The Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA) altered federal offshore oil and gas leasing policy in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico.1 The law imposed an oil and gas leasing moratorium through June 30, 2022, throughout most of the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (off the Florida coast) and a small part of the Central Gulf.2 In other parts of the Gulf of Mexico, the law established a framework for sharing revenues from certain qualified oil and gas leases with the "Gulf producing states" of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas, as well as with a nationwide outdoor recreation program—the Land and Water Conservation Fund's (LWCF's) state assistance program.3

Several aspects of GOMESA have generated interest in the 116th Congress.4 As the 2022 expiration date for the leasing moratorium in the Eastern Gulf approaches,5 the Department of the Interior's (DOI's) Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has begun to plan for offshore leasing in this area following the moratorium's expiration. BOEM's draft proposed five-year oil and gas leasing program for 2019-2024 would schedule new lease sales in the expired moratorium area starting in 2023.6 Some Members of Congress seek to forestall new lease sales by extending the moratorium beyond 2022; others support allowing it to expire on the currently scheduled date. On September 11, 2019, the House passed H.R. 205, which would make the GOMESA moratorium permanent. Congress is weighing the potential for development of hydrocarbon resources in the Eastern Gulf against competing uses of the area for military testing and training, commercial fishing, and recreation. The debate encompasses questions of regional economic livelihoods and national energy and military security, as well as environmental concerns centered on the threat of oil spills and the potential contributions to climate change of oil and gas development.

GOMESA's revenue-sharing provisions also have generated debate and interest in the 116th Congress. The law entered a second revenue-sharing phase in FY2017—often referred to as GOMESA's "Phase II"—in which qualified leasing revenues from an expanded geographic area are shared with the states and with the LWCF. Phase II has resulted in higher revenue shares than in the law's first decade (FY2007-FY2016). Revenue sharing from the added Phase II areas is capped for most years at $500 million annually for the Gulf producing states and the LWCF combined, and some Members of Congress seek to raise or eliminate this cap. In the 115th Congress, P.L. 115-97 increased the cap to $650 million for FY2020 and FY2021.7 In addition to changing the cap, some Members have advocated to increase the percentage of revenues shared with the Gulf Coast states and to increase the set of qualified leases from which revenues can be shared, as well as to add an additional state (Florida) to the revenue-sharing arrangement. Other bills have proposed new uses of Gulf oil and gas revenues for various federal programs and purposes outside of revenue sharing, and some stakeholders have proposed to end GOMESA state revenue sharing altogether. Debate has centered on the extent to which these revenues should be shared with coastal states versus used for broader federal purposes, such as deficit reduction or nationwide federal conservation programs. Some Members of Congress and other stakeholders have made the case that the coastal states should receive a higher revenue share, given costs incurred by these states and localities to support extraction activities. These stakeholders have compared GOMESA revenue sharing with the onshore federal revenue-sharing program, where states receive a higher share of the federal leasing revenues than is provided under the GOMESA framework. Other Members of Congress, as well as the Obama and Trump Administrations at times, have contended that revenues generated in federal waters belong to all Americans and that revenue distribution should reflect broader national needs.

This report provides brief background on Gulf of Mexico oil and gas development, discusses key provisions of GOMESA, and explores issues related to the Eastern Gulf moratorium and Gulf state revenue sharing. The report discusses various legislative options and proposals for amending GOMESA, as well as scenarios for future leasing if the law continues unchanged.

Background

The Gulf of Mexico has the most mature oil and gas development infrastructure on the U.S. outer continental shelf (OCS), and almost all U.S. offshore oil and gas production (approximately 98%) takes place in this region.8 Additionally, the Gulf contains the highest levels of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil and gas resources of any U.S. OCS region, according to BOEM.9 The Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) estimated federal revenues from offshore oil and gas leases in the Gulf at $5.51 billion for FY2019, out of a total of $5.57 billion for all OCS areas (Table 1).10 From FY2009 to FY2018, annual revenues from federal leases in the Gulf ranged from a high of $8.74 billion in FY2013 (out of $9.07 billion total OCS oil and gas revenues for that year) to a low of $2.76 billion in FY2016 (out of $2.79 billion total OCS oil and gas revenues for that year). Changing prices for oil and gas are the most significant factors in these revenue swings.

BOEM divides the Gulf into three planning areas: Eastern, Central, and Western. Most of the oil and gas development has taken place in the Central and Western Gulf planning areas. This is due to stronger oil and gas resources in those areas (as compared with the Eastern Gulf) and to leasing restrictions in the Eastern Gulf imposed by statutes and executive orders even before GOMESA's enactment.

Table 1. Annual Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Oil and Gas Revenues: Gulf of Mexico Share of Total, FY2009-FY2019

($ in billions)

|

FY2009a |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

|

|

Gulf |

4.88 |

5.60 |

6.22 |

6.55 |

8.74 |

7.10 |

4.93 |

2.76 |

3.50 |

4.65 |

5.51 |

|

Total |

5.13 |

5.90 |

6.54 |

6.87 |

9.07 |

7.39 |

5.08 |

2.79 |

3.53 |

4.70 |

5.57 |

Source: Department of the Interior (DOI), Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR), "Natural Resources Revenue Data: Data Query Tool," at https://revenuedata.doi.gov/query-data/?dataType=Revenue.

Notes: Dollar amounts are nominal (not adjusted for inflation). The table shows total OCS revenues from oil and gas activities and the portion of those revenues derived from activities in the Gulf of Mexico. Includes revenues from the ONRR commodity categories Oil, Oil & Gas, Gas, and NGL (natural gas liquids). Revenue totals include bonus bids, rents, and royalties.

a. Table begins with FY2009 because this was the first year of revenue distributions under the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act (GOMESA; 43 U.S.C. §1331 note). See Table 3 for more information.

Eastern Gulf Leasing Prohibitions Prior to GOMESA

Congressional leasing restrictions in some parts of the Eastern Gulf date from the 1980s. Prompted by concerns of some coastal states, fishing groups, and environmentalists, Congress mandated a series of leasing moratoria in certain parts of the OCS, which grew to include the Eastern Gulf of Mexico. The FY1984 Interior Appropriations Act prohibited leasing in any Eastern Gulf areas within 30 nautical miles of the baseline of the territorial sea and in other specified Eastern Gulf blocks.11 From FY1989 through FY2008, the annual Interior appropriations laws consistently included moratoria in the portion of the Eastern Gulf south of 26° N latitude and east of 86° W longitude.

