Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Changes from October 6, 2016 to September 24, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Contents

USDA'sSeptember 24, 2020 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Research, Education, and Economics (REE) mission area funds bil ions of dollars annual y for biological, physical, and social Genevieve K. Croft science research that is related to agriculture, food, and natural resources. Four agencies Analyst in Agricultural carry out REE responsibilities: the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the National Policy Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), and the Economic Research Service (ERS). The Under Secretary for REE, who oversees the REE agencies, holds the title of USDA Chief Scientist and is responsible for coordinating research, education, and extension activities across the entire department. The Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS)—a staff office within the Office of the Under Secretary for REE—supports this coordination role. Discretionary funding for the REE mission area totaled approximately $3.4 bil ion in FY2020, and mandatory funding from the 2018 farm bil adds another $177 mil ion per year on average. USDA administers federal funding to states and local partners through its extramural research agency: NIFA. NIFA administers this extramural funding through capacity grants (al ocated to the states based on formulas in statute) and competitive grants (awarded based on a peer-review process). USDA also conducts its own research at its intramural research agencies: ARS, NASS, and ERS. Debates over the direction of public agricultural research and the nature of how it is funded(REE) Mission Area- Federal Funding

- Formula Funds vs. Competitive Grants

- Intramural vs. Extramural Funding

- Public and Private Funding

- Agricultural Research Supports Productivity

Figures

- Figure 1. USDA Agricultural Research Service Locations

- Figure 2. Land-Grant Colleges of Agriculture

- Figure 3. National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Budget

- Figure 4. Real U.S. Public and Private Agricultural R&D Expenditures

- Figure 5. Funders and Performers of U.S. Food and Agricultural Research in 2009

- Figure 6. U.S. Farm Commodity Yields, 1866-2008

Summary

The U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) Research, Education, and Economics (REE) mission area has the primary federal responsibility of advancing scientific knowledge for agriculture through research, education, and extension. USDA REE responsibilities are carried out by four agencies: the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), the Economic Research Service (ERS), and the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). USDA conducts its own research and administers extramural federal funding to states and local partners primarily through formula funds and competitive grants.

Discretionary funding for the REE mission area totaled $2.937 billion in FY2016, and mandatory funding from the 2014 farm bill adds another $120 million per year on average.

Debates over the direction of public agricultural research and the nature of its funding mechanism continue. Ongoing issues include whether federal funding is sufficient to support agricultural research, education, and extension activities; the different roles of extramural versus intramural research; and the implications of al ocating

extramural funds via capacity grants versus competitive grants.

Many groups believe that Congress shouldissues include the need, if any, for new federal funding to support agricultural research, education, and extension activities, and the implications of allocating federal funds via formula funds versus competitive grants. Many groups believe that Congress needs to increase support of U.S. agriculture through expanded federal support of research, education, and extension programs, whereas others believe that the private sector, not taxpayer

dollars, should be used to support these activities.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 5 link to page 5 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 7 link to page 8 link to page 12 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 21 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Contents

USDA’s Research, Education, and Economics Mission Area ................................................. 4

Agricultural Research Service ..................................................................................... 5

National Institute of Food and Agriculture ..................................................................... 5 National Agricultural Statistics Service ......................................................................... 6 Economic Research Service ........................................................................................ 6 Office of the Under Secretary of REE and Office of the Chief Scientist.............................. 9

Extramural Research Funding ........................................................................................... 9

Capacity Grants....................................................................................................... 10

Capacity Grants for Research ............................................................................... 10 Capacity Grants for Extension .............................................................................. 10

Competitive Grants .................................................................................................. 11

Intramural Research Funding .......................................................................................... 13 Research Funding Considerations .................................................................................... 13

Capacity Grants Versus Competitive Grants ................................................................. 13 Extramural Versus Intramural Funding ........................................................................ 15 Public Versus Private Funding ................................................................................... 16

Agricultural Research Supports Productivity ..................................................................... 19 Funding Agricultural Research: Looking Ahead ................................................................. 20

Figures Figure 1. Overview of USDA’s Research, Education, and Economics (REE) Mission

Area ........................................................................................................................... 4

Figure 2. USDA Agricultural Research Service Locations in the United States.......................... 7 Figure 3. Land-Grant Colleges and Universities ................................................................... 8 Figure 4. National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Budget ..................................... 12 Figure 5. Inflation-Adjusted U.S. Public and Private Agricultural Research and

Development Expenditures .......................................................................................... 17

Figure 6. Funders and Performers of U.S. Food and Agricultural Research in 2013 ................. 18 Figure 7. U.S. Agricultural Productivity: 1948-2015 ........................................................... 19

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 21

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

he federal government funds bil ions of dollars of agricultural research annual y. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Research, Education, and Economics (REE) mission

T area has the primary federal responsibility to advance scientific knowledge for

agriculture. REE programs and activities include the biological, physical, and social sciences

related broadly to agriculture, food, and natural resources.

The Under Secretary for REE, who oversees the REE agencies, holds the title of USDA Chief Scientist and is responsible for coordinating research, education, and extension activities within REE and across USDA. The Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS)—a staff office within the Office

of the Under Secretary for REE—supports this coordination role (7 U.S.C. §6971).

Other USDA agencies and other federal agencies also conduct research relevant to agriculture. For example, within USDA, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Animal and Plant

Health Inspection Service, and the U.S. Forest Service conduct some research activities. Outside of USDA, the National Science Foundation funds fundamental and applied research relevant to agriculture. This report focuses on USDA’s REE mission area and does not directly address

research activities or research funding outside of the mission area.

USDA’s Research, Education, and Economics Mission Area

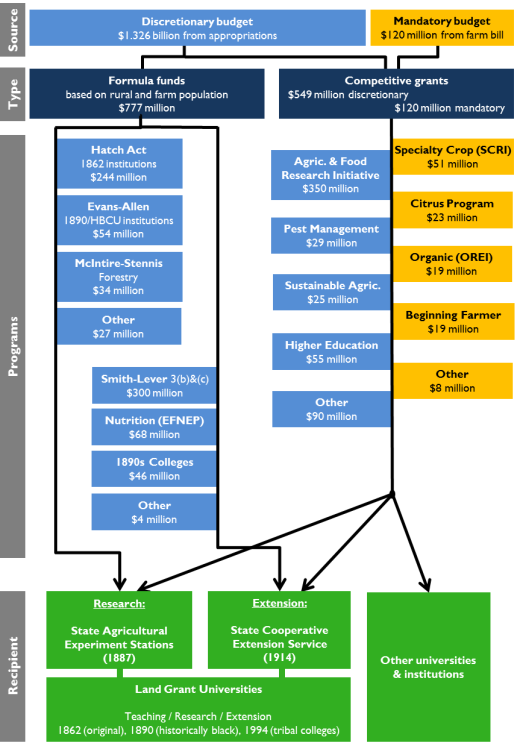

Figure 1. Overview of USDA’s Research, Education, and Economics (REE) Mission

Area

(FY2020 discretionary budget authority)

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS), using U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and appropriations committee information. Amounts are FY2020 budget authority. For program details, see USDA’s Congressional Budget Justification, at http://www.obpa.usda.gov.

