Introduction

The Small Business Administration's (SBA's) Women-Owned Small Business (WOSB) Federal Contracting Program is one of several contracting programs Congress has approved to provide greater opportunities for small businesses to win federal contracts. Congress's interest in promoting small business contracting dates back to World War II and the outbreak of fighting in Korea. At that time, Congress found that thousands of small business concerns were being threatened by war-induced shortages of materials coupled with an inability to obtain defense contracts or financial assistance.1 In 1953, concerned that many small businesses might fail without government assistance, Congress passed, and President Dwight Eisenhower signed into law, the Small Business Act (P.L. 83-163). The act authorized the SBA.

The Small Business Act specifies that it is Congress's declared policy to promote the interests of small businesses to "preserve free competitive enterprise."2 Congress indicated that one of the ways to preserve free competitive enterprise was to increase market competition by insuring that small businesses received a "fair proportion" of federal contracts and subcontracts.3

Since 1953, Congress has used its broad authority to impose requirements on the federal procurement process to help small businesses receive a fair proportion of federal contracts and subcontracts, primarily through the establishment of federal procurement goals and various contracting preferences—including restricted competitions (set-asides), sole source awards, and price evaluation adjustment/preference in unrestricted competitions—for small businesses.4 Congress has also authorized the following:

- government-wide and agency-specific goals for the percentage of federal contract and subcontract dollars awarded to small businesses generally and to specific types of small businesses, including at least 5% to WOSBs;5

- an annual Small Business Goaling Report to measure progress in meeting these goals;

- a general requirement for federal agencies to reserve (set aside) contracts that have an anticipated value greater than the micro-purchase threshold (currently $10,000) but not greater than the simplified acquisition threshold (currently $250,000);6 and, under specified conditions, contracts that have an anticipated value greater than the simplified acquisition threshold exclusively for small businesses.7 A set-aside is a commonly used term to refer to a contract competition in which only small businesses, or specific types of small businesses, may compete;

- federal agencies to make sole source awards to small businesses when the award could not otherwise be made (e.g., only a single source is available, under urgent and compelling circumstances);

- federal agencies to set aside contracts for, or grant other contracting preference to, specific types of small businesses (e.g., Minority Small Business and Capital Ownership Development Program (known as the 8(a) program) small businesses, Historically Underutilized Business Zone (HUBZone) small businesses, WOSBs, and service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses (SDVOSBs));8 and

- the SBA and other federal procurement officers to review and restructure proposed procurements to maximize opportunities for small business participation.

Additional requirements are in place to maximize small business participation as prime contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers. For example, prior to issuing a solicitation, federal contracting officers must do the following, among other requirements:

- divide proposed acquisitions of supplies and services (except construction) into reasonably small lots to permit offers on quantities less than the total requirement;

- plan acquisitions such that, if practicable, more than one small business concern may perform the work, if the work exceeds the amount for which a surety may be guaranteed by the SBA against loss under 15 U.S.C. §694b [generally $6.5 million, or $10 million if the contracting officer certifies that the higher amount is necessary];9

- encourage prime contractors to subcontract with small business concerns, primarily through the agency's role in negotiating an acceptable small business subcontracting plan with prime contractors on contracts anticipated to exceed $700,000 or $1.5 million for construction contracts;10 and

- under specified circumstances, provide a copy of the proposed acquisition package to an SBA procurement center representative (PCR) for his or her review, comment, and recommendation at least 30 days prior to the issuance of the solicitation. If the contracting officer rejects the PCR's recommendation, he or she must document the basis for the rejection and notify the PCR, who may appeal the rejection to the chief of the contracting office and, ultimately, to the agency head.11

This report focuses on the SBA's WOSB Federal Contracting Program, authorized by H.R. 5654, the Small Business Reauthorization Act of 2000, and incorporated by reference in P.L. 106-554, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2001.12

The WOSB program is designed to help federal agencies achieve their statutory goal of awarding at least 5% of their federal contracting dollars to WOSBs (established by P.L. 103-355, the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994 (FASA)) by allowing federal contracting officers to

- set aside acquisitions exceeding the micro-purchase threshold (currently $10,000) for bidding by WOSBs (including economically disadvantaged WOSBs (EDWOSBs)) exclusively in industries in which WOSBs are substantially underrepresented, and

- set aside contracts for bidding by EDWOSBs exclusively in industries in which WOSBs are underrepresented.

Congressional interest in the WOSB program has increased in recent years because the federal government has met the 5% procurement goal for WOSBs only once—in FY2015—since the goal was authorized in 1994, and implemented in FY1996 (see Table 1).

The data on WOSB federal contract awards suggest that federal procurement officers are using the WOSB program more often than in the past, but the amount of WOSB awarded contracts account for a relatively small portion of the total amount of contracts awarded to WOSBs. Most of the federal contracts awarded to WOSBs are awarded in full and open competition with other firms or with another small business preference, such as an 8(a) or HUBZone program preference. Relatively few federal contracts are awarded through the WOSB program (see Table 1).

