Introduction

Cigarette use remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, claiming an estimated 480,000 lives or more each year.1 Further, between 2009 and 2012, cigarette smoking-attributable economic costs totaled over $289 billion in the United States.2 Although cigarette use in the United States continues to decline,3 according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyses, 34.2 million American adults smoked cigarettes every day or some days in 2018,4 and nearly 1.2 million American middle and high school students smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days in 2019.5

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) have become popular in recent years, particularly among youth. ENDS is an umbrella term for various types of electronic tobacco products, including electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). An e-cigarette is a battery-operated device typically containing nicotine, flavorings, and other chemicals that, when heated, creates inhalable aerosol (i.e., vapor).6 According to CDC analyses, 8.1 million American adults used e-cigarettes every day or some days in 2018.7 About 5.4 million American middle and high school students used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days in 2019.8

There has been debate in the public health community regarding the public health impact of ENDS products. Some view them as a safer alternative for adults who smoke cigarettes because the aerosol produced from e-cigarettes is considered less harmful in the short-term than combusted smoke produced from cigarettes.9 However, others are alarmed by the marked increase in ENDS use among youth, and are concerned that these products may undo the years of tobacco control efforts that have successfully reduced cigarette smoking among both youth and adults. Further, the emergence of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) that has resulted in 60 deaths and 2,711 hospitalizations as of January 21, 202010 has raised concern among public health stakeholders, Congress, and the general public.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is responsible for regulating the manufacture, marketing, distribution, and sale of tobacco products. FDA's Center for Tobacco Products (CTP)—established in 2009 pursuant to the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (TCA; P.L. 111-31)—is primarily responsible for tobacco product regulation. The TCA established FFDCA chapter IX, under which FDA is authorized to regulate tobacco products. Within CTP, the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) provides recommendations on tobacco regulatory decisions or any other matter listed in chapter IX of the FFDCA. The TPSAC includes 12 members with diversified experience and expertise.11

Because tobacco products have no added health benefits, FDA's regulation of these products differs in certain respects from FDA's regulation of medical products under its jurisdiction (e.g., prescription drugs, biologics, and medical devices). Similar to medical product manufacturers, tobacco product manufacturers are subject to manufacturer requirements, including payment of user fees, registration establishment, and premarket review, among others. However, while medical product manufacturers are generally required to meet a standard of safety and effectiveness to receive premarket approval from FDA, tobacco product manufacturers are instead generally required to meet a standard of "appropriate for the protection of public health" to receive marketing authorization. In addition, tobacco product manufacturers, importers, distributors, and retailers are required to comply with certain tobacco-specific requirements that have been authorized under the TCA as a result of the unique harms that tobacco products pose to human health. Examples of such requirements include the development of tobacco product standards, testing and reporting of ingredients, submission of health information to the agency, and distribution and promotion restrictions, among others.

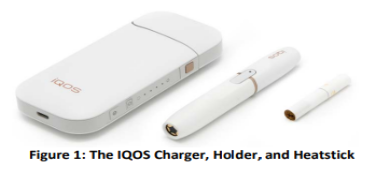

This report describes (1) FDA's authority to regulate tobacco products; (2) general requirements for manufacturers of tobacco products, many of which are modeled after medical product requirements; (3) requirements that are unique to tobacco product manufacturers, distributors, importers, and retailers; and (4) compliance and enforcement. The report concludes with a discussion of policy issues and considerations for Congress. Appendix A describes the IQOS Tobacco Heating System, Appendix B briefly summarizes the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement of 1998, Appendix C provides definitions of terms used in this report, and Appendix D provides acronyms used in this report.

FDA's Authority to Regulate Tobacco Products

As amended by the TCA, Section 901 of the FFDCA gives FDA the authority to regulate the manufacture, marketing, sale, and distribution of tobacco products. A tobacco product is defined as "any product made or derived from tobacco that is intended for human consumption, including any component, part, or accessory of a tobacco product (except for raw materials other than tobacco used in manufacturing a component, part, or accessory of a tobacco product)."12 Any article that is a drug, device, or combination product (a combination of a drug, device, or biological product) is excluded from the definition of tobacco product. Drugs, devices, and combination products are subject to chapter V authorities under the FFDCA.13 However, it is not always clear whether a product that is derived from tobacco should be regulated as a drug, device, combination product, or a tobacco product (e.g., an ENDS product that makes certain health claims). As such, FDA has promulgated regulations to provide assistance to manufacturers intending to market products that are made or derived from tobacco based on the products' "intended uses."14

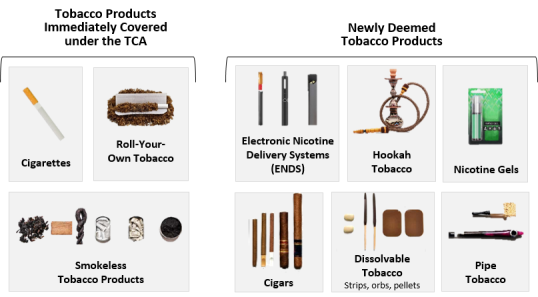

Upon enactment, the TCA explicitly covered the following tobacco products: cigarettes and cigarette tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, and smokeless tobacco.15 However, the TCA gave FDA the broad authority to regulate any other tobacco products deemed by the agency to meet the definition of a tobacco product and thus subject to chapter IX of the FFDCA.16 In 2016, FDA promulgated regulations (known as "the deeming rule") that extended the agency's authority over all tobacco products that were not already subject to the FFDCA, including ENDS, cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah tobacco, nicotine gels, dissolvable tobacco, and other tobacco products that may be developed in the future.17 Figure 1 shows each of the tobacco products currently under FDA's authority.

Tobacco Product Regulation: Manufacturer Requirements

Tobacco product manufacturers are subject to certain requirements, including payment of user fees, registration establishment, premarket review, and postmarket surveillance, among others. In the sections below, manufacturer requirements are discussed for tobacco products overall, with exceptions for issues unique to certain classes of tobacco products.

User Fees

Pursuant to its authorities in the FFDCA, FDA is required to assess and collect user fees from domestic manufacturers and importers of tobacco products and use the funds to support CTP's activities.18 Similar to FDA's other user fee programs, the agency assesses and collects fees from industry sponsors of certain FDA-regulated products—in this case, tobacco manufacturers and importers—and uses those funds to support statutorily defined activities.19 However, in contrast to other FDA centers that are generally funded by a combination of discretionary appropriations from the General Fund and user fees, CTP is funded solely by user fees. The tobacco product fee authorities are also indefinite. Thus, unlike medical product fees that are authorized in legislation on a five-year cycle, tobacco product fees do not require reauthorization. As with other FDA user fees, the tobacco fees are only available pursuant to an annual appropriation from Congress, which provides FDA the authority to collect and spend fees.20

Tobacco user fees are assessed and collected quarterly, and the total user fee amount that can be authorized and collected each year is specified in statute.21 For fiscal year (FY) 2019 and subsequent fiscal years, this amount is $712 million. The total user fee amount is assessed among six tobacco product classes specified in statute: (1) cigarettes, (2) cigars (including small cigars and cigars other than small cigars), (3) snuff, (4) chewing tobacco, (5) pipe tobacco, and (6) roll-your-own tobacco (see Table 1 for FY2020 data).22

The FFDCA requires that FDA use the Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act of 2004 (FETRA)—enacted as Title VI of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-357)—framework to assess user fees on six classes of tobacco products,23 and these are the same six classes that are specified in the FETRA provisions.24 The FETRA provisions specify a two-step formula.25 The first step determines the allocations for each of the six tobacco product classes, and the second step determines the individual domestic manufacturer and importer allocations within each respective tobacco product class. Because FETRA did not account for the differential taxing of cigars compared to the other tobacco product classes, the FFDCA specifies how user fees will be assessed for cigars.26

