Overview

Cross-border data flows underlie today's globally connected world and are essential to conducting international trade and commerce. Data flows enable companies to transmit information for online communication, track global supply chains, share research, and provide cross-border services. One study estimates that the flow of digital data will increase global GDP by $3,691 billion in 2020.1 However, while cross-border data flows increase productivity and enable innovation, they also raise concerns around the security and privacy of the information being transmitted.

Cross-border data flows are central to trade and trade negotiations as organizations rely on the transmission of information to use cloud services, and to send nonpersonal corporate data as well as personal data to partners, subsidiaries, and customers. U.S. policymakers are considering various policy options to address online privacy, some of which could affect cross-border data flows. For example, new consumer rights to control personal data may impact how companies can use such data. To enable international data flows and trade, the United States has aimed to eliminate trade barriers and establish enforceable international rules and best practices that allow policymakers to achieve public policy objectives, including promoting online security and privacy.

In 2020, the world has an abundance of data but no global rules governing use or protection of that data. Building consensus for international rules and norms on data flows and privacy has become increasingly important, as recent incidents have heightened the public's awareness of the risk of personal data stored online. For example, the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal drew attention because the firm reportedly acquired and used data on more than 87 million Facebook accounts in an effort to influence voters in the 2016 U.S. presidential election and the United Kingdom (UK) referendum on continued European Union (EU) membership ("Brexit").2 In addition, security concerns have been raised about data breaches, including that of credit reporting agency Equifax that exposed the sensitive financial and personal records of nearly 150 million Americans (and foreigners) or the Marriott breach which involved the personal data of 500 million hotel customers.3 The Department of Justice has since charged China's military in both cases.4

Organizations value consumers' personal online data for a variety of reasons. For example, companies may seek to facilitate business transactions, analyze marketing information, detect disease patterns from medical histories, discover fraudulent payments, improve proprietary algorithms, or develop competitive innovations. Some analysts compare data to oil or gold, but unlike those valuable substances, data can be reused, analyzed, shared, and combined with other information; it is not a scarce resource.

Personal data is widely considered personal private property. Individuals often want to control who accesses their data and how it is used. Experts suggest that data may therefore be considered both a benefit and a liability that organizations hold. Data has value, but an organization takes on risk by collecting personal data; the organization becomes responsible for protecting users' privacy and not misusing the information. Data privacy concerns may become more urgent with expansion of both (1) the amount of online information organizations access and collect, and (2) the level of global data flows.5

Countries vary in their policies and laws on these issues. The United States has traditionally supported open data flows and has regulated privacy at a sectoral level to cover certain types of data, such as health records, although Congress is currently debating potential comprehensive national policy. U.S. trade policy has sought to balance the goals of consumer privacy, security, and open commerce, including eliminating trade barriers and opening markets. Other countries are developing data privacy policies that affect international trade as some governments or groups seek to limit data flows outside of an organization or across national borders for a number of reasons. Blocking international data flows may impede the ability of a firm to do business or of an individual to conduct a transaction, creating a form of trade protectionism. Research demonstrates not only the economic gains from digital trade and international data flows, but also the real economic costs of restrictions on such flows.6

For many policymakers, the crux of the issue is: How can governments protect individual privacy in the least trade-restrictive way possible? The question is similar to concerns raised about ensuring cybersecurity while allowing the free flow of data. In recent years, Congress has examined multiple issues related to cross-border data flows and online privacy.

In the 115th Congress and H.R. 5815 116th Congress, congressional committees held hearings on these topics,7 introduced multiple bills,8 and conducted oversight over federal laws on related issues such as data breach notification.9 Although data privacy crosses multiple committee jurisdictions, some have had greater focus on the topic than others. For example, the Chair and Ranking Member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation have each released their own version of proposed legislation that illustrate areas of differences and bipartisan alignment.10 Congress may review the digital trade chapter of the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement as examples of the current U.S. approach through trade agreements and as potential templates for future U.S. trade agreements.

Defining Online Privacy

In most circumstances, a consumer expects both privacy and security when conducting an online transaction. However, users' expectations and values may vary, and there is no globally accepted standard or definition of data privacy in the online world. In addressing online privacy, Congress may need to define personal data and differentiate between sensitive and nonsensitive personal data. In general, data privacy can be defined by an individual's ability to prevent access to personally identifiable information (PII).

According to the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance to federal agencies, PII refers to

information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual's identity, either alone or when combined with other information that is linked or linkable to a specific individual.11

Since electronic data can be readily shared and combined, some data not traditionally considered PII may have become more sensitive. For example, the OMB definition does not specifically mention data on location tracking, purchase history, or preferences, but these digital data points can be tracked by a device such as a mobile phone or laptop that an individual carries or logs into. The EU definition of PII attempts to capture the breadth of data available in the online world:

"personal data" means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person ('data subject'); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.12

The two Senate Commerce Committee draft bills mentioned previously generally align with the OMB definition, covering data that identifies or is linked or reasonably linkable to an individual or a consumer device, including derived data, but excluding de-identified or aggregated data, employee data, and public records. In addition, the policymakers each included provisions differentiating between sensitive and nonsensitive personal data. For example, sensitive personal data could include ethnic origin, political or religious affiliation, biometric data, health data, sexual orientation, precise geolocation data, and online activities. One concern is how potential U.S. legislation and subsequent regulation would define each of these terms.

