Introduction

Paid family and medical leave (PFML) refers to partially or fully compensated time away from work for specific and generally significant family caregiving needs (paid family leave) or for the employee's own serious medical condition (paid medical leave). Family caregiving needs include those such as the arrival of a new child or serious illness of a close family member. Medical conditions that may qualify for medical leave generally must be severe enough to require medical intervention and interfere with a worker's performance of key job responsibilities. Although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA; P.L. 103-3, as amended) provides eligible workers with a federal entitlement to unpaid leave for a limited set of family caregiving needs, no federal law requires private-sector employers to provide paid leave of any kind.1

Currently, employees may access PFML if offered by an employer.2 Employers that provide paid family and medical leave may qualify for a federal tax credit. The tax credit is up to 25% of paid leave wages paid to qualifying employees.3 Qualifying employees include those whose earnings do not exceed 60% of a "highly compensated employee" threshold ($72,000 in 2018). This tax credit was first enacted as part of the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97, of commonly the "Tax Cuts and Jobs Act"). It was extended through 2020 as part of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94).

Some workers may finance unpaid absences for certain serious medical needs through short-term disability insurance. In addition, some states have created family and medical leave insurance programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who engage in certain (state-identified) family caregiving activities or who must be absent from work as a result of the worker's own significant medical needs.4 In these states, workers can finance family and medical leave by combining an entitlement to unpaid leave with state-provided insurance benefits.

Some congressional proposals seek to enhance national access to paid family and medical leave by expanding upon existing mechanisms (i.e., voluntary employer provision or financing of leave through social insurance). The Paid Family Leave Pilot Extension Act (S. 1628/H.R. 4964) proposes to support voluntary employer-provided PFML by extending the employer tax credit for such leave to December 2022, and—similar to the state insurance approach—the Family and Medical Insurance Act (FAMILY Act; S. 463/H.R. 1185) proposes to create a national wage insurance program for persons engaged in family caregiving activities or who take leave for their own serious health condition. Other proposals such as the New Parents Act (S. 920/ H.R. 1940) would allow parents of a new child to receive Social Security benefits, to be repaid at a later date, for the purposes of financing parental leave. Another set of proposals would amend the tax code to support individuals saving for their own family and medical leave purposes (e.g., the Working Parents Flexibility Act of 2019 (H.R. 1859) and the Freedom for Families Act (H.R. 2163)); the Support Working Families Act (S. 2437) would provide a parental leave tax credit to individuals taking parental leave.

Members of Congress who support increased access to paid leave generally cite as their motivation the significant and growing difficulties some workers face when balancing work and family responsibilities, and the financial challenges faced by many working families that put unpaid leave out of reach. Expected benefits of expanded access to PFML include stronger labor force attachment for family caregivers and workers experiencing serious medical issues, and greater income stability for their families; and improvements to worker morale, job tenure, and other productivity-related factors. Some studies identify a relationship between paid leave and family well-being as measured by a range of outcomes (e.g., child health, mothers' mental well-being).5 Potential costs include the financing of payments made to workers on leave, other expenses related to periods of leave (e.g., hiring a temporary replacement or productivity losses related to an absence), and administrative costs. In the case of tax incentives, there is a cost in terms of forgone federal tax revenue.6 The magnitude and distributions of costs and benefits would depend on how the policy is implemented, including the size and duration of benefits, how benefits are financed, and other policy factors.

This report provides an overview of PFML in the United States, summarizes state-level family and medical leave insurance program provisions, reviews PFML policies in other advanced-economy countries, and describes recent federal legislative action to increase access to paid family leave.

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States

Throughout their careers, many workers encounter a variety of medical needs and family caregiving obligations that conflict with work time. Some of these are broadly experienced by working families but tend to be short in duration, such as episodic child care conflicts, school meetings and events, routine medical appointments, and minor illnesses experienced by the employee or an immediate family member. Others are more significant in terms of their impact on families and the amount of leave needed, but occur less frequently in the general worker population, such as the arrival of a new child or a serious medical condition that requires inpatient care or continuing treatment. Although all these needs for leave may be consequential for working families, the term family and medical leave is generally used to describe the latter, more significant and disruptive group of needs that can require longer periods of time away from work.

As defined in recent federal proposals, family caregiving and medical needs that would be eligible for leave generally include the following:

- caring for and bonding with a newborn child or a newly-placed adopted or fostered child (i.e., a "newly-arrived child"),

- attending to the serious medical needs of certain close family members, and

- attending to the employee's own serious medical needs that interfere with the performance of his or her job duties.7

In practice, day-to-day needs for leave to attend to family matters (e.g., a school conference or lapse in child care coverage), minor illness (e.g., common cold), or preventive care are not included among family and medical leave categories.8

Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Short-Term Disability Insurance

Although federal law does not require private sector employers to provide paid family or medical leave to their employees, some employers offer such paid leave to their employees as a voluntary benefit.9 Employers can provide the paid leave directly (i.e., by continuing to pay employees during period of leave), but financing potentially-long periods of leave can be cost prohibitive in some cases. As an alternative, some employers offer short-term disability insurance (STDI) to employees to reduce wage-loss during periods of unpaid medical leave (i.e., when employees are unable to work due to a non-work-related injury or illness).10 Such policies can be purchased from private insurance companies, which pay cash benefits to covered employees when certain conditions are met.

STDI reduces wage-loss (during periods of unpaid leave) related to a covered employee's own medical needs, but does not pay benefits when an employee's absence is related to caregiving, bonding with a new child, or the family military needs that are included in some definitions of family leave. STDI benefits may be claimed for pregnancy- or childbirth related disabilities, however, and as such may be used to finance a portion of maternity leave in some circumstances.11 Family leave insurance (FLI), a newer concept, provides cash benefits to workers engaged in certain caregiving activities. Currently, FLI is not broadly available from private insurance companies.12 As a result, many employers seeking to provide leave for family caregiving must provide the leave benefit directly (i.e., offer paid family leave).

