The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions

Changes from September 1, 2017 to February 23, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- 1. What is the BCA?

- 2. What components of the BCA currently affect the annual budget?

- Discretionary Spending Limits

- Annual Reductions to the Discretionary Spending Limits

- Annual Mandatory Spending Sequester

- 3. What is a sequester and when will it occur?

- 4. What statutory changes have been made to the BCA?

- 5. Is Congress bound by the BCA?

- 6. Which types of legislation are subject to the discretionary spending limits?

- Budget Resolutions

- Authorizations of Appropriations

- Regular, Supplemental, and Continuing Appropriations

- 7. Is some spending "exempt" or "excluded" from the BCA?

- 8. Is the sequester "returning" in

FY2018FY2020? - 9. How does the "parity principle" apply to the BCA?

- 10. How is discretionary spending currently affected by the BCA?

- Budgetary Impact

- 11. How is mandatory spending currently affected by the BCA?

- 12. Why do discretionary outlays differ from the spending limits established by the BCA?

- 13. How has

the federal budgetfederal spending changed since enactment of the - 14. How do modifications to the BCA affect baseline projections?

Summary

When there is concern with deficit or debt levels, Congress will sometimes implement budget enforcement mechanisms to mandate specific budgetary policies or fiscal outcomes. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25), which was signed into law on August 2, 2011, includes several such mechanisms.

The BCA as amended has three main components that currently affect the annual budget. One component imposes annual statutory discretionary spending limits for defense and nondefense spending. A second component requires annual reductions to the initial discretionary spending limits triggered by the absence of a deficit reduction agreement from a committee formed by the BCA. Third are annual automatic mandatory spending reductions triggered by the same absence of a deficit reduction agreement. Each of those components is described in further detail in this report. The discretionary spending limits (and annual reductions) are currently scheduled to remain in effect through FY2021, while the mandatory spending reductions are scheduled to remain in effect through FY2025FY2027.

Congress may modify or repeal any aspect of the BCA procedures, but such changes require the enactment of legislation. Several pieces of legislation have changed the spending limits or enforcement procedures included in the BCA with respect to each year from FY2013 through FY2017. These include the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA/; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013/; P.L. 113-67, also referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015/P.L. 114-74); P.L. 114-74), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123).

Those laws included changes to the discretionary limits imposed by the BCA that increased deficits in each year from FY2013-FY2017FY2019. No change has been enacted for FY2018FY2020 and beyond, so the discretionary spending limits for FY2018 throughFY2020 and FY2021 remain at the level prescribed by the BCA. TheFollowing enactment of BBA 2018, the discretionary caps in FY2018 are scheduled to be approximately $549629 billion for defense activities and $516579 billion for nondefense activities—slightly lowerhigher than the levels of $551 billion and $519 billion, respectively, in FY2017. Combined, the limits for FY2018 are $5138 billion lowerhigher than the FY2017 level.

This report addresses several frequently asked questions related to the BCA and the annual budget.

1. What is the BCA?

When there is concern with deficit or debt levels, Congress will sometimes implement budget enforcement mechanisms to mandate specific budgetary policies or fiscal outcomes. The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) was the legislative result of extended budget policy negotiations between congressional leaders and President Barack Obama. These negotiations occurred in conjunction with the government's borrowing authority approaching the statutory debt limit.1

Budget deficits in FY2009 through FY2011 averaged 9.0% of gross domestic product (GDP) and were higher than any other year since World War II. Those deficits were due to a number of factors, including reduced revenues and increased spending demands attributable to the Great Recession and costs associated with the economic stimulus package passed through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5).2

The BCA includes several interconnected components related to the federal budget, some of which are no longer in effect. There are five primary components:

- 1. An authorization to the executive branch to increase the debt limit in three installments, subject to a disapproval process by Congress. (Those provisions were temporary and are no longer in effect.)

- 2. A one-time requirement for Congress to vote on an amendment to the Constitution to require a balanced budget.3

- 3. The establishment of limits on defense discretionary spending and nondefense discretionary spending, enforced by sequestration (automatic, across-the-board reductions) in effect through FY2021.4 Under this mechanism, sequestration is intended to deter enactment of legislation violating the spending limits or, in the event that legislation is enacted violating these limits, to automatically reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in law.

- 4. The establishment of the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (often referred to as "the Joint Committee" or "the super committee"), which was directed to develop a proposal that would reduce the deficit by at least $1.5 trillion over FY2012 to FY2021.5

- 5. The establishment of an automatic process to reduce spending, beginning in 2013, in the event that Congress and the President did not enact a bill reported by the Joint Committee reducing the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion. (Such a bill was not enacted.) This automatic process requires annual downward adjustments of the discretionary spending limits, as well as a sequester (automatic, across-the-board reduction) of nonexempt mandatory spending programs. In this case, sequestration was included to encourage the Joint Committee to agree on deficit reduction legislation or, in the event that such agreement was not reached, to automatically reduce spending so that an equivalent budgetary goal would be achieved.

