Visa Waiver Program

Changes from August 1, 2016 to June 29, 2020

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Recent Developments

- Introduction

- Current Policy

- VWP Qualifying Criteria

- Nonimmigrant Refusal Rate Waiver

- Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA)

- Arrival and Departure Inspections

- Trends in Use of the VWP

- Policy Issues

- Security

- Administration Initiated VWP Security Enhancements

- Debate over Biometric Exit Capacity

- Information Sharing

- Foreign Fighters, Syrian Refugees, and the VWP

- Adding Countries to the VWP

- EU and Reciprocity

- Overstays

- Legislation in the 114th Congress

- Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act (H.R. 158/Miller and S. 2362/Johnson) and Defend America Act (S. 2435/Kirk)

- U.S. Citizens with Dual Citizenship and P.L. 114-113

- Equal Protection in Travel Act (H.R. 4380/Amash and S. 2449/Flake)

- S. 2458/Cardin

- Visa Waiver Program Security Enhancement Act (S. 2337/Feinstein and S. 2377/Reid)

- H.R. 4122/Sinema

- H.R. 4173/Boyle

- Strong Visa Integrity Secures America Act (H.R. 5253/Hurd)

- Jobs Originated through Launching Travel (JOLT) Act (H.R. 1401/Heck, S. 2091/Schumer) and the Visa Wavier Enhanced Security and Reform Act (H.R. 2686/Quigley, S. 1507/Mikulski)

- The Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2016 (S. 1619/Hoeven)

- Virgin Islands Visa Waiver Program (H.R. 2116/Plaskett)

Summary

The terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015 and in Belgium in March 2016, which were perpetrated mainly by French and Belgian citizens, have increased focus on the potential security risks posed by the visa waiver program (VWP). The VWP allows nationals from certainVisa Waiver Program

June 29, 2020

The Visa Waiver Program (VWP), originally established in 1986 as a trial program and made permanent in 2000 (P.L. 106-396), allows nationals from 39 countries, many of which are in

Abigail F. Kolker

countries, many of which are in Europe, to enter the United States as temporary visitors (nonimmigrants) for business or pleasure without first obtaining a visa from a U.S. consulate abroad. Temporary

Analyst in Immigration

without first obtaining a visa. Generally, temporary visitors for business or pleasure from non-

Policy

VWP countries must obtain a visa from Department of State (DOS) officers at a consular post consula r post

abroad before comingtraveling to the United States.

Some observers argue to the United States.

Concerns have been raised about the ability of terrorists to enter the United States under the VWP, because those entering under the VWP undergo a biographic rather than a biometric (i.e., fingerprint) security screening, and do not need to interview with a U.S. government official before embarking to the United States. Nonetheless, it can be argued that the VWP strengthens national security because it sets standards for travel documents, requires information sharing between the member countries and the United States on criminalcrimina l and security concerns, and mandates reporting of lost and stolen travel documents. In addition, VWP travelers have to present e -passports (i.e., passports with a data chip containing biometric information), which tend to be more difficult to alter than other types of passports. Nevertheless, some observers of the program have raised concerns about the possibility that terrorists will enter the United States under the VWP because those entering under the VWP undergo a biographic , rather than a biometric (i.e., fingerprint and digital photograph), security screening and do not need to interview in person with a U.S. consular official before embarking for the United States.

There is also interest in the VWP as a mechanism to promote tourism and commerce. In FY2018, there were more than 22.8 million admissions to the United States under this program, constituting nearly a third of all visitor admissions. The inclusion of countries in the VWP indicates a shared approach to national security and eases consular workloads abroad.

To qualify for the VWP, a country must offer reciprocal travel privileges to U.S. citizens; have had a nonimmigrant visa passports.

Furthermore, there is interest in the VWP as a mechanism to promote tourism and commerce. The inclusion of countries in the VWP may help foster positive relations between the United States and those countries, and ease consular office workloads abroad. As of July 2016, there were 38 countries participating in the VWP.

In FY2014, more than 21 million visitors entered the United States under this program, constituting 31% of all overseas visitors. To qualify for the VWP, statute specifies that a country must offer reciprocal privileges to U.S. citizens; have had a nonimmigrant refusal rate of less than 3% for the previous year; issue their nationals machine-readable passports that incorporate biometric identifiers; identifiers; certify that it is developing a program to issue tamper-resistant, machine-readable visa documents that incorporate biometric identifiers which are verifiable at the country'’s port of entry; report the loss and theft of passports; share specified information regarding nationals of the country who represent a threat to U.S. security; and not compromise the law enforcement or security interests of the United States by its inclusion in the program. Countries can be terminated from the VWP if an emergency occurs that threatens they fail to meet any of these conditions or otherwise threaten the United States'’ security or immigration interests.

All aliens

All foreign nationals (i.e., aliens) entering under the VWP must present passports that contain electronic data chips (e-passports). Under DHSDepartment of Homeland Security (DHS) regulations, travelers who seek to enter the United States through the VWP are subject to the biometric requirements of the United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) program. In addition, aliens enteringseeking to travel to the United States under the VWP must get an approval from the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA), a web-based system that checks the alien'’s information against relevant law enforcement and security databases, before they can board a plane to the United States. ESTA became operational for all VWP countries on January 12, 2009.

Under statute, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) States.

Under statute, the Secretary of Homeland Security has the authority to waive the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate requirement, provided certain conditions are met. The waiver became available in October 2008. In 2008, eight countries were added to the VWP who needed the nonimmigrant refusal rate waiver to be part of the program. However, the waiver authority was suspended on July 1, 2009, because DHS had not fully implemented an air-exit system that incorporates biometric identifiers. The waiver will not be available until such a system is implemented, and it is unknown when and if a biometric exit system will be fully implemented.

Activity in the 116th Congress related to the VWP seeks to expand the number of countries by changing the criteria or by designating specific countries. Other bills would rename the VWP to “Secure Travel Partnership” to reflect one of the program’s main goals of securing travel to the United States. Legislation in the 116th Congress would also address the ESTA fee paid by VWP applicants. In December 2019, Congress authorized the continued use of the ESTA fee to partially fund Brand USA, a national tourism promotion program, through September 30, 2027. Congress also raised the ESTA fee from $14 to $21 (Division I, Title 8 of P.L. 116-94). The effective date of the new ESTA fee has not yet been announced.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 8 link to page 10 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 18 link to page 18 link to page 19 link to page 20 link to page 22 link to page 22 link to page 23 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 25 link to page 33 Visa Waiver Program

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Current Policy ................................................................................................................ 1

VWP Qualifying Criteria ............................................................................................ 5 Nonimmigrant Visa Refusal Rate Waiver....................................................................... 7 Electronic System for Travel Authorization ................................................................... 8 Arrival and Departure Inspections .............................................................................. 10 Trends in Use of the VWP ........................................................................................ 12

Policy Issues ................................................................................................................ 13

Security ................................................................................................................. 13

Debate over Biometric Exit Capacity..................................................................... 15

Information Sharing............................................................................................ 15 Terrorism, Foreign Fighters, and the VWP ............................................................. 16

Adding Countries to the VWP ................................................................................... 17

EU and Reciprocity ............................................................................................ 19

Overstays ............................................................................................................... 19

Legislation in the 116th Congress ..................................................................................... 20

Figures Figure 1. Number of Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Admissions, FY2009-FY2018, and

Percentage of Visitor Admissions That Were VWP .......................................................... 12

Appendixes Appendix. Legislative History and Selected Administrative Action ....................................... 22

Contacts Author Information ....................................................................................................... 30

Congressional Research Service

Visa Waiver Program

Introduction The Visa Waiver Program (VWP) al ows nationals from certain countriesimplemented. There are countries (e.g., Israel, Poland, Romania) that have expressed interest in being a part of the VWP who would need a waiver of the nonimmigrant refusal rate.