According to a national survey of employers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 18% of private-industry employees had access to paid family leave (separate from other leave categories) through their employer in March 2019.13 The BLS survey defines paid family leave as leave provided specifically to care for a family member, parental leave (i.e., for a new child's arrival), and maternity leave that is granted in addition to any sick leave, annual leave, vacation, personal leave, or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee. BLS does not collect information on employer-provided paid medical leave, but does estimate access to employer-supported STDI.14 In March 2019, 42% of private sector employees had access to STDI policies that were financed fully or in-part by their employers. STDI benefits often replace a set percentage of an employee's earnings, sometimes up to a maximum weekly benefit amount (e.g., a policy might replace 50% of earnings lost while the employee is unable to work up to $600 per week); in other cases the wage replacement rate may vary by workers' annual earnings or workers may receive a flat dollar amount (e.g., $200 per week). BLS reports that among workers who receive a fixed percentage of lost earnings (72% of those private industry workers with STDI coverage), the median fixed percentage was 60%. Of those subject to a maximum weekly benefit, the median maximum benefit was $637 per week. The median number of benefit weeks available to employees with access to STDI plans was 26 weeks.15

As shown in Table 1, employee access to employer-provided paid family leave and employer-supported STDI is not uniform across occupations and industries, and varies widely across wage groups. In particular, access was more prevalent among managerial and professional occupations; information, financial, and professional and technical service industries; high-paying occupations; full-time workers; and workers in large companies (as measured by number of employees). Announcements by several large companies suggest that access to related types of paid leave may be increasing among certain groups of workers. This is also reflected in BLS statistics which indicate a 2 percentage point increase in private sector workers' access to paid family leave between March 2018 (16%) and March 2019 (18%). The share of private sector employees with access to employer-supported STDI did not increase over that time period; it was 42% in March 2018 and March 2019. Among new company policies announced in recent years, some emphasize parental leave (i.e., leave taken by mothers and fathers in connection with the arrival of a new child), and others offer broader uses of leave.16

Table 1. Private Sector Workers with Access to Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave and Employer-Supported Short-Term Disability Insurance, March 2019

|

Category |

Employer-Provided Paid Family Leave (% of workers) |

Employer-Supported Short-Term Disability Insurance (% of workers) |

|

|

All Workers |

18% |

42% |

|

|

By Occupation |

|||

|

Management, professional, and related |

30% |

58% |

|

|

Service |

12% |

24% |

|

|

Sales and office |

18% |

41% |

|

|

Natural resources, construction, and maintenance |

11% |

35% |

|

|

Production, transportation, and material moving |

9% |

48% |

|

|

By Industry |

|||

|

Construction |

8% |

29% |

|

|

Manufacturing |

5% |

65% |

|

|

Trade, Transportation, and Utilities |

14% |

43% |

|

|

Information |

46% |

77% |

|

|

Financial Activities |

30% |

66% |

|

|

Professional and Technical Services |

34% |

57% |

|

|

Administrative and Waste Services |

6% |

19% |

|

|

Education and Health Services |

23% |

39% |

|

|

Leisure and Hospitality |

11% |

20% |

|

|

Other Services |

11% |

27% |

|

|

By Average Occupational-Wage Distribution |

|||

|

Bottom 25% |

8% |

18% |

|

|

Second 25% |

17% |

42% |

|

|

Third 25% |

20% |

53% |

|

|

Top 25% |

30% |

63% |

|

|

By Hours of Work Status |

|||

|

Full-time |

21% |

51% |

|

|

Part-time |

8% |

17% |

|

|

By Establishment Size |

|||

|

1 to 99 employees |

14% |

32% |

|

|

100 to 499 employees |

18% |

48% |

|

|

500 or more employees |

29% |

64% |

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2019 Employee Benefits Survey, September 2019, Table 16 (insurance) and Table 31 (paid leave).

Notes: The BLS survey defines paid family leave as leave "granted to an employee to care for a family member and includes paid maternity and paternity leave. The leave may be available to care for a newborn child, an adopted child, a sick child, or a sick adult relative. Paid family leave is given in addition to any sick leave, vacation, personal leave, or short-term disability leave that is available to the employee." The BLS survey defines short-term disability plans as those that "provide benefits for non-work-related illnesses or accidents on a per-disability basis, typically for a 6-month to 12-month period. Benefits are paid as a percentage of employee earnings or as a flat dollar amount. Short-term disability insurance (STDI) benefits vary with the amount of predisability earnings, length of service with the establishment, or length of disability." An employer that makes a full or partial payment towards a STDI plan is considered by BLS to provide employer-supported STDI . If there is no employer contribution to the plan (i.e., if it is entirely employee-financed), then such an insurance plan is not considered to be employer-supported STDI. Employees may also be able to use other forms of paid leave not shown in this table (e.g., vacation time), or a combination of them, to provide care to a family member or for their own medical needs.

A 2017 study by the Pew Research Center (Pew) examined U.S. perceptions of and experiences with paid family and medical leave and provides insights into the need for such leave among U.S. workers and its availability for those who need it.17 Pew reports, for example, that 27% of persons who were employed for pay between November 2014 and November 2016 took leave (paid and unpaid) for family caregiving reasons or their own serious health condition over that time period, and another 16% had a need for such leave but were not able to take it.18 Among workers who were able to use leave, 47% received full pay, 36% received no pay, and 16% received partial pay. Consistent with BLS data, the Pew study indicates that lower-paid workers have less access to paid leave; among leave takers, 62% of workers in households with less than $30,000 in annual earnings reported they received no pay during leave, whereas this figure was 26% among those with annual household incomes at or above $75,000.

The Pew survey reveals differences in access to family and medical leave across demographic groups. For example, 26% of black workers and 23% of Hispanic workers indicated that there was a time in the two years before the interview they needed or wanted time off (paid or unpaid) for family or medical reasons and were not able to take it; by contrast 13% of white workers reported they were unable to take such leave. Relatedly, among those who did take leave, Hispanic leave-takers were more likely than black or white workers to report they took leave with no pay.19

State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Short-Term Disability Insurance Programs

Some states have enacted legislation to create state leave insurance programs, which provide cash benefits to eligible workers who to take time away from work to engage in certain caregiving activities and for qualifying health reasons (Table 2). As of February 2020, five states—California, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington—have active programs. Four additional programs—those in Connecticut, the District of Columbia (DC), Massachusetts, and Oregon—await implementation.20

The first four states to offer family leave insurance (FLI)—California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island—did so by building upon existing state STDI programs (i.e., that provide benefits to workers absence from work due to significant health condition). As a result, these programs tend to offer separate entitlements to FLI benefits and STDI benefits. (To simplify the discussion, the terms STDI and medical leave insurance (MLI) benefits are used interchangeably in this section.21) For example, eligible California workers may take up to 52 weeks of MLI and up to 6 weeks FLI. By contrast, newer programs tend to offer a total amount of annual benefit weeks to workers, who may allocate them across the various needs categories (e.g., caregiving needs, medical needs) with some states capping the maximum amount that can be allocated to a single category. For example, Washington provides a total of 16 benefit weeks per year, of which up to 12 weeks of benefits may be claimed for FLI, and up to 12 weeks of benefits for MLI.22 All states included in Table 2 offer (or will offer) FLI benefits through their programs to eligible individuals who take leave from work for the arrival of a new child by birth or placement, to care for close family members with a serious health condition; some states provide family leave insurance in other circumstances.23

Table 2 summarizes key provisions of state leave insurance laws, and shows the following:24

- Benefit Duration: The maximum weeks of insurance benefits available to workers vary across states. Existing state programs offer between 26 weeks (New York) and 52 weeks (California) in 2020, but most weeks of benefits are set aside for MLI in these states. States that will implement their programs in July 2020 or later tend to offer fewer total weeks of benefits—the range will be 8 total (DC) to 25 total (Massachusetts), but generally allow workers to take more weeks of FLI benefits than do existing programs.

