Overview

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) first declared Covid-19 a world health emergency in January 2020, the virus has been detected in over 150 countries and almost all U.S. states.1 The infection has sickened more than 200,000 people, with thousands of fatalities.

On March 11, the WHO announced that the outbreak was officially a pandemic, the highest level of health emergency.2 During that time, it has become clear that the outbreak is negatively impacting global economic growth.3 The virus is affecting a broad swath of economic activities, from tourism, medical supplies and other global value chains, consumer electronics, and financial markets to energy, food, and a range of social activities, to name a few. Without a clear understanding of when the health and economic effects may peak economic forecasts must necessarily be considered preliminary. Efforts to reduce social interaction to contain the spread of the virus are disrupting the daily lives of most Americans.

On March 2, 2020, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released its revised economic outlook and suggested that global economic growth could decline by 0.5% in 2020 to 2.4% if the economic effects of the virus peak in the first quarter of 20204 (see Table 1). If the effects of the virus do not peak in the first quarter, which now seems unlikely, the OECD estimates that global economic growth in 2020 could be reduced by half, or 1.5%.

Concerns over economic and financial risks have pushed investors to search out safe-haven investments such as the benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year security, which experienced a historic drop in yield to below 1% on March 3, 2020 (the price and yield of a bond are inversely related).5 The yield dropped again to historic levels on March 6, 2020, and March 9, 2020, as investors moved out of stocks and into bonds due to concerns over declines in major stock indices and expectations that the Federal Reserve would lower interest rates for a second time in March 2020.6 In overnight trading on March 8, 2020, and again on March 11, 2020, March 13, 2020, and March 15, 2020, U.S. stock market indices moved sharply, triggering automatic circuit breakers designed to halt trading if the indices rise or fall by more than 5% when markets are closed.7 Financial markets from the United States to Asia and Europe are volatile as investors are concerned that the virus is creating a global issue with few metrics to indicate how prolonged and expansive the economic effects may be.8 Similar to the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, central banks are finding themselves put in the position of being the lender of last resort. During the financial crisis, central banks intervened to restart credit and spending. In the current environment, however, central banks are attempting to address financial market volatility that reflects the underlying economic uncertainty caused by the viral outbreak. The virus is also affecting global politics as world leaders are cancelling international meetings9 and some nations reportedly are stoking conspiracy theories that shift blame to other countries.10

The challenge for policymakers is to implement targeted policies that address what are expected to be short-term problems without creating distortions in economies that can outlast the impact of the virus itself. Policymakers are being overwhelmed by the quickly changing nature of the crisis that has compounded a health issue with what could become a global trade and economic crisis whose potential effects on the global economy are rapidly growing. In addition, many policymakers are constrained in their response to the crisis, with little flexibility for monetary and fiscal support, given the broad-based synchronized slowdown in global economic growth, especially in manufacturing and trade, which had developed prior to the viral outbreak.

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

||||||||||

|

November |

Difference |

November |

Difference |

|||||||||

|

World |

2.9 |

2.4 |

-0.5 |

3.3 |

0.3 |

|||||||

|

G20 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

-0.5 |

3.5 |

0.2 |

|||||||

|

Australia |

1.7 |

1.8 |

-0.5 |

2.6 |

0.3 |

|||||||

|

Canada |

1.6 |

1.3 |

-0.3 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

|||||||

|

Euro area |

1.2 |

0.8 |

-0.3 |

1.2 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Germany |

0.6 |

0.3 |

-0.1 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

France |

1.3 |

0.9 |

-0.3 |

1.4 |

0.2 |

|||||||

|

Italy |

0.2 |

0.0 |

-0.4 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Japan |

0.7 |

0.2 |

-0.4 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Korea |

2.0 |

2.0 |

-0.3 |

2.3 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Mexico |

-0.1 |

0.7 |

-0.5 |

1.4 |

-0.2 |

|||||||

|

Turkey |

0.9 |

2.7 |

-0.3 |

3.3 |

0.1 |

|||||||

|

United Kingdom |

1.4 |

0.8 |

-0.2 |

0.8 |

-0.4 |

|||||||

|

United States |

2.3 |

1.9 |

-0.1 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

|||||||

|

Argentina |

-2.7 |

-2.0 |

-0.3 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Brazil |

1.1 |

1.7 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

China |

6.1 |

4.9 |

-0.8 |

6.4 |

0.9 |

|||||||

|

India |

4.9 |

5.1 |

-1.1 |

5.6 |

-0.8 |

|||||||

|

Indonesia |

5.0 |

4.8 |

-0.2 |

5.1 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Russia |

1.0 |

1.2 |

-0.4 |

1.3 |

-0.1 |

|||||||

|

Saudi Arabia |

0.0 |

1.4 |

0.0 |

1.9 |

0.5 |

|||||||

|

South Africa |

0.3 |

0.6 |

-0.6 |

1.0 |

-0.3 |

|||||||

Source: OECD Interim Economic Assessment: Coronavirus: The World Economy at Risk, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. March 2, 2020, p. 2.

|

Comparing the Current Crisis and the 2008 Crisis Sharp declines in the stock market and broader financial sector turbulence; interest rate cuts and large-scale Federal Reserve intervention; and discussions of massive government stimulus packages have led some observers to compare the current market reaction to that experienced a little over a decade ago. There are similarities and important differences between the current economic crisis and the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Foremost, the earlier crisis was rooted in structural weakness in the U.S. financial sector. Following the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble, it became impossible for firms to identify demand and hold inventories (across many sectors (construction, retail, etc). This led to massive oversupply and sharp retail losses which extended to other sectors of the U.S. economy and eventually the global economy. Moreover, financial markets across countries were linked together by credit default swaps. As the crisis unfolded, large numbers of banks and other financial institutions were negatively affected, raising questions about capital sufficiency and reserves. The crisis, then quickly engulfed credit-rating agencies, mortgage lending companies and the real estate industry broadly. Market resolution came gradually with a range of monetary and fiscal policy measures that were closely coordinated at the global level. These were focused on putting a floor under the falling markets, stabilizing banks, and shoring up investor confidence to get spending started again. Starting in September 2007, The Federal Reserve cut interest rates from over 5% in September 2007 to between 0 and 0.25% before the end of the 2008. Once interest rates approached zero, the Fed turned to other so-called "unconventional measures" including targeted assistance to financial institutions, including encouraging Congress to pass the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and the Term Asset Backed Security Loan Facility (TALF) to prevent the collapse of the financial sector and boost consumer spending. Other measures included forced bank capitalizations (or bank nationalizations in other countries), swap arrangements between the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank and smaller central banks, and so-called "quantitative easing" to boost the money supply. On a global level, the United States and other countries tripled the resources of the IMF (from $250 billion to $750 billion) and coordinated domestic stimulus efforts. Unlike the 2008 crisis, the current crisis began as a supply shock. As the global economy has become more interdependent in recent decades, most products are produced as part of a global value chain (GVC), where an item such as a car or mobile device consists of parts manufactured all over the world, and involving multiple border crossings before final assembly. The earliest implications of the current crisis came in January as plant closures in China and other parts of Asia led to interruptions in the supply chain and concerns about dwindling inventories. As the virus spread from Asia to Europe, the crisis switched from supply concerns to a broader demand crisis as the measures being introduced to contain the spread of the virus (social distancing, travel restrictions, cancelling sporting events, closing shops and restaurants, and mandatory quarantine measures) prevent most forms of economic activity from occurring. Thus, unlike the 2008 crisis response, which involved liquidity and solvency-related policy measures to get people spending again, the current crisis is related to the amount of operating capital in the economy. While larger firms may have sufficient capital to wait out a crisis, many aspects of the economy (such as restaurants or retail operations) operate on very tight margins and would likely not be able to pay employees after closures lasting more than a few days. Many people will also need to balance child care and work during quarantine or social distancing measures. During this type of crisis, while monetary policy measures play a part -- and the Federal Reserve has once again cut rates to near zero -- they cannot compensate for the physical interaction that the global economy is dependent upon. As a result, fiscal stimulus will likely play a relatively larger role in this crisis in order to prevent personal and corporate bankruptcies during the peak crisis period. Efforts to coordinate U.S. and foreign economic policy measures will also have an important role in mitigating the scale and length of any global economic downtown. |

