Runaway and Homeless Youth: Demographics and Programs

Changes from April 26, 2018 to March 26, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Runaway and Homeless Youth: Demographics and Programs

Contents

- Introduction

- Who Are Homeless and Runaway Youth?

- Defining the Population

- Demographics

- Factors Influencing Homelessness and Leaving Home

- Voices of Youth Count

- Other Research

- Factors Influencing Homelessness and Leaving Home

- Challenges Associated with Running Away and Homelessness

- Evolution of Federal Policy

- U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness: Opening Doors

- Runaway and Homeless Youth Program

- Federal Administration and Funding

- Runaway and Homeless Youth Program

- Basic Center Program

- Overview

- Funding Allocation

- Rural Homeless Youth Demonstration

- Transitional Living Program

- Overview

- Maternity Group Homes

- Funding Allocation

- Outcomes of Youth in the TLP

- Special Populations and Rural Homeless Youth Demonstration

- Street Outreach Program

- Overview

- Funding Allocation

- Data Collection Project

- Training and Technical Assistance: RHYTTAC

- National Communication System: National Runaway Safeline

- Oversight

- HHS Oversight

- Congressional Oversight

- Additional Federal Support for Runaway and Homeless Youth

- Educational Assistance

- Elementary and Secondary Education

- Higher Education

- Chafee Foster Care Independence Program

- Discretionary Grants for Family Violence Prevention

Tables

Appendixes

- Appendix

. A. Basic Center Program (BCP) Funding

- Appendix B. Additional Federal Support for Runaway and Homeless Youth

Summary

This report discusses runaway and homeless youth, and the federal response to support this population. There is no single definition of the terms "runaway youth" or "homeless youth." However, both groups of youth share the risk of not having adequate shelter and other provisions, and may engage in harmful behaviors while away from a permanent home. These two groups also include "thrownaway" youth who are asked to leave their homes, and may include other vulnerable youth populations, such as current and former foster youth and youth with mental health or other issues. The term "unaccompanied youth" encompasses both runaways and homeless youth, and is used in national data counts of the population.

Youth most often cite family conflict as the major reason for their homelessness or episodes of running away. A youth's sexual orientation, sexual activity, school problems, and substance abuse are associated with family discord. The precise number of homeless and runaway youth is unknown due to their residential mobility and overlap among the populations. Determining the number of these youth is further complicated by the lack of a standardized methodology for counting the population and inconsistent definitions of what it means to be homeless or a runaway. According to a federally funded study, over 4 million youth ages 13 through 25 experienced a form of homelessness over a 12-month periodThe U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is supporting data collection efforts, known as Voices of Youth Count, to better determine the number of homeless youth. The 2017 study found that approximately 700,000 youth ages 13 to 17 and 3.5 million young adults ages 18 to 25 experienced homelessness within a 12-month period because they were sleeping in places not meant for habitation, in shelters, or with others while lacking alternative living arrangements.

From the early 20th century through the 1960s, the needs of runaway and homeless youth were handled locally through the child welfare agency, juvenile justice courts, or both. The 1970s marked a shift toward federal oversight of programs that help youth who had run afoul of the law, including those who committed status offenses (e.g., running away). Congress and the President enacted thei.e., a noncriminal act that is considered a violation of the law because of the youth's age). The Runaway Youth Act of 1974 was enacted as Title III of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (P.L. 93-415) to assist runaways through services specifically for this population. These services are provided through the federal Runaway and Homeless Youth Program. The program has been updated through reauthorization laws, most recently by the Reconnecting Homeless Youth Act (P.L. 110-378) in 2008. The program is funded through the annual appropriations process. The authorization of appropriations expired in FY2013. Congress and the President have continued to provide funds for the act: $127.4 million was appropriated for FY2018.

The RHYP is a part of larger federal efforts to end youth homelessness through the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). The USICH is a coordinating body made up of multiple federal agencies committed to addressing homelessness. The USICH's Opening Doors plan to end homelessness includes strategies for ending youth homelessness by 2020, including through collecting better data and supporting evidence-based practices to improve youth outcomes. Voices of Youth Count is continuing to report on characteristics of homeless youth. In addition to the RHYP, there are other federal supports to address youth homelessness. HUD's Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program is funding a range of housing options for youth, in selected urban and rural communities. Other federal programs have enabled homeless youth to access services, including those related to education and family violence.The Runaway and Homeless YouthThe act was amended over time to include homeless youth. It authorizes funding for services carried out under the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program (RHYP), which is administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The program was most recently authorized through FY2020 by the Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-385). This law did not make other changes to the RHYP statute. Funding is discretionary, meaning provided through the appropriations process. FY2019 appropriations are $127.4 million.

The RHYP program is made up of three components: the Basic Center Program (BCP), Transitional Living Program (TLP), and Street Outreach Program (SOP). The Basic Center Program BCP provides temporary shelter, counseling, and after care services to runaway and homeless youth under age 18 and their families. The BCP has served approximately 31,000 youth annually in recent years. The Transitional Living Program is targeted to older youth ages 16 through 22 (and sometimes an older age), and has served approximately 6,000 annually in recent yearsIn FY2017, the program served 23,288 youth, and in FY2018 it funded 280 BCP shelters (most recent figures available). The TLP is targeted to older youth ages 16 through 22 (and sometimes an older age). In FY2017, the TLP program served 3,517 youth, and in FY2018 it funded 299 grantees (most recent figures available). Youth who use the TLP receive longer-term housing with supportive services. The SOPSOP provides education, treatment, counseling, and referrals for runaway, homeless, and street youth who have been subjected to, or are at risk of being subjected to, sexual abuse, sex exploitation, and trafficking. In FY2017, the SOP grantees made contact with 24,366 youth.

sexual abuse, sex exploitation, and trafficking. The SOP makes contact with about 36,000 street youth annually.

Related services authorized by the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act include a national communication system to facilitate communication between service providers, runaway youth, and their families; training and technical support for grantees; and evaluations of the programs, among other activities. The 2008 reauthorization expanded the program, requiring HHS to conduct an incidence and prevalence study of runaway and homeless youth. Congress and the President provided appropriations to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for the study, and initial findings were published in 2017. Additional efforts are underway among multiple federal agencies to collect better information on these youth as part of a larger strategy to end youth homelessness by 2020. In addition to the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program, other federal programs support runaway and homeless youth.

Introduction

Running away from home is not a recent phenomenon. Folkloric heroes Huckleberry Finn and Davy Crockett fled their abusive fathers to find adventure and employment. Although some youth today also leave home due to abuse and neglect, they often endure far more negative outcomes than their romanticized counterparts from an earlier era. Without adequate and safe shelter, runaway and homeless youth are vulnerable to engaging in high-risk behaviors and further victimization. Youth who live away from home for extended periods may become removed from school and systems of support that promote positive development. Runaway and homeless youth are vulnerable to multiple problems while they are away from a permanent home, including untreated mental health disorders, drug use, and sexual exploitation. They also report other challenges including poor health and the lack of basic provisions.1

Congress began to hear concerns about the vulnerabilities of the runaway population in the 1970s due to increased awareness about these youth and the establishment of runaway shelters to assist them in returning home. Congress and the President went on to enact the Runaway Youth Act of 1974 as Title III of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (P.L. 93-415) to assist runaways through services specifically for this population. Since that time, the law has been updated to authorize services to provide support for runaway and homeless youth outside of the juvenile justice, mental health, and child welfare systems. 2 The Runaway Youth Act—now known as the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act—authorized federal funding to be provided through annual appropriations for three programs tothat assist runaway and homeless youth—: the Basic Center Program (BCP), Transitional Living Program (TLP), and Street Outreach Program (SOP)—through FY2013.2 Congress and the President have continued to appropriate funding for the three programs. Together, the programs make up the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program (RHYP), administered by the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS) Administration for Children and Families (ACF).