Separately, President George H. W. Bush issued a presidential directive in 1990 ordering DOI not to conduct offshore leasing or preleasing activity in multiple parts of the OCS—including portions of the Eastern Gulf—until after 2000.12 In 1998, President Bill Clinton used his authority under Section 12(a) of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) to extend the presidential offshore leasing prohibitions until 2012.13 President Clinton's order expanded the portion of the Eastern Gulf withdrawn from leasing consideration.14 The withdrawals designated during the Clinton Administration lasted until President George W. Bush modified them in 2008 to open multiple withdrawn areas to leasing.15 By that time, GOMESA had been enacted, so President Bush's action did not open the Eastern Gulf moratorium area to leasing.

Distribution of Gulf Revenues Prior to GOMESA

Before GOMESA's enactment, federal revenues from oil and gas leasing in most parts of the Gulf were not shared with coastal states. The exception was revenue from leases in certain nearshore federal waters: under Section 8(g) of the OCSLA (as amended), states receive 27% of all OCS receipts from leases lying wholly or partly within 3 nautical miles of state waters.16 Gulf Coast states argued for a greater share of the OCS revenues based on the significant effects of oil and gas development on their coastal infrastructures and environments. The states compared the offshore revenue framework to that for onshore public domain leases. Under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, which governs onshore oil and gas development, states generally receive 50% of all rents, bonuses, and royalties collected throughout the state, less administrative costs.17

GOMESA's Provisions

GOMESA was signed into law on December 20, 2006.18 Sections 101 and 102 of the law contain a short title and definitions. Section 103 directs that two areas in the Central and Eastern Gulf be offered for oil and gas leasing shortly after enactment.19 These mandated lease sales took place in 2007-2009, and this provision of GOMESA has not been a focus of current congressional interest. Current interest has focused on Section 104 of the law, which imposes a moratorium on oil and gas leasing in certain parts of the Gulf, and Section 105, which contains provisions for revenue sharing from qualified leases with four states and their coastal political subdivisions, as well as with the LWCF's state assistance program.

Section 104: Eastern Gulf Moratorium

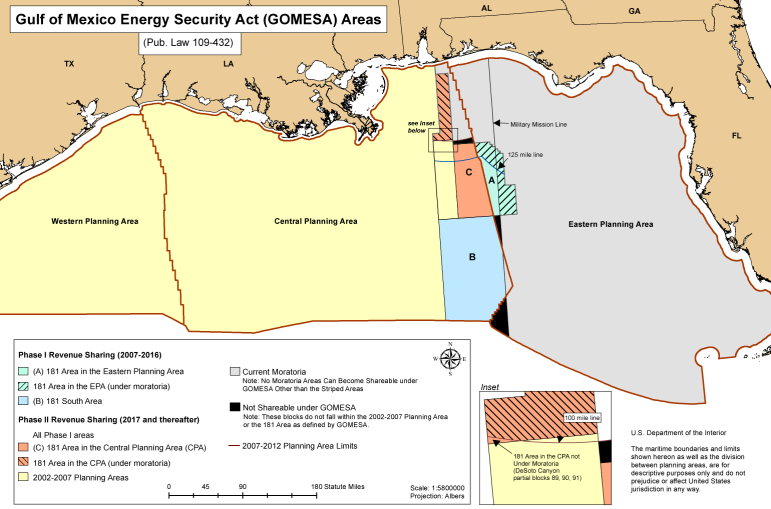

Section 104 of GOMESA states that, from the date of the law's enactment through June 30, 2022, the Secretary of the Interior is prohibited from offering certain areas, primarily in the Eastern Gulf, for "leasing, preleasing, or any related activity." The moratorium encompasses (1) areas east of a designated Military Mission Line, defined in the law as the north-south line at 86°41ʹ W longitude;20 (2) all parts of the Eastern Gulf planning area that lie within 125 miles of the Florida coast; and (3) certain portions of the Central Gulf planning area, including any parts within 100 miles of the Florida coast, as well as other specified areas. The resulting total moratorium formed by these overlapping areas is shown in gray in Figure 1. Section 104 also allows for holders of existing oil and gas leases in some parts of the moratorium area to exchange the leases for a bonus or royalty credit to be used in the Gulf of Mexico.21

Section 104 prohibits not only lease sales in the moratorium area, but also "preleasing" and other related activities. BOEM has clarified that such preleasing and related activities are not interpreted to include geological and geophysical (G&G) activities—such as seismic surveys—undertaken to locate resources with the potential to produce commercial quantities of oil and gas.22 BOEM interprets GOMESA to allow these G&G surveys in the moratorium area.23

The moratorium imposed by Section 104 expires on June 30, 2022. The 116th Congress is debating whether to allow the moratorium to expire as scheduled or to amend GOMESA (or enact other legislation) to potentially further restrict federal oil and gas activity in this area. The following sections discuss scenarios for future leasing in the area under current provisions, legislative proposals to provide for other outcomes, and selected issues for Congress related to the moratorium provisions.

Scenario Under Current Statutory Framework

Absent further action by Congress, after June 30, 2022, the executive branch could potentially offer new oil and gas leases in the expired moratorium area. Under the OCSLA, the Secretary of the Interior could decide to include or exclude the area in future five-year offshore oil and gas leasing programs, based on specified criteria.24 The OCSLA also gives the President discretion to withdraw the area, temporarily or indefinitely, from leasing consideration, which would render it unavailable for inclusion in a DOI leasing program.25

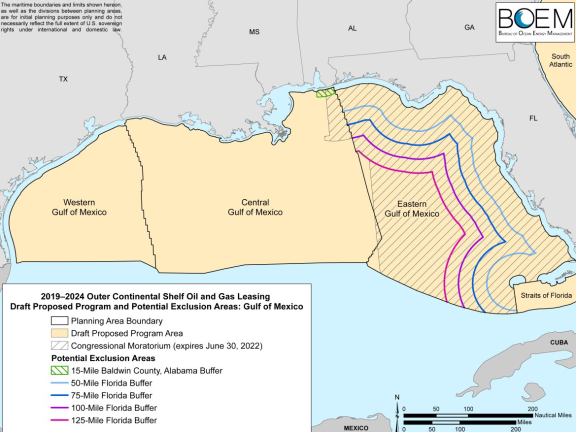

The Trump Administration has indicated interest in pursuing oil and gas leasing in the GOMESA moratorium area after the moratorium's expiration. BOEM's initial draft of a five-year oil and gas leasing program for 2019-2024 (referred to as the "draft proposed program" or DPP) includes two lease sales in the moratorium area, one in 2023 and one in 2024.26 The DPP proposes to offer all available tracts in the former moratorium area after the expiration. BOEM also indicated that it would analyze two secondary options that would exclude some portions of the moratorium area from the lease sales (Figure 2).