On December 8, 2015, the House passed H.R. 158, the Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act. The bill was enacted as part of the FY2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-113), which was signed into law on December 18, 2015. The act makes numerous changes to the VWP, including, with some exceptions, prohibiting those who have traveled to Syria, Iraq, and certain other countries since March 2011 from entering the United States under the VWP. In addition, under the act, dual nationals of VWP countries and Syria, Iraq, and certain other countries, with possible exceptions, are also prohibited from traveling to the United States under the VWP. Moreover, P.L. 114-113 changes the information-sharing requirements for countries to participate in the VWP program. Some of the changes to the VWP made by P.L. 114-113 have raised concerns about discrimination based on national origin or family heritage. Two bills introduced after the passage of P.L. 114-113, H.R. 4380 and S. 2449, would remove the new prohibitions on certain dual nationals traveling under the VWP.

Other legislation has been introduced in the 114th Congress that would reinstate the nonimmigrant refusal rate waiver authority and make other changes to the VWP, such as allowing DHS to use overstay rates to determine program eligibility (H.R. 1401/H.R. 2686/S. 1507/S. 2091). There are also introduced bills that would change some of the program requirements to augment the security features of the program (e.g., H.R. 4122 and S. 2337). Another proposal (H.R. 2116) would create a new visa waiver program for the U.S. Virgin Islands, and allow Poland to be added to the VWP without meeting the program's requirements.

Recent Developments

On December 8, 2015, the House passed H.R. 158, the Visa Waiver Program Improvement Act of 2015, by a vote of 407 to 19. H.R. 158, as passed by the House, was included in the FY2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-113), which was signed into law on December 18, 2015. Among other things, the act changed who can travel under the VWP. The VWP provisions of the act are discussed in detail in "Legislation in the 114th Congress."

Previously, on November 30, 2015, the Obama Administration announced several new enhancements to the VWP meant to increase the security of the program. The changes included modifying the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) to capture information regarding past travel to countries "constituting a terrorist safe haven," as well as requiring reports from the Departments of Homeland Security and Justice to the President on topics ranging from information sharing with VWP countries, to identification of VWP countries who are "deficient in key areas of cooperation," to the delineation of possible pilot programs to collect and use biometric data on VWP travelers. In addition, the Administration will offer assistance to countries to facilitate information sharing and countering terrorist travel. (For a full discussion of the November 30 press release, see "Administration Initiated VWP Security Enhancements.")

Introduction

The Visa Waiver Program allows nationals from certain countries, many of which are in Europe, to enter the United States as temporary visitors for business or pleasure without first obtaining a visa from a U.S.

consulate abroad. Temporary visitors for business or pleasure from non-VWP countriescountries1 must obtain a visa from Department of State (DOS) officers at a consular post abroad before coming to

the United States.

Two main goals of the VWP are increasing tourism and strengthening national security.the United States.

The terrorist attacks in France and Belgium, and the possible threats posed by VWP-country citizens who have radicalized,1 have increased congressional focus on the program.2 While there tends to be agreement that the VWP benefits the U.S. economy by facilitating legitimate travel, there is disagreement on the VWP'’s impact on national security.32 Proponents of the program say the VWP strengthens U.S. national security because it sets standards for travel documents, requires information sharing between the member countries and the United States on

criminal and security concerns, and mandates reporting of lost and stolen travel documents.4 3 Critics of the program argue the VWP could createcreates a security loophole because VWP travelers do not

undergo the screening traditionallyin-person screening general y required to receive a visa.5

4 Current Policy

In general, temporary foreign visitors for business or pleasure from most countries must obtain a "B" nonimmigrant visa6B nonimmigrant visa5 from DOS officers at a consular post abroad before coming to the United States.7

States.6 Personal interviews are generallygeneral y required, and consular officers use the Consular Consolidated Database (CCD) to screen visa applicants. In addition to indicatingThe CCD indicates the outcome of any prior visa application of the alien in the CCD, the system links with other databases to flag problems and facilitates the flagging of issues that may make the alien ineligible ineligible for a visa under the "grounds forof inadmissibility" of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), which include criminal, terrorist, and public health grounds for exclusion. Consular officers are required

to check the background of all al aliens in the "lookout"“lookout” databases, including the Consular Lookout

and Support System (CLASS) and TIPOFF databases.8

Under the VWP, the Secretary of Homeland Security,9 in consultation with the Secretary of State, may waive the "B" nonimmigrant visa requirement for most aliens traveling from certain countries as temporary visitors for business or pleasure (tourists). Eligible nationals from participating

1 T he two exceptions are Canada and Bermuda; they do not participate in the VWP, but their citizens do not need to obtain a nonimmigrant visa except in specified circumstances. For more information, see U.S. State Department, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Citizens of Canada and Berm uda, at https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/tourism-visit/citizens-of-canada-and-bermuda.html.

2 See CRS Report R46300, Adding Countries to the Visa Waiver Program: Effects on National Security and Tourism . 3 For an example of this argument, see Riley Walter, The Visa Waiver Program Is Still Great For America, T he Heritage Foundation, Issue Brief #4273, March 14, 2017, at https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-03/IB4664.pdf.

4 For an example of this argument, see Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), The Visa Waiver Program : Suspend It or Elim inate It, December 2015, at https://www.fairus.org/issue/legal-immigration/visa-waiver-program-suspend-it-or-eliminate-it. 5 Nonimmigrants are foreign nationals lawfully admitted to the United States for a specific purpose and limited period of time. Nonimmigrants are often referred to by the letter that denotes their subparagraph in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA §101(a)(15)), such as H-2A agricultural workers, F-1 foreign students, or J-1 cultural exchange visitors. B nonimmigrant visas are issued to short -term visitors for business or pleasure. For more information, see CRS Report R45040, Im m igration: Nonimm igrant (Tem porary) Adm issions to the United States.

6 T o obtain a nonimmigrant visa, a foreign national must submit an application and undergo a background check and usually an interview. For more information on temporary admissions, see CRS Report R45040, Im m igration: Nonim m igrant (Tem porary) Admissions to the United States.

Congressional Research Service

1

link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 25 Visa Waiver Program

Eligible nationals from participating VWP countries must use the web-based Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA)107 to get an approved electronic travel authorization before embarking to the United States, and. ESTA authorization is general y valid for two years. VWP travelers are admitted into the United States for stays up to 90 days. The VWP constitutes one of a few exceptions under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) in which foreign nationals are admitted into the United States without a valid visa. As of May 2016June 2020, there were 3839 countries

participating in the VWP.11

Prior to enactment in December 2015 8

The large-scale terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015 and in Belgium in March 2016, which

were perpetrated mainly by French and Belgian citizens, increased the focus on potential security risks posed by the VWP. Prior to the December 2015 enactment of the Visa Waiver Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act (P.L. 114-113),12 all ), al nationals from a VWP country were eligible eligible to travel under the program—provided they received an ESTA approval. P.L. 114-113 1139 changed eligibility for the VWP by prohibiting people who were present in certain countries since March 1, 2011, with limited exceptions, from traveling under the VWP. The specified countries include

