The Debt Limit Since 2011

Changes from September 13, 2017 to January 10, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The Debt Limit Since 2011

Contents

- Federal Debt Policy and the Debt Limit

- Recent Developments

- Extraordinary Measures and Debt Issuance Suspension Periods

- Recent Increases in the Debt Limit

- The 2011 Debt Limit Episode

- The 2011 Debt Ceiling Episode Begins

- Proposed Solutions in the Spring of 2011

- The Budget Control Act of 2011

- Debt Limit Increases Under the BCA

- The Debt Limit in 2013

- Debt Limit Reached at End of December 2012

- Suspension of the Debt Limit Until May 19, 2013

- Replenishing the U.S. Treasury's Extraordinary Measures

- Debt Limit Reset and Return of Extraordinary Measures in May 2013

- Debt Limit Forecasts in 2013

- Debt Limit Issues in 2013

- Resolution of the Debt Limit Issue in October 2013

- Other Proposals Regarding the Debt Limit in October 2013

- The Debt Limit in 2014

- Debt Limit Forecasts in Late 2013 and 2014

- Treasury Secretary Lew Notifies Congress in Early 2014

- Debt Limit Suspension Lapses in February 2014

- Debt Limit Again Suspended Until March 2015

- The Debt Limit in 2015

- Treasury's Extraordinary Measures in 2015

- Cash Management Changes

What is theU.S. Treasury's Headroom Under the Debt Limit?- How Long Would Extraordinary Measures Last in 2015?

- Why Did the Estimated Date of Treasury's Exhaustion of Borrowing Capacity Move Up?

- Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 and the Resolution of the 2015 Debt Limit Episode

- Other Developments in 2015 and 2016

- Developments in 2017 and 2018

- Administration Officials Urge Congress to Act

- Debt Limit Again Suspended in September 2017

Figures

Summary

The Constitution grants Congress the power to borrow money on the credit of the United States—one part of its power of the purse—and thus mandates that Congress exercise control over federal debt. Control of debt policy has at times provided Congress with a means of raising concerns regarding fiscal policies. Debates over federal fiscal policy have been especially animated in recent years. The accumulation of federal debt accelerated in the wake of the 2007-2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession. Rising debt levels, along with continued differences in views of fiscal policy, led to a series of contentious debt limit episodes in recent years.

The 2011 debt limit episode was resolved on August 2, 2011, when President Obama signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; S. 365; P.L. 112-25). The BCA included provisions aimed at deficit reduction and allowing the debt limit to rise in three stages, the latter two subject to congressional disapproval. Once the BCA was enacted, a presidential certification triggered a $400 billion increase. A second certification led to a $500 billion increase on September 22, 2011, and a third, $1,200 billion increase took place on January 28, 2012.

Federal debt again reached its limit on December 31, 2012. Extraordinary measures were again used to allow payment of government obligations until February 4, 2013, when H.R. 325, which suspended the debt limit until May 19, 2013, was signed into law (P.L. 113-3). On that date, extraordinary measures were reset, which would have lasted until October 17, 2013, according to Treasury estimates issued in late September 2013. On October 16, 2013, enactment of a continuing resolution (H.R. 2775; P.L. 113-46) resolved a funding lapse and suspended the debt limit through February 7, 2014. On February 15, 2014, a measure to suspend the debt limit (S. 540; P.L. 113-83) through March 15, 2015, was enacted. Once that debt limit suspension lapsed after March 15, 2015, the limit was reset at $18.1 trillion. On November 2, 2015, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA2015; H.R. 1314; P.L. 114-74) was enacted, which suspended the debt limit through March 15, 2017, and relaxed some discretionary spending limits.

On March 16, 2017, the debt limit was reset at $19,809 billion and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin notified Congress that he had invoked authorities to use extraordinary measures. On June 28, 2017, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin notified Congress that extraordinary measures would be used until September 29, 2017, and urged action before that date. On September 3, 2017, Secretary Mnuchin argued that a debt limit measure should be tied to legislation responding to Hurricane Harvey.

On September 6, 2017, an agreement on the debt limit and a continuing resolution was announced between President Trump and congressional leaders. The next day, the Senate approved an amended version of H.R. 601, which included a suspension of the debt limit through December 8, 2017. On September 8, 2017, the House agreed to the amended measure, which the President signed the same day (P.L. 115-56). Once the debt limit suspension lapses in December 2017, the Treasury Secretary may again invoke authorities to use extraordinary measures, which would likely suffice to meet federal obligations well intoTwo days later a measure (P.L. 115-56) was enacted to implement that agreement, which included a suspension of the debt limit through December 8, 2017. Once that suspension lapsed, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin invoked authorities to employ extraordinary measures, which are estimated to last until sometime in late March or early April 2018. Secretary Mnuchin reportedly asked some congressional leaders to act on the debt limit before the end of February 2018.

Total federal debt increases when the government sells debt to the public to finance budget deficits, which adds to debt held by the public, or when the federal government issues debt to certain government accounts, such as the Social Security, Medicare, and Transportation trust funds, in exchange for their reported surpluses—which adds to debt held by government accounts; or when new federal loans outpace loan repayments. The sum of debt held by the public and debt held by government accounts is the total federal debt. Surpluses reduce debt held by the public, while deficits raise it. This report will be updated as events warrant.

Federal Debt Policy and the Debt Limit

The Constitution grants Congress the power to borrow money on the credit of the United States—one part of its power of the purse—and thus mandates that Congress exercise control over federal debt. Control of debt policypolicy has at times provided Congress with a means of expressing views on appropriate fiscal policies.

Before 1917 Congress typically controlled individual issues of debt. In September 1917, while raising funds for the United States' entry into World War I, Congress also imposed an aggregate limit on federal debt in addition to individual issuance limits. Over time, Congress granted Treasury Secretaries more leeway in debt management. In 1939, Congress agreed to impose an aggregate limit that gave the U.S. Treasury authority to manage the structure of federal debt.1

The statutory debt limit applies to almost all federal debt.2 The limit applies to federal debt held by the public (that is, debt held outside the federal government itself) and to federal debt held by the government's own accounts. Federal trust funds, such as Social Security, Medicare, Transportation, and Civil Service Retirement accounts, hold most of this internally held debt.3 For most federal trust funds, net inflows by law must be invested in special federal government securities.4 When holdings of those trust funds increase, federal debt subject to limit will therefore increase as well. The government's on-budget fiscal balance, which excludes the net surplus or deficit of the U.S. Postal Service and the Social Security program, does not directly affect debt held in government accounts.5

The change in debt held by the public is mostly determined by the government's surpluses or deficits.6 The net expansion of the federal government's balance sheet through loan programs also increases the government's borrowing requirements. Under federal budgetary rules, however, only the net subsidy cost of those loans is included in the calculation of deficits.7

Recent Developments

In recent years, Congress has chosen to suspend the debt limit for a set amount of time instead of raising the debt limit by a fixed dollar amount. When a suspension ends, the Treasury Secretary has invoked a set of extraordinary measures that can be used to meet federal obligations.8 How long those measures last depends on general trends in revenue collection and disbursement of outlays, the way that federal debt is managed, and when certain cash resources become available through extraordinary measures authorities. Debt limit developments in late 2017 and early 2018 are summarized here. Earlier developments are described in other sections below.89 The following day, the Senate, by an 80-17 vote, passed an amended version of H.R. 601, which included an amendment (S.Amdt. 808) to suspend the debt limit and provide funding for government operations through December 8, 2017, as well as supplemental appropriations for disaster relief. On September 8, 2017, the House agreed on a 316-90 vote to the amended measure, which the President signed the same day (Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017; P.L. 115-56).