|

|

Source: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), "GOMESA Map," at https://www.boem.gov/Areas-Under-Moratoria/. |

|

Figure 2. BOEM's Proposed Eastern Gulf Lease Area and Potential Exclusion Areas, Draft Proposed Program for 2019-2024 |

|

|

Source: BOEM, 2019-2024 National Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing: Draft Proposed Program, January 2018, at https://www.boem.gov/NP-Draft-Proposed-Program-2019-2024/, Figure 4. |

First, BOEM is analyzing a potential "coastal buffer" off Florida—at distances of 50, 75, 100, or 125 miles—to accommodate military activities and nearshore use. Second, BOEM is separately analyzing a potential 15-mile leasing buffer offshore of Baldwin County, AL, to minimize visual and other impacts to onshore coastal areas.27 The next draft of the 2019-2024 program is expected to reflect the results of BOEM's analysis.28 Under the planning process for the program, which is governed by requirements of both the OCSLA and the National Environmental Policy Act, sales listed in the DPP could be retained, modified, or removed in subsequent drafts of the program.29

In deciding whether to include the sales (either in their current form or with modifications) in the final leasing program, the Secretary of the Interior must weigh economic, social, and environmental criteria.30 Among the factors the Secretary must consider under the OCSLA are coastal state governors' views on leasing off their coasts.31 Recent governors of Florida, the state most closely adjacent to the moratorium area, generally have expressed opposition to leasing in this area.32 Governors of other Gulf Coast states—Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas—generally have expressed support for oil and gas leasing in the Eastern Gulf.33

The Secretary also must consider the views of other affected federal agencies.34 One key agency—DOD—historically has opposed new leasing in the area, due to DOD's use of this part of the Gulf as a military testing and training ground (see "Military Readiness"). Both DOD and the Gulf producing states, along with some Members of Congress and many other stake holders, submitted public comments on the 2019-2024 DPP. These comments are to be taken into account in the second draft of the program. Another round of public comment is expected to be solicited before the program could be finalized.

The oil and gas industry has indicated interest in leasing in the moratorium area.35 Some industry representatives have stated that the Eastern Gulf represents a more attractive leasing prospect than other OCS areas currently unavailable for leasing (e.g., the Pacific and Atlantic regions), because data on the Eastern Gulf are better developed than for these other areas and nearby infrastructure is already in place to facilitate exploration and development.36 Industry representatives have expressed particular interest in the deepwater Norphlet play, which spans parts of the Eastern and Central Gulf.37

Legislative Proposals

A number of legislative proposals in the 116th Congress have sought to extend GOMESA's moratorium or to permanently prohibit leasing in the moratorium area. By contrast, other legislation would mandate lease sales in the area directly following the moratorium's current expiration date. Table 2 summarizes provisions of relevant 116th Congress bills.38 Two of these bills, H.R. 4294 and S. 13, include provisions affecting GOMESA revenue sharing, discussed further in Table 5.

|

Bill Number(s) and Statusa |

Law(s) Amended |

Extends Moratorium? |

Length of Extension |

Prohibited Activitiesb |

Portion of Current Moratorium Area Covered |

|

H.R. 205 (Passed House) |

GOMESA |

Yes |

Permanent |

Leasing, preleasing, and related activities |

All |

|

OCSLA |

Yes |

Permanent |

Leasing, preleasing, and related activities |

Eastern Gulfc |

|

|

OCSLA |

Yes |

Through June 30, 2029 |

Leasing, preleasing, and related activities |

Eastern Gulfc |

|

|

OCSLA |

Yes |

Permanent |

Leasing |

Eastern Gulfd |

|

|

GOMESA and OCSLA |

Yes |

Through June 30, 2029 |

Leasing, preleasing, and related activities |

All |

|

|

N/Ae |

No; mandates lease salese |

N/A |

N/A |

All |

|

|

GOMESA |

Yes |

Through June 30, 2027 |

Leasing, preleasing, and related activities |

All |

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Notes: GOMESA = Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (43 U.S.C. §1331 note); OCSLA = Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (43 U.S.C. §§1331-1356b); N/A = not applicable. The table addresses bill provisions that specifically relate to the GOMESA moratorium; some bills contain other provisions, such as provisions to impose leasing moratoria in other parts of the outer continental shelf (H.R. 286, H.R. 291, H.R. 341, H.R. 3585), change offshore revenue-sharing or fee collection arrangements (H.R. 205, H.R. 4294, S. 13), address offshore oil spill response capabilities (H.R. 2352), limit the President's authority to withdraw areas from leasing consideration (H.R. 4294), or make changes related to onshore leasing and renewable energy (H.R. 4294).

a. Bill status is "Introduced" unless otherwise noted.

b. Leasing prohibitions would apply to new leases only; valid existing rights would be retained.

c. The moratorium extension would apply to the "area of the Eastern Gulf of Mexico" described in Section 104(a) of GOMESA. The wording appears to indicate that the moratorium extension would not apply to the small portion of the Central Gulf planning area that is also named in Section 104(a) of GOMESA.

d. The moratorium would apply to the entire Eastern Gulf of Mexico planning area. This would appear to include the small portion of the Eastern Gulf planning area that is not under moratorium currently under GOMESA, but to exclude the small portion of the Central Gulf planning area that currently is covered by the GOMESA moratorium.

e. Section 205(b) of H.R. 4294 would direct that lease sales be held in the GOMESA moratorium area at least once in the six months following expiration and at least twice a year thereafter (whether or not such lease sales are included in DOI's five-year leasing program). This subsection of the bill would not amend existing statutes. Other bill provisions, not directly related to the moratorium, amend both GOMESA and OCSLA.

