Women in Congress: Statistics and Brief Overview

Changes from July 12, 2017 to May 8, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Women in Congress:

Summary Statistics and Brief Overview

Contents

- Introduction

- How Women Enter Congress: Regular Elections, Special Elections, and Appointments

- Women in Congress as Compared with Women in Other Legislative Bodies

- International Perspective

- State-House Perspective

- Female Election Firsts in Congress

- Records for Length of Service

- Women Who Have Served in Both Houses

- African American Women in Congress

- Asian Pacific American Women in Congress

- Hispanic Women in Congress

- Women Who Have Served in Party Leadership Positions

- Women and Leadership of Congressional Committees

- Assessing the Effect of Women in Congress

- Legislative Behavior

- Legislative Effectiveness

- Impact of Women on Policy and Congress

Figures

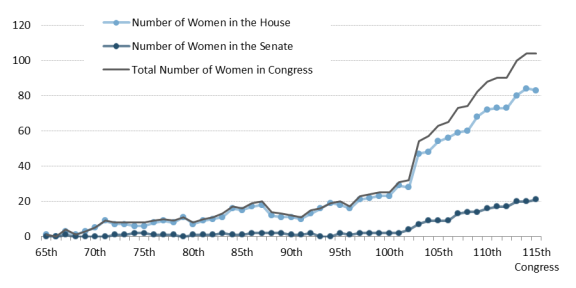

- Figure 1. Number of Women by Congress: 1917-2017

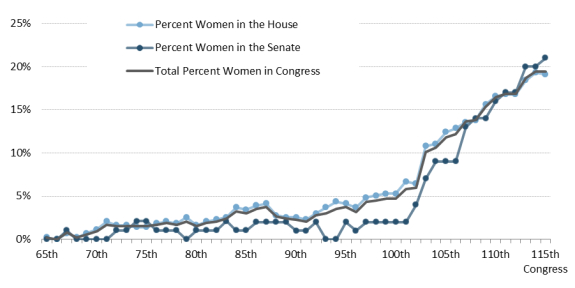

- Figure 2. Percentage of Women by Congress: 1917-2017

- Figure 3. Women as

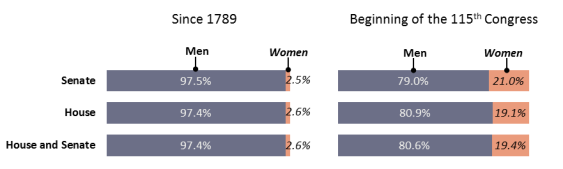

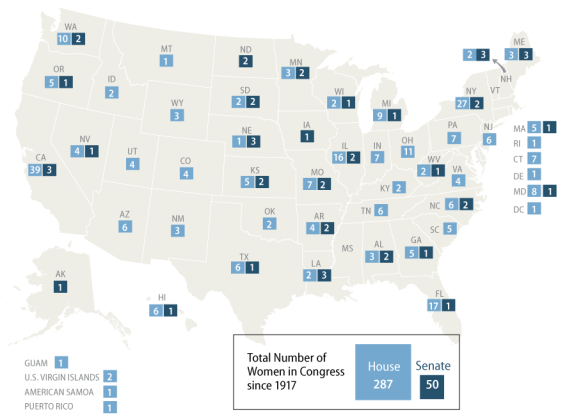

Percenta Percentage of Total Members Since 1789 and in the 115th Congress - Figure 4. Number of Women in the House and Senate by State, District, or Territory, 1917-Present

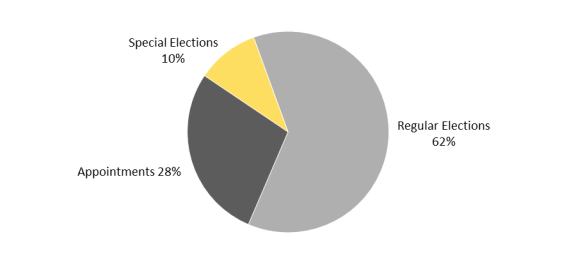

- Figure 5. Women's Initial Entrance to the Senate: Regular Elections, Special Elections, and Appointments to Unexpired Terms

- Figure 6. Women in Congress and State Legislatures: 1971-2017

Tables

- Table 1. Women Members of Congress: Summary Statistics, 1917-Present

- Table 2. Number of Women Members of the 115th Congress

- Table 3.

- Table 4.

- Table 5. Hispanic Women in the 115th Congress

- Table 6. Selected Congressional Party Leadership Positions Held by Women

- Table 7. Committees Chaired by Women, 115th Congress

- Table A-1. Congressional Service by Women: By Type and by Congress, 1917-

20172018

Summary

A record 110111 women currently serve in the 115th Congress: 8988 in the House (including Delegates and the Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico; 6564 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 2123 in the Senate (1617 Democrats and 56 Republicans). This passedsurpasses the previous record from the 114th Congress (108 women initially sworn in, and 1 House Member subsequently elected).

The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. Hattie Caraway (D-AR, 1931-1945) was the first Senator to succeed her husband and the first woman elected to a six-year Senate term.

A total of 326328 women have been elected or appointed to Congress, including 211212 Democrats and 114116 Republicans. Republicans. Of these women,

276 (178 Democrats, 98 Republicans) women have been elected only in the House of Representatives.These figures include six nonvoting Delegates (one each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and American Samoa and two from the U.S. Virgin Islands), as well as one Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico;38 (24 Democrats, 14. Of these,- 276 (178 Democrats, 98 Republicans) women have been elected only to the House of Representatives.

40 (25 Democrats, 15 Republicans) women have been elected or appointed onlyinto the Senate;- 12 (9 Democrats, 3 Republicans) women have served in both houses;

and a total of41 African American women have served in Congress (2 in the Senate, 39 in the House), including 21 serving in the 115th Congress. Thirteen Hispanic women have been elected to the House, and one to the Senate; 11 serve in the 115thCongress. Thirteen; 13 Asian Pacific American women have served in Congress (10 in the House, 1 in the Senate, and 2 in both the House and Senate), including 11 in the 115th Congress.

; and

threetwo women currently chair House committees (an additional female chair stepped down), one woman chairs a Senate standing committee, and one woman chairs a Senate select committee.

This report includes a discussion of the impact of women in Congress as well as historical information, including the number and percentage of women in Congress over time, means of entry to Congress, comparisons to international and state legislatures, records for tenure, firsts for women in Congress, women in leadership, and African American, Asian Pacific American, and Hispanic women in Congress, as well as a brief overview of research questions related to the role and impact of women in Congress. Table A-1 in the Appendix provides details on the total number of women who have served in each Congress, including information on changes within a Congress. The report may reflect data at the beginning or end of each Congress, or changes during a Congress. See the notes throughout the report for information on the currency and coverage of the data.

For additional biographical information—including the names, committee assignments, dates of service, listings by Congress and state, and (for Representatives) congressional districts of the 326328 women who have been elected or appointed to Congress—see CRS Report RL30261, Women in Congress, 1917-2017: Biographical2018: Service Dates and Committee Assignment Information, and ListingsAssignments by Member, and Lists by State and Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Introduction

A total of 326328 women have been elected or appointed to the U.S. Congress. The first woman, Jeannette Rankin (R-MT), was elected on November 9, 1916, to the 65th65th Congress (1917-March 4, 1919).