Cross-Border Data Flows and Online Privacy

"Cross-border data flows" refers to the movement or transfer of information between computer servers across national borders. Cross-border data flows are part of, and integral to, digital trade and facilitate the movement of goods, services, people, and finance. One analysis estimated that digitally enabled trade was worth between $800-$1,500 billion globally in 2019.13 Effective and sustainable digital trade relies on data flows that permit commerce and communication but that also ensure privacy and security, protect intellectual property, and build trust and confidence. Impeding cross-border data flows, including through some privacy regulations, may decrease efficiency and reduce other benefits of digital trade, resulting in the fracturing, or so-called balkanization, of the internet.14

In addressing online privacy, some policymakers focus on limiting access to online information by restricting the flow of data beyond a country's borders. Such limits may also act as protectionist measures. Online privacy policies may create barriers to digital trade, or damage trust in the underlying digital economy. For example, measures to limit cross-border data flows could

- block companies from using cloud computing to aggregate and analyze global data, or from gaining economies of scale,

- The world produces 2.5 quintillion bytes a day.15

- More than 50% of businesses globally rely on data flows for cloud computing.16

- One-third of total sales on the Etsy platform are international, relying on international data flows.17

- Data localization rules impeding data flows are the #1 digital trade barrier cited by U.S. firms.18

- prevent companies from offering cross-border services to customers via the internet including entertainment and marketing,

- constrain e-commerce by limiting international online payments,

- hinder global supply chains seeking to use blockchain to track products or manage supply chains, customs documentation, or electronic payments,19

- impede the trading of crypto-currency, or

- limit the use of advanced technology like artificial intelligence that rely on collecting large data sets.20

|

Business and Cross-Border Data Flows |

According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), one of the most significant overall impacts of the growth of digital technologies is in transforming international trade. Technology can lower the costs of trade, change the types of goods and services that are traded, and may even change the factors defining a country's comparative advantage.21 The extent of the impact of digital technologies on trade, however, depends in large part on open cross-border data flows.

One study of U.S. companies found that data localization rules (i.e., requiring organizations to store data on local servers) were the most-cited digital trade barrier.22 Some governments advocate privacy or security policies that require data localization and limit cross-border data flows. However, many industry stakeholders argue that blocking cross-border data flows and storing data domestically does not make such data more secure or private.23

Balancing Policy Objectives

Many experts argue that policymakers should limit cross-border data flows in the least trade-restrictive manner possible and also ensure security and privacy. These objectives are not easily reconciled. Although an overlap exists between data protection and privacy, the two are not equivalent.

Cybersecurity measures are essential to protect data (e.g., against intrusions or theft by hackers). However, they may not be sufficient to protect privacy. For example, if an organization shares user data with a third party, it may be doing so securely, but not in a way that protects users' privacy or aligns with consumer expectations. Similarly, breach notification requirements are not the same as proactive privacy protection measures.24 At the same time, policies that protect a consumer's privacy can align with security policies. Laws can limit law enforcement's access to information except in certain circumstances. Keeping user information anonymous may enable firms to analyze and process data while protecting individuals' identities. The ongoing debate over employing encryption to protect individual security and privacy versus concerns about law enforcement and national security is related but distinct from cross-border data flows issues.25

Some see an inherent conflict between online security, privacy, and trade; others believe that policies protecting all three can be coherent and consistent.26 The U.S. government has traditionally sought to balance these objectives. Some stakeholders note, however, that current U.S. policy has been inadequate in protecting online privacy and seek proactive legislation to protect personal data. In some cases in the past, Congress has acted to address privacy concerns in particular sectors; for example, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 led to health privacy standards regulations.27 New rules by the Trump Administration that aim to allow patients to share their data online using common data standards are raising concerns about potential gaps in patient data privacy for entities such as app providers (e.g., Apple) who are not covered by HIPAA.28 The Administration has begun an effort to devise an overarching data privacy policy (see "Defining the U.S. Approach") and some Members of Congress are also considering possible approaches.

Multilateral Rules

There are no comprehensive multilateral rules specifically about privacy or cross-border data flows. The United States and other countries have begun to address these issues in negotiating new and updated trade agreements, and through international economic forums and organizations such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services

The World Trade Organization General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) entered into force in January 1995, predating the current reach of the internet and the explosive growth of global data flows.29 Many digital products and services that did not exist when the agreements were negotiated are not covered. On the other hand, privacy is explicitly addressed within GATS as an exception to allow countries to take measures that do not conform with the agreement in order to protect "the privacy of individuals in relation to the processing and dissemination of personal data and the protection of confidentiality of individual records and accounts," as long as those measures are not arbitrary or a disguised trade restriction.30

Efforts to update the multilateral agreement and discussions for new digital trade rules under the WTO Electronic Commerce Work Program stalled in 2017.31 Given the lack of progress on multilateral rules, some have suggested that the WTO should identify best practices or guidelines for digital trade rules that could lay the foundation for a future multilateral WTO agreement.

WTO Plurilateral Effort

Over 80 countries, including the United States, are participating in ongoing WTO e-commerce negotiations aiming to establish a global framework and obligations to enable digital trade in a nondiscriminatory and less trade restrictive manner. Many stakeholders express hope that the negotiations will result in obligations, standards, and best practices regarding personal data protection and cross-border data flows. One notably large source and destination for digital trade, India, stated it will not join, preferring to maintain its flexibility to favor domestic firms, limit foreign market access, or raise revenue in the future.32

Multiple parties have submitted proposals outlining their positions and desired scope for the negotiations that reflect differences in their domestic policies and priorities (see "Foreign Government Policies").33 Proposals by the United States, China, and EU illustrate areas of potential overlap and disagreement.

- The U.S. proposal includes provisions to protect cross-border data flow and prevent data localization mandates. It also includes provisions from USMCA requiring parties to adopt or maintain a legal framework to protect personal information and encouraging the development of interoperability mechanisms.34

- China's proposal states that data flows and data storage should be subjects for exploratory discussions rather than solid commitments.35 Regarding privacy, China states that the parties "should adopt measures that they consider appropriate and necessary to protect the personal information of electronic commerce users," providing flexibility to governments but also not defining any principles or standards.36 By excluding hard obligations, China's proposal would essentially allow the country to maintain its highly restrictive internet regime.