One proposal related to the moratorium has passed the House of Representatives in the 116th Congress: H.R. 205, the Protecting and Securing Florida's Coastline Act of 2019. The bill would amend GOMESA to extend the Eastern Gulf moratorium indefinitely, thus precluding future oil and gas leasing in the area. In its report on the bill, the House Natural Resources Committee stated that a continued moratorium is necessary because leasing in the Eastern Gulf would compromise military readiness and "pose existential threats to Florida's tourism, fishing, and recreation economy, which rely on clean water and healthy beaches."39 In dissenting views, some committee members contended that oil and gas leasing in the area could successfully coexist with fishing, tourism, and military operations, and pointed to the role of Gulf oil and gas revenues in funding environmental restoration activities and land protection.40

Bills in earlier Congresses had sought other types of outcomes related to the GOMESA moratorium. For example, some legislation would have enabled leasing in portions of the moratorium area before the 2022 expiration date, effectively shrinking the moratorium area.41 Other legislation would have prohibited some activities in the moratorium area that are not currently restricted by GOMESA, such as seismic surveys or research on potential areas for offshore drilling.42 These proposals have not been included to date in 116th Congress legislation.

Selected Issues

Economic and Budgetary Considerations

An extension of GOMESA's leasing prohibitions could result in a loss to the government of future federal revenues (to the extent that leasing and commercial production would otherwise take place when the moratorium expires). Also, some oil and gas industry advocates have contended that future development in the Eastern Gulf could contribute billions of dollars annually to the nation's gross domestic product, mainly through contributions to Gulf state economies, which they contend would be lost were the moratorium to continue.43 By contrast, some in the commercial fishing, tourism, and recreation sectors have focused on potential economic costs to these sectors if oil and gas development takes place off the coast of Florida, with particular emphasis on potential financial losses if a major oil spill were to occur. They point to estimates showing significant costs to these industries from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.44 Other stakeholders express concern that any oil and gas activities in these areas would contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and human-induced climate change, with accompanying direct and indirect costs.45

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated certain budgetary effects of a moratorium extension in relation to budget projections under existing law. CBO has estimated that bills to extend the moratorium would reduce offsetting receipts and thus increase direct federal spending.46 As a result, such bills may be subject to certain budget points of order unless offset or waived.47 For example, for the version of H.R. 205 reported by the House Committee on Natural Resources, CBO estimated that the bill's extension of GOMESA's moratorium would increase direct spending by $400 million over 10 years.48

Military Readiness

The extent to which the GOMESA moratorium is needed for U.S. military readiness also has been at issue. The area east of the Military Mission Line in the Eastern Gulf provides about 101,000 square miles of surface area and overlying air space, which is the largest overwater DOD test and training area in the continental United States.49 DOD historically has expressed a need for an oil and gas leasing moratorium in this area. For instance, in 2006, DOD stated that its testing and training activities in the Eastern Gulf were "intensifying" and required "large, cleared safety footprints free of any structures on or near the water surface."50 In 2017, DOD wrote that the agency "cannot overstate the vital importance of maintaining this moratorium.... Emerging technologies such as hypersonics, autonomous systems, and advanced sub-surface systems will require enlarged testing and training footprints, and increased DoD reliance on the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act's moratorium beyond 2022."51 More recently, in a 2018 report to Congress on preserving military readiness in the Eastern Gulf, DOD wrote:

No other area in the world provides the U.S. military with ready access to a highly instrumented, network-connected, surrogate environment for military operations in the Northern Arabian Gulf and Indo-Pacific Theater. If oil and gas development were to extend east over the [Military Mission Line], without sufficient surface limiting stipulations and/or oil and gas activity restrictions mutually agreed by the DoD and Department of Interior (DoI), military flexibility in the region would be lost and test activities severely affected.52

Some Members of Congress and other stakeholders have interpreted the wording of the 2018 report—particularly its phrase "without sufficient surface limiting stipulations and/or oil and gas activity restrictions"—as signaling a greater DOD openness to oil and gas activities in the moratorium area than had been expressed in some earlier DOD communications.53 The phrasing might be read to suggest that military readiness and oil and gas development could be mutually accommodated, given appropriate stipulations and restrictions. Oil and gas leases awarded in the Central and Western Gulf often contain stipulations related to military activities, such as those requiring the lessee to assume risks of damage from military activities, to control electromagnetic emissions in defense warning areas, to consult with military commanders before entering some areas, and/or to evacuate areas as needed for military purposes.54 BOEM also typically reserves the right to temporarily suspend a lease in the interest of national security.

The 2018 report does not clarify what types of lease stipulations and restrictions might be necessary to accommodate the more intensive testing and training activities in the Eastern Gulf. The report states that some military activities in this area may be incompatible with the presence of fixed or mobile oil platforms.55 The report expresses concerns that increased vessel traffic and underwater noise could jeopardize some military activities.56 It also discusses concerns about potential foreign observation of DOD activities, if foreign entities are allowed to control offshore assets or otherwise conduct business near military ranges in the Eastern Gulf.57 If these military concerns were to lead to more stringent restrictions on oil and gas operations than are mandated in other parts of the Gulf, a question would be how such restrictions might affect industry interest in bidding on leases in the Eastern Gulf. In its cost estimate for H.R. 205, CBO identified defense-related constraints (and the potential incompatibility of some development with Florida's Coastal Management Program) as factors that could reduce the value of Eastern Gulf leases to industry bidders.58 However, some industry representatives have expressed consistent interest in leasing in the area and have contended that economic returns on leases in this area would be substantial, despite potential restrictions related to military activities.59

Section 105: Revenue Sharing

Section 105 of GOMESA provides for federal revenues from certain qualified leases in the Gulf of Mexico to be shared under specified terms with four Gulf producing states—Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas—and their "coastal political subdivisions" or CPSs (e.g., coastal counties or parishes), as well as with the LWCF state assistance program.60 Specifically, each year the Secretary of the Treasury is to deposit 50% of qualified revenues in a special account (the remaining 50% are deposited in the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury as miscellaneous receipts). From this special account, the Secretary disburses 75% of funds to the Gulf states and their CPSs, and 25% to the LWCF state assistance program.61 Accordingly, of the total qualified revenues in a given year, the states and their CPSs receive 37.5% (i.e., 75% of the 50% in the special account), while the LWCF receives 12.5% (i.e., 25% of the 50%).

