Introduction

In General

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF), also called the Lightning II, is a strike fighter airplane being procured in different versions for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy. The F-35 program is DOD's largest weapon procurement program in terms of total estimated acquisition cost. Current Department of Defense (DOD) plans call for acquiring a total of 2,456 F-35s1 for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy at an estimated total acquisition cost, as of December, 2018, of about $340.5 billion in constant (i.e., inflation-adjusted) FY2012 dollars.2 U.S. allies are expected to purchase hundreds of additional F-35s, and eight foreign nations are cost-sharing partners in the program.

The Administration's proposed FY2021 defense budget requested about $11.4 billion in procurement funding for the F-35 program. This would fund the procurement of 48 F-35As for the Air Force, 10 F-35Bs for the Marine Corps, 20 F-35Cs for the Navy and Marines, advance procurement for future aircraft, and continuing modifications.

The proposed budget also requested about $1.7 billion for F-35 research and development.

Background

The F-35 in Brief

In General

The Joint Strike Fighter was conceived as a relatively affordable fifth-generation aircraft3 that could be procured in highly common versions for the Air Force and the Navy. Initially, the Marine Corps was developing its own aircraft to replace the AV-8B Harrier, but in 1994, Congress mandated that the Marine effort be merged with the Air Force/Navy program in order to avoid the higher costs of developing, procuring, operating, and supporting three separate tactical aircraft designs to meet the services' similar, but not identical, operational needs.4

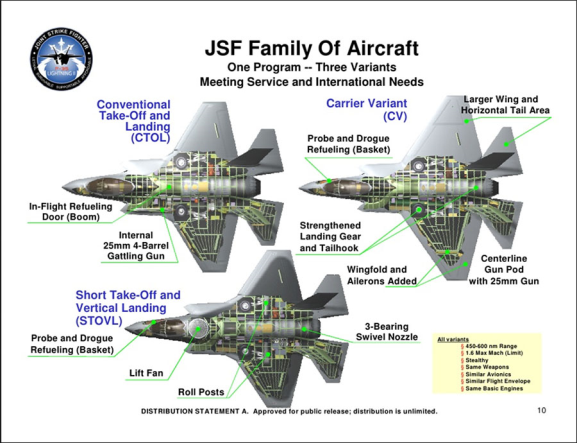

All three versions of the F-35 will be single-seat aircraft with the ability to go supersonic for short periods and advanced stealth characteristics. The three versions will vary in their combat ranges and payloads (see the Appendix). All three are to carry their primary weapons internally to maintain a stealthy radar signature. Additional weapons can be carried externally on missions requiring less stealth.

|

Three Service Versions

From a common airframe and powerplant core, the F-35 is being procured in three distinct versions tailored to the varied needs of the military services. Differences among the aircraft include the manner of takeoff and landing, fuel capacity, and carrier suitability, among others.

Air Force CTOL Version (F-35A)

The Air Force plans to procure 1,763 F-35As, a conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL) version of the aircraft. F-35As are to replace Air Force F-16 fighters and A-10 attack aircraft, and possibly F-15 fighters.5 The F-35A is intended to be a more affordable complement to the Air Force's F-22 Raptor air superiority fighter.6 The F-35A is not as stealthy7 nor as capable in air-to-air combat as the F-22, but it is designed to be more capable in air-to-ground combat than the F-22, and stealthier than the F-16.

|

What Is Stealth? "Stealthy" or "low-observable" aircraft are those designed to be difficult for an enemy to detect. This characteristic most often takes the form of reducing an aircraft's radar signature through careful shaping of the airframe, special coatings, gap sealing, and other measures. Stealth also includes reducing the aircraft's signature in other ways, as adversaries could try to detect engine heat, electromagnetic emissions from the aircraft's radars or communications gear, and other signatures. Minimizing these signatures is not without penalty. Shaping an aircraft for stealth leads in a different direction from shaping for speed. Shrouding engines and/or using smaller powerplants reduces performance; reducing electromagnetic signatures may introduce compromises in design and tactics. Stealthy coatings, access port designs, and seals may require higher maintenance time and cost than more conventional aircraft. |

If the F-15/F-16 combination represented the Air Force's earlier-generation "high-low" mix of air superiority fighters and more-affordable dual-role aircraft, the F-22/F-35A combination might be viewed as the Air Force's intended future high-low mix.8 The Air Force states that "The F-22A and F-35 each possess unique, complementary, and essential capabilities that together provide the synergistic effects required to maintain that margin of superiority across the spectrum of conflict…. Legacy 4th generation aircraft simply cannot survive to operate and achieve the effects necessary to win in an integrated, anti-access environment."9

Marine Corps STOVL Version (F-35B)

The Marine Corps plans to procure 353 F-35Bs, a short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) version of the aircraft.10 F-35Bs are to replace Marine Corps AV-8B Harrier vertical/short takeoff and landing attack aircraft and Marine Corps F/A-18A/B/C/D strike fighters, which are CTOL aircraft. The Marine Corps decided to not procure the newer F/A-18E/F strike fighter11 and instead wait for the F-35B in part because the F/A-18E/F is a CTOL aircraft, and the Marine Corps prefers aircraft capable of vertical operations. The Department of the Navy states that "The Marine Corps intends to leverage the F-35B's sophisticated sensor suite and very low observable, fifth generation strike fighter capabilities, particularly in the area of data collection, to support the Marine Air Ground Task Force well beyond the abilities of today's strike and EW [electronic warfare] assets."12

Navy Carrier-Suitable Version (F-35C)

The Navy plans to procure 273 F-35Cs, a carrier-suitable CTOL version of the aircraft, and the Marines will also procure 67 F-35Cs.13 The F-35C is also known as the "CV" version of the F-35; CV is the naval designation for aircraft carrier. The Navy plans in the future to operate carrier air wings featuring a combination of F/A-18E/Fs (which the Navy has been procuring since FY1997) and F-35Cs. The F/A-18E/F is generally considered a fourth-generation strike fighter.14 The F-35C is to be the Navy's first aircraft designed for stealth, a contrast with the Air Force, which has operated stealthy bombers and fighters for decades. The F/A-18E/F, which is less expensive to procure than the F-35C, incorporates a few stealth features, but the F-35C is stealthier. The Department of the Navy states that "the commonality designed into the joint F-35 program will minimize acquisition and operating costs of Navy and Marine Corps tactical aircraft, and allow enhanced interoperability with our sister Service, the United States Air Force, and the eight partner nations participating in the development of this aircraft."15

Engine

The F-35 is powered by the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine, which was derived from the F-22's F119 engine. The F135 is produced in Pratt & Whitney's facilities in East Hartford and Middletown, CT.16 Rolls-Royce builds the vertical lift system for the F-35B as a subcontractor to Pratt & Whitney.

Consistent with congressional direction for the FY1996 defense budget, DOD established a program to develop an alternate engine for the F-35. The alternate engine, the F136, was developed by a team consisting of GE Transportation—Aircraft Engines of Cincinnati, OH, and Rolls-Royce PLC of Bristol, England, and Indianapolis, IN. The F136 was a derivative of the F120 engine originally developed to compete with the F119 engine for the F-22 program.

DOD included the F-35 alternate engine program in its proposed budgets through FY2006, although Congress in certain years increased funding for the program above the requested amount and/or included bill and report language supporting the program.

The George W. Bush Administration proposed terminating the alternate engine program in FY2007, FY2008, and FY2009. The Obama Administration did likewise in FY2010. Congress rejected these proposals and provided funding, bill language, and report language to continue the program.

The General Electric/Rolls Royce Fighter Engine Team ended its effort to provide an alternate engine on December 2, 2011.

Fuller details of the alternate engine program and issues for Congress arising from it are detailed in CRS Report R41131, F-35 Alternate Engine Program: Background and Issues for Congress.