Estimated Economic Effects

The economic situation remains highly fluid. Uncertainty about the length and depth of the virus-related economic effects are fueling perceptions of risk and volatility in financial markets and corporate decisionmaking. In addition, uncertainties concerning the virus and the effectiveness of public policies intended to curtail its spread are adding to market volatility.

The OECD also estimates that increased direct and indirect economic costs through global supply chains reduced demand for goods and services, and that declines in tourism and business travel mean that, "the adverse consequences of these developments for other countries (non-OECD) are significant."11 Global trade, measured by trade volumes, slowed in the last quarter of 2019 and was expected to decline further in 2020 as a result of weaker global economic activity associated with the viral outbreak, which is reducing economic activity in various sectors, including ports and the shipping industry.12

In addition, the OECD argues that China's emergence as a global economic actor marks a significant departure from previous global health episodes. China's growth in combination with globalization and the interconnected nature of economies through supply chains and foreign investment magnify the cost of containing the spread of the virus through quarantines and restrictions on labor mobility and travel.13 China's global economic role and globalization more broadly mean that trade is playing a role in spreading the economic effects of Covid-19 through three channels: directly through supply chains as reduced economic activity is spread from intermediate goods producers to finished goods producers; as a result of a drop in economic activity, which reduces demand for goods in general, including imports; and through reduced trade with commodity exporters that supply producers, which, in turn, reduces their imports and negatively affects trade and economic activity of exporters.

Initially, the economic effects of the virus were expected to be a short-term supply issue as factory output fell because workers were quarantined to reduce the spread of the virus through social interaction. The drop in economic activity, initially in China, created larger supply issues as firms experienced delays in supplies in intermediate and finished goods through supply chains. Concerns have grown, however, that the virus-related supply shock is creating a more prolonged demand shock as reduced activity by consumers and businesses lead to a lower rate of economic growth. As demand shocks unfold, businesses experience a decline in activity, reduced profits, and potentially escalating and binding credit and liquidity constraints. While manufacturing firms are experiencing supply shocks through their supply chains, reduced consumer activity through social distancing is affecting the services sector of the economy, which accounts for two-thirds of U.S. economic output. In this environment, manufacturing and service firms are hoarding cash, which affects market liquidity. In response central banks have taken measures to provide financial markets with liquidity.

If the economic effects persist, contagion issues can spread the economic effects widely and affect an ever-broadening group of firms and households. This potentially can increase liquidity constraints and credit market tightening in global financial markets as firms hoard cash, with negative fallout effects on economic growth. In some financial markets, fund managers have started selling government securities to increase their cash reserves, pushing down government bond prices. At the same time, financial markets are factoring in an increase in government bond issuance in the United States and Europe as government debt levels rise to meet spending obligations during an expected slowdown in economic activity and efforts to fight the effects of Covid-19. Unlike the 2008 financial crisis, reduced demand by consumers, labor market issues, and a reduced level of activity among businesses, rather than risky trading by global banks, has led to corporate credit issues. The market dynamics have led some observers to question if these events mark the beginning of a full-scale global financial crisis.14

Liquidity and credit market issues present policymakers with a different set of challenges than addressing supply-side constraints. As a result, the focus of government policy has expanded from a health issue to macroeconomic and financial market issues that are being addressed through a combination of monetary, fiscal, and other policies. Essentially, while businesses are attempting to address worker and output issues at the firm level, national leaders are attempting to implement fiscal policies to assist workers and businesses that are facing financial strains, and central bankers are adjusting monetary policies to address mounting credit market issues. So far, households have been affected primarily through a loss of income, compared with the 2008-2009 financial crisis in which households experienced a sudden and large loss in the value of their assets, largely through a decline in the market value of their primary residence.

In many cases, national fiscal policies that might be employed to address demand issues are already constrained by high government debt levels; similarly, recent monetary policies have generally been accommodative, which leaves central banks little room for additional cuts in interest rates. In addition, in the current environment, even traditional policy tools, such as monetary accommodation, apparently are not being processed by markets in a traditional manner, with equity market indices displaying heightened, rather than lower, levels of uncertainty following the Federal Reserve's cut in interest rates. Such volatility is adding to uncertainties about what governments can do to address weaknesses in the global economy.

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, the global economy was struggling to regain a broad-based recovery as a result of the lingering impact of growing trade protectionism, trade disputes among major trading partners, falling commodity and energy prices, and economic uncertainties in Europe over the impact of the UK withdrawal from the European Union. Individually, each of these issues presented a solvable challenge for the global economy. Collectively, however, the issues weakened the global economy and reduced the available policy flexibility of many countries, especially among the leading developed economies. In this environment, Covid-19 could have an outsized impact. While the level of economic effects will eventually become clearer, the response to the virus could have a significant and enduring impact on the way businesses organize their work forces, global supply chains, and how governments respond to a global health crisis.15

Policy Response

In response to growing concerns over the global economic impact of the virus, G-7 finance ministers and central bankers released a statement on March 3, 2020, indicating they will "use all appropriate policy tools" to sustain economic growth.16 The Finance Ministers also pledged fiscal support to ensure health systems could sustain efforts to fight the outbreak.17 Following the G-7 statement, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) lowered its federal funds rate by 50 basis points, or 0.5%, to a range of 1.0% to 1.25% due to concerns about the "evolving risks to economic activity of the coronavirus."18 At the time, the cut was the largest one-time reduction in the interest rate by the Fed since the financial crisis of 2008.

