Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a complex and devastating shock to the global economy.1 The virus has spread to around the world and combatting the pandemic has shut down large portions of the economy. The pandemic has roiled stock markets, upended oil and other commodity markets, created mass unemployment, disrupted trade, resulted in shortages of food and medical supplies, and threatened the solvency of businesses and governments around the world. The World Food Program warns that the number of people suffering acute hunger could almost double by the end of the year without swift international action.2 In April 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) cautioned that COVID-19 will likely be the worst recession since the Great Depression, far worse than the recession following the global financial crisis of 2008-2009.3

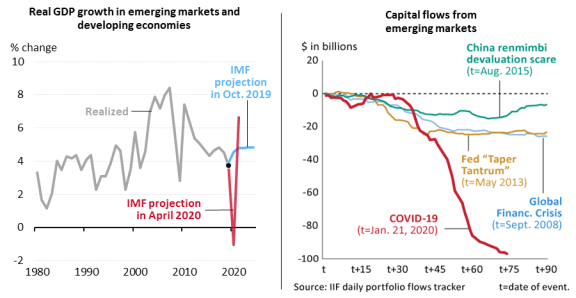

Governments have undertaken extraordinary fiscal and monetary measures to combat the crisis. However, low- and middle-income countries that are constrained by limited financial resources and weak health systems are particularly vulnerable. In April 2020, the IMF forecast that developing and emerging-market countries could contract by at least 1% in 2020; six months earlier the projection was 4.5% growth (Figure 1). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered capital flight from emerging markets on an unprecedented scale, exacerbating the fiscal challenges facing these governments (Figure 1).

Many developing countries are turning to the international financial institutions (IFIs), including the IMF, the World Bank, and the regional multilateral development banks (MDBs), for financial support, and the IFIs are working quickly to mobilize their existing financial resources. The IMF has pledged to use its current $1 trillion lending capacity if necessary, and the MDBs have pledged to mobilize $240 billion over the next 15 months.4

In March 2020, Congress accelerated authorizations under consideration in the FY2021 budget request to increase funding to the IMF, two World Bank lending facilities, and two African Development Bank lending facilities (P.L. 116-136). Multilateral discussions are underway to increase further the IFI's ability to support countries responding to the pandemic. Further congressional action would be required to implement some of the proposals under consideration.

The IMF and the World Bank have called for a debt standstill for low-income countries, during which those countries could suspend debt service payments and instead devote their funds to the exigencies of the pandemic.5 On April 15, 2020, the G-20 donor countries in conjunction with the private sector agreed to a debt standstill through the end of 2020.6 Some policy experts and policymakers in developing countries are calling for additional debt relief given the severity of the crisis for low-income countries. No legislation is required to implement the April 15 agreement, but congressional action would be required for any permanent U.S. debt relief or contributions to finance debt relief provided by the World Bank or other MDBs.

Mobilization of IFI Resources

International Monetary Fund7

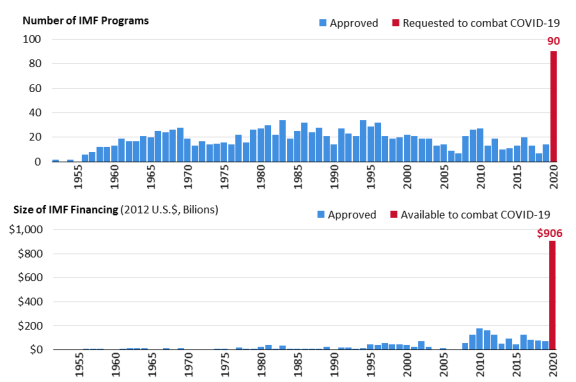

Created in the aftermath of World War II, the IMF's fundamental mission is to promote international monetary stability. To advance this goal, one of the key functions of the IMF is providing emergency loans to countries facing economic crises. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an unprecedented demand for IMF financial assistance. Previously, the highest number of IMF programs approved in a single year was 34 (in 1994), and on average the IMF has approved 18 programs a year (Figure 2).8 Today, more than 100 of the IMF's 189 member countries have requested IMF programs.9 IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has stated that the IMF stands ready to deploy the entirety of its current lending capacity—approximately $1 trillion—in response to the pandemic and resulting economic crises.10 Edwin Truman at the Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates the IMF's maximum lending capacity is currently around $787 billion, and that more IMF resources will be needed.11 The levels of IMF financial assistance under discussion would be unprecedented; previously, the highest cumulative IMF program funding approved in a single year was about $165 billion (in nominal terms), extended in 2010 during the height of the Eurozone crisis (Figure 2).12

The IMF has several financing options for deploying resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The IMF can provide rapid one-off assistance to countries responding to a health disaster, grant debt relief for the poorest and most vulnerable countries to help address public health disasters, increase the size of current IMF loans, and approve new IMF loans.13 The IMF has also been working to increase its flexibility in responding to the crisis. For example, the IMF Executive Board has adopted proposals to accelerate Board consideration of member financing requests for emergency financing and doubled (to about $100 billion) access to IMF emergency assistance.