Current Program Status

The F-35 is currently in low-rate initial production, with 500 aircraft delivered as of February 2020. At least 353 of those were in U.S. service.17 Four to five aircraft are currently delivered each month. The production rate had been scheduled to increase to 120 per year by 2019.18 In keeping with the acquisition plan that overlapped development and production (known as "concurrency"), the F-35 was also in system development and demonstration (SDD), with testing and software development ongoing, from October 2001 until April 11, 2018. The SDD phase will formally continue until the end of Initial Operational Test and Evaluation, when a "Milestone C" full-rate production decision will be made.19 DOT&E approved entering formal IOT&E on December 3, 2018.20 The full-rate production decision is expected in FY2021.21

Recent Developments

Significant developments since the previous major edition of this report (April 23, 2018) include the following, many of which are discussed in greater detail later in the report:

Lots 12-14 Agreed To

On June 10, 2019, DOD and Lockheed Martin reached initial agreement on F-35 production lot 12, with options for lots 13 and 14. The deal would encompass 478 aircraft for $34 billion, including sales to international partners. 22 On October 29, 2019, negotiations were concluded with 149, 160, and 169 aircraft in the respective lots.23

Proposed Multiyear Procurement

In the December 2017 Selected Acquisition Report, DOD disclosed an intention to acquire F-35s through multiyear contracting.

From FY 2021 to the end of the program, the USAF production profile assumes one 3-year multi-year procurement (FY 2021-FY 2023) followed by successive 5-year multi-year procurements beginning in FY2024, with the required EOQ investments and associated savings. The Department of Navy (DoN) did not include EOQ funding in the PB 2019 submission for a multiyear in FY 2021-2023 for either the F-35B or F-35C. The DoN plans to reassess that decision in the coming FY 2020 budget cycle. Therefore, the DoN PB 2019 production profile assumes annual procurements from FY 2021-2023, followed by successive 5-year multi-year procurements from FY 2024 to the end of the program with necessary EOQ investments and associated savings.24

Subsequent hearings considered the merits of multiyear contracting, but Congress has yet to grant that authority. The FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 116-92) authorized economic order quantity contracting and buy-to-budget acquisition, a variation on multiyear contracting. 25 For a discussion of the differences, see "F-35 Block Buy," below.

Potential Change in Marine Corps Procurement

On March 23, 2020, the Marine Corps released a "New Force Design Initiative" outlining proposed changes to its force structure. The proposal included reducing the primary aircraft authorization (PAA) of Marine F-35 squadrons from 16 to 10 each. This would affect nine F-35B squadrons (five other active and two reserve F-35B squadrons were already planned to be at 10 PAA).26 The Corps also has four F-35C squadrons, but those had also previously been planned for 10 PAA.27 The Marine proposal would appear to require 54 fewer F-35Bs than in the existing program of record, currently 353 F-35Bs and 67 F-35Cs.28 The Air Force has also been considering force mix changes that could affect the number of F-35s acquired (see "Issues for Congress," below).

Changes in International Orders

As noted, the F-35 is an international program, with commitments from program partners and other countries to share in the development costs and acquire aircraft. The other nations' plans have varied over time. The December 2019 Selected Acquisition Report projects 764 international sales—632 to partners in the program and 132 through foreign military sales.29 Most recently

- Turkey, which had intended to acquire 100 F-35s, was expelled from the F-35 program after a disagreement with the U.S. over its acquisition and intended fielding of a Russian air defense system.30

- Australia took delivery of its 15th F-35A in April 2019, toward their order for 60 aircraft.31

- Belgium chose the F-35 as its new fighter, with an initial order of 34.32

- Following the election of a new government, Canada canceled its decision to acquire 65 F-35s. Canada has remained a formal partner in the program,33 and the Trudeau government has included the F-35 as a candidate for its follow-on fighter requirement, even modifying its procurement rules to keep the F-35 a viable contender.34

- Poland has confirmed an order for 32 F-35As, the 10th NATO nation to buy the jet.35

- Japan has increased its order by 105 aircraft. According to President Trump, "This purchase would give Japan the largest F-35 fleet of any U.S. ally."36

- Norway declared initial operational capability of its first 15 of the 52 jets it plans to buy.37

- The Netherlands increased its planned buy from 37 to 46 aircraft.38

- The State Department approved the sale of 12 F-35s to Singapore, which planned to buy four with an option for eight more.39

- South Korea will order 20 F-35s in addition to the 40 already on order.40

- The F-35 continues to be evaluated in competitions in Finland and Switzerland.41

Devolution of Joint Program Office

On January 14, 2020, the House Armed Services Committee received a briefing on efforts to reform or eliminate the F-35 Joint Program Office.42 Section 146 of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-328) required DOD to examine alternative management structures for the F-35 program. Proponents argued that the overhead structure of a joint office, even if needed for development of a joint aircraft, is not needed once production has been established, and further that the F-35 is functionally three separate aircraft, with much less commonality than earlier envisioned. "[E]ven the [then] Program Executive Officer of the F-35 Joint Program Office, General Christopher Bogdan, recently admitted the variants are only 20–25 percent common."43 Supporters cited the requirement by the United States to support international customers and to oversee further software and other upgrades as reasons to keep the office in place. The Joint Program Office employs 2,590 people, and the annual cost to operate it is on the order of about $70 million a year.44

In a letter to Congress accompanying that report, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord declared an intention to

begin a deliberate, conditions-based, and risk-informed transition ... from the existing F-35 management structure to an eventual management structure with separate Service-run F-35A and F-35B/C program offices that are integrated with and report through the individual Military Departments.45

Specific timing of the transition, and the responsibilities to be transferred to the services, have not been announced.46

Testing Progress

DOD's annual testing report stated, "The program continued to evaluate and document air system performance against joint contract specification (JCS) requirements in order to close out the SDD contract. As of September 17, 2019, the program had closed out 493 of the 536 capability requirements…. Full closure of the SDD contract may take years to complete." However, "In FY19, DOT&E approved elimination of 29 F-35 test missions (more than 200 sorties) because enough data had already been collected or the test outcome was obvious."47

Overall,

Although the fleet-wide trend in aircraft availability showed modest improvement in 2019, it remains below the target value of 65 percent. No significant portion of the fleet, including the combat-coded fleet, was able to achieve and sustain the DOD mission capable (MC) rate goal of 80 percent. However, individual units have been able to achieve the 80 percent target for short periods during deployed operations.48

Sustainment Cost Issues

Since 2015, operations and sustainment costs for the F-35 fleet's lifecycle have been estimated at more than $1 trillion. The latest F-35 Selected Acquisition Report speaks (in language unusual for that document) to the need to reduce those costs:

At current estimates, the projected F-35 sustainment outlays based upon given planned fleet growth will strain future service O&S budgets. (NB: The previous version had used the words "are too costly.") The prime contractor must embrace much-needed supply chain management affordability initiatives, optimize priorities across the supply chain for spare and new production parts, and enable the exchange of necessary data rights to implement the required stand-up of planned government organic software capabilities.49

A media report indicated that the Air Force was considering reducing its buy of F-35As due to its support costs. "The shortfall would force the service to subtract 590 of the fighter jets from the 1,763 it plans to order ... the Air Force faces an annual bill of about $3.8 billion a year that must be cut back over the coming decade."50 "'If you can afford to buy something but you have to keep it in the parking lot because you can't afford to own and operate it, then it doesn't do you much good,' says F-35 JPO Program Executive Officer Vice Adm. Mat Winter."51 The Air Force has subsequently begun acquiring the F-15EX fighter, in part arguing that its operating costs are significantly lower than the F-35's.52

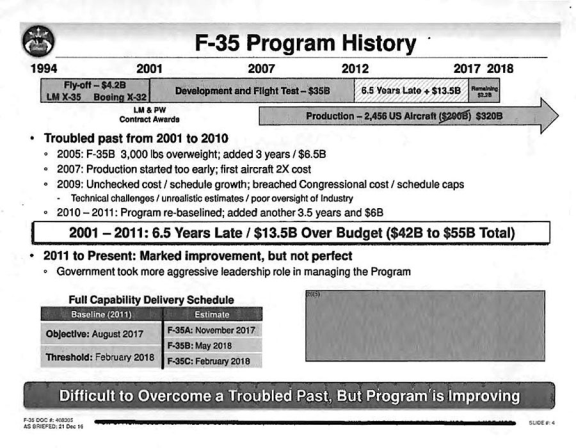

Summary of Program History

On December 21, 2016, then-President-elect Donald J. Trump received a background briefing on the F-35 program, designed to summarize the program's status and challenges. Although the program has progressed since then, it may be interesting to see how DOD characterizes the history of the program when it is not for a public audience. The pertinent chart presented to President-elect Trump is shown in Figure 2. Details of the program history follow.

|

Figure 2. F-35 Program History (As briefed to President-Elect Trump, 2016) |

|

|

Source: Joseph Trevithick, "These Are The Briefings President-Elect Trump Got On The F-35, Air Force One, and Nukes," The War Zone, April 19, 2019, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/27541/these-are-the-briefings-president-elect-trump-got-on-the-f-35-air-force-one-and-nukes. |

F-35 Program Origin and History

The Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program that became the F-35 began in the early 1990s.53 Three different airframe designs were proposed by Boeing, Lockheed, and McDonnell Douglas (teamed with Northrop Grumman and British Aerospace). On November 16, 1996, the Defense Department announced that Boeing and Lockheed Martin had been chosen to compete in the concept demonstration phase of the program, with Pratt and Whitney providing propulsion hardware and engineering support. Boeing and Lockheed were each awarded contracts to build and test-fly two aircraft to demonstrate their competing concepts for all three planned JSF variants.54

The competition between Boeing and Lockheed Martin was closely watched. Given the size of the JSF program and the expectation that the JSF might be the last fighter aircraft program that DOD would initiate for many years, DOD's decision on the JSF program was expected to shape the future of both U.S. tactical aviation and the U.S. tactical aircraft industrial base.