- Basic Center Program: Provides funding to community-based organizations for crisis intervention, temporary shelter, counseling, family unification, and after care services to runaway and homeless youth under age 18 and their families. In some cases, BCP-funded programs may serve older youth.

The program served overOver 31,000 youth participated in FY2016., the most recent year for which data are available.

- Transitional Living Program: Supports

projectscommunity-based organizations that provide homeless youth ages 16 through 22 with stable, safe, longer-term residential services up to 18 months (or longer under certain circumstances), including counseling in basic life skills, building interpersonal skills, educational advancement, job attainment skills, and physical and mental health care.The program served overOver 6,000 youth participated in FY2016. - Street Outreach Program: Provides funding to community-based organizations for street-based outreach and education, including treatment, counseling, provision of information, and referrals for runaway, homeless, and street youth who have been subjected to, or are at risk of being subjected to, sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, prostitution, and trafficking. SOP grantees made contact with more than 36,000 youth in FY2016.

This report begins with an overview of the runaway and homeless youth population.3 The report It then describes the challenges in defining and counting the runaway and homeless youththis population, as well as the factors that influence homelessness and leaving home. The report also provides background on the evolution of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act from the 1970s until it was last amended in 2008. Itfederal efforts to support runaway and homeless youth, including the evolution of federal policies to respond to these youth, with a focus on the period from the Runaway Youth Act of 1974 to the present time. The report then describes the administration and funding of the Basic Center, Transitional Living, and Street Outreach programs that were created from authorizations in the act. Finally, the report discussesThe appendixes include funding information for the BCP program and discuss other federal programs that may be used to assist runaway and homeless youth.

Who Are Homeless and Runaway Youth?

Defining the Population

There is no single federal definition of the terms "homeless youth" or "runaway youth." However, HHS relies on the various definitions from the program's authorizing legislation and its accompanying regulations. The Runaway and Homeless Youth Act defines homeless youth for purposes of the BCP as definitions from the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act in administering the Runaway and Homeless Youth program: The act includes the following definitions:"Homeless youth," for purposes of the BCP, includes individuals under age 18 (or some older age if permitted by state or local law) for whom it is not possible to live in a safe environment with a relative and who lack safe alternative living arrangements. For

"Homeless youth," for purposes of the TLP, homeless youth areincludes individuals ages 16 through 22 for whom it is not possible to live in a safe environment with a relative and who lack safe alternative living arrangements. Youth older than age 22 may participate if they entered the program before age 22 and meet other requirements. The act describes runaway youth as

"Runaway youth" includes individuals under age 18 who absent themselves from their home or legal residence at least overnight without the permission of their parents or legal guardians.

Separately, the McKinney-Vento Act authorizes several federal programs for homeless individuals that are administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The definition of "homeless individual" in McKinney-Vento includesrefers to "unaccompanied youth," which applies to selected homelessness programs. TheHUD's related regulation defines an "unaccompanied youth" as someone under age 25 who meets the definition of "homeless" in the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act or other specified federal laws.43 The regulation also provides additional criteria, including that they have experienced at least 60 days of living independently without permanent housing.5lived independently without permanent housing for at least 60 days.4

The research literature also includesdiscusses definitions of runaway and homeless youth may include a sub-population known as "thrownaway" youth (or "push outs") who have been abandoned by their parents or have been told to leave their households. While studies have often categorized young people based on their status as runaways, thrownawayshomeless, or street youth, a 2011 report suggests that overlap exists between these categories. The authors of the study note that these "typologies," or classifications, are too narrowly defined by the youth's housing status and reasons for homelessness, among other factors. The authors explain that typologies based on mental health status or age cohort are promising, but they suggest further research in this area to ensure that the typologies are accurate.65

Demographics

The precise number of homeless and runaway youth is unknown due to their residential mobility. These youth often eschew the shelter system for locations or areas that are not easily accessible to shelter workers and others who count the homeless and runaways.76 Youth who come into contact with census takers may also be reluctant to report that they have left home or are homeless. Determining the number of homeless and runaway youth is further complicated by the lack of a standardized methodology for counting the population and inconsistent definitions of what it means to be homeless or a runaway.8 Further, some studies examine homelessness based on the age of youth (e.g., under age 18, or 18 and older).

Differences in methodology for collecting data on homeless populations may also influence how the characteristics of the runaway and homeless youth population are reported. Some studies have relied on point prevalence estimates that report whether youth have experienced homelessness at a given point in time, such as on a particular day.9 According to researchers that study the characteristics of runaway and homeless youth, these studies appear to be biased toward describing individuals who experience longer periods of homelessness.10 The sample location may also misrepresent the characteristics of the population generally.11 Youth surveyed in locations with high rates of drug use and sex work, known as "cruise areas," tend to be older, to have been away from home longer, to have recently visited community-based agencies, and to be less likely to attend school than youth in "non-cruise areas."12

Further, the research literature on the number and characteristics of runaway and homeless youth is fairly limited and dated. Some of the studies focus on the demographics of either homeless youth; runaway youth; or unaccompanied youth, who can encompass both runaways and homeless youth. HUD requires communities receiving certain HUD funding to conduct annual point-in-time (PIT) counts of people experiencing homelessness, including homeless youth. In 2017, nearly 41,000 unaccompanied youth under age 25 (4,789 under age 18 and 36,010 ages 18 to 25) were identified in the PIT count. Another 9,436 youth under age 25 were homeless parents.138

Annual Point-in-Time (PIT) Counts

HUD requires communities receiving certain HUD funding to conduct annual point-in-time (PIT) counts of people experiencing homelessness, including homeless youth. The PIT counts include people living in emergency shelter, transitional housing, and on the street or other places not meant for human habitation. It does not include people who are temporarily living with family or friends. In the 2018 PIT count, communities identified 36,361 unaccompanied youth under age 25 (versus 40,799 in 2017) and another 8,724 under age 25 who were homeless parents (versus 9,434 in 2017).9 While PIT counts do not provide a confident estimate of youth experiencing homelessness across the country, they provide some information to communities about the potential scope of youth homelessness.14

The Reconnecting Homeless Youth Act (P.L. 110-378), which renewed authorization of appropriations for the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program through FY2013, also authorized funding for HHS to conduct periodic studies of the incidence and prevalence of youth who have run away or are homeless. TheSeparately, the accompanying conference report to the FY2016 appropriations law (P.L. 114-113) directed HUD to use $2 million to conduct a national incidence and prevalence study of homeless youth as authorized under the Runaway and Homeless Youth program. HUD provided these funds to Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago to carry out the study.15

