Introduction

Today the federal government owns and manages roughly 640 million acres of land in the United States, or roughly 28% of the 2.27 billion total land acres.1 Four major federal land management agencies manage 606.5 million acres of this land, or about 95% of all federal land in the United States. These agencies are as follows: Bureau of Land Management (BLM), 244.4 million acres; Forest Service (FS), 192.9 million acres; Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), 89.2 million acres; and National Park Service (NPS), 79.9 million acres. Most of these lands are in the West, including Alaska. A fifth agency, the Department of Defense (DOD) administers 8.8 million acres in the United States,2 about 1% of all federal land.3 Together, the five agencies manage about 615.3 million acres. The remaining acreage, approximately 4% of all federal land in the United States, is managed by a variety of other government agencies.

Ownership and use of federal lands have stirred controversy for decades.4 Conflicting public values concerning federal lands raise many questions and issues, including the extent to which the federal government should own land; whether to focus resources on maintenance of existing infrastructure and lands or acquisition of new areas; how to balance use and protection; and how to ensure the security of international borders along the federal lands of multiple agencies. Congress continues to examine these questions through legislative proposals, program oversight, and annual appropriations for the federal land management agencies.

Historical Background

Federal lands and resources have played a significant role in American history, adding to the strength and stature of the federal government, serving as an attraction and opportunity for settlement and economic development, and providing a source of revenue for schools, transportation, national defense, and other national, state, and local needs.

The formation of the U.S. federal government was particularly influenced by the struggle for control over what were then known as the "western" lands—the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River that were claimed by the original colonies. The original states reluctantly ceded the lands to the developing new government. This cession, together with granting constitutional powers to the new federal government, including the authority to regulate federal property and to create new states, played a crucial role in transforming the weak central government under the Articles of Confederation into a stronger, centralized federal government under the U.S. Constitution.

Subsequent federal land laws sought to reserve some federal lands (such as for national forests and national parks) and to sell or otherwise dispose of other lands to raise money or encourage transportation, development, and settlement. From the earliest days, these options took on East/West overtones, with easterners more likely to view the lands as national public property, and westerners more likely to view the lands as necessary for local use and development. Most agreed, however, on measures that promoted settlement of the lands to pay soldiers, to reduce the national debt, and to strengthen the nation. This settlement trend accelerated with federal acquisition of additional territory through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Oregon Compromise with England in 1846, and cession of lands by treaty after the Mexican War in 1848.5

In the mid-to-late 1800s, Congress enacted many laws to encourage and accelerate the settlement of the West by disposing of federal lands. Examples include the Homestead Act of 1862 and the Desert Lands Entry Act of 1877. Approximately 1.29 billion acres of public domain land was transferred out of federal ownership between 1781 and 2018. The total included transfers of 816 million acres to private ownership (individuals, railroads, etc.), 328 million acres to states generally, and 143 million acres in Alaska under state and Native selection laws.6 Most transfers to private ownership (97%) occurred before 1940; homestead entries, for example, peaked in 1910 at 18.3 million acres but dropped below 200,000 acres annually after 1935, until being fully eliminated in 1986.7

Although several earlier laws had protected some lands and resources, such as salt deposits and certain timber for military use, new laws in the late 1800s reflected the growing concern that rapid development threatened some of the scenic treasures of the nation, as well as resources that would be needed for future use. A preservation and conservation movement evolved to ensure that certain lands and resources were left untouched or reserved for future use. For example, Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872 to preserve its resources in a natural condition, and to dedicate recreation opportunities for the public. It was the world's first national park,8 and like the other early parks, Yellowstone was protected by the U.S. Army—primarily from poachers of wildlife or timber. In 1891, concern over the effects of timber harvests on water supplies and downstream flooding led to the creation of forest reserves (renamed national forests in 1907).

Emphasis shifted during the 20th century from the disposal and conveyance of title to private citizens to the retention and management of the remaining federal lands. During debates on the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934,9 some western Members of Congress acknowledged the poor prospects for relinquishing federal lands to the states, but language included in the act left disposal as a possibility. It was not until the enactment of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) that Congress expressly declared that the remaining public domain lands generally would remain in federal ownership.10 This declaration of permanent federal land ownership was a significant factor in what became known as the Sagebrush Rebellion, an effort that started in the late 1970s to strengthen state or local control over federal land and management decisions. Recently, there has been renewed interest in some western states in assuming ownership of some federal lands within their borders. This interest stems in part from concerns about the extent, condition, and cost of federal land ownership and the type and amount of land uses and revenue derived from federal lands. Judicial challenges and legislative and executive efforts generally have not resulted in broad changes to the level of federal ownership. Current authorities for acquiring and disposing of federal lands are unique to each agency.11

Current Federal Land Management

The creation of national parks and forest reserves laid the foundation for the current federal agencies whose primary purposes are managing natural resources on federal lands—the BLM, FS, FWS, and NPS. These four agencies were created at different times, and their missions and purposes differ. As noted, DOD is the fifth-largest land management agency, with lands consisting of military bases, training ranges, and more. These five agencies, which together manage about 96% of all federal land, are described below. Numerous other federal agencies—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation,12 Post Office, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Department of Energy, and many more—each administer relatively small amounts of additional federal lands.

Agencies13

Bureau of Land Management

The BLM was formed in 1946 by combining two existing agencies.14 One was the Grazing Service (first known as the DOI Grazing Division), established in 1934 to administer grazing on public rangelands. The other was the General Land Office, which had been created in 1812 to oversee disposal of the federal lands.15 The BLM currently administers 244.4 million acres, more federal lands in the United States than any other agency. BLM lands are heavily concentrated (more than 99%) in the 11 contiguous western states and Alaska.16

As defined in FLPMA,17 BLM management responsibilities are similar to those of the FS—sustained yields of multiple uses, including recreation, grazing, timber, energy and minerals, watershed, wildlife and fish habitat, and conservation. However, each agency historically has emphasized different uses. For instance, more rangelands are managed by the BLM, while most federal forests are managed by the FS. In addition, the BLM administers more than 700 million acres of federal subsurface mineral estate throughout the nation.18

Forest Service

The FS is the oldest of the four federal land management agencies. It was established in the Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 1905 and is charged with conducting forestry research, providing assistance to nonfederal forest owners, and managing the National Forest System (NFS).19 Today, the FS administers 192.9 million acres of land in the United States,20 predominantly in the West, while also managing about three-fifths of all federal lands in the East (as shown in Table 5).

