Government Technology Act of 2017 (MGT Act) (H.R. 2227, S. 990, P.L. 115-91) and the FITARA Enhancement Act of 2017 (H.R. 3243, S. 1867, P.L. 115-88). Additionally, the House has held four hearings related to FITARA.

Introduction

The federal government spends more than $80 billion each year on information technology (IT) investments; in FY2017 that investment is expected to increase to more than $89 billion.1 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that, historically, the projects supported by these investments have often incurred "multi-million dollar cost overruns and years-long schedule delays." In addition, they may contribute little to mission-related outcomes and, in some cases, may fail altogether.2 These undesirable results, according to GAO, "can be traced to a lack of disciplined and effective management and inadequate executive-level oversight."3 The Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) was enacted on December 19, 2014,4 to address these issues5 and codify existing initiatives managed by the Federal Chief Information Officer (CIO).6

FITARA Overview

FITARA outlinesoutlined seven areas of reform that affect how federal agencies purchase and manage their information technology (IT) assets, including the following:

- enhancing the authority of agency CIOs;

- improving transparency and risk management of IT investments;

- setting forth a process for agency IT portfolio review;

- refocusing the Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative (FDCCI) from only consolidation to optimization;

- expanding the training and use of "IT Cadres," as initially outlined in the "25 Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal Information Management Technology";7

- maximizing the benefits of the Federal Strategic Sourcing Initiative (FSSI);8 and

- creating a

govemmentgovernment-wide software purchasing program, in conjunction with the General Services Administration.

Among other provisions, FITARA codified elements of existing Federal CIO initiatives. In addition, FITARA requires the Federal CIO, in conjunction with federal agencies, to

- refocus the Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative (FDCCI) from consolidation to optimization, to include adoption of cloud services;9

- set forth a process for agency IT portfolio review and oversight;

- improve transparency and risk management of IT investments;

- identify and publish cost savings and optimization improvements;

- provide public updates on cumulative cost savings and optimization improvements; and

- review agencies' data center inventories and management strategies.

FITARA requires federal agencies to submit annual reports that include

- comprehensive data center inventories,

- multiyear strategies to consolidate and optimize data centers,

- performance metrics and a time line for agency action, and

- yearly calculations of investment and cost savings related to FITARA implementation.

Applicability of FITARA

Generally, agencies identified in the Chief Financial Officers (CFO) Act of 1990,10 as well as their subordinate divisions and offices, are subject to the requirements of FITARA. The DOD, the intelligence community, and portions of other agencies that operate systems related to national security are subject to only certain portions of FITARA. Additionally, executive branch agencies not named in the CFO Act are encouraged, but not required, to follow FITARA guidelines.

FITARA Implementation

On June 10, 2015, OMB published guidance11 to implement the requirements of FITARA and harmonize existing policy and guidance12 with the new law. Among other goals, the requirements are intended to

- assist agencies in establishing management practices that align IT resources with agency missions, goals, programmatic priorities, and statutory requirements;

- establish government-wide IT management controls that will meet FITARA requirements while providing agencies with the flexibility to adapt to agency processes and unique mission requirements;

- establish universal roles, responsibilities, and authorities of the agency CIO and other senior agency officials;13

- strengthen the agency CIO's accountability for the agency's IT costs, schedules, performance, and security;

- strengthen the relationship between agency and bureau CIOs;

- establish consistent government-wide interpretation of FITARA terms and requirements; and

- provide appropriate visibility and involvement of the agency CIO in the management and oversight of IT resources to support the implementation of effective cybersecurity policies.14

In addition to implementing FITARA, the guidance also harmonizes the requirements of FITARA with existing law, primarily the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 and the E-Government Act of 2002.15 Those laws require OMB to issue management guidance for information technology and electronic government activities across the government, respectively. FITARA also contains provisions that required OMB interpretation before implementation.

The Impact of FITARA on Federal IT Management

FITARA provided the framework to refine existing CIO initiatives, mainly the Data Center Optimization Initiative, the Cloud First Policy, the IT Dashboard, and Portfolio Review.

The Data Center Optimization Initiative

On August 1, 2016, OMB released a new Data Center Optimization Initiative (DCOI)16 to supersede the Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative (DCCI)17 established in 2010. The DCOI requires agencies to develop and report on data center strategies to

- consolidate inefficient federal IT infrastructure;

- optimize existing facilities;

- improve security posture;

- achieve cost savings; and

- transition to more efficient infrastructure, such as cloud services and interagency shared services.

One of the most significant elements of the DCOI is that, beginning in February 2017, agencies are prohibited from budgeting funds or committing resources to establish any new data centers or significantly expand existing data centers without approval from the Federal CIO.18

The DCOI maintains the previous DCCI requirement that agencies increase the use of pooling of storage, network and computer resources, and of on-demand dynamic allocation ("virtualization"). Additionally, agencies will be required to evaluate their options and priorities for the consolidation and closure of existing data centers by transitioning to

- cloud-based services to the extent possible;19

- interagency shared services or colocated data centers; and

- optimized data centers within an agency's data center inventory.

The initiative also requires that agencies automate the tools used to measure power efficiency and manage their data center infrastructure, as well as classify their data centers as either "tiered" or "nontiered." Tiered data centers are defined as those using the following:

- a separate physical space for IT infrastructure,

- an uninterruptible power supply,

- a dedicated cooling system or zone, and

- a back-up power generator for prolonged power outages.

