Federal Financing for the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

Changes from January 17, 2018 to May 23, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Federal Financing for the State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

Contents

- Introduction

- Federal Matching Rate

- Federal CHIP Funding

- Federal Appropriation

- State Allotments

- Shortfall Funding

- Child Enrollment Contingency Fund

- Redistribution Funds

- Medicaid Funds

- Federal CHIP Funds Finance Some Medicaid Expenditures

- Qualifying State Option

- Stairstep Children

- Outreach and Enrollment Grants

- Future of CHIP Funding

- Extending Federal CHIP Funding

- If Federal CHIP Funding Expires

Figures

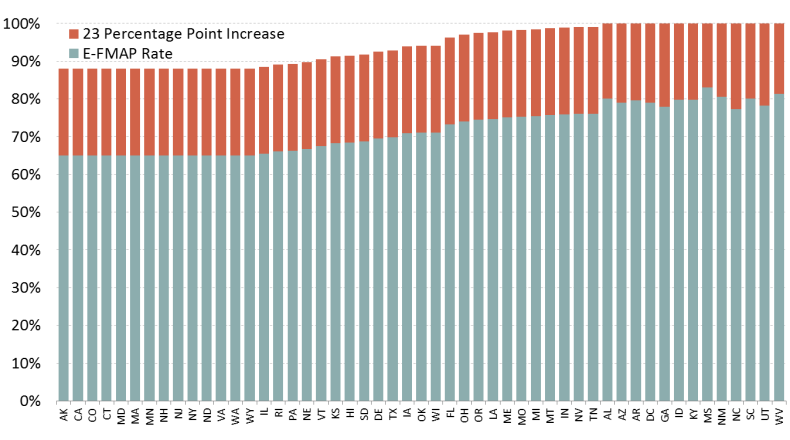

- Figure 1. State Distribution of E-FMAP Rate with the 23 Percentage Point Increase

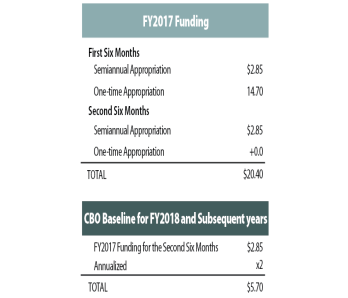

- Figure 2. CHIP Federal Expenditures and Federal Appropriations

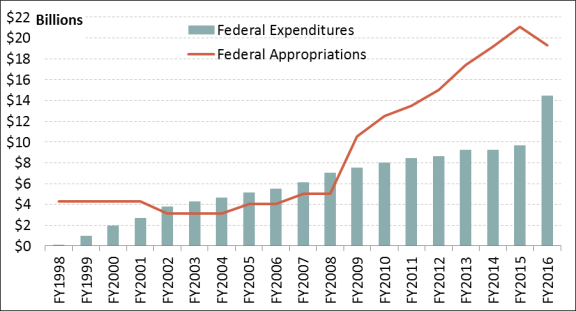

- Figure 3. CHIP Allotments and Federal Expenditures

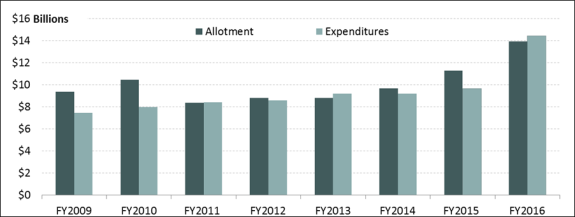

- Figure 4.

Federal CHIP Funding for FY2017 and CBO's Baseline for FY2018 and Subsequent YearsTimeline of Legislative Activity

Summary

The State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) is a means-tested program that provides health coverage to targeted low-income children and pregnant women in families that have annual income above Medicaid eligibility levels but have no health insurance. CHIP is jointly financed by the federal government and the states, and the states are responsible for administering CHIP.

The federal government's share of CHIP expenditures (including both services and administration) is determined by the enhanced federal medical assistance percentage (E-FMAP) rate. StatutorilyThe E-FMAP varies by state; statutorily, the E-FMAP can range from 65% to 85%. The E-FMAP is increased by 23 percentage points for FY2016 through FY2019 and by 11.5 percentage points for FY2020. In FY2021, the E-FMAP is to return to the regular E-FMAP rates. , the E-FMAP can range from 65% to 85%. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) included a provision to increase the E-FMAP rate by 23 percentage points for most CHIP expenditures from FY2016 through FY2019. With this increase, the E-FMAP ranges from 88% to 100%.

The federal appropriation for CHIP is provided in statute. From this federal appropriation, states receive CHIP allotments, which are the federal funds allocated to each state and the territories for the federal share of their CHIP expenditures. In addition, if a state has a shortfall in federal CHIP funding, there are a few sources of shortfall funding, such as the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, redistribution funds, and Medicaid funds.

In statute, FY2017 was the last year a full-year federal CHIP appropriation was provided, so a law would need to be enacted if federal funding of CHIP were to be continued. Even though federal CHIP funding has expired, states have federal CHIP spending in FY2018 because states have access to unspent funds from their FY2017 allotments and to unspent allotments from FY2016 and prior years redistributed to shortfall states. In addition, the continuing resolutions enacted on December 8, 2017, and December 22, 2017, both include provisions that provide short-term funding for CHIP. The continuing resolution enacted on December 8, 2017, included a special rule for redistribution funds to prioritize the allocation of funds to states estimated to exhaust federal CHIP funds before January 1, 2018. The continuing resolution enacted on December 22, 2017, includes short-term appropriations and an extension of the special rule for redistribution funds through March 2018.