The first forest reserves—later renamed national forests—originally were authorized to protect the lands, preserve water flows, and provide timber. These purposes were expanded in the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960.21 This act added recreation, livestock grazing, and wildlife and fish habitat as purposes of the national forests, with wilderness added in 1964.22 The act directed that these multiple uses be managed in a "harmonious and coordinated" manner "in the combination that will best meet the needs of the American people." The act also directed the FS to manage renewable resources under the principle of sustained yield, meaning to achieve a high level of resource outputs in perpetuity without impairing the productivity of the lands.

Fish and Wildlife Service

The first national wildlife refuge was established by executive order in 1903, although it was not until 1966 that the refuges were aggregated into the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) administered by the FWS.23 The NWRS includes wildlife refuges, national monument areas, waterfowl production areas, and wildlife coordination units. Outside of the NWRS, the FWS administers lands for administrative sites, National Fish Hatcheries, and national monument areas. In total, the FWS administers 89.2 million acres of federal land in the United States, of which 76.6 million acres (85.9%) are in Alaska.24

The NWRS's mission is to administer a network of lands and waters for the conservation, management, and restoration of fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats.25 Other uses (recreation, hunting, timber cutting, oil or gas drilling, etc.) may be permitted, to the extent that they are compatible with the NWRS mission and an individual unit's purpose.26 However, wildlife-related activities (hunting, bird watching, hiking, education, etc.) are considered "priority uses" and are given priority consideration in refuge planning. It can be challenging to determine compatibility, but the relative clarity of the mission generally has minimized conflicts over refuge management and use, although there are exceptions.27

National Park Service

The NPS was created in 1916 to manage the growing number of park units established by Congress and monuments proclaimed by the President.28 By September 30, 2018, the National Park System had grown to 417 units with 79.9 million acres of federal land in the United States. About two-thirds of the lands (52.5 million acres, or 65. 6%) are in Alaska.29 NPS units have diverse titles—national park, national monument, national preserve, national historic site, national recreation area, national battlefield, and many more.30

The NPS has a dual mission—to preserve unique resources and to provide for their enjoyment by the public. Activities that harvest or remove resources from NPS lands generally are prohibited. Park units include spectacular natural areas, unique prehistoric sites, and special places in American history, as well as recreational opportunities. The tension between providing recreation and preserving resources has caused many management challenges.

Department of Defense

The National Security Act of 1947 established a Department of National Defense (later renamed the Department of Defense, or DOD) by consolidating the previously separate Cabinet-level Department of War (renamed Department of the Army) and Department of the Navy and creating the Department of the Air Force.31 Responsibility for managing the land on federal military reservations was retained by these departments, with some transfer of Army land to the Air Force upon its creation.

There are more than 4,775 defense sites worldwide on a total of 26.9 million acres of land owned, leased, or otherwise possessed by DOD. Of the DOD sites, DOD owns 8.8 million acres in the United States, with individual parcel ownership ranging from 1 acre to more than a million acres.32 Although management of military reservations remains the responsibility of each of the various military departments and defense agencies, those secretaries and directors operate under the centralized direction of the Secretary of Defense. With regard to natural resource conservation, defense instruction provides that

The principal purpose of DOD lands, waters, airspace, and coastal resources is to support mission-related activities. All DOD natural resources conservation program activities shall work to guarantee DOD continued access to its land, air, and water resources for realistic military training and testing and to sustain the long-term ecological integrity of the resource base and the ecosystem services it provides.... DOD shall manage its natural resources to facilitate testing and training, mission readiness, and range sustainability in a long-term, comprehensive, coordinated, and cost-effective manner.33

