Role of Congress

Congress is responsible for funding, establishing rules regulating the Army, and conducting oversight of a number of functions including manning, equipping, training, and readiness. On an annual basis, shortly after the President's Budget Request is transmitted to Congress, congressional defense authorizing committees and subcommittees typically hold three separate oversight hearings focused on (1). the Army's budget request; (2). the Army's posture; and (3). Army modernization. In addition to these three hearings, Congress sometimes conducts additional hearings on a wide variety of topics to include specific weapons systems under development and other Army efforts, programs, or initiatives. The Army's 2019 Modernization Strategy, intended to guide Army modernization efforts through at least 2035, is arguably ambitious and proposes the development of a number of new weapons systems and capabilities that could also have implications for force structure as well. In its oversight role of the Army's modernization process, Congress may consider a common oversight architecture that provides both an element of continuity for hearings and a standard by which Congress might evaluate the efficacy of the Army Modernization Plan.

What is the Purpose of the Army's Modernization Strategy?1

The 2019 Army Modernization Strategy (AMS) aims to transform the Army into a force that can operate in the air, land, maritime, space, and cyberspace domains (i.e. multi-domain), by 2035. The previous 2018 AMS Report to Congress introduced the Army's six materiel modernization priorities (see below). The 2019 AMS expands the Army's approach beyond those six priorities, outlining a more holistic approach to modernization while maintaining the Army's six Materiel Modernization Priorities from the 2018 AMS. Army Modernization involves modernizing 1) how they fight (doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures); 2) what they fight with (equipment); and 3) who they are (Army culture and personnel). This report will focus on the "what they fight with" component of Army Modernization as well as associated force structure issues.

|

Army's Six Materiel Modernization Priorities 1. Long Range Precision Fires: long-range artillery/munitions and missiles. 2. Next Generation of Combat Vehicles: M-2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle replacement and associated manned and unmanned ground combat systems. 3. Future Vertical Lift: replacements for current Army reconnaissance, utility, and attack helicopters and fixed wing assets. 4. Army Network: command, control, communications, computers and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems. 5. Air and Missile Defense: systems to protect Army ground forces against a range of air and missile threats. 6. Soldier Lethality: new individual and crew-served weapons including night vision and other weapon target acquisition technologies.2 |

Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)3

The Army wants to transform itself into a force capable of implementing its new proposed operational concept referred to as Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) described below.

|

What are Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) According to the Army, current doctrine is still based on the Air-Land Battle concept developed in 1981to counter Warsaw Pact forces in Europe.4 To execute Air-Land Battle, the Army developed what is referred to as the "Big Five": the M-1 Abrams tank, the M-2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, the Patriot air defense system, and the UH-60 Blackhawk utility helicopter. Air-Land Battle is based operations in two domains—air and land.5 Currently: Competitors now possess increasingly capable anti-access and area denial strategies, meant to separate alliances politically, and the joint force physically and functionally. Further, near-peer competitors are capable of securing strategic objectives short of armed conflict with the U.S. and allies. More importantly, the Army can no longer guarantee continued overmatch over a near-peer threat -- an advantage that the U.S. has held for decades. Unlike Air-Land Battle, Multi Domain Operations (MDO) addresses that competition and conflict occur in multiple domains (land, air, sea, cyber, and space) and that there will be multiple threats across the competition continuum in the future operating environment. As the MDO concept continues to be refined and updated, it will drive Army modernization.6 (Emphasis added.) Conceptually, the Army, as an element of the Joint Force, conducts MDO (not necessarily in every domain at each moment) in order to prevail in competition. If it becomes necessary, Army forces would penetrate and dis-integrate enemy anti-access area denial (A2AD)7 systems and, if successful, exploit any resulting freedom of maneuver to achieve strategic objectives (win) and force a return to competition on favorable terms.8 |

MDO Challenges 9

According to the Army, in order to successfully execute MDO, the Army will need to change how it physically postures the force and how it organizes units. In addition, the Army says it will require new authorities and the ability to employ new capabilities and emerging technologies. The Army, in addition to integrating fully with the other Services, will need access to national-level capabilities and require a high level of day-to-day Interagency10 involvement to successfully prosecute MDO. In this regard, MDO would require not only Department of Defense (DOD) "buy in" and resources, but would also need similar support from the other members of the Interagency and Congress as well.

National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, National Military Strategy, and the Army Strategy11

The Army's Modernization Strategy is part of a hierarchy of strategies intended, among other things, to inform the Service's respective modernization plans. These strategies include:

- National Security Strategy (NSS): published by the Administration, it is intended to be a comprehensive declaration of global interests, goals, and objectives of the United States relevant to national security.

- National Defense Strategy (NDS): published by DOD, it establishes objectives for military planning in terms of force structure, force modernization, business processes, infrastructure, and required resources (funding and manpower).

- National Military Strategy (NMS): published by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS), it supports the aims of the NSS and implements the NDS. It describes the Armed Forces' plan to achieve military objectives in the near term and provides the vision for ensuring they remain decisive in the future. The NMS is a classified document.

