Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Changes from April 24, 2018 to May 6, 2021

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S. Prescription Drug Spending

- How Much Does the United States Spend on Prescription Drugs?

How Does 2016Frequently Asked Questions About May 6, 2021 Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy Suzanne M. Kirchhoff Prescription drugs play an important role in the U.S. health care system. Innovative, Analyst in Health Care breakthrough drugs are providing cures for diseases such as hepatitis C and helping Financing individuals with chronic conditions lead fuller lives. Studies show that prescription drug therapy can produce health care savings by reducing the number of hospitalizations and Agata Bodie other costly medical procedures. Analyst in Health Policy Congress and presidential administrations have attempted to ensure that Americans have Kavya Sekar access to pharmaceuticals by, among other legislation, enacting the Medicare Part D Analyst in Health Policy prescription drug benefit as part of the Medicare Modernization and Prescription Drug Act of 2003 (MMA; P.L. 108-173) and expanding drug coverage under the 2010 Patient Simi V. Siddalingaiah Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended). Congress also Analyst in Health has enacted laws to encourage manufacturing of lower-cost generic drugs, as well as Economics cutting-edge biologics and biosimilars. Americans are using more prescription drugs, and for longer periods of time, than in past decades. Still, access to prescription drugs remains an issue for a number of consumers, particularly those without insurance; those prescribed expensive specialty drugs for treating serious or rare diseases; or those enrolled in private insurance or public health plans that impose high cost-sharing requirements, such as drug deductibles and coinsurance. The pace of U.S. retail prescription drug spending has varied through the decades. Drug spending growth moderated in the early 2000s due in part to an economic recession and the expanded use of lower-cost generic drugs. Drug spending spiked in 2014, due in part to the introduction of expensive new hepatitis C drugs, increasing 13.5% in 2014 and 8.8% in 2015, before slowing to an average of 3.4% annual growth from 2016 through 2019. Although the pace of spending has declined from the 2014 peak, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) forecasts that retail drug spending could average 5.5% annual growth from 2020 through 2028, which would be faster than some other areas of U.S. health care spending in this period. The CMS projections for 2020-2028 are based on a model developed prior to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Future CMS reports will measure the impact of the pandemic. This CRS report addresses frequently asked questions about government and private-sector policies that affect drug prices and availability. Among the prescription drug topics covered are spending trends, federally funded research and development, regulation of direct-to-consumer advertising, legal restrictions on prescription drug reimportation, and federal price negotiation. The report provides a broad overview of the issues, as well as references to more in-depth CRS products. The Appendix provides references to relevant congressional hearings and documents. Congressional Research Service link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 12 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 19 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 24 link to page 25 link to page 27 link to page 27 link to page 33 link to page 36 link to page 39 link to page 41 link to page 44 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 26 link to page 45 link to page 46 link to page 6 link to page 21 link to page 30 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 U.S. Prescription Drug Spending .................................................................................................... 3 How Much Does the United States Spend on Prescription Drugs? .......................................... 3 How Does Current Drug Spending Compare to Other Years? .................................................. 6 What Is Behind the Recent Volatility in Retail Drug Spending? .............................................. 7 Changes in Drug Mix .......................................................................................................... 7 Changes in Drug Prices ....................................................................................................... 8 Drug Utilization ................................................................................................................ 10 Are U.S. Consumer Out-of-Pocket Drug Costs Rising? .......................................................... 11 Government Role in Prescription Drug Spending ......................................................................... 15 How Much U.S. Drug Spending Is Paid by Government Programs? ..................................... 15 How Does the Federal Government Pay For Prescription Drugs? .......................................... 16 Can the HHS Secretary Negotiate Medicare Part D Drug Prices? .......................................... 18 What Are U.S. States Doing to Address Drug Costs? ............................................................. 20 Is U.S. Prescription Drug Spending Higher Than in Other Nations? ...................................... 21 Pharmaceutical Development and Marketing ................................................................................ 23 How Much Does Publicly Funded Research Contribute to Drug Development? ................... 23 How Much Does It Cost to Develop New Drugs? .................................................................. 29 Is There a Relationship Between Development Costs and Drug Prices? ................................ 32 Can the FDA Regulate Prescription Drug Prices?................................................................... 35 May U.S. Consumers Import Drugs from Abroad?................................................................. 37 How are Prescription Drug Ads Regulated? ........................................................................... 40 Figures Figure 1. National Retail Prescription Drug Spending .................................................................... 5 Figure 2. Annual Percentage Change in Retail Prescription Drug Spending .................................. 6 Figure 3. U.S. Retail Prescription Drug Price Inflation ................................................................... 9 Figure 4. Consumer Out-of-Pocket Spending as a Share of Retail Drug Spending ...................... 12 Figure 5. Per Capita Out-of-Pocket Spending for Retail Prescription Drugs ................................ 15 Figure 6. Share of Spending for Retail Prescription Drugs by Source .......................................... 16 Figure 7. Per Capita Spending on Retail Drugs in U.S. and Other Countries ............................... 22 Figure 8. Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising ...................................................... 41 Figure 9. Number of Prescription Drug Ads Reviewed by FDA ................................................... 42 Tables Table 1. Commonly Used Prescription Drug Terms ........................................................................ 2 Table 2. Selected Federal Programs Providing Prescription Drug Coverage ................................ 17 Table 3. Findings from Studies on Direct Public Sector Contributions to New Drugs ................. 26 Congressional Research Service link to page 48 link to page 48 link to page 53 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy Appendixes Appendix. Relevant Congressional Drug Pricing Hearings in the 117th, 116th, 115th and 114th Congresses ......................................................................................................................... 44 Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 49 Congressional Research Service link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 48 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy IntroductionDrug Spending Compare to Other Years?- What Is Behind the Recent Volatility in Retail Drug Spending?

- Changes in Drug Mix

- Changes in Drug Prices

- Drug Utilization

- Are U.S. Consumer Out-of-Pocket Drug Costs Rising?

- Government Role in Prescription Drug Spending

- How Much U.S. Drug Spending Is Paid by Government Programs?

- How Does the Federal Government Pay For Prescription Drugs?

- Can the HHS Secretary Negotiate Medicare Part D Drug Prices?

- What Are U.S. States Doing to Address Drug Costs?

- Is U.S. Prescription Drug Spending Higher Than in Other Nations?

- Pharmaceutical Development and Marketing

- How Much Does Publicly Funded Research Contribute to Drug Development?

- How Much Does It Cost to Develop New Drugs?

- Does Congress Regulate Prescription Drug Ads?

- May U.S. Consumers Import Drugs from Abroad?

Figures

- Figure 1. National Retail Prescription Drug Spending

- Figure 2. Annual Percentage Change in Retail Prescription Drug Spending

- Figure 3. U.S. Retail Prescription Drug Price Inflation

- Figure 4. Consumer Out-of-Pocket Spending as a Share of Retail Drug Spending

- Figure 5. Per Capita Out-of-Pocket Spending for Retail Prescription Drugs

- Figure 6. Share of Spending for Retail Prescription Drugs by Source

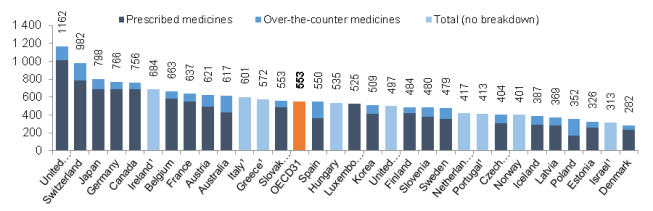

- Figure 7. Per Capita Spending on Retail Drugs in U.S. and Other Countries

- Figure 8. Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising

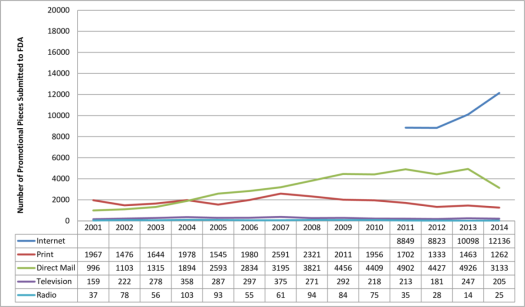

- Figure 9. Number of Prescription Drug Ads Reviewed by FDA

Tables

Summary

Prescription drugs play an important role in the U.S. health care system. Innovative, breakthrough drugs are providing cures for diseases such as hepatitis C and helping individuals with chronic conditions lead fuller lives. Studies show that prescription drug therapy can produce savings for the broader health care savingssystem by reducing the number of hospitalizations and other costly medical procedures.