REE consists of four agencies (see Figure 1): the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), National

Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Economic Research Service (ERS), and National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). Al four agencies are headquartered in the Washington, DC,

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 7 link to page 8 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

metro area.1 Their mission area includes intramural and extramural roles in agricultural research, statistics, extension, and higher education. Most REE activities are funded through annual discretionary appropriations. In FY2020, the REE discretionary budget totaled approximately $3.4 bil ion. Mandatory funding authorized in the 2018 farm bil adds approximately $177

mil ion per year on average.2

Agricultural Research Service ARS is USDA’s chief intramural scientific research agency: it employs federal scientists to

conduct research and is responsible for leading the national agricultural research effort. It operates approximately 90 research facilities in the United States and abroad, many of which are co-located with land-grant universities (Figure 2). ARS also operates the National Agricultural Library located in Beltsvil e, MD, the world’s largest agricultural research library and a primary

repository for food, agriculture, and natural resource sciences information.

ARS has about 5,000 permanent employees, including approximately 2,000 research scientists.3 It is led by an administrator, who is a member of the Senior Executive Service. ARS organizes its research into 15 national programs to coordinate the nearly 700 research projects that ARS

scientists carry out. This research spans efficient and sustainable food and fiber production, development of new products and uses for agricultural commodities, development of effective

pest management controls, and support of USDA regulatory and technical assistance programs.

National Institute of Food and Agriculture NIFA is USDA’s principal extramural research agency: it leads and funds external research, extension, and educational programs for agriculture, the environment, human health and wel -being, and communities. NIFA leadership includes developing and implementing grant programs

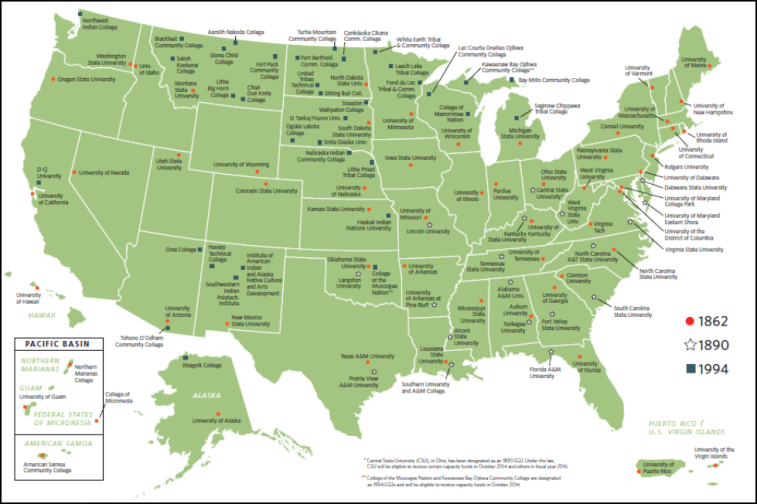

that fund extramural activities. NIFA provides federal funding for projects conducted in partnership with land-grant universities in al 50 states and several U.S. territories, affiliated State Agricultural Experiment Stations (SAESs), schools of forestry and veterinary medicine, the Cooperative Extension System (CES), other research and education institutions, private organizations, and individuals.4 The land-grant university (LGU) system includes three types of

institutions: the 52 original colleges (known as the 1862 Institutions) established through the Morril Act of 1862, the 19 historical y black colleges (known as the 1890 Institutions) established through the Second Morril Act of 1890, and the 36 tribal colleges (known as the 1994 Institutionsdollars, should be used to support these activities.

USDA's Research, Education, and Economics (REE) Mission Area

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) combines its research activities into the Research, Education, and Economics (REE) mission area. The mission area is composed of four agencies with the federal responsibility to advance scientific knowledge for agriculture. Activities include the biological, physical, and social sciences related broadly to agriculture, food, and natural resources, delivered through research, statistics, extension, and higher education (Table 1).

Table 1. USDA's Research, Education, and Economics (REE) Mission Area

(FY2016 discretionary budget authority)

|

Function |

Entity |

Description |

|

Intramural Federal research |

Agricultural Research Service (ARS) $1.144 billion salaries and expenses + $212 million buildings & facilities |

ARS conducts research and disseminates information related to crop and livestock production and protection, human nutrition, food safety, rural development, natural resource management, and conservation. Emphasis is on national and regional problems, including higher-risk and long-term research such as plant and animal genome programs. Workforce of about 5,400 full-time employees located across about 100 research stations. |

|

National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) $168 million |

NASS collects and compiles statistics related to U.S. agriculture (e.g., Census of Agriculture, crop forecasts, estimates of farm prices). Workforce of about 1,000 full-time employees; offices in DC, 45 states, and Puerto Rico. |

|

|

Economic Research Service (ERS) $85 million |

ERS provides economic and policy analysis to inform public and private decision making related to food, farming, natural resource management, agricultural markets, and rural development. Workforce of about 365 full-time employees entirely located in Washington, DC. |

|

|

Extramural Federal funding of state and other institutions |

National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) $1.326 billion |

NIFA leads and funds external research, extension, and educational programs for agriculture, the environment, human health and well-being, and communities. Provides grants and partnerships with the land-grant university system and other organizations that work at the state and local level. Workforce of about 400 employees. Federal funding through competitive grants and "formula funds" (the latter based on each state's farm and rural population, with matching fund requirements from the states). |

|

Administrative |

Under Secretary for Research, Education and Economics Chief Scientist Research, Education, and Extension Office (REEO) $893,000 |

The Under Secretary is designated as the Chief Scientist and leads the REEO, which coordinates USDA programs, sets priorities, and aligns scientific capacity across the four agencies. Six divisions: (1) renewable energy, natural resources, and environment; (2) food safety, nutrition, and health; (3) plant health and production; (4) animal health and production; (5) agricultural systems and technology; and (6) agricultural economics and rural communities. |

|

REE total |

$2.937 billion |

Source: CRS, using USDA and appropriations committee information. Amounts are FY2016 budget authority. For program details, see USDA's Congressional Budget Justification at http://www.obpa.usda.gov.

Federally funded intramural research is intended in part to address issues of national importance and promote basic research, regional coordination, and spillover.1 Federally funded extramural research activities are decentralized and are often regionally specific and/or applied in nature. The federal-state research system also supports USDA's regulatory programs in the areas of meat, poultry, and egg inspection; foreign pest and disease exclusion; and control and eradication of crop and livestock threats, among other things.