FDA has determined that it currently does not have the authority to assess user fees on ENDS manufacturers and importers, or manufacturers or importers of certain other newly deemed tobacco products (e.g., hookah tobacco).27 This determination was made by FDA because Congress did not specify enumerated classes for these products and did not provide a framework by which FDA could potentially assess user fees for such products.28

|

Tobacco Product Class |

Percentage Share by Class (%)a |

Amount |

|

Quarterly FY2020 User Fee Assessment |

||

|

Cigarettes |

86.0996% |

$153,257,288 |

|

Cigars |

11.6945% |

$20,816,210 |

|

Snuff |

1.2746% |

$2,268,788 |

|

Pipe Tobacco |

0.8218% |

$1,462,804 |

|

Chewing Tobacco |

0.0661% |

$117,658 |

|

Roll-Your-Own Tobacco |

0.0431% |

$76,718 |

|

Total |

99.9997% |

$177,999,466 |

|

Total FY2020 User Fee Assessment |

||

|

$711,997,864 |

||

Source: Prepared by CRS using FDA, "FY2020 Tobacco User Fee Assessment Formulation by Product Class," https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/manufacturing/tobacco-user-fee-assessment-formulation-product-class.

Notes: Percentages and user fees collected may not add evenly due to rounding. Data were not available for all four quarters of user fees collected, and thus only anticipated fourth-quarter data are presented.

a. Percentages are based on volume of domestic sales by tobacco product class. These data are provided by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, National Revenue Center, Report Symbol TTB S 5210-12-2018 (March 12, 2019), www.ttb.gov/tobacco/tobacco-stats.shtml.

Establishment Registration and Product Listing

Owners and operators of domestic tobacco product manufacturers are required to immediately register with FDA upon beginning operations and to subsequently register their establishments by the end of each year.29 FDA is required to make this registration information public.30 As part of the registration requirements, domestic tobacco product manufacturers must also submit product listing information, which includes a list of all tobacco products manufactured for commercial distribution.31 The listing for each tobacco product must be clearly identified by the product category (e.g., smokeless tobacco) and unique name (i.e., brand/sub-brand). If the listed tobacco products differ in any way, such as a difference in a component or part, manufacturers are encouraged to list each tobacco product separately.32 In addition, the listing must include a reference for the authority to market the tobacco product, and it must provide all consumer information for each tobacco product, such as labeling and a "representative sampling of advertisements."33 However, given the potential administrative burden on the registrant, FDA specifies in a guidance document that labeling for each individually listed tobacco product is not necessary if information that represents the labeling for a selected set of related products is provided.34 Registrants are encouraged to submit their materials online using FDA's Unified Registration and Listing System (FURLS) Tobacco Registration and Product Listing Module (TRLM).35

Tobacco Product Manufacturer Inspections

Every tobacco product manufacturer that registers with FDA is subject to biennial inspections. This inspection requirement starts on the date the establishment registers, and FDA must conduct an inspection at least once in every successive two-year period thereafter.36

The goal of such inspections is to review processes and procedures, observe and evaluate operations, document and collect information, identify any violations, communicate those violations to the manufacturer, and document any proposed corrective action plans.37 FDA personnel—upon presenting appropriate credentials and a written notice to the owner, operator, or agent in charge—are authorized to enter the tobacco product manufacturer to inspect the factory and all pertinent equipment and materials "at reasonable times and within reasonable limits and in a reasonable manner."38 Upon completing the inspection and prior to leaving the premises, FDA is required to produce a written report describing any observed conditions or practices indicating that any tobacco product has been prepared in a way that is injurious to health.39

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs)

FDA is required to promulgate regulations that outline good manufacturing practices (GMPs) to ensure that "the public health is protected and that the tobacco product is in compliance" with chapter IX of the FFDCA.40 Specifically, statute specifies that the regulations should include the methods, facilities, and controls involved in the manufacture, packing, and storage of a tobacco product.41 Prior to promulgating the regulations, TPSAC and the public (through an oral hearing) have an opportunity to recommend modifications to the proposed regulations. In addition, the regulations are required to take into account different types of tobacco products, the financial resources of different tobacco manufacturers, and reasonable time for manufacturers to comply with GMPs.42 A manufacturer may petition to be exempt from such requirements and receive approval from FDA if the agency determines that compliance with GMPs is not required to ensure that the tobacco product would be in compliance with chapter IX of the FFDCA.43

To date, FDA has not promulgated GMP regulations. In 2012, 13 tobacco companies submitted recommendations to be included in the GMP regulations and subsequently met with FDA to review their recommendations and approach to developing them.44 FDA then established a public docket for additional comments on the tobacco companies' recommendations in 2013.45 However, FDA did not take further action specific to promulgating GMP regulations after these actions. FDA's 2016 deeming rule stated that "FDA will have the authority to issue tobacco product manufacturing practice regulations under section 906(e)" of the FFDCA for ENDS and other newly deemed products.46 Following the issuance of this rule, numerous ENDS industry stakeholders submitted recommendations to FDA highlighting differences between GMP regulations for ENDS products and other tobacco products (cigarettes, cigarette tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, and smokeless tobacco).47 FDA then opened a public docket in November 2017 to allow for comment on these proposed ENDS GMPs,48 but the agency has not taken further action since then.

Premarket Review Pathways

There are four different premarket review pathways for tobacco products: (1) premarket tobacco application (PMTA), (2) substantial equivalence (SE), (3) substantial equivalence (SE) exemption, and (4) modified risk tobacco product (MRTP). To legally market a new tobacco product,49 a manufacturer must receive a PMTA marketing authorization order, unless FDA determines that the new tobacco product is substantially equivalent to a predicate tobacco product or is exempt from substantial equivalence.50 To legally market a new tobacco product with reduced risk claims or modify a legally marked tobacco product to make reduced risk claims, a manufacturer must receive an MRTP order.

All tobacco products originally covered by the TCA are required to undergo premarket review, unless they are "grandfathered products."51 Following the 2016 deeming rule, all newly deemed tobacco products became subject to premarket review requirements as well. In July 2017, FDA announced its Comprehensive Plan for Tobacco and Nicotine Regulation (Comprehensive Plan). As part of its Comprehensive Plan, FDA issued guidance that pushed back premarket review application deadlines to August 2021 for newly deemed combustible tobacco products (e.g., cigars) and August 2022 for newly deemed noncombustible tobacco products (e.g., ENDS) on the market as of August 8, 2016.52 This administrative action was subject to legal challenge, after several public health groups (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids) filed a lawsuit against FDA.53 In May 2019, the U.S. District Court for Maryland ruled in favor of the public health organizations,54 and in July 2019, imposed a 10-month deadline for application submissions for all newly deemed tobacco products (i.e., May 2020) and a one-year deadline for reviewing the applications (i.e., May 2021).55

|

CY2015 |

CY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 as of 12/17/19 |

|

|

PMTA Marketing Orders |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

|

SE Orders |

460 |

6a |

79a |

255 |

296 |

30 |

|

Exemption from SE Orders |

1 |

0 |

26 |

58 |

244 |

41 |

|

MRTP Orders |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

Total |

469 |

6 |

105 |

313 |

544 |

81 |

Source: Prepared by CRS using data from the FDA, https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/TobaccoProductReviewEvaluation/ucm339928.htm and https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/premarket-tobacco-product-applications/premarket-tobacco-product-marketing-orders, as of December 17, 2019.

