Overview

After more than 16 years of confronting conflict, violence, and zero-sum political competition, Iraqis are struggling to redefine their country's future and are reconsidering their relationships with the United States, Iran, and other third parties. Since seeking international military assistance in 2014 to regain territory seized by the Islamic State organization (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL), Iraqi leaders have implored international actors to avoid using Iraq as a battleground for outsiders' rivalries and have attempted to build positive, non-exclusive ties to their neighbors and to global powers. Nevertheless, Iraq has become a venue for competition and conflict between the United States and Iran, with resulting violence now raising basic questions about the future of the U.S.-Iraqi partnership and regional security. Durable answers to these questions may depend on the outcome of fluid political developments in Iraq, where mass protests forced the resignation of the government in late 2019, but transition arrangements and electoral plans have yet to be decided.

Protests, Conflict, and Crisis Developments in Iraq, October 2019-January 2020

|

October 2019

|

Mass protests erupt across central and southern Iraq. Protestors demand reform, service improvements, and the resignation of Prime Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi and his cabinet. Some media outlets are shuttered and nearly 150 protestors are killed and hundreds more injured by security forces and gunmen. The prime minister rejects calls for his resignation, citing fears that a political vacuum will result, and instead proposes administrative reforms and state hiring initiatives. Protestors resume demonstrations on October 25, insisting on fundamental change and reiterating calls for the government's resignation. Protestors burn an Iranian consulate and destroy political party headquarters and provincial government buildings in southern Iraq. Security forces and Iran-backed militia personnel kill dozens of protestors, wounding hundreds more. Iraqi President Barham Salih states that the prime minister is conditionally willing to resign.

|

|

November 2019

|

Confrontations between protestors and security forces multiply and intensify, with at least 400 protestors dead by month's end and thousands more wounded. Protestors temporarily halt operations at the country's main port and burn the Iranian consular facility in Najaf, Iraq. President Salih proposes changes to Iraq's electoral system, and Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi announces his intent to resign.

|

|

December 2019

|

The Council of Representatives (COR) acknowledges the prime minister's resignation and negotiations begin to find a replacement candidate acceptable to major political forces and protestors. The COR adopts new laws governing Iraq's electoral system. President Barham Salih states his willingness to resign after declining to designate as prime minister a candidate proposed by the Bin'a bloc. After a rocket attack kills one U.S. contractor and wounds others near Kirkuk, U.S. forces strike facilities and personnel associated with the Iran-backed Kata'ib Hezbollah (KH) militia, operating as part of the state-affiliated Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). Iraq's government protests the U.S. strike as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty. KH and PMF supporters march on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, setting fire to structures and vandalizing property.

|

|

January 2019

|

On January 2, 2020 (EST), U.S. military forces conduct an airstrike near Baghdad killing Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani, head of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Qods Force (IRGC-QF). The strike kills Kata'ib Hezbollah founder and Iraqi PMF official Abu Mahdi al Mohandes, along with other IRGC-QF and Iraqi PMF personnel. Iraq's government vehemently protests, and Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi calls for and then addresses a special COR session, recommending that legislators direct the government to end foreign military operations in Iraq. After a quorum of COR members unanimously support such a directive to the government, Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi informs U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Matthew Tueller that Iraq's government seeks to work with the United States to jointly implement the decision.

|

|

Iraq: Select History and Background

Iraqis have persevered through intermittent wars, internal conflicts, sanctions, displacements, unrest, and terrorism for decades. A 2003 U.S.-led invasion ousted the dictatorial government of Saddam Hussein and ended the decades-long rule of the Baath Party. This created an opportunity for Iraq to establish new democratic, federal political institutions and reconstitute its security forces. It also ushered in a period of chaos, violence, and political transition from which the country is still emerging. Latent tensions among Iraqis that were suppressed and manipulated under the Baath regime were amplified in the wake of its collapse. Political parties, ethnic groups, and religious communities competed with rivals and among themselves for influence in the post-2003 order, amid sectarian violence, insurgency, and terrorism. Misrule, foreign interference, and corruption also took a heavy toll on Iraqi society during this period, and continue to undermine public trust and social cohesion.

In 2011, when the United States completed an agreed military withdrawal, Iraq's gains proved fragile. Security conditions deteriorated from 2012 through 2014, as the insurgent terrorists of the Islamic State organization (IS, also called ISIS/ISIL)—the successor to Al Qaeda-linked groups active during the post-2003 transition—drew strength from conflict in neighboring Syria and seized large areas of northern and western Iraq. From 2014 through 2017, war against the Islamic State dominated events in Iraq, and many pressing social, economic, and governance challenges remain to be addressed (See Table 1 for a statistical profile of Iraq). Iraqi security forces and their foreign partners wrested control of northern and western Iraq back from the Islamic State, but the group's remnants remain dangerous and Iraqi politics have grown increasingly fraught.

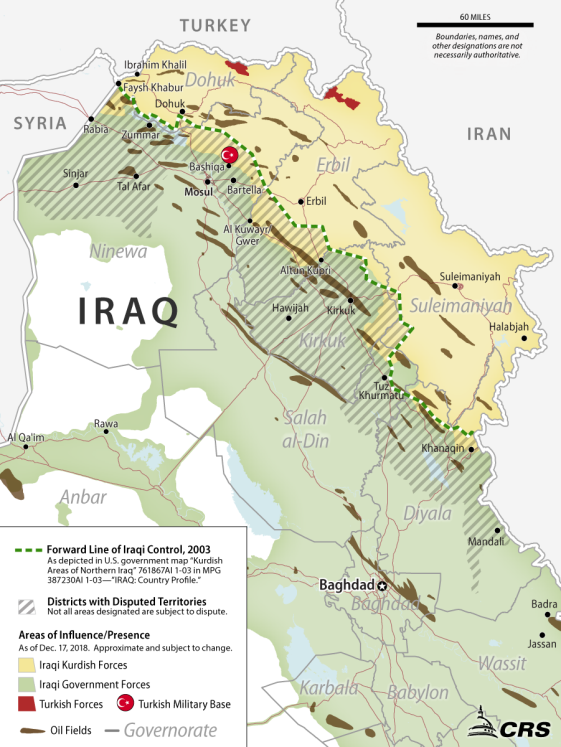

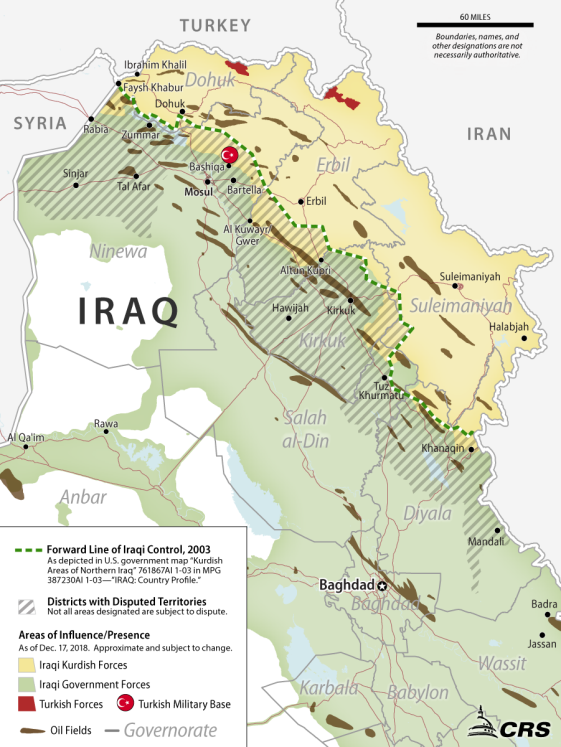

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) maintains considerable administrative autonomy under Iraq's 2005 constitution, and held a controversial advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017. From mid-2014 through October 2017, Kurdish forces took control of many areas that had been subject to territorial disputes with national authorities prior to the Islamic State's 2014 advance, including much of the oil-rich governorate of Kirkuk. However, in October 2017, Iraqi government forces moved to reassert security control in many of these areas, leading to some armed confrontations and casualties on both sides and setting back some Kurds' aspirations for independence (Figure 6).

Across Iraq, including in the KRI, long-standing popular demands for improved service delivery, security, and effective, honest governance remain widespread. Opposition to uninvited foreign political and security interference is also broadly shared. Stabilization and reconstruction needs in areas liberated from the Islamic State are extensive. Paramilitary forces mobilized to fight IS terrorists have grown stronger and more numerous since the Islamic State's rapid advance in 2014, but have yet to be fully integrated into national security institutions. Iraqis are grappling with these political and security issues in an environment shaped by ethnic, religious, regional, and tribal identities, partisan and ideological differences, personal rivalries, economic disparities, and natural resource imbalances. Iraq's neighbors and other international powers are actively pursuing their diplomatic, economic, and security interests in the country. Iraq's strategic location, its potential, and its diverse population with ties to neighboring countries underlie its importance to U.S. policymakers, U.S. partners, and U.S. rivals.

