Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Changes from June 15, 2017 to September 12, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Contents

- Introduction

- Consumer Out-of-Pocket Prescription Drug Costs

- Distribution of Prescription Drug Cost Sharing

- Manufacturer Co-payment Coupons

- Coupon Processing

- Coupon Distribution and Market Impact

- Other Drug Discount Coupons

- Restrictions on Coupon Use

- Federal Programs

- Federal Employees Health Benefit Program and ACA Qualified Health Plans

- Purchases by Enrollees "Outside" a Government Benefit

- HHS Office of Inspector General Report

- Private Insurance

- Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs

- What Is a 501(c)(3) Organization?

- Charity vs. Foundation

- Consumer Eligibility for PAP Assistance

- Legal Considerations Affecting PAP Giving

- 2005 HHS OIG Bulletin

- 2014 Update to HHS OIG Bulletin

- Justice Department Inquiries into PAP Operations

- Data Sources for Annual PAP Revenue and Giving

- How Are PAP Donations Valued?

- PAPs Appear to Have Increased in Size and Scope

- Information on Effectiveness of PAPs in Aiding Consumers

- Financial Impact of Coupons and PAPs

Summary

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and

September 12, 2022

Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Suzanne M. Kirchhoff

U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturers fund a variety of programs to help consumers defray

Analyst in Health Care

the cost of prescription drugs. Industry assistance includes drug discount coupons, as as

Financing

well as free drugs andor insurance cost-sharing payments for individuals with lower

incomes or high medicaldrug expenses. According to one analysis, drug manufacturers tendered discount coupons for more than 600 brands in 2016. Nonprofit95% of brand-name drugs offer manufacturer assistance and 75% of cost sharing in commercial insurance plans is

offset by manufacturers. In addition, nonprofit patient assistance programs (PAPs) offered by drug manufacturers and independent charities dispense billions of dollars in assistance annually, placing themsome among the nation's ’s largest charitable organizations.

Drug manufacturers say the generous aid is evidence of their commitment to patients who cannot afford a prescribed course of medication. Many manufacturer programs are designed to reduce consumer cost sharing for high-cost specialtyspecialty drugs used to treat cancer, hepatitis C, Crohn'’s disease, and other serious and chronic conditions. Industry analysts and the Department of Health and Human Services'’ Office of Inspector General say that the programs also are used to bolster manufacturer prescription drug sales and prices and can increase costs for government and commercial health payers. For example, an insured consumer may use a manufacturer coupon to buy a more expensive brand-name drug even if a lower-cost generic is available. Although the coupon reduces the consumer'’s cost-sharing obligation for the drug, it doesmay not cut the price paid by the consumer'’s health care plan.

Federal statutes, including anthe federal anti-kickback lawstatute, limit the use of coupons and manufacturer donations in conjunction with federal health care programs, such as the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. The anti-kickback lawstatute in Section 1128B(b) of the Social Security Act generally prohibits the knowing and willful offer or payment of remuneration to induce a person to buy an item or service that will be reimbursed by a federal health care program. In the private sector, some health plans have barred their enrollees from redeeming coupons for certain drugs or have chosen not to cover certain drugs that qualify for coupon discounts. Other health plans allow or encourage enrollees to redeem coupons for expensive drugs to improve the odds that the enrollees will complete a prescribed course of treatment.

This paper provides background on prescription drug coverage and consumer spending and on the role played by coupons and PAPs.

Introduction

U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturers spend billions of dollars annually on special assistance programs to defray the consumer cost of prescription drugs for both insured and uninsured individuals. Many manufacturers offer prescription drug discount coupons that reduce or eliminate required out-of-pocket payments for consumers, including insurance deductibles, co-payments, and coinsurance.11 Likewise, pharmaceutical manufacturers, along with some state governments and independent charities, operate patient assistance programs (PAPs) that provide free drugs or financial aid to help eligible individuals pay for prescription drugs based on factors including income, medical necessity, and health insurance status. Many PAPs are set up as 501(c)(3) nonprofit foundations or charities.2 2 Pharmaceutical companies may qualify for federal tax deductions for the donation of inventory through their own manufacturer PAPs or for making cash donations donating to independent charity PAPs.

Prescription drug assistance programs

There are restrictions on the use of pharmaceutical assistance. Drug coupons may not be used in conjunction with federal programs such as the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit, because the coupons may implicate, among other things, the federal anti-kickback statute.3 Manufacturer-sponsored PAPs may not offer cost-sharing assistance to enrollees in Medicare Part D and other federal programs. However, PAPs operated by independent charities (which are allowed to receive cash donations from drug companies) may assist beneficiaries in federal programs, if the PAPs comply with certain conditions.4

Pharmaceutical assistance programs, including PAPs and coupons, have increased in value and scope in recent years, even as the number of consumers with drug coverage has expanded. A study of retail pharmacy data found that enrollees in commercial insurance plans used co-payment coupons for one out of every five brand-name drug prescriptions in 2016.3 For some brands, coupon use was as high as two-thirds of filled prescriptions. Likewise, an analysis of . According to one analysis, 95% of brand-name drugs offer manufacturer assistance and 75% of cost sharing in commercial insurance plans is offset by manufacturers.5 A study of retail pharmacy data found that manufacturer coupons offset $12 billion in consumer prescription drug spending in 2019, an increase from $8 billion in 2013.6 More recent data show $14 billion in coupon use for commercially insured patients in 2020, which also includes the use of prepaid debit cards.7 An analysis of proprietary Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data found that giving by 10selected large drug manufacturer PAPs has risen substantially since the early 2000s, with 10 drug manufacturers providing $1.6 billion in aid in 2014,8 accounting for 85% of all

1 See text box entitled “Common Insurance Terms.” 2 See “What Is a 501(c)(3) Organization?” 3 See, generally, CRS Report RS22743, Health Care Fraud and Abuse Laws Affecting Medicare and Medicaid: An Overview. Anti-kickback statute (Section 1128B(b) of the Social Security Act) prohibits the knowing and willful offer or payment of remuneration to induce a person to buy an item or service that will be reimbursed by a federal health care program.

4 HHS OIG, “Special Advisory Bulletin: Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Copayment Coupons,” September 2014, at http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2014/SAB_Copayment_Coupons.pdf.

5 IQVIA, “Trends to Watch through 2023: Copay Accumulator Adjuster Programs,” March 21, 2022, at https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states/blogs/2022/03/trends-copay-accumulator-adjuster-programs.

6 IQVIA, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” August 2020, pp. 6, 9, at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports. The figures do not include prepaid debit cards, also offered by manufacturers. IQVIA provides a range of services including health care data analytics, management consulting, and product launch services. The company has compiled extensive pharmaceutical data sets from physician prescription and pharmacy claims information. Although most of the data are proprietary, IQVIA releases some reports to the public. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) uses IQVIA data in estimating national prescription drug spending.

7 IQVIA, “The Use of Medicines in the U.S.: Spending and Usage Trends and Outlook to 2025,” 2021, p. 46, at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports.

8 Austin Frerick, “The Cloak of Social Responsibility: Pharmaceutical Corporate Charity,” Tax Notes, November 28,

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 20 link to page 18 Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

pharmaceutical charity deductions and one-sixth of all U.S. corporate charity deductions that year.9 The largest drug manufacturer PAP in that study contributed more than $853 million in 2014, but a Congressional Research Service (CRS) review of more up-to-date IRS financial filings by selected manufacturer PAPs shows that, in 2019 and 2020, a number provided well over $1 billion each in annual assistance.10 An outside analysis of charitable giving included five charitable PAPs in the 2021 list of top 100 U.S. nonprofits (ranked by revenue).11

Pharmaceutical manufacturers say themanufacturer PAPs rose from $376 million in 2001 to $6.1 billion in 2014,4 accounting for 85% of all pharmaceutical giving and one-sixth of all U.S. corporate charity deductions in 2014. Giving by five of the main independent charity PAPs increased from $2 million in 2001 to $868 million in 2014, according to the study.5

Pharmaceutical manufacturers say their assistance programs are evidence of their commitment to ensure that prescription drugs remain affordable. They note that although more people have insurance, a growinggained insurance since the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) took effect, a number of insured consumers have difficulty meeting required prescription co-payments, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket costs. That is especially true for peopleappears to be especially the case for people in high deductible health plans (HDHP) and those prescribed high-cost specialty drugs. Manufacturers and drug marketers also view PAPs as a tool for creating brand loyalty12 However, recent studies indicate that coupons are also widely redeemed for relatively less expensive therapies, such as diabetes treatments, for which there is market competition.13

There is evidence that coupons may be a useful tool for improving enrollee adherence to prescriptions and improving health outcomes—possibly at the expense of higher health plan premiums.14 Industry internal documents and public statements have indicated that manufacturers and drug marketers also view PAPs as a crucial tool for creating brand loyalty, supporting higher list prices, and developing markets for new drugs.15

2016, at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2874391.