Notes: CY=Calendar Year; FY=Fiscal Year; PMTA=Premarket Tobacco Application; SE=Substantial Equivalence; MRTP=Modified Risk Tobacco Product. Applications were evaluated by year from 2014 to 2016, and by fiscal year starting in FY2017. Data are presented starting in 2014, when PMTA Marketing Order data first became available.

a. There were 3 SE marketing orders issued in December 2016, and those 3 SE orders are counted in both CY2016 and FY2017.

As shown in Table 2, since 2014, most new tobacco products have been legally marketed through the SE pathway. However, only requirements for the SE exemption pathway have been promulgated in regulations.56 This has posed some challenges for manufacturers when preparing application submissions for the PMTA, SE, and MRTP pathways. In April 2019, FDA issued a proposed rule on the content and format of SE reports,57 with public comment open until June 2019. Also in June 2019, FDA finalized its guidance on PMTA submissions specific to ENDS.58 In September 2019, FDA issued a proposed rule on the content and format of PMTA applications, with public comment open until November 2019.59 As of February 2020, FDA has not publicly indicated a timeline for issuance of a final rule.

Premarket Tobacco Product Applications (PMTA) Pathway

A manufacturer must submit a PMTA and receive a PMTA marketing authorization order to legally market a new tobacco product that is not substantially equivalent to a predicate tobacco product or exempt from substantial equivalence. To receive a PMTA order, the application must demonstrate that the product is "appropriate for the protection of public health."60 This determination is made based on the risks and benefits to the whole population of users and nonusers of the product, while taking into account

the increased or decreased likelihood that existing users of tobacco products will stop using such products; and

the increased or decreased likelihood that those who do not use tobacco products will start using such products.61

PMTA applications must include, among other things, full reports of health risk investigations; a full statement of what is in the product (e.g., components, additives); a full description of manufacturing and processing methods; compliance with tobacco product standards; samples and components of the product; and proposed labeling of the product.62 FDA has 180 days after receipt of the complete application to determine whether the product will receive a PMTA order.63 If marketing is authorized, FDA can require that the sale and distribution of the tobacco product is restricted.64

FDA can deny a PMTA application for various reasons. These include if the agency determines that marketing the new tobacco product would not be appropriate for the protection of public health; the methods used for manufacturing, processing, or packing the tobacco product do not align with good manufacturing practices; the proposed labeling of the tobacco product is false or misleading; or the tobacco product does not conform with regulations specifying tobacco product standards.65 FDA can withdraw or temporarily suspend a PMTA order if the agency finds that the continued marketing of the tobacco product is no longer appropriate for the protection of public health; the PMTA application contained false material; the applicant does not maintain records or create reports about its tobacco product; the labeling of the tobacco product becomes false or misleading; or the tobacco product does not conform to a tobacco product standard without appropriate justification.66 To determine if there are grounds to withdraw or temporarily suspend a PMTA order, FDA can require by regulation, or on an application-by-application basis, that applicants establish and maintain records, and provide postmarket surveillance reports to FDA following PMTA marketing authorization.67

Substantial Equivalence (SE) Pathway

A new tobacco product is considered to be substantially equivalent to a predicate tobacco product if it has the same characteristics as the predicate tobacco product or if it has different characteristics that do not raise different questions of public health.68 A product may serve as a predicate tobacco product if it was commercially marketed as of February 15, 2007, or if it has previously been determined as substantially equivalent to another predicate tobacco product. A tobacco product may not serve as a predicate product if it has been removed from the market or has been determined to be adulterated or misbranded.

If a new tobacco product is considered substantially equivalent to the predicate tobacco product, the manufacturer is required to submit an SE report to FDA justifying a substantial equivalence claim at least 90 days prior to the introduction of the new tobacco product into the market.69 To accommodate manufacturers following enactment of the TCA, a new tobacco product that was introduced after February 15, 2007, but before March 22, 2011, could stay on the market while FDA reviewed the manufacturer's SE report, provided the report was submitted before March 23, 2011. However, if a manufacturer did not submit the SE report before March 23, 2011, or if the new tobacco product has been on the market since March 22, 2011, the product is not permitted to be marketed without an SE order from FDA, even if FDA takes longer than 90 days to approve and issue the order.70

The contents of SE reports are not specified in statute or regulation,71 but FDA has provided content recommendations for SE reports in guidance.72 Among other things, SE reports should include a summary, listing of design features, ingredients and materials, a description of the heating source and composition, and health information. Upon acceptance of the SE report application and FDA's evaluation that the predicate tobacco product selected is eligible, FDA evaluates the scientific data and information in the SE report. FDA will then issue a SE order letter or not substantially equivalent order (NSE order) letter.73

Substantial Equivalence (SE) Exemption Pathway

A new tobacco product that has been modified from a legally marketed tobacco product by either adding or removing a tobacco additive, or by increasing or decreasing the quantity of an existing tobacco additive, may be exempt from demonstrating substantial equivalence.74 For such a product to be exempt, FDA must determine that (1) the modification would be considered minor, (2) an SE report that demonstrates substantial equivalence would not be necessary to ensure that marketing the tobacco product would be appropriate for protection of public health, and (3) an "exemption is otherwise appropriate."75 Before the product can be legally marketed, FDA must first grant the product an exemption from demonstrating substantial equivalence.76 Following this, a manufacturer must submit a SE exemption report detailing the minor modification and establishing that FDA has determined that the product is exempt from demonstrating substantial equivalence to a predicate product.77

The content requirements for SE exemption reports are specified in regulation.78 Among other things, SE exemption reports must contain a detailed explanation of the purpose of the modification; a detailed description of the modification; a detailed explanation of why the modification is minor; a detailed explanation of why a SE report is not necessary; and a certification (i.e., signed statement by a responsible official of manufacturer) summarizing why the modification does not increase the tobacco product's appeal to or use by minors, toxicity, addictiveness, or abuse liability.

Modified Risk Tobacco Products (MRTP) Pathway

A modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) is defined as "any tobacco product that is sold or distributed for use to reduce harm or the risk of tobacco-related disease associated with commercially marketed tobacco products."79 For example, some ENDS manufacturers may decide to submit an ENDS product through the MRTP pathway if the application can justify that the product reduces the risk of tobacco-related disease compared with other tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes). However, an MRTP may not be introduced or delivered into interstate commerce until FDA has issued an MRTP order, regardless if it was already legally on the market through another pathway (e.g., SE or SE exemption).80 Further, any manufacturer that has not received an MRTP order for its tobacco product may not market the product with a label, labeling, or advertising that implies the product has a reduced risk of harm or that uses the words "light," "mild," "low," or similar descriptions.81 Smokeless tobacco products that use certain descriptors, such as "does not produce smoke" or "smoke-free," are not automatically considered MRTPs unless a manufacturer receives MRTP orders for those products.82 In addition, products that are intended to treat tobacco dependence are not considered MRTPs if they have been approved as a drug or device.83

Manufacturers must include certain information in a MRTP application, including

a description of the proposed product and any proposed advertising and labeling;

the conditions for using the product;

the formulation of the product;

sample product labels and labeling;

all documents (including underlying scientific information) relating to research findings conducted, supported, or possessed by the tobacco product manufacturer relating to the effect of the product on tobacco-related diseases and health-related conditions, including information both favorable and unfavorable to the ability of the product to reduce risk or exposure and relating to human health;

data and information on how consumers actually use the tobacco product; and

such other information as the Secretary [FDA] may require.84

FDA must refer all complete MRTP applications to TPSAC given the health claims that need to be evaluated and verified in applications for these products. TPSAC then has 60 days to provide recommendations on the application to FDA. FDA can issue an MRTP order for a specified period of time (but not more than five years at one time85) if, among other things, it determines that the tobacco product will significantly reduce harm and the risk of tobacco-related disease to individual tobacco users and benefit the health of the population as a whole by taking into account users and nonusers of tobacco products.86 To continue to market a MRTP after the order's set term, a manufacturer would need to seek renewal of the MRTP order.