11 The study, known as Voices of Youth Count, used a nationally representative phone survey A 2010 study on the lifetime prevalence of running away used longitudinal survey data of young people who were 12 to 18 years old when they were first interviewed about whether they had run away—defined as staying away at least one night without their parents' prior knowledge or permission—along with other behaviors.13 In subsequent years, youth who were under age 17 at their previous interview were asked if they had run away since their last interview. Youth who had ever run away were asked how many times they had done so and the age at which they first did. The study found that 19% of those who ran away did so before turning 18; females were more likely than males to run away; and among white, black, and Hispanic youth, black youth have the highest rate of ever running away. Youth who ran away reported that they did so about three times on average; however, about half of runaways had only run away once. Approximately half of the youth had run away before age 14. A subset of runaway youth is those in foster care. In FY2017, over 500 children in the United States had run away from their foster care home or other placement.14 While this represents less than 1% of all children in foster care, running away is more prevalent among older youth in care. A study of over 50,000 youth ages 13 through 17 in 21 states indicated that 17% ran away at least once during their first time in foster care. The study found that female, black, and Hispanic youth were more likely to run away than male and white youth in care. The study further found that youth were more likely to run away from congregate care (i.e., group care) settings compared to other settings, such as living with a relative or in a foster family home. Youth were also more likely to run away from care if they lived in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged counties or lived in a state that lacked a process to screen youth on the risk of running away.15 States report on the characteristics and experiences of certain current and former foster youth through the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD). Among other information, states must report data on cohorts of foster youth beginning when they are age 17, and later at ages 19 and 21. Among youth surveyed in FY2015 at age 21, about 43% reported having experienced homelessness.16forto derive national estimates and conducted brief surveys of youth and in-depth interviews of youth who had experiences of homelessness. The study interviewedphone survey involved interviews with adults whose households had youth and young adults ages 13 to 25 and respondentswith adults ages 18 to 25. Voices of Youth Count foundestimated that approximately 700,000 youth ages 13 to 17 and 3.5 million young adults ages 18 to 25 had experienced homelessness within a one-year period, meaning they were sleeping in places not meant for human habitation, staying in shelters, or temporarily staying with others while lacking a safe and stable alternative living arrangement. This differs from the PIT counts because it includes individuals who are staying with others. The study also found that youth homelessness affectsaffected youth in rural and urban areas at similar levels.1612

Other Research

Factors Influencing Homelessness and Leaving Home

Youth most often cite family conflict as the major reason for their homelessness or episodes of running away. A literature review of homeless youth found that a youth's relationship with a step-parentAccording to the research literature, a youth's poor family dynamics, sexual activity, sexual orientation, pregnancy, school problems, and alcohol and drug use wereare strong predictors of family discord.17 Over oneOne-third of callers who used the National Runaway Safeline in 2016—a federally sponsored2017—a crisis call center funded under the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program for youth and their relatives involved in runaway incidents—gave family dynamics (not defined) as the reason for their call.18

Further, a longitudinal survey of middle school and high school youth examined the effects of family instability (e.g., child maltreatment, lack of parental warmth, and parent rejection) and other factors on the likelihood of running away from home approximately two to six years after youth were initially surveyed. Researchers found that youth with family instability were more likely to run away. Family instability also influenced problem behaviors, such as illicit drug use, which, in turn, were associated with running away. Running away also increased the chances of running again. Researchers further determined that environmentalcertain other effects (e.g., school engagement, neighborhood cohesiveness, physical victimization, and friends' support) were not strong predicators of whether youth in the sample ran away.19

In a study of youth who ran away from foster care between 1993 and 2003, the youth cited three primary reasons why they ran from foster care: to connect with their biological families, express their autonomy and find normalcy, and maintain relationships with nonfamily members.20 The Voices of Youth Count study found that certain youth ages 18 to 25 were at heightened risk of experiencing homelessness, including those. This included youth with less than a high school diploma or GED; who arewere Hispanic or black; who arewere parenting and unmarried; or who areidentified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ).2021 Gay and lesbian youth appear to be at greater risk for homelessness and are overrepresented in the homeless population, due often to experiencing negative reactions from their parents when they come out about their sexuality. The Voices of Youth Count study found that LGBTQ young adults ages 18 to 25 had more than twice the risk of being homeless than their heterosexual peers. Further, LGBTQ youth made up about 20% of young adults who reported homelessness.21 In addition, a nationwide survey of 354 organizations serving homeless youth in 2011 and 2012 found that LGBT youth make up about 40% of their clients.22

Runaway and homeless youth have described abuse and neglect as common experiences. Another study of youth who ran away from foster care between 1993 and 2003 by Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago found that the average likelihood of an individual running away from foster care placements increased over this time period.23 Youth questioned about their runaway experiences cited three primary reasons why they ran from foster care: to connect with their biological families; express their autonomy and find normalcy; and maintain relationships with non-family members. Youth who experience foster care are also vulnerable to homelessness after emancipating from the child welfare system. In a study of 26-year-olds who had emancipated from foster care in three states, approximately 15% had experienced homelessness since their last interview at age 23; slightly over half stated that they had been homeless more than once, and almost one-quarter stated they had been homeless four or more times.24

Under an HHS grant, Youth with Child Welfare Involvement at Risk of Homelessness, the 18 grantees (state, local, and tribal child welfare agencies or community-based organizations) evaluated multiple risk factors for homelessness among child welfare-involved populations: which include those who have had numerous foster care placements, run away from foster care, been placed in a group home, had a history of mental health or behavioral health diagnoses, had juvenile justice involvement, had a history of substance abuse, been emancipated from foster care, and been parenting or fathered a child.24

Challenges Associated with Running Away and HomelessnessRunaway and homeless youth are vulnerable to multiple problems while they are away from a permanent home, including untreated mental health disorders, drug use, and sexual exploitation.25 Studies of homeless youth indicate that they are more likely to experience mental health and substance abuse disorders than their counterparts in the general population. A literature review of studies on psychiatric disorders among homeless youth found high prevalence of conduct disorders, major depression, psychosis, and other disorders.26 A study of participants in the Street Outreach Program found that about 6 out of 10 reported symptoms associated with depression and almost three-fourths reported that they had experienced major trauma, such as physical or sexual abuse or witnessing or being a victim of violence.27 Substance abuse is more prevalent among youth who live on the street, compared to homeless youth who are in shelters. Still, both groups of youth use alcohol or drugs at higher rates than their peers who live in family households, even after researchers control for demographic differences.28

While away from a permanent home, runaway and homeless youth are also vulnerable to sexual exploitation; sex and labor trafficking; and other victimization such as being beaten up, robbed, or otherwise assaulted. Some youth resort to illegal activity including stealing, exchanging sex for food or a place to stay, and selling drugs for survival. Runaway and homeless youth report other challenges including poor health and a lack of basic provisions.29