- Benefit Amount: Weekly benefits amounts in existing programs vary around 60-70% of the employee's average weekly earnings, with some exceptions, and all states cap benefits at a maximum weekly amount. Most states with leave insurance programs have or plan to have a progressive benefit formula.

- Eligibility: Program eligibility typically involves in-state employment of a minimum duration, minimum earnings in covered employment, or contributions to the insurance funds.

- Financing: All programs are financed through payroll taxes, with some variation in how taxes are allocated between employers and employees.

|

State Program |

Weeks of Insurance Benefits Availablea |

Benefit Formula and Maximum Weekly Benefitb |

Earnings and Employment Requirementsc |

Financing |

|

California |

52 weeks total, of which up to 6 weeks of leave insurance (FLI) may be claimed for

Starting in January 2021, workers with certain needs related to the military deployment of a close family member may qualify for FLI benefits. Up to 52 weeks of short-term disability insurance (STDI) benefits may be claimed for the employee's own temporary disability. In July 2020, up to 8 weeks may be FLI benefits. |

For workers with average weekly wages (AWWs) less than one-third of the state AWW, FLI and STDI benefits are 70% of the worker's AWWs. In general, when a worker's AWWs are one-third of the state AWW or more, benefits are calculated as 60% of the worker's AWWs, up to a maximum amount ($1,300 per week in 2020) |

The worker must have earned $300 in wages in California that were subject to the state STDI/FLI payroll tax over the worker's base period.d |

Payroll tax on employees. |

|

Connecticut (Benefits payable in January 2022) |

12 weeks total, which may be claimed for the following family and medical leave events:

2 additional weeks of benefits may be claimed for a serious health condition if an employee's pregnancy results in incapacitation, bringing total benefits to 14 weeks in such cases. |

Starting in January 2022, workers receive 95% of the portion of their AWW that is less than or equal to the earnings from a 40 hour workweek compensated at the CT minimum hourly wage plus 60% of the portion of their AWW that is above this threshold, up to a maximum amount. The maximum weekly benefit is to be set at 60 times the CT minimum wage. |

Benefit recipients must have earnings of at least $2,325 in the highest earning quarter within the base period.d They must also be currently or recently employed (i.e., employed in the last 12 weeks). |

Payroll tax on employees. |

|

District of Columbia (Benefits payable in July 2020) |

8 weeks total, of which up to

|

Starting in July 2020, benefits are 90% of the portion of a worker's AWW that is 150% or less of 40 hours compensated at the DC minimum wage (i.e., "150% of the DC minimum weekly wage"), plus 50% of average earnings above 150% of the DC minimum weekly wage, up to a maximum weekly amount ($1,000 per week in 2020). |

The worker must have worked for at least one week in the 52 calendar weeks preceding the qualifying event for leave for a covered DC-based employer, and at least 50% of that work must occur in DC for such a DC-based employer. |

Payroll tax on covered employers. |

|

Massachusetts (Benefits payable in January 2021) |

25 weeks totale, of which up to 12 weeks of FLI benefits may be claimed for

and up to 25 weeks of FLI benefits may be claimed for the care of a military family member with a serious illness or injury. Up to 20 weeks of medical leave insurance (MLI) may be claimed for the employee's own serious health condition. |

Starting in January 2021, workers receive 80% of the portion of their AWW that is 50% or less of the state AWW; they receive 50% of the portion of their AWW that is above 50% of the state AWW, up to a maximum amount ($850 per week in 2021). |

The worker meets the financial eligibility requirements for receiving unemployment insurance (i.e., in 2020, the worker would have had to have earned at least $5,100 in the last 4 completed calendar quarters). |

FLI is financed through a payroll tax on employees. MLI is financed through a payroll tax on employers and employees. Employers with fewer than 25 employees are exempt from payroll tax contributions. |

|

New Jersey |

32-52 weeks totalf, of which up to six weeks (or 42 intermittent days) may be claimed for the FLI events:

Up to 26 weeks of STDI benefits may be claimed for an employee's own temporary disability, for a single period of disability. Starting in July 2020, up to 12 weeks (or 56 intermittent days) may be claimed for FLI events. |

Approximately 67% of the worker's AWW, up to a maximum amount ($667 per week from January 1 to June 30, 2020). Starting July 1, 2020, benefits will be 85% of the worker's AWW, up to a maximum amount equal to 70% of the statewide AWW ($881 per week starting July 1, 2020). |

The worker meets the financial eligibility requirements for unemployment insurance. In 2020, these are 20 or more calendar weeks with earnings of $200 in each week in the base period, or at least $10,000 in earnings during the base period.d |

FLI is financed through a payroll tax on employees. STDI is financed through a payroll tax on employers and employees. |

|

New Yorkg (FLI program to be fully implemented in 2021) |

26 weeks total, of which up to 10 weeks of FLI benefits may be claimed for

and up to 26 weeks of STDI benefits may be claimed for an employee's own temporary disability. In 2021, up to 12 weeks may be claimed for FLI benefits. |

For FLI benefits, 60% of the employee's AWW, up to a maximum amount ($840.70 per week in 2020). In 2021, the wage replacement rate will rise to 67%. For STDI benefits, 50% of the employee's AWW, up to a maximum amount ($170 per week in 2020). |

For FLI benefits, workers must have full-time employment (20 or more hours per week) for 26 consecutive weeks or 175 days (which need not be consecutive) of part-time employment. For STDI benefits, workers must have worked for a covered employer for at least 4 consecutive weeks. |

FLI is financed through a payroll tax on employees. STDI is financed through a payroll tax on employees and contributions by employers. Employers finance all insurance policy costs beyond what they are permitted by law to collect from employees. |

|

Oregon (Benefits payable in January 2023) |

12 weeks total, which may be claimed for the following family and medical leave events:

2 additional weeks of benefits may be claimed for certain medical conditions related to pregnancy, childbirth, and recovery (including lactation), bringing total benefits to 14 weeks in such cases. |

Starting in January 2023, workers receive 100% of the portion of their AWW that is 65% or less of the state AWW; they receive 50% of the portion of their AWW that is above 65% of the state AWW, up to a maximum amount. The maximum benefit formula is 120% of the state AWW. |

$1,000 in earnings during the base period.d |

Payroll tax on employers and employees. Employers with fewer than 25 employees are not required to contribute, but may do so voluntarily and by doing so may qualify for state assistance. |

|

Rhode Island |

30 weeks total, of which up to 4 weeks may be claimed for the FLI events:

and up to 30 weeks of STDI benefits may be claimed for the employee's own temporary disability. |

4.62% of wages received in the highest quarter of the worker's base period (i.e., approximately 60% of weekly earnings), up to a maximum weekly amount ($867 per week in 2020). |

The worker must have earned wages in Rhode Island, paid into the insurance fund, and received at least $12,600 in the base period;d a separate set of criteria may be applied to persons earning less than $12,600. |