Most IMF loans are generally conditioned on economic reforms, including austerity measures (government spending cuts and tax increases) and structural reforms (measures that increase the competitiveness of the economy). Some policy experts have raised questions about whether conditionality should be applied to governments seeking assistance for addressing economic crises caused not by irresponsible economic policies but from exogenous shocks prompted by the pandemic.14 Further, some argue that structural reforms may provide benefits in the longer-term, and austerity measures may exacerbate economic crises in the short-term. Additionally, negotiations over conditionality and good governance safeguards take time, raising questions about how quickly IMF funds can and should be disbursed to affected countries.

The IMF has already approved several COVID-related programs, including for Bolivia, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kyrgyz Republic, Nigeria, Niger, Rwanda, Madagascar, Mozambique, Pakistan, and Togo, among others.15 Usually, governments do not disclose their requests for an IMF program until the deal is finalized, due to concerns about further undermining investor confidence. Iran and Venezuela, whose access to capital markets is already restricted by U.S. sanctions, have publicized their requests, which are controversial for U.S. policymakers (see text box). Sudan, whose transitional government is seeking improved relations with the international community, is also seeking emergency support from the IFIs, as the pandemic threatens to exacerbate a pre-existing economic and humanitarian crisis. The country is not able to access most IFI financing mechanisms because of large arrears to the institutions, however. While many in Congress and the Administration have expressed support for Sudan's new government, U.S. Executive Directors at the IFIs would be required to vote against new financing as a result of Sudan's designation under the former regime as a State Sponsor of Terrorism (SST).16

|

Iran's and Venezuela's Requests for IMF Financing17 Iran and Venezuela have requested $5 billion each in loans from the IMF to support their response to COVID-19. These requests are highly unusual: it would be Iran's first IMF program in nearly 60 years, and successive Venezuelan governments for more than a decade have actively blocked the IMF from engaging in routine economic surveillance of the country, as is required of all IMF members. From the U.S. perspective, the requests are controversial. The Trump Administration has taken several significant steps in its campaign of applying "maximum pressure" on Iran, and the U.S. government (as well as most other countries in the world) does not recognize Nicolás Maduro as the legitimate leader of Venezuela.18 The United States imposes significant sanctions on both Iran and Venezuela. Some question whether exemptions to U.S. sanctions on Iran and Venezuela for humanitarian assistance should be extended for COVID-19 assistance from the IMF. The Trump Administration is opposing Iran's IMF program request, maintaining that Iran still has access to sufficient funds to respond to the crisis from its National Development Fund, a sovereign-wealth fund drawn from oil and gas revenues, as well as funds controlled by Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.19 Iran's designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism requires U.S. executive directors at the IFIs to vote against lending to the country. Under the IMF's voting rules, the U.S. voting power is not sufficient to unilaterally veto specific IMF program requests, even though the United States has the largest voting share at the IMF and can veto major policy decisions at the IMF. In Venezuela's case, the IMF declined the country's request for financial assistance, due to disagreement among the IMF membership about Nicolás Maduro's legitimacy.20 The European Union (EU) subsequently expressed support Iran's and Venezuela's requests, including for humanitarian concerns.21 |

Additionally, in April 2020, the IMF Executive Board approved debt service relief to 25 of the IMF's low-income member countries, and later expanded this debt service relief to reach 29 countries.22 The IMF was able to tap its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), revamped to address the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide these countries with grants to cover their debt payments to the IMF for six months. The CCRT can currently provide $500 million in grants to low-income countries and is funded by donor countries, including the UK, Japan, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore, and China. The IMF is seeking to increase this fund by $1.4 billion to provide additional debt service relief. The IMF is also looking to triple the size of its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust Fund (PRGT) to $17 billion. It has $11.7 billion in commitments from Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia.