For more background, see CRS Report R45025, Iraq: Background and U.S. Policy, by Christopher M. Blanchard.

|

After the Islamic State: Cooperation, Competition, and Chaos

U.S. and other international military forces have remained in Iraq in the wake of the Islamic State's 2017 defeat at the Iraqi government's invitation, despite some Iraqis' demands for their departure. Iran, having also aided Iraqi efforts against the Islamic State from 2014 to 2017, has cultivated and sustained ties to several anti-U.S. Iraqi entities, including elements of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) originally recruited as anti-IS volunteers and now recognized under Iraqi law as state security personnel. Iran has used some of these entities as proxies to advance its interests in Iraq. Other Iraqis have continued to oppose what they regard as Iranian and other non-U.S. foreign interference in Iraq. In this context, successive Iraqi administrations have faced countervailing pressures in their efforts to balance Iraq's foreign ties. Domestic reform efforts have languished, arguably constrained by domestic infighting and corruption, subordinated to the imperatives of the war with the Islamic State, and complicated by demands of powerful, competing foreign partners.

Iraq's national election in May 2018 held out the promise of a fresh start for the country after the war with the Islamic State group, but low turnout and an inconclusive result instead produced paralysis. Pro-Iran factions did well in the election, but did not achieve a controlling interest. Their rivals secured influential levels of representation, but did not present unified leadership or an alternative domestic agenda. Months of negotiation in 2018 produced a compromise government under the leadership of Prime Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi, but his lack of an individual political mandate and his reliance on the consensus of fractious political blocs appear to have diluted his government's efforts at reform. Meanwhile, tensions between the United States and Iran increased steadily during this period, as U.S. officials implemented more intense sanctions on Iran and Iranian leaders used proxies to undermine regional security in defiance of the Trump Administration's "maximum pressure" campaign.1

By October 2019, Iraqi citizens' frustrations with endemic corruption, economic stagnation, poor service delivery, and foreign interference had multiplied and ignited a mass protest movement demanding fundamental political change. Iraqi political rivals and competing foreign powers appear to have viewed this movement and its demands largely through the lenses of their pre-existing antagonisms and insecurities, calculating what protest-driven reform might mean for their respective interests. Arguably, Iran-aligned groups have worked to forestall political outcomes that could threaten their power to shape security in Iraq and to entrench pro-Iran figures and militia groups inside Iraq's national security apparatus. U.S. officials have embraced some protestors' calls for reform while expressing concern about the empowerment of Iranian proxies and wariness about Iraq's future alignment.2 Meanwhile, some Iraqi security forces and Iran-backed militias have violently suppressed protests, killing more than 500 people, wounding thousands, and fueling growing domestic and international anxiety over Iraq's future.

U.S.-Iran Confrontation Intensifies

Iran's government supported insurgent attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq during the U.S. presence from 2003 to 2011. From 2012 through 2017, U.S.-Iranian competition in Iraq remained largely contained and relatively nonviolent. However, in 2018 and 2019, U.S. officials attributed a series of indirect fire attacks on some U.S. and Iraqi installations to Iranian proxy forces. During unrest in southern Iraq during summer 2018, the State Department directed the temporary evacuation of U.S. personnel and the temporary closure of the U.S. Consulate in Basra after indirect fire attacks on the consulate and the U.S. Embassy compound in Baghdad. U.S. officials attributed the attacks to Iran-backed forces and said that the United States would hold Iran accountable and respond directly to future attacks on U.S. facilities or personnel by Iran-backed entities.3 In May 2019, the State Department ordered the departure of nonemergency U.S. government personnel from Iraq, citing an "increased threat stream."4 The Administration extended the ordered departure through November 2019, and, in December 2019, notified Congress of its plan to reduce personnel levels in Iraq on a permanent basis.

In December 2019, U.S. officials reiterated warnings that the United States would respond forcefully to any attacks on U.S. persons or interests in Iraq and the wider region. After a rocket attack on an Iraqi military base killed a U.S. citizen contractor and wounded others near Kirkuk, Iraq on December 27, U.S. military forces launched airstrikes against facilities and personnel affiliated with Iran-backed groups in Iraq and Syria. In western Iraq, the U.S. strikes killed and wounded dozens of personnel associated with the U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization Kata'ib Hezbollah (KH, Figure 5), who were operating as elements of Iraq's state-affiliated Popular Mobilization Forces.

Iraqi officials protested the December 29 U.S. attacks on Kata'ib Hezbollah as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty, and, days later, Kata'ib Hezbollah members and other figures associated with Iran-linked militias and PMF units marched to the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad and damaged property, setting outer buildings on fire. Iraqi officials and security forces reestablished order outside the embassy, but tensions remained high, with KH supporters and other pro-Iran figures threatening further action and vowing to expel the United States from Iraq by force if necessary.

In the early morning hours of January 3 (Iraq local time), a U.S. airstrike near Baghdad International Airport hit a convoy carrying Iranian Major General and Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF) commander Qasem Soleimani, killing him and KH founder and Iraqi PMF leader Jamal Ja'far al Ibrahimi (commonly referred to as Abu Mahdi al Muhandis). U.S. officials hold Solemani responsible for a lethal campaign of insurgent attacks on U.S. forces during the U.S. military presence in Iraq from 2003 to 2011 that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of U.S. soldiers and injuries to thousands more. Soleimani and Muhandis have played central roles in Iran's efforts to develop and maintain ties to armed groups in Iraq over the last 20 years, and Soleimani long served as a leading Iranian emissary to Iraqi political and security figures. Muhandis had served as PMF Deputy Commander.

The U.S. operation was met with shock in Iraq, and Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi and President Barham Salih issued statements condemning the strike as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty. The prime minister called for and then addressed a special session of the Council of Representatives on January 5, recommending that the quorum of legislators present vote to direct his government to ask all foreign military forces to leave the country.5 Most Kurdish and Sunni COR members reportedly boycotted the session.

Those COR members present adopted by voice vote a parliamentary decision directing the Iraqi government to:

- withdraw its request to the international anti-IS coalition for military support;

- remove all foreign forces from Iraq and end the use of Iraq's territory, waters, and airspace by foreign militaries;

- protest the U.S. airstrikes at the United Nations and in the U.N. Security Council as breaches of Iraqi sovereignty; and

- investigate the U.S. strikes and report back to the COR within seven days.

On January 6, Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi met with U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Matthew Tueller and informed him of the COR's decision, requesting that the United States begin working with Iraq to implement the COR decision. In a statement, the prime minister's office reiterated Iraq's desire to avoid war, to resist being drawn into conflict between outsiders, and to maintain cooperative relations with the United States based on mutual respect.6 Amid subsequent reports that some U.S. military forces in Baghdad were planning to imminently reposition for force-protection reasons and "to prepare for onward movement," Secretary of Defense Mark Esper stated, "There has been no decision made to leave Iraq, period."7

On January 9, Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi asked Secretary of State Michael Pompeo to "send delegates to Iraq to prepare a mechanism to carry out the parliament's resolution regarding the withdrawal of foreign troops from Iraq."8 On January 10, the State Department released a statement saying "At this time, any delegation sent to Iraq would be dedicated to discussing how to best recommit to our strategic partnership, not to discuss troop withdrawal, but our right, appropriate force posture in the Middle East."9

Leaders in Iraq's Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) have endorsed the continuation of foreign military support for Iraq, but may be wary of challenging the authority of the national government if Baghdad issues departure orders to foreign partners. On January 7, Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) leader and former KRG President Masoud Barzani said, "we cannot be involved in any proxy wars."10

On January 8, Iran fired missiles at Iraqi military facilities hosting U.S. forces, damaging infrastructure but avoiding U.S. or Iraqi casualties. President Salih, COR Speaker Mohammed al Halbusi, and Iraq's Foreign Ministry described the Iranian attacks as violations of Iraq's sovereignty. Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi stated that his office was informed verbally as the strikes were under way and reiterated his government's desire to avoid war between outsiders inside of Iraq.11 Kata'ib Hezbollah issued a statement calling for its forces to avoid further provocations in furtherance of efforts to expel U.S. forces through political action, and Qa'is Khazali, leader of the Iran-aligned and U.S.-designated Asa'ib Ahl al Haq militia (AAH, Figure 5), warned that Iraqi groups would take their own revenge for the U.S. strike.12

Implications and Possible Options for the United States

The United States has long faced difficult choices in Iraq, and recent U.S.-Iran violence there appears to be complicating U.S. choices further. Even as the 2003 invasion unseated an adversarial regime, it unleashed more than a decade of violent insurgency and terrorism that divided Iraqis. This created opportunities for Iran to strengthen its influence in Iraq and across the region. Since 2003, the United States has invested both militarily and financially in stabilizing Iraq, but successive Administrations and Congresses have expressed frustration with the results of U.S. efforts. The U.S. government withdrew military forces from Iraq in accordance with Iraq's sovereign requests in 2011, but deteriorating security conditions soon led Iraqi leaders to request that U.S. and other international forces return. An exchange of diplomatic notes provided for the return of U.S. forces in 2014, and both the 2014 notes and the 2008 U.S.-Iraq Strategic Framework Agreement contain clauses providing for one-year notice before termination.