However, FDA may issue an order for certain tobacco products that may not meet the standard of significantly reducing harm to individual users and benefiting population health as a whole. This is possible if, among things, the manufacturer can demonstrate that the MRTP order for the tobacco product would be appropriate to promote public health; the label, labeling, and advertising for the tobacco product are limited to claims that the product presents less exposure to a substance; scientific evidence is not available and cannot be made available without conducting the long-term epidemiologic studies required to meet the MRTP standard; and the scientific evidence that is available demonstrates if future studies are conducted, they would likely demonstrate a measurable and substantial reduction in morbidity or mortality among users of the tobacco product.87

MRTP Postmarket Requirements

To market a tobacco product that has received an MRTP order, the manufacturer must agree to certain postmarket surveillance and studies that examine consumer perception, behavior, and health pertaining to the product. Manufacturers required to conduct surveillance must submit the surveillance protocol to FDA within 30 days of receiving notice from FDA that such studies are required. Upon receipt of the protocol, FDA has 60 days to determine whether the protocol is sufficient to collect data that will allow FDA to determine if the MRTP order is necessary to protect public health.

FDA can also require that labeling and advertising of the product enable the public to understand the significance of the presented information to the consumer's health. Further, FDA can impose conditions on the use of comparing claims between the tobacco product with an MRTP order and other tobacco products on the market, and require that the label of the product disclose substances in the tobacco product that could affect health.88

FDA must withdraw the MRTP order, after the opportunity for an informal hearing, under specified circumstances. Examples of such circumstances include if new information becomes available that no longer make an MRTP order permissible, if the product no longer reduces risk or exposure based on data from postmarket surveillance or studies, or if the applicant failed to conduct or submit postmarket surveillance or studies.89

|

Investigational Tobacco Products FFDCA Section 910(g) allows FDA to issue regulations exempting tobacco products from certain chapter IX requirements. For example, manufacturers may need to use investigational tobacco products in studies to generate evidence for submission as part of a premarket application. While FDA has not yet promulgated such regulations, the agency issued draft guidance in February 2019 clarifying its enforcement policy regarding the use of investigational tobacco products until regulations are issued and become effective.90 The guidance defines an investigational tobacco product as "a tobacco product that is intended for investigational use and is: (1) a new tobacco product; or (2) a tobacco product that is required to comply with a tobacco product standard and that does not conform in all respects to the applicable tobacco product standard."91 |

Cessation Products

FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) is generally responsible for regulating tobacco-derived products that make health or cessation (i.e., quitting) claims, such as nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs).92 NRTs contain nicotine as an active ingredient. Two types of prescription NRT products (nasal spray and nicotine inhaler) and three types of over-the-counter (OTC) NRT products have been approved by FDA through CDER, and most of these products have been approved for over 20 years.93 The three types of OTC products include a nicotine gum, a transdermal nicotine patch, and a nicotine lozenge. Prescription medications that do not have nicotine as an active ingredient have also been approved by CDER for smoking cessation. These medications include Chantix (varenicline tartrate) and Zyban (buproprion hydrochloride).94

In the future, ENDS manufacturers who make health or cessation claims for their products would likely need to receive approval for marketing from CDER (rather than marketing authorization from CTP).

Tobacco Product Regulation: Tobacco-Specific Requirements

Tobacco product manufacturers, importers, distributors, and retailers are required to comply with certain tobacco-specific requirements as a result of the unique harms that tobacco products pose to human health. Each of these requirements is described below, and most requirements apply to all tobacco products, with some specified exceptions.

Tobacco Product Standards

Prior to enactment of the TCA, Congress was concerned that the tobacco industry had the ability to design new tobacco products or modify existing ones that might appeal to children or increase exposure to harmful tobacco product constituents.95 The TCA gave FDA the authority to adopt tobacco product standards that it deems necessary to protect the public's health,96 but it explicitly prohibited FDA from creating a standard that bans cigarettes, smokeless tobacco products, cigars, pipe tobacco, or roll-your-own tobacco products.97 Congress could choose to amend this language at any time.

A new tobacco product standard can set certain manufacturing, packaging, and distribution and sale requirements for tobacco products. For example, FDA can set requirements for ingredients, additives, components, or parts allowed in a tobacco product; testing of the tobacco product and test results demonstrating compliance with the standard; measurement of characteristics of the tobacco product; appropriate labeling of the tobacco product; and limited sale and distribution of the tobacco product.98 To adopt a tobacco product standard, FDA is required to consider scientific evidence on

the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and nonusers of tobacco products, of the proposed standard; the increased or decreased likelihood that existing users of tobacco products will stop using such products; and the increased or decreased likelihood that those who do not use tobacco products will start using such products.99

To propose a new tobacco product standard, FDA is required to publish a proposed rule in the Federal Register and allow for a public comment period of no less than 60 days. If FDA determines that the tobacco product standard is appropriate for the protection of public health based on an evaluation of public comments, a report from TPSAC (if the standard was referred to them), and other evidence, the agency must promulgate a final regulation to establish the standard. This regulation cannot take effect until at least one year after its publication, unless FDA determines that "an earlier effective date is necessary for the protection of public health."100

FDA is required to periodically reevaluate tobacco product standards to determine if new data need to be reflected. In addition, a tobacco product standard may be amended or revoked either on the initiative of FDA or an interested party via petition (i.e., citizen petition). If FDA or a citizen petition calls for an amendment to or revocation of an existing tobacco product standard, a proposed rule would be issued in the Federal Register for public comment. As with a new tobacco product standard, FDA would make a determination regarding the existing standard based on review of the public comments, a TPSAC report (if relevant), and other evidence. For FDA to revoke a standard, the agency must find that the standard is "no longer appropriate for the protection of public health."101

Flavors

When enacting the TCA, Congress recognized that flavors, specifically, can make tobacco products more appealing to youth and expose tobacco users to additional carcinogens or other toxic constituents.102 Although FDA has the authority to establish new tobacco product standards (as previously described), Section 907 of the FFDCA establishes a tobacco product standard explicitly banning characterizing artificial or natural flavors (other than tobacco or menthol), herbs, or spices in any constituent, additive, and component or part of a cigarette.103 While tobacco and menthol flavors are not included in the prohibition on characterizing flavors in cigarettes, FDA may be able to establish a tobacco product standard addressing menthol in cigarettes.104

Within one year of its establishment, TPSAC was required to submit a report and recommendations to the Secretary of HHS regarding the impact of menthol cigarette use on public health, specifically addressing use among youth and racial and ethnic minorities.105 In its final report released in July 2011, TPSAC concluded that "removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit public health in the United States."106 In July 2013, FDA released an advance notice of public rulemaking (ANPRM) on a tobacco product standard for menthol in cigarettes, seeking comments, data, research, and any other relevant information.107 A final regulation has not yet been promulgated; however, Former Commissioner Gottlieb expressed interest in accelerating the promulgation of this tobacco product standard.108

FDA released an ANPRM in March 2018, "Regulation of Flavors in Tobacco Products," that requested public comments, data, research results, and other information related to the role of flavors generally in tobacco products, among other things.109 After one extension, the comment period closed in July 2018 and the agency had received over 500,000 comments. In January 2020, FDA stated its intention to issue a proposed rule that would "ban the use of characterizing flavors in cigars," but did not speak to characterizing flavors in other tobacco products.110

Nicotine

Nicotine is the naturally occurring drug in tobacco that can cause addiction to the product.111 The FFDCA allows FDA to address nicotine yields of a tobacco product through development of a tobacco product standard,112 but it prohibits the agency from establishing a tobacco product standard that would require the reduction of nicotine yields to zero.113

A key feature of FDA's Comprehensive Plan is to implement regulatory policies on addiction, appeal, and cessation based on scientific evidence and public input. One stated goal was to lower nicotine in cigarettes to a minimally or non-addictive level to benefit the public's health. In March 2018, FDA released an ANPRM for development of a tobacco product standard that would set a maximum nicotine level for cigarettes.114 The ANPRM seeks public comment on whether a tobacco product standard should apply to other combusted tobacco products (e.g., cigars, pipe tobacco); what a non-addictive level of nicotine would be; and other feasibility issues if such a tobacco product standard is implemented. The comment period closed in July 2018, after an extension, with nearly 8,000 comments received. As of February 2020, FDA has not taken further regulatory action.