Federal Land Ownership, 2018

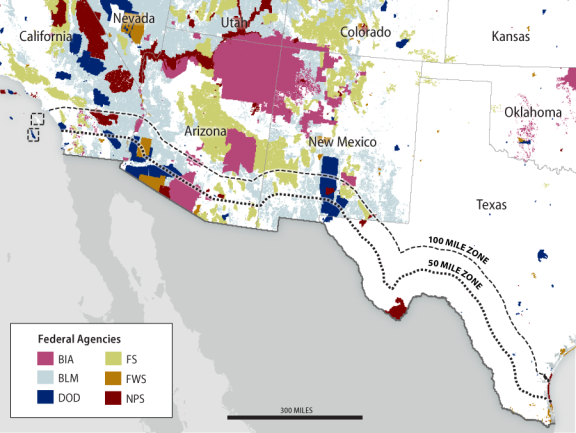

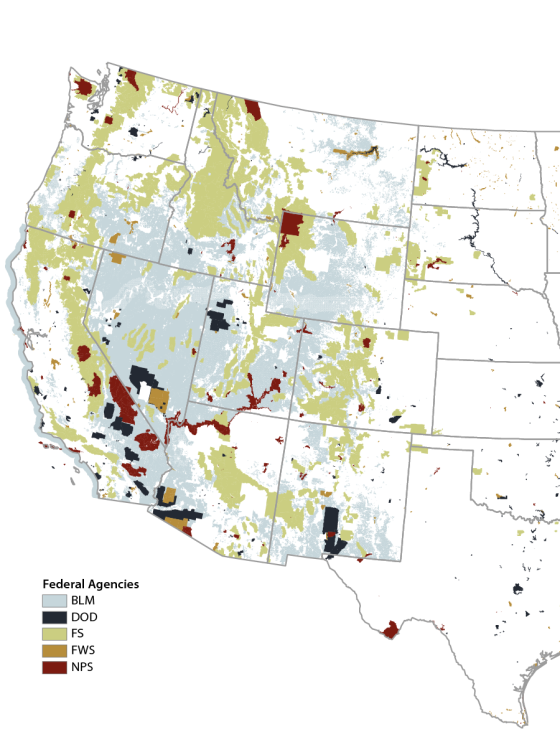

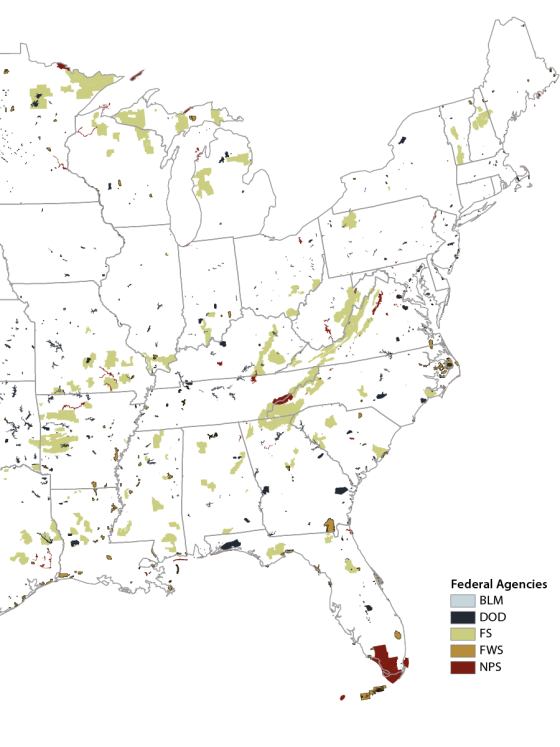

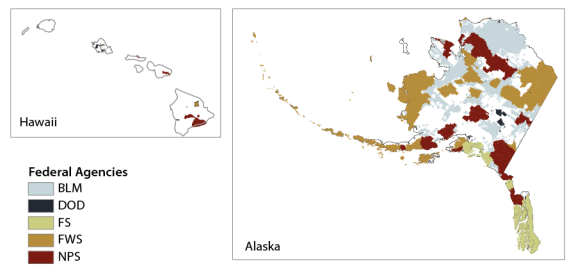

The 615.3 million acres of federal land in the United States managed by the five major land management agencies represents about 27% of the total land base of 2.27 billion acres. Table 1 provides data on the total acreage of federal land administered by the four major federal land management agencies and the DOD in each state and the District of Columbia. The lands administered by each of the five agencies in each state are shown in Table 2.34 These tables reflect federal acreage as of September 30, 2018, except that DOD figures are current as of September 30, 2017. The figures understate total federal land, since they do not include lands administered by other federal agencies, such as the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department of Energy. Table 1 also identifies the total acreage of each state and the percentage of land in each state administered by the five federal land agencies. These percentages point to significant variation in the federal presence within states. The figures range from 0.3% of land (in Connecticut and Iowa) to 80.1% of land (in Nevada). Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3 show these federal lands. Figure 1 is a map of federal lands in the West; Figure 2 is a map of federal lands in the East; and Figure 3 is a map of federal lands in Alaska and Hawaii.

Although 15 states contain less than half a million acres of federal land,35 the 11 western states and Alaska each have more than 10 million acres managed by these five agencies within their borders. This contrast is a result of early treaties, land settlement laws and patterns, and laws requiring that states agree to surrender any claim to federal lands within their border as a prerequisite for admission to the Union. Management of these lands is often controversial, especially in states where the federal government is a predominant or majority landholder and where competing and conflicting uses of the lands are at issue.

|

Total Federal |

Total Acreage |

Federal Acreage's |

|

|

Alabama |

880,188 |

32,678,400 |

2.7% |

|

Alaska |

222,666,580 |

365,481,600 |

60.9% |

|

Arizona |

28,077,992 |

72,688,000 |

38.6% |

|

Arkansas |

3,159,486 |

33,599,360 |

9.4% |

|

California |

45,493,133 |

100,206,720 |

45.4% |

|

Colorado |

24,100,247 |

66,485,760 |

36.2% |

|

Connecticut |

9,110 |

3,135,360 |

0.3% |

|

Delaware |

29,918 |

1,265,920 |

2.4% |

|

District of Columbia |

9,649 |

39,040 |

24.7% |

|

Florida |

4,491,200 |

34,721,280 |

12.9% |

|

Georgia |

1,946,492 |

37,295,360 |

5.2% |

|

Hawaiia |

829,830 |

4,105,600 |

20.2% |

|

Idaho |

32,789,648 |

52,933,120 |

61.9% |

|

Illinois |

423,782 |

35,795,200 |

1.2% |

|

Indiana |

384,726 |

23,158,400 |

1.7% |

|

Iowa |

97,509 |

35,860,480 |

0.3% |

|

Kansas |

253,919 |

52,510,720 |

0.5% |

|

Kentucky |

1,100,160 |

25,512,320 |

4.3% |

|

Louisiana |

1,353,291 |

28,867,840 |

4.7% |

|

Maine |

301,481 |

19,847,680 |

1.5% |

|

Maryland |

205,362 |

6,319,360 |

3.2% |

|

Massachusetts |

62,680 |

5,034,880 |

1.2% |

|

Michigan |

3,637,599 |

36,492,160 |

10.0% |

|

Minnesota |

3,503,977 |

51,205,760 |

6.8% |

|

Mississippi |

1,552,634 |

30,222,720 |

5.1% |

|

Missouri |

1,702,983 |

44,248,320 |

3.8% |

|

Montana |

27,082,401 |

93,271,040 |

29.0% |

|

Nebraska |

546,852 |

49,031,680 |

1.1% |

|

Nevada |

56,262,610 |

70,264,320 |

80.1% |

|

New Hampshire |

805,472 |

5,768,960 |

14.0% |

|

New Jersey |

171,956 |

4,813,440 |

3.6% |

|

New Mexico |

24,665,774 |

77,766,400 |

31.7% |

|

New York |

230,992 |

30,680,960 |

0.8% |

|

North Carolina |

2,434,801 |

31,402,880 |

7.8% |

|

North Dakota |

1,733,641 |

44,452,480 |

3.9% |

|

Ohio |

305,502 |

26,222,080 |

1.2% |

|

Oklahoma |

683,289 |

44,087,680 |

1.5% |

|

Oregon |

32,244,257 |

61,598,720 |

52.3% |

|

Pennsylvania |

622,160 |

28,804,480 |

2.2% |

|

Rhode Island |

4,513 |

677,120 |

0.7% |

|

South Carolina |

875,316 |

19,374,080 |

4.5% |

|

South Dakota |

2,640,005 |

48,881,920 |

5.4% |

|

Tennessee |

1,281,362 |

26,727,680 |

4.8% |

|

Texas |

3,231,198 |

168,217,600 |

1.9% |

|

Utah |

33,267,621 |

52,696,960 |

63.1% |

|

Vermont |

465,888 |

5,936,640 |

7.8% |

|

Virginia |

2,373,616 |

25,496,320 |

9.3% |

|

Washington |

12,192,855 |

42,693,760 |

28.6% |

|

West Virginia |

1,134,138 |

15,410,560 |

7.4% |

|

Wisconsin |

1,854,085 |

35,011,200 |

5.3% |

|

Wyoming |

29,137,722 |

62,343,040 |

46.7% |

|

U.S. Total |

615,311,596 |

2,271,343,360 |

27.1% |

Sources: For federal lands, see sources listed in Table 2. Total acreage of states is from U.S. General Services Administration, Office of Governmentwide Policy, Federal Real Property Profile, as of September 30, 2004, Table 16, pp. 18-19.

Notes: Figures understate federal lands in each state and the total in the United States. They include only land of the five largest land-managing agencies: BLM, FS, FWS, NPS, and DOD lands. Thus, the figures exclude federal lands managed by other agencies, such as the Bureau of Reclamation. They also exclude any land managed by the five agencies in the territories, DOD-managed acreage overseas, submerged lands in the outer continental shelf, and an estimated 662 million acres managed by FWS within the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, primarily marine areas in the Pacific Ocean.

