Introduction and Issues for Congress

The United Kingdom's (UK's) pending exit from the European Union (EU), commonly termed Brexit, remains the overwhelmingly predominant issue in UK politics. In a national referendum held in June 2016, 52% of UK voters favored leaving the EU. In March 2017, the UK officially notified the EU of its intention to leave the bloc, and the UK and the EU began negotiations on the terms of the UK's withdrawal.1 Brexit was originally scheduled to occur on March 29, 2019, but the UK Parliament was unable to agree on a way forward due to divisions over what type of Brexit the UK should pursue and challenges related to the future of the border between Northern Ireland (part of the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (an EU member state). In early 2019, Parliament repeatedly rejected the withdrawal agreement negotiated between then-Prime Minister Theresa May's government and the EU, while also indicating opposition to a no-deal scenario, in which the UK would exit the EU without a negotiated withdrawal agreement. Amid this impasse, in April 2019, EU leaders agreed to grant the UK an extension until October 31, 2019.2

On October 17, 2019, negotiators from the EU and the government of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson concluded a new withdrawal agreement, but Johnson encountered challenges in securing the UK Parliament's approval of the deal. The EU granted the UK another extension until January 31, 2020, while Parliament set an early general election for December 12, 2019. Johnson's Conservative Party scored a decisive victory in the election, winning 365 out of 650 seats in the UK House of Commons. The result provides Prime Minister Johnson with a mandate to proceed with his preferred plans for Brexit. The UK is expected to ratify the withdrawal agreement, allowing it to withdraw from the EU by the January 31, 2020, deadline.

Many Members of Congress have a broad interest in Brexit. Brexit-related developments are likely to have implications for the global economy, U.S.-UK and U.S.-EU political and economic relations, and transatlantic cooperation on foreign policy and security issues.

In 2018, the Administration notified Congress of its intent to launch U.S.-UK trade agreement negotiations after the UK leaves the EU, and Congress may consider how Brexit developments affect the prospects for an agreement.3 Congress would likely need to pass legislation to implement the potential free trade agreement (FTA) before it could enter into force, particularly if it were a comprehensive FTA. U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has said that trade negotiations with the UK are a "priority" and will start as soon as the UK is in a position to negotiate, but he cautioned that the negotiations may take time.4

Some Members of Congress also have demonstrated an interest in how Brexit might affect Northern Ireland.5 In April 2019, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said there would be "no chance whatsoever" for a U.S.-UK trade agreement if Brexit were to weaken the Northern Ireland peace process.6 On October 22, 2019, the House Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment held a hearing titled "Protecting the Good Friday Agreement from Brexit." Other Members of Congress, including Senate Finance Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, have expressed support for the UK and a bilateral trade agreement post-Brexit and have not conditioned such support on protecting Northern Ireland.7

Brexit Status Overview and Update

The December 2019 election resolved a political deadlock that dominated UK politics for three and a half years. Unable to break the stalemate over Brexit in Parliament, Prime Minister Theresa May resigned as leader of the Conservative Party on June 7, 2019. Boris Johnson became prime minister on July 24, 2019, after winning the resulting Conservative Party leadership contest.8 Seen as a colorful and polarizing figure who was one of the leading voices in the campaign for the UK to leave the EU, Johnson previously served as UK foreign secretary in the May government from 2016 to 2018 and mayor of London from 2008 to 2016. He inherited a government in which, at the time, the Conservative Party held a one-seat parliamentary majority by virtue of support from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the largest unionist party in Northern Ireland, which strongly supports Northern Ireland's continued integration as part of the UK.

After taking office, Prime Minister Johnson announced that he intended to negotiate a new deal with the EU that discarded the contentious Northern Ireland backstop provision that would have kept the UK in the EU customs union until the two sides agreed on their future trade relationship.9 The backstop was intended to prevent a hard border with customs and security checks on the island of Ireland and to ensure that Brexit would not compromise the rules of the EU single market (see Appendix A, which reviews the backstop and the rejected withdrawal deal). Although Prime Minister Johnson asserted that he did not desire a hard land border, he strongly opposed the backstop arrangement. Like many Members of Parliament both within and outside the Conservative Party, Johnson viewed the backstop as potentially curbing the UK's sovereignty and limiting its ability to conclude free trade deals. Given initial skepticism about the chances for renegotiating the withdrawal agreement with the EU, the Johnson government began to ramp up preparations for a possible no-deal Brexit.10

In September 2019, Parliament passed legislation requiring the government to request a three-month deadline extension (through January 31, 2020) from the EU on October 19, 2019, unless the government had reached an agreement with the EU that Parliament had approved or received Parliament's approval to leave the EU without a withdrawal agreement.11 The government also lost its parliamentary majority in September 2019, with the defection of one Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) to the Liberal Democrats and the expulsion from the party of 21 Conservative MPs (10 of the 21 were later reinstated) who worked with the opposition parties to limit the government's ability to pursue a no-deal Brexit. Prime Minister Johnson subsequently sought to trigger an early general election, to take place before the October 31 Brexit deadline, but fell short of the needed two-thirds majority in Parliament to support the motion.12

The New Withdrawal Agreement

On October 17, 2019, the European Council (the leaders of the EU27 countries) endorsed a new withdrawal agreement that negotiators from the European Commission and the UK government had reached earlier that day.13 The new agreement replicates most of the main elements from the original agreement reached in November 2018 between the EU and the government of then-Prime Minister Theresa May, including guarantees pertaining to citizens' rights, UK financial commitments to the EU, and a transition period lasting through 2020 (see Appendix A).

The main difference in the new withdrawal agreement compared to the November 2018 original is in the documents' respective Protocols on Ireland/Northern Ireland (i.e., the backstop). Under the new withdrawal agreement, Northern Ireland would remain legally in the UK customs territory but practically in the EU customs union, which essentially will create a customs border in the Irish Sea. Main elements of the new protocol include the following:

- Northern Ireland remains aligned with EU regulatory rules, thereby creating an all-island regulatory zone on the island of Ireland and eliminating the need for regulatory checks on trade in goods between Northern Ireland and Ireland;

- any physical checks necessary to ensure customs compliance are to be conducted at ports or points of entry away from the Northern Ireland-Ireland border, with no checks or infrastructure at this border;

- four years after the arrangement comes into force, the Northern Ireland Executive and Assembly must consent to renew it (this vote presumably would take place in late 2024 after the arrangement takes effect at the end of the transition period in December 2020);

- at the end of the transition period (the end of 2020), the entire UK, including Northern Ireland, will leave the EU customs union and conduct its own national trade policy.

The changes were largely based on a proposal sent by Prime Minister Johnson to then-European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and facilitated by Johnson's subsequent discussions with Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar.14 Some analysts suggest the changes also resemble in part the "Northern Ireland-only backstop" initially proposed by the EU in early 2018. In the original agreement, the backstop provision was ultimately extended to the entire UK after Prime Minister May backed the DUP's adamant rejection of a Northern Ireland-only provision, which the DUP contended would create a regulatory barrier in the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK and thus would threaten the UK's constitutional integrity.15 The DUP also opposes the provisions for Northern Ireland in Johnson's renegotiated withdrawal agreement, especially the customs border in the Irish Sea, for similar reasons.

Extension Through January 2020

Prime Minister Johnson hoped to hold a yes or no vote on the renegotiated withdrawal agreement by the extension deadline of October 19, but Parliament decided to delay the vote until it had passed the legislation necessary for implementing Brexit and giving legal effect to the withdrawal agreement and transition period (the Withdrawal Agreement Bill).

Prime Minister Johnson had repeatedly asserted strong opposition to requesting another extension from the EU.16 As noted above, however, UK law required the government to request another extension from the EU on October 19, 2019, unless the UK and EU had reached a new withdrawal agreement and Parliament had approved that agreement or the UK government received Parliament's approval to leave the EU without a withdrawal agreement.