Also in April 2020, the IMF Executive Board approved the creation of a new Short-term Liquidity Line.23 It is a revolving and renewable backstop for member countries with very strong economic policies in need of short-term and moderate financial support, and intends to support a country's liquidity buffers. Some policy experts have questioned its utility, arguing its scope may be too small, it continues to carry the stigma of borrowing from the IMF, and it is unlikely to be processed fast enough be effective.24

World Bank25

The World Bank, which finances economic development projects in middle- and low-income countries, among other activities, is mobilizing its resources to support developing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic.26 At the end of April 2020, the World Bank had approved, or was in the process of approving, 94 COVID-19 projects, totaling $9 billion, in 78 countries.27 Examples of approved projects include $47 million for the Democratic Republic of Congo to support containment strategies, train medical staff, and provide equipment for diagnostic testing to ensure rapid case detection; $11.3 million for Tajikistan to expand intensive care capacity; $20 million for Haiti to support diagnostic testing, rapid response teams, and outbreak containment; and $1 billion for India to support screening, contract tracing, and laboratory diagnostics, procure personal protective equipment, and set up new isolation wards, among other projects.28

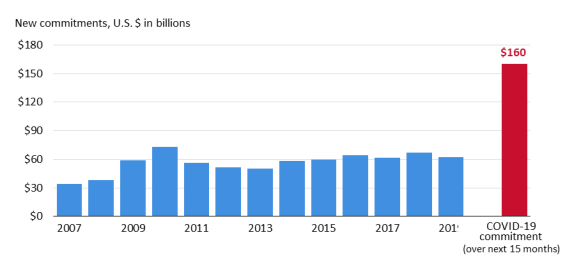

Over the next 15 months, the World Bank Group estimates it could deploy as much as $160 billion to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, more than double the amount it committed in FY2019 (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. World Bank Group COVID-19 Funding Commitment: Historical Perspective |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using World Bank Annual Reports. Notes: Fiscal year data. |

From official World Bank statements, it is unclear whether the $160 billion commitment is additional financing, an acceleration of its normal lending, or a combination.29 It is also unclear to what extent the funds will be concessional financing (grants and low-cost loans) for the world's poorest countries or nonconcessional financing (market-rate loans) for middle income countries. According to the World Bank, the $160 billion commitment is to include:

- $50 billion in net transfers to low-income countries—those that are eligible for the World Bank's International Development Association (IDA) concessional lending and grant facility;

- $8 billion in financial support provided through the World Bank's private-sector lending facility, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), for private companies and their employees hurt by the economic downturn caused by the spread of COVID-19; and

- a new $6.5 billion facility to support private sector investors and lenders in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, administered by the World Bank's Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA).30

On April 17, 2020, the World Bank announced its plans to establish a new multi-donor trust fund to help countries prepare for disease outbreaks, the Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Multi-Donor Fund (HEPRF).31 The new fund is to complement, and augment, the $160 billion of financing provided by the World Bank. Japan was the first country to pledge to be a founding donor to the new trust fund, which will aim to spur critical health security investments in the context of the current pandemic as well as in the future. For example, the fund is to provide incentives to IDA-eligible countries to increase investments in health emergency preparedness and enable low-income countries to quickly and effectively respond to major disease outbreaks at an early stage.

|

World Bank Pandemic Bonds32 Developing countries had difficulty mobilizing resources to respond to the Ebola outbreak that started in 2014. In order to provide financial assistance to developing countries early in an outbreak and prevent a pandemic from taking hold, the World Bank in 2017 created "pandemic bonds." Investors could buy the bonds and receive interest payments, with the risk that some or all of the principal could be used to help developing countries in the event of a serious outbreak of infectious disease. The World Bank sold two classes of pandemic bonds totaling $320 million, with interest payments to investors funded by donor nations Japan, Australia, and Germany. The bonds have several criteria that would trigger payment to affected developing countries; these include outbreak size, growth rate, and spread across borders. The bonds, set to mature in July 2020, were triggered on April 17, 2020. According to a Bank statement, the bonds will provide $195.84 million to the Bank's Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEFF), the fund housed at the World Bank associated with the pandemic bonds. Policy experts have criticized the terms of the World Bank's pandemic bonds, arguing that the triggers are too late to stop an outbreak early and are too dependent on the ability of developing countries to test and report cases. Additionally, investors were attracted to pandemic bonds because they believed the returns on the pandemic bonds would be uncorrelated with the returns in major capital markets. The COVID-19 pandemic has undermined that assumption, with the pandemic causing significant losses in capital markets. The World Bank planned to issue additional bonds when the current issue matures in July 2020, and some policy experts are calling for significant reforms if new pandemic bonds are issued as originally planned in July 2020. Some are calling for a stop to the program altogether. |

Specialized Multilateral Development Banks

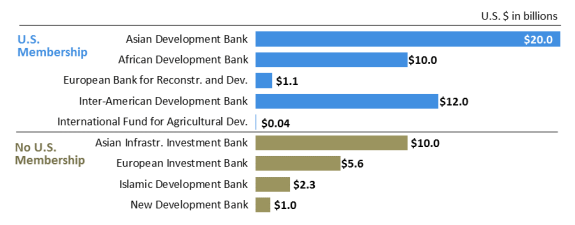

In addition to the World Bank, which has a near-global membership and operates in many sectors in developing countries worldwide, a number of smaller and more specialized MDBs are also mobilizing resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The United States helped create and belongs to four MDBs focused on promoting economic development in specific regions: the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Together with the World Bank, these organizations are the five major MDBs.