Since 2014, U.S. policy toward Iraq has focused on ensuring the defeat of the Islamic State as a transnational insurgent and terrorist threat, while laying the groundwork for what successive U.S. Administrations have expressed hope could be a long-term bilateral security, diplomatic, and economic partnership with Iraqis. U.S. and other foreign troops have operated in Iraq (Figure 1) at the invitation of the Iraqi government to conduct operations against Islamic State fighters, advise and assist Iraqi operations, and train and equip Iraqi security forces, including peshmerga forces associated with the Kurdistan Regional Government. Cooperative efforts have reduced the Islamic State threat, but Iraqi security needs remain considerable and officials on both sides never finalized detailed proposals for defining and pursuing a long-term collaboration.

Security cooperation has been the cornerstone of U.S.-Iraqi relations since 2014, but leaders in both countries have faced pressure to reexamine the impetus and terms for continued bilateral partnership. Some Iraqi political groups—including some with ties to Iran—pushed for U.S. and other foreign troops to depart in 2019, launching a campaign in the COR for a vote to evict U.S. forces. However, leading Iraqi officials rebuffed their efforts, citing the continued importance of foreign support to Iraq's security and the government's desire for security training for Iraqi forces. Domestic upheaval in Iraq and U.S.-Iran conflict in the months since now appear to have altered the views of some Iraqi officials, creating new opportunities for Iraqis who have long sought push U.S. and other foreign forces out.

The Trump Administration has sought proactively to challenge, contain, and roll back Iran's regional influence, while it has attempted to solidify a long-term partnership with the government of Iraq and to support Iraq's sovereignty, unity, security, and economic stability.13 These parallel (and sometimes competing) goals may raise several policy questions for U.S. officials and Members of Congress, including questions with regard to

- the makeup and viability of the Iraqi government;

- Iraqi leaders' approaches to Iran-backed groups and the future of Iraqi militia forces;

- Iraq's compliance with U.S. sanctions on Iran;

- the future extent and roles of the U.S. military presence in Iraq;

- the terms and conditions associated with U.S. security assistance to Iraqi forces;

- U.S. relations with Iraqi constituent groups such as the Kurds; and

- potential responses to U.S. efforts to contain or confront Iran-aligned entities in Iraq or elsewhere in the region.

The U.S.-Iran confrontation in December 2019 and January 2020 illustrated the potential stakes of conflict involving Iran and the United States in Iraq for these issues.

Possible Scenarios

New or existing U.S. attempts to sideline Iran-backed Iraqi groups, via sanctions or other means, might challenge Iran's influence in Iraq in ways that could serve stated U.S. government goals vis-a-vis Iran, but also might entail risk inside Iraq. While a wide range of Iraqi actors have ties to Iran, the nature of those ties differs, and treating these diverse groups uniformly risks ostracizing potential U.S. partners or neglecting opportunities to create divisions between these groups and Iran. Recent strikes notwithstanding, the United States government has placed sanctions on some Iran-linked groups and individuals for threatening Iraq's stability, for violating the human rights of Iraqis, and for involvement in terrorism. Some analysts have argued "the timing and sequencing" of sanctions "is critical to maximizing desired effects and minimizing Tehran's ability to exploit Iraqi blowback."14 This logic may similarly apply to any forceful U.S. responses to attacks or provocations by Iran-aligned Iraqis.

U.S. efforts to counter Iranian activities in Iraq and elsewhere in the region also have the potential to complicate the pursuit of other U.S. in Iraq, including U.S. counter-IS operations and training. When President Trump in a February 2019 interview referred to the U.S. presence in Iraq as a tool to monitor Iranian activity, several Iraqi leaders raised concerns.15 Iran-aligned Iraqi groups then referred to President Trump's statements in their 2019 political campaign to force a U.S. withdrawal. As discussed above, U.S. strikes against Iranian and Iranian-aligned personnel in Iraq have precipitated a renewed effort to force Iraq's government to rescind its invitation to foreign militaries to operate in Iraq. Some Iran-aligned Iraqi groups have sought to exploit U.S. statements since the January 5 COR vote, arguing that the United States will not comply with sovereign Iraqi requests with regard to foreign troops.16

More broadly, future U.S. conflict with Iran and its allies in Iraq could disrupt relations among parties to an emergent transitional government in Baghdad, or even contribute to conditions leading to civil conflict among Iraqis, undermining the U.S. goal of ensuring the stability and authority of the Iraqi government. Iran also may seek to avoid these outcomes, concerned that conflict in Iraq could threaten its security.

With the mandate for continued security support now in question, U.S. decision-makers may consider a range of possible scenarios and policy options. Restoring the status quo ante in the wake of U.S.-Iran violence may be complicated by the apparent hardening of some Iraqis' political views of U.S. forces and of the implications of partnership with the United States for Iraq's security. A new Iraqi government or election could empower new decision-makers, but there is no guarantee that those in power would hold more favorable views of the United States or come to different conclusions about the merits of continued foreign military support.

Force-protection requirements led to a pause in U.S. and coalition training and advisory missions in January 2020, as Iran-aligned Iraqis and Iranian officials threatened retaliatory attacks against U.S. military targets.17 Enduring threats from Iran or Iran-aligned Iraqi groups, potentially amplified by any further rounds of conflict or facilitated by any weakening of the Iraqi security forces, could make maintaining the U.S. presence less viable or desirable. Armed groups could adopt a more actively hostile posture under circumstances in which the United States is perceived to be ignoring or defying requests from Iraqi authorities or to be violating Iraq's sovereignty.

A reduced and redefined U.S. military presence—if acceptable to Iraqis—could pursue a limited and less controversial mission set (e.g., more proscribed military operations or a focus solely on training), but also might still entail considerable force-protection requirements if prevailing security conditions persist or confrontation recurs. Iraqi leaders may face domestic political opposition in negotiating even a reduced enduring U.S. presence.

Other international actors appear more willing and capable of contributing to training efforts than to active counterterrorism operations and could compensate for that component of any reduced U.S. presence if Iraq's government endorses new arrangements. However, foreign troop contributors rely implicitly on force protection from the United States, and the U.S.-Iran confrontation in January 2020 also led to a temporary halt to the NATO training mission in Iraq. Some foreign troop contributors announced plans to reduce deployments in Iraq in conjunction with the crisis.

Recent U.S. assessments of the counter-IS campaign and the capabilities of Iraqi forces suggest that a reduced or training-only presence could create security risks. U.S. officials judge that the Islamic State poses a continuing and reorganizing threat in Iraq (see "Security Challenges Persist Across Iraq" below), while Iraqi forces remain dependent on international support for intelligence and air support to conduct effective operations. Islamic State fighters and other armed groups presumably could take advantage of any reduced operating capacity or tempo by Iraqi security forces associated with changes in coalition support or presence. A precipitous withdrawal of most or all U.S. and/or coalition military forces, whether preemptive or required, could carry greater security risks. Iran could be compelled to provide greater military assistance or operate more forcefully in Iraq to compensate for a loss of other foreign support for Iraq. This could expose Iran to greater criticism from Iraqis opposed to Iranian intervention and/or to foreign intervention in Iraq more broadly.

Under circumstances in which Iraqi authorities insist on changes or reductions in U.S. and coalition posture, compliance might have some diplomatic and strategic benefits. While Iranian allies could be expected to welcome such changes, other nationalist Iraqis might see the United States and other international actors as respecting Iraqi sovereignty and thus remain open to later attempts to redefine the terms of foreign security partnerships. As noted above, U.S. defiance, whether real or perceived, could invite backlash.

|

Is the United States Considering Sanctions on Iraq?18

President Trump has threatened to impose sanctions on Iraq, if Iraq forces U.S. troops to withdraw on unfriendly terms.19 Depending on the form such sanctions might take, they could elicit reciprocal hostility from Iraq and could complicate Iraq's economic ties to its neighbors and U.S. partners in Europe and Asia. If denied opportunities to build economic ties to the United States and U.S. partners, Iraqi leaders could instead mover closer to Iran, Russia, and/or China with whom they have already established close ties. Since 2018, Iraqi leaders have sought and received temporary relief from U.S. sanctions on Iran, in light of Iraq's continuing dependence on purchases of natural gas and electricity from Iran.20 The Trump Administration has serially granted temporary permissions for these transactions to continue, while encouraging Iraq to diversify its energy relationships with its neighbors and to become more energy independent. The Administration's most recent such sanction exemption for Iraq is set to expire in February 2020.