Testing and Reporting of Ingredients

FDA has the authority to conduct or to require testing, reporting, or disclosure of tobacco product constituents, including smoke constituents.115 Pursuant to FFDCA Section 915, FDA is required to promulgate regulations that require the testing and reporting of components or parts of a tobacco product to protect the public health. Because FDA has not yet promulgated these testing and reporting regulations, tobacco product manufacturers are not currently subject to these requirements.116

As part of these regulations, once they are promulgated, FDA may require tobacco product manufacturers to disclose the results of the testing of tar and nicotine through labels, advertising, or other means to protect public health and not mislead consumers about harms associated with use of the tobacco product. Small tobacco product manufacturers would be given additional time to comply, and FDA could additionally delay compliance on a case-by-case basis for small tobacco product manufacturers.117

Health Information

Tobacco product manufacturers are required to submit specified health information to FDA. This health information includes a list of all ingredients, such as substances, compounds, and additives that are added to the tobacco product by the manufacturer. Health information also includes "a listing of all constituents, including smoke constituents as applicable, identified by the Secretary as harmful or potentially harmful to health in each tobacco product."118 Manufacturers must provide this information within each brand of the tobacco product, and the quantity included in each brand (e.g., Marlboro) and sub-brand (e.g., Marlboro Gold).119 FDA's compliance policy for ingredient listings, as specified in guidance, focuses on finished tobacco products (i.e., tobacco products packaged and ready for consumption), including cigarettes, cigarette tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, smokeless tobacco, and newly deemed tobacco products (e.g., ENDS).120 Further, FDA is focusing on components or parts of finished tobacco products that are made or derived from tobacco or contain ingredients that are burned, aerosolized, or ingested while the tobacco product is being used. As an example, e-liquids of ENDS are currently subject to this ingredient listing requirement, while batteries of ENDS are not.

Harmful and Potentially Harmful Constituents

As interpreted by FDA in guidance, the phrase harmful and potentially harmful constituents (HPHCs) refers to any chemical or chemical compound in a tobacco product or in tobacco smoke that

is, or potentially is, inhaled, ingested, or absorbed into the body, including as an aerosol (vapor) or any other emission; and

causes or has the potential to cause direct or indirect harm to users or non-users of tobacco products.121

Examples of HPHCs include toxicants, carcinogens, and addictive chemicals and compounds. By 2012 (three years after enactment of the TCA), FDA was required to establish a list of HPHCs in each tobacco product and, as applicable, to identify HPHCs by brand and sub-brand of tobacco products.122 Based on TPSAC's recommendations and after receiving multiple rounds of public comment on these recommendations, FDA established a list of 93 HPHCs in tobacco products. This list specifies whether the HPHC is a carcinogen, respiratory toxicant, cardiovascular toxicant, reproductive or developmental toxicant, and/or addictive.123

Using FDA's list, manufacturers are required to report HPHCs by brand and quantity of HPHCs in each brand and sub-brand.124 Given potential monetary and feasibility challenges that were associated with reporting all 93 HPHCs on FDA's list, FDA released an accompanying 2012 draft guidance that provided an abbreviated list of HPHCs that manufacturers of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and roll-your-own tobacco would be required to report to FDA.125 FDA has not issued an update to the 2012 draft guidance. As a result, FDA does not intend to enforce this requirement for newly deemed tobacco products (e.g., ENDS) until after the publication date of the final guidance.126 However, in August 2019, FDA announced that, for the first time, it is seeking public comment on 19 additional HPHCs that can be found in ENDS products.127 The public comment period closed in October 2019.128

Health Documents

Tobacco product manufacturers are required to submit to FDA all documents developed by the manufacturer or any other party on health, toxicological, behavioral, or physiologic effects of current or future tobacco products, including constituents, ingredients, components, and additives.129 FDA interprets these documents to include "cell-based, tissue-based, animal, or human studies, computational toxicology models, information on addiction, intentions to use, cognition, emotion, motivation, and other behavioral effects at both the population-level (epidemiology) as well as the individual level (such as abuse liability)."130

Records and Reports on Tobacco Products

FDA has the authority to require, by regulation, tobacco product manufacturers and importers to establish and maintain records to ensure that tobacco products are not adulterated or misbranded and to otherwise protect public health.131 Through such regulations, FDA can also require manufacturers and importers to report if a tobacco product may have caused or contributed to a "serious unexpected adverse experience or any significant increase in the frequency of a serious, expected adverse product experience."132 Required reports cannot be overly burdensome and cannot disclose the identity of a patient, except under certain circumstances.133

FDA has not yet promulgated regulations specifying these requirements. However, FDA issued a proposed rule in April 2019 on the content of a SE report. The proposed rule would require applicants submitting an SE report and receiving an SE order to maintain all records supporting the SE report for at least 4 years.134 FDA also issued a proposed rule in September 2019 for PMTAs that, among other things, would require manufacturers to "keep records regarding the legal marketing of certain tobacco products without a PMTA."135

Distribution and Promotion Requirements

Prior to 2009, restrictions on the distribution of tobacco products were largely enforced at the state level, and promotion of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco was largely overseen by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).136 However, in 2009, the TCA explicitly gave FDA the authority to require, by regulation, restrictions on the sale and distribution of a tobacco product if such a regulation would be appropriate for the protection of public health.137 In addition, the FFDCA specifies that FDA can impose restrictions, by regulation, on the advertising and promotion of a tobacco product consistent with the First Amendment.138

In addition to authorizing FDA to regulate the sale and distribution of tobacco products, the TCA also directed FDA to reissue its 1996 Tobacco Rule.139 Among other things, the 1996 Tobacco Rule imposed requirements on the sale, labeling, and advertising of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco.140 The TCA provided that the final rule must be identical to the 1996 rule, with specified exceptions. FDA reissued the 1996 rule in March 2010,141 and the 2016 deeming rule extended the applicability of sale and distribution restrictions, as well as certain labeling and advertising requirements to newly deemed tobacco products (e.g., ENDS). In FY2020 appropriations, Congress amended the federal minimum age of tobacco product purchasing from 18 to 21.142

Current law and regulations restricting the sale and distribution of tobacco products will be discussed first, followed by current law and regulations on the labeling and advertising of tobacco products.