The United States

In a sign of growing concern over strains in financial markets, on March 12, 2020, the Federal Reserve announced it will supply liquidity to the financial system by providing $5 trillion through a series of funding operations that will add to current monthly funding operations targeted at increasing reserves in the banking system and reducing stress in short-term funding market and in trading U.S. Treasury securities. Corporate bond markets halted activity on March 11, 2020, as companies drew on revolving credit facilities from banks to ensure they had enough cash on hand to sustain their operations during a prolonged slump in economic activity and potential credit tightening by banks.

In addition, banks and financial institutions that deal in trading U.S. Treasury securities had begun to pull back from facilitating trades to protect themselves from market volatility, increasing costs to traders who profit from the difference between buying Treasury securities and then selling futures contracts.19 The Federal Reserve reportedly will provide $1 trillion in short-term lending to banks to sustain lending between banks, because credit markets had begun to freeze up. In addition, the Federal Reserve opened a financial crisis-era facility to acquire corporate bonds in the commercial paper (CP) market, which is used by firms to raise cash be selling short-term debt.20 Banks have become reluctant to acquire the securities over concerns that markets that trade in CP will be frozen.21 The Fed also indicated that it will provide a series of $500 billion injections of funds into the repo (repurchase) market, where investors borrow cash in exchange for high-quality collateral like Treasury securities.22

In an additional step, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 100 basis points (1.0%) on March 15, 2020, to a range of 0% to 0.25%, because it determined that "….The coronavirus outbreak has harmed communities and disrupted economic activity in many countries, including the United States. Global financial conditions have also been significantly affected.23" The Federal Reserve announced that it was providing an additional $700 billion in asset purchases (Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities), expanding repurchase operations, extending dollar swap lines with foreign banks (Canada, the UK, Japan and Europe, including the Swiss National Bank), and opened its discount window to commercial banks and urged banks to use their own capital and liquidity buffers to ease household and business lending. In its statement, the Federal Reserve announced that it was prepared to use its "full range of tools to support the flow of credit to households and businesses…." The coordinated central bank actions were intended to calm global financial markets after a week of greater than usual volatility. On March 17, 2020, the Federal Reserve opened a new financing facility for the 24 primary dealers in U.S. Treasury securities that allows them to borrow cash secured against some stocks, municipal debt and higher-rated corporate bonds.

In terms of a fiscal stimulus, the House passed H.R. 6074 on March 5, 2020, to appropriate $8.3 billion in emergency funding to support efforts to fight Covid-19; President Trump signed the measure on March 6, 2020. Other countries have indicated they will also provide assistance. Congress also is considering other possible measures, including contingency plans for agencies to implement offsite telework for employees, financial assistance to the shale oil industry, paid sick leave, a reduction in the payroll tax,24 and an extension of the tax filing deadline.25 On March 11, 2020, President Trump announced a restriction on all travel from Europe to the United States for 30 days, directed the Small Business Administration (SBA) to offer low-interest loans to small businesses, and directed the Treasury Department to defer tax payments penalty-free for affected businesses.26

On March 13, President Trump declared a state of emergency, freeing up disaster relief funding to assist state and local governments in addressing the effects of the virus. The President also announced additional testing for the virus, a website to help individuals identify symptoms of the virus, increased oil purchases for the Strategic Oil Reserve, and a waiver on interest payments on student loans.27 The White House and House Democrats announced they had reached agreement on a package of measures that is intended to provide tens of billions of dollars for paid sick leave, unemployment insurance, food stamps, and other measures.28

On March 17, 2020, President Trump announced that he intended to ask Congress for an additional $1.2 trillion in funds to support the economy.29 This amount reportedly would include loans to support cargo and passenger air carriers and loans and guarantees to other affected industries, loans to small businesses, and direct payments to individual taxpayers.30 For additional information about the impact of Covid-19 on the U.S. economy see CRS Insight IN11235, COVID-19: Potential Economic Effects.31

Europe

To date, European countries have not had the kind of synchronized policy response they developed during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. Instead, they have used a combination of tax holidays for businesses and extensions of certain payments and loan guarantees and subsidies for workers. The European Commission announced that it was relaxing rules on government debt to allow countries more flexibility in using fiscal policies. The European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it was ready to take "appropriate and targeted measures," if needed. With interest rates already low, however, it indicated that it could expand its program of providing loans to EU banks, or buying debt from EU firms, and possibly lowering its deposit rate further into negative territory in an attempt to shore up the Euro's exchange rate.32 ECB President-designate Christine Lagarde called on EU leaders to take more urgent action to avoid the spread of coronavirus triggering a serious economic slowdown. The European Commission indicated that it was creating a nearly $30 billion investment fund to address Covid-19 issues.33 On March 12, 2020, the ECB decided to: (1) expand its longer-term refinance operations (LTRO) to provide low-cost loans to Eurozone banks to increase bank liquidity; (2) extend targeted longer-term refinance operations (TLTRO) to provide loans at below-market rates to businesses, especially small and medium-sized businesses, directly affected by Covid-19; (3) provide an additional €120 billion (about $130 billion) for the Bank's asset purchase program to provide liquidity to firms.34 On March 13, 2020, financial market regulators in the UK, Italy, and Spain intervened in stock and bond markets to stabilize prices after historic swings in indexes on March 12, 2020.35 In addition, the ECB announced that it would do more to assist financial markets in distress, including altering self-imposed rules on purchases of sovereign debt.36 Germany's Economic Minister announced on March 13, 2020, that Germany would provide unlimited loans to businesses experiencing negative economic activity (initially providing $555 billion), tax breaks for businesses,37 and export credits and guarantees.38 Recent forecasts indicate that the economic effect of Covid-19 could push the Eurozone into an economic recession in 2020.39

The United Kingdom

The Bank of England announced on March 11, 2020, that it would adopt a package of four measures to deal with any economic disruptions associated with Covid-19. The measures include: an unscheduled cut in the benchmark interest rate by 50 basis points (0.5%) to a historic low of 0.25%; reintroduce the Term Funding scheme for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (TFSME) that provides banks with over $110 billion for loans at low interest rates; lower banks' countercyclical capital buffer to zero percent, which is estimated to support over $200 billion of bank lending to businesses; and freeze banks' dividend payments.40 The UK Chancellor of the Exchequer proposed a national budget on March 11, 2020, that includes nearly $35 billion in fiscal spending to counter adverse economic effects of the viral crisis and proposes that statutory sick leave be boosted by about $2.5 billion in funds to small and medium businesses to provide up to 14 days of sick leave for affected employees. Part of the fiscal spending package includes open-ended funding for the National Health Service (NHS), $6 billion in emergency funds to the NHS, $600 million hardship fund to assist vulnerable people, and tax cuts and tax holidays for small businesses in certain affected sectors.41