Table 1 details this service by women in the House, Senate, and both chambers.1

Table 1. Women Members of Congress: Summary Statistics, 1917-Present

(inclusive through April 13, 2018)

|

Total |

Senate Service |

House |

House |

House Service Only (Subtotal) |

Women who have Served in Both Chambers |

|

|

Total |

|

38 |

269 |

7a |

276a |

12 |

|

Democrats |

211 |

24 |

174 |

4 |

178 |

9 |

|

Republicans |

115 |

14 |

95 |

3 |

98 |

3 |

Source: U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian and Office of Art and Archives, "Women in Congress," http://history.house.gov/Exhibition-and-Publications/WIC/Women-in-Congress.

Notes: The House and Senate totals each include one woman who was elected but never sworn in.

a.

The total number of female Members of the House includes one Delegate to the House of Representatives from Hawaii prior to statehood, one from the District of Columbia, one from Guam, one from American Samoa, and two from the U.S. Virgin Islands as well as one Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico.

In theThe 115th Congress, 110 women serve, as detailed in Table 2.

- women account for 19.8% of voting Members in the House and Senate (106 of 535);

- women account for 20.5% of total Members in the House and Senate (111 of 541, including the Delegates and Resident Commissioner);

- women account for 19.1% of voting Representatives in the House (83 of 435); and

- women account for 19.9% of total Members in the House (88 of 441, including the Delegates and Resident Commissioner).

|

Total |

Senators |

Representatives |

Nonvoting Members (Delegates and Resident Commissioner) |

House Subtotal (Representatives and Nonvoting Members) |

|

|

Total |

|

23 |

84 |

5 |

(20.2% of total Members) |

|

Democrats |

81 |

16 |

62 |

3 |

65 |

|

Republicans |

29 |

5 |

22 |

2 |

24 |

Source: U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian and Office of Art and Archives, "Women in Congress," http://history.house.gov/Exhibition-and-Publications/WIC/Women-in-Congress.

Notes: The 115th Congress began with 109 women Members in the House and Senate. One woman was subsequently elected to the House in June 2017, one woman was appointed to the Senate in December 2017, one woman in the House died in March 2018, and another woman was appointed to the Senate and took the oath of office in April 2018. Four of the women who serve in the House are Delegates, representing the District of Columbia, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa. One woman serves as the Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico. Information in this table is current as of the date of the report.

This report includes a discussion of the impact of women in Congress as well as historical information, including the (1) number and percentpercentage of women in Congress over time; (2) means of entry to Congress; (3) comparisons to international and state legislatures; (4) records for tenure; (5) firsts for women in Congress; (6) African American, Asian Pacific, and Hispanic American women in Congress; and (7) women in leadership.

For additional biographical information—including the names, committee assignments, dates of service, listings by Congress and state, and (for Representatives) congressional districts of the women who have served in Congress—see CRS Report RL30261, Women in Congress, 1917-2017: Biographical2018: Service Dates and Committee Assignment Information, and ListingsAssignments by Member, and Lists by State and Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Since the 65th Congress (1917-1918), the number of women serving in Congress has increased incrementally, and on a few occasions decreased. The largest increase occurred in the 103rd Congress (1993-1994), when the total number of women in the House and Senate serving at one time rose from 32 in the 102nd Congress to 54, an increase of nearly 69%. The 1992 election came to be known popularly as the "Year of the Woman" due to the large electoral increase of women in Congress.2

Figure 1 charts the changes in the number of women serving in Congress. For a table showing the total number of women who have served in each Congress, including information on turnover within a Congress, please see Table A-1 in the Appendix.

Figure 2 shows the percentage of women in the House, Senate, and total each Congress since the first woman was elected in 1917 (not including nonvoting Members). Figure 3 shows that from the 1st Congress (1789) through the beginning of the 115th Congress (2017), women number

- 50 (2.54%) of the total 1,970 current and former Senators;

- 281 (2.57%) of the 10,940 current and former Representatives (including those who served in both chambers but not including Delegates or Resident Commissioners); and

- 319 (2.61%) of the 12,238 total persons who have served in Congress (not including Delegates or Resident Commissioners).

|

Figure 3. Women as Numbers for the 115th Congress are for the beginning of the Congress |

|

|

Source: Senate Historical Office, Senators of the United States, 1789-present, available at http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/chronlist.pdf; and House of Representatives, Total Members of the House and State Representation, Last Updated January 3, 2017, http://history.house.gov/Institution/Total-Members/Total-Members/. This information is updated once per Congress. Notes: The House and Senate totals each include one woman who was elected but never sworn in. Delegates and the Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico are not included in the data. |

As seen in Figure 4, 4849 states (all except Mississippi and Vermont3),Vermont),3 4 territories (American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and the District of Columbia have been represented by a woman in Congress at some time since 1917.4

Five states (Washington with 10, Ohio with 11, Illinois with 16, Florida with 17, New York with 27, and California with 39) have elected 10 or more women to the House of Representatives, and 5 states (Alaska, Iowa, Mississippi, North Dakota, and Vermont) have elected none.

ThirteenFourteen states have been represented by one female Senator, 1110 have sent 2two, and 56 states have sent 3three. Twenty-one states have never been represented by a female Senator.

|

|

Notes: Numbers include Delegates and reflect the beginning of the 115th Congress. The 12 women who have served in both the House and Senate are counted in each tally. One woman from South Carolina (House) and one woman from South Dakota (Senate) were elected but never sworn in due to the House or Senate being out of session. |

states have never been represented by a female Senator. How Women Enter Congress: Regular Elections, Special Elections, and Appointments

Pursuant to Article I, Section 2, clause 4 of the U.S. Constitution, all Representatives enter office through election, even those who enter after a seat becomes open during a Congress.5 By contrast, the Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution, which was ratified on April 8, 1913, gives state legislatures the option to empower governors to fill Senate vacancies by temporary appointment.6

The 5052 women who have served in the Senate entered initially through three different routes:

- 31 entered through regularly scheduled elections,

1416 were appointed to unexpired terms, and- 5 were elected by special election.7

As Figure 5 shows, approximately 7269% of all women who have served in the Senate initially entered Senate service by winning an election (regular or special). Approximately 2831% of women entered the Senate initially through an appointment.

Of the 1416 women who were appointed to the Senate, 4 have served more than one year, with 3 of those women serving in more than one Congress. Half of the appointed female Senators subsequently did not seek election. Two were defeated for their party nomination, one was defeated in a general election, one was elected in a special election for the remainder of the term but was not a candidate for a full term, and three were elected to full terms.