All other data centers will be considered nontiered data centers.20 Nontiered data centers are considered less secure than tiered data centers.

Under the new DCOI guidance, by the end of FY2018, agencies are required to close at least 25% of their tiered data centers (excluding interagency shared services data centers) and at least 60% of nontiered data centers. The DCOI guidance encourages agencies to prioritize closing those data centers that cannot achieve the required energy consumption optimization targets and/or present security challenges due to age.

To measure compliance with the DCOI, agencies are required to report on a quarterly basis

- inventories of all data center facilities, closure/consolidation plans, and properties of each facility owned, operated, or maintained by or on behalf of the agency;

- progress toward meeting all optimization metric target values; and

- evaluation of the costs of operating and maintaining current facilities, to include yearly targets for cost savings and cost avoidance due to consolidation and optimization through FY2018.

May 2018 GAO DCOI Report

In 2016 and 2017, GAO made a number of recommendations to OMB and the 24 DCOI agencies to help improve the reporting of data center-related cost savings and to achieve optimization targets. As of March 2018, 74 of these 81 recommendations had not been fully addressed. The May report included information about agencies' progress in three areas: OMB's data center closure targets, OMB's goals for planned savings, and OMB's data center optimization metrics.

Data Center Closure Targets

Despite the DCOI mandate to close a certain percentage of data centers by the end of FY2018, GAO found that the 24 agencies participating in the DCOI reported mixed progress toward achieving that goal. Over half of the agencies reported that they had either already met, or planned to meet, all of their OMB-assigned goals by the deadline, resulting in the closure of 7,221 of the 12,062 centers that agencies reported in August 2017. However, four agencies reported that they do not have plans to meet all of their assigned goals and two agencies are working with OMB to establish revised targets.

Goals for Planned Savings

With regard to agencies' progress in achieving cost savings, 20 agencies reported that they had achieved $1.04 billion in cost savings during FY2016 and FY2017. In addition, agencies' DCOI strategic plans identified an additional $0.58 billion in planned savings for a total of $1.62 billion for FY2016 through FY2018. This total is about $1.12 billion less than OMB's DCOI savings goal of $2.7 billion. This shortfall is due to 12 agencies reporting less in planned cost savings and avoidances in their DCOI strategic plans, as compared to the savings targets established by OMB.

Data Center Optimization Metrics

Participating agencies reported limited progress against OMB's five targets for server utilization and automated monitoring; energy metering; power usage effectiveness; facility utilization; and virtualization. As of August 2017, only one agency had met four targets, one agency had met three targets, six agencies had met either one or two targets, and 14 agencies reported meeting no targets. Further, most agencies were not planning to meet OMB's FY2018 optimization targets.

The Cloud First Initiative

In addition to providing updated guidance to agencies regarding their data centers, the DCOI has also provided new guidance for cloud investment and shared services adoption. This new guidance complements guidance provided in the Federal Cloud Computing Strategy, which was published in February 2011.21 The strategy instituted the Cloud First policy, requiring agencies to evaluate cloud computing options before making new investments in physical IT infrastructure. It is intended to accelerate the adoption of cloud computing services by federal agencies and, therefore, the pace at which the government may realize the benefits of cloud adoption (Table 1).

In April 2016, GAO reported an assessment of how well agencies have incorporated 10 key management elements into their cloud computing service level agreements (SLAs) (Table 2).22 The SLA is part of a standardized service contract in which particular aspects of the service, such as scope, quality, and responsibilities, are defined and agreed upon between the service provider and the service user. With respect to SLA key practices, GAO analyzed 21 cloud service contracts and related documentation of the five agencies with the largest FY2015 IT budgets—the Departments of Defense (DOD), Health and Human Services (HHS), Homeland Security (DHS), the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs (VA).

GAO found that the contracts reviewed included a majority of the 10 key practices: 7 contracts fulfilled all key practices, 13 had incorporated five or more, and 1 did not include any (Figure 2). Agency officials gave several reasons why all elements of the key practices had not been included into their cloud service contracts, including that guidance directing the use of the practices had not been created when the cloud services were acquired. GAO noted that until agencies fully incorporate the SLA key practices into their contracts, they may be unable to adequately measure the performance of the services provided, and thus be unable to hold service providers accountable for poor performance.

|

Efficiency |

|

|

Cloud Benefits |

Legacy Environment |

|

|

|

Agility |

|

|

Cloud Benefits |

Legacy Environment |

|

|

|

Innovation |

|

|

Cloud Benefits |

Legacy Environment |

|

|

Source: U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Federal Cloud Computing Strategy February 8, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/egov_docs/federal-cloud-computing-strategy.pdf.

In accordance with the Cloud First policy, FITARA, and guidance from the National Institute for Standards and Technology, the new DCOI requires agencies to use cloud infrastructure where possible when planning new applications or consolidating existing applications. Agencies are encouraged to take into consideration the cost, security requirements, and application needs when evaluating cloud services.

In light of its findings, GAO recommended that

- OMB include the 10 key practices in future guidance to agencies, and

- the Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, the Treasury, and Veterans Affairs incorporate the key practices into their SLAs.