- The EU proposes allowing cross-border data flows and prohibiting localization requirements, while allowing members to "adopt and maintain the safeguards they deem appropriate to ensure the protection of personal data and privacy, including through the adoption and application of rules for the cross-border transfer of personal data."37 Some analysts see the exception as nullifying the commitment to cross-border data flows.

The U.S. Trade Representative's (USTR's) statement emphasized the need for a high-standard agreement that includes enforceable obligations.38 Although some experts note that harmonization or mutual recognition is unlikely given divergent legal systems, privacy regimes, and norms of the parties, a common system of rules to allow for cross-border data flows while ensuring privacy protection is reportedly under discussion.39

International Guidelines and Best Practices

Personal privacy has received increasing focus with the growth of digital trade encouraging global cooperation. The United States has contributed to developing international guidelines or principles related to privacy and cross-border data flows, although none are legally binding.

OECD

The OECD 1980 Privacy Guidelines established the first international set of privacy principles emphasizing data protection as a condition for the free flow of personal data across borders.40 These OECD guidelines were intended to assist countries with drawing up national data privacy policies.

The guidelines were updated in 2013, focusing on national level implementation based on a risk management approach and improving interoperability between national privacy strategies.41 The updated guidelines identify specific principles for countries to take into account in establishing national policies. In 2019, members began the process to again review and update the guidelines.

|

OECD Privacy Guidelines:

|

G-20

Building on the OECD principles and prior G-20 work, the 2018 G-20 Digital Economy Ministerial Declaration identified principles to "facilitate an inclusive and whole-of-government approach to the use of information and communication technology (ICT) and assist governments in reshaping their capacities and strategies, while respecting the applicable frameworks of different countries, including with regards to privacy and data protection."42

Japan focused on data governance during its host year in 2019. The Osaka Leader's Declaration recognized the importance of cross-border data flows, but also the challenges related to data protection and privacy.43 To achieve "data free flow with trust" and strengthen the digital economy, the parties support interoperability between different frameworks.

APEC

APEC is a regional forum for economic cooperation whose initiatives on privacy and cross-border data flows have influenced members' domestic policies. APEC's 21 members, including the United States, agreed to the 2005 APEC Privacy Framework, based on the OECD guidelines. The framework identifies a set of principles and implementation guidelines to provide members with a flexible approach to regulate privacy at a national level.44 Once the OECD publishes updated guidelines, APEC members may revise the framework and principles to reflect the updated guidelines.

|

APEC Privacy Framework Principles

|

APEC CBPR

The APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR), endorsed by APEC Leaders in 2011, is a privacy code of conduct, based on the 2005 framework. The CBPR system establishes a set of principles for governments and businesses to follow to protect personal data and allow for cross-border data flows between CBPR members.45 They aim to balance information privacy with business needs and commercial interests, and facilitate digital trade to spur economic growth in the region.

Rather than creating a new set of international regulations, the APEC framework and CBPR system identify best practices that each APEC member can tailor to its domestic legal system and allow for interoperability between countries. The scope and implementation mechanisms under CBPR can vary according to each member country's laws and regulations, providing flexibility for governments to design national privacy approaches. To become a member of the CBPR, a government must

- 1. Be a member of APEC;

- 2. Establish a regulator with authority to sign the Cross-Border Privacy Enforcement Arrangement (CPEA);

- 3. Map national laws to the published APEC guidelines, which set baseline standards; and

- 4. Establish an accountability agent empowered to audit and review a company's practices, and enforce privacy rules and laws.

If a government joins the CBPR system, every domestic organization is not required to also join; however, becoming a member of CBPR may benefit an organization engaged in international trade by indicating to customers and partners that the organization values and protects data privacy. With certified enrollment in CBPR, organizations can transfer personal information between participating economies (e.g., Mexico to Singapore) and be assured of compliance with the legal regimes in both places. To become a CBPR member, an individual organization must develop and implement data privacy policies consistent with the APEC Privacy Framework and complete a questionnaire. The third party accountability agent is responsible for assessing an organization's application, ongoing monitoring of compliance, investigating any complaints, and taking enforcement actions as necessary.46 Some stakeholders voice concern that the membership process is burdensome and costly, deterring many small and medium sized businesses.

Domestic enforcement authorities in each member country serve as a backstop for dispute resolution if an accountability agent cannot resolve a particular issue. All CBPR member governments must join the CPEA to ensure cooperation and collaboration between the designated national enforcement authorities.

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is the regulator and enforcement authority. U.S. accountability agents currently include TRUSTe and Schellman & Company, LLC.47

Expanding CBPR Beyond APEC

The CBPR grows in significance as the number of participating economies and organizations increases. The U.S. ambassador to APEC aims to have "as many APEC economies as possible as soon as possible to join the system."48 Currently, the United States, Japan, Mexico, Canada, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Australia are CBPR members; the Philippines is in the process of joining. Russia, on the other hand, stated it has no plans to join. Although APEC initiatives are regionally focused, they can provide a basis to scale up to larger global efforts because they reflect economies at different stages of development and include industry participation. Due to its voluntary nature, APEC has served as a testbed for identifying best practices, standards, and principles and for creating frameworks that can lead to binding commitments in plurilateral or larger multilateral agreements (see "Data Flows and Privacy in U.S. Trade Agreements").

Expanding CBPR to countries outside of APEC could represent the next step toward consistent international rules and disciplines on data flows and privacy. Similarly, APEC CBPR could serve as a model for additional interoperability schemes between sets of developed and developing countries with shared regional interests or cultural norms. If other groups of countries create their own framework for interoperability, there is potential for broader interoperability between the varied systems.