The total federal acreage column does not add to the precise total shown due to small discrepancies in the sources used. This is also the case for some other tables in this report. Also, here and throughout the report, figures might not sum to the totals shown due to rounding.

a. This figure includes approximately 253,000 acres of submerged lands and waters within the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge. Thus, the percentage shown overestimates the area that is federally owned.

|

State |

BLM |

FS |

FWS |

NPS |

DOD |

|

Alabama |

3,011 |

670,889 |

32,585 |

17,540 |

156,163 |

|

Alaska |

71,397,880 |

22,138,560 |

76,649,320 |

52,455,308 |

25,512 |

|

Arizona |

12,120,512 |

11,179,113 |

1,683,512 |

2,658,112 |

436,743 |

|

Arkansas |

1,405 |

2,593,165 |

379,648 |

98,346 |

86,922 |

|

California |

15,088,090 |

20,791,505 |

296,899 |

7,612,898 |

1,703,741 |

|

Colorado |

8,352,437 |

14,487,064 |

174,983 |

665,260 |

420,503 |

|

Connecticut |

0 |

23 |

1,754 |

5,846 |

1,487 |

|

Delaware |

0 |

0 |

25,543 |

890 |

3,485 |

|

Dist. of Col. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8,476 |

1,173 |

|

Florida |

2,239 |

1,203,418 |

293,636 |

2,469,173 |

522,734 |

|

Georgia |

0 |

867,580 |

488,648 |

39,935 |

550,329 |

|

Hawaiia |

0 |

0 |

309,594 |

358,160 |

162,076 |

|

Idaho |

11,776,995 |

20,447,859 |

49,733 |

511,963 |

3,098 |

|

Illinois |

20 |

304,538 |

90,000 |

12 |

29,212 |

|

Indiana |

0 |

204,318 |

16,868 |

10,769 |

152,771 |

|

Iowa |

0 |

0 |

73,427 |

2,708 |

21,374 |

|

Kansas |

1 |

108,621 |

29,509 |

462 |

115,326 |

|

Kentucky |

0 |

818,268 |

11,838 |

94,103 |

175,951 |

|

Louisiana |

2,043 |

608,546 |

582,342 |

17,690 |

142,670 |

|

Maine |

0 |

53,880 |

73,434 |

156,205 |

17,962 |

|

Maryland |

548 |

0 |

49,795 |

41,532 |

113,487 |

|

Massachusetts |

0 |

0 |

23,342 |

33,336 |

6,002 |

|

Michigan |

610 |

2,874,631 |

117,816 |

632,280 |

12,262 |

|

Minnesota |

1,101 |

2,844,937 |

516,150 |

139,789 |

2,000 |

|

Mississippi |

5,048 |

1,190,979 |

211,438 |

104,369 |

40,800 |

|

Missouri |

59 |

1,507,891 |

61,368 |

54,569 |

79,096 |

|

Montana |

8,022,852 |

17,186,331 |

653,097 |

1,214,193 |

5,928 |

|

Nebraska |

5,325 |

351,205 |

174,401 |

5,899 |

10,022 |

|

Nevada |

47,298,840 |

5,760,954 |

2,345,102 |

797,613 |

60,101 |

|

New Hampshire |

0 |

753,921 |

34,716 |

13,696 |

3,139 |

|

New Jersey |

0 |

0 |

73,785 |

35,683 |

62,488 |

|

New Mexico |

13,500,023 |

9,225,354 |

332,058 |

468,968 |

1,139,371 |

|

New York |

0 |

16,352 |

29,301 |

34,106 |

151,233 |

|

North Carolina |

0 |

1,256,493 |

423,879 |

366,889 |

387,540 |

|

North Dakota |

58,032 |

1,103,160 |

488,648 |

71,192 |

12,609 |

|

Ohio |

0 |

244,440 |

9,109 |

20,290 |

31,663 |

|

Oklahoma |

1,942 |

399,578 |

108,046 |

10,011 |

163,712 |

|

Oregon |

15,742,384 |

15,697,445 |

575,379 |

196,197 |

32,852 |

|

Pennsylvania |

0 |

513,891 |

12,614 |

53,460 |

42,195 |

|

Rhode Island |

0 |

0 |

2,415 |

5 |

2,093 |

|

South Carolina |

0 |

634,594 |

130,051 |

32,339 |

78,332 |

|

South Dakota |

275,336 |

2,006,214 |

206,930 |

148,010 |

3,515 |

|

Tennessee |

0 |

722,057 |

54,338 |

359,197 |

145,770 |

|

Texas |

12,188 |

757,036 |

574,956 |

1,206,489 |

680,529 |

|

Utah |

22,787,881 |

8,192,893 |

110,567 |

2,097,860 |

78,420 |

|

Vermont |

0 |

410,654 |

34,195 |

9,836 |

11,203 |

|

Virginia |

805 |

1,668,369 |

132,201 |

306,393 |

265,848 |

|

Washington |

437,342 |

9,335,431 |

163,791 |

1,834,616 |

421,675 |

|

West Virginia |

0 |

1,046,426 |

19,888 |

65,554 |

2,270 |

|

Wisconsin |

2,488 |

1,524,576 |

202,424 |

61,835 |

62,762 |

|

Wyoming |

17,493,875 |

9,215,971 |

70,930 |

2,345,619 |

11,327 |

|

U.S. Total |

244,391,312 |

192,919,130 |

89,205,999 |

79,945,679 |

8,849,476 |

|

Territories |

0 |

28,937 |

24,773 |

26,852 |

59,058 |

|

Overseas |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12,816 |

|

Agency Total |

244,391,312 |

192,948,059 |

89,230,772 |

79,972,531 |

8,921,349 |

Sources: For BLM, data provided to CRS by BLM on December 16, 2019. Data reflect BLM ownership as of September 30, 2018.

For FS: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Land Areas of the National Forest System—As of Sept 30, 2018, Tables 1 and 4, at https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/LAR2018/lar2018index.html. Data reflect land within the National Forest System, including national forests, national grasslands, purchase units, land utilization projects, experimental areas, and other areas. Table I shows an agency total of 192,948,059. However, the individual state and territory acreages copied here from Table 4 appear to sum to 192,948,067. The reason for the discrepancy is not apparent. In this table, the agency total is reflected as the total reported in Table I, 192,948,059.

For FWS: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, 2018 Annual Lands Report Data Tables, as of September 30, 2018, Table 1A, at https://www.fws.gov/refuges/land/PDF/2018_Annual_Report_of_Lands_Data_Tables.pdf. Data reflect federally owned land over which the FWS has sole or primary jurisdiction.