Four of the agencies—DOD, DHS, HHS, and VA—agreed with the recommendations and Treasury did not comment.

More recently, by the end of 2017, agencies appeared to "pick up the pace" of cloud adoption (Figure 1).

|

|

|

|

Roles and responsibilities 1. Specify roles and responsibilities of all parties with respect to the SLA and, at a minimum, include agency and cloud providers. 2. Define key terms, such as dates and performance. |

|

Performance measures 3. Define clear measures for performance by the contractor. Include which party is responsible for measuring performance. Examples of such measures would include * Level of service (e.g., service availability—duration the service is to be available to the agency). * Capacity and capability of cloud service (e.g., maximum number of users that can access the cloud at one time and ability of provider to expand services to more users). * Response time (e.g., how quickly cloud service provider systems process a transaction entered by the customer, response time for responding to service outages). 4. Specify how and when the agency has access to its own data and networks. This includes how data and networks are to be managed and maintained throughout the duration of the SLA and transitioned back to the agency in case of exit/termination of service. 5. Specify the following service management requirements: * How the cloud service provider will monitor performance and report results to the agency. * When and how the agency, via an audit, is to confirm performance of the cloud service provider. 6. Provide for disaster recovery and continuity of operations planning and testing, including how and when the cloud service provider is to report such failures and outages to the agency. In addition, how the provider will remediate such situations and mitigate the risks of such problems from recurring. 7. Describe any applicable exception criteria when the cloud provider's performance measures do not apply (e.g., during scheduled maintenance or updates). |

|

Security 8. Specify metrics the cloud provider must meet in order to show it is meeting the agency's security performance requirements for protecting data (e.g., clearly define who has access to the data and the protections in place to protect the agency's data). 9. Specifies performance requirements and attributes defining how and when the cloud service provider is to notify the agency when security requirements are not being met (e.g., when there is a data breach). |

|

Consequences 10. Specify a range of enforceable consequences, such as penalties, for noncompliance with SLA performance measures. |

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office, Cloud Computing: Agencies Need to Incorporate Key Practices to Ensure Effective Performance, GAO-16-325, April 2016, http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676395.pdf.

|

|

|

IT Dashboard23

The Office of the Federal CIO launched the IT Dashboard on June 1, 2009, to improve the transparency and oversight of agency IT investments. To accomplish this, OMB directed agencies to report, via the Dashboard, the performance of their IT investments. The IT Dashboard now displays data from 26 agencies on the cost, schedule, and performance of more than 7,000 IT investments, with detailed data for more than 700 investments classified as "major." These 700 investments accounted for $38.7 billion of the agencies' planned $82 billion budget in FY2014. Agency CIOs are responsible for regularly evaluating and updating the data on the IT Dashboard. The data are publically available, allowing not just OMB and other oversight bodies to review them, but also the general public. Figure 3 provides an example of an agency's portfolio page.

|

|

|

Source: OMB. |

GAO has made a number of recommendations to improve the reliability and consistency of the data in the IT Dashboard,24 including that the Director of OMB direct the Federal CIO to make available regularly updated portions of the public version of the Dashboard.

Portfolio Review

On December 9, 2010, the Federal CIO issued the "25 Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal Information Technology Management." Among other goals and requirements, the plan requires agencies to establish TechStat Accountability Sessions (TechStat). Subsequently, the OMB created the PortfolioStat process in March 2012. These processes, described below, are intended to set forth a process for agency IT portfolio review and improve risk management of IT investments.

TechStat

Using the data in the Federal IT Dashboard, OMB launched TechStat Accountability Sessions ("TechStat") as a "face-to-face, evidence-based review" designed to identify and turn around underperforming IT investments. The majority of OMB-led TechStat sessions were conducted in 2010, and led to $3 billion in total cost savings or avoidances ("implications") and an average acceleration of project deliverables from more than 24 months to 8 months.25 In 2010-2011, OMB shifted the leadership of TechStat reviews to agency CIOs, and agencies then identified an additional $930 million in cost implications by the end of 2011.26

Additionally, the Federal CIO has reported that agency CIOs have held more than 300 agency-led TechStats, resulting in more than $900 million in cost implications. However, in 2014, GAO reported that while TechStat sessions were very effective in identifying weaknesses within agencies, they ultimately had minimal impact on improving risky projects because no mechanism was in place to make needed changes. The GAO also found that—

- the number of TechStat sessions conducted was relatively small compared to the number of medium- and higher-risk IT investments with only 19% of at-risk investments receiving a TechStat session; and

- disparity existed among agencies in the percentage of at-risk programs examined through a TechStat (for instance, the Department of Commerce reviewed 58% of their at-risk projects, while the Department of Health and Human Services reviewed only 13% of their at-risk projects).27

Overall, GAO recommended that agencies increase the number of TechStat sessions they conduct, as well as more thoroughly track the outcomes of those sessions.