- The Army Strategy: articulates how the Army achieves its objectives and fulfills its Title 10 duties to organize, train, and equip the Army for sustained ground combat. The Army Strategy provides guidance for budget planning and programming across multiple Future Year Defense Programs (FYDP).12

All strategies share a common theme, that of "return to great power competition" which posits that "Russia and China are competitors to the United States and both nations are looking to overturn the current rules-based international order."13 This requires the U.S. military to focus its doctrine and resources on countering this perceived threat.14 In this regard, the aforementioned strategies also re-focus the Service's modernization efforts towards defeating the perceived Chinese and Russian military threat.

A Potential Oversight Framework

As previously noted, the possibility exists for a variety of Army Modernization-hearings spanning a number of different Congresses. In this regard, a common oversight architecture could potentially provide both an element of continuity and a means by which Congress might evaluate the progress of the Army's modernization efforts. Such a potential architecture might examine:

- Is the Army's Modernization Strategy appropriate given the current and projected national security environment?

- Is the Army's Modernization Strategy achievable given a number of related concerns?

- Is the Army's Modernization Strategy affordable given current and predicted future resource considerations?

To support this potential oversight architecture, a number of topics for discussion are provided for congressional consideration.

Is the Army's Modernization Strategy Appropriate?

Does the Army's Modernization Strategy Support the National Security, National Defense, and National Military Strategies?

The Army contends its modernization strategy addresses the challenges of the future operational environment and directly supports the 2018 National Defense Strategy's (NDS) line of effort, "Build a More Lethal Force."15 The congressionally established Commission on the National Defense Strategy for the United States (Section 942, P.L. 114-328) questions this assertion, noting:

We came away troubled by the lack of unity among senior civilian and military leaders in their descriptions of how the objectives described in the NDS are supported by the Department's readiness, force structure, and modernization priorities, as described in the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) and other documents.16 (Emphasis added.)

While the Commission's finding is directed at DOD as a whole, it suggests there are questions concerning how modernization priorities and plans support the National Defense Strategy and, by association, the National Security and Military strategies as well. While the aforementioned strategic documents all feature the central theme of "return to great power competition" vis-à-vis Russia and China, it is not readily apparent to many observers how the Army's modernization priorities directly support this goal. In this regard, a more detailed examination of the Army's new Modernization Strategy's alignment with the National Security, National Defense, and National Military Strategies could prove beneficial to policymakers.

Does the Army's Modernization Strategy Address the Military Strategies of Peer Competitors?

While it can be considered essential that the Army's Modernization Strategy aligns with and supports the National Security, National Defense, and National Military strategies of the United States, it can be argued that of equal importance is whether the Army's Modernization Strategy takes into account the military strategies of peer competitors. A May 2019 study offers a summary of Russian and Chinese strategies and suggests a U.S. response:

The core of both countries' challenge to the U.S. military lies in what are commonly called anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) systems: in more colloquial terms, a wide variety of missiles, air defenses, and electronic capabilities that could destroy or neutralize U.S. and allied bases, surface vessels, ground forces, satellites, and key logistics nodes within their reach. Both China and Russia have also developed rapidly deployable and fearsomely armed conventional forces that can exploit the openings that their A2/AD systems could create.

Despite these advances, both China and Russia still know that, for now, they would be defeated if their attacks triggered a full response by the United States. The key for them is to attack and fight in a way that Washington restrains itself enough for them to secure their gains. This means ensuring that the war is fought on limited terms such that the United States will not see fit to bring to bear its full weight. Focused attacks designed to pick off vulnerable members of Washington's alliance network are the ideal offensive strategy in the nuclear age, in which no one can countenance the consequences of total war.

The most pointed form of such a limited war strategy is the fait accompli. Such an approach involves an attacker seizing territory before the defender and its patron can react sufficiently and then making sure that the counterattack needed to eject it would be so risky, costly, and aggressive that the United States would balk at mounting it—not least because its allies might see it as unjustified and refuse to support it. Such a war plan, if skillfully carried out in the Baltics or Taiwan, could checkmate the United States.

The U.S. military must shift from one that surges to battlefields well after the enemy has moved to one that can delay, degrade, and ideally deny an adversary's attempt to establish a fait accompli from the very beginning of hostilities and then defeat its invasion. This will require a military that, instead of methodically establishing overwhelming dominance in an active theater before pushing the enemy back, can immediately blunt the enemy's attacks and then defeat its strategy even without such dominance.17

From an operational perspective, new systems developed as part of the Army's Modernization Strategy would potentially need to not only provide a technological improvement over legacy systems but also support the Army's operational concept—in this case Multi Domain Operations (MDO)—intended to counter Russia and China. A detailed examination of how these systems directly counter Russian and Chinese military capabilities and strategies could prove beneficial to policymakers.

Is the Army's Modernization Strategy Relevant to Other Potential Military Challenges?