In addition, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the SBA's Office of Inspector General (OIG) have noted deficiencies in the SBA's implementation and oversight of the program. For example, the WOSB program was authorized on December 21, 2000. The SBA took nearly 10 years to issue a final rule for the program (on October 7, 2010) and another four months before the program actually went into effect (on February 4, 2011).13 The SBA attributed the delay primarily to its difficulty in identifying an appropriate methodology to determine "the industries in which WOSBs are underrepresented with respect to federal procurement contracting."14

P.L. 113-291, the Carl Levin and Howard P. "Buck" McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (NDAA 2015), enacted on December 19, 2014, removed the ability of small businesses to self-certify their eligibility for the WOSB program as a means to ensure that the program's contracts are awarded only to intended recipients. Among other provisions, NDAA 2015 also required the SBA to implement its own certification process for WOSBs. The SBA issued an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the Federal Register on December 18, 2015, to solicit public comments on drafting a proposed rule to meet these requirements. The SBA did not issue the proposed rule until May 14, 2019. The SBA requested comments on the proposed rule to be submitted by July 15, 2019. It anticipates implementing the certification program and removing the self-certification option in July 2020, more than five and a half years after these requirements were enacted.15

Table 1. Women-Owned Small Business (WOSB) Contract Awards, Amount and % of Small Business Eligible Contracts, FY1995-FY2018

($ in billions)

|

Fiscal Year |

Amount |

% of Small Business Eligible Contracts |

WOSB and EDWOSBSet-Aside and Sole Source Awards |

WOSB Set-Aside Awards |

WOSB Sole Source Awards |

EDWOSB Set-Aside Awards |

EDWOSB Sole Source Awards |

|

2018 |

$20.618 |

4.27% |

$0.893 |

$0.742 |

$0.093 |

$0.050 |

$0.009 |

|

2017 |

$20.844 |

4.71% |

$0.723 |

$0.583 |

$0.068 |

$0.064 |

$0.009 |

|

2016 |

$19.670 |

4.79% |

$0.449 |

$0.318 |

$0.035 |

$0.085 |

$0.010 |

|

2015 |

$17.807 |

5.05% |

$0.287 |

$0.201 |

— |

$0.086 |

— |

|

2014 |

$17.177 |

4.68% |

$0.177 |

$0.106 |

— |

$0.071 |

— |

|

2013 |

$15.365 |

4.32% |

$0.101 |

$0.040 |

— |

$0.061 |

— |

|

2012 |

$16.180 |

4.00% |

$0.072 |

$0.033 |

— |

$0.039 |

— |

|

2011 |

$16.807 |

3.98% |

$0.021 |

$0.015 |

— |

$0.006 |

— |

|

2010 |

$17.456 |

4.04% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2009 |

$14.419 |

3.21% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2008 |

$14.420 |

3.21% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2007 |

$12.926 |

3.41% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2006 |

$11.616 |

3.41% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2005 |

$10.187 |

3.18% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2004 |

$9.092 |

3.03% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2003 |

$8.300 |

2.98% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2002 |

$6.800 |

2.50% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2001 |

$5.500 |

2.49% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

2000 |

$4.600 |

2.88% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

1999 |

$4.510 |

2.25% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

1998 |

$4.060 |

2.03% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

1997 |

$3.590 |

1.84% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

1996 |

$3.441 |

1.74% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

1995 |

$3.621 |

1.79% |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Sources: White House (Clinton), The State of Small Business: A Report of the President, 1996, (Washington, DC: GPO, 1997), p. 325 [FY1995], at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015087497429; White House (Clinton), The State of Small Business: A Report of the President, 1997 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1998), p. 194 [FY1996], at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x004466169; White House (Clinton), The State of Small Business: A Report of the President, 1998 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1999), p. 250 [FY1997], at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112048180589; White House (G.W. Bush), The State of Small Business: A Report of the President, 1999-2000 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2001), p. 132 [FY1998, FY1999], at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x004572085; U.S. Congress, House Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Contracting and Technology, Subcommittee Hearing on Federal Government Efforts in Contracting with Women-Owned Businesses, hearing, 110th Cong., 1st sess., March 21, 2007, serial no. 110-9 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2007), pp. 4, 46 [FY2000]; U.S. Congress, House Committee on Small Business, Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform and Oversight, SBA's Procurement Assistance Programs, hearing, 109th Cong., 2nd sess., March 30, 2006, serial no. 109-45 (Washington, DC: GPO, 2006), p. 31 [FY2001-FY2004]; U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), "Federal Procurement Data System – Next Generation," Small Business Goaling Report [FY2005-FY2018], at https://www.fpds.gov/fpdsng_cms/index.php/en/reports.html; and GSA, "Federal Procurement Data System – Next Generation," accessed on February 24, 2020 (WOSB and economically disadvantaged WOSB (EDWOSB) set-aside and sole source awards, FY2011-FY2018).

Notes: The small business eligible baseline excludes certain contracts that the U.S. Small Business Administration has determined do not realistically reflect the potential for small business participation in federal procurement (such as those awarded to mandatory and directed sources), contracts funded predominately from agency-generated sources (i.e., non-appropriated funds), contracts not covered by the Federal Acquisition Regulations System, acquisitions on behalf of foreign governments, and contracts not reported in the GSA's Federal Procurement Data System—Next Generation (such as government procurement card purchases and contracts valued less than $10,000). About 15% to 18% of all federal contracts are excluded in any given fiscal year.

