State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

Changes from May 18, 2018 to July 7, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Background of the Department of State and the Foreign Service

- The Emergence of a Professional Foreign Service and Key Related Statutes

- Selected Professional Attributes of the Foreign Service Provided for in the Foreign Service Act of 1980

- Department of State Personnel by Category

- Foreign Service Personnel

- Ambassadors, Chiefs of Mission, and Ambassadors-at-Large

- Foreign Service Officers

- Foreign Service Specialists

- Senior Foreign Service

- Locally Employed Staff

- Civil Service Personnel

- Department of State Staffing Levels Over Time

- Selected Issues for Congress

- State Department Leadership and Modernization Impact Initiative

- Workforce Readiness

- Improve Performance Management

- State Department Personnel Staffing Levels

- Transition from Hiring Freeze and Staff Reductions to Resumed Hiring

- Pace of Presidential Appointments to Senior Positions

- Congressional Responses and Options

- Diversity

- Outlook

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Categories of Foreign Service Personnel

- Table 2. Positions at the Rank of Ambassador-at-Large in the Department of State

- Table 3. Foreign Service Officer Cones

- Table 4. Department of State Civil Service Job Categories

- Table 5. Department of State Personnel Trends: 2008-2017

- Table 6. Impact Initiative Focus Areas and Keystone Projects

Summary

Current Context and Recent Developments

Shortly after his confirmation as Secretary of State in April 2018, Secretary Mike Pompeo lifted the hiring freeze that former Secretary Rex Tillerson left in place for over a year. Guidance issued after Secretary Pompeo's action indicates that the department intends to increase Foreign and Civil Service personnel levels in a manner consistent with the language and funding Congress included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). The Trump Administration has taken additional actions affecting Department of State personnel, including designing "keystone modernization projects" within its Leadership and Modernization Impact Initiative. These projects seek to strengthen workforce readiness and enhance performance management and employee accountability, among other goals. The State Department is also prioritizing efforts to address long-standing concerns regarding the perceived lack of diversity in the Foreign Service.

The Trump Administration has moved more slowly than previous Administrations in transmitting nominations for senior Department of State positions to the Senate for advice and consent; meanwhile, the Senate has taken longer than it has in the past to provide advice and consent for many of those nominations that have been transmitted.

Some Members of Congress and other observers have expressed varying levels of concern with some of these developments, with some arguing that the Trump Administration (especially under former Secretary Tillerson) had been purposefully attempting to weaken the Department of State and diminish its influence in developing and implementing U.S. foreign policy. Secretary Pompeo pledged that he will work to enable the Department of State to play a central role in implementing President Trump's agenda and protecting the national security of the United States, while empowering the department's personnel in their roles.

The Role of Congress in History and Today

The 115th Congress has demonstrated interest in applying the legislative branch's constitutional and statutory authorities to shape policies pertaining to Department of State personnel. Some congressional prerogatives date back to the 18th century: Congress established the Department of State and began prescribing salaries for personnel in 1789, while Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution provides the Senate the authority to provide advice and consent for presidential appointments of ambassadors and other public ministers and consuls. The role of Congress expanded more gradually elsewhere. The executive branch maintained almost exclusive authority in developing the administrative policies governing the U.S. diplomatic and consular services and their personnel until the mid-19th century, when Congress codified compensation levels for individuals appointed to certain diplomatic and consular positions. Congressional purview over this area has subsequently expanded considerably, as Congress merged the diplomatic and consular services into a Foreign Service with the passage of the Rogers Act of 1924 (P.L. 68-135) and later modernized and refined the Foreign Service's policies and procedures through the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-465).

The Department of State's Foreign Affairs Manual describes several categories of Foreign Service personnel at the Department of State. Many of these categories, or the authorities afforded to personnel employed within them, are provided through statute. In addition, the Department of State employed over 10,000 Civil Service (CS) employees as of December 2017, who work in 11 different job categories. Congress has long had a significant role in the administration of the Civil Service, whose framework is now defined in the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-454), as amended.

Looking Ahead

While the President possesses a level of control over executive branch personnel policies, several options are available to the 115th Congress and future Congresses to facilitate, alter, block, or conduct oversight of the executive branch's initiatives. These include legislative action through Department of State or foreign relations authorization measures and annual appropriations bills or other measures, as well as periodic hearings on management and reform issues. On personnel issues, for example, Congress could encourage the Department of State to further increase hiring with additional appropriated funds to the Human Resources category of the department's Diplomatic & Consular Programs account, which is used to pay salaries for the department's domestic and overseas American employees. Congress could also weigh in on the department's plans to improve workforce management, or consider changes to aspects of the presidential appointments process.

Introduction

Shortly following his confirmation as Secretary of State in April 2018, Secretary Mike Pompeo lifted the hiring freeze that former Secretary Rex Tillerson left in place for over a year. Subsequent guidance issued after the hiring freeze indicates that the department intends to increase Foreign and Civil Service personnel levels in a manner consistent with the language and funding Congress included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). The Trump Administration has taken additional actions affecting Department of State personnel, including designing "keystone modernization projects" within its Leadership and Modernization Impact Initiative. These projects seek to strengthen workforce readiness and enhance performance management and employee accountability, among other goals. The State Department is also prioritizing efforts to address long-standing concerns regarding the perceived lack of diversity in the Foreign Service.

The Trump Administration has moved more slowly than previous Administrations in transmitting nominations for senior Department of State positions to the Senate for advice and consent; meanwhile, the Senate has taken longer than it has in the past to provide advice and consent for many of those nominations that have been transmitted.

In general, some supporters of personnel reform argue that the Department of State has become increasingly overstaffed and sclerotic in recent decades, and that reform is needed to restore the department's foreign policymaking influence that it is perceived to have lost to other government entities such as the National Security Council and the Department of Defense. Others, however, have asserted that some of the Administration's policies, especially those under Secretary Tillerson, were leading to a weak, understaffed Department of State incapable of advancing and protecting America's foreign policy and national security interests abroad. Among those who have demonstrated concern with the Administration's approach is Senator Robert Menendez, the Ranking Member of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, who has commented that "we have an emaciated State Department under this Administration."1 Since his confirmation, Secretary Pompeo has pledged that he will work to enable the Department of State to play a central role in implementing President Trump's agenda and protecting the national security of the United States, empower the department's personnel in their roles, and ensure that department personnel have a clear understanding of the President's mission.

While the President possesses a level of control over personnel policies at the Department of State, Congress has demonstrated interest in leveraging its constitutional and statutory prerogatives to shape the department's personnel policies since at least the mid-19th century, when it codified compensation levels for individuals appointed to certain diplomatic and consular positions. More recently, passage of the landmark Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-465), building upon previous legislation dating back to the early 20th century, created the infrastructure for the modern-day Foreign Service, which is the United States' professional diplomatic corps tasked with serving at both U.S. overseas posts and in key diplomatic positions based at the department's headquarters in Washington, DC and elsewhere in the United States. Among other matters, the law prescribes the admission, appointment, promotion, and separation procedures of the Foreign Service. These provisions are designed to uphold congressional intent that, as reflected in legislation for over a century, America's diplomats serve as part of a professional organization wherein individuals are appointed and promoted in a manner that reflects merit principles.