Once the debt limit suspension expires in December 2017, the Treasury Secretary can again invoke authorities to use extraordinary measures to meet federal obligations. Preliminary estimates suggest that those measures might suffice until March 2018, although they might extend for several additional months.9

Extraordinary Measures and Debt Issuance Suspension Periods

Congress has authorized the Treasury Secretary to invoke a "debt issuance suspension period," which triggers the availability of extraordinary measures, which are special strategies to handle cash and debt management. Actions taken in the past include suspending sales of nonmarketable debt, postponing or downsizing marketable debt auctions, and withholding receipts that would be transferred to certain government trust funds. In particular, extraordinary strategies include suspending investments in Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund (CSRDF) and the G-Fund of the Federal Employees' Retirement System (FERS), as well as redeeming a limited amount of CSRDF securities.1013 The Treasury Secretary is also mandated to make those funds whole after the resolution of a debt limit episode.1114

The amount of time that extraordinary measures allow the U.S. Treasury to extend its borrowing capacity depends on the pace of deficit spending, the timing of cash receipts and outlays, and other technical factors. Treasury cash flow projections are subject to significant uncertainties, which further complicate attempts to estimate how long extraordinary measures would enable the federal government to meet its financial obligations. Cash flow projections require analyses of federal spending patterns, the pace of federal debt redemptions and refinancings, and the inflow of receipts, each of which is subject to uncertainties. Estimates calculated by others of when Treasury would reach the debt limit and how long extraordinary measures would extend federal borrowing capacity have typically been close to Treasury's estimates.1215 The U.S. Treasury Inspector General reported in 2012 that "the margin of error in these estimates at a 98 percent confidence level is plus or minus $18 billion for one week into the future and plus or minus $30 billion for two weeks into the future."13

An impending debt ceiling constraint presents more than one deadline. A first deadline is the exhaustion of borrowing capacity. The U.S. Treasury, however, could continue to meet obligations using available cash balances. As cash balances run down, however, other complications could emerge. Low cash balances could complicate federal debt management and Treasury auctions.1417 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has also noted that debt limit episodes generate severe strains for Treasury staff, especially when its room for maneuver is severely restricted.1518 Finally, if the U.S. Treasury were to run out of cash, the Treasury Secretary would face difficult choices in how to comply simultaneously with the debt limit and the mandate to pay federal obligations in a timely fashion.

Severe financial dislocation could result if the U.S. Treasury were unable to make timely payments.1619 For example, repo lending arrangements, which rely heavily on Treasury securities for collateral, could become more expensive or could be disrupted.1720 "Repo" is short for repurchase agreement, which provides a common means of secured lending among financial institutions. Repo lending rates rose sharply in early August 2011 during the 2011 debt limit episode, but fell to previous levels once that episode was resolved.1821

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee indicated in an October 16, 2013, discussion that "in the event of delayed payments on Treasury securities," discount window and other operations would proceed "under the usual terms."1922 That statement has been taken to imply that the Federal Reserve would be "prepared to backstop the Treasury market in the event of a political deadlock."2023 In addition, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York issued a description of contingency plans in December 2013 in the event of Treasury payment delays, but warned that such measures "only modestly reduce, not eliminate, the operational difficulties posed by a delayed payment on Treasury debt. Indeed, even with these limited contingency practices, a temporary delayed payment on Treasury debt could cause significant damage to, and undermine confidence in, the markets for Treasury securities and other assets."21

Recent Increases in the Debt Limit

Table 1 presents debt limit changes over the past two decades. The debt limit was modified six times from 1993 through 1997. Two of those modifications were enacted to prevent the debt limit restriction from delaying payment of Social Security benefits in March 1996 before a broader increase in the debt was passed at the end of that month.2225 After 1997, debt limit increases were unnecessary due to the appearance of federal surpluses that ran from FY1998 through FY2001. Since FY2002 the federal government has run persistent deficits, which have been ascribed to major tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 and higher spending.2326 Those deficits required a series of increases in the debt limit.

Starting with passage of the BCA in August 2011, Congress has employed measures that have led to debt limit increases that occur some time after a law is enacted. Dates in the first column of Table 1 in general refer to dates of enactment, which do not match dates when debt limit increases have occurred. For instance, the debt limit was suspended when P.L. 113-83 was enacted on February 12, 2014, and was reestablished on March 16, 2015, when that suspension lapsed.

|

Date |

Public Law (P.L.) Number |

New Debt Limit |

Change From Previous Limit |

|

April 6, 1993 |

$4,370a |

$225 |

|

|

August 10, 1993 |

4,900 |

530 |

|

|

February 8, 1996 |

— |

||

|

March 12, 1996 |

— |

||

|

March 29, 1996 |

5,500 |

600d |

|

|

August 5, 1997 |

5,950 |

450 |

|

|

June 28, 2002 |

6,400 |

450 |

|

|

May 27, 2003 |

7,384 |

984 |

|

|

November 19, 2004 |

8,184 |

800 |

|

|

March 20, 2006 |

8,965 |

781 |

|

|

September 29, 2007 |

9,815 |

850 |

|

|

July 30, 2008 |

10,615 |

800 |

|

|

October 3, 2008 |

11,315 |

700 |

|

|

February 17, 2009 |

12,104 |

789 |

|

|

December 28, 2009 |

12,394 |

290 |

|

|

February 12, 2010 |

14,294 |

1,900 |

|

|

August 2, 2011 |

16,394e |

2,100e |

|

|

February 4, 2013 |

16,699f |

305f |

|

|

October 17, 2013 |

213g |

||

|

February 15, 2014 |

17,212h |

||

|

March 16, 2015 |

18,113i |

901i |

|

|

March 16, 2017 |

19,809j |

1,696 |

|

|

September 8, 2017 |

Sources: CRS, compiled using the Legislative Information System, available at http://www.congress.gov; OMB; and Daily Treasury Statements.

a.

Increased the debt limit temporarily through September 30, 1993.

The 2011 Debt Limit Episode

The 2011 debt limit episode attracted far more attention than other recent debt limit episodes. In mid-2011 several credit ratings agencies and investment banks expressed concerns about the consequences to the financial system and the economy if the U.S. Treasury were unable to fund federal obligations.2427 Many economists and financial institutions stated that if the market associated Treasury securities with default risks, the effects on global capital markets could be significant.25

Debate during the 2011 debt limit episode reflected a growing concern with the fiscal sustainability of the federal government. While projections issued in 2011 indicated that federal deficits would shrink over the next half decade, deficits later in the decade were expected to rise.2629 Without major changes in federal policies, the amount of federal debt would increase substantially. CBO has repeatedly warned that the current trajectory of federal borrowing is unsustainable and could lead to slower economic growth in the long run as debt rises as a percentage of GDP.2730 Unless federal policies change, Congress would repeatedly face demands to raise the debt limit to accommodate the growing federal debt in order to provide the government with the means to meet its financial obligations.

The next section provides a brief chronology of events from the 2011 debt limit episode.

The 2011 Debt Ceiling Episode Begins

On May 16, 2011, U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner announced that the federal debt had reached its statutory limit and declared a debt issuance suspension period, which would allow certain extraordinary measures to extend Treasury's borrowing capacity until about August 2, 2011.2831 Had the U.S. Treasury exhausted its borrowing authority, it could have used cash balances to meet obligations for some period of time.

Over the course of the 2011 debt limit episode Treasury estimates of when the debt limit would begin to bind and how long extraordinary measures would suffice to meet federal obligations shifted. For instance, in April 2011 the U.S. Treasury had projected that its borrowing capacity, even using extraordinary measures, would be exhausted by about July 8, 2011.2932 The Treasury Secretary, in a letter to Congress dated May 2, 2011, had indicated that he would declare a debt issuance suspension period on May 16, unless Congress acted beforehand, which would allow certain extraordinary measures to extend Treasury's borrowing capacity until early August 2011.3033 On July 1, 2011, the U.S. Treasury confirmed its view that its borrowing authority would be exhausted on August 2, the date cited in Treasury Secretary Geithner's May 16, 2011, letter that invoked the debt issuance suspension period.31

Proposed Solutions in the Spring of 2011

A bill (H.R. 1954) to raise the debt limit to $16,700 billion was introduced on May 24 and was defeated in a May 31, 2011, House vote of 97 to 318. The House passed the Cut, Cap, and Balance Act of 2011 (H.R. 2560; 234-190 vote) on July 19, 2011. The measure would have increased the statutory limit on federal debt from $14,294 billion to $16,700 billion once a proposal for a constitutional amendment requiring a balanced federal budget was transmitted to the states. On July 22, the Senate tabled the bill on a 51-46 vote.