The WOSB Program's Origins

The following sections provide an overview of the history of small business contracting preferences, focusing on executive, legislative, and judicial actions that led to the creation of the WOSB program and influenced its structure.

Federal Agency Small Business Procurement Goals and Executive Order 12138: A National Program for Women's Business Enterprise

Since 1978, federal agency heads have been required to establish federal procurement goals, in consultation with the SBA, "that realistically reflect the potential of small business concerns and small business concerns owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals" to participate in federal procurement. These reports are submitted to Congress and are presently made available to the public on the General Services Administration's (GSA's) website. Initially, WOSB goals were not included.16

On May 18, 1979, President Jimmy Carter issued Executive Order 12138, which established a national policy to promote women-owned business enterprises.17 Among other provisions, the executive order required federal agencies "to take appropriate affirmative action in support of women's business enterprise," including promoting procurement opportunities and providing financial assistance and business-related management and training assistance.18

Under authority provided by Executive Order 12138, the SBA added WOSB procurement goals to the list of small business contracting goals it negotiated with federal agencies. At that time, WOSBs received about 0.2% of all federal contracts.19 By 1988, this percentage had grown, but to only 1% of all federal contracts.20

WOSB advocates argued that additional action was needed to help WOSBs win federal contracts because women-owned businesses are subject to "age-old prejudice, discrimination, and exploitation," the "promotion of women's business enterprise is simply not a high priority" for federal agencies, and federal "agency efforts in support of women's business enterprise have been weak and have produced little, if any measurable results."21 Their efforts led to P.L. 100-533, the Women's Business Ownership Act of 1988.

P.L. 100-533 provided the SBA statutory authorization to establish WOSB annual procurement goals with federal agencies. The act also extended the goaling requirement to include subcontracts, as well as prime contracts, and added WOSBs to the list of small business concerns to be identified in required small business subcontracting plans (at that time, small business subcontracting plans were required for prime contracts exceeding $500,000, or $1 million for the construction of any public facility).22

Government-Wide Small Business Procurement Goals

In a related development, P.L. 100-656, the Business Opportunity Development Reform Act of 1988, authorized the President to annually establish government-wide minimum procurement goals for small businesses and small businesses owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals (SDBs). Congress required the government-wide minimum goal for small businesses to be "not less than 20% [increased to 23% in 1997] of the total value of all prime contract awards for each fiscal year" and "not less than 5% of the total value of all prime contract and subcontract awards for each fiscal year" for SDBs.23

Advocates for a WOSB government-wide procurement goal argued that women owned approximately one third of the nation's businesses but received "a mere 1.3% of federal contracting dollars ... in FY1990."24 Their efforts led to P.L. 103-355, FASA.

FASA created a 5% procurement goal for WOSBs each fiscal year. The 5% goal was implemented by regulations effective in FY1996.25

The conferees indicated in FASA's conference agreement that they did "not intend to create a new set aside or program of restricted competition for a specific designated group, but rather to establish a target that will result in greater opportunities for women to compete for federal contracts."26 The conferees added that "given the slow progress to date in reaching the current award levels, the conferees recognize that this goal may take some time to be reached."27

Subsequently, 3% procurement goals were created for HUBZone small businesses (P.L. 105-135, the HUBZone Act of 1997; Title VI of the Small Business Reauthorization Act of 1997) and SDVOSBs (P.L. 106-50, the Veterans Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development Act of 1999).28

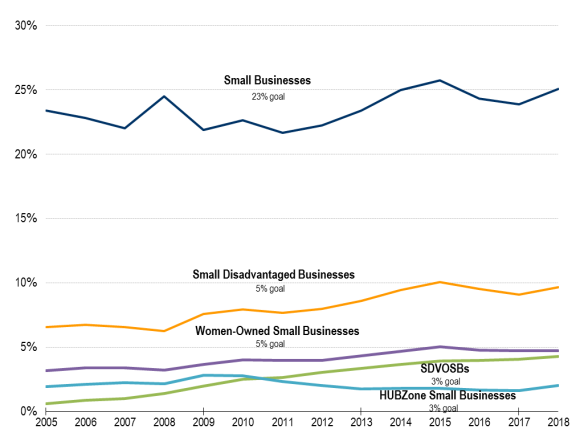

Figure 1 shows the percentage of small business-eligible federal contracts awarded to small businesses, SDBs, WOSBs, SDVOSBs, and HUBZone small businesses from FY2005 through FY2018. As detailed in the figure's notes, the small business-eligible baseline excludes certain contracts that the SBA has determined do not realistically reflect the potential for small business participation in federal procurement. About 15% to 18% of all federal contracts are excluded in any given fiscal year.