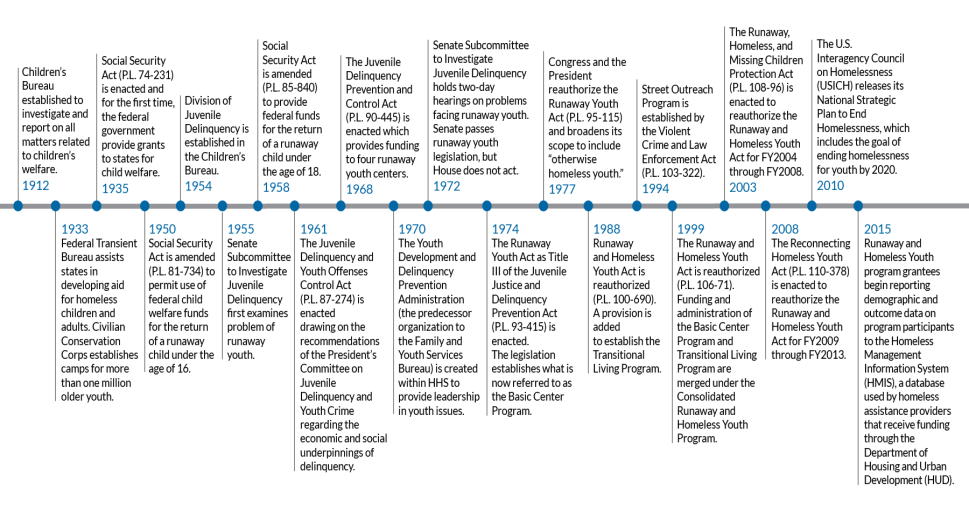

Evolution of Federal Policy

Prior to the enactment of the Runaway Youth Act of 1974 (Title III, Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974, P.L. 93-415), federal policy provided limited services to runaway and homeless youth.30 If they received any services, most of these youth were served through the local child welfare agency, juvenile justice court system, or both. The 1970s marked a shift to a more rehabilitative model for assisting youth who had run afoul of the law, including those who committed status offenses such as running away. During this period, Congress focused increasing attention on runaways and other vulnerable youth due, in part, to emerging sociological models to explain why youth engaged in deviant behavior.31 The first runaway shelters were created in the late 1960s and 1970s to assist them in returning home. The landmark Runaway Youth Act of 1974 decriminalized runaway youth and authorized funding for programs to provide shelter, counseling, and other services. Since the law's enactment, Congress and the President have expanded the services available to both runaway youth and homeless youth under what is now referred to as the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program. In more recent years, other federal entities have been involved in responding to the challenges facing runaway and homeless youth. These efforts are coordinated through the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). Figure 1 traces the evolution of federal policy in this area.

U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness: Opening Doors

The Runaway and Homeless Youth Program is a major part of recent federal efforts to end youth homelessness through the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). (USICH). The USICH, established under the 1987 Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act, is made up of several federal agencies, including HHS and HUD. The HEARTH Act, enacted in 2009 as part of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act (P.L. 111-22), charged USICH with developing a National Strategic Plan to End Homelessness.2532 In June 2010, USICH released this plan, entitled Opening Doors.2633 The plan setsset out goals for ending homelessness, including (1) ending chronic homelessness by 2015; (2) preventing and ending homelessness among veterans by 2015; (3) preventing and ending homelessness for families, youth, and children by 2020; and (4) setting a path to ending all types of homelessness.

Focus on Youth Homelessness

In 2012, USICH amended Opening Doors to specifically address strategies for improving the educational outcomes for children and youth and assisting unaccompanied homeless youth.

27 USICH ultimately intends34 USICH outlined its intention to improve outcomes for youth in four areas: stable housing, permanent connections, education or employment options, and socio-emotional well-being.

In 2013, a USICH working group developed a guiding document for ending youth homelessness by 2020. Known as the Framework to End Youth Homelessness, the document outlines a data strategy to collect better data on the number and characteristics of youth experiencing homelessness. This data strategy includes coordinating the former data collection system for the Runaway and Homeless Youth program—referred to as RHYMIS—with HUD's Homeless Management Information Systems (HMIS). RHYMIS was a data system administered by HHS for previous RHYP grantees to upload demographic and other data for the youth they served. HMIS is a locally administered data system used to record and analyze client, service, and housing data for individuals and families who are homeless or at risk of homelessness in a given community.28

35 As of FY2015, RHYP grantees stopped reporting to RHYMIS and instead report to HMIS. Grantees reported to RHYMIS on the basic demographics of the youth, the services they received, and the status of the youth upon exiting the programs. RHY grantees are now required to report this same (and new information) to HMIS. According to HHS, some grantees have had have encountered inaccurate software programming for their data standards or have had issues with successfully extracting their data to submit to HHS.36

The data strategy outlined in the framework also involves, if funding is available, designing and implementing a national study to estimate the number, needs, and characteristics of youth experiencing homelessness. This is consistent with the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act's directive for HHS to conduct a study of youth homelessness. As noted, this study was first conducted with funding from HUD.

Separately, the framework's capacity strategy seeks —Voices of Youth Count—received funding from FY2016 HUD appropriations. In addition, HHS has supported other research on homeless youth, including factors associated with prolonged homelessness and risk factors for homelessness among children and youth with involvement in child welfare.37 In 2018, the USICH issued a brief that outlines continued gaps in data on the homeless youth population, citing the need for greater understanding about the causes of youth homelessness and how youth enter and exit homelessness.38 Separately, the framework also outlined a strategy to strengthen and coordinate the capacity of federal, state, and local systems to work toward ending youth homelessness. USICH has provided guidance to communities, including by establishing community-level criteria for ending homelessness and accompanying benchmarks to assess whether they have achieved an end to youth homelessness.29

|

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). |

Runaway and Homeless Youth Program

Federal Administration and Funding

As mentioned, the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program is administered by the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB) within HHS's Administration for Children and Families (ACF). The funding streams for the Basic Center Program and Transitional Living Program were separate until they were consolidated as part of reauthorization of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act in 1999 (P.L. 106-71). Under currentRunaway and Homeless Youth Act includes three authorizations of appropriations. The authorization of appropriations for the Basic Center Program and Transitional Living program is $127.4 million for each of FY2019 and FY2020. Under the law, 90% of the federal funds appropriated under the consolidated programtwo programs must be used for the BCP and TLP (together, the programs and their related activities are known as the Consolidated Runaway and Homeless Youth program). Of this amount, 45% is reserved for the BCP and no more than 55% is reserved for the TLP. The remaining share of federalconsolidated funding is allocated for (1) a national communication system to facilitate communication between service providers, runaway youth, and their families (National Safeline); (2) ; (2) training and technical support for grantees; (3) evaluations of the programs; (4) federal coordination efforts on matters relating to the health, education, employment, and housing of these youth; and (5) studies of runaway and homeless youth. The Street Outreach program is funded separately from the BCP and TLP

The authorization of appropriations for the Street Outreach program is $25 million for each of FY2019 and FY2020. Although the SOP is a separately funded component, SOP services are coordinated with those provided under the BCP and TLP.

Table 1 shows funding levels for the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program from FY2002 through FY2018.30 Over this period, funding has notably increased for the program four times—from FY2001 to FY2002; FY2007 to FY2008; FY2015 to FY2016; and FY2017 to FY2018. The first increase was due to the doubling of funding for the Transitional Living Program. Although the TLP authorized services for pregnant and parenting teens prior to FY2002, the Bush Administration sought funds specifically to serve this population and the increased funds were ultimately provided to enable these youth to access TLP services. In FY2003, amendments to the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (P.L. 108-96) authorized TLP funds to be used for services targeted at pregnant and parenting teens at TLP centers known as Maternity Group Homes. The second funding increase was likely due in part to heightened attention to the RHYP, as Congress began to consider legislation in FY2008 to reauthorize the program.