2. What components of the BCA currently affect the annual budget?

The BCA as amended has three main components that currently affect the annual budget. One component imposes annual statutory discretionary spending limits for defense and nondefense spending. A second component requires annual reductions to the initial discretionary spending limits, triggered by the absence of a deficit reduction agreement from the Joint Committee. Third are annual automatic mandatory spending reductions triggered by the same absence of a deficit reduction agreement. Each of those components is described in further detail below.

Discretionary Spending Limits

The BCA established statutory limits on discretionary spending for FY2012-FY2021.6 (Such discretionary spending limits were first in effect between FY1991 and FY2002.)7 There are currently separate annual limits for defense discretionary and nondefense discretionary spending.8 The defense category consists of discretionary spending in budget function 050 (national defense) only. The nondefense category includes discretionary spending in all other budget functions.

If discretionary appropriations are enacted that exceed a statutory limit for a fiscal year, across-the-board reductions (i.e., sequestration) of nonexempt budgetary resources within the applicable category are required to eliminate the excess spending. The BCA further stipulates that some spending is effectively exempt from the limits. Specifically, the BCA specifies that the enactment of certain discretionary spending—such as appropriations designated as emergency requirements or for overseas contingency operations—allows for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits (meaning that such spending is effectively exempt from the limits).9

Annual Reductions to the Discretionary Spending Limits

Another component of the BCA requires reductions to these discretionary spending limits annually. Due to the absence of the enactment of Joint Committee legislation to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion over the 10-year period (described above), the BCA requires these reductions to the statutory limits on both defense and nondefense discretionary spending for each year through FY2021.10

These reductions are often referred to as a sequester, but they are not a sequester per se because they do not make automatic, across-the-board cuts to programs. Instead, they lower the spending limits, allowing Congress the discretion to develop legislation within the reduced limits.

For information on the spending limit amounts, see the section below titled "10. How is discretionary spending currently affected by the BCA?"

Annual Mandatory Spending Sequester

Because legislation from the Joint Committee to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion over the 10-year period (described above) was not enacted, the BCA requires the annual sequester (automatic, across-the-board reductions) of nonexempt mandatory spending programs.11 This sequester was originally intended to occur each year through FY2021 but has been extended to continue through FY2025FY2027.12

Many programs are exempt from sequestration, such as Social Security, Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps). In addition, special rules govern the sequestration of certain programs, such as Medicare, which is limited to a 2% reduction.13 To see a list of direct spending programs included in the most recent sequester report, see the annual Office of Management and Budget (OMB) report to Congress on the Joint Committee sequester for FY2018.14

For more information on the budgetary impact of the mandatory spending sequester, see the section below titled How is mandatory spending currently affected by the BCA?

3. What is a sequester and when will it occur?

A sequester provides for the enforcement of budgetary limits established in law through the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending. This cancellation of spending makes largely across-the-board reductions to nonexempt programs, activities, and accounts. A sequester is implemented through a sequestration order issued by the President as required by law.

The purpose of a sequester is to enforce certain statutory budget requirements—either to discourage Congress from enacting legislation violating a specific budgetary goal or to encourage Congress to enact legislation that would fulfill a specific budgetary goal. One of the authors of the law that first employed the sequester recently stated, "It was never the objective ... to trigger the sequester; the objective ... was to have the threat of the sequester force compromise and action."15

As mentioned above, sequestration is currently used as the enforcement mechanism for policies established in the BCA:

- For the discretionary spending limits, a sequester will occur only if appropriations are enacted that exceed either the defense or nondefense discretionary limits. In such a case, sequestration is generally enforced when OMB issues a final sequestration report within 15 calendar days after the end of a session of Congress. In addition, a separate sequester may be triggered if the enactment of appropriations causes a breach in the discretionary limits during the second and third quarter of the fiscal year. In such an event, sequestration would take place 15 days after the enactment of the appropriation.16

- As mentioned above, the BCA requires reductions to these discretionary spending limits annually. These reductions are to be calculated by OMB and included annually in the OMB Sequestration Preview Report to the President and Congress, which is to be issued with the President's annual budget submission. The reductions would then apply to the discretionary spending limits for the budget year corresponding to the President's submission. While these reductions are often referred to as a sequester, they are not a sequester per se because they do not make automatic, across-the-board cuts to programs. Instead, they lower the spending limits, allowing Congress the discretion to develop legislation within the reduced limits.

- A sequester of nonexempt mandatory spending programs will take place each year through FY2025. These levels are also calculated by OMB and are included in the annual OMB report to Congress on the Joint Committee reductions, which is also to be issued with the President's budget submission. The sequester does not occur, however, until the beginning of the upcoming fiscal year.

4. What statutory changes have been made to the BCA?

Legislation has been enacted making changes to the spending limits or enforcement procedures included in the BCA for each year from FY2013 through FY2017. Some of the most significant of these changes are the following:

- The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240) postponed the start of FY2013 sequester from January 2 to March 3 and reduced the amount of the spending reductions by $24 billion, among other things.