In October 2001, DOD selected the Lockheed design as the winner of the competition, and the JSF program entered the system development and demonstration (SDD) phase, with SDD contracts awarded to Lockheed Martin for the aircraft and Pratt and Whitney for the aircraft's engine. General Electric continued technical efforts related to the development of an alternate engine for competition in the program's production phase.

|

First flown |

Original IOC goal |

IOC |

|

|

F-35A |

December 15, 2006 |

March 2013 |

August 2, 2016 |

|

F-35B |

June 11, 2008 First hover: March 17, 2010 |

March 2012 |

July 31, 2015 |

|

F-35C |

June 6, 2010 |

March 2015 |

February 28, 2019 |

Source: Prepared by CRS based on press reports and DOD testimony.

Note: IOC is Initial Operational Capability (discussed below).

As shown in Table 1, the first flights of an initial version of the F-35A and the F-35B occurred in the first quarter of FY2007 and the third quarter of FY2008, respectively. The first flight of a slightly improved version of the F-35A occurred on November 14, 2009.55 The F-35C first flew on June 6, 2010.56

The F-35B's ability to hover, scheduled for demonstration in November 2009, was shown for the first time on March 17, 2010.57 The first vertical landing took place the next day.58

February 2010 Program Restructuring

In November 2009, DOD's Joint Estimating Team issued a report (called JET II) stating that the F-35 program would need an extra 30 months to complete the SDD phase. In response to JET II, the then-impending Nunn-McCurdy breach, and other developments, on February 24, 2010, Pentagon acquisition chief Ashton Carter issued an Acquisition Decision Memorandum (ADM) restructuring the F-35 program. Key elements of the restructuring included the following:

- Extending the SDD phase by 13 months, thus delaying Milestone C (full-rate production) to November 2015 and adding an extra low-rate initial production (LRIP) lot of aircraft to be purchased during the delay. Carter proposed to make up the difference between JET II's projected 30-month delay and his 13-month schedule by adding three extra early-production aircraft to the test program. It is not clear how extra aircraft could be added promptly if production was already behind schedule.

- Funding the program to the "Revised JET II" (13-month delay) level, implicitly accepting the JET II findings as valid.

- Withholding $614 million in award fees from the contractor for poor performance, while adding incentives to produce more aircraft than planned within the new budget.

- Moving procurement funds to R&D. "More than $2.8 billion that was budgeted earlier to buy the military's next-generation fighter would instead be used to continue its development."59

"Taken together, these forecasts result in the delivery of 122 fewer aircraft over the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), relative to the President's FY 2010 budget baseline," Carter said.60 This reduction led the Navy and Air Force to revise their dates for IOC as noted above.

|

"F-35B 3,000 lbs overweight; added 3 years / $6.5B" A significant issue in early development, noted in Figure 2, was the weight of the F-35B variant. Because the F-35B takes off and lands near-vertically, weight is a particularly critical factor, as aircraft performance with low- to no-airspeed depends directly on the ratio of engine thrust to aircraft weight. The delay was exacerbated by the consolidation of the former JAST and ASTOVL programs, discussed in footnote 53. Normally, in a development program, the most technically simple variant is developed first, and lessons applied while working up to more complicated variants. Because the Marine Corps' Harrier fleet was reaching the end of life before the Air Force and Navy fleets the F-35 was designed to replace, in this case, the most complicated variant—the F-35B—had to be developed first. That meant the technical challenges unique to STOVL aircraft delayed all of the variants. |

March 2010 Nunn-McCurdy Breach

On March 20, 2010, DOD formally announced that the JSF program had exceeded the cost increase limits specified in the Nunn-McCurdy cost containment law, as average procurement unit cost, in FY2002 dollars, had grown 57% to 89% over the original program baseline. Simply put, this requires the Secretary of Defense to notify Congress of the breach, present a plan to correct the program, and to certify that the program is essential to national security before it can continue.61

On June 2, 2010, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics issued an Acquisition Decision Memorandum (ADM) certifying the F-35 Program in accordance with section 2433a of title 10, United States Code. As required by section 2433a, of title 10, Milestone B was rescinded. A Defense Acquisition Board (DAB) was held in November 2010.... No decision was rendered at the November 2010 DAB.... Currently, cumulative cost and schedule pressures result in a critical Nunn-McCurdy breach to both the original (2001) and current (2007) baseline for both the Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC) and Average Procurement Unit Cost (APUC). The breach is currently reported at 78.23% for the PAUC and 80.66% for the APUC against the original baseline and 27.34% for the PAUC and 31.23% for the APUC against the current baseline.62

February 2012 Procurement Stretch

With the FY2013 budget, F-35 acquisition was slowed, with the acquisition of 179 previously planned aircraft being moved to years beyond the FY2013-2017 FYDP "for a total of $15.1 billion in savings."63 Note that this stretch, along with the SDD extension already mentioned, contributed to the "6.5 years late" referenced in Figure 2.

Initial Operational Capability

Congress required a formal declaration of IOCs in Section 155 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (P.L. 112-239). The current dates (by fiscal year) are shown in Table 1.

The F-35A, F-35B, and F-35C were originally scheduled to achieve IOC in March 2013, March 2012, and March 2015, respectively.64 The Marine Corps declared F-35B Initial Operational Capability (IOC) on July 31, 2015. The Air Force declared F-35A IOC on August 2, 2016.65 The Navy declared IOC on February 28, 2019.66

It should be noted that IOC means different things to different services:

F-35A initial operational capability (IOC) shall be declared when the first operational squadron is equipped with 12-24 aircraft, and Airmen are trained, manned, and equipped to conduct basic Close Air Support (CAS), Interdiction, and limited Suppression and Destruction of Enemy Air Defense (SEAD/DEAD) operations in a contested environment. Based on the current F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) schedule, the F-35A will reach the IOC milestone between August 2016 (Objective) and December 2016 (Threshold)....

F-35B IOC shall be declared when the first operational squadron is equipped with 10-16 aircraft, and US Marines are trained, manned, and equipped to conduct CAS, Offensive and Defensive Counter Air, Air Interdiction, Assault Support Escort, and Armed Reconnaissance in concert with Marine Air Ground Task Force resources and capabilities. Based on the current F-35 JPO schedule, the F-35B will reach the IOC milestone between July 2015 (Objective) and December 2015 (Threshold)....

Navy F-35C IOC shall be declared when the first operational squadron is equipped with 10 aircraft, and Navy personnel are trained, manned and equipped to conduct assigned missions. Based on the current F-35 JPO schedule, the F-35C will reach the IOC milestone between August 2018 (Objective) and February 2019 (Threshold).67

Additionally,

Each of the three US services will reach initial operating capability (IOC) with different software packages.

The F-35B will go operational for the US Marines in December 2015 with the Block 2B software, while the Air Force plans on achieving IOC on the F-35A in December 2016 with Block 3I, which is essentially the same software on more powerful hardware. The Navy intends to go operational with the F-35C in February 2019, on the Block 3F software.68

One complication regarding the Navy's operational capability is that the Navy reportedly will not be able to airlift F-35 engines to carriers at sea until the introduction of the CMV-22 carrier onboard delivery aircraft in 2021.69

End of System Development and Demonstration/Entry into IOT&E

The F-35 Joint Program Office declared the 17-year System Development and Demonstration (SDD) effort complete on April 11, 2018. "(T)he developmental flight team has conducted more than 9,200 sorties, accumulated 17,000 flight hours and executed more than 65,000 test points."70 The end of the flight test effort does not mark the actual end of SDD, though; that will occur at Milestone C, following the completion of initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E).

The Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) approved entering formal IOT&E on December 3, 2018. DOT&E notes that the F-35 enters IOT&E with 873 unresolved deficiencies, 13 of which are classified as "Category 1 'must-fix' items that affect safety or combat capability."71 The program's high concurrency means there may be substantial costs to incorporate the lessons of testing: "IOT&E, which provides the most credible means to predict combat performance, likely will not be completed until … over 600 aircraft will already have been built."72

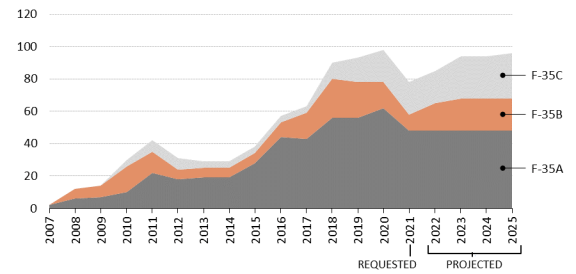

Procurement Quantities

Planned Total Quantities

The F-35 program includes a planned total of 2,456 aircraft for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy. This comprises 13 research and development aircraft and 2,443 production aircraft: 1,763 F-35As for the Air Force, 273 F-35Cs for the Navy, and 67 F-35Cs and 353 F-35Bs for the Marine Corps.73 As noted in "Potential Change in Marine Corps Procurement" above, the Marine Corps recently mooted a change in squadron size that would imply a 54-jet reduction in its planned F-35 fleet, but that has not yet become a validated goal.

Annual Quantities

DOD began procuring F-35s in FY2007. Figure 3 shows F-35 procurement quantities authorized through FY2020, requested procurement quantities for FY2021, and projected requests through the FYDP. The figures in the table do not include 13 research and development aircraft procured with research and development funding. (Quantities for foreign buyers are discussed in the next section.)

|

Figure 3. F-35 Procurement Quantities (Figures shown are for production aircraft; table excludes 14 research and development aircraft) |

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS based on DOD data. |

Previous DOD plans contemplated increasing the procurement rate of F-35As for the Air Force to a sustained rate of 80 aircraft per year by FY2015, and completing the planned procurement of 1,763 F-35As by about FY2034. The current Air Force plan levels procurement at 48 per year beginning in 2020; the 1,763 fleet target has not changed.

Past DOD plans also contemplated increasing the procurement rate of F-35Bs and Cs for the Marine Corps and Navy to a combined sustained rate of 50 aircraft per year by about FY2014, and completing the planned procurement of 680 F-35Bs and Cs by about FY2025. The FY2021 budget submission shows a combined F-35B and -C production rate of 30 per year in 2021, toward a fleet goal of 693.

Low-Rate Initial Production

F-35s are currently produced under Low-Rate Initial Production (LRIP), with agreements reached for the first 14 lots of aircraft. Each LRIP lot includes both U.S. and international partner aircraft.

Contracted unit prices for F-35s have continued to decline with each production lot. "For example, the price (including airframe, engine and profit) of an LRIP Lot 8 aircraft was approximately 3.6 percent less than an LRIP Lot 7 aircraft, and an LRIP Lot 7 aircraft, was 4.2 percent lower than an LRIP Lot 6 aircraft."74

In LRIPs 5, 6, and 7, any cost overruns associated with concurrent development and production would be split equally between the contractor and the government. Prior to LRIP 4, the government bore those costs alone. Beginning with LRIP 8, the contractor is liable for 100% of any cost overrun; if actual cost is lower than the contracted cost, the contractor will receive 80% of the savings, the government 20%.75

|

LRIP Lot |

5a |

6b |

8e |

9f |

10g |

11h |

|

|

F-35A |

22/105 |

23/103 |

19/98 |

19/95 |

42/102 |

44/95 |

102/89 |

|

F-35B |

3/113 |

7/109 |

6/104 |

6/102 |

13/132 |

9/123 |

25/116 |

|

F-35C |

7/125 |

6/120 |

4/116 |

4/116 |

2/132 |

2/122 |

14/108 |

Notes: Aircraft costs for LRIPs 5-8 shown do not include engines. All quantities exclude international orders.

a. Christopher Drew, "Lockheed Profit on F-35 Jets Will Rise With New Contract," The New York Times, December 17, 2012.

b. Tony Capaccio, "Lockheed Gets Approval Of Next F-35 Production Contract," Bloomberg News, July 6, 2012.

c. Amy Butler, "Latest F-35 Deal Targets Unit Cost Below $100 Million," Aviation Week & Space Technology, July 30, 2013.

d. Caitlin Lee, "Latest F-35 contracts mark new strategy to reduce costs," Jane's Defence Weekly, September 29, 2013.

e. Colin Clark, "New F-35 Prices: A: $95M; B: $102M; C: $116M," Breaking Defense, November 21, 2014.

f. Sydney J. Freedberg, Jr., "F-35 'Not Out Of Control': F-35A Prices Drop 5.5%," Breaking Defense, December 19, 2016, https://breakingdefense.com/2016/12/33483/.

g. Lockheed Martin, "Agreement Reached on Lowest Priced F-35s in Program History," press release, February 3, 2017, https://www.f35.com/news/detail/agreement-reached-on-lowest-priced-f-35s-in-program-history.

h. Lockheed Martin, Producing, Operating and Supporting a 5th Generation Fighter, retrieved March 29, 2020, https://www.f35.com/about/cost.

Although previous LRIP contracts had been arrived at through negotiation between the F-35 Joint Program Office and Lockheed Martin, the LRIP 9 contract was not agreed to by both sides. After prolonged negotiation, the government invoked its right to issue a unilateral contract.76

F-35 Block Buy

The LRIP 11 award, incorporating as it does options for lots 12-14, has been labeled a block buy.77 Block buy contracts commit the government to purchasing certain quantities of aircraft over a number of years, which allows the contractor to acquire parts in greater quantity and plan workforce levels in advance, helping to reduce cost. "By purchasing supplies in economic quantities, Lockheed Martin and Pratt & Whitney estimate that 8 percent and 2.3 percent cost savings, respectively, could be achievable."78 A 2018 RAND Corporation analysis offered some of the possible savings from a (then-mooted) block buy.79

|

What Is Block Buy?80 Block buy contracting (BBC) permits DOD to use a single contract for more than one year's worth of procurement of a given kind of item without having to exercise a contract option for each year after the first year. It is similar to multiyear procurement in that DOD needs congressional approval for each use of BBC. BBC differs from MYP in the following ways:

|

"A full block buy, including US jets, could save anywhere from $2 billion to $2.8 billion, according to industry estimates."81 Congressional approval would be required for a U.S. block buy.82

In related developments, Section 141 of the Fiscal Year 2018 National Defense Authorization Act included language authorizing DOD to enter into economic order quantity contracts for advance parts for F-35s to be procured in FY2019 and FY2020, and the FY2020 NDAA (P.L. 116-92) authorized economic order quantity and buy-to-budget for F-35 aircraft.

Program Management

The JSF program is jointly managed and staffed by the Department of the Air Force and the Department of the Navy. Service Acquisition Executive (SAE) responsibility alternates between the two departments. When the Air Force has SAE authority, the F-35 program director is from the Navy, and vice versa. Air Force Lt Gen Eric T. Fick became the F-35 program manager, succeeding Navy Vice Admiral Mathias Winter, on July 11, 2019.83

DOD has announced an intention to reorganize F-35 procurement now that the bulk of development has been completed, with procurement responsibilities moving from a central joint office to the military services. (This is consonant with broader congressional direction to decentralize acquisition and increase the acquisition authority of the military services.84)

As noted, Congress required DOD to examine alternative F-35 management structures.85 Proponents argued that the overhead structure of a joint office, even if useful in overseeing development of a joint aircraft, is not needed once production has been established. Further, they argue that the F-35 is functionally three separate aircraft, with much less commonality than envisioned early in the program. "[E]ven the Program Executive Officer of the F-35 Joint Program Office, General Christopher Bogdan, recently admitted the variants are only 20–25 percent common."86 Supporters cited the requirement by the United States to support international customers and to oversee further software and other upgrades as reasons to keep the office in place.