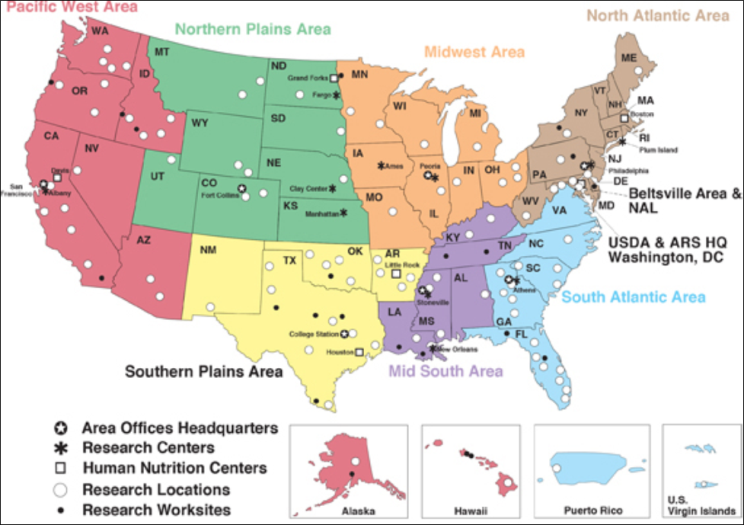

Although all four USDA research agencies are headquartered in Washington, DC, much of the work is executed through a set of agency field stations and a network of university partners throughout the United States that operate at the state and local levels. The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) has about 100 research centers and work locations across the United States, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands (Figure 1). The National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) partners with colleges of agriculture at land-grant universities in 50 states and eight U.S. territories, affiliated state agricultural experiment stations (SAESs), schools of forestry and veterinary medicine, and the Cooperative Extension system.2 These colleges include the traditional land-grant colleges of agriculture established by the Morrill Act of 1862 ("1862 institutions"), 19 historically black colleges of agriculture ("1890 institutions," HBCUs) that were created by the Second Morrill Act of 1890, and 31 Native American colleges (referred to as tribal colleges) that gained land-grant status in 1994 (Figure 2). The Economic Research Service (ERS) is the only REE agency based entirely in Washington, DC.

The House and Senate Agriculture committees are the committees of jurisdiction for the authorizing statutes and oversight of agricultural research, education, and extension programs. In recent years, Congress has modified agricultural research policy in the "farm bill," most recently in 2014 (P.L. 113-79, Title VII). Annual appropriations bills and hearings provide more frequent opportunities for oversight and determination of funding.

Federal Funding

The majority of federal funding for agricultural research, education, and extension activities is from annual discretionary appropriations in the Agriculture and Related Agencies appropriations bill.3 In FY2016, discretionary funding for the entire REE mission area totaled $2.937 billion (Table 1). A subset of research programs, especially within NIFA, is provided with mandatory funding—such as for specialty crops or organic agriculture that were created in the 2008 and 2014 farm bills. The 2014 farm bill provides an average of $120 million per year of mandatory funding to agricultural research (Figure 3).4

Intramural research at federal agencies (ARS, NASS, and ERS) is funded directly with discretionary appropriations to pay salaries and expenses of federal employees, to conduct research, and to build and maintain facilities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extramural research that is sponsored by NIFA is administered by a relatively small resource/LGU-Map-03-18-19.pdf.

CRS-8

link to page 12 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Office of the Under Secretary of REE and Office of the Chief Scientist The Office of the Under Secretary of REE reports to the Secretary of Agriculture. This

administrative office consists of the Under Secretary for REE and a few staff members.

OCS is a component of the Office of the Under Secretary of REE. In 2008, Congress created

OCS when it established the dual role of the Under Secretary for REE as the USDA Chief Scientist (7 U.S.C. §6971(c)). OCS supports the USDA Chief Scientist in coordinating USDA research programs, setting priorities, and aligning scientific capacity across the four REE

agencies and the department. Congress identified six OCS divisions to be led by division chiefs:

Renewable energy, natural resources, and environment; Food safety, nutrition, and health; Plant health and production; Animal health and production; Agricultural systems and technology; and Agricultural economics and rural communities.

The division chiefs (in practice, known as senior advisors) hold their roles for a period of time and may be appointed by means of a flexible hiring authority, including term, temporary, or other appointment; detail; reassignment from another civil service position; and assignment from the states under the Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA, 7 U.S.C. §3374).12 Other OCS staff, who

may be hired on a permanent basis, implement additional OCS leadership duties described in statute (7 U.S.C. §6971(e)(4)). In recent years, these positions have included the OCS director and deputy director, the departmental scientific integrity officer, the veterinary science policy

officer, and the senior advisor for international affairs.

Since its establishment, OCS has not received an independent appropriation. Rather, the four REE agencies have funded it via interagency agreement. The FY2021 President’s budget request for the Office of the Secretary includes the first separate request for OCS, in the amount of $6 mil ion

and 29 staff years.13

Extramural Research Funding Extramural research that NIFA sponsors is administered by a relatively smal cadre of employees who are funded by a small smal portion of NIFA'’s appropriation for salaries and expenses. The vast majority of the NIFA appropriation is available for extramural research grants that are made primarily through two types of funding: formula fundscapacity grants and competitive grants (see Figure 34). The following sections introduce some USDA extramural funding concepts. For more detailed

information on federal funding of the LGU system, see CRS Report R45897, The U.S. Land-

Grant University System: An Overview.

12 7 U.S.C. §6971(E)(3)(a). 13 USDA, “ Explanatory Notes—Office of the Secretary,” President’s Budget Request—FY2021, 2020, pp. 1-9 to 1-10. T he House-passed FY2021 Agriculture appropriation s bill (H.R. 7608, Div. B) did not include the funding requested for the Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS). As of September 2020, the Senate has not yet marked up its FY2021 bill.

Congressional Research Service

9

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Capacity Grants Capacity grants for research, education,).