9 See “How Are PAP Donations Valued?” 10 CRS research based on IRS Form 990s for tax years 2018-2020. See “Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs”. 11 The NonProfit Times, “The 2021 NPT 100: Donors Stood Tall, Led With BIG Gifts,” November 3, 2021, https://www.thenonprofittimes.com/report/the-2021-npt-100-donors-stood-tall-led-with-big-gifts/. The NPT 100 is a report by The NonProfit Times—a business publication on nonprofit management—on the largest nonprofits in the United States that derive at least 10% of revenue from public support. The organizations were ranked by total revenue.

12 High deductible health plans (HDHP) refer to health plans with large out-of-pocket (OOP) spending requirements that must be met before coverage commences. Certain HDHPs help provide eligibility to establish and contribute to a health savings account (HSA). To be considered an HSA-qualified HDHP, a health plan must meet several tests: it must have a deductible above a certain minimum level, it must limit total annual out-of-pocket expenditures for covered benefits to no more than a certain maximum level, and it can provide only preventive care services and (for plan years beginning on or before December 31, 2021) telehealth services before the deductible is met. See CRS Report R45277, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs).

13 Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, “Prescription Drug Coupon Study: Report to the Massachusetts Legislature,” July 2020, p. 11, at https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/829870. 14 Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, “Prescription Drug Coupon Study: Report to the Massachusetts Legislature,” July 2020, p. 14, at https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/829870. According to the study, drug coupons increased utilization and spending for a number of drugs that have lower-cost generic alternatives that would be clinically appropriate for many patients, with implications for higher premiums. However, in cases where patients with commercial insurance could not afford clinically necessary medication, coupons provide financial relief and likely improve adherence, leading to better clinical outcomes. See also Catherine Starner et al., “Specialty Drug Coupons Lower Out-Of-Pocket Costs and May Improve Adherence At The Risk Of Increasing Premiums,” Health Affairs, vol. 33, no. 10 (October 2014), pp. 1761-1769.

15 HealthWell Foundation, “When Health Insurance Is Not Enough: How Charitable Copayment Assistance Organizations Enhance Patient Access to Care,” 2012, at https://www.healthwellfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/files/HWF-white%20paper%20for%20printing.pdf. Senate Committee on Finance, “The Price of Sovaldi and its Impact on the U.S. Health Care System,” December 1, 2015, link at https://www.finance.senate.gov/ranking-members-news/wyden-grassley-sovaldi-investigation-finds-revenue-driven-pricing-strategy-behind-84-000-hepatitis-drug.

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 25 link to page 16 link to page 28 link to page 28 Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Although a drug discount coupon may reduce the amount an insured consumer must pay out of pocket for a drug, it generally does not reduce the price charged to and developing markets for new drugs.6

There is some evidence that coupons may be a useful tool in improving enrollee adherence to expensive prescriptions, thereby improving health outcomes. A 2014 Health Affairs study using data from Prime Therapeutics, a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) owned by a group of Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, found that coupons helped consumers save $6 of every $10 in out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs, making the high-cost products more affordable for more patients and potentially improving adherence. However, the authors added that the increased use of coupons could increase costs for other beneficiaries in a health care plan if a payer decided to raise plan premiums, deductibles, or cost sharing to offset some of the expenses of the higher drug utilization.7

Health payers note that discount coupons can actually increase their costs by inducing individuals to use more expensive brand-name drugs in cases where generics or other lower-cost substitutes are available. Other studies by industry analysts and the Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG) have found that although the assistance programs expand access to drugs, they also bolster prices of prescription products.8 A drug discount coupon may reduce the amount an insured consumer has to pay out of pocket for a drug, but it generally does not reduce the price an insurer or government program is charged for the drug. The same is true with cost-sharing assistance offered through certain PAPs.16

More broadly, when consumers are relieved of cost-sharing obligations, there may be less market constraint on drug prices.

However, it is increasingly difficult to describe the impact of coupon and PAP support on drug sales, health payer spending, and enrollee prescription adherence because health care payers and insurers have begun to redesign their health plan benefits to maximize the amount of manufacturer prescription assistance dollars that the payers can collect—while sometimes reducing the enrollee benefit of the programs. For example, some private health insurance plans now employ so-called accumulator programs that allow enrollees to use manufacturer assistance to reduce the dollar amount of their cost-sharing for a given drug, but do not allow the manufacturer assistance to count against the enrollee’s deductible and/or annual out-of-pocket maximum requirements. (“Insurance Market Response to Coupons/PAPs”) Recent federal regulations have bolstered these market changes by allowing insurers to use coupon accumulators in certain ACA-regulated health plans. (“2020 HHS Rules on Co-payment Assistance”)

Evidence of fraud on the part of manufacturers and PAP operators has been an additional development. During the past several years the Department of Justice has stepped up enforcement of relevant laws governing manufacturer cost-sharing assistance and has collected billions of dollars in settlements from pharmaceutical companies and patient assistance programs charged with steering Medicare Part D beneficiaries to specific drugs. (“

Justice Department Action on Prescription Drug Aid Programs”)

This report will provide an overview of spending and coverage for prescription drugs, coupon and PAP offers and legal considerations, insurers’ responses to coupon programs, federal regulation and enforcement and information on real world impact of the pharmaceutical assistance.

16 HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG), “Special Advisory Bulletin: Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Copayment Coupons,” September 2014, at http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2014/SAB_Copayment_Coupons.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

3

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

market constraint on drug prices. A recent study of coupons for brand-name drugs for which generics were available found the coupons reduced the rate of generic substitution. The brand-name drugs with coupon offers had 12%-13% annual price growth, compared to 7%-8% price growth for those without coupons.9

There are restrictions on the use of pharmaceutical assistance. Drug coupons may not be used in conjunction with federal programs such as the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit because the coupons may implicate federal anti-kickback law.10 Manufacturer-sponsored PAPs may not offer cost-sharing assistance to enrollees in Medicare Part D and other federal programs. However, PAPs operated by independent charities (which are allowed to receive cash donations from drug companies) may assist federal beneficiaries, if the PAPs comply with certain conditions.11

In the private sector, some health care payers and PBMs have barred enrollees from redeeming manufacturer coupons for certain drugs. Others have decided not to include certain pharmaceuticals on their formulary, or list of covered drugs, if the products have coupon discounts.12 This report provides an overview of consumer spending on prescription drugs; explains the difference between drug coupons and PAPs; and outlines federal laws and regulations and private-sector policies relating to coupons and PAPs.