- The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67, referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement) increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2014, each by about $22 billion. In addition, it increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2015, each by about $9 billion.17 It also extended the mandatory spending sequester by two years through FY2023. Soon after the enactment of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, a bill was enacted to "ensure that the reduced annual cost-of-living adjustment to the retired pay of members and former members of the armed forces under the age of 62 required by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 will not apply to members or former members who first became members prior to January 1, 2014, and for other purposes (P.L. 113-82)." This legislation extended the direct spending sequester by one year through FY2024.

- The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74) increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2016, each by $25 billion. In addition, it increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2017, each by $15 billion. It also extended the direct spending sequester by one year through FY2025. In addition, it established nonbinding spending targets for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT) levels for FY2016 and FY2017 and amended the limits of adjustments allowed under the discretionary spending limits for Program Integrity Initiatives.18

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123) increased nondefense and defense discretionary limits in FY2018 and FY2019. In FY2018 BBA 2018 increased the defense limit by $80 billion (to $629 billion) and increased the nondefense limit by $63 billion (to $579 billion); in FY2019 it increased the defense limit by $85 billion (to $647 billion) and increased the nondefense limit by $68 billion (to $597 billion). BBA 2018 also extended the mandatory spending sequester by two years through FY2027.5. Is Congress bound by the BCA?

Congress may modify or repeal any aspect of the BCA procedures at its discretion, but such changes require the enactment of legislation. Since enactment of the BCA, subsequent legislation has modified both the discretionary spending limits and the mandatory spending sequester (as described above).

In considering the potential for Congress to reach agreement on future modifications to the BCA, particularly the discretionary spending limits, it may be worth noting the following:

- Legislation that would modify the discretionary spending limit would be subject to the regular legislative process. Such legislation would therefore require House and Senate passage, as well as signature by the President or congressional override of a presidential veto. In the House, such legislation would require the support of a simple majority of Members voting, but in the Senate, consideration of such legislation would likely require cloture to be invoked, which requires a vote of three-fifths of all Senators (normally 60 votes) to bring debate to a close.

- Previous legislative increases to the discretionary spending limits have been coupled with future spending reductions, such as extensions of the mandatory spending sequester. For example, BBA 2013 extended the mandatory spending sequester by two years (from FY2021 to FY2023).19

- Previous legislative increases to the discretionary spending limits have adhered to what has been referred to as the "parity principle."20 In essence, this means that some Members of Congress have insisted that any legislation changing the limits must increase each of the two limits (defense and nondefense) by equal amounts. For example, BBA 2015 increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2016, each by $25 billion. In addition, it increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2017, each by $15 billion.21

6. Which types of legislation are subject to the discretionary spending limits?

Budget Resolutions

Although the budget resolution may act as a plan for the upcoming budget year, it does not provide budget authority and therefore cannot trigger a sequester for violation of the discretionary spending limits. Nevertheless, budget resolutions are often referred to in terms of complying with, or not complying with, the discretionary spending limits.22

Even if a budget resolution were agreed to that included planned levels of spending in excess of the discretionary spending limits, this would not supersede the discretionary spending limits stipulated by the BCA. While Congress may modify or cancel the discretionary spending limits at their discretion, such changes require the enactment of legislation.

Authorizations of Appropriations

Authorizations of discretionary appropriations, such as the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), do not provide budget authority and therefore cannot trigger a sequester for violation of the discretionary spending limits. Although authorizations often include recommendations for funding levels, budget authority is subsequently provided in appropriations legislation. It is, therefore, appropriations legislation that could trigger a sequester. Nevertheless, authorizations (the NDAA in particular) are often discussed in terms of whether or not the authorized level of funding, if appropriated, would comply with the discretionary spending limits.23

Even if an authorization bill were enacted that authorized appropriations at levels in excess of the discretionary spending limits, this authorization would not supersede the statutory discretionary spending limits stipulated by the BCA. While Congress may modify or cancel the discretionary spending limits at its discretion, such changes require the enactment of legislation.

Regular, Supplemental, and Continuing Appropriations

Appropriations legislation that provides budget authority for discretionary spending programs in excess of the discretionary spending limits can trigger a sequester for violation of the discretionary spending limits. This includes regular appropriations legislation, supplemental appropriations legislation, and continuing resolutions (CRs).24

Any appropriations legislation enacted into law that provides budget authority in excess of the levels stipulated by the BCA would trigger a sequester, canceling previously enacted spending through automatic, largely across-the-board reductions of nonexempt budgetary resources within the category of the breach.

Note that the statutory limits established by the BCA as amended apply to budget authority and not outlays. Budget authority is what federal agencies are legally permitted to obligate, and it is controlled by Congress through appropriation acts in the case of discretionary spending or through other acts in the case of mandatory spending. Budget authority gives federal officials the ability to spend. Outlays are disbursed federal funds. Until the federal government disburses funds to make payments, no outlays occur. Therefore, there is generally a lag between when Congress grants budget authority and when outlays occur.