1. Formula fundsfor researchand extension are distributed to land-grant colleges (1862, 1890, and 1994institutionsInstitutions), schools of forestry, and schools of veterinary medicine usingcalculationsformulas that are set in statute. Theamountamounts provided to each institutionisare determined by census-based statistics that change infrequently.Research priorities at each college may be influenced at the university level (7 U.S.C. 301 et seq.). Two accounts provide most of the formula funding.5TheEach recipient institution determines the research priorities for the capacity funds it receives. Two accounts provide most of the capacity grant funding: Hatch Act funding and Smith-Lever funding.14 Capacity Grants for Research The Hatch Act of 1887 (7 U.S.C. §301) authorizes research funding at the state agricultural experiment stations (SAESs).associated with the 1862 Institutions. In 1955, Congress amended the Hatch Actin 1955to distribute the appropriation according to a formula based on each state'’s farm and rural population. The Hatch Act requires one-to-one nonfederal matching funds, general y provided from state budgets, and it requires each state to use 25% of Hatch Act funds to support multistate or regional research. The 1890 Institutions get similar funding through Evans-Al en Act research funding (7 U.S.C. §3222). These grants also require one-to-one nonfederal matching funds. Unlike the Hatch Act, the Evans-Al en Act al ows states to apply for a waiver for up to 50% of the matching requirement.15 Additional capacity grant programs support forestry, veterinary, and other research at land-grant institutions. Similar to the Hatch Act and Evans-Al en Act, these funds are distributed among states with eligible institutions according to formulas in statute. These criteria are specific to each program. Further, interest from the Tribal College Endowment Fund (7 U.S.C. §301 note) is distributed to eligible institutions according to formulas in statute. The Hispanic-Serving Agricultural Colleges and Universities Fund (7 U.S.C. §3243), designed in a similar way, has yet to be funded by Congress. Capacity Grants for Extension The Smith-Lever Act (7 U.S.C. §341)and rural population in the U.S. Census (7 U.S.C. 301). The Hatch Act also requires dollar-for-dollar matching funds from state budgets, but most states appropriate three to four times the federal allotment.6 The act also requires each state to use 25% of its Hatch Act funds to support multi-state or regional research. HBCUs get similar funding through Evans-Allen research grants and 1890s capacity building grants.The Smith-Lever Actauthorizes cooperative extension funding to the states using statutory formulas and requiring nonfederal matching funds. Smith-Lever Act funds support state participation in the Cooperative Extension System through the 1862 Institutions.16 The 1890 Institutions get similar extension funding through Section 1444 funding (7 U.S.C. 321-329), with distribution based on a formula in statute, and a nonfederal matching funds requirement.17 14 Additional details are available in the USDA Budget Summary and Explanatory Notes for NIFA, available at http://www.obpa.usda.gov. 15 While granting a waiver may allow federal funding to continue to flow to a historically Black college or university (HBCU) if a state does not meet the matching requirement, such waivers reduce the resources available to these historically Black institutions. See Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, Land-Grant But Unequal: State of One-to-One Match Funding for 1890 Land-Grant Universities, September 2013, at http://www.aplu.org/library/land-grant -but-unequal-state-one-to-one-match-funding-for-1890-land-grant-universities/file. 16 NIFA, “Cooperative Extension System,” at https://nifa.usda.gov/cooperative-extension-system. 17 Section 1444 refers to Section 1444 of the National Agricultural Research, Extension, and T eaching Policy Act of 1977 (T itle XIV of P.L. 95-113), which established these grants. Congressional Research Service 10 link to page 12 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues Competitive Grants NIFA awards competitive grants using a peer-reviewed merit selection process. It makes awards to fundnonfederal matching requirements similar to the Hatch Act (7 U.S.C. 341). Federal funding supporting forestry and veterinary programs at the land grant institutions also is distributed among the institutions according to formulas, but these have different criteria than the Hatch Act and Smith-Lever Act formulas.2. Competitive grantsare awarded using a peer-reviewed merit selection process. Activities includefundamental and applied research, extension, and higher education activities, aswell as for projects that integrate research, education, and extension functionswel as projects that integrate these activities. Competitive programs are designed to enable USDA to attract a wide pool of applicants to work on agricultural issues of national or regional interest and to select the best quality proposals submitted by highly qualified individuals, institutions, or organizations (7 U.S.C. §450i(b)). Competitive grants are primarily funded with discretionary appropriations, but some also receive mandatory funding from the farmbillbil (Figure34).

The many NIFA competitive grant programs focus on aspects of agricultural research, extension, and

education.18

The Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI) is NIFA'’s flagship competitive grants program. It funds basic and applied research, education, and extension to colleges and universities, agricultural experiment stations, and other organizations conducting research in priority areas that are established partiallypartial y in the farm billbil . The 2008 farm bill bil (P.L. 110-246) mandated that AFRI allocateal ocate 60% of grant funds for basic research and 40% for applied research. At

research.19 Further, at least 30% of total funds must be used to integrate research with education

and/or extension activities.

Formula Funds vs. Competitive Grants

Policymakers continue to debate the appropriate role and implications of various funding mechanisms for agricultural research. At the federal level, this debate entails formula funding versus external peer-reviewed competitive grant funding. Those wanting to focus on agricultural research efficiency often call for more competitive grants to allocate limited federal resources.

Two historically influential reports published by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS)7 and the Rockefeller Foundation8 argued that the agricultural research of 30-40 years ago had become overly focused on applied research rather than cutting-edge basic research, and both reports recommended shifting to more competitive funding rather than formula funding of the state agricultural experiment stations (SAESs).

The creation of a new, separate grant-making agency within USDA that was solely responsible for administering competitive grants programs in agricultural research and extension was one of the recommendations that came out of a National Academy of Sciences 2000 report looking at the efficacy of the National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program.9 In July 2004, a USDA task force advocated for a revised extramural research agency (what is now NIFA) modeled on the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.29 The report expressed that

this agency should accomplish its mission primarily through administering competitive grants to

support high-caliber, fundamental agricultural research.

In recent years, the debate over the optimal balance of competitive versus capacity-funded

research has continued. In 2012, the President’National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF).10 It believed that NIFA should accomplish its mission primarily through administering competitive peer-reviewed grants that support and promote high-caliber, fundamental agricultural research.

In its 2012 report, the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) recommended a continued focus on increasing the proportion of research funds

awarded competitively, for both extramural and intramural research.30

Some view the choice of funding mechanism as important because it can influence who conducts the research, where it takes place, and what type of research is performed. On the one hand, some believe that the competitive, peer-reviewed process is advantageous because it draws onawarded competitively.11

The choice of funding mechanisms is viewed by some as important because it is thought to determine where and by whom the research is conducted, and the type of research performed. On the one hand, the competitive, peer-reviewed process is thought to have an advantage because a wider pool of eligible candidatespool of candidates is eligible to apply for funding (e.g., grant recipients are not limited to land-grant institutions or SAESs), and it is thought to engage the best and brightest minds in addressing challenges facing the agriculture sector.

At the same time, the agricultural community widely acknowledges that USDA-funded research has an important role to play, whether carried out intramurally (e.g., ARS) or through formula funds. Census-based formulas and nearly constant appropriations has meant that states receive a predictable allocation every year. Although all federal sources account for 30% or less of

26 National Academy of Sciences (NAS), Report of the Committee on Research Advisory to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1972).

27 NAS, National Research Initiative: A Vital Competitive Grants Program in Food, Fiber, and Na tural-Resources Research (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000), at http://www.nap.edu/catalog/9844.html.

28 P.L. 107-171, §7404. T he task force was also required to review ARS. 29 USDA, Research, Education, and Economics T ask Force, National Institute for Food and Agriculture: A Proposal, July 2004, at http://www.ars.usda.gov/sp2userfiles/place/00000000/national.doc.

30 President’s Council of Advisors on Science and T echnology (PCAST ), Report to the President on Agricultural Preparedness and the Agriculture Research Enterprise, December 2012, at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/pcast_agriculture_20121207.pdf. PCAST is an advisory board composed of individuals and representatives from sectors outside the federal government with diverse perspectives and expertise that advises the President on science, technology, education, and innovation policy. For more information on PCAST , see CRS Report R43935, Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP): History and Overview.

Congressional Research Service

14

link to page 18 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

SAESs) and can engage the “best and brightest minds” in addressing chal enges facing the

agriculture sector, irrespective of their home institutions.