Johnson accordingly sent the EU an unsigned request for an extension through January 2020 with a cover letter from the UK ambassador to the EU stating that the request was made in order to comply with UK law. Johnson also included a personal letter to then-European Council President Donald Tusk reiterating Johnson's view that a further extension would damage UK and EU interests and the UK-EU relationship.17 The EU granted the request on October 28, 2019 and extended the Brexit deadline until January 31, 2020.

December 2019 Election

On October 29, 2019, Parliament agreed to set an early general election for December 12, 2019. Some commentators argued that since Prime Minister Johnson won the Conservative leadership contest in July 2019, his highest priority had been to spark a general election that returned him as prime minister. Many observers came to view a general election that produced a clear outcome as the best way to break the political deadlock over Brexit and provide a new mandate for the winner to pursue Brexit plans.

With Brexit the defining issue of the campaign, the Conservative party won a decisive victory, winning 365 out of 650 seats in the House of Commons, an increase of 47 seats compared to the 2017 election (see Table 1). The opposition Labour Party, unable to present a clear alternative vision of Brexit to the electorate, and unable to gain sufficient traction with voters on issues beyond Brexit, suffered a substantial defeat with the loss of 59 seats.18 The Scottish National Party gained 13 seats to hold 48 of the 59 constituencies in Scotland, likely indicating a resurgence of the pro-independence movement in Scotland, where more than 60% of 2016 referendum voters had supported remaining in the EU.19

|

Party |

# of Seats |

Net # of Seats +/– |

% of Vote |

|

Conservatives |

365 |

+47 |

43.6% |

|

Labour |

203 |

-59 |

32.2% |

|

Scottish National Party |

48 |

+13 |

3.9% |

|

Liberal Democrats |

11 |

-1 |

11.5% |

|

Democratic Unionist Party |

8 |

-2 |

0.8% |

|

All Others |

15 |

+2 |

7.9% |

Source: "UK Results: Conservatives Win Majority," BBC News, at https://www.bbc.com/news/election/2019/results.

Implications of the Election Outcome for Brexit

The election outcome puts the UK on course to withdraw as a member of the EU by January 31, 2020. After the election, the UK government introduced a revised Withdrawal Agreement Bill and began moving it through the House of Commons.20 Once the legislation is adopted, the UK government will be able to proceed with ratifying the withdrawal agreement.21 The European Parliament must vote on the agreement for the EU to complete ratification on its side.

Should the UK exit the EU on January 31, 2020, an 11-month transition period would begin, during which the UK would continue to follow all EU rules and remain a member of the EU single market and customs union. The withdrawal agreement allows for a one- or two-year extension of the transition period, but Prime Minister Johnson has strongly opposed the idea of an extension and inserted language in the Withdrawal Agreement Bill that the transition period will conclude at the end of 2020 without an extension.22

The UK would seek to begin negotiations on an FTA with the EU, with the aim of concluding an agreement by the end of the transition period. Should the transition period end without a UK-EU FTA or other agreement on the future economic relationship, UK-EU trade and economic relations would be governed by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules (see "Scenarios for UK-EU Trade Relationship Post-Brexit," below). Such an outcome could resemble many aspects of a no-deal Brexit (see "No-Deal Brexit" text box below).

Beyond trade, negotiations on the future UK-EU relationship are expected to seek a comprehensive partnership covering issues including security, foreign policy, energy, and data sharing. Negotiations are also expected to address the numerous other areas related to the broader economic relationship, such as financial services regulation, environmental and social standards, transportation, and aviation. Officials and analysts have expressed doubts that such comprehensive negotiations can be concluded within 11 months.23 The two sides could temporarily address some areas, such as road transportation and aviation, through side deals granting interim provisions.

The revised protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland would come into effect with ratification of the withdrawal agreement, and its provisions would begin to apply at the end of the transition period. Observers have questioned how exactly the revised protocol will be implemented, including where and how customs checks will take place.24 Such issues are to be decided by the Joint Committee (of UK and EU officials) during the transition period. Implementation is likely to remain a work in progress. Both parties seek to protect the Good Friday Agreement, while the EU seeks to safeguard its single market and the UK seeks to preserve its constitutional integrity.

|

No-Deal Brexit Both UK and EU officials sought to avoid a no-deal Brexit scenario, in which the UK would exit the EU without a negotiated withdrawal agreement, although both sides developed contingency plans for such an outcome. Many assessments of the potential impact of a no-deal scenario concluded that a no-deal Brexit could cause considerable disruption, with negative effects on the economy, trade, security, Northern Ireland, and other issues. In September 2019, a parliamentary motion forced the UK government to publish a secret document outlining its planning assumptions for a no-deal Brexit. Among other possibilities, the document discussed border delays for travelers and transport services; a potential decrease in the availability of certain types of fresh food; price increases for food, fuel, and electricity; disruption in the supply of medicines and medical supplies; and a potential rise in public disorder and community tensions. Government officials stressed that the document represented "reasonable worst case planning assumptions" rather than a base scenario. Some Brexit advocates maintained that fears over a no-deal Brexit were exaggerated, and some ardent Brexit supporters argued that a no-deal Brexit would be preferable to a soft Brexit, in which the UK would retain certain ties and obligations to the EU. Some analysts have argued that there is no such thing as a clean break with the EU. Even in a no-deal Brexit scenario, the UK would likely immediately find itself continuing negotiations with the EU in pursuit of mini-deals seeking to mitigate disruption. In such a scenario, the EU would likely insist the UK agree to many of the terms of the withdrawal agreement as the price of securing such deals and establishing a framework for the long-term UK-EU relationship. Sources: Cabinet Office, Government Response to Humble Address Motion, September 11, 2019, The UK in a Changing Europe, No Deal Brexit: Issues, Impacts, Implications, September 4, 2019, John Springford, How Would Negotiations After a No-Deal Brexit Play Out?, Centre for European Reform, September 3, 2019, "UK's Hammond attacks 'Terrifying' Views of Brexiteer Rees-Mogg," Reuters, July 17, 2019. |

Brexit and Trade

Current UK-EU Trade Relationship

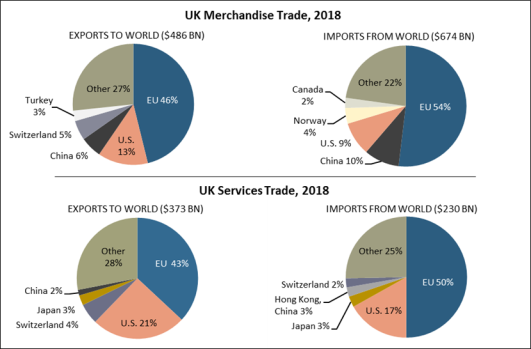

Brexit casts great uncertainty over the future UK-EU trade relationship. At 15% of the EU gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, the UK is the EU's second-largest economy after Germany (21%). The EU, as a bloc, is the UK's largest trading partner (see Figure 1). While UK trade with other countries, such as China, has risen in recent years, the EU remains the UK's most consequential trading partner.25 UK-EU trade is highly integrated through supply chains and trade in services, as well as through foreign affiliate activity of EU and UK multinational companies. Within the EU, the largest goods and services trading partners for the UK are Germany, the Netherlands, France, Ireland, and Spain.26 (See "Implications for U.S.-UK Relations" section for discussion of U.S.-UK trade.)

As a member of the EU, the UK's trade policy is determined by the EU, which has exclusive competence for trade policy for EU member states. The UK, as an EU member, is in the EU customs union; this makes trade in goods between the UK and other EU member tariff-free, and binds the UK to the EU's common external tariff, which the UK and other EU member states apply to goods imported from outside the customs union.