Since the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1913, nine years prior to the first appointment of a woman to fill a Senate vacancy, 195198 Senators have been appointed.8 Of these appointees, 93% (18192% (182) have been men, and 7% (148% (16) were women.9

|

Figure 5. Women's Initial Entrance to the Senate: Regular Elections, Special Elections, and Appointments to Unexpired Terms Inclusive through April 13, 2018 |

|

|

Source: Figure compiled by CRS based on descriptions in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (http://bioguide.congress.gov/biosearch/biosearch.asp). |

Women in Congress as Compared with Women in Other Legislative Bodies

International Perspective

The current total percentage of voting female representation in Congress (19.68%) is slightly lower than averages of female representation in other countries. According to the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), as of January 1, 2017, women represented 23.3% of national legislative seats (both houses) across the entire world. In the IPU database of worldwide female representation, the United States ranks 104th worldwide for women in the lower chamber. The Nordic countries (Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Denmark, and Norway) lead the world regionally with 41.7% female representation in national legislatures.10 Rwanda and Bolivia have the only national legislatures in the world with a majority of women holding seats in the lower (or only) chamber.11

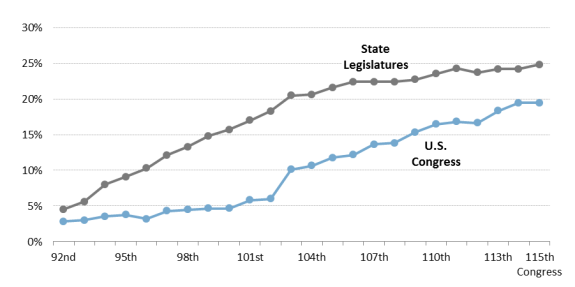

State-House Perspective

The percentage of women in Congress also is lower than the percentage of women holding seats in state legislatures. According to the Center for American Women and Politics, in 2017, "1,830, or 24.8%, of the 7,383 state legislators in the United States are women. Women currently hold 441, or 22.4%, of the 1,972 state senate seats and 1,389, or 25.7%, of the 5,411 state house or assembly seats."12 Across the 50 states, the total seats held by women range from 11.1% in Wyoming to 40.0% in Vermont.13

Since the beginning of the 92nd Congress (1971-1972), the first Congress for which comparative state legislature data are available,14 the total percentage of women in state legislatures has eclipsed the percentage of women in Congress (see Figure 6). The greatest disparity between the percentages of female voting representation in state legislatures as compared with Congress occurred in the early 1990s, when women comprised 6.0% of the total Congress in the 102nd Congress (1991-1992), but 18.3% of state legislatures in 1991. The gap has since narrowed. In 2017, 19.6% of the total voting Members of Congress are women, as compared with 24.8% in state legislatures.

Female Election Firsts in Congress

- First woman elected to Congress. Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943).

- First woman to serve in the Senate. Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA) was appointed in 1922 to fill the unexpired term of a Senator who had died in office. In addition to being the first female Senator, Mrs. Felton holds two other Senate records. Her tenure in the Senate remains the shortest ever (one day), and, at the age of 87, she is the oldest person ever to begin Senate service.

- First woman to succeed her spouse in the Senate and also the first female initially elected to a full six-year term. Hattie Caraway (D-AR, 1931-1945) was first appointed in 1931 to fill the vacancy caused by the death of her husband, Thaddeus H. Caraway (D-AR, House, 1913-1921; Senate, 1921-1931), and then was subsequently elected to two six-year terms.

- First woman elected to the Senate without having first been appointed to serve in that body and first woman to serve in both houses of Congress. Margaret Chase Smith (R-ME) was elected to the Senate and served from January 3, 1949, until January 3, 1973. She had previously served in the House (June 3, 1940, to January 3, 1949).

- First woman elected to the Senate without first having been elected to the House or having been elected or appointed to fill an unexpired Senate term. Nancy Landon Kassebaum (R-KS, 1979-1997).

- First woman elected Speaker of the House. As Speaker of the House in the 110th and 111th Congresses (2007-2010), Nancy Pelosi held the highest position of leadership ever by a woman in the U.S. government.

Records for Length of Service

- Longest total length of service by a woman in Congress. Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), who served from January 3, 1977, to January 3, 2017, holds this record (40 years, 10 of which were spent in the House). On March 17, 2012, Senator Mikulski surpassed the record previously held by Edith Nourse Rogers (R-MA).

- Longest length of service by a woman in the House. On March 18, 2019, currently serving Representative Marcy Kaptur (D-OH) surpassed the record previously held by Representative Rogers. Representative Kaptur has been serving in the House since January 3, 1983. Representative Rogers served in the House for 35 years, from June 25, 1925, until her death on September 10, 1960.

Representative Rogers continues to hold the record for length of House service by a woman. - Longest length of service by a woman in the Senate. Senator Mikulski also holds the record for length of Senate service by a woman (30 years). In January 2011, she broke the service record previously held by Senator Margaret Chase Smith (R-ME), who served 24 years in the Senate and 8.6 years in the House.

Women Who Have Served in Both Houses

Twelve women have served in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Margaret Chase Smith (R-ME) was the first such woman, as well as the first woman elected to the Senate without first having been elected or appointed to fill a vacant Senate seat. She was first elected to the House to fill the vacancy caused by the death of her husband (Clyde Smith, R-ME, 1937-1940), and she served from June 10, 1940, until January 3, 1949, when she began her Senate service. She served in the Senate until January 3, 1973.

Barbara Mikulski (D-MD), Barbara Boxer (D-CA), Olympia Snowe (R-ME), Blanche Lambert Lincoln (D-AR), Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), Maria Cantwell (D-WA), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), Mazie Hirono (D-HI), Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV), and Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) are the other women who have served in both houses.

Seven of the 12 women (the exceptions being Senators Smith, Mikulski, Boxer, Snowe, and Lincoln) continue to serve in the 115th Congress.

African American Women in Congress

Twenty-one African American women serve in the 115th Congress, including two delegates2 Delegates, a record number. The previous record number was 20, including 2 delegatesDelegates, serving at the end of the 114th Congress.

A total of 41 African American women have served in Congress.15 The first was Representative Shirley Chisholm (D-NY, 1969-1983). Senator Carol Moseley-Braun (D-IL, 1993-1999) was the first African American woman to have served in the Senate. The African American women Members of the 115th Congress are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. African American Women in the 115th Congress

(All are House Members except for Sen. Kamala Harris)

|

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) |

Alma Adams (D-NC) |

Marcia Fudge (D-OH) |

Gwen Moore (D-WI) |

|

Karen Bass (D-CA) |

Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) |

Terri Sewell (D-AL) |

|

|

Joyce Beatty (D-OH) |

Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) |

Maxine Waters (D-CA) |

|

|

Lisa Blunt Rochester (D-DE) |

Robin Kelly (D-IL) |

Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-NJ) |

|

|

Yvette Clarke (D-NY) |

Brenda Lawrence (D-MI) |

Frederica Wilson (D-FL) |

|

|

Val Demings (D-FL) |

Barbara Lee (D-CA) |

Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC) [Delegate] |

|

|

Mia Love (R-UT) |

Stacey Plaskett (D-VI) [Delegate] |

Source: U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-of-Color-in-Congress/.

Note: Sen. Kamala Harris is also Asian Pacific American, and she is counted in both categories.