Under current law, the ACA maintenance of effort (MOE) requirement for children is in place through FY2019. The MOE provision requires states to maintain income eligibility levels for CHIP children through September 30, 2019, as a condition for receiving federal Medicaid payments (notwithstanding the lack of corresponding full-year federal CHIP appropriations for FY2018 and FY2019). If additional federal CHIP funding is not provided, the MOE requirement would affect CHIP Medicaid expansion programs and separate CHIP programs differently. States with CHIP Medicaid expansion programs must continue to cover their CHIP children once federal funding is no longer available. However, states with separate CHIP programs would not be required to continue coverage after enrolling eligible children in Medicaid or certified qualified health plans.

Congress's action or inaction will determine the future of CHIP and of health coverage for CHIP children. In considering the future of CHIP, Congress has a number of policy options, including extending federal CHIP funding and continuing the program, or letting CHIP funding expire.

This report provides an overview of CHIP financing, beginning with an explanation of the federal matching rate. It describes various aspects of federal CHIP funding, such as the federal appropriation, state allotments, the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, redistribution funds, and outreach and enrollment grants. The report ends with a section about the future of CHIP funding, including the options for extending CHIP funding and what could happen if federal funding expiresrecent legislative activity that has resulted in federal funding for CHIP being provided through FY2027.

Introduction

The State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIPCHIP) is a federal-state program that provides health coverage to certain uninsured, low-income children and pregnant women in families that have annual income above Medicaid eligibility levels but do not have health insurance.1 CHIP is jointly financed by the federal government and the states and is administered by the states. Participation in CHIP is voluntary, and all states, the District of Columbia, and the territories participate.21 The federal government sets basic requirements for CHIP, but states have the flexibility to design their own version of CHIP within the federal government's basic framework. As a result, there is significant variation across CHIP programs.

States may design their CHIP programs in one of three ways: a CHIP Medicaid expansion, a separate CHIP program, or a combination approach in which the state operates a CHIP Medicaid expansion and one or more separate CHIP programs concurrently. CHIP benefit coverage and cost-sharing rules depend on program design. CHIP Medicaid expansions must follow the federal Medicaid rules for benefits and cost sharing. For separate CHIP programs, the benefits are permitted to look more like private health insurance, and states may impose cost sharing, such as premiums or enrollment fees, with a maximum allowable amount that is tied to annual family income.

FY2017 was the last year states received a full-year appropriation for CHIP, and FY2018 began on October 1, 2017, without CHIP funding having been extended. In FY2018, states have been funding the federal share of their CHIP programs with unspent funds from their FY2017 allotments and unspent allotments from FY2016 and prior years redistributed to shortfall states. In addition, continuing resolutions enacted on December 8, 2017 (P.L. 115-90), and December 22, 2017 (P.L. 115-96), include provisions that provide short-term funding for CHIP.

On December 8, 2017, a law (P.L. 115-90) was enacted to extend continuing appropriations for federal agencies and programs, and this law includes language that amends the CHIP statute to add a special rule for redistribution funds available through CHIP for the first quarter of FY2018. The special rule prioritizes the allocation of redistribution funds to emergency shortfall states, which were states estimated to exhaust federal CHIP funding before January 1, 2018.

On December 22, 2017, a law (P.L. 115-96) was enacted to extend continuing appropriations for most federal agencies and programs (among other things) through January 19, 2018. Section 3201 of P.L. 115-96 (1) provides $2.85 billion in appropriations for CHIP for the period of October 1, 2017, through March 31, 2018, and (2) extends the special rule for redistribution funds that was added by P.L. 115-90 for every month through March 2018.

This short-term funding is not sufficient to fund CHIP through the end of FY2018. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the short-term funding should be enough to ensure no states exhaust their federal CHIP funding before January 19, 2018. However, CMS cannot say with any certainty whether the short-term funding is sufficient to fund the federal share of CHIP through March 31, 2018.3

There are a couple of bills (S. 1827 and H.R. 3922) that would extend federal funding for CHIP for five years. For more information about these bills, see "Extending Federal CHIP Funding."

This report provides an overview of CHIP financing, beginning with an explanation of the federal matching rate. It describes various aspects of federal CHIP funding, such as the federal appropriation, state allotments, the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, redistribution funds, and outreach and enrollment grants. The report ends with a section about the future of CHIP funding, including the options for extending CHIP funding and what could happen if additional federal funding is not provided.

Federal Matching Rate

The federal government's share of CHIP expenditures (including both services and administration) is determined by the enhanced federal medical assistance percentage (E-FMAP) rate. The E-FMAP rate is based on the FMAP rate, which is the federal matching rate for the Medicaid program. The FMAP formula compares each state's average per capita income with average U.S. per capita income. The formula provides higher reimbursement to states with lower incomes (with a statutory maximum of 83%) and lower reimbursement to states with higher incomes (with a statutory minimum of 50%).42

The E-FMAP rate is calculated by reducing the state share under the regular FMAP rate by 30%.53 Statutorily, the E-FMAP (or federal matching rate) can range from 65% to 85%.64 For some CHIP expenditures, the federal matching rate is different from the E-FMAP rate. For instance, the matching rate for translation and interpretation services is the higher of 75% or states' E-FMAP rate plus 5 percentage points. Also, the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA; P.L. 111-3) included a provision that reduced the matching rate to the regular FMAP rate for children with family incomes exceeding 300% of the federal poverty level (FPL) with an exception for certain states.7

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended)5

The ACA included a provision to increase the E-FMAP rate by 23 percentage points (not to exceed 100%) for most CHIP expenditures from FY2016 through FY2019. The 23 percentage point increasecontinuing resolution enacted on January 22, 2018 (P.L. 115-120), extended the increase to the E-FMAP rate by one year (i.e., through FY2020), but the increase for FY2020 is to be 11.5 percentage points rather than 23 percentage points.