At the same time, others argue that capacity grants provide stable funding to institutions and

al ow for long-term research and planning that can yield needed agricultural insights.31 Census-based formulas and nearly constant appropriations have meant that states receive a predictable al ocation every year. Although federal capacity grants may provide a fraction of the total funding for the SAESs, SAESs traditional y use them to support staff salaries andfor the experiment stations (including grants from non-research agencies within USDA and from other federal departments), the reliability of the formula funds has resulted in them traditionally being used to support the core ongoing research programs of the state agricultural experiment stations, which the core ongoing

research programs that underpin academic programs at many universities (Figure 5).

Studies have shown that funding through competitive grants tends to 6).32

Studies comparing capacity and competitive grants have shown that competitive grants tend to favor basic research, reach a greater proportion of non-landmore nonland grant universities, and arebe concentrated among fewer states than funding that is allocated by statutory formula funds.12 Statesstates.33 General y, states with large agricultural production and top-ranked academic programs in

biology and agricultural sciences were generallyare more competitive and receive larger shares of competitively

al ocated federal grants.

Other studies have indicated that federal capacity funding has a larger positive more competitive and more successful in receiving larger shares of federal funds allocated as competitive grants.

Other studies have shown that federal formula funding has a larger impact on impact on

agricultural productivity over the longer long-term than federal competitive grants and contracts.13 The rationale is that federal-level research is.34 These studies assert that the steady funding that cancapacity grants provide support core or foundationand foundational research and is best able to take on higher-risk and long-term projects of national importance, such as deciphering plant and animal genomes, conducting longitudinal studies on human nutrition, and measuring and analyzing current and historical socioeconomic factors in the U.S. food and fiber sector. Proposals that address problems of concern to an entire state or region, and/or are multi-disciplinary, are typically underfunded in a national competitive-grant process, despite the fact that such research problems are considered by many to be of critical concern and may have a large net social payoff to the agricultural sector.

Intramural vs. Extramural Funding

ARS is the principal in-house or intramurally funded research arm of the USDA. Many believe that maintaining some level of federally funded internal research allows ARS to fill facilitate high-risk and long-term projects of national importance. They also assert that research addressing multidisciplinary problems and local, state, and regional concerns is typical y underfunded in a national competitive-grant process. Many consider that such research areas are

of critical concern and that research addressing them may yield a large net social payoff to the

agricultural sector.

Extramural Versus Intramural Funding Another consequential policy consideration is the balance of USDA extramural vs. intramural research funding. In recent years, approximately 45% percent of funds appropriated for the REE agencies has gone to NIFA, USDA’s extramural funding agency. About 47% of the total has gone

to ARS, USDA’s principal in-house scientific research agency.

Many believe that intramural research at ARS al ows the federal government to fil an important niche that is not met by industry or other institutions. Specifically, someSpecifical y, they believe that intramural research is best to address research problems of national and long-term priority, such as. Such topics include adaptation to climate change and extreme weather events; conservation and improvement

of plant and animal genetic resources; research and vaccine development for foreign animal diseases; and soil and water resource management. Addressing some of these topics, ARS

31 For a NIFA-commissioned external evaluation of NIFA capacity funding, see S. T ripp et al., Quantitative and Qualitative Review of NIFA Capacity Funding , T EConomy Partners, LLC, March 2017, at https://www.nifa.usda.gov/resource/nifa-capacity-funding-review-teconomy-final-report.

32 See Donald A. Holt, “Agricultural Research Management in US Land-Grant Universities – T he State Agricultural Experiment Station System,” in Gad Loebenstein and George T hottappilly (eds), Agricultural Research Management, 2007, Springer, Dordrecht. 33 Kelly Day Rubenstein et al., “Competitive Grants and the Funding of Agricultural Research in the United States,” Applied Econom ic Perspectives and Policy, vol. 25, no. 2 (2003), pp. 352-368.

34 See Wallace E. Huffman et al., “ Winners and Losers: Formula versus Competitive Funding of Agricultural Research,” Choices, vol. 21, no. 4 (2006); and Wallace E. Huffman and Robert E. Evenson, “ Do Formula or Competitive Grant Funds Have Greater Impact on State Agricultural Productivity,” Am erican Journal of Agricultural Econom ics, vol. 88, no. 4 (November 1, 2006), pp. 783-798.

Congressional Research Service

15

link to page 17 link to page 17 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

manages the Long-Term Agroecosystem Research Network (LTAR)35 and national collections of plant, animal, microbial germplasm (i.e., genetic resources).36 ARS is to also manage the National

Bio and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF).37

of plant genetic resources, surveillance and monitoring of national and regional disease outbreaks, soil and water resource management, and adaptation to increasing climate variability and extreme events. On the other hand, some believe that ARS scientists have an unfair advantage in competing with competitive advantage over other agricultural scientists, who do not have an endowed source of support like the federal budget for core research expenditures.

Public andThe intramural statistical and social science agencies—NASS and

ERS—may not raise the same concerns, with their more limited budgets, staffing, and scopes.

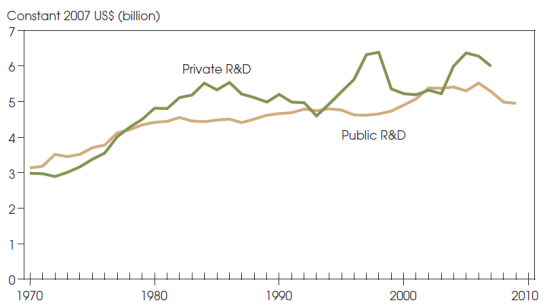

Public Versus Private Funding Private Funding

A recurring policy issue is whether more federal spending should be providedthe federal government is providing sufficient funding for agricultural research, education, and extension. A related issueconcern is the role of publicly funded research within the context

of al agricultural research performed with public and private funding.

Public funding for agricultural research—including funding from USDA, other federal agencies, and the states—has changed over time. It grew steadily from the 1950s to the late 1970s, when

adjusted for inflation, and then remained relatively constant into is the role of publicly funded research in context with privately funded research.

Over the long run, and adjusted for inflation, public funding for agricultural research grew steadily from the 1950s to the late 1970s, and remained basically constant from the end of the 1970s through the 1980s (Figure 4). There was a marked rise in public funding5). Public funding rose from 1998 through 2001, at a time of a budget surplus. One-time, supplemental funding for anti-terrorism activities increased funding in the several years after 2001. Funding levels peaked in FY2010, but began declining in FY2011 as Congress cut federal spending.14 As a result of a relatively flat or declining USDA research budget surplus. In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, supplemental funding for anti-terrorism activities added to federal funding of agricultural research in FY2002 (P.L. 107-117) and FY2003 (P.L. 108-11), although total public funding declined from previous years.38 Overal public funding of agricultural

research declined each year from 2002 to 2014, with the steepest declines from 2009 to 2010 and from 2012 to 2013, as Congress eliminated earmarks and cut federal spending through budget sequestration and other means.39 As a result of a relatively flat or declining USDA research budget, funding from other federal agencies, such as NIH and NSF, has accounted for an

increasing portion of federal support for agricultural research.