Americans are using more prescription drugs, and for longer periods of time, than in past decades. Still, access to prescription drugs remains an issue for a number of consumers, particularly those without insurance; those enrolled in private insurance or public health plans that impose high cost-sharing requirements, such as drug deductibles and coinsurance; and those prescribed expensive specialty drugs for treating serious or rare diseases. Specialty drugs, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars or more for a course of treatment, made up less than 3% of total prescriptions, but nearly 40% of retail and mail-order prescription drug spending, net of rebates in 2016-2017, according to one study.1 (See “Drug Price Transparency” textbox below.)

Retail prescription drug spending has varied over the years. Spending moderated in the early 2000s due in part to an economic recession, and the expanded use of lower-cost generic drugs. Spending has increased at a faster rate in recent years, as manufacturers have introduced new drugs at a record rate and have raised prices for existing brand-name products. (See “What Is Behind the Recent Volatility in Retail Drug Spending?”)

Overall, annual spending for outpatient (retail) drugs jumped 13.5% in 2014 and 8.8% in 2015, before slowing to an average 3.4% annual rate of growth from 2016-2019, including an increase of 5.7% in 2019.2 Although the pace of spending has declined from the 2014 peak, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) forecasts that retail drug spending could average 5.5% annual growth from 2020 through 2028, which is faster than some other areas of U.S. health care spending in this period.3 However, the CMS projections for 2020-2028 are based on models developed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Future CMS reports will measure the impact of the pandemic.

This CRS report addressesmedical procedures.

Congress and presidential administrations have attempted to ensure that Americans have access to pharmaceuticals by enacting the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit as part of the Medicare Modernization and Prescription Drug Act of 2003 (MMA; P.L. 108-173) and expanding drug coverage under the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended). Congress also has enacted laws to encourage manufacturing of lower-cost generic drugs, as well as cutting-edge biologics and biosimilars.

Americans are using more prescription drugs, and for longer periods of time, than in past decades. Still, access to prescription drugs remains an issue for a number of consumers, particularly those without insurance; those prescribed expensive specialty drugs for treating serious or rare diseases; or those enrolled in private insurance or public health plans with high cost-sharing requirements, such as drug deductibles and coinsurance.

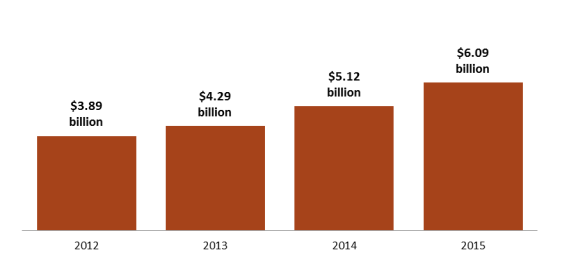

Prescription drug affordability has gained renewed attention during the past few years as retail drug spending has risen at the fastest pace in more than a decade—growing 12.4% in 2014 and 8.9% in 2015 before slowing to a 1.3% increase in 2016. There are several reasons for the recent volatility in drug spending. Manufacturers have been introducing new drugs at a record rate and raising prices for many existing brand-name products. The introduction of new hepatitis C drugs at the end of 2013 had a major impact on total drug spending in 2014 and 2015. At the same time, fewer brand-name drugs have lost patent protection than in previous years, resulting in less impact from the use of lower-cost generic substitutes. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) forecasts that retail drug spending could average 6.3% annual growth from 2017 to 2026. Although that growth rate would be a reduction from the average level of the past several years, CMS expects retail drug spending to increase faster than other areas of medical spending in this 10-year period.

This report will address frequently asked questions about government and private-sector policies that affect drug prices and availability. Among the prescription drug topics covered are spending trends, federally funded research and development, regulation of direct-to-consumer advertising, legal restrictions on drug reimportation, and federal price negotiation. The report provides a broad overview of the issues as well asand references to more in-depth CRS products. The appendix Appendix provides references to relevant congressional hearings.

1 Steven Hill, Edward Miller, and Yao Ding, “Net Spending On Retail Specialty Drugs Grew Rapidly, Especially For Private Insurance And Medicare Part D,” Health Affairs, vol. 39, no. 11, November 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01830. The research looks at net spending after rebates. The authors said their work complemented other research, such as findings by the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science that in 2018 specialty drugs accounted for approximately half of combined gross spending on retail, mail-order, and provider-administered drugs.

2 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), “National Health Expenditure Data: Historical,” Table 16, available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical, and “National Health Expenditure Data: Projected,” Table 11, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected. Also see Sean Keehan et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019–28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth,” Health Affairs, March 24, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094.

3 Ibid.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 7 link to page 7 link to page 7 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Table 1. Commonly Used Prescription Drug Terms

Term

Definition

Biologic

provides references to relevant congressional hearings and documents (see Appendix).

Introduction

Prescription drug affordability has gained renewed attention in the past few years, as retail drug spending has risen at the fastest pace in more than a decade. There are several reasons for the increase in drug spending. Manufacturers have been introducing new drugs at a record rate and raising prices for existing brand-name products. (See "What Is Behind the Recent Volatility in Retail Drug Spending?," below.) At the same time, fewer brand-name drugs have lost patent protection than in previous years, which has meant lower savings from new generic substitutes. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) forecasts that retail drug spending could average 6.3% annual growth from 2017 to 2026.1 Although that growth rate would be a reduction from recent, more rapid levels, CMS expects retail drug spending to increase faster than other areas of medical spending in this 10-year period.

This report will address frequently asked questions about government and private-sector policies that affect drug prices and availability. Among the prescription drug topics covered are federally funded research and development, regulation of direct-to-consumer advertising, legal restrictions on reimportation, and federal price negotiation. The report provides a broad overview of the issues and references to more in-depth CRS products. The appendix provides references to relevant congressional hearings (see Appendix).

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Biologic |

Pharmaceuticals derived from a living organism that can be many times the size of a conventional (small-molecule) drug and have a more complex |

|

Biosimiliar |

structure.a

Biosimilar

A follow-on to a biologic that is |

|

Brand-Name Drug |

A drug marketed under a proprietary, trademark-protected name. |

|

Coinsurance |

The percentage share that an enrollee in a health insurance plan pays for a product or service covered by the plan. For example, an insurer may charge 10% coinsurance for a $100 prescription drug, meaning the consumer |

|

Co-payment |

Co-payment A fixed dollar amount that an enrollee in a health insurance plan pays for a product or service covered by the plan. For example, an insurer may charge a $20 co-payment for a physician visit or a $5 co-payment for a prescription drug. |

|

Deductible |

Deductible The amount an enrollee is required to pay for health care services or products before his or her insurance plan begins to provide coverage. An enrollee in an insurance plan with a $500 deductible would be responsible for paying for the first $500 in health care services. In some insurance plans, the deductible does not apply to certain services, such as preventive care. Insurance plans vary regarding whether beneficiaries must meet a deductible for prescription drug coverage. |

|

Generic Drug |

Generic Drug

A drug that is identical to a traditional (small molecule) brand-name drug in dosage, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use. Generic drugs generally cost significantly less than their brand-name |

|

Formulary |

counterparts.b

Formulary

A list of prescription drugs covered by an insurance plan. In an effort to control costs, insurers are imposing partially closed formularies, which include a more limited number of drugs than open formularies. Insurers use tiered cost sharing for formulary drugs, meaning patients are charged lower co-payments or coinsurance for less expensive generic drugs and certain brand-name drugs that are designated by the plan as preferred drugs, based on the price the plan has negotiated with the manufacturer and the

effectiveness of the product. At the same time, patients are charged higher co-payments or coinsurance for more expensive drugs or drugs that the plan deems to be less effective.