Common Insurance Terms Common Insurance Terms Brand-Name Drug: The Food and Drug Administration defines a brand-name drug as a drug marketed under a proprietary, trademark-protected name. Coinsurance: The percentage share that an Co-payment: A fixed Deductible: The amount an Formulary: A list of prescription drugs covered by an insurance plan. In an effort to control costs, insurers are imposing closed or partially closed formularies, which include a more limited number of drugs than traditional formularies. Generic: A generic drug is identical to a brand-name drug in dosage form, safety, strength, route of administration, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use. Although generic drugs are chemically identical to their branded counterparts, they are typically sold at substantial discounts from the branded price. High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP): High deductible health plans are health plans that require enrol ees to meet large out-of-pocket spending requirements before coverage commences. Certain HDHPs are eligible for special health savings accounts (HSA). To be considered an HSA-qualified HDHP, a health plan must: have a deductible above a certain minimum level, limit total annual out-of-pocket expenditures for covered benefits to no more than a certain maximum level, and provide only preventive care services and (for plan years beginning on or before December 31, 2021) telehealth services before the deductible is met. Out-of-Pocket Costs: The total amount an insured consumer pays each year for covered health care services that are not reimbursed by an insurance plan. Out-of-pocket costs can include deductibles, co-payments, and coinsurance. Out-of-Pocket Maximum: The maximum amount an Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): Intermediaries between health plans and pharmacies, drug wholesalers, and manufacturers. PBMs perform functions such as designing drug formularies, negotiating prices, and administering prescription drug payment systems on behalf of health plans. Pharmacy Network: A group of retail, mail-order, and specialty pharmacies that contract with PBMs and health insurers to dispense covered drugs at set prices. Network pharmacies also may provide other services under contract, such as monitoring patient adherence to drugs. Premium: The amount an Specialty Drug Tiered Pricing Underinsured: Refers to people who have insurance but |

Consumer Out-of-Pocket Prescription Drug Costs

Pharmaceutical assistance programs, in their current form, developed in the 1990s in response to public concern about high drug price inflation.13 The programs grew substantially in following decadesrising drug prices and lack of coverage.17 The programs have continued to grow despite a broad expansion of health insurance drug coverage and the widespread adoption of low-cost generic drugs.1418 Millions of consumers gained prescription drug coverage through Medicare Part D (Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003; P.L. 108-173) and the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended).15) and the 2010 ACA.19 The ACA, among other things, capscapped total annual out-of-pocket spending in many commercial health plans, including drug spending; eliminatesexpanded coverage through the health insurance exchanges and state-federal Medicaid program; eliminated cost sharing for contraceptives in many health plans; and reducesreduced annual cost sharing for Part D enrollees. Generic drug use now accounts for about 89% of filled prescriptions and 27% of total drug spending, according to the Generic Pharmaceutical Association.16

Largely as a result of these trends by closing the coverage gap or “doughnut hole.”20

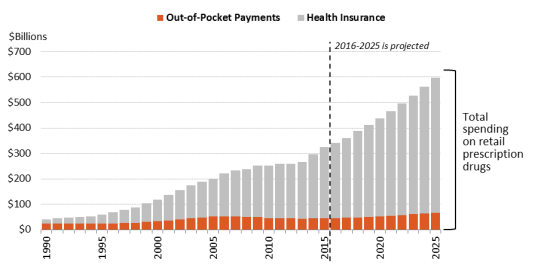

In 1990, consumer out-of-pocket spending—cash payments, health plan deductibles, coinsurance, and co-payments—declined fromfor filled prescriptions made up 57% of U.S. retail drug spending in 1990 to 14% in 2015. Spending by, whereas commercial payers and taxpayer-financed health programs accounted for about 43%, according to federal data. However, in the ensuing years, commercial payers and taxpayer-financed health programs have covered a growing share of the nation’s retail prescription drug bill. According to the National Health Expenditure (NHE) data, out-of-pocket spending declined to 13.3% of retail drug spending in 2020, versus about 86.7% for these other payers.21 Going forward, out-of-pocket (OOP) spending is projected to decline to 10.4% of outpatient drug spending by 2030. (Figure 1)

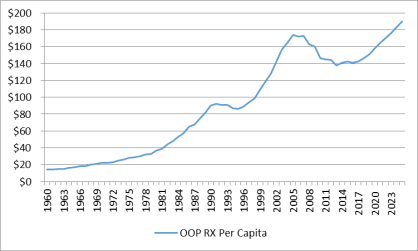

Looked at on a per capita basis, the NHE data show that average per person,programs rose from 43% to 86% of U.S. retail drug expenditures during this same period.17 (See Figure 1.) Likewise, per capita out-of-pocket spending declined from 56% of total out-of-pocket drug spending in 1990 to 14% in 2015.18 Looking forward, the National Health Expenditure (NHE) expects per capita out-of-pocket spending for retail prescription drugs fluctuated from $153 in 2014 to $141 in 2020. Out-of-pocket spending is forecast to increase gradually to $169 by 2030.22spending to rise by about 4% a year from 2016 through 2025. However, because cost sharing is not projected to increase as fast as total drug spending, out-of-pocketOOP expenditures are expected forecast to drop to 11%as a share of per capita drug spending.

17 Tom Norton, “The Vanishing Rx Patient Assistance Programs?” Pharmaceutical Executive, November 6, 2013, at http://www.pharmexec.com/vanishing-rx-patient-assistance-programs; Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Drug Company Programs Help Some People Who Lack Coverage,” November 2000, at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-01-137; Saul Weiner, Jill Dischler, and Cheryl Horvitz, “Beyond Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Assistance: Broadening the Scope of an Indigent Drug Program, American Journal of Health System Pharmacists, vol. 58, no. 2 (2001), at https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article-abstract/58/2/146/5149905.

18 Austin Frerick, “The Cloak of Social Responsibility: Pharmaceutical Corporate Charity,” Tax Notes, November 28, 2016, at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2874391.

19 See CRS In Focus IF10287, The Essential Health Benefits (EHB). The ACA requires insurers to provide drug benefits as part of qualified individual and fully-insured small-group health plans and provides incentives for states to expand enrollment in Medicaid. Although prescription drug coverage is an optional Medicaid benefit, all states include drug coverage. Medicare Part D was implemented in 2006. The ACA exchanges and incentives for Medicaid expansion took effect in 2014.

20 CRS Report R40611, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit. 21 “National Health Expenditure Data: Historical,” Table 16, at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. The NHE accounts estimate how much consumers pay each year to fill retail prescriptions including cash purchases and insurance deductibles, co-payments, and coinsurance. Insurance premiums are not included in out-of-pocket spending.

22 National Health Expenditure Data: Historical,” Table 16, at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. CMS, “National Health Expenditure Projections 2021-2030,” Table 11, at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsProjected.html.

Congressional Research Service

5

link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 14 link to page 31

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Figure 1. Total Out-Of-Pocket Spending as a Share of Retail Drug Spending

Source: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), National Health Expenditure (NHE) Data: Historical and Projected. Notes: Out-of-pocket spending includes cash payments, deductibles, co-payments, and coinsurance but does not include insurance premiums. Consumer out-of-pocket spending rose from $22.9 bil ion in 1990 to $46.5 bil ion in 2020 and is projected to reach $59 bil ion in 2030.

It may seem paradoxical that manufacturer assistance has increased while average out-of-pocket spending has moderated. There appear to be several reasons for continued growth of manufacturer aid.

Individual consumers can face significant out-of-pocket drug costs depending on

whether they have insurance coverage, the design of their health plan, and their specific diagnosis and prescribed medications. (See “Distribution of Prescription Drug Cost Sharing.”)

The growth of independent charity PAPs in the early 2000s created a way for

manufacturers to aid consumers enrolled in Medicare Part D without violating federal anti-kickback statutes. (See “Restrictions on Coupon Use.”)

Manufacturers and drug marketers view PAPs and discount coupons as important

tools for creating brand loyalty, supporting drug prices, and developing markets for new drugs. (See “Financial Impact of Coupons and PAPs.”)

of per capita drug spending by 2025. (See Figure 2.)

It may seem paradoxical that manufacturer assistance has increased while out-of-pocket spending has moderated. There appear to be several reasons for continued growth of manufacturer aid.

- Individual consumers can face significant drug costs depending on the design of their health plan and their specific diagnosis. A small but rapidly growing share of individuals face high out-of-pocket spending for specialty drugs for hepatitis C, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and other serious ailments.19 Pharmaceutical deductibles have become more prevalent. (See "Distribution of Prescription Drug Cost Sharing.)"