In a letter to Congress accompanying that report, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord declared an intention to

begin a deliberate, conditions-based, and risk-informed transition ... from the existing F-35 management structure to an eventual management structure with separate Service-run F-35A and F-35B/C program offices that are integrated with and report through the individual Military Departments.87

Specific timing of the transition, and the responsibilities to be transferred to the services, have not been announced.88

Software Development

You can see from its angled lines, the F-35 is a stealth aircraft designed to evade enemy radars. What you can't see is the 24 million lines of software code which turn it into a flying computer. That's what makes this plane such a big deal.89

The F-35's integration of sensors and weapons, both internally and with other aircraft, is touted as its most distinctive aspect. As that integration is primarily realized through complex software, it may not be surprising to observe that writing, validating, and debugging that software is among the program's greatest challenges. F-35 operating software is released in blocks, with additional capabilities added from one block to the next.

I'm concerned about the software, the operational software.... And I'm concerned about the ALIS [Autonomic Logistics Information System], that is another software system, basically that will provide the logistics support to the systems. – Frank Kendall, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics.90

Currently, the ultimate planned software release is Block 4, which will be the first block to contain full combat capability and a complete weapons suite, including conventional weapons like the Small Diameter Bomb II and nuclear capability. However, Block 4 will not be available to all F-35s; it will require aircraft upgraded with Technical Refresh-3 (TR-3) hardware.91 New F-35s are expected to begin delivering with TR-3 in lot 15, scheduled for CY2023.92

|

Block |

Attributes |

Released |

|

2B |

Required for Marine IOC |

March, 2015 |

|

3i (initial) |

Required for USAF IOC; basic aircraft operation and navigation, some combat capability. |

August, 2016 |

|

3F (final) (now called 30PXX) |

Required for Navy IOC; expanded combat capability with basic weapons. |

September, 2017 |

|

4 |

Adds nuclear weapons capability (among other things) |

Under development |

Kendall's concern was echoed by then-F-35 program manager Air Force Lieutenant General Christopher Bogdan. In testimony to the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces, he noted that it is the

"complexity of the software that worries us the most.... Software development is always really, really tricky... We are going to try and do things in the final block of this capability that are really hard to do." Among them is forming software that can share the same threat picture among multiple ships across the battlefield, allowing for more coordinated attacks.93

C2D2 Program

Beginning in 2018, upgrades to the F-35's software and other capabilities were combined in an effort now known as Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2). C2D2's principal task is developing the Block 4 software, but it includes other elements like TR-3 and dual (nuclear) capability, discussed below. According to the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation,

The current Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) process has not been able to keep pace with adding new increments of capability as planned. Software changes, intended to introduce new capabilities or fix deficiencies, often introduced stability problems and adversely affected other functionality. 94

According to the Government Accountability Office, that development is now behind schedule and over budget:

Since May 2019, we found the program office has increased its estimate by about 14 percent, to $12.1 billion, primarily due to schedule delays. The program now expects to extend the delivery of Block 4 capabilities by 2 additional years, through 2026… Additionally, most of the capabilities the F-35 program planned to deliver in 2019 were delayed.95

C2D2 Program Oversight

A shown in Table 4, the FY2021 budget submission projects the cost of C2D2 as $7.0 billion to FY2025. International partners may contribute to this development effort; according to then-F-35 program executive officer Vice Admiral Mathias Winter in 2018, consortium partners were prepared to contribute $3.7 billion toward Block 4 software development through 2024.96 Some in Congress argue that a program of that size should part with traditional procurement practice for an upgrade and be run as a separate Major Defense Acquisition Program, with its own budget line and the concomitant reporting requirements; language to this effect was included in the Senate's version of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act. This is discussed further in "Issues for Congress," below.

|

FY21 |

FY22 |

FY23 |

FY24 |

FY25 |

Total |

||

|

F-35A |

785.336 |

549.279 |

450.915 |

521.012 |

586.709 |

2893.251 |

|

|

F-35B |

379.549 |

323.597 |

294.404 |

283.981 |

244.932 |

1526.463 |

|

|

F-35C |

330.386 |

261.923 |

246.494 |

265.615 |

248.487 |

1352.905 |

|

|

International |

359.626 |

285.969 |

211.292 |

208.053 |

177.542 |

1242.482 |

|

|

All |

7015.101 |

The $7.0 billion specifically designated for C2D2 may not be the total funding for the program, as Vice Admiral Winter had earlier indicated that just the cost for the Block 4 upgrade was to be more than $10 billion through FY2024.97

Autonomic Logistics Information System

The issues cited above focused on software development for the F-35's onboard mission systems. A supporting system, the Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), also requires extensive software development and testing. "ALIS is at the core of operations, maintenance and supply-chain management for the F-35, providing a constant stream of data from the plane to supporting staff."98 The pace of ALIS development has been cited by service officials as hindering F-35 deployment.

DOD's Director of Operational Test & Evaluation stated that

Although the program released several new versions of ALIS in 2019 that improved ALIS usability, these improvements did not eliminate the major problems in ALIS design and implementation. These deficiencies caused delays in troubleshooting and returning broken aircraft to mission capable status.99

GAO reported that

ALIS may not be deployable: ALIS requires server connectivity and the necessary infrastructure to provide power to the system. The Marine Corps, which often deploys to austere locations, declared in July 2015 its ability to operate and deploy the F-35 without conducting deployability tests of ALIS. A newer version of ALIS was put into operation in the summer of 2015, but DOD has not yet completed comprehensive deployability tests.

ALIS does not have redundant infrastructure: ALIS's current design results in all F-35 data produced across the U.S. fleet to be routed to a Central Point of Entry and then to ALIS's main operating unit with no backup system or redundancy. If either of these fail, it could take the entire F-35 fleet offline.100

To date, the F-35's operators have been coping with ALIS's shortcomings. "Most capabilities function as intended only with a high level of manual effort by ALIS administrators and maintenance personnel. Manual work-arounds are often needed to complete tasks designed to be automated."101

Air Force Lt. Gen. Chris Bogdan told reporters that the plane could fly without the $16.7 billion ... ALIS for at least 30 days. The software, which runs on ground computers, not the plane itself, manages the aircraft's supply chain, aircraft configuration, fault diagnostics, mission planning, and debriefing – none of which are critical to combat flight.102

ALIS Replacement

Some of the problems with ALIS reportedly stem from its 1990s-based architecture.103 DOD is replacing ALIS with a new technology system called ODIN, for Operational Data Integrated Network.104

ODIN is designed to be more user-friendly and less prone to error. Program officials decided to replace ALIS rather than upgrading it further in order to take advantage of modern programming architectures.

We have old hardware, we have old operating systems… if we were ever going to get to a modern software architecture, modernizing ALIS wasn't going to get us there. [Replacement is] so that we can leverage all the things that have happened in software development over the last couple of decades.

The code in this airplane is old… it's frankly going to take a couple of years for this to all iron itself out.105

ODIN will work with F-35s that have the Technical Refresh-3 hardware package, beginning with acquisition Lot 15 in 2023. That package includes a new integrated core processor, panoramic cockpit display, and an enhanced memory unit. The company intends to incorporate TR3 in F-35s starting in Lot 15, with those jets rolling off the production lot in 2023.106 Earlier F-35s will, at least initially, continue with ALIS version 3.5, which is being refreshed "roughly every 120 days or so." "ALIS 3.5 is going to be the core … capability for our sustainers until we get ODIN up and online."107

Dual Capability

Some F-35As will be dual capable aircraft (DCA), meaning that they will have the ability to deliver nuclear ordnance. Dual capability is expected to be included in the Block 4 software release, with initial capability for the B61-12 weapon.108 The F-35A DCA is scheduled to achieve nuclear certification in January, 2023.109

Funding for DCA development had been carried in Air Force PE 0207142F, under F-35 Squadrons. In the FY2021 budget request, it appears as part of C2D2, PE 0604840F. Requested funding in FY2021 is $106.136 million, with a total projected request through 2025 of $186.678 million.