Payroll tax on employees. |

|

Washington |

16 weeks total, of which up to 12 weeks of FLI benefits may be claimed for

and up to 12 weeks of MLI benefits for an employee's own serious health condition. 2 additional weeks of MLI benefits may be claimed if an employee's pregnancy results in incapacitation, bringing total benefits to 18 weeks in such cases. |

Workers whose AWW is 50% or less than the state AWW receive 90% of their AWW. Otherwise, workers receive approximately 25% of the state average weekly rate plus 50% of their AWW, up to a maximum amount ($1,000 per week in 2020). |

The worker must have worked 820 hours or more in the qualifying period.d

|

FLI is financed through a payroll tax on employees. MLI is financed through a payroll tax on employers and employees. Employers with fewer than 50 employees are not required to contribute, but may do so voluntarily and by doing so may qualify for state assistance. |

Source: California: California Unemployment Insurance Code §§2601-3307 and program information from http://www.edd.ca.gov/Disability/. Connecticut: Connecticut Public Act 19-25, An Act Concerning Paid Family and Medical Leave, available from https://www.cga.ct.gov/2019/ACT/pa/pdf/2019PA-00025-R00SB-00001-PA.pdf. District of Columbia: D.C. Official Code § 32-541.01 et seq. and program information from https://does.dc.gov/page/district-columbia-paid-family-leave. Massachusetts: MGL c.175M as added by St. 2018, c.121, and program information from https://www.mass.gov/orgs/department-of-family-and-medical-leave . New Jersey: N.J. Stat. Ann. §43:21-25 and program information from https://myleavebenefits.nj.gov/. New York: New York Workers' Compensation Law §§200-242 and program information from http://www.wcb.ny.gov/content/main/offthejob/db-overview.jsp and https://www.ny.gov/programs/new-york-state-paid-family-leave. Rhode Island: Rhode Island General Laws §§28-39-1–28-41-42 and program information from http://www.dlt.ri.gov/tdi/. Oregon: Enrolled House Bill 2005, 80th Oregon Legislative Assembly, 2019 Regular Session, available from https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2017R1/Downloads/MeasureDocument/HB2005/Enrolled. Washington: Rev. Code Washington §§ 50A.04.005 to 50A.04.900 and program information from https://paidleave.wa.gov/.

Notes: This table provides information on state programs that provide for family leave insurance in addition to medical leave insurance or short-term disability insurance. Hawaii and Puerto Rico require employers to provide short-term disability insurance but not family leave insurance to their employees, and as such are not included.

a. All states included in this table provide FLI benefits to eligible workers who provide care to a family member with a serious health condition. The set of family members generally includes a child, parent, spouse or domestic partner, and grandparent; some states provide benefits for the care of other relatives such as grandchildren and siblings.

b. In general, individuals cannot claim STDI or medical leave insurance benefits and family leave insurance benefits for the same week.

c. In general, workers must meet earnings and employment requirements while employed by a "covered employer" or while in "covered employment." Rules vary from state to state, but these terms generally capture employment and earnings for which state STDI/FMLI program contributions were collected.

d. For California, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Oregon the "base period" or "qualifying period" is typically the first four of the last five completed quarters that precede the insurance claim. For example, a claim filed on February 6, 2017, is within the calendar quarter that begins on January 1, 2017 (i.e., the first calendar quarter). The base period for that claim is the four-quarter period (i.e., 12-month period) that starts on October 1, 2015. In Massachusetts, the base period is the last four completed quarters preceding the benefit claim. In Washington, it is either the first four of the last five completed quarters or the last four completed quarters that precede the insurance claim.

e. Massachusetts law provides for up to 20 weeks of medical leave in a benefit year and 12 weeks of family leave in a benefit year, except that a covered individual taking family leave in order to provide care for a covered military family member with a serious illness or injury may use up to 26 weeks of family leave (MGL c.175M as added by St. 2018, c.121., Section 2(c)(1)). It provides family and medical leave benefits for those periods of leave, with the exception of the first 7 calendar days of such leave; consequently, while up to 26 weeks of leave are provided, workers may receive only 25 weeks of benefits. This interpretation is supported by regulations for the Massachusetts program at 458 CMR 2.12 Weekly Benefit Amount (7) which notes "[n]o family or medical leave benefits are payable during the first seven calendar days of an approved initial claim for benefits. The initial seven day waiting period for paid leave benefits will count against the total available period of leave in a benefit year."

f. Assuming eligibility conditions are met, 52 weeks of STDI benefits may be used for two separate but consecutive periods of disability.

g. New York differs from other states with leave insurance programs in that it provides temporary disability and family leave insurance to employees largely through a collection of private plans purchased by employers, rather than a centralized state plan. Employers also have the option of obtaining insurance through the NY State Insurance Fund, which was created by Article 6 of New York's Workers' Compensation Law, and serves to "to compete with other carriers to ensure a fair market place and to be a guaranteed source of coverage for employers who cannot secure coverage elsewhere." Additional information is at https://ww3.nysif.com/.

Some state leave insurance programs provide job protection directly to workers who receive insurance benefits, meaning that employers must allow such a worker to return to his or her job after leave (for which the employee has claimed insurance benefits) has ended. Workers may otherwise receive job protection if they are entitled to leave under (the federal) FMLA or state family and medical leave laws, and coordinate such job-protected leave with the receipt of state insurance benefits. For example, job protection does not accompany FLI/STDI benefits in California. However, California employees claiming FLI benefits may be eligible for job protection under the FMLA (federal protections), the California Family Rights Act, or the California New Parents Act (Table 3). Those claiming California leave insurance benefits for a disability related to pregnancy or childbirth may receive job protection for periods of leave under the FMLA (for up to 12 weeks) or the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (for up to 4 months). A California worker otherwise claiming benefits for a serious health condition that makes her or him unable to perform his or her job functions may be eligible for job protection under FMLA for up to 12 weeks.25

|

State |

Is Job Protection Provided for In Acts Authorizing State Leave Insurance Benefits?a |