Asian Pacific American Women in Congress

Eleven Asian Pacific American women, a record number, serve in the 115th Congress.16 Patsy Mink (D-HI), who served in the House from 1965 to 1977 and again from 1990 to 2002, was the first of 13 Asian Pacific American women to serve in Congress. Mazie Hirono (D-HI) is the first Asian Pacific American woman to serve in both the House and Senate.

Table 4. Asian Pacific American Women in the 115th Congress

(All House Members except for Sens. Duckworth, Harris, and Hirono)

|

Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) |

Judy Chu (D-CA) |

Doris O. Matsui (D-CA) |

|

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) |

Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) |

Grace Meng (D-NY) |

|

Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-HI) |

Colleen Hanabusa (D-HI) |

Stephanie Murphy (D-FL) |

|

Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) |

Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen (R-AS) [Delegate] |

Source: U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-of-Color-in-Congress/.

Note: Sen. Kamala Harris is also African American, and is counted in both categories.

Hispanic Women in Congress

Fourteen Hispanic or Latino women have served in Congress, all but 1one in the House, and 11 of them serve in the 115th Congress. Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL, 1989-present) is the first Hispanic woman to serve in Congress, and Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV, 2017-present) is the first Hispanic woman Senator.17

|

Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) |

Nanette Diaz Barragán (D-CA) |

Jamie Herrera Beutler (R-WA) |

Linda Sánchez (D-CA) |

|

Michelle Lujan Grisham (D-NM) |

Grace Flores Napolitano (D-CA) |

Norma Torres (D-CA) |

|

|

Jennifer González-Colon (R-PR) [Resident Commissioner] |

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL) |

Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) |

|

|

Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) |

Source: U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, at http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-of-Color-in-Congress/.

Women Who Have Served in Party Leadership Positions18

A number of women in Congress, listed in Table 6, have held positions in their party's leadership.19 Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) held the highest position of leadership ever held by a woman in the U.S. government. As Speaker of the House in the 110th and 111th Congresses, she was second in the line of succession for the presidency. In the 108th, 109th, and 112th -115th Congresses, she was elected the House Democratic leader. Previously, Representative Pelosi was elected House Democratic whip, in the 107th Congress, on October 10, 2001, effective January 15, 2002. She was also the first woman nominated to be Speaker of the House. Senator Margaret Chase Smith (R-ME), chair of the Senate Republican Conference from 1967 to 1972, holds the Senate record for the highest, as well as first, leadership position held by a female Senator. The first woman Member to be elected to any party leadership position was Chase Going Woodhouse (D-CT), who served as House Democratic Caucus Secretary in the 81st Congress (1949-1950).

|

Position |

Member |

Congresses |

|

Speaker of the House |

Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) |

110th-111th (2007-2010) |

|

House Democratic Leader |

Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) |

108th-109th, 112th-115th (2003-2006, 2011-present) |

|

House Democratic Whip |

Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) |

107th (2001-2002) |

|

Chief Deputy Democratic Whip |

Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) Terri Sewell (D-AL) Diana DeGette (D-CO) Janice Schakowsky (D-IL) Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) Maxine Waters (D-CA) |

114th-115th (2015-present) 113th-115th (2013-present) 112th-115th (2011-present) 112th-115th (2011-present) 112th-115th (2011-present) 106th-110th (1999-2008) |

|

House Democratic Caucus Vice Chair |

Barbara Kennelly (D-CT) Mary Rose Oakar (D-OH) Linda Sánchez (D-CA) |

104th-105th (1995-1998) 100th (1987-1988) 115th (2017-present) |

|

House Democratic Caucus Secretarya |

Mary Rose Oakar (D-OH) Geraldine Ferraro (D-NY) Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) Patsy Mink (D-HI) Leonor Kretzer Sullivan (D-MO) Edna Flannery Kelly (D-NY) Chase Going Woodhouse (D-CT) |

99th (1985-1986) 97th-98th (1981-1984) 95th-96th (1977-1980) 94th (1975-1976) 86th-87th (1959-1962), 88th, 2nd session-93rd (1964-1974) 83rd-84th (1953-1956), 88th, 1st session (1963) 81st (1949-1950) |

|

House Republican Conference Chair |

Cathy McMorris Rogers (R-WA) Deborah Pryce (R-OH) |

113th-115th (2013-present) 108th-109th (2003-2006) |

|

House Republican Conference Vice Chair |

Lynn Jenkins (R-KS) Cathy McMorris Rogers (R-WA) Deborah Pryce (R-OH) Kay Granger (R-TX) Tillie Fowler (R-FL) Jennifer Dunn (R-WA) Susan Molinari (R-NY) Lynn Martin (R-IL) |

113th-114th (2013-2016) 111th-112th (2009-2012) 107th ( 110th (2007-2008) 106th (1999-2000) 105th (1997-1998) 104th-105th (1995-Aug. 1997) 99th-100th (1985-1988) |

|

House Republican Conference Secretary |

Virginia Foxx (R-NC) Barbara Cubin (R-WY) Deborah Pryce (R-OH) Barbara Vucanovich (R-NV) |

113th-114th (2013- 107th (2001-2002) 106th (1999-2000) 104th (1995-1996) |

|

Senate Republican Conference Chair |

Margaret Chase Smith (R-ME) |

90th-92nd (1967-1972) |

|

Senate Republican Conference Vice Chairb |

Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX) |

111th (2009-2010) 107th-109th (2001-2006) |

|

Senate Democratic Conference Vice Chair |

Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) |

115th (2017-present) |

|

Senate Democratic Conference Secretary |

Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) Patty Murray (D-WA) Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) |

115th (2017-present) 110th-114th (2007-2016) 109th (2005-2006) 104th-108th (1995-2004) |

|

Senate Chief Deputy Democratic Whip |

Barbara Boxer (D-CA) |

110th-114th (2007-2016) |

Source: U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-Elected-to-Party-Leadership/, and CRS Report RL30567, Party Leaders in the United States Congress, 1789-2017, by [author name scrubbed].

a.

The title of this position changed from "Secretary" to "Vice Chair" with the 100th100th Congress.

b.

This position was previously known as the Conference Secretary.

Women and Leadership of Congressional Committees

As chair of the House Expenditures in the Post Office Department Committee (67th-68th Congresses), Mae Ella Nolan was the first woman to chair any congressional committee. As chair of the Senate Enrolled Bills Committee (73rd-78th Congresses), Hattie Caraway was the first woman to chair a Senate committee. In total,

- 20 women have chaired a House committee;

- 13 women have chaired a Senate committee;

- 1 female Senator has chaired

2two joint committees (related to her service on a standing committee); and - 2 female Representatives have chaired a joint committee.20

In the 115th Congress, there are fivecurrently four committees led by women: threetwo standing committees in the House, one standing committee in the Senate, and one select committee in the Senate.

|

Committee |

Chair |

|

House Committee on the Budget |

Diane Black (R-TN) [until January 11, 2018] |

|

House Committee on Education and the Workforce |

Virginia Foxx (R-NC) |

|

House Committee on Ethics |

Susan Brooks (R-IN) |

|

Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources |

Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) |

|

Senate Special Committee on Aging |

Susan Collins (R-ME) |

Source: "Women Who Have Chaired Congressional Committees in the U.S. House, 1923-present" table of the Women in Congress website at http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-Chairs-of-Congressional-Committees/; and the "Committee Assignments of the 115th Congress" website at http://www.senate.gov/general/committee_assignments/assignments.htm.