Cost and Funding110

Total Program Acquisition Cost111

As of December 2019, the total estimated acquisition cost (the sum of development, procurement, and military construction [MilCon] costs) of the F-35 program in constant (i.e., inflation-adjusted) FY2012 dollars was about $340.5 billion, including about $70.3 billion in research and development, about $265.6 billion in procurement, and about $4.5 billion in MilCon.112

In then-year dollars (meaning dollars from various years that are not adjusted for inflation), the figures are about $428.3 billion, including about $67.9 billion in research and development, about $355.3 billion in procurement, and about $5.2 billion in military construction.

Prior-Year Funding

Through FY2018, the F-35 program has received a total of roughly $137.6 billion of funding in then-year dollars, including about $56.9 billion in research and development, about $78.2 billion in procurement, and approximately $2.4 billion in military construction.

Unit Costs

As of December 2018, the F-35 program had a program acquisition unit cost (or PAUC, meaning total acquisition cost divided by the 2,470 research and development and procurement aircraft) of about $118.3 million and an average procurement unit cost (or APUC, meaning total procurement cost divided by the 2,456 production aircraft) of $94.0 million, in constant FY2012 dollars.

However, this reflects the cost of the aircraft without its engine, as the engine program was broken out as a separate reporting line in 2011.

As of December 2019, the F-35 engine program had a program acquisition unit cost of about $22.0 million and an average procurement unit cost of $16.7 million in constant FY2012 dollars. Just as the reported airframe costs represent a program average and do not discriminate among the variants, those engine costs do not discriminate between the single engines used in the F-35A and C and the more expensive engine/lift fan combination for the F-35B.

However, beginning in December 2016, DOD's Selected Acquisition Reports broke out unit recurring flyaway costs of the three engines as well as the separate airframes, as follows:

|

$M (2012) |

F-35A |

F-35B |

F-35C |

|

Airframe |

69.5 |

80.0 |

79.5 |

|

Engine |

11.1 |

27.0 |

11.2 |

|

Total |

80.6 |

107.2 |

90.7 |

Source: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Selected Acquisition Report (SAR): F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Aircraft (F-35), March 17, 2019.

Note: Versions of this chart prior to FY2018 assumed 2443 US sales and 612-673 international sales rather than 2456/741.

Critics note that the costs reported in the Selected Acquisition Reports contain a number of assumptions about future inflation rates, production learning curves, and other factors, and argue that these figures do not accurately represent the true cost of developing and acquiring the F-35.113

Other Cost Issues

Acquisition Cost and Long-Term Affordability

Over time, as the program has matured and unit costs have decreased in succeeding procurement lots, attention on F-35 costs has shifted. The acquisition cost of the program is still large, and as DOD considers the prospect of flat budgets for the future, other programs increasingly compete with the F-35 for budget share. The Government Accountability Office, for example, has increasingly questioned DOD's ability to afford the current F-35 program given other demands on budgets. This is a contrast to earlier reports, which focused more on the program's ability to meet its cost targets.

More recently, though, attention has moved to long-term affordability and sustainment costs, as discussed below.

Unit Cost Projections

The F-35 program had long established a goal of making the F-35 cost-competitive with previous-generation aircraft. (It should be noted that the articles cited below reference the cost of the F-35A, the simplest model.)

F-35 fighter jets will sell for as little as $80 million in five years, according to the Pentagon official running the program.

"The cost of an F-35A in 2019 will be somewhere between $80 and $85 million, with an engine, with profit, with inflation," U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Christopher Bogdan, the Pentagon's manager of the program, told reporters in Canberra today.114

That article dated from 2014. More recently, efforts were increased to reach the same target:

[Lockheed Martin] will invest up to $170 million over the next two years to extend its existing "Blueprint for Affordability" measure ... to drive down the unit cost of an F-35A to $85 million by 2019.115

As noted in Table 5, the average unit flyaway cost of an F-35A is officially projected at $80.6 million in constant 2012 dollars. However, according to the recent agreement on F-35 production lot 11, an F-35A "is set to decrease from a Lot 11 price of $89.2 million to $82.4 million in Lot 12; $79.2 million in Lot 13; and $77.9 million in Lot 14."116

Engine Costs

In 2013, engine maker Pratt & Whitney embarked on a program to reduce the F-35 engine's cost.117 Following release of data showing the "cost of acquiring the planned 2,443 airframes and associated systems rose 1%, while engine costs climbed 6.7%,"118 the program manager reportedly singled out Pratt for criticism "after having improved relations with the F-35's prime contractor, Lockheed Martin Corp., securing lower prices for each batch of new airframes and closing deals far quicker than in the past."119

Subsequently, Pratt & Whitney has signed contracts for engines through LRIP 11 that show a steady percentage decrease in cost. The LRIP 11 announcement did not included a dollar figure for the engines, instead citing percentage decreases in cost. "[Pratt & Whitney] is claiming competitive privilege in its sole-source deal for F-35 engines in not releasing its actual numbers."120

Pratt says that "in general, the unit recurring flyaway (URF) price for the 110 LRIP Lot 11 conventional takeoff and landing and carrier variant propulsion systems will be reduced 0.34 percent from the previously negotiated LRIP Lot 10 URF. The URF price for the 25 LRIP Lot 11 short takeoff and vertical landing propulsion systems (including lift systems) will be reduced 3.39 percent from the previously negotiated LRIP Lot 10 URF."121

The issue of engine cost transparency is addressed in "Issues for Congress," below.

Anticipated Upgrade Costs

The degree of concurrency in the F-35 program, in which aircraft are being produced while the design is still being revised through testing, has made upgrades to early-production aircraft inevitable. "For all F-35 variants, structural and durability testing led to significant discoveries requiring repairs and modifications to production designs, some as late as Lot 12 aircraft, and retrofits to fielded aircraft."122

The cost of those upgrades may vary, depending on what revisions are made during the testing process. However, the cost of such upgrades is not included in the negotiated price of each production lot.

The first F-35As, for example, were loaded with a basic software release (Block 1B) that provides basic aircraft control, but does not have the degree of sensor fusion or weapons integration expected in later blocks. "The initial estimate for modifying early-production F-35As from a basic configuration to a capable warfighting level is $6 million per jet, plus other associated expenses not included in that figure."123 That would make the current cost of upgrading the earliest F-35As to Block 3F about $100 million. In order to increase capability, the Air Force intends to upgrade the aircraft step-by-step as new software releases become available rather than waiting and jumping to the final release of Block 3F.

The cost of the major upgrade to Block 4 is discussed in "Issues for Congress," below.

Operating and Support Costs

Since 2015, Selected Acquisition Report projected lifetime operating and sustainment costs for the F-35 fleet have been estimated at over $1 trillion,124 "which DOD officials have deemed unaffordable. The program's long term sustainment estimates reflect assumptions about key cost drivers that the program does not control, including fuel costs, labor costs, and inflation rates."125 "The eye-popping estimate has raised hackles at the Defense Department and on Capitol Hill since it was disclosed in 2011. It covers the cost of fuel, spare parts, logistics support and repairs."126 It may be worth noting that "the F-35 was ... the first big Pentagon weapons program to be evaluated using a 50-year lifetime cost estimate—about 20 years longer than most programs—which made the program seem artificially more expensive."127

Operations and sustainment costs as of the December 2019 Selected Acquisition Report were reported at $630.5 billion in 2012 dollars (or $1.2 trillion in then-year dollars).

"The operation and sustainment cost is a bigger issue," (then-Air Force acquisition chief William) LaPlante said. "It's the one that will say whether or not we can afford (the F-35) in the longer run."128

Operations costs are being addressed on several fronts, including changes in training, basing, support, and other approaches.

To attack this problem, the F-35 program office in October 2013 set up a "cost war room" in Arlington, Va.... A team of government and contractor representatives assigned to the cost war room are investigating 48 different ways to reduce expenses. They are also studying options for future repair and maintenance of F-35 aircraft in the United States and abroad.129

The U.S. Air Force is looking to slash the number of locations where it will base F-35 Joint Strike Fighter squadrons to bring down the jet's estimated trillion-dollar sustainment costs.... "When you reduce the number of bases from 40 to the low 30s, you end up reducing your footprint, making more efficient the long-term sustainment," David Van Buren, the service's acquisition executive, said in a March 2 exit interview at the Pentagon.130

More recently, "Lockheed, Northrop and BAE are also starting a 'sustainment cost reduction initiative' aimed at cutting operations and maintenance expenses by 10 percent during fiscal 2018 through fiscal 2022. The vendors will invest $250 million and hope to reap at least $1 billion in savings over five years."131

Manufacturing Locations

The F-35 is manufactured in several locations. Lockheed Martin builds the aircraft's forward section in Fort Worth, TX. Northrop Grumman builds the midsection in Palmdale, CA, and the tail is built by BAE Systems in the United Kingdom.132 Final assembly of these components takes place in Fort Worth. Final assembly and checkout facilities have also been established in Cameri, Italy, and Nagoya, Japan.