Japan

The Bank of Japan, with already-low interest rates, interjected $4.6 billion in liquidity into Japanese banks to provide short-term loans and twice that amount into exchange traded funds to aid Japanese businesses. The Japanese government also pledged to provide wage subsidies for parents forced to take time off due to school closures.42

China

According to a recent CRS In Focus, 43 China's economic growth could go negative in the first quarter of 2020 and fall below 5% for the year, with more serious effects if the outbreak continues. In early February, China's central bank pumped $57 billion into the banking system, capped banks' interest rates on loans for major firms, and extended deadlines for banks to curb shadow lending. The central bank has been setting the reference rate for China's currency stronger than its official close rate to keep it stable. On March 13, 2020, The People's Bank of China announced that it would provide $78.8 billion in funding, primarily to small businesses, by reducing bank's reserve requirements.44

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is providing funding to poor and emerging market economies that are short on financial resources.45 If the economic effects of the virus persist, countries may need to be proactive in coordinating fiscal and monetary policy responses, similar to actions taken by of the G-20 following the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

Multilateral Response

International Monetary Fund

The IMF announced that it is making available about $50 billion for the global crisis response.46 For low-income countries, the IMF is providing rapid-disbursing emergency financing of up to $10 billion (50% of quota of eligible members) that can be accessed without a full-fledged IMF program. Other IMF members can access emergency financing through the Fund's Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI). This facility could provide about $40 billion for emerging markets facing fiscal pressures from COVID-19. Separate from these resources, the IMF has a Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), which provides eligible countries with up-front grants for relief on IMF debt service falling due. The CCRT was used during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, but is now underfunded, according to IMF Managing Director Kristolina Georgieva with just over $200 million available against possible needs of over $1 billion. 47 On March 11, 2020, the United Kingdom announced that it will contribute £150 million (about $170 million) to the CCRT. To date, the United States has not contributed to the CCRT.48

World Bank and Regional Development Banks

The World Bank announced that it is making up to $12 billion in financing ($8 billion of which is new) immediately available to help impacted developing countries.49 This support comprises up to $2.7 billion in new financing from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the World Bank's market-rate lending facility for middle-income developing countries and $1.3 billion from the International Development Association (IDA), the World Bank's concessional facility for low-income countries. In addition, the Bank is reprioritizing $2 billion of the Bank's existing portfolio. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Bank's private-sector lending arm is making available up to $6 billion. According to the Bank, support will cover a wide range of activities including strengthening health services and primary health care, bolstering disease monitoring and reporting, training front line health workers, encouraging community engagement to maintain public trust, and improving access to treatment for the poorest patients.

Several years ago, the World Bank introduced pandemic bonds, a novel form of catastrophe financing.50 The Bank sold two classes of bonds worth $320 million in a program designed to provide financing to developing countries facing an acute epidemic crisis if certain triggers are met. Once these conditions are met, bondholders no longer receive interest payments on their investments, the money is no longer repaid in full, and funds are used to support the particular crisis. In the case of Covid-19, for the bonds to be triggered, the epidemic must be continuing to grow 12 weeks after the first day of the outbreak. Critics have raised a range of concerns about the bonds, arguing that the terms are too restrictive and that the length of time needs to be shortened before triggering the bonds.51 Others stress that the proposal remains valid – shifting the cost of pandemic assistance from governments to the private sector, especially in light of the failure of past efforts to rally donor support to establish multilateral pandemic funds.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has approved a total of $4 million to help developing countries in Asia and the Pacific.52 Of the total, $2 million is for improving the immediate response capacity in Cambodia, China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam; $2 million will be available to all ADB developing member countries in updating and implementing their pandemic response plans. The ADB also provided a private sector loan of up to $18.6 million to Wuhan-based Jointown Pharmaceutical Group Co. Ltd. to enhance the distribution and supply of essential medicines and protective equipment.

International Economic Cooperation

On March 16, 2020, the leaders of the G-7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) held an emergency summit by teleconference to discuss and coordinate their policy responses to the economic fallout from the global spread of Covid-19. In the joint statement released by the G-7 leaders after the emergency teleconference summit, the leaders stressed they are committed to doing "whatever is necessary to ensure a strong global response through closer cooperation and enhanced cooperation of efforts."53 The countries pledged to coordinate research efforts, increase the availability of medical equipment; mobilize "the full range" of policy instruments, including monetary and fiscal measures as well as targeted actions, to support workers, companies, and sectors most affected by the spread of Covid-19; task the finance ministers to coordinate on a weekly basis, and direct the IMF and the World Bank Group, as well as other international organizations, to support countries worldwide as part of a coordinated global response.54

News reports indicate that Saudi Arabia, the 2020 chair of the G-20, intends to call an emergency G-20 summit in coming days.55 The G-20 is a broader group of economies, including the G-7 countries and several major emerging markets.56 During the global financial crisis, world leaders decided that henceforth the G-20 would be the premiere forum for international economic cooperation. Some analysts have been surprised that the G-7 has been in front of the G-20 in responding to Covid-19, while other analysts have questioned whether the larger size and diversity of economies in the G-20 can make coordination more difficult.57

Analysts are hopeful that the recent G-7 summit, and movement towards a G-20 summit, will mark a shift towards greater international cooperation at the highest (leader) levels in combatting the economic fallout from the spread of Covid-19.58 An emergency of G-7 finance ministers on March 3, 2020, fell short of the aggressive and concrete coordinated action that investors and economists had been hoping for, and U.S. and European stock markets fell after the meeting.59 More generally, governments have been divided over the appropriate response and in some cases have acted unilaterally, particularly when closing borders and imposing export restrictions on medical equipment and medicine. Meanwhile, international organizations including the IMF and multilateral development banks have tried to forge ahead with economic support given their current resources

Estimated Effects on Developed and Major Economies

Among most developed and major developing economies, economic growth at the beginning of 2020 was tepid, but still was estimated to be positive. Countries highly dependent on trade—Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, and South Korea—and commodity exporters are now projected to be the most negatively affected by the slowdown in economic activity associated with the virus.60 In addition, travel bans and quarantines are taking an especially heavy economic toll on China, South Korea, and Italy, where viral outbreaks have so far been most prevalent. The OECD notes that production declines in China have spillover effects around the world given China's role in producing computers, electronics, pharmaceuticals and transport equipment, and as a primary source of demand for many commodities.61

In early January 2020, before the coronavirus outbreak, economic growth in developing economies as a whole was projected by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be slightly more positive than in 2019. This outlook was based on progress being made in U.S.-China trade talks that were expected to roll back some tariffs and an increase in India's rate of growth. Growth rates in Latin America and the Middle East were also projected to be positive in 2020.62 These projections likely will be revised downward due to the slowdown in global trade associated with Covid-19, lower energy and commodity prices, and other secondary effects that could curtail growth. Commodity exporting countries, in particular, likely will experience a greater slowdown in growth than forecasted in earlier projections as a result of a slowdown on trade with China and lower commodity prices.