The UK also is a part of over 40 preferential trade agreements that the EU has with about 70 countries, as well as part of ongoing EU trade negotiations.27 Thus, until Brexit occurs, the UK is a part of the trade negotiations between the EU and the United States currently taking place under the Trump Administration.28

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service, (CRS), based on data from the World Trade Organization (WTO), Trade Profiles 2019. |

The UK also is part of the EU single market. In addition to providing for the free movement of goods, the single market provides for free movement of services, capital, and people, and is underpinned by common rules, regulations, and standards that aim to reduce and eliminate nontariff barriers. Such barriers may stem, for instance, from diverging or duplicative production standards, labeling rules, and licensing requirements. Goods move freely in the single market, tariff-free, and generally are not subject to customs procedures.

A product imported into the UK currently faces the common external tariff; once inside the UK, the product does not face additional tariffs regardless of its origin if exported to another EU member state. The single market provides businesses inside the EU with the ability to sell goods and services across the EU more freely. The single market is more developed for goods than for services, but it still offers some significant market access for services. For instance, under the single market, banks and other financial services firms that are established and authorized in the UK can apply for the right to provide certain defined services throughout the EU or to open branches in other countries with relatively few additional requirements (known as passporting rights). Among other things, UK professionals also can move freely in the EU, benefitting from mutual recognition of professional qualifications across EU member states.

Scenarios for UK-EU Trade Relationship Post-Brexit

|

United Kingdom, European Union, and the World Trade Organization The United Kingdom (UK) is a founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and it is a WTO member both on an individual basis and as a member of the European Union (EU). However, the UK does not have its own schedule of commitments in the WTO; rather, its commitments to other WTO members presently are through the EU's schedule of commitments. The schedule of commitments refers to the commitments that WTO members make to all other WTO members on the nondiscriminatory market access (i.e., "most-favored-nation," or MFN, access) they will provide for trade in goods, services, agriculture, and government procurement. These commitments govern trading relationships among WTO members unless they have preferential trading arrangements. WTO terms of trade for the UK and, to some extent, the EU would have to be renegotiated as a result of Brexit (see "Global Britain" section for further discussion). |

Following the December 2019 election, the default scenario appears to be that the UK would seek to negotiate an FTA with the EU after ceasing to be a member on January 31, 2020. Whether or not an FTA had been concluded, the UK would no longer be part of the EU single market and customs union at the end of the ensuing transition period, currently expected to last to the end of 2020.

No Customs Union

If the UK is no longer part of the EU customs union, it would regain control over its national trade policy and be free to negotiate its own free trade agreements with other countries, a key rationale for many Brexit supporters.

If the post-Brexit transition period ends without the conclusion of a trade deal with the EU, the UK would no longer have preferential access to the EU market and World Trade Organization (WTO) terms would govern the UK-EU trade relationship (see "United Kingdom, European Union, and the World Trade Organization" text box).29 Trade between the UK and the EU would no longer be tariff-free, and nontariff barriers such as new customs procedures also would arise, adding costs to doing business.

Free Trade Agreement?

The political declaration attached to the revised withdrawal agreement envisions "an ambitious, broad, deep, and flexible partnership across trade and economic cooperation with a comprehensive and balanced Free Trade Agreement at its core."30 The Johnson government seeks to negotiate a "best in class" trade deal with the EU. It remains to be seen if a potential deal will focus primarily on trade in goods or will also extend to other sectors and issues, such as agriculture, services, data flows, and intellectual property rights. EU Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan has stated that the EU will "require solid guarantees of a level playing field in relation to state aid, labour and environmental protections, and taxation agreements. The level of ambition of any future free trade agreement is entirely dependent on adequate protection of the EU single market."31 The UK, however, may seek to diverge from EU rules and regulations, allowing for more flexibility in its trade negotiations with the United States and other countries.

Whatever its contours, no UK trade agreement with the EU likely would be able to replicate existing single market access. For instance, the EU bilateral FTAs with Canada and Japan eliminate most tariffs but have a number of exceptions, such as in services. EU FTAs have varied in their scope of trade liberalization and rules-setting. The EU has said that the UK cannot have a better trade relationship with the EU outside of the single market than within it.

The Johnson government aims to start negotiating a trade deal with the EU as soon as the UK withdraws from the EU and to conclude that deal by the end of the transition period—currently anticipated to be a span of 11 months. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said that the timetable was "extremely challenging" and negotiators would do their best in the "very little time" available.32 EU officials have warned that the time frame will constrain the scope of the talks.

Many analysts are skeptical that an ambitious trade agreement can be negotiated and approved by the EU and UK governments within 11 months. Some past EU trade agreement negotiations have been lengthy. For instance, EU negotiations with Canada and Japan took, respectively, seven and four years.

Soft Brexit Options Diminished

Advocates of a soft Brexit argue that the UK should maintain close economic and trade ties with the EU by remaining a member of the EU customs union or developing another customs arrangement with the EU. To do so, however, means that the UK would not regain control over its trade policy. Under the renegotiated withdrawal agreement, the UK is expected leave the EU customs union at the end of the transition period, and the result of the December 2019 UK general election makes a future customs union arrangement between the UK and the EU unlikely. The Johnson government opposes any form of soft Brexit, given that such models would force the UK to abide by EU rules and regulations and limit the UK's ability to conduct an independent trade policy.

Turkey is an example of a non-EU country in a customs union relationship with the EU. Its trading relationship with the EU has similarities and differences to those of Norway and Switzerland, which also are non-EU countries that are not in the customs union but have tariff-free access to the EU (with some exclusions, such as on agriculture and fisheries for Norway and on some services for Switzerland).33 Like Norway and Switzerland, Turkey has no voice on EU decisions; unlike Norway and Switzerland, Turkey does not contribute to the EU budget. Turkey-EU trade is tariff-free on covered products (most goods and processed agricultural products). Turkey has adopted the EU common external tariff and must apply tariff reductions that the EU negotiates with other countries. Preferential access that the EU gains to these other countries, however, does not automatically apply to Turkey, which would need to negotiate its own agreements with these other countries.

If the UK were to participate in the EU customs union, it potentially could negotiate with other countries on areas outside the scope of the customs union (e.g., services, digital trade, public procurement, intellectual property, and regulatory cooperation). However, to the extent that a customs union would represent a desire for the UK to keep its trade with the EU as frictionless as possible, the UK may not wish to depart from EU regulatory and other approaches and risk introducing nontariff barriers. This stance would limit the UK's negotiating flexibility in trade negotiations with countries outside of the EU. Additionally, the EU may be unwilling to agree to a customs union arrangement without seeking regulatory commitments in order to maintain a level playing field. A customs union also could limit UK trade policy, such as by applying trade remedies or developing country preference programs.

Impact on UK Trade and Economy

The precise impact of Brexit on UK trade with the EU and the UK economy depends to a large degree on the shape of the future UK-EU relationship, and the UK's ability to conclude other new trade deals. In most scenarios, Brexit would raise the costs of UK trade with the EU through higher tariffs and nontariff barriers.34 Costs may be greater in the short term, until commercial disruptions are smoothed out. Costs may be mitigated to some degree if the two sides reach a free trade agreement, although this may take years. New trade deals signed by the UK with countries outside of the EU could boost economic growth, but they may not be by enough to offset the loss of the UK's membership in the EU single market. Some of the higher costs of commerce may be passed to consumers.