In addition to the Foreign Service, the Department of State also employed over 10,000 Civil Service (CS) employees as of December 2017. Congress has long been engaged in governing the administration of the Civil Service, passing the Pendleton Act of 1883, which is viewed by many as the legal foundation of the Civil Service. The Civil Service Reform Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-454), as amended, provides the modern statutory framework for the Civil Service.

Given the priority the Trump Administration has placed on implementing changes affecting Department of State personnel, some Members of Congress with varying degrees of support for the Administration's efforts have demonstrated renewed interest in applying congressional prerogatives to ensure that any changes enhance American capabilities to project and protect its interests overseas. Factoring in the Administration's existing priorities and the fact that the Administration's policies could expand in scope, this report provides a comprehensive background summary of Department of State personnel infrastructure and practices, including those areas where policies were established or could be adjusted through congressional action. It begins with an overview of the Foreign Service, including a summary of legislative efforts to codify a professional Foreign Service and its key personnel policies. It then explores the department's Foreign Service and Civil Service personnel categories in some detail, specifying key statutes and authorities that remain relevant to current department workforce issues. The report concludes by identifying selected issues for Congress, which comprise areas where the Trump Administration is seeking to implement changes, and where Congress may seek to weigh in directly or indirectly.

State Department Personnel: Background and July 7, 2021 Selected Issues for the 117th Congress Cory R. Gill Congress has played a significant role in the management of the Department of State’s Analyst in Foreign Affairs workforce since 1789, when it established the State Department pursuant to statute and established salaries for the Secretary of State and other personnel. Beginning in the early 20th century, Congress passed a series of laws intended to address corruption and graft in the State Department’s diplomatic and consular services by merging them into the modern-day Foreign Service, a professional diplomatic corps. Today, the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96- 465) serves as the framework through which the Department of State organizes and administers the Foreign Service. This law seeks to maintain and strengthen the Foreign Service’s status as a professional diplomatic corps, providing for admission, appointment, promotion, and separation procedures that reflect merit principles and a rank-in-person merit classification system. In addition, the Foreign Service Act includes a finding stating that “the members of the Foreign Service should be representative of the American people,” and further provides that it intends to foster “the development and vigorous implementation of policies and procedures, including affirmative action programs” to encourage “entry into and advancement in the Foreign Service by persons from al segments of American society.” President Biden has stated his intention to leverage the State Department’s personnel to advance U.S. foreign policy goals, saying that he wil work to empower department staff and incorporate their perspectives into the policy development process. To date, much of the Biden Administration’s efforts in this area have focused on improving the State Department’s diversity and inclusion programs and increasing the size of the Foreign Service and Civil Service. However, in recent years several Members of Congress, former and current senior State Department officials, academics and think-tank analysts, and other stakeholders have published reports recommending that the State Department and Congress consider significant changes regarding the State Department’s personnel practices, not only with respect to diversity and inclusion and personnel strength, but also in several other areas including training and professional development opportunities for staff, Chief of Mission authority, and persistent vacancies in senior State Department positions requiring the advice and consent of the Senate, especial y ambassadorships. The proliferation of such proposals may reflect concerns among some that the State Department needs to consider reforms to restore the foreign policymaking influence that some perceive it to have lost to other government entities over the past several decades, including the National Security Council and the Department of Defense. In recent Congresses, Members have demonstrated interest in applying the legislative branch’s constitutional and statutory authorities to shape policies pertaining to Department of State personnel. For example, in 2016 Congress passed the Department of State Authorities Act, Fiscal Year 2017 (P.L. 114-323). This law provided new authorities to the State Department on matters such as security training for personnel assigned to high-risk, high- threat posts; compensation for local y employed staff; the expansion of opportunities for Civil Service personnel to serve overseas; and means of lateral entry into the Foreign Service for mid-career professionals. The 117th Congress is currently considering H.R. 1157, the Department of State Authorization Act of 2021 that, if enacted, would weigh in on a wide variety of personnel matters, including diversity and inclusion, fil ing Foreign Service vacancies, and workforce planning. Congressional Research Service link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 8 link to page 8 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 21 link to page 24 link to page 27 link to page 29 link to page 31 link to page 34 link to page 9 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 25 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 35 State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Background of the Department of State and the Foreign Service............................................. 2 The Emergence of a Professional Foreign Service and Key Related Statutes ....................... 2 Selected Professional Attributes of the Foreign Service Provided for in the Foreign Service Act of 1980 ................................................................................................. 5 Department of State Personnel by Category......................................................................... 8 Foreign Service Personnel........................................................................................... 8 Ambassadors, Chiefs of Mission, and Ambassadors-at-Large .................................... 10 Foreign Service Officers...................................................................................... 12 Foreign Service Specialists .................................................................................. 13 Senior Foreign Service ........................................................................................ 14 Local y Employed Staff....................................................................................... 14 Civil Service Personnel ............................................................................................ 16 Selected Issues for Congress ........................................................................................... 17 Diversity and Inclusion............................................................................................. 18 Personnel Staffing Levels ......................................................................................... 21 Training and Professionalism..................................................................................... 24 Chief of Mission Authority........................................................................................ 26 Ambassador Vacancies ............................................................................................. 28 Outlook ....................................................................................................................... 31 Figures Figure 1. Department of State 2020 Foreign Service Pay Schedule (Base Schedule) .................. 6 Figure 2. Department of State Minority Workforce by Rank, 2018 ........................................ 19 Figure 3. Department of State Female Workforce by Rank, 2018 .......................................... 19 Figure 4. Department of State Foreign Service and Civil Service Personnel Levels.................. 22 Tables Table 1. Categories of Foreign Service Personnel ................................................................. 9 Table 2. Positions at the Rank of Ambassador-at-Large in the Department of State ................. 11 Table 3. Foreign Service Officer Cones ............................................................................ 13 Table 4. Department of State Civil Service Job Categories................................................... 16 Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 32 Congressional Research Service State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress Introduction The Biden Administration has indicated a commitment to “revitalizing the foreign policy workforce” following what some view as a tumultuous period for the State Department’s personnel.1 For example, the State Department Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) most recent report identifying the department’s most significant management and performance chal enges noted recent incidents that, according to the OIG, hindered some employees’ trust in the State Department’s leadership. These included a case where the department “ended the detail of a career employee [in the Office of the Secretary] after significant discussion concerning the employee’s perceived political views, association with former administrations, and perceived national origin.”2 The State Department’s Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs and Chief of Protocol also resigned in November 2019 and June 2019, respectively, following al egations involving the mistreatment of personnel and leadership and management deficiencies.3 Additional y, in 2018 Congress directed the OIG to review the effects of the State Department’s hiring freeze, which lasted from January 2017 through April 2018, on the department’s operations.4 The OIG released its report in August 2019 and found, among other conclusions, that implementation of the hiring freeze “was not guided by strategic goals,” impacted the State Department’s capacity to address its most significant management chal enges, and negatively affected workforce morale.5 Consistent with the Biden Administration’s broader commitment to strengthening the foreign policy workforce, Secretary of State Antony Blinken has stated that he wil prioritize “reinvorgat[ing] the [State] Department,” by “investing in its greatest asset: the Foreign Service Officers, civil servants, and local y employed staff who animate American diplomacy around the world.”6 Much of Secretary Blinken’s efforts to date have focused on addressing concerns regarding the perceived lack of diversity in the State Department’s workforce, especial y with regard to the Foreign Service, including through appointing Ambassador Gina Abercrombie-Winstanley to serve as the State Department’s first Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer (CDIO). Additional y, as part of its FY2022 International Affairs budget request, the Biden Administration is seeking funding for an additional 485 Foreign Service and Civil Service Officers to work in areas such as countering Chinese, Russian, and Iranian malign influence; protecting U.S. critical infrastructure; and advancing the Biden Administration’s science and technology priorities.7 1 U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2022, at ht t ps://www.st at e.gov/wp-cont ent /uploads/2021/05/FY-2022-St ate_USAID-Congressional-Budget -Justification.pdfm p. 17. 2 U.S. Department of State, Office of Inspector General Inspector General Statement on the Department of State’s Major Management and Performance Challenges (FY 2020), OIG-EX-21-01, December 8, 2020, at ht t ps://www.st at eoig.gov/syst em/files/fy_2020_ig_letter_on_department_management_challenges_final.pdf , pp. 15, 17. 3 Colum Lynch, “ Senior State Oficial Accused of Mismanagement to Step Down,” Foreign Policy, October 18, 2019, at https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/18/pompeo-senior-diplomat-accused-of-mismanagement -to-step-down-international-orgnizations/; Josh Lederman, “ Trump’s chief of protocol pulled off the job ahead of G-20,” NBC News, June 25, 2019, at ht t ps://www.nbcnews.com/polit ics/nat ional-securit y/t rump-s-chief-protocol-pulled-job-ahead-g-20-n1021781. 4 Joint Explanatory Statement Accompanying Division K of Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2018 (Division K of P.L. 115-141 ), at https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20180319/DIV%20K%20SFROPSSOM%20FY18-OMNI.OCR.pdf, p. 9. 5 U.S. Department of State, Office of Inspector General, Review of the Effects of the Department of State Hiring Freeze, ISP-I-19-23, August 2019, at ht t ps://www.st at eoig.gov/syst em/files/aud-mero-20-09.pdf, pp. 2-3. 6 Antony J. Blinken, “ Statement for the Record before the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations,” January 19, 2021, at https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/011921_Blinken_Testimony.pdf. 7 U.S. Department of State, “ FY2022 Budget Request: Department of State and USAID,” Slide Presentation, May 28, 2021, p. 14. Congressional Research Service 1 State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress Members of the 117th Congress have demonstrated interest in leveraging their authorities to shape policies pertaining to Department of State personnel. For example, Congress is currently considering H.R. 1157, the Department of State Authorization Act of 2021 that, if enacted, would weigh in on a wide variety of personnel matters, including diversity and inclusion, fil ing Foreign Service vacancies, and workforce planning. Additional y, Members of Congress, former and current senior State Department officials, academics and think-tank analysts, and other stakeholders have published several reports with increased frequency over the past decade recommending that the State Department and Congress consider significant changes regarding the State Department’s personnel practices. Proposed changes address diversity and inclusion and personnel strength, but also several other issues including training and professional development opportunities for staff, Chief of Mission authority, and persistent vacancies in senior State Department positions requiring the advice and consent of the Senate, especial y ambassadorships. In some cases, these issues have persisted across many Administrations and may present considerable chal enges should the Biden Administration and Congress seek remedies. Background of the Department of State and the Foreign Service