Some press reporting suggests that Administration officials have begun preparing to implement the President's sanctions threat if necessary and considering potential effects and consequences.21 On May 19, 2019, the Trump Administration renewed the national emergency with respect to the stabilization of Iraq declared in Executive Order 13303 (2003) as modified by subsequent executive orders.22 Sanctions could be based on the national emergency declared in the 2003 Executive Order, or the President could declare that recent events constitute a new, separate emergency under authorities stated in the National Emergency Act and International Emergency Economic Powers Act (NEA and IEEPA, respectively). Sanctions under IEEPA target U.S.-based assets and transactions with designated individuals; while a designation might not reap significant economic disruption, it can send a significant and purposefully humiliating signal to the international community about an individual or entity. The National Emergencies Act, at 50 U.S.C. 1622, provides a legislative mechanism for Congress to terminate a national emergency with enactment of a joint resolution of disapproval.

Short of declaring a national emergency, however, the President has broad authority to curtail foreign assistance (throughout the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2151 et seq.), and related authorizations and appropriations), sales and leases of defense articles and services (particularly section 3 of the Arms Export Control Act; 22 U.S.C. 2753), and entry into the United States of Iraqi nationals (Immigration and Nationality Act; particularly at 8 U.S.C. 1189).

|

Possible Issues for Congress

Although current policy questions relate to the potential reduction or elimination of ongoing U.S. military efforts in Iraq, successive U.S. Administrations already have sought to keep U.S. involvement and investment minimal relative to the 2003-2011 era. The Obama and Trump Administrations have pursued U.S. interests through partnership with various entities in Iraq and the development of those partners' capabilities, rather than through extensive U.S. military deployments or outsized U.S. aid investments. That said, the United States remains the leading provider of security and humanitarian assistance to Iraq and supports post-IS stabilization activities across the country through grants to United Nations agencies and other entities. According to inspectors general reporting, reductions in the size of the U.S. civilian presence in Iraq during 2019 affected the ability of U.S. agencies to implement and monitor U.S. programs.23 Significant further reductions in U.S. civilian or military personnel levels could have additional implications for programs and conditions in Iraq and may require U.S. and Iraqi leaders to consider and pursue alternatives.

Congress has continued to authorize and appropriate aid for Iraq, but has not enacted comprehensive legislation defining its views on Iraq or offering alternative frameworks for bilateral partnership. Several enacted provisions have encouraged the executive branch to submit strategy and spending plans with regard to Iraq since 2017. The Trump Administration has requested appropriation of additional U.S. assistance since 2017, but also has called on Iraq to increase its contributions to security and stabilization efforts, while reorienting U.S. train and equip efforts to prioritize minimally viable counterterrorism capabilities and deemphasizing comprehensive goals for strengthening Iraq's security forces.

In December 2019, Congress enacted appropriations (P.L. 116-93 and P.L. 116-94) and authorization (P.L. 116-92) legislation providing for continued defense and civilian aid and partnership programs in Iraq in response to the Trump Administration's FY2020 requests. Appropriated funds in some cases are set to remain available through September 2021 to support military and civilian assistance should U.S.-Iraqi negotiations allow.

Members of Congress monitoring developments in Iraq, considering new Administration aid requests, and/or conducting oversight of executive branch initiatives may consider a range of related questions, including:

- What are U.S. interests in Iraq? How can U.S. interests best be achieved?

- How necessary is a continued U.S. military presence in Iraq? What alternatives exist? What tradeoffs and benefits might these alternatives pose?

- What effect might a precipitous U.S. withdrawal from Iraq have on the security of Iraq? How might the redeployment of Iraq-based forces to other countries in the CENTCOM area of responsibility affect regional perceptions and security?

- How might the withdrawal of U.S. and other international forces shape Iraqi political dynamics, including the behavior of government and militia forces toward protestors and the relationships between majority and minority communities across the country?

- If U.S.-Iraqi security cooperation were to end, how might Iraq compensate? If the United States were to impose sanctions on Iraq or defy Iraqi orders to leave, how might Iraq respond? How might related scenarios affect U.S. security interests?

Table 1. Iraq: At a Glance

|

|

|

Area: 438,317 sq. km (slightly more than three times the size of New York State)

Population: 40.194 million (July 2018 estimate), ~58% are 24 years of age or under

Internally Displaced Persons: 1.4 million (October 31, 2019)

Religions: Muslim 99% (55-60% Shia, 40% Sunni), Christian <0.1%, Yazidi <0.1%

Ethnic Groups: Arab 75-80%; Kurdish 15-20%; Turkmen, Assyrian, Shabak, Yazidi, other ~5%.

Gross Domestic Product [GDP; growth rate]: $224.2 billion (2018); -0.6% (2018)

Budget (revenues; expenditure; balance): $89 billion, $112 billion, -$23 billion (2019 est.)

Percentage of Revenue from Oil Exports: 92% (2018)

Current Account Balance: $15.5 billion (2018)

Oil and natural gas reserves: 142.5 billion barrels (2017 est., fifth largest); 3.158 trillion meters3 (2017 est.)

External Debt: $73.43 billion (2017 est.)

Foreign Reserves: ~$64.7 billion (2018)

|

Sources: Graphic created by CRS using data from U.S. State Department and Esri. Country data from CIA, The World Factbook, International Monetary Fund, Iraq Ministry of Finance, and International Organization for Migration.

|

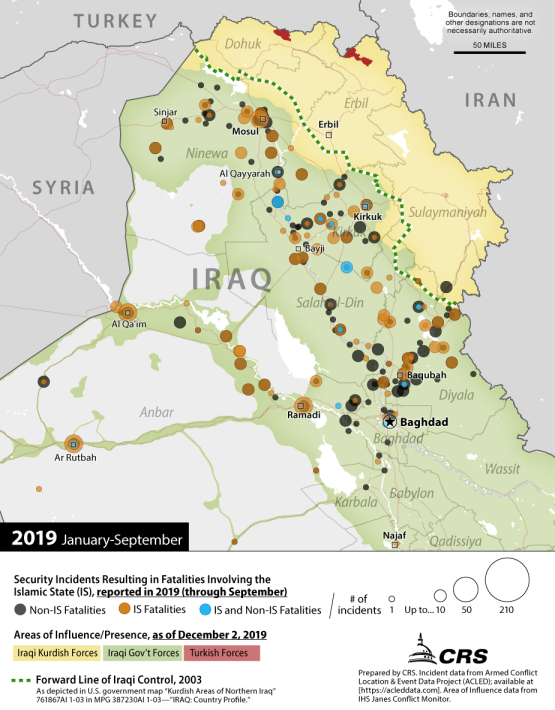

Figure 1. Iraq: Areas of Influence and Operation

As of December 2, 2019

|

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service using ArcGIS, IHS Markit Conflict Monitor, U.S. government, and United Nations data.

Notes: Areas of influence are approximate and subject to change.

|

Political Dynamics

Transition Expected in 2020 as Iraqis Demand Change

Since the U.S.-led ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraq's Shia Arab majority has exercised greater national power both in concert and in competition with the country's Sunni Arab and Kurdish minorities. Sunnis led Hussein's regime, which repressed Kurdish, Shia, and Sunni opposition movements. While intercommunal identities and rivalries remain politically relevant, competition among Shia movements and coalition building across communal groups had become major factors in Iraqi politics as of 2019. Notwithstanding their ethnic and religious diversity and political differences, many Iraqis advance similar demands for improved security, government effectiveness, and economic opportunity. Some Iraqi politicians have broadened their political and economic narratives in an attempt to appeal to disaffected citizens across the country. Years of conflict, poor service delivery, corruption, and sacrifice have strained the population's patience with the status quo, adding to the pressures that leaders face from the country's uncertain domestic and regional security environment.

In 2019, a mass protest movement began channeling these nationalist, nonsectarian sentiments and frustrations into potent rejections of the post-2003 political order, the creation of which many Iraqis attribute to U.S. intervention in Iraq.24 Governance in Iraq since 2003 has reflected a quota-based distribution of leadership and administrative positions based on ethno-sectarian identity and political affiliation. Voters have elected legislative representatives based on a party list system, but government formation has been determined by deal-making that has often included unelected elites and been influenced by foreign powers, including Iran and the United States.