As noted earlier, WTO terms would govern UK-EU trade if the transition period were to end without an FTA. EU average most-favored-nation (MFN) tariff rates are low (around 5%) but significantly higher for certain products. Because of the tight linkages in UK-EU trade, higher tariffs would raise the costs of trade not only for final goods but also for intermediate goods traded between UK and EU member states as part of production and supply chains. UK sectors that may be particularly affected by increased tariffs include agriculture and manufacturing sectors (processed food products, apparel, leather products, and motor vehicles).35

UK importers may face higher costs, as the UK may impose its own MFN-level tariffs on imports from the EU. Presently, the UK government is considering a tariff regime where the majority (87%) of total imports into the UK by value would be eligible for tariff-free access for 12 months while the UK aims to negotiate a new tariff regime with the EU. However, tariffs would remain on other goods imported to the UK, including some meat and dairy, vehicles, ceramics, and fertilizers, in an effort to support farmers and manufacturers.36

Should the UK and EU negotiate a preferential trading arrangement, it likely would not lead to an elimination of all tariffs. In addition, exporters on both sides would have to certify the origin of their traded goods in order to satisfy "rules of origin" to receive the preferential market access.37

Nontariff barriers to trade also would arise with Brexit. Brexit would make the UK a "third country" from the EU's perspective, and the UK's regulatory frameworks—although currently aligned with those of the EU—would no longer be recognized by the EU. The EU would have to make determinations on whether measures of the UK comply with the corresponding EU regulatory framework. Some observers question the extent to which the Johnson government would be willing to maintain regulatory alignment with the EU post-Brexit, and this issue is expected to pose a key challenge in negotiations with the EU on future trade relations.

New administrative and customs procedures would apply to UK-EU trade. UK trade with the EU could face new licensing requirements, testing requirements, customs controls, and marketing authorizations. For instance, by some estimates, delays caused by customs checks of trucks from the EU could cause a 17-mile queue at the Port of Dover.38 Such potential backlogs have raised concerns about spoiling or shortage of foods and medicines and complications for industries that depend on "just-in-time" productions such as autos.

Many businesses in the UK have been preparing for Brexit through such measures as stockpiling inventories, adjusting contract terms, restructuring operations, and shifting assets abroad. Some companies, particularly smaller companies, may not be as equipped as their larger competitors to deal with the transition. UK businesses also remain concerned about the potential effects of a no-deal scenario should the UK and EU fail to reach agreement on a future trade relationship by the end of 2020 without an extension of the transition period.

Certain sectors of the UK economy may be particularly affected by Brexit.39 Examples include the following:

- Autos. The EU is the UK's largest trading partner for motor vehicles, accounting for 43% of UK exports and 83% of UK imports in these products in 2018.40 The EU also comprises the majority of UK trade in auto component parts and accessories. The UK automobile sector thrives on the sort of "just-in-time production" that depends on a free flow of trade in component parts.41 If a no-deal scenario unfolded at the end of the transition period, UK auto exports to the EU would face a 10% tariff. Autos are a highly regulated industry, and UK and EU exporters would face new checks for safety and quality standards to obtain approval in the other's market.

- Chemicals. About 60% of UK chemicals exports are to the EU, and about 73% of UK chemicals imports are from the EU.42 Chemicals trade in the single market is governed by a European Economic Area (EEA) regulatory framework known as REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals Regulation).43 Post-Brexit, UK chemicals exports to the EU could face tariffs of up to 6.5% in the absence of a preferential trade arrangement with the EU. Without a deal, UK chemicals registrations under REACH would become void with Brexit and UK companies would have to transfer their registrations to an EEA-based subsidiary or representative to maintain market access. The UK also would need to set up its own regulatory regime for chemicals.44

- Financial Services. London is the largest financial center in Europe presently. Financial services and insurance make up about one-third of UK services exports to the EU.45 The EU has made clear that the UK will no longer be able to benefit from financial passporting after Brexit. Absent alternative arrangements, such as an equivalence decision by the EU, continued trade in financial services may require UK and EU businesses to restructure their operations.46 U.S. and other banks are concerned about losing the ability to use their UK bases to access EU markets without establishing legally separate subsidiaries. Some financial institutions, such as Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, Morgan Stanley, and Citigroup, have shifted (or plan to shift) some jobs and assets from London to other European cities, such as Amsterdam, Dublin, Frankfurt, and Paris.47 By one estimate, financial companies have already committed to moving over £1 trillion in assets from the UK to other parts of the EU as part of Brexit contingency planning.48

- Business Services. The EU is the largest export market for a range of UK business services (legal, accounting, advertising, research and development, architectural, engineering, and other professional and technical services)—accounting for 39% of these exports from the UK.49 Determinations of professional certification qualifications may need to be made.

- Data Flows. Presently, data flows freely between the UK and other EU member states, underpinning much of UK-EU services trade.50 If the UK is outside of the EU, the EU would no longer recognize the UK's personal data protection regime. Through a process known as an adequacy decision, the EU would have to determine whether the UK's standards for protecting personal data meet EU standards under the EU General Data Protection Regulation.51 The potential blockage of data transfers could have serious implications for UK companies seeking to transfer personal data out of the EU—including not only technology companies but also health care companies and other service providers.52

|

Economic Impact of Brexit In 2016, after the Brexit referendum, the British pound fell to a record low and concerns emerged about widespread harm to the UK economy. Doomsday fears may have abated, but prolonged uncertainty over Brexit appears to be a drag on the UK economy. In 2018, the UK economy saw its lowest annual growth rate (1.4%) since 2012. Surveys of businesses indicate that the uncertainty over Brexit has caused them to scale back investments, which, in turn, has affected their productivity. Various studies have sought to estimate Brexit's impact on the UK economy. These studies use different methodologies and make different assumptions about Brexit outcomes. Estimates vary, but most studies project that the UK will be economically worse off due to Brexit, with the most negative consequences from a no-deal Brexit. The Bank of England, in September 2019, estimated that the UK economy will shrink by 5.5% in a no-deal Brexit. In contrast, its November 2018 analysis predicted a decline of 8% for the UK economy if there is a no-deal Brexit. The changed assessment reflects ongoing UK government and business preparations for a possible no-deal Brexit. A softening global economy adds to downside risks of Brexit. The Peterson Institute for International Economics analyzed 12 studies on the medium- to long-term impacts of Brexit. In most of the studies analyzed, the UK gross domestic product (GDP) loss from a hard Brexit (a return to World Trade Organization terms of trade) would range from 1.2% to 4.5%, whereas GDP loss from a soft Brexit (e.g., the "Norway model" of access to the EU single market in return for following most EU rules and laws) would be roughly half of the negative impact of a hard Brexit. Most of the studies analyzed also found that Brexit would be more harmful for the UK than the EU. Given its relatively larger size, the EU may be able to offset trade losses from Brexit through trade among the remaining the 27 member states, as well as trade with countries outside of the EU. One Peterson study examined additional factors and estimated that GDP in the UK would decline by 1.23% from a soft Brexit and 2.53% from a hard Brexit, whereas for the EU-27, GDP would decline by 0.16% from a soft Brexit and 0.35% from a hard Brexit. Sources: Nicholas Bloom et al., The Impact of Brexit on UK Firms, Bank of England, Staff Working Paper, August 2019. Deloitte, "Deloitte CFO Survey: Political and Economic Uncertainty Compounds Brexit Fears," press release, July 8, 2019. Gemma Tetlow and Alex Stojanovic, Understanding the Economic Impact of Brexit, Institute for Government, November 2018. Letter from Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, to John Mann, MP, Interim Chair of the Treasury Committee, Parliament, September 3, 2019. Valentina Romei, "Bank of England Trims Forecast of Pain in No Deal Scenario," Financial Times, September 4, 2019. Bank of England, EU Withdrawal Scenarios and Monetary and Financial Stability, November 2018. María C. Latorre et al., Brexit: Everyone Loses, But Britain Loses the Most, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper, March 2019. |

Global Britain

For Brexit supporters, a major rationale was for the UK to regain a fully independent trade policy. What might this trade policy look like? Since the referendum, the UK government has championed a notion of "Global Britain," previously under the May government and now under the Johnson government. The idea of Global Britain promotes the UK's renewed engagement in a wide range of foreign policy and international issues, with trade a significant aspect of the broader concept; Global Britain envisages, among other things, an outward looking UK strengthening trade linkages around the world.53

If it were no longer a part of the EU customs union, the UK could negotiate trade agreements with other countries and aim to tailor those agreement to its specific interests. The UK is the world's fifth-largest economy, with a gross domestic product (GDP) of $2.8 trillion in 2018, but it may have less leverage in trade negotiations on its own compared to negotiating as part of the EU.54 As a member of the EU, the UK's negotiating leverage arguably is greater because the EU, with a GDP of $18.8 trillion in 2018, encompasses the collective economic weight of its member states.55 The UK may therefore face difficulty rolling over or negotiating trade agreements that match its current trade terms as a member of the EU.