The increase to the E-FMAP does not apply to certain expenditures, such as translation services, CHIP children above 300% of FPL (with an exception for certain states), expenditures for administration of citizenship documentation requirements, expenditures for administration of payment error rate measurement (PERM), and Medicaid coverage of certain breast or cervical cancer patients.

This provision increasedThe 23 percentage point increase changed the statutory range of the E-FMAP rate to between 88% and 100%. In FY2018, 13 states have E-FMAP rates of 100%. Figure 1 shows the state distribution of E-FMAP rates for FY2018, with the 23 percentage point increase. Because the federal share of CHIP is significantly higher with this increase, states are spending through the federal CHIP funding allocated to them (i.e., state CHIP allotments) faster with the increased E-FMAP rate.

Federal CHIP Funding

Federal CHIP funding is mandatory spending (i.e., funding controlled outside of the annual appropriations process through authorizing laws), and this funding is an entitlement to states that adhere to the federal CHIP rules. The funding for this program is provided through a mandatory appropriation set in statute. Figure 2 shows the federal appropriation amounts and federal expenditures for CHIP from FY1998 through FY2016.

|

Figure 2. CHIP Federal Expenditures and Federal Appropriations (FY1998 through FY2016) |

|

|

Sources: §2104 of the Social Security Act, §108 of the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA, P.L. 111-3) as amended by §10203(d)(2)(F) of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended), and §301(b)(3) of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA; P.L. 114-10); and Medicaid Financial Management Reports. Note: Federal CHIP expenditures increased significantly from FY2015 to FY2016 due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) provision that increased the E-FMAP rate (or federal matching rate) by 23 percentage points for most CHIP expenditures from FY2016 through FY2019. |

The federal appropriation amount is the maximum amount of federal funding for CHIP. Most of the federal CHIP expenditures are from state CHIP allotments, which are the federal funds allocated to each state to finance its CHIP program. In addition to allotments, states could receive shortfall funding, such as Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments, redistribution funds, or Medicaid funds. Some CHIP funding is used to finance some Medicaid expenses. In addition, states can receive outreach and enrollment grants.

Federal Appropriation

The federal appropriation for CHIP is provided in Section 2104(a) of the Social Security Act. This amount is the overall annual ceiling on federal CHIP spending to the states, the District of Columbia, and the territories. CHIPRA increased the annual appropriation amounts substantially beginning in FY2009 and provided funding through FY2013. The ACA provided funding for an additional two years (i.e., through FY2015), and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA; P.L. 114-10)MACRA added appropriations for FY2016 and FY2017 at $19.3 billion and $20.4 billion,86 respectively.97

FY2018 began on October 1, 2017, without federal CHIP funding having been appropriated for the fiscal year. The continuing resolution enacted on December 22, 2017 (P.L. 115-96), providesprovided $2.85 billion in appropriations for CHIP for the first six months of FY2018 (i.e., October 1, 2017, through March 31, 2018).

The full-year FY2018 appropriation for CHIP was not provided until January 22, 2018, when P.L. 115-120 provided CHIP appropriations for FY2018 through FY2023. The annual appropriation amounts for FY2018 through FY2023 increase annually from $21.5 billion in FY2018 to $25.9 billion in FY2023.8

Then, February 9, 2018, BBA 2018 provided appropriations for FY2024 through FY2027. The funding amounts for FY2024 through FY2026 are not specified; instead, such sums as necessary to fund allotments to states are provided. However, the funding for FY2027 is the combination of two semiannual appropriations of $7.65 billion plus a one-time appropriation of such sums as necessary to fund the allotments to states after taking into account the semiannual appropriations.

If the federal appropriations were not large enough to cover state allotments in any given year, the state allotments would be reduced proportionally. However, Figure 2 shows the federal appropriation has been more than sufficient to fund federal CHIP expenditures since FY2009.109 In fact, from FY2011 through FY2017FY2018, multiple appropriations laws have rescinded a total of $42.846.4 billion in funding from CHIP (see text box entitled "CHIP Changes in Mandatory Programs" for more detail about these rescissions).