The law's definition of "qualified" OCS revenues differs for the first decade after GOMESA's enactment (FY2007-FY2016) versus for subsequent years. For FY2007-FY2016 (often referred to as GOMESA's Phase I), the law defines qualified OCS revenues to include all bonus bids, rents, royalties, and other sums due and payable to the United States from leases in the Eastern Gulf and the Central Gulf's 181 South Area entered into on or after the date of GOMESA's 2006 enactment.62 These are the relatively small areas shown as areas A and B in Figure 1. For FY2017 and beyond (Phase II), the geographic area of qualified revenues expands. In addition to revenues from post-2006 leases in the Phase I areas, the qualified revenues in Phase II include those from post-2006 leases in the Central Gulf's portion of the 181 Area, shown as area C in Figure 1. The Phase II qualified revenues also include the "2002-2007 planning area"—the large area shown in yellow in Figure 1, encompassing most of the Western and Central Gulf, where the bulk of production takes place.63 Accordingly, revenues qualified for sharing in Phase II are likely to be notably higher than in Phase I (Table 3).

For the added Phase II areas, Section 105 stipulates that the total amount of qualified revenues made available each year to the states and their CPSs and the LWCF (collectively) shall not exceed $500 million for each of FY2016-FY2055.64 A later law, P.L. 115-97, raised the cap to $650 million for two of these years, FY2020 and FY2021.65 Given the percentage distributions specified in the law for each recipient, the amounts that can be shared with states and their CPSs from the added Phase II areas are capped at $375.0 million in most years (and $487.5 million in FY2020 and FY2021). The amounts that can be shared with the LWCF are capped at $125.0 million in most years (and $162.5 million in FY2020 and FY2021).

Phase II began with FY2017 revenues, but GOMESA specifies that revenues shall be shared with recipients in the fiscal year immediately following the fiscal year in which they are received.66 Thus, in terms of payments, the first fiscal year reflecting Phase II revenue sharing was FY2018. The shared revenues rose notably in that year compared with previous years. Table 3 shows GOMESA revenue distributions since the law's enactment, with the transition from Phase I distributions to Phase II distributions occurring between FY2017 and FY2018.

|

Year of Distributiona |

Alabamab |

Louisianab |

Mississippib |

Texasb |

Total State Revenue |

LWCF State Programc |

Total Revenue Shared |

||||||||||||||

|

FY2009d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

FY2019 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR), "Natural Resources Revenue Data: Data Query Tool," at https://revenuedata.doi.gov/query-data/?dataType=Disbursements; and National Park Service budget justifications for FY2011-FY2020, available at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/budget.htm.

Notes: CPSs = coastal political subdivisions; LWCF = Land and Water Conservation Fund. Phase II of GOMESA began in FY2017, but the Phase II revenues are first reflected in FY2018 payments. See footnote 66 for additional information. The figures reflect budget sequestration. Totals may not sum precisely due to rounding. Dollar amounts are nominal (not adjusted for inflation).

a. Under GOMESA Section 105(c), revenues are distributed to the states and LWCF in the fiscal year immediately following that in which they are deposited in the revenue-sharing account.

b. Revenue distributions for each state include distributions to the coastal political subdivisions (CPSs) of each state.

c. Amounts correspond with the year that revenues were shown in the NPS budget. (The revenues are reflected in ONRR records for the previous year—the year of receipt.)

d. GOMESA was enacted on December 20, 2006. Revenues from qualified leases were first deposited in the revenue-sharing account in FY2008, and were first shared with recipients in FY2009.

GOMESA directs the Secretary of the Interior to establish a formula to allocate each year's qualified state revenues among the four Gulf producing states and their CPSs.67 The allocations to each state primarily depend on its distance from leased tracts, with states closer to the leased tracts receiving a higher share.68 The law additionally provides that each state must receive an annual minimum of at least 10% of the total amount available to all the Gulf producing states for that year.69 Further, GOMESA directs that the Secretary shall pay 20% of the allocable share of each Gulf producing state to the state's CPSs.70 See the box below for additional details on the state allocations.

|

GOMESA's State Revenue Allocation Formula: Additional Details The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (ONRR) have established a formula for allocating revenues to the four Gulf producing states—Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas—under the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act (GOMESA; 43 U.S.C. §1331 note). Drawing on regulations from 2008 that established a formula for allocating revenues from the Phase I areas, BOEM and ONRR revised the formula to reflect Phase II in 2015. The revised formula applies similarly but not identically to the Phase I and Phase II areas (see Figure 1 for a map of these areas). For Phase I areas, the allocations are based on a calculation of each state's proportional inverse distance from the applicable leased tracts for a given year. For Phase II areas, in addition to leased tracts for the year, distance from a defined set of "historical lease sites" also is taken into account (and the revenue cap is applied).71 In both cases, the result of the inverse distance calculation is that states closest to the most tracts receive the greatest share of revenues. More specifically, DOI makes the following calculations to determine each state's revenue share: Determine the mathematical inverse of the distance between the geographic center of each applicable leased tract (and, for Phase II areas, each historical lease site) and the point on each state's coastline that is closest to that geographic center. Divide the sum of each state's inverse distances from all applicable leased tracts and (for Phase II areas) historical lease sites by the sum of the inverse distances from all applicable leased tracts and (for Phase II areas) historical lease sites across all four Gulf producing states. Multiply the result by the amount of qualified outer continental shelf revenues to be shared. Additional parameters also may apply. For instance, if the amount of qualified state-sharing revenues (37.5% of total qualified revenues) from the Phase II areas exceeds $375.0 million (or $487.5 million in FY2020 and FY2021), then the revenue-sharing cap would be invoked, and only the capped amount from the Phase II areas (along with any revenues from the Phase I areas) would be subject to the sharing formula. Also, if application of the sharing formula resulted in any state receiving less than the 10% minimum requirement, the allocations would be adjusted so that state received 10%, with the remainder divided among the other three states according to the formula. Within a state, the formula for allocation among the coastal political subdivisions is based on their relative population, coastline length, and proportional inverse distance from applicable leased tracts (and, for Phase II areas, historical lease sites). Sources: Minerals Management Service, "Allocation and Disbursement of Royalties, Rentals, and Bonuses—Oil and Gas, Offshore," 73 Federal Register 78622, December 23, 2008; BOEM and ONRR, "Allocation and Disbursement of Royalties, Rentals, and Bonuses—Oil and Gas, Offshore," 80 Federal Register 81454, December 30, 2015. |

GOMESA authorizes the states and CPSs to use revenues for the following purposes:72

- Projects and activities for the purposes of coastal protection, including conservation, coastal restoration, hurricane protection, and infrastructure directly affected by coastal wetland losses.