The federal government has had difficulty meeting the WOSB and HUBZone small business procurement goals. As mentioned in Figure 1's notes, the 5% procurement goal for WOSBs was achieved in only 1 of the 14 fiscal years (FY2015) reported in the figure. The 3% procurement goal for HUBZone small businesses was not achieved in any of the 14 fiscal years. In contrast, the 23% procurement goal for all types of small businesses was achieved in 8 of the 14 fiscal years reported in the figure (FY2005, FY2008, and FY2013-FY2018), including the past 6 fiscal years. The 5% procurement goal for SDBs was achieved in each of the 14 fiscal years. The 3% procurement goal for SDVOSBs was achieved in 7 of the 14 fiscal years (FY2012-FY2018), including the last 7 fiscal years.

|

Figure 1. Small Business Contracting, Performance, by Type of Small Business, FY2005-FY2018 (% of small business eligible federal contracts) |

|

|

Source: U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), Federal Procurement Data System – Next Generation, Small Business Goaling Report [FY2005-FY2018], at https://www.fpds.gov/fpdsng_cms/index.php/en/reports.html. Notes: The small business eligible baseline excludes certain contracts that the Small Business Administration has determined do not realistically reflect the potential for small business participation in federal procurement (such as those awarded to mandatory and directed sources), contracts funded predominately from agency-generated sources (i.e., non-appropriated funds), contracts not covered by the Federal Acquisition Regulations System, acquisitions on behalf of foreign governments, and contracts not reported in the GSA's Federal Procurement Data System—Next Generation (such as government procurement card purchases and contracts valued less than $10,000). About 15% to 18% of all federal contracts are excluded in any given fiscal year. The 23% procurement goal for small businesses was achieved in 8 of the 14 fiscal years reported in the table (FY2005, FY2008, and FY2013-FY2018). The 5% procurement goal for small disadvantaged businesses was achieved in each of the 14 fiscal years. The 5% procurement goal for women-owned small businesses was achieved in 1 of the 14 fiscal years (FY2015). The 3% procurement goal for service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses (SDVOSBs) was achieved in 7 of the 14 fiscal years (FY2012-FY2018). The 3% procurement goal for HUBZone small businesses was not achieved in any of the 14 fiscal years. |

WOSB Set-Asides

As shown in Table 1, FASA conferees' prediction that it may take some time to reach the 5% goal was confirmed. The amount and percentage of federal contracts awarded to WOSBs increased slowly following the establishment of the 5% goal (implemented in FY1996).

Frustrated by the relatively slow progress toward meeting the 5% goal, WOSB advocates began to lobby for additional actions, including the establishment of a federal contracting set-aside program for WOSBs. As mentioned, a set-aside is a commonly used term to refer to a contract competition in which only small businesses, or specific types of small businesses, may compete.

WOSB advocates noted that other small businesses were provided contracting preferences. For example, at that time, SDBs were eligible for contract set-asides and a price evaluation adjustment of up to 10% in full and open competition in specified federal agencies, including the Department of Defense (DOD); participants in the SBA's 8(a) program were (and still are) eligible for both contract set-asides and sole source awards; and HUBZone small businesses were (and still are) eligible for contract set-asides, sole source awards, and a price evaluation adjustment of up to 10% in full and open competition above the simplified acquisition threshold.29

As a first step toward the enactment of a WOSB set-aside contracting program, P.L. 106-165, the Women's Business Centers Sustainability Act of 1999, required GAO to review the federal government's efforts to meet the 5% goal for WOSBs and to identify any measures that could improve the federal government's performance in increasing WOSB contracting opportunities. GAO issued its report on February 16, 2001:

Among the government contracting officials with whom we spoke, there was general agreement on several suggestions for improving the environment for contracting with WOSBs and increasing federal contracting with WOSBs. They suggested creating a contract program targeting WOSBs, focusing and coordinating federal agencies' WOSB outreach activities, promoting contracting with WOSBs through agency incentive and recognition programs, including WOSBs in agency mentor-protégé programs, providing more information to WOSBs about participation in teaming arrangements, and providing expanded contract financing.30

By the time the GAO report was published, legislation had been enacted (H.R. 5654, the Small Business Reauthorization Act of 2000, incorporated by reference in P.L. 106-554, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2001) to authorize the WOSB program. As mentioned, the WOSB program provides greater access to federal contracting opportunities for WOSBs by providing federal contracting officers authority to set aside contracts for WOSBs (including EDWOSBs) exclusively in industries in which WOSBs are substantially underrepresented, and to set aside contracts for EDWOSBs exclusively in industries in which WOSBs are underrepresented.

A Targeted Approach to Avoid Legal Challenges

Congressional efforts to promote WOSB set-asides were complicated by Supreme Court decisions on legal challenges of contracting preferences for minority contractors, including City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (1989) (finding unconstitutional a municipal ordinance that required the city's prime contractors to award at least 30% of the value of each contract to minority subcontractors) and Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena (1995) (finding that all racial classifications, whether imposed by federal, state, or local authorities, must pass strict scrutiny review).

The Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena case involved a challenge to federal subcontracting preferences for SDBs. The plaintiff claimed that contracting preferences based on race violate the equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause. The Supreme Court ruled that all racial classifications, whether imposed by federal, state, or local authorities, must pass strict scrutiny review (i.e., they must serve a compelling government interest and must be narrowly tailored to further that interest). Following the Adarand decision, the federal government reexamined how it implemented "affirmative action" programs, including certain procurement preference programs.