Orphan Drug

|

|

Orphan Drug |

A traditional drug or biologic for the treatment of rare diseases and disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States or that affect more than 200,000 people but where manufacturers are not expected to recover the costs of developing and

marketing a treatment drug. Manufacturers of orphan drugs are eligible for federal tax, marketing, and other incentives.c

Out-of-Pocket Costs

|

|

Out-of-Pocket Costs |

The total amount an insured consumer pays each year for covered health care services that are not reimbursed by an insurance plan. Out-of-pocket costs can include deductibles, co-payments, and coinsurance. |

|

Out-of-Pocket Maximum |

Out-of-Pocket The maximum amount an enrollee must pay before his or her health insurance plan Maximum covers 100% of health benefits. Certain costs, such as premiums, generally are not counted toward an out-of-pocket maximum, or cap. |

|

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) |

Pharmacy Benefit Intermediaries between health plans and pharmacies, drug wholesalers, and Managers (PBMs) manufacturers. PBMs perform functions such as designing drug formularies, negotiating prices, and administering prescription drug payment systems. |

|

Pharmacy Network |

Congressional Research Service 2 link to page 7 link to page 7 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy Term Definition Pharmacy Network A group of retail, mail-order, and specialty pharmacies that contract with PBMs and health insurers to dispense covered drugs at set prices. Network pharmacies also may provide other services under contract, such as monitoring patient adherence to drugs. |

|

Premium |

Premium The amount an enrollee pays for health insurance coverage. Many plans charge monthly premiums, but premiums also can be assessed on a quarterly or annual basis. |

|

Specialty Drug |

Specialty Drug

There is no one set definition of specialty drugs, although insurers and other health care payers often characterize them as prescription products requiring extra handling or administration that are used to treat rare and/or complex diseases, such as cancer. High cost can trigger a specialty drug designation. Biologics are often deemed |

|

Underinsured |

specialty drugs.d

Underinsured

Refers to people who have insurance but still have financial difficulty paying for prescription drugs or medical |

treatments.e Source: CRS.

a. See CRS Report R44620, Biologics and Biosimilars: Background and Key Issues, by Judith A. Johnson.

b. . b. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), "“Generic Drugs,"” at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/genericdrugs/default.htmdrugs/buying-using-

medicine-safely/generic-drugs. In 1984, Congress enacted the Hatch-Waxman Act (P.L. 98-417), which provided manufacturers of innovative prescription drugs with patent protection and a period of marketing exclusivity, created a generic drug approval process to help companies bring products to market more quickly once the patent for an original brand-name drug expired, and established procedures for resolving patent disputes arising from applications to market generic drugs. Generic drugs make up about 8990% of filled prescriptions and 2620% of total drug spending. See Association for Accessible Medications, 2017 2020 Generic Drug & Biosimilars Access & Savings in the United States Report in the U.S., at https://www.accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/2017-generic-drug-access-and-savings-us-report.

c. FDA, "accessiblemeds.org/2020-Access-Savings-Report.

c. FDA, “Developing Products for Rare Diseases & Conditions,"” at https at http://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/DevelopingProductsforRareDiseasesConditions/ucm2005525.htm.

d. ://www.fda.gov/industry/developing-

products-rare-diseases-conditions.

d. See CRS Report R44132, Specialty Drugs: Background and Policy Concerns.

e. There are different definitions of underinsurance. For example, the Commonwealth Fund defines individuals

as underinsured if they had health insurance but still had total out-of-pocket costs or deductibles that were high relative to their incomes. See Commonwealth Fund, "Underinsured Rate Increased Sharply in 2016; More Than Two of Five Marketplace Enrollees and a Quarter of People with Employer Health Insurance Plans Are Now Underinsured," October 18, 2017, at http“Underinsured Rate Rose From 2014-2018, With Greatest Growth Among People in Employer Health Plans,” February 7, 2019, at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/press-release/2019/underinsured-rate-rose-2014-2018-greatest-growth-among-people-employer-health.

://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/press-releases/2017/oct/underinsured-press-release.

U.S. Prescription Drug Spending

How Much Does the United States Spend on Prescription Drugs?

The most commonly cited data on prescription drug spending come from the National Health Expenditures (NHE) accounts compiled by CMS.24 The NHE accounts track annual spending by all payers for prescription drugs purchased in retail settings, such as pharmacies, mail-order outlets, grocery stores, warehouse clubs, and similar businesses. The NHE data do not include

4 CMS, “National Health Expenditure Projections 2019-2028,” at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected. The National Health Expenditures (NHE) data incorporate information from the U.S. Census Bureau and IQVIA, a private firm that provides consulting, technology, and other services for the health care industry. The figures include retail sales of prescription drugs, subtract manufacturer rebates, and add in government spending for drugs provided by government-owned mail-order facilities.

Congressional Research Service

3

link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

drugs dispensed in institutions including hospitals, long-term care facilities, and clinics,35 nor do they include over-the-counter products such as aspirin purchased without a prescription.4

6

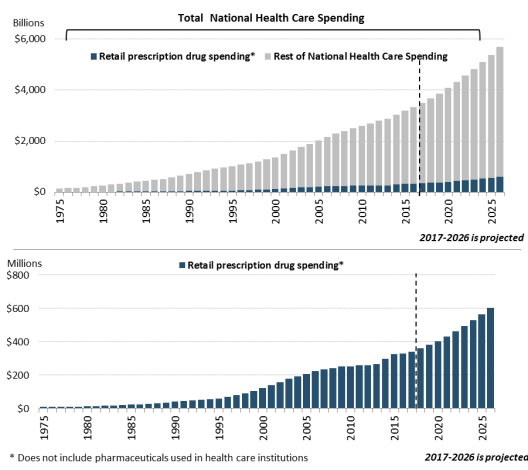

According to the most recent NHE data, the United States spent $328.6369.7 billion on prescription drugs in 20162019 and a forecast $338.1projected $358.7 billion in 20172020, or 10% of predicted 2017 national health care spending of $3.5 trillion.5about 9% of the forecast of $4 trillion in 2020 national health care spending.7 Prescription drug spending is forecast to rise toremain at about 11% 9% of national health care spending by 2027 (see Figure 1). through 2028, down slightly from a prior average of about 10% of health care spending (see Figure 1).

Retail drug spending has ranged from about 5% to 10% of total health care expenditures since 1960, when the NHE accounts began compiling prescription spending data.68 (See "“How Does 2016Current Drug Spending Compare to Other Years?") ”) Because the NHE data provide information about retail drug sales only, a number of analysts say the data do not offer a complete picture of U.S. drug spending. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in April 2016 issued a study that attempted to estimate total U.S. prescription drug spending—retail plus institutional use in hospitals and other health facilities.7

9

5 Although spending for drugs in institutional settings is not included in the NHE retail prescription drug category, it is included in other categories of spending and in overall national health care spending. For example, drugs dispensed in hospitals are included in the NHE hospital spending category.

6 Many over-the-counter products originally were prescription products, such as some antihistamines. See U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), “Now Available without a Prescription,” at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-information-consumers/now-available-without-prescription.