In February 2011, then-Secretary of Defense Robert Gates told West Point Cadets;

We can't know with absolute certainty what the future of warfare will hold, but we do know it will be exceedingly complex, unpredictable, and—as they say in the staff colleges—"unstructured." Just think about the range of security challenges we face right now beyond Iraq and Afghanistan: terrorism and terrorists in search of weapons of mass destruction, Iran, North Korea, military modernization programs in Russia and China, failed and failing states, revolution in the Middle East, cyber, piracy, proliferation, natural and man-made disasters, and more. And I must tell you, when it comes to predicting the nature and location of our next military engagements, since Vietnam, our record has been perfect. We have never once gotten it right, from the Mayaguez to Grenada, Panama, Somalia, the Balkans, Haiti, Kuwait, Iraq, and more—we had no idea a year before any of these missions that we would be so engaged.18

If former Secretary of Defense Gates' admonition that we have never accurately predicted our next military engagement holds true, it is a distinct possibility that a direct conventional confrontation with Russia or China posited by the National Security Strategy might not come to pass. In the case of China, it has been suggested it is more likely U.S. and Chinese interests will clash in the form of proxy wars and insurgencies as opposed to a great power war.19 The recent U.S.—Iranian confrontation is an example of such a non-great power military challenge with the potential for a rapid escalation or a protracted proxy war. With this in mind, some may consider any strategy not relevant to other potential military challenges other than great power war to be ill-conceived. To insure the Army's new Modernization Strategy is relevant, an examination of how its applies to potential adversaries other than China and Russia as well as other possible military challenges not related to great power competition could be useful to policymakers.

Does the Army's Modernization Strategy Complement the Other Service's Modernization Strategies?

According to the Army's Strategy:

The Army Mission—our purpose—remains constant: To deploy, fight, and win our Nation's wars by providing ready, prompt, and sustained land dominance by Army forces across the full spectrum of conflict as part of the Joint Force.20

As part of this Joint Force, it can be argued the Army's Modernization Strategy should complement the modernization strategies of the other Services and vice versa. In order for the Service's modernization strategies to complement one another, a joint war-fighting concept is essential and, at present, no such a concept is agreed by all Services.21 According to the Army:

A Joint war-fighting concept would provide a common framework for experimentation and validation of how the joint force must fight, what capabilities each of the services must have, and how the Joint force should be organized—further allowing civilian leaders to make cross-service resource decisions.22

While the Army favors and is promoting MDO for adoption by the other Services, the Air Force is focusing on Multi Domain Command and Control, the Navy on Distributed Maritime Operations, and the Marine Corps on the Marine Corps Operating Concept.23 While these operating concepts share some common themes such as great power competition and a need to be able to operate in a variety of domains, they differ in approach but not to an extent where a common joint warfighting concept could not be agreed upon.

Despite this lack of a common joint warfighting concept, the Army claims its modernization programs are aligned with the other Services.24 Army leadership has noted that "the three of us [Army, Air Force, and the Department of the Navy] are completely aligned," citing the "development of a hypersonic weapon as a good example."25 While the Army might be collaborating now more than ever with the Air Force and Navy as it claims, collaborating at the programmatic level does not necessarily constitute a complementary relationship of the Service's modernization strategies. In this regard, Congress might decide to examine the relationship between the Service's modernization strategies to insure they are complementary.

Is the Army's Modernization Strategy Achievable?

What is the Scope of the Army's Modernization Strategy?

Army officials reportedly have identified 31 modernization initiatives—not all of them programs of record—intended to support the Army's six modernization priorities.26 The Army notes that "there are interdependencies among the 31 initiatives which need to fit together in an overall operational architecture."27 Examples of a few of the higher-visibility initiatives grouped by modernization priority include:

- Long Range Precision Fires:

- Strategic Long Range Cannon (SLRC).

- Precision Strike Missile (PrSM).

- Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA).

- Next Generation Combat Vehicle: (NGCV):

- Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV).

- Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV): 3 variants.

- Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV).

- Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF).

- Decisive Lethality Platform (DLP).

- Future Vertical Lift:

- Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA).

- Future Attack Unmanned System (FUAS).

- Future Long Range Assault Aircraft.

- Air And Missile Defense:

- Maneuver Short-Range Air defense (M-SHORAD).

- Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC).

- Soldier Lethality:

- Next Generation Squad Weapons – Automatic Rifle (NGSW-AR).

- Next Generation Squad Weapons – Rifle (NGSW-R).

While some of these initiatives are currently in development and procurement, others are still in the requirements definition and conceptual phase. With so many initiatives and interdependencies, it is reasonable to ask "can the Army's modernization effort survive the failure of one or more of the 31 initiatives?"28 Another potential way of gauging if the Army is "overreaching" would be to establish how much modernization is required before the Army considers itself sufficiently modernized to successfully implement MDO as currently envisioned. One question for the Army might be "What are the Army's absolute "must-have" systems or capabilities to ensure the Army can execute MDO at its most basic level?"

Are the Army's Modernization Priorities Correct?

In March 2019 testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee, then Secretary of the Army Mark Esper and Chief of Staff of the Army Mark Milley stated:

To guide Army Futures Command, the Army established a clear set of modernization priorities that emphasize rapid maneuver, overwhelming fires, tactical innovation, and mission command. Our six modernization priorities will not change, and they underscore the Army's commitment to innovate for the future. We have one simple focus—to make Soldiers and units more capable and lethal. Over the last year, we identified $16.1B in legacy equipment programs that we could reinvest towards 31 signature systems that are critical to realizing Multi-Domain Operations and are aligned with these priorities.29

While the Army's prioritization of and commitment to its modernization initiatives can be viewed as essential to both resourcing and executing the Army's Modernization Strategy, some defense experts have questioned the Army's modernization priorities.