- include Iraq and Syria,

- any country designated by the Secretary of State as having repeatedly provided

support for acts of international terrorism under any provision of law,

13 or - 10 or

any other country or area of

concernconcern11 deemed appropriate by the Secretary ofDHS.14

Homeland Security.12

Currently, the prohibition affects those who were present in any of the following countries:

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. The statutory exceptions from this restriction apply to foreign nationals who were in one of the specified countries in order to perform military service in the armed forces of a VWP country, or to perform official duties as an employee of the VWP country. In addition, the Administration has stated that waivers are to be grantedDHS can grant waivers on a case-by-case basis, but that the.13 The following are general categories of travelers to these countries who may be eligible for a waiver: (1) individuals who traveled on behalf of 7 EST A became operational for all VWP countries on January 12, 2009; for more information, see “ Electronic System for T ravel Authorization,” below. 8 Poland was designated a VWP country on November 8, 2019. See Department of Homeland Security, “Designation of Poland for the Visa Waiver Program,” 84 Federal Register 60316, November 8, 2019. 9 For more details about P.L. 114-113, see Appendix. 10 Examples of acts that use the term “ repeatedly provided support for acts of international terrorism,” include §6(j) of the Export Administration Act of 1979 (50 U.S.C. 2405), §40 of the Arms Export Control Act (22 U.S.C. 2780), and §620A of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2371). Currently, these countries are Iran, Sudan, and Syria.

11 T he criteria to make the determination would include whether the presence of a foreign national in that area or country increases the likelihood that the foreign national is a credible threat to U.S. national security, whether a foreign terrorist organization has a significant presence in the area or country, and whether the country or area is a safe haven for terrorists. DHS has designated the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen as “countries or areas of concern.” 12 T he Secretary of Homeland Security administers the VWP program. Section 402 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (HSA; P.L. 107-296), signed into law on November 25, 2002, states:

T he Secretary [of Homeland Security], acting through the Under Secretary for Border and T ransportation Security, shall be responsible for the following: ... (4) Establishing and administering rules, ... governing the granting of visas or other forms of per mission, including parole, to enter the United States to individuals who are not a citizen or an alien [sic] lawfully admitted for permanent residence in the United States.

13 8 U.S.C. §1187(a)(12)(C).

Congressional Research Service

2

Visa Waiver Program

countries who may be eligible for a waiver: (1) individuals who traveled on behalf of international organizations, regional organizations, and sub-national governments on official duty; (2) individuals who traveled on behalf of a humanitarian non-governmental organization (NGO) on official duty; (3) individuals who traveled as journalists for reporting purposes; (4) individuals individuals who traveled to Iran for legitimate business-related purposes following the conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (July 14, 2015);1514 and (5) individuals who have travel

to Iraq for legitimate business-related purposes.16

15

In addition, anyone who is a dual national of a VWP country and one of these specified countries is ineligible the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, or Syria is ineligible to travel under the VWP. As with the

prohibition against using the VWP for those who were present in certain countries, the Secretary of DHSHomeland Security has the authority to waive the prohibition on travel under the VWP by certain dual nationals if the Secretary of DHS determines that the waiver would be in the law enforcement or national security interests of the United States. As of the date of this report, DHS has not released any guidance on waivers for dual nationals.16 DHS reports on these waivers to Congress annual y, but these reports are not

available to the public.

14 On July 14, 2015, Iran and the six powers that have negotiated with Iran about its nuclear program since 2006 (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and Germany) finalized a Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). T he JCPOA is intended to ensure that Iran ’s nuclear program can be used for purely peaceful purposes, in exchange for a broad lifting of U.S., European Union (EU), and United Nations (U.N.) sanctions on Iran. On May 8, 2018, President T rump announced that the United States would no longer participate in the JCPOA . On January 5, 2020, Iran declared it would no longer abide by the limitations of the deal. For more on the JCPOA, see CRS Report R43333, Iran Nuclear Agreem ent and U.S. Exit. 15 T here is no separate application for a waiver. A foreign national’s eligibility for a waiver is determined during the EST A application process. U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Visa Waiver Program Im provem ent and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act Frequently Asked Questions, at https://www.cbp.gov/travel/international-visitors/visa-waiver-program/visa-waiver-program-improvement-and-terrorist -travel-prevention-act-faq, accessed November 13, 2019.

16 For a discussion of some of the issues surrounding implementing the dual national provision, see Nahal T oosi, “Obama Aides Vexed by Visa Crackdown,” Politico, April 12, 2016, Europe Edition, athttp://www.politico.eu/article/obama-aides-vexed-by-visa-crackdown/http://www.politico.eu/article/obama-aides-vexed-by-visa-crackdown/.

Congressional Research Service

3

Visa Waiver Program

dual nationals.17

Visa Waiver Program Countries Andorra, Australia, |

Although the VWP eases the documentary requirements for certain nationals from participating countries

Although the VWP al ows certain nationals from participating countries to enter the United States without a visa, it has important restrictions. Aliens entering with a B visa may petition to extend their length of stay in the United States or may petition to change to another nonimmigrant or immigrant status.1817 Aliens entering through the VWP are not permitted to extend their stays except for emergency reasons and then for only 30 days.19 Additionally18 Additional y, with some limited exceptions, aliens entering through the VWP are not permitted to adjust their immigration status.

An alien entering through the VWP who violates the terms of admission becomes deportable

without any judicial recourse or review (except in asylum cases).19

17 Noncitizens entering on B visas may be admitted for six months, and may apply to extend their stay for another six months. 18 T his provision was amended by P.L. 106-406 to provide exceptions for nonimmigrants who enter under the VWP and require medical treatment.

19 T o receive asylum, a foreign national must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution in his or her home country based on one of five grounds—race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion—and meet other requirements. For more on asylum, see CRS Report R45539, Im m igration: U.S. Asylum Policy.

Congressional Research Service

4

Visa Waiver Program

VWP Qualifying Criteria To qualify for the VWP, a country must

offer reciprocal privileges to United States citizens; have had a nonimmigrant visa refusal rate20 of less than 3% for the previous year

or a lower average percentage over the previous two fiscal years;

issue electronic, machine-readable passports that contain a biometric identifier

(i.e., e-passports);21

without any judicial recourse or review (except in asylum cases).20

VWP Qualifying Criteria

Currently, to qualify for the VWP a country must

- offer reciprocal privileges to United States citizens;

- have had a nonimmigrant refusal rate of less than 3% for the previous year or an average of no more than 2% over the past two fiscal years with neither year going above 2.5%;

- certify that it has established a program to issue to its nationals machine-readable passports that are tamper-resistant and incorporate a biometric identifier (on April 1, 2016, all passports presented by aliens entering under the VWP were required to be machine-readable and contain a biometric identifier [i.e., e-passports]);21

certify that it is developing a program to issue tamper-resistant, machine-readable visa documents that incorporateissue tamper-resistant, machine-readable visa documents that incorporate biometric identifiers, which are verifiable at the country'’s port of entry;no later than October 1, 2016, certify that it has in place mechanisms to validate machine-readable passports and e-passports at each port of entry;22- 22

enter into an agreement with the United States to report or make available

through the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL)