Some commentators in early 2011 suggested that cutting federal spending could slow the growth in federal debt enough to avoid an increase in the debt limit. The scale of required spending reductions, as of the middle of FY2011, would have been large. For example, at the start of the third quarter of FY2011 on April 1, 2011, federal debt was within $95 billion of its limit. According to CBO baseline estimates issued at the time, the expected deficit for the remainder of FY2011 would be about $570 billion. Reaching the end of FY2011 on September 30, 2011, without an increase in the debt limit or the use of extraordinary measures would have thus required a spending reduction of at least $570 billion, or about 85% of discretionary spending for the rest of that fiscal year.32

Some have suggested that the Fourteenth Amendment (Section 4), which states that "(t)he validity of the public debt of the United States ... shall not be questioned," could provide the President with authority to ignore the statutory debt limit. President Obama rejected such claims, as did most legal analysts.3336

The Budget Control Act of 2011

On July 25, 2011, the Budget Control Act of 2011 was introduced in different forms by both House Speaker Boehner (House Substitute Amendment to S. 627) and Majority Leader Reid (S.Amdt. 581 to S. 1323). Subsequently, on August 2, 2011, President Obama signed into law a substantially revised compromise measure (Budget Control Act, BCA; P.L. 112-25), following House approval by a vote of 269-161 on August 1, 2011, and Senate approval by a vote of 74-26 on August 2, 2011.3437 This measure included numerous provisions aimed at deficit reduction, and would allow a series of increases in the debt limit of up to $2,400 billion ($2.4 trillion) subject to certain conditions.3538 These provisions eliminated the need for further increases in the debt limit until early 2013.

In particular, the BCA included major provisions that

- imposed discretionary spending caps, enforced by automatic spending reductions, referred to as a "sequester";

3639 - established a Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, whose recommendations would be eligible for expedited consideration;

- required a vote on a joint resolution on a proposed constitutional amendment to mandate a balanced federal budget;

3740 and - instituted a mechanism allowing for the President and Treasury Secretary to raise the debt ceiling, subject to congressional disapproval.

Debt Limit Increases Under the BCA

The legislation provides a three-step procedure by which the debt limit can be increased. First, the debt limit was raised by $400 billion, to $14,694 billion on August 2, 2011, following a certification of the President that the debt was within $100 billion of its legal limit.3841

A second increase of $500 billion occurred on September 22, 2011, which was also triggered by the President's certification of August 2. The second increase, scheduled for 50 days after that certification, was subject to a joint resolution of disapproval. Because such a resolution could be vetoed, blocking a debt limit increase would be challenging. The Senate rejected a disapproval measure (S.J.Res. 25) on September 8, 2011, on a 45-52 vote. The House passed a disapproval measure (H.J.Res. 77) on a 232-186 vote, although the Senate declined to act on that measure. The resulting increase brought the debt limit to $15,194 billion.

In late December 2011, the debt limit came within $100 billion of its statutory limit, which triggered a provision allowing the President to issue a certification that would lead to a third increase of $1,200 billion.3942 By design, that increase matched budget reductions slated to be made through sequestration and related mechanisms over the FY2013-FY2021 period. That increase was also subject to a joint resolution of disapproval. The President reportedly delayed that request to allow Congress to consider a disapproval measure.4043 On January 18, 2012, the House passed such a measure (H.J.Res 98) on a 239-176 vote. The Senate declined to take up a companion measure (S.J.Res. 34) and on January 26, 2012, voted down a motion to proceed (44-52) on the House-passed measure (H.J.Res 98), thus clearing the way for the increase, resulting in a debt limit of $16,394 billion.

The third increase could also have been triggered in two other ways.4144 A debt limit increase of $1,500 billion would have been permitted if the states had received a balanced budget amendment for ratification. A measure (H.J.Res. 2) to accomplish that, however, failed to reach the constitutionally mandated two-thirds threshold in the House in a 261–165 vote held on November 18, 2011.4245 The debt limit could also have been increased by between $1,200 billion and $1,500 billion had recommendations from the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, popularly known as the Super Committee, been reported to and passed by each chamber. If those recommendations had been estimated to achieve an amount between $1,200 billion and $1,500 billion, the debt limit increase would be matched to that figure. The Joint Select Committee, however, was unable to agree on a set of recommendations.

The Debt Limit in 2013

Debt Limit Reached at End of December 2012

On December 26, 2012, the U.S. Treasury stated that the debt would reach its limit on December 31 and that the Treasury Secretary would declare a debt issuance suspension period to authorize extraordinary measures (noted above, described below) that could be used to meet federal payments for approximately two months.4346 As predicted, federal debt did reach its limit on December 31, when large biannual interest payments, in the form of Treasury securities, were made to certain trust funds.4447

The U.S. Treasury stressed that these extraordinary measures would be exhausted more quickly than in recent debt limit episodes for various technical reasons.4548 A January 14, 2013, letter from Treasury Secretary Geithner also estimated that extraordinary measures would be exhausted sometime between mid-February or early March 2013.4649 CBO had previously estimated that federal debt would reach its limit near the end of December 2012, and that the extraordinary measures could be used to fund government activities until mid-February or early March 2013.4750 During the 112th Congress, Speaker John Boehner had stated that a future debt limit increase should be linked to spending cuts of at least the same magnitude, a position that reflects the structure of the Budget Control Act.4851

Suspension of the Debt Limit Until May 19, 2013

House Republicans decided on January 18, 2013, to propose a three-month suspension of the debt limit tied to a provision that would delay Members' salaries in the event that their chamber of Congress had not agreed to a budget resolution.4952 H.R. 325, according to its sponsor, would allow Treasury to pay bills coming due before May 18, 2013. A new debt limit would then be set on May 19.5053 The measure would also cause salaries of Members of Congress to be held in escrow "(i)f by April 15, 2013, a House of Congress had not agreed to" a budget resolution.5154 Such a provision, however, could raise constitutional issues under the Twenty-Seventh Amendment.

On January 23, 2013, the House passed H.R. 325, which suspended the debt limit until May 19, 2013, on a 285-144 vote. The Senate passed the measure on January 31 on a 64-34 vote; it was then signed into law (P.L. 113-3) on February 4.

Replenishing the U.S. Treasury's Extraordinary Measures

Once H.R. 325 was signed into law on February 4, the U.S. Treasury replenished funds that had been used to meet federal payments, thus resetting its ability to use extraordinary measures. As of February 1, 2013, the U.S. Treasury had used about $31 billion in extraordinary measures.5255 Statutory language that grants the Treasury Secretary the authority to declare a "debt issuance suspension period" (DISP), which permits certain extraordinary measures, also requires that "the Secretary of the Treasury shall immediately issue" amounts to replenish those funds once a debt issuance suspension period (DISP) is over.5356 A DISP extends through "any period for which the Secretary of the Treasury determines for purposes of this subsection that the issuance of obligations of the United States may not be made without exceeding the public debt limit."5457

Shortly after the declaration of a new debt issuance suspension period in February 2013, Jacob Lew was confirmed as Treasury Secretary, replacing Timothy Geithner.55

Debt Limit Reset and Return of Extraordinary Measures in May 2013

Once the debt limit suspension lapsed after May 18, 2013, the U.S. Treasury reset the debt limit at $16,699 billion, or $305 billion above the previous statutory limit. On May 20, 2013, the first business day after the expiration of the suspension, debt subject to limit was just $25 million below the limit.

Some Members, as noted above, stated that H.R. 325 (P.L. 113-3) was intended to prevent the U.S. Treasury from accumulating cash balances. The U.S. Treasury's operating cash balances at the start of May 20, 2013 ($34 billion), were well below balances ($60 billion) at the close of February 4, 2013, when H.R. 325 was enacted.5659 Some experienced analysts had stated that the exact method by which the debt limit would be computed according to the provisions of P.L. 113-3 was not fully clear.5760 The U.S. Treasury has not provided details of how it computed the debt limit after the suspension lapsed.

Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew notified Congress on May 20, 2013, that he had declared a new debt issuance suspension period (DISP), triggering authorities that allow the Treasury Secretary to use extraordinary measures to meet federal obligations until August 2.5861 On August 2, 2013, Secretary Lew notified Congress that the DISP would be extended to October 11, 2013.5962 In those notifications, as well in other communications, Secretary Lew urged Congress to raise the debt limit in a "timely fashion."

Debt Limit Forecasts in 2013

How long the U.S. Treasury could have continued to pay federal obligations absent an increase in the debt limit depended on economic conditions, which affect tax receipts and spending on some automatic stabilizer programs, and the pace of federal spending. Stronger federal revenue collections and a slower pace of federal outlays in 2013 reduced the FY2013 deficit compared to previous years.6063 CBO estimates for July 2013 put the total federal deficit at $606 billion in FY2013, well below the FY2012 deficit of $1,087 billion, implying a slower overall pace of borrowing.6164 Special dividends from mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also extended the U.S. Treasury's ability to meet federal obligations.

In May 2013, the investment bank Goldman Sachs projected that, with the addition of the Fannie Mae dividend and an estimated post-suspensionpostsuspension $16.70 trillion limit, federal borrowing capacity would be exhausted in early October.6265

Estimates of Treasury cash flows are subject to substantial uncertainty. The U.S. Treasury Inspector General reported in 2012 that "the margin of error in these estimates at a 98 percent confidence level is plus or minus $18 billion for one week into the future and plus or minus $30 billion for two weeks into the future."63

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Dividend Payments to the U.S. Treasury

In September 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac entered voluntary conservatorship. As part of their separate conservatorship agreements, Treasury agreed to support Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in return for senior preferred stock that would pay dividends. Losses for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac while in conservatorship have totaled $123 billion, although each has been profitable since the start of 2012. For a profitable firm, some past losses can offset future tax liabilities and would be recognized on its balance sheet as a "deferred tax asset" under standard accounting practices. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac wrote down the value of their tax assets because their return to profitability was viewed as unlikely.

The return of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to profitability opened the possibility for a reversal of those writedowns.6467 On May 9, 2013, Fannie Mae announced that it would reverse the writedown of its deferred tax assets.6568 The Treasury agreements, as amended, set the dividend payments to a sweep (i.e., an automatic transfer at the end of a quarter) of Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's net worth. Thus a reversal of that writedown of the deferred tax assets triggered a payment of about $60 billion from Fannie Mae to the U.S. Treasury on June 28, 2013.6669 The U.S. Treasury received $66.3 billion from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac on that date.6770 Fannie Mae stated that it would pay an additional $10.2 billion in September 2013.6871 On August 7, 2013, Freddie Mac announced that it had not yet decided to write down its deferred tax assets of $28.6 billion, but that it could do so later.69

Treasury Secretary Lew's Message to Congress in 2013

In May 2013, Secretary Lew had notified Congress that he expects the U.S. Treasury will be able to meet federal obligations until at least Labor Day.7073 Some private estimates suggest that the U.S. Treasury, with the assistance of extraordinary measures, would probably be able to meet federal obligations until mid-October or November 2013.7174 By comparison, in 2011, Treasury Secretary Geithner invoked authority to use extraordinary measures on May 16, 2011, which helped fund payments until the debt ceiling was raised on August 2, 2011.72

On August 26, 2013, Treasury Secretary Lew notified congressional leaders that the government would exhaust its ability to borrow in mid-October according to U.S. Treasury projections. At that point, the U.S. Treasury would have only an estimated $50 billion in cash to meet federal obligations.7376 With that cash and incoming receipts, the U.S. Treasury would be able to meet obligations for some weeks after mid-October according to independent analysts, although projecting when cash balances would be exhausted is difficult.7477

On September 25, 2013, Secretary Lew sent another letter to Congress with updated forecasts of the U.S. Treasury's fiscal situation.7578 According to those forecasts, the U.S. Treasury would exhaust its borrowing capacity no later than October 17. At that point, the U.S. Treasury would have about $30 billion in cash balances on hand to meet federal obligations. At the close of business on October 8, 2013, the U.S. Treasury had an operating cash balance of $35 billion.76

On October 3, 2013, the U.S. Treasury issued a brief outlining potential macroeconomic effects of the prospect that the federal government would be unable to pay its obligations in a timely fashion.7780 The brief provided data on how various measures of economic confidence, asset prices, and market volatility responded to the debt limit episode in the summer of 2011.

When Might the Debt Limit Have Been Binding?

In the absence of a debt limit increase, the cash balances on hand when the U.S. Treasury's borrowing capacity ran out would then dwindle. At the close of business on October 11, 2013, the U.S. Treasury's cash balance was $35 billion.7881 Those low cash balances, however, could raise two complications even before that point.

First, low cash balances could have complicated federal debt management and Treasury auctions in late October or early November.7982 Yields for Treasury bills maturing after the October 17 date mentioned in Secretary Lew's September 25 letter have increased relative to other yields on other Treasury securities. This appeared to signal reluctance among some investors to hold Treasury securities that might be affected by debt limit complications.

Second, repo lending, which relies heavily on Treasury securities for collateral, could become more expensive or could be disrupted.8083 Repo lending rates rose sharply in early August 2011 during the 2011 debt limit episode, but fell to previous levels once that episode was resolved.81

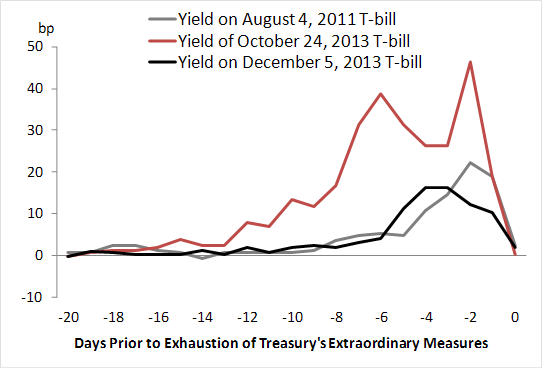

Market Reaction to the Impending Exhaustion of Treasury's Borrowing Capacity in October 2013

In the past, some financial markets have reacted to impending debt limit deadlines, signaling concerns about the federal government's ability to meet obligations in a timely manner. In early October 2013, the U.S. Treasury issued a brief that outlined how various measures of economic confidence, asset prices, and market volatility responded to the debt limit episode in the summer of 2011, and the prospect that the federal government might not have been able to pay its obligations in a timely fashion.82

Some investors expressed reluctance to hold Treasury securities that might be affected by debt limit complications. Fidelity Investments, J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc., and certain other funds stated in October 2013 that they had sold holdings of Treasury securities scheduled to mature or to have coupon payments between October 16 and November 6, 2013.83

In October 2013, yields for Treasury bills maturing in the weeks after October 17—when the U.S. Treasury's borrowing capacity was projected to be exhausted—rose sharply relative to yields on Treasury securities maturing in 2014. Figure 1 shows secondary market yields on Treasury bills set to mature after the projected date when the Treasury's borrowing capacity would be exhausted.8487 The horizontal axis shows days before the end of the DISP, and the vertical scale shows basis points (bps). For instance, the yield for the Treasury bill maturing October 24, 2013, rose from close to zero to 46 bps on October 15, 2013. Those yields are about 10 times larger than for similar bills that mature in calendar year 2014.8588 A four-week Treasury bill auctioned on October 8, 2013, sold with a yield of 35 bps. By contrast, a four-week bill sold on September 4, 2013, sold with a yield of 2 bps.8689 After enactment of a debt limit measure (H.R. 2775; P.L. 113-46) on October 16, 2013, however, those yields returned to their previous levels.

Debt Limit Issues in 2013

Congressional consideration of federal debt policy raised several policy issues that were explored in hearings and in broader policy discussions.