Restrictions on Sales and Distribution of Tobacco Products

The FFDCA—pursuant to changes made by the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-94)—prohibits retailers from selling tobacco products to any person younger than 21 years of age143 and limits FDA's ability to promulgate regulations that restrict the sale of tobacco products to those over 21 years of age.144 FDA has stated that this new age sales restriction is currently in effect.145

Prior to this statutory change, the minimum age of sale of tobacco products under federal regulations was 18 years of age, and the FFDCA precluded FDA from promulgating regulations restricting the sale of tobacco products to those over 18. As such, current federal regulations, which were promulgated in 2016 prior to the enactment of P.L. 116-94, prohibit retailers from selling cigarettes, smokeless tobacco products, and newly deemed tobacco products to anyone younger than 18, and require retailers to verify the age of persons purchasing these products who are younger than 27.146 To conform these regulations to changes made by P.L. 116-94, FDA is required to update the regulations by June 20, 2020 to specify that retailers may not sell tobacco products to those under 21 years of age and that retailers are required to verify the age of individuals attempting to purchase tobacco products who are younger than 30. The final rule is to take effect not later than September 20, 2020.147

Regulations also specify that manufacturers, distributors, or retailers may not distribute free samples of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco products, and newly deemed tobacco products, with the exception of smokeless tobacco in qualified adult-only facilities.148 Vending machine sales of cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and newly deemed tobacco products are prohibited, unless the vending machine is located in a qualified adult-only facility.149 Consistent with the limitations specified in statute, these regulations do not prohibit the sale of tobacco products in specific categories of retail outlets (e.g., pharmacies, specialty stores).150

Synar Regulations

As mentioned, prior to the enactment of the TCA, restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products were primarily enforced at the state level, and compliance with state laws prohibiting tobacco sales to minors varied.151 Evidence emerged about health problems associated with tobacco use by youth and about the ease with which youth could purchase tobacco products through retail sources.152 In 1992, the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAHMA) Reorganization Act (P.L. 102-321) was signed into law, and it included an amendment aimed at decreasing youth access to tobacco. More specifically, Section 1926 (known as the Synar amendment) of the ADAHMA Reorganization Act required that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) make available the full Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant (SABG) award funding to states and U.S. territories only if they had laws in effect that prohibit the sale or distribution of tobacco products to individuals younger than 18 years old.153 The SABG is a block grant program that distributes funds to 60 eligible states, U.S. territories, and freely associated states to plan, execute, and evaluate substance use prevention, treatment, and recovery support services for affected individuals, families, and communities.154 The SABG provides a consistent federal funding stream to states through formula grants, and it is one of SAMHSA's largest programs.155

The Synar regulations were promulgated by SAMHSA in 1996 to provide further guidance to states on implementation of the Synar amendment. The regulation requires, among other things, that states enact and enforce laws that prohibit the sale or distribution of tobacco products to individuals younger than 18; conduct annual inspections of retailers that are representative of retail outlets accessible to minors; and submit an annual report to SAMHSA on enforcement and compliance actions in order to receive their full SABG funding.156 As the term tobacco product, is not defined in the regulation, SAMHSA has indicated that each state may decide which tobacco products should be included in tobacco retailer inspections, but encourages states to include tobacco products being used most often by youth.157 In FY2020 appropriations, Congress further amended the Synar amendment to require states, as a condition of receiving SABG funding, to conduct annual, random inspections of retail outlets to ensure that such outlets are not selling tobacco products to those under age 21 and comply with annual reporting requirements to SAMHSA on enforcement and compliance actions. SAMSHA will be required to update the Synar regulations by June 20, 2020 to account for these changes.158

Tobacco Product Labeling and Advertisement Requirements

The Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965 (FCLAA)159 and the Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco Health Education Act of 1986 (CSTHEA) include certain labeling requirements and advertising restrictions on cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, respectively.160 FTC generally oversees these two acts.161 For example, one advertising restriction within these acts includes a ban on advertising cigarettes, little cigars, and smokeless tobacco products on radio, television, or other media subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).162

In addition, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers may not sell or distribute tobacco products with labels, labeling, or advertising that are not in compliance with the FFDCA and accompanying FDA regulations.163 Certain labeling and advertising requirements specific to cigarettes and smokeless tobacco include:

- Manufacturers, distributors, and retailers may not sponsor any athletic, musical, or other social or cultural event with the brand name of a cigarette or smokeless tobacco product.164

- Manufacturers and distributors of imported cigarettes and smokeless tobacco may not market, license, distribute, or sell any product that bears the brand name, logo, or any other identifying patterns associated with the brand name.165

- Labeling and advertising in audio and video formats are limited. For example, audio formats cannot include music or sound effects.166

Tobacco product package labeling and advertisements must also include warning statements. Table 3 lists the different health warning statements required to be displayed on tobacco product package labeling and in tobacco product advertisements, by product. For example, all ENDS package labeling and advertising is required to include "WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical."

Table 3. Required Warning Statements on Tobacco Product Packaging and Advertising, by Tobacco Product

|

Tobacco Products |

Required Warning Statements |

|

Cigarettesa |

SURGEON GENERAL'S WARNING: Smoking Causes Lung Cancer, Heart Disease, Emphysema, And May Complicate Pregnancy. SURGEON GENERAL'S WARNING: Quitting Smoking Now Greatly Reduces Serious Risks to Your Health. SURGEON GENERAL'S WARNING: Smoking By Pregnant Women May Result in Fetal Injury, Premature Birth, And Low Birth Weight. SURGEON GENERAL'S WARNING: Cigarette Smoke Contains Carbon Monoxide. |

|

Cigarette Tobacco |

WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical. |

|

Roll-Your-Own Tobacco (RYO) |

WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical. |

|

Smokeless Tobaccob |

WARNING: This product can cause mouth cancer. WARNING: This product can cause gum disease and tooth loss. WARNING: This product is not a safe alternative to cigarettes. WARNING: Smokeless tobacco is addictive. |

|

Newly Deemed Products (except cigars)c |

WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical. |

|

Cigars |

WARNING: Cigar smoking can cause cancers of the mouth and throat, even if you do not inhale. WARNING: Cigar smoking can cause lung cancer and heart disease. WARNING: Cigars are not a safe alternative to cigarettes. WARNING: Tobacco smoke increases the risk of lung cancer and heart disease, even in nonsmokers. WARNING: Cigar use while pregnant can harm you and your baby. Or SURGEON GENERAL WARNING: Tobacco Use Increases the Risk of Infertility, Stillbirth and Low Birth Weight. WARNING: This product contains nicotine. Nicotine is an addictive chemical. |

|

Tobacco products that do not contain or are not derived from tobacco or nicotine. |

These products are not subject to required warning statements. |

Source: Prepared by CRS, adapted from FDA, Retailers: Chart of Required Warning Statements on Tobacco Product Packaging and Advertising, https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/retail-sales-tobacco-products/retailers-chart-required-warning-statements-tobacco-product-packaging-and-advertising.

Notes: For all products, one of the warnings must be displayed on the two principal display panels. FDA is not enforcing health warning statement requirements for cigar and pipe tobacco products, given pending litigation.

a. These cigarette health warning labels are required by the FCLAA (15 U.S.C. §§1331-1340) and are overseen by FTC.

b. The first three listed warnings were originally authorized by the CSTHEA (15 U.S.C. §§4401-4408), The TCA amended the CSTHEA to include the fourth listed warning. FTC oversees these warning label requirements.

c. Newly deemed tobacco products include ENDS, cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah tobacco, nicotine gels, dissolvable tobacco, and other tobacco products that may be developed in the future.

Cigarette Graphic Warning Labels

The TCA required FDA to promulgate regulations requiring color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.167 In 2011, FDA published a final rule requiring graphic warning labels on cigarette packaging—in addition to nine new warning statements proposed in text—that would take effect 15 months after it was promulgated.168 The final rule was challenged in court, and in 2012, an appeals court vacated the rule on First Amendment grounds and remanded the issue to the agency. Ultimately, FDA did not seek further judicial review.169

FDA planned to develop and propose a new graphic warning rule and has continued to conduct research for this rule since 2013.170 In 2016, multiple health organizations filed a suit against FDA to compel the agency to promulgate a final rule more quickly.171 In March 2019, FDA was ordered to issue a proposed rule by mid-August 2019 and a final rule by mid-March 2020.172 The proposed rule, issued on August 16, 2019, specifies requirements for new cigarette health warnings.173 Among other things, the warnings would occupy the top 50% of the front and rear panels of cigarette packages, and at least 20% of the top area of cigarette advertisements. However, it is to be determined whether this proposed rule will be subject to further litigation.