2324 - 24

certify, to the maximum extent

allowedal owed under the laws of the country, that it is screening each foreign national who is admitted to or departs from that country, using relevant INTERPOL databases and notices, or other means designated by the Secretary ofDHSHomeland Security (this requirementgoes into effect 270 days after December 18, 2015, and only appliesapplies only to countries that have an international airport);25 - 25

accept the repatriation of any citizen, former citizen, or national against whom a

final order of removal from the United States is issued no later than three weeks after the order is issued;

enter into and fully implement2620 T his rate represents the proportion of individuals whose applications for tourist or business visas have been rejected by U.S. consular officials in their home countries. 21 Prior to the enactment of P.L. 114-113 only passports issued after October 26, 2006, had to be machine-readable and contain a biometric identifier. In August 2015, the Secretary of Homeland Security announced that to increase security of the VWP all travelers under the program would have to use an e-passport, but the requirement had not been put into effect before the enactment of P.L. 114-113. Department of Homeland Security, “ Statement by Secretary Jeh C. Johnson on Intention to Implement Security Enhancements to the Visa Waiver Program,” press release, August 6, 2015, at https://www.dhs.gov/news/2015/08/06/statement -secretary-jeh-c-johnson-intention-implement-security-enhancements-visa; and telephone conversation with DHS Office of Legislative Affairs, Nove mber 3, 2015. 22 T his requirement was added by P.L. 114-113, and does not apply to travel between countries within the Schengen Area, which comprises 22 European Union (EU) member states, plus 4 non-EU countries. Within the Schengen Area, internal border controls have been largely eliminated, and individuals may travel without passport checks among participating countries. See European Commission, Migration and Hom e Affairs: Schengen Area, at http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what -we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen/index_en.htm. 23 Although statute discusses sharing information on lost and stolen passports, the INT ERPOL database includes other types of travel documents such as identity documents and visas. INT ERPOL is the world’s largest international police organization, with 194 member countries. For more information on INT ERPOL see, https://www.interpol.int/Who-we-are/What -is-INT ERPOL. 24 P.L. 114-113 added the requirement that the reporting occur within 24 hours of the country being notified about the lost/stolen passport . 25 T his screening requirement was added by P.L. 114-113, and does not apply to those traveling between countries within the Schengen Area. Congressional Research Service 5 Visa Waiver Program enter into and fully implement26 an agreement with the United States to sharean agreement with the United States to shareinformation regarding whether a national of that country traveling to the United States represents a threat to U.S. security or welfare; and- be determined, by the Secretary of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State, not to compromise the law enforcement or security interests of the United States by its inclusion in the program.

The Secretary of DHSHomeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State, can suspend a program country

country’s participation in the program based on a determination that the country presents a "high risk" to U.S. national security.2727 In addition, countries can be immediately terminated from the VWP if an emergency occurs in the country that the Secretary of Homeland Security in consultation with the Secretary of State determines threatens the law enforcement or security interest of the United States.2828 For example, because of Argentina'’s economic collapse in

December 2001,2929 and the increase in the number of Argentine nationals attempting to use the VWP to enter the United States and remain illegally il egal y past the 90-day period of admission,30 that country30 Argentina was removed from the VWP in February 2002.31 Similarly, on April 15, 2003, Uruguay was terminated from the VWP because Uruguay's participation in the VWP was determined to be inconsistent with the U.S. interest in enforcing immigration laws.32 31 Likewise, Uruguay joined in 1999, but it was removed from the program in April 2003 because a recession led to an increasing number of Uruguayan citizens entering the United States under the VWP to live and work

il egal y.32 No country has been removed from the VWP since 2003.

Additionally,

Additional y, there is a probationary status for VWP countries that do not maintain a low disqualification rate. Countries on probation are determined by a formula based on a disqualification 33 VWP countries are placed on probation when they have a disqualification 26 T he requirement to implement the agreement was added by the Visa Waiver Improvement and T errorist Travel Prevention Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-113), enacted on December 18, 2015.

27 T he criteria to determine whether a country poses a “high risk” to national security include the number of nationals determined to be ineligible to t ravel to the United States under the VWP during the previous year; the number of nationals who were identified in U.S. government terrorism databases during the previous year, the estimated number of nationals who traveled to Iraq or Syria since March 1, 2 011, to engage in terrorism; the country’s capacity to combat passport fraud; the level of cooperation with U.S. counter -terrorism efforts; the adequacy of the country’s border and immigration controls; and any other criteria determined by the Secretary of Homeland Security.

28 An emergency is defined as (1) the overthrow of a democratically elected government; (2) war; (3) a severe breakdown in law and order in the country; (4) a severe economic collapse; and (5) any other extraordinary event in the program country where that country’s participation could threaten the law enforcement or security intere sts of the United States. INA §217(c)(5)(B). 29 Beginning in December 2001, Argentina experienced a serious economic crisis, including defaulting on loans by foreign creditors, devaluation of its currency, and increased levels of unemployment and poverty.

30 In addition, many Argentine nationals were trying to use the VWP to obtain entry to the United States solely for the purpose of proceeding to the Canadian border and pursuing an asylum claim in Canada. According to Citizenship and Immigration Canada, between 1999 and 2001, more than 2,500 Argentines filed refugee claims in Canada after transiting the United States under the VWP. Federal Register, February 21, 2002, vol. 67, no. 35, p. 7944.

31 While the number of Argentine nonimmigrant travelers to the United States declined between 1998 and 2000, the number of Argentines denied admission at the port of entry and the number of interior apprehensions increased. T h e Department of Justice (DOJ) in consultation with DOS determined that Argentina’s participation in the VWP was inconsistent with the United States’ interest in enforcing its immigration laws. (T he Department of Homeland Security did not exist in February 2002, and authority for the VWP resided with the Attorney General in the DOJ.) Federal Register, February 21, 2002, vol. 67, no. 35, pp. 7943 -7945.

32 Between 2000 and 2003, Uruguay experienced a recession causing its citizens to enter under the VWP to live and work illegally in the United States. In 2002, Uruguayan nationals were two to three times more likely than all nonimmigrants on average to have been denied admission at the port of entry. Uruguayan air arrivals had an apparent overstay rate more than twice the rate of the average apparent overstay rate for all air arrival nonimmigrants. Federal Register, March 7, 2003, vol. 68, no. 45, pp. 10954-10957. 33 Disqualification rate is defined as the percentage of nationals from a country who either violated the terms of the nonimmigrant visa, who were excluded from admission to the United States at a port of entry, or who withdrew their

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 25 Visa Waiver Program

rate of 2% to 3.5%.rate of 2% to 3.5%.33 Probationary countries with a disqualification rate less than 2% over a period not to exceed three yearsprescribed in regulations (but not to exceed three years)34 are removed from probationary status and may remain VWP countries.3435 Countries may also be placed on probation if an issue arises and more time is necessary to determine whether the continued participation of the country in the VWP is in the security interest of the United States. For example, in April 2003, Belgium was placed on provisional status because of concerns about the integrity of non-machine-readable Belgian nonmachine-readable

Belgian passports and the reporting of lost or stolen passports.3536 DHS completed another country review of Belgium in 2005, and removed the country from probationary status. Belgium was the

last country that wasto have been placed on probation.

Nonimmigrant Visa Refusal Rate Waiver

Section 711 of the Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-53)37 al ows110-53)36 allows the Secretary of DHSHomeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of DOS, State, to waive the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate requirement for admission to the VWP after the

Secretary of DHSHomeland Security certifies to Congress that

-

an air exit system is in place that can verify the departure of not less than 97% of

foreign nationals

thatwho exit through U.S. airports,37 and - 38 and

the electronic travel authorization system is operational.39

To participate in the program, a country that receives a visa refusal rate waiver also must

meet al the other requirements of the program; be determined by the Secretary of Homeland Security to have a totality of

security risk mitigation measures that provide assurances that the country’s participation in the program would not compromise U.S. law enforcement and security interests, or the enforcement of U.S. immigration laws;

application for admission at a U.S. port of entry (8 U.S.C. §1187(f)(4)).