- Mitigation of damage to fish, wildlife, or natural resources.

- Implementation of a federally approved marine, coastal, or comprehensive conservation management plan.

- Mitigation of the impact of OCS activities through the funding of onshore infrastructure projects.

- Planning assistance and the administrative costs of complying with GOMESA. (No more than 3% of a state or CPS's revenues may be used for this purpose.)

The following sections discuss the scenario for GOMESA revenue sharing under the law's current provisions, summarize legislative proposals for changes, and explore selected issues.

Scenario Under Current Statutory Framework

Under GOMESA, revenue sharing with the states and LWCF continues indefinitely, and the annual cap on shared revenues from the Phase II areas continues through FY2055.73 After that year, all qualified Gulf revenues would be shared under the current formula—37.5% to states and their CPSs and 12.5% to the LWCF—regardless of whether the shared amount from the Phase II areas exceeds $500 million.

DOI, in its annual budget justifications, develops five-year projections of qualified GOMESA revenues. Table 4 shows DOI projections for FY2020-FY2024 shared revenues (which are half of all qualified revenues), by revenue collection year. The revenues collected in a given year would be shared with the states and LWCF in the following fiscal year.

Table 4. DOI Projections of GOMESA Shareable Revenues, FY2020-FY2024, by Year of Revenue Collection

($ in millions)

|

Recipient |

FY2020 Estimate |

FY2021 Estimate |

FY2022 Estimate |

FY2023 Estimate |

FY2024 Estimate |

|

States/CPSs |

353.4 |

349.7 |

342.0 |

361.9 |

375.1a |

|

LWCF |

117.8 |

116.6 |

114.0 |

120.6 |

125.0a |

|

Total |

471.2 |

466.2 |

456.0 |

482.5 |

500.1a |

Source: Congressional Research Service calculations from DOI, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2020: Office of the Secretary, Department-Wide Programs, Table 6, p. MLR-15, available at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2020_os_budget_justification.pdf.

Notes: CPSs = coastal political subdivisions; LWCF = Land and Water Conservation Fund. Totals may not sum precisely due to rounding. Dollar amounts are nominal (not adjusted for inflation). The table shows shareable revenues projected to be received (i.e., collected) in each fiscal year. Under GOMESA, revenues received in a given fiscal year are shared with the states and the LWCF in the following fiscal year.

a. DOI projects that for FY2024, shareable revenues (which are half of all qualified revenues) would total $500.1 million. DOI does not break down what portion of this revenue-sharing total is projected to come from the Phase II areas, which are subject to a revenue-sharing cap of $500.0 million.

DOI projects that the shareable revenues will remain under $500 million for each year from FY2020 to FY2023, meaning that neither the $650 million cap for FY2020 and for FY2021 nor the $500 million cap for FY2022 and for FY2023 is projected to be invoked. For FY2024, DOI shows the shareable revenues slightly exceeding $500 million, but it is unclear whether the cap is projected to be invoked—the cap applies only to revenues from the Phase II areas, and DOI does not break down the portion of revenue sharing projected to come from the Phase II areas. In general, the DOI projections for a given year have not always been consistent over time. Changing oil prices have been a major factor in revised projections.

Under the current scenario, the majority of the moratorium area—the portion shown in gray in Figure 1—does not qualify for revenue sharing, even after the moratorium ends in June 2022.74 Instead, any revenues from oil and gas leasing and development in this area after the moratorium expires would go entirely to the Treasury.75 Also, GOMESA does not provide for revenue sharing with Florida, although some of the qualified revenue-sharing areas—such as portions of the 181 Area—are closer to Florida than to the other Gulf producing states.

Legislative Proposals

In the 116th Congress, several bills would amend GOMESA to increase the portion of qualified revenues shared with the Gulf producing states by raising the states' percentage share, eliminating the revenue-sharing cap, or both. Some legislation also would expand the purposes for which states may use the GOMESA revenues, modify the uses of the LWCF share, or add Florida to the revenue-sharing arrangement. Table 5 describes selected relevant bills and their provisions. None of the bills has been reported from committee in the 116th Congress.

|

Bill Number |

Law Amendeda |

Changes 37.5% State Share? |

Changes 12.5% LWCF Share? |

Eliminates Cap? |

Other GOMESA Revenue-Sharing Changes |

|

GOMESA |

Raises to 50% |

No |

Yes |

Expands uses of state shareb |

|

|

GOMESA |

Raises to 50% |

No |

Yes |

— |

|

|

GOMESA |

No |

No |

No |

Adds Florida as a state receiving shared revenues |

|

|

GOMESA |

No |

New use for LWCF sharec |

No |

— |

|

|

GOMESA |

Raises to 50% |

No |

Yes (after FY2019) |

Expands revenues qualified for sharingd |

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Notes: LWCF = Land and Water Conservation Fund. Status of all bills is "Introduced." The table addresses bill provisions that specifically relate to GOMESA revenue sharing; some bills also contain other provisions, such as provisions to change revenue sharing in other parts of the outer continental shelf (OCS) (H.R. 4294, S. 2418), extend the GOMESA moratorium (S. 13), mandate certain offshore lease sales (H.R. 4294), limit the President's authority to withdraw areas from leasing consideration (H.R. 4294), make changes related to onshore leasing and renewable energy (H.R. 4294), or establish new federal assistance programs (S. 1458).

a. Applies to bill provisions specifically related to GOMESA revenue sharing. Some bills also contain provisions related to other matters (see general note above), which may amend multiple laws.

b. H.R. 3814 and S. 2418 would expand the uses of the state share to include "planning, engineering, design, construction, operations, and maintenance of one or more projects that are specifically authorized by any other Act for ecosystem restoration, hurricane protection, or flood damage prevention." Under H.R. 3814, states and their coastal political subdivisions would be required to use at least 25% of revenues for this purpose, with the revenues to be applied to both the federal and nonfederal shares of qualified projects. S. 2418 does not contain this minimum usage requirement.

c. S. 1458 would amend GOMESA to require that, for each of FY2020 through FY2055, 20% of the LWCF share of GOMESA revenues be used to provide competitive matching grants to eligible public and tribal entities to acquire land and water for parks and outdoor recreation, or to develop or renovate outdoor recreation facilities.

d. For FY2020 and beyond, S. 2418 would expand GOMESA's definition of qualified OCS revenues to include those from leases entered into on or after October 1, 2000, rather than only leases entered into since GOMESA's 2006 enactment.