7. Is some spending "exempt" or "excluded" from the BCA?

Some spending is regarded as "exempt" from the BCA. A distinction should be noted between categories of spending that are "excluded" from the discretionary spending limits and spending programs that are "exempt" from sequestration.

- Some categories of spending are considered "exempt" or "excluded" from the discretionary spending limits, meaning that when an assessment is made as to whether the discretionary spending limits have been breached, they are not counted. (In precise terms, the BCA does not "exempt" such spending but allows for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate such spending.)

For example, spending designated as emergency requirements or for OCO/GWOT is effectively excluded from the discretionary spending limits up to any amount (meaning that the designation of such spending allows for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate that spending).25 The BCA does not define what constitutes this type of funding, nor does it limit the level or amount of spending that may be designated as being for such purposes.

Similarly, "disaster funding" and spending for "continuing disability reviews and redeterminations" and "healthcare fraud and abuse control" are effectively exempt up to a certain amount (again meaning that such spending allows for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits to accommodate that spending).

- Some programs are exempt from a sequester, such as Social Security, Medicaid, CHIP, TANF, and SNAP. In addition, special rules govern the sequestration of certain programs, such as Medicare, which is limited to a 2% reduction. These exemptions and special rules are found in Sections 255 and 256 of the BBEDCA, as amended, respectively.

It may also be helpful to review OMB sequester reports detailing programs that have been subject to sequester. To see a list of both discretionary and direct spending programs subject to the FY2013 sequester, see the OMB report to Congress on the Joint Committee sequestration for FY2013.26 To see a list of direct spending programs included in the most recent sequester report, see the annual OMB report to Congress on the Joint Committee sequester for FY2018.27

8. Is the sequester "returning" in FY2018FY2020?

Sometimes Members of Congress, the Administration, and the press discuss the concept of the sequester "returning in FY2018."28 Generally, the term return is being used to describe the fact that beginning in FY2018at some point, the discretionary spending limits will again be the level prescribed by the BCA. As mentioned above, since the BCA was enacted, other legislation has been enacted to increase the discretionary spending limits.29 The BBA 2013 increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2014 and FY2015, and the BBA 2015 increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2016 and FY2017, and the BBA 2018 increased discretionary spending limits for both defense and nondefense for FY2018 and FY2019. No similar increase has been enacted for FY2018 and beyondFY2020 and FY2021. The statement that the "sequester is returning in FY2018FY2020," therefore, means that the discretionary spending limits will again be the level prescribed by the BCA, as described in the section below.

9. How does the "parity principle" apply to the BCA?

The "parity principle" refers to the equality between changes made to defense and nondefense budget authority through the deficit reduction measures established by the BCA. While there has never been a statutory requirement to uphold the parity principle, budget parity has followed from deficit reduction measures imposed by the BCA and each amendment to its deficit reduction measures. However, the specific type of parity in each law has evolved over time.

The BCA and ATRA reflected parity in the budgetary impact of changes to defense and nondefense budget authority across both discretionary and mandatory spending categories. Subsequent BCA amendments in BBA 2013 and BBA 2015 reflected parity between defense and nondefense budget authority for discretionary spending only, as those laws also extended automatic mandatory deficit reduction measures that had larger budget reductions for nondefense activities than for defense programs. Finally, theBBA 2018 reflected yet another type of parity, as the amended discretionary cap levels in FY2018 and FY2019 were increased by an equivalent amount relative to the initial BCA levels as established in August 2011. As compared with the caps after the automatic reductions took effect, BBA 2018 included larger increases to the defense caps than to the nondefense caps. As with BBA 2013 and BBA 2015, BBA 2018 also included an extension to the automatic mandatory spending reductions with a larger set of reductions for nondefense programs than for defense programs.

The BCA provides for upward adjustments to the discretionary caps, sometimes called spending "outside the caps," for budget authority devoted to OCO, emergency requirements, and other purposes.30 Budget authority for BCA upward adjustments has not reflected parity between defense and nondefense activities in any effective year of the BCA to date, as upward adjustments have allowed for more defense spending than nondefense spending in each year from FY2012 through FY2017.

For more information on the parity principle and the BCA, see CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by [author name scrubbed].

10. How is discretionary spending currently affected by the BCA?

The BCA includes annual statutory caps that limit how much discretionary budget authority can be provided for defense and nondefense activities. These limits are in effect through FY2021 and are enforced by sequestration, meaning that a breach of the discretionary spending limit for either category would trigger a sequester of resources within that category only to make up for the amount of the breach.

A second component of the BCA makes automatic decreases to these caps annually. In the absence of the enactment of a Joint Committee bill to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion, the BCA required downward adjustments (or reductions) to the statutory limit on both defense and nondefense spending each year through FY2021. While these reductions are often referred to as sequesters, they are not technically sequesters because they do not make automatic, across-the-board cuts to programs. The reductions instead lower the spending limits, allowing Congress the discretion to develop legislation within the reduced limits. These reductions are to be calculated annually by OMB and are included in the OMB Sequestration Preview Report to the President and Congress, which is issued with the President's annual budget submission.