The Pratt & Whitney F135 engine for the F-35 is produced in East Hartford and Middletown, CT. Rolls-Royce builds the F-35B lift system in Indianapolis, IN.

Basing

On December 21, 2017, the Air Force announced Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth, TX, as the preferred alternative for the first F-35A reserve component base. Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, AZ; Homestead Air Reserve Base, FL; and Whiteman AFB, MO, were also candidate bases. At the same time, Truax Field, WI, and Dannelly Field, AL, were announced as the next Air National Guard F-35A bases, with aircraft slated to arrive in 2023. Gowen Field ANGB, ID; Selfridge ANGB, MI; and Jacksonville Air Guard Station, FL, were also considered. Burlington Air National Guard Base, VT, had previously been selected.133

Active component F-35As had already been announced as going to Hill AFB, UT, and RAF Lakenheath, England. Eielson AFB, AK, had earlier been announced as the preferred base for the first overseas F-35 squadron.134 Luke AFB, AZ, and Eglin AFB, FL, are the main F-35 training bases. F-35As also operate from Edwards AFB, CA, and Nellis AFB, NV.

In the United States, Marine F-35s are based at Marine Corps Air Stations Yuma, AZ, and Beaufort, SC. Navy F-35s fly from Naval Air Stations Lemoore, CA, and Patuxent River, MD.

International Participation

In General

The F-35 program is DOD's largest international cooperative program. DOD has actively pursued allied participation as a way to defray some of the cost of developing and producing the aircraft, and to "prime the pump" for export sales of the aircraft.135 Allies in turn view participation in the F-35 program as an affordable way to acquire a fifth-generation strike fighter, technical knowledge in areas such as stealth, and industrial opportunities for domestic firms.

Eight allied countries—the United Kingdom, Canada, Denmark, The Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Turkey, and Australia—initially participated in the F-35 program under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the SDD and Production, Sustainment, and Follow-On Development (PSFD) phases of the program. These eight countries have contributed varying amounts of research and development funding to the program, receiving in return various levels of participation in the program. International partners are also assisting with Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E), a subset of SDD.136 The partner countries are expected to purchase hundreds of F-35s, with the United Kingdom's 138 being the largest anticipated foreign fleet.137 As noted, Turkey's participation in the F-35 program was subsequently curtailed. The circumstances of that change are summarized below and described in CRS Report R44000, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations In Brief, and CRS Report R41368, Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations, both by Jim Zanotti and Clayton Thomas.

|

Effects of Turkish expulsion Turkey's removal affected the F-35 program in two principal areas. The first was a potential reduction in the projected number of F-35s to be produced, although as other customers have appeared and the U.S. Congress ordered Turkey's F-35s be reallocated to the U.S. Air Force, the net effect has yet to be determined. The other effects were the requirement to find replacements for the main engine overhaul facility for European F-35s, which was to have been hosted in Turkey and will now go to Norway and the Netherlands, and for Turkish suppliers participating in the program, providing parts estimated at between $5 billion-$6 billion in value over 20 years.138 "According to U.S. officials, most of the supply chain handled by Turkish companies was due to move elsewhere by March 2020, with a few contracts in Turkey continuing until later in the year. The cost of shifting the supply chain, beyond some production delays, was estimated in July 2019 to be between $500 million and $600 million."139 The Government Accountability Office found that, "[a]s of December 2019, the program has identified new suppliers for all of these parts, but it still needs to bring roughly 15 parts currently produced in Turkey up to the current production rate…. According to an official with the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, by accepting parts from Turkish suppliers through lot 14, the program will have additional time to ensure new suppliers can meet demands for parts."140 |

Two additional countries—Israel and Singapore—are security cooperation participants outside the F-35 cooperative development partnership.141 Israel has agreed to purchase 33 F-35s, and may want as many as 50.142 Japan chose the F-35 as its next fighter in October 2011,143 and South Korea committed to the F-35 in 2014.144 Sales to additional countries are possible. Some officials have speculated that foreign sales of F-35s might eventually surpass 2,000 or even 3,000 aircraft.145

Sales to Israel, Japan, and South Korea are conducted through the standard Foreign Military Sales process, including congressional notification. F-35 sales to nations in the consortium, conducted under 22 U.S.C. 2767, are not reviewed by Congress.146

The UK is the most significant international partner in terms of financial commitment, and the only Level 1 partner.147 On December 20, 1995, the U.S. and UK governments signed an MOU on British participation in the JSF program as a collaborative partner in the definition of requirements and aircraft design. This MOU committed the British government to contribute $200 million toward the cost of the 1997-2001 Concept Demonstration Phase.148 On January 17, 2001, the U.S. and UK governments signed an MOU finalizing the UK's participation in the SDD phase, with the UK committing to spending $2 billion, equating to about 8% of the estimated cost of SDD. A number of UK firms, such as BAE and Rolls-Royce, participate in the F-35 program.149

International Sales Quantities

The cost of F-35s for U.S. customers depends in part on the total quantity of F-35s produced. As the program has proceeded, some new customers have emerged, such as South Korea and Japan, mentioned above. Other countries have considered increasing their buys, while some have deferred previous plans to buy F-35s. It is perhaps noteworthy that the latest Selected Acquisition Reports increased the number of assumed international sales for cost purposes from 612 to 741.150 Recent updates to other countries' purchase plans are detailed in "Changes in International Orders," above.

Other international competitions in which the F-35 is or could be a candidate include the following:

|

Nation |

Plans |

Candidates |

|

Finland |

Studying options to replace early model F/A-18 Hornets. Type selection could be made in 2020, and officials have said only Western fighters are being considered. |

Gripen believed to have an edge. |

|

Spain |

Operating Eurofighter and F/A-18 Hornet for the foreseeable future. Spain wants to replace its Hornets with an unmanned combat aircraft in the late 2020s or 2030s. |

May also have to consider F-35B to maintain a fixed-wing fast jet from its small carrier. |

|

Switzerland |

Looking to replace F-18s with 30 or 40 new fighters. |

Eurofighter Typhoon, Boeing F-18, Dassault Rafale, F-35A and Saab Gripen E |

Source: Tony Osborne, "Fighter Aircraft Procurement Plans Of 19 European Countries," Aviation Week, June 29, 2016, http://aviationweek.com/defense/fighter-aircraft-procurement-plans-19-european-countries-0, and Sebastian Sprenger, "The F-35 and other warplanes descend on Switzerland this spring," Defense News, April 11, 2019, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2019/04/11/the-f-35-and-other-warplanes-descend-on-switzerland-this-spring/. Edited and supplemented by CRS.

As noted, a significant question remains over whether Canada will continue as an F-35 partner. The Trudeau government repudiated the previously announced purchase of 65 (which had originally been 80). Subsequent plans to acquire F-18s instead have been put on hold. Lockheed Martin has stated that if Canada withdraws as a customer, Canadian work share will suffer.151

Work Shares and Technology Transfer

DOD and foreign partners in the JSF program have occasionally disagreed over the issues of work shares and proprietary technology. For example, the United States rejected a South Korean request for transfer of four F-35 technologies that could assist in the development of a Korean indigenous fighter program (although 21 other technologies were approved).152

The governments of Italy and the United Kingdom have lobbied for F-35 assembly facilities to be established in their countries. In July 2010, Lockheed and the Italian firm Alenia Aeronautica reached an agreement to establish an F-35 final assembly and checkout facility at Cameri Air Base, Italy, to deliver aircraft for Italy and the Netherlands. The facility opened in July 2013.153 A similar facility has opened in Nagoya, Japan, with the first aircraft delivered in 2017.154 Norway and the Netherlands will host engine overhaul and logistics facilities Turkey had been scheduled to until its exclusion from the program.