Seeking continuity in its trade ties after Brexit, the UK is acting on a number of fronts. Among other things, the UK is

- Negotiating its own WTO schedule of commitments on goods, services, and agriculture. A schedule of commitments refers to the commitments that WTO members make to all other WTO members on the nondiscriminatory market access (i.e., "most-favored-nation," or MFN, access) they will provide for trade in goods, services, agriculture, and government procurement. Although the UK is a WTO member in its own right, it does not have an independent schedule of commitments, as the EU schedule applies to all EU members, including the UK. Outside of the EU, the UK would need to have its own schedule on the market access commitments to other WTO members. In some cases, the UK may be able to replicate the EU schedule; other cases may be more complex. For example, developing the UK's agricultural schedule involves reallocation of EU and UK tariff-rate quotas such as beef, poultry, dairy, cereals, rice, sugar, fruits, and other vegetables.56 The EU and UK have engaged in bilateral discussions on apportioning the tariff-rate quotas; some WTO members, including the United States, have raised concerns that the UK-EU approach could reduce the level and quality of their access to UK and EU markets.57 In terms of other WTO developments, parties to the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) have agreed to the UK's continued participation in the GPA in principle; the UK has delayed submitting its instrument of accession for the GPA until February 27, 2020, in part because of the delay in Brexit.

- Working to replicate existing EU deals with non-EU countries. The UK is a part of over 40 trade agreements with around 70 countries by virtue of its membership in the EU. Unless it makes other arrangements, the UK would lose its preferential access to these markets after leaving the EU. To avoid this outcome, the UK has been working to replicate the EU's trade agreements with other countries.58

According to the UK government, UK trade with countries with which the UK seeks to conclude continuity agreements accounted for 11.1% of total UK trade in goods and services in 2018.59 As of December 4, 2019, the UK has signed 20 "continuity" deals, accounting for about 8.3% of total UK trade; these deals cover around 50 countries or territories, including Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Iceland, Norway, and South Korea. - Negotiating sector-specific regulatory agreements. As a member of the EU, the UK is a part of EU regulatory agreements with certain non-EU countries for conformity assessments on product standards and regulations in certain sectors.60 In its preparations for Brexit, the UK government is aiming to replicate the key provisions of existing EU mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) with the United States, Australia, and New Zealand to assure continued acceptance by UK and partner country regulators of certain product testing and inspections by the other.

- Taking steps to pursue a range of new trade deals once outside of the EU. In addition to the United States, potential countries that the UK has identified as of interest for negotiating new trade deals include Australia, China, India, and New Zealand. A new priority for the UK is signing an FTA with Japan, with whom the EU already has an FTA.61 Rather than "rolling over" the EU-Japan FTA, Japan seeks to negotiate new terms with the UK. Japan is one of the UK's largest investors, with major carmakers such as Nissan, Toyota, and Honda operating auto-manufacturing factories in the UK.

Brexit and Northern Ireland62

In the 2016 Brexit referendum, Northern Ireland voted 56% to 44% against leaving the EU. Brexit poses considerable challenges for Northern Ireland, with potential implications for its peace process, economy, and, in the longer term, constitutional status in the UK. Following Brexit, Northern Ireland would be the only part of the UK to share a land border with an EU member state (see Figure 2). Preventing a hard border on the island of Ireland (with customs checks and physical infrastructure) has been a key goal, and a major stumbling block, in negotiating and finalizing the UK's withdrawal agreement with the EU.

Deciding upon arrangements for the post-Brexit border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was complicated by Northern Ireland's history of political violence. Roughly 3,500 people died during "the Troubles," the 30-year sectarian conflict (1969 to 1999) between unionists (Protestants who largely define themselves as British and support remaining part of the UK) and nationalists (Catholics who consider themselves Irish and may desire a united Ireland). At the time of the 1998 peace accord in Northern Ireland (known as the Good Friday Agreement or the Belfast Agreement), the EU membership of both the UK and the Republic of Ireland was regarded as essential to underpinning the political settlement by providing a common European identity for both unionists and nationalists in Northern Ireland. EU law also provided a supporting framework for guaranteeing the human rights, equality, and nondiscrimination provisions of the peace accord.

Since 1998, as security checkpoints were dismantled in accordance with the peace agreement, and because both the UK and Ireland belonged to the EU's single market and customs union, the circuitous 300-mile land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland effectively disappeared. The border's disappearance served as an important political and psychological symbol on both sides of the sectarian divide and helped produce a dynamic cross-border economy. Many experts deem an open, invisible border as crucial to a still-fragile peace process, in which deep divisions and a lack of trust persist. Some analysts suggest that differences over Brexit also have heightened tensions between the unionist and nationalist communities' respective political parties and stymied the reestablishment of the regional (or devolved) government, nearly three years after the last legislative assembly elections. (For more background, see Appendix B.)

Possible Implications of Brexit

The Irish Border and the Peace Process

Many on both sides of Northern Ireland's sectarian divide expressed deep concern that Brexit could lead to a return of a hard border with the Republic of Ireland and destabilize the peace process. Police officials warned that a hard border post-Brexit could pose considerable security risks. During the Troubles, the border regions were considered "bandit country," with smugglers and gunrunners. Checkpoints were frequently the site of conflict, especially between British soldiers and militant nationalist groups (or republicans), such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), that sought to achieve a united Ireland through force. Militant unionist groups (or loyalists) were also active during the Troubles.63

Security assessments suggest that if border or customs posts were reinstated, violent dissident groups opposed to the peace process would view such infrastructure as targets, endangering the lives of police and customs officers and threatening the security and stability of the border regions. Some experts fear that any such violence could lead to a remilitarization of the border and that the violence could spread beyond the border regions.64 Many observers note a slight uptick in dissident republican activity over the last year, especially in border regions, as groups such as the New IRA and the Continuity IRA seek to exploit the stalemates over both Northern Ireland's devolved government and Brexit. Violence has been directed in particular at police officers (long regarded by dissident republicans as legitimate targets), and several recent failed bombings have been attempted in border areas (especially Londonderry/Derry, a key flashpoint during the Troubles).65

Many in Northern Ireland and Ireland also are eager to maintain an open border to ensure "frictionless" trade, safeguard the north-south economy, and protect community relations. Furthering Northern Ireland's economic development and prosperity is regarded as crucial to helping ensure a lasting peace in Northern Ireland. Establishing customs checkpoints would pose logistical difficulties, and many people in the border communities worry that any hardening of the border could affect daily travel across the border to work, shop, or visit family and friends. Estimates suggest there are roughly 208 public road crossings along the border and nearly 300 crossing points when private roads and other unmarked access points are included.66 Some roads cross the border multiple times, and the border splits other roads down the center. Only a fraction of crossing points were open during the Troubles, and hour-long delays due to security measures and bureaucratic hurdles were common.67

|

Figure 2. Map of Northern Ireland (UK) and the Republic of Ireland |

|

|

Source: Graphic created by CRS using data from Esri (2017). |

Since the Brexit referendum in 2016, UK, Irish, and EU leaders asserted repeatedly that they did not want a hard border and worked to prevent such a possibility. In the initial December 2017 UK-EU agreement setting out the main principles for the withdrawal negotiations, the UK pledged to uphold the Good Friday Agreement, avoid a hard border (including customs controls and any physical infrastructure), and protect north-south cooperation on the island of Ireland. Analysts contend, however, that reaching agreement on a mechanism to ensure an open border was complicated by the UK government's pursuit of a largely hard Brexit, which would keep the UK outside of the EU's single market and customs union. As noted previously, the backstop emerged as the primary sticking point in gaining the UK Parliament's approval of former Prime Minister May's draft withdrawal agreement in the first half of 2019. Prime Minister Johnson opposed the backstop but also asserted a desire to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland.68