7 CMS, “National Health Expenditure Projections 2019-2028,” at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected; and “National Health Expenditure Data: Historical,” at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. The NHE projects national health care spending of $6.2 trillion in 2028, including $560 billion in retail drug spending. Sean Keehan et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019–28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth,” Health Affairs, March 24, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094. (CMS updated its historic spending data after the Health Affairs article was published to provide actual data, rather than projections, for 2019. This report uses the most updated historic data for prescription drug spending. The historic data showed higher drug spending for 2019 than had been earlier projected by CMS, while the 2020-2028 projections are based on data developed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

8 According to the NHE, retail prescription drug spending was 10% of national health expenditures in 1960. Retail drug spending declined to less than 5% of national health expenditures from 1960 to 1982. During this period, other areas of medical spending were increasing more quickly than drug spending due to the creation of government health programs such as Medicare and Medicaid and the expansion of private health insurance. Retail drug spending began to increase as a share of national health spending in the mid-1980s, due to price inflation and growing consumption. By the early 2000s, retail drug spending had once again reached about 10% of national health care expenditures. See Cynthia Smith, “Retail Prescription Drug Spending in the National Health Accounts,” Health Affairs, vol. 233, no. 1 (January/February 2004), pp. 160-167, at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.160.

9 Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Observations on Trends in Prescription Drug Spending,” March 8, 2016, at https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/observations-trends-prescription-drug-spending. The HHS estimate is based on NHE retail prescription drug data and an outside analysis by the Altarum Institute, a nonprofit health systems research and consulting organization. According to Altarum, nonretail, or institutional, drug spending accounts for 28% of prescription drug spending and retail drugs account for 72% The HHS study provided estimates of total prescription drug spending as a share of U.S. personal health expenditures. Personal health expenditures are a subset of the NHE accounts that measure the amount spent each year to treat people with specific medical conditions. Personal health expenditures do not include some areas of spending included in the broader definition of national health expenditures, such as industry investment and public health activity. According to HHS, total prescription drug spending was projected to account for nearly 17% of personal health expenditures in 2016. The comparable measure for retail prescription drugs was 12%.

Congressional Research Service

4

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Figure 1. National Retail Prescription Drug Spending

(Annual spending for retail drugs as a percentage of total health spending)

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), National Health Expenditure (NHE) data: Historical and Projected. Note: Figures through 2019 are actual; 2020-2028 are forecasts.

In addition to the NHE data, private consultants and academics publish their own forecasts of U.S. prescription drug spending.810 National estimates vary for a number of reasons, including assumptions about the dollar value of rebates that pharmaceutical manufacturers provide to health payers, as well as the value of coupons offered to consumers, and whether the forecasts include both retail and institutional use. However, the different studies show a trend toward higher spending in recent years.

How Does 2016similar spending trends in recent years.

10 IQVIA estimates that prescription drug spending, based on list prices set by manufacturers, was $671 billion in 2019, growing at a 7.1% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the previous five years. According to IQVIA, payer net spending is calculated after supply chain discounts, manufacturer rebates, and patient out-of-pocket costs are deducted, and markups and margins by intermediaries are added. Total net payer spending in 2019 was $509 billion and had increased at a CAGR of 4.1% over the previous five years. See IQVIA Institute, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” Overview, p. 2, August 2020. Available at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-us. Also see Eric Tichy et al., “National Trends in Prescription Drug Expenditures and Projections for 2020,” American Journal of Health System Pharmacies, vol. 77 (May 15, 2020), at https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article-abstract/77/15/1213/5837520.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 10 link to page 6 link to page 11 link to page 11

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

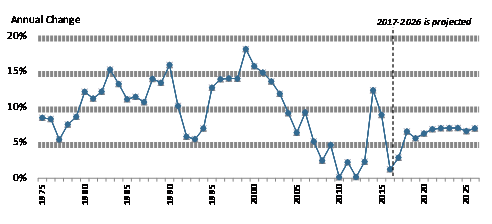

How Does Current Drug Spending Compare to Other Years? Drug Spending Compare to Other Years?

The pace of U.S. retail prescription drug spending has varied through the decades. For much of the 1980s through the early 2000s, retail drug spending grew at a double-digit annual pace. From 2003 through 2013, drug spending slowed to a historically low average annual growth rate of 5%.9 about 5%.11 (See Figure 2.) Drug spending growth moderated for a number of reasons during this period, including a deep economic recession from 2007 to 2010, a reduction in the number of expensive new drugs coming to the market compared to earlier years, and a continued expansion in the use of lower-cost generic drugs.10 12 (See Table 1.)

However, in 2014, spending for retail prescription drugs accelerated. U.S. retail drug spending jumped by 12.4% in 20142019 are actual; 2020-2028 are forecasts.

Spending for retail prescription drugs accelerated in 2014, jumping by 13.5%—the largest annual increase in more than a decade. Drug spending rose by 8.98% in 2015 before slowing to a 1.3% increase in 2016 and a forecasted 2.9% increase in 2017.11 (See "pace of a 3.4% annual rate of growth from 2016 to 2019.13 (See “What Is Behind the Recent Volatility in Retail Drug Spending?” below.) According to CMS, a 5.7% increase in spending in 2019 was influenced by growing utilization, including use of drugs for autoimmune disorders, cancer, and diabetes.14

11 Aaron Catlin and Cathy Cowan, History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013, Health Affairs, November 23, 2015, at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20151123.051904/full/. The implementation of Medicare Part D in 2006 caused a spike in prescription drug spending that year.

12 Ibid., p. 23. 13 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), “National Health Expenditure Data: Historical,” at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical, and “National Health Expenditure Data: Projected,” https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected. Also see Sean Keehan et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019–28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth,” Health Affairs, March 24, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094.

14 Anne Martin, Micah Hartman, David Lassman, Aaron Catlin, “National Health Care Spending In 2019: Steady Growth for the Fourth Consecutive Year,” Health Affairs, December 16, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02022.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 48 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Retail drug spending is projected to grow by about 5.5% a year on average from 2020 through 2028, according to the NHE, due partly to faster projected drug price growth and growing intensity of use.15 That is in line with NHE projections for overall U.S. health care spending to grow at a 5.4% annual rate from 2019 to 2028. The CMS projections are based on data developed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

During recent Congresses, lawmakers held a series of hearings Retail Drug Spending?," below.)12 Retail drug spending is projected to grow by about 6.3% a year on average through 2027, according to the NHE, due partly to faster projected drug price growth, particularly for costlier specialty drugs. Although that growth rate would be a reduction from the recent pace, drugs would be expected to grow faster than other areas of health care spending. For example, the NHE accounts project that physician services and hospital care will grow 5% and 5.5% on average, respectively, over the same time period.13

During the 114th and 115th Congresses, a series of hearings have been held on prescription drugs in response to the mid-2010’sto the acceleration in spending and continued, sharp increases in prices for specific certain drugs. (See partial list of hearings in Appendix. The list focuses on hearings most relevant to drug pricing issues.)

What Is Behind the Recent Volatility in Retail Drug Spending?

Retail As discussed below, retail prescription drug spending can be affected by (1) changes in the mix of available drugs in the marketplace, (2) changes in the price of drugs, and (3) changes in the volume of drugs used. The rapid increase in retail drug spending in 2014 and 2015 was driven largely by the introduction of new high-cost drugs, price increases for existing drugs, and the diminishing impact of generic substitution, as fewer brand-name drugs lost patent protection than in previous years. Implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; ACA (P.L. 111-148, as amended) also helped to propel boost drug demand.14 The rate16 The slower pace of prescription drug spending since 2015 is due to factors that include reduced use and prices for expensive hepatitis C drugs.17

Looking forward, CMS expects retail prescription drug spending to be propelled by faster drug price increases and higher growth in use and intensity. Other factors contributing to this projected increase include the aging of the population and the expected introduction of new drugs for such conditions as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.18

of prescription drug spending slowed in 2016, even though overall utilization rose during that year, due to factors that included fewer new drug approvals than in previous years, less use of high-cost hepatitis C drugs, and a deceleration in spending for drugs to treat diabetes.15

Changes in Drug Mix

Changes in Drug Mix

Drug mix refers to the composition of the different types of drugs being utilized in the retail marketplace, specifically focused on the availability and Drug mix refers to the cost of new drugs versus the costthose of older drugs being used. New, innovator brand-name drugs often are more expensive than older drugs and do not have lower-cost equivalents. Likewise, newly introduced generic drugs, which are less expensive than brand-name products, can reduce the cost of certain therapies.