Proposed FY2021 Budget

Table 6 shows the Administration's FY2021 request for Air Force and Navy research and development and procurement funding for the F-35 program, along with FY2019 and FY2020 funding levels. Table 7 shows the procurement request in greater detail.

|

FY2019 |

FY2020 |

FY2021 (request) |

||||

|

Funding |

Quantity |

Funding |

Quantity |

Funding |

Quantity |

|

|

RDT&E funding |

||||||

|

Dept. of Navy |

566.0 |

— |

749.0 |

— |

794.0 |

|

|

Air Force |

558.0 |

— |

750.0 |

— |

923.0 |

|

|

Subtotal |

1,124.0 |

— |

1,499.0 |

— |

1,717.0 |

|

|

Procurement funding |

||||||

|

Dept. of Navy |

5,048.0 |

37 |

4,642.0 |

36 |

3,924.6 |

31 |

|

Air Force |

5,267.0 |

56 |

6,060.0 |

62 |

5,177.8 |

48 |

|

Subtotal |

10,315.0 |

93 |

10,702.0 |

98 |

9,102.4 |

79 |

|

Mods |

304.0 |

411.0 |

632.0 |

|||

|

TOTAL |

11,743.0 |

93 |

12,612.0 |

98 |

11,400.4 |

79 |

Source: Program Acquisition Costs by Weapons System, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer, February 2020.

Note: Figures shown do not include funding for MilCon funding or research and development funding provided by other countries.

|

F-35A |

F-35B |

F-35C |

|||||||

|

Quantity |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Procurement cost |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Less previous advance procurement |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Subtotal |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Advance procurement for future aircraft |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Spares |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Total FY21 request |

|

|

|

||||||

|

Average procurement cost per aircraft |

|

|

|

Issues for Congress

Overall Need for F-35

The F-35's cutting-edge capabilities are accompanied by significant costs. Some analysts have suggested that upgrading existing aircraft might offer sufficient capability at a lower cost, and that such an approach makes more sense in a budget-constrained environment. Others have produced or endorsed studies proposing a mix of F-35s and upgraded older platforms; yet others have called for terminating the F-35 program entirely. Congress has considered the requirement for F-35s on many occasions and has held hearings, revised funding, and added oversight language to defense bills. As the arguments for and against the F-35 change, the program matures, and/or the budgetary situation changes, Congress may wish to consider the value of possible alternatives, keeping in mind the program progress thus far, funds expended, evolving world air environment, and the value of potential capabilities unique to the F-35.

Planned Total Procurement Quantities

A potential issue for Congress concerns the total number of F-35s to be procured. As mentioned above, planned production totals for the various versions of the F-35 were left unchanged by a number of reviews. Since then, considerable new information has appeared regarding cost growth and budget constraints that may challenge the ability to maintain the expected procurement quantities. "'I think we are to the point in our budgetary situation where, if there is unanticipated cost growth, we will have to accommodate it by reducing the buy,' said Undersecretary of Defense Robert Hale, then Pentagon comptroller."155

Some observers, noting potential limits on future U.S. defense budgets, potential changes in adversary capabilities, and competing defense-spending priorities, have suggested reducing planned total procurement quantities for the F-35. A September 2009 report on future Air Force strategy, force structure, and procurement by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, for example, states that

[A]t some point over the next two decades, short-range, non-stealthy strike aircraft will likely have lost any meaningful deterrent and operational value as anti-access/area denial systems proliferate. They will also face major limitations in both irregular warfare and operations against nuclear-armed regional adversaries due to the increasing threat to forward air bases and the proliferation of modern air defenses. At the same time, such systems will remain over-designed – and far too expensive to operate – for low-end threats....

Reducing the Air Force plan to buy 1,763 F-35As through 2034 by just over half, to 858 F-35As, and increasing the [annual F-35A] procurement rate to end [F-35A procurement] in 2020 would be a prudent alternative. This would provide 540 combat-coded F-35As on the ramp, or thirty squadrons of F-35s[,] by 2021[, which would be] in time to allow the Air Force budget to absorb other program ramp ups[,] like NGB [the next-generation bomber, B-21].156

Block 4/C2D2 as a Separate Program

Development of the F-35 Block 4 software, part of an effort now called Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2), is expected to cost as much as $10.8 billion over the next six years.157 "The F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) plans to transition into the next phase of development – Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) – beginning in CY18, to address deficiencies identified in Block 3F development and to incrementally provide planned Block 4 capabilities."158

"The JPO's latest plan for F-35 follow-on modernization ... C2D2, relies heavily on agile software development—smaller, incremental updates to the F-35's software and hardware instead of one big drop, with the goal of speeding follow-on upgrades while still fixing remaining deficiencies in the Block 3F software load."159

Some in Congress argue that a program of that size should part with traditional procurement practice for an upgrade and be run as a separate Major Defense Acquisition Program (MDAP), with its own budget line and the concomitant requirements. At a March 23, 2016, hearing of a House Armed Services subcommittee

Government Accountability Office (GAO) Director of Acquisition and Sourcing Management Michael Sullivan argued that the Block 4 estimated cost justifies its management as a separate program, but F-35 Program Executive Officer (PEO) Air Force Lt. Gen. Christopher Bogdan countered that breaking it off would create an administrative burden and add to the program's price tag and schedule.160

The House-passed version of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2500) contained a provision (§132) that would require the Secretary of Defense to designate the C2D2 program as a major subprogram of the F-35 program. An enacted into law, the act (P.L. 116-92) does not designate Block 4 and/or C2D2 as a major subprogram, but requires the Secretary of Defense to submit an annual integrated master schedule and past performance assessment for each planned phase of Block 4 and C2D2 upgrades.

An emerging issue is the continued oversight of Block 4. As GAO noted in May 2020, delays in the program mean that the Block 4 effort is now likely to last longer than its congressional reporting requirement. 161 The National Defense Authorization Act of 2017 (P.L. 114-328) included language requiring annual reports on the progress of Block 4 through 2023. As the program is now projected to continue through 2026, Congress may wish to consider extending that requirement or other oversight measures.

Competition

Lieutenant General Bogdan's comments regarding the difficulty of cost control in a sole-source environment (see "Engine Costs," above) reflect a broader issue affecting defense programs as industry consolidates and fewer sources of supply are available for advanced systems. Congress may wish to consider the merits of maintaining competition when overseeing system procurements (for example, the use of competition to maintain cost pressure was a principal argument in favor of the F-35 alternate engine program).162 On the F-35 program, that competition could include contracting for lifecycle support as a way to address sustainment costs.

Appropriate Fighter Mix

A significant issue, beginning with the FY2020 DOD budget submission, is the optimal mix of fighter aircraft in the Air Force fleet. Previous plans had focused on the F-35 as the mainstay of the future fighter fleet, in keeping with an Air Force initiative to move to an all-fifth-generation-and-beyond force. In FY2020, however, the Air Force requested an initial 8 of a projected buy of 144 F-15EX fighters. The F-15EX is an improved version of the F-15 Eagle and Strike Eagle fighter series, which the U.S. last acquired in 2001.163

Subsequently, the Air Force justified the request on two grounds: that the operating costs of the F-35 were significantly higher than fourth-generation aircraft like the F-15EX, and that the service needed to acquire 72 new fighters per year to maintain its fleets as older aircraft retire.164

The Air Force has maintained that F-35 and F-15EX do not compete directly for funding. Observers note that, regardless, the F-15EX proposal came at a time when the Air Force reduced its planned F-35 buy from 60 to 48 jets per year. Further, some argue that the additional capabilities inherent in the F-35 provide a better value at similar cost.165 F-15 advocates note the age of current U.S. F-15s, and that new F-15EXs offer better value than extending the lives of existing ones.166

More recently, the Air Force has been considering replacing some F-16s, which had been expected to be replaced by F-35s, with unmanned systems instead.

[Air Combat Command commander Gen. Mike] Holmes suggested that low-cost and attritable unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) might be considered… as a replacement for F-16 Block 25/30 jets… within 5-8 years. In congressional testimony on March 12, Holmes added that ACC's goal is to achieve a fighter fleet ratio of 60% fifth-generation jets, such as F-35As and F-22s, to 40% fourth-generation aircraft, including F-15s, F-16s and A-10s. 167

That ratio had previously been expressed as 50-50.168

Engine Cost Transparency