Congress established the Department of State in 1789 and prescribedprescribed an initial salary for the the Secretary of State, the department'’s chief clerk,, and other clerks employed by the department. The department'’s domestic staff was initiallyinitial y extremely smallsmal , consisting of only three clerks and

translators when Thomas Jefferson became Secretary of State inin 1790 and expanding to 10 such individuals 10 such individuals by the conclusion of the 18th century.218th century.8 Similarly, U.S. diplomatic representation abroad was fairlyfairly limited during this period—only two commissioned American diplomats were present in Europe when President Washington was inaugurated in 1789. By 17971797, the United States maintained diplomatic relations with France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain,Spain, yet had only limited diplomatic ties with other countries,, including Austria, Prussia,

Russia, and Sweden.3

9

The Emergence of a Professional Foreign Service and Key Related Statutes4

Related Statutes10 For nearly 70 years subsequent to the founding of the Department of State in 1789, an individual employee'employee’s rank and salary were attached to a specific position. In practice, this meant that the President appointed individuals to specific posts (frequently his political alliesal ies) and, upon his own

determination, set the compensation that the individual would receive at that post. If a person was sent to a subsequent overseas post, another appointment was required and a new compensation level was established. Because of funding constraints, ministers at larger posts such as London and Paris often had to spend their own funds to maintain their ability to provide representation, limiting limiting the scope of individuals capable of serving at such posts. Some observers refer to this

framework as the "“spoils system"” or a "“patronage system."” When addressing the spoils system,

President Theodore Roosevelt reflected that

8 Elmer Plischke, U.S. Department of State: A Reference History (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1999), p. 45. 9 Elmer Plischke, U.S. Department of State: A Reference History, pp. 46-47, 56.

10 This section draws on previous CRS analysis charting historical movement toward a merit -based diplomatic service. See CRS Memo DL095495, The Foreign Service and the Senate’s advice and consent authority, by Kennon H. Nakamura.

Congressional Research Service

2

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

[t]he spoils system of making appointments to and removals from office is so wholly and unmixedly evil, is so emphatically un-American and undemocratic, and is so potent a force for degradation in our public life, that it is difficult to believe that any intelligent man of ordinary decency who has looked into the matter can be its advocate. As a matter of fact, the arguments in favor of the merit system against the arguments in favor of the merit system against the spoils system are not not only convincing; they are absolutely unanswerable.5

11

Congress codified compensation levels for individuals appointed to specific diplomatic and consular positions beginning in 1855, in effect taking compensation determinations out of the hands of the President. U.S. consuls were also provided, for the first time, with annual federal salaries, the amount depending on where they were posted. However, the federal government

continued to staff its bureaucracy through the spoils system. Following the Civil War, difficulties stemming from the spoils systems were becoming increasingly evident throughout the federal government, including in the Department of State. It is reported that Secretary of State Hamilton Fish (1869-1877) threatened President Ulysses Grant with his resignation if President Grant and his political allies al ies did not stop interfering with the organization and operation of the department

and appointments of diplomats and consular officers.

Key Statutes Related to the Organization and Practices of the Modern Foreign Service (in sequential order)

The Stone-Flood Act (P.L. The Rogers Act of 1924 (P.L. 68-135). This law merged the State Department The Foreign Service Act of 1946 (P.L. 79-724) The Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-465). The Foreign |

During this period, graft was found to be especiallyespecial y rampant in the consular service. On September 20, 1885, President Grover Cleveland issued an executive order placing the lower grades of the consular service under a merit system with emphasis on "“character, responsibility

and capacity"” as criteria for appointment. President Theodore Roosevelt made efforts to professionalize the diplomatic service, placing diplomatic officers under previous laws intended to reform the Civil Service and creating a Board of Examiners tasked with developing an entrance

11 American Foreign Service Association, “ In the Beginning: The Rogers Act of 1924,” at http://www.afsa.org/beginning-rogers-act-1924.