Emerging Markets

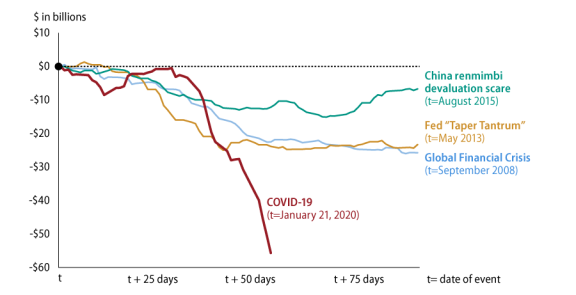

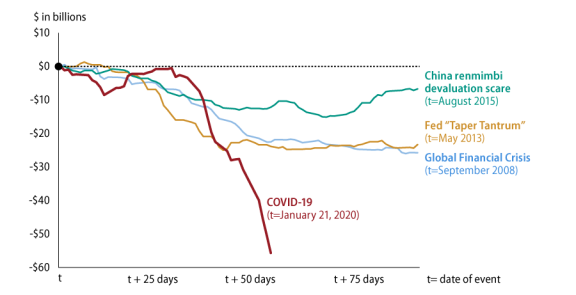

The combined impact of Covid-19 and an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia are hitting developing and emerging economies hard. Not all of these countries have the resources or policy flexibility to respond effectively. According to figures compiled by the Institute for International Finance (IIF), cumulative capital outflows from developing countries since January 2020 are double the level experienced during the 2008/2009 crisis and substantially higher than recent market events (Figure 1).63

|

Figure 1. Capital Flows to Emerging Markets in Global Shocks |

|

|

Source: : Original graphic and data from International Institute for Finance using data from Haver. Edited by CRS for clarification. |

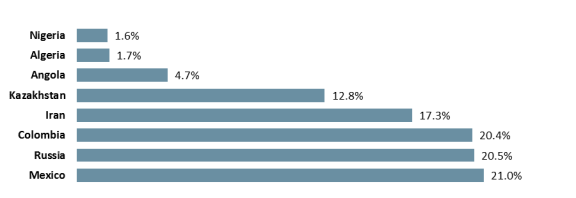

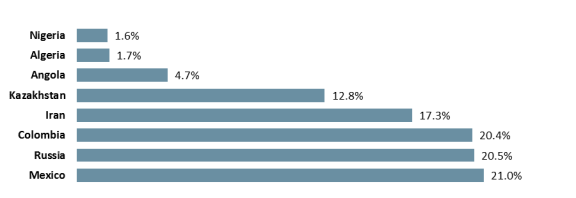

The impact of the price war and lower energy demand associated with a Covid-19-related economic slowdown is especially hard on oil and gas exporters, some of whose currencies are at record lows (Figure 2). Oil importers, such as South Africa and Turkey, have also been hit hard; South Africa's rand has fallen 18%64 against the dollar since the beginning of 2020 and the Turkish lira has lost 8.5%.65

Depending on individual levels of foreign exchange reserves and the duration of the capital flow slowdown, some countries may have sufficient buffers to weather the slowdown, while others will likely need to make some form of current account adjustment (reduce spending, raise taxes, etc). Several countries, such as Iran and Venezuela, have already asked the IMF for financial assistance and others are likely to follow.66 (Venezuela's request was quickly rebuffed due to disagreement among the IMF membership over who is recognized as Venezuela's legitimate leader: Nicolás Maduro or Juan Guaidó.67)

|

Figure 2. Depreciation Against the Dollar Since Jan. 1, 2020 |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Data from Bloomberg. |

Other Affected Sectors

Public concerns over the spread of the virus have led to self-quarantines, reductions in airline and cruise liner travel, the closing of such institutions as the Louvre, and the rescheduling of theatrical releases of movies, including the sequel in the iconic James Bond series (titled, "No Time to Die").68 School closures, so far in China, Japan, South Korea, Italy, India, and some U.S, States are affecting at least 290 million children worldwide, challenging parental leave policies.69 Other countries are limiting the size of public gatherings.

Some businesses are considering new approaches to managing their workforces and work methods. These techniques build on, or in some places replace, such standard techniques as self-quarantines and travel bans. Some firms are adopting an open-leave policy to ensure employees receive sick pay if they are, or suspect they are, sick. Other firms are adopting paid sick leave policies to encourage sick employees to stay home and are adopting remote working policies.70 Concerns remain, however, that some U.S. workers will continue going to work when they are sick, since not all U.S. employers provide paid sick leave. Microsoft and Amazon have instructed all of their Seattle-based employees to work from home until the end of March 2020.71

The drop in business and tourist travel is causing a sharp drop in scheduled airline flights by as much as 10%; airlines are estimating they could lose $113 billion in 2020 (an estimate that could prove optimistic given the Trump Administration's announced restrictions on flights from Europe to the United States),72 while airports in Europe estimate they could lose $4.3 billion in revenue due to fewer flights.73 Industry experts estimate that many airlines will be in bankruptcy by May 2020 under current conditions as a result of travel restrictions imposed by a growing number of countries.74 The loss of Chinese tourists is another economic blow to countries in Asia and elsewhere that have benefitted from the growing market for Chinese tourists and the stimulus such tourism has provided.

The decline in industrial activity has reduced demand for energy products such as crude oil, causing prices to drop sharply, which negatively affects energy producers, renewable energy producers, and electric vehicle manufacturers, but generally is positive for consumers and businesses. Saudi Arabia is pushing other OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) members collectively to reduce output by 1.5 million barrels a day to raise market prices. U.S. shale oil producers, who are not represented by OPEC, support the move to raise prices.75 An unwillingness by Russia to agree to output reductions added to other downward pressures on oil prices and caused Saudi Arabia to engage in a price war with Russia that has driven oil prices below $50 per barrel, the estimated break-even point for most oil producing countries.76 In 2019, low energy prices combined with high debt levels reportedly caused U.S. energy producers to reduce their spending on capital equipment, reduced their profits and, in some cases, led to bankruptcies.77 Reportedly, in late 2019 and early 2020, bond and equity investors, as well as banks, reduced their lending to shale oil producers and other energy producers that typically use oil and gas reserves as collateral.78

Disruptions to industrial activity in China reportedly are causing delays in shipments of computers, cell phones, toys, and medical equipment.79 Factory output in China, the United States, Japan, and South Korea all declined in the first months of 2020.80 Reduced Chinese agricultural exports, including to Japan, are leading to shortages in some commodities. In addition, numerous auto producers are facing shortages in parts and other supplies that have been sourced in China. Reductions in international trade have also affected ocean freight prices. Some freight companies argue that they could be forced to shutter if prices do not rebound quickly.81 Disruptions in the movements of goods and people reportedly are causing some companies to reassess how international they want their supply chains to be.82 According to some estimates, nearly every member of the Fortune 1000 is being affected by disruptions in production in China.83

Conclusions

The quickly evolving nature of the Covid-19 crisis creates a number of issues that make it difficult to estimate the full cost to global economic activity. These issues include, but are not limited to:

- How long will the crisis last?