- The development of independent charity PAPs in the early 2000s created a way for manufacturers to aid consumers enrolled in Medicare Part D without violating federal anti-kickback statutes. Part D enrollees with high drug costs can have difficulty affording their medications when they are in the deductible phase of the benefit and when they reach the coverage gap—the period in which they are required to pay a larger share of total drug costs.20 (See "Restrictions on Coupon Use.")

Manufacturers and drug marketers often view PAPs and discount coupons as important tools for creating brand loyalty and developing markets for new drugs. (See "Financial Impact of Coupons and PAPs.")

(annual per person spending) |

|

|

Source: National Health Expenditure Data, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Notes: Figures from 2016 to 2025 are projected. Per capita out-of-pocket spending increased from $99 in 1998 to $173 in 2007. Per capita spending then declined to $138 in 2014 as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; P.L. 111-148, as amended) and Medicare Part D expansions took effect and a number of best-selling brand-name drugs lost patent protection, paving the way for low-cost generics to enter the market. Per capita out-of-pocket drug spending is forecast to reach $190 by 2025. |

Coupon and PAP Assistance in Pharmaceutical Spending Data Coupon and PAP Assistance in Pharmaceutical Spending Data

Manufacturer coupons and patient assistance program (PAP) assistance generally are not broken out in data sets on prescription drug spending, making it difficult to determine how the aid affects out-of-pocket costs and other measures of drug spending. For example, the Source: CRS April 2017 communication with CMS and Truven. |

Distribution of Prescription Drug Cost Sharing

As noted, the recent expansion of health coverage has improved consumer access to pharmaceuticals. Studies show that uninsured or underinsured consumers who have obtained drug benefits through Part D and the ACA are using more drugs and paying less, on average, to fill a prescription.21 Likewise, the share of consumers deciding not to fill a prescription, or to skip a required dose due to cost concerns, has declined since the ACA took effect.22

At the same time, consumer use of high-cost drugs, including specialty drugs, has been growing.23 Individuals prescribed high-cost drugs may face significant cost sharing as health payers shift a greater share of drug costs on to enrollees by increasing co-payments, coinsurance, and plan deductibles. For example, employer-sponsored health plans have expanded the use of tiered pricing, in which enrollees are charged lower co-payments for generic drugs and drugs that are more expensive or deemed less effective are put on higher tiers with greater co-payments or coinsurance.24 A 2016 survey of employer-based plans found that 38% had four or more drug tiers, commonly including a specialty drug tier, compared to 26% in 2012.25 The share of health plans imposing a prescription drug deductible also has been rising. From 2012 to 2015, the share of commercial health plans with a drug deductible jumped from 23% to 46%.26

The result of these parallel trends—expanded insurance coverage coupled with more stringent cost sharing—appears to have been a decline in average out-of-pocket spending but an increase in spending for enrollees who may have chronic conditions or be prescribed high-cost drugs.

A study of commercial health plan data found that mean out-of-pocket spending for specialty drugs (defined as those that cost $600 or more per month) rose from $41 in 2003 to $77 in 2014, whereas spending on non-specialty medications fell from $19 to $11 over the same time period.27 A second study of large employer-sponsored health plans found average out-of-pocket spending dipped to $144 in 2014 from a recent high of $167 in 2009.28 However, nearly 3% of enrollees had exceptionally high out-of-pocket costs (defined as more than $1,000) in 2014, accounting for one-third of drug spending and one-third of out-of-pocket spending. The share of people with high drug costs tripled from 2004.29

Manufacturer coupon offers and PAP assistance grants are designed to blunt health plan cost-sharing requirements by covering a portion of enrollee out-of-pocket payments. According to Quintiles IMS, as health plans have increased patient cost exposure in recent years, manufacturers have boosted coupons and other assistance.30 In 2016, manufacturer coupons were used for one out of every five brand-name prescriptions and for up to two-thirds of filled prescriptions for some specific drug brands.31

The following sections examine different forms of manufacturer assistance—discount coupons, manufacturer PAPs, and independent charity PAPs.

Manufacturer Co-payment Coupons

Pharmaceutical firms offer co-payment coupons or cards to help consumers reduce out-of-pocket costs. The coupons benefit consumers who otherwise might not be able to afford certain drugs. Coupons also benefit drugmakers by helping to create demand for newly introduced drugs, increase consumer adherence to existing prescriptions, and bolster the market for brand-name drugs that have lost patent exclusivity and face competition from lower-priced generics or other substitutes.32

costs, such as co-payments and coinsurance. While individual coupon offers may be for a limited period, such as six months or one year, manufacturers may allow patients to re-enroll.32

For a sense of how a coupon works, consider a pharmaceutical manufacturer that sells a brand-name drug to a commercial payer for $1,000 for a 30-day supply.3333 The payer places the drug on a price tier that imposes 25% enrollee coinsurance up to the plan'’s annual out-of-pocket maximum. To support sales of the drug, the manufacturer offers a coupon that limits out-of-pocket costs to $100 per 30-day refill for a 12-month period. In the absence of the manufacturer coupon, an enrollee would pay $250 out of pocket each time he or she went to a pharmacy to buy a 30-day supply of the drug (25% of the $1,000 price), until the annual out-of-pocket maximum was reached. With a coupon, the consumer would pay $100 per fill and the manufacturer would cover the remaining $150 of the required coinsurance up to the maximum subsidy amount.

Many co-payment coupons include disclaimers stating that they cannot be used by individuals enrolledenrollees in federal health programs, including Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans Health Administration. (See "“Restrictions on Coupon Use.") Manufacturers build the cost of co-payment coupons into their budget and pricing strategies and use analytics to target the offers.34

Coupon Processing

Coupons can be printed in a magazine or specially distributed advertising supplement, offered electronically—such as a discount number sent as a text to a smart device—or presented as a debit-type card.35 Coupons loaded on smartphones can provide automatic reminders to a consumer to refill a prescription. Manufacturers may offer starter cards that patients can use to receive an initial fill of a prescription at no cost while they wait for a coverage decision from their health plan.36

When an insured consumer presents a prescription at a pharmacy.”) Some coupons are expressly for use outside of insurance coverage, meaning without submitting an insurance claim.

(capped at $480 in 2022). Most workers covered by insurance offered by large employers that includes general deductibles do not have to meet the deductible before drug coverage begins. Kaiser Family Foundation, “2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” Section 7, Figure 7.27, at https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2021-section-7-employee-cost-sharing/. Workers covered by HDHPs may have higher costs. An IQVIA analysis of U.S. sample prescription drug claims data found that in 2019, brand-name drug claims in health plans’ deductible phase made up less than 1% of all claims, but nearly 15% of out-of-pocket spending. IQVIA defined deductible claims as those where the patient would pay more than 50% of the claim, and the primary patient payment was greater than $250. IQVIA, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” August 2020, medicine-spending-and-affordability-in-the-united-states.pdf (iqvia.com).

31 Kaiser Family Foundation, “2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” Section 5, at https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2021-section-5-market-shares-of-health-plans/.

32 For example, see “Aimovig® Copay Card Terms and Conditions,” at https://www.aimovigcopaycard.com/tcs. Aimovig, manufactured by Amgen Inc., is a treatment for migraine headaches.

33 Insurers and PBMs negotiate rebates and discounts from manufacturers on the drugs that they purchase for health plans or distribute through their own mail-order and specialty pharmacies. These rebates and discounts are separate from those that manufacturers offer consumers through coupons and other assistance programs. Overall drug pricing also includes payments to pharmacies that dispense the drugs and other costs and markups along the supply chain, but those costs have not been included to simplify the transaction.