Congressional Research Service

3

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

examination system testing knowledge of international law, diplomatic usage, and modern language skills. It also was tasked with developing and overseeing a merit promotion system for all all diplomatic and consular positions except those of minister and ambassador. The Stone-Flood Act (P.L 63-242, also known as "“An Act for the Improvement of the Foreign Service"”) was later enacted in 1915, which gavegiving previous executive orders in this area the force of law. This law also divided divided personnel into their own classes or grades for the first time, assigned salary levels to

classes or grades, and stated that appointments to a class "shall “shal be by commission to the offices of the secretary of embassy or legation, consul general, or consul, and not by commission to any particular post."” This marked the first time that the "“rank-in-person"” concept was incorporated into law for diplomatic personnel.

professionalize the Foreign Service.

responsibilities of a position.

It defined a Foreign Service Officer

Source: See Harold H. Leich, |

In addition to combining the U.S. diplomatic and consular services for the first time and establishing the modern Foreign Service, the Rogers Act of 1924 (P.L. 68-135) included several provisions to further professionalize the Foreign Service. It defined a Foreign Service Officer as a "permanent officer in the Foreign Service below the grade of minister, all al of whom are subject to promotion on merit, and who may be assigned to duty in either the diplomatic or the consular

branch of the Foreign Service at the discretion of the President."” Furthermore, this law

- established grades and classes of Foreign Service Officers and established salaries for those grades and classes;

-

stated that appointments to the position of Foreign Service Officer

shallshal be made after examination and a suitable period of probation in an unclassified grade, or after five years of continuous service in the Department of State by transfer to the Foreign Service upon meeting the rules and regulations established by the President; -

established that

allal appointments to the Foreign Serviceshallshal be by commission to a class and not by commission to any particular post, and that a Foreign Service Officershallshal be assigned to a post and may be transferred by the President from post to post depending upon the interests of the service; -

stated that Foreign Service Officers may be appointed as secretaries in the

diplomatic service or as consular officers or both and that any such appointment

shallshal be made by and with the advice and consent of the Senate; and - authorized the President to establish a Foreign Service retirement and disability system to be administered by the Secretary of State, and provided for a mandatory retirement age of 65 with 15 years of service.

Congress worked to consolidate and revise laws pertaining to the administration of the Foreign Service when it passed the Foreign Service Act of 1946 (P.L. 79-724). This law created a new Director General of the Foreign Service and a Foreign Service Board with the intent of improving

the department'’s administration of the Foreign Service, while a new Board of Examiners was authorized and tasked with maintaining the principle of competitive entrance into the Foreign Service. According to the Department of State, "“the law also provided for improvements in assignments policy, promotion procedures, allowancesal owances and benefits, home leave, and the retirement system."6

Congressional Research Service

4

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

retirement system.”12 Congress did not pass significant new legislation to govern the Foreign Service for several decades, until the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-465) was enacted. Among other measures, this law created a new Senior Foreign Service and reformed overseas allowances

al owances and spousal rights.713 Selected aspects of this legislation are discussed in detail below.

Selected Professional Attributes of the Foreign Service Provided for in the Foreign Service Act of 1980

Like the Foreign Service Act of 1946, the Foreign Service Act of 1980 sought to maintain and strengthen the Foreign Service'’s status as a professional diplomatic corps. The law provides for admission, appointment, promotion, and separation procedures that reflect merit principles and a rank-in-person merit classification system. Section 101 of the law reaffirms that "“a career foreign service, characterized by excellenceexcel ence and professionalism, is essential in the national interest to assist the President and the Secretary of State in conducting the foreign affairs of the United

States."” Section 105 provides that "all “al personnel actions with respect to career members and career candidates in the service (including applicants for career candidate appointments) shall be shal be

made in accordance with merit principles."8

”14

With specific regard to admission procedures, Section 301 requires the Secretary of State to "“prescribe, as appropriate, written, oral, physical, foreign language, and other examinations for appointment to the service (other than as a chief of mission or ambassador at large)."” In addition, Section 211 requires the President to establish a Board of Examiners for the Foreign Service to develop and supervise the administration of these examinations to candidates for appointment.

The President is required to appoint the Board'’s 15 members, at least five of whom must "“be appointed from among individuals who are not Government employees and who shall shal be qualified for service on the Board by virtue of their knowledge, experience, or training in the fields of testing or equal employment opportunity."” The Board must be chaired by a member of the Foreign Service. Individuals who pass the examinations and are admitted into the Foreign

Service are required to serve for a trial period that generallygeneral y does not exceed five years under a limited appointment prior to receiving a career appointment in the Foreign Service. Section 306 of the law requires that any decision by the Secretary of State to recommend that the President give a career appointment to such an individual shall shal be informed "“based upon the recommendations of boards, established by the Secretary and composed entirely or primarily of

career members of the service, which shall shal evaluate the fitness and aptitude of career candidates

for the work of the service."9

”15

As with admission requirements and procedures, the Foreign Service Act of 1980 intends to

ensure that appointments processes preserve and bolster the Foreign Service'’s status as a professional organization. Section 302 provides the President the authority to, "“by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoint an individual as a chief of mission, as an ambassador at large, as an ambassador, as a minister, as a career member of the Senior Foreign Service, or as a 12 U.S. Department of State, Ofice of the Historian, “ A Short History of the Department of State: A Changing Role for the Secretary,” at ht t ps://hist ory.st ate.gov/depart menthistory/short-hist ory/secretary.

13 U.S. Department of State, Ofice of the Historian, “ A Short History of the Department of State: Landmark Departmental Reform, ” at ht t ps://hist ory.st ate.gov/depart menthistory/short-hist ory/reforms/ 14 According to Section 105(a)(2) of the Foreign Service Act, “ personnel action” means “ any appointment, promotion, assignment (including assignment to any position or salary class), award of performance pay or special differential, within-class salary increase,

separation, or performance evaluation,” and any decision, recommendation, examination, or ranking provided for under this act which relates to any such action previously referred to in subparagraph (A) of the section.

15 See Section 306 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 9 link to page 17

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

large, as an ambassador, as a minister, as a career member of the Senior Foreign Service, or as a Foreign Service officer."” Section 301 clarifies that "“an appointment as a Foreign Service officer is a career appointment,"” while Section 303 indicates that the Secretary of State'’s appointment authorities do not extend to the personnel categories specified for presidential appointments in Section 302. Thus, all al Foreign Service Officers (with the exception of some Senior Foreign Service Officers) are career members of the Foreign Service, appointed by the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, and typicallytypical y serve over the course of several

presidential administrations. Section 305 provides for authorized limited, noncareer appointments

to the Senior Foreign Service under certain circumstances.10

16

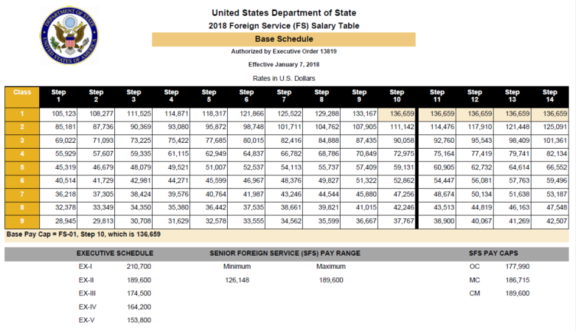

Sections 305 and 404 further stipulate that Foreign Service officersOfficers and other personnel, and both career and noncareer members of the Senior Foreign Service, shall shal be appointed to salary classes—rather than to individual positions—that the Secretary of State is authorized to establish.1117 These provisions undergird the Foreign Service personnel system as a rank-in-person, rather than rank-in-position, approachapproach. Figure 1 illustrates one currentil ustrates one recent pay schedule, providing the

salary classes to which Foreign Service Officers are appointed and promoted.