Funds

Research and development funds from private industry for agricultural research also generally have increased since the 1970s (Figure 4). This includesand food have grown since the 1970s, more than doubling between 2003 and 2014 (Figure 5). This funding includes investments in public-private partnerships that can facilitate technology transfer and at the

same time help to supplement federal and state research support. Over the long term, private-sector spending on agricultural research has continued to grow, while public spending has

stagnated or declined in constant dollars.

35 ARS, “T he LT AR Network,” at https://ltar.ars.usda.gov. 36 ARS, “Genetic Resource Collections,” at https://www.ars-grin.gov/Pages/Collections. 37 USDA, “National Bio and Agro-defense Facility,” at https://www.usda.gov/nbaf. 38 P.L. 107-117 transferred funds from the Emergency Response Fund created in 2001 (P.L. 107-38) to various agencies, including USDA, in FY2002.

39 Universities reported that sequestration negatively impacted their research, due to widespread delays and reduced activities. See Association of American Universities, Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, and T he Science Coalition, Survey on Sequestration Effects—Selected Results from Private and Public Research Universities, November 11, 2013, at https://www.aau.edu/key-issues/survey-sequestration-effects-selected-results-private-and-public-research-universities. Earmarks (congressionally directed spending) also were a common means of targeting agricultural research appropriations to specific universities or projects (see “ Earmarks” in CRS Report R40721, Agriculture and Related Agencies: FY2010 Appropriations). Congressional Rules eliminated these after FY2010.

Congressional Research Service

16

link to page 18

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Figure 5. Inflation-Adjusted U.S. Public and Private Agricultural Research and

Development Expenditures

1970-2014, in 2013 constant US$ (bil ions)

Source: CRS, from data provided at Economic Research Service (ERS), “Agricultural Research Funding in the Public and Private Sectors,” accessed June 5, 2020, at httpssupport. Private-sector spending on agricultural research has grown faster than publicly funded research and development over the long term.

|

|

|

Figure 5 ://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/agricultural-research-funding-in-the-public-and-private-sectors. Notes: ERS notes these data derive from the National Science Foundation, USDA’s Current Research Information Systems, and various private sector data sources. Data are adjusted for inflation using an index for agricultural research spending developed by ERS. Data as of February 2019.

A chief concern some have about privately funded research is the extent to which novel research discoveries are shared. Another common concern is whether private funders would choose to

fully develop research discoveries with the potential for large social benefits, but limited near-

term profit potential.

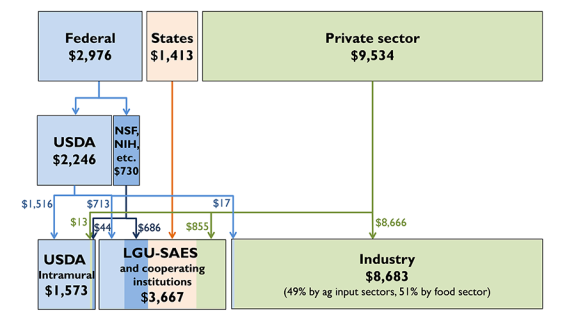

Figure 6 shows the many funders of agricultural research, the scale of their contributions, and the

destinations for that funding, using 2013 data. In 2013, of the $16.3 bil ion. In 2009, out of $13.9 billion of agricultural research funding, about 6876% came from the private sector ($9.5 billion) and about 62% remained in the private sector ($8.7 billion). State governments passed through $1.4 billion to land-grant universities (LGUs) or state agricultural experiment stations (SAESs), which incidentally received a majority of their funding from combined federal sources in nearly equal shares from USDA, other federal agencies such as NSF and NIH, and the private sector.15 USDA intramural research by ARS, ERS, and NASS accounted for about 11% of total agricultural research spending in 2009.

Some observers are concerned that both the increase in non-USDA public funding (e.g., NSF and nongovernmental sources ($12.4 bil ion) and about 72% of the research and development performed with these funds was performed by industry ($11.8 bil ion). State governments passed through $1.1 bil ion to LGUs and SAESs.40 The LGUs and SAESs received about 42% of their funding ($1.3 bil ion) from federal sources, including USDA,

NSF, and NIH.41 USDA intramural research by ARS, ERS, and NASS accounted for about 9% of

total agricultural research spending in 2013.

40 T his is less than the $1.4 billion they provided in 2009. 41 T his accounting is for the research function only and excludes funding for extension and education.

Congressional Research Service

17

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Figure 6. Funders and Performers of U.S. Food and Agricultural Research in 2013

(dol ars in mil ions)

Source: CRS, from Matthew Clancy, Keith Fuglie, and Paul Heisey, “U.S. Agricultural R&D in an Era of Fal ing Public Funding,” Amber Waves, November 10, 2016, at https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/november/us-agricultural-rd-in-an-era-of-fal ing-public-funding. Notes: Funding data are for calendar year 2013. Includes research and development funding only; it does not include extension or education funding. 1. This category includes the 1862 and 1890 land-grant universities (LGUs) and State Agricultural Experiment

Stations (SAESs); veterinary schools, forestry schools, and other U.S. col eges and universities receiving agricultural research funding from USDA. Data are based on 2013 state-level reporting (state reporting standards changed in 2010).

2. This amount ($682 mil ion) consists of research grants and contracts from private companies; research

grants from farm commodity groups, philanthropic foundations, individuals and other organizations; and revenue and fees from the sale of products, services, and technology licenses.

Some observers are concerned that both the increase in non-USDA public funding (e.g., NSF, NIH) and the increase in private funding might cause the focus of agricultural research to shift away from what some have traditional y considered away from the U.S. agricultural sector'’s highest

priorities and needs.42 They believeassert that such a shift could hamper the nation'’s ability to remain at the cutting-edge with regard to new innovations,; to be competitive in a global market,; and to cope with long-term challengeschal enges such as pest and disease outbreaks, climate change, and natural resource management. Some observers are also concerned about the decline in state funding of agricultural research. This decline has contributed to the overal decline in the share of public

funding of U.S. agricultural research.43

42 For an analysis of the different roles of public and private agricultural research, see John King, Andrew T oole, and Keith Fuglie, The Com plem entary Roles of the Public and Private Sectors in U.S. Agricultural Research and Developm ent, ERS, Economic Brief (EB) 19, September 2012. 43 See Matthew Clancy, Keith Fuglie, and Paul Heisey, “U.S. Agricultural R&D in an Era of Falling Public Funding,”

Congressional Research Service

18

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Irrespective of the amount of agricultural research funding, some analysts have noted that USDA’s increased engagement with the private sector on research and technology transfer since

the 1980s may fuel innovation and reduce redundancies.44

resource management.