In principle, this apportionment system, referred to in Iraq as muhassasa, has deferred potential conflict between identity groups and political rivals by dividing influence and access to state resources along negotiated lines that do not completely exclude any major group.25 In practice, the system has enabled patronage networks to treat governance and administrative functions as a source of private benefit and political sustenance. Government service delivery and economic opportunity have suffered. Corruption has spread, resulting in abuse of power and enabling foreign exploitation. The result has been what one U.S. official described in December 2019 as a "growing revulsion for Iraq's political elite by the rest of the population."26

Protestor calls for improved governance, reliable local services, more trustworthy and capable security forces, and greater economic opportunity broadly correspond to stated U.S. goals for Iraq. However, U.S. officials have not endorsed demands for an immediate transition, and stated in December 2019 that they were taking care "not to portray these protestors as pro-American."27

Instead, U.S. officials have advocated for protestors' rights to demonstrate and express themselves freely without coercive force or undue restrictions on media and communications.28 In a series of statements over several weeks, U.S. officials urged Iraqi leaders to respond seriously to protestors' demands and to avoid attacks against unarmed protestors, while expressing broad U.S. goals for continued partnership with "a free and independent and sovereign Iraq."29

- In November, the White House called on the Iraqi government to "fulfill President [Barham] Salih's promises to pass electoral reform and hold early elections."30

- After the killing of dozens of additional protestors in late November, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo and other officials said that the Administration "will not hesitate" to use tools at its disposal, "including designations under the Global Magnitsky Act, to sanction corrupt individuals who are stealing the public wealth of the Iraqi people and those killing and wounding peaceful protesters."31

- On December 2, Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs David Schenker called on Iraqi leaders "to investigate and hold accountable" individuals responsible for attacks on protestors and to reject "the distorting influence Iran has exerted on the political process."32

- On December 6, the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced Global Magnitsky sanctions against "three leaders of Iran-backed militias in Iraq that opened fire on peaceful protests" and an Iraqi millionaire businessman "for bribing government officials and engaging in corruption at the expense of the Iraqi people."33 Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said, "Iran's attempts to suppress the legitimate demands of the Iraqi people for reform of their government through the slaughter of peaceful demonstrators is appalling."

U.S. officials acknowledge that "there have been Iraqi military leaders and units implicated" in some cases of violence, but also have noted that there is uncertainty about responsibility in other cases.34 U.S. officials have stated they are actively reviewing reports of violence against protestors to inform future decisions about the participation of Iraqi officers and military and federal police units in U.S. security assistance programs, even if the future of such assistance programs is now in question.35 Some Iraqis perceive U.S. strikes in December 2019 and January 2020 as violations of Iraq sovereignty and may question related U.S. commitments.

Prime Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi's resignation marked the beginning of what may be an extended political transition period that reopens several contentious issues for debate and negotiation. Principal decisions now before Iraqi leaders concern 1) identification and endorsement of a caretaker prime minister and cabinet, 2) implementation of adopted electoral system reforms, and 3) the proposed holding of parliamentary and provincial government elections in 2020. Following new elections, government formation negotiations would recur, taking into consideration domestic and international developments over the interim period.

Selection of a caretaker administration has been delayed amid differences of opinion over which political entities have the right to nominate candidates and whether or not specific nominees are likely to enjoy the support of protest movement. The Bin'a bloc (see "May 2018 Election, Unrest, and Government Formation" below) has been identified as the largest bloc for the purposes of selecting a prime ministerial candidate to replace Abd al Mahdi, but Bin'a leaders, other COR members, and President Salih have differed over the appropriateness of Bin'a candidates. A fifteen-day deadline for the naming of a replacement prime minister lapsed in mid-December.

The COR adopted a new electoral law and a new law for the Independent High Electoral Commission (IHEC) in December, replacing Iraq's list-based election system with an individual candidate- and district-based system that may require a census to be effectively implemented. Iraq has not conducted a census since 1997, and census plans discussed since 2003 have been accompanied by significant political tensions.

Early elections under a revamped system could introduce new political currents and leaders, but fiscal pressures, political rivalries, and the limited capacity of some state institutions may present lasting hurdles to reform. Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Joey Hood told Senators in December that, "nothing will change [in Iraq] until political leaders decide that government agencies should provide public services rather than serve as ATM machines for their parties. Until that happens, the people's demands for a clean and effective government will not be met, no matter who serves as Prime Minister or in Cabinet positions."36

May 2018 Election, Unrest, and Government Formation

Iraqis held national legislative elections in May 2018, electing members for four-year terms in the 329 seat Council of Representatives (COR), Iraq's unicameral legislature. Turnout was lower in the 2018 COR election than in past national elections, and reported irregularities led to a months-long recount effort that delayed certification of the results until August. Political factions spent the summer months negotiating in a bid to identify the largest bloc within the COR—the parliamentary bloc charged with proposing a prime minister and new Iraqi cabinet (Figure 2).

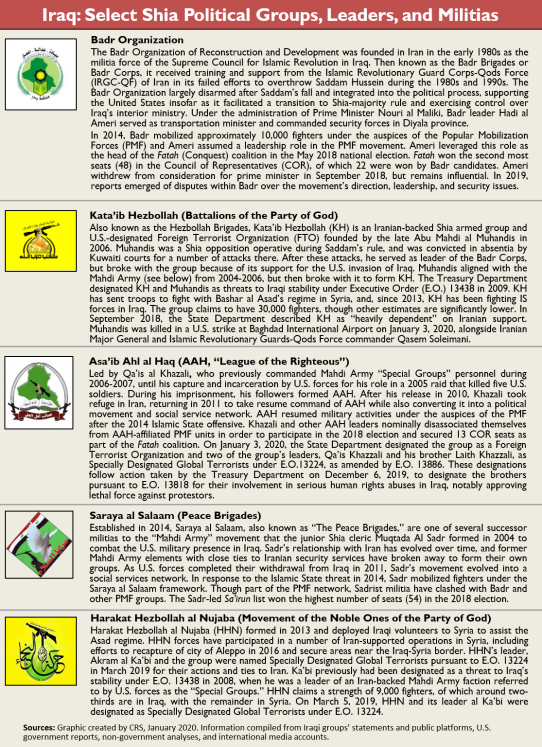

The distribution of seats and alignment of actors precluded the emergence of a dominant coalition (see textbox below). The Sa'irun (On the March) coalition led by populist Shia cleric and longtime U.S. antagonist Muqtada al Sadr's Istiqama (Integrity) list placed first in the election (54 seats), followed by the predominantly Shia Fatah (Conquest) coalition led by Hadi al Ameri of the Badr Organization (48 seats). Fatah includes several individuals formerly associated with the Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC) and its militias—the mostly Shia PMF. Those elected include some figures with ties to Iran (see "The Future of the Popular Mobilization Forces" and Figure 5 below).

Former Prime Minister Haider al Abadi's Nasr (Victory) coalition underperformed expectations to place third (42 seats), while former Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki's State of Law coalition, Ammar al Hakim's Hikma (Wisdom) list, and Iyad Allawi's Wataniya (National) list also won significant blocs of seats. Among Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) won the most seats, and smaller Kurdish opposition lists protested alleged irregularities. As negotiations continued, Nasr and Sa'irun members joined with others to form the Islah (Reform) bloc in the COR, while Fatah and State of Law formed the core of a rival Bin'a (Reconstruction) bloc.

Under an informal agreement developed through the formation of successive governments, Iraq's Prime Minister has been a Shia Arab, the President has been a Kurd, and the COR Speaker has been a Sunni Arab.

|

Figure 2. Iraq: Select Political and Religious Figures

|

|

|

In September 2018, the newly elected COR elected Mohammed al Halbousi, the Sunni Arab governor of Anbar, as COR Speaker. Hassan al Kaabi of the Sa'irun list and Bashir Hajji Haddad of the KDP were elected as First and Second Deputy Speaker, respectively.

|

Iraq's 2018 National Legislative Election

Seats won by Coalition/Party

|

Coalition/Party

|

Seats Won

|

|

Sa'irun

|

54

|

|

Fatah

|

48

|

|

Nasr

|

42

|

|

Kurdistan Democratic Party

|

25

|

|

State of Law

|

25

|

|

Wataniya

|

21

|

|

Hikma

|

19

|

|

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan

|

18

|

|

Qarar

|

14

|

|

Others

|

63

|

Source: Iraq Independent High Electoral Commission.

|

In October 2018, the COR met to elect Iraq's President, with rival Kurdish parties nominating competing candidates.37 COR members chose the PUK candidate–former KRG Prime Minister and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Barham Salih—in the second round of voting. Salih, in turn, named former Oil Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi as Prime Minister-designate and directed him to assemble a slate of cabinet officials for COR approval. Abd al Mahdi, a Shia Arab, was a consensus leader acceptable to the rival Shia groups in the Islah and Bina blocs, but he does not lead a party or parliamentary group of his own.38 Through 2019, this appeared to limit Abd al Mahdi's ability to assert himself relative to others who have large followings or command armed factions. COR confirmed most of Abd al Mahdi's cabinet nominees immediately, but the main political blocs remained at an impasse for months over several cabinet positions.

As government formation talks proceeded during summer 2018, large protests and violence in southern Iraq highlighted some citizens' outrage with electricity and water shortages, lack of economic opportunity, and corruption. Unrest appeared to be amplified in some instances by citizens' anger about heavy-handed responses by security forces and militia groups. Dissatisfaction exploded in the southern province of Basra during August and September 2018, culminating in several days and nights of mass demonstrations and the burning by protestors of the Iranian consulate in Basra and the offices of many leading political groups and militia movements. Similar conditions, sentiments, and events resurfaced in 2019, fueling the mass protest movement that demanded and secured Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi's resignation at the end of November 2019. A transitional administration and any newly elected leaders are expected to face significant political pressure to address popular demands and grievances.