Figure 1. Department of State |

|

|

This rank-in-person orientation of Foreign Service personnel practices is widely perceived as a

merit-based system. Inherent to the rank-in-person system are the "“up or out rules,"” which are

16 See the “ Senior Foreign Service” subsection for more detail regarding limited, noncareer appointments to the Senior Foreign Service.

17 See Sections 305 and 404 of Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

Congressional Research Service

6

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

which are mandated in Section 607 the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (where they are known as "“time-in-class limitations"”). These rules require that both career members of the Senior Foreign Service and the Foreign Service are either promoted within a specified time period denoted for each salary class (or a combination of salary classes) or are otherwise retired from the service if not performing at an adequate level.1218 The process the law prescribes for considering the promotion of members of the Senior Foreign Service and the Foreign Service is also intended to promote

merit-based practices. Section 602 mandates the establishment of selection boards tasked with evaluating the performance of these personnel through ranking the members of a salary class on the basis of relative performance and making recommendations for personnel actions, including promotion. The membership of selection boards is required to include public members and "a “a substantial number of women and members of minority groups."13”19 The law also requires that the

selection boards'’ recommendations and rankings reflect "“records of the character, ability, conduct, quality of work, industry, experience, dependability, usefulness, and general performance of members of the service."14”20 Section 605 further provides that the Secretary of State shall shal make promotions (and, with respect to career appointments into or within the Senior Foreign Service, recommendations to the President for promotions) "“in accordance with the rankings of the

selection boards."” It also provides the Secretary the authority to delay the promotion of an individual individual designated for promotion on a selection board list or remove that individual from a list

in “in "special circumstances"” provided for by department regulations.15

Finally21

Final y, provisions of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 governing the separation of members from the service for cause seek to further preserve the Foreign Service'’s professional character and ensure that individuals are not separated without due process. Section 610 provides that the Secretary of State may "“decide to separate any member from the service for such cause as will wil promote the efficiency of the service."” However, in most cases any member of the Foreign

Service serving under a career appointment or a limited appointment may not be separated on the basis of misconduct until the member in question receives a hearing before the Foreign Service Grievance Board and the Board decides that cause for separation has been established.1622 The Foreign Service Grievance Board is itself authorized in Section 1105 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980. The law requires that its membership comprise individuals approved by the exclusive representative (labor organization) representing Foreign Service employees and the department

itself; to further help ensure impartiality, five of board members are required by law not to be department employees. It also authorizes the Foreign Service Grievance Board to intervene in cases where it determines that the department is considering the involuntary separation of a grievant for reasons other than cause. If the Foreign Service Grievance Board finds that a grievant'grievant’s claim is valid, it is authorized to direct the Department of State to retain the member in

the service.17

23

18 See Section 607 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended. 19 See Section 602 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

20 See Section 603 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended. 21 See Section 605 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended. 22 As the law notes, the right to a hearing does not apply in cases where an individual “ has been convicted of a crime for which a sentence of imprisonment of more than one year may be imposed.” The right to a hearing also does not apply to United States citizens employed under Section 311 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended, who is not a family member of a government employee assigned abroad.

23 See Sections 1105, 1106, and 1107 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 12 State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

Department of State Personnel by Category Department of State Personnel by Category

Department of State personnel can broadly be characterized as being employed in the Foreign Service or the Civil Service; however, many categories therein are governed by various legal authorities passed by Congress. With respect to the Foreign Service, such categories encompass Chiefs of Mission, all al U.S. diplomats serving at State Department posts abroad and in the United States, the locallylocal y employed staff with management responsibilities important to the functioning

of overseas posts, and all al other Foreign Service personnel. Therefore, should Congress seek to weigh in on executive branch practices—including the admission, appointment, or promotion of an official of the Department of State; the responsibilities or compensation afforded to a department official; or the separation of an official from the Department of State—the means through which it would do so depend on the employment category of the official in question and

its associated legal authorities.

Foreign Service Personnel

Both Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution and The Foreign Service Act of 1980 provide Congress with substantial authorities with respect to the appointment, governance, and administration of Foreign Service personnel. Article II, Section 2, allowsal ows the President to appoint Ambassadors by and with the advice and consent of the Senate in most circumstances; additionally, additional y, Congress has invoked its constitutional authority to provide advice and consent for "

“other public Ministers and Consuls"” by explicitly requiring advice and consent for senior Department of State officials, including positions typicallytypical y held by career Senior Foreign Service

and Foreign Service officers.18

Officers.24

Furthermore, Congress authorized and defined the Foreign Service and its employees pursuant to the Foreign Service Act of 1980.1925 The Foreign Service Act of 1980 also placed within the purview of Congress the admission, appointment, promotion, and separation procedures of the Foreign Service. It authorized the Senior Foreign Service and the appointment of Foreign Service Nationals, Eligible Family Members, and Consular Agents, and required that the Foreign Service

operate in a fashion consistent with merit principles. Table 1 makes note of categories of Foreign

Service personnel described in the FAM.

In other areas, the Foreign Service Act of 1980 gives more discretion to the executive branch. It

does not prescribe the five "cones"“cones” within which Foreign Service Officers work, nor does it explicitly prescribe the titles for the Senior Foreign Service salary classes. In still stil other cases, the law provides for arrangements where responsibilities are shared by the legislative and executive branch. For example, although the Foreign Service Act of 1980 requires candidates for the career Foreign Service Officer to serve a trial period prior to their appointment, the department is

afforded flexibility to determine the duration and nature of the trial period.

24 For example, Section 208 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended, provides in part that “ the President shall appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, a Director General of the Foreign Service, who shall be a current or former career member of the Foreign Service.” 25 For example, see Sections 103 and 104 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

Congressional Research Service

8

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

Table 1. Categories of Foreign Service Personnel

The Foreign Af airsTable 1. Categories of Foreign Service Personnel

The Foreign Affairs Manual notes that there are several categories of Foreign Service Personnel.