Subsequent funding increases have included the change in BCP and TLP funding from FY2015 ($114.1 million) to FY2016 ($119.1 million) and again from FY2017 ($119.1 million) to FY2018 ($127.4 million). Increases since FY2015 appear to have been made possible because of the overall increase in discretionary spending limits as part of budget deals over this period.31The authorization of appropriations for the periodic estimate of incidence and prevalence of youth homelessness is such sums as may be necessary for FY2019 and FY2020. Funding has not been provided by HHS under this authority, and as noted, funds appropriated to HUD for this purpose have been used to support Voices of Youth Count.Table 1 shows funding levels for the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program from FY2006 through FY2019. Over this period, funding has increased notably for the program three times, most recently from FY2017 to FY2018.41 Congress has provided some guidance on how the additional funds are to be spent. In the accompanying explanatory statementconference report to accompany the FY2018FY2019 consolidated appropriations act, Congress stated that the increase should be provided to current TLP grantees whose awards end on April 30, 2018March 31, 2019. The funding is to be used to continue services until new awards are made to those grantees, or for those grantees that did not receive a new grant, to provide services until the end of FY2018FY2019. Funding may then be used for additional new awards after funds have been set aside to ensure that current grantees are able to operate through the end of FY2018.32.42

Table 1. Runaway and Homeless Youth Program Funding, FY2005-FY2018FY2006-FY2019 (as enacted)

(Dollars in thousands)

|

Program |

2005 | 2006 |

2007a |

2008b |

2009 |

2010 |

2011c |

2012d |

2013e |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 | |

|

BCP | $48,786 BCP |

$48,265 |

$48,298 |

$52,860 |

$53,469 |

$53,744 |

$53,637 |

$53,536 |

$50,097 |

$53,350 |

$53,350 |

$54,439 |

$48 |

$54,439 |

|

|

TLP | 39,938 |

39,511 |

39,539 |

43,268 |

43,765 |

43,990 |

43,902 |

43,819 |

41,004 |

43,650 |

43,650 |

47,541 |

53, |

||

|

SOP |

$55,841 |

15,178 |

15,017 |

15,027 |

17,221 |

17,721 |

17,971 |

17,935 |

17,901 |

16,751 |

17,141 |

17,141 |

17,141 |

17, |

17,141 |

|

Total |

17,141 |

103,902 |

102,793 |

102,864 |

113,349 |

114,955 |

115,705 |

115,474 |

115,256 |

107,852 |

114,141 |

114,141 |

119,121 |

119,121 126,309 |

127,421 |

Source: CRS correspondence with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), January 2019; and HHS, ACF Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, FY2003, p. H-48 (hereinafter, HHS, ACF Justification); HHS, ACF Justification, FY2004, p. H-45; HHS, ACF Justification, , FY2005, p. H-89; HHS, ACF Justification, , FY2006, p. D-41; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2007, p. D-41; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2008, pp. 92, 98; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2009, p. D-42; HHS, ACF Justification FY2010, pp. 85, 92; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2012, pp. 101, 109; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2013, pp. 106, 113; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2014, pp. 105, 114; U.S. HHS, ACF, All-Purpose Table—FY2012-2013; HHS, ACF Justification, FY2016FY2016; and HHS, ACF, ACF Justification, FY2017; HHS, ACF, ACF Justification, FY2019, p. 126; HHS, ACF Operating Plans for FY2016, FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019;; and HHS, ACF, ACF Justification; "FY2017 ACF Operating Plan; and CRS correspondence with HHS, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Legislation, December 2017; and U.S. House of Representatives, Congressional Record, vol. 164, part No. 50, Book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2744.

NotesNotes: BCP and TLP funds are appropriated together under what is known as the Consolidated Runaway and Homeless Youth program. SOP funds are appropriated separately. Appropriation law sometimes refers to the SOP as Prevention Grants to Reduce Abuse of Runaway Youth.

a. The fourth continuing resolution for FY2007 (P.L. 110-5) generally funded programs at their FY2006 levels. However, the FY2006 funding total for the RHYP was slightly lower than the FY2007 total because of an additional transfer of funds from the RHYP accounts to an HHS sub-agency.

b. The FY2008 appropriations includeincluded a 1.7% across-the-board rescission on Labor-HHS-Education programs.

c. The FY2011 appropriations includeincluded a 0.2% across-the-board rescission.

d. The FY2012 appropriations includeincluded a 0.189% across-the-board rescission.

e. The FY2013 appropriations include amounts provided in the final FY2013 appropriations law (P.L. 113-6), an across-the-board rescission of 0.2% required by Section 3004 of the final FY2013 appropriations law (as interpreted by the Office of Management and Budget), reductions required by the sequestration order of March 1, 2013, and any potential transfers or reprogramming of funds pursuant to the authority of the Secretary.

f. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141) provided funding for both the BCP and TLP under a lump sum appropriation for the "Consolidated Runaway, Homeless Youth Program." HHS is to determine the funding allocation for the BCP and TLP according to the requirements in the law.

ga 0.2% across-the-board rescission, reductions required by the sequestration order of March 1, 2013.

f. Since FY2004, the TLP has included funding for the Maternity Group Home component.

Basic Center Program

Overview

The Basic Center Program is intended to provide short-term shelter and services for youth and their families throughat centers operated by BCP grantees, which are public and private community-based centersorganizations. Youth eligible to receive BCP services include those youth who are at risk of running away or becoming homeless (and may live at home with their parents), or have already left home, either voluntarily or involuntarily. To stay at the shelter, youth must be under age 18, or an older age if the BCP center is located in a state or locality that permits this higher age. Some centers may serve homeless youth through street-based services, home-based services, and drug abuse education and prevention services.

As specified in the law, BCP centers are intended to provide these services as an alternative to involving runaway and homeless youth in the law enforcement, juvenile justice, child welfare, and mental health systems. In FY2016, the program provided services to 31,286 youth at 280 BCP shelters in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, and Puerto Rico.33Youth may stay in a center continuously up to 21 days. In FY2017, the program served 23,288 youth, and in FY2018 it funded 280 BCP shelters (most recent figures available).44 These centers, which can shelter as many as 20 youth, are generally supposed to be located in areas that are frequented or easily reached by runaway and homeless youth. The shelters seek to connect youth with their families, whenever possible, or to locate appropriate alternative placements. They also provide food, clothing, individual or group and family counseling, mentoring, and health care referrals. Youth may stay in a center continuously up to 21 days and may re-enter the program multiple times.

BCP grantees—public and private nonprofit organizations—

BCP grantees must make efforts to contact the parents and relatives of runaway and homeless youth. Grantees are also required to establish relationships with law enforcement, health and mental health care, social service, welfare, and school district systems to coordinate services. CentersGrantees maintain confidential statistical records of youth, including youth who are not referred to out-of-home shelter services, and the family members. The centers. Further, grantees are required to submit an annual report to HHS detailing the program activities and the number of youth participating in such activities, as well as information about the operation of the centers.

Funding Allocation

BCP grants are allocated directly to nonprofit entities for grantees for a three-year periodsperiod. Funding is generally distributed to entities based on the proportion of the nation's youth under age 18 in the jurisdiction (50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories) where the entities are located. The 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico34 45 each receive a minimum allotment of $200,000. Separately, the territories (currently, this includes American Samoa and Guam) each receive a minimum of $70,000. The amount of funding for each state or territory can further depend on whether grant applicants in that jurisdiction applied for funding, and if so, whether the applicant fulfilled the requirements in the authorizing law and grant application. For example, the authorizing law directs HHS to give priority to applicants who have demonstrated experience in providing services to runaway and homeless youth. HHS is to re-allot any funds designated for grantees in one state to grantees in other states that will not be obligated before the end of a fiscal year. See the AppendixTable A-1 for the amount of funding allocated for each state in FY2016 and FY2017FY2017 and FY2018. The costs of the BCP are shared by the federal government (90%) and grantees (10%). Grants may be awarded for up to three years.