|

CHIP Changes in Mandatory Programs Changes in mandatory programs (CHIMPs) are provisions in appropriations acts that reduce or constrain mandatory spending. From FY2011 through As shown in Table 1, most of these rescissions have come from the performance bonus payment fund. The Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA; P.L. 111-3) established performance bonus payments for states that increase their Medicaid (not CHIP) enrollment among low-income children above a defined baseline. States were eligible for performance bonus payments from FY2009 through FY2013. The fund balance for the performance bonus payments increased significantly every year because the transfers into the fund were substantially higher than the actual performance bonus payments to states. From FY2011 through Funds also have been rescinded from unobligated national allotments, which are federal appropriations funds not allocated for state allotments. In FY2015 through In FY2016, funds were rescinded from the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund in the amount of $1.7 billion. The Child Enrollment Contingency Fund is one potential CHIP shortfall funding source available to states (see the "Child Enrollment Contingency Fund" section). On Tuesday, May 8, 2018, the Trump Administration submitted to Congress a proposal for 38 rescissions of budget authority, totaling $15.4 billion. In their transmission, the Office of Management and Budget stated that these rescissions were transmitted pursuant to Section 1012 of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (2 U.S.C. 683). The proposal includes $7.0 billion in CHIP rescissions from two provisions. The first provision would rescind $5.1 billion from FY2017 federal CHIP funding, and the second provision would rescind $1.9 billion from the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund.10 The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) provided an assessment of the proposed CHIP rescissions, and CBO estimates the rescissions would not affect CHIP expenditures or the number of individuals with insurance coverage.11

Sources: Defense and Full-Year Appropriations, 2011 (P.L. 112-10); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2012 (P.L. 112-74); Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013 (P.L. 113-6); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 (P.L. 113-76); Continuing Appropriations Resolution, 2015 (P.L. 113-164); Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235); Continuing Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-53); Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113); Continuing Appropriations and Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, and Zika Response and Preparedness Act (P.L. 114-223); Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 114-254); Note: Totals may not add due to rounding. |

State Allotments

State allotments are the federal funds allocated to each state and territory for the federal share of its CHIP expenditures. CHIPRA established a new allocation of federal CHIP funds among the states based largely on states' actual use of and projected need for CHIP funds.1112 There are two formulas for determining state allotments: an even-year formula and an odd-year formula.1213

In even years, such as FY2016FY2018, state CHIP allotments are each state's allotment for the prior year plus any Child Enrollment Contingency Fund (described below) payments from the previous year adjusted for growth in per capita National Health Expenditures and child population in the state.

In odd years, state CHIP allotments are each state's spending for the prior year (including federal CHIP payments from the state CHIP allotment, payments from the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, and redistribution funds) adjusted using the same growth factor as the even-year formula (i.e., per capita National Health Expenditures growth and child population growth in the state).

Since the odd-year formula is based on states' actual use of CHIP funds, it is called the re-basing year because a state's CHIP allotment can either increase or decrease depending on that state's CHIP expenditures in the previous year. Figure 3 shows how the re-basing for FY2011 significantly decreased the aggregate amount for state allotments from FY2010 to FY2011, and in FY2015, CHIP allotments increased due to state spending in FY2014.

|

Figure 3. CHIP Allotments and Federal Expenditures (FY2009 through FY2016) |

|

|

Sources: Various Federal Register notices; Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), "Federal CHIP Allotments, FYs 2015-2017," MACStats Exhibit 33, posted online May 10, 2017; and the Medicaid Financial Management Reports. Note: Federal CHIP expenditures increased significantly from FY2015 to FY2016 due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) provision that increased the E-FMAP rate (or federal matching rate) by 23 percentage points for most CHIP expenditures from FY2016 through FY2019. The FY2016 allotments were calculated under a special rule that took into account the 23 percentage point increase in the E-FMAP that begins in that year. |

State CHIP allotment funds are available to states for two years, which explains why federal expenditures are higher than the state allotments in some years. The federal CHIP expenditures can include federal funding from states' allotments for the specified year and the prior year in addition to shortfall funding.

The allotment is available to states to cover the federal share of both CHIP benefit and administrative expenditures.1314 However, no more than 10% of the federal CHIP funds that a state draws down from its CHIP allotment can be spent on nonbenefit expenditures, including expenditures for administration, translation services, and outreach efforts.

MACRA added special rules to the state allotments for FY2016 and FY2018. The special rule for FY2016 established the states' allotments by taking into account the 23 percentage point increase in the E-FMAP that began in that year. Specifically, the FY2016 allotments were each state's FY2015 allotment (including Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments and redistribution funds), determined as if the 23 percentage point increase in the E-FMAP were in place for FY2015. Then, that amount was adjusted using the same growth factor as the even- and odd-year formulas (i.e., growth in per capita National Health Expenditures and child population in the state).

For FY2018, MACRA included a provision that reduced the amount of states' unspent funds from their FY2017 allotments available for expenditures in FY2018 by one-third. Although FY2017 is the last year for which full-year federal CHIP funding is provided under current law, states have federal CHIP spending in FY2018 because states have access to unspent funds from their FY2017 allotments and unspent allotments from FY2016 and prior years redistributed to shortfall states.

Shortfall Funding

If a state's CHIP allotment for the current year, in addition to any allotment funds carried over from the prior year, is insufficient to cover the state's projected CHIP expenditures for the current year, a few different shortfall funding sources are available. These sources include the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, redistribution funds, and Medicaid funds.

Child Enrollment Contingency Fund

CHIPRA established the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund and made its funds available to states for FY2009 through FY2013. The ACA extended the availability of the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund and of payments from the fund through FY2015, and MACRA extended the fund and payments through FY2017.14 Together, P.L. 115-120 and BBA 2018 extend the funding mechanism for the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund through FY2027.15

A state is eligible for Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments if it has both a funding shortfall1516 and CHIP enrollment (for children) that exceeds a target level.1617 As a result, not all states with funding shortfalls are eligible for Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments.