Security Challenges Persist Across Iraq

Although the Islamic State's exclusive control over distinct territories in Iraq ended in 2017, the U.S. intelligence community assessed in 2018 that the Islamic State had "started—and probably will maintain—a robust insurgency in Iraq and Syria as part of a long-term strategy to ultimately enable the reemergence of its so-called caliphate."39 In January 2019, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats told Congress that the Islamic State "remains a terrorist and insurgent threat and will seek to exploit Sunni grievances with Baghdad and societal instability to eventually regain Iraqi territory against Iraqi security forces that are stretched thin."40 U.S. officials have reported that through October 2019, the Islamic State group in Iraq continued "to solidify and expand its command and control structure in Iraq, but had not increased its capabilities in areas where the Coalition was present."41 Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) judged that IS fighters "continued to regroup in desert and mountainous areas where there is little to no local security presence" but were "incapable of conducting large-scale attacks."

The legacy of the war with the Islamic State strains security in Iraq in two other important ways. First, the Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC) and its militias—the mostly Shia Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) recruited to fight the Islamic State—have been recognized as enduring components of Iraq's national security establishment. This is the case even as some PMF units appear to operate outside the bounds of their authorizing legislation and the control of the Prime Minister. The U.S. intelligence community considers Iran-linked Shia elements of the PMF to be the "the primary threat to U.S. personnel" in Iraq.42

Second, national and KRG forces remain deployed across from each other along contested lines of control while their respective leaders are engaged in negotiations over a host of sensitive issues. Following a Kurdish referendum on independence in 2017, the Iraqi government expelled Kurdish peshmerga from some disputed territories they had secured from the Islamic State, and IS fighters now appear to be exploiting gaps in ISF and Kurdish security to survive. PMF units remain active throughout the territories in dispute between the Iraqi national government and the federally recognized Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq, with local populations in some areas opposed to the PMF presence.

Seeking the "Enduring Defeat" of the Islamic State

As of January 2020, Iraqi security operations against IS fighters are ongoing in governorates in which the group formerly controlled territory or operated—Anbar, Ninewa, Salah al Din, Kirkuk, and Diyala. Some of these operations are conducted without U.S. and coalition support, while others are partnered with U.S. and coalition forces or supported by U.S. and coalition forces. The Coalition and Iraqi operations are intended to disrupt IS fighters' efforts to reestablish themselves as an organized threat and keep them separated from population centers. As noted above, U.S.-Iran tensions and violence led to the temporary suspension of U.S. and Coalition counter-IS operations and related training in January 2020 for force-protection reasons.

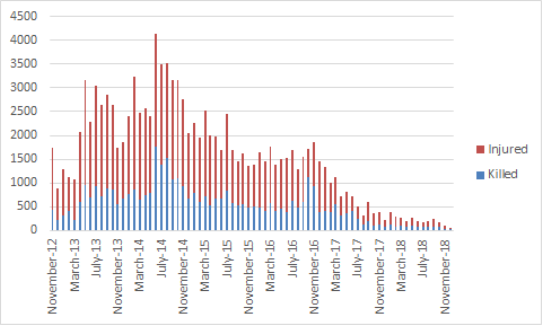

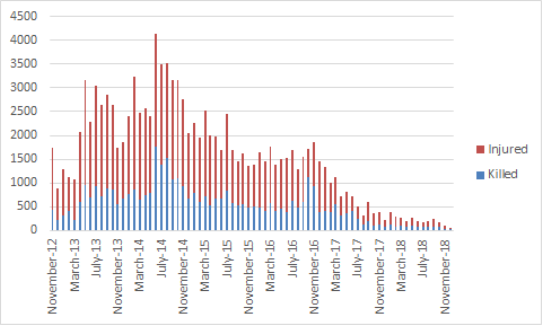

Press accounts and U.S. government reports describe continuing IS attacks on Iraqi Security Forces and Popular Mobilization Forces, particularly in rural areas. Independent analysts have described dynamics in parts of these governorates in which IS fighters threaten, intimidate, and kill citizens in areas at night or where Iraq's national security forces are absent.43 In some areas, new displacement has occurred as civilians have fled IS attacks. Overall, however, through 2018, violence against civilians dropped considerably from its 2014 highs (Figure 3). In cities like Mosul and Baghdad residents and visitors enjoyed increased freedom of movement and security, although IS activity was reported in Mosul and fatal security incidents have occurred in areas near Baghdad and several other locations since 2019 (Figure 4).

|

Figure 3. Estimated Iraqi Civilian Casualties from Conflict and Terrorism

United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq Estimates of Monthly Casualties, 2012-2018

|

|

|

Source: United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq. Some months lack data from some governorates.

|

U.S. officials reported that through October 2019, the Islamic State group in Iraq continued "to solidify and expand its command and control structure in Iraq, but had not increased its capabilities in areas where the Coalition was present."44 CJTF-OIR judged that IS fighters "continued to regroup in desert and mountainous areas where there is little to no local security presence" but were "incapable of conducting large-scale attacks."

November 2019 oversight reporting cited CJTF-OIR as describing the Iraqi Security Forces as lacking sufficient personnel to hold and constantly patrol remote terrain. According to the cited CJTF-OIR reporting to the DOD inspector general, Iraq's Counterterrorism Service (CTS) has "dramatically improved" its ability "to integrate, synchronize, direct, and optimize counterterrorism operations," and some CTS brigades are able to sustain unilateral operations.45

U.S. officials report that ISF units are capable of conducting security operations in and around population centers and assaulting identified targets, but judge that many ISF units lack the will and capability to "find and fix" targets or exploit intelligence without assistance from coalition partners. According to November 2019 reporting:

CJTF-OIR said that most commands within the ISF will not conduct operations to clear ISIS insurgents in mountainous and desert terrain without Coalition air cover, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), and coordination. Instead, ISF commands rely on the Coalition to monitor "points of interest" and collect ISR for them. Despite ongoing training, CJTF-OIR said that the ISF has not changed its level of reliance on Coalition forces for the last 9 months and that Iraqi commanders continue to request Coalition assets instead of utilizing their own systems.46

These conditions and trends suggest that while the capabilities of IS fighters remain limited at present, IS personnel and other armed groups could exploit persistent weaknesses in ISF capabilities to reconstitute the threats they pose to Iraq and neighboring countries. This may be particularly true with regard to remote areas of Iraq or under circumstances where security forces remain otherwise occupied with crowd control or force-protection measures. A reconstituted IS threat might not reemerge rapidly under these circumstances, but the potential is evident.

Oversight reporting to Congress in 2018 suggested that DOD then-estimated that the Iraq Security Forces were "years, if not decades" away from ending their "reliance on Coalition assistance," and DOD expected "a generation of Iraqi officers with continuous exposure to Coalition advisers" would be required to establish a self-reliant Iraqi fighting force.47 At the time, the Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations (LIG-OCO) judged that these conditions raised "questions about the duration of the OIR mission since the goal of that mission is defined as the 'enduring defeat' of ISIS."48

U.S. and coalition training efforts have shifted to a train-the-trainer and Iraqi ownership approach under the auspices of OIR's Reliable Partnership initiative and the NATO Training Mission in Iraq. Reliable Partnership was redesigned to focus on building a minimally viable counterterrorism capacity among Iraqi forces, with other outstanding capability and support needs to be reassessed after September 2020.

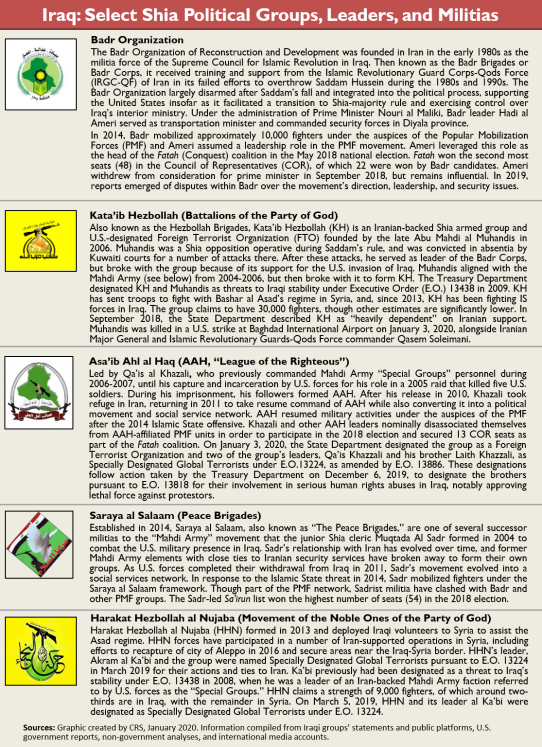

The Future of the Popular Mobilization Forces

Iraq's Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC) and its associated militias—the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF)—were founded in 2014 and have contributed to Iraq's fight against the Islamic State, but they have come to present an implicit, and, at times, explicit challenge to the authority of the state.49 The PMF are largely but not solely drawn from Iraq's Shia Arab majority: Sunni, Turkmen, and Christian PMF militia also remain active. Despite expressing appreciation for PMF contributions to the fight against IS, some Iraqis and outsiders have raised concerns about the future of the PMC/PMF and some of its members' ties to Iran.