Rural Homeless Youth Demonstration

In FY2008, HHS began funding a three-year Rural Host Homes Demonstration Project, which was initiated to expand BCP shelter and support services to runaway and homeless youth who live in rural areas not served by shelter facilities. The project supported grantees that provided youth with shelter (via host home families who were recruited, screened, and trained) and preventive services, including transportation, counseling, educational assistance, and aftercare planning, among others. Over the course of the three years, the project served 781 youth, 411 of whom received shelter and 370 of whom received preventive services without shelter. 3546

Transitional Living Program

Overview

Recognizing the difficulty that youth face in becoming self-sufficient adults, the Transitional Living Program provides longer-term shelter and assistance for youth ages 16 through 22 (or older if the youth entered the TLP prior to reaching age 22) who may leave their biological homes due to family conflict, or have left and are not expected to return home. Pregnant and/or parenting youth are eligible for TLP services. In FY2016FY2017, the TLP provided services to 6,054 youth at 2133,517 youth. In FY2018, the program funded 229 organizations.3647

Each TLP grantee may shelter up to 20 youth at longer-term sites (e.g.,various sites, such as host family homes, supervised apartments owned by a social service agency, scattered-site apartments, or single-occupancy apartments rented directly with the assistance of the agency)grantee. Youth may remain at TLP projectssites for up to 540 days (18 months), or longer for youth under age 18. Youth ages 16 through 22 may remain in the program for a continuous period of 635 days (approximately 21 months) under "exceptional circumstances." This term means circumstances in which a youth would benefit to an unusual extent from additional time in the program. A youth in a TLP who has not reached age 18 on the last day of the 635-day period may, in exceptional circumstances and if otherwise qualified for the program, remain in the program until his or her 18th birthday.

Youth receive several types of services at TLP-funded programs:

- basic life-skills training, including consumer education and instruction in budgeting and the use of credit;

- parenting

skillssupport and child care (as appropriate); - building interpersonal skills;

- educational

advancementopportunities, such as GED courses andpost-secondary coursespostsecondary training; - assistance in job preparation and attainment; and

- mental and physical health care services.

TLP centers48TLP grantees are required to develop a written plan designed to help youth transition to living independently or another appropriate living arrangement, and they are to refer youth to other systems that can coordinatehelp to meet their educational, health care, and social service needs. The grantees must also submit an annual report to HHS that includes information regarding the activities carried out with funds and the number and characteristics of the homeless youth.

Maternity Group Homes

As part of the FY2002 budget request, the George W. Bush Administration proposed a $33 million initiative to fund Maternity Group Homesmaternity group homes—or centers that provide shelter to pregnant and parenting teens who are vulnerable to abuse and neglect—as a component of the TLP. The initiative was not funded as part of its FY2002 appropriation. However, that year Congress and the President provided $19.2 million in additional funding to the TLP to ensure that pregnant and parenting teens could access services (H.Rept. 107-376)Although the TLP authorized services for pregnant and parenting teens prior to FY2002, the Bush Administration sought funds specifically to serve this population. Increased funds were ultimately provided to enable these youth to access TLP services. The 2003 amendments to the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (P.L. 108-96) provided explicit authority to use TLP funds for Maternity Group Homesthis purpose. Since FY2004, funding for adult-supervised transitional living arrangements that serve pregnant or parenting women ages 16 to 21 and their children has been awarded to organizations that receive TLP grants. These organizations provide youth with parenting skills, including child development education, family budgeting, health and nutrition, and other skills to promote family well-being.

Funding Allocation

TLP grants are distributed competitively by HHS to community-based public and private organizations throughout the country for a five-year periodsperiod. Grantees must provide at least 10% of the total cost of the program.

Outcomes of Youth in the TLP

Efforts are underway at HHSHHS is carrying out a study to learn more about the long-term outcomes of 1,250 youth who are served by the TLPhave used TLP services. The study seeks to describe the outcomes of youth who participate in the program and to isolate and describe promising practices and other factors that may contribute to their successes or challenges. Of particular interest to the study will be service delivery approaches, youth demographics,for the study is how services are delivered, the demographics of youth, and their socio-emotional wellness, and life experiences. The studyIt involves both a process evaluation and impact evaluation, with youth randomly assigned to the treatment (i.e., participation in the TLP) and control groups. The study seeks to address the following questions: (1) How do TLP programs operate, what types of program models are used to deliver services, and what services are delivered to homeless youth? (2) What are the long-term housing outcomes and protective factors for youth who participate in the TLP program immediately, six months, 12 months, and 18 months after exiting the program? (3) What interventions can be attributed to any positive outcomes experienced by youth who participate in the TLP? HHS expects that the final report of the evaluation will be available in 2019.37

Special Populations and Rural Homeless Youth Demonstration

In FY2016, HHS began the Transitional Living Program Special Population Demonstration project. ThisThe project is fundingfunded nine grantees over a two-year period that are testingtested approaches for serving populations that need additional support: LGBTQ runaway and homeless youth ages 16 to 21; and young adults who have left foster care after the ages of 18 to 21because of emancipation. Grantees arewere expected to provide strategies that help youth build protective factors, such as connections with schools, employment, and appropriate family members and other caring adults. AAccording to HHS, a process evaluation will assess how grantees are implementing the demonstration project.3851

HHS separately funded a project from FY2012 through FY2014 to build the capacity of TLPs in serving LGBTQ youth. Known as the "3/40 Blueprint: Creating the Blueprint to Reduce LGBTQ Youth Homelessness,," the purpose of the grant was to develop information about serving the LGBTQ youth population experiencing homelessness, such as through efforts to identify innovative intervention strategies, determiningdetermine culturally appropriate screening and assessment tools, and better understandingunderstand the needs of LGBTQ youth served by RHY providers.39

In FY2009, HHS began the Support Systems for Rural Homeless Youth Demonstration Project. Six states received grants to support TLPs in rural communities in serving young adults who have few or no connections to a supportive family structure or community resources. The five-year project sought to provide services across three main areas:

- survival support, which includes housing, health care (including mental health), and substance abuse treatment and prevention;

- community, which includes community service, youth and adult partnerships, mentoring, and peer support groups; and

- education and employment, which includes high school or GED completion, postsecondary education, and job training and employment.

Annual grants of $200,000 were awarded toThe six states: —Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Vermont—each received annual grants of $200,000. According to HHS, all of the sites engaged youth in positive youth development activities that included safe places for youth to go. In addition, they raised awareness about homelessness in rural areas and addressed some of the unique needs around employment, housing, and transportation. However, the sites also confirmed that there is a general lack of available housing for homeless youth and that transportation was the most critical impediment to serving these youth.40

Street Outreach Program

Overview

RunawayThe Street Outreach Program provides runaway and homeless youth living on the streets or in areas that increase their risk of using drugs or being subjected to sexual abuse, prostitution, sexual exploitation, and trafficking4155 are eligible to receive services through the Street Outreach Program. The program's goal is to assist youth in transitioning to safe and appropriate living arrangements. SOP services include the following:

- treatment and counseling;

- crisis intervention;

- drug abuse and exploitation prevention and education activities;

- survival aid;

- street-based education and outreach;

- information and referrals; and

- follow-up support.