During the past several years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a large number of novel new drugs,16 including expensive specialty drugs for treating hepatitis C, cancer, diabetes, and heart disease.17 In 2016 alone, more than half of the growth in U.S. prescription drug spending was from drugs that had been available for less than two years.18 The introduction of new hepatitis C drugs, which can cure the disease, played a large role in increased drug spending in 2014 and 2015, accounting including a number of specialty drug products.19 The 15 Sean Keehan et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019–28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth,” Health Affairs, March 24, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094. (CMS updated its historic spending data after the Health Affairs article was published to provide actual data, rather than projections, for 2019. This report uses the most updated historic data for prescription drug spending.)

16 Anne B. Martin et al., “National Health Spending In 2014: Faster Growth Driven by Coverage Expansion and Prescription Drug Spending,” Health Affairs, vol. 35, no.1 (December 2, 2015), pp. 150-160, at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1194; and Anne Martin et al., “National Health Spending: Faster Growth In 2015 As Coverage Expands and Utilization Increases,” Health Affairs, vol. 26, no. 1 (January 2017). 17 Sean Keehan et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2019–28: Expected Rebound in Prices Drives Rising Spending Growth,” Health Affairs, March 24, 2020, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00094.

18 Andrea Sisko et al., “National Health Expenditure Projections, 2018-27: Economic and Demographic Trends Drive Spending and Enrollment Growth,” Health Affairs, February 20, 2019, at https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05499.

19 FDA approved 53 novel drugs in 2020, 48 novel drugs in 2019, 59 novel drugs in 2018, 46 novel drugs in 2017, 22 in 2016, and 45 in 2015. See FDA, “Novel Drug Approvals for 2020,” at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 13 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

introduction of a new generation of hepatitis C drugs alone, which can cure the disease, accounted for nearly 40% of the net growth in total U.S. drug spending in 2014 and two-thirds of increased brand-name prescription drug spending by employer-sponsored health plans that year.1920 The outsized impact of the hepatitis C drugs, while still large,drugs is diminishing as fewer new patients are treated with the products and new competing products come on the market, affecting prices. However, growth in the number of newly introduced drugs and increased use of high-cost specialty drugs, continue to have an outsized impact on spending.

For example, according to the analytics and consulting firm IQVIA, U.S. net pharmaceutical revenues rose from $300 billion in 2014 to $356 billion in 2019. There were partially offsetting trends in pricing and utilization during that period. For example, new drug launches contributed $68 billion to net manufacturer revenue growth during the period, price increases for brand drugs with marketing or patent protection21 contributed $21 billion, and volume growth for protected brands contributed $40 billion. At the same time, a loss of marketing and patent exclusivity, paving the way for generic production, and changes in the volume and price of generics reduced manufacturer net revenues by $73 billion.22 Many protected brand drugs are specialty drugs.

the products and net prices drop for the drugs.20

At the same time that these expensive new drugs were coming to the market, new generic substitution was playing a smaller role in reducing total drug spending. Since 2009, patents for a number of best-selling brand-name drugs have expired, paving the way for manufacturers to produce new generic versions.21 In 2012, at the peak of the so-called patent cliff, spending for brand-name drugs subject to generic competition fell by $32.6 billion. However, annual savings from brands that have lost patent protection has been lower since then.22

Changes in drug mix will continue to play an important role in spending going forward. Many drugs now in the development pipeline are biologics,23 which often have a high introductory price and initially may not have many lower-cost alternatives. 23 Although the FDA has approved nearly 30FDA has begun to approve biosimilar substitutes for biologics that have lost patent and marketing protection, so far these biosimilars are not significantly lower-priced than the original biologics.24

Changes in Drug Prices

Prescriptionthere has been a lag in bringing many of these biosimilars to the market.24 In addition, biosimilars so far have not reduced prices for biologic products as significantly as lower-priced generics have done for traditional, chemical drugs.

Changes in Drug Prices

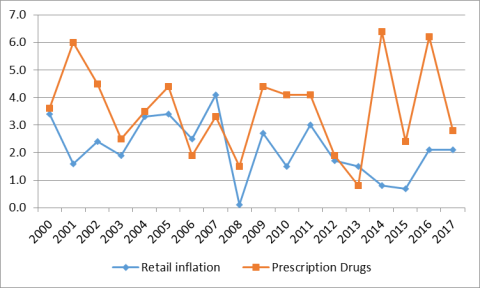

Although there have been annual fluctuations, prescription drug prices have risen faster than prices for overall U.S. goods and services since 2014in most years from 2000 to 2020, according to the U.S. Department of Labor's Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures retail inflation.25 The gap between prescription drug and overall inflation narrowed significantly in 2017. (See Figure 3.)

25 (See Figure

cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2020.

20 Murray Aitken et al., “Has the Era of Slow Growth for Prescription Drug Spending Ended?” Health Affairs, vol. 35, no. 9 (September 2016), p. 1601. The study looked at retail and institutional drug spending. Health Care Cost Institute, 2014 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report, October 2015, p. ii, at https://www.healthcostinstitute.org/research/annual-reports. The report, based on claims data from three major commercial insurers, found that per capita brand-name drug spending in employer-sponsored plans rose by $45 from 2013 to 2014. About two-thirds of the increase, $29.60, was for newly introduced drugs for hepatitis C.

21 Most often driven by brands in the three-to-five-year period since their launch. 22 IQVIA Institute, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” p. 7, August 2020. Available for download at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-us.

23 CRS Report RL34045, FDA Regulation of Follow-On Biologics, and CRS Report R42890, The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Pharmaceutical Innovation. Federal law has provided 12 years of marketing exclusivity for certain biologic drugs, which limits manufacturers’ initial market competition and increases their pricing power. Lawmakers also have attempted to spur development of lower-cost biosimilar products, similar to earlier efforts to stimulate development of generic products. Congress and the President enacted the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA) as Title VII of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended). The ACA/BPCIA gives the FDA authority to license products shown to be biosimilar to or interchangeable with an FDA-licensed biological product.

24 FDA, “Biosimilar Product Information,” https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information. 25 Retail inflation is a measure of the average change over time in prices for a set list of consumer goods and services. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is based on a market basket of goods and services. For prescription drugs, Department of Labor analysts survey a sample of drug stores and a list of the last 20 drugs dispensed. See BLS, “Measuring Price

Congressional Research Service

8

link to page 13 link to page 11

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

3.) U.S. retail drug inflation, as measured by the CPI-U,26 has fluctuated from annual increases of greater than 6% to a 2020 price decline.

Figure 3. U.S. Retail Prescription Drug Price Inflation

(Annual

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index, All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Notes: Non-seasonally adjusted data are for 12 months ending in December. The data do not include drugs dispensed through Medicaid or workers |

U.S. retail drug inflation, as measured by the CPI-U,26 was 6.4% in 2014, compared to general consumer inflation of 0.8%. Drug prices rose 6.2% in 2016, compared to a 2.1% consumer inflation rate, and 2.8% in 2017, compared to consumer inflation of 2.1%.

Drug inflation has been driven mainly by price increases for existing brand-name drugs and adoption of expensive new innovator brand-name drugs.2727 (See "“Changes in Drug Mix.”) Within the brand-name drug category, biologics and specialty drugs have driven much of the price inflation.28

Change in the CPI: Medical care,” https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm#A3.

26 The CPI-U is the CPI value for urban consumers. It excludes rural populations and represents approximately 80% of the population.

27 Murray Aitken et al., “Has the Era of Slow Growth for Prescription Drug Spending Ended?” Health Affairs, vol. 35, no. 9 (September 2016), pp. 1595-1603. The study looked at retail and institutional drug spending.

28 Ibid. There is wide variation in estimates of specialty drug spending depending on how the specialty drug category is defined. For example, see HHS, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Observations on Trends in Prescription Drug Spending,” March 8, 2016, at https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/observations-trends-prescription-drug-spending.