There are also smaller MDBs, however. The United States also belongs to the International Fund for Agricultural Development, which works to address poverty and hunger in rural areas of developing countries, but it does not belong to two MDBs recently created and led by emerging markets. These include the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, spearheaded by China, and the New Development Bank created by the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa).33 Nor does the United States belong to the European Investment Bank, the lending arm of the European Union, or the Islamic Development Bank, led by Saudi Arabia and created in the 1970s.

Specialized MDBs are launching a robust response to the crisis, including reprogramming existing projects, establishing and funding with existing resources lending facilities dedicated to the COVID-19 response, and streamlining approval procedures. According to the President of the World Bank, other multilateral development banks have committed roughly $80 billion over the next 15 months to respond to COVID-19.34 It is not entirely clear which other MDBs are included in this total, or the amounts committed by each MDB. Estimates based on MDB press releases are provided in Figure 4. Together with the World Bank's commitment of $160 billion, $240 billion in financing is to be made available to developing countries from the MDBs during this time period.35 Details of on specific MDB responses measures are provided in the Appendix (Table A-1).

|

Figure 4. Estimates of Specialized MDB COVID-Related Commitments |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS based on MDB websites and press releases. |

Debt Service Relief for Low-income Countries

The path to the suspension of debt payments for IDA countries took some time to gain momentum. Most donors prefer to coordinate debt relief efforts so the resources made available from debt relief can be used to benefit the developing country rather than be used to repay other creditors. Debt relief by donor governments has traditionally been organized by the Paris Club, an informal group of creditor countries, including the United States, whose origins can be traced back to the 1950s.36 The Paris Club does not include China, which has in recent years emerged as a major creditor to developing countries and whose lending terms are opaque.37 China has resisted international efforts to increase debt transparency through the IMF and the World Bank, and has been reluctant to set a precedent for widespread debt forgiveness.38 At their first emergency teleconference summit on March 26, the G-20 leaders stopped short of providing the requested debt relief, but pledged to "continue to address risks of debt vulnerabilities in low-income countries due to the pandemic."39

Negotiations continued and on April 15, 2020, the G-20 finance ministers announced the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), a temporary suspension of debt payments until the end of the year for the world's poorest countries (those eligible for IDA assistance).40 The Institute of International Finance (IIF), a group that represents about 450 banks, hedge funds, and other global financial funds, concurrently announced that private creditors will join the debt relief effort on a voluntary basis. This debt standstill potentially frees up more than $20 billion for these countries to spend on improving their health systems and fighting the pandemic, including $12 billion in payments to official creditors (governments) and $8 billion in payments to private creditors.41 The standstill is to run from May 1, 2020 through December 31, 2020. Repayment schedules are to be net present value neutral, meaning that no debt is actually written off, but rather rescheduled to be paid later.

The G-20 decided that the DSSI would apply to the 76 countries designated by the World Bank as eligible for IDA assistance, as well as Angola, which is not eligible for IDA assistance but is designated by the United Nations as one of the world's least developed countries (LDC). According to estimates by IIF, total external debt in DSSI countries exceeds $750 billion.42 This number may actually be much higher, however, since China and many other creditors do not publicly disclose the scale and scope of their external lending.

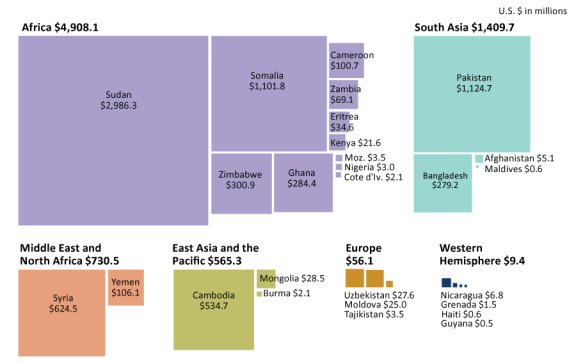

Debt owed to the United States by DSSI countries is approximately $7.7 billion (Figure 5).43 Since the current proposal only provides debt rescheduling and not debt cancellation, it does not require U.S. legislation. Some advocates, however, are calling for debt forgiveness, which has been provided in the past. In this case, authorizations and appropriations would be necessary. The procedure for budgeting and accounting for any U.S. debt relief is based on the method used to value U.S. loans and guarantees provided in the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990.44 Since passage of the act, U.S. government agencies are required to value U.S. loans, such as bilateral debt owed to the United States, on a net present value basis rather than at their face value, and an appropriation by Congress of the estimated amount of debt relief is required in advance of any debt relief taking place. Prior to the passage of the act, neither budget authority nor appropriations were required for official debt relief. Bilateral debt (and other federal commitments) were accounted for on a cash-flow basis, which credits income as it is received and expenses as they are paid.45

|

Figure 5. Bilateral Debt owed to the United States by Low-Income Countries December 2019 |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using the Department of the Treasury's Foreign Credit Report System, available at https://fcrs.treas.gov/FCRS_PublicSite/. Notes: Somalia reached the HIPC (Heavily Indebted Poor Countries) decision point in March 2020 and Congress has authorized an initial allocation to write off Somalia's debt, with the remainder requested in the FY2021 budget request. |