For example, the Heritage Foundation's August 2019 report "Rebuilding America's Military Project: The United States Army," suggests different modernization priorities:

Given the dependence of MDO on fires and the poor state of Army fire systems, the inclusion and first placement of long-range precision fires is logical. Based on the importance of the network to MDO and the current state of Army tactical networks, logically the network should come next in priority. Third, based on the severely limited current capabilities, should come air and missile defense, followed by soldier lethality in fourth. Next-generation combat vehicles are fifth; nothing has come forward to suggest that there is a technological advancement that will make a next-generation of combat vehicles significantly better. Finally, the last priority should be future vertical lift, although a persuasive argument could be made to include sustainment capabilities instead. Nowhere in the MDO concept is a compelling case made for the use of Army aviation, combined with the relative youth of Army aviation fleets.30

Aside from differing opinions from defense officials and scholars, world events might also suggest the need to re-evaluate the Army's modernization priorities. One example is the September 14, 2019 attack against Saudi Arabian oil facilities, believed to have been launched from Iran, which employed a combination of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and cruise missiles.31 It has been pointed out U.S. forces are ill-prepared to address this threat32 although the Army has a variety of programs both underway and proposed to mitigate this vulnerability. If the September 14, 2019 attacks are replicated not only in the region but elsewhere by other actors, it might make a compelling case to reprioritize Army air and missile defense from fifth out of six modernization priorities to a higher level to address an evolving and imminent threat. Apart from the Army's stated modernization priorities, there might also be other technologies or systems that merit inclusion based on changing world events.

How will the Army Manage its Modernization Strategy?

First established in 2018, Army Futures Command (AFC) is intended to:

Modernize the Army for the future-will integrate the future operational environment, threat, and technologies to develop and deliver future force requirements, designing future force organizations, and delivering materiel capabilities.33

According to the Army's 2019 Modernization Strategy:

Modernization is a continuous process requiring collaboration across the entire Army, and Army Futures Command brings unity of effort to the Army's modernization approach. AFC, under the strategic direction of Headquarters, Department of the Army (HQDA), develops and delivers future concepts, requirements, and organizational designs based on its assessment of the future operating environment. AFC works closely with the Army's modernization stakeholders to integrate and synchronize these solutions into the operational force.34

While this broad statement provides a basic modernization management concept, it does not address specific authorities and responsibilities for managing Army modernization.

Many in Congress have expressed concerns with the relationship between AFC and the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisitions, Logistics, and Technology (ASA (ALT)) who has a statutory role in the planning and resourcing of acquisition programs.35 The Senate Appropriations Committee's report accompanying it's version of the Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 2020, directs the Army to clearly define modernization responsibilities:

ARMY ACQUISITION ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The Committee has supported efforts by the Army to address modernization shortfalls and deliver critically needed capabilities to the warfighter through establishment of Cross-Functional Teams [CFTs] and ultimately the stand-up of Army Futures Command [AFC]. However, questions remain on the roles and responsibilities of AFC and the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Acquisition, Logistics & Technology) [ASA(ALT)]. As an example, the Committee recently learned of a newly created Science Advisor position within AFC, which seems to be duplicative of the longstanding role of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Research and Technology. Additionally, the Committee was concerned to learn that funding decisions on investment accounts, to include science and technology programs, would be directed by AFC rather than ASA(ALT).

While the Committee supports AFC's role in establishing requirements and synchronizing program development across the Army, it affirms that ASA(ALT) has a statutory role in the planning and resourcing of acquisition programs. The ASA(ALT) should maintain a substantive impact on the Army's long-range investments, not just serve as a final approval authority. Therefore, the Committee directs the Secretary of the Army to provide a report that outlines the roles, responsibilities, and relationships between ASA(ALT) and AFC to the congressional defense committees not later than 90 days after enactment of this act. The report shall include a clear description of the responsibilities of each organization throughout the phases of the planning, programming, budgeting, and execution of resources.36 (Emphasis added.)

While the Army has placed significant emphasis on the "revolutionary" nature of AFC and its role in modernization, questions may remain about whether AFC will provide a significant level of "value added" to Army modernization and not encroach on the statutory responsibilities of the ASA (ALT) as well as other major Army organizations having a role in modernization.

How Long Will It Take to Fully Implement the Army's Modernization Strategy?

According to the Army's 2019 Modernization Strategy, the Army plans to build a "MDO ready force by 2035."37 In order for this goal to be achieved, the Army assumes that:

- The Army's budget will remain flat, resulting in reduced spending power over time.

- Demand for Army forces will remain relatively constant while it executes this strategy.

- Research and development will mature in time to make significant improvements in Army capabilities by 2035.

- Adversary modernization programs will stay on their currently estimated trajectories in terms of capability levels and timelines.38

It is not clear if "MDO ready" equates to a "fully modernized" Army or if a certain undefined level of modernization is sufficient for the Army to successfully execute MDO. Originally, Army officials were hoping to field the M-2 Bradley replacement—the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV)—by 2026.39 They also planned to field one brigade's worth of OMFVs per year—meaning that it would have taken until 2046 to field OMFVs to all Armored Brigade Combat Teams (ABCTs).40 On January 16, 2020, the Army decided to cancel the current OMFV solicitation and revise and re-solicit the OMFV requirements on a competitive basis at an unspecified time in the future.41 Given this cancellation, it may take longer than 2046 to field all OMFVs unless significant budgetary resources are applied to the program.

With the Army's somewhat optimistic assumptions about the budget, demand for forces, mature research and development, and the pace of adversary modernization, as well as the scope and complexity of overall Army Modernization, some policymakers may raise questions about whether a full realization of Army modernization initiatives is possible by 2035.