Congressional Research Service

9

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Changes in Drug Mix," above.)

Manufacturers also have raised prices for a number of existing generic drugs in the past several years. However, a 2016 HHS study found that generic price increases were not a major contributor to inflation.28 Likewise, pharmacy benefits manager (PBM) Express Scripts, in an analysis of prescription drug claims data, has found that the average price for commonly used brand-name drugs rose 10.7% from 2015 to 2016, and average prices for generic drugs declined by 8.7% over the same time period.29 Within the brand-name drug category, biologics and specialty drugs have driven much of the price inflation.30

Drug Price Transparency Drug Price Transparency It can be difficult to determine the final price of a prescription drug due to a lack of transparency in the marketplace. Drug companies price discriminate, meaning they sell the same drug to different buyers (wholesalers, health plans, pharmacies, hospitals, government purchasers, and other providers) at different prices. The final price of a drug may include rebates and discounts to health plans and pharmacy benefit managers that are not publicly disclosed. Market participants, such as wholesalers, add their own markups and fees. Complicating the picture even more, pharmaceutical manufacturers offer direct consumer discounts, such as prescription drug coupons that can be redeemed when filling a prescription at a pharmacy. Drug companies also offer charitable aid through patient assistance programs for individuals who cannot afford their prescriptions. Eligibility is often based on

income. The most commonly published drug prices do not include these discounts and rebates, which appear to be growing in size and importance according to government and private analyses. Source: CRS Report R44264, Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs); IQVIA Institute, “Medicines Use and Spending in the U.S. A Review of 2018 and Outlook to 2023,” May 2019, Exhibit 14, p. 20, HHS OIG, “Increases in Reimbursement for Brand-Name Drugs in Part D,” June 2018, https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-15-00080.asp.

Drug Utilization

Total prescription drug use has been rising in recent years. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the percentage of people in the United States using at least one prescription drug in the previous 30 days rose to 48.4% from 2013 to 2016, compared with 39.1% from 1988 to 1994.29 Total U.S. prescriptions, adjusted for length, rose to 6.4 billion in 2019 from 6.02 billion in 2017.30

The ACA expansion of prescription drug coverage has helped to boost demand for prescription drugs. Beginning in 2014, the ACA provided tax credits for the purchase of ACA exchange-based health plans and required many private insurance plans to cover prescription drugs as part of a package of essential health benefits.31 Studies of health insurance plans sold through ACA exchanges showed a nearly 15% annual increase in drug spending for those insured consumers from 2014 to 2015, driven mainly by higher utilization.32 Medicaid coverage was also expanded under the ACA, providing more drug coverage for non-elderly, low-income individuals.33 In

29 CDC, “Health United States, 2018,” Table 38, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/drug-use-therapeutic.htm. 30 IQVIA Institute, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” Exhibit 29, p. 32, August 2020. Available for download at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-us. According to IQVIA, prescription counts are adjusted for length of prescriptions and are reaggregated. Prescriptions referred to as 90-day are calculated based on transactions with 84 days supply or more to include medicines with up to one week fewer treatment days. Prescriptions for 84 days supply or more are factored by three, and those under 84 days are unchanged. The figure includes both retail and long-term care prescriptions.

31 The essential health benefits are 10 categories of services required by private plans offered in the nongroup and small-group markets. The requirement to offer the essential health benefits does not apply to large-group plans, self-insured plans, or grandfathered plans. CRS Report R44163, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s Essential Health Benefits (EHB).

32 Express Scripts, “Exchange Pulse,” June 2016, https://docplayer.net/126670164-Exchange-pulse-public-health-exchanges-report-june-2016.html.

33 The ACA raised the income threshold used to qualify individuals for the Medicaid program, thereby expanding coverage to more people. The ACA originally made the state Medicaid expansion mandatory, but the Supreme Court found that the enforcement mechanism for the expansion was unconstitutional, basically rendering it voluntary. Although prescription drug coverage is an optional Medicaid benefit, all states include drug coverage. See CRS In Focus IF10399, Overview of the ACA Medicaid Expansion.

Congressional Research Service

10

link to page 16 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

An analysis of the most recent National Health Expenditures prescription drug forecast for 2017-2026 included a special section on rebates. According to the analysis, increased rebates "contributed to lower net prices for many prescription drugs in recent years and are expected to have dampened prescription drug spending growth in 2017. In 2018 and beyond, the share of total prescription drug spending affected by rebates is not expected to increase as rapidly as in the recent past. As a result, the outlook for such spending reflects somewhat stronger growth in drug prices." Source: CRS Report R44264, Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs); IQVIA Institute, "Medicines Use and Spending in the U.S. A Review of 2016 and Outlook to 2021," Chart 1, May 2017; and "National Health Expenditure Projections, 2017–26: Despite Uncertainty, Fundamentals Primarily Drive Spending Growth," Health Affairs, vol. 37, no. 3 (March 2018). |

Drug Utilization

During the past several years, the ACA expansion of prescription drug coverage has helped to boost demand for prescription drugs. Beginning in 2014, the ACA provided tax credits for the purchase of ACA exchange-based health plans and required many private insurance plans to cover prescription drugs as part of a package of essential health benefits.31 Studies of health insurance plans sold through ACA exchanges show a nearly 15% annual increase in drug spending for those insured consumers from 2014 to 2015, driven mainly by higher utilization.32 Medicaid coverage also expanded under the ACA, including drug coverage for non-elderly, low-income individuals.33 In 2014, the ACA changes to Medicaid contributed to an 8% jump in Medicaid prescription drug claims and a 20% rise in gross Medicaid prescription drug spending.34

34

The aging of the baby boomers also has contributed to increased demand. According to IQVIA, patients aged 50 and older accounted for 70% of dispensed prescriptions in 2016 and 77% of the increase in drug dispensing since 2011.35

, as Americans over age 65 have significantly higher rates of prescription drug use than their younger counterparts.35

During the past several years, utilization has been affected by government and health payer efforts to reduce abuse of prescription opioids. For example, opioid use in the Medicare Part D program has been declining due to tighter program controls, although it still remains at high levels. According to the HHS Office of the Inspector General (OIG), Part D covered nearly 67 million opioid prescriptions in 2019—an average of 5.3 prescriptions per beneficiary receiving opioids. By comparison, Part D covered 71 million opioid prescriptions in 2018, 76 million in 2017, and 79 million in 2016.36

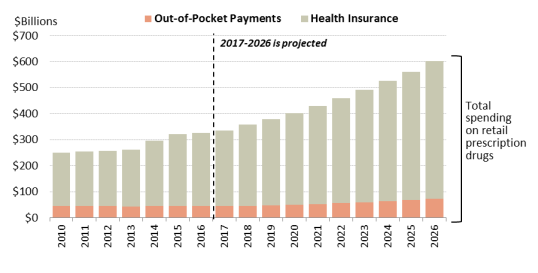

Are U.S. Consumer Out-of-Pocket Drug Costs Rising? Are U.S. Consumer Out-of-Pocket Drug Costs Rising?

As recently as 1990, consumer out-of-pocket spending—cash payments, health plan deductibles, coinsurance, and co-payments—for filled prescriptions made up 57% of U.S. retail drug spending, whereas commercial payers and taxpayer-financed health programs accounted for about 43%, according to NHE data. However, in the ensuing years, commercial payers and taxpayer-financed health programs have covered a growing share of the nation'’s retail prescription drug bill. The(See Figure 4.) According to the latest NHE data forecast that, out-of-pocket spending declined to 13.2% of about 14% of retail drug spending in 20172019, versus 86.2about 86% for these other payers.36 In 202637 By 2028, out-of-pocket spending is forecast to account for 12.1% of retail drug costs. (See Figure 4.)