34 8 U.S.C. §1187(h)(3)(C). 35 T he Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-208). 36 Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, “Attorney General’s Evaluations of the Designations of Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Uruguay as Participants Under the Visa Waiver Program,” 68 Federal Register, 10954-10957, March 7, 2003, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2003-03-07/pdf/03-5244.pdf.

37 P.L. 110-53 (H.R. 1), signed into law on August 3, 2007. For more details on the changes to the VWP in this act, see Appe ndix, “ Legislative History.”

38 T here was disagreement between some critics and DHS regarding what needed to be verified. Some contended that congressional intent was to have a functional entry -exit system that would be able to match arrival and departure records and know which aliens failed to depart from the United States rather than just matching the entry records with the records of those who were known to have departed from the United States. For example, see S. 203 introduced in the 111th Congress, which attempted to clarify the language in this pro vision. U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Judiciary, Subcommittee on T errorism, T echnology and Homeland Security, The Visa Waiver Program : Mitigating Risks to Ensure Safety to All Am ericans, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., September 24, 2008.

39 DHS determined that the law permitted it to utilize the waiver when EST A was functional but before it was mandatory for all VWP travelers. Critics did not agree with this interpretation and thought that EST A should have been mandatory for all VWP travelers before new countries were designated into the program. When the new countries entered the program, their citizens were required to use EST A before travelling to the United States. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Visa Waiver Program : Actions Are Needed to Im prove Man agem ent of the Expansion Process, and to Assess and Mitigate Program Risks, GAO-08-967, September 2008.

Congressional Research Service

7

link to page 18 Visa Waiver Program

the electronic travel authorization system (ESTA discussed below) is operational.38

The waiver became available in October 2008, and was suspended on July 1, 2009. Under statute, the Secretary of DHS's authority to waive the nonimmigrant refusal rate is suspended until the air exit system is able to match an alien's biometric information with relevant watchlists and manifest information. It is unclear when DHS will implement an exit system with the specified biometric capacity.39

To participate in the program, a country that receives a refusal rate waiver also has to

- meet all the security requirements of the program;

- be determined by the Secretary of DHS to have a totality of security risk mitigation measures that provide assurances that the country's participation in the program would not compromise U.S. law enforcement and security interests, or the enforcement of U.S. immigration laws;

have had a sustained reduction in visa refusal rates, and have existing conditionshave had a sustained reduction in visa refusal rates, and have existing conditions for the rates to continue to decline;- have cooperated with the United States on counterterrorism initiatives and information sharing before the date of its designation, and be expected to continue such cooperation; and

-

have had, during the previous fiscal year, a nonimmigrant

visasvisa refusal rate of less than 10%, or an overstay rate that did not exceed the maximum overstay rate established by the Secretaries of DHS and DOS for countries receiving waivers of the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate to participate in the program.

P.L. 110-53 also specified that in determining whether to waive the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate requirement, the Secretary of DHSHomeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of DOS, State,

may take into consideration other factors affecting U.S. security, such as the country's airport security and passport standards,’s airport

security standards and whether the country has an effective air marshal program, and the estimated overstay rate for nationals from the country.

Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA)

As previously mentioned,.

The nonimmigrant visa refusal rate waiver became available in October 2008 and was suspended

on July 1, 2009. Under P.L. 110-53, the Secretary of Homeland Security’s authority to waive the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate was suspended on July 1, 2009, and is to remain suspended until the air exit system is able to match an alien’s biometric information with relevant watch lists and manifest information.40 U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is implementing biometric air exit systems across the country; their goal is to deploy biometric exit at 20 airports by 2022,

which would capture 97% of al commercial air travelers departing the United States. 41

Electronic System for Travel Authorization P.L. 110-53 mandated that the Secretary of DHSHomeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of Stateof DOS, develop and implement an electronic travel authorization system through which each alien electronical yalien electronically provides, in advance of travel, the biographical information necessary to determine whether the alien is eligible to travel to the United States and enter under the VWP. The system as implemented is known as the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA),

and became fully operational for all al VWP visitors traveling to the United States on January 12,

40 Section 110 IIRIRA, as amended, requires DHS to implement an automatic, biometric entry -exit system that covers all noncitizen travelers into and out of the United States and that identifies visa overstayers. For more information, see “Debate over Biometric Exit Capacity,” below. 41 Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration and U.S. Customs and Border Protection: Deploym ent of Biom etric Technologies, Report to Congress, August 30, 2019, p. 5, at https://www.tsa.gov/sites/default/files/biometricsreport.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

8

Visa Waiver Program

2009.42 There is a $14 fee for travelers who use ESTA.43 In 2019, Congress approved raising the

ESTA fee from $14 to $21, but the effective date of the new fee has not yet been announced.44

ESTA screens applicants’ biographical information against a number of security databases,

including the Terrorist Screening Database, TECS (not an acronym, but a system used by CBP officers to screen arriving travelers to the United States),45 the Automated Targeting System, and INTERPOL’s Lost and Stolen Passport database. ESTA alerts the alien whetherVWP visitors traveling to the United States by airplane or cruise ship on January 12, 2009.40 There is a $14 fee for travelers who use ESTA.41

In advance of departing for the United States by airplane or cruise ship,42 aliens traveling under the VWP are required to use ESTA to electronically provide biographical information to make the eligibility determinations.43 ESTA alerts the alien that he or she has been approved to travel, and; 46 if not approved, the alien may stil travel to the US but must obtain the

relevant visa. the alien needs to obtain a visa prior to coming to the United States.44 The information required by ESTA includes

-

biographical information including name, birth date, country of citizenship,

other citizenships (i.e., dual citizenship), previous citizenships, country of residence, telephone number, other names/aliases, parents

'’ names, national identification number (if applicable), employment information (if applicable), city of birth;45 - 47 passport information including number, issuing country, issuance date, and expiration date; and

-

travel information including departure city, flight number, U.S. contact

information, and address while in the United States.48

Eligibility to travel, which is determined by ESTA, is valid for two years or until the person’s passport expires (whichever comes first)49 and multiple entries. Throughout this period, the ESTA system continual y vets approved individuals’ information against the aforementioned databases.

42 Entrants under the VWP from countries that receive a waiver of the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, and South Korea) had to use t he system starting on the date of their formal admission to the program. For all the countries except Malta, that date was November 17, 2008 . Malta was formally designated into the VWP on December 30, 2008. Department of Homeland Security, “ Electronic System for T ravel Authorization (EST A) Advisory Statement,” November 6, 2008. Department of Homeland Security, “ Electronic System for T ravel Authorization: Mandatory Compliance Required for T ravel Under the Visa Waiver Program,” 73 Federal Register 67354, November 13, 2008. 43 T he fee was instituted on September 8, 2010. T he $14 fee includes $4 to cover the costs of administering EST A and $10 for the travel promotion fee established by Congress in the T ravel Promotion Act of 2009 (§9 of P.L. 111-145) and extended until September 30, 2020, by T itle VI of P.L. 113-235. (Department of Homeland Security, Customs and Border Protection, “DHS, CBP Announce Interim Final Rule For EST A Fee,” press release, August 6, 2010). 44 P.L. 116-94, Division I, T itle VIII reduces the amount available for travel promotion to $7 per traveler. Of the remainder, $4 will continue to go to CBP to cover the costs of administering EST A, and $10 will be directed to the U.S. T reasury for the general fund. T it le VIII of P.L. 116-94 further extended it until September 30, 2027.