The Child Enrollment Contingency Fund was funded with an initial deposit equal to 20% of the appropriated amount for FY2009 (i.e., $2.1 billion). In addition, for FY2010 through FY2017FY2027, such sums as wereare necessary for making Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments to eligible states wereare to be deposited into the fund, but these transfers could notcannot exceed 20% of the federal appropriation for the fiscal year.

The Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payment formula is based on a state's growth in CHIP enrollment and per capita spending, which means a state may receive a payment from the fund that does not equal its actual shortfall. Iowa, Michigan, and Tennessee are the only states that have received Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments over the period of FY2009 through FY2016, (when the funds were first available) through FY2017.18.17

Redistribution Funds

After two years, any unused state CHIP allotment funds are redistributed to shortfall states.1819 For redistribution funds, a shortfall state is defined as a state that will not have enough money to meet projected costs in the current year after counting (1) the current year's state allotment, (2) unspent funds from the prior year's state allotment, and (3) available Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments. If redistributed funds are insufficient to meet the needs of all shortfall states, each shortfall state receives a proportionate share of the available funds based on the shortfall in each state. From FY2009 through FY2016FY2017, Michigan and fourall five territories (Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and Guam) havePuerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) received redistribution funds.19

The continuing resolutions enacted on December 8, 2017, and December 22, 201720

During the time when CHIP did not have a full-year appropriation at the beginning of FY2018, some special rules for redistribution funds were added to ensure that no state exhausted its federal CHIP funding. The continuing resolutions enacted on December 8, 2017 (P.L. 115-90), and December 22, 2017 (P.L. 115-96), both included special rules for redistribution funds. The special rule in the December 8, 2017, continuing resolution prioritizesprioritized the allocation of redistribution funds to emergency shortfall states, which were states estimated to exhaust federal CHIP funding before January 1, 2018. The special rule in the December 22, 2017, continuing resolution extendsextended the definition of emergency shortfall states through March 2018.

Medicaid Funds

States that design their CHIP program as a CHIP Medicaid expansion or a combination program and face a shortfall after receiving Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments and redistribution funds may receive federal Medicaid matching funds to fund the shortfall in the CHIP Medicaid expansion portion of their CHIP program. When Medicaid funds are used to fund CHIP, the state receives the lower regular FMAP rate (i.e., the federal Medicaid matching rate) rather than the higher E-FMAP rate provided for other CHIP expenditures. However, although federal CHIP funding is capped, federal Medicaid funding is open-ended, which means there is no upper limit or cap on the amount of federal Medicaid funds a state may receive.

Federal CHIP Funds Finance Some Medicaid Expenditures

In some situations, such as the qualifying state option and the stairstep children, federal CHIP funding is used to finance Medicaid expenditures.

Qualifying State Option

Certain states had significantly expanded Medicaid eligibility for children prior to the enactment of CHIP in 1997, and these states are allowed to use their CHIP allotment funds to fund the difference between the Medicaid and CHIP matching rates (i.e., FMAP and E-FMAP rates, respectively) to finance the cost for children in Medicaid above 133% of FPL. This provision is referred to as the qualifying state option. FY2015 was the last year for which the qualifying state option was authorized until MACRA extended the qualifying state option through FY2017.

Together, P.L. 115-120 and BBA 2018 extend the qualifying state option through FY2027.The following 11 states meet the definition of a qualifying state: Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin. Although 11 states are eligible for this option, only 6 states (Connecticut, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin) had CHIP expenditures under the qualifying state option in FY2016.2021

Stairstep Children

The ACA required states to transition CHIP children aged 6 through 18 in families with annual income less than 133% of FPL to Medicaid, beginning January 1, 2014.2122 Coverage for such children continues to be financed with states' CHIP annual allotment funding at the E-FMAP rate as long as their income eligibility is greater than the state's March 31, 1997, Medicaid income standard for children.2223 However, the E-FMAP rate is not available for children between the ages of 6 and 18 who have access to private health insurance.

Outreach and Enrollment Grants

CHIPRA established outreach and enrollment grants aimed at reducing the number of children eligible for but not enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP and improving retention so that eligible children stay covered for as long as they are eligible for the programs. CHIPRA provided $100 million to fund the outreach and enrollment grants for FY2009 through FY2013. The ACA extended the outreach and enrollment grants through FY2015 and provided an additional $40 million in funding. MACRA extended the outreach and enrollment grants through FY2017 and authorized another $40 million in funding.

Ten percent of the allocation was to be directed to a national enrollment campaign, and 10% was to be targeted to outreach for American Indian and Alaska Native children. The remaining 80% was to be distributed among state and local governments and to community-based organizations for purposes of conducting outreach campaigns, with a particular focus on rural areas and underserved populations. Grant funds also were targeted at proposals that address cultural and linguistic barriers to enrollment.

Future of CHIP Funding

In considering the future of CHIP, it is helpful to recall why the program was created in 1997: to provide affordable health coverage at a time when there were few other insurance coverage options for low-income children outside of Medicaid. The health insurance market is far different today, with the enactment of the ACA. Now, if CHIP funding is exhausted, current CHIP-eligible children could be eligible for Medicaid or potentially for subsidized coverage in the health insurance exchanges. However, not all CHIP-eligible children would be eligible for these programs, and some could end up being uninsured if CHIP is no longer available.