Foreign Government Policies

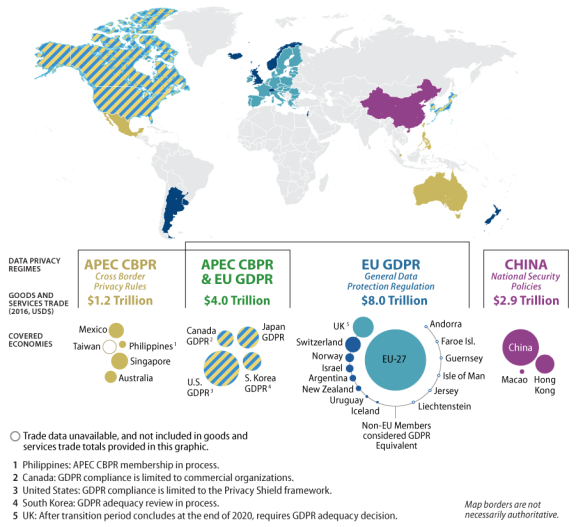

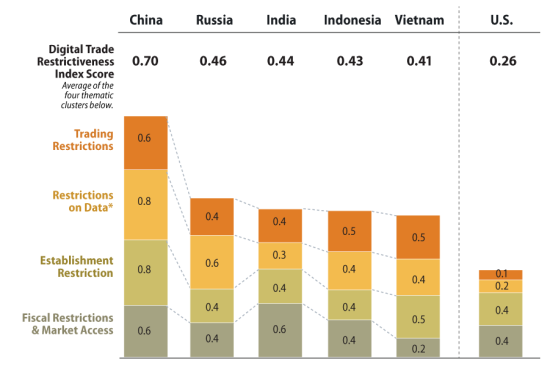

Countries vary in their privacy policies and laws, reflecting differing priorities, cultures, and legal structures. According to one index, China is the most restrictive digital trade country among 64 countries surveyed, followed by Russia, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam (see Figure 1).49 Digital restrictions in the index cover policies such as data location requirements and limitations on cross-border data flows, financial investments, or e-commerce. The United States ranks 22 in this index, less restrictive than Brazil or France but more restrictive than Canada or Australia.50 The relatively high U.S. score largely reflects financial sector restrictions.

The "restrictions on data" category covers data policies such as privacy and security measures; this category is included in the composite index. Looking specifically at the 64 countries' data policies, Russia is the most restrictive country, followed by Turkey and China because of data flow restrictions.51 Russia's policies include data localization, retention, and transfer requirements, among others. Turkey's comprehensive Data Protection Law also establishes requirements in these areas.52 In contrast, the United States ranks 50 for data policy restrictions.

Two of the top U.S. trading partners (the EU and China) have established their data policies from different perspectives. The EU's policies are driven by privacy concerns; China's policies are based on security justifications. Both are setting examples that other countries, especially those with (or seeking) closer trading ties to China or the EU, are emulating; thus, these policies have affected U.S. firms seeking to do business in those other countries as well.

|

|

Source: ECIPE, Digital Trade Restrictiveness Index, April 2018. Notes: *Includes data policies. All index scores reflect rounding. |

EU: Privacy First

U.S.-EU Privacy Shield

The EU considers the privacy of communications and the protection of personal data to be fundamental human rights, which are codified in EU law.53 Differences between the United States and EU in their approaches to data protection and data privacy laws have long been sticking points in U.S.-EU economic and security relations. In 2016, the EU and United States negotiated the U.S.-EU Privacy Shield to allow for the transatlantic transfer of personal data by certified organizations. The bilateral agreement established a voluntary program with commitments and obligations for companies, limitations on law enforcement access, and transparency requirements. U.S. companies that participate in the program must still comply with all of the obligations under EU law (see below) if they process personal data of EU persons. The Privacy Shield is overseen and enforced by EU and U.S. agencies, including the Department of Commerce and the FTC, and is reviewed by both parties annually.

As noted earlier, the United Kingdom (UK) withdrew from the EU on January 31, 2020. After the UK's transition period concludes at the end of 2020, the United States and UK may implement an agreement similar to the Privacy Shield to allow for cross-border data flows of personal data between the two countries.

EU GDPR

The EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), effective May 2018, establishes rules for EU members, with extraterritorial implications.54 The GDPR is a comprehensive data privacy regime that builds on previous EU data protection rules. It grants new rights to individuals to control personal data and creates specific new data protection requirements.

|

EU's GDPR New Individual Rights:

|

The GDPR applies to (1) all businesses and organizations with an EU establishment that process (i.e., perform operations on) personal data of individuals in the EU, regardless of where the actual processing of the data takes place; and (2) entities outside the EU that offer goods or services (for payment or for free) to individuals in the EU or monitor the behavior of individuals in the EU. While the GDPR is directly applicable at the EU member state level, individual countries are responsible for establishing some national-level rules and policies as well as enforcement authorities, and some are still in the process of doing so. As a result, some U.S. stakeholders have voiced concerns about a lack of clarity and inadequate country compliance guidelines.

Many U.S. firms doing business in the EU have made changes to comply with the GDPR, such as revising and clarifying user terms of agreement and asking for explicit consent. For some U.S. companies, it may be easier and cheaper to apply GDPR protections to all users worldwide rather than to maintain different policies for different users. Large firms may have the resources to hire consultants and lawyers to guide implementation and compliance; it may be harder and costlier for small and mid-sized enterprises to comply, possibly deterring them from entering the EU market and creating a de facto trade barrier.

Since the GDPR went into effect on May 25, 2018, some U.S. businesses, including some newspaper websites and digital advertising firms, have opted to exit the EU market given the complexities of complying with the GDPR and the threat of potential enforcement actions.55 European Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) have received a range of GDPR complaints and initiated several GDPR enforcement actions. In January 2019, the French DPA issued the largest penalty to date for a data privacy breach. The agency imposed a €50 million (approximately $57 million) fine on Google for the "lack of transparency" regarding how the search engine processes user data.56 The Irish DPA is responsible for enforcement of the many multinational firms whose European headquarters are in Ireland, including Facebook and Google. In February 2020, the head of the Irish DPA stated that "six statutory inquiries were opened in relation to multinational technology companies' compliance with the GDPR, bringing the total number of cross-border inquiries to 21."57

Exporting Personal Data Under EU GDPR

Under the GDPR, a few options exist to transfer personal data in or out of the EU and ensure that privacy is maintained.