For NPS: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Land Resources Division, Acreage by State, as of 9/30/2018, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/lwcf/upload/NPS-Acreage-9-30-2018.pdf. Data reflect federally owned lands managed by the NPS.

For DOD: U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Infrastructure, Base Structure Report, Fiscal Year 2018 Baseline (A Summary of the Real Property Inventory Data), as of September 30, 2017, VI. Total DOD Inventory, pp. DOD-29 to DOD-88, at https://www.acq.osd.mil/eie/Downloads/BSI/Base%20Structure%20Report%20FY18.pdf. Hereinafter this source is referred to as the DOD FY2018 Baseline. Unlike the data for the other agencies, the DOD data is current as of September 30, 2017. The source excludes U.S. Army Corps of Engineers lands.

Notes: See notes for Table 1.

a. This figure includes approximately 253,000 acres of submerged lands and waters within the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

|

|

Source: Map boundaries and information generated by CRS using federal lands GIS data from the National Atlas, 2005, and an ESRI USA Base Map. Notes: Scale 1:11,283,485. The line along the coast of California indicates BLM administration of numerous small islands. Also, the map may reflect a broader definition of DOD land than shown in the data in Table 2. |

|

|

Source: Map boundaries and information generated by CRS using federal lands GIS data from the National Atlas, 2005, and an ESRI USA Base Map. Note: Scale 1:13,293,047. Also, the map may reflect a broader definition of DOD land than shown in the data in Table 2. |

|

Figure 3. Federal Lands in Alaska and Hawaii Managed by Five Agencies |

|

|

Source: Map boundaries and information generated by CRS using federal lands GIS data from the National Atlas, 2005, and an ESRI USA Base Map. Note: Hawaii scale 1:8,000,000. Alaska scale 1:20,000,000. Also, the map may reflect a broader definition of DOD land than shown in the data in Table 2. |

Federal Land Ownership Changes, 1990-2018

Since 1990, total federal lands in the United States have generally declined. Many disposals of areas of federal lands have occurred. At the same time, the federal government has acquired many parcels of land, and there have been various new federal land designations, including wilderness areas and national park units. Through the numerous individual acquisitions and disposals since 1990, the total federal land ownership has declined by 31.5 million acres, or 4.9% of the total of the five agencies, as shown in Table 3.

The total acreage decline reflects decreased acreage for two agencies but increased acreage for three others. BLM ownership decreased by 27.6 million acres (10.2%), in large part due to the disposal of BLM land, under law, to the State of Alaska, Alaska Natives, and Alaska Native Corporations.36 DOD land ownership also declined, by 11.7 million acres (56.8%). This decline was primarily due to changes in legal arrangements for managing military installations rather than changes in the sizes of the installations themselves. For instance, of the 26.9 million acres of defense sites (worldwide) in DOD's FY2018 Baseline report—more than 98% of which is in the United States or territories—8.9 million acres (33%) were federally owned,37 0.9 million acres (3%) were leased, and 17.1 million acres (63%) were managed through a legal interest that was "other" than owned or leased.38 By comparison, of the 28.4 million acres of defense sites (worldwide) in DOD's 2010 report, approximately 19.8 million (70%) were federally owned,39 0.5 million (2%) were leased, and 8.0 million (28%) were managed under another legal interest.

In contrast, the NPS, FWS, and FS expanded their acreage during the period, with the NPS having the largest increase in both acreage and percentage growth─3.8 million acres (5.0%). In some cases, a decrease in one agency's acreage was tied to an increase in acreage owned by another agency.40

|

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2018 |

Change |

% Change |

|

|

BLM |

272,029,418 |

264,398,133 |

247,859,076 |

244,391,312 |

-27,638,106 |

-10.2% |

|

FS |

191,367,364 |

192,355,099 |

192,880,840 |

192,919,130 |

1,551,766 |

0.8% |

|

FWS |

86,822,107 |

88,225,669 |

88,948,699 |

89,205,999 |

2,383,892 |

2.7% |

|

NPS |

76,133,510 |

77,931,021 |

79,691,484 |

79,945,679 |

3,812,169 |

5.0% |

|

DOD |

20,501,315 |

24,052,268 |

19,421,540 |

8,849,476 |

-11,651,839 |

-56.8% |

|

U.S. Total |

646,853,714 |

646,962,190 |

628,801,839 |

615,311,596 |

-31,542,118 |

-4.9% |

Sources: See sources listed Table 2.

Notes: See notes for Table 1. Also, estimates generally reflect the end of the fiscal year for the years shown, (i.e., September 30). However, DOD figures for the years indicated were not readily available. Rather, the DOD figures for the four columns were derived respectively from the FY1989 Base Structure Report (published in February 1988), the FY1999 Base Structure Report (with data as of September 30, 1999), the FY2010 Base Structure Report (with data as of September 30, 2009), and the FY2018 Base Structure Report (with data as of September 30, 2017).

The total federal acreage decline (shown in Table 3) is a composite of various decreases in acreage in 15 states and increases in acreage in 36 states (including the District of Columbia). A reduction in federal lands in Alaska was a major reason for the total decline in federal lands since 1990. As shown in Table 4, federal land declined in Alaska by 23.0 million acres (9.4%) between 1990 and 2018. As noted, this decline in Alaska is largely the result of the disposal of BLM land under Alaska-specific laws. Specifically, from 1990 to 2018, BLM land in Alaska declined by 21.1 million acres (22.8%).

Since 1990, federal land also has decreased in the 11 contiguous western states, by 10.7 million acres (3.0%). Reflected in the overall decline are reductions for 6 of the 11 states, with decreases of 6.3 million acres in Arizona, 3.7 million acres in Nevada,41 and smaller decreases in four other states. Five of the 11 states each had increases ranging roughly from 0.2 million acres to 0.5 million acres, with the largest being 0.5 million acres in Colorado.