Job Protection Provided by Other State Leave Laws |

|

California |

No |

California Family Rights Act: Provides an eligible employee up to 12 workweeks of unpaid job-protected leave during any 12-month period for the care of newly-arrived child, care of a child, parent, or spouse who has a serious health condition, or needs related to the employee's own serious health condition. Eligibility conditions are similar to the federal FMLA. California Fair Employment and Housing Act: Allows an employee disabled by pregnancy, childbirth, or a related medical condition to take up to 4 months of job-protected leave. California New Parents Act: Allows an eligible employee to take up to 12 weeks of job-protected parental leave to bond with a new child within one year of the child's birth, adoption, or foster care placement. This is different from the California Family Rights Act and the federal FMLA, which apply to employers with 50 or more employees, the California New Parents Act applies to employers with 20 or more employees. |

|

Connecticut |

No |

Connecticut Family and Medical Leave Actb: Effective January 1, 2022 (when the state's leave insurance program takes effect), provides up to 12 workweeks of unpaid job-protected leave during any 12-month period for the care of newly-arrived child, care of a family member with a serious health condition, needs related to the employee's own serious health condition, certain military family needs, and to serve as an organ or bone marrow donor. An employee is eligible for such leave after completing 90 days of employment with the current employer. |

|

District of Columbia |

No |

District of Columbia Family and Medical Leave Act: Provides up to 16 weeks of job-protected leave during any 24-month period for the care of newly-arrived child, or the care of a family member with a serious health condition, and 16 weeks in any 24-month period for needs related to the employee's own serious health condition. To be eligible, an employee must have been employed by the same employer for 1 year without a break in service have worked at least 1,000 hours during the 12-month period preceding the leave request. |

|

Massachusetts |

Yes |

Massachusetts Parental Leave Act: Provides 8 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave for the care of a newly-arrived child. To be eligible, an employee must have completed his or her probationary period (as set by the employer), which cannot exceed 3 months. The law applies to employers with a least 6 employees. |

|

New Jersey |

No |

New Jersey Family Leave Act: Provides eligible employees unpaid, job-protected leave to care for a newly-arrived child, or to care for a family member with a serious health condition. The law applies to all New Jersey employers with 30 or more employees (worldwide). To be eligible, an employee must have been employed for at least 12 months for the employer, and must have worked at least 1,000 hours in the 12 months preceding leave. New Jersey Security and Financial Empowerment Act: Provides up to 20 days of unpaid, job-protected leave in a 12-month periods for certain needs, if the employee or the employee's family member has been the victim of a domestic or sexual violence offence. The law applies to all employers with 25 or more employees. To be eligible, an employee must have been employed for at least 12 months for the employer, and must have worked at least 1,000 hours in the 12 months preceding leave. |

|

New York |

Yes for family leave insurance recipients. No for disability insurance recipients. |

N/A |

|

Oregon |

Yes, if employed by the current employer for at least 90 days before taking leave. |

Oregon Family Leave Act: Provides 12 weeks of job-protected leave within any 12-month period for the care of newly-arrived child, care of a family member with a serious health condition, needs related to the employee's own serious health condition, to care for a child who does not have a serious health condition but requires home care, and bereavement from the death of a family member. Leave for bereavement is limited to 2 weeks (of the 12 week total) per death of family member. Female employees are entitled to an additional 12 weeks of job-protected leave (in the same 12-month period) for a pregnancy- or childbirth-related disability that prevents the employee from performing any available job duties offered by her employer. Employees that take 12 weeks of leave to care for a newly arrived child may take an additional 12 weeks (in the same 12 months) for the care of a child who does not have a serious health condition but requires home care. The law applies to employers with at least 25 employees. To be eligible, an employee must have been employed by the current employer for at least 180 days prior to leave; with the exception of leave to care for a new child, the employee must have worked at least 25 hours per week during the 180-day period. Oregon Military Family Leave Act: Provides 14 days of unpaid, job-protected leave per deployment to an employee whose spouse is a military member called to active duty during a period of military conflict. The law applies to employers with at least 25 employees. To be eligible, and employee must work at least 20 hours per week for the employer, on average. |

|

Rhode Island |

Yes for family leave insurance recipients. No for disability insurance recipients. |

Rhode Island Parental and Family Medical Leave Act: Provides 13 consecutive weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave in a 2-year period for the care of a newly-arrived child, or a family member with a serious health condition. |

|

Washington |

Yes, if employed by an employer with 50 or more employees, and has worked for the employer for at least 12 months and worked at least 1,250 hours in last 12 months.c |

N/A |

Source: CRS, based on the following sources: California: California Unemployment Insurance Code §§2601-3307, California Government Code §§12945-12945.6. Connecticut: Connecticut Public Act 19-25, An Act Concerning Paid Family and Medical Leave, available from https://www.cga.ct.gov/2019/ACT/pa/pdf/2019PA-00025-R00SB-00001-PA.pdf, and Conn. Gen. Stat. §§31-55kk-qq, as amended by Public Act No. 19-25. District of Columbia: D.C. Official Code §32-541.01 et seq. and §32-501 et seq.. Massachusetts: MGL c.175M as added by St. 2018, c.121, and MGL c. 149, § 105D. New Jersey: N.J. Stat. Ann. §43:21-25, §34:11B1-16, and §34:11C1-5. New York: New York Workers' Compensation Law §§200-242. Rhode Island: Rhode Island General Laws 28-41 et seq. and 28-48 et seq.. Oregon: Enrolled House Bill 2005, 80th Oregon Legislative Assembly, 2019 Regular Session, ORS 659A.150-659A.186, and 659A.090-659A.099. Washington: Rev. Code Washington §§ 50A.04.005 to 50A.04.900.

a. This column indicates whether STDI or FMLI benefit receipt confers job protection to benefit recipients, meaning a recipient must be returned to the job held at the time of benefit application or receipt. This column does not include information on job protection provided under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA; P.L. 103-3) for employees who meet FMLA eligibility criteria, or under similar state laws.

b. Effective January 2022, Connecticut's family and medical leave law (at CT Gen. Stat. Sec 31-51ll) will provide job protection to employees who have completed at least 90 days of employment with the current employer prior to leave. This represents a change from current law which extends job protection to workers who have completed at least 12 months of employment with the current employer and 1,000 hours of service in the 12 months preceding leave.

c. Like most states listed in this table, Washington State provides an employers the option of providing leave insurance benefits to their employees through a private (or voluntary) plan. In Washington State, employees receiving leave insurance benefits through a private plan receive job protection during periods of family and medical leave if they have worked for the employer for at least nine months and 965 hours during the 12 months immediately preceding the leave.

Research on Paid Family and Medical Leave

A relatively small literature examines relationships between U.S. workers' access to and use of paid family and medical leave and related labor market and social outcomes. Much of this research emphasizes experiences and outcomes related to parental leave (i.e., leave related to the birth and care of new children), which is a subset of the broader family caregiving category. The focus on parental leave is driven in part by data availability, as the arrival of a new child is somewhat easier to observe in large-scale survey data than other family and medical events.26 Parental leave—and maternity leave in particular—is also a more prevalent and better understood workplace benefit than family caregiving or medical leave. For this reason survey respondents may be more likely to identify a reported workplace absence as maternity or paternity leave than they are to specify their use of medical leave or caregiving leave with great precision.27

Survey data generally allow a period of leave to be observed (and therefore studied) if the worker is taking leave at the time of the interview, or if the survey asks for information on past leave-taking. That is, information on leave is generally available conditional on the worker's use of such leave. Some workers may have access to workplace leave, but not take it for a variety of reasons.28 Information on workplace access to paid family and medical leave, including parental leave, in survey data is comparatively scarce, as are details of parental leave benefits (e.g., duration, eligibility conditions, and wage replacement) offered by employers. For these reasons studies of the state leave insurance programs (see the "State-Run Family Leave, Medical Leave, and Short-Term Disability Insurance Programs" section of this report) form an important branch of research for U.S. workers. The parameters of these programs are clearly established in state laws (See Table 2). In addition, the broad coverage of these programs and, in some cases, the availability of administrative data provide methodological advantages over studies of workers with employer-provided leave.29