Proposals for Additional Actions

For FY2021, the Administration had requested authorizations to increase funding for several IFIs. In March 2020, Congress enacted these authorizations in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act, P.L. 116-136). The authorizations include:

- $38 billion for a supplemental fund at the IMF (the New Arrangements to Borrow, or NAB);

- $3 billion for the nineteenth replenishment of World Bank's IDA resources;

- $7.3 billion for the seventh capital increase at the African Development Bank; and

- $513.9 million for the fifteenth replenishment of resources at the African Development Bank's concessional lending facility, the African Development Fund.

Given the size and scope of the financing needs faced by developing and emerging economies, policy experts and policymakers considering several unusual policy options to further bolster the IFI response. These options, including stretching MDB lending using current resources, IMF gold sales, IMF policies to bolster global liquidity, and further multilateral debt relief, are discussed in greater detail below, as well as any legislation that would be required for U.S. participation in such efforts.

Stretch MDB Lending using Existing Resources

Some analysts argue that the MDBs have the financial capacity to lend substantially larger amounts than they have already committed.46 Traditionally, the MDBs have been exceedingly conservative in their approach to capital adequacy. Christopher Humphrey of the London-based Overseas Development Institute (ODI) points out that the five main MDBs (AfDB, ADB, IDB, EBRD, and IBRD [World Bank]) carry an equity-to-loan ratio of between 20% and 60%, compared to 10 to 15% for commercial banks.47 According to these calculations, the major MDBs can expand lending by at least $750 billion (160% above current levels), while maintaining an AAA rating, or as much as $1.3 trillion (nearly triple current levels) if they are willing to risk a rating downgrade to AA+.48

A key reason for these potentially higher lending levels, is that when MDBs calculate their capital adequacy, they do not include "callable capital" that member countries have committed to the institutions. The capital that the United States and other shareholders contribute to the MDBs usually comes in two forms: (1) "paid-in capital," which requires the transfer of funds to the MDBs; and (2) "callable capital," which are funds that shareholders agree to provide, but only when necessary to avoid a default on a borrowing by the MDB itself. (A member country defaulting on a World Bank loan would not cause the Bank to draw on its callable capital.) No MDB has ever had to draw on its callable capital.

When MDBs calculate their capital adequacy, they include only paid-in capital and accumulated reserves. By contrast, the major rating agencies include callable capital when calculating potential MDB lending headroom and have noted that the MDBs could lend higher amounts without threatening their rating.49 According to Humphrey, "[callable] capital is considered financially sound by the ratings agencies, but is effectively ignored by the MDBs."50 While the U.S. government provides oversight of MDB operational decisions, no congressional legislation would be needed for the MDBs to change their capital adequacy rules.

IMF Gold Sales

Advocates have also proposed that the IMF sell a portion of its gold reserves to finance debt relief for the poorest countries. According to Oxfam's Nadia Daar, "With gold prices hitting a seven-year high, the IMF should use the windfall profits from gold sales for debt cancellation to avert catastrophic loss of life in developing countries."51

The IMF holds 90.5 million ounces of gold in reserves, valued at around $153 billion at current market prices.52 The IMF's total gold holdings are valued on its balance sheet at about $4.9 billion (SDR 3.2 billion) on the basis of historical cost.53 The IMF acquired virtually all of this gold through four types of transactions.54 In 1978, IMF members adopted an amendment to the Articles of Agreement allowing each country to determine its own exchange rate system. The amendment officially severed the link between currency and gold. IMF member countries were prohibited from defining the value of their currency in terms of gold and the IMF was prohibited from lending gold or defining its assets in terms of gold. Countries could use any exchange rate system (other than using gold as a base) for defining the value of their currencies. Since the 1978 amendment, the use of gold in the IMF's operations has been severely limited.

In recent decades, IMF members have supported the limited sale of IMF gold holdings. As with other major IMF policy decisions, gold sales require an 85% majority vote of the total voting power. U.S. voting power at the IMF is 16.51% and thus U.S. support is required for IMF gold sales. In 2000, IMF gold sales were used to fund debt relief for several of the poorest developing countries. In September 2009, the IMF's Executive Board approved the total sale of 403.3 metric tons of gold as a key step in strengthening the IMF's finances.55 A portion of the profits from gold sales in 2009 and 2010 were used to support concessional lending to low-income countries.