When developing the WOSB set-aside program, its advocates were aware that the WOSB program would be subject to a heightened standard of judicial review given the Supreme Court's ruling that all racial classifications must serve a compelling government interest and be narrowly tailored. In the House report accompanying H.R. 4897, the Equity in Contracting for Women Act of 2000 (which was incorporated into H.R. 5654, the Small Business Reauthorization Act of 2000), advocates argued that a set aside program was needed (compelling interest) because of the slow progress in meeting the 5% procurement goal for WOSBs. The report noted that "the drive for efficiency in procurement often places Congressionally-mandated contracting goals for small businesses in general, and women-owned small businesses in particular, in jeopardy."31 The report also noted that contract bundling (the consolidation of smaller contract requirements into larger contracts) and the increased use of the Federal Supply Schedules increase "the efficiency of government procurements ... [but] also may perpetuate the use of well-known firms that are not women-owned businesses."32 As a result,

the Committee believes that the goals expressed in FASA and reaffirmed in the Executive Order [Executive Order 13,157, issued on May 23, 2000 by President Clinton, reaffirming the Administration's support for increasing contracting opportunities for WOSBs] will not be achieved without the use of some mandatory tool which enables contracting officers to identify WOSBs and establish competition among those businesses for the provision of goods and services.33

The House report also argued that the bill was narrowly tailored because it did not establish sole source authority for WOSBs and limited WOSB set-asides to industries in which WOSBs are underrepresented in obtaining federal contracts.

WOSB Program Requirements

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2001 (P.L. 106-554) specified that federal contracting officers could not set aside contracts for WOSBs or EDWOSBs unless (1) they had a reasonable expectation that two or more eligible business concerns would submit offers for the contract, (2) the anticipated award price of the contract (including options) does not exceed $5 million for manufacturing contracts and $3 million for all other contracts, and (3) the contract award can be made at a fair and reasonable price.

In 2011, the set-aside award caps were increased to $6.5 million for manufacturing contracts and $4 million for all other contracts to account for inflation.34 In 2013, P.L. 112-239, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013, removed the caps.35

Eligibility Requirements

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2001 (P.L. 106-554) also specified recipient eligibility requirements (see below) and required the SBA to conduct a study to identify industries in which WOSBs are underrepresented (and, by inference, substantially underrepresented) with respect to federal procurement contracting. In addition, the SBA had to develop criteria to define an EDWOSB because the act did not define economic disadvantage. The WOSB program could not begin until those determinations were made.

To participate in the program, the act specified that WOSBs must

- be a small business (as defined by the SBA);

- be at least 51% unconditionally and directly owned and controlled by one or more women who are U.S. citizens;36

- have women manage day-to-day operations and make long-term decisions; and

- be certified by a federal agency, a state government, the SBA, or a national certifying entity approved by the SBA or self-certify their eligibility to the federal contracting officer with adequate documentation according to standards established by the SBA.

Certification

As mentioned, P.L. 113-291 (NDAA 2015), among other provisions, removed the ability of small businesses to self-certify their eligibility for the WOSB program as a means to ensure that the program's contracts are awarded only to intended recipients. The act also required the SBA to implement its own certification process for WOSBs. The SBA anticipates implementing a certification process for the WOSB program and removing the ability of small businesses to self-certify their eligibility for the WOSB program by July 2020.37

In the meantime, WOSBs and EDWOSBs must be either self-certified or third-party certified to participate in the WOSB program. Self-certification requires the business to provide certification information annually through the SBA's certification web page (certify.SBA.gov) and have an up-to-date profile on the System for Award Management (SAM) website (sam.gov) indicating that the business is small and is interested in participating in the WOSB program.38 Self-certification is free.

In addition, in 2011, the SBA approved four organizations that continue to provide third-party certification (typically involving a fee): El Paso Hispanic Chamber of Commerce, National Women Business Owners Corporation, U.S. Women's Chamber of Commerce, and Women's Business Enterprise National Council.39

Defining Economic Disadvantage

EDWOSBs must meet all WOSB contracting program requirements and be economically disadvantaged, which, as presently defined by the SBA, means that they must be

- owned and controlled by one or more women, each with a personal net worth less than $750,000;

- owned and controlled by one or more women, each with $350,000 or less in adjusted gross income averaged over the previous three years; and

- owned and controlled by one or more women, each with $6 million or less in personal assets.

The SBA defined economic disadvantage using its experience with the 8(a) program as a guide (i.e., reviewing the owner's income, personal net worth, and the fair market value of her total assets).40

As of April 22, 2020, there were 65,125 WOSBs and 23,893 EDWOSBs registered in the SBA's online database.41

The 10-Year Delay in WOSB's Implementation

As mentioned, the WOSB program's implementation was delayed for over 10 years, primarily due to the SBA's difficulty in identifying an appropriate methodology to determine "the industries in which WOSBs are underrepresented (and, by inference, substantially underrepresented) with respect to federal procurement contracting."42

The SBA completed a draft of the legislatively mandated study of underrepresented (and, by inference, substantially underrepresented) NAICS industrial codes in September 2001, using internal resources. The SBA then submitted proposed regulations to implement the WOSB program to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which is required by law to review all draft regulations before publication within 90 days of their submission to OMB.43 However, the SBA withdrew the regulations on April 24, 2002, before the review was complete "because the SBA Administrator had concerns about the content and constitutionality of its draft industry study and believed that it needed to contract with the National Academy of Science (NAS) to review the draft industry study and recommend any changes the NAS believed were necessary."44 The SBA awarded a contract to NAS in late 2003 to conduct the study.