In contrast with bills that would increase the state revenue share, some legislative proposals in earlier Congresses would have ended state revenue sharing under GOMESA. For example, in the 114th Congress, would have amended GOMESA to provide that 87.5% of qualified revenues under the law would be deposited in the Treasury's General Fund, while 12.5% would continue to be provided for LWCF financial assistance to states. This proposal is similar to some legislative proposals in DOI budget requests under the Obama and Trump Administrations (see "Determining the Appropriate State Share").

Selected Issues

Determining the Appropriate State Share

Members of Congress differ in their views on the extent to which Gulf Coast states should share in revenues derived from oil and gas leasing in federal areas of the Gulf. State officials from the Gulf producing states and some Members of Congress have expressed that the Gulf producing states should receive a higher share than is currently provided under GOMESA, given the costs they incur to support offshore extraction activities. These stakeholders have argued that the revenues are needed to mitigate environmental impacts and to maintain the necessary support structure for the offshore oil and gas industry. For example, at a 2018 hearing of the House Committee on Natural Resources, former Senator Mary Landrieu stated: "It is important to note that revenue sharing was established … to recognize the contributions that states and localities make to facilitate the extraction and production of these resources, including the provision of infrastructure to enable the federal activity: transportation, hospitals, schools and other necessary governmental services."76 Advocates have emphasized that Gulf Coast areas, especially coastal wetlands, face significant environmental challenges, owing in part to hydrocarbon development (among other activities).77 These advocates have contended that additional federal revenues are critical to address environmental challenges and economic impacts of wetland loss. Advocates point to a disparity between the 37.5% state share provided under GOMESA and the 50% share of revenues that most states receive from onshore public domain leases under the Mineral Leasing Act.78 They contend that a comparable state revenue share under GOMESA would significantly contribute to coastal wetland restoration, given GOMESA's requirement that the Gulf producing states use the funding to address coastal protection, damage mitigation, and restoration (and given comparable requirements under some state law).79

By contrast, some other Members of Congress, as well as the Obama and Trump Administrations at times, have contended that GOMESA revenue sharing with the states should be reduced or eliminated to facilitate use of these revenues for broader national purposes. They have argued that, since the OCS is a federal resource, the benefits from offshore revenues should accrue to the nation as a whole, rather than to specific coastal states. Under the Obama Administration, DOI budget requests for FY2016 and FY2017 recommended that Congress repeal GOMESA state revenue-sharing payments and direct a portion of the savings to programs that provide "broad … benefits to the Nation," such as a proposed new Coastal Climate Resilience Program "to provide resources for at-risk coastal States, local governments, and their communities to prepare for and adapt to climate change."80 Legislation in the 114th Congress (S. 2089; see "Legislative Proposals") would have amended GOMESA to eliminate the state revenue sharing and provide for the state share to go to the Treasury's General Fund. For FY2018, the Trump Administration proposed that Congress repeal GOMESA's state revenue-sharing provisions, in order to "ensure [that] the sale of public resources from Federal waters owned by all Americans, benefit all Americans."81 The Trump Administration has not included similar proposals in subsequent budget requests, and no legislation to reduce or eliminate GOMESA state revenue sharing has been introduced to date in the 116th Congress.

Set of Leases Qualified for Revenue Sharing

Although Phase II of GOMESA considerably expanded the set of leases contributing to revenue sharing, some Gulf leases still do not qualify, because the law applies only to leases that were entered into on or after the date of GOMESA's enactment (December 20, 2006). It appears from 2019 leasing data maintained by BOEM that approximately 61% of the more than 2,500 active leases in the Gulf of Mexico were entered into on or after the enactment date, and thus would qualify for revenue sharing under GOMESA's current terms.82 However, the majority of these newer leases are not producing oil and gas; and leases awarded before GOMESA's enactment—which do not qualify—continue to contribute a substantial portion of production royalties.83 For this reason, the percentage of Gulf revenues subject to GOMESA sharing is much smaller than the percentage of Gulf leases subject to GOMESA sharing. For example, of federal offshore revenues disbursed in FY2019 (the high majority of which come from the Gulf), GOMESA-qualified revenues—including those distributed to states and their CPSs, the LWCF state grant program, and the Treasury combined—constituted 18% of the total.84 The percentage of total revenues that qualify for sharing under GOMESA might be expected to increase over time, to the extent that older leases gradually terminate and current and future leases begin producing.85

Some Members of Congress have proposed that GOMESA's terms be altered to include an expanded set of leases in the qualified sharing group. For instance, in the 116th Congress, S. 2418 would amend GOMESA to define the qualified leases as those entered into on or after October 1, 2000, rather than after GOMESA's 2006 enactment. According to BOEM data as of November 2019, this would more than double the number of producing leases eligible for GOMESA revenue sharing (although the addition in total leases would be relatively small).86 The result could be a higher revenue share with the states and their CPSs and the LWCF state grant program.87 Some other Members do not favor this type of change because it could reduce the portion of offshore revenues going to the Treasury for other federal purposes.88

Revenue Amounts and Adequacy for Legislative Purposes

Offshore oil and gas revenues support a variety of federal and state activities, through amounts deposited annually in the LWCF and the Historic Preservation Fund (HPF) and through revenues shared with states under revenue-sharing laws.89 Revenue totals have fluctuated from year to year (Table 1), raising questions about whether future revenues will be adequate to support these various activities and whether new legislation for offshore revenue distribution would strain available amounts.90 For example, some Members of Congress have considered whether raising GOMESA's state revenue share would result in insufficient funds to meet statutory requirements for deposits to the LWCF and HPF. Alternatively, some Members have questioned whether proposals to use offshore revenues for new conservation programs would reduce state sharing under GOMESA and jeopardize programs supported by the state-shared funds.91

Thus far, in each year since GOMESA's enactment, OCS revenues have been sufficient to provide for all distributions under current law. If bills in Table 5 were enacted to raise the GOMESA state revenue share to 50% and eliminate the revenue-sharing cap for states, it appears that, based on DOI projections for FY2020-FY2024, OCS revenues remaining after state sharing would still be more than sufficient to meet statutory requirements for deposits to the LWCF and HPF in these years.92 Various economic factors or policy decisions could affect these DOI projections, and under some theoretical scenarios, enactment of bills to increase the state share could affect the sufficiency of revenues to cover other legislative requirements.