The BCA stipulates that certain discretionary funding, such as appropriations designated as OCO or for emergency requirements, allows for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits. OCO funding is therefore sometimes described as being "exempt" from the discretionary spending limits.31 The BCA does not define what constitutes this type of funding, nor does it limit the level of spending that may be designated as being for such purposes.

Budgetary Impact

The BCA as enacted was estimated to reduce budget deficits by a cumulative amount of roughly $2 trillion over the FY2012-FY2021 period. Subsequent modifications enacted through ATRA, BBA 2013, and BBA 2015 lessened the level of deficit reduction projected to be achieved by the BCA in selected years. ATRA reduced the BCA's deficit effect through the postponement and decreases of spending reductions in FY2013, while BBA 2013, BBA 2015, and BBA 20152018 limited the deficit-reducing impact through increases in the discretionary budget authority caps in FY2014-FY2015 and FY2016-FY2017FY2019.

Table 1 shows the evolution of discretionary spending limits established by the BCA from August 2011 to August 2017through February 2018. The discretionary caps in FY2018 are currently scheduled to be $549629 billion for defense activities and $516579 billion for nondefense activities, slightly lowerhigher than their totals of $551 billion and $519 billion, respectively, in FY2017. The combined discretionary limit in FY2018 ($1,065208 billion) is $5138 billion lower than its FY2017 value.

Table 1. Discretionary Budget Authority Limits Under the BCA as Amended, August 2011-Present

(in billions of nominal dollars)

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|||

|

BCA |

Aug. 2011 |

Defense |

555 |

546 |

556 |

566 |

577 |

590 |

603 |

616 |

630 |

644 |

|

Nonde-fense |

507 |

501 |

510 |

520 |

530 |

541 |

553 |

566 |

578 |

590 |

||

|

Auto. Enforce-ment |

Jan. 2012 |

Defense |

555 |

492 |

501 |

511 |

522 |

535 |

548 |

561 |

575 |

589 |

|

Nonde-fense |

507 |

458 |

472 |

483 |

493 |

505 |

517 |

531 |

545 |

557 |

||

|

ATRA |

Jan. 2013 |

Defense |

555 |

518 |

497 |

511 |

522 |

535 |

548 |

561 |

575 |

589 |

|

Nonde-fense |

507 |

484 |

469 |

483 |

494 |

505 |

518 |

532 |

545 |

558 |

||

|

BBA 2013 |

Dec. 2013 |

Defense |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Nonde-fense |

507 |

484 |

492 |

492 |

493 |

504 |

516 |

530 |

543 |

556 |

||

|

BBA 2015 |

Nov. 2015 |

Defense |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548 |

551 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Nonde-fense |

507 |

484 |

492 |

492 |

518 |

519 |

516 |

530 |

543 |

555 |

||

|

Current |

Aug. 2017 |

Defense |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548 |

551 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

591 |

|

Nonde-fense |

507 |

484 |

492 |

492 |

518 |

519 |

516 |

529 |

542 |

555 |

Sources: CBO, letter to the Honorable John A. Boehner and Honorable Harry Reid estimating the impact on the deficit of the Budget Control Act of 2011, August 2011; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2012, January 2012; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2013, March 2013; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2014, January 2014; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2016, December 2015; CBO, Sequestration Update Report: August 2017, August 2017; CBO, Cost Estimate for Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, February 2018.

Notes: Spending limits apply to fiscal years. Bold figures indicate statutory changes. The BCA as amended provided for "Security" and "Nonsecurity" categories in FY2012 and FY2013: italicized figures denote CRS estimates of budget authority for defense and nondefense categories in those years. Small changes in FY2016-FY2021 budget authority shown in ATRA, BBA 2013, and BBA 2015 rows are caused by adjustments in the annual proportional allocations of automatic enforcement measures as calculated by OMB: for more information on these adjustments, see CBO, Estimated Impact of Automatic Budget Enforcement Procedures Specified in the Budget Control Act, September 2011.

11. How is mandatory spending currently affected by the BCA?

The absence of an agreement by the Joint Committee triggered automatic spending reductions (as provided for in the BCA) for all mandatory programs that were not explicitly exempted from FY2013 through FY2021. Notably, Social Security payments were exempted from the automatic reductions, and the effect on Medicare spending was limited to 2% of annual payments made to certain Medicare programs. Extensions of the mandatory spending reductions were included in BBA 2013, BBA 2015, and BBA 20152018 and are currently scheduled to remain in place through FY2025FY2027. A recent OMB sequestration report estimated that such measures wouldwill reduce mandatory outlays by $18.14 billion in FY2018, with $17.42 billion of that total applied to nondefense programs and $0.72 billion applied to defense programs.32

12. Why do discretionary outlays differ from the spending limits established by the BCA?

The limits on discretionary spending established by the BCA apply to budget authority, which is the amount that federal agencies are legally permitted to obligate. Outlays, meanwhile, are disbursed federal funds: In other words, they represent amounts that are actually spent by the government. There is generally a lag between when Congress grants budget authority and when outlays occur, and that lag can vary depending on the agency and specific purpose of the obligation.33 Furthermore, the budget may classify certain types of spending in a certain way when measuring budget authority and another way when measuring outlays. For example, much of the spending attached to the Highway Trust Fund is classified as mandatory spending when measuring budget authority and as discretionary spending when measuring outlays.34

13. How has the federal budgetfederal spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

BCA?