Congressional Research Service

8

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Coupon Processing When an insured consumer’s prescription is presented at a pharmacy (either in person or through an electronic e-prescribing transaction), the pharmacist uses an electronic routing system to , the pharmacist uses an electronic routing system37 to submit a claim to the PBMpharmacy benefit manager (PBM) or health plan that manages the consumer'consumer’s specific pharmacy benefit.34 The PBM or plan processes the initial drug claim and determines the patient'’s cost-sharing obligation. The PBM's The electronic processing system then submits secondary claims to other payers. Secondary payments can include another insurance policy held by the individual or a manufacturer coupon. If a coupon is presented for coverage, the PBM or plan system, using special codes, will route a coupon to a manufacturer for payment.3835 After all payments are processed, the consumer covers the remaining co-payment, if any.

In certain instances, manufacturer discounts are not processed through anthe electronic system. Some coupon offers, such as offers that take the form of a rebate or discount after the point of sale. In this case, a consumer may make the required co-payment imposed by his or her primary insurance plan when filling a prescription, then send the pharmacy receipt and rebate offer to the manufacturer to secure the promised discount.39 Consumers also36

Consumers may use a coupon and pay cash for a drug that is not covered by antheir insurance plan, that is less expensive outside their insurance coverage, or if they do not have insurance.

Prescription Drug Discount Coupon Distribution Coupons can be printed in a magazine or advertising supplement, offered electronically—such as a discount offer on a website—or presented as a debit-type card. Manufacturers can directly offer coupons and/or work through vendors.37 Coupons loaded on smartphones can provide automatic reminders to a consumer to refill a prescription. Manufacturer coupons and other discount offers may be offered via special programs on physician electronic prescribing systems.38 Manufacturers may offer starter cards that patients can use to receive an initial fill of a prescription at no cost while they wait for a coverage decision from their health plan.

A portion of pharmaceutical assistance consists of special coupons and discount cards that reduce a drug’s retail price, but are not designed to be applied to health plan co-payments. The rise of digital platforms has made these services easier to use.39

34 National Council for Prescription Drug Programs, “Background and Guidance for Using g the NCPDP Standards for Digital Therapeutics,” August 2021, at https://www.ncpdp.org/NCPDP/media/pdf/Background-and-Guidance-for-Using-the-NCPDP-Standards-for-Digital-Therapeutics.pdf?ext=.pdf

35 HHS OIG, “Manufacturer Safeguards May Not Prevent Copayment Coupon Use for Part D Drugs,” September 2014, at http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-12-00540.pdf.

36 Ibid. 37 For example, see Abbvie, “Join the Before Breakfast Club,” offer for Synthroid assistance, at https://www.synthroid.com/support/before-breakfast-club. Abbvie offers discounts to both insured and uninsured consumers for the drug, used to treat hyperthyroidism.

38 GoodRx Announces Agreement with Surescripts to Provide Real-Time Drug Discount Pricing in Electronic Health Records, August 5, 2021, at https://investors.goodrx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/goodrx-announces-agreement-surescripts-provide-real-time-drug.

39 One example is digital health company Goodrx, which allows consumers to access discount offers for drugs, including both generic and brand drugs, without insurance. In addition, GoodRx has a telehealth service to help consumers obtain prescriptions and has agreements with certain companies to provide GoodRx discounts as an employee benefit. GoodRx revenues come from prescription transaction fees, subscriber fees, and payments from drug manufacturers and telehealth providers. According to the GoodRx quarterly letter to shareholders from May 2022, the

Congressional Research Service

9

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

Some pharmacies, nonprofit organizations, and PBMs also offer their own prescription drug cards or programs, which generally may not be used with government benefits or private insurance.40

Scope of Coupons and Discounts There are no comprehensive public data on co-payment coupon distribution and use. Manufacturers, consulting firms, PBMs, and various websites that serve as online clearinghouses for coupon offers release some information, but it is difficult to gauge the overall market.

According to IQVIA, retail pharmacy data show that manufacturer coupons (excluding prepaid debit cards) offset $12 billion in consumer prescription drug spending in 2019, an increase from $8 billion in 2013.41 A more recent IQVIA analysis found that coupons for commercially insured patients reached $14 billion in 2020 – including the use of prepaid debit cards.42 Coupon usage for branded drugs used by commercially covered patients in some therapy areas was high: 47% for drugs in the mental health category and 80% for immunology drugs. In another example, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) cite research that 70% percent of patients taking innovative medicines to treat multiple sclerosis in 2019 used cost-sharing assistance.43

Other studies indicate that coupons are not just important for specialty or single-source drugs, but for widely used products where there is market competition. A 2020 Massachusetts study of drug coupon use in the state found the top category of coupon use was drugs for treating diabetes, which represented 20% of all coupon volume. Antivirals, largely for HIV treatment and prevention but also for conditions such as Hepatitis C, were the second largest category with 11% of all coupons. The study suggested that coupon availability was “associated with moderately higher utilization of branded drugs relative to use of generic close therapeutic substitutes, and that coupon availability is associated with higher total spending.”44

company acquired vitaCare in April 2022, a pharmacy services platform that helps facilitate access to drugs, including manufacturer savings programs.

40 For example, see the CVS Caremark description of National League of Cities Prescription Discount Program, at http://nlc.org./nlc-prescription-discount-program; and OptumRx, at http://www.myprescriptiondrugsavings.com/welcome.aspx.

41 IQVIA, “Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States,” August 2020, p. 6 and p. 9. The figures do not include prepaid debit cards, also offered by manufacturers. Available for download at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports.

42 IQVIA, “The Use of Medicines in the U.S.: Spending and Usage Trends and Outlook to 2025,” May 2021, p. 46. Available for download at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports. Savings programs include coupons, e-coupons, prepaid debit cards, and average 50% of brand prescriptions in some of the highest overall spending specialty therapy areas, compared to 33% of leading traditional medicine therapy areas.

43 PhRMA vs. Becerra, et al., Civil Action No. 1:21-cv-1395, May 2021. The legal filing includes information on multiple sclerosis drugs from an IQVIA Analysis for PhRMA, U.S. Market Access Strategy Consulting Analysis (2020). According to the filing, the study also said that patients taking diabetes medicines would have paid more than twice as much out of pocket if they were prevented from using cost-sharing assistance. PhRMA is the main trade association for the pharmaceutical industry.

44 Massachusetts Health Policy Commission, “Prescription Drug Coupon Study: Report to the Massachusetts Legislature,” July 2020, p. 3, at https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/829870.

Congressional Research Service

10

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

insurance plan or if they do not have insurance.

Coupon Distribution and Market Impact

Industry data on co-payment coupon distribution and use are available from manufacturers, consulting firms, PBMs, and various websites that serve as online clearinghouses for coupon offers. According to data presented at an April 2016 industry meeting, the number of coupon programs had increased by more than a third during the previous two years to 600, at a cost to manufacturers of more than $5 billion a year.40 In January 2016, the average co-payment for coupon-using patients was more than $30, up from $15 in January 2013.

A separate analysis of retail pharmacy data found that co-payment coupons or vouchers were used by more than 14 million patients in the 12-month period ending in October 2012, of whom 90% used one program and 10% used multiple programs.41 Most of the coupons were used by patients with chronic conditions. The range of savings for the patients in this sample was wide, with coupons reducing costs by $40 on average.