Although consumer cost sharing represents a smaller share of overall prescription drug spending than in the past, consumers can still face high out-of-pocket expenses depending on the specific drugs they are prescribed (generic versus brand -name), whether they have insurance, the policies of their health plans, and their eligibility for manufacturer drug discount coupons or charitable assistance programs.

During the past several years

In general, health plans have been imposing higher levels of cost sharing for more expensive or less preferred prescription drugs in an effort to control spending and costs. From 2012 to 2015, the share of commercial health plans with a prescription drug deductible rose to 46% from 23%, according to an IQVIA analysis.37 Drug deductibles are especially prevalent in health plans sold on ACA state exchanges.38 There has been a continued increase in the use of formulary tiered pricing and in the practice of imposing coinsurance, as opposed to flat co-payments, for more expensive or less preferred drugs. In tiered pricing, a consumer may pay a $10 co-payment for a generic drug on a formulary low-cost price tier; the same consumer may be charged 30% coinsurance for an expensive specialty drug on a high-priced tier. The differential between health plan price tiers has been widening, imposing a greater financial burden on consumers who use higher-priced drugs.39 For example, in 201738

In 2020, enrollees in employer-sponsored health plans with three or more drug tiers had an average co-payment of $110116 for a high-priced tier-four drug, compared towith an $11 co-payment for a tier-one generic drug.

The cost-sharing increases appear toCoinsurance for covered workers in plans with three or more tiers averaged 18% for first-tier drugs, 25% second-tier preferred drugs, 37% third-tier nonpreferred drugs, and 28% for fourth-tier drugs.39 Nearly all covered workers at large firms had coverage for

38 Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey, Section 9, at https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2020-section-9-prescription-drug-benefits/. The Kaiser data indicate that the differential has increased, but 2018 is not directly comparable to some previous years due to a change in methodology.

39 Ibid., Kaiser. According to Kaiser, preferred drugs are drugs included on a formulary or preferred drug list; for example, a brand-name drug without a generic substitute. Nonpreferred drugs are drugs not included on a formulary or preferred drug list; for example, a brand-name drug with a generic substitute. Fourth tier drugs refer to new types of cost-sharing arrangements that typically build additional layers of higher co-payments or coinsurance for specifically

Congressional Research Service

12

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

specialty drugs, including 45% of workers who are in a plan with at least one cost-sharing tier just for specialty drugs. Insurers often base enrollee coinsurance on a list price for a drug, rather than the insurer’s net price after accounting for manufacturer rebates and other price discounts. Some health plans have begun to base enrollee co-insurance on net prices. 40 However, insurers may increase premiums or set higher deductibles to make up for lost revenue from such a change.

Increases in prescription drug cost-sharing for specific drugs have been partially moderated by other developments. The ACA capped total annual out-of-pocket spending in many commercial health plans, eliminated cost sharing for contraceptives, and reduced average cost sharing for Part D enrollees.4041 (There is no annual cap on out-of-pocket spending in Part D.) Pharmaceutical manufacturers have expanded patient assistance via discount coupons (which cover a portion of required health plan cost sharing) and patient assistance programs (which provide aid based on health condition and annual income).4142 Generic drug-use rates, for which cost sharing is low, have continued to increase.

According to some recent studies of insured consumers, average out-of-pocket spending for retail drugs has declined in the past several years. However, the number of consumers with high out-of-pocket costs—such as those with serious conditions or those prescribed specialty drugs—has increased.43

Caps on Annual Out-of-Pocket Spending

Many private health insurance plans place an annual cap, or maximum, on enrollee out-of-pocket spending for covered health care services, after which the payer covers the cost. For Source: Healthcare.gov, https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/out-of-pocket-maximum-limit/, and CRS Report R40611, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit. Notes: Only certain grandfathered private plans do not have to comply with the out-of-pocket cap. |

A

There are differing reports regarding trends in consumer out-of-pocket spending. For example, a 2016 study of enrollees in large employer-sponsored health plans found that average out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs declined to $144 in 2014 from a recent high of $167 in 2009.42 identified types of drugs, such as lifestyle drugs or biologics.

40 Unitedhealthcare, “Successful Prescription Drug Discount Program Expands to Benefit More Consumers at Point-of-sale,” March 12, 2019, https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/newsroom/2019/2019-03-12-prescription-drug-program-expands-to-benefit-consumers-point-of-sale.html.

41 Departments of Labor, HHS, and the Treasury, “FAQS about Affordable Care Act Implementation Part 36,” January 9, 2017, at https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/Downloads/ACA-FAQs-Part36_1-9-17-Final.pdf .

42 See IQVIA Institute, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” p. 18, available at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-us; and CRS Report R44264, Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs).

43 Ibid., IQVIA, p. 3. According to the IQVIA Institute, Part D enrollees paid $16.1 billion out of pocket in 2019, up 27% over the previous five years. The change included an 8.3 million (18.2%) increase in the over-65 population and a 13.7% increase due to greater use of medicines and shifts to drugs that may have higher out of-pocket costs. The higher spending was offset 5.2% by lower per-prescription costs. Patients covered by commercial insurance paid $36 billion out of pocket in 2019, down 5% from 2014, reflecting mix and volume changes, as well as greater use of coupons and vouchers provided by manufacturers. By law, coupons are not allowed to be used by patients using government programs.

Congressional Research Service

13

link to page 19 link to page 19 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

2009.44 But nearly 3% of enrollees had out-of-pocket costs of more than $1,000 in 2014, accounting for about one-third of drug spending and also one-third of all out-of-pocket spending. The share of people with high drug costs grew 2.5 times between 2004 and 2014. More recently in Medicare Part D, the unit cost of a specialty drug claim rose from $1,151 in 2007 to $4,455 in 2018. Beneficiaries can pay up to 33% coinsurance for Part D specialty drugs.45

A separate 2020 study by HHS on spending for outpatient prescription drugs found that from 2009 to 2018, median annual out-of-pocket spending per user in the United States declined to $54 from $93. The general finding held across different age groups and across different forms of insurance coverage, with some differences in degree.46

According to the NHE dataThe share of people with high drug costs has tripled since 2004.

A separate study of drug claims in commercial health plans found that median out-of-pocket spending for outpatient specialty drugs (those costing $600 or more per month) rose from $24 per month in 2003 to $35 per month in 2014, a 46% increase. During the same period, median out-of-pocket spending for nonspecialty drugs declined 57%, from $14 to $6 per month.43

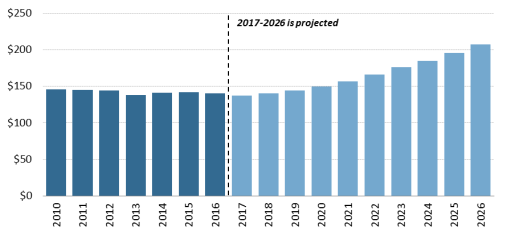

According to the NHE, per person out-of-pocket spending for retail prescription drugs declinedfluctuated from $146 in 2010 to $140 in 2016. It is forecast to dip to $137 in 2017 and then145 in 2012 to $148 in 2016, before declining to $144 in 2018. Out of pocket spending is forecast to gradually increase to $207 by 2026.44 (See190 by 202847 (see Figure 5.)). Because out-of-pocket spending is expected to rise more slowly than overall U.S. retail drug spending in the next decade, out-of-pocket spending is forecast to continue to decline as a share of retail drug expenditures.

expenditures (see Figure 5).

44 Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, “Examining High Prescription Drug Spending for People with Employer Sponsored Health Insurance,” October 27, 2016, at http://www.healthsystemtracker.org/insight/examining-high-prescription-drug-spending-for-people-with-employer-sponsored-health-insurance/. The 2009 figure of $167 is about $185 in 2014 dollars.

45 MedPAC, Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2019, p. 414, http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar19_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Part D specialty drugs are defined as those with a negotiated price of $670 or more per month. If a Part D enrollee has sufficient out-of-pocket spending to reach the catastrophic portion of the benefit, cost-sharing is reduced to a maximum of 5% coinsurance.