More recently, researchers at the Brookings Institution examined agency efforts to improve their IT planning assessments. The researchers found that, while there were shortcomings in how many agencies conducted TechStats, some agencies had "taken TechStat a few steps further." For example:

The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) implemented their version of TechStat called iStat. iStat takes a 360-degree approach, not just the IT investment but provides a comprehensive view of the project's functionality, accountability, and performance issues. The iStat process consists of two bodies: the iStat Performance Review Board and the iStat Executive Committee (IEC). The review board assesses the investment for performance, compliance, and to recommend corrective actions. The review board's assessments and recommendations are then forwarded to the IEC for actions. The DOI has accomplished $50 million in cost avoidance through the termination of two projects and other structural reforms for other investments through the iStat process.28

Under FITARA, OMB is required to continue TechStat sessions, but as of November 2016, OMB had not incorporated TechStat results into the current version of the IT Dashboard.29

PortfolioStat

A PortfolioStat session is a yearly face-to-face assessment of an agency's IT portfolio, including a review of

- commodity IT investments,

- potential duplications of IT investments within the agency, and

- investments that do not appear to support agency missions or business functions.

PortfolioStat provides a process by which an agency can assess its IT portfolio management process, make decisions on eliminating duplication, augment current CIO-led capital planning and investment control processes, and move to shared solutions to maximize the return on IT investments across the portfolio. While TechStat is focused on IT performance at the specific project or investment level, PortfolioStat is focused on an agency's IT portfolio as a whole.

The PortfolioStat process is intended to allow agencies to develop a clearer picture of where duplication exists across their bureaus and components and to allow them to shift to intra- and interagency IT shared services. In assessments conducted in 2013 and 2015, GAO reported that the PortfolioStat initiative had the potential to save at least $3.8 billion, but found weaknesses in agency implementation.30

Oversight of Federal CIO Initiatives

Through hearings and GAO investigations, Congress has been active in monitoring the activities of the Federal CIO and the initiatives carried out by the office. Congress has been especially attentive to the topics of data center use and cloud adoption as they relate to achieving the goals of FITARA.

Congressional Oversight, 115th Congress

The 115th Congress has thus far introduced four bills and held four hearings related to Federal CIO initiatives.

Legislation

Two pairs of companion bills related to FITARA have been signed into law in the 115th Congress, the Modernizing Government Technology Act of 2017 (MGT Act) (H.R. 2227, S. 990, P.L. 115-91) and the FITARA Enhancement Act of 2017 (H.R. 3243, S. 1867, P.L. 115-88).

Modernizing Government Technology Act of 2017

H.R. 2227 was introduced April 28, 2017, by Representative Will Hurd. It passed the House on May 17, 2017, and was reported to the Senate. S. 990 was also introduced on April 28, 2017, by Senator Jerry Moran. It is substantially identical to H.R. 2227. The bill was referred to the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. No further action has been taken.

Among other provisions, both bills would establish at specified agencies an information technology system modernization and working capital fund to

- improve, retire, or replace existing information technology systems to enhance cybersecurity and to improve efficiency and effectiveness; and

- transition legacy information technology to cloud computing and other innovative platforms and technologies.

FITARA Enhancement Act of 2017

H.R. 3243 was introduced by Representative Gerald Connolly and passed by the House of Representatives as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2018. S. 1867 was introduced by Senator Steve Daines and ordered to be reported without amendment by the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

Both bills would eliminate end dates for rules requiring risk assessments for IT investments and reviewing IT investments for efficiency and waste. They would also extend a data center consolidation due to expire in October 2018 to 2020.

Hearings

The House has held four hearings related to FITARA:

The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 6.031Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations)May 23, 2018The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 5.032Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations)November 14, 2017The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 4.033Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations)June 15, 2017GAO'S 2017 High-Risk Report: 34 Programs in Peril34House Committee on Oversight and Government ReformFebruary 15, 2017

Government Accountability Office Reports and Testimony, 2016-2017

The GAO has conducted numerous investigations into the initiatives being carried out under the auspices of the U.S. CIO. The agency has also testified at congressional hearings and held one forum.

Data Center Optimization: Continued Agency Actions Needed to Meet Goals and Address Prior Recommendations35GAO-18-264May 23, 2018Information Technology: Continued Implementation of High-Risk Recommendations Is Needed to Better Manage Acquisitions, Operations, and CybersecurityGAO-18-566TMay 23, 2018Further Implementation of FITARA Related Recommendations Is Needed to Better Manage Acquisitions and Operations36GAO-18-234TNovember 14, 2017Sustained Management Attention to the Implementation of FITARA Is Needed to Better Manage Acquisitions and Operations37GAO-17-686TJune 13, 2017Data Center Optimization: Agencies Need to Complete Plans to Address Inconsistencies in Reported SavingsGAO-17-388May 18, 2017High-Risk Series: Progress on Many High-Risk Areas, While Substantial Efforts Needed on Others38GAO-17-375TFebruary 15, 2017Opportunities for Improving Acquisitions and Operations (Forum)39GAO-17-251SPApril 11, 2017Implementation of IT Reform Law and Related Initiatives Can Help Improve Acquisitions40GAO-17-494TMarch 28, 2017IT Dashboard: Agencies Need to Fully Consider Risks When Rating Their Major Investments41GAO-16-494June 2, 2016Information Technology: Federal Agencies Need to Address Aging Legacy Systems42GAO-16-468May 25, 2016Managing for Results: OMB Improved Implementation of Cross-Agency Priority Goals, but Could Be More Transparent About Measuring Progress43GAO-16-509May 20, 2016Information Technology: OMB and Agencies Need to Focus Continued Attention on Implementing Reform Law44GAO-16-672TMay 18, 2016Data Center Consolidation: Agencies Making Progress, but Planned Savings Goals Need to Be Established45GAO-16-323March 3, 2016