Some advocates of a hard Brexit contended that security concerns about the border were exaggerated and that the border issue was being exploited by the EU and those in the UK who would prefer a soft Brexit, in which the UK would remain inside the EU single market and/or customs union. The Good Friday Agreement commits the UK to normalizing security arrangements, including the removal of security installations "consistent with the level of threat," but does not explicitly require an open border. The Irish government and many in Northern Ireland—as well as most UK government officials—argued that an open border had become intrinsic to peace and to ensuring the fulfillment of provisions in the Good Friday Agreement that call for north-south cooperation on cross-border issues (including transport, agriculture, and the environment).69 Some advocates of a hard Brexit, frustrated by the Irish border question, ruminated on whether the Good Friday Agreement had outlived its usefulness, especially in light of the stalemate in reestablishing Northern Ireland's devolved government. Both the May and Johnson governments continued to assert that the UK remains committed to upholding the 1998 accord.70

In light of Johnson's victory with a decisive Conservative majority in the December 2019 elections and the presumption that Parliament will now pass the renegotiated withdrawal agreement before the Brexit deadline at the end of January 2020, concerns have receded to some degree about a hard border developing on the island of Ireland. Uncertainty persists about what the overall UK-EU future relationship—including with respect to trade—will look like post-Brexit and whether the two sides can reach an agreement by the end of the transition period. However, unlike with the previous backstop arrangement, the provisions related to the Northern Ireland border are not expected to change pending the outcome of the UK-EU negotiations on its future relationship. A former UK official notes that the Johnson government "claims they have got rid of the backstop but in fact, have transformed it from a fallback into the definitive future arrangement for Northern Ireland" that would effectively leave Northern Ireland in the EU's single market and customs union.71 Prolongation of the post-Brexit arrangements for Northern Ireland will be subject to the consent of the Northern Ireland Assembly in 2024 but is not contingent upon the conclusion of a broader UK-EU agreement by the end of the transition period in December 2020.72

At the same time, many of the details related to how the post-Brexit regulatory and customs arrangements for Northern Ireland will work in practice must still be fleshed out by UK and EU negotiators during the upcoming transition period, and Brexit has further exacerbated political and societal divisions in Northern Ireland. As noted previously, the DUP opposes the Northern Ireland provisions in the renegotiated withdrawal agreement because it views them as treating Northern Ireland differently from the rest of the UK and undermining the union. In light of the Conservative Party's large majority following the December 2019 elections, the DUP has lost political influence in the UK Parliament and the new Johnson government is not beholden to DUP support to pass the renegotiated withdrawal agreement.

Many in the DUP and other unionists feel abandoned by Prime Minister Johnson's renegotiated withdrawal agreement. Amid ongoing demographic, societal, and economic changes in Northern Ireland that predate Brexit, experts note that some in the unionist community perceive a loss in unionist traditions and dominance in Northern Ireland. Some analysts express concern that the new post-Brexit border and customs arrangements for Northern Ireland could enhance this existing sense of unionist disenfranchisement, especially if Northern Ireland is drawn closer to the Republic of Ireland's economic orbit in practice post-Brexit. Such unionist unease in turn could intensify frictions and political instability in Northern Ireland; observers also worry that heightened unionist frustration could prompt a resurgence in loyalist violence post-Brexit.73

Some experts have expressed concerns about the potential for a hard border on the island of Ireland in the longer term should Northern Ireland's Assembly fail to renew the post-Brexit arrangements that would keep Northern Ireland aligned with EU regulatory and customs rules. Although many view this scenario as unlikely given that pro-EU parties hold a majority in the Assembly (and this appears unlikely to change in near future), in such an event, the UK and the EU would need to agree on a new set of provisions to keep the border open. The DUP also argues that by allowing the Assembly to give consent to the border arrangements for an additional four years through a simple majority, the renegotiated withdrawal agreement undermines the Good Friday Agreement, which requires major Assembly decisions to receive cross-community support (i.e., a majority on each side of the unionist-nationalist divide).74

Some commentators believe the 2019 UK election results—in which the DUP lost two seats in the UK Parliament, unionists no longer hold a majority of Northern Ireland's 18 seats in Parliament, and DUP votes are no longer crucial to Prime Minister Johnson's ability to secure approval of the withdrawal agreement—may improve the prospects for reestablishing Northern Ireland's devolved government. A functioning devolved government may offer the DUP the best opportunity to ensure it has a voice in implementing the new border and customs arrangements for Northern Ireland and in the upcoming negotiations on the future political and trade relationship between the UK and the EU. On December 16, 2019, the UK and Irish governments launched a new round of talks with the main Northern Ireland political parties aimed at reestablishing the devolved government. Although the UK and Irish governments appear hopeful, divisions persist among unionist and nationalist political parties—including with respect to a proposed Irish Language Act—and news reports suggest that DUP concerns remain a key stumbling block in reaching an agreement to restore the devolved government.75

The Economy

Many experts contend that Brexit could have serious negative economic consequences for Northern Ireland. According to a UK parliamentary report, Northern Ireland depends more on the EU market (and especially that of Ireland) for its exports than does the rest of the UK.76 In 2017, approximately 57% of Northern Ireland's exports went to the EU, including 38% to Ireland, which was Northern Ireland's top single export and import partner. Trade with Ireland is especially important for small- and medium-sized companies in Northern Ireland. Although sales in 2017 to other parts of the UK (£11.3 billion) surpassed the value of all Northern Ireland exports (£10.1 billion) and were nearly three times the value of exports to Ireland (£3.9 billion), small- and medium-sized companies in Northern Ireland were responsible for the vast majority of Northern Ireland exports to Ireland. Large- and medium-sized Northern Ireland firms dominated in sales to the rest of the UK.77 UK and DUP leaders maintain that given the value of exports, however, the rest of the UK is overall more important economically to Northern Ireland than the EU.

Significant concerns existed in particular that a no-deal Brexit could jeopardize integrated labor markets and industries that operate on an all-island basis. Northern Ireland's agri-food sector, for example, would face serious challenges from a no-deal scenario. Food and live animals make up roughly 32% of Northern Ireland's exports to Ireland; a no-deal Brexit could effectively end this trade due to the need for EU sanitary and phytosanitary checks at specified border inspection posts in Ireland, which would significantly extend travel times and increase costs.78 The Ulster Farmers' Union—an industry association of farmers in Northern Ireland—asserted that a no-deal Brexit would be "catastrophic" for Northern Ireland farmers.79 Many manufacturers in Northern Ireland and Ireland also depend on integrated supply chains north and south of the border; raw materials that go into making products such as milk, cheese, butter, and alcoholic drinks often cross the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland several times for processing and packaging.80

Although many in Northern Ireland are relieved that a no-deal Brexit appears to have been averted, the DUP and others in Northern Ireland contend that the renegotiated withdrawal agreement could be detrimental to Northern Ireland's economy. A UK government risk assessment released in October 2019 acknowledged that the lack of clarity about how the customs arrangements for Northern Ireland will operate in practice and possible regulatory divergence between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK could lead to reduced business investment, consumer spending, and trade in Northern Ireland.81 The DUP highlights the potential negative profit implications for Northern Ireland businesses engaged in trade with the rest of the UK. Under the new deal, Northern Ireland firms that export goods to elsewhere in the UK would be required under EU customs rules to make exit declarations, which would likely increase costs and administrative burdens. Concerns also exist that should the UK and the EU fail to reach agreement on a future new trade relationship by the end of the transition period, there could be significant customs and regulatory divergence between the UK and the EU, which in turn could mean more checks and controls on goods traded between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.82