Hearings in 2013

On January 22, 2013, the House Ways and Means Committee held hearings on the history of the debt limit and how past Congresses and Presidents have negotiated changes in the debt limit.8790 On April 10, 2013, the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Oversight held hearings on federal debt and fiscal management when the debt limit binds.8891

The Joint Economic Committee held hearings on the economic costs of uncertainty linked to the debt limit on September 18, 2013.89

On October 10, 2013, the Senate Finance Committee held hearings on the debt limit and heard testimony from Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew.9093 On the same morning, the Senate Banking Committee held hearings on the effects of a possible federal default on financial stability and economic growth, and heard testimony from heads of financial industry trade associations.91

Debt Prioritization and H.R. 807

On April 30, 2013, the House Ways and Means Committee reported H.R. 807, which would grant the Treasury Secretary the authority to borrow to fund principal and interest payments on debt held by the public and the Social Security trust funds if the debt limit were reached.9295 The Treasury Secretary would also have had to submit weekly reports to Congress after that authority were exercised. On May 9, 2013, the House passed and amended version of H.R. 807.9396 The House also passed a version of H.J.Res. 59 that incorporated the text of H.R. 807 on September 20. On September 27, the Senate passed an amended version of the measure that did not contain provisions from H.R. 807. The Obama Administration indicated that it would veto H.R. 807 or H.J.Res. 59 containing similar provisions, were either to be approved by Congress.9497 The October 2013 debt limit measure (H.R. 2775; P.L. 113-46) contained no payment prioritization provisions.

H.R. 807 would have affected one aspect of the U.S. Treasury's financial management of the Social Security program, but would not alter other aspects. If the debt limit were reached, the U.S. Treasury could still face constraints that could raise challenges in financial management. The U.S. Treasury is responsible for (1) making Social Security beneficiary payments; (2) reinvesting Social Security payroll taxes and retirement contributions in special Treasury securities held by the Social Security trust fund; and (3) paying interest to the Social Security trust funds, in the form of special Treasury securities, at the end of June and December.9598 Those special Treasury securities, either funded via Social Security payroll receipts or biannual interest payments, are subject to the debt limit. Thus, sufficient headroom under the debt limit is needed to issue those special Treasury securities. If the debt limit were reached and extraordinary measures were exhausted, the Treasury Secretary's legal requirement to reinvest Social Security receipts by issuing special Treasury securities could at times be difficult to reconcile with his legal requirement not to exceed the statutory debt limit.

Resolution of the Debt Limit Issue in October 2013

On September 25, Treasury Secretary Lew notified Congress that the government would exhaust its borrowing capacity around October 17 according to updated estimates. At that point, the U.S. Treasury would have had a projected cash balance of only $30 billion to meet federal obligations.

On October 16, 2013, Congress passed a continuing resolution (Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014; H.R. 2775; P.L. 113-46) that included a provision to allow a suspension of the debt limit. That measure passed the Senate on an 81-18 vote.9699 The House then passed the measure on a 285-144 vote. The President signed the bill (P.L. 113-46) early the next morning. The measure suspended the debt limit until February 8, 2014, once the President certified that the U.S. Treasury would be unable to meet existing commitments without issuing debt.97100 The President sent congressional leaders a certification on October 17, 2013, to trigger a suspension of the debt limit through February 7, 2014.98

That suspension, however, was subject to a congressional resolution of disapproval. If a resolution of disapproval had been enacted, the debt limit suspension would end on that date. Specific expedited procedures in each chamber governed the consideration of the resolution of disapproval. The resolution, if passed, was subject to veto. A resolution of disapproval (H.J.Res. 99) was passed in the House on October 20, 2013, on a 222-191 vote. A similar measure, S.J.Res. 26, was not approved by the Senate, so the debt limit increase was not blocked.99

The debt limit suspension ended on February 7, and a limit was set to reflect the amount of debt necessary to fund government operations before the end of the suspension. The U.S. Treasury was precluded in P.L. 113-46 from accumulating excess cash reserves that might have allowed an extension of extraordinary measures.

The debt limit provisions enacted in October 2013 resemble provisions enacted in 2011 and earlier in 2013. For example, the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) also provided for a congressional resolution of disapproval of a debt limit increase. The suspension of the debt limit in H.R. 2775 resembles the suspension enacted in February 2013 (H.R. 325; P.L. 113-3).100

Other Proposals Regarding the Debt Limit in October 2013

Passage of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014 was preceded by other proposals to modify the debt limit. On October 8, 2013, Senate Majority Leader Reid introduced S. 1569, a measure intended to ensure complete and timely payment of federal obligations. The measure would have extended the suspension of the debt limit enacted in February 2013 (P.L. 113-3). On October 15, 2013, an announcement of a hearing on a proposal to amend the Senate amendment to H.J.Res. 59 appeared on the House Rules Committee website. That hearing, according to a subsequent announcement, was postponed that evening. The measure would extend the debt limit through February 15, 2014, and restrict the Treasury Secretary's ability to employ extraordinary measures through April 15, 2014. The measure would also extend discretionary funding at "sequester levels" through December 15, 2013.101

The Debt Limit in 2014

The resolution of the debt limit episode and the ending of the federal shutdown in October 2013 set up a subsequent episode in early 2014.

Debt Limit Forecasts in Late 2013 and 2014

In late November 2013, CBO issued an analysis of Treasury cash flows and available extraordinary measures.102105 Treasury, according to those estimates, might exhaust its ability to meet federal obligations in March. Because Treasury cash flows can be highly uncertain during tax refund season, CBO stated that that date could arrive as soon as February 2014 or as late as early June.

Goldman Sachs had estimated that Treasury would probably exhaust its headroom—the sum of projected cash balances and remaining borrowing authority under the debt limit—in mid to late March, but might in fortuitous circumstances be able to meet its obligations until June.103106 While Goldman Sachs and other independent forecasters noted that that the U.S. Treasury might possibly avoid running out of headroom in late March or early April, waiting until mid-March to address the debt limit could have raised serious risks for the U.S. government's financial situation.104

Treasury Secretary Lew Notifies Congress in Early 2014

As the end of the debt limit suspension neared, the U.S. Treasury continued to warn Congress of the consequences on not raising the debt limit. While the Treasury could again employ extraordinary measures after the suspension ended after February 7, 2014, its ability to continue meeting federal obligations would be limited by large outflows of cash resulting from individual income tax refunds. In December 2013, the U.S. Treasury had notified congressional leaders that according to its estimates, extraordinary measures would extend its borrowing authority "only until late February or early March 2014."105108 On January 22, 2014, Secretary Lew called for an increase in the debt limit before the end of debt limit suspension on February 7, 2014, or the end of February.106109 In the first week of February 2014, Secretary Lew stated that the U.S. Treasury could not be certain that extraordinary measures would last beyond February 27, 2014.107

Debt Limit Suspension Lapses in February 2014

On February 7, 2014, the debt limit suspension ended and the U.S. Treasury reset the debt limit to $17,212 billion.108111 On the same day, the U.S. Treasury also suspended sales of State and Local Government Series (SLGS), the first of its extraordinary measures.109112 On February 10, Secretary Lew notified Congress that he had declared a debt issuance suspension period (DISP) that authorizes use of other extraordinary measures. In particular, during a DISP the Treasury Secretary is authorized to suspend investments in the Civil Service and Retirement and Disability Fund and the G Fund of the Federal Employees' Retirement System. The DISP was scheduled to last until February 27.110

Debt Limit Again Suspended Until March 2015

Following the lapse of the debt limit suspension, Congress moved quickly to address the debt limit issue. On February 10, 2014, the House Rules Committee posted an amended version of S. 540 that would suspend the debt limit through March 15, 2015. The debt limit would be raised the following day by an amount tied to the amount of borrowing required by federal obligations during the suspension period. The U.S. Treasury would also be prohibited from creating a cash reserve above that level. The measure also would have reversed a 1% reduction in the cost-of-living adjustment for certain working-age military retirees that had been included in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA; P.L. 113-67).111114 In addition, sequestration of non-exemptnonexempt mandatory spending would be extended from FY2023 to FY2024. CBO issued a cost estimate of the measure on February 11, 2014.112

On February 11, 2014, the House voted 221-201 to suspend the debt limit (S. 540) through March 15, 2015. The amended measure included restrictions on Treasury debt management in the version reported by the Rules Committee, but omitted provisions to reverse reductions in cost-of-living adjustments to working-age military retiree pensions and an extension of non-defensenondefense mandatory sequestration.113116 The Senate voted to concur in the House amendment the following day on a 55-43 vote. The President signed the measure (P.L. 113-83) on February 15, 2014. Unlike previous measures that suspended the debt limit, a presidential certification was not required. A separate measure was also signed into law on the same day (P.L. 113-82) to reverse reductions in cost-of-living adjustments to working-age military retiree pensions for those who entered the military before the beginning of 2014.