What Kind of Force Structure Will Be Required to Support Modernization?

In order to support MDO, Army officials reportedly noted in March 2019 that the Army was preparing to make major force structure changes within the next five years.42 These force structure changes will also be needed to support Army Modernization as new weapons systems could likely require new units and might also mean that existing units are deactivated or converted to different kinds of units. Potential questions for policymakers include:

- What kinds of new units will be required as a result of Army Modernization?

- Will existing units be deactivated or converted to support Army Modernization?

- Will additional endstrength be required to support Army Modernization or will fewer soldiers be needed?

- Will new Military Operational Specialties (MOSs) be required to support Army Modernization?

- How will new units be apportioned between the Active and Reserve Components?

- Where will these new units be stationed in the United States and overseas?

- Will new training ranges or facilities be required to support Army Modernization?

Is the Army's Modernization Strategy Affordable?

Army officials have said they eliminated, reduced, or consolidated almost 200 legacy weapon systems catalogued in the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) as part of an effort to shift more than $30 billion to programs related to the "Big Six" modernization priorities.43 The budget review process, known as "Night Court," was initiated by then-Army Secretary Mark Esper.44

Army officials have said additional reviews will yield lower levels of savings.45 They have also acknowledged uncertainty in budget assumptions, including total projected funding for the service and long-term costs for modernization priorities as they shift from research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) to procurement activities. Army Lieutenant General James Pasquarette, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Army for Programs (G-8), has said:

Our strategy right now assumes a topline that's fairly flat. I'm not sure that's a good assumption. So, when the budget does go down ... will we have the nerve to make the hard choices to protect future readiness? Often that's the first lever we pull—we try and protect end-strength and current readiness at the cost of future readiness.... We don't really have a clear picture of what those bills are right now [for long-term costs of modernization priorities].... There are unrealized bills out there that we're going to have to figure out how to resource and so, right now, I think they're underestimated. 46

Some policymakers and observers have raised questions about the affordability of the Army's modernization strategy.47 This section seeks to provide context to this question by detailing the Army's requested funding for programs related to its six modernization priorities for FY2020 and the accompanying FYDP, historical and projected funding for the service's RDT&E and procurement efforts in real terms (i.e., inflation-adjusted dollars), changes in the service's budget allocations over time, and planned funding for the service's major defense acquisition programs.

Selected Army Modernization Funding in the FY2020 Budget Request

According to information provided by the Army, the service requested $8.9 billion in RDT&E and procurement funding for programs related to its six modernization priorities in FY2020.48 This amount reflects an increase of $3.9 billion (78%) from the FY2019 enacted amount of $5 billion.49 See Table 1 for a breakdown of projected funding by priority.

|

Priority |

FY2019 (Enacted) |

FY2020 (Requested) |

$ Change |

|

Future Vertical Lift |

$0.2 |

$0.8 |

$0.7 |

|

Long Range Precision Fires |

$0.4 |

$1.3 |

$0.9 |

|

Soldier Lethalitya |

$0.4 |

$1.2 |

$0.8 |

|

Air and Missile Defense |

$0.8 |

$1.4 |

$0.6 |

|

Next Generation Combat Vehicle |

$1.2 |

$2.0 |

$0.7 |

|

Networkb |

$1.9 |

$2.3 |

$0.3 |

|

Total |

$5.0 |

$8.9 |

$3.9 |

Source: Department of the Army, Army Modernization Priority FY2020 budget document, on file with the authors.

Notes: Figures rounded to the nearest tenth. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

a. Includes amounts for Soldier Lethality and Soldier Training Environment (STE).

b. Includes amounts for Network and Assured Position, Navigation, and Timing (Assured PNT).

For FY2020, the Army requested a total of $38.7 billion for its acquisition accounts, including $12.4 billion for RDT&E and $26.3 billion for procurement.50 Notably, for FY2020, funding requested for programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities, $8.9 billion, accounted for less than a quarter (23%) of its overall acquisition budget request.

Potential questions for policymakers include:

- How has the Army identified funding to pay for programs related to its six modernization priorities? What officials and organizations have been involved? What is the status of these reviews? How can the Army provide more transparency in identifying sources of funding from these reviews?

- Why does funding for programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities account for a relatively small share of its overall acquisition budget? Should the Army devote a larger share of its overall acquisition budget to its six modernization priorities? What would be some challenges in doing so? When does the Army expect to fully resource programs related to its modernization priorities?

- How much of the Army's overall acquisition budget should go toward modernization priorities, current acquisition programs, and legacy programs?

- Some programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities, such as Future Vertical Lift, saw a higher percentage increase in requested funding for FY2020 than others, such as Air and Missile Defense. Do the percentage increases reflect the level of priority the Army is assigning these individual programs—or rising costs associated with new stages of development?

- The Army's FY2020 unfunded priorities list included $242.7 million for "modernization requirements" and $403.9 million for "lethality requirements," among funding for other requirements.51 Why was the service unable to fund these requirements in its regular budget request?

Selected Army Modernization Funding in the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP)

The service projected $57.3 billion in RDT&E and procurement funding for programs related to its six modernization priorities over the FYDP from FY2020 through FY2024.52 This amount, if authorized and appropriated by Congress, would reflect an increase of $33.1 billion (137%) from projections for the five-year period in the FY2019 budget request.53 See Table 2 for a breakdown of the projected cost by program.