Recent Activity: FITARA Scorecard 6.0

On May 23, 2018, the "FITARA Scorecard 6.0" was issued at a House hearing (Figure 4).46

|

|

|

The sixth scorecard continues to grade agencies implementation of FITARA and the Making Electronic Government Accountable by Yielding Tangible Efficiencies Act of 2016 (MEGABYTE).47 This scorecard includes new areas required by the Modernizing Government Technology (MGT) Act48 and the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA).49

Since the prior scorecard in November 2017, 5 agencies increased their letter grade, 8 remained the same, and 11 decreased. Most of the decreases are due to a change in the grading methodology. In particular, the overall grade of nine agencies50 was lowered because the associated CIO does not report to the head of the agency. The addition of the MGT requirements also had a negative impact on several agencies and three agencies' grades were lower because of both.51 The scorecard noted, for example, that in the absence of the methodology changes, HHS would have raised its grade from a D to an A; however, their grade only increased to a C due to the downward impact of the MGT and CIO reporting changes. Overall, in the absence of changes to the methodology, there would have been three As52 and five Bs.53

At the May 23, 2018, hearing by the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, "The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 6.0,"54 David Powner, Director of Information Technology Management Issues at GAO, cited five areas where significant actions remain to be completed: consolidating data centers, CIO responsibilities, IT contract approval, managing software licenses, and improving the security of federal IT systems.

Consolidating Data Centers

OMB launched an initiative in 2010 to reduce the number of federal data centers, which was codified and expanded in FITARA. According to agencies, data center consolidation and optimization efforts have resulted in approximately $3.9 billion of cost savings through 2018. Even so, additional work remains. GAO has made 160 recommendations to OMB and agencies to improve the reporting of related cost savings and to achieve optimization targets; however, as of May 2018, 80 of the recommendations have not been fully addressed.55

CIO Responsibilities

In December 2017, Congress enacted the Modernizing Government Technology (MGT) Act, which authorized agencies to set up IT-specific working capital funds. Thus far, only three agencies have taken the steps necessary to set up their fund, while five additional agencies have plans to set up an MGT working capital fund by the end of FY2020. The working capital funds authorized under the MGT Act allow agencies to fund IT modernization and reinvest savings for additional modernization projects. One reason given for this low adoption rate is that the law did not provide agencies the authority to transfer money into their working capital funds. Additional legislative actions to provide agencies with this authority may be needed. The MGT Act also established a centralized Technology Modernization Fund (TMF) to fund large IT modernization projects. The MGT Act originally authorized $500 million for the TMF, but the fund has only received $125 million over the past two fiscal years, limiting the effectiveness of the TMF. While the Financial Services and General Government Fiscal Year 2020 Appropriation Act under consideration in the House would provide an additional $35 million for the fund, some believe more funding is needed to address the long list of agency IT modernization needs. Through hearings and GAO investigations, Congress has been active in monitoring the activities of the Federal CIO and the initiatives carried out by the office. Congress has been especially attentive to the topics of data center use and cloud adoption as they relate to achieving the goals of FITARA. The 116th Congress has thus far not introduced any legislation related to FITARA. The House Committee on Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on Government Operations has held one hearing, "The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 8.0,"16 on June 26, 2019. The GAO has conducted numerous investigations into the initiatives being carried out under the auspices of the U.S. CIO. Most recently, GAO published testimony provided before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on Government Operations, "Implementation of GAO Recommendations Would Strengthen Federal Agencies' Acquisitions, Operations, and Cybersecurity Efforts," (GAO-19-641T), June 26, 2019.17

GAO also published reports on cloud adoption and data center optimization. In "Cloud Computing: Agencies Have Increased Usage and Realized Benefits, but Cost and Savings Data Need to Be Better Tracked" (GAO-19-58), published April 4, 2019,18 GAO noted that, each year, federal agencies spend $90 billion on IT. The agency found, though, that agencies don't consistently track cloud-related savings, making it hard for them to make informed decisions on whether to use cloud services. GAO recommended that agencies improve their savings tracking. In "Data Center Optimization: Additional Agency Actions Needed to Meet OMB Goals" (GAO-19-241), published April 11, 2019,19 GAO noted that federal agencies that since 2010 have been required to close unneeded data center facilities and improve the performance of remaining facilities. Across the government, agencies have closed 6,250 centers to date and saved $2.7 billion. However, GAO stated that only 2 agencies in its review planned to meet September 2018 government-wide optimization goals that include, for example, a target for how much time data servers sit unused.

Laws such as FITARA and related guidance assigned 35 key IT management responsibilities to CIOs to help address longstanding challenges. In August 2018, GAO reported that none of the 24 selected agencies had established policies that fully addressed the role of their CIO. GAO recommended that OMB and each of the 24 agencies take actions to improve the effectiveness of CIOs' implementation of their responsibilities. As of June 2019, none of the 27 recommendations had been implemented.Laws such as FITARA and related guidance assigned 35 key IT management responsibilities to CIOs to help address challenges. However, in a draft report on CIO responsibilities, GAO's preliminary results suggested that none of the 24 selected agencies have implemented policies that fully address the role of their CIO. GAO intends to recommend that OMB and each of the selected 24 agencies take actions to improve the effectiveness of CIO'sModernizing Government Technology (MGT) Act

implementation of their responsibilities.