- 1. An organization may use specific Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) or Model Contracts approved by the EU;

- 2. An organization may comply with domestic privacy regimes of a country that has obtained a mutual adequacy decision from the EU, which means that the EU has deemed that a country's laws and regulations provide an adequate level of data protection; currently, fewer than 15 jurisdictions are deemed adequate by the EU;58 or

- 3. A U.S.-based organization may enroll in the bilateral U.S.-EU Privacy Shield program for transatlantic transfer of personal data.59

The GDPR legal text seems to envision a fourth way, such as a certification scheme to transfer data, that the EU has yet to elaborate. A certification option(s) could create a less burdensome means of compliance for U.S. and other non-EU organizations to transfer personal data to or from the EU in the future. This could be an opportunity for the United States to work with the EU on creating a common system, perhaps even setting a global standard.

Expanding GDPR Beyond the EU

Some experts contend that the GDPR may effectively set new global data privacy standards, since many companies and organizations are striving for GDPR compliance to avoid being shut out of the EU market, fined, or otherwise penalized, or to be ready in case other countries introduce rules that imitate the GDPR.60

The EU is actively promoting the GDPR and some countries, such as Argentina, are imitating all or parts of the GDPR in their own privacy regulatory and legislative efforts or as part of broader trade negotiations with the EU.61 In general, the EU does not include cross-border data flows or privacy in free trade agreements. However, alongside trade negotiations with Japan, the EU and Japan in 2018 agreed to recognize each other's data protection systems as "equivalent," allowing for the free flow of data between the EU and Japan and serving as a first step in adopting an adequacy decision (the EU officially adopted its adequacy decision on Japan in January 2019).62 Under the agreement, Japan committed to implementing additional measures to address the handling of the personal data of EU persons on top of Japan's own privacy regime.63

In advance of leaving the EU, the UK passed its Data Protection Act 2018 to align with GDPR.64 The UK would need an adequacy determination by the EU in order to maintain cross-border data flows with the EU at the end of the transition period. The UK's adequacy decision is not guaranteed and some European officials have raised concerns about some UK data protection policies; such uncertainty has, in turn, alarmed some UK and U.S. businesses that rely on sending data between UK and EU locations.65 Google, for example, opted to move its British users' accounts from storage in Ireland, which remains in the EU, to California (which has legal ownership of all Google EU data) in case the UK departs from GDPR in the future.66

GDPR represents one part of the EU's digital data strategy. The European Commission is in the process of building regulatory frameworks on data sharing and artificial intelligence, among other topics.67 As with GDPR, the EU seeks to be a global leader in how governments regulate data. Some U.S. observers raise concerns that without a federal data policy, the United States may be missing an opportunity to set global precedents and maintain U.S. digital competitiveness.

China: Security First

China's trade and internet policies reflect state direction and industrial policy, limiting the free flow of information and individual privacy. For example, the requirement for all internet traffic to pass through a national firewall can impede the cross-border transmission of data.68 China's 2015 counterterrorism law requires telecommunications operators and internet service providers to provide assistance to the government, which could include sharing individuals' data. Citing national security concerns, China's Internet Sovereignty policies, Cybersecurity Law, and Personal Information Security Specification impose strict requirements on companies, such as storing data domestically; limiting the ability to access, use, or transfer data internationally; and mandating security assessments that provide Chinese authorities access to proprietary information.

In 2014, China announced a new social credit system, a centralized big-data-enabled system for monitoring and shaping businesses' and citizens' behavior that serves as a self-enforcing regulatory mechanism. According to the government, China aims to make individuals more "sincere" and "trustworthy," while obtaining reliable data on the creditworthiness of businesses and individuals. An individual's score would determine the level of government services and opportunities he or she could receive.69

China seeks to have all its citizens subject to the social credit system by 2020, forcing some U.S. businesses who do business in China, such as airlines, to participate.70 As of 2018, multiple government agencies and financial institutions contribute data to the platform. Pilot projects are underway in some provinces to apply various rewards and penalties in response to data collected. The lack of control an individual may have and the exposure of what some consider private data is controversial among observers in and out of China.

Some countries, such as Vietnam, are following China's approach in creating cybersecurity policies that limit data flows and require local data storage and possible access by government authorities.71 Some U.S. firms and other multinational companies are considering exiting the Vietnamese market rather than complying, while some analysts suggest that Vietnam's law may not be in compliance with its recent commitments in trade agreements (see below).72 India has also cited security as the rationale for its draft Personal Data Protection Bill, which would establish broad data localization requirements and limit cross-border transfer of some data.73 Unlike the EU, these countries do not specify mechanisms to allow for cross-border data flows. U.S. officials have raised concerns with both Vietnam's and India's localization requirements.74

Defining the U.S. Approach

The EU's emphasis on privacy protection and China's focus on national security (and the countries that emulate their policies) have led to data-focused policies that restrict international trade and commerce to varying degrees. The United States has traditionally sought a balanced approach between trade, privacy, and security.

U.S. data flow policy priorities are articulated in USTR's Digital 2 Dozen report, first developed under the Obama Administration,75 and the Trump White House's 2017 National Security Strategy.76 Both Administrations emphasize the need for protection of privacy, the free flow of data across borders, and an interoperable internet. These documents establish the U.S. position that the free flow of data is consistent with protecting privacy. Recent free trade agreements translate the U.S. position into binding international commitments.