Table 2. Selected Army Modernization Funding by Priority, FY2019 FYDP-FY2020 FYDP (Projected)

(in billions of dollars)

|

Priority |

FY2019 FYDP |

FY2020 FYDP |

$ Change |

|

Future Vertical Lift |

$0.8 |

$4.8 |

$4.0 |

|

Long Range Precision Fires |

$1.1 |

$5.7 |

$4.6 |

|

Soldier Lethalitya |

$1.7 |

$6.7 |

$5.0 |

|

Next Generation Combat Vehicle |

$5.2 |

$13.3 |

$8.1 |

|

Networkb |

$9.0 |

$12.5 |

$3.5 |

|

Air and Missile Defense |

$6.5 |

$8.8 |

$2.3 |

|

Prototypingc |

$0.0 |

$5.7 |

$5.7 |

|

Total |

$24.2 |

$57.3 |

$33.1 |

Source: Department of the Army, Army Modernization Priority FY2020 budget document, on file with the authors.

Notes: Figures rounded to the nearest tenth. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

a. Includes amounts for Soldier Lethality and Soldier Training Environment (STE).

b. Includes amounts for Network and Assured Position, Navigation, and Timing (Assured PNT).

c. The Army budgeted $5.7 billion in funding for prototyping from FY2021 to FY2024.

For the five-year period through FY2024, the Army projected a total of $187.5 billion for its acquisition accounts (in nominal dollars), including $58.7 billion for RDT&E and $128.8 billion for procurement.54 Notably, for the FY2020 FYDP, funding for programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities accounts for less than a third (31%) of its overall acquisition budget.

In addition to the previous list, potential questions for policymakers include:

- How realistic are the Army's assumptions for funding programs related to its six modernization priorities, given uncertainty about their long-term costs and the projected decrease in real terms (i.e., inflation-adjusted dollars) in Army procurement and RTD&E funding over the Future Years Defense Program?

- Should the level of planned funding change for certain programs to reflect different priorities?

- What additional tradeoffs or divestments does the Army plan to make to its current acquisition programs or legacy weapon systems in order to fund programs related to its six modernization priorities? What programs may be cut?

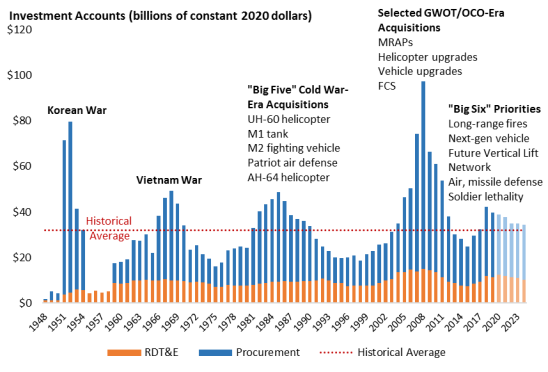

Army RDT&E and Procurement Funding: A Historical Perspective55

Taken together and adjusted for inflation (in constant FY2020 dollars), the Army's acquisition accounts—including RDT&E and procurement—have experienced several buildup and drawdown cycles in past decades, with some of the biggest increases occurring during periods of conflict. See Figure 1.

For example, the service's acquisition budget spiked in FY1952 during the Korean War, again in FY1968 during the Vietnam War, and again in FY2008 during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The FY2008 peak was driven in part by the service's procurement of Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles and other programs intended to protect troops in combat zones from roadside bombs.56

In terms of a non-war peak, the Army received a combined total of $48.7 billion (in constant FY2020 dollars) for RDT&E and procurement in FY1985 during the Cold War—an era in which the service's "Big Five" acquisition programs entered service, including the UH-60 Black Hawk utility helicopter (1979), M1 Abrams tank (1980), M2 Bradley fighting vehicle (1981), Patriot air defense system (1981), and AH-64 Apache attack helicopter (1986).

The Army projects combined RDT&E and procurement funding will continue to decline in real dollars. The combined level of funding for these accounts is projected to decline from $38.7 billion in FY2020 to $34.3 billion in FY2024 (in constant FY2020 dollars), a decrease over the FYDP of $4.4 billion (11%). Even so, the FY2024 level would remain higher than the Army's historical average of $32.2 billion (in constant FY2020 dollars) for RDT&E and procurement.

|

Figure 1. Army RDT&E and Procurement Funding, FY1948-FY2024 (in billions of constant FY2020 dollars) |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense, National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2020, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), May 2019, Table 6-19: Army Budget Authority by Public Law Title, FY2020 constant dollars for selected titles, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2020/FY20_Green_Book.pdf; CRS research. Notes: Lighter shading reflects projected funding. Includes discretionary and mandatory budget authority. RDT&E is research, development, test, and evaluation; GWOT is global war on terrorism; OCO is overseas contingency operations; MRAP is mine-resistant ambush-protected; FCS is Future Combat Systems. |

Potential questions for policymakers include:

- How may the projected decrease in RDT&E and procurement funding in constant FY2020 dollars over the Future Years Defense Program impact the Army's ability to execute its modernization strategy?

- If the Army's overall acquisition budget is projected to decrease (in real terms), and funding for programs related to its modernization strategy is projected to increase, what kinds of tradeoffs or divestments does the Army plan to make to its current acquisition programs or legacy weapon systems?