The Debt Limit in 2015

The debt limit, which had been suspended through March 15, 2015, was reestablished the following day at $18,113 billion. The debt limit was raised, in essence, by the sum of payments made during the suspension period to meet federal obligations.114117

Treasury's Extraordinary Measures in 2015

Treasury Secretary Lew sent congressional leaders a letter on March 6, 2015, stating that Treasury would suspend issuance of State and Local Government Series (SLGS) bonds on March 13, 2015, the last business day during the current debt limit suspension. SLGS are used by state and local governments to manage certain intergovernmental funds in a way that complies with federal tax laws.115118

Once the most recent debt limit suspension lapsed, Treasury Secretary Lew declared a Debt Issuance Suspension Period (DISP) on March 16, 2015, which empowered him to use extraordinary measures to meet federal fiscal obligations until July 30, 2015.116119 On July 30, 2015, Treasury Secretary Lew sent congressional leaders a letter to invoke extraordinary powers again until the end of October.117120 Secretary Lew indicated in a separate letter, sent the previous day, that those extraordinary measures would enable the U.S. Treasury to meet federal financial obligations "for at least a brief additional period of time" after the end of October.118121 Secretary Lew sent another letter on September 10, 2015, that reiterated those points.119

Cash Management Changes

In May 2015, the U.S. Treasury changed its cash management policy to adopt recommendations of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee and an internal review.120123 The new policy is intended to ensure that the U.S. Treasury could continue to meet federal obligations even if its market access were disrupted for a week or so. Treasury Secretary Lew noted that an event of the scale such as "Hurricane Sandy, September 11, or a potential cyber-attack disruption" might cause a lapse in market access.121124 The new cash management policy does not affect the date when the debt limit might constrain the U.S. Treasury's ability to meet federal obligations.

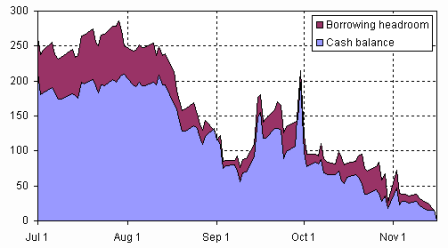

What is the U.S. Treasury's Headroom Under the Debt Limit?

The U.S. Treasury's headroom under the debt limit consists of remaining amounts of funds available for extraordinary measures and available cash reserves. When federal receipts exceed federal outlays, that headroom expands, except for those receipts or outlays that are linked to intragovernmental accounts such as Social Security. The headroom gained by those receipts is exactly offset because Treasury must issue special securities to the appropriate intragovernmental trust fund, and those securities are subject to the debt limit. Conversely, when outlays are funded by such intragovernmental accounts, the increase in Treasury's headroom due to redemption of special securities is offset by Treasury's need to provide funding for that redemption either by drawing down cash balances or additional borrowing.

How Long Would Extraordinary Measures Last in 2015?

On October 15, 2015, Secretary Lew stated that extraordinary measures would be exhausted "no later than" November 3, 2015, although a relatively small cash reserve—projected at less than $30 billion—would be on hand.122125 Secretary Lew had previously stated that extraordinary measures would be exhausted about November 5, 2015.123

The most recent independent forecasts of when extraordinary measures would be exhausted are close to the date estimated by the U.S. Treasury. One private forecast estimated Treasury's headroom under the debt limit at $38 billion on November 5, 2015.124127 CBO, according to an October 14, 2015, report, projects that "Treasury will begin running a very low cash balance in early November, and the extraordinary measures will be exhausted and the cash balance entirely depleted sometime during the first half of November."125128 Figure 2 shows one recent independent estimate of Treasury's headroom that shows Treasury's available resources falling below $50 billion after the first few days of November.

Why Did the Estimated Date of Treasury's Exhaustion of Borrowing Capacity Move Up?

Previous independent estimates of when Treasury's borrowing capacity would be exhausted, however, had suggested that leaving the debt limit at its present level would suffice until the end of November or even early December. For example, CBO's August 2015 projections had put the estimated date of exhaustion somewhere between mid-November and early December 2015.126

Lower than expected tax receipts during the fall of 2015 and higher than expected federal trust fund investments pushed the date back from what outside forecasters had expected earlier in the year. For example, net issuance of Government Account Series securities—which includes special Treasury securities held by federal trust funds—was about $10 billion higher on the first day of FY2016 as compared to the first day of FY2015.127130 On October 9, 2015, the U.S. Treasury issued a summary of debt balances that provided a more detailed view of its headroom under the debt limit.128131 According to that summary, Treasury has used $355 billion of its available $369 billion in extraordinary measures as of October 7, 2015, leaving $14 billion to meet forthcoming obligations.

Secretary Lew noted in previous correspondence with Congress that projections of Treasury's ability to meet federal obligations were subject to significant uncertainty due to the variability of federal tax collections and expenditure patterns. While the U.S. Treasury's payment calendar, tax due dates, and securities auction schedule are generally regular and predictable, the amounts paid or received on a given day can fluctuate substantially.

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 and the Resolution of the 2015 Debt Limit Episode

Late on the night of October 26, 2015, text of the Bipartisan Budget Agreement of 2015 was issued. The proposal, among other provisions, would suspend the debt limit until March 15, 2017. The debt limit would then come back into effect on the following day at a level reflecting the payment of federal obligations incurred during the suspension period. As with previous debt limit suspensions, the measure prohibits the U.S. Treasury from creating a cash reserve beyond amounts necessary to meet federal obligations during the suspension period. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 would also increase statutory caps on discretionary spending for FY2016 and FY2017, along with measures aimed at offsetting those increases.

On October 27, 2015, the House Rules Committee provided a summary of its provisions and put forth an amendment aimed at addressing certain scoring issues.129132 The following day, the House concurred with a modified version of the Senate amendments to H.R. 1314 on a 266-167 vote. The Senate concurred with that version on October 30, 2015, on a 64-35 vote, sending the measure to the President, who signed it (P.L. 114-74) on November 2, 2015.130133

Enactment of the measure thus resolved the 2015 debt limit episode by suspending the debt limit until March 15, 2017. After that date, extraordinary measures would then allow the Treasury Secretary to meet federal obligations until sometime in the fall of 2017, presuming no material change in economic conditions and federal policies on spending and revenues.

Other Developments in 2015 and 2016

On September 10, 2015, the House Ways and Means Committee reported H.R. 692, which would grant the Treasury Secretary the authority to borrow to fund principal and interest payments on debt held by the public.131134 The measure resembles H.R. 807, which was considered in 2013 and is discussed above. The House passed H.R. 692 on October 21, 2015, by a 235-194 vote.

The House Ways and Means Committee also reported H.R. 3442 on the same date, which would require the Treasury Secretary to appear before the House Committee on Ways and Means and the Senate Committee on Finance during a debt limit episode and to submit a report on the federal debt.132135

The U.S. Treasury submitted two reports to Congress on extraordinary measures used during the 2015 debt limit episode. The first described actions affecting the G Fund133136 and the second described actions taken affecting the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund.134

In May 2015, Treasury officials announced a policy shift to maintain a larger cash balance—not less than approximately $150 billion in normal circumstances—that would suffice to meet federal obligations in the event of a week-long disruption of access to capital markets.135138 During a November 2, 2016, meeting between Treasury officials and a panel of financiers, concerns were raised that the interaction of debt limit constraints in 2017 with changes in the structure of money market funds (MMFs) that have increased demand for Treasury bills could risk disruption of short-term funding markets.136

Developments in 2017

and 2018On March 7, 2017, CBO issued estimates that extraordinary measures could suffice to meet federal obligations until sometime in the fall of 2017.137140 Such estimates are subject to substantial uncertainty due to changes in economic conditions, federal revenue flows, changes in the amounts and timing of federal payments, and other factors. On March 8, 2017, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin notified Congress that he would invoke authorities to use extraordinary measures after March 15, 2017, to ensure continued payment of federal obligations.138141 On March 16, 2017, Secretary Mnuchin notified congressional leaders that he had indeed exercised those authorities.139142 The debt limit on that date was reset at $19,809 billion.140143