Assessing the Effect of Women in Congress

In the past three decades, scholars of Congress have published dozens of articles and books examining whether the growing number of elected women in Congress has affected the operations of the institution or its legislative outcomes. Common questions in the scholarly literature include, is female legislative behavior distinct? Are women effective legislators in Congress? Has the larger cohort of women in Congress altered the policymaking process in substantial ways? This section provides a brief overview of the empirical analysis available to answer these questions.

Legislative Behavior

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the legislative behavior of female Members differs from their male counterparts. By virtue of their gender, some scholars argue, female Members of Congress "descriptively represent" a significant portion of the country's population, namely women.21 But scholars have asked repeatedly whether such descriptive representation has also translated into "substantive representation."22 In other words, are female Members of Congress more likely to address the interests or policy preferences of women?

Evidence shows that female Members are more likely to serve as policy entrepreneurs concerning issues often characterized as most important to women.23 In particular, women are more likely to sponsor, co-sponsor, or assume other leadership roles on legislation dealing with "women's issues."24 These roles may include leading committee and floor debate.25 In an attempt to control for district-specific characteristics and effects, other researchers show that when female Members replace males in the same congressional district, these women sponsor more women's issues bills and speak more frequently on the House floor about women than the men who previously held their seat.26 Recent scholarship also suggests that men in the Senate may engage in descriptive representation, particularly when the sponsorship and co-sponsorship of men's health legislation is analyzed.27

Female Members are more likely to speak on the House floor, giving proportionately more one-minute speeches than their male counterparts and speaking more often during policy debates. Even when district characteristics, ideology, and seniority of the Member were considered, gender still remained an important predictor of speech frequency on the House floor.28 When speaking on the House floor, female Members of both parties more frequently talk about women and women's issues than their male co-partisans.29

Numerous studies have examined the roll call voting behavior of female Members. In earlier research, this literature consistently demonstrated that female legislators tend to vote more "liberally" than men.30 However, more recent evidence examining longitudinal roll-call voting behavior suggests that such an ideological gender divide may be waning. Since the 108th Congress, Republican women's ideological voting patterns have exhibited no statistically significant difference in comparison to Republican men's voting scores. Democratic women have maintained slightly more liberal voting behaviors when compared with Democratic men.31 Another study demonstrated that when a woman succeeds a man or a man succeeds a woman in a given congressional district, there is no change in ideological voting scores in that seat from one Congress to the next.32 Furthermore, recent research examining roll call voting in both chambers revealed that gender minimally influences voting behavior, with the exception of female Republican Senators, who have historically voted more liberally than their male co-partisans in both chambers.33

Legislative Effectiveness

Using a variety of measures, scholars have attempted to determine the "effectiveness" of female legislators, particularly in comparison to male legislators. Based upon evidence which suggests that the path to election may be more difficult for women than men34 and that women who run for Congress have greater political experience than their male challengers,35 some researchers have theorized that women may outperform men in Congress. For example, while controlling for numerous other factors including district-level characteristics, an empirical model demonstrates that women deliver approximately 9% more federal spending to their districts than men. Women also sponsor approximately 3 more bills per Congress than men and cosponsor 26 more bills per Congress.36

Another study took a different view of effectiveness and examined the rate of sponsored bills that became law and the number of House floor amendments that were accepted to appropriations bills. After controlling for other key variables, the effect of gender on legislative effectiveness was not statistically significant, although the average success ratio (known as "hit-rate") for both measures was lower for female Members than their male counterparts.37 When seniority and other institutional leadership positions were taken into account, no empirical difference in success ratios existed between men and women in the House.

Recent research suggests that female legislators may be more effective in some political and institutional situations. A study focused on the House concluded that women in the minority party are more successful in legislating than minority party men.38 The collaborative approach espoused by many female legislators39 may work to their advantage when women find themselves in the minority party. Typically, the willingness to compromise or build consensus significantly improves the likelihood of minority party legislative advancement.

Finally, legislative effectiveness may influence female Members of Congress in one important way. Data indicate that a gender dynamic affected by legislative effectiveness may influence voluntary retirement decisions of female Members in the House of Representatives. According to the evidence, women are 40% more likely than men to retire from the House when they cease to increase their legislative effectiveness. In short, when women reach a "career ceiling" in the House, they turn more frequently to retirement than their male counterparts.40 This leads to average shorter tenures in Congress for women in comparison to men.

Impact of Women on Policy and Congress

While many scholars have focused on determining how female Members of Congress behave differently than their male counterparts, less attention has been focused on assessing the policy or institutional impact of increased numbers of women in Congress. However, some preliminary assessments have been made in this regard.

Several scholars have shown that women in Congress devote considerable time and resources to ensure that legislative provisions directly affecting women and families have prevailed in behind-the-scenes negotiations.41 Other evidence suggests that female Members have affected the early stages of the policymaking process in committee negotiations. Increased numbers of women in Congress have likely improved chances for women to influence policy outcomes at both the subcommittee and committee levels.42 Regardless of which party maintained the majority in Congress, one study concluded that female Members of Congress as a cohort have affected legislative outcomes in numerous instances.43

There is less scholarly evidence to support the hypothesis that the growing number of female Members has affected the institutional operations of Congress itself. At the state legislative level, research suggests that female committee chairs are more consensual, cooperative, and inclusive than their male colleagues.44 However, an examination of Senate committee assignments found no evidence that increased numbers of female Senators resulted in women sitting on more powerful committees45 and that lack of widespread female committee leadership in Congress thus far has prevented a comprehensive replication of this research at the federal level.

In short, the belief that a growing number of women in Congress would affect the institution in observable and substantive ways may be more complicated than originally theorized. One study that attempted to assess the impact of women in Congress cautiously concluded that while women may transform political institutions, they also may "be transformed by them and the larger political environment."46 In other words, it may prove difficult for social scientists to measure the impact of increased numbers of elected female Members on Congress because a causal relationship could exist in both directions.