Similarly, under some scenarios, legislative proposals to fund new conservation programs with offshore revenues could affect amounts shared with the states under GOMESA. Whether this would occur would depend partly on the terms of the legislative proposals. For example, S. 500 and H.R. 1225 in the 116th Congress would establish a new deferred maintenance fund for specified federal lands supported partly by offshore energy revenues.93 These proposals address the issue of revenue availability by specifying that the new deferred maintenance fund would draw only from miscellaneous receipts deposited to the Treasury after other dispositions are made under federal law.94 That is, if revenues were insufficient to provide for the funding amounts specified under these bills along with the other distributions required in law, it appears that the requirements of current laws (including GOMESA) would be prioritized.

Also relevant are proposals by some Members of Congress and other stakeholders to significantly curtail or end OCS oil and gas leasing, in response to climate change concerns.95 Depending on the extent to which offshore production decreased, such policy changes could result in an insufficiency of revenues to meet all statutory requirements, especially over the long term as production from existing leases diminished.96 Some supporters of reducing or eliminating federal offshore oil and gas leasing have suggested that other revenue sources, such as from an expansion of renewable energy leasing on federal lands, should be found for desired federal programs. Some opponents of curtailing offshore oil and gas leasing have pointed to the revenue implications as an argument against such actions.

Budgetary Considerations

Bills that would increase the state share of GOMESA revenues—by giving the states a higher revenue percentage, eliminating revenue-sharing caps, or both—have been identified by CBO as increasing direct spending.97 For example, in cost estimates for 115th Congress legislation—which would have made similar state-sharing changes to those proposed in H.R. 3814, H.R. 4294, and S. 2418 (Table 5)—CBO estimated that these changes would increase direct spending of OCS receipts by $2.1 billion over a 10-year period.98 As a result, such legislation may be subject to certain budget points of order unless offset or waived.99 As of January 2020, CBO has not released cost estimates for the 116th Congress bills discussed in Table 5 (none of which has been reported from committee), and it is unclear how CBO would estimate costs associated with those bills or whether some provisions in those bills might be estimated to offset costs of other provisions. For example, H.R. 4294 contains provisions to repeal presidential withdrawals of offshore areas from leasing consideration and to facilitate offshore wind leasing in U.S. territories, among others. CBO scored similar provisions in 115th Congress bills as increasing offsetting receipts (and thus partly offsetting bill costs).100

Florida and Revenue Sharing

Under GOMESA's current provisions, Florida is not among the Gulf producing states eligible for revenue sharing. Some proposals, including S. 13 in the 116th Congress, would add Florida to the group of states receiving a revenue share.101 Because the high majority of Gulf leasing takes place in the Western and Central Gulf planning areas, which do not abut Florida, Florida's share of GOMESA revenues if S. 13 were enacted would likely be lower than those of the other Gulf Coast states, especially Louisiana and Texas.102 Nonetheless, since GOMESA provides that every Gulf producing state must receive at least 10% of the annual state revenue share, adding Florida to the Gulf producing states would provide at least that portion of GOMESA revenues for Florida and would correspondingly reduce the total available to the other Gulf producing states.

Some Florida stakeholders have opposed legislation to add Florida to GOMESA revenue sharing, on the basis that doing so could incentivize eventual oil and gas development off Florida.103 Others support a continued moratorium off Florida and also support giving Florida a revenue share from leasing elsewhere in the Gulf. These stakeholders contend that Florida bears risks from oil and gas leasing elsewhere in the Gulf (particularly related to potential oil spills) and so should also see benefits.104 This position is captured in S. 13, which would extend the GOMESA moratorium through 2027 and add Florida as a revenue-sharing state. Still others support adding Florida as a revenue-sharing state as part of a broader change to allow leasing and revenue sharing in areas offshore of Florida. Supporters of this approach, including some from the current Gulf producing states, may contend that an increase in the number of states that share GOMESA revenues should be accompanied by a growth in the area qualified for revenue sharing, to reduce the likelihood of a smaller share for the original four states.

Conclusion

The current period is one of transition for the oil and gas leasing framework established by GOMESA for the Gulf of Mexico. First, the Eastern Gulf leasing moratorium is set to expire in 2022, and BOEM is proposing offshore lease sales for the moratorium area starting in 2023. Second, the Gulf leases subject to revenue sharing expanded substantially starting in FY2017, and DOI projects that revenues from these areas will approach or reach GOMESA's revenue-sharing cap in FY2024. Congress is considering whether GOMESA's current provisions will best meet federal priorities going forward, or whether changes are needed to achieve various (and sometimes conflicting) national goals.

Regarding the moratorium provisions, a key question is whether decisions about leasing in the Eastern Gulf should be legislatively mandated or left to the executive branch to control. Absent any legislative intervention, after June 2022, the President and the Secretary of the Interior are to decide whether, where, and under what terms to lease tracts in the former moratorium area, following the statutory provisions of the OCSLA. Some Members of Congress seek to amend GOMESA—either to extend the moratorium or to mandate lease sales in the area—rather than deferring to the OCSLA's authorities for executive branch decisionmaking. At stake are questions of regional and national economic priorities, environmental priorities, energy security, and military security.

With respect to Gulf oil and gas revenues, GOMESA's current revenue-sharing provisions take into account multiple priorities: mitigating the impacts of human activities and natural processes on the Gulf Coast (through state revenue shares directed to this purpose); supporting conservation and outdoor recreation nationwide (through the LWCF state assistance program); and contributing to the Treasury. For the most part, legislative proposals to change the terms of GOMESA revenue distribution have supported some or all of these priorities but have sought to change the balance of revenues devoted to each purpose. Also at issue are proposals to use the revenues for new (typically conservation-related) purposes outside the GOMESA framework, as well as proposals to substantially reduce or eliminate Gulf oil and gas production—with corresponding revenue implications—in the context of addressing climate change. The 116th Congress is debating such questions as it considers multiple measures to amend GOMESA.