A brief description of each of these personnel categories follows.

|

Category |

Description |

|

Ambassadors and Ambassadors-at-Large |

|

|

Career Ambassadors |

|

|

Chiefs of Mission |

Chiefs of Mission are principal officers appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to be in charge of a diplomatic mission |

|

Consular Agents |

Consular Agents provide consular and related services |

|

Consular Fellows |

|

|

Foreign Service Officers |

|

|

Foreign Service Specialists |

|

|

Locally Employed Staff |

|

|

Senior Foreign Service |

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), "“Categories of Foreign Service Personnel," 3 ” 3 FAM 2230, at https://fam.state.gov/; U.S. Department of State, Consular Fellows Program, "Fel ows Program, “What We Do,"” at https://careers.state.gov/work/foreign-service/consular-fellows/what-we-do/.

.

Ambassadors, Chiefs of Mission, and Ambassadors-at-Large

The Department of State'’s Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) prescribes several categories of Foreign Service personnel. Among the most senior Foreign Service personnel identified in the FAM are Ambassadors and Ambassadors-at-Large. Section 302(a) of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 requires that the President appoint Ambassadors and Ambassadors-at-Large by and with the

advice and consent of the Senate in nearly all al circumstances; the President can circumvent the Senate only with respect to conferring the personal rank of ambassador on an individual in connection with a special, temporary mission for the President not exceeding six months in

duration and, separately, through the use of recess appointments.20

26

U.S. ambassadors who lead U.S. embassies abroad and ambassadors who head other official U.S. missions are usuallyusual y appointed by the President as the "“Chief of Mission"” (COM), which is the title conferred on the principal officer in charge of each U.S. diplomatic mission to a foreign country, foreign territory, or international organization. Each COM thus serves as the President's ’s

personal representative, leading diplomatic efforts for a particular mission or in the country of assignment under the general supervision of the Secretary of State and with the support of the regional assistant secretary of state. COM authority is authorized by the Foreign Service Act of 1980 and is also derived from an array of executive branch orders and directives.21 Section 207 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 states that under the direction of the President, a COM "shall have full responsibility for the direction, coordination, and supervision of all While Congress has vested several authorities in COMs pursuant to Section 207 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 and other laws, COM authority is also shaped through executive branch directives and regulations, including Presidential Letters of

Instruction, Executive Orders, and State Department regulations.27 The Section 207 authorities

entail:

exercising full responsibility for the direction, coordination, and supervision of al

Government executive branch employees in that country (except for Voice of America correspondents on official assignment and employees under the command of a United

States area military commander);

keeping fully and currently informed with respect to al activities and operations

of the Government within that country, and insuring that al Government executive branch employees in that country," (except for Voice of America (VOA) correspondents on official assignment and employees under the command of a U.S. Geographic Combatant Commander (GCC).22

While Section 304 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 provides that "

United States area military commander) comply fully with al applicable directives of the chief of mission;

26 The President’s authority to make recess appointments is derived from Article II, Section 2, clause 3 of the U.S. Constitutio n. 27 For more information on COM authority, see CRS Report R43422, U.S. Diplomatic Missions: Background and Issues on Chief of Mission (COM) Authority, by Matthew C. Weed and Nina M. Serafino . Others laws, as codified, through which Congress has vested authorities in Chiefs of Mission include 8 U.S.C. §1157 and 22 U.S.C §2656i.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 14 State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

promoting United States goods and services for export to such country; and promoting United States economic and commercial interests in such country.28

While Section 304 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 provides that “positions as chief of mission should normallynormal y be accorded to career members of the [Foreign] Service,"” the President is not required to appoint exclusively career Foreign Service Officers as COMs. In most recent Administrations, approximately 70% of appointees to U.S. ambassadorships have been career Foreign Service Officers, while the remainder have been political appointees.23non-career (political) appointees.29

President Trump chose to appoint a greater proportion of political appointees, which comprised around 44% of his ambassador appointments.30 Section 401 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 authorizes the President to compensate COMs at one of the annual rates payable for levels II

through V of the Executive Schedule, with some conditions.

Ambassadors-at-Large, on the other hand, are "“appointed by the President and serve anywhere in the world to help with emergent problems, to conduct special or intensive negotiations, or serve in other capacities, as requested by the Secretary or the President."24 All individuals ”31 Al individuals currently serving at the rank of Ambassador-at-Large are based in Washington, DC (seesee Table 2), and none

are therefore currently employed as COMs abroad. Ambassadors-at-Large generallygeneral y rank immediately below assistant secretaries of state in terms of protocol. They are perceived within the department as managers of crucial yet narrow issues, while assistant secretaries have much

broader responsibilities.25

32

Table 2. Positions at the Rank of Ambassador-at-Large in the

Department of State

(as of May 2021)

Position Title

Authorization Source

(as of May 2018)

|

Position Title |

Authorization Source |

Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women |

|

Issues Ambassador-at-Large for International |

22 U.S.C. |

), as amended.

Ambassador-at-Large to Monitor and |

22 U.S.C. |

|

Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues |

), as amended.

Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal

Department of State general authorities; statutory responsibilities

Justice

later prescribed |

|

Coordinator for Counterterrorism |

|

|

Coordinator of U.S. Government Activities to Combat Global HIV/AIDS and Special Representative for Global Health Diplomacy |

|

Source: CRS Report R44946, State Department Special Envoy, Representative, and Coordinator Positions: Background and Congressional Actions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Foreign Service Officers

Foreign Service Officers are U.S. diplomats who serve in one of five career tracks, or "“cones," ” within the Foreign Service: consular, economic, management, political, and public diplomacy.26 33 These cones, which are not provided for in statute, are described in more detail inin Table 3. Foreign Service Officers are also referred to by the Department of State as "“Foreign Service

Generalists,"” a term that does not appear in the Foreign Service Act of 1980.2734 The term "generalist"“generalist” derives from the view that Foreign Service Officers should be sufficiently flexible to accept a variety of assignments and effectively transfer their skillsskil s successfully across different jobs.2835 According to the Department of State'’s website, "“the mission of a U.S. diplomat in the Foreign Service is to promote peace, support prosperity, and protect American citizens while

advancing the interests of the U.S. abroad."29

”36

As previously noted, Section 302 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 authorizes the President to appoint individuals as Foreign Service Officers, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate,

after such individuals serve under a limited appointment as a career candidate for a trial period of service prescribed by the Secretary of State.3037 The trial period of service for Foreign Service Generalist Career Candidates generallygeneral y does not exceed five years.3138 The Foreign Service Act of 1980 also authorizes the Secretary of State to establish a Foreign Service Schedule consisting of nine salary classes, which is used to compensate Foreign Service Officers. The Foreign Service Act of 1980 also (1) serves as the basis through which Foreign Service Officers are promoted (in

other words, they are promoted from one salary class to the next rather than from one single position to another; see Sections 404 and 601 of the law); (2) codifies the process through which Foreign Service Officers are promoted in a way that seeks to ensure conformity with merit principles and the overall overal needs of the Foreign Service; and (3) governs the process to which the Secretary of State and other department officials must adhere when seeking to separate a Foreign

Service Officer from the Foreign Service for cause.32

|

Cone Title |

Description |

|

Consular Officer |

|

|

Economic Officer |

|

|

Management Officer |

Management Officers are responsible |

|

Political Officer |

Political Officer

Political Officers |

|

Public Diplomacy Officer |

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, "“Career Tracks for Foreign Service Officers," ” at https://careers.state.gov/work/foreign-service/officer/career-tracks/.