Appendix. Total Number of Women Who Served in Each Congress

Table A-1. Congressional Service by Women: By Type and by Congress, 1917-2017

(Including any Representatives (Reps), Delegates (Del), and Resident Commissioners (RC) Who Served Only a Portion of the Congress)

|

Congress |

Reps |

Nonvoting Members (Del and RC) |

| Senate As the number of women in Congress has increased in recent decades, and following the large increase in women following the 1992 elections in particular, numerous studies of Congress have examined the role and impact of these women. Central to these studies have been questions about

(inclusive through April 13, 2018)

|

Congress

|

Reps.

|

House Subtotal (Reps and Nonvoting Members)

Nonvoting Members (Del. and RC) Sens. |

Total without |

Total |

|

65th (1917-1918) |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

66th (1919-1920) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||

|

67th (1921-1922)a |

3 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

4 |

|||

|

68th (1923-1924) |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

69th (1925-1926)b |

3 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

|||

|

70th (1927-1928)c |

5 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

5 |

|||

|

71st (1929-1930) |

9 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

9 |

|||

|

72nd (1931-1932)d |

7 |

0 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

8 |

|||

|

73rd (1933-1934) |

7 |

0 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

8 |

|||

|

74th (1935-1936) |

6 |

0 |

6 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

|||

|

75th (1937-1938)e |

6 |

0 |

6 |

3 |

9 |

9 |

|||

|

76th (1939-1940)f |

8 |

0 |

8 |

1 |

9 |

9 |

|||

|

77th (1941-1942)b |

9 |

0 |

9 |

1 |

10 |

10 |

|||

|

78th (1943-1944)c |

8 |

0 |

8 |

1 |

9 |

9 |

|||

|

79th (1945-1946)b |

11 |

0 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

11 |

|||

|

80th (1947-1948)g |

7 |

0 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

8 |

|||

|

81st (1949-1950)c |

9 |

0 |

9 |

1 |

10 |

10 |

|||

|

82nd (1951-1952)b |

10 |

0 |

10 |

1 |

11 |

11 |

|||

|

83rd (1953-1954)h |

11 |

1 |

12 |

3 |

14 |

15 |

|||

|

84th (1955-1956)c |

16 |

1 |

17 |

1 |

17 |

18 |

|||

|

85th (1957-1958) |

15 |

0 |

15 |

1 |

16 |

16 |

|||

|

86th (1959-1960)i |

17 |

0 |

17 |

2 |

19 |

19 |

|||

|

87th (1961-1962)j |

18 |

0 |

18 |

2 |

20 |

20 |

|||

|

88th (1963-1964)c |

12 |

0 |

12 |

2 |

14 |

14 |

|||

|

89th (1965-1966) |

11 |

0 |

11 |

2 |

13 |

13 |

|||

|

90th (1967-1968) |

11 |

0 |

11 |

1 |

12 |

12 |

|||

|

91st (1969-1970) |

10 |

0 |

10 |

1 |

11 |

11 |

|||

|

92nd (1971-1972)k |

13 |

0 |

13 |

2 |

15 |

15 |

|||

|

93rd (1973-1974)b |

16 |

0 |

16 |

0 |

16 |

16 |

|||

|

94th (1975-1976) |

19 |

0 |

19 |

0 |

19 |

19 |

|||

|

95th (1977-1978)l |

18 |

0 |

18 |

3 |

21 |

21 |

|||

|

96th (1979-1980)m |

16 |

0 |

16 |

2 |

18 |

18 |

|||

|

97th (1981-1982)n |

21 |

0 |

21 |

2 |

23 |

23 |

|||

|

98th (1983-1984)c |

22 |

0 |

22 |

2 |

24 |

24 |

|||

|

99th (1985-1986)c |

23 |

0 |

23 |

2 |

25 |

25 |

|||

|

100th (1987-1988)o |

24 |

0 |

24 |

2 |

26 |

26 |

|||

|

101st (1989-1990)p |

29 |

0 |

29 |

2 |

31 |

31 |

|||

|

102nd (1991-1992)q |

29 |

1 |

30 |

4 |

33 |

34 |

|||

|

103rd (1993-1994)r |

47 |

1 |

48 |

7 |

54 |

55 |

|||

|

104th (1995-1996) |

49 |

1 |

50 |

9 |

58 |

59 |

|||

|

105th (1997-1998)s |

55 |

2 |

57 |

9 |

64 |

66 |

|||

|

106th (1999-2000) |

56 |

2 |

58 |

9 |

65 |

67 |

|||

|

107th (2001-2002)t |

60 |

2 |

62 |

14 |

74 |

76 |

|||

|

108th (2003-2004)c |

60 |

3 |

63 |

14 |

74 |

77 |

|||

|

109th (2005-2006)u |

68 |

3 |

71 |

14 |

82 |

85 |

|||

|

110th (2007-2008)v |

76 |

3 |

79 |

16 |

92 |

95 |

|||

|

111th (2009-2010)w |

76 |

3 |

79 |

17 |

93 |

96 |

|||

|

112th (2011-2012)x |

76 |

3 |

79 |

17 |

93 |

96 |

|||

|

113th (2013-2014)y |

81 |

3 |

84 |

20 |

101 |

104 |

|||

|

114th (2015-2016)z |

85 |

4 |

89 |

20 |

105 |

109 |

|||

|

115th (2017-2018) |

84 |

5 |

89 |

21 |

105 |

110 |

Source: CRS summary, based on http://history.house.gov/Exhibition-and-Publications/WIC/Women-in-Congress/.

Notes: The column headings include the following abbreviations: Representatives (Reps.), Delegates (Del.), ), and Resident Commissioners (RC), and Senators (Sens.).

Three columns include numbers for the House: (1) the number of women Representatives, (2) the number of women nonvoting Members (including Delegates and Resident Commissioners), and (3) the total number of women in the House.

Totals are also provided for (1) the number of women in the House and Senate not including nonvoting Members and (2) the number of women in the House and Senate including nonvoting Members.

For simplification, Congresses are listed in two-year increments. Pursuant to the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, which was ratified Jan.January 23, 1933, "the terms of Senators and Representatives [shall end] at noon on the 3rd day of Jan." For specific dates, see "Dates of Sessions of the Congress, present-1789," at http://www.senate.gov/reference/Sessions/sessionDates.htm.

a.

Includes two House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy and one Senator who was appointed to fill a vacancy.

b.

Includes two House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

c.

Includes one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy.

d.

Includes one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy and one Senator who was appointed to fill a vacancy.

e.

Includes one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy but not sworn in, one Senator who was elected to fill a vacancy but not sworn in, and one Senator who was appointed to fill a vacancy.

f.

Includes four House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

g.

Includes one Senator who was appointed to fill a vacancy.

h.

Includes one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy, one Senator who was appointed to fill a vacancy, and one Senator who was elected to fill that vacancy.

i.

Includes one House Member who died and one House Member elected to fill a vacancy.

j.

Includes three House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

k.

Includes one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy and one Senator appointed to fill a vacancy.

l.

Includes two Senators who were appointed to fill a vacancy.

m.

Includes one House Member-elect whose seat was declared vacant due to an incapacitating illness, and one House member who was elected to fill a vacancy.

n.

Includes three House Members who were elected to a vacancy.

o.

Includes one House Member who died.

p.

Includes four House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

q.

Includes one House Member and one Senator elected to fill a vacancy and one Senator who was appointed to fill a vacancy.

r.

Includes one Senator who was elected to fill a vacancy.

s.

Includes one House Member who resigned and four House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

t.

Includes one House Member who died and one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy.

u.

Includes three House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

v.

Includes four House Members who died and four House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

w.

Includes two House Members who resigned, one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy, one Senator who resigned, and one Senator initially elected to the House and then appointed to the Senate.

x.

Includes two House Members who resigned and four House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

y.

Includes one House Member who resigned and three House Members who were elected to fill a vacancy.

z.