Brexit could have other economic ramifications for Northern Ireland, as well. Some experts argue that access to the EU single market has been one reason for Northern Ireland's success in attracting foreign direct investment since the end of the Troubles, and they express concern that Brexit could deter future investment. Post-Brexit, Northern Ireland also stands to lose EU regional funding (roughly $1.3 billion between 2014 and 2020) and agricultural aid (direct EU farm subsidies to Northern Ireland are nearly $375 million annually).83

UK officials maintain that the government is determined to safeguard Northern Ireland's interests and "make a success of Brexit" for Northern Ireland.84 They insist that Northern Ireland will continue to trade with the EU (including Ireland) and that Brexit offers new economic opportunities for Northern Ireland outside the EU. Supporters of Prime Minister Johnson's renegotiated withdrawal agreement argue that it will help improve Northern Ireland's economic prospects. Northern Ireland will remain part of the UK customs union and thus be able to participate in future UK trade deals but also will retain privileged access to the EU single market, which may make it an even more attractive destination for foreign direct investment.85

Constitutional Status and Border Poll Prospects

Brexit has revived questions about Northern Ireland's constitutional status. Sinn Fein—the leading nationalist party in Northern Ireland—argues that "Brexit changes everything" and could generate greater support for a united Ireland.86 Since the 2016 Brexit referendum, Sinn Fein has repeatedly called for a border poll (a referendum on whether Northern Ireland should remain part of the UK or join the Republic of Ireland) in the hopes of realizing its long-term goal of Irish unification.87 The Good Friday Agreement provides for the possibility of a border poll, in line with the consent principle, which stipulates that any change in Northern Ireland's status can come about only with the consent of the majority of its people. The December 2019 election, in which unionist parties lost seats in the UK parliament while nationalist and cross-community parties gained seats, also has prompted increased discussion and scrutiny of Northern Ireland's constitutional status and whether a united Ireland may become a future reality.

Any decision to hold a border poll on Northern Ireland's constitutional status rests with the UK Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, who in accordance with the Good Friday Agreement must call a border poll if it "appears likely" that "a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland."88 At present, and despite the 2019 election results in Northern Ireland, most experts believe the conditions required to hold a border poll on Northern Ireland's constitutional status do not exist. Most opinion polls indicate that a majority of people in Northern Ireland continue to support the region's position as part of the UK. Some analysts attribute the UK parliamentary election results in Northern Ireland to frustration with the DUP and Sinn Fein (which also saw its share of the vote decline amid gains for a more moderate nationalist party and a cross-community party) and their inability to forge a new devolved government, rather than as an indication of support for a united Ireland.89

At the same time, some surveys suggest that views on Northern Ireland's status may be shifting and that a "damaging Brexit" in particular could increase support for a united Ireland. A September 2019 poll found that 46% of those polled in Northern Ireland favored unification with Ireland, versus 45% who preferred remaining part of the UK.90 Many experts also note that Northern Ireland's changing demographics (in which the Catholic, largely Irish-identifying population is growing while the Protestant, British-identifying population is declining)—combined with the post-Brexit arrangements for Northern Ireland that could lead to enhanced economic ties with the Republic of Ireland—could boost support for a united Ireland in the longer term.91

Irish Prime Minister Varadkar asserts that a border poll in the near future would be divisive and disruptive. Some observers suggest that Prime Minister Varadkar's current priority is ensuring an orderly Brexit, and any support or planning for a poll on Irish unification could fan unionist fears and impede this goal. Others question the extent of public and political support in the Republic of Ireland for unification, given its potential economic costs and concerns that unification could spark renewed loyalist violence in Northern Ireland. Following the December 2019 UK election, Prime Minister Varadkar warned against any steps toward a united Ireland at present and argued that political and public attention should instead be focused on reviving Northern Ireland's devolved government and power-sharing institutions.92

Implications for U.S.-UK Relations

Many U.S. officials and Members of Congress view the UK as the United States' closest and most reliable ally. This perception stems from a combination of factors, including a sense of shared history, values, and culture; a large and mutually beneficial economic relationship; and extensive cooperation on foreign policy and security issues. The UK and the United States have a particularly close defense relationship and a unique intelligence-sharing partnership.

Since 2016, President Trump has been outspoken in repeatedly expressing his support for Brexit.93 President Trump counts leading Brexit supporters, including Boris Johnson and Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage, among his personal friends.94 He publicly criticized Theresa May's handling of Brexit and stated during the most recent Conservative leadership race that Boris Johnson would "make a great prime minister."95 President Trump repeated his support for Johnson prior to the December 2019 UK election and celebrated Johnson's win, writing on social media that the election outcome would allow the United States and UK to reach a new trade deal. 96

Senior Administration officials have reinforced the President's pro-Brexit messages. During an August 2019 visit to London, then-U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton stated that the Administration would "enthusiastically" support a no-deal Brexit; he asserted that a U.S.-UK trade deal could be negotiated quickly and possibly be concluded sector-by-sector to speed up the process.97 In a September 2019 visit to Ireland, Vice President Mike Pence reiterated the Administration's support for the UK leaving the EU and urged Ireland and the EU to "work to reach an agreement that respects the United Kingdom's sovereignty."98 Vice President Pence expressed his hope that an agreement would "also provide for an orderly Brexit."99

Foreign Policy and Security Issues

President Trump has expressed a largely positive view of the UK and made his first official state visit there in June 2019 (he also visited in July 2018), but there have been some tensions over substantive policy differences between the UK government and the U.S. Administration and backlash from the UK side over various statements made by the President. Under President Trump and Prime Minister May, the United States and the UK proceeded from relatively compatible starting points and maintained close cooperation on issues such as counterterrorism, combating the Islamic State, and seeking to end the conflict in Syria.

In contrast, the UK government has strongly defended both the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreement (known as the Iran nuclear deal) and the Paris Agreement (known as the Paris climate agreement) and disagreed with the Trump Administration's decisions to withdraw the United States from those agreements.100 Prime Minister May disagreed with the Trump Administration's recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital, calling the move "unhelpful in terms of prospects for peace in the region."101 She also expressed "deep concern" about the President's March 2018 decision to introduce tariffs on steel and aluminum imports to the United States.102

Despite the close relationship between President Trump and Prime Minister Johnson, there are no clear indications that a post-Brexit UK might reverse course on contentious areas such as the Iran nuclear deal or climate change to align with the views of the Trump Administration.

Brexit has forged opposing viewpoints about the potential trajectory of the UK's international influence in the coming years. The Conservative Party-led government has outlined a post-Brexit vision of a Global Britain that benefits from increased economic dynamism; remains heavily engaged internationally in terms of trade, political, and security issues; maintains close foreign and security policy cooperation with both the United States and the EU; and retains "all the capabilities of a global power."103 Other observers contend that Brexit would reduce the UK's ability to influence world events and that, without the ability to help shape EU foreign policy, the UK will have less influence in the rest of the world.104 Developments in relation to the UK's global role and influence are likely to have consequences for perceptions of the UK as either an effective or a diminished partner for the United States.