Under U.S. law, congressional authorization is required for the United States to support IMF gold sales. In 1999, Congress enacted legislation in the FY2000 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 106-113) that authorized the United States to vote at the IMF in favor of a limited sale of IMF gold to fund the IMF's participation in poor country debt cancellation. The legislation required the explicit consent of Congress before the executive branch could support any future gold sales.56 All subsequent gold sales have been explicitly authorized by Congress.

IMF Policies to Augment Foreign Reserves

As part of the U.S. response to COVID-19, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) has taken steps to ensure that major central banks have uninterrupted access to U.S. dollars. First, the Fed established emergency swap lines, or temporary reciprocal currency arrangements, with major central banks and lowered the interest rate it charges on the swap lines. Swap lines allow foreign central banks to temporarily exchange their currency for dollars with the Fed. Second, the Fed created a foreign central bank (FIMA) repurchase (repo) facility. The facility, which also charges interest, allows a broader range of emerging market central banks to temporarily exchange their U.S. Treasury securities for U.S. dollars.

While these Fed efforts have been critical, access to their facilities has been relatively limited to advanced economies and some emerging market countries. Less-developed economies and most low-income countries are unable to access Fed facilities, and their limited foreign exchange reserves are rapidly depleting. One option widely discussed is providing a global allocation of IMF special drawing rights (SDRs).57 The First Amendment to the IMF Articles of Agreement, which went into effect in 1969, authorized the IMF to create a new international reserve asset that could be used to supplement its member country's foreign exchange reserves.

This asset, known as SDRs, is neither a currency nor a claim on the IMF. Rather, it is a potential claim on the freely usable currencies of IMF members. SDRs may be exchanged for hard convertible currency among IMF member nations. IMF rules govern how a country may exercise its claim and convert its share of SDRs into another country's hard currency.58 SDRs are created by fiat, and are not "paid for" by any foreign contributions or backed by any national currency. IMF member countries are allocated a number of SDRs based on their IMF quota.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, some policy advocates have proposed an SDR increase of at least $500 billion to provide additional resources to the least developed countries to help them cope with sharp capital outflows and current low commodity prices.59 For example, on April 21, 2020, Representative Jesus Garcia along with several colleagues introduced the Robust International Response to Pandemic Act (H.R. 6581) that would, among other things, instruct the U.S. Treasury to support an allocation of $3 trillion SDRs.

Support for a new SDR creation is not universal.60 The foremost policy concern with a new SDR increase is their relative inefficiency. Since SDRs are allocated based on IMF quota holdings, the majority of them would be allocated to advanced economies, which are unlikely to ever use their SDRs. These countries could buy and sell SDRs among themselves in order to get useable foreign exchange, but they can do this already—and much more easily—through central bank swaps and other such mechanisms. An additional concern for many U.S. policymakers is that all IMF members, including countries under U.S. sanctions such as Iran and Venezuela, would be included in a general SDR allocation. Reportedly, opposition to providing SDRs to certain countries was a key factor in the U.S. Treasury opposing a broad SDR allocation when it was discussed during the spring 2020 IMF-World Bank annual meetings, even as the it supported a number of other IMF policy responses.61

U.S. support would be required for an SDR allocation of any size. Article XXVIII of the Fund's Articles of Agreement indicates that the creation and allocation of SDRs requires support from at least 85% of the total voting power of the IMF's membership. Due to the size of U.S. voting power at the IMF (16.41%), the United States has veto power over SDR allocations.

Additionally, if the size of the SDR increase is equal to or larger than the U.S. share of total IMF quota, congressional support is also required. The Special Drawing Rights Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-349) gave the Executive Branch authority to vote for the First Amendment to the IMF's Articles of Agreement creating the SDR, and set forth the guidelines for U.S. participation in the SDR Department. However, the Act also says that if the U.S. share of a new allocation of SDRs is less than the size of the U.S. quota, the United States can support an SDR allocation as long as the Department of the Treasury consults with leaders of the House and Senate authorizing committees at least 90 days in prior to the vote. U.S. quota is currently about $113.3 billion. Since the U.S. share of IMF quota is currently 17.45%, the Administration could support a SDR allocation of less than about $649 billion without legislation as long as the consultation requirements are met.