56Funding Allocation

Grants are awarded for a three-year period, and grantees must provide 10% of the funds to cover the cost of the program. Applicants may apply for a grant each year of the three-year period, with the minimum grant amount in a given year being $100,000, and the maximum $200,000. In FY2016, 103 grantees were funded. Those grantees contacted 36,126 youth.42

Data Collection Project

The Family and Youth Services Bureau createdinitiated the Street Outreach Program Data Collection Project in 2012 to learn more about the lives and needs of homeless and runaway youth served by SOP grantees. The purpose of the project was to design services that willto better meet the needs of these youth. FYSB collected information through focus groups and computer-assisted personal interviews with 656 youth (ages 14 to 21 years) served by SOP grantees in 11 cities. The project found that participants were homeless on average for nearly two years and had challenges with substance abuse, mental health, and exposure to trauma. Youth most identified that they were in need of job training or help finding a job, transportation assistance, and clothing. The top barriers to obtaining shelter were shelters being full, not knowing where to go for shelter, and lacking transportation to get to a shelter. The study researchers concluded that more emergency shelters could help prevent youth from sleeping on the street. Further, they noted that youth on the streets need more intensive case management (e.g., careful assessment and treatment planning, linkages to community resources, etc.) and more intensive interventions.4358

Training and Technical Assistance: RHYTTAC

HHS funds the Runaway and Homeless Youth Training and Technical Assistance Center (RHYTTAC) to provide technical assistance to RHYP grantees. HHS awarded a five-year cooperative agreement, from September 30, 2017, through September 29, 2020, to National Safe Place to operate RHYTTAC.4459 National Safe Place is a national youth outreach program that aims to educate young people about the dangers of running away or trying to resolve difficult, threatening situations on their own. RHYTTAC is designed to provide training and conference services to RHYP grantees that enhance and promote continuous quality improvement to services provided by RHYP grantees. Further, RHYTTAC offers resources and information through its website, tip sheets, a quarterly newsletter, toolkits, sample policies and procedures, and other resources. RHYTTAC also provides assistance to individual grantees in response to their questions or concerns, as well as concerns raised by HHS as part of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program Monitoring System (see subsequent section).45

National Communication System: National Runaway Safeline

A portion of the funds for the BCP, TLP, and related activities—known collectively as the Consolidated Runaway and Homeless Youth Program— are allocated for a national communications system known as the National Runaway Safeline ("Safeline"). The Safeline is intended to help homeless and runaway youth (or youth who are contemplating running away) through counseling, referrals, and communicating with their families. Beginning with FY1974 and every year after, the Safeline, which until 2013 was called the National Runaway Switchboard, has been funded through the Basic Center Program grant or the Consolidated Runaway and Homeless Youth Program grant. The Safeline is located in Chicago and operates each day to provide services to youth and their families across through the country. Services include (1) a channel through which runaway and homeless youth or their parents may leave messages; (2) 24-hour referrals to community resources, including shelter, community food banks, legal assistance, and social services agencies; and (3) crisis intervention counseling to youth.

In calendar year 20162017, the Safeline handled over 33nearly 30,000 contacts with youth (via phone, computer, emails, and postings), of which nearly three-quarters were from youth and 9% were from parents; the remainingother callers were relatives, friends, and others.4661 Other services are also provided through the Safeline. Since 1995, the "Home Free" family reunification program has provided bus tickets for youth ages 12 to 21 to return home or to an alternative placement near their home through Home Free.47

Oversight

HHS Oversight

ACF evaluates each Runaway and Homeless Youth Program grant recipientevaluates each RHYP grantee through the Runaway and Homeless Youth Monitoring System. Staff from regional ACF offices and other grant recipients (known as peer reviewers) inspect the program site, conduct interviews, review case files and other agency documents, and conduct entry and exit conferences. The monitoring team then prepares a written report that identifies the strengths of the program and areas that require corrective action.4863

The Reconnecting Homeless Youth Act of 2008 required that within one year of its enactment (October 8, 2009), HHS was to issue rules that specified performance standards for public and nonprofit entities that receive BCP, TLP, and SOP grants. In developing the regulations, HHS was to consult with stakeholders in the runaway and homeless youth policy community. The law further required that HHS integrate the performance standards into the grantmaking, monitoring, and evaluations processes for the BCP, TLP, and SOP. On April 14, 2014, HHS issued a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) for the new performance standards and other requirements for the Runaway and Homeless youth program grantees.4964 On December 20, 2016, HHS implemented a final rule that was similar to the provisions in the NPRM.5065 These standards are used to monitor individual grantee performance.

Congressional Oversight

The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) and the House Committee on Education and the WorkforceLabor have exercised jurisdiction over the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program. HHS must submit reports biennially to the committees on the status, activities, and accomplishments of program grant recipients and evaluations of the programs performed by HHS. The most recent report was submitted in January 2018, and covered FY2014 and FY2015.51

The 2003 reauthorization law (P.L. 108-96) of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act required that HHS, in consultation with the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, submit a report to Congress on the promising strategies to end youth homelessness within two years of the reauthorization, in October 2005. The report was submitted to Congress in June 2007.52

As mentioned above, the 2008 reauthorization law (P.L. 110-378) required HHS, as of FY2010, to periodically submit to Congress an incidence and prevalence study of runaway and homeless youth ages 13 to 26, as well as the characteristics of a representative sample of these youth. As discussed, Congress appropriated funding to HUD for this purpose and findings were made available in 2017.53

the study, known as Voices of Youth Count, includes multiple publications about its findings.68 The 2008 law also directed the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to evaluate the process by which organizations apply for BCP, TLP, and SOP, including HHS's response to these applicants. GAO submitted a report to Congress in May 2010 on its findings.5469 GAO found weaknesses in several of the procedures for reviewing grants, such as that peer reviewers for the grant did not always have expertise in runaway and homeless youth issues and feedback on grants was not provided in a permanent record. In addition, GAO found that HHS delayed telling successful grantees that the grant had been awarded to them. HHS has implemented the recommendations made in the report.

Additional Federal Support for Runaway and Homeless Youth

Since the creation of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program, other federal initiatives have also established services for such youth.

Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program: The omnibus appropriations laws for FY2016 through FY2018 enabled HUD to set aside up to $33 million (FY2016), $43 million (FY2017), and $80 million (FY2018) from the Homeless Assistance Grants account to implement projects that demonstrate how a "comprehensive approach" can "dramatically reduce" homelessness for youth through age 24. The appropriations laws each fiscal year direct this funding to up to 10 communities with the FY2016 funding; up to 11 communities with the FY2017 funding, including at least five rural communities; and up to 25 communities with the FY2018 funding, including at least eight rural communities. HUD has allocated $33 million to 10 communities for FY2016 and plans to allocate $43 million for FY2017.55

100-Day Challenges to End Youth Homelessness: Since 2016, cities have partnered with public and private entities to accelerate efforts to prevent and end youth homelessness. A Way Home America and Rapid Results Institute, organizations that focus on pressing social problems, have provided support to the organizations. HHS provided training and technical assistance through RHYTTAC to the first three cities involved in the challenge: Los Angeles, CA; Cleveland, OH; and Austin, TX.56 In general, participating communities have housed homeless youth and have identified new housing options for this population.57

Youth At-Risk of Homelessness: HHS has funded grants to build evidence on what works to prevent homelessness among youth and young adults who have child welfare involvement. HHS awarded funds to 18 grantees for a two-year planning period (2013-2015).58 Six of the grantees received additional funding to refine and test their service models during a second phase (2015-2018). A subset of those grantees will then be selected to conduct a rigorous evaluation of their impact on homelessness.59

Educational Assistance

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 (P.L. 100-77), as amended, established the Education for Homeless Children and Youth program in ED.60 This program assists state education agencies (SEAs) to ensure that all homeless children and youth have equal access to the same, appropriate education, including public preschool education, that is provided to other children and youth. Grants made by SEAs to local education agencies (LEAs) under this program must be used to facilitate the enrollment, attendance, and success in school of homeless children and youth. Program funds may be appropriated for activities such as tutoring, supplemental instruction, and referral services for homeless children and youth, as well as providing them with medical, dental, mental, and other health services. Liaison staff for homeless children and youth in each LEA is responsible for coordinating activities for these youth with other entities and agencies, including local Basic Center and Transitional Living Program grantees. States that receive McKinney-Vento funds are prohibited from segregating homeless students from non-homeless students, except for short periods of time for health and safety emergencies or to provide temporary, special, supplemental services.61

Chafee Foster Care Independence Program62

Recently emancipated foster youth are vulnerable to becoming homeless. In FY2015, nearly 21,000 youth "aged out" of foster care.63 The Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP), created under the Chafee Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-169), provides states with funding to support youth who are expected to emancipate from foster care and former foster youth ages 18 to 21.64 States are authorized to receive funds based on their share of the total number of children in foster care nationwide. However, the law's "hold harmless" clause precludes any state from receiving less than the amount of funds it received in FY1998 or $500,000, whichever is greater.65 The program specifies funding for transitional living services, and as much as 30% of the funds may be dedicated to room and board. The program is funded through mandatory spending, and as such $140 million is provided for the program each year through the annual appropriations process.