The United States has taken a data-specific approach to regulating data privacy, with laws protecting specific information, such as healthcare or financial data. The FTC enforces consumer protection laws and requires that consumers be notified of and consent to how their data will be used, but the FTC does not have the mandate or resources to enforce broad online privacy protections. There is growing interest among some Members of Congress and in the Administration for a more holistic U.S. data privacy policy.

Data Flows and Privacy in U.S. Trade Agreements

The United States has played an important role in international discussions on privacy and data flows, such as in the OECD, G-20, and APEC, and has included provisions on these subjects in recent free trade agreements.

Congress noted the importance of digital trade and the internet as a trading platform in setting the current U.S. trade negotiating objectives in the June 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation (P.L. 114-26). TPA includes a specific principal U.S. trade negotiating objective on "digital trade in goods and services and cross-border data flows." According to TPA, a trade agreement should ensure that governments "refrain from implementing trade-related measures that impede digital trade in goods and services, restrict cross-border data flows, or require local storage or processing of data."77 However, TPA also recognizes that sometimes measures are necessary to achieve legitimate policy objectives and aims for such regulations to be the least trade restrictive, nondiscriminatory, and transparent.

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‐Pacific Partnership (CPTPP/TPP-11). The CPTPP entered into force at the end of 2018 among 11 Asia-Pacific countries.78 The CPTPP is based on the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement negotiated by the Obama Administration and from which President Trump withdrew the United States in January 2017.

The electronic commerce chapter in TPP, left unchanged in CPTPP, includes provisions on cross-border data flows and personal information protection.79 The text specifically states that the parties "shall allow the cross-border transfer of information."80 The agreement allows restrictive measures for legitimate public policy purposes if they are not discriminatory or disguised trade barriers. The agreement also prohibits localization requirements for computing facilities, with similar exceptions.

On privacy, the CPTPP requires parties to have a legal framework in place to protect personal information and to have consumer protection laws that cover online commerce. It encourages interoperability between data privacy regimes and encourages cooperation between consumer protection authorities.

Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA). Although the United States is not a party to DEPA, the agreement is notable because it builds on the CPTPP. Three CPTPP parties, Singapore, New Zealand and Chile, concluded the DEPA in January 2020, but it is not yet in force.81 The agreement includes a series of modules covering measures that affect the digital economy. Module 4 on Data Issues includes binding provisions on personal data protection and cross-border data flows that build on the CPTPP. In addition to the CPTPP obligations, for example, DEPA encourages the adoption of data protection trustmarks for businesses to verify conformance with privacy standards. The agreement is an open plurilateral one that allows other countries to join the agreement as a whole, select specific modules to join, or replicate the modules in other trade agreements.82 New Zealand is to host APEC in 2021, providing the country an opportunity to promote the new agreement.

|

USMCA Key Principles for Personal Information Protection

|

United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The USMCA revises, updates and replaces the trilateral North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and reflects the U.S. approach to data protection and cross border data flows.

The USMCA chapter 19 on digital trade includes articles on consumer protection, personal information protection, cross-border transfer of information by electronic means, and cybersecurity, among other topics.83 Building on principles in the TPP, the agreement seeks to balance the legitimate objectives by requiring parties to:

- have a legal framework to protect personal information,

- have consumer protection laws for online commercial activities, and

- not prohibit or restrict cross-border transfer of information.

While the agreement does not prescribe specific rules or measures that a party must take to protect privacy, it goes further than the TPP (or CPTPP) provisions and provides guidance to inform a country's privacy regime. In particular, the USMCA explicitly refers to the APEC Privacy Framework and OECD Guidelines as relevant and identifies key principles.

In general, the USMCA requires that parties not restrict cross-border data flows. Governments are allowed to do so to achieve a legitimate public policy objective (e.g., privacy, national security), provided the measure is not arbitrary, discriminatory, a disguised trade barrier, or greater than necessary to achieve the particular objective. In this way, the parties seek to balance the free flow of data for commerce and communication with protecting privacy and security. The agreement specifically states that the parties may take different legal approaches to protect personal data and also recognizes APEC's CBPR as a "valid mechanism to facilitate cross-border information transfer while protecting personal information."84

The agreement aims to increase cooperation between the United States, Mexico, and Canada on a number of digital trade issues, including exchanging information on personal information protection and enforcement experiences; strengthening collaboration on cybersecurity issues; and promoting the APEC CBPR and global interoperability of national privacy regimes. The governments also commit to encourage private-sector self-regulation models and promote cooperation to enforce privacy laws. While the agreement is among three parties, the provisions are written broadly to encompass global efforts. Some stakeholders look at USMCA as the basis for potential future trade agreements (such as with the UK or the EU).85 Cross-border data flows will likely be a key issue in future U.S.-EU trade negotiations.

U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement. The U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, signed on October 7, 2019, covers rules on digital aspects of international commerce and parallels the USMCA. Considered an executive agreement, it took effect on January 1, 2020, without formal action by Congress.86 Like USMCA, the agreement requires that the parties have a legal framework to protect personal information, have consumer protection laws for online commercial activities, and not prohibit or restrict cross-border transfer of information. The agreement promotes interoperability between privacy regimes, but does not refer to specific guidelines.

U.S. Federal Data Privacy Policy Efforts

The United States has articulated a clear position on data privacy in trade agreements; however, there is no single U.S. data privacy policy. The Trump Administration is seeking to define an overarching U.S. approach on data privacy.87 The Trump Administration's ongoing three-track process is being managed by the Department of Commerce (Commerce) in consultation with the White House. Different bureaus in Commerce are tasked with different aspects of the process, as follows.