Research on Paid Parental Leave in California

California launched the first state family leave insurance program in the country in 2004, building upon its existing temporary disability insurance program, and currently is the most studied.30 Research findings indicate that greater access to paid family leave (i.e., through the California program) resulted in greater leave-taking among workers with new children, with some evidence that the increase in leave-taking was particularly pronounced among women who are less educated, unmarried, or nonwhite.31 Although the program has been associated with greater leave-taking—in terms of incidence and duration of leave—for mothers and fathers, there is some indication that some workers are not availing themselves of the full six-week entitlement offered by the California program, suggesting that barriers to leave-taking remain (e.g., financial constraints, work pressures, concerns about retaliation).32 One recent study observes that employer characteristics appear to matter to workers' use of the California leave insurance benefits, raising the possibility that workplace culture plays a role in workers' leave-taking decisions.33

Some studies of the California program have considered the relationship between paid parental leave and parents' (mothers especially) attachment to the labor market. In theory, the availability of such a benefit may encourage parents to stay in work prior to the birth or arrival of a child (e.g., to qualify for benefits) and, because a full separation has not occurred, facilitate the return to work. Further, if the job held prior to leave sufficiently accommodates the needs of a working parent of a young child (e.g., if work hours align with traditional child care facility hours), a parent may be more likely to return to his or her same employer, which can benefit both the worker (e.g., who avoids costly job search, and the loss of job-specific skills and benefits of company tenure) and employers (e.g., who avoid the costs of finding a replacement worker). Empirical findings are mixed, with some studies observing a positive relationship between paid parental leave and mothers' labor force attachment, and other finding little evidence of such a connection.34 Another branch of research examines linkages between paid parental leave and family well-being. These generally find positive relationships along a variety of measures (e.g., timing of children's immunizations, mothers' mental health, and breastfeeding duration).35

Economist Maya Rossin-Slater reviews the broader literature on the impacts of maternity and paid parental leave in the United States, Europe, and other high-income countries.36 She notes the wide variation in paid leave policies across countries (see "Paid Family and Medical Leave in OECD Countries" section of this report), but nonetheless offers four general observations: (1) greater access to paid leave for new parents increases leave-taking; (2) access to leave can improve labor force attachment among new mothers, but leave entitlements in excess of one year can have the opposite effect (i.e., long separations can weaken labor force attachment among mothers); (3) access to leave can improve children's well-being, but extending the length of existing entitlements does not appear to further improve child outcomes; and (4) a limited literature on U.S. state-level leave insurance programs does not reveal notable impacts (positive or negative) of these programs on employers, but further research on employers' experiences is needed.

Research on Paid Family Caregiving and Medical Leave

Fewer studies examine the social and economic impacts of paid family caregiving leave more generally (i.e., to care for a seriously ill or injured family member) or paid medical leave, despite the prevalence of such leave among U.S. workers.37 In addition to data availability issues noted earlier in this section, the wide variety of needs encompassed by these types of leave create additional methodological hurdles. For example, the impacts of medical leave (or caregiving leave) for workers and for their employers may differ if leave is used rarely (e.g., to recover from a routine surgical procedure) than for a chronic ailment. Medical leave needs can also vary in terms of duration, further complicating efforts to establish generalizable findings.

Nonetheless, the introduction of broad-coverage state leave insurance programs creates the potential for additional research in these areas. For example, one study asked whether greater access to paid caregiving leave through the California and New Jersey state programs increased leave taking among those likely to provide elder care.38 The study found no such increase, and offered that a low levels of awareness among employed caregivers may explain the lack of response; another possibility is that the structure of the state leave insurance benefits (e.g., definition of caregiving, timing and duration of leave, employer notice requirements, lack of job protection) do not meet the needs of caregivers in those states.

Some insights to the potential impacts of paid medical leave, as defined in federal proposals, can be gained from research on the social and economic impacts of paid sick leave.39 For example, one study found that access to paid sick leave is associated with lower (involuntary) job separation rates.40 By extension, one might speculate that access to paid medical leave may have similar impacts on job stability. Some caution is warranted however, in directly applying the results of paid sick leave studies to medical leave. Research on paid sick leave will likely capture the impacts of relatively short period of leave (e.g., less than one week), as well as the effects of preventative care and absences for minor illness and injury. Paid medical leave, by definition, does not include preventative care, and tends to allow for several weeks of leave.

Paid Family and Medical Leave in OECD Countries

Many advanced-economy countries entitle workers to some form of paid family leave. Whereas some provide leave to employees engaged in family caregiving (e.g., of parents, spouse, and other family members), many emphasize leave for new parents, mothers in particular.

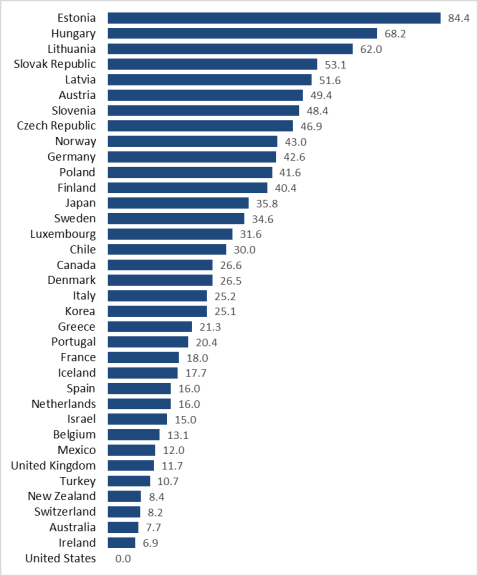

As of April 2018, The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Family Database counts 34 of its 35 members as providing some paid parental leave (i.e., to care for children) and maternity leave, with wide variation in the number of weeks and rate of wage replacement across countries. This is shown in Figure 1, which plots the OECD's estimates of weeks of full-wage equivalent leave available to mothers. The leave summarized in this Figure includes maternity leave and leave provided to mothers to care for children. Weeks of full-wage equivalent leave are calculated as the number of weeks of leave available multiplied by the average wage payment rate. For example, a country that offers 12 weeks of leave at 50% pay would be said to offer 6 full-wage equivalent weeks of leave (i.e., 12 weeks x 50% = 6 weeks).

|

Figure 1. Average Full-Wage Equivalent Weeks of Paid Leave Available to Mothers OECD Member Countries' Leave Provisions as of April 2018 |

|

|

Source: OECD, Family Database, Indicator Table PF2.1.A, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm. Notes: Leave available to mothers includes maternity leave and leave provided to care for children. Average full-wage equivalent weeks are calculated by the OECD as the product of the number of weeks of leave and "average payment rate," which describes the share of previous earnings replaced over the period of paid leave for "a person earning 100% of average national (2014) earnings." While federal law in the United States does not provide paid parental leave for private sector workers, some employers provide such leave voluntarily and some states have programs that provide wage insurance to workers on leave for selected family reasons; see the "Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States" section of this report for additional information. |