Includes two House Members who resigned and one House Member who was elected to fill a vacancy.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Linda Carter, Elli Ludwigson, and Cara Warner provided assistance. [author name scrubbed], formerly Deputy Director and Senior Specialistdeputy director and senior specialist, and [author name scrubbed], formerly an Analystanalyst on the Federal Judiciary, were former coauthors of this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Throughout this report, House and Senate totals each include one woman elected but not sworn in or seated due to the House or Senate being out of session. Both women are included in various official congressional publications, including, for example, the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress (http://bioguide.congress.gov), "Women in Congress" (http://history.house.gov/Exhibition-and-Publications/WIC/Women-in-Congress) and "Senators of the United States 1789-present: a chronological list of senators since the First Congress in 1789," maintained by the Senate Historical Office (http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/chronlist.pdf). |

|||||||

| 2. |

The Year of the Woman: Myths and Realities, ed. Elizabeth Adell Cook, Sue Thomas, and Clyde Wilcox (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994). |

|||||||

| 3. |

Vermont, however, ranks among the highest for percentage of women in state government. For additional information, see the "State-House Perspective" section. |

|||||||

| 4. |

Totals include one woman from South Carolina (House) and one woman from South Dakota (Senate) elected but never sworn in due to the House or Senate being out of session. |

|||||||

| 5. |

"[W]hen vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies." Article I, Section 2, clause 4 of the U.S. Constitution. |

|||||||

| 6. |

Prior to the ratification of this amendment, Senators were chosen pursuant to Article I, Section 3, of the Constitution. For additional information, see Direct Election of Senators, available at http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Direct_Election_Senators.htm. |

|||||||

| 7. |

This includes one woman who was elected but never sworn in. |

|||||||

| 8. |

Source: "Appointed Senators" list available at http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/senators_appointed.htm. |

|||||||

| 9. |

Total number of Senators since January 1, 1913, was derived from the Senate's "Senators of the United States 1789-present: A chronological list of senators since the First Congress in 1789," available at http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/chronlist.pdf. Senators are listed by date of initial service. |

|||||||

| 10. |

Inter-Parliamentary Union, Women in National Parliaments, situation as of 1st January 2017, at http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world.htm. See also the archive of historical data at http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/world-arc.htm. This data will be updated once per Congress. |

|||||||

| 11. |

For statistics on women serving in the national legislatures of 193 countries, see the IPU chart at http://www.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm; see also, Frank C. Thames and Margaret S. Williams, Contagious Representation: Women's Political Representation in Democracies around the World (New York University Press: New York, 2013). |

|||||||

| 12. |

Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University, Women in State Legislatures 2017, at http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/women-state-legislature-2017. |

|||||||

| 13. |

Ibid. |

|||||||

| 14. |

The Center for American Women and Politics provides data for state legislatures for odd-numbered years. Congressional data show the maximum number of women elected or appointed to serve in a Congress at one time during that Congress. |

|||||||

| 15. |

This number includes one Senator, Kamala Harris, who is of African American and Asian ancestry. In this report, this Senator is counted as belonging to two ethnic groups. For additional information, see U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, Black Americans in Congress, at http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/BAIC/Black-Americans-in-Congress/. |

|||||||

| 16. |

This number includes one Senator, Kamala Harris, who is of African American and Asian ancestry. In this report, this Senator is counted as belonging to two ethnic groups. |

|||||||

| 17. |

For additional information, see U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, Hispanic Americans in Congress at http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/HAIC/Hispanic-Americans-in-Congress/. |

|||||||

| 18. |

For additional information, refer to CRS Report RL30567, Party Leaders in the United States Congress, 1789-2017, by [author name scrubbed]. Limited information on the leadership positions held by women in Congress can also be found in CRS Report RL30261, Women in Congress, 1917-2017: Biographical and Committee Assignment Information, and Listings by State and Congress, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||

| 19. |

U.S. Congress, House, Office of the Historian, "Women Elected to Party Leadership Positions, 1949–Present," http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-Elected-to-Party-Leadership/. |

|||||||

| 20. |

Totals include standing, special, and select committees. Some women have chaired multiple committees. For additional information, refer to the "Women Who Have Chaired Congressional Committees in the U.S. House, 1923-present" table of the Women in Congress website at http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Data/Women-Chairs-of-Congressional-Committees/. |

|||||||

| 21. |

| |||||||

| 22. |

According to Pitkin, substantive representation concerns whether the representative advances the policy preferences or best interests of those individuals he or she represents. |

|||||||

| 23. |

Policy entrepreneurs are individuals inside or outside government who work to implement or promote new policy ideas. See Michael Mintrom, "Policy Entrepreneurs and the Diffusion of Innovation," American Journal of Political Science, vol. 41 (July 1997), p. 739. |

|||||||

| 24. |

Studies characterize "women's issues" differently. The term often includes women's rights, economic status, health, and safety. Sometimes included are children's issues, education, social welfare, and the environment. In other studies, "women's issues" are explicitly defined in more feminist terms, such as policies that advocate pro-choice abortion positions. See Beth Reingold, "Women as Office Holders: Descriptive and Substantive Representation," paper presented at the Political Women and American Democracy Conference, University of Notre Dame, May 25-27, 2006, p. 6. |

|||||||

| 25. | Studies characterize "women's issues" differently, and there is no universally accepted definition. See Beth Reingold, "Women as Office Holders: Descriptive and Substantive Representation," paper presented at the Political Women and American Democracy Conference, University of Notre Dame, May 25-27, 2006, p. 6; Victoria A. Rickard, "The Effects of Gender on Winnowing in the U.S. House of Representatives," Politics & Gender, vol. 12 (2016), 814-816. See, for example, Mary Hawkesworth, Kathleen Casey, Krista Jenkins, and Katherine Kleeman, Legislating By and For Women: A Comparison of the 103rd and 104th Congresses, Center for American Women and Politics, 2001, available at http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/research/topics/documents/CongReport103-104.pdf; Kathryn Pearson and Logan Dancey, "Elevating Women's Voices in Congress: Speech Participation in the House of Representatives," Political Research Quarterly, vol. 64 (December 2011), pp. 910-923; Kathryn Pearson and Logan Dancey, "Speaking for the Underrepresented in the House of Representatives: Voicing Women's Interests in a Partisan Era," Politics & Gender, vol. 7 (December 2011), pp. 493-519; Kelly Dittmar, Kira Sanbonmatsu, Susan J. Carroll, Debbie Walsh, and Catherine Wineinger, "Representation Matters: Women in the U.S. Congress," New Brunswick, NJ: Center for American Women in Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey (2017). | |||||||

| 26. | Jessica C. Gerrity, Tracy Osborn, and Jeannette Morehouse Mendez, "Women and Representation: A Different View of the District?" Politics & Gender, vol. 3 (June 2007), pp. 179-200. | |||||||

| 27. | Jennifer Sacco, 2012, "Descriptive Representation of Men and Women in the 110th and 111th Congresses," Paper presented at the Western Political Science Association Annual Meeting. See http://wpsa.research.pdx.edu/meet/2012/sacco.pdf. | |||||||