Congress's action or inaction will determine the future of CHIP and of health coverage for CHIP children. In considering the future of CHIP, Congress has a number of policy options, including extending federal CHIP funding and continuing the program, or letting CHIP funding expire.

Extending Federal CHIP Funding

If Congress decides to extend federal CHIP funding, there are a number of policy options regarding how long to extend funding and whether to make programmatic changes. Funding could be extended for just a few years (e.g., two or four years) or indefinitely, and the extension could maintain, phase down, or eliminate the 23 percentage point increase to the E-FMAP rate (i.e., the federal matching rate for CHIP). (See the textbox "Federal Cost of Extending CHIP Funding" for more information about extending CHIP funding.)

Federal Cost of Extending CHIP Funding The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is required to assume that mandatory spending programs in existence on or before the enactment of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-33), which would include CHIP, that lack future appropriations and have current-year outlays of at least $50 million will continue operating as they had been immediately prior to their expiration. This requirement is in the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, Section 257(b)(2).

Because the baseline projections assume $5.7 billion in federal CHIP spending for FY2018 and subsequent years within the budget window, CBO's estimated cost of extending federal CHIP funding is lower than it would have been without this assumption. In addition, the federal costs of extending CHIP funding would be offset by reductions in federal spending for Medicaid and subsidized exchange coverage because some CHIP children would receive Medicaid coverage or subsidized exchange coverage if CHIP were to expire. |

There are a couple of bills that would extend federal funding for CHIP for five years. On October 4, 2017, both the Senate Finance Committee and the House Energy and Commerce Committee had markups on different bills that would extend CHIP federal funding through FY2022, among other things.23

The Senate Finance Committee reported the Keeping Kids' Insurance Dependable and Secure Act of 2017 (KIDS Act; S. 1827), which would extend federal CHIP funding through FY2022 and extend the increased E-FMAP rates for one year (i.e., through FY2020) but with an 11.5 percentage point increase instead of a 23 percentage point increase under current law. The bill also includes extensions of other CHIP provisions (e.g., the Express Lane eligibility option and the maintenance of effort [MOE] requirement for children in families with incomes below 300% of FPL) and other programs and demonstrations (e.g., the Child Obesity Demonstration Project and the Pediatric Quality Measures Program).

According to the CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) cost estimate released on October 20, 2017, the KIDS Act is estimated to increase federal spending by $14.9 billion and revenues by $6.7 billion for a net cost of $8.2 billion over the period of FY2018 through FY2027.24 On January 5, 2018, CBO and JCT updated the cost estimate for the KIDS Act to account for the repeal of penalties for the individual health insurance mandate that was included in P.L. 115-97, enacted on December 22, 2017. According to the cost estimate released on January 5, 2018, the KIDS Act is estimated to increase federal spending by $7.3 billion and revenues by $6.6 billion for a net cost of $0.8 billion over the period of FY2018 through FY2027.25

The House Energy and Commerce Committee reported the Helping Ensure Access for Little Ones, Toddlers, and Hopeful Youth by Keeping Insurance Delivery Stable Act of 2017 (HEALTHY KIDS Act; H.R. 3921),26 which includes almost identical language to the KIDS Act that would extend CHIP federal funding through FY2022 and extend the increased E-FMAP for one year at 11.5 percentage points. The HEALTHY KIDS Act also includes almost identical language that would extend the same CHIP provisions and other programs and demonstrations as the KIDS Act. In addition, the HEALTHY KIDS Act includes some provisions that are not in the KIDS Act, such as adding a new CHIP state option for qualified CHIP look-alike plans, modifying the Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) allotment reductions, and providing additional Medicaid funding to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The HEALTHY KIDS Act includes the following provisions as offsets: modifications to Medicaid third-party liability, treatment of lottery winnings for Medicaid eligibility, and Medicare Part B and D premium subsidies for higher-income individuals.

The HEALTHY KIDS Act, under Division B of the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act, includes some changes to the provisions from the HEALTHY KIDS Act as reported by the House Energy and Commerce Committee. The CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act amended the provision extending the outreach and enrollment program, the Medicaid DSH provision, and the Medicaid third-party liability provision. In addition, the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act, released on October 30, 2017, deleted the Medicare Parts B and D premium subsidies for higher-income individuals provision, but this provision was added back into the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act through an amendment adopted by the House Rules Committee on November 1, 2017.27 According to the CBO and JCT cost estimate for the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act language posted on the House Rules Committee website on October 30, 2017,28 the HEALTHY KIDS Act under Division B is estimated to increase federal spending by $11.4 billion and revenues by $6.7 billion for a net cost of $4.7 billion over the period of FY2018 through FY2027.29 The House passed the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act on November 3, 2017, by a vote of 242 to 174.

If Federal CHIP Funding Expires

If additional federal CHIP funding is not provided, the loss of funding and the ACA MOE requirements would affect states' CHIP programs differently depending on whether the program is a CHIP Medicaid expansion or a separate CHIP program.

The CHIP enrollees in CHIP Medicaid expansion programs (almost 60% of CHIP enrollees)30 likely would continue to receive coverage through their state's Medicaid program due to the ACA MOE requirement, which requires states to maintain income eligibility levels for CHIP children through September 30, 2019, as a condition for receiving any Medicaid funding (notwithstanding the lack of corresponding full-year federal CHIP appropriations for FY2018 and FY2019).31 This switch would cause the federal share of expenditures to decrease from the E-FMAP rate to the regular FMAP rate, which means the cost of covering these children would increase for states.