Outside Alaska and the other western states, federal land increased by 2.1 million acres (4.5%). This increase was not uniform, with declines in some states and varying increases (in acreages and percentage) in others.

|

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2018 |

Change |

% Change |

|

|

Alabama |

944,505 |

979,907 |

871,232 |

880,188 |

-64,317 |

-6.8% |

|

Alaska |

245,669,027 |

237,828,917 |

225,848,164 |

222,666,580 |

-23,002,447 |

-9.4% |

|

Arizona |

34,399,867 |

33,421,887 |

30,741,287 |

28,077,992 |

-6,321,875 |

-18.4% |

|

Arkansas |

3,147,518 |

3,418,455 |

3,161,978 |

3,159,486 |

11,968 |

0.4% |

|

California |

46,182,591 |

47,490,824 |

47,797,533 |

45,493,133 |

-689,458 |

-1.5% |

|

Colorado |

23,579,790 |

24,001,922 |

24,086,075 |

24,100,247 |

520,457 |

2.2% |

|

Connecticut |

6,784 |

9,012 |

8,557 |

9,110 |

2,326 |

34.3% |

|

Delaware |

27,731 |

28,397 |

28,574 |

29,918 |

2,187 |

7.9% |

|

Dist. of Col. |

9,533 |

8,466 |

8,450 |

9,649 |

116 |

1.2% |

|

Florida |

4,344,976 |

4,671,958 |

4,536,811 |

4,491,200 |

146,224 |

3.4% |

|

Georgia |

1,921,674 |

1,933,464 |

1,956,720 |

1,946,492 |

24,818 |

1.3% |

|

Hawaii |

715,215 |

682,650 |

833,786 |

829,830 |

114,615 |

16.0% |

|

Idaho |

32,566,081 |

32,569,711 |

32,635,835 |

32,789,648 |

223,567 |

0.7% |

|

Illinois |

353,061 |

403,835 |

406,734 |

423,782 |

70,721 |

20.0% |

|

Indiana |

274,483 |

394,243 |

340,696 |

384,726 |

110,243 |

40.2% |

|

Iowa |

33,247 |

83,134 |

122,602 |

97,509 |

64,262 |

193.3% |

|

Kansas |

281,135 |

300,465 |

301,157 |

253,919 |

-27,216 |

-9.7% |

|

Kentucky |

966,483 |

1,065,814 |

1,083,104 |

1,100,160 |

133,677 |

13.8% |

|

Louisiana |

1,578,151 |

1,565,875 |

1,330,429 |

1,353,291 |

-224,860 |

-14.2% |

|

Maine |

176,486 |

210,167 |

209,735 |

301,481 |

124,995 |

70.8% |

|

Maryland |

173,707 |

190,783 |

195,986 |

205,362 |

31,655 |

18.2% |

|

Massachusetts |

63,291 |

63,998 |

81,692 |

62,680 |

-611 |

-1.0% |

|

Michigan |

3,649,258 |

3,692,271 |

3,637,965 |

3,637,599 |

-11,659 |

-0.3% |

|

Minnesota |

3,545,702 |

3,581,741 |

3,469,211 |

3,503,977 |

-41,725 |

-1.2% |

|

Mississippi |

1,478,726 |

1,544,501 |

1,523,574 |

1,552,634 |

73,908 |

5.0% |

|

Missouri |

1,666,718 |

1,676,175 |

1,675,400 |

1,702,983 |

36,265 |

2.2% |

|

Montana |

26,726,219 |

26,745,666 |

26,921,861 |

27,082,401 |

356,182 |

1.3% |

|

Nebraska |

528,707 |

556,347 |

549,346 |

546,852 |

18,145 |

3.4% |

|

Nevada |

60,012,488 |

60,180,297 |

56,961,778 |

56,262,610 |

-3,749,878 |

-6.2% |

|

New Hampshire |

734,163 |

754,858 |

777,807 |

805,472 |

71,309 |

9.7% |

|

New Jersey |

146,436 |

164,865 |

176,691 |

171,956 |

25,520 |

17.4% |

|

New Mexico |

24,742,260 |

26,829,296 |

27,001,583 |

24,665,774 |

-76,486 |

-0.3% |

|

New York |

215,441 |

229,097 |

211,422 |

230,992 |

15,551 |

7.2% |

|

North Carolina |

2,289,509 |

2,415,560 |

2,426,699 |

2,434,801 |

145,292 |

6.3% |

|

North Dakota |

1,727,541 |

1,729,430 |

1,735,755 |

1,733,641 |

6,100 |

0.4% |

|

Ohio |

234,396 |

289,566 |

298,500 |

305,502 |

71,106 |

30.3% |

|

Oklahoma |

505,898 |

696,377 |

703,336 |

683,289 |

177,391 |

35.1% |

|

Oregon |

32,062,004 |

32,703,212 |

32,665,430 |

32,244,257 |

182,253 |

0.6% |

|

Pennsylvania |

611,249 |

598,165 |

616,895 |

622,160 |

10,911 |

1.8% |

|

Rhode Island |

3,110 |

4,867 |

5,248 |

4,513 |

1,403 |

45.1% |

|

South Carolina |

891,182 |

872,173 |

898,637 |

875,316 |

-15,866 |

-1.8% |

|

South Dakota |

2,626,594 |

2,642,646 |

2,646,241 |

2,640,005 |

13,411 |

0.5% |

|

Tennessee |

980,416 |

1,251,514 |

1,273,974 |

1,281,362 |

300,946 |

30.7% |

|

Texas |

2,651,675 |

2,855,997 |

2,977,950 |

3,231,198 |

579,523 |

21.9% |

|

Utah |

33,582,578 |

34,982,884 |

35,033,603 |

33,267,621 |

-314,957 |

-0.9% |

|

Vermont |

346,518 |

428,314 |

453,871 |

465,888 |

119,370 |

34.4% |

|

Virginia |

2,319,524 |

2,381,575 |

2,358,071 |

2,373,616 |

54,092 |

2.3% |

|

Washington |

11,983,984 |

12,646,137 |

12,173,813 |

12,192,855 |

208,871 |

1.7% |

|

West Virginia |

1,062,500 |

1,096,956 |

1,130,951 |

1,134,138 |

71,638 |

6.7% |

|

Wisconsin |

1,980,460 |

2,006,778 |

1,865,374 |

1,854,085 |

-126,375 |

-6.4% |

|

Wyoming |

30,133,121 |

30,081,046 |

30,043,513 |

29,137,722 |

-995,399 |

-3.3% |

|

U.S. Total |

646,853,714 |

646,962,190 |

628,801,639 |

615,311,596 |

-31,542,118 |

-4.9% |

Current Issues

Since the cession to the federal government of the western lands by several of the original 13 states, many federal land issues have recurred. The extent of ownership continues to be debated. Some advocate disposing of federal lands to state or private ownership; others favor retaining currently owned lands; still others promote land acquisition by the federal government, including through increased or more stable funding sources. Another focus is on the condition of federal lands and related infrastructure. Some assert that lands and infrastructure have deteriorated and that agency activities and funding should focus on restoration and maintenance, whereas others advocate expanding federal protection to additional lands. Debates also encompass the extent to which federal lands should be developed, preserved, and open to recreation and whether federal lands should be managed primarily to produce national benefits or benefits primarily for the localities and states in which the lands are located. Finally, border security, along and near the southwestern border in particular, raises questions related to management of, and access to, federal lands. These questions stem, in part, from the differing roles of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the federal land management agencies.42

Extent of Ownership

The optimal extent of federal land ownership is an enduring issue for Congress. Current debates encompass the extent to which the federal government should dispose of, retain, or acquire lands in general and in particular areas. Advocates of retention of federal lands, and federal acquisition of additional lands, assert a variety of benefits to the public of federal land ownership. They include protection and preservation of unique natural and other resources; open space; and public access, especially for recreation. Some support land protection from development.