Compliance and Enforcement

If FDA finds that a retailer, manufacturer, importer, or distributor is not complying with FFDCA chapter IX requirements or FDA regulations, the agency can take corrective action. Such corrective actions include warning letters, civil money penalty (CMP) complaints, and no-tobacco-sale order (NTSO) complaints, as well as seizures, injunctions, and criminal prosecution (with the Department of Justice).174

Adulterated and Misbranded Tobacco Products

The FFDCA prohibits the adulteration and misbranding of tobacco products, as well as the introduction, receipt, and delivery of adulterated or misbranded tobacco products into interstate commerce.175

Adulterated Tobacco Products

In general, a tobacco product is deemed adulterated if

- it is contaminated by any substance that may render the product injurious to health;

- it has been prepared in unsanitary conditions that may have contaminated the product;

- its packaging is composed of any substance that could be harmful to health; and/or

- if a manufacturer does not comply with user fee, tobacco product standard, premarket review, and/or GMP requirements (when promulgated).176

Misbranded Tobacco Products

A tobacco product is deemed misbranded if

- the labeling is false or misleading in any way;177

- its package labeling does not include specified manufacturing information, statements, or warnings required by regulation, or does not comply with an established tobacco product standard;178

- the labeling, packaging, and shipping containers of tobacco products do not contain the label "sale only allowed in the United States";179

- it was manufactured, prepared, propagated, compounded, or processed in a facility that was not registered with FDA;180

- its advertising is false or misleading in any way;181 and/or

- it is sold by a retailer to an individual under 21 years of age or is sold in violation of regulations promulgated on the sale and distribution of tobacco products.182

FDA may, by regulation, require prior approval of statements made on labels of tobacco products to ensure that the tobacco product is not misbranded. However, such a regulation cannot require prior approval of an advertisement, except for MRTPs.183 To date, FDA has not issued such regulations.

Tobacco Retailer Compliance Check Inspections

FDA is required to contract with states and territories to carry out compliance check inspections of tobacco retailers.184 In some instances, FDA has awarded contracts to third-party entities that hire commissionable inspectors to conduct compliance check inspections of tobacco retailers in states and territories where FDA has not been able to contract with a state or territory agency. FDA personnel may also conduct their own investigations.185

FDA ensures that tobacco retailers are in compliance with federal law and regulations through undercover buy inspections. During these inspections, the retailer is unaware an inspection is taking place. A trained minor, in consultation with a commissioned FDA inspector, attempts to purchase a tobacco product.186 If a first-time violation is reported (e.g., sale to a minor, illegal advertising), a warning letter is sent to the tobacco retailer, and the addressee has 15 working days to respond to the letter, with no associated fines involved. When subsequent violations of tobacco regulations or requirements are detected during these undercover buy inspections, FDA files a CMP complaint. The associated fines vary based on the number of regulation violations and the time period in which the violations occurred.187 If retailers have repeated violations of the restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products, FDA may seek a NTSO, which would prohibit sale of tobacco products at that retail outlet. A NTSO could be separate or combined with CMPs.188 According to FDA, as of June 2019, the agency has "conducted more than a million compliance check inspections and issued nearly 88,000 Warning Letters, 22,000 [CMPs], and 160 [NTSOs]."189

As mentioned, in FY2020 appropriations, Congress amended the federal minimum age of tobacco product purchasing from 18 to 21.190 FDA has stated that this new age sales restriction is currently in effect, but also recognizes that the agency and retailers will need to update current practices to account for these changes.191 As such, FDA has stated that "during this ramp-up period, FDA will continue to only use minors under the age of 18 in its compliance check program."192

Notification and Recall

FDA has the authority to issue notifications and recalls of tobacco products once they are on the market.193 FDA can issue a notification through a public service announcement if the tobacco product "presents an unreasonable risk of substantial harm to the public health,"194 provided that FDA determines there are no other practical means to eliminate such risk.

A tobacco product manufacturer can initiate or FDA can request a (voluntary) recall if the tobacco product is thought to be in violation of the FFDCA.195 In addition, FDA has the authority to mandate a tobacco product recall under specified circumstances. If FDA determines that a tobacco product contains a manufacturing or other defect that would "cause serious, adverse health consequences or death," the agency can issue an order requiring the appropriate person (e.g., the manufacturer, retailer, importer, or distributor) to immediately stop distribution of the tobacco product.196 FDA is required to provide the person subject to the order an opportunity for an informal hearing not later than 10 days after the order is issued. Following the hearing, FDA is required to vacate the order if the agency determines that there is insufficient evidence to maintain the order. If after the informal hearing FDA determines that the order should be amended to include a recall of the tobacco product, FDA must amend the order to require such recall, specifying a timetable for and requiring periodic progress reports on the recall.

Issues for Congress and Policy Considerations

Although the TCA expanded FDA's authority to regulate tobacco products in 2009, stakeholders have recently identified several issues related to the regulation of these products that may be of interest to Congress:

- FDA and public health stakeholders remain concerned about the marked increase in use of ENDS among youth over the past few years, and many in the public health community argue that this increase is largely driven by the availability of youth-friendly flavors in these products. While the public health community generally views ENDS as a safer alternative for adult cigarette smokers, there is concern that increased use of ENDS among youth may undo the years of tobacco control efforts that have successfully reduced cigarette smoking among both youth and adults. The emergence of EVALI has further heightened concern among public health stakeholders, Congress, and the general public.

- Public health stakeholders have been concerned about youth access to tobacco products more broadly and expressed support for raising the minimum age of access for tobacco products from 18 to 21 years of age. Congress recently made this change legislatively, but some want Congress to take further action to address tobacco use among youth.

- The remote sales of tobacco products—including ENDS—may be an opportunity for youth to purchase tobacco products illegally, due to difficulties in enforcing purchasing restrictions through this medium.

- Generally separate from the aforementioned public health issues, another issue concerns FDA's authority to collect tobacco user fees. More specifically, FDA has determined that it currently does not have the authority to assess user fees from ENDS manufacturers and importers, despite these products being deemed subject to FDA regulation.

These four issues are discussed in detail below, along with potential considerations for policymakers.197

ENDS: Harm Reduction Potential among Adults vs. Use among Youth, Including Flavored ENDS Use

Since the emergence of ENDS in the tobacco marketplace, there has been ongoing debate regarding their public health impact. The public health community generally views them as a harm reduction tool for adults who specifically smoke cigarettes. Harm reduction refers to the replacement of a more harmful activity with a less harmful one when elimination of the activity is difficult or infeasible. ENDS have the potential to reduce harm among adult cigarette smokers who have experienced difficulty quitting, as the aerosol from ENDS "contains fewer numbers and lower levels of most toxicants than does smoke from combustible tobacco cigarettes."198

Yet the data are complex regarding the effectiveness of ENDS as a harm reduction or cessation tool for adults who smoke cigarettes. As of early 2018, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) concluded that "there is general agreement that the number, size, and quality of studies for judging the effectiveness of e-cigarettes as cessation aids in comparison with cessation aids of proven efficacy are limited, and therefore there is insufficient evidence to permit a definitive conclusion at this time."199 Further, the long-term health effects associated with use of ENDS are still largely unknown,200 and FDA has not yet approved any ENDS products as cessation devices. In spite of these questions, many adult cigarette smokers have expressed an interest in ENDS as a way to quit cigarette smoking.201 Some argue that having adults completely switch from cigarettes to ENDS can generally be viewed as positive for the public's health, given the morbidity and mortality associated with cigarette smoking.202