Administration Officials Urge Congress to Act

In testimony before Congress on May 24, 2017, Administration officials urged Congress to raise the debt limit before its summer recess.141144 Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Director Mick Mulvaney stated that the federal receipts were coming in more slowly than projected, which could imply that Treasury's capacity to meet federal obligations could be exhausted sooner than previously projected.142145 A Goldman Sachs analysis found, however, that some major categories of tax receipts had shown stronger growth.143146

On June 28, 2017, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin sent a letter to Congress stating that extraordinary measures would be used until September 29, 2017.144147 Secretary Mnuchin's letter did not state that Treasury's cash reserves or borrowing capacity would be exhausted on that date, but he did describe the need for legislative action by that date as "critical." Others had estimated that the U.S. Treasury would likely be able to meet federal obligations until sometime in early October 2017.145148 Treasury cash balances and borrowing capacity in mid-September, however, were projected to fall well below levels the U.S. Treasury has considered prudent to maintain operations in the face of significant adverse events.146

Debt Limit Again Suspended in September 2017

On September 3, 2017, Secretary Mnuchin argued that a debt limit measure should be tied to legislation responding to Hurricane Harvey, which caused extensive damage in southeast Texas.147150

On September 6, 2017, outlines of an agreement on the debt limit and a continuing resolution were announced between President Trump and congressional leaders.148151 The following day, the Senate, by an 80-17 vote, passed an amended version of H.R. 601, which included an amendment (S.Amdt. 808) to suspend the debt limit and provide funding for government operations through December 8, 2017, as well as supplemental appropriations for disaster relief. On September 8, 2017, the House agreed on a 316-90 vote to the amended measure, which the President signed the same day (Continuing Appropriations Act, 2018 and Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Requirements Act, 2017; P.L. 115-56).

Once the debt limit suspension expires in December 2017, the Treasury Secretary can again invoke authorities to use extraordinary measures to meet federal obligations. Preliminary estimates suggest that those measures might suffice until March 2018, although they might extend for several additional months.149

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For details, see CRS Report RL31967, The Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||

| 2. |

Approximately 0.5% of total debt is excluded from debt limit coverage. The Treasury defines "Total Public Debt Subject to Limit" as "the Total Public Debt Outstanding less Unamortized Discount on Treasury Bills and Zero-Coupon Treasury Bonds, old debt issued prior to 1917, and old currency called United States Notes, as well as Debt held by the Federal Financing Bank and Guaranteed Debt." For details, see http://www.treasurydirect.gov. The debt limit is codified as 31 U.S.C. §3101. |

|||||

| 3. |

Although there are hundreds of trust funds, the overwhelming majority are very small. The 12 largest trust funds hold 98.8% of the federal debt held in government accounts. See CRS Report R41815, Overview of the Federal Debt, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||

| 4. |

The National Railroad Retirement Investment Trust, which funds certain railroad retirement benefits, holds a mix of federal and private assets. |

|||||

| 5. |

In future years, when some trust funds are projected to pay out more than they take in, funds that the Treasury would use to redeem those intergovernmental debts must be obtained via higher taxes or lower government spending. |

|||||

| 6. |

Federal debt also increases when the U.S. government's balance sheet expands to fund federal credit programs. Seigniorage and other adjustments also affect the level of federal debt. For a crosswalk between the annual federal deficit and the increase in federal debt, see OMB, FY2014 Analytical Perspectives, Table 5-2, Federal Government Financing and Debt. |

|||||

| 7. |

For details, see CRS Report R44193, Federal Credit Programs: Comparing Fair Value and the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||

| 8. |

See CRS Insight IN10837, "Extraordinary Measures" and the Debt Limit, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

|

|||||

|

| ||||||

| 11.

|

|

See Wrightson ICAP, "Updated Treasury Cash Flow Projections—Again," Money Market Observer, January 1, 2018. Also see Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Federal Debt and the Statutory Limit, November 2017, November 30, 2017; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53336. 12.

|

|

Saleha Mohsin and Steven T. Dennis, "Treasury Asked Congress to Raise Debt Limit by Feb. 28, Sources Say," Bloomberg Politics, January 8, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-01-08/treasury-asks-congress-to-raise-debt-limit-by-end-of-february. |

For details, see out-of-print CRS Report 95-1109, Authority to Tap Trust Funds and Establish Payment Priorities if the Debt Limit is Not Increased, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. Available upon request from the authors. 5 U.S.C. §8348(b) defines a debt issuance suspension period as "any period for which the Secretary of the Treasury determines for purposes of this subsection that the issuance of obligations of the United States may not be made without exceeding the public debt limit." After a debt issuance suspension period ends, the Treasury Secretary must report to Congress as soon as possible regarding fund balances and any extraordinary actions taken. For details, see 5 U.S.C. §8348(j,k). For a list of extraordinary measures, see U.S. Government Accountability Office, Analysis of 2011-2012 Actions Taken and Effect of Delayed Increase on Borrowing Costs, GAO-12-701, July 2012, Table 1, p. 8, available at http://www.gao.gov/assets/600/592832.pdf. |

|

|

5 U.S.C. §8348(j)(3). |

||||||

|

Wrightson ICAP, The Money Market Observer, May 2, 2011; Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Timothy Geithner, letter to Majority Leader Harry Reid, dated January 6, 2011, available at http://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Letter.pdf. |

||||||

|

Department of the Treasury, Office of the Inspector General, "Response to Senator Hatch Regarding Debt Limit in 2011," OIG-CA-12-006, August 24, 2013, enclosure 1, p. 2, available at http://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/ig/Audit%20Reports%20and%20Testimonies/Debt%20Limit%20Response%20%28Final%20with%20Signature%29.pdf. |

||||||

|

Wrightson ICAP, "Summer Break Issue," Money Market Observer, September 2, 2013. |

||||||

|

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Analysis of 2011-2012 Actions Taken and Effect of Delayed Increase on Borrowing Costs, GAO-12-701, July 2012, available at http://www.gao.gov/assets/600/592832.pdf. |

||||||

|

For details, see testimony from the Senate Banking Committee hearings of October 10, 2013 noted below. |

||||||

|

For background, see Tobias Adrian et al., "Repo and Securities Lending," Federal Reserve of New York Staff Report No. 529, revised version February 2013, available at http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr529.pdf. |

||||||

|

RBC Capital Markets, U.S. Economics and Rates Focus, September 25, 2013. |

||||||

|

Federal Reserve, "FOMC Minutes for October 29-30, 2013 Meeting," videoconference meeting of October 16, p. 11, available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20131030.pdf. |

||||||

|

Wrightson ICAP, "Debt Ceiling Outlook," Money Market Observer, January 27, 2014. |

||||||

|

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Treasury Market Practices Group, Operational Plans for Various Contingencies for Treasury Debt Payments, December 23, 2013, available at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/microsites/tmpg/files/Operations_Contingency_Plans.pdf. |

||||||

|

For a description of the budget cycle in FY1966, see CRS Report RS20348, Federal Funding Gaps: A Brief Overview, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

|

See CBO, "Changes in CBO's Baseline Projections Since January 2001," June 7, 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/06-07-ChangesSince2001Baseline.pdf. According to CBO estimates, over the FY2002-FY2011 period legislative changes in federal revenue policies accounted for a change of -$6.1 trillion; legislative changes in spending policies accounted for an estimated increase of $5.6 billion over that period; and concomitant net interest costs resulted in a change of $1.4 trillion; all relative to the FY2001 CBO current-law baseline. Economic and technical factors accounted for about 10% of the divergence between FY2001 baseline projections and actual budget results. The four discretionary subfunctions with the largest real increases in outlays between FY2001 and FY2011 were Defense-Military ($322 billion); Elementary, secondary, and vocational education ($34 billion); Hospital and medical care for veterans ($25 billion); and ground transportation ($18 billion), all expressed in FY2013 dollars. The four mandatory subfunctions with the largest real increases in outlays over the same period were Medicare ($221 billion); Social Security ($196 billion); Health care services ($140 billion); and Unemployment compensation ($86 billion). See also Alan J. Auerbach and William G. Gale, "The Economic Crisis and the Fiscal Crisis: 2009 and Beyond," Tax Notes special report, October 5, 2009. |