Many PMF-associated groups and figures participated in the May 2018 national elections under the auspices of the Fatah coalition headed by Badr Organization leader Hadi al Ameri (Figure 2).50 Ameri and other prominent PMF-linked figures such as Asa'ib Ahl al Haq leader Qa'is al Khazali nominally disassociated themselves from the PMC/PMF in late 2017, in line with legal prohibitions on the participation of PMC/PMF officials in politics.51 Nevertheless, their movements' supporters and associated units remain integral to some ongoing PMF operations, and the Fatah coalition's campaign arguably benefited from its PMF association.

The U.S. Intelligence Community described Iran-linked Shia militia—whether PMF or not—as the "primary threat" to U.S. personnel in Iraq, and suggested that the threat posed by Iran-linked groups will grow as they press for the United States to withdraw its forces from Iraq.52 Several Iraqi militia forces have vowed revenge against the United States and stated their renewed commitment to expelling U.S. forces from Iraq, but some have called for a measured approach and disavowed potential attacks on non-military targets as a means of fulfilling their stated objectives. For example, Kata'ib Hezbollah released a statement in the aftermath of the Iranian missile attack on Iraq saying "emotions must be set aside" to further the project of expelling the United States.53 Asa'ib Ahl al Haq figures denied responsibility for a subsequent rocket attack on the U.S. Embassy while insisting on U.S. military withdrawal and vowing an "earthshattering" response.54

During the 2018 election and in its aftermath, the key unresolved issue with regard to the PMC/PMF has remained the incomplete implementation of a 2016 law calling for the PMF to be incorporated as a permanent part of Iraq's national security establishment. In addition to outlining salary and benefit arrangements important to individual PMF volunteers, the law calls for all PMF units to be placed fully under the authority of the commander-in-chief (Prime Minister) and to be subject to military discipline and organization. Through early 2019, U.S. government reporting stated that while some PMF units were being administered in accordance with the law, most remained outside the law's prescribed structure. This included some units associated with Shia groups identified by U.S. government reports as having received Iranian support.55

|

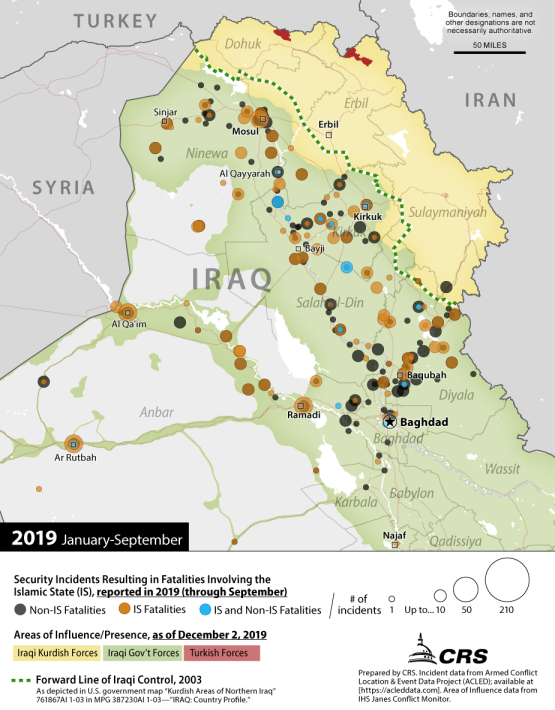

Figure 4. Iraq: Reported Islamic State-Related Security Incidents

January 1, 2019 to September 30, 2019

|

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS. Incident data from Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). Available at https://acleddata.com. Area of Influence data from IHS Janes Conflict Monitor, December 2, 2019.

|

In September 2019, Iraqi officials approved a new organizational and administrative plan for the PMC/PMF in line with Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi's July 2019 decree reiterating his predecessor's demand that the PMF and PMC conform to Iraqi law. According to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), "some PMF brigades followed the decree by shutting down headquarters and turning in weapons, but several Iranian-aligned groups refused to comply."56 The DIA judged earlier this year that "Iranian-affiliated groups within the PMF are unlikely to change their loyalties because of the new order."57

U.S. officials have recognized the contributions that PMF volunteers have made to Iraq's fight against the Islamic State; they also remain wary of Iran-linked elements of the PMF that the U.S. government believes operate as Iranian proxy forces outside formal Iraqi government and military control.58 U.S. officials accuse some PMF personnel of leading and participating in attacks on protestors since October 2019 and of other human rights abuses (see textbox). U.S. policy seeks to support the long-term development of Iraq's military, counterterrorism, and police services as alternatives to the continued use of PMF units to secure Iraq's borders, communities, and territory recaptured from the Islamic State.

|

Iraq, Iran, and U.S. Sanctions

In January 2020, the U.S. government designated the Iran-aligned Iraqi militia Asa'ib Ahl al Haq (AAH) as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, and named two of its leaders, Qais and Laith al Khazali, as Specially Designated Global Terrorists. In December 2019, the U.S. government designated the Khazalis for Global Magnitsky human rights-related sanctions. According to the U.S. Treasury Department, "during the late 2019 protests in many cities in Iraq, AAH has opened fire on and killed protesters."59 The U.S. government similarly designated for human rights sanctions Husayn Falih 'Aziz (aka Abu Zaynab) Al Lami, the security director for the PMF.60 According to the human rights designation notices, Qais al Khazali and Al Lami were "part of a committee of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF) proxies that approved the use of lethal violence against protesters for the purpose of public intimidation." Earlier in 2019, the U.S. government listed Harakat Hezbollah al Nujaba and its leader, Akram al Kabi, as specially designated global terrorists, and designated the commanders of the PMF 30th and 50th brigades for Global Magnitsky sanctions.

Broad U.S. efforts to put pressure on Iran extend to the Iraqi energy sector, where years of sanctions, conflict, neglect, and mismanagement have left Iraq dependent on purchases of natural gas and electricity from its Iranian neighbors.61 Since 2018, Iraqi leaders have sought relief from U.S. sanctions on related transactions with Iran. The Trump Administration has renewed repeated temporary permissions for Iraq to continue these transactions, and ongoing U.S. initiatives encourage Iraq to diversify its energy ties with its neighbors and develop more independence for its energy sector. U.S. officials promote U.S. companies as potential partners for Iraq through the expansion of domestic electricity generation capacity and the introduction of technology to capture the large amounts of natural gas that are currently flared (burned at wellheads). As of January 2020, related contracts with U.S. firms have not been finalized.

|

|

Figure 5. Select Iraqi Shia Political Groups, Leaders, and Militias

|

|

|

In general, the popularity of the PMF and broadly expressed popular respect for the sacrifices made by individual volunteers in the fight against the Islamic State have created vexing political questions for Iraqi leaders. These issues are complicated further by the apparent involvement of PMF fighters in human rights abuses and attacks on foreign military forces present in Iraq at the invitation of the Iraqi government. Iraqi law does not call for or foresee the dismantling of the PMC/PMF structure, and proposals to the contrary appear to be politically untenable at present. Given the ongoing role PMF units are playing in security operations against remnants of the Islamic State in some areas, rapid, wholesale redeployments or demobilization of PMF units might create new opportunities for IS fighters to exploit in areas where replacement forces are not immediately available. That said, U.S. military officials predicted in early 2019 that "competition over areas to operate and influence between the PMF and the ISF will likely result in violence, abuse, and tension in areas where both entities operate."62

The Kurdistan Region and Relations with Baghdad

|

Kurdistan Region Legislative Election

Seats won by Coalition/Party

|

Coalition/Party

|

Seats Won

|

|

Kurdistan Democratic Party

|

45

|

|

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan

|

21

|

|

Gorran (Change) Movement

|

12

|

|

New Generation

|

8

|

|

Komal

|

7

|

|

Reform List

[Kurdistan Islamic Union (KIU)-Islamic Movement of Kurdistan (IMK)]

|

5

|

|

Azadi List

(Communist Party)

|

1

|

|

Modern Coalition

|

1

|

|

Turkmen Parties

|

5

|

|

Christian Parties

|

5

|

|

Armenian Independent

|

1

|

Source: Kurdistan Region Electoral Commission.

|

The Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq (KRI) enjoys considerable administrative autonomy under the terms of Iraq's 2005 federal constitution, but issues concerning territory, security, energy, and revenue sharing continue to strain ties between the Kurdistan Regional Government and the national government in Baghdad. In September 2017, the KRG held a controversial advisory referendum on independence, amplifying political tensions with the national government (see textbox below).63 The referendum was followed by a security crisis as Iraqi Security Forces and PMF fighters reentered some disputed territories that had been held by KRG peshmerga forces. Peshmerga fighters also withdrew from the city of Kirkuk and much of the governorate. Baghdad and the KRG have since agreed on a number of issues, including border and customs controls, but have differed over the export of oil from some KRG-controlled fields and the transfer of funds to pay the salaries of some KRG civil servants. While talks have continued, the ISF and peshmerga have remained deployed across from each other at various fronts throughout the disputed territories (Figure 6).