. Foreign Service Specialists

Foreign Service Specialists "“provide important technical, management, healthcare or administrative services"” at both Department of State posts in the United States and those overseas.3340 Unlike Foreign Service Officers, Foreign Service Specialists are not presidential

appointees. Instead, the Secretary of State appoints Foreign Service Specialists pursuant to the authorities conferred by Section 303 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980.3441 There are 19 different specialist jobs grouped into the following categories: administration, construction engineering, facility management, information technology, international information and English language programs, medical and health, office management, and law enforcement and security.35 The law enforcement and security, medical and health, and office management.42 The

Department of State created these job categories; they are not provided for in law.

The Department of State administers a career candidate program for Foreign Service Specialists separate from the aforementioned career candidate program for Foreign Service Officers. The

trial period for such appointees generallygeneral y does not exceed four years.3643 As Foreign Service Specialists are assigned to positions on the Foreign Service Schedule, they are compensated through the same means as Foreign Service Officers. Foreign Service Specialists serve under career or limited appointments and are entitled to the same statutory protections as Foreign Service Officers should the Secretary of State seek to separate a Foreign Service Specialist for

cause from the Foreign Service.37

Senior Foreign Service

The Foreign Service Act of 1980 established a Senior Foreign Service (SFS), which serves as "the 44

40 U.S. Department of State, “ Foreign Service Specialist,” at https://careers.state.gov/work/foreign-service/specialist/.

41 The status of Foreign Service Specialists as career members of the Foreign Service appointed under Section 303 of the Foreign Service Act is noted in 3 FAM 2234.1(b).

42 U.S. Department of State, “ Foreign Service Specialist,” at https://careers.state.gov/work/foreign-service/specialist/career-tracks.

43 See Section 309 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-465), as amended; U.S. Department of State, Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), “ General Provisions,” 3 FAM 2251.3, at ht t ps://fam.st at e.gov/.

44 The status of Foreign Service Specialists as career members of the Foreign Service is noted in 3 FAM 2234.1(b). Section 610(a)(2)(A) of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 (P.L. 96-465), as amended, which governs the separation for cause process, indicates that it applies to individuals serving under a career or limited appointment.

Congressional Research Service

13

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

Senior Foreign Service

The Foreign Service Act of 1980 established a Senior Foreign Service (SFS), which serves as “the corps of senior leaders and experts for the management of the service and the performance of its functions."38”45 The SFS was created to address what at the time was viewed by some as a glut of senior officers in the Department of State, which exceeded the number of senior positions

available. Congress intended for entrance standards into the SFS to be higher than those previously applied for promotion into the senior ranks. More stringent entrance standards and time-in-class limitations were intended to ensure that the ranks of the Senior Foreign Service did not become bloated and corresponded more closely to the number of available senior-level posts. Moreover, the time-in-class limitations curtailed the amount of time that Foreign Service Officers had to secure promotion to the SFS, as well wel as the amount of time that career Senior Foreign

Service Officers had to be promoted to the next available grade within the SFS. (If an officer exceeds these time-in-class limitations, he or she is required to be retired from the Foreign Service.39)

Service.)46

The President is authorized to appoint career members of the SFS, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, by Section 302 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980. Section 302 also authorizes the President to confer the personal rank of career ambassador upon a career member of the SFS, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, "“in recognition of especially especial y distinguished service over a sustained period."” The Secretary of State is authorized to make

limited, noncareer appointments to the SFS pursuant to Section 303 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, but Section 305 prohibits the Secretary from making a limited appointment if it would "“cause the number of members of the Senior Foreign Service serving under limited appointments to exceed 5 percent of the total number of members of the Senior Foreign Service,"” with some exceptions.40

exceptions.47

Section 402 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 requires the President to prescribe salary classes for the SFS and appropriate titles and ranges of basic salary rates for each class. The three salary classes and titles so prescribed are, in ascending order, those of Counselor, Minister-Counselor,

and Career Minister. As with the Foreign Service, promotion within the Senior Foreign Service comprises one'’s placement from one salary class to the next; promotion is not based on

movement from one single position to the next.

Locally Employed Staff

As of December 31, 20172020, the Department of State employed 50,225451 individuals classified as LocallyLocal y Employed Staff (LES), who comprise approximately 6866% of total State Department personnel.48 LESs include several subcategories of employees, including Foreign Service Nationals (FSNs), Appointment Eligible Family Members (or AEFMs, these staff are categorized as locally-employed staff for some but not all purposes), locally resident U.S. citizens, and third-country nationals.41 FSNs and AEFMs are discussed in more detail below.

Foreign Service Nationals (FSNs)

The Department of State'categorized as local y-

45 U.S. Department of State, Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), “ Senior Foreign Service,” 3 FAM 2233, at https://fam.state.gov/. 46 See Section 607 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended; also see U.S. Department of State, Ofice of the Historian, “ A Short History of the Department of State: Landmark Departmental Reform,” at ht t ps://hist ory.state.gov/department hist ory/short-history/reforms/.

47 See Section 305 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended

48 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Global T alent Management, “ HR Fact Sheet: Facts About Our Most Valuable Asset – Our People,” fact sheet, December 31, 2020, at https://www.afsa.org/sites/default/files/1220_state_dept_hr_factsheet.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

14

State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

employed staff for some but not al purposes), local y resident U.S. citizens, and third-country

nationals.49 FSNs and AEFMs are discussed in more detail below.

Foreign Service Nationals (FSNs)

The Department of State’s website notes that LES, including FSNs, provide an important source of continuity to each overseas post as American citizen employees rotate in and out, and that the

department "“depend[s] heavily on [them], frequently delegating to them significant management roles and program functions."42”50 The Foreign Service Act of 1980 authorizes the Secretary of State to appoint foreign national employees and states that foreign nationals who provide "“clerical, administrative, technical, fiscal, and other support at Foreign Service posts abroad" shall be ” shal be considered members of the Foreign Service."43”51 FSNs are appointed by individual overseas posts.4452 They are hired under local compensation plans established by the Secretary of State and

based on prevailing wage rates and compensation practices for corresponding types of positions in the locality of employment, as provided by Section 408 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980. The department'’s Office of Overseas Employment, located in the Bureau of Human ResourcesGlobal Talent Management, is responsible for developing and implementing human resources policies pertaining to FSNs at overseas posts, including matters regarding recruitment, position evaluation and classification

evaluation, and compensation.45

53

Appointment Eligible Family Eligible Family Members (AEFMs)

Section 311(a) of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 authorizes the Secretary of State to appoint "“United States citizens, who are family members of government employees assigned abroad or are hired for service at their post of residence, for employment in positions customarily filledfil ed by

by Foreign Service officers, Foreign Service personnel, and foreign national employees."” It further provides that family members appointed under this provision shall shal be compensated in accordance ac cordance with the Foreign Service Schedule or at lower rates that the Secretary of State is authorized to

establish pursuant to Section 407 of the law.46

54

The Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) clarifies that in order to be considered an AEFM, one must be a U.S. citizen, the spouse or domestic partner of a sponsoring employee, listed on the travel orders or approved Foreign Service Residence and Dependency Report of a sponsoring employee, employee, and residing at the sponsoring employee'’s post of assignment abroad.47.55 The Department of State

can employ AEFMs through family member appointments, which are limited, noncareer non-career appointments that exceed one year but are no longer than five years and can be extended or renewed pursuant to Section 309 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980. AEFMs can also be employed through temporary appointments that Section 309 provides shall shal last for one year or

less.56

49 According to 6 FAH 5 H-352.2, AEFMs are counted as locally employed staff for some, but not all, purposes.

50 U.S. Department of State, “ Local Employment in U.S. Embassies and Consulates,” at https://careers.state.gov/work/foreign-service/local-employment/.