NAS completed its analysis and issued a report on the SBA's study on March 11, 2005. The report indicated that the SBA asked NAS to conduct the review "because of the history of legal challenges to race- and gender-conscious contracting programs at the federal and local levels."45

NAS concluded that the SBA's study was "problematic in several respects, including that the documentation of data sources and estimation methods is inadequate for evaluation purposes." NAS made several recommendations for a new study, including that the SBA use more current data, different industry classifications, and consistent monetary and numeric utilization measures to provide more complete documentation of data and methods.46 The SBA later characterized NAS's analysis as indicating that the SBA study was "fatally flawed."47 In response to that finding, the SBA issued a solicitation in October 2005, seeking a private contractor to perform a revised study. In February 2006, a contract was awarded to the Kaufman-RAND Institute for Entrepreneurship Public Policy (RAND). The RAND study was published in April 2007.48

The RAND report noted that underrepresentation is typically referred to as a disparity ratio, a measure comparing the use of firms of a particular type (in this case, WOSBs) in a particular NAICS code to their availability for such contracts in that NAICS code. A disparity of 1.0 suggests that firms of a particular type are awarded contracts in the same proportion as their representation in that industry (there is no disparity). A disparity ratio less than 1.0 suggests that the firms are underrepresented in federal contracting in that NAICS code. A ratio greater than 1.0 suggests that the firms are overrepresented.49

RAND identified 28 different approaches to determine underrepresentation and substantial underrepresentation of WOSBs in federal procurement, each of which yielded a different result. After examining each approach's benefits and deficiencies, the SBA defined underrepresentation as industries having a disparity ratio between 0.5 and 0.8, where the ratio represents the WOSB share of federal prime contract dollars divided by the WOSB share of total business receipts within a given NAICS code. Substantial underrepresentation was defined as industries with a disparity ratio between 0.0 and 0.5.50

Using that methodology, the SBA identified 83 four-digit NAICS industry groups in its final rule implementing the WOSB program (October 7, 2010, effective February 4, 2011):

- 45 four-digit NAICS industry groups in which WOSBs are underrepresented (225 out of the 1,057 six-digit NAICS industry codes at that time were made eligible for EDWOSB set-asides only), and

- 38 four-digit NAICS industry groups in which WOSBs are substantially underrepresented (171 out of the 1,057 six-digit NAICS industry codes at that time were made eligible for WOSB (including EDWOSB) set-asides).51

Mandated Updates of Underrepresented and Substantially Underrepresented NAICS Codes

In 2014, Congress passed legislation (P.L. 113-291) requiring the SBA to update the list of underrepresented and substantially underrepresented NAICS codes by January 2, 2016, and then conduct a new study and update the NAICS codes every five years thereafter. The SBA asked the Department of Commerce's Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) for assistance in conducting a new study.

The OCE examined the odds of women-owned businesses winning a federal prime contract relative to otherwise similar firms in FY2013 and FY2014 in each of the four-digit NAICS code industry groups, controlling for the firm's size and age, legal form of organization, level of government security clearance, past federal prime contracting performance ratings, and membership in various categories of firms having federal government-wide procurement goals. OCE found that women-owned businesses were less likely to win federal contracts in 254 of the 304 industry groups in the study, and women-owned businesses in 109 of the 304 industry groups had statistically significant lower odds of winning federal contracts than otherwise similar businesses not owned by women at the 95% confidence level.52

Based on the OCE study, the SBA increased the number of underrepresented and substantially underrepresented four-digit NAICS codes from 83 to 113, effective March 3, 2016 (21 in which WOSBs are underrepresented (EDWOSB set-asides only) and 92 in which WOSBs are substantially underrepresented (WOSB and EDWOSB set-asides).53

OMB updates the NAICS every five years. In response to OMB's release of NAICS 2017, which replaced NAICS 2012, the SBA reduced the number of underrepresented and substantially underrepresented four-digit NAICS codes from 113 to 112, effective October 1, 2017. The reduction took place because NAICS 2017 merged two four-digit NAICS industry groups that affected the WOSB program. The merger also resulted in the number of four-digit NAICS industry groups in which WOSBs are substantially underrepresented (WOSB and EDWOSB set-asides) to fall from 92 to 91.54 Overall, WOSB set-asides may be provided to WOSBs (including EDWOSBs) in 364 (out of 1,023) six-digit NAICS industry codes and to EDWOSBs exclusively in 80 (out of 1,023) six-digit NAICS industry codes.55

Sole Source Award Authority

P.L. 113-291 (NDAA 2015), enacted in 2014, provides federal agencies authority to award sole source contracts to WOSBs (including EDWOSBs) eligible under the WOSB program if

- the contract is assigned a NAICS code in which the SBA has determined that WOSBs are substantially underrepresented in federal procurement;

- the contracting officer does not have a reasonable expectation that offers would be received from two or more WOSBs (including EDWOSBs); and