Disposal advocates have expressed concerns about the efficacy and efficiency of federal land management, accessibility of federal lands for certain types of recreation, and limitations on development of federal lands. Some support selling federal land for financial reasons, such as to help lower federal expenditures, reduce the deficit, or balance the budget. Others assert that limited federal resources constrain agencies' abilities to protect and manage the lands and resources. Other concerns involve the potential influence of federal land protection on private property, development, and local economic activity. Some seek disposal to states or private landowners to foster state, local, and private control over lands and resources.

Other issues center on the suitability of authorities for acquiring and disposing of lands and their use in particular areas. Congress has provided to the federal agencies varying authorities for acquiring and disposing of land.43 With regard to acquisition, the BLM has relatively broad authority, the FWS has various authorities, and the FS authority is mostly limited to lands within or contiguous to the boundaries of a national forest. DOD also has authority for acquisitions.44 By contrast, the NPS has no general authority to acquire land to create new park units. Condemnation for acquiring land is feasible, but, with the exception of DOD, rarely is used by these agencies. Its potential use has been controversial in some cases. The primary funding mechanism for federal land acquisition, for the four major federal land management agencies, has been appropriations from the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF).45 For the FWS, the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund (supported by sales of Duck Stamps and import taxes on arms and ammunition) provides an additional source of mandatory spending for land acquisition. Funding for acquisitions by DOD is provided in DOD appropriations laws. There continue to be different views as to acquisition funding, including the appropriate amount, type (discretionary and/or mandatory), and location of use.

With regard to disposal, the NPS and FWS have no general authority to dispose of the lands they administer, and the FS disposal authorities are restricted. The BLM has broader authority under provisions of FLPMA.46 DOD lands that are excess to military needs can be disposed of under the surplus property process administered by the General Services Administration (GSA). While surplus DOD real property is routinely disposed of by the GSA, legislation authorizing base realignment and closure (BRAC) rounds typically has authorized the Secretary of Defense to exercise GSA's disposal authority during BRAC rounds.47

It is not uncommon for Congress to enact legislation providing for the acquisition or disposal of particular lands where an agency lacks such authority or providing particular procedures for specified land transactions. Further, recent Congresses have considered measures to establish or amend broader authorities for acquiring or disposing of land.

Western Land Concentration

The concentration of federal lands in the West has contributed to a higher degree of controversy over federal land ownership in that part of the country. For instance, the dominance of BLM and FS lands in the western states has led to various efforts to divest the federal government of significant amounts of land. In recent years, some western states, among others, have considered measures to provide for or express support for the transfer of federal lands to states, to establish task forces or commissions to examine federal land transfer issues, and to assert management authority over federal lands. An earlier collection of efforts from the late 1970s and early 1980s, known as the Sagebrush Rebellion, also sought to foster divestiture of federal lands. However, that effort was not successful in achieving this end through legal challenges in the federal courts and efforts to persuade the Reagan Administration and Congress to transfer the lands to state or private ownership. Some supporters of continued or expanded federal land ownership have asserted that state and local resource constraints, other economic considerations, or environmental or recreational priorities weigh against state challenges to federal land ownership. In recent years, some states have considered measures to express support for federal lands or to limit the sale of federal lands in the state.48

As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, the 11 contiguous western states and Alaska have extensive areas of federal lands. Table 5 summarizes the data in Table 1 to clarify the difference in the extent of federal ownership between western and other states. As can be seen in Table 5, 60.9% of the land in Alaska is federally owned, which includes 85.9% of the total FWS lands and 65.6% of the total NPS lands. In contrast, only 0.3% of DOD-owned lands are in Alaska. Of the land in the 11 contiguous western states, 45.9% is federally owned, which includes 73.4% of total FS lands and 70.6% of total BLM lands. In the rest of the country, the federal government owns 4.1% of the lands. The FS manages the largest portion of this land in other states—61.8%—and BLM manages the least—0.8%. Slightly more than half (51%) of DOD lands are in the other states, with slightly less than half (49%) in the 11 western states.

|

Alaska |

11 Western |

Other |

U.S. Total |

|

|

BLM |

71,397,880 |

172,621,231 |

372,201 |

244,391,312 |

|

FS |

22,138,560 |

141,519,920 |

29,260,650 |

192,919,130 |

|

FWS |

76,649,320 |

6,456,051 |

6,100,632 |

89,205,999 |

|

NPS |

52,455,308 |

20,403,299 |

7,087,074 |

79,945,679 |

|

DOD |

25,512 |

4,313,759 |

4,510,205 |

8,849,476 |

|

U.S. Total |

222,666,580 |

345,314,260 |

47,330,762 |

615,311,596 |

|

Acreage of States |

365,481,600 |

752,947,840 |

1,152,913,920 |

2,271,343,360 |

|

Percentage Federal |

60.9% |

45.9% |

4.1% |

27.1% |

Sources: For federal lands, see sources listed in Table 2. Total acreage of states is from U.S. General Services Administration, Office of Governmentwide Policy, Federal Real Property Profile, as of September 30, 2004, Table 16, pp. 18-19.

Notes: See notes for Table 1. As mentioned, the U.S. total shown is not the precise sum of the figures in the first three columns due to small discrepancies in the sources used and rounding.

a. The 11 western states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Maintaining Infrastructure and Lands

Debate continues over how to balance the acquisition of new assets and lands with the maintenance of the agencies' existing infrastructure and the care of current federal lands. Some assert that addressing the condition of infrastructure and lands in current federal ownership is paramount. They support ecological restoration as a focus of agency activities and funding and an emphasis on managing current federal lands for continued productivity and public benefit. They oppose new land acquisitions and unit designations until the backlog of maintenance activities has been eliminated or greatly reduced and the condition of current range, forest, and other federal lands is significantly improved. Others contend that expanding federal protection to additional lands is essential to provide new areas for public use, protect important natural and cultural resources, and respond to changing land and resource conditions.

The ecological condition of current federal lands has long been a focus of attention. For example, the poor condition of public rangelands due to overgrazing was the rationale for enacting the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 and the creation of the BLM.49 Today, debates on the health and productivity of federal lands center on rangelands, forests, riparian areas, and other resources. These lands and resources might be affected in some areas by various land uses, such as livestock grazing, recreation, and energy development. Many other variables might impact the health of federal lands and resources, including wildfires, community expansion, invasive weeds, and drought.