IT Contract Approval

According to FITARA, covered agencies' CIOs are required to review and approve IT contracts. NeverthelessHowever, in January 2018, GAO reported that most of the CIOs at 22 selectedcovered agencies were not adequately involved in reviewing billions of dollars of IT acquisitions. Consequently, GAO made 39 recommendations to improve CIO oversight over IT acquisitions

Managing Software Licenses

Effective management of software licenses can help avoid purchasing too many licenses that result in unused software. In May 2014, GAO reported that better management of licenses was needed to achieve savings and made 135 recommendations for improvement. Most agencies generally agreed with the recommendations or had no comments. As of May 2018, 78 of the recommendations remained open.56

Improving the Security of Federal IT Systems

GAO found that agencies continue to need to improve their security programs, cyber capabilities, and the protection of personally identifiable information. GAO has made about 2,700 recommendations in the past few years to agencies aimed at improving the security of federal systems and information. As of May 2018, about 800 of the information security-related recommendations had not been implemented.

Appendix A.

Congressional Oversight, 114th Congress

Congress held seven hearings related to Federal CIO initiatives during the 114 Congress. No legislation was introduced related to FITARA or other Federal CIO initiatives.

The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 3.057Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations) December 6, 2016Federal Agencies' Reliance on Outdated and Unsupported Information Technology58House Committee on Oversight and Government ReformMay 25, 2016The Federal Information Technology Reform Act Scorecard 2.059Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations)May 18, 2016The Role of FITARA in Reducing IT Acquisition Risk, Part II—Measuring Agencies' FITARA Implementation60Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations)November 4, 2015The Role of FITARA in Reducing IT Acquisition Risk61Joint Hearing: House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform (Subcommittees on Information Technology and Government Operations)June 10, 2015Reducing Unnecessary Duplication in Federal Programs: Billions More Could Be Saved62Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental AffairsApril 14, 2015Risky Business: Examining GAO's 2015 List of High Risk Government Programs63Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental AffairsFebruary 11, 2015

Appendix B.

Government Accountability Office Reports, 2012-2015

The GAO has conducted numerous investigations into the initiatives being carried out under the auspices of the U.S. CIO. The agency has also testified at congressional hearings and held one forum.

Information Technology Reform: Billions of Dollars in Savings Have Been Realized, but Agencies Need to Complete Reinvestment Plans64GAO-15-617September 15, 2015Information Technology: Additional OMB and Agency Actions Needed to Ensure Portfolio Savings Are Realized and Effectively Tracked65GAO-15-296April 16, 2015Reporting to OMB Can Be Improved by Further Streamlining and Better Focusing on Priorities66GAO-15-106April 2, 2015Data Center Consolidation: Reporting Can Be Improved to Reflect Substantial Planned Savings67GAO-14-713September 25, 2014Information Technology: OMB and Agencies Need to More Effectively Implement Major Initiatives to Save Billions of Dollars68GAO-13-79July 25, 2013Information Technology: OMB and Agencies Need to Focus Continued Attention on Eliminating Duplicative Investments69GAO-13-685TJuly 25, 2013Data Center Consolidation: Strengthened Oversight Needed to Achieve Cost Savings Goal70GAO-13-378May 14, 2013Information Technology Reform: Progress Made but Future Cloud Computing Efforts Should Be Better Planned71GAO-12-756July 11, 2012

Author Contact Information

OMB launched an initiative in 2010 to reduce the number of data centers. According to 24 agencies, data center consolidation and optimization efforts had resulted in approximately $4.7 billion in cost savings through August 2018. However, additional work remains. GAO has made 196 recommendations to OMB and agencies to improve the reporting of related cost savings and to achieve optimization targets. As of June 2019, 79 of the recommendations had not been implemented.

Managing Software LicensesEffective management of software licenses can help avoid purchasing too many licenses that result in unused software. In May 2014, GAO reported that better management of licenses was needed to achieve savings, and made 136 recommendations to improve such management. As of June 2019, 27 of the recommendations had not been implemented.

Ensuring the Nation's Cybersecurity While the government has acted to protect federal information systems, GAO has consistently identified shortcomings in the federal government's approach to cybersecurity. The 3,058 recommendations that GAO made to agencies since 2010 have been aimed at addressing cybersecurity challenges. These recommendations have identified actions for agencies to take to fully implement aspects of their information security programs and strengthen technical security controls over their computer networks and systems. As of June 2019, 674 of the recommendations had not been implemented.Author Contact Information

Patricia Moloney Figliola, Specialist in Internet and Telecommunications Policy ([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])Footnotes

| 1. |

Testimony of David A. Powner, Director, Information Technology Management Issues, before the Subcommittees on Government Operations and Information Technology, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, OMB and Agencies Need to Focus Continued Attention on Implementing Reform Law, House of Representatives, May 18, 2016, https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/2016-05-18-Powner-Testimony-GAO-1.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 2. |