45 T ECS, managed by DHS, is an updated version of the T reasury Enforcement Communications System. 46 In most cases, the determination process is almost instantaneous. Under statute, EST A determinations are not reviewable by the courts.

47 In November 2014, DHS added new questions to EST A in response to security concerns. Department of Homeland Security, Customs and Border Protection, ESTA - New questions to the ESTA application, CBP INFO Center, Washington, DC, November 3, 2014, at https://help.cbp.gov/app/answers/detail/a_id/1756/~/esta—new-questions-to-the-esta-application. Although the administration was already asking the questions, P.L. 114-113 statutorily added the requirement that nationals be queried about multiple and previous citizenships. 48 Much of the information is the same that is required on the nonimmigrant visa waiver arrival/departure form (Form I-94W). According to DHS, when developing EST A, the department had to balance the need for biographic information with the requirement that the participating countries did not view applying for an approval under EST A as equivalent to applying for a visa. If countries had interpreted applying for an authorization under EST A as having the same burden as applying for a visa, these countries might have required that U.S. citizens traveling to their countries obtain a visa.

49 Under statute, the maximum period of time is set in regulation by the Secretary of Homeland Security but cannot exceed three years.

Congressional Research Service

9

Visa Waiver Program

The Secretary of Homeland Security has the authority to shorten or revoke the determination of eligibility at any time.50 Notably, a determination under ESTA that an alien is eligible

information, and address while in the United States.46

ESTA also screens applicant responses to the same VWP eligibility questions that were collected on the Form I-94W, which aliens arriving in the United States under the VWP were required to complete to be admitted.47 The I-94W form became automated in 2013 and is no longer used.48

Eligibility to travel, which is determined by ESTA, is valid for two years or until the person's passport expires.49 However, the Secretary of DHS has the authority to shorten the validity period of any ESTA determination, or revoke the determination at any time.50 An ESTA approval is valid for multiple entries, and can be revoked or have the validity period shortened at any time for any reason. Notably, a determination under ESTA that an alien is eligible to travel to the United States does not constitute a determination that the alien is admissible. Admissibility determinations are made by Customs and Border Protection (CBP)CBP inspectors at the ports of entry.

In addition, P.L. 114-113 requires the Secretary of DHS to research developments to incorporate into ESTA technology to detect and prevent fraud or deception.

(the same is true for al visa holders). Arrival and Departure Inspections

Unlike other nonimmigrants, those entering under the VWP do not have to get a visa and thus, have no contact withare

not inspected by U.S. governmental officials until they arrive at a U.S. port of entry and are inspected by CBP officers. Nonetheless, in addition to getting authorization through ESTA, prior to the alien'’s arrival, an electronic passenger manifest is sent from the airline or commercial vessel to CBP officials at the port of entry which, as is done for al airline and commercial vessels departing from a foreign country destined for a U.S. port of

entry. This manifest is checked against security databases.

Since October 1, 2002, passenger arrival and departure information on individuals entering and leaving the United States under the VWP has been electronicallyelectronical y collected from airlines and cruise lines, through CBP'’s Advanced Passenger Information System (APIS) system. If the carrier fails to submit the information, an alien may not enter under the VWP. APIS sends the data to the DHS's Immigration and Customs Enforcement's (ICE's)51 APIS

collects carrier information (e.g., flight number, airport of departure, and other information), as wel as travelers’ personal information, including complete name, date of birth, passport number, country of citizenship, and country of residence.52 APIS sends the data to the DHS’s Arrival and Departure Information System (ADIS) for matching arrivals and departures and reporting

purposes. If the carrier fails to submit the information, an alien may not enter under the VWP.

At U.S.purposes. APIS collects carrier information such as flight number, airport of departure, and other data.

At ports of entry, CBP officers observe and question applicantsforeign nationals, examine passports, and conduct checks against a computerized system to determine whether the applicant is admissible to the United States.51 Primary inspection consists of a brief interview with a CBP

officer, a cursory check of the traveler'’s documents, and a query of the Interagency Border Inspection System (IBIS),5253 and entry of the traveler certain biographic and biometric the information on the travelers into the United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) system. The US-VISIT system uses biographical (e.g., passport information) and biometric identification (finger scans and digital photographs) to check identity.53 Officers at the border collect the 54 Officers at the border collect the

50 T he provision giving the Secretary of Homeland Security the authority to shorten an EST A validity period was enacted as part of P.L. 114-113.

51 APIS is required pre-departure (i.e., before securing the doors) for all air carrier flights to and from the United States. For inbound cruise ships the data must be received 96 hours before arrival at a U.S. port , and for cruise ships leaving the United States, the data must be transmitted 60 minutes before departure. For private aircraft, a passenger and crew manifest listing all persons traveling on the aircraft must be sent electronically using the online eAPIS system at least one hour prior to departure for an inbound or outbound international flight .

52 T he transmission, retention policies, data security, and redress procedures pertaining to APIS data (and other Passenger Name Record data) received by CBP is to comport with the US/EU Passenger Name Record Agreement. For more information, see CRS Report RS22030, U.S.-EU Cooperation Against Terrorism .

53 ADIS feeds information to the Interagency Border Inspection System (IBIS). IBIS is a database of suspect individuals, businesses, vehicles, aircraft, and vessels that is used during inspections at the border. IBIS interfaces with the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC), the T reasury Enforcement and Communications System (T ECS II), National Automated Immigration Lookout System (NAILS), Non -immigrant Information System (NIIS), CLASS and T IPOFF terrorist databases. Because of the numerous systems and databases that interface with IBIS, the system is able to obtain such information as an alien’s criminal history and whether an alien is wanted by law enforcement . Department of Homeland Security, Customs and Border Protection, IBIS- General Inform ation, Washington, DC, July, 31, 2013. 54 For more information on US-VISIT , see CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of

Congressional Research Service

10

Visa Waiver Program

following information on aliens entering under the VWP: name, date of birth, nationality, gender, passport number, country of issuance, a digital photograph, and prints for both index finders. Primary inspections are quick (usually lasting no longer than a minute)typical y quick; however, if the CBP officer is suspicious that the traveler may be inadmissible under the INA or in violation of other U.S. laws, the traveler is referred to a secondary inspection. Those travelers sent to secondary inspections are questioned extensively,

travel documents are further examined, and additional databases are queried.54

Additionally, 55

Additional y, the Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act (P.L. 110-53) ) required that the Secretary of DHSHomeland Security, no later than one year after enactment (i.e., by

August 3, 2008), establish an exit system that records the departure of every alien who entered under the VWP and left the United States by air. The exit system is required to match the alien's ’s biometric information against relevant watch lists and immigration information, and compare such biographical information against manifest information collected by airlines to confirm that

the alien left the United States.