- 1. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released the first version of its Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy through Enterprise Risk Management (Privacy Framework) on January 16, 2020.88 Similar to its cybersecurity framework, the framework is a voluntary tool for organizations to adopt to identify, assess, manage, and communicate about privacy risks, whether within an organization or with customers or regulators.89 By classifying specific privacy outcomes and potential approaches, the framework aims to enable organizations to create and adapt privacy strategies, innovate, and manage privacy risks within diverse regulatory environments. Through a risk and outcome-based approach, NIST intends the tool to be flexible and useful for organizations of all sizes and sectors. The framework does not define privacy, but provides common terminology for communication about data privacy risks, events or activities, and processes. U.S. officials can present the NIST tool internationally as a best practice similar to the cybersecurity framework. The privacy framework was created after extensive stakeholder consultation and is a living document as NIST continues to gather input and further develop the framework.

- 2. The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) is developing a set of privacy principles to guide a domestic legal and policy approach. The NITA sought public comment on a proposed set of "user-centric privacy outcomes" and a set of high-level goals.90

- 3. The International Trade Administration (ITA) engages with foreign governments and international organizations such as APEC. ITA is focusing on the international interoperability aspects of potential U.S. privacy policy. ITA's role is to ensure that the NIST and NTIA approaches are consistent with U.S. international policy objectives, including TPA, and principles, such as the OECD framework and APEC CBPRs.

Unlike the EU or China, the Commerce initiatives create a voluntary privacy framework and principles to enable communication and best practices but not enforceable rules. The emerging Commerce tools are intended to work in different regulatory contexts, and are not meant to be a substitute for potential federal (or state) legislation or rule-making. Some observers question whether the Commerce approach is sufficient to result in strong privacy protections if it is not backed up by congressional action and federal legislation.91

Some suggest that Congress could lead a whole-of-government approach through new federal legislation. Some stakeholders, including many U.S. businesses who operate globally, believe a common national standard on privacy would strengthen the U.S. position in international forums and provide an opportunity for clear U.S. leadership on the issue.

In the 115th Congress, then-House Committee on Energy and Commerce Ranking Member Frank Pallone, Jr. requested that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) examine issues related to federal oversight of internet privacy.92 The January 2019 GAO report concluded that now is "an appropriate time for Congress to consider comprehensive Internet privacy."93 GAO stated that "Congress should consider developing comprehensive legislation on Internet privacy that would enhance consumer protections and provide flexibility to address a rapidly evolving Internet environment. Issues that should be considered include what authorities agencies should have in order to oversee Internet privacy, including appropriate rulemaking authority."94

|

U.S. State-Level Privacy Policies Some U.S. states are advancing privacy rules in the absence of a coherent federal privacy policy. In June 2018, California passed the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, a broad digital privacy law that includes some similar consumer rights as in the EU GDPR, including clear and informed consent, the ability to opt out of data sharing, and the ability to access and correct personal information.95 California's law contains a broader definition of "personal data" than the GDPR, covers information pertaining to households and devices, and has other distinctions. California's law entered into effect in 2020.96 California's Attorney General continues to release new rules to clarify the law and amendments for further changes have been introduced.97 U.S. companies voice concern that the California law is leading other states to pass their own laws, creating a patchwork of diverse state requirements and enforcement authorities. For example, Washington state is considering a bill that has many similarities with California's.98 Differing state privacy policies and rules could increase compliance costs for organizations that function in multiple states and may impede interstate commerce, as a company based in one state may decline to serve a customer across state lines due to the complexity of complying with different or conflicting data requirements. Some companies are using firewalls to build "digital borders," selecting where to operate and who to serve. Some businesses are seeking federal privacy legislation to harmonize state rules and preempt such problems. On the other hand, some stakeholders, such as states' rights and privacy advocates, seek to limit federal level involvement. One coalition of consumer advocate organizations seeks to expand the California law further and supports state-level implementation and enforcement.99 |

Stakeholder Perspectives

Recognizing the importance of protecting open data flows amid growing concerns about online privacy, some stakeholders seek to influence U.S. policies on these issues. The Global Data Alliance, a cross-industry coalition of multinational companies, was formed specifically to advocate for "policies that help instill trust in the digital economy while safeguarding the ability to transfer data across borders and refraining from imposing data localization requirements that restrict trade."100 Its members include a variety of sectors, including financial services, airlines, entertainment, and consumer goods, to demonstrate the foundational importance of cross-border data flows to U.S. firms.

In addition to providing input to NTIA and NIST processes, multiple U.S. businesses and organizations issued their own sets of principles or guidelines, some referencing the EU GDPR. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has also published model privacy legislation for Congress to consider.101

Though they vary in emphasis, these proposals share common themes:102

- transparency on what data is being collected and how it is being used;

- user control, including the ability to opt out of sharing at least some information and to access and correct personal data collected;

- data security measures, like data breach notification requirements; and

- enforcement by the FTC. FTC commissioners also voiced support for the agency as the appropriate federal enforcer for consumer privacy.103

Industry groups' positions also differ in some areas, such as whether, or to what extent, to include certain aspects included in the GDPR, such as the right to deletion (so-called "right to be forgotten"), requirements for data minimization, or extraterritorial reach. There is not consensus on whether the FTC should be given rule-making authority or additional resources, the enforcement role of states, or if an independent data protection commission is needed similar to EU DPAs.

Consistent with U.S. trade policy, industry groups generally point out the need to be flexible, encourage private-sector innovation, establish sector- and technology-neutral rules, create international interoperability between privacy regimes, and facilitate cross-border data flows. Private-sector stakeholders generally want to avoid what they regard as overregulation or high compliance burdens. These groups emphasize risk management and a harm-based approach, which they state keeps an organization's costs proportional to the consumer harm prevented. In general, industry seeks a federal standard to preempt a patchwork of differing state laws and requirements (see text box) and to provide a U.S. standard to promote internationally (see below). Despite general alignment across U.S. industry, there are points of disagreement when it comes to technical and legal language for implementation, often driven by how different sectors collect or use data (e.g., business-to-business software vendors or consumer platforms).