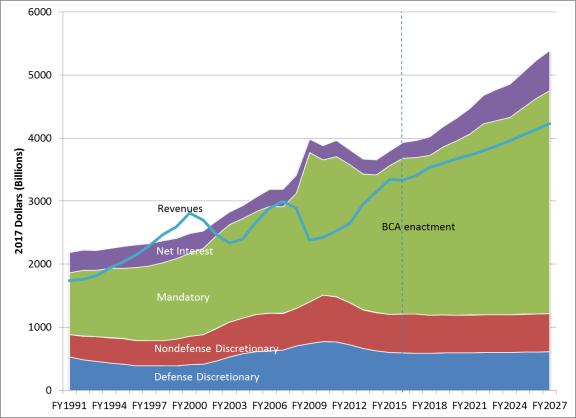

Real deficits have declined since FY2011, due to the modifications made by the BCA, increased revenues, and the winding down of stimulus programs. However, the FY2017 deficit (3.5% of GDP, or $665 billion) remains higher than the average deficit since FY1947 (2.0% of GDP), and the CBO baseline projects that real budget deficits will increase in future years. Figure 1 shows federal budget outcomes in inflation-adjusted dollars from FY1991 through FY2027, the final year that the caps on discretionary budget authority established by the BCA are in effect. Budget deficits declined for much of the 1990s due to decreased spending, rising revenues, and an improved economy. The federal budget recorded surpluses from FY1998 through FY2001. Prior to that, the last budget surplus occurred in FY1969. Budget deficits returned starting in FY2002 and slowly increased over the next several years due to reduced revenues and increased spending. Net deficits peaked during the Great Recession from FY2009 to FY2011, as negative and low economic growth coupled with increased spending commitments provided for by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (P.L. 111-5) contributed to real deficits averaging 9.0% of gross domestic product (GDP) in those years.

deficits averaging $1,492 billion in those years.

Budget deficits declined from FY2012 through FY2016. The modifications made by the BCA, increased revenues, and the winding down of stimulus programs all contributed to such declines. Though declining, the average deficits in those years ($690 billion) still exceeded the average budget deficit of the period from FY1962 to FY2016 ($308 billion). The January 2017 CBO baseline projects that real budget deficits will increase from $559 billion in FY2017 to $739 billion in FY2021.

|

Budgetary Resources |

BCA Spending Reductions |

|

|

Defense Discretionary |

|

49% |

|

Nondefense Discretionary |

|

|

|

Defense Mandatory |

2% |

1% |

|

Medicare (Nondefense Mandatory) |

|

|

|

Other Nondefense Mandatory |

|

|

Source: OMB, OMB Report to Congress on the Joint Committee Reductions for Fiscal Year 20162017, February 20152016; and CBO, An Update to The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, JanuaryJune 2017.

Notes: Mandatory spending is measured on a gross basis (i.e., offsetting receipts are not netted out). The table does not include spending devoted to net interest payments.

The budgetary measures enacted by the BCA have distinct effects on various types of federal activity. Table 2 illustrates the division of total budgetary resources in FY2016 across major spending categories along with the effects of automatic spending reductions from the BCA in that year. Mandatory programs account for roughly two-thirds of FY2016 outlays (excluding net interest payments). The remaining 35% of total spending is discretionary and is split almost evenly between defense and nondefense expenditures (17% of total spending each). Meanwhile, the automatic spending cuts fall most heavily on discretionary programs. In FY2016, discretionary spending is projected to account for 35% of budgetary resources and 69% of the automatic spending reductions. Defense discretionary spending is particularly affected, as the defense spending category received 49% of all automatic cuts but accounts for 17% of total gross budgetary resources. Across mandatory and defense categories FY2016 automatic spending cuts are equally applied to defense and nondefense programs. The BCA as amended does not directly affect the revenue side of the federal budget.

14. How do modifications to the BCA affect baseline projections?

Modifications to the limits on discretionary spending, established by the BCA, change authorizations levels, which in turn affect outlays. Legislation that instead affects mandatory spending (or spending controlled by laws other than appropriations acts) is known as direct spending. CBO provides estimates of both discretionary spending effects and direct spending effects in its legislative cost estimates. Whether proposed legislation affects discretionary or mandatory spending may have ramifications for congressional budgetary enforcement procedures, however.