For the CHIP enrollees in separate CHIP programs (roughly 40% of CHIP enrollees),32 if CHIP funding expires, states would have to enroll eligible children in Medicaid or certified qualified health plans in the health insurance exchanges. A certified qualified health plan is a qualified health plan that has been certified by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to be "at least comparable" to CHIP in terms of benefits and cost sharing. The HHS Secretary was required by statute to review the benefits and cost sharing for children under qualified health plans in the exchanges and certify those plans that offer benefits and cost sharing that are at least comparable to CHIP coverage.33 In the review released November 25, 2015, the HHS Secretary was not able to certify any qualified health plans as comparable to CHIP coverage because out-of-pocket costs were higher under the qualified health plans and the CHIP benefits were generally more comprehensive for child-specific services (e.g., dental, vision, and habilitation services).34 States with separate CHIP programs would not be required to continue coverage after enrolling eligible children in Medicaid or certified qualified health plans.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information about the State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), see CRS Report R43627, State Children's Health Insurance Program: An Overview, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||

| 2. |

The five territories are American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. |

|||||

| 3. |

| |||||

| 4. |

For more information about the FMAP rate, see CRS Report R43847, Medicaid's Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||

Figure 4. Timeline of Legislative Activity (October 1, 2017, through February 9, 2018)

|

Sources: The continuing resolution enacted on December 8, 2017 (P.L. 115-90), the continuing resolution enacted on December 22, 2017 (P.L. 115-96), the continuing resolution enacted on February 9, 2018 (P.L. 115-120), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123). Notes: BBA 2018 = Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123); CHIP = State Children's Health Insurance Program; E-FMAP = enhanced federal medical assistance percentage. At the beginning of FY2018, states funded the federal share of their CHIP programs with unspent funds from their FY2017 allotments; when states exhausted that funding, redistribution funds were available (i.e., unspent allotments from FY2016 and prior years redistributed to shortfall states). Since the redistribution funds were insufficient to fully fund all states for FY2018, each state received a proportionate share of the available funds based on the shortfall in that state. In December 2017, some states were expected to exhaust funding from these sources, and short-term funding for CHIP was provided through the continuing resolutions enacted on December 8, 2017 (P.L. 115-90), and December 22, 2017 (P.L. 115-96). On December 8, 2017, a law (P.L. 115-90) was enacted to extend continuing appropriations for federal agencies and programs, and this law included language amending the CHIP statute to add a special rule for redistribution funds available through CHIP for the first quarter of FY2018. The special rule prioritized the allocation of redistribution funds to emergency shortfall states, which were states estimated to exhaust federal CHIP funding before January 1, 2018. On December 22, 2017, a law (P.L. 115-96) was enacted to extend continuing appropriations for most federal agencies and programs (among other things) through January 19, 2018. Section 3201 of P.L. 115-96 (1) provided $2.85 billion in appropriations for CHIP for the period of October 1, 2017, through March 31, 2018, and (2) extended the special rule for redistribution funds that was added by P.L. 115-90 for every month through March 2018. The short-term funding provided in P.L. 115-96 was available through March 31, 2018. The full-year CHIP appropriation for FY2018 was included in the continuing resolution enacted on January 22, 2018 (P.L. 115-120). This law also provides CHIP appropriations for FY2019 through FY2023, and it extends the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, the qualifying states option, and the outreach and enrollment grants for FY2018 through FY2023. In addition, P.L. 115-120 extends the increase to the E-FMAP rate by one year (i.e., through FY2020), but the increase is to be 11.5 percentage points rather than 23 percentage points (i.e., the increase for FY2016 through FY2019). BBA 2018 further extends CHIP funding for FY2024 through FY2027, and it also extends the Child Enrollment Contingency Fund, the qualifying states option, and the outreach and enrollment grants for FY2024 through FY2027. Author Contact Information [author name scrubbed], Specialist in Health Care Financing

([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Footnotes1.

|

|

The five territories are American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. 2.

|

|

For more information about the FMAP rate, see CRS Report R43847, Medicaid's Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), by [author name scrubbed]. |

For example, assume a state has a federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) rate of 60%, which means the state share is 40%. To determine the enhanced federal medical assistance percentage (E-FMAP) rate for this state, first determine 30% of the state share (i.e., 40%), which is 12%, then subtract 12 percentage points from the state share under Medicaid to get the state share under CHIP, which is 28%. To get the E-FMAP rate, take 100% minus the state share under CHIP to get an E-FMAP rate of 72%. |

|

§2105(b) of the Social Security Act (SSA). |

||||||

|

States that already had a federal approval plan or that had enacted a state law to submit a plan for federal approval on the date of enactment for the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA; P.L. 111-3). Two states (New Jersey and New York) plus one county in California fall into these exceptions and receive the E-FMAP rate for CHIP enrollees above 300% of the federal poverty level (FPL). No other state provides CHIP coverage to children over 300% of FPL. |

||||||

|

The FY2017 appropriation was the combination of two |

||||||

|

For more information about the changes enacted under MACRA, see CRS Report R43962, The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA; P.L. 114-10), coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

|

|

9.