However, many in the public health community are alarmed by the marked increase in use of ENDS products among youth, which are now the most popular tobacco product used among this age group.203 Research studies suggest that this change has occurred, in large part, as a result of access to flavored ENDS products.204 The availability of flavored ENDS products has created tension between industry and the public health community. Industry-funded research suggests that availability of flavored ENDS may be more appealing to adult cigarette smokers (in comparison to nonsmoking teens) and could help adult cigarette smokers quit cigarette smoking.205 Conversely, one systematic review of the literature found that both youth and adults enjoy flavors in e-cigarettes. However, the authors of this review stated that "in terms of whether flavored e-cigarettes assisted [adults] quitting smoking, we found inconclusive evidence."206 In combination, numerous studies have documented that flavors entice youth to initiate and continue using tobacco products,207 including ENDS.208 Further, the NASEM concluded that there is substantial evidence that ENDS use among youth increases the risk of such youth ever using cigarettes,209 leading to concern that tobacco control efforts that have successfully reduced cigarette smoking among both youth and adults will be diminished. The culmination of these factors raises questions about how to regulate ENDS products going forward and, specifically, how to address flavors in tobacco products (including ENDS).

In March 2019, FDA released a draft guidance document specifying its intended enforcement activities related to flavored ENDS.210 This guidance specified that FDA would prioritize enforcement of premarket review, distribution, and sale requirements related to certain flavored ENDS products that may be most accessible to youth. For example, FDA would prioritize enforcement of distribution and sale requirements in retail locations where certain flavored ENDS products may be most accessible to youth, such as in convenience stores and gas stations that do not have adult-only sections. In September 2019, FDA announced that it would finalize this guidance document "in the coming weeks," with the intention of clearing "the market of flavored e-cigarettes to reverse the deeply concerning epidemic of youth e-cigarette use."211 Delays in guidance finalization led to a Congressional hearing on December 4, 2019 to investigate the cause for delay.212 In January 2020, FDA released the final guidance document,213 with some changes compared to the draft guidance. Specifically, the March 2019 draft guidance focused enforcement of premarket authorization requirements based on how and where ENDS products are sold, while the final guidance focuses enforcement of premarket authorization requirements based on ENDS product characteristics (e.g., cartridge-based products). Some public health stakeholders expressed concern that the final guidance does not go far enough to reduce ENDS use among youth.214

In response to concerns regarding youth access to ENDS products, including flavored ENDS products, Congress may consider further limiting when flavors can be used in ENDS. Congress may also choose to outright ban all flavors (including menthol) in ENDS—as well as in other tobacco products—as some legislation introduced in the 116th Congress has proposed.215 Congress may consider proposals that reduce any tobacco product use, including ENDS, among youth while leaving the option of ENDS use open for adult cigarette smokers in order to benefit the public's health. Congress may also consider how availability of flavored tobacco products would fit into those proposals.

E-cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use-Associated Lung Injury (EVALI)

Amidst a rise in ENDS use among youth, the emergence of EVALI has raised concern among public health stakeholders, the general public, and Congress. According to CDC, data suggest that the outbreak began in June 2019. Emergency department (ED) visits reached a peak in September 2019, but have since declined. As of January 21, 2020, 60 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and DC, and 2,711 hospitalized EVALI cases have been reported to CDC in all 50 states, DC, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Among hospitalized EVALI patients with available data, 66% were male and 76% were under 35 years old.216 Further, among a subset of hospitalized EVALI patients,217 82% reported using tetrahydrocannabinol218 (THC)-containing products. Although the causes of EVALI are still unknown, laboratory data suggest that vitamin E acetate—an additive found in some THC-containing ENDS products—is closely associated with EVALI.219 Vitamin E acetate is commonly used as a dietary supplement and in skin creams. While the ingestion and dermal use of vitamin E acetate is not generally associated with adverse health effects, the safety of inhaling vitamin E acetate has not been closely examined.220

FDA and CDC, along with state and local health departments, have been working together closely to investigate the issue. FDA, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and local and state authorities have also been investigating the supply chain of ENDS associated with EVALI. FDA and DEA announced that they have seized 44 websites that were advertising the sale of illicit THC-containing vape cartridges, although none of the products advertised on the websites have been linked to any cases of EVALI.221

Such THC-containing products may raise a larger question of federal oversight pertaining to these products that are available in states permitting the sale of marijuana for recreational or medicinal purposes. Marijuana—including marijuana-derived compounds such as THC—is an illicit substance at the federal level subject to DEA enforcement and regulatory control.222 However, some states have implemented their own laws on marijuana pertaining to recreational and medicinal use, and the DEA has largely focused resources on criminal networks involved in the illicit marijuana trade.223 Therefore, THC-containing ENDS products available for sale in states that are allowing recreational and medicinal marijuana may not be the focus of DEA's current enforcement efforts and regulation. Further, ENDS products that do not contain any components, parts, or accessories that are derived from tobacco (e.g., do not contain nicotine) and are not expected to be consumed like a tobacco product may not meet the definition of a tobacco product under the FFDCA. Therefore, such products may not be subject to FDA regulatory requirements pertaining to tobacco products. FDA has indicated that the agency would regulate such products on a "case-by-case basis, based on the totality of the circumstances."224

Tobacco to 21

Many public health stakeholders have been concerned about youth access to tobacco products more broadly and expressed support for raising the minimum age of purchasing tobacco products from 18 to 21. Numerous scientific studies and Surgeon General Reports have documented that tobacco product use often begins before the age of 18.225 Nearly 90% of cigarette smokers have tried their first cigarette by age 18, and 98% have tried their first cigarette by age 26.226

The TCA required FDA to commission a report on the public health impact of raising the minimum age of tobacco product sales.227 FDA contracted with the Institute of Medicine (now known as the National Academy of Medicine), and concluded in a 2015 report that "increasing the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products will likely prevent or delay the initiation of tobacco use by adolescents and young adults."228 However, the report noted that "the impact on initiation of tobacco use of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products to 21 will likely be substantially higher than raising it to 19, but the added effect of raising the minimum age of legal access beyond age 21 to age 25 will likely be considerably smaller."229

In FY2020 appropriations, Congress amended the FFDCA to raise the federal minimum age of tobacco product sales to 21. FDA is also required to update its regulations by June 20, 2020 to reflect the new federal minimum age of tobacco purchasing, as well as the federal minimum age verification requirement (age verification required for individuals less than 30 years of age). The final rule is required to take effect by September 20, 2020.230 While public health stakeholders view this development in a positive light, some are concerned that the tobacco industry supported this initiative to avoid other measures that could also curb tobacco use—including ENDS use—among youth.231

Remote Sales

Related to the issue of youth access to tobacco products—including ENDS—some have identified remote sales (i.e., non-face-to-face sales) as an opportunity for minors to illegally purchase tobacco products, due to difficulties in enforcing purchasing restrictions through this medium. While the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking (PACT) Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-154) placed certain restrictions on remote sales of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, it did not outright prohibit them. Further, the PACT Act limits the ability of states and local governments to regulate the delivery carriers involved in remote sales—complicating enforcement efforts—and did not place such restrictions on other tobacco products, such as ENDS.232

Section 906 of the FFDCA requires FDA to promulgate regulations on remote sales of tobacco products, including age verification requirements. In 2011, FDA issued an ANPRM regarding remote sales and distribution of tobacco products,233 but has not taken further regulatory action since that time.