In April 2008, DHS published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register that would have created biometric exit procedures at airports and seaports for international visitors.55 56 DHS was expected to publish the final rule for this system by October 15, 2008.5657 However, in legislation

legislation that became law on September 30, 2008,5758 Congress required DHS to complete and report on at least two pilotsstudies testing biometric exit procedures at airports.58 DHS completed the pilot programs, but according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), "DHS cannot reliably commit to when and how the work will be accomplished to deliver a comprehensive exit solution to its almost 300 ports of entry."59 In what some view as the first step in implementing an exit system, in December 201159 After piloting various biometric programs, CBP, in partnership with the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), is currently deploying the Traveler Verification Service (TVS). TVS is a private-public partnership60 that uses facial recognition technology to verify travelers’ identities. DHS in January 2020 reported TVS capturing roughly 60%61 of in-scope travelers.62 CBP’s goal is to deploy TVS

at 20 airports by 2022, which would capture 97%63 of al commercial air travelers departing the

United States.64

Another step in implementing an exit system occurred in December 2011, when DHS announced an agreement with Canada to share entry records so that an entry into Canada along the land border would be counted as an exit in U.S. records.60

Trends in Use of the VWP

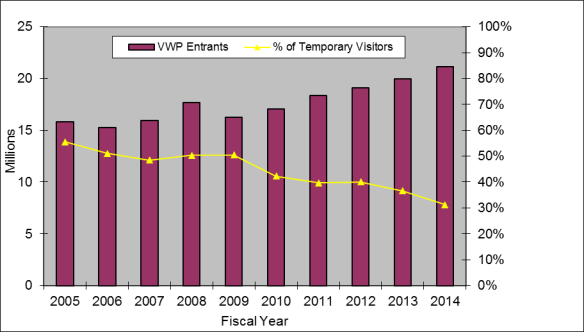

Figure 1 shows the number of entrants under the VWP, and VWP entrants as a percentage of all temporary visitors.61 Since FY2009, the number of entrants under the VWP has steadily increased. In FY2014, over 21 million people entered under the VWP, the largest number of people ever to enter under the program. However, since FY2009, the proportion of total visitors represented by VWP entrants has continuously declined. In FY2014, visitors entering under the VWP constituted 31% of all temporary visitors, the smallest percentage in more than 20 years.62

Policy Issues

The terrorist attacks in Europe in 2015 and 2016, and the possible threats posed by VWP country citizens who have radicalized and may have returned from fighting in the Middle East for terrorist groups such as the Islamic State,63 have increased congressional focus on the benefits of and risks posed by the visa waiver program.64 The VWP is supported by the U.S. travel and tourism industry, the business community, and DOS. The

Entry.

55 For more information on the screening process, see CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry. 56 Department of Homeland Security, “Collection of Alien Biometric Data Upon Exit From the United States at Air and Sea Ports of Departure,” 73 Federal Register 22065, April 24, 2008. 57 CRS analyst conversation with Department of Homeland Security Congressional Affairs, September 22, 2008. 58 P.L. 110-329. 59 One pilot tested DHS’s recommended solution that carriers collect biometrics from passengers; the other pilot tested CBP officers collecting passenger biometrics at the boarding gate.

60 Private partners include airports and airlines. 61 Based on CRS discussion with CBP officials on January 30, 2020. 62 In-scope travelers include non-U.S. citizens aged 14-79. 63 T his would fulfill the final requirement needed to reinstate the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate waiver. 64 Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration and U.S. Customs and Border Protection: Deploym ent of Biom etric Technologies, Report to Congress, August 30, 2019, p. 5, at https://www.tsa.gov/sites/default/files/biometricsreport.pdf.

Congressional Research Service

11

Visa Waiver Program

border would be counted as an exit in U.S. records.65 This is part of the joint Beyond the Border

initiative,66 which is currently in Phase III of implementation.67

Figure 1. Number of Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Admissions, FY2009-FY2018, and

Percentage of Visitor Admissions That Were VWP

Source: CRS analysis of data from Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, multiple years; Table 25. Note: Number of countries participating in the VWP at the end of the fiscal year: FY2009, 35; FY2010-FY2012, 36; FY2013, 37; FY2014-FY2018, 38. Visitor admissions count those who entered with B visas, those who entered under the Guam Visa Waiver Program, and those who entered under the VWP.

Trends in Use of the VWP Arrivals of international visitors to the United States have general y increased in most years over the past decade. International visitors to the United States increased from 32.9 mil ion in 2007 to 73.8 mil ion in 2018.68 The growth during this time has mostly been consistent except for a decrease in 2009 caused by the Great Recession. Visitor admissions wil likely fal sharply in 2020 due to the decline in international travel associated with the Coronavirus Disease 2019

(COVID-19) pandemic.

65 T estimony of David F. Heyman, U.S. Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Immigration Policy and Enforcement, Next Steps for the Visa Waiver Program , 112th Cong., 1st sess., December 7, 2011. For more on this agreement, see CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Im m igration Inspections at Ports of Entry .

66 T he White House, “ Declaration by President Obama and Prime Minister Harper of Canada - Beyond the Border, press release, February 4, 2011, at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/02/04/declaration-president -obama-and-prime-minister-harper-canada-beyond-bord. 67 For more information, see Department of Homeland Security, “ U.S. and Canada Continue Commitment to Securing our Borders, Begin Phase III of the Entry/Exit Project Under the Beyond the Border Initiative ,” press release, July 11, 2019, at https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/07/11/us-and-canada-continue-commitment -securing-our-borders-begin-phase-iii-entryexit .

68 Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, multiple years; T able 25.

Congressional Research Service

12

link to page 15 Visa Waiver Program

Figure 1 shows the number of admissions under the VWP and VWP admissions as a percentage of al temporary visitor admissions.69 Since FY2009, the number of admissions under the VWP has steadily increased. In FY2018, there were 22.8 mil ion admissions under the VWP, the largest number ever under the program. However, from FY2009 to FY2016, the proportion of total visitor admissions represented by VWP admissions declined.70 In FY2018, VWP admissions constituted 31% of al temporary visitor admissions to the United States, the smal est percentage

in more than 20 years.

Policy Issues The VWP is supported by the U.S. travel and tourism industry and the business community. The travel and tourism industry views the VWP as a tool to facilitate and encourage foreign visitors for business and pleasure, which results in increased economic growth generated by foreign

tourism and commerce for the United States.6571

The Department of State also supports the VWP. DOS argues that by waiving the visa requirement for high-volume/low-risk countries, consular workloads are significantly reduced, allowing

al owing for streamlined operations, cost savings, and concentration of resources on greater-risk nations in the visa process.66 Additionally, it is unclear that DOS has the resources to issue B visas to all the visitors from VWP countries.67

72 The travel industry argues that DOS would have to hire many more

consular officers to meet the demand for B visas from VWP countries absent the program.73

While there tends to be agreement that the VWP benefits the U.S. economy by facilitating legitimate travel, there is disagreement on the VWP'’s impact on national security, with some arguing that the VWP presents a significant security risk and others arguing that it enhances

national security.

Security There has been significant debate about whether the VWP increases or decreases national

security. As discussed, travelers under the VWP do not undergo the in-person screening general y required to receive a B nonimmigrant visa. Moreover, ESTA is a biographical system and cannot be used to run checks against databases that use biometrics as identifiers, such as DHS’s Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT) and FBI’s Next Generation Identification

69 T emporary visitors include aliens who entered with B visas, those who entered under the Guam Visa Waiver Program, and those who entered under the VWP. 70 Visitor admissions from large, non-VWP countries have increased during this period, thereby reducing the proportion of VWP visitor admissions to the United States. For example, in 2018, Brazil, China, and India were among the top 10 overseas countries by visitor volume and accounted for 6.5 million visitors to the United States that year. (NT T O, Non-Resident Arrivals to the United States: Overseas, Canada, Mexico, and International, Trend Line Data —Country of Residence, November 2019, at https://travel.trade.gov/view/m-2017-I-001/index.asp).

71 For more information, see CRS Report R46300, Adding Countries to the Visa Waiver Program: Effects on National Security and Tourism . 72 U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, The Visa Waiver Program: Im plications for U.S. National Security, T estimony of Edward J Ramotowski, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Visa Services, U.S. Department of State, 114th Cong., 1st sess., March 12, 2015.