- How many workers will be affected both temporarily and permanently?

- How many countries will be infected and how much economic activity will be reduced?

- When will the economic effects peak?

- How much economic activity will be lost as a result of the viral outbreak?

- What are the most effective monetary and fiscal policies at the national and global level to address the crisis?

- What temporary and permanent effects will the crisis have on how businesses organize their work forces?

- Many of the public health measures taken by Italy, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, China, etc. have sharply impacted their economies (plant closures, travel restrictions, etc.). How are the tradeoffs between public health and the economic impact of policies to contain the spread of the virus being weighed?

Appendix.

Select Measures Implemented or Announced by Major Economies in Response to COVID-19

|

United States |

U.S. Federal Reserve March 3: Cut the target range for the federal funds rate by 0.5 percentage point. March 12: Expanded reverse repo operations, adding $1.5 trillion of liquidity to the banking system. March 15: Cut the target range for the federal funds rate by a full percentage point to a range of 0.00% to 0.25% and restarted quantitative easing with the purchase of at least $500 billion in Treasury securities and $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities. U.S. Congress March 5: Passed, and the President signed, a bill providing $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies to respond to the coronavirus outbreak (H.R. 6074: Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act 2020). March 13: The House of Representatives passed a coronavirus response package (H.R. 6201: Families First Coronavirus Response Act). The Senate is expected to follow this week. Trump Administration March 13: President Trump declared a state of emergency, allowing the Federal Government to distribute up to $50 billion in aid to states, cities, and territories. March 17: The Internal Revenue Service postponed the April 15 tax-payment deadline for 90 days and will waive interest and penalties. (The extension and waiver is available only to individuals and corporations that owe $1 million or $10 million or less, respectively,) March 17: Administration officials begin negotiations with Members of Congress on a third stimulus package of $850 billion. |

|

Australia |

March 12: The government announced a AU$17.6 billion ($11.4 billion) stimulus package that includes support for business investment, cash flow assistance for small and medium sized business and employees, and household stimulus payments. March 16: The Australian Securities and Investments Commission ordered large equity market participants to reduce their number of executed trades by 25% from the levels executed on March 13, 2020, until further notice. |

|

Canada |

Bank of Canada March 13: Lowered its benchmark overnight rate to 1.25% from 1.75% in response to the epidemic. Canadian Government March 11: Unveiled CA$1 billion ($750 million) in funding for vaccine research and health measures. March 13: Announced CA$10 billion ($7.5 billion) credit package to help businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises, struggling due to the pandemic. |

|

Chile |

March 16: The Central Bank of Chile cut its benchmark rate by 75 basis points to 1% on Monday and announced measures to inject liquidity, including allocating $4 billion to purchase inflation-linked bank bonds and providing additional credit to banks. |

|

China |

People's Bank of China (PBOC) February 3: Expanded reverse repo operations by $174 billion; added another $71 billion on February 4. February 16: Cut the one-year medium-term lending facility rate by 10 basis points. February 20: Cut the one-year and five-year prime rates by 10 and 5 basis points, respectively. March 13: Lowered bank reserve requirements, freeing up about $79 billion to be lent out. PRC Government February: Asked banks to extend the terms of business loans and commercial landlords to reduce rents. March: Earmarked $15.9 billion to fight the epidemic. |

|

Czech Republic |

March 16: The Czech National Bank lowered its main two-week repo rate by 50 basis points to 1.75%, reversing its February rate hike to combat the hit from the virus outbreak. It also raised the number of repo operations that provide liquidity to banks to three times a week from once, noting that bids would be met with zero spread to the repo rate. |

|

Egypt |

Central Bank of Egypt March 16: Cut by 300 basis points both the overnight lending rate (from 13.25% to 10.25%) and the overnight deposit rate (from 12.25% to 9.25%) in what it described as a "preemptive" move to support the economy in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak. Government of Egypt March 14: The President indicated that the government will allocate 100 billion Egyptian pounds ($6.4 billion) to finance a "comprehensive" state plan for combating the coronavirus outbreak. |

|

European Union |

European Commission March 11: Announced a 37 billion euro ($41 billion) "Corona Investment Fund" that would use "spare" money from the EU budget to help businesses, health-care systems, and sectors in need; additionally, the EU's own investment fund will guarantee 8 billion euros ($8.9 billion) of loans to 100,000 small- and medium-sized enterprises and affected companies may be able to delay the payment of their existing loans. European Central Bank (ECB) March 12: Announced that it would provide banks with loans at a rate as low as minus 0.75%, below the-0.5% deposit rate, increase bond purchases by 120 billion euros ($135.28 billion) this year (with a focus on corporate debt), and allow euro zone banks to fall short of some key capital and cash requirements (in order to keep credit flowing to the economy). |

|

France |

March 12: The government pledged more generous guarantees on loans made to small businesses, more cash for firms struggling to hold on to workers, and a solidarity fund to help companies cushion the blow from the coronavirus outbreak; it also announced that the government would be ready to increase funds available to help companies reduce workers' hours, instead of laying them off. March 16: The president announced that the government would guarantee 300 billion euros in bank loans for small and medium-sized businesses. March 17: The Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF), France's financial-markets authority, stated that it would forbid short selling of stock in 92 companies during the March 17 session. March 17: The government announced that it would spend 45 billion euros ($50 billion) to help small businesses and employees struggling with the coronavirus outbreak, including through an expanded partial-unemployment package in which the state pays the salaries of employees who are not needed during the crisis. |

|

Germany |

March 13: Pledged to provide unlimited liquidity assistance to German companies hit by the pandemic. (The measure envisages a massive expansion of loans provided by KfW, the state development bank, and will allow companies to defer billions of euros in tax payments.) The Bundestag also expanded the Kurzarbeit or short-time work scheme, under which companies that put their workers on reduced hours can receive state support. The government also indicated that it would boost investments by €3.1 billion per year between 2021 and 2024. |