Agricultural Research Supports Productivity

Agricultural Research Supports Productivity Public investment in agricultural research has been linked to productivity gains and economic growth.16 Studies45 Studies have consistently reportreported high social rates of return (20%-60% annually) from public agricultural research.17on public agricultural

research investments—on the order of 20%-60%.46 The rate of return may depend on the type of research conducted (basic vs. applied), the duration of the research investment, and the specific

topic under study.

Figure 7. U.S. Agricultural Productivity: 1948-2015

Source: Sun Ling Wang et al., Agricultural Productivity Growth in the United States: Measurement, Trends, and Drivers, ERR-189, Economic Research Service, July 2015. Notes: Data are expressed with an index that is calculated relative to the data in 1982, where data in 1982 are set to equal 100. As shown, from 1948 to 2015, U.S. agricultural productivity continued to grow, while the real price of agricultural outputs tended to decline.

Am ber Waves, November 10, 2016, at https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/november/us-agricultural-rd-in-an-era-of-falling-public-funding/.

44 Keith O. Fuglie and Andrew A. T oole, “T he Evolving Institutional Structure of Public and Private Agricultural Research,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics, vol. 96, no. 3 (January 20, 2014) pp. 862-883. 45 Keith O. Fuglie and Paul W. Heisey, Economic Returns to Public Agricultural Research, ERS, EB-10, September 2007, at https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=42827. 46 Social rates of return compare the benefits (including economic benefits and gains to consumers and society at large) to public costs. Matthew Clancy, Keith Fuglie, and Paul Heisey, “ U.S. Agricultural R&D in an Era of Falling Public Funding,” Am ber Waves, November 10, 2016, at https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/november/us-agricultural-rd-in-an-era-of-falling-public-funding.

Congressional Research Service

19

link to page 19 Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

Agricultural economists assert that advances in agricultural research and extension were critical to the huge productivity gains in the United States after World War II.47 Total factor productivity (TFP) is a key measure for overal agricultural productivity; it measures outputs (e.g., crop yields, labor productivity) per total unit of inputs (e.g., land, labor, fertilizers). ERS has estimated TFP of U.S. agriculture has increased an average of 1.38% annual y from 1948 through 2015, c ompared to 0.1% annual growth of total inputs (Figure 7).48 Advances in basic and applied agricultural sciences—such as disease-resistant crop varieties,

efficient irrigation practices, and improved marketing systems—are widely considered fundamental to increasing agricultural yields, farm sector profitability, competitiveness in international agricultural trade, and improvements in nutrition and human health.

Funding Agricultural Research: Looking Ahead In a constrained budget environment, agriculture competes for federal funding against other federal priorities. Within the funding al ocated for agriculture, agricultural research competes for

funding against other agricultural programs, such as conservation, farm income and risk management programs, food safety inspection, rural development, and domestic and foreign food aid programs.49 Historical y, Congress has not solely prioritized funding for agricultural research, education, and extension activities but has also prioritized funding for programs designed to

provide more immediate benefits to farmers, such as income support and crop insurance.

Stakeholders have varying perspectives on the needs for federal investments in agricultural research. Some want more public spending on agricultural research to maintain U.S. competitiveness and to increase agricultural productivity and innovation in the face of growing

food demand and increasing agricultural chal enges (e.g., pests, natural disasters).50 Some argue (basic vs. applied), the duration of the research investment, and the specific commodity being studied.

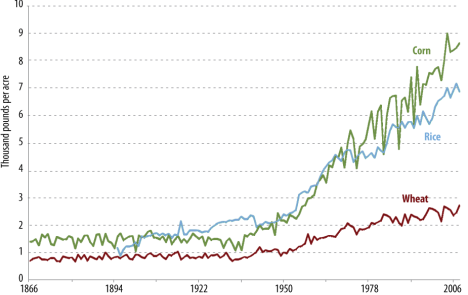

Advances in agricultural research and extension were critical to the huge productivity gains in the United States after World War II (Figure 6).18 Yields for some major crops grew about 2% annually from the 1950s through the 1980s, but that growth has moderated since 1990 (Table 2).

Advances in the basic and applied agricultural sciences—such as disease-resistant crop varieties, efficient irrigation practices, and improved marketing systems—are considered fundamental to achievements in agricultural yields, increases in farm sector profitability, higher competitiveness in international agricultural trade, and improvements in nutrition and human health.

Some want more public spending on agricultural research to maintain U.S. competitiveness and increase agricultural productivity in the face of world population growth and food demand.19 But agricultural research competes for federal funding in relation to other federal agricultural programs, such as conservation, farm income and risk management programs, food safety inspection, rural development, and domestic and foreign food aid programs.20

|

|

|

|

Corn |

Wheat |

Rice |

Soybeans |

|

|

1950-1989 |

2.85 |

1.75 |

2.27 |

1.02 |

|

Post-1990 |

1.5 |

0.15 |

1.37 |

1.16 |

Source: J. M. Alston, J. M. Beddow, and P. G. Pardey, "Agricultural Research, Productivity, and Food Commodity Prices," University of California, 2009, http://giannini.ucop.edu/media/are-update/files/articles/v12n2_5.pdf.

The 2008 farm bill required the REEO to develop and implement a USDA Roadmap for Agricultural Research, Education, and Extension to plan and coordinate across the entire department both capacity and competitive programs, as well as USDA-administered intramural and extramural programs.21 The objective was to identify current trends, constraints, gaps, and major opportunities that no single entity within the USDA would be able to address individually. The research provisions, including changes to the management and structure of REE in the 2008 farm bill, drew heavily on proposals and recommendations put forth by key stakeholder groups, including the USDA Task Force on Research, Education, and Extension and the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities (APLU).22 USDA subsequently published an "Action Plan" that builds upon the Roadmap.23

Some argue that the stagnant growth in inflation-adjusted USDA funding for agricultural research, education, and extension over the past few decades has hurthindered the ability of the U.S. agricultural sector to

stay productive and competitive.24 It is widely acknowledged that new51

New innovations and technologies related to production, processing, marketing, and natural resource management are widely acknowledged as essential for continued productivity gains and economic growth of the sector.

Some of these same criticsSome argue that USDA has not been successful at elevating agricultural research toagriculture has not achieved the same priority level with policymakers as other sectors, such as health, and that U.S. agriculture will wil suffer over

the long term because of a lack of new innovations. These critics argue that the lack of public investment in new agricultural innovations will wil have dire consequences in the future, especially especial y given new and varied challengeschal enges, such as rising production costs, especially for fuel and inputs; new pest and disease outbreaks; increasing frequency of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods; and climate change.

On the other hand, some argue that the federal government should have a limited role in funding agricultural research and that taxpayer dollars should not be used to support what should be a private sector endeavor. In addition, due to a severely constrained federal budget in recent years, limited resources are available to support the agricultural sector. Historically, Congress has not prioritized increasing funding for agricultural research, education, and extension activities, and instead has tended to fund programs designed to provide more immediate benefits to farmers, such as income support and crop insurance. Others believe that the states and the private sector should fill the research funding gap left by the federal government.