46 William Carroll, G. Edward Miller, and Steven Hill, “Out-of-Pocket Spending for Retail Prescribed Drugs by Age and Type of Prescription Drug Coverage, 2009 to 2018,” HHS Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), December, 2020, https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st532/stat532.pdf. Study based on data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Household Component, 2009–2018. Annual figures were inflated to 2018 dollars using the all-item Consumer Price Index.

47 CMS, “National Health Expenditure Projections 2019-2028,” Table 11, at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.html.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 20

Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Figure 5. Per Capita Out-of-Pocket Spending for Retail Prescription Drugs

(projected increases in out-of-pocket spending) |

|

|

Source: CMS, National Health Expenditure forecast data. |

Source: CMS, National Health Expenditure, Projected Data. Government Role in Prescription Drug Spending

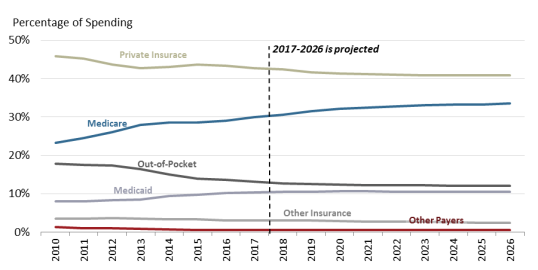

How Much U.S. Drug Spending Is Paid by Government Programs?

Congress and presidential administrations have expanded subsidized drug coverage to tens of millions of consumers during the past decade by implementing Medicare Part D (Medicare Modernization Act, 2003) and expanding eligibility for Medicaid as part of the ACA.4548 As a result, the government share of U.S. retail prescription drug spending (federal, state and local) rose from about 25% in 2005—the year before Part D took full effect—to an estimated 44.141% in 20172019. The government share of drug spending is forecast to rise to 4753% by 2028.49 % by 2026.46 (See Figure 6.)

How Does the Federal Government Pay For Prescription Drugs?

Unlike many other industrialized nations,47 the United States does not operate a single, centralized system for administering government-sponsored drug benefits, procuring pharmaceuticals, or setting drug prices.50 Instead, the various departments and agencies that oversee federal health programs operate a range of congressionally mandated drug discount and contracting systems, including market-based negotiations in Medicare Part D, direct procurement in the Veterans Health Administration, and a combination of mandatory rebates and negotiations in Medicaid. Separately, FDA regulates the safety and effectiveness of prescription drugs.48 51 Congress has not given FDA authority to set drug prices or to consider prices as part of its drug approval process.

Federal agencies can secure substantial discounts for prescription drugs under this decentralized system. However, price discounts vary widely among federal programs. For example, according to a recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on the prices of 176 drugs (net of applicable rebates and discounts), the average price ranged from $118 in Medicaid to $343 in Medicare Part D. According to CBO, the lower net prices in Medicaid were due to higher manufacturer rebates for that program than for Medicare Part D. 52 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense had average prices between the average prices in 50 See “Is U.S. Prescription Drug Spending Higher Than in Other Nations?” 51 Beginning with the Food and Drugs Act of 1906, Congress has incrementally refined and expanded FDA’s responsibilities regarding drug approval and regulation. CRS Report R41983, How FDA Approves Drugs and Regulates Their Safety and Effectiveness. See, in particular, Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) §§505 (new drugs), 501 (adulteration), and 502 (misbranding).

52 Congressional Budget Office, “A Comparison of Brand-Name Drug Prices Among Selected Federal Programs,” February 18, 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56978.

Congressional Research Service

16

link to page 22 link to page 21 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 21 Frequently Asked Questions About Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy

Medicaid and Medicare Part D. CBO also found a wide range of prices for specialty drugs. The CBO report builds on previous studies, including a 2015 HHS OIG report, which found that to a 2015 HHS Office of Inspector General report, Medicaid rebates were equal to 47% of Medicaid spending in 2012, while rebates made up a smaller 15% of Part D spending that same year.4953 Medicaid rebates for some drugs were more than 10 times larger than Part D rebates for the same products. Members of Congress have introduced legislation to give the HHS Secretary more power to negotiate Medicare Part D drug prices. (See "“Can the HHS Secretary Negotiate Medicare Part D Drug Prices?," below.)

Following is a table that ”)

Table 2 outlines prescription purchasing systems for four federal health care programs: Medicare Part D, Medicare Part B, Medicaid, and the Veterans Health Administration health system.50 (See Table 2.) 54 These programs were chosen because they are among the largest federal health programs. The table is not a complete list of federal prescription drug coverage.

Table 2. Selected Federal Programs Providing Prescription Drug Coverage

(overview of drug purchasing and payment methods by government programs)

|

Medicare

Medicare Part D is a voluntary drug benefit offered through private health care plans that

Part D

contract with HHS. The Part D program relies on market competition to limit spending. Plan sponsors, which compete for enrollees, negotiate rebates, discounts, and other price concessions with manufacturers. The ACA amended Part D to require additional price discounts from manufacturers. |

| , according to available data.a

Medicare

Medicare Part B covers physician services and durable medical equipment, as well injectable or

Part B

intravenous drugs administered as part of a service in a doctor |

|

Medicaid |

Medicaid is a federal-state entitlement program that pays for health care services on behalf of certain low-income |

|

Veterans Health Administration |

340B program.d

Veterans

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

Health

operates the nation |

Source: CRS Analysis of federal agency information, including contracts, and federal statutes.

Notes: ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148, as amended); CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; HHS = Department of Health and Human Services.

a. CMS, "“Coverage Gap Discount Program,"” at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Advantage/Plan-

Payment/CGDP.html. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, P.L. 115-123, increased the manufacturer discount.

b.

b. See CRS Report R40425, Medicare Primer.

c. See CRS Report R43778, Medicaid Prescription Drug Pricing and Policy.

d. Ibid. Under the 340B program, manufacturers agree to provide outpatient drugs to covered entities,

including qualifying hospitals, at significantly reduced prices.

e.

e. See CRS Report R42747, Health Care for Veterans: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions.

Can the HHS Secretary Negotiate Medicare Part D Drug Prices?

Congress designed Medicare Part D as a market-oriented program in which commercial health payers compete for enrollees based on the price and scope of their drug coverage.5155 Part D plan sponsors, which include health plans, unions, employers, and PBMspharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), negotiate drug rebates and discounts with manufacturers and contract with retail pharmacies to dispense drugs to Part D enrollees at set reimbursement rates.52

56

To bolster market competition, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA; P.L. 108-173), which created Medicare Part D, contains a "“noninterference provision."53”57 This provision prohibits the HHS Secretary (Secretary) from intervening in negotiations between Part D plan sponsors, drug manufacturers, and pharmacies or from requiring a specific Part D formulary.54

58

In the years since Part D was enacted, Congress has debated whether the market-based model has been effective in controlling drug prices and enrollee costs. Proponents of the current approach point out that program spending to date has been well below initial budget projections.55 Total Part D drug rebates have risen from 9.6% of annual Part D drug spending in 2007, the second year the program was in effect, and is forecast to be 24% in 2018.56 Further, a 2014 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study found that Part D premiums were lower in areas of the country where there was the most robust competition among Part D plans.57

However, CBO also has found that Part D plans have higher average drug prices than the Medicaid program, which imposes mandatory federal drug rebates.58 Separate studies by the HHS Office of Inspector General and the Government Accountability Office likewise have found that Medicaid secures lower drug prices than Part D.59

Some lawmakers have proposed modifyingPart D plan sponsors have been successful in increasing drug rebates. Part D direct and indirect remuneration (which consists mainly of prescription drug rebates but also includes other remuneration that affects net drug prices, such as certain pharmacy fees) rose from 11.1% of total Part D drug costs in 2008 to an estimated 28.4% in 2020.59 However, HHS, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission

55 Part D plans must provide coverage that is at least equivalent to a set standard benefit, which is set and updated annually by HHS. Part D plans also may offer more generous coverage.