|

Hong Kong |

February 26: The government announced a HK$120 billion ($15.4 billion) relief package as part of its 2020-2021 budget, including a payment of HK$10,000 ($1,200) to each permanent resident of the city 18 or older, paying one month's rent for people living in public housing, cutting payroll, income, property, and business taxes, low-interest, government-guaranteed loans for businesses, and an extra month's worth of payments to people collecting old-age or disability benefits. |

|

India |

Reserve Bank of India March 12: Announced a $2 billion injection into the foreign-exchange market to support the rupee. March 13: Announced a plan to add liquidity through short-term repurchase operations. Government of India March 15: Pledged $10 million towards South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) "coronavirus emergency fund." |

|

Italy |

March 11: The government announced two packages worth 25 billion euros ($28.3 billion): A package worth 12 billion euros will provide extra funding for the health system as well as a mix of measures to help companies and households, including freezing tax and loan payments and boosting unemployment benefits to ensure no jobs were lost. The remainder will be a reserve to pay for any further measures. The government also indicated that payments on mortgages will be suspended across Italy. ABI, Italy's banking lobby, said lenders would offer debt moratoriums to small firms and households grappling with the economic fallout from the virus. |

|

Japan |

Bank of Japan March 16: Announced that it would (1) double its upper limit of annual purchases of exchange traded funds to 12 trillion yen ($112.46 billion) and of real-estate investment trusts to 180 billion yen ($1.7 billion) per year, (2) expand its upper limit of its corporate bond balance and commercial paper balance by 1 trillion yen ($9.5 billion) each, and (3) start a lending program for commercial banks, providing them with one-year loans in exchange for corporate collateral worth 8 trillion yen ($75.6 billion). Japanese Government February 13: Unveiled a set of measures worth 15.3 billion yen ($140 million) to fight the spread of coronavirus; secured 500 billion yen ($4.7 billion) for emergency lending and loan guarantees at the Japan Finance Corporation and other institutions for small businesses hit hard by the virus outbreak. March 10: Unveiled a second package of measures totaling 430.8 billion yen ($4.1 billion) in spending to cope with the fallout of the coronavirus outbreak (focusing on support to small and mid-sized firms) and boosted to 1.6 trillion yen ($15.1 billion) its special financing for small- and mid-size firms hit by the virus, up from 500 billion yen. |

|

Kuwait |

March 16: The Central Bank of Kuwait cut by 100 basis points its deposit rate to 1.5% and its overnight, one-week, and one-month repo rates to 1%, 1.25%, and 1.75%, respectively. |

|

Mexico |

February 13: The Bank of Mexico cut its key rate by 25 basis points to 7.0%. |

|

New Zealand |

Government of New Zealand March 16: Announced a spending package of NZ$12.1 billion ($7.3 billion), equivalent to 4% of GDP in an attempt to fight the effects of Covid-19 on the economy; approximately NZ$5 billion will go toward wage subsidies for businesses, NZ$2.8 billion toward income support, NZ$2.8 billion in business tax relief, and NZ$600 million toward the airline industry. Reserve Bank of New Zealand March 16: Cut the official cash rate by 75 basis points to a record low of 0.25%, and pledged to keep it at this level for at least 12 months. |

|

Norway |

March 13: The Norges Bank, Norway's central bank, cut its key interest rate to 1% from 1.5%, as it seeks to counter the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic. It indicated that it would offer funding to banks to help counter the volatility in financial markets and announced that banks' countercyclical capital buffer would be reduced from 2.5% to 1%, to help banks continue to lend money. |

|

Philippines |

March 13: The government instructed the Government Service Insurance System and the Social Security System "to take advantage of the low stock prices" and "support the stock market by at least doubling their daily average purchase volumes" from 2019. March 17: The Philippine Stock Exchange halted all stock, bond and currency trading until further notice, after President Rodrigo Duterte placed Luzon, the country's economic powerhouse, under "enhanced community quarantine". |

|

Qatar |

Qatar Central Bank March 16: Cut the deposit rate by 50 basis points to 1%, lending rate by 100 basis points to 2.50%, and repurchase rate (repo) by 50 basis points to 1%. Government of Qatar March 15: The Emir of Qatar announced several measures to shield the economic and financial sectors in the country from the impact of the coronavirus, including: (1) allocating 75 billion Qatari riyals ($20.6 billion) to support and provide financial and economic incentives in the private sector, (2) directing the Central Bank of Qatar to provide additional liquidity to banks operating in the country and putting in place the appropriate mechanism to encourage banks to postpone loan installments and obligations of the private sector with a grace period of six months, (3) directing the Qatar Development Bank to postpone the installments for all borrowers for a period of six months, (4) directing the government to increase its investments in the stock exchange by 10 billion Qatari riyals ($2.75 billion), (5) exempting food and medical goods from customs duties for a period of six months, and (6) exempting the various sectors of the economy from electricity and water fees for a period of 6 months. |

|

Saudi Arabia |

March 15: The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority announced that it had prepared a 50 billion riyal ($13.32 billion) package to help small and medium-sized enterprises cope with the economic impacts of coronavirus; it also lowered by 75 basis points both its repo rate to 1%, and its reverse repo rate to 0.5%. |

|

Singapore |

February 18: The government announced around $4.5 billion in financial packages to help contain the coronavirus outbreak, including $575 million to fight and contain the disease, mainly through healthcare funding, and 4 billion in economic stimulus measures to manage its impact on businesses, jobs and households. |

|

South Korea |

March 3: Announced a 11.7 trillion won ($9.8 billion) stimulus package that includes funding for medical institutions and quarantine efforts, assistance to small- to medium-sized businesses struggling to pay wages to their workers, and subsidies for child care. |

|

Spain |

March 12: The government announced additional support for the health system and a 14 billion euro ($15.6 billion) stimulus package for the economy. |

|

Sri Lanka |

March 16: The Central Bank of Sri Lanka cut the Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and the Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) by 25 basis points to 6.25% and 7.25%, respectively, and the Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) on all rupee deposit liabilities of licensed commercial banks was reduced by 1 percentage point to 4% March 16: The Colombo Stock Exchange was closed until March 19, as the government extended the public holiday in a bid to halt the spread of coronavirus in the country. |

|

Sweden |

Sveriges Riksbank March 16: Announced that it would buy securities for up to an additional 300 billion Swedish crowns ($31 billion) in 2020 to facilitate credit supply and mitigate the downturn in the economy caused by the coronavirus, reduced the overnight lending rate to banks to 0.2 percentage point above its repo rate (from 0.75 percentage point), and indicated that it would be flexible with the collateral banks can use when they borrow money from the Riksbank, giving lenders more scope to use mortgage bonds as collateral. Government of Sweden March 16: Presented a package worth more than 300 billion Swedish crowns ($31 billion) to support the economy in the face of the coronavirus pandemic. It included measures such as the central government assuming the full cost for sick leave from companies through the months of April and May 2020 and for temporary redundancies due to the crisis, and allowing companies to put off paying tax and VAT for up to a year (retroactive to the start of 2020). |