At the same time, while private sector funding has increased over time to fill some of the gap in public spending, there is growing concern that private sector funding focuses primarily on taking

47 Sun Ling Wang et al., Agricultural Productivity Growth in the United States: Measurement, Trends, and Drivers, ERS, Economic Research Report (ERR) 189, July 2015 , at https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/45387/53417_err189.pdf. 48 Sun Ling Wang et al., ERR-189, 2015. 49 See CRS Report R46437, Agriculture and Related Agencies: FY2021 Appropriations. 50 For example, see Charles Valentine Riley Memorial Foundation and Iowa State University, A Unifying Message: Pulling Together: Increasing Support for Food, Agricultural and Natural Resources Research, 2018, at https://rileymemorial.org/files/files/RMF A Unifying Message Pulling T ogether June 2018.pdf; Supporters of Agricultural Research Foundation, “Why Support Ag Research,” at https://supportagresearch.org/about/why-support-ag-research; and ERS, Public Agriculture Research Spending and Future U.S. Agricultural Productivity Growth: Scenarios for 2010-2050, EB-17, 2011, at http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/118663/eb17.pdf.

51 See footnote 50.

Congressional Research Service

20

Agricultural Research: Background and Issues

In a step toward increasing innovation for agricultural research, the 2018 farm bil authorized a new Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority (AGARDA) pilot program (P.L. 115-334, §7132) at USDA to carry out innovative research and to develop and deploy advanced solutions to agricultural threats.52 As of September 2020, this pilot program has not received

appropriations.

In contrast to those cal ing for increased funding, some stakeholders argue that the federal government should have a limited role in funding agricultural research and that taxpayer dollars should not be used to support what they believe should be a private sector endeavor. Others

believe that the states and the private sector should fil the research funding gap left by the federal

government.

At the same time, while private sector funding has increased over time, some have expressed

concerns that private sector funding focuses primarily on bringing existing technologies to market (i.e., more applied research) and does not focus on basic problems and/or longer-term challengesresearch to address chal enges that the agricultural sector may face in the future, such as environmental sustainability or adaptation to climate variability.

Some

climate change.

Final y, some advocates have argued that some of USDA's agricultural ’s research portfolio duplicates private sector activities on major crops, including corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton.2553 They argue that funding should be reallocatedreal ocated to basic, noncommercial research to benefit the public good that is not addressed through private efforts. Others point out that thesethe major crops are economically economical y

important to the food, feed, and energy sectors and should continue to receive significant amounts of public funding, especiallyespecial y for emerging threats, such as new pests and pathogens, limited water

availability, and impacts of agriculture on human and environmental health.

Author Information

Genevieve K. Croft

Analyst in Agricultural Policy

52 See CRS In Focus IF11319, 2018 Farm Bill Primer: Agricultural Research and Extension. 53 PCAST , Report to the President on Agricultural Preparedness and the Agriculture Research Enterprise , December 2012, at https://obamawhitehouse.archivesand impacts of agriculture on human and environmental health.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this report were written by Dennis Shields and Melissa Ho.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Economists use the term spillover to capture the idea that some of the economic benefits of research and development activities affect agents, locales, or activities beyond the original research purpose or location. |

| 2. |

The Cooperative Extension system is a nationwide, non-credit educational network where each U.S. state and territory has a state office at its land-grant university and a network of local or regional offices. The purpose of Extension is to gather knowledge gained through research and education and deliver it for practical use directly to farmers and other residents (rural and urban). |

| 3. |

For current appropriations issues and coverage, see CRS Report R44588, Agriculture and Related Agencies: FY2017 Appropriations. |

| 4. |

CRS Report R42484, Budget Issues That Shaped the 2014 Farm Bill. |

| 5. |

Additional details are available in the USDA Budget Summary and Explanatory Notes for NIFA, available at http://www.obpa.usda.gov. |

| 6. |

An exception exists in statute for states that cannot meet the matching requirement. The lack of matching funding for some institutions, however, reduces the resources available to often minority-serving institutions (see Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, Land-Grant But Unequal: State One-to-One Match Funding for 1890 Land-Grant Universities, September 2013, at http://www.aplu.org/library/land-grant-but-unequal-state-one-to-one-match-funding-for-1890-land-grant-universities/file. |

| 7. |

National Academy of Sciences (NAS), Report of the Committee on Research Advisory to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1972. |

| 8. |

Rockefeller Foundation, Science for Agriculture, The Rockefeller Foundation, New York, NY, 1982. |

| 9. |

National Academy of Sciences, National Research Initiative: A Vital Competitive Grants Program in Food, Fiber, and Natural-Resources Research, Washington, DC, 2000, http://www.nap.edu/catalog/9844.html. |

| 10. |

USDA, Research, Education, and Economics Task Force, National Institute for Food and Agriculture: A Proposal, July 2004, http://www.ars.usda.gov/sp2userfiles/place/00000000/national.doc. |

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

Kelly Day Rubenstein et al., "Competitive Grants and the Funding of Agricultural Research in the United States," Review of Agricultural Economics, vol. 25, no. 2 (September 24, 2003), pp. 352-368. |

| 13. |

Wallace E. Huffman and Robert E. Evenson, "Do Formula or Competitive Grant Funds Have Greater Impact on State Agricultural Productivity," American Journal of Economics, vol. 88, no. 4 (November 2006), pp. 783-798. |

| 14. |

Critics have been concerned about the effect on research programs. For example, universities reported widespread delays and reductions in research activities as a result of sequestration (Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, Survey on Sequestration Effects—Selected Results from Private and Public Research Universities, Washington, DC, November 11, 2013, http://www.aau.edu/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=14798). |

| 15. |

This accounting is for the research function only and excludes funding for the Cooperative Extension system. |

| 16. |

|

| 17. |

J. M. Alston, C. Chan-Kang, and M. C. Marra et al., A Meta-Analysis of Rates of Return to Agricultural R&D, International Food Policy Research Institute, 2000, http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/rr113.pdf. |

| 18. |

Philip Pardey, "Putting U.S. Agricultural R&D and Productivity Developments in Perspective," Farm Foundation Conference, 2009, http://www.farmfoundation.org/news/articlefiles/1705-Pardey%20.pdf. |

| 19. |

|

| 20. |

CRS Report R43938, FY2016 Agriculture and Related Agencies Appropriations: In Brief. |

| 21. |

USDA-REE, A Roadmap for USDA Science, 2010, at http://www.ree.usda.gov/ree/news/REE_Roadmap9_final.pdf. |

| 22. |

Create Research, Extension, and Teaching Excellence for the 21st Century (CREATE-21). APLU was previously known as National Association of State Universities and Land Grant Colleges (NASULGC); NASULGC changed its name to APLU in March 2009. |

| 23. |

|

| 24. |

See footnote 19. |

| 25. |

President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report to the President on Agricultural Preparedness and the Agriculture Research Enterprise, Washington, DC, December 2012, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/pcast_agriculture_20121207.pdf. |