Debt Limit Policy Questions: What Are Extraordinary Measures?

Changes from February 21, 2018 to February 27, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Following a period of suspension, the statutory debt limit was reinstated on December 9, 2017, at a level that precisely accommodated the federal borrowing undertaken to that date. On December 11 and 12, 2017, Secretary Mnuchin announced that the Treasury would implement "extraordinary measures" that delay when the debt limit will bind. Additionally, the Bureau of the Fiscal Service suspended sales of certain Treasury securities to extend the Treasury's ability to meet statutory spending requirements without defaulting on its debt obligations. These measures were used until passage of the Bipartisan INSIGHTi

“Extraordinary Measures” and the Debt Limit

Updated February 27, 2019

Following a period of suspension, the statutory debt limit is scheduled to be reinstated on March 1, 2019,

at a level that precisely accommodates the federal borrowing undertaken to date. When federal borrowing

approaches the debt limit, the Treasury Secretary has the authority to implement “extraordinary measures”

that delay when the debt limit will bind. Extraordinary measures were last implemented from March 2017

through September 2017 and from December 2017 through February 2018, until passage of the Bipartisan

Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123) on; February 9, 2018, which) suspended the statutory debt limit until

March 1, 2019. This Insight briefly examines the debt limit and the use of extraordinary measures.

use of extraordinary measures and its subsequent effects on federal debt activity. What Is the Debt Limit?

As part of its "“power of the purse,"” Congress uses the statutory debt limit (codified in 31 U.S.C. §3101)

as a means of restricting federal debt. Debt subject to the limit is more than 99% of total federal debt, and

includes debt held by the public (which is used to finance budget deficits) and debt issued to federal

government accounts (which is used to meet federal obligations). The debt limit acts as a congressional

check on recent revenue and expenditure trends, though decisions affecting debt levels may have been

agreed to by Congress and the Administration well in advance of debt limit deliberations. Some past debt

limit legislation has linked debt limit increases with other fiscal policy proposals.

What Are Extraordinary Measures?

Extraordinary measures represent a series of actions that postpone when Congress must act on debt limit

legislation. The authority for using extraordinary measures rests with the Treasury Secretary (codified in 5

5 U.S.C. §8348 and 5 U.S.C. §8909). Invoking extraordinary measures has delayed required action on the

debt limit by periods ranging from a few weeks to several months, depending on when such measures

were enacted (see the "“How Long Do Extraordinary Measures Last?"” section). Accounts and members of

the public that are affected by extraordinary measures must be compensated for the delay in payment that

resulted from such actions when the debt limit is subsequently modified.

On December 12, 2017, the Treasury announced the

Before or during a period when extraordinary measures that are currently available. The Fiscal Service suspended issuance of State and Local Government Securities on December 8. A Debt Issuance Suspension Period was invoked on December 11, suspending new investments and redeeming certain existing investments of the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund and the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund. On December 12, the Treasury suspended daily reinvestment of securities held in the G Fund. BBA 2018 (P.L. 115-123) suspended the debt limit until March 1, 2019, and eliminated the need for implementation of extraordinary measures. Table 1 provides a description of the extraordinary measures used when those measures were implemented in 2017 and 2018.

Table 1. are implemented, Treasury typically provides a

description of the extraordinary measures available and estimates of their effect on federal borrowing

capacity (or how much “headroom” they will add). The most recent description of such measures was

provided by Treasury in December 2017. Table 1 provides a description of the extraordinary measures

Congressional Research Service

https://crsreports.congress.gov

IN10837

CRS INSIGHT

Prepared for Members and

Committees of Congress

Congressional Research Service

2

used when those measures were implemented from March 2017 through September 2017 and from

December 2017 through February 2018.