Discretionary Grants for Family Violence Prevention

The Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA), Title III of the Child Abuse Amendments of 1984 (P.L. 98-457), authorized funds for Family Violence Prevention and Service grants that work to prevent family violence, improve service delivery to address family violence, and increase knowledge and understanding of family violence. From FY2007 to FY2009, one of these projects focused on runaway and homeless youth in dating violence situations through HHS's Domestic Violence/Runaway and Homeless Youth Collaboration on the Prevention of Adolescent Dating Violence initiative. The initiative was created because many runaway and homeless youth come from homes where domestic violence occurs and may be at risk of abusing their partners or becoming victims of abuse.66 The initiative-funded projects carried out by faith-based and charitable organizations that advocated or provided direct services to runaway and homeless youth or victims of domestic violence. The grants funded training for staff at these organizations to enable them to assist youth in preventing dating violence. The initiative resulted in the development of an online toolkit for advocates in the runaway and homeless youth and domestic and sexual assault fields to help programs better address relationship violence with runaway and homeless youth.67

Appendix.

Appendix A.

Basic Center Program (BCP) Funding

Table A-1. Estimated Basic CenterBCP Funding by State and Territory, FY2016 and FY2017

(Dollars in thousands)

|

State/Territory |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

|||

|

Alabama |

$ |

$ |

|||

|

Alaska |

67,185 |

400,000 |

|||

|

Arizona |

796,151 |

799,558 |

|||

|

Arkansas |

575,781 |

551,261 |

|||

|

California |

4,474,818 |

5, |

|||

|

Colorado |

782,693 |

770,279 |

|||

|

Connecticut |

917,161 |

589,225 |

|||

|

Delaware |

400,000 |

109,103 |

|||

|

District of Columbia |

777,816 |

799,722 |

|||

|

Florida |

3, |

2, |

|||

|

Georgia |

1,390,114 |

1, |

|||

|

Hawaii |

|

200,000 |

|||

|

Idaho |

400,000 |

270,593 |

|||

|

Illinois |

2, |

2,107,492 |

|||

|

Indiana |

925,207 |

957,323 |

|||

|

Iowa |

424,650 |

312,882 |

|||

|

Kansas |

347,312 |

315,939 |

|||

|

Kentucky |

685,782 |

794,176 |

|||

|

Louisiana |

813,645 |

818,171 |

|||

|

Maine |

400,000 |

525,304 |

|||

|

Maryland |

400,000 |

396,715 |

|||

|

Massachusetts |

731,837 |

991,352 |

|||

|

Michigan |

2, |

2,227,988 |

|||

|

Minnesota |

1, |

835,852 |

|||

|

Mississippi |

600,000 |

407,623 |

|||

|

Missouri |

1, |

1, |

|||

|

Montana |

199,999 |

200,000 |

|||

|

Nebraska |

359,005 |

600,000 |

|||

|

Nevada |

452,845 |

402,398 |

|||

|

New Hampshire |

321,072 |

200,000 |

|||

|

New Jersey |

1, |

1, |

|||

|

New Mexico |

568,445 |

644,912 |

|||

|

New York |

2, |

2, |

|||

|

North Carolina |

1, |

1, |

|||

|

North Dakota |

399,025 |

200,000 |

|||

|

Ohio |

1, |

1, |

|||

|

Oklahoma |

556,761 |

833,844 |

|||

|

Oregon |

1, |

1, |

|||

|

Pennsylvania |

1, |

1, |

|||

|

Rhode Island |

129,906 |

0 |

|||

|

South Carolina |

400,000 |

399,828 |

|||

|

South Dakota |

527,000 |

321,429 |

|||

|

Tennessee |

1,109,203 |

600,000 |

|||

|

Texas |

3,226,678 |

2,751,415 |

|||

|

Utah |

800,000 |

442,891 |

|||

|

Vermont |

198,746 |

200,000 |

|||

|

Virginia |

870,026 |

999,999 |

|||

|

Washington |

766,901 |

969,997 |

|||

|

West Virginia |

258,385 |

128,769 |

|||

|

Wisconsin |

1,171,894 |

825,245 |

|||

|

Wyoming |

|

|

|||

|

Total for States |

48, |

47,796,300 |

|||

|

American Samoa |

199,768 |

70,000 |

|||

|

Guam |

100,000 | 70,000 Northern Mariana Islands 0 |

|||

|

Puerto Rico |

|

Virgin Islands 0 |

|||

|

Total for Territories |

586,768 |

597,000 |

|||

|

Total |

$ |

$48, |

Source: CRS correspondence with HHS, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Legislation, April 2018U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, FY2020, pp. 133-134.

Note: The total does not include funding for training and technical assistance, research and evaluation, demonstration projects,

a. and program support. Rhode IslandSome jurisdictions received $0 for FY2017 because the single application(Rhode Island, Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands for FY2018) because the applications for funding from organizations in these jurisdictions for funding from

b. the state scored too low to be funded.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Paul A.Toro, Amy Dworsky, and Patrick J. Fowler, Homeless Youth in the United States: Recent Research Findings and Intervention Approaches, HUD, Office of Policy Development and Research, September 2007, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/homeless/p6.html. (Hereinafter, Paul A.Toro, Amy Dworsky, and Patrick J. Fowler, \Homeless Youth in the United States: Recent Research Findings and Intervention Approaches.) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

The Runaway and Homeless Youth Act was most recently reauthorized by the Runaway and Homeless Youth Protection Act (P.L. 110-378). For additional information about the 2008 reauthorization law, see CRS Report RL34483, Runaway and Homeless Youth: Reauthorization Legislation and Issues in the 110th Congress. The law is authorized at 34 U.S.C. §10101 et seq.: Basic Center Program (34 U.S.C. §§11211-11213), Transitional Living Program (34 U.S.C. §§11221 – 11222), and Street Outreach Program (34 U.S.C. §11261). The law refers to the SOP as the Sexual Abuse Prevention program. Accompanying regulations are at 45 C.F.R. §1351 et seq. Information about these program is drawn from statute, congressional budget justifications, reports to Congress, and funding announcements. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

For information about reauthorization, see CRS Report R43766, Runaway and Homeless Youth Act: Current Issues for Reauthorization. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. |

These other programs are not focused on youth per se. The act also authorizes the Education for Homeless Children and Youths program, which is administered by the U.S. Department of Education (ED) and provides supports to assist homeless children and unaccompanied youth in schools. The program defines homelessness in part by reference to the definition of "homeless individual," as well as other criteria. For some of these definitions, see CRS Report RL30442, Homelessness: Targeted Federal Programs. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||