While coupon offers may be for a limited time period, such as six months or one year, they are often renewed by manufacturers, who use them as a means to build loyalty to a brand.42 Manufacturers may use coupons as part of a marketing strategy to keep prices for brand-name drugs higher than they otherwise would be after a lower-cost generic substitute comes to market. Such a strategy was used when Pfizer blockbuster drug Lipitor was exposed to generic competition.43

Vendors that work with pharmaceutical companies to distribute pharmaceutical coupons say their internal data show that the programs increase drug adherence and the duration of therapy.44 Coupon programs also can generate data regarding patient income, age, and insurance status, which can be used by a company to develop pricing, marketing, and other strategies.45 Companies can use data on geographic differences in patient adherence to target coupon offers and other marketing efforts. One vendor found a $2 return for every $1 spent on coupon programs by a pharmaceutical client.46 A recent academic study of coupons for brand-name drugs with generic substitutes found a return on investment of at least 4:1 for the coupons and no higher than 7:1.47

The widespread adoption of electronic health records by physician practices is offering a faster, more efficient way for manufacturers and marketers to reach doctors and their patients. Physicians may be able to enter a prescription into an electronic system that is programmed to automatically call up information on co-payment coupon offers and send the offer to a pharmacy along with the prescription.48 When the consumer fills the claim, the pharmacy processes the coupon as it fills the prescription. Web-based platforms and software applications have been developed to help health care professionals locate coupons, distribute samples, or procure other discounts for their patients.49

Other Drug Discount Coupons

Some pharmacies, nonprofit organizations, and PBMs offer their own prescription drug cards or programs. These cards generally cannot be used with government benefits or private insurance.50 The offers have increased as health plans carrying high deductibles have become more prevalent and PBMs have taken a more direct approach to offering drug benefits.51 Consumer organizations say that drugstore discount cards can provide valuable benefits but that it can be hard to determine whether consumers are receiving the best price with the coupons given that retail drug prices can vary widely among pharmacies in the same geographic area.52 Although a card may show the price for a specific drug at participating pharmacies, it may not show the full range of prices at all area pharmacies. Websites such as Good Rx have been created to help consumers comparison shop for prescription drugs.53 In May 2017, PBM Express Scripts announced a new subsidiary, Inside Rx, which will offer discount cards and other offers on certain prescription drugs. The program is being offered in conjunction with Good Rx and a number of retail pharmacies and pharmaceutical firms.54

Restrictions on Coupon Use

Restrictions on Coupon Use

Federal Programs

There are limitations on use of co-payment couponsFederal Programs

Co-payment coupons cannot be used in conjunction with federal health benefitscare programs, including Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE military insurance, and Veterans Health Administration programs. The prohibition One limitation is based on the federal anti-kickback statutes,5545 which cover various types of remuneration—including kickbacks, bribes, and rebates—whether made directly or indirectly, overtly or covertly, in cash or in kind.5646 Pharmaceutical companies may be liable under the anti-kickback statute if they offer coupons to induce the purchase of drugs paid for by federal health care programs.

Retailers and other entities that submit claims to federal agencies for items or services resulting from a violation of anti-kickback statutes may also face civil monetary penalties and damages under the False Claims Act.57

47

Federal Employees Health Benefit Program and ACA Qualified Health Plans

Private health plans sold to federal workers through the Federal Employees Health Benefit (FEHB) Program are not considered government programsfederal health care programs for purposes of the anti-kickback statute. Enrollees in these plans may use drug discount coupons or pharmacy incentive programs in concert with their insurance benefits.58

48

Regarding qualified health plans sold under the ACA,59,49 former HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius in an October 2013 letter to Representative James McDermott and a February 2014 letter to Senator Charles Grassley said the HHS did not consider qualified health plans, as well as tax subsidies and cost-sharing assistance, to be federal programs.60

Purchases by Enrollees "Outside"50

Purchases and Donations ”Outside” a Government Benefit

There may be cases in which an individual covered by a federal health plan goes "outside"“outside” his or her benefit to purchase prescription drugs. AFor example, a Medicare Part D beneficiary may

45 Section 1128B(b) of the Social Security Act. 46 The HHS OIG in December 2016 issued final regulations to create safe harbors from the anti-kickback statute for certain Part D program activities. The rules provide protection for pharmacy waivers of cost sharing for financially needy Medicare Part D beneficiaries and for mandatory manufacturer discounts in the Part D coverage gap. The final rules are at 81 Federal Register 88368, December 7, 2016, at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-12-07/pdf/2016-28297.pdf. For the proposed rules, see HHS OIG, 42 C.F.R. Parts 1001 and 1003, “Medicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse; Revisions to Safe Harbors Under the Anti-Kickback Statute, and Civil Monetary Penalty Rules Regarding Beneficiary Inducements and Gainsharing,” 79 Federal Register 59717, October 3, 2014, at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/10/03/2014-23182/medicare-and-state-health-care-programs-fraud-and-abuse-revisions-to-safe-harbors-under-the#h-4.

47 31 U.S.C. §§3729-3733. See also 42 U.S.C. §1320a-7b(g). 48 See 42 U.S.C. §1320a-7b(f)(1). See also Office of Personnel Management, “Frequently Asked Questions: Insurance,” at https://www.opm.gov/faqs/QA.aspx?fid=fd635746-de0a-4dd7-997d-b5706a0fd8d2&pid=c8263db8-cf0e-4144-9e8a-13a1ef38c084.

49 A qualified health plan is an insurance plan that is certified by an exchange, provides essential health benefits, follows established limits on cost sharing (such as deductibles, co-payments, and out-of-pocket maximum amounts), and meets other requirements. See https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/qualified-health-plan/. Qualified health plans are sold in the non-group (individual) and small-group markets inside and outside exchanges.

50 Letter from Kathleen Sebelius, HHS Secretary, to Rep. McDermott, October 2013, at https://www.health-law.com/media/news/85_The-Honorable-Jim-McDermott.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

11

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

choose to pay cash for a drug at a retail pharmacy if doing so is cheaper than buying the drug through his or her Part D plan.

Although a Part D enrollee may use a coupon to purchase a drug outside the program, only the actual price paid for the drug—minus all discounts—counts toward Part D annual out-of-pocket spending limits.51

2014 Medicare Part D beneficiary may pay cash for a drug at a retail pharmacy if doing so is cheaper than buying the drug through his or her Part D plan.

Although a Part D enrollee may use a coupon to purchase a drug outside the program, only the actual price paid for the drug—minus all discounts—counts toward Part D annual out-of-pocket spending limits.61 Drugmaker Pfizer has made coupons for Lipitor, a cholesterol-battling drug, available to Part D beneficiaries who agree not to use them in tandem with their Part D benefit.62 Pharmacists may be unwilling to redeem coupons for enrollees in federal programs, even if the enrollees pay outside of their benefits, due to concerns about possible violations of federal law.

HHS Office of Inspector General Report

HHS Office of Inspector General Report A 2014 report from the HHS OIG said that pharmaceutical manufacturers did not have consistent, effective safeguards to prevent Medicare Part D beneficiaries from using co-payment coupons along with program benefits.63

52

Some beneficiaries might not be aware of the ban on coupons. According to the report, not all manufacturer offers carrycarried a disclaimer stating that the coupons, rebates, or other incentives may not be used by individuals enrolled in federal health care programs or in conjunction with federal benefits. The report noted that manufacturers that redeem coupons through PBM electronic claims systems have set up edits at the point of sale designed to identify individuals who may be enrolled in federal programs such as Medicare. For example, when an enrollee submits a coupon with a prescription, and when it is submitted to a manufacturer as a secondary payer, the manufacturer may check for a patient'’s primary insurance, Part D benefit stage,6453 and date of birth. (Actual Part D enrollment data is not available from CMS because it may contain sensitive personal information.)

However, the HHS OIG report found that the staged system for processing prescription drug claims can make it difficult for entities other than manufacturers to identify coupons as they move through the pharmacy transaction system. The report also noted that coupons redeemedmanufacturer discounts that are processed after the point of sale, such as mail-in rebates, may not be detected by electronic safeguard systems.

HHS issued a special advisory bulletin warning manufacturers that they faced potential penalties if they failed to take appropriate steps to ensure that such coupons do not induce the purchase of federal health care program items or services.54

In response to the 2014 HHS OIG guidance the NCPDP, which sets standards for electronic claims processing, in 2017 issued recommendations for better identifying coupons in Medicare Part D claims administration.55

51 Out-of-pocket spending amounts are adjusted annually. For more information, see CRS Report R40611, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit. In July 2014, the HHS OIG issued an advisory opinion regarding a direct-to-patient sales program sponsored by a specific pharmaceutical manufacturer under which an individual may buy a prescription drug at a fixed cash price through an online pharmacy. HHS OIG, “OIG Advisory Opinion 14-05,” July 28, 2014, at https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/advisory-opinions/14-05/. CMS has also issued separate guidance for Part D cash purchases at out-of-network pharmacies where coupon use is not involved. CMS, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Manual, Chapter 14, Section 50.4.2, at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Chapter14.pdf.