- How much, if any, of the increase in RDT&E and procurement funding in FY2018 went to programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities?

- To what extent will projected costs for programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities increase as they shift from RDT&E to procurement activities?

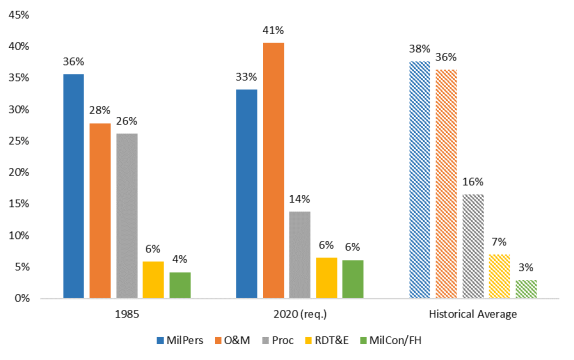

Changes in Army Budget Allocations

The share of funding that the Congress has allocated to Army appropriations accounts has changed over time. Because every dollar spent on military personnel, operation and maintenance, and military construction is a dollar that cannot be spent on RDT&E or procurement, Army budget allocation decisions may impact the service's ability to execute its modernization strategy.

For example, the Army uses funds from its Operation and Maintenance (O&M) account to pay the salaries and benefits of most of its civilian employees, train soldiers, and purchase goods and services, from fuel and office supplies to health care and family support. (Today, the account also covers most of the service's costs for Overseas Contingency Operations, or OCO.57) In FY1985, during the Reagan-era buildup, O&M accounted for a smaller share of the Army budget (28%) than it does today (41%) and than it has historically (36%). In the same year, procurement accounted for a larger share of the Army budget (26%) than it does today (14%) and than it has historically (16%). See Figure 2.

|

Figure 2. Army Budget Authority by Public Law Title for Selected Fiscal Years (as a percentage of the total) |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense, National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2020, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), May 2019, Table 6-19: Army Budget Authority by Public Law Title, percentages of current dollars for selected titles, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2020/FY20_Green_Book.pdf; CRS research. Notes: MilPers is military personnel; O&M is operation and maintenance; Proc is procurement; RDT&E is research, development, test, and evaluation; MilCon/FH is military construction and family housing (percentages combined); req. is requested. Figure excludes certain other titles, such as revolving and management funds. |

Potential questions for policymakers include:

- What changes in spending on military personnel could impact the Army's ability to execute its modernization strategy, particularly if the service increases end-strength?

- What changes in spending on operations and maintenance could impact the Army's ability to execute its modernization strategy?

- What changes in spending on Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) could impact the Army's ability to execute its modernization strategy?

- How is the Army reviewing potential ways to control military personnel or operations and maintenance costs to be able to spend more on RDT&E and procurement in support of programs related to its modernization strategy?

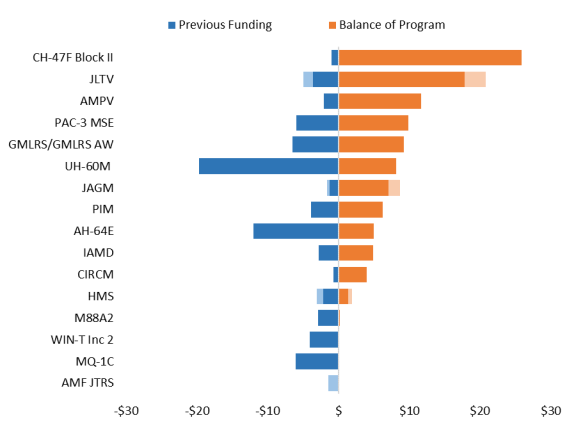

Planned Funding for Current Army Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAPs)

Including funding planned for FY2020 and FY2021 as part of the FY2020 President's budget request, the Army has an outstanding balance of $120.6 billion (in then-year dollars) for current major defense acquisition programs.58 Programs with balances greater than $10 billion include the following:

- CH-47F. The CH-47F Chinook Block II modernization program is intended to increase the carrying capacity of the cargo helicopter in part by upgrading its rotor blades and flight control and drive train components (estimated balance: $25.9 billion);

- Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV).59 This program is intended to replace a portion of the Humvee fleet with a new light-duty vehicle (estimated balance: $20.8 billion, $3 billion of which is projected to come from services other than the Army); and

- Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV).60 This program is intended to replace the M113 armored personnel carrier family of vehicles with a new armored vehicle (estimated balance: $11.7 billion).61

For the cumulative funding status of each of the Army's current major defense acquisition programs as of the FY2020 President's budget request, including prior-year amounts and outstanding balances, see Figure 3.