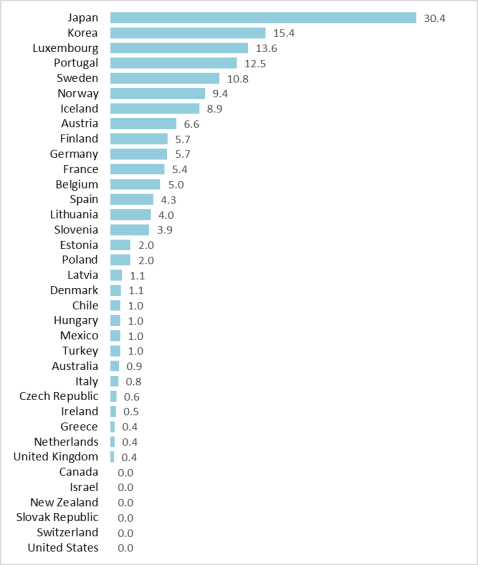

A smaller majority (27 of 35) of OECD countries provides leave benefits to new fathers. In some cases, fathers are entitled to less than a week of leave, often at full pay (e.g., Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands), whereas others provide several weeks of full or partial pay (e.g., Portugal provides five weeks at full pay, and the United Kingdom provides two weeks at an average payment rate of 20.2%). Some countries provide a separate entitlement to fathers for child caregiving purposes. This type of parental leave can be an individual entitlement for fathers or a family entitlement that can be drawn from by both parents. In the latter case, some countries (e.g., Japan, Luxembourg, and Finland) set aside a portion of the family entitlement for fathers' use, with the goal of encouraging fathers' participation in caregiving. Figure 2 summarizes paid leave entitlements reserved for fathers in OECD countries in 2018; it plots the OECD's estimates of weeks of full-wage equivalent of combined paternity leave and parental leave reserved for fathers.

|

Figure 2. Average Full-Wage Equivalent Weeks of Paid Leave Available to Fathers OECD Member Countries' Leave Provisions as of April 2018 |

|

|

Source: OECD, Family Database, Indicator Table PF2.1.B, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm. Notes: Leave available to fathers includes paternity leave and leave reserved for fathers to care for children. Average full-wage equivalent weeks are calculated by the OECD as the product of the number of weeks of leave and "average payment rate," which describes the share of previous earnings replaced over the period of paid leave for "a person earning 100% of average national (2014) earnings." While federal law in the United States does not provide paid parental leave for private sector workers, some employers provide such leave voluntarily, and some states have programs that provide wage insurance to workers on leave for selected family reasons; see the "Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States" section of this report for additional information. |

Table 4 summarizes paid family caregiving leave policies in selected OECD member countries as of June 2016.41 Most OECD countries provide for paid caregiving leave, but qualifying needs for leave, leave entitlement durations, benefit amounts, financing mechanisms and eligibility conditions vary across member countries. For example, in some OECD countries, parents may access paid leave to care for a child below a certain age (e.g., Estonia), and in others paid caregiving leave may be used to care for a family member who is not (necessarily) a child. OECD research indicates that, in most cases, the family member concept is restricted to a child, parent, and spouse; but this is not always the case. For example, in 2015 the Netherlands expanded its concept of family member to include extended family (e.g., a grandparent) and non-family members with whom the employee has a close relationship.42 In some countries employees are fully compensated during leave (e.g., Australia), whereas in others employees receive partial wage replacement (e.g., in Canada employees on leave receive 55% of lost earnings up to a maximum weekly amount). According to a 2018 report by the World Policy Analysis Center, OECD caregiving benefits are often financed through national social insurance programs.43 In some cases financing is shared by employers and the government; in others, employers fully finance the caregiving leave.

|

Country |

Paid Caregiving Leave |

|

Australia |

Up to 10 days of leave per year to care for a sick family or household member. |

|

Austria |

Up to 2 weeks of leave per year to care for a child under the age of 12 years; up to 1 week to care for an immediate family or household member. |

|

Belgium |

Two months of leave per episode to provide palliative care to a terminally ill parent. Up to 12 months per episode of illness to care for a seriously ill family member. |

|

Canadaa |

Up to 35 weeks per year to care for a seriously ill or injured child under the age of 18 years, and up to 15 weeks to care for a seriously ill or injured adult. Up to 26 weeks to care for a person of any age who requires end-of-life care. In all cases, the individual receiving care need not be a family or household member, but the caregiver must be considered "like family" to the person receiving support. |

|

Chile |

Up to 10 days per family, per year to care for a child at serious risk of death. |

|

Czech Republic |

In general, up to 9 consecutive days per episode to care for a seriously ill household family member, or a sick (need not be seriously ill) child under the age of 10 years, or a child under the age of 10 years whose regular child care or school is closed or unavailable for certain reasons. |

|

Denmarkb |

In general, up to 52 weeks for the care of a seriously ill child under the age of 18 years whose medical conditions requires at least 12 days of hospitalization. |

|

Estonia |

Up to 14 days per family, per episode to care for a child under the age of 12 years. |

|

Finland |

Up to 4 days per episode to care for a child under the age of 10 years; benefit levels are determined by collective agreement. |

|

France |

Up to 3 years per episode to care for a child under the age of 20 years with a serious illness or disability. Up to 21 days of leave to care for a close family member or household member who is terminally ill. |

|

Germany |

Up to 10 days per child, per year (maximum of 25 days in a year, per parent) to care for a child under the age of 12 years. Up to 10 days (total per dependent family member) to care for a dependent family member with an unexpected illness. |

|

Greece |

Up to 10 days per year to care for a child with certain serious illnesses who is under the age of 18 years. |

|

Hungary |

Up to 14 days per year, per family to care for a child who is 6 to 12 years old; up to 42 days per year, per family to care for a child who is 3 to 5 years old; up to 84 days per year, per family to care for a child who is 1 to 4 years old; and unlimited days for a child under the age of 1 year. |

|

Ireland |

Up to 3 days in a 12-month period, with a maximum of 5 days in a 36-month period to care for a close family member. |

|

Israelc |

In general, up to 8 days per year may be used from the employee's sick leave entitlement to care for a child under the age of 16 years. Paid leave is extended to 18 days per year for a child with special needs, and to 90 days to provide care to a seriously ill child under the age of 16 years. In general, up to 6 days per year may be used from the employee's sick leave entitlement to care for a spouse; this may be extended to 60 days per year for the care of a seriously ill spouse. Up to 6 days per year may be used from the employee's sick leave entitlement to care for a parent over the age of 65 years. |