The deferred maintenance of federal infrastructure also has been a focus of Congress and the Administration for many years. Deferred maintenance, often called the maintenance backlog, is defined as maintenance that was not done when scheduled or planned. The agencies assert that continuing to defer maintenance of facilities accelerates their rate of deterioration, increases their repair costs, and decreases their value.

Congressional and administrative attention has centered on the NPS backlog. DOI estimated deferred maintenance for the NPS for FY2018 at $11.92 billion. Of the total deferred maintenance, 57% was for roads, bridges, and trails; 19% was for buildings; 6% was for irrigation, dams, and other water structures; and 18% was for other structures (e.g., recreation sites).50 DOI estimates of the NPS backlog have increased overall since FY1999, from $4.25 billion in that year.51 It is unclear what portion of the change is due to the addition of maintenance work that was not done on time or the availability of more precise estimates of the backlog. The NPS, as well as the other land management agencies, increased efforts to define and quantify maintenance needs over the past two decades.

While attention has focused on the NPS backlog, the other federal land management agencies also have maintenance backlogs. The FS estimated its backlog for FY2018 at $5.20 billion.52 Of the total deferred maintenance, 61% was for roads,53 24% was for buildings, and the remaining 15% was for a variety of other assets (e.g., trails, fences, and bridges). For FY2018, DOI estimated the FWS backlog at $1.30 billion and the BLM backlog at $0.96 billion.54 The four agencies together had a combined FY2018 backlog estimated at $19.38 billion.

The agency backlogs have been attributed to decades of funding shortfalls. However, it is unclear how much total funding has been provided for the maintenance backlog over the years. Annual presidential budget requests and appropriations laws typically have not identified funds from all sources that may be used to address the maintenance backlog. Opinions differ over the level of funds needed to address deferred maintenance, whether to use funds from other programs and new sources, and how to prioritize funds for maintenance needs.

Protection and Use

The extent to which federal lands should be opened to development, available for recreation, and/or preserved has been controversial. Differences of opinion exist on the amount of traditional commercial development that should be allowed, particularly involving energy development, grazing, and timber harvesting. Whether and where to restrict recreation, generally and for high-impact uses such as motorized off-road vehicles, also is a focus. How much land to dedicate to enhanced protection, what type of protection to provide, and who should protect federal lands are continuing questions. Another area under consideration involves how to balance the protection of wild horses and burros on federal lands with protection of the range and other land uses.

Debates also encompass whether federal lands should be managed primarily to emphasize benefits nationally or for the localities and states where the lands are located. National benefits can include using lands to produce wood products for housing or energy from traditional (oil, gas, coal) and alternative/renewable sources (wind, solar, geothermal, biomass). Other national benefits might encompass clean water for downstream uses; biodiversity for ecological resilience and adaptability; and wild animals and wild places for human enjoyment. Local benefits can include economic activities, such as livestock grazing, timber for sawmills, ski areas, tourism, and other types of development. Local benefits could also be scenic vistas and areas for recreation—picnicking, sightseeing, backpacking, four-wheeling, snowmobiling, hunting and fishing, and much more.

At some levels, the many uses and values can generally be compatible. However, as demands on the federal lands have risen, the conflicts among uses and values have escalated. Some lands—notably those administered by the FWS and DOD—have an overriding primary purpose (wildlife habitat and military needs, respectively). The conflicts typically are greatest for the multiple-use lands managed by the BLM and FS, because the potential uses and values are more diverse.

Other issues of debate include who decides the national-local balance, and how those decisions are made. Some would like to see more local control of land and a reduced federal role, while others seek to maintain or enhance the federal role in land management to represent the interests of all citizens.

Border Security55

Border security presents special challenges on federal lands, given the extensive federal lands along the southwestern border with Mexico and the northern border with Canada. The federal lands on the borders tend to be geographically remote and include mountains, deserts, and other inhospitable terrain with limited law enforcement coverage. Moreover, the lands are managed by different federal agencies, under various laws, and for many purposes.

The southwestern border with Mexico has been a particular focus. There are various estimates and depictions of federal lands on or near the border. For instance, by one estimate, six different agencies manage 621.5 (linear) miles of federal lands along the southwestern border.56 Second, a depiction of federal (and Indian) lands located within 50 and 100 miles from the U.S.-Mexican border is shown in Table 4. Third, according to the House Committee on Natural Resources, there are about 26.7 million acres of federal lands within 100 miles of the border (and an additional 3.5 million acres of Indian lands).57 Nearly half of the federal lands (12.3 million acres) are managed by the BLM, and the remainder are managed by DOD (5.8 million acres), FS (3.8 million acres), NPS (2.4 million acres), FWS (2.2 million acres), and other federal agencies (0.2 million acres).

The extent to which federal and other lands along the southwestern border should be used for the construction of barriers to deter illegal immigration and other illegal activity is under current debate. Efforts to build border infrastructure to reduce illicit activity at the border, such as illegal entry and drug and contraband smuggling, are a priority for the Trump Administration as well as for some Members of Congress and portions of the public. By contrast, some Members of Congress and segments of the public oppose barrier construction as potentially costly, possibly damaging to lands and resources, and unlikely to be a major deterrent to illegal activity, among other reasons.58

Within DHS, the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) takes the lead role in staffing and securing the international borders, but more than 40% of the southwestern border abuts federal and tribal lands overseen by the FS and the four DOI agencies (including the Bureau of Indian Affairs) that also have law enforcement responsibilities.59 Differences in missions and jurisdictional complexity among these agencies may hinder border control. To facilitate control efforts, three federal agencies—DHS, the Department of Agriculture (for the FS), and DOI—have signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) on border security. These MOUs govern information sharing, budgeting, operational planning, USBP access to federal lands, and interoperable radio communications, among other issues.60

In general, federal efforts to secure the border are subject to the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), which requires agencies to evaluate the potential environmental impacts of proposed programs, projects, and actions before decisions are made to implement them.61 Implementing regulations require agencies to integrate NEPA project evaluations with other planning and regulatory compliance requirements to ensure that planning and decisions reflect environmental considerations.62 Federal law confers the DHS Secretary with broad authority to construct barriers and roads along U.S. borders to deter illegal crossings. The Secretary may waive application of NEPA and other laws that the Secretary determines may impede the expeditious construction of these barriers and roads.63 In the past, Congress has introduced legislation to broaden DHS's authority to be exempt from NEPA, land management statutes, and other environmental laws on the grounds that these laws (and related litigation) may impede DHS from taking actions on federal lands to secure the border. Some have opposed such legislation on the grounds that it would remove important protections for sensitive and critical habitats and resources and that the current authority is already sufficiently broad.