For example, the Department of Defense (DOD) canceled its Expeditionary Combat Support System in December 2012 after it had spent more than a billion dollars, but had not deployed the system within five years of initially obligating funds; the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) Secure Border Initiative Network program was canceled in January 2011 after DHS had spent more than $1 billion because the program did not meet cost-effectiveness and viability standards; the Department of Veterans Affairs' (VA) Financial and Logistics Integrated Technology Enterprise program, which was intended to be delivered by 2014 at a total estimated cost of $609 million, was terminated in October 2011 due to challenges in managing the program; the Farm Service Agency's Modernize and Innovate the Delivery of Agricultural Systems program, which was to replace aging hardware and software applications that process benefits to farmers, was canceled after 10 years at a cost of at least $423 million, while delivering only about 20% of the functionality that was originally planned; and the Office of Personnel Management's Retirement System Modernization program was canceled in February 2011 after the agency had spent approximately $231 million on its third attempt to automate the processing of federal employee retirement claims. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Additional Actions and Oversight Urgently Needed, GAO-15-675T, June 10, 2015 (hereinafter Additional Actions and Oversight Urgently Needed, GAO). |

||||||||||||

| 3. |

Additional Actions and Oversight Urgently Needed, GAO. |

||||||||||||

| 4. |

Title VIII, Subtitle D of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2015, P.L. 113-291. |

||||||||||||

| 5. |

Title VIII, Subtitle D of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2015, P.L. 113-291. See also H.Rept. 113-359. Not all federal agencies are subject to the requirements of FITARA. Generally, agencies identified in the Chief Financial Officers (CFO) Act of 1990, as well as their subordinate divisions and offices, are subject to the requirements of FITARA. The DOD, the intelligence community, and portions of other agencies that operate systems related to national security are subject to only certain portions of FITARA. Additionally, executive branch agencies not named in the CFO Act are encouraged, but not required, to follow FITARA guidelines. |

||||||||||||

| 6. |

The position of the Federal CIO and the CIO Council were created within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) by the E-Government Act of 2002. The role of the Federal CIO is to provide leadership and direction to the executive branch on IT implementation throughout the federal government. Specific responsibilities include directing the activities of the CIO Council, advising the Director of OMB on the performance of IT investments; and overseeing specific IT reform initiatives and activities. The CIO Council is the principal interagency forum on federal agency practices for IT management. Originally established by Executive Order 13011 (Federal Information Technology) and later codified by the E-Government Act of 2002, the CIO Council's mission is to help improve practices related to the design, acquisition, development, modernization, use, sharing, and performance of federal government information resources. CIO.gov is the website of the U.S. Chief Information Officer and the Federal CIO Council. |

||||||||||||

| 7. |

The "25-Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal IT Management" was one of the original policy documents developed as part of a comprehensive effort to increase the operational efficiency of federal technology assets. "A 25-Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal IT Management," Office of the U.S. Chief Information Officer, December 9, 2010, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/digital-strategy/25-point-implementation-plan-to-reform-federal-it.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 8. |

Strategic sourcing is "a method of managing procurement processes for an organization in which the procedures, methods, and sources are constantly re-evaluated to optimize value to the organization. Strategic sourcing, which is considered a key aspect of supply chain management, involves elements such as examination of purchasing budgets, the landscape of the supply market, negotiation with suppliers, and periodic assessments of supply transactions." BusinessDictionary.com, http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/strategic-sourcing.html. |

||||||||||||

| 9. |

For additional background on the FDCCI, see the "25-Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal IT Management." This plan was one of the original policy documents developed as part of a comprehensive effort to increase the operational efficiency of federal technology assets. Office of the U.S. Chief Information Officer, "A 25-Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal IT Management," December 9, 2010, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/digital-strategy/25-point-implementation-plan-to-reform-federal-it.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 10. | |||||||||||||

| 11. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Management and Oversight of Federal Information Technology, OMB-M-15-14, June 10, 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/2015/m-15-14.pdf (hereinafter "Management and Oversight of Federal Information Technology"). |

||||||||||||

| 12. |

In addition to implementing FITARA, OMB Memorandum M-15-14, "Management and Oversight of Federal Information Technology" also harmonizes the requirements of FITARA with existing law, primarily the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 and the E-Government Act of 2002. Those laws require OMB to issue management guidance for information technology and electronic government activities across the government, respectively. FITARA also contains provisions that required OMB interpretation before implementation. |

||||||||||||

| 13. |

Senior Agency Officials, as referred to in OMB M-15-14, include positions, for example, chief financial officer, chief administrative officer, chief operating officer, and program manager. |

||||||||||||

| 14. |

"Management and Oversight of Federal Information Technology" (OMB-M-15-14), OMB. |

||||||||||||

| 15. |

P.L. 104-106 (40 U.S.C. 1401 et seq.) and P.L. 107-347 (43 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.), respectively. For information on federal acquisition generally, see CRS Report R42826, The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR): Answers to Frequently Asked Questions, coordinated by | ||||||||||||

| 16. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Memorandum for Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies: Data Center Optimization Initiative," August 1, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/2016/m_16_19_1.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 17. |

The FDCCI was established by the U.S Office of Management and Budget memorandum, "Memo for CIOs: Federal Data Center Consolidation Initiative," February 26, 2010, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/egov_docs/federal_data_center_consolidation_initiative_02-26-2010.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 18. |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

17.

|

|

18.

|

|

19.

|

|

20.

|

|

https://oversight.house.gov/sites/democrats.oversight.house.gov/files/Scorecard%208.0.pdf. 21.