| 28. |

For example, in the 109th Congress, women averaged 14.9 one-minute speeches whereas men averaged 6.5 speeches, a statistical difference at the .002 probability level. Kathryn Pearson and Logan Dancey, "Elevating Women's Voices in Congress: Speech Participation in the House of Representatives," Political Research Quarterly, vol. 64 (December 2011), pp. 910-923. |

|||||||

| 29. |

Kathryn Pearson and Logan Dancey, "Speaking for the Underrepresented in the House of Representatives: Voicing Women's Interests in a Partisan Era," Politics & Gender, vol. 7 (December 2011), pp. 493-519. |

|||||||

| 30. |

| |||||||

| 31. | Jocelyn Jones Evans, Women, Partisanship and the Congress (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005); Michele L. Swers, "Are Women More Likely to Vote For Women's Issue Bills than Their Male Colleagues?" Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 23 (1995), pp. 435-448. Brian Frederick, "Are Female House Members Still More Liberal in a Polarized Era? The Conditional Nature of the Relationship Between Descriptive and Substantive Representation," Congress & the Presidency, vol. 36 (2009), pp. 181-202. | |||||||

| 32. |

| |||||||

| 33. | Brian Frederick, "Gender and Roll Call Voting Behavior in Congress: A Cross-Chamber Analysis," The American Review of Politics, vol. 34 (Spring 2013), pp. 1-20. |

|||||||

|

See, for example, | ||||||||

| 35. |

Kathryn Pearson and Eric McGhee, "Why Women Should Win More Often Than Men: Reassessing Gender Bias in U.S. House Elections," Unpublished manuscript, University of Minnesota. |

|||||||

| 36. |

Sarah Anzia and Christopher Berry, "The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson Effect: Why Do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen?" American Journal of Political Science, vol. 55 (July 2011), pp. 478-493. |

|||||||

| 37. |

Alana Jeydel and Andrew J. Taylor, "Are Women Legislators Less Effective? Evidence from the U.S. House in the 103rd-105th Congress," Political Research Quarterly, vol. 56 (March 2003), pp. 19-27. |

|||||||

| 38. | Cindy Simon Rosenthal, "A View of Their Own: Women's Committee Leadership Styles and State Legislatures," Policy Studies Journal, vol. 25 (1997), pp. 585-600; Noelle Norton, "Transforming Policy from the Inside: Participation in Committee," in Women Transforming Congress, ed. Cindy Simon Rosenthal (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), pp. 316-340; Michele L. Swers, The Difference Women Make (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Laura W. Arnold and Barbara M. King, "Women, Committees, and Institutional Change in the Senate," in Women Transforming Congress, ed. Cindy Simon Rosenthal (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), pp. 284-315; Alana Jeydel and Andrew J. Taylor, "Are Women Legislators Less Effective? Evidence from the U.S. House in the 103rd-105th Congress," Political Research Quarterly, vol. 56 (March 2003), pp. 19-27; Debra Dodson, The Impact of Women in Congress (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); Sarah Anzia and Christopher Berry, "The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson Effect: Why Do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen?" American Journal of Political Science, vol. 55 (July 2011), pp. 478-493; Craig Volden, Alan Wiseman, and Dana Wittmer, "When Are Women More Effective Lawmakers Than Men?" American Journal of Political Science, April, 2013, pp. 326-341, available at http:// See, for example, Jennifer Lawless and Kathyrn Pearson, "The Primary Reason for Women's Underrepresentation? Reevaluating the Conventional Wisdom," Journal of Politics, vol. 70 (2008), pp. 67-82; Richard L. Fox and Jennifer L. Lawless, "Gendered Perceptions and Political Candidacies: A Central Barrier to Women's Equality in Electoral Politics," American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 55, No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 59-73; Kathryn Pearson and Eric McGhee, "What It Takes to Win: Questioning 'Gender Neutral' Outcomes," Politics & Gender, 9 (2013), 439–462; Daniell M. Thomsen , "Why So Few (Republican) Women? Explaining the Partisan Imbalance of Women in the U.S. Congress," Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 2 (May 2015), pp. 295-423. See, for example, Ashley Baker, "Reexamining the gender implications of campaign finance reform: how higher ceilings on individual donations disproportionately impact female candidates," Modern American, Vol. 2 (2006) pp. 18-23; Michael H. Crespin and Janna L. Deitz, "If You Can't Join 'Em, Beat 'Em: The Gender Gap in Individual Donations to Congressional Candidates," Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 3 (September 2010), pp. 581-593; Karin E. Kitchens and Michele L. Swers, "Why Aren't There More Republican Women in Congress? Gender, Partisanship, and Fundraising Support in the 2010 and 2012 Elections," Politics & Gender, vol. 12 (2016), pp. 648-676. See, for example, Diane D. Kincaid, "Over His Dead Body: A Positive Perspective on Widows in the U. S. Congress," The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 31, no. 1 (Mar., 1978), pp. 96-104; Lisa Solowiej and Thomas L. Brunell, "The Entrance of Women to the U.S. Congress: The Widow Effect," Political Research Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 3 (September 2003), pp. 283-292; and Danielle Lupton, Sahar Parsa, and Steven Sprick Schuster, "Widows, Congressional Representation, and the (Ms.)Appropriation of a Name," unpublished manuscript, November 5, 2017. | |||||||

| 39. |

Cindy Simon Rosenthal, When Women Lead: Integrative Leadership in State Legislatures (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). |

|||||||

| 40. |

Members who reach a "career ceiling" have served a long tenure in the House but have not accrued positions of power, either in leadership or in committees. Jennifer L. Lawless and Sean M. Theriault, "Will She Stay or Will She Go? Career Ceilings and Women's Retirement from the U.S. Congress," Legislative Studies Quarterly, vol. 30 (November 2005), pp. 581-596. |

|||||||

| 41. |

Debra Dodson, The Impact of Women in Congress (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006); Swers, The Difference Women Make. |

|||||||

| 42. |

Noelle Norton, "Transforming Policy from the Inside: Participation in Committee," in Women Transforming Congress, ed. Cindy Simon Rosenthal (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), pp. 316-340. For specific examples concerning how women affected policies in committee, see pp. 332-337. |

|||||||

| 43. |

Mary Hawkesworth, Kathleen Casey, Krista Jenkins, and Katherine Kleeman, Legislating By and For Women: A Comparison of the 103rd and 104th Congresses, Center for American Women and Politics, 2001, available at http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/research/topics/documents/CongReport103-104.pdf. The authors examine legislative case studies in the policy areas of crime, women's health, health care, health insurance reform, reproductive rights, and welfare reform. The findings were compiled from interviews with female Members who served in those two Congresses. |

|||||||

| 44. |

Cindy Simon Rosenthal, "A View of Their Own: Women's Committee Leadership Styles and State Legislatures," Policy Studies Journal, vol. 25 (1997), pp. 585-600. |

|||||||

| 45. |

A Committee Power Index (CPI) was used in the study. Laura W. Arnold and Barbara M. King, "Women, Committees, and Institutional Change in the Senate," in Women Transforming Congress, ed. Cindy Simon Rosenthal (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), pp. 284-315. |

|||||||

| 46. |

|