The KRG delayed overdue legislative elections for the Kurdistan National Assembly in the wake of the referendum crisis and held them on September 30, 2018. Kurdish leaders have since been engaged in regional government formation talks while also participating in cabinet formation and budget negotiations at the national level. The KDP won a plurality (45) of the 111 KNA seats in the September 2018 election, with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and smaller opposition and Islamist parties splitting the balance. With longtime KDP leader Masoud Barzani's term as president having expired in 2015, his nephew, KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani succeeded him in June 2019. Masoud Barzani's son, security official Masrour Barzani, assumed the KRG prime ministership.

After the election, factions within the PUK appeared to have differences of opinion over KRG cabinet formation, while KDP and PUK differences were apparent at the national level. During government formation talks in Baghdad, the KDP sought to name the Kurdish candidate for the Iraqi national presidency, but a majority of COR members instead chose Barham Salih, a PUK member. In March 2019, KDP and PUK leaders announced a four-year political agreement providing for the formation of a new KRG government and setting joint positions on candidates for the Iraqi national Minister of Justice position and governorship of Kirkuk.64

Prior to Prime Minister Abd al Mahdi's resignation announcement, KRG leaders reportedly planned to visit Baghdad to finalize an agreement over the export of 250,000 barrels per day of oil from the Kurdistan region under the national government's marketing authority.65 In exchange, Baghdad was to continue to make budget transfers in 2020 that pay KRG salaries. Disagreement over this issue has lingered throughout 2019 in light of the KRG's reported failure to comply with previously agreed export arrangements. Negotiations over exports and financial transfers may shape Kurdish leaders' positions with regard to the formation of a caretaker government and the eventual formation of a new government after future national elections. Since October 2019, Kurdish leaders have recognized Arab Iraqi protestors' concerns and criticized repressive violence, while convening to unify positions on reforms that some Kurds fear could undermine the federally recognized Kurdistan region's rights under Iraq's constitution.66

U.S. officials have encouraged Kurds and other Iraqis to engage on issues of dispute and to avoid unilateral military actions. U.S. officials encourage improved security cooperation between the KRG and Baghdad, especially since IS remnants appear to be exploiting gaps created by the standoff in the disputed territories. KRG officials continue to express concern about the potential for an IS resurgence and chafe at operations by some PMF units in areas adjacent to the KRI.

|

The Kurdistan Region's September 2017 Referendum on Independence

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held an official advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017, despite requests from the national government of Iraq, the United States, and other external actors to delay or cancel it. More than 72% of eligible voters participated and roughly 92% voted "Yes." The referendum was held across the KRI and in other areas that were then under the control of Kurdish forces. These include areas subject to territorial disputes between the KRG and the national government, such as the multiethnic city of Kirkuk, adjacent oil-rich areas, and parts of Ninewa governorate populated by religious and ethnic minorities. Kurdish forces had secured many of these areas following the retreat of national government forces in the face of the Islamic State's rapid advance across northern Iraq in 2014.

After the referendum, Iraqi national government leaders imposed a ban on international flights to and from the Kurdistan region. In October 2017, Prime Minister Abadi ordered Iraqi forces to return to the disputed territories that had been under the control of national forces prior to the Islamic State's 2014 advance. Much of the oil-rich governorate of Kirkuk—long claimed by Iraqi Kurds—returned to national government control, and resulting controversies have riven Kurdish politics. Iraqi authorities rescinded the international flight ban in 2018 after agreeing on border control, customs, and security at Kurdistan's international airports.

|

|

Figure 6. Disputed Territories in Iraq

Areas of Influence as of December 17, 2018

|

|

|

Sources: Congressional Research Service using ArcGIS, IHS Markit Conflict Monitor, U.S. government, and United Nations data.

|

Humanitarian Issues and Stabilization

Humanitarian Conditions

U.N. officials report several issues of ongoing humanitarian and protection concerns for displaced and returning populations and the host communities assisting them. With a range of needs and vulnerabilities, these populations require different forms of support, from immediate humanitarian assistance to resources for early recovery. Protection is a key priority in areas of displacement, where for example, harassment of displaced persons by armed actors and threats of forced return have occurred, as well as in areas of return. By December 2017, more Iraqis had returned to their home areas than those who had remained as internally displaced persons (IDPs) or who were becoming newly displaced. Nevertheless, humanitarian conditions remain difficult in many conflict-affected areas of Iraq. In November 2019, the U.N. Secretary General reported to the Security Council and emphasized that returns of internally displaced persons to their districts of origin should be "informed, safe, dignified, and voluntary."67

As of October 31, 2019, more than 4.4 million Iraqis displaced after 2014 had returned to their districts, while more than 1.4 million individuals remained as displaced persons.68 Ninewa governorate hosts the most IDPs of any single governorate (nearly one-third of the total), reflecting the lingering effects of the intense military operations against the Islamic State in Mosul and other areas during 2017 (Table 2). Estimates suggest thousands of civilians were killed or wounded during the Mosul battle, which displaced more than 1 million people.

IOM estimates that the Kurdistan region hosts more than 700,000 IDPs (approximately 50% of the estimated 1.4 million remaining IDPs nationwide). IDP numbers in the KRI have declined since 2017, though not as rapidly as in some other governorates.

The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) 2020 humanitarian needs assessment anticipates that as many as 4.1 million Iraqis will need of some form of humanitarian assistance in 2020. The 2019 Iraq Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) sought $701 million and as of January 2020, the appeal had received $641 million, with an additional $303 million received outside the plan.69 The United States was the top donor to the 2018 and 2019 Iraq HRPs. Since 2014, the United States has contributed nearly $2.7 billion to humanitarian relief efforts in Iraq, including more than $470 million in humanitarian support in FY2019.70

Table 2. IOM Estimates of IDPs by Location in Iraq

As of October 31, 2019, Select Governorates

|

IOM Estimates of IDPs by Location of Displacement

|

% Change since 2017

|

|

Governorate

|

January 2017

|

January 2018

|

October 2019

|

|

|

Suleimaniyah

|

153,816

|

188,142

|

140,832

|

-8%

|

|

Erbil

|

346,080

|

253,116

|

244,440

|

-29%

|

|

Dohuk

|

397,014

|

362,670

|

319,722

|

-19%

|

|

KRI Total

|

896,910

|

806,976

|

704,994

|

-21%

|

|

Ninewa

|

409,020

|

795,360

|

353,340

|

-14%

|

|

Salah al Din

|

315,876

|

241,404

|

85,398

|

-73%

|

|

Baghdad

|

393,066

|

176,700

|

44,598

|

-89%

|

|

Kirkuk

|

367,188

|

172,854

|

101,082

|

-72%

|

|

Anbar

|

268,428

|

108,894

|

30,222

|

-89%

|

|

Diyala

|

75,624

|

81,972

|

53,892

|

-29%

|

Source: International Organization for Migration (IOM), Iraq Displacement Tracking Monitor Data.

Stabilization and Reconstruction

U.S. stabilization assistance to areas of Iraq that have been liberated from the Islamic State is directed through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)-administered Funding Facility for Stabilization (FFS) and through other channels.71 According to UNDP data, the FFS has received $1.19 billion in resources since its inception in mid-2015, with nearly 2,200 projects reported completed with the support of UNDP-managed funding.72

In January 2019, UNDP identified $426 million in stabilization program funding shortfalls in five priority areas in Ninewa, Anbar, and Salah al Din governorates "deemed to be the most at risk to future conflict" and "integral for the broader stabilization of Iraq."73 By December 2019, that funding gap had narrowed to $265 million.74 The UNDP points to unexploded ordnance, customs clearance delays, and the growth in volume and scope of FFS projects as challenges to its ongoing work.75

At a February 2018 reconstruction conference in Kuwait, Iraqi authorities described more than $88 billion in short- and medium-term reconstruction needs, spanning various sectors and different areas of the country.76 Countries participating in the conference offered approximately $30 billion worth of loans, investment pledges, export credit arrangements, and grants in response. The Trump Administration actively supported the participation of U.S. companies in the conference and announced its intent to pursue $3 billion in Export-Import Bank support for Iraq.

Iraqi leaders hope to attract considerable private sector investment to help finance Iraq's reconstruction needs and underwrite a new economic chapter for the country. The size of Iraq's internal market and its advantages as a low-cost energy producer with identified infrastructure investment needs help make it attractive to investors. Overcoming persistent concerns about security, service reliability, and corruption, however, may prove challenging. Foreign firms active in Iraq's oil sector evacuated some foreign personnel during U.S.-Iran confrontations in December 2019 and January 2020. The security situation, Iraqi government's ongoing response to the demands of protestors, and the success or failure of new authorities in pursuing reforms may provide key signals to parties exploring investment opportunities.

Economic and Fiscal Challenges