|

|

22.

|

https://oversight.house.gov/hearing/the-federal-information-technology-acquisition-reform-act-fitara-scorecard-6-0/ |

|

| 20. |

Private sector-provided cloud services are not considered data centers for the purposes of this memorandum, but must continue to be included in agencies' quarterly inventory data submissions to OMB. |

||||||||||||

| 21. |

U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Federal Cloud Computing Strategy February 8, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/egov_docs/federal-cloud-computing-strategy.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 22. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Cloud Computing: Agencies Need to Incorporate Key Practices to Ensure Effective Performance, GAO-16-325, April 2016, http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676395.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 23. |

| ||||||||||||

| 24. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, IT Dashboard: Agencies Are Managing Investment Risk, but Related Ratings Need to Be More Accurate and Available, GAO-14-64, December 2013, http://www.gao.gov/assets/660/659666.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 25. |

OMB reported conducting a total of 79 TechStat reviews: 59 in 2010, 8 in 2011, 11 in 2012, and 1 in the first half of 2013. OMB stated that it conducted fewer TechStats in recent years because it expected agencies to increase the number of agency-led TechStats. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Additional Executive Review Sessions Needed to Address Troubled Projects, GAO-13-524, June 13, 2013, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-524. |

||||||||||||

| 26. |

Federal Chief Information Officers Council, The State of Federal Information Technology, January 2017, https://s3.amazonaws.com/sitesusa/wp-content/uploads/sites/1151/2017/05/CIO-Council-State-of-Federal-IT-Report-January-2017-1.pdf (hereinafter The State of Federal Information Technology). |

||||||||||||

| 27. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Additional Executive Review Sessions Needed to Address Troubled Projects, GAO-13-524, June 13, 2013, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-524. |

||||||||||||

| 28. |

| ||||||||||||

| 29. |

The State of Federal Information Technology. |

||||||||||||

| 30. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Additional OMB and Agency Actions Are Needed to Achieve Portfolio Savings, GAO-14-65, November 6, 2013, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-65; and U.S. Government Accountability Office, Additional OMB and Agency Actions Needed to Ensure Portfolio Savings Are Realized and Effectively Tracked, GAO-15-296, April 16, 2015, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-296. |

||||||||||||

| 31. | |||||||||||||

| 32. | |||||||||||||

| 33. | |||||||||||||

| 34. |

| ||||||||||||

| 35. | |||||||||||||

| 36. |

https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Powner_Testimony_FITARA-5.0.pdf |

||||||||||||

| 37. | |||||||||||||

| 38. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-375t. |

||||||||||||

| 39. |

This report is available online at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-251SP. |

||||||||||||

| 40. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-494T. |

||||||||||||

| 41. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-494. |

||||||||||||

| 42. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-468. |

||||||||||||

| 43. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-509. |

||||||||||||

| 44. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-672T. |

||||||||||||

| 45. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-323. |

||||||||||||

| 46. |

https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/FITARA-Scorecard-5.0-.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 47. |

P.L. 114-210; 130 Stat. 824. |

||||||||||||

| 48. |

Title X, Subtitle G of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2018, P.L. 115-91. |

||||||||||||

| 49. | |||||||||||||

| 50. |

USDA, HHS, DHS, DOJ, DOL, State, Treasury, NRC, and USAID. |

||||||||||||

| 51. |

HHS, DOJ, and USAID. |

||||||||||||

| 52. |

HHS, GSA, and USAID. |

||||||||||||

| 53. |

DOC, Ed., DOJ, DOl, and NSF. |

||||||||||||

| 54. | |||||||||||||

| 55. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Continued Implementation of High-Risk Recommendations Is Needed to Better Manage Acquisitions, Operations, and Cybersecurity, GAO-18-566T, Testimony of David Powner, May 23, 2018, https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Powner-GAO-Statement-5-23-FITARA-6.0.pdf. |

||||||||||||

| 56. |

In November 2017, 112 of the recommendations remained open. |

||||||||||||

| 57. |

Hearing information and webcast are available at https://oversight.house.gov/hearing/federal-information-technology-acquisition-reform-act-fitara-scorecard-3-0-measuring-agencies-implementation. |

||||||||||||

| 58. |

| ||||||||||||

| 59. |

| ||||||||||||

| 60. |

Information about this hearing can be found at http://docs.house.gov/Committee/Calendar/ByEvent.aspx?EventID=104158. |

||||||||||||

| 61. |

Information about this hearing can be found at http://docs.house.gov/Committee/Calendar/ByEvent.aspx?EventID=103599. |

||||||||||||

| 62. |

Information about this hearing can be found at http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/hearings/reducing-unnecessary-duplication-in-federal-programs-billions-more-could-be-saved. |

||||||||||||

| 63. |

Information about this hearing can be found at http://www.hsgac.senate.gov/hearings/risky-business-examining-gaos-2015-list-of-high-risk-government-programs. |

||||||||||||

| 64. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-617. |

||||||||||||

| 65. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-296. |

||||||||||||

| 66. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-106. |

||||||||||||

| 67. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-713. |

||||||||||||

| 68. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-796T. |

||||||||||||

| 69. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-685T. |

||||||||||||

| 70. |

This report is available online at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-378. |

||||||||||||

| 71. |

|