Parallel debates apply to a consideration of security and defense matters. Analysts believe that close U.S.-UK cooperation will continue for the foreseeable future in areas such as counterterrorism, intelligence, and the future of the NATO, as well as numerous global and regional security challenges. NATO remains the preeminent transatlantic security institution, and in the context of Brexit, UK leaders have emphasized their continued commitment to be a leading country in NATO. Analysts also expect the UK to remain a key U.S. partner in operations to combat the remaining elements of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

In 2018, the UK had the world's sixth-largest military expenditure (behind the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and India), spending approximately $56.1 billion.105 The UK is also one of seven NATO countries to meet the alliance's defense spending benchmark of 2% of GDP (according to NATO, the UK's defense spending was 2.14% of GDP in 2018 and is expected to be 2.13% of GDP in 2019).106

Nevertheless, Brexit has added to questions about the UK's ability to remain a leading military power and an effective U.S. security partner. U.S. officials and other leading experts have expressed concerns about reductions in the size and capabilities of the British military in recent years.107 Negative economic effects from Brexit could exacerbate concerns about the UK's ability to maintain defense spending, investment, and capabilities.

Brexit also could have a substantial impact on U.S. strategic interests in relation to Europe more broadly and with respect to possible implications for future developments in the EU. For example, Brexit could allow the EU to move ahead more easily with developing shared capabilities and undertaking military integration projects under the EU Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), efforts that generate a mixture of praise and criticism from the United States. In the past, the UK has irritated some of its EU partners by essentially vetoing initiatives to develop a stronger CSDP, arguing that such efforts duplicate and compete with NATO. With the UK commonly regarded as the strongest U.S. partner in the EU, a partner that commonly shares U.S. views, and an influential voice in initiatives to develop EU foreign and defense policies, analysts have suggested that the UK's withdrawal could increase divergence between the EU and the United States on certain security and defense issues.108

More broadly, U.S. officials have long urged the EU to move beyond what is often perceived as a predominantly inward focus on treaties and institutions, in order to concentrate more effort and resources toward addressing a wide range of shared external challenges. Some observers note that Brexit has pushed Europe back toward another prolonged bout of internal preoccupation, consuming a considerable degree of UK and EU time and personnel resources in the process.

Trade and Economic Relations and Prospective U.S.-UK FTA

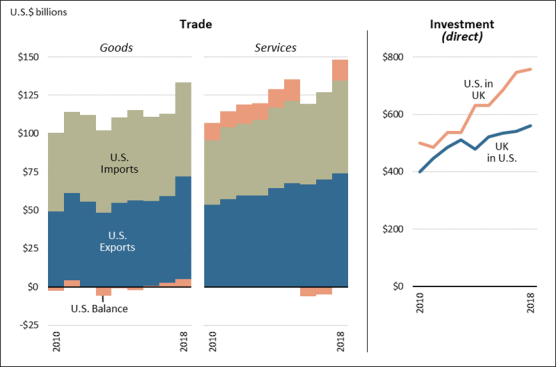

The UK is a major U.S. trade and economic partner (see Figure 3). In 2018, the UK was the United States' fifth-largest goods export market, seventh-largest goods import supplier, and largest services trading partner. U.S. trade in goods and services with the UK ($263 billion) accounted for about one-fifth of U.S. trade with the EU ($1.3 trillion) in 2018.109 The UK is also a leading source of and destination for foreign direct investment, and affiliate activity is significant. Brexit presents commercial uncertainty for the approximately 42,000 U.S. companies exporting to the UK and for the U.S. firms operating in the UK, which include some 4,000 majority-owned subsidiaries (2017 data).110 Presently, WTO terms govern U.S.-UK trade (like U.S. trade with the rest of the EU), and these terms would apply after Brexit unless the two sides secure more preferential access to each other's markets through the conclusion of a bilateral FTA.

On October 16, 2018, the Trump Administration notified Congress under Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) of its intent to enter into negotiations with the UK on a bilateral trade agreement, which many Members of Congress support. U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has said that trade negotiations with the UK are a "priority" and will start as soon as the UK is in a position to negotiate, but he cautioned that the negotiations may take time.111 Some Members of Congress have cautioned that they would oppose a trade agreement if Brexit were detrimental to the Northern Ireland peace process, whereas others support a trade agreement without such conditions.112

The UK cannot formally negotiate or conclude a new agreement until it exits the EU. In the meantime, in July 2017, the United States and the UK established a bilateral working group to lay the groundwork for a potential future bilateral FTA post-Brexit and to ensure commercial continuity in U.S.-UK ties. The bilateral working group has met regularly to discuss a range of issues, including industrial and agricultural goods, services, investment, digital trade, intellectual property rights, regulatory issues, and small- and medium-sized enterprises.113 The United States and the UK also have signed MRAs covering telecommunications equipment, electromagnetic compatibility for information and communications technology products, pharmaceutical good manufacturing practice inspections, and marine equipment to ensure continuity of trade in these areas.114 In addition, the two sides have signed agreements on insurance and derivatives trading and clearing, as well, to ensure regulatory certainty.115

Although the Johnson government appears intent on regaining an independent UK trade policy, prospects for a U.S.-UK FTA are mixed. Some analysts question the sequencing of UK-EU and U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, as the United States may face difficulty negotiating meaningfully with the UK without knowing what the final UK-EU relationship looks like. Others assert that parallel negotiations are feasible as the contours of the UK-EU relationship become clearer. Some experts view a U.S.-UK FTA as more feasible than a U.S.-EU FTA, given the U.S.-UK "special relationship" and historical similarities in trade approaches. The UK has been a leading voice on trade liberalization in the EU. Others have expressed doubts about the likelihood of a "quick win" for either side, particularly as negotiations would need to overcome a number of difficult obstacles and concerns.116

Many U.S. and UK businesses and other groups see an FTA as opportunity to enhance market access and align UK regulations more closely with those of the United States than the EU regulatory framework, aspects of which raise concerns for U.S. business interests. Other stakeholder groups oppose what they view as efforts to weaken UK regulations.117 For instance, some in UK civil society have expressed concerns about the implications of U.S. demands for greater access to the UK market; their concerns include, for instance, the potential impact of a trade deal on UK food safety regulations, in light of U.S. industry practices of disinfecting chicken with chlorine and treating beef with hormones. The potential impact of a trade deal on UK pharmaceutical drug pricing remains an active issue in the UK as well. Key issues in U.S.-UK FTA negotiations also could include financial services, investment, and e-commerce, which are a prominent part of U.S.-UK trade. To the extent that the UK decides to continue aligning its rules and regulations with the EU, sticking points in past U.S.-EU trade negotiations could resurface in the U.S.-UK context.

Another uncertainty is what role the U.S.-EU trade negotiations may place in defusing transatlantic trade frictions on tariffs and other issues, and how these dynamics may affect the outlook for the U.S.-UK trade negotiations. In addition, some stakeholders support using the trade negotiations as an opportunity to engage the UK on other issues, such as its approach to digital services taxes.

Should U.S.-UK trade agreement negotiations formally commence, it remains to be seen whether the United States and the UK would take a comprehensive approach in a "single undertaking" or seek a more limited agreement focused on certain issues or sectors. Under the Trump Administration, the United States has taken both approaches, for instance, taking a comprehensive approach with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA), which is the renegotiated North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and a more limited approach with the bilateral trade negotiations with Japan.118

It also remains to be seen whether a potential final FTA would meet congressional expectations or TPA requirements. Congress is expected to continue consultations with the Administration over the scope of proposed negotiations and to engage in oversight during negotiations. Congress would need to approve implementing legislation for a potential final trade agreement to enter into force.

Conclusion

Three years and a half years after the Brexit referendum, the UK's December 2019 general election delivered a measure of clarity about how Brexit is likely to unfold. The UK is likely to withdraw from the EU at the end of January 2020 and begin negotiations with the EU on an FTA and other elements of the future UK-EU relationship during a transition period scheduled to last until the end of 2020. A significant number of unknowns remain, including how elements of the withdrawal agreement will be implemented, whether the two sides will be able to conclude an agreement on the future relationship during the 11-month transition period, the effects of ending the transition period without such an agreement. Regardless of the precise turn of events, the topic of Brexit is expected to remain a primary focus of UK politics and a leading concern for the EU for the foreseeable future.