- the anticipated total value of the contract, including any options, is below $4 million ($6.5 million for manufacturing contracts).56

- NDAA 2015 also provides federal agencies authority to award sole source contracts exclusively to EDWOSBs eligible under the WOSB program if

- the contract is assigned a NAICS code in which SBA has determined that WOSB concerns are underrepresented in federal procurement;

- the contracting officer does not have a reasonable expectation that offers would be received from two or more EDWOSB concerns; and

- the anticipated total value of the contract, including any options, is below $4 million ($6.5 million for manufacturing contracts).57

Expanding the WOSB program to include sole source contracts was designed, along with WOSB set-asides, to help federal agencies achieve their statutory goal of awarding at least 5% of their federal contracting dollars to WOSBs. The SBA published a final rule expanding the WOSB program to include sole source awards on September 14, 2015 (effective October 14, 2015).58

Current Administrative Issues

Both GAO and the SBA's OIG have issued reports and audits of the WOSB program that have been critical of the SBA's implementation and oversight of the program.59 For example, GAO has criticized the SBA for delays in implementing the WOSB program and, in 2019, reported that the SBA had not fully addressed WOSB program oversight deficiencies, first identified by GAO in 2014, related to third-party certifiers, the procedures used to conduct annual eligibility examinations of WOSBs, and "reviews of individual businesses found to be ineligible to better understand the cause of the high rate of ineligibility in annual reviews and determine what actions are needed to address the causes."60 GAO argued that

the deficiencies in SBA's oversight of the WOSB program limit SBA's ability to identify potential fraud risks and develop any additional control activities to address these risks. As a result, the program continues to be exposed to the risks of ineligible businesses receiving set-aside contracts. 61

In addition, GAO noted that, from April 2011 through June 2018, about 3.5% of WOSB set-aside contracts were awarded for ineligible goods or services [NAICS codes].62

In 2015, the SBA's OIG analyzed 34 WOSB program awards made between October 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, (17 WOSB set-aside awards totaling $6.6 million and 17 EDWOSB set-aside awards totaling $7.9 million) and found "15 of the 34 set-aside awards were made without meeting the WOSB program's requirements," and these awards totaled approximately $7.1 million.63 Specifically, 10 of the 34 WOSB program set-aside awards were made "for work that was not eligible to be set aside for the program" and 9 of the 34 awards went to firms that did not have any documentation in the WOSB program's repository, including 7 of the 17 WOSB set-aside awards, or 41%, and 2 of the 17 EDWOSB set-aside awards, or 12%."64 The SBA OIG found that "this occurred because agencies' contracting officers did not comply with the regulations prior to awarding these awards and SBA did not provide enough outreach or training to adequately inform them of their responsibilities and the program's requirements."65

In a related development, in 2018, the SBA's OIG analyzed 56 WOSB sole source contracts awarded between January 1, 2016, and April 30, 2017, and found that 50 of the 56 contracts, totaling approximately $52.2 million, were made "without having the necessary documentation to determine eligibility" of the award recipients.66 Examples of missing documentation included WOSB and EDWOSB self-certifications, articles of incorporation, birth certificates, and financial information.67

Current Oversight and Legislative Issues

The SBA's WOSB program is likely to be of continued interest to Congress during the remainder of the 116th Congress. Issues of particular interest to Congress may include congressional oversight of the SBA's implementation of the WOSB program's certification procedures; congressional oversight of the SBA's training of federal procurement officers to ensure that WOSB awards are made only to eligible firms in eligible industries; the performance of federal agencies in achieving the 5% procurement goal for WOSBs; and the WOSB program's efficacy in helping to meet the 5% goal.

As shown in Table 1, federal procurement officers' use of the WOSB program has increased from about $21 million in FY2011 to $893 million in FY2018, with most of that increase resulting from rising use of WOSB set-asides (from $15 million in FY2011 to $742 million in FY2018). Although WOSB program usage is increasing, WOSB set-asides and sole source awards continue to account for a relatively small portion of the federal contracts awarded to WOSBs. Although the WOSB program has been operational since 2011, many federal agencies have little experience with the program.

For example, in FY2018, about 63% of the federal contracts awarded to WOSBs were awarded in full and open competition with other firms, about 33% were awarded with another small business preference (such as the 8(a) and HUBZone programs), and about 4% were awarded with a WOSB preference.68

Also, GAO found that from the third quarter of FY2011 through the third quarter of FY2018, six federal agencies accounted for nearly 83% of the contract amount awarded under the WOSB program: DOD (48.6%), Department of Homeland Security (DHS) (12.4%), Department of Commerce (8.0%), Department of Agriculture (6.3%), Department of Health and Human Services (4.0%), and GSA (4.0%). All other federal agencies accounted for 16.8%.69

GAO conducted an audit of the WOSB program from October 2017 to March 2019. As part of the audit, GAO interviewed 14 stakeholder groups (staff from DHS, DOD, and GSA, eight contracting officers within these agencies, and three WOSB third-party certifiers) to obtain their views on WOSB program usage. The stakeholder groups identified several positive aspects about the WOSB program, including that it provided WOSBs greater opportunities to win federal contracts, and that the SBA had several initiatives underway to help improve collaboration between federal agencies and the small business community.70 The stakeholders also identified several impediments that limited the WOSB program's use by federal contracting officers, including the following:

- Sole Source Authority Rules.