||||||

|

Reuters, "S&P to Deeply Cut U.S. Ratings If Debt Payment Missed," June 29, 2011. For a summary of statements by the three major ratings agencies, see CRS Report R41932, Treasury Securities and the U.S. Sovereign Credit Default Swap Market, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

|

JPMorgan Chase, "The Domino Effect of a US Treasury Technical Default," U.S. Fixed Income Strategy Group Brief, April 19, 2011; Fitch Ratings, "Thinking the Unthinkable—What if the Debt Ceiling Was Not Increased and the US Defaulted?" June 8, 2011. |

||||||

|

Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for Fiscal Year 2012, April 15, 2011, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/22087. |

||||||

|

Congressional Budget Office, The 2013 Long-Term Budget Outlook, September 17, 2013, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/44521. |

||||||

|

Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Timothy Geithner, letter to Majority Leader Harry Reid, dated May 16, 2011, available at http://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/20110516Letter%20to%20Congress.pdf. |

||||||

|

Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Timothy Geithner, letter to Majority Leader Harry Reid, dated April 4, 2011, available at http://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/FINAL%20Letter%2004-04-2011%20Reid%20Debt%20Limit.pdf. |

||||||

|

Secretary of the U.S. Treasury Timothy Geithner, letter to Speaker John Boehner, dated May 2, 2011, available at http://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/FINAL%20Debt%20Limit%20Letter%2005-02-2011%20Boehner.pdf. The same text was sent to all Members. |

||||||

|

U.S. Treasury, "Treasury: No Change to August 2 Estimate Regarding Exhaustion of U.S. Borrowing Authority," Press release tg-1225, July 1, 2011, available at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/tg1225.aspx. |

||||||

|

According to the U.S. Treasury's Daily Treasury Statement for April 1, debt subject to limit was $14,198.9 billion, just $95.1 billion below the limit at that time of $14,294 billion; (https://fms.treas.gov/fmsweb/viewDTSFiles?dir=a&fname=11040100.pdf). According to the CBO baseline estimates issued in March 2011 (Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposals for FY2012, April 15, 2011, http://www.cbo.gov/publication/22087), the estimated deficit for FY2011 was $1,399 billion and estimated discretionary outlays were $1,361 billion. According to the April 2011 CBO Monthly Budget Review (http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/121xx/doc12126/mbr_april_2011.pdf), the deficit for the first half of FY2011 was $830 billion. |

||||||

|

Adam Liptak, "The 14th Amendment, the Debt Ceiling and a Way Out," New York Times, January 24, 2011; Remarks by the President at University of Maryland Town Hall, available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/07/22/remarks-president-university-maryland-town-hall. For a legal analysis, see CRS congressional distribution memorandum, Whether the Public Debt Clause Authorizes the President to Borrow Money in Excess of the Debt Ceiling, December 21, 2012, by [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

|

Consideration of this measure began on July 25, 2011, following legislation introduced by House Speaker Boehner (House Substitute Amendment to S. 627) and Majority Leader Reid (S.Amdt. 581 to S. 1323). Speaker Boehner's proposal passed the House on July 29, 2011, by a vote of 218-210. Neither proposal passed in the Senate. |

||||||

|

For details, see CRS Report R41965, The Budget Control Act of 2011, by [author name scrubbed], [author name scrubbed], and [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

|

Sequestration is a mechanism that directs the President to cancel budget authority or other forms of budgetary resources in order to reach specified budget reduction targets. Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-177), often known as Gramm-Rudman-Hollings (GRH), introduced sequestration procedures into the federal budget process. Those sequestration procedures were modified in subsequent years to address separation of powers issues and other concerns. For details, see CRS Report R41901, Statutory Budget Controls in Effect Between 1985 and 2002, by [author name scrubbed]. Also see The Budget Control Act and Alternate Defense and Non-Defense Spending Paths, FY2012-FY2021, congressional distribution memorandum, November 16, 2012, available from authors upon request. |

||||||

|

See CRS Report R41907, A Balanced Budget Constitutional Amendment: Background and Congressional Options, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

||||||

|

White House, Message from the President to the U.S. Congress, August 2, 2011, available at http://m.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/08/02/message-president-us-congress. |

||||||

|

For example, on December 30, 2011, debt subject to limit was $15,180 billion, just $14 billion below its statutory limit. The U.S. Treasury pays interest to Social Security and certain other trust funds in the form of Treasury securities at the end of June and December, which increases debt subject to limit. |

||||||

|

CQ Roll Call Daily Briefing, January 3, 2012. |

||||||

|

Congress could have considered a joint resolution of disapproval for this increase. |

||||||

|

Ratification requires approval by legislatures of three-fourths of the states. Article V specifies other means of amendment involving constitutional conventions as well. |

||||||

|

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, letter to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, December 26, 2012. Identical letters were sent to other congressional leaders. Presently and in similar past circumstances, the U.S. Treasury has held debt subject to limit $25 million below the statutory limit. Large biannual interest payments to certain trust funds are due on December 31. |

||||||

|

The debt issuance suspension period was officially declared on December 31, 2012. See Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, letter to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, December 31, 2012, available at http://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/Documents/Sec%20Geithner%20Letter%20to%20Congress%2012-31-2012.pdf. |

||||||

|

See Appendix to the December 26, 2012, letter to Majority Leader Reid, available at https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Sec%20Geithner%20LETTER%2012-26-2012%20Debt%20Limit.pdf. |

||||||

|

Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, letter to House Speaker John A. Boehner, January 14, 2013, available at http://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/1-14-13%20Debt%20Limit%20FINAL%20LETTER%20Boehner.pdf. |

||||||

|

CBO, Federal Debt and the Statutory Limit, November 2012, available at http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/43736-FederalDebtLimit-11-12-12.pdf. |

||||||

|

Speaker John Boehner, "Address on the Economy, Debt Limit, and American Jobs," May 16, 2012, prepared text available at http://www.speaker.gov/speech/full-text-speaker-boehners-address-economy-debt-limit-and-american-jobs. |

||||||

|

Jonathan Weisman, "In Reversal, House G.O.P. Agrees to Lift Debt Limit," New York Times, January 19, 2013, p. A1; Speaker John Boehner, "Speaker Boehner: No Budget, No Pay," speech excerpt, January 18, 2013, available at http://www.speaker.gov/speech/speaker-boehner-no-budget-no-pay. |

||||||

|

Ways & Means Chair David Camp, House debate, Congressional Record, vol. 159 (January 23, 2013), p. H237. |

||||||

|

H.R. 325 (P.L. 113-3) §3. |

||||||

|

In the Daily Treasury Statement for February 4, 2013 (available at http://fms.treas.gov/dts/index.html), Table III-A shows a net change in Government Account Series of nearly $42 billion. About $31 billion of that amount reflects replenishment of funds used for extraordinary measures, with the rest reflecting trust fund operations and other activities. Treasury Assistant Secretary for Financial Markets Matthew Rutherford, in a February 6, 2013, quarterly refunding press conference mentioned that the U.S. Treasury had replenished those funds (see webcast: http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/Video-Audio-Webcasts/Pages/Webcasts.aspx). |

||||||

|

The statutory text (5 U.S.C. §8348(j)(3)) governing the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund (CSRDF) states that Upon expiration of the debt issuance suspension period, the Secretary of the Treasury shall immediately issue to the Fund obligations under chapter 31 of title 31 that ... bear such interest rates and maturity dates as are necessary to ensure that, after such obligations are issued, the holdings of the Fund will replicate to the maximum extent practicable the obligations that would then be held by the Fund if the suspension of investment ... during such period had not occurred. The statutory text (5 U.S.C. §8909(c)) governing the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefit Fund (PSRHDF) states that investments "shall be made in the same manner" as those in the CSRDF. |

||||||

|

5 U.S.C. §8348(j)(5)(B). |

||||||

|