CBO's baseline projections assume that the discretionary limits imposed by the BCA as amended will proceed as scheduled through FY2021 and that subsequent discretionary spending levels will grow with the economy in subsequent years.35 Such methodology uses the discretionary spending levels in FY2021 as the basis for discretionary spending projections for the remainder of the budget window. Therefore, new proposals that would modify discretionary spending limits in one or more of FY2018-FY2020 would generate budget effects only in those yearsthat year, whereas proposals that would modify FY2021 limits would generate budget effects in FY2021 and each remaining year of the 10-year baseline window.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

A statutory increase had been enacted roughly once per year since its creation in 1917. For more information, see CRS Report RL31967, The Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

The Great Recession describes the contractionary period (which lasted from December 2007 to June 2009) and subsequent recovery of the U.S. economy. |

| 3. |

The House and Senate each voted on such an amendment. The Senate rejected two balanced budget amendments, while the House failed to achieve the necessary two-thirds vote needed for passage. |

| 4. |

The statutory limits currently included in the BCA are described in statute as security and nonsecurity. Currently, the security category is defined to include discretionary appropriations classified as budget function 050 (national defense) only, and the nonsecurity category is defined to include all other discretionary appropriations. Originally, however, the BCA caps defined the security category to include discretionary spending for the Departments of Defense, Homeland Security, and Veterans Affairs; the National Nuclear Security Administration; the intelligence community management account; and all accounts in the international affairs budget function (budget function 150) and defined the nonsecurity category to include discretionary spending in all other budget accounts. This change in category definitions occurred automatically under the BCA as part of the automatic spending reduction process that resulted from the lack of enactment of a bill reported by the Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction. |

| 5. |

While the committee was tasked with reporting legislation that would reduce the deficit by $1.5 trillion over the period of FY2012-FY2021, the automatic process to reduce spending was designed to be triggered only if legislation reported by the committee reducing the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion was not enacted. |

| 6. |

Discretionary spending is controlled through the appropriations process and is generally provided annually. The appropriations committees have jurisdiction over discretionary spending programs, while authorizing committees have jurisdiction over mandatory (or direct) spending programs. For more information see CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] |

| 7. |

The spending limits were part of the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 (BEA; P.L. 101-508). For more information, see CRS Report R41901, Statutory Budget Controls in Effect Between 1985 and 2002, by [author name scrubbed]. During the period of FY1991-FY2002, separate caps existed and varied by year. The concept of capping defense and nondefense spending separately was discussed as early as 1984 and is often cited as "the rose garden proposal." Senator Howard Baker, Senate debate, Congressional Record, April 24, 1984, p. 9681. |

| 8. |

Ibid., footnote 4. |

| 9. |

For more information, see section below titled Are some spending programs "exempt" from the BCA? |

| 10. |

The BCA established the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, directed to develop a proposal that would reduce the deficit by at least $1.5 trillion over FY2012 to FY2021. The BCA also established an automatic process to produce additional savings, beginning in 2013, in the event that a bill reported by the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction reducing the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion was not enacted by January 15, 2012. (Such a bill was not enacted.) This automatic process requires annual downward adjustments of the discretionary spending limits, as well as a sequester of nonexempt mandatory spending programs. |

| 11. |

Ibid. |

| 12. |

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-67, also referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement) extended the mandatory spending sequester by two years to FY2023. Soon after the enactment of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, a bill was enacted to "ensure that the reduced annual cost-of-living adjustment to the retired pay of members and former members of the armed forces under the age of 62 required by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 will not apply to members or former members who first became members prior to January 1, 2014, and for other purposes (P.L. 113-82)." This legislation extended the mandatory spending sequester by one year to FY2024. BBA 2015 (P.L. 114-74) extended the mandatory spending sequester by one year to FY2025. BBA 2018 (P.L. 115-123) further extended the mandatory spending sequester by an additional two years through FY2027. For more information, see CRS Report |

| 13. |

These exemptions and special rules are found in Sections 255 and 256 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (BBEDCA, Title II of P.L. 99-177), commonly known as the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act. For more information, see CRS Report R42050, Budget "Sequestration" and Selected Program Exemptions and Special Rules, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 14. |

OMB, OMB Report to the Congress on the Joint Committee Reductions for Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2018_jc_sequestration_report_may2017_potus.pdf. |

| 15. |

Oral and written testimony of the Honorable Phil Gramm, former Member of the House of Representatives from 1979 to 1985 and U.S. Senator from 1985 to 2002, before the Senate Finance Committee at the hearing on Budget Enforcement Mechanisms, May 4, 2011, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/050411pgtest.pdf. The law referred to is BBEDCA (P.L. 99-177). For more information on sequestration, see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. Sequestration was first used as an enforcement mechanism in BBEDCA (referenced above). For more information on the use of sequestration in BBEDCA and the BEA, see CRS Report R41901, Statutory Budget Controls in Effect Between 1985 and 2002, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 16. |

If the enactment of appropriations causes the discretionary spending limits to be breached in the last quarter of the fiscal year, the spending limit for the following fiscal year for that category must be reduced by the amount of the breach. |

| 17. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43535, Provisions in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 as an Alternative to a Traditional Budget Resolution, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 18. |