52 HHS, OIG, Manufacturer Safeguards May Not Prevent Copayment Coupon Use for Part D Drugs, September 2014, at http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-12-00540.pdf.

53 For example, an individual enrolled in Part D might not have met the annual deductible. 54 HHS OIG, “Special Advisory Bulletin: Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Copayment Coupons,” September 2014, at http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2014/SAB_Copayment_Coupons.pdf.

55 NCPDP, “Recommendations for Use of the NCPDP Telecommunication Standard to Prevent Use of Copayment Coupons by Medicare Part D Beneficiaries and Applicability to other Federal Programs,” Version 1.1, May 1, 2017,

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 25 link to page 25 Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

2020 HHS Rules on Co-payment Assistance In 2020, HHS issued two final regulations affecting manufacturer coupon programs: one governing commercial plans sold on health insurance exchanges, and another affecting the calculation of prices for drugs sold through the state-federal Medicaid program. The rules were issued in response to increased use of accumulator programs, under which a health plan or issuer allows an enrollee to use a coupon or other manufacturer program to defray the out-of-pocket costs for filling a prescription but does not count the value of the manufacturer assistance against the enrollee’s deductible and/or annual out-of-pocket maximum. (See “Insurance Market Response to Coupons/PAPs”)

2020 HHS Coupon Accumulator Final Rule for Qualified Health Plans

In a final rule published in 2020,56 HHS gave issuers of certain health plans authority to decide whether to count any form of direct pharmaceutical manufacturer support, such as coupons, as part of enrollee cost sharing for purposes of meeting annual OOP spending caps. The regulation applies to health plans sold on the health insurance exchanges, and non-grandfathered individual and group health plans sold off the exchanges.57

Under the rule, to “the extent consistent with state law, amounts of direct support offered by drug manufacturers to enrollees for specific prescription drugs towards reducing the cost sharing incurred by an enrollee using any form are not required to be counted toward the annual limitation on cost sharing.”58

The 2020 final rule was a modification of a 2019 HHS final rule that held that issuers were not required to count enrollee manufacturer assistance toward annual OOP caps in cases where the manufacturer assistance was applied to brand-name drugs that had an “available and medically appropriate generic equivalent.” HHS said it issued that rule due to concern about possible market distortions if consumers chose higher-cost brand-name drugs when less expensive generics were available.59

In response to comments from issuers and insurers, HHS subsequently announced it would not enforce the 2019 rule and would modify the requirement as part of rulemaking for the 2021 plan year. Insurers had been concerned that, among other things, the 2019 rule was in conflict with federal requirements for the operation of HSA-eligible HDHPs, which mandate that HDHP

available at https://www.ncpdp.org/White-Papers.aspx. It is up to individual entities to decide whether to adopt the NCPDP recommendations.

56 CMS, “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2021; Notice Requirement for Non-Federal Governmental Plans,” 85 Federal Register 29230, May 14, 2020, at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/05/14/2020-10045/patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act-hhs-notice-of-benefit-and-payment-parameters-for-2021.

57 Health insurance plans that were in existence (in the non-group, small-group, or large-group market) and in which at least one person was enrolled on the date of the ACA’s enactment (March 23, 2010) are considered grandfathered and have a unique status under the ACA. As long as a plan maintains its grandfathered status, the plan has to comply with some but not all ACA provisions. CRS Report R44163, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s Essential Health Benefits (EHB).

58 Ibid., p. 29253. 59 CMS, “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2020,” 84 Federal Register 17544, April 24, 2019, at https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2019-08017/p-885.

Congressional Research Service

13

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

issuers disregard any provider discounts in determining whether enrollees meet plan deductible requirements.60

The final 2020 rule for the 2021 plan year states that issuers and group health plans have flexibility (subject to state law and other applicable requirements (if any)), to determine if and how to count manufacturer assistance, such as coupons, toward annual OOP limits. Plans that choose to impose limitations on manufacturer assistance must implement the limitations in a uniform, non-discriminatory manner. CMS encouraged issuers and health plans that limit manufacturer assistance to be transparent to enrollees by prominently providing information about their coupons/cost-sharing policies on websites and in brochures, plan summary documents, and other plan materials. According to CMS, “If we find that such transparency is not provided, HHS may consider future rulemaking to require that issuers provide this information in plan documents and collateral material.”61

2020 Medicaid Best Price Final Rule

In a final rule issued in December 202062 (which was later struck down in court, see below) CMS said that, beginning in 2023, it would count the value of patient assistance when calculating a manufacturer’s “best price” for the drug under the state-federal Medicaid program unless a manufacturer was able to demonstrate that the full value of a coupon or other assistance accrued to an individual, rather than to a payer, such as a private insurer.63

In general, pharmaceutical manufacturers that sell covered outpatient drugs through Medicaid are required to pay state Medicaid programs a basic rebate and, if they raise a drug’s price faster than inflation, an additional rebate.64 The basic rebate is determined by comparing each drug’s per unit average manufacturer price (AMP)65 to that drug’s per unit best price. The best price is the drug manufacturer’s lowest U.S. price any purchaser paid during a quarterly reporting period. The

60 CMS, “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2021; Notice Requirement for Non-Federal Governmental Plans,” 85 Federal Register 23921, May 14, 2020. According to CMS, Q&A–9 of IRS Notice 2004–50 states that the provision of drug discounts will not disqualify an individual from being an HSA-eligible individual if the individual is responsible for paying the costs of any drugs (taking into account the discount) until the deductible under the HDHP is satisfied. Thus, Q&A–9 of IRS Notice 2004–50 requires an HDHP to disregard drug discounts and other manufacturer and provider discounts when determining if the deductible for an HDHP has been satisfied, and only allows amounts actually paid by the individual to be taken into account for that purpose. CMS stated, therefore, that under this IRS policy, an issuer or sponsor of an HSA-qualified HDHP could be put in the position of complying with either the requirement under the 2019 final rule for limits on cost sharing in the case of direct support provided by drug manufacturers for a brand-name drug with no available or medically appropriate generic equivalent or the IRS rules for minimum deductibles for HDHPs, but potentially being unable to comply with both rules simultaneously. According to CMS, the 2019 final rule implied that in situations where a medically appropriate generic equivalent is not available, “group health plans and issuers are required to count such coupon amounts toward the annual limitation on cost sharing.” 61 Ibid, p. 29233. 62 CMS, “Medicaid Program; Establishing Minimum Standards in Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review (DUR) and Supporting Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) for Drugs Covered in Medicaid, Revising Medicaid Drug Rebate and Third Party Liability (TPL) Requirements,” 85 Federal Register 87048, December 31, 2020, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-12-31/pdf/2020-28567.pdf.

63 Ibid, p. 87000. 64 Social Security Act Section 1927(k)(3), Covered Outpatient Drug. 65 Social Security Act Section 1927(k)(1) defines the AMP as the average U.S. price manufacturers received for their product excluding specified price concessions when sold to retail community pharmacies.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 19 Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

basic rebate is either the greater of a specified percentage of AMP or the difference between the AMP and the best price.66

In its 2020 Federal Register notice outlining the final rule, CMS said that it had learned that some health plans, which are defined as providers for determining Medicaid best price, were using accumulator programs to apply patient assistance programs in a way that provided a financial benefit to the plan, rather than solely to the enrollee.67 For example, by imposing accumulator programs that (1) allow an enrollee to use a coupon but (2) do not count the value of the coupon toward annual OOP requirements, health plans effectively delay the point at which they must provide certain benefits to enrollees, which allows them to realize cost savings. According to CMS, such savings amount to a reduction in the price of a drug, which should be included in determining the Medicaid best price.