Additional Debt Relief

As noted above, calls are mounting for the G-20 DSSI to go further. Former Nigerian finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, one of the four special envoys of the African Union soliciting G-20 support for Africa in dealing with COVID-19, is calling for the debt service relief period to be extended to two years.62 The DSSI does not lower the debt for many low-income countries, and many analysts suggest that, during the debt service payment freeze, official and private sector creditors should work with low-income countries to restructure debts.63 The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) is calling for around $1 trillion in debts owed by developing countries to be canceled.64

Debt restructuring, which could entail some combination of lengthening maturities, lowering interest rates, and writing-off principle, would lower the debt burden facing developing countries. However, debt restructurings are complex and can take years to negotiate. Divisions between western creditor governments and China over debt relief further complicate negotiations. Many developing countries, including low-income and middle-income countries, faced with a severe economic contraction and pressing health needs, may be forced into default before restructurings can be completed. Low-income and middle-income countries, faced with a severe economic contraction and pressing health needs, may be forced into default before restructurings could be completed. Many African countries reportedly are already requesting debt relief from China in exchange for collateral, including in some cases strategic state assets.65

Additionally, the DSSI does not address the $12 billion in payments due by low-income countries to multilateral lenders, including the IMF and the World Bank, through the end of the year. The handling of these debts is reportedly still under discussion.66 For much of their history, the IFIs have served as lenders of last resort to countries suffering from financial crisis. Thus, the IFIs argued that since they provided assistance to countries unable to borrow from anyone else, they should receive preferred creditor status. This means that the World Bank and the IMF would be paid first in the event that borrowers ran into financial difficulties, and that debts owed to them would not be reduced under any circumstances. However, there have been some occasions in the recent past when IMF and MDB debts were reduced. In 2005 for the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) led by the G-8, the MDBs received new money from creditor nations to offset their debt reductions while the IMF absorbed the cost of debt relief using internal resources and the proceeds of gold sales. As discussed earlier in this report, if the international community agrees to seek a new multilateral debt relief agreement, congressional action would likely be required.

|

China and the IFIs: Legislation in the 116th Congress Some policymakers have expressed concerns about China's handling of its early COVID-19 outbreak (see, for example, H.Res. 907). This may affect congressional consideration of U.S. policy towards China at the IFIs. China has an unusual dual role at the IFIs. In recent years, China's leadership role at the IFIs has increased through greater financial contributions, voting power, and senior leadership positions. However, China remains a key borrower from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. These financial arrangements can help address development needs in China, earn the IFIs interest with which they can use to pay their staff and provide concessional assistance to the world's poorest countries, and attach procurement, labor, and environmental standards to development projects in China. However, questions have been raised about whether financial support to China is the most beneficial use of IFI resources, given the ample reserves China could tap to fund domestic development projects. China is also funding its own overseas development projects through the new Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and China's Belt and Road Initiative. The U.S. Executive Directors to the IFIs are instructed to oppose nonhumanitarian, nontrade-related IFI projects in China due to concerns about human trafficking.67 The Accountability for World Bank Loans to China Act (H.R. 5051 and S. 3017) would push for China to "graduate" from its eligibility for World Bank assistance and would push for greater debt transparency of China's Belt and Road Initiative. Following reports of a questionable $50 million World Bank loan to a Chinese organization associated with the forcible internment of Chinese Uighur Muslims, four Senators introduced S. 3018, which also push for China's graduation from its eligibility for World Bank assistance.68 |

Policy Questions for Congress

The IFIs are mobilizing resources on an unprecedented scale to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis. To respond to what the IMF is projecting as the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression, multilateral efforts for debt relief are also underway. Some policy experts and policymakers are calling for additional policies to bolster the IFI response, as well as for further multilateral coordination on debt relief for low-income countries.

The role of the IFIs in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic raises a number of potential policy questions for Congress. These include the following.

- Do the IFIs have sufficient resources to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic? Does the United States support mobilization of additional resources, and if so, through what mechanisms?

- Developing countries face a variety of financing needs, including funding the immediate public health response, broad budgetary support, and liquidity support. How should the IFIs prioritize their financial assistance? How should IFI assistance be allocated across countries?

- How might coordination and coherence of COVID-19 responses among IFIs and donor governments be handled?

- Many IFIs are focused on the rapid disbursement of financial assistance. What is the trade-off between streamlining approval processes and maintaining due diligence to protect IFI resources? Is there oversight of how the resources from debt relief are used?

- Do the IFIs have sufficient staffing to process high volumes of financial assistance?

- China has emerged as a major creditor in recent years, but the terms of its lending are opaque. Do the IFIs have sufficient access to the information needed to assess the financing needs of developing countries and emerging markets? Would any IFI assistance be used to pay off China debt in certain countries?

- While the current focus is on getting resources quickly to the poor and least developed countries, the IMF is drawing attention to large project increases in debt/GDP ratios for many countries. What is the Administration's position on a new round of multilateral debt forgiveness? How is the Administration engaging on developing-country debt with official institutions and the private sector?