Executing sole source authority under the WOSB program is difficult for contracting officers because rules for sole source authority under the WOSB program are different from those under SBA programs.... For example, the FAR's [Federal Acquisition Regulation] requirement that contracting officers must justify, in writing, why they do not expect other WOSBs or EDWOSBs to submit offers on a contract is stricter under the WOSB program that it is for the 8(a) program.71

- Industry Restrictions.

13 of the 14 stakeholder groups ... commented on the requirement that WOSB program set-asides be awarded within certain industries, represented by NAICS codes. For example, two third-party certifiers ... recommended that the NAICS codes be expanded or eliminated to provide greater opportunities for WOSBs to win contracts under the program.72

- Eligibility Documentation Requirements.

7 of the 14 stakeholder groups discussed the requirement for the contracting officer to review program eligibility documentation and how this requirement affects their decision to use the program.

For example, staff from one contracting office said that using the 8(a) or HUBZone programs is easier because 8(a) and HUBZone applicants are already certified by the SBA; therefore, the additional step to verify documentation for eligibility is not needed.... GSA officials noted that eliminating the need for contracting officers to take additional steps to review eligibility documentation for WOSB-program set-asides could create more opportunities for WOSBs by reducing burdens on contracting officers.73

- Need for Additional Guidance.

13 of the 14 stakeholder groups discussed guidance available to federal contracting officers under the WOSB program. For example, two third-party certifiers identified the need for additional training and guidance for federal contracting officers, and staff from two federal contracting offices said that the last time that they had received training on the WOSB program was in 2011, when the program was first implemented.74

In a related development, the House passed legislation (H.R. 190, the Expanding Contracting Opportunities for Small Businesses Act of 2019) which would, among other provisions, eliminate the inclusion of option periods in the award price for sole source contracts awarded to qualified HUBZone small businesses, SDBs, SDVOSBs, and WOSBs (including EDWOSBs). This provision would increase the number of contracts available for sole source awards to these recipients because the option years would not count toward the statutory caps on sole source awards (the WOSB caps are currently $6.5 million for manufacturing contracts and $4 million for other contracts). The bill would also increase the WOSB sole source cap to $7 million for manufacturing contracts to align them with the $7 million cap for the HUBZone and 8(a) program small businesses.75

Also, some WOSB advocates have suggested that the WOSB program should be amended to (1) eliminate the distinction and disparate treatment of WOSBs and EDWOSBs when awarding contracts, and/or (2) allow set-asides and sole source awards to WOSBs (including EDWOSBs) in all NAICS industry codes regardless of WOSB representation, as is the case for other small business preference programs.76 Both legislative options could lead to an increase in the amount of contracts awarded to WOSBs. In the first instance, WOSBs would be eligible for set-asides and sole source awards in both underrepresented and substantially underrepresented NAICS codes, instead of just substantially underrepresented NAICS codes. In the latter instance, WOSBs and EDWOSBs would be eligible for set-asides and sole source awards in all NAICS industry codes, not just underrepresented or substantially underrepresented NAICS industry codes.

As mentioned in the "A Targeted Approach to Avoid Legal Challenges" section, one of the reasons the WOSB program provides disparate treatment to WOSBs and EDWOSBs, and makes distinctions among underrepresented, substantially underrepresented, and other NAICS industry codes was to address the heightened level of legal scrutiny related to contracting preferences following the Supreme Court's decision in Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena. The Supreme Court ruled that all racial classifications, whether imposed by federal, state, or local authorities, must pass strict scrutiny review (i.e., they must serve a compelling government interest and must be narrowly tailored to further that interest). Although the WOSB program is not based on racial classifications, it was expected to receive a heightened level of judicial scrutiny. As such, it lead the WOSB program's advocates to create these distinctions in an effort to shield it from legal challenges.

Concluding Observations

As mentioned in the "Introduction," the WOSB program is one of several contracting programs that Congress has approved to provide greater opportunities for small businesses to win federal contracts. Its legislative history is a bit more complicated than others, primarily due to the distinctions between WOSBs and EDWOSBs and among underrepresented, substantially underrepresented, and other NAICS codes. These distinctions, and the SBA's difficulty in defining them, led to the 10-year delay in the program's implementation and may also help to explain why the SBA's implementation of the SBA's certification program has been delayed.

The SBA's implementation of the WOSB program is likely to remain a priority for congressional oversight during the 116th Congress, as is federal agency use of the program. As mentioned, the federal government has met the 5% procurement goal for WOSBs only once (in FY2015) since the goal was authorized in 1994, and implemented in FY1996.

Also, the data on WOSB federal contract awards suggest that federal procurement officers are using the WOSB program more often than in the past, but the program accounts for a relatively small portion of WOSB contracts. Most of the federal contracts awarded to WOSBs are awarded in full and open competition with other firms or with another small business preference program (such as the 8(a) and HUBZone programs). Relatively few federal contracts are awarded through the WOSB program. Determining why this is the case, and if anything can, or should be done to address this, is likely to be of continuing congressional interest.