Section 232 Steel and Aluminum Tariffs: Potential Economic Implications

Changes from March 19, 2018 to April 12, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

EffectiveOn March 23, President Trump will applythe United States began applying 25% and 10% tariffs, respectively, on certain steel and aluminum imports, from all countries, excluding Canada and Mexico at least at this time. These tariffs will affect various stakeholders. U.S. imports of steel and aluminum from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, South Korea, and the European Union are to be exempt from the tariffs until May 1. The Administration has stated it is open to discussing terms for permanent exemptions from the tariffs for these and other U.S. trading partners, based on addressing the perceived threat to national security. To date, one trading partner has concluded negotiations on such terms; U.S. steel imports from South Korea are to be subject to a quota equivalent to 70% of 2015-2017 imports in lieu of the tariffs. South Korea has not negotiated an exemption for its aluminum exports.

These tariffs are expected to affect various stakeholders in the U.S. economy, prompting reactions from several Members of Congress, some in support and others voicing concerns. In general, the tariffs would beare expected to benefit the domestic steel and aluminum industries, leading to potential higher steel and aluminum prices and expansion in production in those sectors, while potentially negatively affecting consumers and downstream domestic industries (e.g., manufacturing and construction) through higher costs.

For more information on the Section 232 case, see CRS Insight IN10872, The President Acts to Impose Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum Imports, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10097, UPDATE: Threats to National Security Foiled? A Wrap Up of New Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum, by [author name scrubbed].

U.S. Steel and Aluminum Imports Subject to Section 232

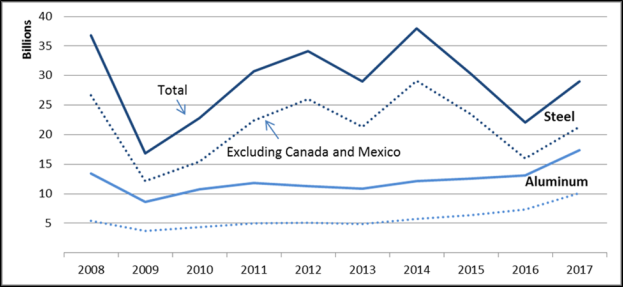

In 2017, U.S. imports of steel and aluminum products covered by the Section 232 tariffs totaled $29.0 billion and $17.4 billion, respectively (FigureFigure 1). Over the past decade, steel imports, by value, have fluctuated significantly, while imports of aluminum have increased steadily. The current exclusion of Canada and Mexico from the Section 232 tariffs is economically significant as the two potential for permanent exclusions from the tariffs for the seven trading partners listed above is economically significant as these countries respectively accounted for 67% and 55% of relevant U.S. steel and aluminum imports in 2017 (Table 1). Among countries currently facing the additional import tariff for 18% and 5% of relevant U.S. steel imports, and 40% and 2% of relevant U.S. aluminum imports in 2017. Excluding Canada and Mexico, the top three suppliers of steel in 2017 were the European Union (EU), South Korea, and BrazilJapan, Russia, and Taiwan; the top three suppliers of aluminum were China, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates (Table 1).

|

Steel |

Aluminum |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Country |

Import Value (million U.S. $s) |

Import Share |

Country |

Import Value (million U.S. $s) |

Import Share |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Currently Exempted Currently Exempted |

|

|

China

|

Canada

European Union |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

South Korea |

|

|

Russia |

|

Mexico

2,494 |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Brazil |

|

|

United Arab Emirates |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Australia

Argentina

Brazil

Australia

South Korea

Total Exempted

Total Exempted

Not Currently Exempted Not Currently Exempted |

|

|

European Union |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Russia |

|

|

Bahrain |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Taiwan |

|

|

Argentina |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Turkey |

|

|

India |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

China |

|

|

India

India

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

India |

|

|

Qatar |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Vietnam |

|

|

Japan |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Canada

|

Indonesia

United Arab Emirates |

|

|

Canada |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

Mexico |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Total (All Countries) |

|

|

U.S. Total (All Countries) |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Created by CRS using data from the Census Bureau on HTS products included in the Section 232 proclamations.

Notes: European Union includes 28 member states. Canada and Mexico are currently excluded from the new tariffs(*) Total non-exempted includes all U.S. trading partners except the 7 trading partners currently exempted.