- What is the Administration's plan for debt relief negotiations with creditor governments outside of the Paris Club group of creditors?

- What is the appropriate balance between IFI financing and debt relief in the COVID-19 response? In what context is one policy more useful? How might the disbursement of IFI financial assistance be impacted by an inability to reach multilateral agreement on debt relief?

- Developing and emerging economies are facing immediate financing needs to grapple with the spread of COVID-19, and economic recovery from the pandemic may take years. How should the IFIs assess the capacity of countries to repay IFI loans given the short-, medium-, and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Appendix.

|

Regional or Specialized Multilateral Development Bank |

COVID-19 Response |

|

Asian Development Bank |

In March 2020, the AsDB announced an initial $6.5 billion package to address the immediate needs of developing member countries as they respond to the Covid-19 pandemic. In April 2020, the AsDB more than tripled its commitment to $20 billion, including $2.5 billion for concessional lending and grants. Up to $13 billion can be used in a new COVID-19 Pandemic Response Option under AsDB's Countercyclical Support Facility. These funds will help finance government expenditures during the economic downturn, with a particular focus on the poor and vulnerable. Additionally, about $2 billion of the $20 billion package will be made available to the private sector, including loans and guarantees to rejuvenate trade and supply chains, enhance microfinance loans, and provide liquidity to small- and medium-sized enterprises. The AsDB has also make a number of policy adjustments to allow to respond more rapidly to the crisis, such as streamlining internal business processes and widening the eligibility and scope of various support facilities. |

|

African Development Bank (AfDB) |

The AfDB announced in April 2020 the creation of a new COVID-19 Response Facility to assist regional member countries in fighting the pandemic. The facility is to provide up to $10 billion in financial support, including $5.5 billion in market-based financial assistance to governments, $3.1 billion in concessional financial assistance to governments, and $1.35 billion in market-based financial assistance to the private sector. |

|

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) |

The EBRD has created a new framework, the Solidarity Package to provide up to €1 billion (about $1.1 billion) to existing EBRD clients facing temporary financing challenges. The framework is to be in place as long as needed. Projects totaling €500 million (about $543 billion) are in the approval process, and the EBRD is preparing to increase the amount of funding available in the program. The EBRD also provided record trade financing in March 2020, and is aiming to develop a streamlined approach to project approvals. |

|

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) |

The IDB is making available up to $12 billion to member countries to respond to the pandemic and its health and economic consequences, including reprogramming its existing portfolio of health projects and directing additional lending to COVID-related projects. Additionally, governments can request the redirection of resources from projects underway to meet needs related to the virus. IDB Invest, the private sector institution of the IDB group, is contributing $5 billion to the IDB's efforts to combat the pandemic in 2020. The IDB is focused on the immediate public health response, safety nets for vulnerable populations, economic productivity and employment (particularly for SMEs), and fiscal support for governments. The IDB is working to increase the availability of funds and streamline its lending process. |

|

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) |

IFAD announced in April 2020 the creation of a new multi-donor fund, the COVID-19 Rural Poor Stimulus Facility, which is to strive to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on food production, market access, and rural employment. IFAD has committed $40 million of its own resources, and is seeking to raise at least $200 million from member states, foundations, and the private sector. |

|

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) |

In early April 2020, the AIIB announced the creation of a new Crisis Recovery Facility to offer an initial $5 billion of financing over 18 months to public and private sector entities facing serious adverse impacts as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Later in April, the AIIB doubled the funding for the new facility to $10 billion. The facility is focused on health infrastructure and pandemic preparedness, liquidity support, and immediate fiscal and budgetary support. |

|

European Investment Bank (EIB) |

The EIB is committing €5.2 billion (about $5.6 billion) in coming months to strengthen urgent health investment and accelerate long-standing support for private sector investment in more than 100 countries around the world. The support is to be fast-tracked and focused on sectors most threatened by the economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The EIB is also creating a €25 billion (about $27 billion) European COVID-19 guarantee fund, enabling the EIB to scale up support for European countries up to an additional €200 billion (about $217 billion).The fund is to focus on small- and medium-sized enterprises. |

|

Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) |

The IsDB Board of Executive Directors approved in April 2020 $2.3 billion for a new IsDB Group Strategic Preparedness and Response Program for COVID-19. The program aims to support member countries' efforts to mitigate and recover from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including short-term health needs and longer-term economic recovery goals. |

|

New Development Bank (NDB) |

The NDB approved a RMB 7 million (about $1 billion) emergency assistance loan to the Chinese government in March 2020. The NDB also issued a yuan-denominated bond in April 2020 to help finance public health expenditures in the areas of China hit hardest by COVID-19. |

Source: CRS analysis of MDB websites and press releases.