|

Italy |

Up to 2 years over the course of the employee's career to care for a seriously ill or disabled family member. Family members cannot use such caregiving leave concurrently. |

|

Japan |

Up to 93 days (total per dependent family member) to provide care to a seriously ill dependent family member who requires constant care for at least 2 weeks. |

|

Luxembourg |

Up to 52 weeks in a 104 week period to care for a child under the age of 15 years who is seriously or terminally ill. Up to 2 days per year, per child for a child under the age of 15 years. |

|

Netherlands |

Up to 10 days of leave to care for a sick family or household member. |

|

New Zealand |

Up to 5 days per year may be used from the employee's sick leave entitlement to care for a partner or dependent family member. |

|

Norway |

Up to 10-15 days per year (depending on family composition) to care for a child under the age of 12 years; additional days may be provided for the care of child with a severe illness. |

|

Poland |

Up to 14 days per year to care for a family member. |

|

Portugal |

For families with one child, up to 30 days per year (per family) to care for a child under the age of 12 years and up to 15 days to care or a child over the age of 12 years. In both cases, families may claim one additional day per year for each additional child in the family. |

|

Slovak Republic |

Up to 10 days per year to care for a family member. |

|

Slovenia |

Up to 15 days per episode, per family to care for a child under the age of 8 years. Up to 7 days to provide care to a co-resident family member; up to 6 additional months per family may be granted for severe illness. |

|

Spain |

Up to 2 days per episode to provide care to an ill family member. Unlimited leave is provided to care for a seriously ill child under the age of 18 years; in such cases, parents may not use leave concurrently. |

|

Sweden |

Parents may take up to 120 days per child, per year to care for a child under the age of 12 years (15 years in some cases). Up to 100 days per episode to provide care to a seriously ill family member. |

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), OECD Family Database, Indicator PF2.3 Additional Leave Entitlements of Working Parents, Table PF2.3.B, updated June 12, 2016; available from http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_3_Additional_leave_entitlements_of_working_parents.pdf.

Notes: OECD analysis was based on information drawn from several sources, including the International Labor Organization Working Conditions Laws Database; A. Koslowski, S. Blum, and P. Moss, "International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2016," 2016; European Commission, "Long-Term Care for the elderly: Provisions and providers in 33 European countries," 2012; Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC) (2015) Comparative tables; and national sources.

a. Information for Canada is from the official Government of Canada information webpage on Employment Insurance Caregiving Benefits at https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/ei/caregiving.html.

b. Information for Denmark is from the Social Security Administration, Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Europe 2018, September 2018, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/2018-2019/europe/denmark.html.

c. Per Israel sick pay law, compensated leave is available starting the second day of caregiving.

Table 5 provides summary information on OECD member countries' long-term sickness benefit policies as of September 2016, based on analysis by World Policy Analysis Center. Most OECD member countries provide for at least 6 months of sickness benefits. Among countries that provide benefit amounts that are calculated as a percentage of the employee's wages, the most frequent wage replacement rate is between 60% to 79% of a worker's usual wages. In the majority of OECD member countries, provision of the sickness benefit is shared by employers and governments, usually with an employer providing benefits for a certain number of weeks, after which benefits are paid by public funds (e.g., through a social insurance program).44

|

Maximum Benefit Durationa |

||||

|

Minimum Wage Replacement Rate |

None |

Less Than 3 Months |

At Least 3 Months, Less Than 6 months |

At Least 6 Months |

|

80%-100% |

— |

Switzerland |

— |

Chile, Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway |

|

60%-79% |

— |

— |

— |

Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Japan, Latvia, Mexico, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, The Netherlands |

|

Under 60% |

— |

Israel |

Canada, Lithuania |

Austria, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Turkey |

|

Flat rate benefitb |

— |

— |

— |

Australia, Iceland, Ireland, New Zealand, United Kingdom |

|

No benefit |

South Korea, United States |

— |

— |

— |

Source: Table created by CRS using information published by The World Policy Analysis Center at https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/maps-data/data-download.

Notes: The information in this table describes benefits available to workers employed for at least 12 months who meet financial contribution requirements, if any. Some countries condition eligibility on employment tenure with the worker's current employer.

a. Where sickness benefit durations vary within countries, World Policy Analysis Center reports the duration of benefits available to the lowest paid workers with at least one year of employment tenure. Countries in the "At least 6 months" category include those that allow benefits to continue until the medical issue is resolved; in some countries however (e.g., Australia) the open-ended benefit duration is only available if certain conditions are met. Some countries make benefits available on the first day of illness; others provide a waiting period before benefits become available.

b. A flat rate benefit indicates that workers receive the same amount regardless of salary. However, some countries with a flat benefit may reduce the benefit amount in increments that correspond with income and asset levels. Consequently, flat benefit amounts can vary across recipients.

c. Some countries provide that a range of wage replacement rates for workers on leave (e.g., wage replacement rates may be higher for low-income workers). The information in this table describes the lowest replacement rate available to workers.

Recent Federal PFML Legislation and Proposals

The overarching goal of PFML legislative activity in the 116th Congress has been to increase access to leave by reducing the costs incurred by employers and/or workers associated with providing or taking leave.45 The Paid Family Leave Pilot Extension Act (S. 1628/H.R. 4964), for example, would extend the employer tax credit for (voluntarily-provided) paid family and medical leave through December 2022.46 This tax credit is designed to encourage employers to provide paid family and medical leave to their employees by reducing the cost to employers of providing such leave; it is currently scheduled to expire at the end of 2020.

A second approach addresses costs incurred by workers taking leave. For example, the establishment of a national family and medical leave insurance program, such as that proposed in the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY Act; S. 463/H.R. 1185), would provide cash benefits to eligible individuals who are engaged in certain caregiving activities, potentially making the use of unpaid leave (e.g., as provided by FMLA or voluntarily by employers) affordable for some workers. Proposals such as the New Parents Act (S. 920/ H.R. 1940) would allow eligible new parents to receive up to three months of Social Security benefits, in return for deferring retirement (or early retirement) by a period of time determined by the Social Security Administration to cover the costs of the parental benefit.47 Other approaches include proposals to create tax-advantaged parental leave savings accounts (e.g., the Working Parents Flexibility Act of 2019, H.R. 1859) and tax-advantaged distributions from health savings accounts for family and medical leave purposes (e.g., the Freedom for Families Act, H.R. 2163).48 The Support Working Families Act (S. 2437) would provide a parental leave tax credit to individuals taking parental leave.

In addition, the President's FY2021 budget proposed to provide six weeks of financial support to new parents through state unemployment compensation (UC) programs.49 A similar approach was taken in 2000 by the Clinton Administration, which—via Department of Labor regulations—allowed states to use their UC programs to provide UC benefits to parents who take unpaid leave under the FMLA, other approved unpaid leave, or otherwise take time off from employment after the birth or adoption of a child. The Birth and Adoption Unemployment Compensation rule took effect in August 2000, and it was later removed from federal regulations in November 2003.50