For more information, see out of print CRS Insight IN10389, Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015: Adjustments to the Budget Control Act of 2011, by [author name scrubbed], available to congressional staff upon request. |

| 19. |

For more information on the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates related to legislative changes to the discretionary limits, see CBO, "Frequently Asked Questions About CBO Cost Estimate," https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/ce-faq. |

| 20. |

Democratic Policy and Communications Center, "In Wake of Partisan Maneuvers to Break Budget Agreement, Senate Dem Leaders Urge GOP to Publicly Agree to Honor Core Tenets of Last Year's Bipartisan Budget Agreement to Allow Appropriations Process to Move Forward," press release, July 7, 2016, https://www.dpcc.senate.gov/?p=issue&id=594; and U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations, "Mikulski Floor Statement on Reed-Mikulski Amendment," press release, June 8, 2016, http://www.appropriations.senate.gov/news/minority/mikulski-floor-statement-on-reed-mikulski-amendment. |

| 21. |

For more information on the parity principle, see the section below titled How does the "parity principle" apply to the BCA? |

| 22. |

While it cannot trigger a sequester, a budget resolution may be subject to a point of order in the Senate created to enforce the discretionary limits. For more information on the budget resolution and discretionary spending limits, including possible points of order against a budget resolution that provides for spending in excess of the discretionary spending limits, see CRS In Focus IF10647, The Budget Resolution and the Budget Control Act's Discretionary Spending Limits, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 23. |

While it cannot trigger a sequester, an authorization bill may be subject to a point of order created to enforce the discretionary limits. If an authorization bill were to authorize appropriations at levels that would breach the BCA limits, such as an amount for the defense function (050) that is higher than the spending limit for FY2018, its consideration might be subject to a point of order in the Senate under Section 312(b), which prohibits consideration in the Senate of any bill, resolution, amendment, motion, or conference report that would exceed the discretionary spending limits. (No corresponding point of order exists in the House.) It may be worth noting that the NDAA includes only the authorizations of appropriations within the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, which does not reflect all of the authorizations of appropriations within the national defense budget function (050). If such a point of order were raised, further consideration of the budget resolution might not be in order unless the point of order was waived by a vote of three-fifths of all Senators. |

| 24. |

Consideration of legislation that would provide spending in excess of the spending limits would be subject to a point or order. For example, if an appropriations bill were to provide appropriations at levels that would breach the discretionary spending limits, such as an amount for the defense function (050) that is higher than the spending limit for FY2018, its consideration would be subject to a 312(b) point of order in the Senate as well as a 314(f) point of order in either the House or the Senate. If either of those points of order were raised and sustained, further consideration of the appropriations measure would not be in order, unless the point of order was waived by a vote of three-fifths of all Senators in the Senate or in the House by a simple majority of those Members voting. For more information on those points of order, see CRS Report 97-865, Points of Order in the Congressional Budget Process, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 25. |

These adjustments are specified in Section 251(b)(2) [2 U.S.C. §901(b)(2)]. Spending designated as "emergency" or for OCO/GWOT must be designated on an account-by-account basis and must be subsequently designated so by the President. |

| 26. |

This was the last time that discretionary programs were subject to a sequester. OMB, OMB Report to the Congress on the Joint Committee Sequestration for Fiscal Year 2013, March 1, 2013, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/fy13ombjcsequestrationreport.pdf. |

| 27. |

OMB, OMB Report to the Congress on the Joint Committee Sequestration for Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2018_jc_sequestration_report_may2017_potus.pdf. |

| 28. |

For example, a press report on budget cuts related to defense stated, "Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Joseph Dunford, in an exchange with Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said a return to sequestration would require a rewrite of the US national defense strategy and expose the nation to "significant risk," from Russia, China, Iran, North Korea and violent extremism, Dunford said. 'My immediate response, senator, is we would have to revise the defense strategy, if we go back to sequestration; We would not be able to do what we do right now," Dunford said.'" Joe Gould, "Sequestration Budget Cuts Pose 'Greatest Risk' to DoD," DefenseNews, March 17, 2016, http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/2016/03/17/sequestration-budget-cuts-pose-greatest-risk-dod/81924766/. |

| 29. |

In the section titled Have statutory changes been made to the BCA? |

| 30. |

For more information, see the section above titled Are any spending programs "exempt" or "excluded" from the BCA? |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

OMB, "OMB Report to the Congress on the Joint Committee Reduction for Fiscal Year 2018." |

| 33. |

See section titled Which types of legislation are subject to the discretionary spending limits? |

| 34. |

For more information on the budgetary treatment of the Highway Trust Fund, see CBO, The Highway Trust Fund and the Treatment of Surface Transportation Programs in the Federal Budget, June 2014, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/45416-TransportationScoring.pdf. |

| 35. |

This methodology is consistent with Section 257 of the Deficit Control Act. For more information, see CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 2017, p. 26. |