73 For example, in his testimony before the House Immigration and Claims Subcommittee on February 28, 2002, William S. Norman, President and Chief Executive Officer of the T ravel Industry Association of America, stated that it would take hundreds of new consular staff and tens of millions of dollars to issue visas to visitors currently entering under the VWP. Since Mr. Norman testified, the number of people entering under the VWP has increased by more than 5 million entrants per year.

Congressional Research Service

13

Visa Waiver Program

(NGI).74 While VWP travelers are not checked against these systems before boarding a plane or ship, they are checked against these systems through US-VISIT when they are at a U.S. port of entry.75arguing that the VWP presents a significant security risk. In addition, since terrorism does not have national boundaries, critics of the program contend that the VWP should not be based on particular countries, but should allow visa-free travel for low-risk individuals (e.g., a trusted traveler program).68 Furthermore, while the program has reduced the consular workload in program countries since the officers do not have to issue as many B visas, it has increased the workload of immigration inspectors at ports of entry by shifting the noncitizen's first encounter with a U.S. official to ports of entry.

Security

There is significant debate about whether the VWP increases or decreases national security. As discussed, travelers under the VWP do not undergo the screening traditionally required to receive a B nonimmigrant visa. While the ESTA system has increased the security of the VWP, it is a name-based system and cannot be used to run checks against databases that use biometrics such as DHS's Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT) and FBI's Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS).69 (Travelers are checked against these systems through US-VISIT when they enter the United States.)70 In addition, some contend that the relaxed documentary requirements of the VWP In addition, some contend that the relaxed documentary requirements of the VWP

increase immigration fraud and decrease border security.71

Nonetheless, others security.76

Others argue that the VWP enhances security by setting standards for travel documents and information sharing, and that the program promotes economic growth and cultural ties.72.77 For example, all al travelers entering under the VWP must present e-passports, which tend to be more difficult to alter than other types of passports.73 Furthermore78 Unlike ESTA

authorization, many B visas are valid for 10 years79 and are not continuously vetted.80

Another concern about the national security implications of the program centers on DHS’, many B visas are valid for 10 years,74 and it is possible that a person's circumstances or allegiances could change during that time. In other words, a person from a non-VWP country could become radicalized and the visa may still be valid.

Another concern about the security of the program centers on DHS's ability to conduct reviews of the current VWP countries. In 2002, Congress mandated that DHS evaluate each VWP country every two years to make sure that their continued participation was in the

security, law enforcement, and immigration interests of the United States.7581 In a review of the Visa Waiver Program Office'’s (VWPO'’s) administration of the VWP, the DHS'’s Office of the Inspector General found that as of July 2012, there were 11 (out of 36) reports that exceeded the congressionallycongressional y mandated two-year reporting cycle.76 A GAO82 A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that as of October 31, 2015, approximately 25% of the most recent reports

were submitted or remained outstanding at least five months past the statutory deadline. Since then, DHS has made progress in meeting the mandated two-year reporting cycle, but some gaps

remain.83

74 IDENT is the primary DHS-wide system for the biometric identification and verification of individuals encountered in DHS mission-related processes. NGI is a DHS-wide system for the storage and processing of biometric and limited biographic information. For more information on IDENT , see Department of Homeland Security, Privacy Impact Assessm ent for the Autom ated Biom etric Identification System (IDENT) , July 31, 2006, p. 2, at http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/privacy/privacy_pia_usvisit_ident_final.pdf. For more information on NGI, see Federal Bureau of Investigation, Next Generation Identification (NGI), at https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/fingerprints-and-other-biometrics/ngi.

75 CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry. 76 For an example of this argument, see “Congressman Claims Allowing Poland Visa-Free T ravel to the US Would Pose Security T hreat,” workpermit.com, June 20, 2012, at http://www.workpermit.com/news/2012-06-20/us/congressman-claims-allowing-poland-visa-free-travel-to-us-would-pose-security-threat.htm. 77 For an example of this argument, see Heritage Foundation, The Visa Waiver Program: A Security Partnership, Fact Sheet #66, Washington, DC, June 25, 2010.

78 T here is not a specific requirement to present an e-passport when entering under the VWP. Any passports issued after October 26, 2006, and used by VWP travelers to enter the United States are required to have integrated chips with information from the dat a page (i.e., e-passports). Most passports are valid for 10 years, and thus, it is likely that by October 2016, all VWP entrants had e-passports. 79 T he length of validity of a visa is mostly dependent on reciprocity with the United States (i.e., that visas from that country for U.S. citizens are valid for the same period of time). For a full list of reciprocity schedules, see Department of State, U.S. Visa: Reciprocity and Civil Docum ents by Country, at https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/Visa-Reciprocity-and-Civil-Documents-by-Country.html.

80 CBP screens travelers on nonimmigrant visitor visas at ports of entry each time they enter the United States. 81 P.L. 107-53, §711. 82 VWPO cited a number of reasons for the reporting delays, including inadequate staffing of the office to manage the workload, and not receiving intelligence assessments in a timely manner. However, VWPO officials stated that “these delays have not posed any undue risks or threats to U.S. security interests, since any issues within a VWP country that might affect its continued compliance with VWP requirements are continuously monitored.” Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Inspector General, The Visa Waiver Program , OIG-13-07, Washington, DC, November 2, 2012, p. 12, http://www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/Mgmt/2013/OIG_13-07_Nov12.pdf.

83 According to GAO,

In 2018, DHS completed a strategic review of the reporting process to better distribute the

Congressional Research Service

14

Visa Waiver Program

were submitted or remained outstanding at least five months past the statutory deadline.77

Administration Initiated VWP Security Enhancements

In August and November 2015, the Administration announced a series of changes to the VWP to enhance program security. Some of the Administration's changes were codified by the Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act (P.L. 114-113). See "Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act (H.R. 158/Miller and S. 2362/Johnson) and Defend America Act (S. 2435/Kirk)" for a full discussion of the legislation.

In August 2015, the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Jeh C. Johnson, announced an intention to implement new security measures in the VWP.78 Most significant among them were

- requiring e-passports of all VWP travelers coming to the United States,

- requiring VWP countries to use the INTERPOL Stolen and Lost Travel Document (SLTD) database to screen travelers crossing a VWP country's borders, and

- negotiating for the expanded use of U.S. federal air marshals on international flights from VWP countries to the United States.

Additionally, on November 30 the Administration announced more changes to the VWP meant to enhance security. These changes included

- modifying ESTA to capture information regarding any past travel to countries constituting a terrorist safe haven;

- accelerating the review process for VWP countries;

- requiring, within 60 days, that DHS report to the President on possible pilot programs designed to assess the collection and use of biometrics (fingerprints and/or photographs), and on any countries that are deficient in key areas of cooperation, along with recommended options to engender compliance;

- requiring, within 60 days, that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) provide an evaluation to the President on the terrorism information sharing that occurs between the United States and VWP countries, and identifying options to mitigate any deficiencies;

- offering assistance to countries to better facilitate terrorism information sharing, specifically to include the use of biometrics,79 and deploying "Foreign Fighter Surge Teams" to work with countries to counter terrorist travel;80 and

- expanding and promoting the use of the Global Entry program (a trusted traveler program),81 which includes biometric checks within VWP countries.

Debate over Biometric Exit Capacity

Debate over Biometric Exit Capacity

As discussed, the Secretary of DHS'Homeland Security’s authority to waive the nonimmigrant visa refusal rate has been suspended until the air exit system is able to match an alien's biometric ’s biometric information with relevant watch lists and manifest information.84 Some contend that the current biographic system provides suitable data for most security and immigration enforcement