|

Taiwan |

February 25: The government approved a T$60 billion ($2 billion) package to help cushion the impact of the coronavirus outbreak on its export-reliant economy, including loans for small businesses, subsidies for hard-hit tour agencies, tax cuts for tour bus drivers, and vouchers to spend on food in night markets. March 12: The president announced that an additional T$40 billion ($1.33 billion) from the Employment Stabilization Fund and the Tourism Development Fund would be available to stimulate Taiwanese economy. |

|

United Arab Emirates (UAE) |

March 15: The Central Bank of the UAE announced a 100 billion dirham ($27 billion) stimulus package to deal with the economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic; it cut the rate on one-week certificates of deposit by 75 basis points and will also ease regulatory limits on loans. |

|

United Kingdom |

Bank of England March 11: Cut its benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point, to 0.25%, revived a program to support lending to small and midsize businesses, and reduced bank capital requirements to further boost credit. UK Government March 11: Announced a stimulus package totaling 30 billion pounds ($39 billion). It will include 7 billion pounds ($8.6 billion) available to support the labor market, 5 billion pounds ($6.1 billion) to help the health-care system, and 18 billion pounds ($22 billion) to support the UK economy, bringing the total fiscal stimulus to 30 billion pounds ($39 billion). (Among the specific measures, there will be a tax cut for retailers, cash grants to small businesses, a mandate to provide sick pay for people who need to self-isolate, subsidies to cover the costs of sick pay for small businesses, and expanded access to government benefits for the self-employed and unemployed.) |

|

Vietnam |

March 16: The State Bank of Vietnam cut by 100 basis points both its refinance rate (to 5%) and the overnight lending rate in the inter-bank market (to 6%), and by 50 basis points its discount rate (to 3.5%). |

Sharp declines in the stock market and broader financial sector turbulence; interest rate cuts and large-scale Federal Reserve intervention; and discussions of massive government stimulus packages have led some observers to compare the current market reaction to that experienced a little over a decade ago. There are similarities and important differences between the current economic crisis and the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Foremost, the earlier crisis was rooted in structural weakness in the U.S. financial sector. Following the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble, it became impossible for firms to identify demand and hold inventories (across many sectors (construction, retail, etc). This led to massive oversupply and sharp retail losses which extended to other sectors of the U.S. economy and eventually the global economy. Moreover, financial markets across countries were linked together by credit default swaps. As the crisis unfolded, large numbers of banks and other financial institutions were negatively affected, raising questions about capital sufficiency and reserves. The crisis, then quickly engulfed credit-rating agencies, mortgage lending companies and the real estate industry broadly. Market resolution came gradually with a range of monetary and fiscal policy measures that were closely coordinated at the global level. These were focused on putting a floor under the falling markets, stabilizing banks, and shoring up investor confidence to get spending started again. Starting in September 2007, The Federal Reserve cut interest rates from over 5% in September 2007 to between 0 and 0.25% before the end of the 2008. Once interest rates approached zero, the Fed turned to other so-called "unconventional measures" including targeted assistance to financial institutions, including encouraging Congress to pass the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and the Term Asset Backed Security Loan Facility (TALF) to prevent the collapse of the financial sector and boost consumer spending. Other measures included forced bank capitalizations (or bank nationalizations in other countries), swap arrangements between the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank and smaller central banks, and so-called "quantitative easing" to boost the money supply. On a global level, the United States and other countries tripled the resources of the IMF (from $250 billion to $750 billion) and coordinated domestic stimulus efforts.

Unlike the 2008 crisis, the current crisis began as a supply shock. As the global economy has become more interdependent in recent decades, most products are produced as part of a global value chain (GVC), where an item such as a car or mobile device consists of parts manufactured all over the world, and involving multiple border crossings before final assembly. The earliest implications of the current crisis came in January as plant closures in China and other parts of Asia led to interruptions in the supply chain and concerns about dwindling inventories. As the virus spread from Asia to Europe, the crisis switched from supply concerns to a broader demand crisis as the measures being introduced to contain the spread of the virus (social distancing, travel restrictions, cancelling sporting events, closing shops and restaurants, and mandatory quarantine measures) prevent most forms of economic activity from occurring. Thus, unlike the 2008 crisis response, which involved liquidity and solvency-related policy measures to get people spending again, the current crisis is related to the amount of operating capital in the economy. While larger firms may have sufficient capital to wait out a crisis, many aspects of the economy (such as restaurants or retail operations) operate on very tight margins and would likely not be able to pay employees after closures lasting more than a few days. Many people will also need to balance child care and work during quarantine or social distancing measures. During this type of crisis, while monetary policy measures play a part -- and the Federal Reserve has once again cut rates to near zero -- they cannot compensate for the physical interaction that the global economy is dependent upon. As a result, fiscal stimulus will likely play a relatively larger role in this crisis in order to prevent personal and corporate bankruptcies during the peak crisis period. Efforts to coordinate U.S. and foreign economic policy measures will also have an important role in mitigating the scale and length of any global economic downtown.

Emerging Markets

The combined impact of Covid-19 and an oil price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia are hitting developing and emerging economies hard. Not all of these countries have the resources or policy flexibility to respond effectively. According to figures compiled by the Institute for International Finance (IIF), cumulative capital outflows from developing countries since January 2020 are double the level experienced during the 2008/2009 crisis and substantially higher than recent market events (Figure 1).63

|

Figure 1. Capital Flows to Emerging Markets in Global Shocks |

|

|

Source: : Original graphic and data from International Institute for Finance using data from Haver. Edited by CRS for clarification. |

The impact of the price war and lower energy demand associated with a Covid-19-related economic slowdown is especially hard on oil and gas exporters, some of whose currencies are at record lows (Figure 2). Oil importers, such as South Africa and Turkey, have also been hit hard; South Africa's rand has fallen 18%64 against the dollar since the beginning of 2020 and the Turkish lira has lost 8.5%.65

Depending on individual levels of foreign exchange reserves and the duration of the capital flow slowdown, some countries may have sufficient buffers to weather the slowdown, while others will likely need to make some form of current account adjustment (reduce spending, raise taxes, etc). Several countries, such as Iran and Venezuela, have already asked the IMF for financial assistance and others are likely to follow.66 (Venezuela's request was quickly rebuffed due to disagreement among the IMF membership over who is recognized as Venezuela's legitimate leader: Nicolás Maduro or Juan Guaidó.67)

|

Figure 2. Depreciation Against the Dollar Since Jan. 1, 2020 |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS. Data from Bloomberg. |