CMS set a January 1, 2023, implementation date for the final rule so that manufacturers would have time to develop technical systems to track payment assistance offers to determine whether coupons and other benefits were delivered exclusively to consumers. PhRMA sued HHS and CMS, contending that the rule was inconsistent with the Medicaid statute. PhRMA asserted that manufacturers did not have control over the development or implementation of accumulator programs, and that there was not a reliable method for drug manufacturers to determine whether a cost-sharing offer was provided exclusively to a consumer.68 In May 2022, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia struck down the final rule on the grounds that HHS had exceeded its authority.69

federal health care program items or services.65

Private Insurance

Commercial payers have varying policies regarding coupon use. A 2015 Pharmacy Benefits Management Institute survey found that some large employers (or the insurers they contracted with) limited the ability of employees covered under health plans they offer to redeem coupons on the grounds that the coupons interfered with price tiers and other cost-control strategies. Some large employers increased required coinsurance for drugs if a coupon was available.66

UnitedHealthcare bars enrollees from using co-payment coupons for certain drugs.67 Express Scripts, the nation's largest PBM, also has dropped drugs from its preferred formulary due partly to the availability of manufacturer co-payment coupons for the drugs.68

Some manufacturers may help patients get around plan prohibitions by using debit cards and rebate offers. For example, one company uses a case study to market its prescription-drug debit card. The case study notes reports that a manufacturer risked losing thousands of patients after a payer decided to bar co-payment cards for a rheumatoid arthritis drug and instead recommended that its enrollees use a less expensive generic drug. In response, the manufacturer adopted a debit card system, where patients paid the required co-payment at the pharmacy and were reimbursed after the point of the sale—usually within a few days. The debit card vendor reported that this approach resulted in a high patient retention rate.69

Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs

Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs Pharmaceutical manufacturers, state governments, and independent charities operate PAPs to help uninsured or underinsured individuals pay for prescription drugs. Many nongovernmental PAPs are set up as 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations to provide prescription drugs or financial subsidies to qualified patients.7070 501(c)(3) entities are exempt from federal income taxes and qualify to 66 Social Security Act Section 1927(c)(1)(C)(ii) defines best price to include cash discounts, free goods contingent on any purchase requirement, volume discounts, and rebates (other than the specified Medicaid rebates). Best price includes the lowest price available from the manufacturer to any U.S. purchaser, which includes with some exceptions a wholesaler, retailer, hospital, provider, HMO, nonprofit entity, or governmental entity.

67 CMS, “Medicaid Program; Establishing Minimum Standards in Medicaid State Drug Utilization Review (DUR) and Supporting Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) for Drugs Covered in Medicaid, Revising Medicaid Drug Rebate and Third Party Liability (TPL) Requirements,” 85 Federal Register 87000, December 31, 2020, p. 87408, at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/12/31/2020-28567/medicaid-program-establishing-minimum-standards-in-medicaid-state-drug-utilization-review-dur-and. Medicaid patients are not eligible for manufacturer-sponsored programs, but according to CMS the administration of these programs by commercial health plans and PBMs can affect the rebates that the Medicaid program receives from the manufacturer-sponsor of these programs. According to the Federal Register notice, when manufacturer-sponsored assistance does not accrue towards a patient’s deductible or OOP limits, a health plan is able to delay the application of its plan benefit to the patient to the detriment of the patient or consumer, thus generating savings for the plan.

68 Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Of America (PhRMA) v. Xavier Becerra, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Civil Action No. 1:21-cv-1395, May 21, 2021, at https://www.courthousenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/pharma-HHS.pdf.

69 Bloomberg Law, “Drugmakers Win Challenge to Medicaid Drug Price Rebate Rule,” May 17, 2022, at https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/drugmakers-win-challenge-to-medicaid-drug-price-rebate-rule. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Of America (PhRMA) v. Xavier Becerra, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Civil Action No. 1:21-cv-1395, May 17, 2022, at https://casetext.com/case/pharm-research-manufacturers-of-am-v-becerra-1.

70 See “What Is a 501(c)(3) Organization?”

Congressional Research Service

15

Prescription Drug Discount Coupons and Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs)

receive tax-deductible contributions.71 As such, pharmaceutical companies and other donors can deduct donations of inventory or cash to PAPs.72

Different types of PAPs include the following:73

Pharmaceutical Manufacturer PAPs. Many pharmaceutical makers distribute

prescription drugs to individuals through their own 501(c)(3) organizations, which often are set up as private foundations. Manufacturer PAPs provide drugs to people enrolled in private insurance and public health programs, and the uninsured. Drug manufacturers may contract with outside companies in administering their PAPs.74

Independent Charity PAPs. Independent charities operate PAPs that offer aid

such as financial assistance to uninsured consumers or underinsured consumers who cannot meet their health plans’ premiums or cost sharing, such as co-payments, coinsurance, and deductibles.

501(c)(3) entities are exempt from federal income taxes and qualify to receive tax-deductible contributions.71 As such, pharmaceutical companies and other donors can deduct donations of inventory or cash to PAPs.72

Different types of PAPs include the following:73

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturer PAPs. Many pharmaceutical makers distribute prescription drugs to individuals through their own 501(c)(3) organizations, which often are set up as private foundations. According to the nonprofit Foundation Center, as of 2015, pharmaceutical PAPs accounted for 7 of the 10 largest U.S grant-making foundations, as ranked by annual giving.74 Manufacturer PAPs provide drugs to uninsured individuals and to people enrolled in private insurance and public health programs. Drug manufacturers may contract with outside companies in administering their PAPs.75

- Independent Charity PAPs. Independent charities operate PAPs that offer aid such as financial assistance to uninsured consumers or underinsured consumers who cannot meet their health plans' premiums or cost sharing, such as co-payments, coinsurance, and deductibles. One such PAP, the Patient Access Network Foundation, ranks 21st among the largest 100 U.S. charities.76 Other large, independent charity PAPs include the HealthWell Foundation, the Caring Voice Coalition, the Patient Advocate Foundation, Patient Services, Inc., and Good Days from the Chronic Disease Fund.77 Some of the independent charity PAPs were established by health care consulting firms that work with drug manufacturers.78

- State PAPs (SPAPs). As of

2014, 19 state governments operated2021, CMS listed 20 state governments with 43 SPAPs that met certainCMS criteria.79criteria.75 The SPAPs generally serve uninsured residents or fill in the gaps in Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance coverage.80aimedtargeted at lower-income individuals and usually are the payer of last resort, meaning the SPAP will pay for drugs only after federal programs or any private insurance already has been billed. SPAP rules and coverage vary by state—someare targeted atfocus on seniors and someaton specific disease groups, such as people with HIV/AIDs. This reportmainly focusesconcentrates on the other two types of PAPsand will refer, and refers to the state programs as SPAPs rather than PAPs for clarity.

What Is a 501(c)(3) Organization?

501(c)(3) organizations qualify for federal tax-exempt status.8177 To qualify, a 501(c)(3) organization must be "“organized and operated exclusively"” for at least one of the exempt purposes listed in statute, which include charitable and educational purposes. Although the statute uses the term "“exclusively,"” this actually means the organization'’s activities must primarily be for

71 26 U.S.C. §§170, 501. 72 See also “How are PAP Donations Valued?” In addition, see HHS OIG, “New Special Advisory Bulletin Provides Additional Guidance on Independent Charity Patient Assistance Programs for Federal Health Care Program Beneficiaries,” May 21, 2014, at http://oig.hhs.gov/newsroom/news-releases/2014/charity.asp. 73 Definitions come from HHS OIG publications. 74 Outside administrators include Eversana, “Alleviate Patients’ Financial Burdens and Increase Speed to Therapy,” at https://www.eversana.com/solutions/integrated-commercial-services/affordability-programs/patient-assistance-programs/; and McKesson,“ Program Pharmacy Solutions for Biopharma From RxCrossroads,” at http://www.mckesson.com/manufacturers/pharmaceuticals/oncology-and-specialty-pharmaceutical-services/patient-assistance-programs-paps/.