The FY2023 appropriation is a combination of semiannual appropriations of $2.85 billion from SSA §2104(a) and a one-time appropriation of $20.2 billion from P.L. 115-120, which is provided for the first six months of the fiscal year and remains available until expended. |

From FY2002 through FY2008, the national appropriation amounts were insufficient to cover the full cost of some states' CHIP programs. For FY2002 through FY2005, the amount of redistribution funds from other states was enough to make up the difference. For FY2006 through FY2008, however, additional CHIP appropriations were provided to cover the cost of the federal share of CHIP expenditures. |

||||

|

|

For more information about the rescission package, see CRS Insight IN10899, Proposed CHIP Rescissions in the Trump Administration's Rescission Request, by [author name scrubbed]. 11.

|

|

Letter from Keith Hall, Director of the Congressional Budget Office, to Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, Re: Proposed Rescissions for the Children's Health Insurance Program, May 8, 2018, at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53830. |

Prior to CHIPRA, the territories received 0.25% of the national appropriation amount and the remainder was divided, or allotted, among the states based on a formula using survey estimates of the number of low-income children in each state and the number of those children who were uninsured. |

||

|

SSA §2104(m) |

||||||

|

CHIP Medicaid expansion states may use federal Medicaid funds to pay for CHIP administrative expenditures. |

||||||

|

SSA §2104(n) |

||||||

|

For Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments, a state has a funding shortfall if a state's current-year CHIP allotment plus any unused CHIP allotment funds from the previous year are insufficient to cover the federal share of the state's CHIP program. The definition of shortfall funding for Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments does not factor in redistribution funds. |

||||||

|

The target enrollment level for Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments is the target enrollment level for the previous year increased by the child population growth factor used to calculate the allotment growth factor. |

||||||

|

MACPAC, MAC Basics: Federal CHIP Financing, September 2011; Communication with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in May 2014; Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book, December 2015; Communication with Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in May 2017 and April 2018. |

||||||

|

SSA §2104(f) |

||||||

|

Communication with CMS in May 2014, June 2016, August 2016, |

||||||

|

Medicaid Financial Management Reports. |

||||||

|

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services granted approval for Pennsylvania to delay the transition of CHIP children aged 6 to 18 in families with income less than 133% of FPL until CY2015. |

||||||

|

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, "Medicaid Program; Eligibility Changes Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010," 77 Federal Register 17144, March 23, 2012; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicaid and CHIP FAQs: Funding for New Adult Group, Coverage of Former Foster Care Children and CHIP Financing, December 2013. |

||||||

| 23. |

See CRS Report R44989, Comparison of the Bills to Extend State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Funding, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] for a comparison of the provisions in the KIDS Act and Division B of the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act as baselined against current law. |

|||||

| 24. |

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), Cost Estimate: S. 1827 Keep Kids' Insurance Dependable and Secure Act of 2017, October 20, 2017, at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/s1827.pdf. |

|||||

| 25. |

CBO and JCT, Updated Cost Estimate for S. 1827, the Keep Kids' Insurance Dependable and Secure Act of 2017, January 5, 2018, at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/s1827_0.pdf. |

|||||

| 26. |

The Helping Ensure Access for Little Ones, Toddlers, and Hopeful Youth by Keeping Insurance Delivery Stable Act of 2017 (HEALTHY KIDS Act, H.R. 3921) was introduced on October 3, 2017. At the House Energy and Commerce Committee markup October 4, 2017, the following amendments that were adopted with a voice vote are available at "PR-MEDCD-RSA_02" (at http://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF14/20171004/106486/BILLS-115-3921-B001257-Amdt-123.pdf) and "LUJAN_068" (at http://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF14/20171004/106486/BILLS-115-3921-L000570-Amdt-114.pdf). The committee report is H.Rept. 115-358. |

|||||

| 27. |

The amendment adopted by the House Rules Committee on November 1, 2017 is at https://rules.house.gov/bill/115/hr-3922. |

|||||

| 28. |

The cost estimate for the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act does not include Medicare Part B and D premium subsidies for higher-income individuals. However, this provision was included in the cost estimate of the HEALTHY KIDS Act as reported by the House Energy and Commerce Committee (https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr3921rev.pdf). |

|||||

| 29. |

The full cost estimate for the CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act shows the bill (including both Divisions A and B) is estimated to increase federal spending by $19.4 billion and increase revenue by $4.7 billion for a net cost of $14.7 billion. (CBO and JCT, Estimate of the Direct Spending and Revenue Effects of H.R. 3922 The CHAMPIONING HEALTHY KIDS Act, an Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute [Version H.R. 3922 FLR-AINS_06.XML], as Posted on the Website of the House Committee on Rules October 30, 2017, October 31, 2017, at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr3922amendment.pdf). |

|||||

| 30. |

MACPAC, MACStats, Exhibit 31. Child Enrollment in CHIP and Medicaid by state, FY2016, as posted on MACPAC's website as of July 10, 2017. |

|||||

| 31. |

For more information about the ACA MOE requirement, see CRS Report R43909, CHIP and the ACA Maintenance of Effort (MOE) Requirement: In Brief, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||

| 32. |

MACPAC, MACStats, Exhibit 31. Child Enrollment in CHIP and Medicaid by state, FY2016, as posted on MACPAC's website as of July 10, 2017. |

|||||

| 33. |

§2105(d)(3)(C) of the Social Security Act. |

|||||

| 34. |

The Department of Health and Human Services reviewed the second-lowest-cost silver plan in the largest rating area in each state to compare it to CHIP in that state. (CMS, Certification of Comparability of Pediatric Coverage Offered by Qualified Health Plans, November 25, 2015.) |