51 See Section 103 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

52 U.S. Department of State, Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), “ Appointment,” 3 FAM 7240, at https://fam.state.gov/.

53 U.S. Department of State, “ Local Employment in U.S. Embassies and Consulates,” at https://careers.state.gov/work/foreign-service/local-employment/.

54 See Section 408 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

55 U.S. Department of State, Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), “ Definitions,” 3 FAM 7121, at https://fam.state.gov/

56 Ibid; also see Section 309 of the Foreign Service Act of 1980, as amended.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 19 State Department Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for the 117th Congress

last for one year or less.48

The Department of State notes that its Family Member Employment Program reflects its understanding that when family members of Foreign Service employees join the Foreign Service community, they frequently already have established personal and professional lives. Furthermore, the department acknowledges that "finding meaningful employment overseas is challenging given limited positions inside U.S. missions, language requirements, lower salaries, and work permit barriers on the local economy."49 On January 23, 2017, President Donald Trump issued a presidential memorandum ordering a freeze on the hiring of federal civilian employees to be applied across the board in the executive branch.50 Although OMB Memorandum M-17-22, issued in April 2017, subsequently lifted the hiring freeze, the Department of State elected to maintain its hiring freeze, including with respect to offering appointments to AEFMs.51 This move elicited criticism from some observers, who argued that that it harmed morale at overseas posts. They also charged that it negatively affected the ability of overseas posts to complete important tasks carried out by AEFMs, including staffing medical units, ensuring that local housing meets security standards, and overseeing infrastructure repairs and maintenance. Finally, they stated that it deprived the department of cost-savings from using AEFMs to fill certain jobs that would otherwise be filled by Foreign Service Officers.52 In September 2017, Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan testified that the department had granted exemptions to the hiring freeze and brought on between 800 and 900 AEFMs to work at embassies overseas since it went into effect.53 On December 11, 2017, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson announced that the hiring freeze on AEFMs would be lifted in 2018, but it does not appear that he took action to implement this directive.54 On May 1, 2018, Secretary Pompeo announced that the hiring freeze on AEFMs would be lifted, and language on the department's website providing guidance for implementation of the hiring freeze was removed.55

Civil Service Personnel

Civil Service Personnel The Department of State employed over 10,00010,639 Civil Service (CS) employees as of December 2017.31,

2020.57 These employees are among the 2.09 million civilian nonpostalmil ion civilian non-postal employees that the federal government employs.5658 According to the Department of State, "the “Civil Service corps, most of whom are headquartered in Washington, D.C., is involved in virtuallyvirtual y every policy and management area – from democracy and human rights, to narcotics control, trade, and environmental issues. Civil Service employees also serve as the domestic counterpart to Foreign

Service consular officers who issue passports and assist U.S. citizens overseas."57”59 Table 4 shows

the 11 Civil Service job categories within the department and describes each category.

|

Job Category |

Description |

|

Budget Administration |

|

|

Contract Procurement |

|

|

Foreign Affairs |

|

|

Foreign Language and Professional Training |

Foreign Language and

Apply expertise |

|

General Accounting and Administration |

|

|

Human Resources |

Human Resources

Manage, supervise, |

|

Information Technology Management |

|

|

Legal Counsel |

|

|

Management Analysts |

|

|

Passport Visa Services |

Passport Visa Services

Manage, supervise, |

|

Public Affairs |

Public Affairs

Administer, |

audiences

Source: U.S. Department of State, "“Civil Service Job Categories," ” at https://careers.state.gov/work/civil-service/job-categories/.

Department of State Staffing Levels Over Time

The Department of State's staffing levels and global presence have gradually increased throughout American history, experiencing significant growth in the 20th century as the United States assumed a greater leadership role in global affairs. For example, the number of domestic State Department employees increased from 1,128 in 1940 to 3,767 in 1945, while the number of Foreign Service personnel increased from around 1,650 in the years immediately following World War II to 3,436 by the end of 1957.58 More recently, the combined total number of Foreign Service Generalists and Specialists has increased from 11,555 in 2008 to 13,676 in 2017, while the number of Civil Service employees increased from 9,262 to 10,503 over the same period. However, the number of Foreign Service and Civil Service employees at the Department of State declined from December 2016 to December 2017 amid the department's previous efforts to reduce personnel levels (as described in the "State Department Personnel Staffing Levels" subsection below).

Amid these declines, the American Foreign Service Association (AFSA) expressed particular concern regarding reductions in the number of Senior Foreign Service Officers, including those at the rank of Career Minister and Minister Counselor. According to the Department of State, the number of Senior Foreign Service Officers serving at the rank of Career Minister declined from 27 at the end of FY2016 to 19 at the end of FY2017, while the number of those serving at the rank of Minister-Counselor declined from 431 to 385.59 AFSA attributed such declines in part to what it said were department decisions to slash promotions. It added that because the Foreign Service, like the military, recruits officers at the entry level and develops them into senior leaders over a number of years, the Department of State will face significant difficulties replacing lost talent quickly. 60 Department of State officials offered a different assertion, attributing the broader decline in the number of Senior Foreign Service personnel largely to Senate inaction in approving career Senior Foreign Service promotions transmitted for advice and consent.61 See Table 5 for more information comparing the department's personnel levels in 2008 and 2017.

|

Employee Type |

June 30, 2008 |

December 30, 2016 |

December 30, 2017 |

|||

|

Foreign Service Generalists |

|

|

| |||

|

Foreign Service Specialists |

|

|

| |||

|

Civil Service |

|

|

| |||

|

|

|

| |||

|

Total Number of State Department Employees |

|

|

| |||

|

Number of Posts |

|

|

| |||

|

Number of USG Agencies Represented Overseas |

|

|

| |||

|

Number of countries with which the United States has diplomatic relations |

|

|

|

Source: U.S Department of State, Bureau of Human Resources, "HR Fact Sheet: Facts About Our Most Valuable Asset – Our People," fact sheet, June 30, 2008; U.S Department of State, Bureau of Human Resources, "HR Fact Sheet: Facts About Our Most Valuable Asset – Our People," fact sheet, December 30, 2016; U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Human Resources, "HR Fact Sheet: Facts About Our Most Valuable Asset – Our People," fact sheet, December 30, 2017.

a. The June 30, 2008, HR Fact Sheet provides a figure for the number of Foreign Service Nationals employed rather than the number of Locally Employed Staff. The December 30, 2016, and December 30, 2017, HR Fact Sheets note that the "Locally Employed Staff" figure "includes Foreign Service Nationals (FSN) and Personal Service Agreements (PSA)."

Selected Issues for Congress