Table 1. Use of Extraordinary Measures, 2017-2018

Headroom Added from March

2017-September 2017

Headroom Added from

December 2017-February 2018

Suspension of reinvestment in

Government Securities Investment

Fund (G Fund) of the Federal

Use of Extraordinary Measures, 2017-2018

|

Measure |

Headroom Added in 2017-2018 |

Headroom Added in March 2017 |

|

Suspension of reinvestment in Government Securities Investment Fund (G Fund) of the Federal Retirement System |

$208 billion |

$225 billion |

Retirement System

$208 billion

$225 billion

Suspension of invested balance in |

$22 billion |

$23 billion |

|

Declaration of a Debt Issuance Suspension Period |

Suspension Period

$12.7 billion one-time and $7.3 billion | $87 billion one-time and $7.3 billion |

Suspension of State and Local |

$0 (prevents further increases in debt |

$0 |

$0

Measure

Source: U.S. Department of Treasury, "“Description of the Extraordinary Measures,"” December 12, 2017, available at

https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/Documents/Description-of-Extraordinary-Measures-2017_12_12_Final.pdf; ";

“Description of Extraordinary Measures,"” March 16, 2017, available at https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/Documents/

Description_of_Extraordinary_Measures_2017_03_16.pdf.

Notes: .

Notes: In a January 2018 report, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that an additional $3.5 billion of headroom is

available through the Federal Financing Bank. This table only includes available measures reported by the Treasury.

How Long Do Extraordinary Measures Last?

Short-term fluctuations in federal debt levels provide for substantial uncertainty in how long

extraordinary measures can last. Federal balances fluctuate on a day-to-day basis in response to a number

of factors, including the timing of payments for Social Security, military benefits, and other programs;

interest payments on debt obligations; and the timing of certain receipts. Prior to enactment of BBA 2018, CBO

CBO and the Treasury projected that extraordinary measures would be exhausted in March 2018.

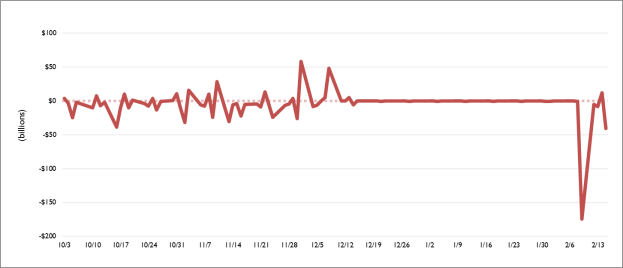

Figure 1 shows federal daily balances to date in FY2018around the period when extraordinary measures were last

implemented (December 2017 through February 2018). The reduced variation in daily balances starting in

December 2017 reflects the implementation of extraordinary measures. The sharp increase in borrowing on February 9 to exactly match outlays and

receipts. The decline in the daily balance on February 9, 2018, reflects the compensation of

intragovernmental creditors whose payments were delayed by the implementation of extraordinary

measures.

Congressional Research Service

3

Figure 1. Changes in themeasures.

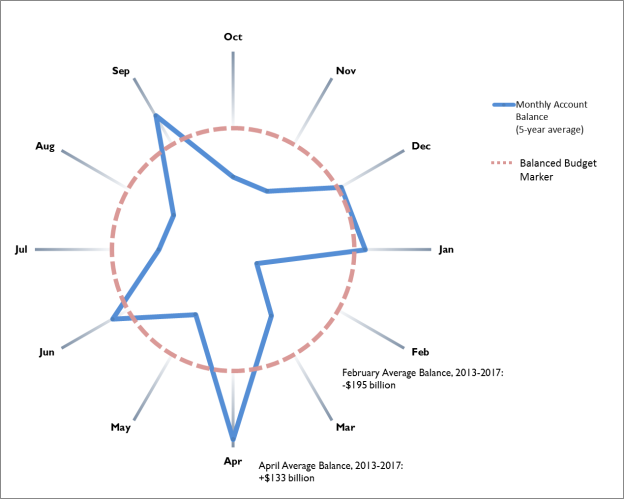

Monthly budget outcomes can also fluctuate with the timing of various activities. The federal government

tends to record higher net budget surpluses in April (when many individual tax returns are filed) and

September (as certain payments are due at the end of the fiscal year) while recording lower balances in

other months. Figure 2 presents the average federal monthly account balances from the previous five fiscal years. Data points outside the circle indicate months that have recorded average surpluses from FY2013 through FY2017; points inside the circle represent months that have recorded average deficits in those years.