Economic Dynamics of the Tariff Increase

Changes in tariffs affect economic activity directly by influencing the price of imported goods and indirectly through changes in exchange rates and real incomes. The extent of the price change and its impact on trade flows, employment, and production in the United States and abroad depend on resource constraints and how various economic actors (foreign producers of the goods subject to the tariffs, producers of domestic substitutes, producers in downstream industries, and consumers) may respond as the effects of the increased tariffs reverberate throughout the economy. The following outcomes would beare expected at the microeconomic (individual firms and consumers) level:

- The price of the imported steel and aluminum products

would likelyexceptionsexclusions, and the ability of foreign producers to lower their own prices and absorb a portion of the tariff increase, which determines the extent the tariffs are "passed through" to downstream industries and consumers. - Demand for the imported goods facing the tariffs

would likelyis likely to decrease, while demand for those goods produced domestically or in countries excluded from the tariffwould likelyis likely to increase. Consumers and downstream firms' sensitivity to the price increase (their price elasticity of demand) will depend in large part on the degree to which the steel and aluminum products produced domestically, or imported from exemptedor in excludedcountries, are sufficient substitutes for the products facing the tariffs. - The price and output of steel and aluminum produced domestically or

inimported from countriesexcludedexempted from the tariffswilllikelyare likely to increase. As consumers of the products facing the tariffs shift their demand totariff-freelower- or zero-tariff substitutes, domestic and excluded-country producerswillare likely to respond by increasing output and raising prices. Resource constraints that may limit this expansion could cause prices to increase more rapidly. - Input costs for downstream domestic producers

willlikelyare likely to increase. As prices likely rise in the United States for the goods subject to the tariffs, domestic industries that use steel and aluminum in their products ("downstream" industries, such as auto manufacturers and oil producers) will face higher input costs. Higher input costs for downstream domestic producerswillare likely to lead to some combination of lower profits and higher prices for consumers, which in turn, could dampen demand for downstream products and result in a reduction of output in these sectors.

Aggregating these microeconomic effects, tariffs also have the potential to affect macroeconomic variables, although these impacts may be limited in the case of the Section 232 tariffs, given their focus on two specific commodities with potential exemptions, relative to the size of the U.S. economy. With regard to the value of the U.S. dollar, as demand for foreign goods likelypotentially falls in response to the tariff, U.S. demand for foreign currency may also fall, putting upward pressure on the relative exchange value of the dollar. Tariffs may also affect national consumption patterns, depending on the how the shift to higher cost domestic substitutes affects consumers' discretionary income and therefore aggregate demand. Finally, given the ad- hoc nature, these tariffs, in particular, are also likely to increase uncertainty in the U.S. business environment potentially placing a drag on investment.

Assessing the Overall Economic Impact

From a global standpoint, tariff increases on steel and aluminum are likely to result in an unambiguous welfare loss due to what most economists consider is a misallocation of resources caused by shifting production from lower-cost to higher-cost producers. Looking solely at the domestic economy, the net welfare effect is unclear, but also likely negative. Generally, economic models would suggest the negative impact of higher prices on consumers and industries using the imported goods is likely to outweigh the benefit of higher profits and expanded production in the import-competing industry and the additional government revenue generated by the tariff. It is theoretically plausible to generate an overall positive welfare effect for the domestic economy if the foreign producers absorb a large enough portion of the tariff increase. Given the current excess capacity and intense price competition in the global steel and aluminum industries, however, this level of tariff absorption by foreign firms seems unlikely. Moreover, any potential retaliation by foreign governments would erode this welfare gain. Major U.S. trading partners, such as the EU, have already expressed their intent to retaliate against the U.S. action by imposing tariffs on various U.S. exports.

The direct economic effects of the Section 232 tariffs may be limited due to the relatively small share of economic activity directly affected. Excluding Canada and Mexicothe currently exempted countries, U.S. imports of covered steel and aluminum were $21.49.7 billion and $10.17.8 billion, respectively, accounting for 1.3less than 1% of all U.S. imports in 2017. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, steel and aluminum producers employ approximately 200,000 workers in the United States, less than 1% of total U.S. private employment (120 million). Various stakeholder groups have prepared quantitative estimates of the costs and benefits across the economy. Specific estimates from these studies should be interpreted with caution given their sensitivity to modeling assumptions and techniques, but generally they suggest a small negative overall effect on U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) from the tariffs with employment shifts into the domestic steel and aluminum industries and away from other sectors in the economy.

Ultimately the economic significance of the tariffs will largely depend on two currently unknown variables, namely

- variables which remain in flux, namely: The range of product and country exclusions.

Canada and Mexico are excluded, which togetherThe seven trading partners currently exempted from the tariffs account for more than25% of steel and 40% of aluminum imports covered by the tariff. The United States also has important national security relationships, a key factor for potential exemptions according to the U.S. proclamations, with the EU and South Korea. Exempting these partners, together with Canada and Mexico, would exclude more than 50% of relevant U.S. steel imports. Specific products may also be excluded from the tariffs, which would50% of the relevant U.S. steel and aluminum imports. If these trading partners or additional trading partners are granted permanent exemptions, depending on the terms of these exemptions, the effects of the tariffs would likely be significantly reduced. The Administration has also announced a process to consider product-specific exclusions from the tariffs, which could further limit any economic impact. - The degree to which other countries retaliate. Retaliation

wouldwill have an immediate negative economic impact on the industries subject to retaliatory tariffs. Depending on the degree of retaliation it could also set off a tit-for-tat process of increasing global protectionism, leading to a reduction in global trade volumes and a costly and inefficient reallocation of resources.