In addition, some consumer advocates point to a need for baseline obligations to protect against discrimination, disinformation, or other harm. In general, consumer advocates believe that any comprehensive federal privacy policy should complement, and not supplant, sector-specific privacy legislation or state-level legislation.

The various bills introduced illustrate key points of contention such as federal preemption and enforcement where Members would need to identify a compromise or consensus solution to move forward. How any U.S. legislation defines individual rights and specific legal terms (e.g., de-identified data, nonsensitive data) would not only shape U.S. domestic implementation but also the U.S. position in any international discussions.

Shaping a Global Approach

Finding a global consensus on how to balance open data flows and privacy protection may be key to maintaining trust in the digital environment and advancing international trade. One study found that over 120 countries have laws related to personal data protection.104 Divergent national privacy approaches raise the costs of doing business and make it harder for governments to collaborate and share data, whether for scientific research, defense, or law enforcement.

A system for global interoperability in a least trade-restrictive and nondiscriminatory way between different national systems could help minimize costs and allow entities in different jurisdictions with varying online privacy regimes to share data via cross-border data flows. Such a system could help avoid fragmentation of the internet among European, Chinese, and American spheres, a danger that some analysts have warned against.105 For example, Figure 2 suggests the potential of an interoperability system that allows data to flow freely between GDPR- and CBPR-certified economies.

The OECD guidelines, G-20 principles, APEC CBPR, CPTPP, and FTA provisions such as those in the USMCA demonstrate an evolving understanding on how to balance cross-border data flows, security, and privacy, to create interoperable policies that can be tailored by countries and avoid fragmentation or the potential exclusion of other countries or regulatory systems. The various trade agreements and initiatives with differing sets of parties may ultimately pave the way for a broader multilateral understanding and eventually lead to more enforceable binding commitments founded on the key WTO principles of nondiscrimination, least trade restrictiveness, and transparency. The ongoing WTO plurilateral negotiations provide an opportunity to achieve greater progress toward these goals.

Issues for Congress

Future U.S. Trade Negotiations and Agreements

Congress may consider the trade-related aspects of data flows in trade agreements, including through oversight over ongoing, and future, WTO and bilateral trade negotiations, such as with the UK or EU. Issues include whether the agreements make progress in meeting TPA's related trade negotiating objectives and if the provisions strike the appropriate balance among public policy objectives. TPA is authorized through July 1, 2021, providing Congress an opportunity to examine the current objectives and determine if they should be revised to specifically address pursuing a global approach to cross-border data flows.

Congress may consider whether the United States should seek additional narrow bilateral digital agreements with certain trading partners, similar to the U.S.-Japan agreement. On the one hand, such agreements could lock in U.S. digital norms in other parts of the globe, provide certainty to U.S. exporters, and strengthen the U.S. position in international trade negotiations and standards discussions. On the other hand, executive agreements like the U.S.-Japan digital agreement do not provide a role for congressional formal consideration.

Global Approach

Congress may further consider how best to achieve broader consensus on data flows and privacy at the global level. Congress could, for example, conduct additional oversight of current best practice approaches (e.g., OECD, APEC) or ongoing negotiations in the WTO on e-commerce to create rules through plurilateral or multilateral agreements. Congress may consider endorsing certain of these efforts to influence international discussions and the engagement of other countries. Congress may want to examine the potential challenges and implications of building a system of interoperability between APEC CBPR and the EU GDPR.

Related issues are the extent to which the EU is establishing its system as a potential de facto global approach through its trade agreements and other mechanisms, and how U.S. and other trade agreements may ultimately provide approaches that could be adopted more globally.

Impact on U.S. Trade

Congress may seek to better understand the economic impact of data flows and privacy regimes in other countries related to U.S. access to other markets and the extent to which barriers are being put in place that may discriminate against U.S. exporters. Congress may examine the lack of reciprocal treatment and limits on U.S. firms' access to some foreign markets.

Congress may consider the implications of not having a comprehensive national data privacy policy. Will the EU GDPR and China cybersecurity policies become the global norms that other countries follow in the absence of a clear U.S. alternative? Some have suggested that the EU could grant adequacy for cross-border data flows at a state-level for individual U.S. states that implement data protection laws (e.g., California).106 Would such a move result in further fragmentation in the United States and create trade barriers between states or present a challenge to Congress's authority to regulate foreign commerce?

Domestic Policy

Congress may enact comprehensive privacy legislation. In considering such action, Congress could investigate and conduct oversight of the Administration's ongoing privacy efforts, including requesting briefings and updates on the NTIA, NIST, and ITA initiatives to provide congressional feedback and direction and ensure they are aligned with U.S. trade objectives. Congress may also seek input from other federal agencies.

In deliberating a comprehensive U.S. policy on personal data privacy, Congress may review the GAO report's findings and conclusions. Congress may also weigh several factors, including:

- How can U.S. trade and domestic policy achieve the appropriate balance to encourage cross-border commerce, economic growth, and innovation, while safeguarding individual privacy and national security?

- How would a new privacy regime affect U.S. consumers and businesses, including large multinationals who must comply with different national and U.S. state privacy regimes and small- and medium-sized enterprises with limited resources and technology expertise? Do U.S. agencies have the needed tools to accurately assess the size and scope of cross-border data flows to help analyze the economic impact of different privacy policies, or measure the costs of trade barriers?

- How should an evolving U.S. privacy regime align with U.S. trade policy objectives and evolving international standards, such as the OECD Guidelines for privacy and cybersecurity, and should U.S. policymakers prioritize interoperability with other international privacy frameworks to avoid further fragmentation of global markets and so-called balkanization of the internet?

- Given that data privacy and protection are foundational to many policy areas, including trade, how (or who) should the United States be represented in international discussions on these topics?

In addition, beyond the scope of this report, there are a host of other policy considerations not directly related to trade.