|

Figure 3. Funding Status of Current Army Major Defense Acquisition Programs (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense, Comprehensive Selected Acquisition Reports for the Annual 2018 Reporting Requirement as Updated by the President's Fiscal Year 2020 Budget, August 1, 2019, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/1923492/department-of-defense-selected-acquisition-reports-sars-december-2018/. Notes: Lighter shading reflects other service funding. Balance of program includes funding planned for FY2020 and FY2021 as part of the FY2020 President's budget request. CH-47 Block II refers to the Chinook cargo helicopter; JLTV is Joint Light Tactical Vehicle; AMPV is Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle; PAC-3 MSE is Patriot Advanced Capability-3 Missile Segment Enhancement; GMLRS is Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System and AW is Alternative Warhead; UH-60M refers to the Black Hawk utility helicopter; HMS is Handheld, Manpack and Small Form Fit; JAGM is Joint Air-to-Ground Missile; PIM is Paladin Integrated Management; AH-64E refers to the Apache attack helicopter and includes amounts for new build and remanufacture; IAMD is Integrated Air and Missile Defense; CIRCM is Common Infrared Countermeasure; M88A2 refers to the Hercules armored recovery vehicle; WIN-T is Warfighter Information Network-Tactical; MQ-1C refers to the Gray Eagle unmanned aerial vehicle; and AMF JTRS is Airborne, Maritime, Fixed Station segment of the Joint Tactical Radio System. |

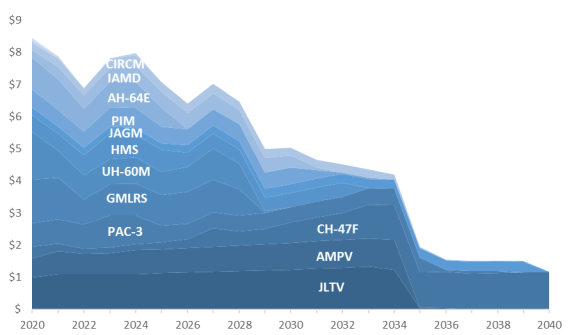

For projected funding for each of the Army's current major defense acquisition programs as of the FY2020 President's budget request, see Figure 4.62

|

Figure 4. Planned Funding for Current Army Major Defense Acquisition Programs, FY2020-FY2040 (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Executive Services Directorate, FOIA Reading Room, Selected Acquisition Reports as of the FY2020 President's budget request, https://www.esd.whs.mil/FOIA/Reading-Room/Reading-Room-List_2/Selected_Acquisition_Reports/, accessed December 2019. Notes: Amounts include Army procurement and research, development, test, and evaluation funding for selected years, and exclude other service funding. JLTV is Joint Light Tactical Vehicle; AMPV is Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle; CH-47F refers to Block II upgrades for the Chinook cargo helicopter; PAC-3 is Patriot Advanced Capability-3 Missile Segment Enhancement; GMLRS is Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System; UH-60M refers to the Black Hawk utility helicopter variant; HMS is Handheld, Manpack and Small Form Fit; JAGM is Joint Air-to-Ground Missile; PIM is Paladin Integrated Management; AH-64E refers to the Apache attack helicopter variant and includes amounts for new build and remanufacture; IAMD is Integrated Air and Missile Defense; and CIRCM is Common Infrared Countermeasure. Included but not labeled: M88A2 Hercules armored recovery vehicle, Warfighter Information Network-Tactical (WIN-T); MQ-1C Gray Eagle unmanned aerial vehicle; and Airborne, Maritime, Fixed Station segment of the Joint Tactical Radio System (AMF JTRS). |

As part of the FY2020 President's budget request, the Army proposed reducing funding for some current modernization programs, including the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) and the Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), in part to pay for modernization priorities.63

As previously discussed, DOD has not yet designated many of the programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities as major defense acquisition programs (MDAPs).64 However, DOD appears to have designated as pre-major defense acquisition programs (pre-MDAPs) some programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities, such as Future Vertical Lift.65 When possible, the Army plans to begin equipping units with technology on a limited basis in coming years in advance of fully equipping units to take advantage of new technologies as soon as practicable.66 See Table 3.

Table 3. Projected First Unit Equipped (FUE) Dates for Selected Army Modernization Programs

(by fiscal year)

|

2021 |

Mobile Short Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD) |

Air and Missile Defense |

|

Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) |

Soldier Lethality |

|

|

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) |

Next-Generation Combat Vehicle |

|

|

2022 |

Army Integrated Air and Missile Defense (AIAMD) |

Air and Missile Defense |

|

Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor (LTAMDS) |

||

|

2023 |

Next Generation Squad Weapon--Automatic Rifle (NGSW-AR) |

Soldier Lethality |

|

Next Generation Squad Weapon--Rifle (NGSW-R) |

||

|

Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW; prototype) |

Long Range Precision Fires |

|

|

Precision Strike Missile (PrSM; initial prototype flight) |

||

|

2025 |

Strategic Long Range Cannon (SLRC; prototype) |

|

|

Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF) |

Next-Generation Combat Vehicle |

|

|

2026 |

Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) |

|

|

2030 |

Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) |

Future Vertical Lift |

|

Future Long Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) |

Source: CRS communications with U.S. Army.

Potential questions for policymakers include:

- How do programs included in the Army's six modernization priorities relate to current major defense acquisition programs?

- Should the Army fund certain current major defense acquisition programs, such as Integrated Air and Missile Defense, at higher levels to better conform to programs related to its six modernization priorities?

- How may resourcing requirements for programs related to the Army's six modernization priorities impact funding for its current major defense acquisition programs?

Given the rapidly changing and unpredictable security challenges facing the United States and the scope of the Army's modernization program, congressional oversight could be challenged in the future as the Army attempts to develop and field an array technologies and systems. A potential oversight framework which constantly evaluates the relevance, the feasibility, and affordability of the Army's modernization efforts could benefit both congressional oversight and related budgetary activities.